Project 2: Client-Server with Named Pipes (FIFOs)

Build a FIFO-based client-server where unrelated processes send requests and receive responses.

Quick Reference

| Attribute | Value |

|---|---|

| Difficulty | Level 2 (Intermediate) |

| Time Estimate | Weekend |

| Main Programming Language | C (Alternatives: Rust, Python) |

| Alternative Programming Languages | Rust, Python |

| Coolness Level | Level 3 (Genuinely Clever) |

| Business Potential | Level 2 (Micro-SaaS potential) |

| Prerequisites | C programming, basic IPC familiarity, Linux tools (strace/ipcs) |

| Key Topics | FIFOs, open semantics, message framing, permissions |

1. Learning Objectives

By completing this project, you will:

- Build a working IPC-based system aligned with Stevens Vol. 2 concepts.

- Implement robust lifecycle management for IPC objects.

- Handle errors and edge cases deterministically.

- Document and justify design trade-offs.

- Benchmark or validate correctness under load.

2. All Theory Needed (Per-Concept Breakdown)

Named Pipes (FIFOs) and Open Semantics

Fundamentals

A FIFO (named pipe) is a special file on disk that represents a unidirectional byte stream between unrelated processes. Unlike anonymous pipes, a FIFO has a pathname and can be opened by any process with permissions. The semantics are close to pipes: read() blocks until data is available, write() blocks when the buffer is full, and EOF arrives when all writers close. The key conceptual shift is that the FIFO exists in the filesystem, which allows processes without a parent-child relationship to coordinate. This is exactly why FIFOs were invented: they extend the pipe model to arbitrary processes.

Opening a FIFO has special semantics. Opening for read blocks until a writer opens the FIFO; opening for write blocks until a reader opens it. This creates a potential deadlock if both sides open in the wrong order. Many production systems avoid this by opening the FIFO in non-blocking mode or by opening both read and write ends in the same process to break the block. Understanding these open semantics is critical; most FIFO bugs are not about reading or writing but about how processes start and connect.

Because FIFOs appear in the filesystem, they inherit file permissions. A FIFO with mode 0600 can only be read by its owner. This makes FIFOs a simple but effective IPC mechanism for local security boundaries: you can restrict which users can connect by controlling the FIFO path and permissions.

Deep Dive into the Concept

Under the hood, FIFOs are managed by the same kernel pipe code, but the existence of a pathname introduces lifecycle and coordination questions. A FIFO must be created with mkfifo() (or mknod), and you must decide who owns its lifecycle. Should the server create it at startup and unlink it at shutdown? Should it persist across restarts? These decisions determine how robust the system is when processes crash. If a server crashes without unlinking, the FIFO remains, which can be good (clients can reconnect) or bad (clients connect to a stale file with no server).

