Project 8: Reader-Writer Lock Implementation

Build a reader-writer lock and evaluate fairness policies.

Quick Reference

| Attribute | Value |

|---|---|

| Difficulty | Level 4 (Expert) |

| Time Estimate | 2 Weeks |

| Main Programming Language | C (Alternatives: ) |

| Alternative Programming Languages | N/A |

| Coolness Level | Level 4 (Hardcore Tech Flex) |

| Business Potential | Level 1 (Resume Gold) |

| Prerequisites | C programming, basic IPC familiarity, Linux tools (strace/ipcs) |

| Key Topics | reader preference, writer preference, fairness |

1. Learning Objectives

By completing this project, you will:

- Build a working IPC-based system aligned with Stevens Vol. 2 concepts.

- Implement robust lifecycle management for IPC objects.

- Handle errors and edge cases deterministically.

- Document and justify design trade-offs.

- Benchmark or validate correctness under load.

2. All Theory Needed (Per-Concept Breakdown)

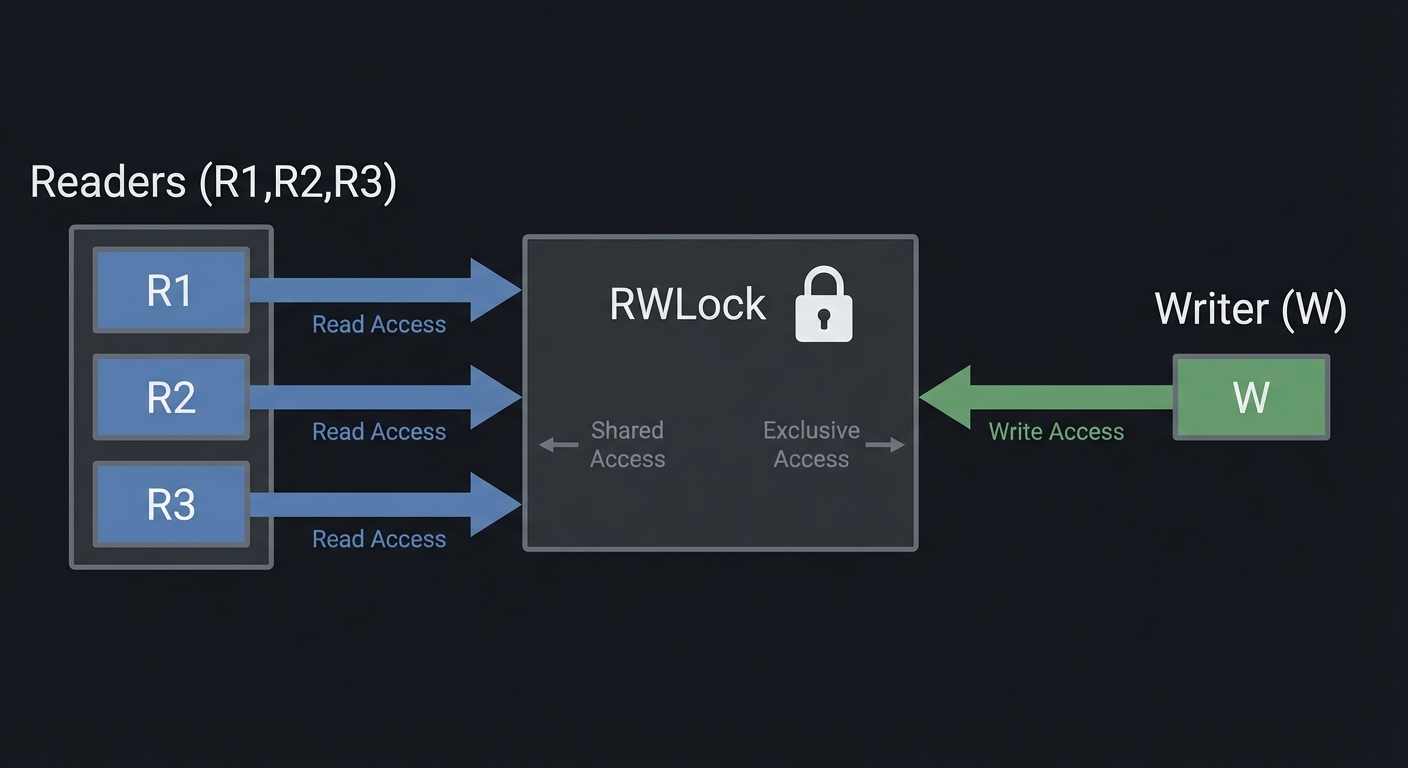

Reader-Writer Locks and Fairness

Fundamentals

A reader-writer lock allows multiple readers to access shared data concurrently while ensuring writers have exclusive access. The intuition is simple: reads can proceed in parallel, writes must be exclusive. The challenge is fairness. If readers continuously arrive, writers may starve; if writers have priority, readers may starve. A correct implementation must define and enforce a policy.

