Unix IPC Mastery - Stevens Vol 2 Complete

Goal: Master every major Unix IPC mechanism by building real systems from W. Richard Stevens’ Unix Network Programming, Volume 2. You will understand how data moves between processes, how synchronization actually works, and why each IPC family (pipes, message queues, shared memory, RPC) exists. By the end, you will be able to design, implement, and debug IPC-heavy systems from first principles, and choose the right mechanism based on performance, safety, and operational trade-offs.

Introduction: What This Guide Covers

Unix IPC (Interprocess Communication) is the set of kernel mechanisms that let separate processes exchange data and coordinate execution. It exists because processes are isolated for safety, but real systems need to share state, stream data, and synchronize work across that isolation boundary. IPC is the foundation for shells, databases, web servers, build systems, and any multi-process architecture.

What you will build (by the end of this guide):

- A shell-style pipeline executor and a

popen()reimplementation (pipes, fork, exec) - FIFO (named pipe) client-server systems for unrelated processes

- POSIX and System V message queue services (including priority dispatch and benchmarking)

- Synchronization primitives (mutex/cond producer-consumer, reader-writer locks, record locking)

- POSIX and System V shared-memory systems (ring buffer, image processor)

- A memory-mapped database with persistence and locking

- A Sun RPC calculator with authentication and a distributed RPC-based KV store

Scope (what is included):

- POSIX and System V IPC APIs and their lifecycle semantics

- Pipes, FIFOs, message queues, shared memory, semaphores

- Pthreads synchronization primitives and advisory record locking

mmap()as file-backed shared memory- ONC/Sun RPC + XDR + rpcbind + rpcgen

Out of scope (for this guide):

- Kernel implementation internals of IPC subsystems

- Full network programming beyond RPC (HTTP, TLS, advanced socket design)

- Windows IPC (named pipes, ALPC, etc.)

The Big Picture (Mental Model)

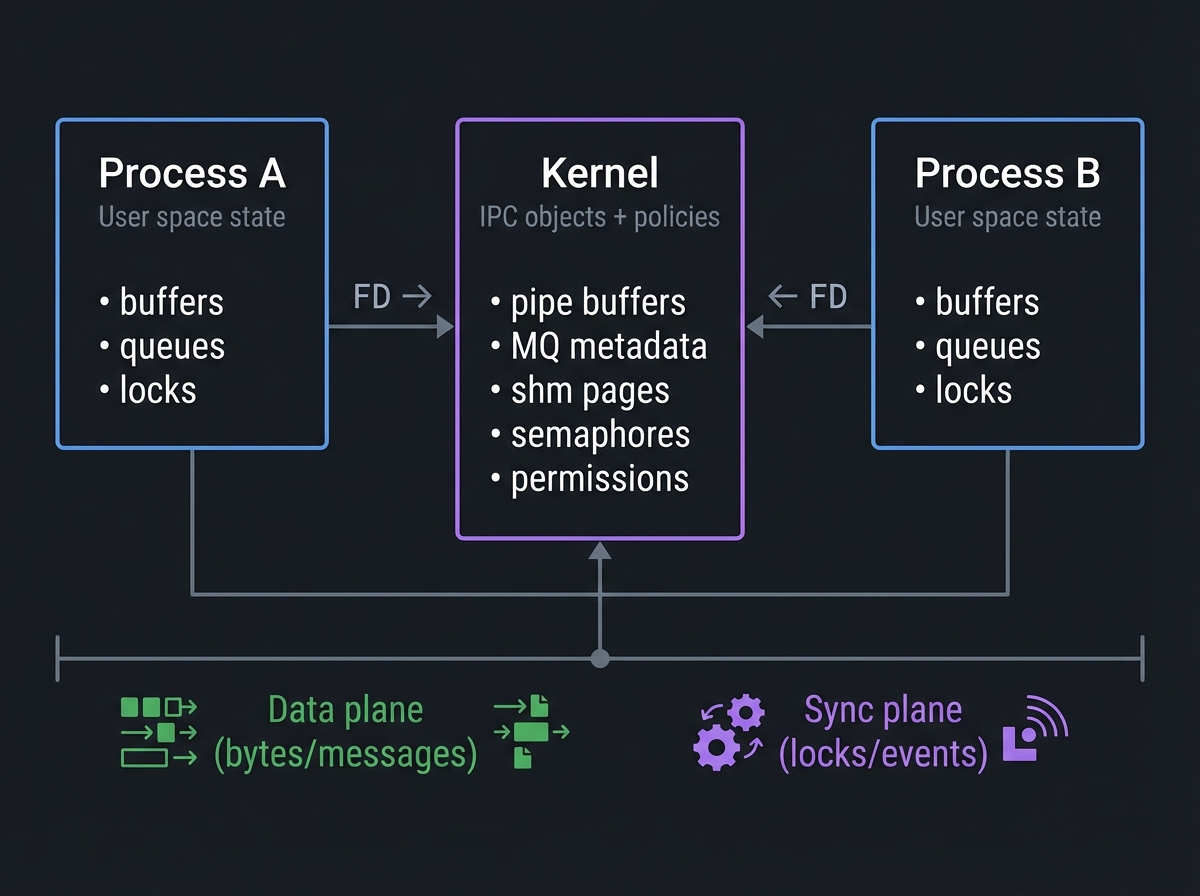

Process A Kernel Process B

┌────────────────────────┐ ┌──────────────────────────┐ ┌────────────────────────┐

│ User space state │ │ IPC objects + policies │ │ User space state │

│ - buffers │ FD -> │ - pipe buffers │ <- FD │ - buffers │

│ - queues │ │ - MQ metadata │ │ - queues │

│ - locks │ │ - shm pages │ │ - locks │

└───────────┬────────────┘ │ - semaphores │ └───────────┬────────────┘

│ │ - permissions │ │

v └──────────┬──────────────┘ v

Data plane (bytes/messages) │ Sync plane (locks/events)

│ │ │

└──────────────────────────────────┴──────────────────────────────────┘

Key Terms You Will See Everywhere

- IPC object: A kernel-managed resource for communication or synchronization (pipe, queue, shared memory, semaphore).

- File descriptor (FD): A process-local handle to a kernel object (file, pipe, socket, shared memory fd).

- Blocking vs non-blocking: Whether a call waits for data/space or returns immediately.

- Atomicity: Operations that complete as a single, indivisible step.

- Namespace: The naming system for IPC objects (POSIX names vs System V keys).

- Persistence: Whether IPC objects survive process exit (System V often does) or are reference-counted (POSIX often is).

How to Use This Guide

- Read the Theory Primer first. It is a mini-book and explains the mental models you need to avoid deadlocks, data corruption, and performance traps.

- Work projects in order for the first pass. The early projects build the muscle memory for file descriptors, blocking semantics, and object lifetimes.

- For every project, read the Core Question and Thinking Exercise before coding. This reduces blind copy-paste and builds real intuition.

- Instrument everything. Use

strace,lsof,ipcs,ipcrm,rpcinfo, and log timestamps to make behavior visible. - Repeat each project with one variation. Example: build the same pipeline executor with non-blocking I/O, or swap POSIX MQ for SysV MQ.

Prerequisites & Background Knowledge

Before starting these projects, you should have foundational understanding in these areas:

Essential Prerequisites (Must Have)

Programming Skills:

- C programming (pointers, memory management, structs)

- Understanding of process creation with

fork()and execution withexec() - Basic file I/O operations (

open,read,write,close) - Familiarity with

errnoand error handling patterns - Recommended Reading: “The C Programming Language” by Kernighan & Ritchie

Operating Systems Fundamentals:

- Process vs thread concepts

- Virtual memory basics and page faults

- File descriptors and open file descriptions

- System calls vs library functions

- Recommended Reading: “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” (Concurrency + Processes chapters)

Unix Environment:

- Shell scripting basics

- Reading man pages (

man 2 pipe,man 7 sem_overview,man 7 mq_overview) - Using

straceandlsof - Recommended Reading: “Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment” by Stevens & Rago — Ch. 3, 8, 15

Helpful But Not Required

Threading:

pthread_create,pthread_join,pthread_mutex_t,pthread_cond_t- Can learn during: Projects 7-10

Networking:

- TCP/UDP basics, ports, DNS

- Can learn during: Projects 16-18 (RPC)

Self-Assessment Questions

Before starting, ask yourself:

- ✅ Can you explain what happens to file descriptors across

fork()andexec()? - ✅ Do you understand why closing a pipe’s write end affects readers?

- ✅ Can you interpret

straceoutput forread()andwrite()? - ✅ Have you used

ipcsoripcrmto inspect IPC objects? - ✅ Can you explain the difference between blocking and non-blocking I/O?

If you answered “no” to questions 1-3: Spend 1-2 weeks on APUE Chapters 3, 8, 15 before starting. If you answered “yes” to all 5: You are ready to begin.

Development Environment Setup

Required Tools:

- Linux machine (Ubuntu 22.04+ or Debian 12 recommended)

- GCC or Clang (C11 support)

makestrace,ltrace,lsofipcs,ipcrmrpcbind,rpcinfo,rpcgen(for RPC projects)

Recommended Tools:

- Valgrind for memory leak detection

- GDB or LLDB for debugging

perffor profilingtcpdumporwiresharkfor RPC traffic

Testing Your Setup:

# Verify POSIX shared memory support

$ ls /dev/shm

# Verify System V IPC support

$ ipcs

# Verify POSIX message queues filesystem (Linux)

$ ls /dev/mqueue

# Verify compiler

$ gcc --version

# Check PIPE_BUF limit

$ getconf PIPE_BUF /

Time Investment

- Foundation projects (1-4): Weekend each (4-8 hours)

- Synchronization projects (5-11): 1 week each (10-20 hours)

- Shared memory projects (12-15): 1-2 weeks each (15-30 hours)

- RPC projects (16-18): 1-3 weeks each (15-40 hours)

- Total sprint: 4-6 months if done sequentially

Important Reality Check

IPC is difficult to debug. Deadlocks and hangs are normal. Processes will block forever if you forget one close(). System V objects can persist after crashes and must be cleaned manually. Embrace the pain; it forces you to build a correct mental model.

Big Picture / Mental Model

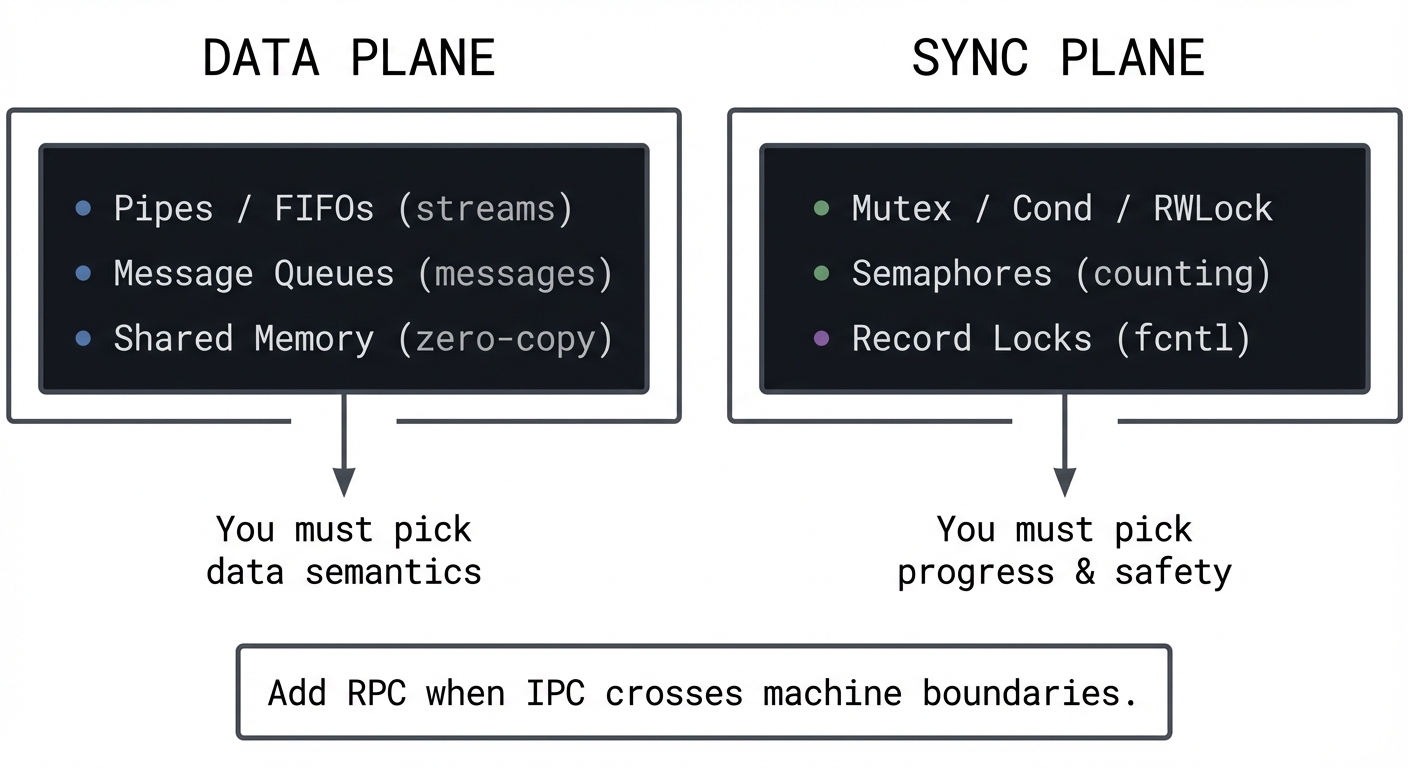

IPC design is two orthogonal problems:

- Data plane: How bytes or messages move between processes.

- Sync plane: How processes coordinate access and progress.

DATA PLANE SYNC PLANE

┌────────────────────────────┐ ┌──────────────────────────────┐

│ Pipes / FIFOs (streams) │ │ Mutex / Cond / RWLock │

│ Message Queues (messages) │ │ Semaphores (counting) │

│ Shared Memory (zero-copy) │ │ Record Locks (fcntl) │

└──────────────┬─────────────┘ └──────────────┬───────────────┘

│ │

v v

You must pick You must pick

data semantics progress & safety

Add RPC when IPC crosses machine boundaries.

A solid IPC design answers six questions:

- Who owns the data? (single writer vs multiple writers)

- What is the unit of transfer? (bytes vs messages vs records)

- How is backpressure handled? (blocking, drop, bounded queue)

- How is access coordinated? (mutex, sem, lock-free)

- How is cleanup handled? (unlink semantics, crash recovery)

- How is observability achieved? (logging, metrics, tracing)

Theory Primer (Read This Before Coding)

This is the mini-book. Every project assumes you can answer the questions in these chapters.

Chapter 1: Processes, File Descriptors, and IPC Object Lifecycles

Fundamentals

Processes are isolated by design. Each process has its own virtual address space, its own file descriptor table, and its own view of resources. IPC exists because real systems need coordination and data sharing across that isolation boundary. In Unix, almost every IPC mechanism is represented by a file descriptor (pipes, sockets, POSIX shared memory, POSIX message queues), which means the same I/O primitives (read, write, close, poll, select) can be reused. The first mental model to build is that a file descriptor is not the resource itself; it is a per-process handle to a kernel object that has its own lifetime rules.

Every IPC mechanism has a lifecycle: create/open, use, and destroy/unlink. The details differ. Pipes are ephemeral and disappear when all descriptors are closed. POSIX named IPC objects are reference-counted and can be unlinked while still open, just like files. System V objects are persistent kernel objects that survive process exit and must be explicitly removed (e.g., ipcrm). This difference alone explains a large portion of IPC bugs: developers forget to clean up System V semaphores or shared memory segments, then everything fails on the next run due to stale state or exceeded kernel limits.

File descriptor inheritance across fork() and exec() is the next critical mental model. fork() duplicates the parent’s file descriptor table, so both parent and child point to the same underlying kernel objects and offsets. exec() replaces the process image but (unless FD_CLOEXEC is set) preserves file descriptors, which is exactly how shells build pipelines. This is why closing unused file descriptors is not optional: open descriptors in any process keep the underlying IPC object alive and can prevent EOF from propagating or keep locks held.

Finally, understand blocking and atomicity. Most IPC calls are blocking by default: read() waits for data, write() waits for space, sem_wait() waits for a token. Non-blocking mode changes that behavior but introduces EAGAIN handling and often requires poll or select. Atomicity rules (for example, PIPE_BUF) determine whether multiple writers can interleave data. If you do not understand these guarantees, you will build IPC systems that appear to work in tests but fail under load.

IPC is also about failure containment. Processes isolate faults; when one crashes, others can keep running. IPC lets you benefit from isolation without losing collaboration. This is why many large systems prefer multi-process designs over a single multi-threaded process: a crash in one worker does not bring down the entire system, but the workers can still share state through IPC. Understanding this trade-off is key to deciding when to split a system into multiple processes.

A second perspective is that IPC is a contract between producers and consumers. The kernel enforces some parts of this contract (permissions, blocking, limits) but most semantics are your responsibility. You decide what constitutes a message, when a message is complete, and how to recover from partial state. The earlier you define these rules, the fewer bugs you will have later.

Finally, IPC is tied to portability and standards. POSIX IPC APIs are widely supported but not uniform across all Unix variants, while System V APIs are older but entrenched. If you build a portable system, you must know which APIs are available and how they differ. Stevens’ Vol 2 exists largely because these differences matter in real production systems.

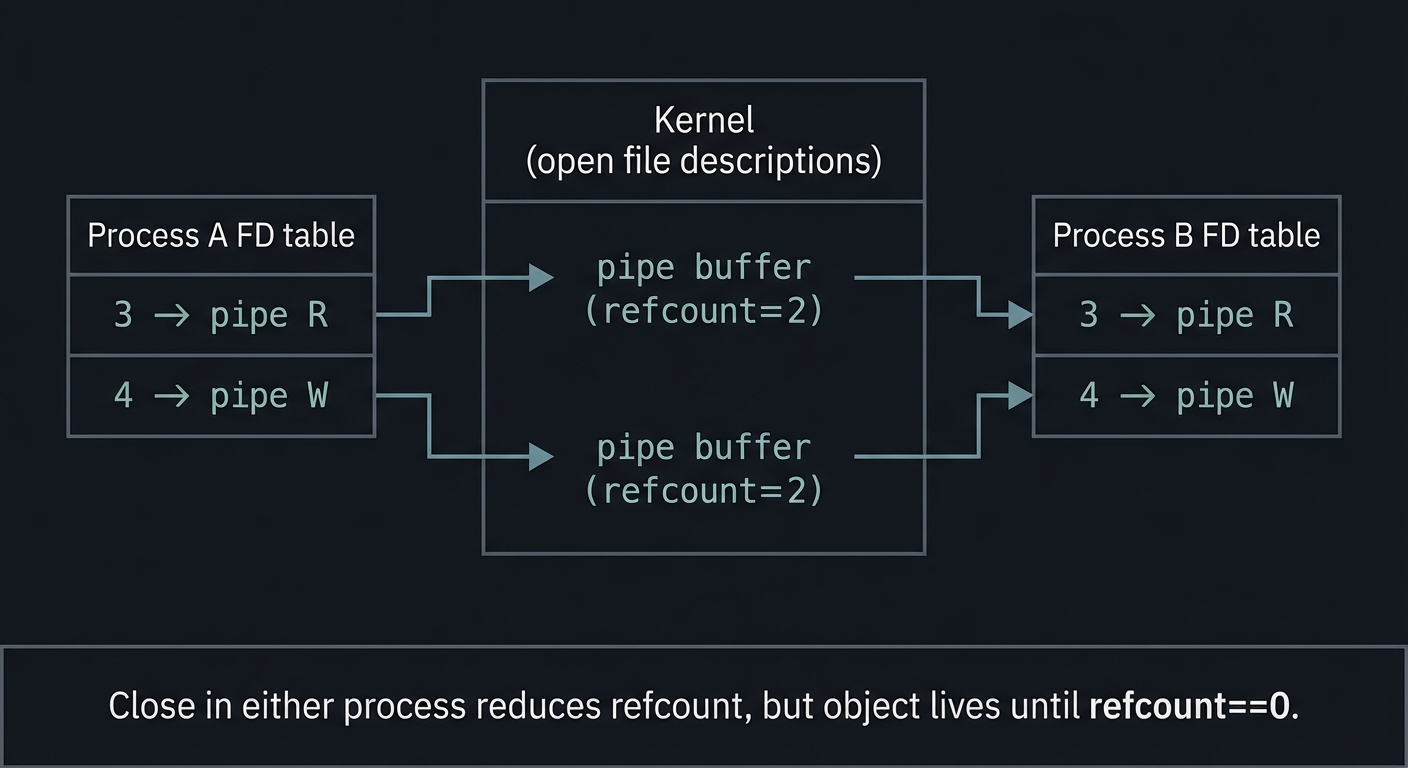

Deep Dive

A Unix process has a file descriptor table that maps small integers (0, 1, 2, …) to open file descriptions in the kernel. The open file description tracks file position, status flags, and references to the underlying inode or IPC object. When you fork(), the child inherits a copy of the descriptor table, but both parent and child refer to the same open file descriptions. That means changing flags (like O_NONBLOCK) or closing a descriptor in one process affects the shared kernel object, but not the other process’s descriptor table. This matters for IPC because it means all participants are manipulating a shared kernel-backed resource even when they think they are isolated.

IPC objects have names and namespaces. POSIX IPC names are string-based and look like /myqueue or /myshm. On Linux, POSIX message queues live in /dev/mqueue and POSIX shared memory lives in /dev/shm. System V IPC uses numeric keys (key_t) produced by ftok() or explicit integers. Because System V objects are persistent, the key space becomes part of your system design; your programs must agree on keys or coordinate creation, and you must handle the case where an object already exists from a previous run.

Permissions apply too. IPC objects have modes (like files) that enforce ownership and access control. This is not optional: a queue created with mode 0600 will not be readable by another user. When a program fails mysteriously, always check permissions first. For System V IPC, permissions are stored in the ipc_perm structure and are inspected via ipcs -l and ipcs -i. For POSIX IPC, ls -l /dev/shm and ls -l /dev/mqueue show the backing objects.