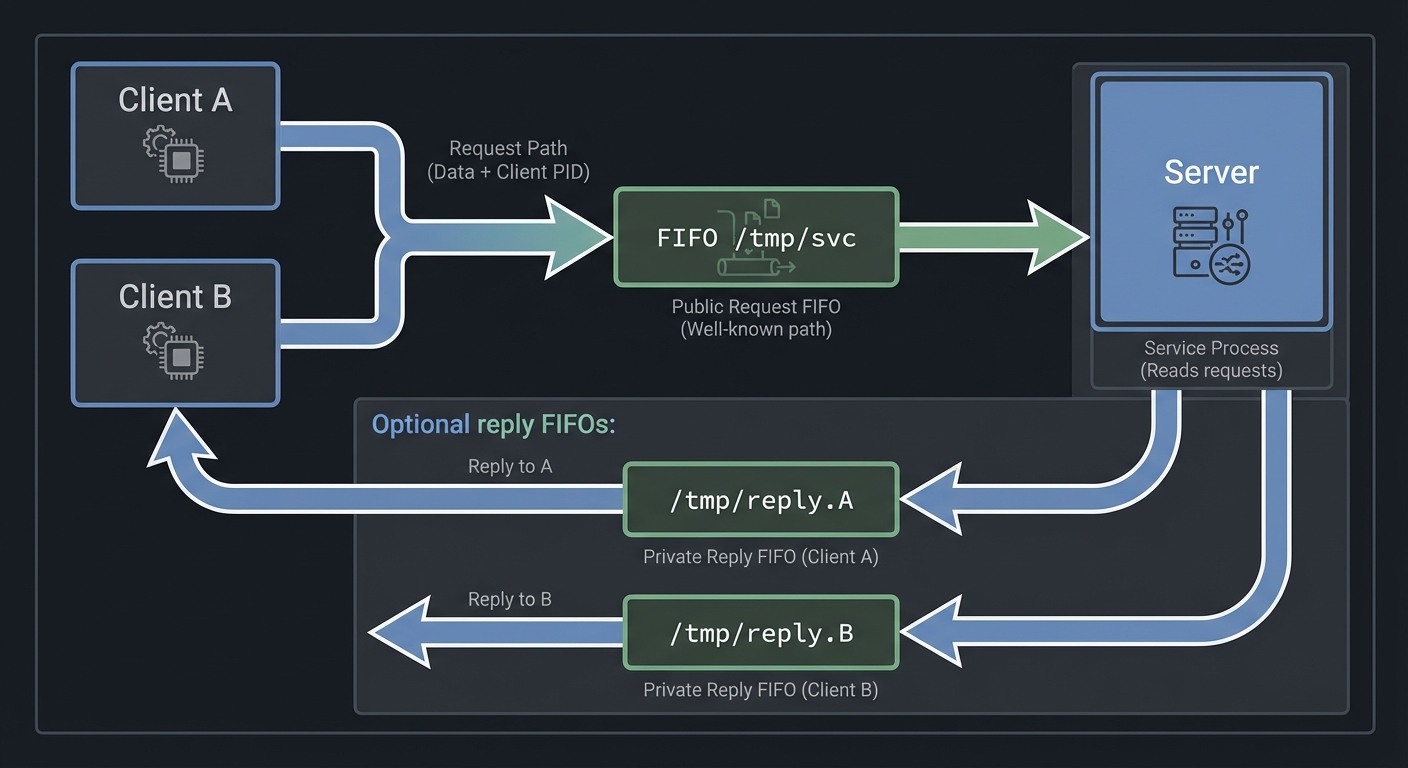

The open semantics are subtle: opening for reading blocks until a writer opens the FIFO, and opening for writing blocks until a reader opens it, unless O_NONBLOCK is used. This behavior provides a handshake but also creates race conditions. A robust FIFO client-server uses a connection protocol: the server creates the FIFO and opens it for reading and writing to avoid blocking; clients open for writing, send requests, and optionally open a response FIFO for replies. If you need multiple clients, you must design a message framing protocol, because FIFOs are byte streams without message boundaries. The simplest protocol is line-based or length-prefixed messages. Without framing, messages from multiple writers can interleave unless you respect PIPE_BUF limits.

FIFOs also expose the trade-off between simplicity and scalability. They are easy to implement for one server and a handful of clients, but they lack built-in message semantics, priorities, or persistence. You must implement your own concurrency control. For example, if multiple clients write to the same FIFO, the server must parse the stream and reassemble complete messages, often with a delimiter or length prefix. If you need reply channels, you often create per-client FIFOs. This is a classic pattern in Unix daemons and a gentle introduction to request/response IPC without sockets.

How this fits on projects

This concept is central to FIFO client-server systems and influences any IPC design where unrelated processes must connect without a pre-existing parent-child relationship.

Definitions & key terms

- FIFO -> Named pipe stored in the filesystem.

- Open semantics -> Blocking behavior on open for read/write.

- Message framing -> Protocol for delineating messages in a byte stream.

- PIPE_BUF -> Atomic write limit that prevents interleaving.

Mental model diagram (ASCII)

Client A --- > [FIFO /tmp/svc] --> Server

Client B ---/

Optional reply FIFOs:

Client A <-- [/tmp/reply.A]

Client B <-- [/tmp/reply.B]

How it works (step-by-step, with invariants and failure modes)

- Server creates FIFO with

mkfifoand sets permissions. - Server opens FIFO for read (and optionally write) to avoid open deadlock.

- Client opens FIFO for write, sends framed request.

- Server reads a complete message, processes, replies via per-client FIFO or shared response channel.

