Project 5: System V Message Queue Multi-Client Server

Create a multi-client server using System V message queues.

Quick Reference

| Attribute | Value |

|---|---|

| Difficulty | Level 3 (Advanced) |

| Time Estimate | 1 Week |

| Main Programming Language | C (Alternatives: ) |

| Alternative Programming Languages | N/A |

| Coolness Level | Level 3 (Genuinely Clever) |

| Business Potential | Level 2 (Micro-SaaS) |

| Prerequisites | C programming, basic IPC familiarity, Linux tools (strace/ipcs) |

| Key Topics | System V MQ, mtype routing, keys, cleanup |

1. Learning Objectives

By completing this project, you will:

- Build a working IPC-based system aligned with Stevens Vol. 2 concepts.

- Implement robust lifecycle management for IPC objects.

- Handle errors and edge cases deterministically.

- Document and justify design trade-offs.

- Benchmark or validate correctness under load.

2. All Theory Needed (Per-Concept Breakdown)

System V Message Queues (msgget/msgsnd/msgrcv)

Fundamentals

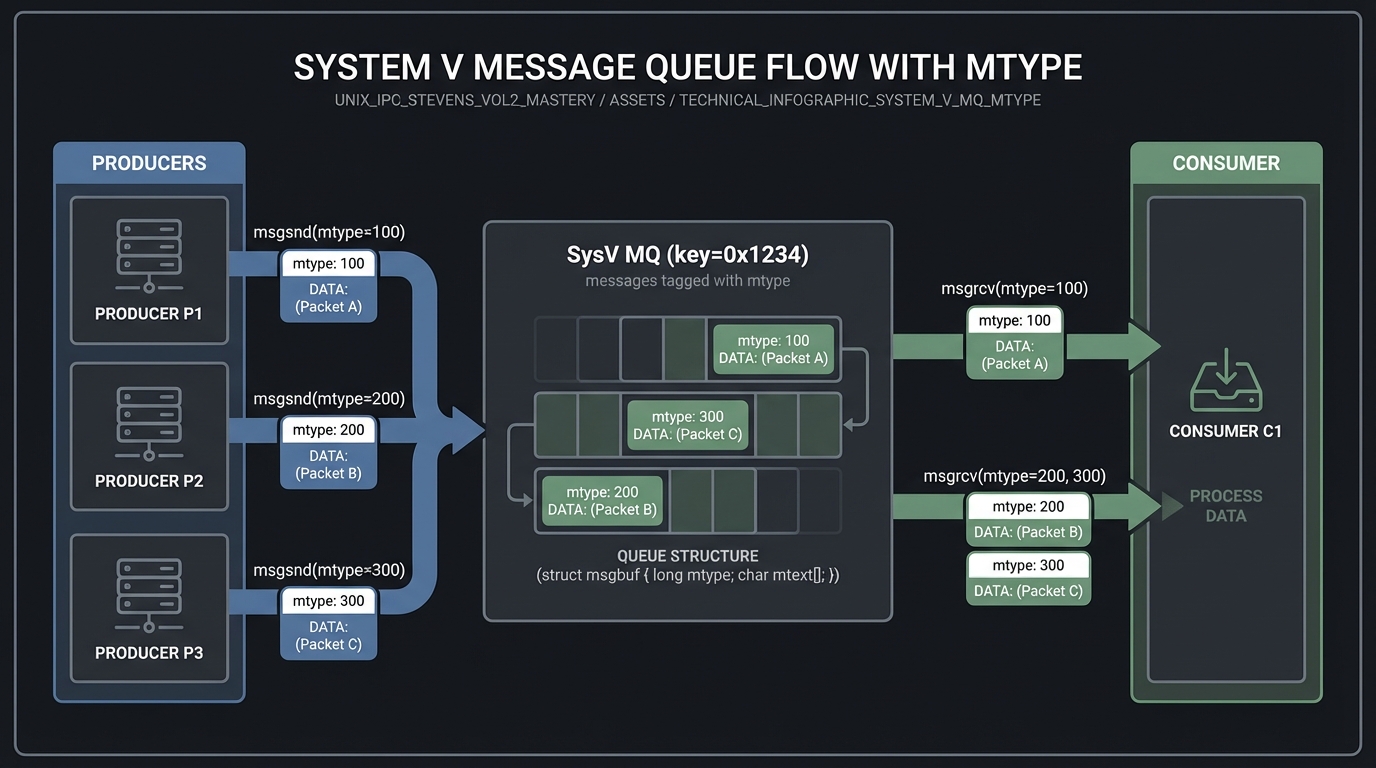

System V message queues are older IPC primitives that use numeric keys and kernel persistence. A queue is created with msgget(key, flags), and messages are sent and received via msgsnd and msgrcv. Each message has a type (mtype) that can be used for selective receive, enabling simple routing patterns without multiple queues. System V queues persist in the kernel until explicitly removed with msgctl(IPC_RMID).

Compared to POSIX MQs, System V queues are lower-level and less ergonomic, but still heavily used in legacy systems and in environments where POSIX MQs are not available. Their persistence and key-based naming require careful lifecycle management.

Deep Dive into the Concept

System V IPC introduces a global key namespace. You can generate keys with ftok(), which hashes a filename and project id, but collisions are possible. Many production systems use fixed numeric keys and dedicated directories to avoid collisions. When you create a queue, you choose whether to create or attach to an existing one. The usual pattern is msgget(key, IPC_CREAT | IPC_EXCL) to ensure you created it, and if it exists, either reuse it or delete and recreate it.