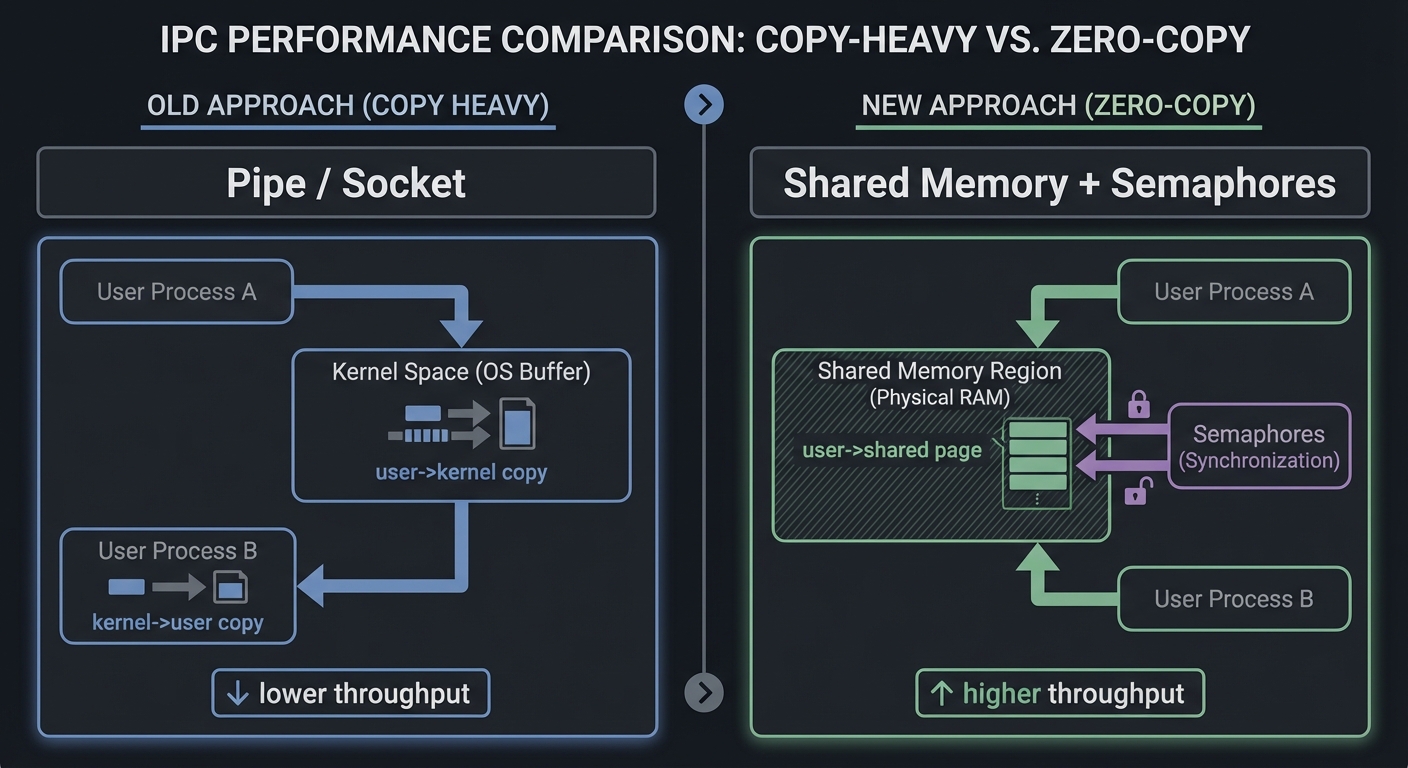

Another deep detail is the relationship between data plane and control plane. A pipe moves bytes but provides no explicit notion of messages. If you need message boundaries, you must implement your own framing protocol (length prefix, delimiters, etc.). Message queues and RPC provide message boundaries, but require explicit synchronization and handling of backpressure when queues fill. Shared memory is the fastest data plane, but it provides no synchronization at all; you must bring your own locks, semaphores, or lock-free structures. This is why many IPC designs use pairs: shared memory for data, semaphores for synchronization.

Failure modes are where IPC becomes tricky. If a process dies without cleanup, System V IPC objects persist. If a writer crashes, a reader might block forever unless EOF propagation occurs (pipes) or the reader checks for timeouts (message queues, semaphores). If two processes deadlock on semaphores or record locks, they will wait forever. If signals interrupt syscalls (EINTR), your program must restart or handle partial state. Correct IPC systems are robust systems: they are designed with failure in mind, not as an afterthought.

Finally, note that the kernel limits on IPC objects are real. Message queues have limits on message size and number of messages. Pipes have finite capacity. Semaphores have maximum counts. You must design with these limits in mind or your system will fail unpredictably under load. For example, POSIX message queues on Linux default to msg_max=10 and queues_max=256 unless tuned via /proc/sys/fs/mqueue (mq_overview(7)). A good IPC design starts by understanding these constraints and writing code that fails gracefully when limits are reached.

At a deeper level, understanding duplication of file descriptors is crucial. dup() and dup2() create a new file descriptor that points to the same open file description, which means they share file offsets and flags. This is exactly how dup2() can redirect stdout to a pipe: it makes FD 1 refer to the same open file description as the pipe’s write end. If you later close the original pipe FD, stdout continues to work because the underlying kernel object still has a reference. This detail explains why redirection works and why closing the wrong descriptor can break an entire pipeline.

Signals and EINTR are another subtlety. Many IPC-related syscalls can be interrupted by signals, returning -1 with errno=EINTR. Robust programs either restart the call or design for partial completion. Some systems use sigaction with SA_RESTART, but you should not rely on it universally. Projects with blocking reads or semaphores will expose this if you attach a debugger or send signals during operation.

Multiplexing is also part of the deep model. When multiple IPC channels are active, you must coordinate reads and writes without blocking on the wrong one. The traditional tools are select() and poll(), and modern systems use epoll or kqueue. Even if you do not implement a full event loop in this guide, you must understand how non-blocking I/O pairs with multiplexing to build responsive IPC systems.

Finally, you must internalize the create-or-open race. POSIX IPC objects and files can be created concurrently by multiple processes. If two processes call mq_open or shm_open with O_CREAT at the same time, the first wins. If you need to ensure exclusive creation, you must use O_EXCL and handle EEXIST. This is a common source of race conditions in IPC startup code.

System V IPC introduces another deep detail: key collisions. The ftok() function derives keys from filesystem metadata, which can collide across unrelated programs. This is why robust systems often use well-known numeric keys or dedicate a directory for IPC keys with strict permissions. Always plan for EEXIST when creating System V objects, and decide whether you will reuse or recreate the object.

You should also familiarize yourself with kernel limits. ipcs -l shows limits on message queues, semaphores, and shared memory. These limits are not theoretical; exceeding them will cause IPC creation to fail. For long-running systems, monitoring these limits is part of operational hygiene.

Another lifecycle detail is that some locks and IPC objects are attached to the open file description, not the file descriptor number. This explains why dup() and dup2() can share locks and file offsets. It also explains why closing one descriptor might not release a lock if another descriptor still references the same open file description. Understanding this model helps you debug record-locking anomalies later in the projects.

How This Fits on Projects

Projects 1-6 exercise file descriptors, inheritance, and object lifecycles. Projects 7-15 add synchronization and shared memory. Projects 16-18 add process boundaries across machines. Every single project requires mastery of this chapter.

Definitions & Key Terms

- Open file description: Kernel object referenced by one or more file descriptors, tracking file offset and flags.

- File descriptor table: Per-process mapping from small integers to open file descriptions.

- FD_CLOEXEC: Flag that closes a descriptor across

exec(). - IPC object: Kernel resource used for communication or synchronization.

- Persistence: Whether IPC objects survive process exit.

Mental Model Diagram

Process A FD table Kernel (open file descriptions) Process B FD table

┌───────────────┐ ┌────────────────────────────┐ ┌───────────────┐

│ 3 -> pipe R │ ------> │ pipe buffer (refcount=2) │ <------│ 3 -> pipe R │

│ 4 -> pipe W │ ------> │ pipe buffer (refcount=2) │ <------│ 4 -> pipe W │

└───────────────┘ └────────────────────────────┘ └───────────────┘

Close in either process reduces refcount, but object lives until refcount==0.

How It Works (Step-by-Step)

- A process creates or opens an IPC object (pipe, queue, shm) and receives an FD or ID.

- The process forks or hands the identifier to another process.

- Both processes operate on the same kernel object through their own handles.

- The kernel mediates access, applies permissions, and enforces limits.

- When all handles are closed or the object is unlinked/removed, the kernel releases it.

Invariants:

- IPC objects outlive the creating process if references remain.

- Closing all handles releases the object (POSIX); System V requires explicit removal.

- A blocked operation must eventually complete or time out to avoid deadlock.

Failure Modes:

- Forgotten closes keep objects alive and prevent EOF.

- Stale System V objects cause

EEXISTor stale data. - Incorrect permissions cause silent failures or

EACCES.

Minimal Concrete Example

int fd = open("/tmp/data.txt", O_RDONLY);

if (fd == -1) { perror("open"); exit(1); }

pid_t pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

// Child inherits fd; read same file description

char buf[64];

read(fd, buf, sizeof(buf));

_exit(0);

}

// Parent can close independently; underlying object lives if child still holds it

close(fd);

waitpid(pid, NULL, 0);

Common Misconceptions

- “Closing a file descriptor in one process closes it for all.” (False)

- “POSIX IPC objects disappear when a process exits.” (Only if last reference is closed)

- “System V IPC cleans itself up.” (False; you must remove it)

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- Why do pipes and POSIX IPC objects disappear automatically but System V objects do not?

- What happens to file descriptors across

exec()and how doesFD_CLOEXECchange this? - Why can a pipe reader block forever even after a writer process exits?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- POSIX IPC objects are reference-counted and unlinkable; System V objects persist until explicitly removed.

exec()preserves file descriptors unlessFD_CLOEXECis set, which closes them automatically.- The reader may block if another process still holds a write descriptor open, preventing EOF.

Real-World Applications

- Shells wiring pipelines (

bash,zsh) - Databases coordinating worker processes

- Build systems streaming compiler output

- Daemons coordinating with supervisors and loggers

Where You Will Apply It

Projects 1-18 (all of them).

References

- Stevens, UNP Vol 2 — Ch. 1-3

- Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment — Ch. 3, 8, 15

- The Linux Programming Interface — Ch. 43-44

pipe(7),mq_overview(7),shm_overview(7)(man7.org)

Key Insight

IPC is not just about moving bytes; it is about managing shared kernel objects with precise lifetime and synchronization rules.

Summary

You now know how Unix represents IPC objects, how descriptors and namespaces work, and why object lifetime rules dominate IPC correctness.

Homework / Exercises

- Trace a simple

ls | wc -lpipeline withstraceand list every FD operation. - Create a System V message queue, exit without cleanup, and observe persistence with

ipcs. - Explain the difference between POSIX and System V persistence in your own words.

Solutions

- Use

strace -f -e trace=pipe,dup2,close,execveto see FDs created and inherited. - Run

ipcs -qafter exiting; the queue remains untilipcrm -q. - POSIX uses names and reference counting; System V uses kernel IDs that persist.

Chapter 2: Pipes and FIFOs (Byte-Stream IPC)

Fundamentals

Pipes and FIFOs are the simplest IPC mechanisms in Unix. They are byte streams with no inherent message boundaries. Pipes are created with pipe() and are anonymous: they exist only within a process family (usually parent and child). FIFOs (named pipes) are created with mkfifo() and appear as a special file in the filesystem, allowing unrelated processes to communicate. Both are unidirectional: one end is for reading, the other for writing. Full-duplex communication requires two pipes or two FIFOs.

