Project 1: Build a Shell Pipeline Executor

Build a miniature shell pipeline engine that wires multiple commands together with pipes, just like

cmd1 | cmd2 | cmd3.

Quick Reference

| Attribute | Value |

|---|---|

| Difficulty | Level 2 (Intermediate) |

| Time Estimate | Weekend |

| Main Programming Language | C (Alternatives: Rust, Go) |

| Alternative Programming Languages | Rust, Go |

| Coolness Level | Level 3 (Genuinely Clever) |

| Business Potential | Level 1 (Resume Gold) |

| Prerequisites | fork/exec basics, Unix file descriptors, basic C I/O, reading man pages |

| Key Topics | pipes, dup2, FD lifecycle, process tree, wait/waitpid, EOF propagation |

1. Learning Objectives

By completing this project, you will:

- Build a correct multi-stage pipeline that mirrors shell behavior.

- Explain and implement FD inheritance across fork and exec.

- Prevent deadlocks by closing the correct pipe ends in the correct processes.

- Implement robust error handling for each syscall involved in pipeline setup.

- Collect and interpret child exit status for multiple pipeline stages.

2. All Theory Needed (Per-Concept Breakdown)

Pipe-Based Pipelines and FD Redirection

Fundamentals

A Unix pipe is a unidirectional byte stream that connects a writer to a reader. When you call pipe(), the kernel creates a buffer and returns two file descriptors: one for reading, one for writing. The kernel implements the buffering, blocking, and wakeups so that reads block until data is written, and writes block when the pipe is full. Pipes are anonymous; they only exist as long as some process keeps a descriptor open. This makes them perfect for short-lived, tightly scoped communication like shell pipelines, but it also means you must be disciplined with closing unused ends.

Pipelines are built by connecting the stdout of one process to the stdin of another. The core mechanism is dup2(): it duplicates a file descriptor to a specific target number, such as 1 for stdout or 0 for stdin. A typical pipeline stage does the following: create a pipe, fork(), in the child dup2() the write end to stdout (or read end to stdin), close all unused FDs, then exec() the target program. The parent keeps the read end for the next stage and closes the write end immediately so that EOF can propagate when the last writer exits. If any process accidentally keeps an extra write end open, downstream readers will never see EOF and will hang waiting for more data.

Pipelines are also an exercise in understanding open file descriptions. When fork() occurs, both parent and child get copies of the file descriptor table pointing to the same kernel objects. That means closing a pipe end in one process does not destroy the pipe if another process still holds it. This explains many pipeline bugs: the programmer forgets to close an FD in the parent, so the kernel still sees a writer, so readers never see EOF. Pipelines are easy to build and easy to get subtly wrong, which is exactly why they are the perfect first IPC project.

Finally, pipelines teach the idea of composition. Each process is unaware it is part of a pipeline; it simply reads from stdin and writes to stdout. The pipeline is an external wiring of processes through IPC. This is the Unix philosophy made concrete, and by implementing it yourself you learn why file descriptors are the lingua franca of Unix IPC.

Deep Dive into the Concept

A correct pipeline implementation requires understanding three layers at once: the kernel’s pipe semantics, the process tree, and the FD redirection logic that binds them. Start with pipe semantics: a pipe has a fixed capacity (PIPE_BUF for atomic writes up to a limit), and the kernel enforces wakeup behavior for readers and writers. If there are no writers and all write ends are closed, read() returns 0 (EOF). If there are no readers and a process writes, the default behavior is SIGPIPE and EPIPE. That error is not just a curiosity: many pipeline programs rely on SIGPIPE to terminate early when a downstream stage exits. Your pipeline executor must not suppress or mishandle this behavior.

Now consider how to wire multiple stages. For N commands, you need N-1 pipes. Each command is a process. For stage i (0-based), stdin should come from the read end of pipe i-1 (except the first stage), and stdout should go to the write end of pipe i (except the last stage). The implementation often uses a loop that creates a pipe, forks, sets up redirection in the child, and then advances to the next stage in the parent. The tricky part is keeping track of which pipe ends to close at each step. A robust approach is: in the parent, after forking the child for stage i, close the write end of the current pipe immediately, and close the read end of the previous pipe because the parent no longer needs it. In the child, close all inherited pipe ends except the ones you need for stdin and stdout. This rule is the simplest way to avoid FD leaks.

Redirection uses dup2(oldfd, newfd). This call makes newfd refer to the same open file description as oldfd, closing newfd first if it is open. The detail that often confuses learners is that after dup2, you can and should close oldfd. The new FD remains valid and connected to the pipe. This is essential for cleanup and for making sure the child doesn’t keep extra pipe references alive. In a pipeline, every child should end with only FDs 0, 1, and 2 (stdin, stdout, stderr) unless you intentionally pass extra descriptors.

Another deep issue is error propagation and exit status. When the pipeline completes, the parent must wait for all children and capture exit statuses. Shells typically report the exit status of the last command, but they may also provide access to all statuses (pipefail in bash). You should decide and document your behavior. The parent should also be robust to short reads and writes and to EINTR, because long pipelines are a natural place for signals to interrupt syscalls. This project will force you to implement a clean child-spawn loop that handles errors mid-pipeline, cleaning up already-spawned children and closing FDs on failure.