Deep Dive into the Concept

Implementing a reader-writer lock from first principles exposes the design trade-offs. The lock maintains counters for active readers and waiting writers. The simplest policy, “reader preference,” allows new readers to acquire the lock while readers are active, even if writers are waiting. This maximizes read throughput but can starve writers. “Writer preference” prevents new readers from entering when a writer is waiting, ensuring writers eventually proceed. A balanced policy, such as “phase-fair” or “FIFO”, aims to avoid starvation for both sides.

Reader-writer locks are typically implemented with a mutex and condition variables. The mutex protects the counters; the condition variables allow readers or writers to wait. The lock acquisition logic must be careful: a reader waits if a writer is active (and possibly if writers are waiting, depending on policy). A writer waits if any reader or writer is active. On unlock, the lock signals either readers or writers based on the policy. This is a classic concurrency exercise because the correctness depends on invariant reasoning and precise signaling.

How this fits on projects

This concept is central to the reader-writer lock implementation project and is also relevant to record locking and shared-memory databases.

Definitions & key terms

- Reader preference -> Readers can starve writers.

- Writer preference -> Writers can starve readers.

- Fair lock -> Attempts to avoid starvation.

Mental model diagram (ASCII)

Readers (R1,R2,R3) -> [ RWLock ] <- Writer (W)

How it works (step-by-step, with invariants and failure modes)

- Reader acquires mutex, checks writer_active and writers_waiting.

- If allowed, increments readers and releases mutex.

- Writer acquires mutex; waits until readers==0 and writer_active==0.

- Writer sets writer_active and releases mutex.

- Unlock signals next group based on policy.

Failure modes: starvation, missed wakeups, incorrect counter updates.

Minimal concrete example

// writer lock

pthread_mutex_lock(&m);

while (readers > 0 || writer_active) pthread_cond_wait(&can_write, &m);

writer_active = 1;

pthread_mutex_unlock(&m);

**Common misconceptions**

- "RWLocks always improve performance." -> Only when reads dominate.

- "Reader preference is fine." -> It can starve writers under load.

**Check-your-understanding questions**

1. Why can writer starvation happen in reader-preference locks?

2. How does writer preference affect read latency?

3. What invariant must hold when a writer owns the lock?

**Check-your-understanding answers**

1. New readers keep entering, preventing writer progress.

2. Reads can block behind waiting writers, increasing latency.

3. readers==0 and writer_active==1.

**Real-world applications**

- In-memory caches with many reads and few writes.

- Filesystem metadata structures.

**Where you’ll apply it**

- In this project: §3.2 Functional Requirements, §5.10 Phase 2.

- Also used in: [P09-record-locking-db.md](P09-record-locking-db.md).

**References**

- Butenhof, "Programming with POSIX Threads".

- `man 3 pthread_rwlock`.

**Key insights**

- RWLocks are about policy as much as mechanism.

**Summary**

Reader-writer locks enable concurrency but only if you choose a fair policy and implement it correctly.

**Homework/Exercises to practice the concept**

1. Implement reader-preference and writer-preference variants.

2. Stress test with 10 readers and 1 writer.

3. Measure throughput and starvation behavior.

**Solutions to the homework/exercises**

1. Add a writers_waiting counter for writer preference.

2. Observe writer wait time under read-heavy load.

3. Record mean and p99 latencies for both variants.

---

## 3. Project Specification

### 3.1 What You Will Build

Build a reader-writer lock and evaluate fairness policies.

### 3.2 Functional Requirements

1. **Requirement 1**: Implement reader and writer lock functions

2. **Requirement 2**: Support selectable fairness policy

3. **Requirement 3**: Demonstrate starvation cases and fixes

### 3.3 Non-Functional Requirements

- **Performance**: Must handle at least 10,000 messages/operations without failure.

- **Reliability**: IPC objects are cleaned up on shutdown or crash detection.

- **Usability**: CLI output is readable with clear error codes.