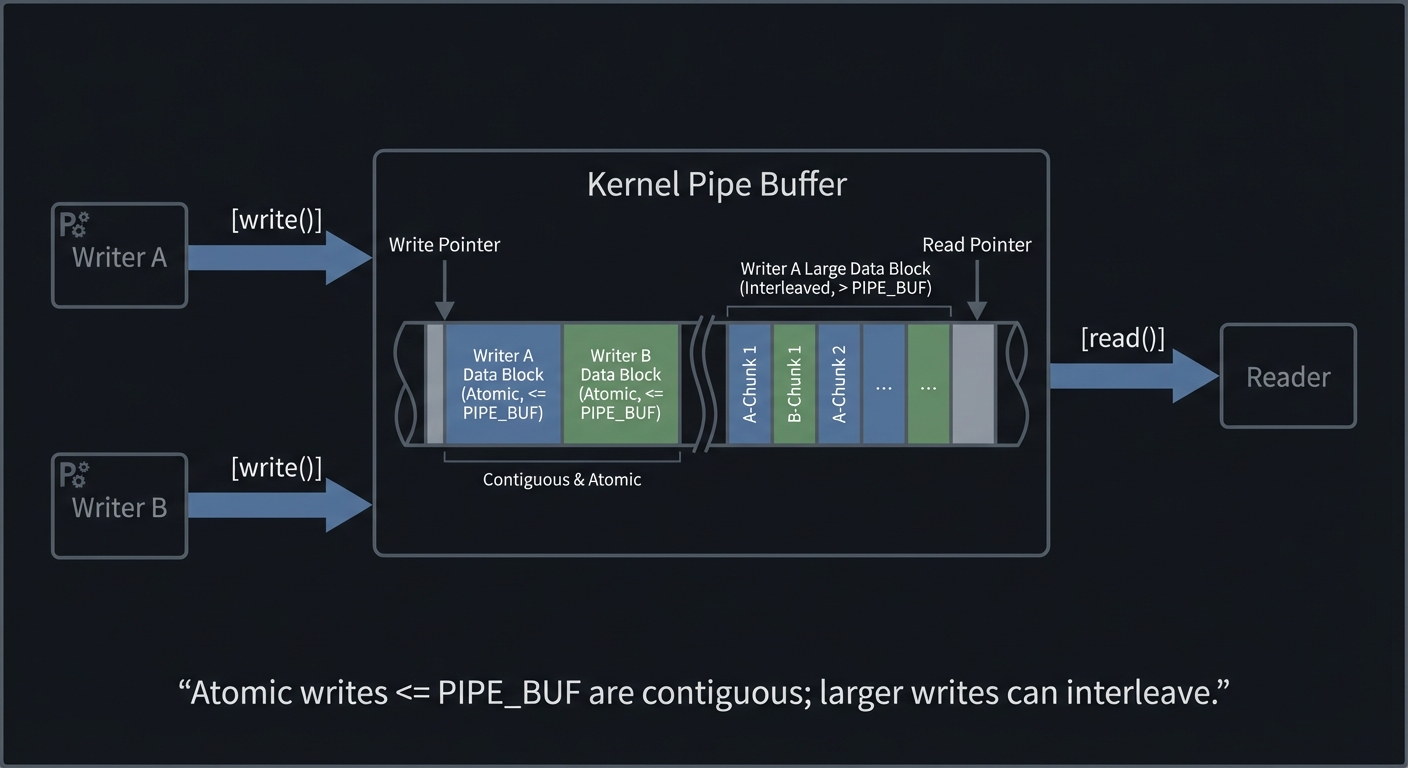

The most important pipe guarantee is atomicity for small writes. POSIX guarantees that writes of less than PIPE_BUF bytes are atomic. On Linux, PIPE_BUF is 4096 bytes, and POSIX requires at least 512 bytes. This means multiple writers can safely write small records without interleaving, but larger writes can be split and interleaved by the kernel. This is the origin of the classic bug where log messages get garbled under load.

Blocking behavior is equally important. By default, read() blocks when the pipe is empty and write() blocks when the pipe is full. If all writers close their ends, readers see EOF (read() returns 0). If all readers close their ends, writers get SIGPIPE and write() fails with EPIPE. FIFOs add an extra subtlety: opening a FIFO for reading blocks until a writer opens it, and opening for writing blocks until a reader opens it (unless O_NONBLOCK is used). These semantics are both powerful and dangerous; failing to open or close correctly is a common deadlock source.

Despite their simplicity, pipes and FIFOs remain widely used because they integrate perfectly with Unix philosophy. They compose well with shell pipelines, can be inspected with standard tools, and are easy to debug. Their limitations (lack of message boundaries, local-only, limited capacity) drive the need for other IPC mechanisms, but for streaming data they remain unmatched in simplicity.

Another essential detail is directionality. Pipes and FIFOs are single-direction streams. A bidirectional channel requires two pipes (or two FIFOs), one for each direction. Many beginners attempt to use a single FIFO for request and response, which can work for strict request/response patterns but becomes fragile under concurrency. The clean solution is two named FIFOs or a per-client FIFO for replies, which mirrors how higher-level protocols separate request and response channels.

Pipes also interact with stdio buffering. If a child process writes to stdout using stdio, data may be buffered and not appear immediately in the parent. This is why interactive programs often force line buffering when stdout is not a terminal. Understanding buffering modes (unbuffered, line buffered, block buffered) helps you debug mysteriously delayed output.

Finally, pipes and FIFOs are local IPC only. The moment communication crosses machine boundaries, you must use sockets or RPC. Recognizing this boundary early prevents overengineering: pipes are perfect for local pipelines, but useless for distributed systems.

One practical rule: if you need message boundaries, you must create them. For example, write fixed-size records or prefix each record with its length. Pipes and FIFOs will not preserve your record boundaries for you.

Deep Dive

A pipe is a kernel buffer with two file descriptors: one for reading and one for writing. The kernel maintains a circular buffer and a set of wait queues. When a writer writes, the kernel copies bytes into the buffer; when a reader reads, the kernel copies bytes out. This makes pipes fast enough for many use cases but still involves two copies (user to kernel, kernel to user). The pipe buffer has a finite capacity (typically 16 pages by default on Linux) and can be resized with F_SETPIPE_SZ for some workloads. However, capacity is not guaranteed; pipe(7) warns that applications must not rely on a fixed capacity. Design your programs to consume data promptly or apply backpressure intentionally.

The key to correct pipe usage is closing unused ends. In a pipeline A | B | C, the parent process might create two pipes and fork three children. Each child must close all pipe ends it does not use, otherwise EOF will never propagate. This is the most common pipeline bug: the last process blocks forever because a write end is still open in some other process. This is why shells are careful about closing descriptors in the parent and children.

Pipes are streams, not messages. If you need message boundaries, you must implement framing: length-prefixed records, delimiter-based records, or fixed-size records smaller than PIPE_BUF to preserve atomicity. FIFOs allow unrelated processes but add name-based coordination and open-time blocking. To avoid blocking on FIFO open, you can open both ends in the same process (open(O_RDWR)) or use O_NONBLOCK and retry. Many production FIFO servers open the FIFO in non-blocking mode and then switch to blocking reads after a writer appears, to avoid startup deadlocks.

There are also two-way pipe patterns. For a bidirectional client-server, you often create two pipes: one for client->server and one for server->client. popen() is effectively a standardized version of this pattern for one-way communication, spawning a process and connecting its stdin or stdout to a pipe. Your Project 3 reimplements this and teaches the exact trade-offs of popen(): you must manage fork()/exec() plus parent-side fdopen() and ensure pclose() waits for the child.

Failure modes include partial reads/writes, signals interrupting syscalls (EINTR), and SIGPIPE. Robust pipe code checks return values, loops on partial writes, handles EINTR, and either ignores SIGPIPE or treats it as a clean shutdown. Performance pitfalls include buffering mismatches and small writes that trigger syscalls too frequently. A common optimization is to batch output in user space before writing to the pipe, but be careful to preserve atomicity boundaries when multiple writers are involved.

Complex pipelines highlight how pipes interact with process management. For an N-command pipeline, you typically create N-1 pipes, then fork N times. Each child process sets up its stdin/stdout by dup2() to the appropriate pipe ends and closes all other pipe ends. The parent closes all pipe ends and waits for all children. This pattern is deceptively simple but can easily leak FDs or deadlock if you close in the wrong order. Drawing a table of FDs for each process is the safest way to reason about correctness.

Non-blocking mode changes everything. With O_NONBLOCK, reads return EAGAIN instead of blocking when no data is available, and writes return EAGAIN when the pipe buffer is full. To build a responsive pipeline, you can combine non-blocking pipes with poll() or select() to wait until a FD is ready. This introduces a control loop that is the precursor to event-driven servers. It is worth experimenting with this pattern to understand how IPC scales when multiple channels are active.

SIGPIPE deserves special attention. By default, writing to a pipe with no readers terminates the process. Many systems ignore SIGPIPE and handle EPIPE manually because abrupt termination is rarely desirable. If your pipeline executor or popen() implementation unexpectedly exits, check whether a downstream process closed its read end and triggered SIGPIPE.

FIFOs introduce additional lifecycle complexity. Because they live in the filesystem, they are subject to permissions, stale files, and cleanup responsibilities. A common pattern is to use a well-known FIFO for server announcements, then create per-client FIFOs for replies. Another pattern is to use a unique FIFO per client identified by PID, which reduces contention but requires careful cleanup. These patterns are practical and mirror how larger systems use temporary sockets or domain sockets for per-client channels.

Performance tuning for pipes often involves batching. If you write one byte at a time, syscall overhead dominates. If you buffer and write in larger chunks, throughput improves but latency might increase. A mature pipeline balances these trade-offs depending on whether throughput or responsiveness is more important.

It is also worth understanding that pipes can be combined with process substitution and shell redirection. This is not just a shell feature; it teaches the same FD wiring logic your pipeline executor uses. Practicing this mentally with real shell commands is a powerful debugging technique.

When multiple pipes are active (for example, a process that reads from several children), you must multiplex. The standard approach is to set all pipes to non-blocking and use poll() or select() to wait for readiness. This pattern prevents one slow pipe from blocking all others, and it is the basis for multi-process log collectors and supervisors.

Another pipeline detail is error propagation. If a middle command fails, upstream writers may get SIGPIPE and downstream readers may see EOF earlier than expected. A robust pipeline executor collects child exit statuses and reports the first failure clearly, rather than just returning the final command’s status. This is one reason shells like bash have options such as pipefail.

A useful validation technique is to deliberately insert sleeps in different pipeline stages and observe how backpressure propagates. This makes the pipe buffer limits visible and helps you reason about throughput under load.

Testing with very large writes (greater than PIPE_BUF) is a quick way to observe interleaving and prove your framing logic works.

How This Fits on Projects

Projects 1-3 are pipe and FIFO heavy. Projects 4-6 contrast pipes with message queues. Projects 16-18 use pipes implicitly in RPC stubs and server management. Understanding pipe semantics is foundational.

Definitions & Key Terms

- PIPE_BUF: Maximum size of an atomic write to a pipe (>=512, Linux 4096).

- FIFO: Named pipe, visible in filesystem.

- SIGPIPE: Signal sent to a process that writes to a pipe with no readers.

- Framing: Encoding message boundaries in a byte stream.

Mental Model Diagram

Writer A Writer B Reader

\ / /

\ / /

v v v

[write()] [write()] -> [ Kernel Pipe Buffer ] -> [read()]

Atomic writes <= PIPE_BUF are contiguous; larger writes can interleave.

How It Works (Step-by-Step)

pipe()creates two file descriptors:fd[0](read) andfd[1](write).- The process forks; parent and child now share the same pipe buffer.

- Each process closes the pipe end it does not use.

- Writer writes bytes; reader reads bytes.

- When all writers close, readers see EOF.

Invariants:

- At least one writer must remain open to avoid EOF.

- Writes <= PIPE_BUF are atomic.

Failure Modes:

- Unclosed write end prevents EOF.

- Writer gets SIGPIPE if no readers.

Minimal Concrete Example

int fd[2];

pipe(fd);

if (fork() == 0) {

close(fd[1]);

char buf[128];

read(fd[0], buf, sizeof(buf));

_exit(0);

}

close(fd[0]);

write(fd[1], "hello", 5);

close(fd[1]);

Common Misconceptions

- “Pipes preserve message boundaries.” (False)

- “EOF happens when the writer exits.” (False if another process still has the write end open)

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- Why does a reader block even after the writer process exits?

- How does

PIPE_BUFaffect multiple writers? - How do FIFOs differ from pipes in terms of namespace and opening semantics?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- Another process still holds a write descriptor open, so EOF does not occur.

- Writes <= PIPE_BUF are atomic; larger writes may interleave.

- FIFOs are named filesystem objects; opening blocks until the other side opens (unless

O_NONBLOCK).

Real-World Applications

- Shell pipelines

- Log processing chains

- Simple client-server tools like

logger | grep | awk

Where You Will Apply It

Projects 1-3.

References

pipe(7),fifo(7)(man7.org)- Stevens, UNP Vol 2 — Ch. 4

- The Linux Programming Interface — Ch. 44

Key Insight

Pipes are deceptively simple; their correctness depends on precise control of file descriptor lifetimes.

Summary

You now understand how pipes and FIFOs work, their blocking semantics, and how atomicity affects multi-writer systems.

Homework / Exercises

- Build a FIFO-based logger that multiple processes can write to simultaneously without interleaving.