Finally, consider observability. You should be able to run your pipeline under strace and see a clear sequence: pipe, fork, dup2, execve, close. If you don’t see that, your program is not doing the right thing. Observing a correct pipeline at the syscall level is a powerful mental model for every IPC mechanism that uses file descriptors.

How this fits on projects

Pipelines are the foundation for most IPC workflows that use byte streams. This concept underpins not only this project but also popen() and FIFO client-server patterns. When you master pipe wiring, you can reason about any FD-based IPC mechanism.

Definitions & key terms

- Pipe -> Kernel-managed unidirectional byte stream with read and write ends.

- FD redirection -> Rebinding stdin/stdout/stderr to a new FD via

dup2(). - EOF propagation ->

read()returns 0 when all writers close. - SIGPIPE -> Signal delivered when writing to a pipe with no readers.

- Open file description -> Kernel object shared across FDs after

duporfork.

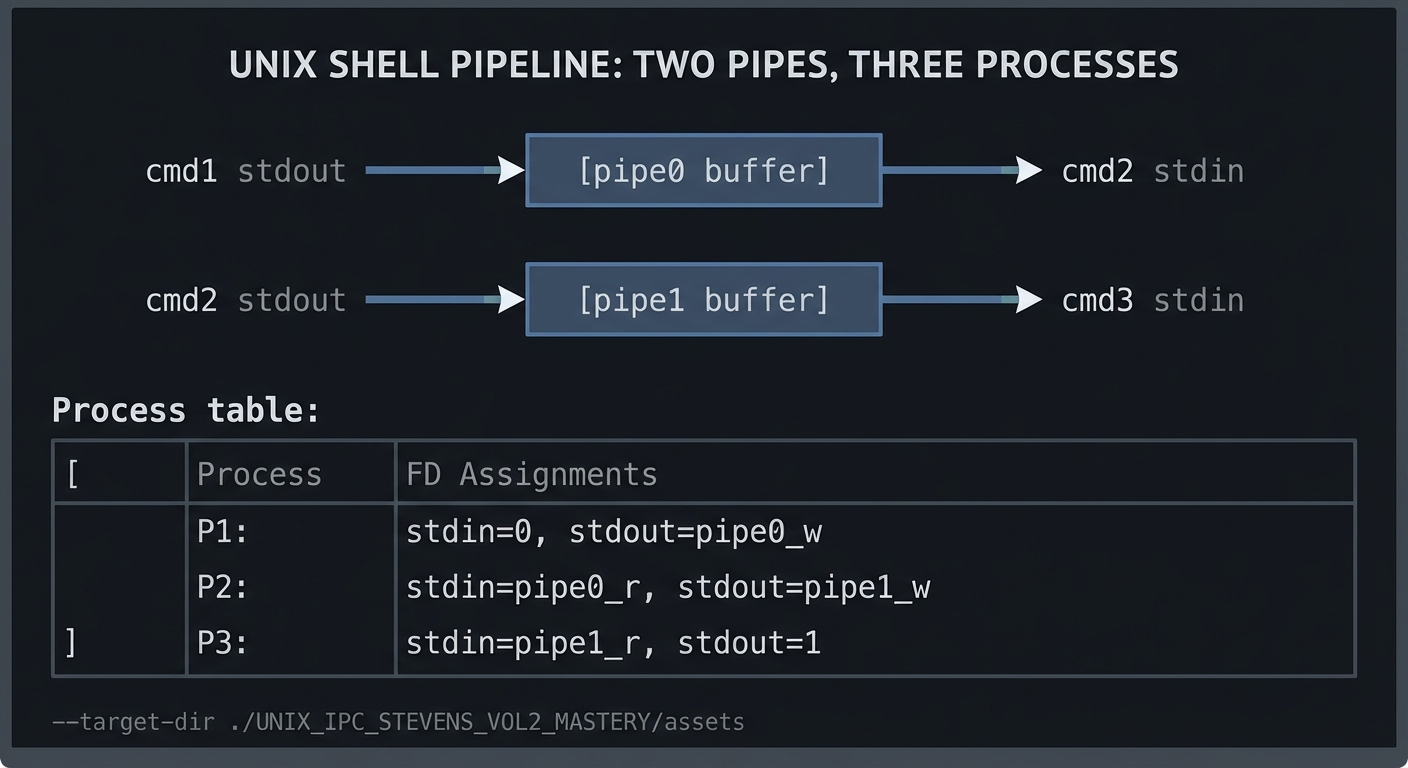

Mental model diagram (ASCII)

cmd1 stdout -> [pipe0 buffer] -> cmd2 stdin

cmd2 stdout -> [pipe1 buffer] -> cmd3 stdin

Process table:

P1: stdin=0, stdout=pipe0_w

P2: stdin=pipe0_r, stdout=pipe1_w

P3: stdin=pipe1_r, stdout=1

How it works (step-by-step, with invariants and failure modes)

- Create pipe for stage 0 -> 1.

fork()child for cmd1.- Child:

dup2(pipe0_w, STDOUT_FILENO), close all pipe ends,exec()cmd1. - Parent: close

pipe0_w(invariant: parent holds only read ends). - Create pipe for stage 1 -> 2, fork cmd2.