Messages in System V queues consist of a long mtype and an arbitrary byte payload. msgrcv allows you to receive the first message of a given type (or the lowest type greater than a value). This makes it easy to implement multiple logical channels within a single queue. However, message boundaries are not self-describing, so you must define your own protocol for message structs and sizes. Also note that System V queues have per-queue and system-wide limits (msgmnb, msgmax) that can be inspected with ipcs -l.

The persistence model is powerful but dangerous: if a server crashes without removing the queue, it remains and clients may continue to send messages into the void. A robust design includes explicit cleanup on startup: detect and remove stale queues, or attach and drain them. This persistence is the biggest behavioral difference from POSIX MQs and should be a conscious design choice.

How this fits on projects

System V MQs are at the core of the multi-client server project and are compared directly against POSIX MQs in the benchmark project.

Definitions & key terms

- key_t -> Numeric key for System V IPC objects.

- mtype -> Message type used for selective receive.

- IPC_RMID -> Control command to remove a queue.

Mental model diagram (ASCII)

Producers -> [ SysV MQ (key=0x1234) ] -> Consumer

(messages tagged with mtype)

How it works (step-by-step, with invariants and failure modes)

- Server calls

msggetwith key andIPC_CREAT. - Clients call

msggetwith same key to attach. - Clients send messages with mtype.

- Server receives based on mtype, processes, replies.

- Server removes queue with

msgctl(IPC_RMID)on shutdown.

Failure modes: key collision, stale queues after crash, exceeding msg limits.

Minimal concrete example

int q = msgget(0x1234, IPC_CREAT | 0600);

struct msg { long mtype; char text[32]; } m = {1, "hi"};

msgsnd(q, &m, sizeof(m.text), 0);

msgrcv(q, &m, sizeof(m.text), 1, 0);

**Common misconceptions**

- "System V MQs are obsolete." -> Many systems still use them; they are part of POSIX.

- "`ftok()` is safe." -> It can collide; use fixed keys or dedicated paths.

- "Queues auto-clean." -> They persist until removed explicitly.

**Check-your-understanding questions**

1. What happens if two programs choose the same key?

2. How does `mtype` influence message selection?

3. Why is persistence both a feature and a risk?

**Check-your-understanding answers**

1. They attach to the same queue, possibly causing interference.

2. `msgrcv` can filter by type, enabling routing.