### 3.4 Example Usage / Output

```text

./rwlock_test --readers 8 --writers 2 --policy writer

### 3.5 Data Formats / Schemas / Protocols

State struct: {readers, writer_active, writers_waiting}.

### 3.6 Edge Cases

- Writer starvation

- Reader starvation

- Missed wakeups

### 3.7 Real World Outcome

You will have a working IPC subsystem that can be run, traced, and tested in a reproducible way.

#### 3.7.1 How to Run (Copy/Paste)

```bash

make

./run_demo.sh

#### 3.7.2 Golden Path Demo (Deterministic)

```bash

./run_demo.sh --mode=golden

Expected output includes deterministic counts and a final success line:

```text

OK: golden scenario completed

#### 3.7.3 Failure Demo (Deterministic)

```bash

./run_demo.sh --mode=failure

Expected output:

```text

ERROR: invalid input or unavailable IPC resource

exit=2

---

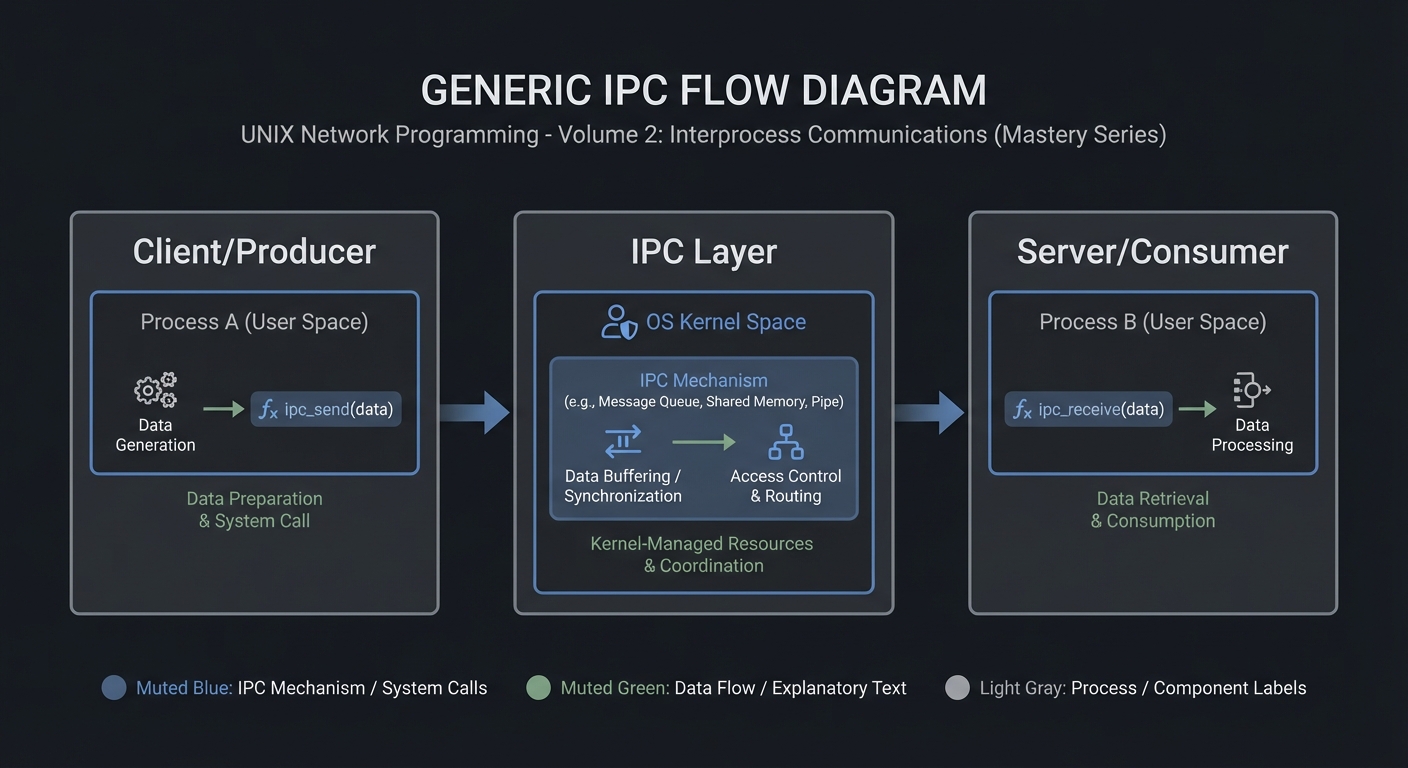

## 4. Solution Architecture

### 4.1 High-Level Design

Client/Producer -> IPC Layer -> Server/Consumer

4.2 Key Components

| Component | Responsibility | Key Decisions |

|---|---|---|

| IPC Setup | Create/open IPC objects | POSIX vs System V choices |

| Worker Loop | Send/receive messages | Blocking vs non-blocking |

| Cleanup | Unlink/remove IPC objects | Crash safety |

4.3 Data Structures (No Full Code)

struct message {

int id;

int len;

char payload[256];

};

### 4.4 Algorithm Overview

**Key Algorithm: IPC Request/Response**

1. Initialize IPC resources.

2. Client sends request.

3. Server processes and responds.

4. Cleanup on exit.

**Complexity Analysis:**

- Time: O(n) in number of messages.