- Child:

dup2(pipe0_r, STDIN_FILENO),dup2(pipe1_w, STDOUT_FILENO), close all extras,exec()cmd2. - Parent: close

pipe0_randpipe1_wafter forking. - Repeat for all stages; last stage only gets stdin from last pipe, stdout stays as terminal.

- Parent waits for all children; collect statuses.

Failure modes: forgetting to close write ends causes hangs; closing read ends too early causes SIGPIPE or truncated data; ignoring EINTR can lead to leaked children.

Minimal concrete example

int p[2];

pipe(p);

if (fork() == 0) {

dup2(p[1], STDOUT_FILENO);

close(p[0]); close(p[1]);

execlp("ls", "ls", "-la", NULL);

_exit(127);

}

if (fork() == 0) {

dup2(p[0], STDIN_FILENO);

close(p[0]); close(p[1]);

execlp("wc", "wc", "-l", NULL);

_exit(127);

}

close(p[0]); close(p[1]);

wait(NULL); wait(NULL);

**Common misconceptions**

- "The pipe disappears when the child exits." -> It persists until all FDs are closed.

- "Closing the write end in the child is enough." -> The parent also holds a write end unless you close it.

- "`dup2()` copies data." -> It only rebinds FDs; no data is copied.

**Check-your-understanding questions**

1. Why does a reader hang if a writer FD is still open in an unrelated process?

2. What happens if a process writes to a pipe with no readers?

3. Why is `dup2()` preferred over `dup()` for pipelines?

**Check-your-understanding answers**

1. EOF is only delivered when all write ends are closed; any open writer keeps the pipe alive.

2. The writer gets `SIGPIPE` and `write()` fails with `EPIPE` unless SIGPIPE is ignored.

3. `dup2()` lets you target a specific FD like stdout (1) so exec'd programs use it.

**Real-world applications**

- Shells building pipelines and redirections.

- Log processors that stream data between filters.

- Build systems that chain compilers and formatters.

**Where you’ll apply it**

- In this project: §3.2 Functional Requirements, §4.1 High-Level Design, §5.10 Phase 2.

- Also used in: [P03-implement-popen.md](P03-implement-popen.md), [P02-fifo-client-server.md](P02-fifo-client-server.md).

**References**

- Stevens & Rago, "Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment" Ch. 15.

- Kerrisk, "The Linux Programming Interface" Ch. 44.

- `man 2 pipe`, `man 2 dup2`, `man 7 pipe`.

**Key insights**

- A pipeline is just careful FD wiring plus disciplined closure.

**Summary**

Pipelines are the canonical example of FD-based IPC: minimal kernel features, maximum leverage. Mastering them builds intuition for every other IPC mechanism.

**Homework/Exercises to practice the concept**

1. Write a program that builds a 2-stage pipeline and prints the FD table of each child.

2. Create a pipeline where the middle process exits early; observe `SIGPIPE`.

3. Reimplement a pipeline using non-blocking pipes and `poll()`.

**Solutions to the homework/exercises**

1. Use `/proc/<pid>/fd` in the child before `exec()` to list FDs.

2. Handle SIGPIPE in the writer and observe `EPIPE`.

3. Set `O_NONBLOCK` and use `poll()` on read/write ends.

---

### Process Lifecycle, fork/exec/wait, and FD Inheritance

**Fundamentals**

`fork()` creates a new process by duplicating the parent's address space and file descriptor table. The child receives copies of all open file descriptors, each pointing to the same underlying kernel objects. This means the child and parent share file offsets and flags, but have independent descriptor tables. `exec()` replaces the current process image with a new program while preserving file descriptors that are not marked `FD_CLOEXEC`. This combination is what makes Unix pipelines possible: you `fork()`, rewire FDs in the child, then `exec()` the target program.

`wait()` and `waitpid()` allow a parent to reap child processes and obtain their exit status. If you fail to wait, children become zombies and remain in the process table. Pipelines often spawn multiple children quickly, so robust waiting logic is essential. You must also handle partial failure: if one child fails to `exec`, you must decide whether to kill the pipeline or let others run.

FD inheritance is a double-edged sword. It makes pipelines possible, but it can also cause resource leaks and deadlocks if you forget to close inherited descriptors. The most disciplined approach is to close all FDs except stdin/stdout/stderr immediately before `exec()` unless you intentionally pass them through.

**Deep Dive into the Concept**

The fork/exec model is deceptively simple but full of subtleties. `fork()` creates a child with a copy-on-write memory map. The kernel does not copy all memory immediately; it marks pages as copy-on-write and only duplicates when modified. For pipeline construction, the memory cost is small, but the FD inheritance is immediate and explicit. Each FD points to an open file description, and that open file description has a reference count. That is why you cannot reason about EOF or resource lifetimes by thinking only about processes; you must reason about FDs and reference counts across the entire process tree.