3. It survives crashes but can leave stale queues.

**Real-world applications**

- Legacy financial systems.

- System management daemons on Unix variants.

**Where you’ll apply it**

- In this project: §3.2 Functional Requirements, §7 Common Pitfalls.

- Also used in: [P06-mq-benchmark.md](P06-mq-benchmark.md).

**References**

- Stevens, "UNP Vol 2" Ch. 6.

- `man 7 sysvipc`, `man 2 msgget`.

**Key insights**

- System V MQs are powerful but demand explicit lifecycle management.

**Summary**

System V message queues are persistent, typed message buffers. They are ideal for multi-client servers but require careful key and cleanup discipline.

**Homework/Exercises to practice the concept**

1. Create a queue, crash the server, and observe it with `ipcs`.

2. Implement two mtypes and selective receives.

3. Simulate key collisions and handle them.

**Solutions to the homework/exercises**

1. Use `ipcs -q` and `ipcrm -q` to observe and clean.

2. Send messages with mtype 1 and 2 and receive them separately.

3. Use `IPC_EXCL` and fall back to a different key.

---

## 3. Project Specification

### 3.1 What You Will Build

Create a multi-client server using System V message queues.

### 3.2 Functional Requirements

1. **Requirement 1**: Server creates queue with fixed key

2. **Requirement 2**: Clients send requests with mtype=1

3. **Requirement 3**: Server replies using client-specific mtype

### 3.3 Non-Functional Requirements

- **Performance**: Must handle at least 10,000 messages/operations without failure.

- **Reliability**: IPC objects are cleaned up on shutdown or crash detection.

- **Usability**: CLI output is readable with clear error codes.

### 3.4 Example Usage / Output

```text

./sysv_server &

./sysv_client --id 42 --msg hello

### 3.5 Data Formats / Schemas / Protocols

Message struct: {long mtype; int client_id; char body[256];}.

### 3.6 Edge Cases

- Key collision

- Stale queue on restart

- Oversized messages

### 3.7 Real World Outcome

You will have a working IPC subsystem that can be run, traced, and tested in a reproducible way.

#### 3.7.1 How to Run (Copy/Paste)

```bash

make

./run_demo.sh

#### 3.7.2 Golden Path Demo (Deterministic)

```bash

./run_demo.sh --mode=golden

Expected output includes deterministic counts and a final success line:

```text

OK: golden scenario completed

#### 3.7.3 Failure Demo (Deterministic)

```bash

./run_demo.sh --mode=failure

Expected output:

```text

ERROR: invalid input or unavailable IPC resource

exit=2

---

## 4. Solution Architecture

### 4.1 High-Level Design

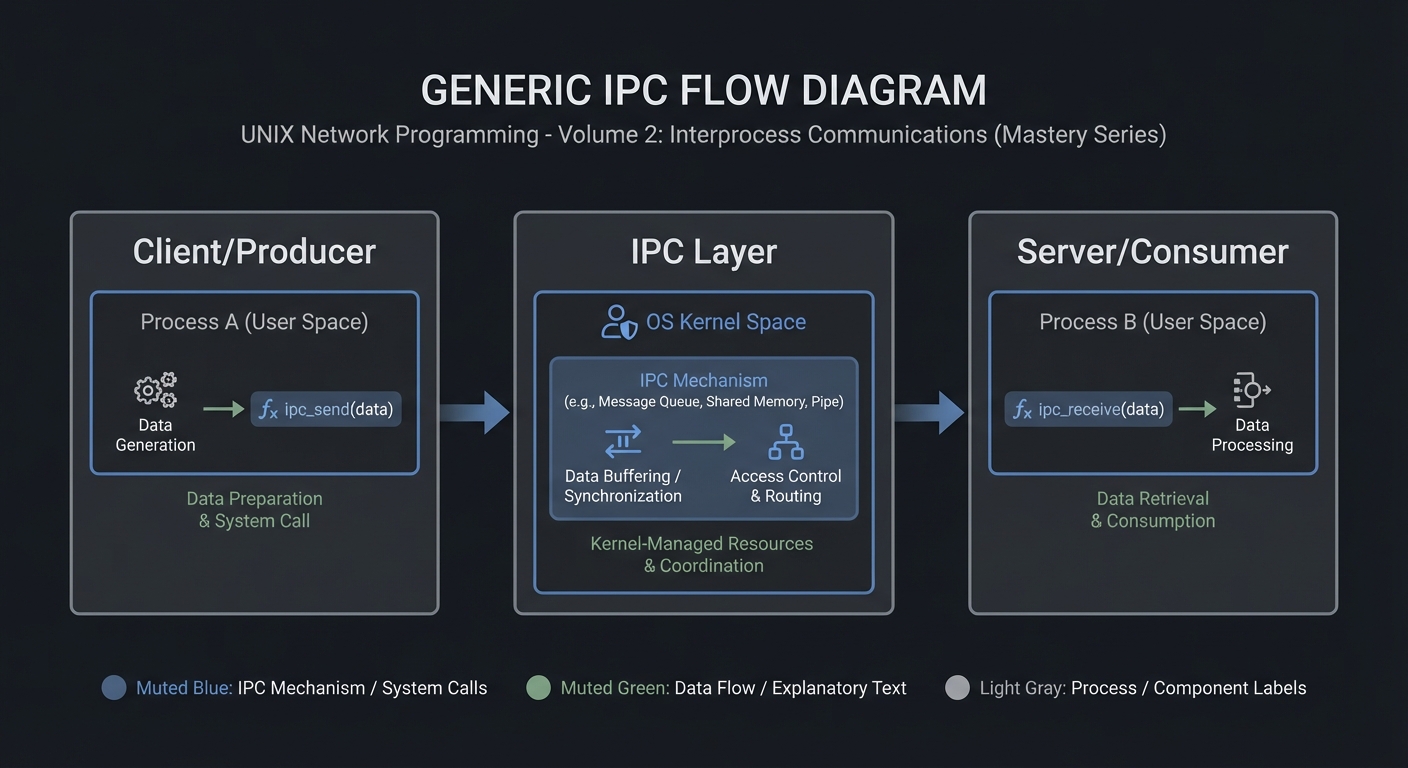

Client/Producer -> IPC Layer -> Server/Consumer

4.2 Key Components

| Component | Responsibility | Key Decisions |

|---|---|---|

| IPC Setup | Create/open IPC objects | POSIX vs System V choices |

| Worker Loop | Send/receive messages | Blocking vs non-blocking |

| Cleanup | Unlink/remove IPC objects | Crash safety |

4.3 Data Structures (No Full Code)

struct message {

int id;

int len;

char payload[256];

};

### 4.4 Algorithm Overview

**Key Algorithm: IPC Request/Response**

1. Initialize IPC resources.

2. Client sends request.

3. Server processes and responds.

4. Cleanup on exit.

**Complexity Analysis:**

- Time: O(n) in number of messages.

- Space: O(1) per message plus IPC buffer.