- Client closes FIFO; server detects EOF when all writers close.

Failure modes: open deadlock, interleaved messages without framing, dangling FIFO after crash.

Minimal concrete example

mkfifo("/tmp/svc", 0600);

int fd = open("/tmp/svc", O_RDONLY);

char buf[256];

ssize_t n = read(fd, buf, sizeof(buf));

**Common misconceptions**

- "A FIFO is bidirectional." -> It is unidirectional; use two FIFOs for request/response.

- "Open never blocks." -> It blocks unless you use `O_NONBLOCK`.

- "Messages are preserved." -> It is a byte stream; you must frame messages.

**Check-your-understanding questions**

1. Why can opening a FIFO for reading block forever?

2. How do multiple writers avoid interleaving messages?

3. What happens if the server crashes and the FIFO remains?

**Check-your-understanding answers**

1. It blocks until at least one writer opens the FIFO.

2. Keep messages <= PIPE_BUF and use framing.

3. Clients can still open the FIFO, but no process reads; writes may block or get SIGPIPE if no readers.

**Real-world applications**

- Local daemon request queues.

- Simple log ingestion or command channels.

**Where you’ll apply it**

- In this project: §3.2 Functional Requirements, §5.10 Phase 2.

- Also used in: [P01-shell-pipeline.md](P01-shell-pipeline.md).

**References**

- `man 7 fifo`, `man 3 mkfifo`.

- APUE Ch. 15 (Pipes and FIFOs).

**Key insights**

- FIFOs are pipes with names; the extra power is in the open semantics and filesystem lifecycle.

**Summary**

FIFOs turn the pipe model into a filesystem-addressable IPC channel. Mastering their open semantics is the difference between a working server and a deadlock.

**Homework/Exercises to practice the concept**

1. Build a FIFO echo server and two clients.

2. Demonstrate open deadlock and fix it with `O_NONBLOCK`.

3. Implement length-prefixed framing over a FIFO.

**Solutions to the homework/exercises**

1. Server reads lines, clients write lines, and server replies via per-client FIFO.

2. Open FIFO with `O_RDONLY | O_NONBLOCK` and retry.

3. Prefix each message with a 4-byte length and read exactly that many bytes.

---

## 3. Project Specification

### 3.1 What You Will Build

Build a FIFO-based client-server where unrelated processes send requests and receive responses.

### 3.2 Functional Requirements

1. **Requirement 1**: Server creates FIFO and waits for requests

2. **Requirement 2**: Client sends request with framing

3. **Requirement 3**: Server responds via per-client FIFO or stdout

4. **Requirement 4**: Graceful shutdown and cleanup

### 3.3 Non-Functional Requirements

- **Performance**: Must handle at least 10,000 messages/operations without failure.

- **Reliability**: IPC objects are cleaned up on shutdown or crash detection.

- **Usability**: CLI output is readable with clear error codes.

### 3.4 Example Usage / Output

```text

./fifo_server &

./fifo_client /tmp/svc hello

reply: hello

### 3.5 Data Formats / Schemas / Protocols

Length-prefixed messages: [u32 length][payload bytes].

### 3.6 Edge Cases

- Client opens before server

- Multiple clients interleave messages

- Server restart with stale FIFO

### 3.7 Real World Outcome

You will have a working IPC subsystem that can be run, traced, and tested in a reproducible way.

#### 3.7.1 How to Run (Copy/Paste)

```bash

make

./run_demo.sh

#### 3.7.2 Golden Path Demo (Deterministic)

```bash

./run_demo.sh --mode=golden

Expected output includes deterministic counts and a final success line:

```text

OK: golden scenario completed

#### 3.7.3 Failure Demo (Deterministic)

```bash

./run_demo.sh --mode=failure

Expected output:

```text

ERROR: invalid input or unavailable IPC resource

exit=2

---

## 4. Solution Architecture

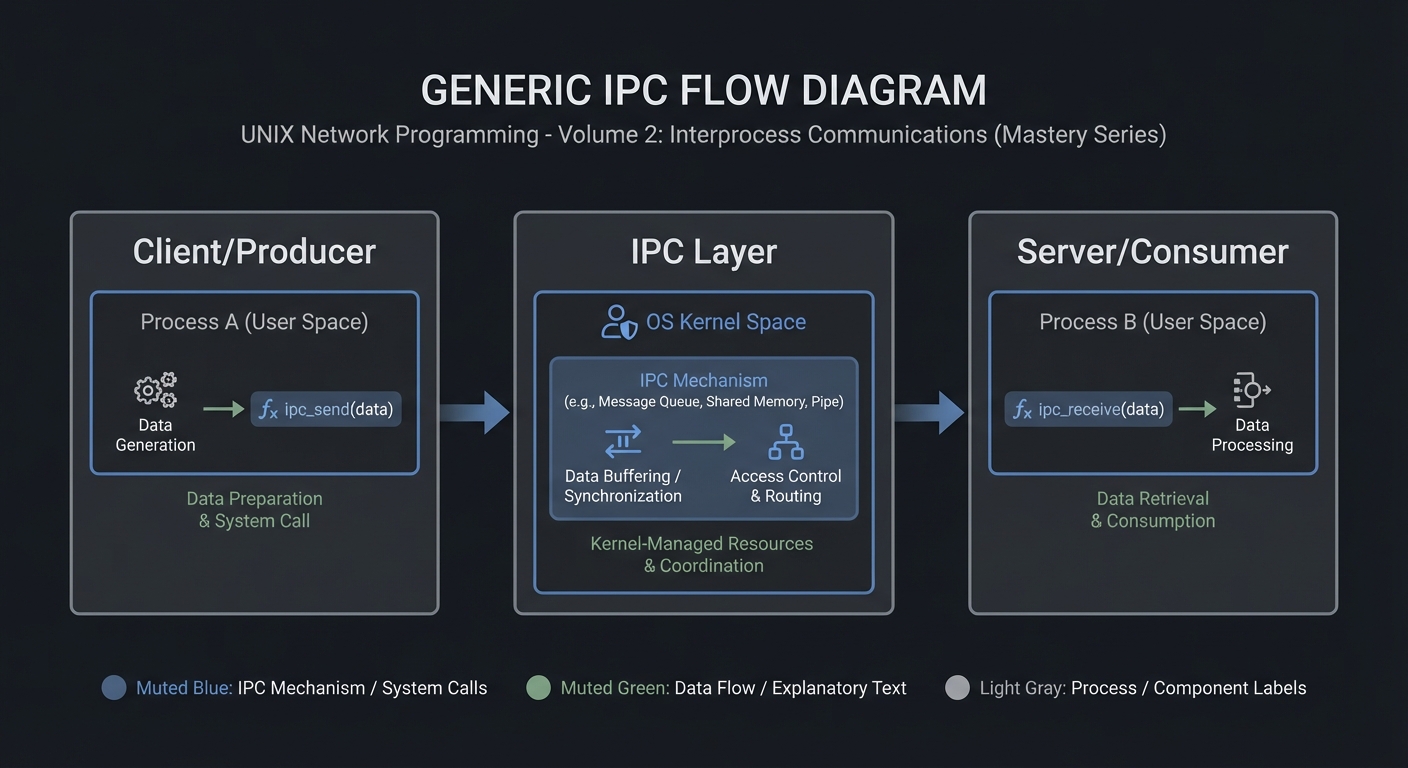

### 4.1 High-Level Design

Client/Producer -> IPC Layer -> Server/Consumer

4.2 Key Components

| Component | Responsibility | Key Decisions |

|---|---|---|

| IPC Setup | Create/open IPC objects | POSIX vs System V choices |

| Worker Loop | Send/receive messages | Blocking vs non-blocking |

| Cleanup | Unlink/remove IPC objects | Crash safety |

4.3 Data Structures (No Full Code)

struct message {

int id;

int len;

char payload[256];

};

### 4.4 Algorithm Overview

**Key Algorithm: IPC Request/Response**

1. Initialize IPC resources.

2. Client sends request.

3. Server processes and responds.

4. Cleanup on exit.

**Complexity Analysis:**

- Time: O(n) in number of messages.

- Space: O(1) per message plus IPC buffer.