`exec()` preserves the process ID and most kernel state but replaces code and data segments. Any error in setting up FDs before `exec()` is permanent for the lifetime of the child process. This is why best practice is: after `fork()`, do only the minimal FD wiring and error checking, then call `exec()` as soon as possible. In complex pipelines, you should also consider setting `FD_CLOEXEC` on any descriptors that you do not want leaked across `exec()`.

Waiting on children has its own pitfalls. If you use `wait()` in a loop, you will reap children in any order; if you need the exit code of the last stage, use `waitpid` with the specific PID. Also handle `EINTR` by retrying. Another subtlety: if you spawn many children and the parent exits early, children become orphaned and are reparented to PID 1; this can hide errors in your pipeline manager. A robust pipeline executor should stay alive until it has reaped all children and collected their exit statuses.

In practice, you will implement a small process supervisor: maintain an array of child PIDs, close FDs at the right times, and reap all children. This is the same pattern used in real process managers and service supervisors. The project therefore teaches an important systems programming skill beyond IPC: process supervision.

**How this fits on projects**

This concept appears in nearly every IPC project because `fork()` and `exec()` are the foundation of process-based architectures. You will use it in pipelines, FIFOs, and any project that spawns a worker process to handle IPC.

**Definitions & key terms**

- **fork()** -> Create a child process with duplicated FDs.

- **exec()** -> Replace process image while preserving FDs.

- **wait()/waitpid()** -> Reap child exit status to avoid zombies.

- **FD_CLOEXEC** -> Flag that closes FD on exec.

- **Zombie** -> Child that has exited but not yet reaped.