---

## 5. Implementation Guide

### 5.1 Development Environment Setup

```bash

sudo apt-get install build-essential

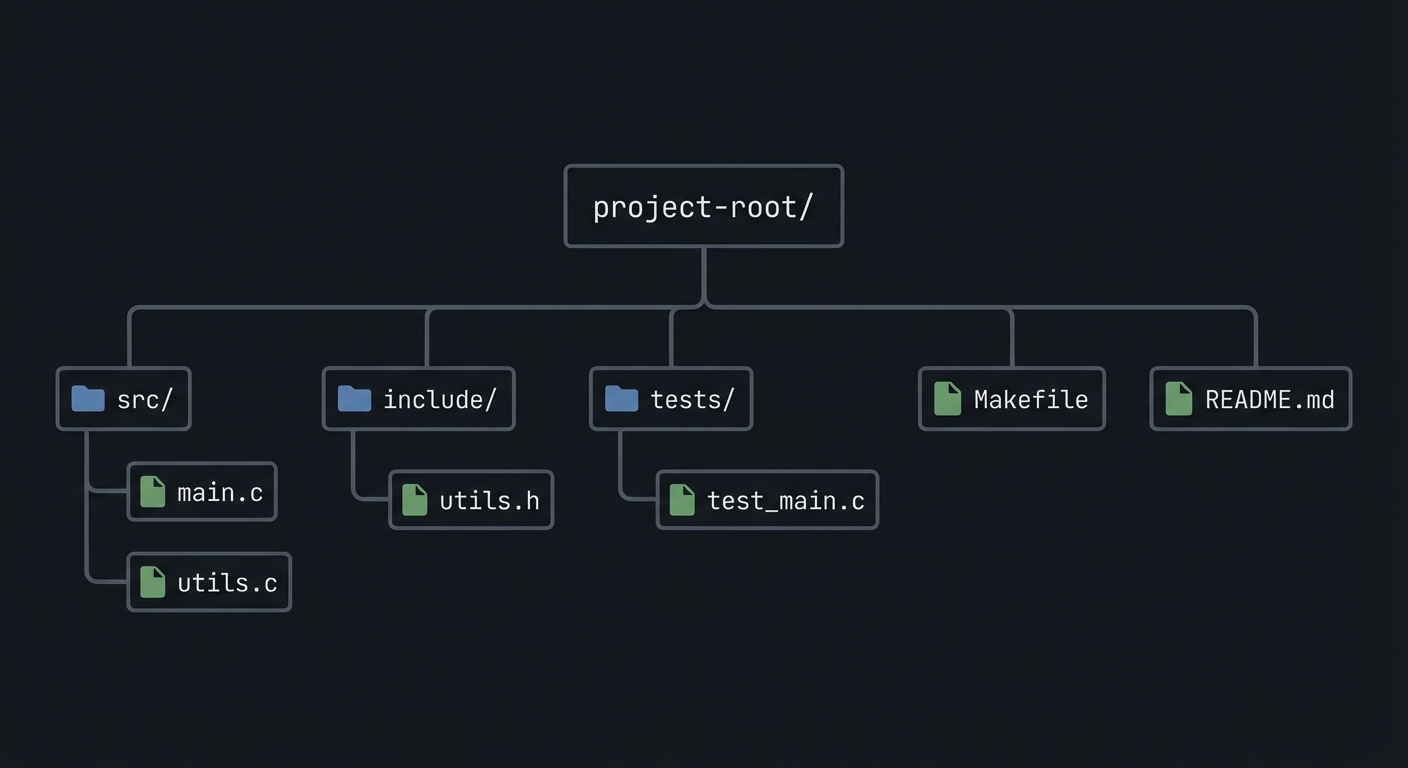

### 5.2 Project Structure

project-root/

├── src/

├── include/

├── tests/

├── Makefile

└── README.md

5.3 The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do you build a request/response service with typed messages?”

5.4 Concepts You Must Understand First

- IPC object lifecycle (create/open/unlink)

- Blocking vs non-blocking operations

- Error handling with errno

5.5 Questions to Guide Your Design

- What invariants guarantee correctness in this IPC flow?

- How will you prevent resource leaks across crashes?

- How will you make the system observable for debugging?

5.6 Thinking Exercise

Before coding, sketch the IPC lifecycle and identify where deadlock could occur.

5.7 The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- Why choose this IPC mechanism over alternatives?

- What are the lifecycle pitfalls?

- How do you test IPC code reliably?

5.8 Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with a single producer and consumer.

Hint 2: Add logging around every IPC call.

Hint 3: Use strace or ipcs to verify resources.

5.9 Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| IPC fundamentals | Stevens, UNP Vol 2 | Relevant chapters |

| System calls | APUE | Ch. 15 |

5.10 Implementation Phases

Phase 1: Foundation (2-4 hours)

Goals:

- Create IPC objects.

- Implement a minimal send/receive loop.

Tasks:

- Initialize IPC resources.

- Implement basic client and server.

Checkpoint: Single request/response works.

Phase 2: Core Functionality (4-8 hours)

Goals:

- Add error handling and cleanup.

- Support multiple clients or concurrent operations.

Tasks:

- Add structured message format.

- Implement cleanup on shutdown.

Checkpoint: System runs under load without leaks.

Phase 3: Polish & Edge Cases (2-4 hours)

Goals:

- Add deterministic tests.

- Document behaviors.

Tasks:

- Add golden and failure scenarios.

- Document limitations.

Checkpoint: Tests pass, behavior documented.

5.11 Key Implementation Decisions

| Decision | Options | Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blocking mode | blocking vs non-blocking | blocking | Simpler for first version |

| Cleanup | manual vs automated | explicit cleanup | Avoid stale IPC objects |

6. Testing Strategy

6.1 Test Categories

| Category | Purpose | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Unit Tests | Validate helpers | message encode/decode |