---

## 5. Implementation Guide

### 5.1 Development Environment Setup

```bash

sudo apt-get install build-essential

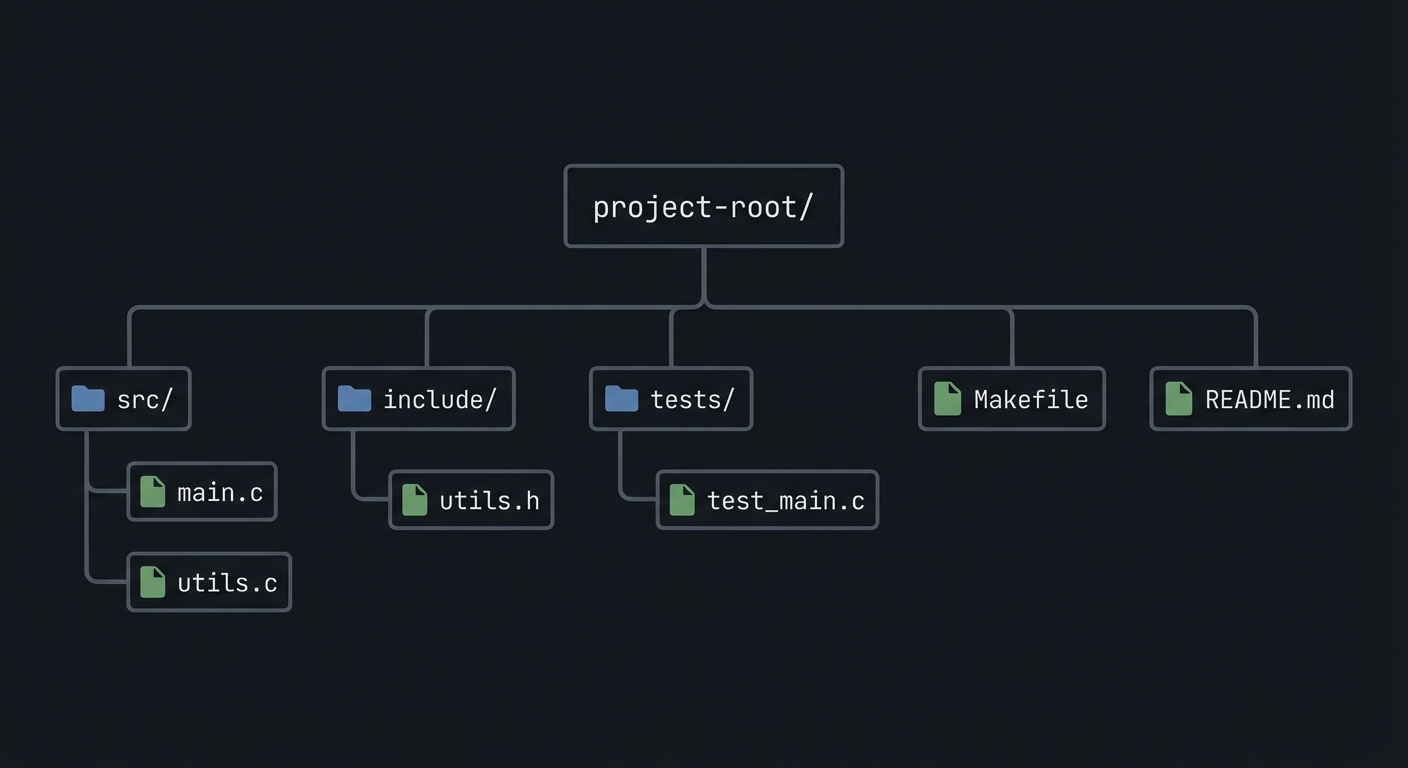

### 5.2 Project Structure

project-root/

├── src/

├── include/

├── tests/

├── Makefile

└── README.md

5.3 The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do unrelated processes rendezvous safely using only filesystem IPC?”

5.4 Concepts You Must Understand First

- IPC object lifecycle (create/open/unlink)

- Blocking vs non-blocking operations

- Error handling with errno

5.5 Questions to Guide Your Design

- What invariants guarantee correctness in this IPC flow?

- How will you prevent resource leaks across crashes?

- How will you make the system observable for debugging?

5.6 Thinking Exercise

Before coding, sketch the IPC lifecycle and identify where deadlock could occur.

5.7 The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- Why choose this IPC mechanism over alternatives?

- What are the lifecycle pitfalls?

- How do you test IPC code reliably?

5.8 Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with a single producer and consumer.

Hint 2: Add logging around every IPC call.

Hint 3: Use strace or ipcs to verify resources.

5.9 Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| IPC fundamentals | Stevens, UNP Vol 2 | Relevant chapters |

| System calls | APUE | Ch. 15 |

5.10 Implementation Phases

Phase 1: Foundation (2-4 hours)

Goals:

- Create IPC objects.

- Implement a minimal send/receive loop.

Tasks:

- Initialize IPC resources.

- Implement basic client and server.

Checkpoint: Single request/response works.

Phase 2: Core Functionality (4-8 hours)

Goals:

- Add error handling and cleanup.

- Support multiple clients or concurrent operations.

Tasks:

- Add structured message format.

- Implement cleanup on shutdown.

Checkpoint: System runs under load without leaks.

Phase 3: Polish & Edge Cases (2-4 hours)

Goals:

- Add deterministic tests.

- Document behaviors.

Tasks:

- Add golden and failure scenarios.

- Document limitations.

Checkpoint: Tests pass, behavior documented.

5.11 Key Implementation Decisions

| Decision | Options | Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blocking mode | blocking vs non-blocking | blocking | Simpler for first version |

| Cleanup | manual vs automated | explicit cleanup | Avoid stale IPC objects |

6. Testing Strategy

6.1 Test Categories

| Category | Purpose | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Unit Tests | Validate helpers | message encode/decode |