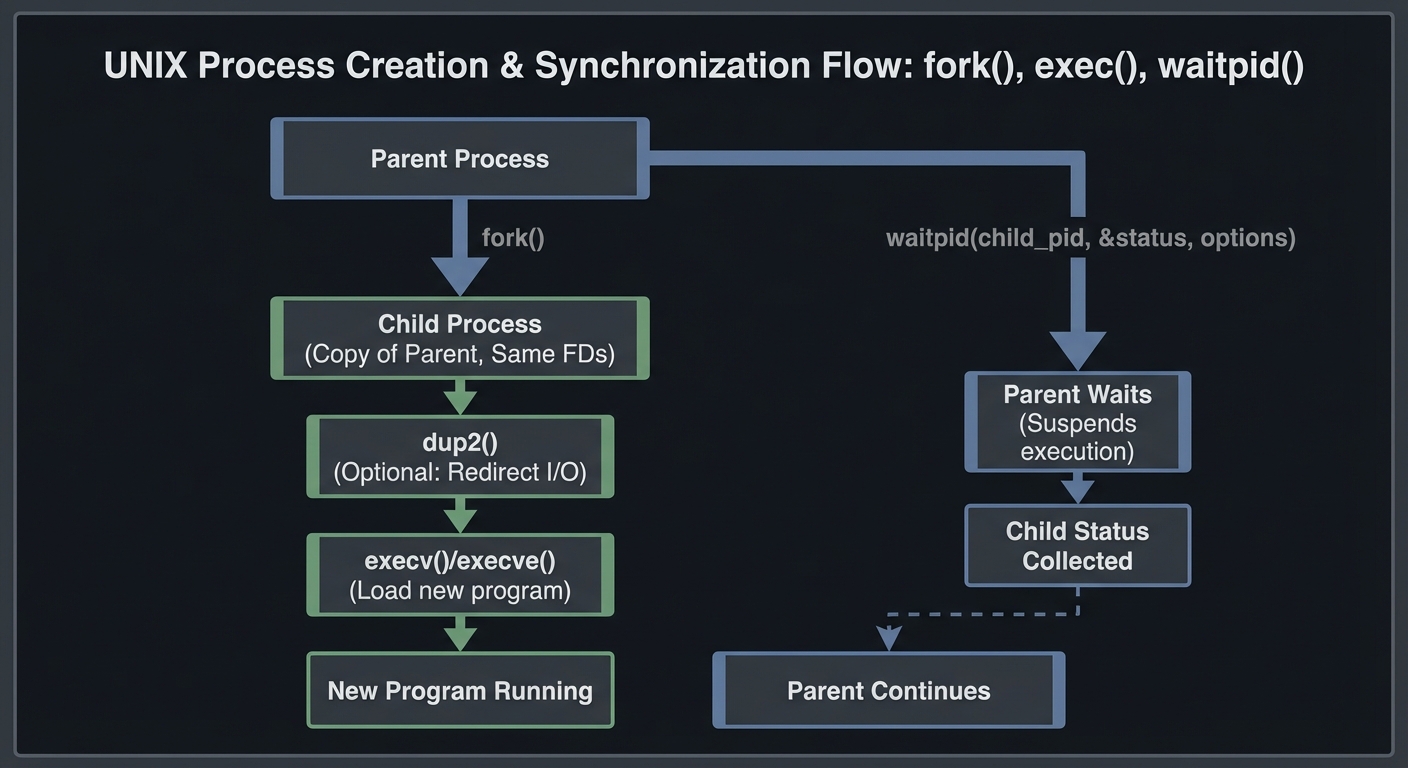

**Mental model diagram (ASCII)**

```text

Parent

| fork

v

Child (same FDs) -> dup2 -> exec new program

Parent -> waitpid(child)

How it works (step-by-step, with invariants and failure modes)

- Parent calls

fork(). - Child inherits all FDs and memory map.

- Child wires stdin/stdout via

dup2(). - Child closes unused FDs (invariant: only 0/1/2 remain).

- Child calls

exec(); on failure, exits with error code. - Parent closes unused FDs in its own table.

- Parent calls

waitpid()for all children.

Failure modes: not checking fork() errors, failing to wait() leading to zombies, forgetting to close FDs causing IPC hangs.

Minimal concrete example

pid_t pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

execlp("echo", "echo", "hello", NULL);

_exit(127);

}

int status;

waitpid(pid, &status, 0);

**Common misconceptions**

- "`exec()` creates a new process." -> It replaces the current process image.

- "Closing an FD in the child affects the parent." -> It only affects the child's table.

- "Zombies are harmless." -> They consume process table slots.

**Check-your-understanding questions**

1. Why does a child inherit file descriptors after `fork()`?

2. What happens to an FD marked `FD_CLOEXEC` after `exec()`?

3. Why do you need to call `wait()` even if you do not care about exit status?

**Check-your-understanding answers**

1. `fork()` duplicates the descriptor table to preserve I/O state.

2. It is automatically closed in the new process image.

3. To reap the child and prevent zombies.

**Real-world applications**

- Shells and pipeline managers.

- Process supervisors like systemd and runit.

- Worker pools that `fork()` per request.

**Where you’ll apply it**

- In this project: §4.2 Key Components, §5.10 Implementation Phases.

- Also used in: [P03-implement-popen.md](P03-implement-popen.md), [P02-fifo-client-server.md](P02-fifo-client-server.md).

**References**

- Stevens & Rago, APUE Ch. 8 and 15.

- Kerrisk, TLPI Ch. 24-27.

- `man 2 fork`, `man 2 execve`, `man 2 waitpid`.

**Key insights**

- Correct IPC depends on disciplined process lifecycle management, not just I/O calls.

**Summary**

Fork/exec and FD inheritance are the backbone of Unix IPC. Mastering them transforms pipelines from black magic into predictable, debuggable systems.

**Homework/Exercises to practice the concept**

1. Write a parent that forks three children and waits in reverse order.

2. Set `FD_CLOEXEC` on a pipe FD and observe it closing across `exec()`.

3. Intentionally skip `wait()` and observe zombies with `ps`.

**Solutions to the homework/exercises**

1. Store PIDs and `waitpid` on each explicitly.

2. Use `fcntl(fd, F_SETFD, FD_CLOEXEC)` before `exec()`.

3. Run `ps -o pid,ppid,state,comm` and see `Z` state children.

---

## 3. Project Specification

### 3.1 What You Will Build

A CLI program `mypipe` that accepts 2 to 5 commands as arguments and executes them in a pipeline. Each command is executed via `execvp`, with stdin/stdout wired to pipes so that the output of stage i becomes input of stage i+1. The program must collect exit status for each stage and report a final status in a consistent and documented way.

Included:

- Parsing commands into argv arrays (simple quoting support optional).

- N-stage pipelines with proper FD management.

- Exit status collection for all stages.

Excluded:

- Shell built-ins, job control, or background execution.

- Full quoting and glob expansion (use `execvp`).

### 3.2 Functional Requirements

1. **Pipeline Execution**: Support 2-5 stages with correct stdin/stdout wiring.

2. **FD Hygiene**: Close all unused pipe ends in both parent and child.

3. **Status Reporting**: Print per-stage exit code and overall status.

4. **Error Handling**: Handle errors from `pipe`, `fork`, `dup2`, `execvp` with readable messages.

5. **Signal Handling**: Propagate SIGPIPE correctly and do not mask it unintentionally.

### 3.3 Non-Functional Requirements

- **Performance**: Launch pipelines without noticeable delay (under 50ms for 3 stages on typical dev hardware).

- **Reliability**: No zombie processes; no leaked file descriptors.

- **Usability**: Simple CLI with clear errors and a usage message.

### 3.4 Example Usage / Output

```text

$ ./mypipe "ls -la" "grep txt" "wc -l"

2

$ ./mypipe "cat /etc/passwd" "grep root" "cut -d: -f1"

root

### 3.5 Data Formats / Schemas / Protocols

- **Command input format**: Each command is a single CLI argument string; split on spaces, honoring simple quotes if you implement them.

- **Exit status format**: Print `stage=N exit=CODE` for each stage; final line `pipeline exit=CODE`.

### 3.6 Edge Cases

- Command not found (exec fails).

- Middle stage exits early (SIGPIPE to upstream).

- Empty output (pipeline prints nothing).

- Large outputs (ensure no deadlock).

### 3.7 Real World Outcome

You will be able to use `mypipe` as a drop-in educational replacement for simple shell pipelines, and you can trace its syscall behavior to explain pipeline mechanics.