- Modify your pipeline executor to handle non-blocking pipes and

EAGAIN.

Solutions

- Ensure each write is <= PIPE_BUF or implement length-prefixed framing.

- Use

fcntlto setO_NONBLOCKand wrap writes in retry loops withpoll().

Chapter 3: Message Queues (POSIX and System V)

Fundamentals

Message queues are IPC mechanisms that preserve message boundaries and allow asynchronous communication. Unlike pipes, they are not streams; each send produces a discrete message and each receive returns one complete message. This makes message queues an excellent fit for request/response patterns, task dispatch, and event-driven architectures.

POSIX message queues use string names (e.g., /jobs) and are manipulated with mq_open, mq_send, mq_receive, and mq_close. They support message priorities, so higher priority messages are delivered first. On Linux, POSIX message queues appear under /dev/mqueue. System V message queues use numeric keys (key_t) and operations like msgget, msgsnd, and msgrcv. System V messages include a mtype field that lets receivers filter for specific types. Both mechanisms provide kernel-managed queues with configurable size limits, and both block when queues are empty or full unless non-blocking flags are used.

The most important difference between POSIX and System V message queues is lifetime and namespace. POSIX queues are reference-counted and can be unlinked, similar to files. System V queues persist until explicitly removed with msgctl(IPC_RMID) or ipcrm, even after all processes exit. This persistence can be useful for long-running services but is a common source of leaks and confusing bugs during development.

Queue capacity is finite. POSIX message queues on Linux default to msg_max=10 messages per queue and queues_max=256 total queues unless tuned via /proc/sys/fs/mqueue (mq_overview(7)). Exceeding these limits causes mq_open or mq_send to fail or block. System V queues also have size limits governed by kernel parameters. Designing robust message queues means thinking about backpressure, bounded buffers, and what happens when producers outpace consumers.

Message queues are also a scheduling tool. Because the kernel maintains an ordered queue, you can treat the queue itself as a backlog of work. This allows systems to decouple producers from consumers: producers can run fast without overwhelming consumers, and consumers can scale horizontally by reading from the queue. This decoupling is one of the reasons message queues are commonly used in job processing systems.

Another key detail is message size constraints. Unlike pipes, queues have explicit maximum message sizes, which can force you to design a serialization protocol carefully. Large payloads may need to be stored in shared memory or files, with the queue carrying only metadata and pointers. This pattern shows up in real systems: control-plane messages in a queue, data-plane payloads in shared memory or files.

Finally, message queues are a middle ground between pipes and shared memory. They preserve message boundaries like RPC, but they are local and avoid some network complexity. Understanding when to choose them is a mark of a mature systems programmer.

Persistence also changes workflow. With System V queues, you can crash and restart without losing queued messages, but you must also handle stale state. With POSIX queues, you can unlink the queue and still keep using it via existing descriptors, which enables safe restarts if done carefully.

Deep Dive

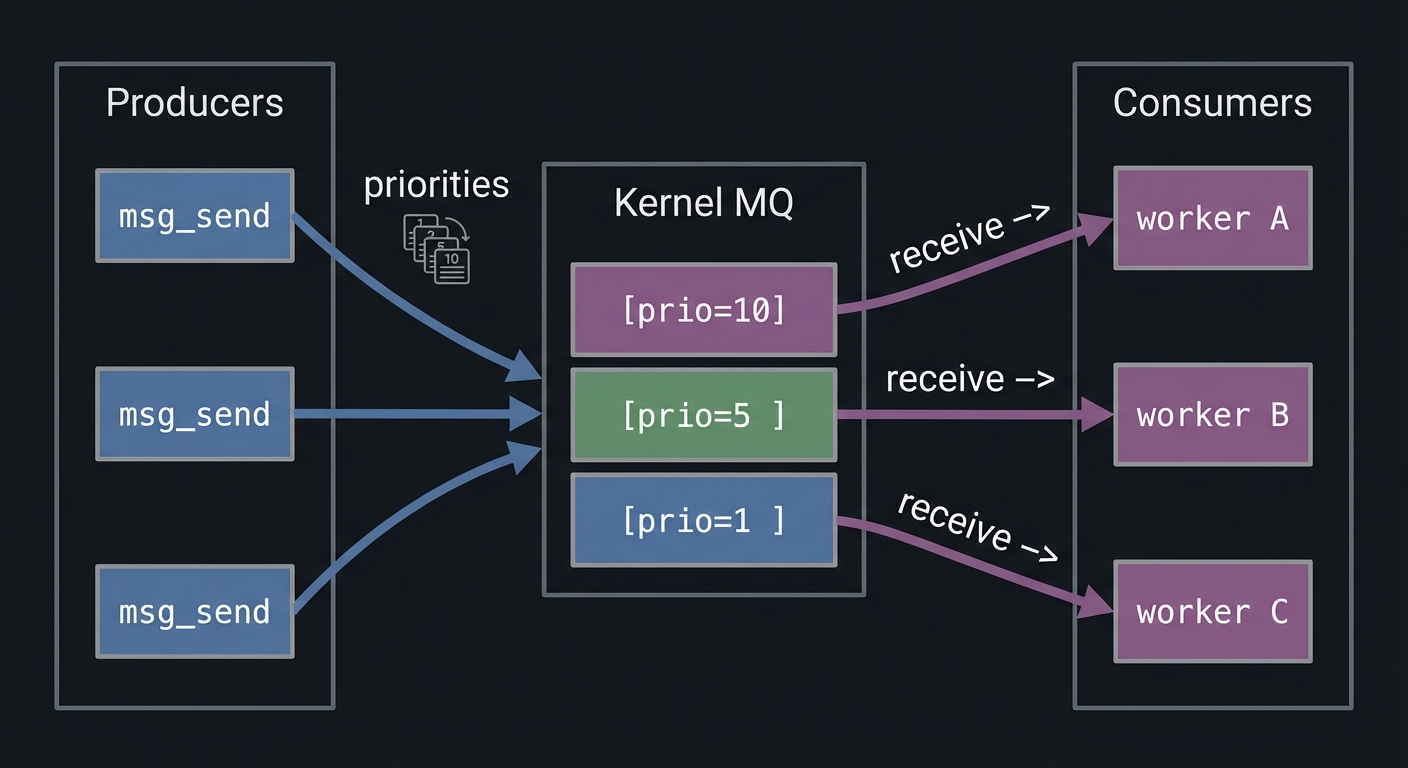

A message queue is essentially a kernel-managed list of messages, each with metadata (size, priority or type). When a sender calls mq_send, the kernel checks permissions, verifies the message size, and either enqueues or blocks if the queue is full. Receivers call mq_receive to dequeue the highest-priority message. Priorities are strict: a priority 10 message will always be delivered before a priority 1 message, regardless of arrival order. This makes POSIX message queues powerful for emergency signals or high-priority jobs, but it can also cause starvation if low-priority messages never get serviced.

System V message queues use mtype to allow selective receive. The msgrcv call can specify msgtyp to select a specific type or a range of types. This enables multiplexing multiple logical channels within a single queue. However, System V APIs are more complex and have different blocking and error semantics. For example, msgsnd can block or fail with EAGAIN if IPC_NOWAIT is used. You must also be careful about struct packing: the message buffer must start with a long mtype, and the size argument excludes this field. These details are a classic source of bugs.

POSIX queues integrate with signals and threads via mq_notify. You can request a signal when a queue transitions from empty to non-empty, or request a thread-based notification. This is a powerful pattern for event-driven servers: the queue acts as a kernel-backed event source. The downside is that mq_notify is one-shot; you must re-register after each notification. Missing this leads to lost wakeups and hung servers.

When designing with message queues, you must decide on serialization and framing. The kernel preserves message boundaries, but you still need a protocol for your application messages. XDR, protobufs, or simple fixed-layout structs can be used. Because queues are bounded, you must define what happens when full: block, drop, or apply backpressure to upstream components. For high-throughput systems, message queues may be too slow; shared memory with a ring buffer is often faster. Projects 4-6 make this trade-off concrete by comparing POSIX and System V queues and benchmarking them against other IPC mechanisms.

POSIX message queues expose explicit attributes through mq_attr: mq_flags (blocking vs non-blocking), mq_maxmsg (maximum messages), and mq_msgsize (max message size). These are not just configuration details; they define system behavior under load. If a producer attempts to send a larger message than mq_msgsize, it fails. If the queue reaches mq_maxmsg, mq_send blocks. A mature design treats these constraints as part of the protocol.

System V message queues have their own quirks. The msgsnd and msgrcv calls accept flags such as IPC_NOWAIT (non-blocking) and MSG_NOERROR (truncate overly large messages instead of failing). msgrcv also supports selecting messages by type, which lets you multiplex logical channels in a single queue. This is powerful, but it can cause surprising behavior if multiple clients share the same queue and use overlapping message types.

Message queues also require careful handling of serialization. The kernel does not know your data structures; it only sees bytes. If you send a struct containing pointers, the receiving process will get meaningless addresses. Always serialize into flat buffers or use a serialization format like XDR or protobuf. This problem becomes very obvious in distributed systems but exists equally in local IPC.

Design patterns matter here. Many production systems use a dispatcher that reads from a queue and forwards jobs to worker processes. This isolates queue logic from worker logic and allows you to implement backpressure, batching, or rate limiting in one place. Another pattern is a dead-letter queue for messages that fail processing, which helps you avoid infinite retry loops.

Finally, note that POSIX message queues can integrate with signals or threads via mq_notify. This allows event-driven designs where the queue itself wakes the server. But mq_notify is one-shot; if you forget to re-register, your server will stop receiving notifications. This is a subtle but common bug, and it teaches you to think about state transitions carefully.

Permissions are another deep detail. Both POSIX and System V queues have ownership and mode bits. If a queue is created with 0600, other users cannot read it. This can lead to confusing failures in multi-user environments. Always design your queue permissions intentionally and document them.

POSIX queues also support timed receive and timed send functions (mq_timedreceive, mq_timedsend). These allow you to build systems that fail fast rather than blocking forever. They are especially valuable in systems where latency matters or where you want to avoid deadlocks.

Queues also expose instrumentation hooks. POSIX provides mq_getattr() to read the current message count (mq_curmsgs), which allows you to build monitoring and alerting around queue depth. System V provides msgctl to query msg_qnum and msg_qbytes. These metrics are essential in production because they reveal backpressure and overload.

System V msgrcv also supports negative msgtyp values, which select the first message with type less than or equal to the absolute value. This is a powerful but rarely used feature that can implement priority-like behavior in System V queues. Understanding these options helps you reason about legacy systems that use them.

Cleanup strategy is part of correctness. For POSIX queues, mq_unlink() removes the name but existing descriptors remain valid. For System V, msgctl(IPC_RMID) immediately marks the queue for deletion. Your shutdown code should handle both patterns cleanly.

Queue depth also affects latency. A full queue means new messages wait longer before processing, which can violate latency SLAs. This is why production systems often include queue depth alerts and autoscaling triggers tied to message backlog.

If you need to persist large payloads, a common pattern is to store the payload in shared memory and send only a handle or offset through the queue. This reduces queue pressure while still preserving message boundaries.

This pattern mirrors modern systems that combine a fast queue with a shared-memory data plane to scale throughput without sacrificing structure.

How This Fits on Projects

Projects 4-6 are dedicated to message queues. Projects 18 uses RPC and shared memory but still benefits from message-based thinking.

Definitions & Key Terms

- Message boundary: The unit of delivery; messages are not split or merged.

- Priority: POSIX attribute that orders delivery by message priority.

- mtype: System V message type used for filtering receives.

- mq_attr: POSIX structure defining max messages and message size.

Mental Model Diagram

Producers Kernel MQ Consumers

┌──────────┐ ┌────────────────┐ ┌───────────┐

│ msg_send │ priorities │ [prio=10] │ receive ->│ worker A │

│ msg_send │ ------------> │ [prio=5 ] │ receive ->│ worker B │

│ msg_send │ │ [prio=1 ] │ receive ->│ worker C │

└──────────┘ └────────────────┘ └───────────┘

How It Works (Step-by-Step)

- Create/open the queue (

mq_openormsgget). - Configure size and permissions (

mq_attrormsgctl). - Producers enqueue messages.