- Space: O(1) per message plus IPC buffer.

---

## 5. Implementation Guide

### 5.1 Development Environment Setup

```bash

sudo apt-get install build-essential

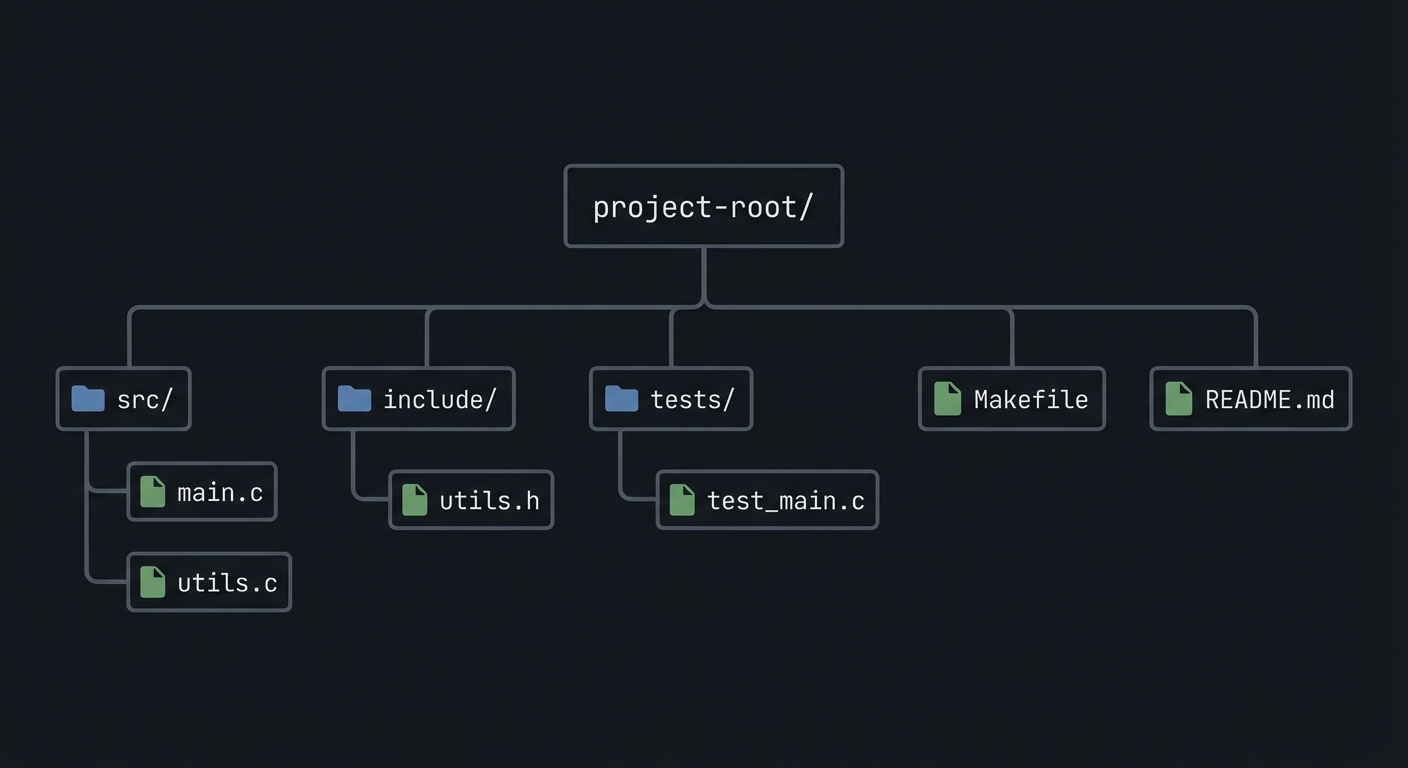

### 5.2 Project Structure

project-root/

├── src/

├── include/

├── tests/

├── Makefile

└── README.md

5.3 The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do you balance throughput and fairness in shared data access?”

5.4 Concepts You Must Understand First

- IPC object lifecycle (create/open/unlink)

- Blocking vs non-blocking operations

- Error handling with errno

5.5 Questions to Guide Your Design

- What invariants guarantee correctness in this IPC flow?

- How will you prevent resource leaks across crashes?

- How will you make the system observable for debugging?

5.6 Thinking Exercise

Before coding, sketch the IPC lifecycle and identify where deadlock could occur.

5.7 The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- Why choose this IPC mechanism over alternatives?

- What are the lifecycle pitfalls?

- How do you test IPC code reliably?

5.8 Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with a single producer and consumer.

Hint 2: Add logging around every IPC call.

Hint 3: Use strace or ipcs to verify resources.

5.9 Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| IPC fundamentals | Stevens, UNP Vol 2 | Relevant chapters |

| System calls | APUE | Ch. 15 |

5.10 Implementation Phases

Phase 1: Foundation (2-4 hours)

Goals:

- Create IPC objects.

- Implement a minimal send/receive loop.

Tasks:

- Initialize IPC resources.

- Implement basic client and server.

Checkpoint: Single request/response works.

Phase 2: Core Functionality (4-8 hours)

Goals:

- Add error handling and cleanup.

- Support multiple clients or concurrent operations.

Tasks:

- Add structured message format.

- Implement cleanup on shutdown.

Checkpoint: System runs under load without leaks.

Phase 3: Polish & Edge Cases (2-4 hours)

Goals:

- Add deterministic tests.

- Document behaviors.

Tasks:

- Add golden and failure scenarios.

- Document limitations.

Checkpoint: Tests pass, behavior documented.

5.11 Key Implementation Decisions

| Decision | Options | Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blocking mode | blocking vs non-blocking | blocking | Simpler for first version |

| Cleanup | manual vs automated | explicit cleanup | Avoid stale IPC objects |

6. Testing Strategy

6.1 Test Categories

| Category | Purpose | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Unit Tests | Validate helpers | message encode/decode |