#### 3.7.1 How to Run (Copy/Paste)

```bash

cd /path/to/project

make

./mypipe "ls -la" "grep txt" "wc -l"

#### 3.7.2 Golden Path Demo (Deterministic)

Use a fixed input file for deterministic output.

```bash

printf "a\nb\nc\n" > /tmp/mypipe-input.txt

./mypipe "cat /tmp/mypipe-input.txt" "grep b" "wc -l"

Expected output:

```text

1

#### 3.7.3 Failure Demo (Deterministic)

```bash

./mypipe "nosuchcmd" "wc -l"

Expected output:

```text

stage=1 exit=127

pipeline exit=127

---

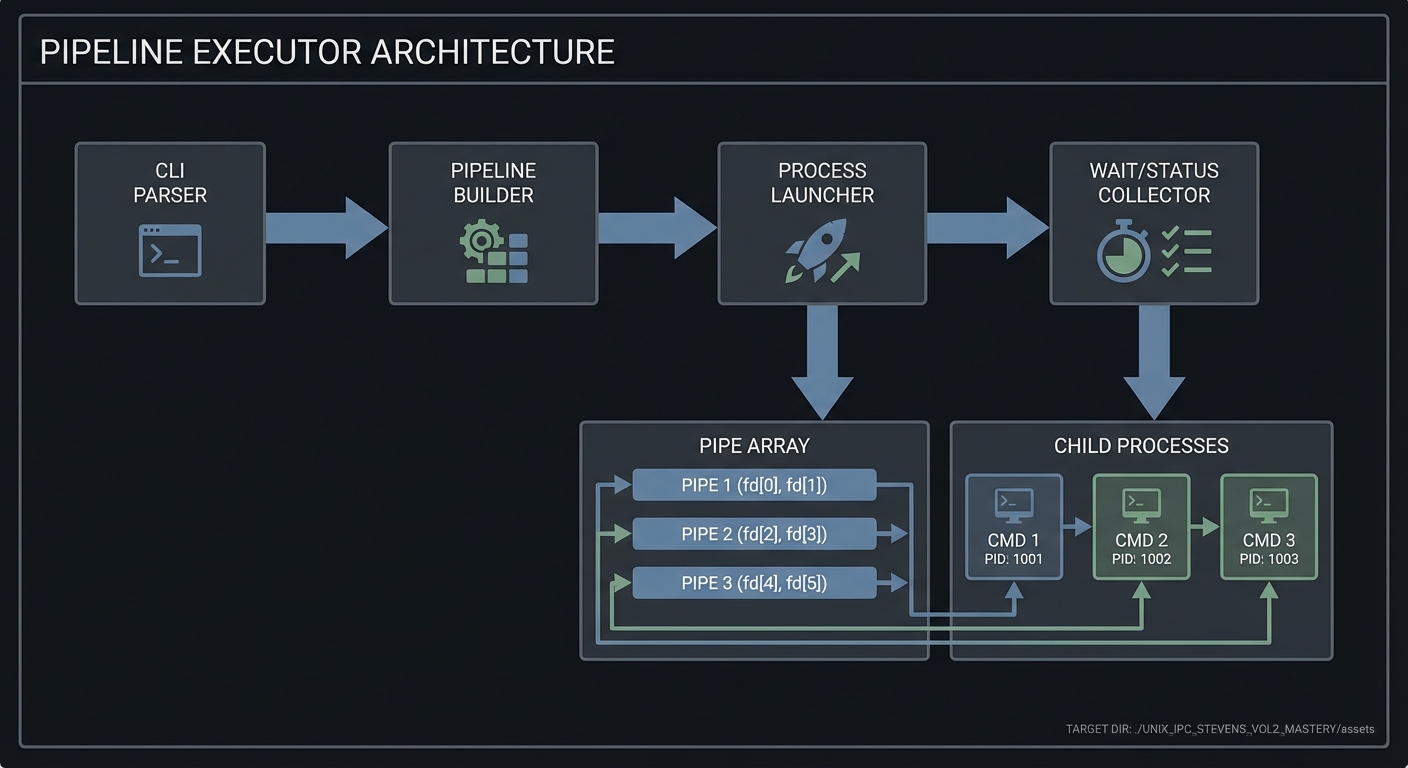

## 4. Solution Architecture

### 4.1 High-Level Design

CLI Parser -> Pipeline Builder -> Process Launcher -> Wait/Status Collector

| |

v v

Pipe Array Child Processes

4.2 Key Components

| Component | Responsibility | Key Decisions |

|---|---|---|

| Parser | Split commands into argv arrays | Simple split vs quote-aware split |

| Pipeline Builder | Create N-1 pipes and map them to stages | Iterate and reuse last read end |

| Launcher | fork + dup2 + exec for each stage | Close FDs aggressively |

| Status Collector | waitpid all children | Report last stage status |

4.3 Data Structures (No Full Code)

struct Stage {

char **argv;

pid_t pid;

};

struct Pipeline {

struct Stage stages[MAX_STAGES];

int count;

};

### 4.4 Algorithm Overview

**Key Algorithm: Build and Execute Pipeline**

1. Parse CLI into N stage argv arrays.

2. For each stage i:

- Create pipe if not last stage.

- fork child.

- Child: dup2 previous read end to stdin, dup2 current write end to stdout, close all FDs, exec.

- Parent: close write end, close previous read end, keep current read end.

3. Wait for all children; report statuses.

**Complexity Analysis:**

- Time: O(N) process creation plus child runtime.

- Space: O(N) for pipes and argv arrays.

---

## 5. Implementation Guide

### 5.1 Development Environment Setup