| Integration Tests | IPC flow | client-server round trip |

| Edge Case Tests | Failure modes | missing queue, full buffer |

6.2 Critical Test Cases

- Single client request/response works.

- Multiple requests do not corrupt state.

- Failure case returns exit code 2.

6.3 Test Data

Input: “hello” Expected: “hello”

7. Common Pitfalls & Debugging

7.1 Frequent Mistakes

| Pitfall | Symptom | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Not cleaning IPC objects | Next run fails | Add cleanup on exit |

| Blocking forever | Program hangs | Add timeouts or non-blocking mode |

| Incorrect message framing | Corrupted data | Add length prefix and validate |

7.2 Debugging Strategies

- Use

strace -fto see IPC syscalls. - Use

ipcsor/dev/mqueueto inspect objects.

7.3 Performance Traps

- Small queue sizes cause frequent blocking.

8. Extensions & Challenges

8.1 Beginner Extensions

- Add verbose logging.

- Add a CLI flag to toggle non-blocking mode.

8.2 Intermediate Extensions

- Add request timeouts.

- Add a metrics report.

8.3 Advanced Extensions

- Implement load testing with multiple clients.

- Add crash recovery logic.

9. Real-World Connections

9.1 Industry Applications

- IPC services in local daemons.

- Message-based coordination in legacy systems.

9.2 Related Open Source Projects

- nfs-utils - Uses RPC and IPC extensively.

- systemd - Uses multiple IPC mechanisms.

9.3 Interview Relevance

- Demonstrates system call knowledge and concurrency reasoning.

10. Resources

10.1 Essential Reading

- Stevens, “UNP Vol 2”.

- Kerrisk, “The Linux Programming Interface”.

10.2 Video Resources

- Unix IPC lectures from OS courses.

10.3 Tools & Documentation

man 7 ipc,man 2for each syscall.

10.4 Related Projects in This Series

11. Self-Assessment Checklist

11.1 Understanding

- I can describe IPC object lifecycle.

- I can explain blocking vs non-blocking behavior.

- I can reason about failure modes.

11.2 Implementation

- All functional requirements are met.

- Tests pass.

- IPC objects are cleaned up.

11.3 Growth

- I can explain design trade-offs.

- I can explain this project in an interview.

12. Submission / Completion Criteria

Minimum Viable Completion:

- Basic IPC flow works with correct cleanup.

- Error handling returns deterministic exit codes.

Full Completion:

- Includes tests and deterministic demos.

- Documents trade-offs and limitations.

Excellence (Going Above & Beyond):

- Adds performance benchmarking and crash recovery.