- Consumers dequeue messages in priority/type order.

- Close and unlink/remove the queue when done.

Invariants:

- Messages are delivered whole.

- Queue size limits are enforced by the kernel.

Failure Modes:

- Full queue causes producers to block or fail.

- Queue persistence causes stale data after crashes.

Minimal Concrete Example

mqd_t mq = mq_open("/jobs", O_CREAT|O_RDWR, 0600, NULL);

const char *msg = "job:42";

mq_send(mq, msg, strlen(msg)+1, 5);

char buf[128];

unsigned prio;

mq_receive(mq, buf, sizeof(buf), &prio);

Common Misconceptions

- “Message queues are always faster than pipes.” (Often false; shared memory or pipes can be faster)

- “POSIX and System V queues behave the same.” (They do not)

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- What is the difference between POSIX priorities and System V

mtype? - Why can a POSIX queue lose notifications if

mq_notifyis not re-armed? - How do queue size limits affect system design?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- POSIX priorities define delivery order; System V types define filtering.

mq_notifyis one-shot and must be registered again after delivery.- They require backpressure or bounded buffering strategies.

Real-World Applications

- Job dispatchers and worker pools

- Logging pipelines with priority alerts

- Event-driven daemons

Where You Will Apply It

Projects 4-6.

References

mq_overview(7)(man7.org)- Stevens, UNP Vol 2 — Ch. 5-6

- The Linux Programming Interface — Ch. 51-54

Key Insight

Message queues trade raw speed for explicit message boundaries and built-in queuing semantics.

Summary

You now understand POSIX and System V message queues, their lifecycles, and their performance trade-offs.

Homework / Exercises

- Implement a length-prefixed protocol on top of a pipe and compare to POSIX MQ.

- Simulate queue overload and design a drop/backpressure policy.

Solutions

- Prefix each record with a 4-byte length; compare throughput and complexity.

- Implement bounded queue and return

EAGAINto producers when full.

Chapter 4: Shared Memory and Memory Mapping (Zero-Copy IPC)

Fundamentals

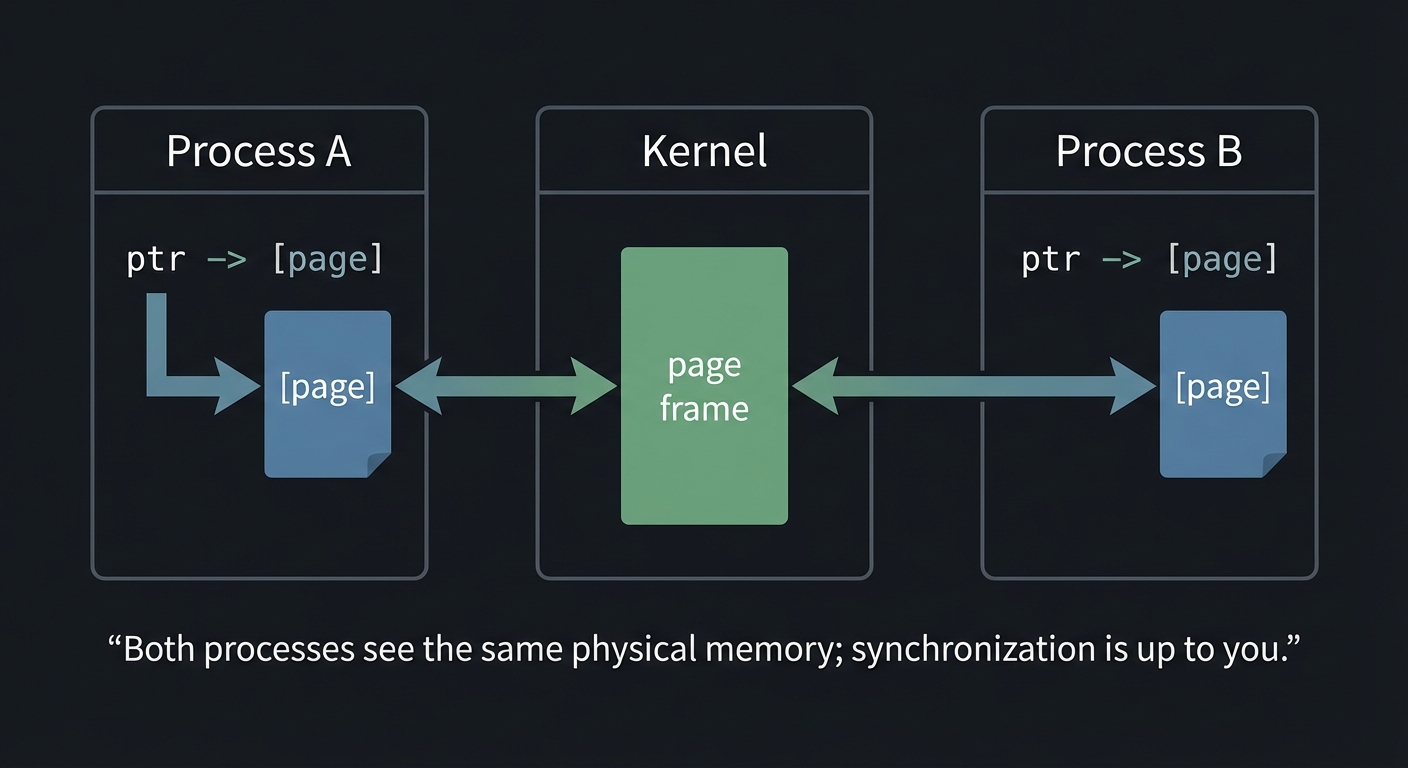

Shared memory is the fastest IPC mechanism because it avoids copying data through the kernel. Instead, multiple processes map the same physical pages into their virtual address spaces, and they read/write directly. POSIX shared memory uses shm_open to create a shared memory object (backed by /dev/shm on Linux), then ftruncate to size it, and mmap to map it. System V shared memory uses shmget and shmat. Both yield an address you can treat like normal memory.

The trade-off is that shared memory provides no synchronization. If two processes write at the same time, data corruption is guaranteed unless you coordinate. Thus shared memory almost always appears with synchronization primitives: semaphores, mutexes in shared memory, or lock-free data structures with atomics. Projects 12-15 explore this spectrum, from semaphore-protected ring buffers to lock-free queues.

mmap() is the bridge between shared memory and persistent storage. A file mapped with MAP_SHARED becomes shared memory backed by disk. Writes are visible to other processes mapping the same region and can be flushed to disk with msync. This is how embedded databases like SQLite or LMDB get high performance: the OS page cache becomes the database cache. Understanding the difference between MAP_SHARED and MAP_PRIVATE is essential; only MAP_SHARED propagates changes across processes and to the underlying file.

Shared memory introduces the concept of addressing. You cannot safely store raw pointers in shared memory unless all processes map the region at the same virtual address. The correct approach is to store offsets from the base of the shared memory region. This is a common pitfall that appears when teams attempt to share complex data structures across processes.

Another key detail is the distinction between anonymous shared memory (e.g., mmap with MAP_SHARED|MAP_ANON) and named shared memory (shm_open). Anonymous shared memory is simple and fast but cannot be reopened by unrelated processes. Named shared memory can be reopened and persists until unlinked, but requires lifecycle management.

Finally, shared memory is backed by the kernel’s page cache (tmpfs on Linux). It can be swapped and is subject to memory pressure. This means shared memory is fast but not magically unlimited. Design your shared memory systems with memory usage limits, cleanup procedures, and graceful failure modes.

Shared memory also changes how you design data structures. Anything that relies on process-local pointers, file descriptors, or thread IDs cannot be stored directly. You must store offsets or IDs and resolve them at runtime. This is why shared-memory designs often look simpler than in-process designs: simplicity reduces pointer-related bugs.

A final fundamental point: shared memory is about locality and lifetime. Use anonymous shared memory for short-lived, tightly coupled processes, and use named shared memory or mmap() when you need independent processes to attach at different times. This distinction becomes important in real systems where processes are restarted independently.

You can also think of shared memory as a building block. It is not a solution by itself; it is raw capability. The correctness and durability of any shared-memory system come from the conventions you layer on top: headers, versioning, checksums, and synchronization rules.

Deep Dive

Shared memory is conceptually simple but operationally tricky. When you map a shared region, the OS uses the same physical frames for multiple processes. Reads and writes are not atomic at the application level; you must decide on a concurrency strategy. For small control data, simple mutexes or semaphores suffice. For high-throughput data, lock-free ring buffers reduce contention but require careful attention to memory ordering, cache coherence, and false sharing.

POSIX shared memory objects behave like files. You create them with shm_open, size them with ftruncate, map them with mmap, and delete them with shm_unlink. Even after unlinking, existing mappings remain valid until unmapped, just like unlinked files. System V shared memory uses shmget to create a segment identified by an integer ID, shmat to attach, shmdt to detach, and shmctl to control or remove it. These objects persist after process exit and must be explicitly removed to avoid leaks.

Mapping and synchronization must consider cache behavior. When two CPU cores read and write the same cache line, they bounce ownership via cache coherence protocols. If you place two frequently updated counters in the same cache line, you will create false sharing and destroy performance. The fix is padding: align hot fields to cache line boundaries (often 64 bytes). For lock-free queues, you must also use atomic operations with correct memory ordering. A producer must publish data before advancing the write index, and the consumer must read the index with acquire semantics to ensure it sees the data. This is why Project 15 is challenging: correctness depends on the memory model, not just logic.

mmap() introduces additional failure modes. If you grow a file, you must remap it or you risk SIGBUS when accessing beyond the mapped region. msync is required for durability; otherwise you have no guarantee data reaches disk after a crash. If multiple processes map the same file and write concurrently, you still need locking (record locks or external coordination) to prevent corruption. You will implement these patterns in Project 14.

Finally, shared memory requires careful cleanup. POSIX objects in /dev/shm can be unlinked; System V objects require shmctl(IPC_RMID). Leaks are common when processes crash. You should always build a cleanup utility that lists and removes stale objects as part of your development workflow.

Shared memory correctness depends on both hardware and software. On the hardware side, CPU caches and store buffers can reorder reads and writes. On the software side, compilers can reorder operations unless you use atomic operations or memory barriers. This is why lock-free programming is hard: you are negotiating with both the compiler and the CPU. Even in lock-based designs, you should understand that locks provide implicit memory barriers that make shared state visible across cores.

Page size and alignment also matter. Most systems use 4KB pages, but huge pages (2MB) can improve TLB behavior for large shared memory regions. While you may not use huge pages in these projects, you should understand that shared memory performance depends on the page cache and TLB just as much as it depends on raw CPU speed. Mapping large regions without touching them can trigger page faults later at unpredictable times; madvise and pre-faulting can reduce latency spikes.

mmap() introduces the concept of durability ordering. If you update two related records and call msync, you might still lose consistency if the OS writes them out in a different order. Databases solve this with write-ahead logs or copy-on-write schemes. Your memory-mapped database project should at least consider atomic updates and fail-safe layouts, even if it does not implement a full WAL.

Another subtlety is address independence. If you store pointers inside shared memory, they only make sense if all processes map the shared segment at the same address. The safer pattern is to store offsets relative to the base address and compute pointers dynamically. This pattern appears in many production shared-memory databases and is essential for portability.

Finally, shared memory must be cleaned. POSIX shared memory objects behave like files and can be unlinked even while in use. System V shared memory persists indefinitely. Both behaviors can surprise you: unlinked objects remain usable by existing mappings, and persistent objects can leak until you manually remove them. Effective development workflows include automated cleanup scripts.