```bash

sudo apt-get install build-essential strace lsof

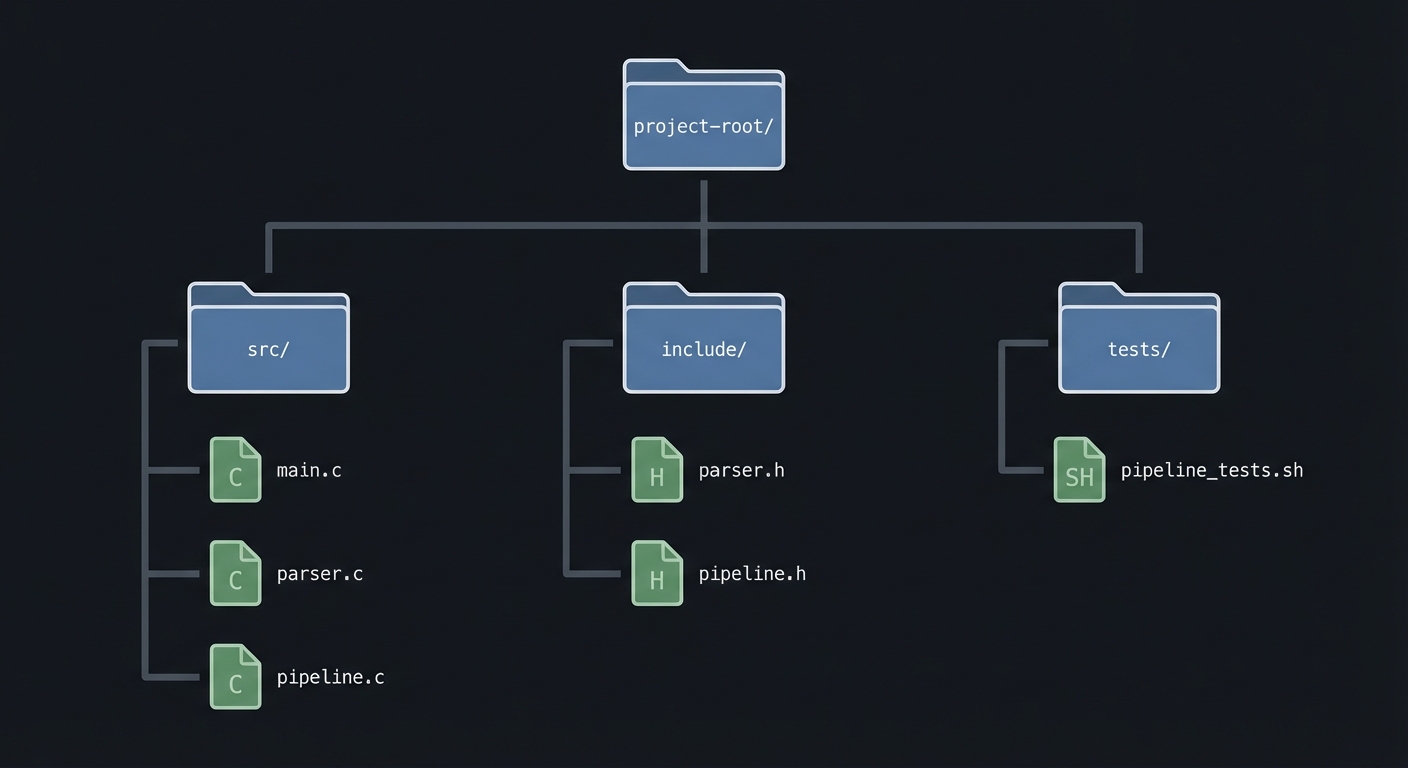

### 5.2 Project Structure

project-root/

├── src/

│ ├── main.c

│ ├── parser.c

│ └── pipeline.c

├── include/

│ ├── parser.h

│ └── pipeline.h

├── tests/

│ └── pipeline_tests.sh

├── Makefile

└── README.md

5.3 The Core Question You’re Answering

“How does a shell connect processes so that output from one becomes input for the next, and what makes that reliable?”

5.4 Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Pipe semantics and EOF

- When does a reader see EOF?

- What happens when all writers close?

- FD duplication and redirection

- Why

dup2()is used to connect stdout/stdin.

- Why

- Process lifecycle

fork(),exec(),waitpid()and zombies.

5.5 Questions to Guide Your Design

- How will you decide which stage gets which pipe end?

- How will you ensure no extra pipe write ends remain open?

- How will you report errors and exit status clearly?

5.6 Thinking Exercise

“The Stuck Reader”

Imagine a 3-stage pipeline where the middle stage exits early. Which processes still have the write end of the first pipe open? How would you ensure EOF reaches the reader?

5.7 The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- Why does forgetting to close a pipe write end cause a hang?