| Integration Tests | IPC flow | client-server round trip |

| Edge Case Tests | Failure modes | missing queue, full buffer |

6.2 Critical Test Cases

- Single client request/response works.

- Multiple requests do not corrupt state.

- Failure case returns exit code 2.

6.3 Test Data

Input: “hello” Expected: “hello”

7. Common Pitfalls & Debugging

7.1 Frequent Mistakes

| Pitfall | Symptom | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Not cleaning IPC objects | Next run fails | Add cleanup on exit |

| Blocking forever | Program hangs | Add timeouts or non-blocking mode |

| Incorrect message framing | Corrupted data | Add length prefix and validate |

7.2 Debugging Strategies

- Use

strace -fto see IPC syscalls. - Use

ipcsor/dev/mqueueto inspect objects.

7.3 Performance Traps

- Small queue sizes cause frequent blocking.

8. Extensions & Challenges

8.1 Beginner Extensions

- Add verbose logging.

- Add a CLI flag to toggle non-blocking mode.

8.2 Intermediate Extensions

- Add request timeouts.

- Add a metrics report.

8.3 Advanced Extensions

- Implement load testing with multiple clients.

- Add crash recovery logic.

9. Real-World Connections

9.1 Industry Applications

- IPC services in local daemons.

- Message-based coordination in legacy systems.

9.2 Related Open Source Projects

- nfs-utils - Uses RPC and IPC extensively.

- systemd - Uses multiple IPC mechanisms.

9.3 Interview Relevance

- Demonstrates system call knowledge and concurrency reasoning.

10. Resources

10.1 Essential Reading

- Stevens, “UNP Vol 2”.

- Kerrisk, “The Linux Programming Interface”.

10.2 Video Resources

- Unix IPC lectures from OS courses.

10.3 Tools & Documentation

man 7 ipc,man 2for each syscall.

10.4 Related Projects in This Series

11. Self-Assessment Checklist

11.1 Understanding

- I can describe IPC object lifecycle.

- I can explain blocking vs non-blocking behavior.

- I can reason about failure modes.

11.2 Implementation

- All functional requirements are met.

- Tests pass.

- IPC objects are cleaned up.

11.3 Growth

- I can explain design trade-offs.

- I can explain this project in an interview.

12. Submission / Completion Criteria

Minimum Viable Completion:

- Basic IPC flow works with correct cleanup.

- Error handling returns deterministic exit codes.

Full Completion:

- Includes tests and deterministic demos.

- Documents trade-offs and limitations.

Excellence (Going Above & Beyond):

- Adds performance benchmarking and crash recovery.