Shared memory performance can be improved with prefaulting. If you know you will access every page in a region, touching each page at startup avoids page faults later. This is a common technique in low-latency systems. Linux also provides madvise and mlock to influence paging behavior; while not required for the projects, understanding their role helps explain why production shared-memory systems often include a warmup phase.

Durability is another subtlety. msync flushes memory to disk, but it does not guarantee ordering across multiple regions or files. If you update two related records, you may need an explicit ordering protocol (like write-ahead logging) to ensure crash consistency. This is the same fundamental problem solved by real databases.

Handling variable-sized records in shared memory is another advanced pattern. The safest approach is to store a fixed-size header (length, flags, checksum) followed by variable data. An offset table or free-list allocator then manages space. This is the same approach used in many embedded databases that rely on shared memory or memory mapping.

When a shared-memory segment is used by many processes, versioning becomes important. Adding a version field to the header lets new and old processes detect mismatches and refuse to run rather than corrupting data. This is a simple but effective practice for real systems.

You should also validate shared-memory correctness with checksums or sequence counters. Simple invariants like monotonic counters or message sequence IDs catch subtle ordering bugs that are otherwise hard to reproduce.

In shared-memory systems, adding a simple “magic number” and checksum to the header helps detect uninitialized or corrupted regions after crashes.

A simple end-to-end test is to run two processes, write sequential counters into shared memory, and verify monotonic reads on the other side. This catches most ordering and synchronization mistakes early.

How This Fits on Projects

Projects 12-15 are shared memory heavy. Projects 10-11 use shared memory for process-shared semaphores. Project 14 uses mmap() for persistence.

Definitions & Key Terms

- Shared memory: Memory region mapped into multiple processes.

- MAP_SHARED:

mmapflag that shares updates with other processes and the backing file. - False sharing: Performance loss when unrelated data shares a cache line.

- Memory ordering: The rules governing how CPUs reorder reads/writes.

Mental Model Diagram

Process A Kernel Process B

┌───────────────┐ ┌───────────┐ ┌───────────────┐

│ ptr -> [page] │ <--> │ page frame│ <------> │ ptr -> [page] │

└───────────────┘ └───────────┘ └───────────────┘

Both processes see the same physical memory; synchronization is up to you.

How It Works (Step-by-Step)

- Create or open shared memory (

shm_openorshmget). - Set size (POSIX requires

ftruncate). - Map it with

mmaporshmat. - Coordinate access with locks or atomics.

- Unmap and unlink/remove when done.

Invariants:

- All processes see the same bytes.

- The kernel does not provide synchronization.

Failure Modes:

- Data races cause corruption.

- Stale shared memory segments persist after crashes.

Minimal Concrete Example

int fd = shm_open("/demo", O_CREAT|O_RDWR, 0600);

ftruncate(fd, 4096);

int *counter = mmap(NULL, 4096, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_SHARED, fd, 0);

(*counter)++;

Common Misconceptions

- “Shared memory is safe without locks.” (False)

- “

mmap()automatically makes writes durable.” (False withoutmsync)

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- Why is shared memory faster than pipes or message queues?

- What happens if a process accesses beyond the mapped region?

- Why do lock-free structures require memory ordering?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- It avoids extra copies; processes read/write the same pages.

- The process receives SIGBUS; the mapping is invalid.

- CPUs can reorder operations; without fences, consumers may see stale data.

Real-World Applications

- Databases (shared buffer pools)

- High-frequency trading (ring buffers)

- Image or video pipelines

Where You Will Apply It

Projects 10-15.

References

shm_overview(7),shmget(2),mmap(2)(man7.org)- Stevens, UNP Vol 2 — Ch. 12-14

- The Linux Programming Interface — Ch. 48-54

Key Insight

Shared memory gives you speed but removes safety; correctness depends on the synchronization strategy you build on top.

Summary

You now understand how shared memory works, how mmap() enables persistence, and why synchronization is non-negotiable.

Homework / Exercises

- Write a shared-memory counter with a semaphore guard.

- Implement a shared-memory ring buffer and measure throughput vs pipes.

Solutions

- Use

sem_openwithsem_wait/sem_postaround the counter. - Use

clock_gettimeand compare message/sec for fixed message size.

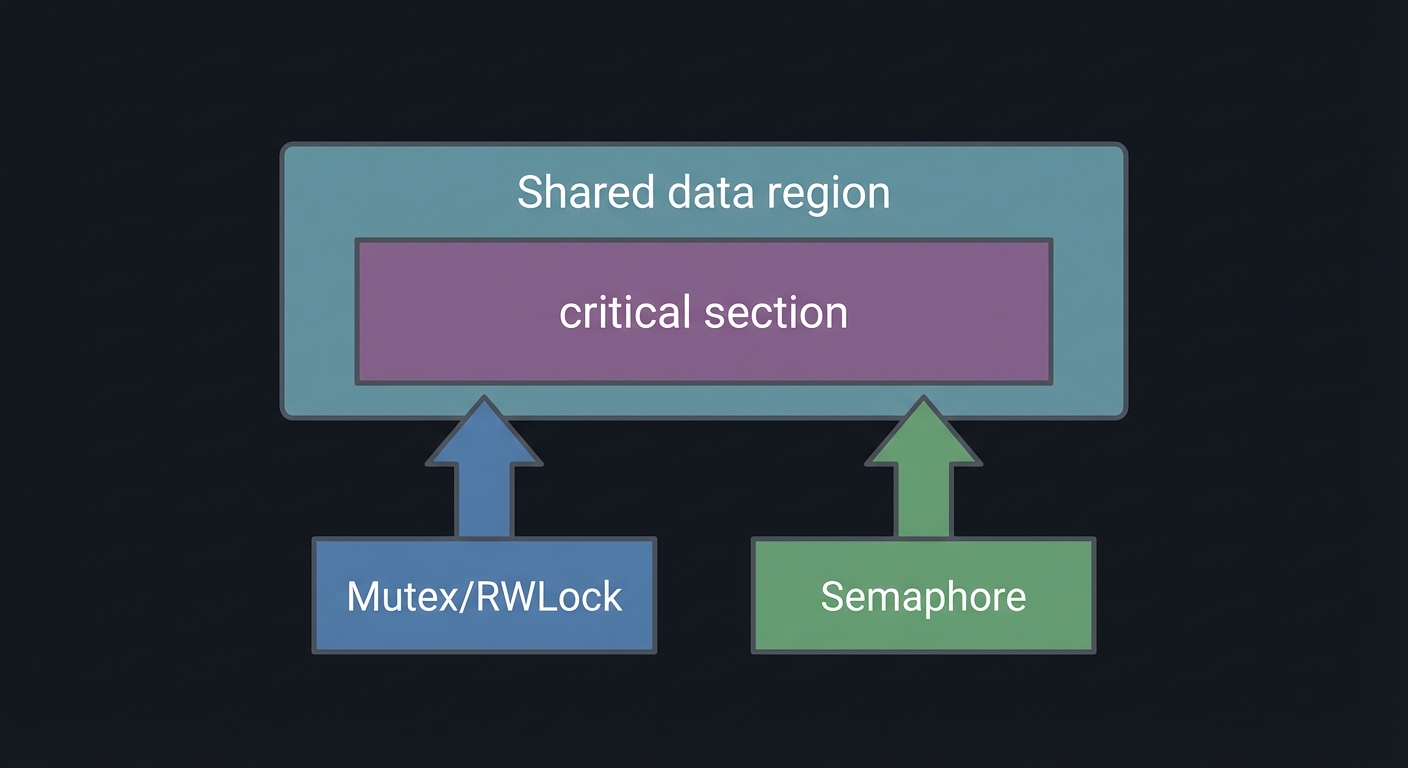

Chapter 5: Synchronization and Locking (Semaphores, Mutexes, RWLocks, Record Locks)

Fundamentals

Synchronization is the discipline of ensuring multiple processes or threads access shared resources safely. Without it, shared memory becomes a data corruption factory. Unix provides multiple synchronization mechanisms, each with different semantics. Semaphores are counters used to limit concurrency or signal events. Mutexes provide mutual exclusion. Condition variables let threads wait for specific states. Read-write locks allow multiple readers but only one writer. Record locks (fcntl) allow locking byte ranges in files and are used for coordination on disk-backed data structures.

These mechanisms solve different problems. Semaphores are ideal for resource pools, barriers, and producer-consumer queues. Mutexes and condition variables are best when shared memory structures need short critical sections and complex wait conditions. Read-write locks are optimized for read-heavy workloads. Record locking is essential when the shared state is a file (for example, in a memory-mapped database).

The critical insight is that synchronization defines the safety policy of your system. Data structures do not become safe by themselves. If you do not define which operations are atomic and how readers and writers interleave, your system will eventually fail under contention. Projects 7-11 drill these patterns deeply.

Synchronization also defines ownership. A mutex has a clear owner: the thread that locks it must unlock it. A semaphore does not require ownership, which makes it ideal for resource pools or signaling but dangerous if misused. This subtle difference explains why semaphores are sometimes misused as mutexes, leading to bugs that are hard to debug.

Condition variables are another subtle point. They do not represent a condition themselves; they are just a waiting room. The condition is represented by shared state, and every wait must check that state. This is why the canonical pattern is a while-loop around pthread_cond_wait. If you violate this pattern, your code will eventually fail under load.

Finally, record locks remind us that synchronization is not always about memory. Many systems coordinate through files because file-based state is naturally persistent. Record locks allow concurrency on disk-backed data without global locking. This is essential for file-based databases and large log files.

Another subtlety is the difference between Mesa and Hoare condition variable semantics. POSIX uses Mesa semantics: a signal is only a hint, and the condition must always be rechecked. This design favors performance but requires discipline in code.

Synchronization also balances latency vs CPU usage. Spinlocks or busy-wait loops can reduce latency but waste CPU; blocking primitives like semaphores and condition variables conserve CPU but add scheduling latency. Knowing this trade-off helps you choose between busy-waiting (for microsecond-scale latency) and blocking (for general-purpose workloads).

In practice, you often choose synchronization based on workload shape. If critical sections are tiny and frequent, mutexes or spinlocks may be ideal. If waits are long, condition variables or semaphores reduce CPU waste. This trade-off is part of performance engineering.

Semaphores are especially useful when you want to represent a counted resource (available slots, tickets, or permits) across multiple processes. This makes them the natural primitive for pools and rate limiting.

Deep Dive

Semaphores come in two families: POSIX and System V. POSIX semaphores (sem_open, sem_wait, sem_post) can be named or unnamed. Named semaphores appear under /dev/shm/sem.* on Linux and are reference-counted objects. System V semaphores are more complex: they exist as sets of semaphores and support atomic operations across multiple semaphores via semop. This allows advanced patterns like reusable barriers and resource allocation across multiple resources in one atomic step. System V semaphores also support SEM_UNDO, which can automatically adjust semaphore counts when a process exits unexpectedly, helping prevent leaks.

Mutexes and condition variables are part of pthreads but can be placed in shared memory and marked as process-shared. A mutex alone only provides mutual exclusion; a condition variable provides a way for threads or processes to sleep until a condition is true. Correct use requires a loop around pthread_cond_wait because spurious wakeups are allowed. This is a common interview question and a common source of subtle bugs.

Read-write locks extend mutexes by allowing multiple readers to enter concurrently. The trade-off is fairness: if readers continuously arrive, writers can starve unless the lock is designed to be writer-preferring. Implementing a read-write lock from first principles (Project 8) forces you to reason about state transitions, waiting queues, and fairness policies.

Record locking (fcntl) is conceptually different. Locks are attached to file regions, not to in-memory data. They are advisory, meaning only cooperating processes honor them. The granularity is flexible (byte ranges), which allows multiple processes to update different records in the same file concurrently. But it also introduces pitfalls: locks are per-process, and closing any file descriptor for that file releases all locks held by that process. This must be designed around in multi-threaded or multi-process systems.