- How does

dup2()work under the hood? - How do you capture exit status in a pipeline?

5.8 Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Build a 2-stage pipeline first

Start with cmd1 | cmd2 before generalizing.

Hint 2: Draw the FD table Sketch each process’s FDs after wiring.

Hint 3: Use strace

Confirm the syscall order: pipe, fork, dup2, execve.

5.9 Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Pipes and redirection | APUE (Stevens & Rago) | Ch. 15 |

| Process control | APUE | Ch. 8 |

| IPC overview | TLPI (Kerrisk) | Ch. 44 |

5.10 Implementation Phases

Phase 1: Foundation (2-4 hours)

Goals:

- Parse CLI into stages.

- Execute a 2-stage pipeline.

Tasks:

- Parse two command strings into argv arrays.

- Implement a

run_pipeline(stages, count)for 2 stages.

Checkpoint: ./mypipe "ls" "wc -l" works.

Phase 2: Core Functionality (4-6 hours)

Goals:

- Support 3-5 stages.

- Ensure FD hygiene.

Tasks:

- Add looped pipeline creation.

- Close unused FDs systematically.

- Collect PIDs and wait for all children.

Checkpoint: ./mypipe "cat file" "grep x" "wc -l" works.

Phase 3: Polish & Edge Cases (2-4 hours)

Goals:

- Robust error handling.

- Deterministic exit reporting.

Tasks:

- Print per-stage exit codes.

- Handle exec failure and SIGPIPE.

Checkpoint: Failure cases produce meaningful output.

5.11 Key Implementation Decisions

| Decision | Options | Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exit status reporting | last-stage only vs all stages | all stages | Helps debug and mirrors pipefail |

| Parsing complexity | simple split vs quote-aware | simple split | Keeps focus on IPC |

| Error policy | stop on error vs best-effort | stop on setup error | Avoid partially wired pipelines |

6. Testing Strategy

6.1 Test Categories

| Category | Purpose | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Unit Tests | Parser correctness | split strings, handle quotes |

| Integration Tests | Pipeline wiring | echo -> wc |

| Edge Case Tests | Error paths | missing command, SIGPIPE |

6.2 Critical Test Cases

- Two-stage pipeline:

echo hello | wc -creturns6. - Three-stage pipeline:

cat file | grep x | wc -lmatches shell output. - Exec failure: missing command returns exit 127.

6.3 Test Data

input.txt: a b b c

Expected output for cat input.txt | grep b | wc -l:

2

7. Common Pitfalls & Debugging

7.1 Frequent Mistakes

| Pitfall | Symptom | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Not closing write ends | Pipeline hangs | Close write ends in parent and child |

| Forgetting to wait | Zombies | Collect all child PIDs |

| Wrong dup order | No output | dup2 before closing FDs |

7.2 Debugging Strategies

- Use

lsof -p <pid>to inspect open pipe ends. - Use

strace -fto trace fork/exec/dup2 calls.

7.3 Performance Traps

- Spawning too many stages with large outputs can exhaust pipe buffers.

8. Extensions & Challenges

8.1 Beginner Extensions

- Add support for quoted arguments.

- Add a

--statusflag to print exit codes.

8.2 Intermediate Extensions

- Implement

pipefailbehavior. -

[ ] Support stderrpiping (2>).

8.3 Advanced Extensions

- Add non-blocking pipes with

poll(). - Implement a small job control subsystem.

9. Real-World Connections

9.1 Industry Applications

- Shells and build systems rely on pipeline execution.

- Data processing tools chain multiple stages for throughput.

9.2 Related Open Source Projects

- bash - reference for pipeline semantics.

- dash - minimal shell; great for reading.

9.3 Interview Relevance

- Explains FD inheritance, process control, and SIGPIPE.

10. Resources

10.1 Essential Reading

- “Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment” (Stevens & Rago) Ch. 8, 15.

- “The Linux Programming Interface” (Kerrisk) Ch. 44.

10.2 Video Resources

- Unix pipe and redirection lectures (university OS courses).

10.3 Tools & Documentation

man 2 pipe,man 2 dup2,man 2 fork.straceandlsof.

10.4 Related Projects in This Series

- P02-fifo-client-server.md - named pipes for unrelated processes.

- P03-implement-popen.md - popen is a pipeline wrapper.

11. Self-Assessment Checklist

11.1 Understanding

- I can explain EOF propagation through a pipe.

- I can draw FD tables for a 3-stage pipeline.

- I understand why SIGPIPE occurs.

11.2 Implementation

- All pipeline stages run correctly.

- All child processes are reaped.

- No file descriptors leak.

11.3 Growth

- I can describe one design trade-off I made.

- I can explain this project in an interview.

12. Submission / Completion Criteria

Minimum Viable Completion:

- Executes 2-5 stage pipelines correctly.

- Closes unused FDs and reaps all children.

- Reports exit status for each stage.

Full Completion:

- Includes robust error handling and tests.

- Handles SIGPIPE and exec failures gracefully.

Excellence (Going Above & Beyond):

- Implements

pipefailand non-blocking mode. - Provides a detailed syscall trace in the README.