| Integration Tests | IPC flow | client-server round trip |

| Edge Case Tests | Failure modes | missing queue, full buffer |

6.2 Critical Test Cases

- Single client request/response works.

- Multiple requests do not corrupt state.

- Failure case returns exit code 2.

6.3 Test Data

Input: “hello” Expected: “hello”

7. Common Pitfalls & Debugging

7.1 Frequent Mistakes

| Pitfall | Symptom | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Not cleaning IPC objects | Next run fails | Add cleanup on exit |

| Blocking forever | Program hangs | Add timeouts or non-blocking mode |

| Incorrect message framing | Corrupted data | Add length prefix and validate |

7.2 Debugging Strategies

- Use

strace -fto see IPC syscalls. - Use

ipcsor/dev/mqueueto inspect objects.

7.3 Performance Traps

- Small queue sizes cause frequent blocking.

8. Extensions & Challenges

8.1 Beginner Extensions

- Add verbose logging.

- Add a CLI flag to toggle non-blocking mode.

8.2 Intermediate Extensions

- Add request timeouts.

- Add a metrics report.

8.3 Advanced Extensions

- Implement load testing with multiple clients.

- Add crash recovery logic.

9. Real-World Connections

9.1 Industry Applications

- IPC services in local daemons.

- Message-based coordination in legacy systems.

9.2 Related Open Source Projects

- nfs-utils - Uses RPC and IPC extensively.

- systemd - Uses multiple IPC mechanisms.

9.3 Interview Relevance

- Demonstrates system call knowledge and concurrency reasoning.

10. Resources

10.1 Essential Reading

- Stevens, “UNP Vol 2”.

- Kerrisk, “The Linux Programming Interface”.

10.2 Video Resources

- Unix IPC lectures from OS courses.

10.3 Tools & Documentation

man 7 ipc,man 2for each syscall.

10.4 Related Projects in This Series

11. Self-Assessment Checklist

11.1 Understanding

- I can describe IPC object lifecycle.

- I can explain blocking vs non-blocking behavior.

- I can reason about failure modes.

11.2 Implementation

- All functional requirements are met.

- Tests pass.

- IPC objects are cleaned up.

11.3 Growth

- I can explain design trade-offs.

- I can explain this project in an interview.

12. Submission / Completion Criteria

Minimum Viable Completion:

- Basic IPC flow works with correct cleanup.

- Error handling returns deterministic exit codes.

Full Completion:

- Includes tests and deterministic demos.

- Documents trade-offs and limitations.

Excellence (Going Above & Beyond):

- Adds performance benchmarking and crash recovery.