Synchronization failure modes are serious: deadlocks (cyclic waits), livelocks (processes repeatedly retry without progress), priority inversion (low-priority thread holds a lock needed by a high-priority thread), and starvation (readers or writers never progress). Good design uses timeouts (sem_timedwait), consistent lock ordering, and diagnostics to detect stuck states. Projects 9-11 make these issues concrete.

A correct synchronization design begins with a state machine. For a bounded buffer, the states are “empty”, “partially full”, and “full”. For a read-write lock, the states include counts of active readers and whether a writer is waiting. Expressing the synchronization policy as explicit state transitions helps you reason about deadlocks and fairness. This is why many high-quality synchronization implementations start with a diagram or truth table rather than code.

Process-shared mutexes and condition variables introduce additional complexity. You must initialize them with attributes that mark them as process-shared, and the underlying memory must be in a shared region. If you forget the attribute, the locks will work inside a single process but fail silently across processes. This is a classic bug that appears when developers move from threads to multi-process designs.

System V semaphores are more complex but also more expressive. Because semop can update multiple semaphores atomically, you can implement barriers, multi-resource allocation, or phase transitions without intermediate race windows. The trade-off is a more complex API and more ways to get it wrong. The value of Projects 10 and 11 is that they force you to use these features intentionally.

Record locking deserves deeper attention. POSIX fcntl locks are per-process; they are not per-thread. In a multithreaded process, one thread can unintentionally release another thread’s locks by closing a file descriptor. Modern Linux provides open-file-description locks (F_OFD_SETLK) that are per-file-description rather than per-process, but those are non-POSIX. For portability, you must design around the POSIX semantics.

Deadlocks deserve explicit analysis. The four necessary conditions for deadlock are mutual exclusion, hold-and-wait, no preemption, and circular wait. You can prevent deadlocks by breaking at least one of these conditions: enforce a global lock ordering (break circular wait), use try-lock and backoff (break hold-and-wait), or redesign with lock-free queues. Understanding this theory is not academic; it directly informs how you design IPC systems that cannot afford to hang.

Priority inversion is another real-world failure mode. A low-priority process may hold a lock needed by a high-priority process, causing the high-priority process to wait indefinitely. Some systems use priority inheritance mutexes to mitigate this. Even if you do not implement priority inheritance, you should recognize the problem and know when it can occur.

Robust mutexes are worth understanding as well. Linux supports PTHREAD_MUTEX_ROBUST, which allows a process to detect when a previous owner died while holding the lock. This is a powerful tool for crash recovery in shared-memory systems, though it adds complexity to lock management.

Deadlock avoidance is often implemented by global lock ordering. For example, if you always lock semaphores in increasing numeric order, you prevent cycles. This principle applies equally to record locks and mutexes. Even in small projects, choosing and documenting a lock order prevents entire classes of bugs.

SEM_UNDO is not free. The kernel must track per-process adjustments and apply them on exit. This adds overhead and does not handle all crash scenarios (e.g., kernel crash). Use it for safety during development, but understand its cost in high-performance systems.

Reader-writer locks introduce another subtlety: upgrade/downgrade. Many systems disallow upgrading from read to write without releasing the lock, because it can deadlock. If you ever need upgrades, you must design explicit protocols for it.

When testing synchronization, always include stress tests with randomized sleeps. This increases interleavings and exposes hidden races that do not appear in deterministic runs.

Finally, remember that synchronization is only as good as its testing. Stress tests, fault injection, and lock contention benchmarks are part of the engineering discipline, not optional extras.

When evaluating synchronization, always measure both correctness and fairness; a lock that is “correct” but starves writers can be unacceptable in real systems.

How This Fits on Projects

Projects 7-11 use synchronization heavily, and Projects 12-15 depend on it for shared memory correctness. Project 14 uses record locks to guard on-disk structures.

Definitions & Key Terms

- Semaphore: Integer counter controlling access to a limited resource.

- Mutex: Mutual exclusion lock for critical sections.

- Condition variable: Wait/notify primitive for state changes.

- Read-write lock: Allows many readers or one writer.

- Advisory lock: Lock honored only by cooperating processes.

Mental Model Diagram

Shared data region

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│ critical section │

└─────────────────────────────┘

^ ^

| |

Mutex/RWLock Semaphore

How It Works (Step-by-Step)

- Create synchronization primitives (sem_open, pthread_mutex_init, etc.).

- Associate them with the shared resource.

- Acquire before entering a critical section.

- Release after updating shared state.

- Detect and resolve deadlocks or leaks.

Invariants:

- A resource must be protected by exactly one synchronization policy.

- All code paths must follow the same lock order.

Failure Modes:

- Deadlocks, starvation, and leaked semaphores.

Minimal Concrete Example

sem_t *sem = sem_open("/pool", O_CREAT, 0600, 5);

sem_wait(sem); // acquire

// use shared resource

sem_post(sem); // release

Common Misconceptions

- “Semaphore == mutex.” (Not always; semaphores are counting)

- “Condition variables wake exactly one waiter.” (Not guaranteed; spurious wakeups exist)

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- Why do read-write locks risk writer starvation?

- What does

SEM_UNDOchange about process crashes? - Why are

fcntllocks called advisory?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- Readers can keep acquiring the lock, preventing writers from ever acquiring it.

- The kernel can adjust semaphore values when a process exits, reducing leaks.

- The kernel does not enforce them; only cooperative programs honor them.

Real-World Applications

- Database connection pools

- File-based key-value stores

- Multi-process servers

Where You Will Apply It

Projects 7-11 and 14.

References

sem_overview(7),semop(2),fcntl(2)(man7.org)- Stevens, UNP Vol 2 — Ch. 7-11

- The Linux Programming Interface — Ch. 46-48, 53

Key Insight

Synchronization is not a feature you add later; it is the core safety contract of your IPC design.

Summary

You now understand the major synchronization primitives and their failure modes.

Homework / Exercises

- Implement a barrier using POSIX semaphores.

- Build a file-based counter with

fcntllocks and test with multiple processes.

Solutions

- Use two semaphores: one for arrival count and one for release.

- Lock the byte range for the record before reading/writing, then unlock.

Chapter 6: RPC and XDR (IPC Across Machines)

Fundamentals

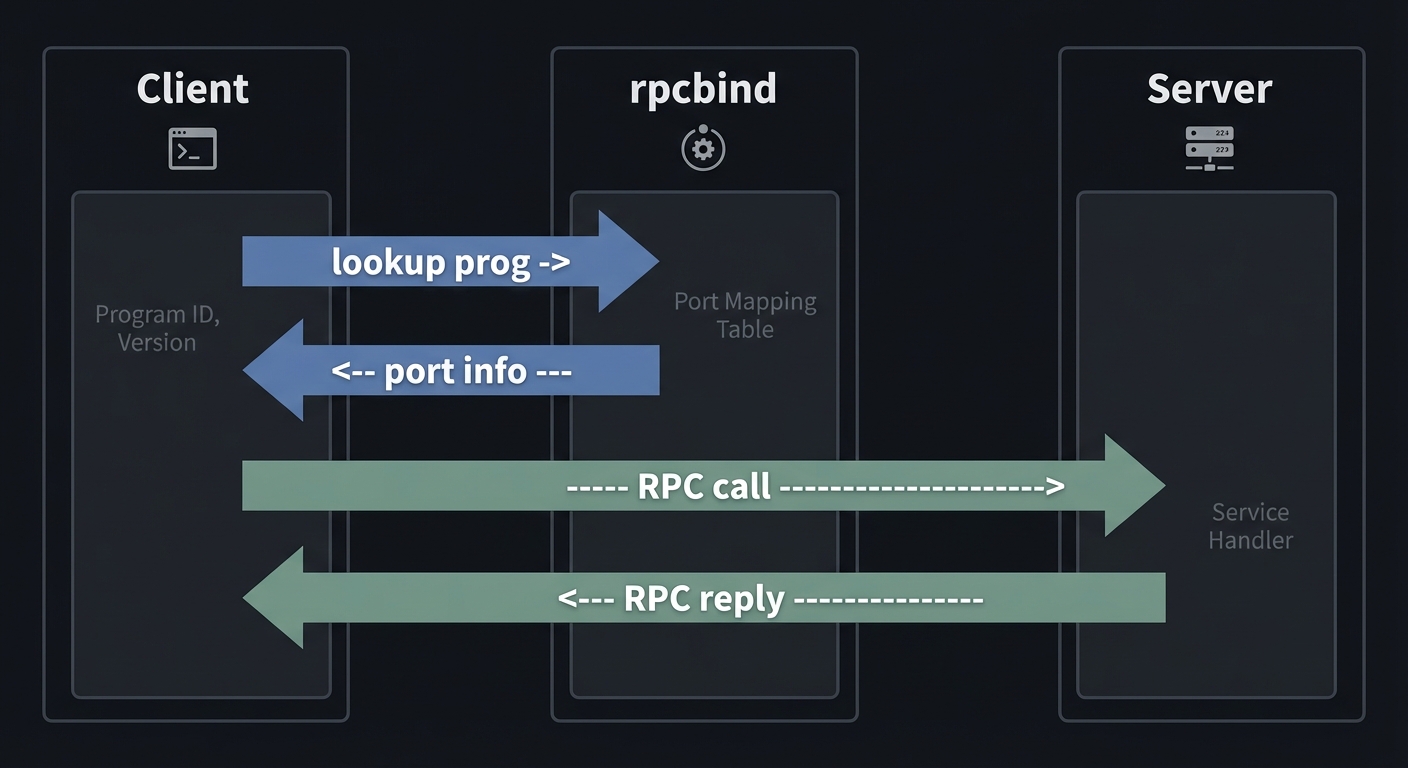

Remote Procedure Call (RPC) extends IPC beyond a single machine. Instead of writing explicit socket code, you define an interface and call functions as if they were local, while a stub handles serialization, network transport, and error handling. Sun/ONC RPC is the classic Unix RPC system, defined in RFC 5531. It uses XDR (External Data Representation) for portable serialization, defined in RFC 4506.

RPC introduces new complexity: partial failure, network latency, retries, and authentication. You must decide whether calls are idempotent, how to handle timeouts, and how to recover from dropped connections. The RPC model is a huge conceptual leap from local IPC because the network can fail in ways local IPC usually does not.

RPC forces you to think about partial failure. A local IPC call either succeeds or fails in a predictable way. An RPC call can fail because the network is down, because the server is overloaded, or because the response was lost. This uncertainty is why RPC clients must implement timeouts, retries, and idempotency. These are not optional features; they are the core of distributed programming.

RPC also forces you to think about compatibility. Once you define an RPC interface and deploy it, clients and servers may run different versions for long periods. This requires explicit versioning, backwards compatibility, and careful data type evolution. You will practice this in the later projects.

Finally, RPC raises the issue of trust boundaries. Local IPC often assumes trusted participants, but RPC may cross security boundaries. Authentication and authorization become first-class concerns, and the naive AUTH_SYS model quickly shows its limitations.

RPC systems are also about concurrency models. You can design a single-threaded server that handles one request at a time (simple but slow), or a multi-threaded server that dispatches requests concurrently (fast but more complex). Many real systems combine both approaches: a limited thread pool to cap resource use while still allowing parallelism.

RPC APIs also expose error models. You must decide how to map transport failures, timeouts, and server-side errors into return codes or exceptions. Designing these error contracts is as important as designing the data schema, because it determines how clients recover and how debugging works in production.

Service discovery is also core to RPC. The client does not hard-code a port; it asks rpcbind, which allows services to move without breaking clients. This is a direct ancestor of modern service discovery systems.

RPC also changes your testing discipline. You must test not only correctness but also timeouts, retries, and partial failures. A good RPC test suite always includes network fault injection.

Another practical point: RPC debugging often requires network visibility. Capturing traffic with tcpdump or wireshark lets you see whether requests are sent, how long replies take, and whether retransmissions occur. This visibility is essential when building real services.

RPC also affects deployment. Servers must register on startup and clients must tolerate restarts. Even on localhost, you should design for reconnects and transient failures to match real-world behavior.

Deep Dive