Project 4: Embedding and Vector Index Baseline

Embed change chunks and build a vector index for semantic search.

Quick Reference

| Attribute | Value |

|---|---|

| Difficulty | Level 3: Advanced |

| Time Estimate | 1-2 weeks |

| Main Programming Language | Python (Alternatives: Go, Rust, JavaScript) |

| Alternative Programming Languages | Go, Rust, JavaScript |

| Coolness Level | Level 3: Genuinely Clever |

| Business Potential | Level 3: Service and Support Model |

| Prerequisites | Change chunks from Project 3, Basic understanding of embeddings, Awareness of vector search tradeoffs |

| Key Topics | Embedding representations for diffs, Vector index construction, Metadata filters and tags, Index updates and compaction, Model versioning |

1. Learning Objectives

By completing this project, you will:

- Model change evidence with stable provenance and metadata.

- Design a robust pipeline stage that feeds later retrieval steps.

- Identify and mitigate the primary failure modes for this stage.

- Produce outputs that can be validated with clear tests.

2. All Theory Needed (Per-Concept Breakdown)

Embedding representations and vector indexing for diffs

Fundamentals

Embedding representations and vector indexing for diffs is the discipline of turning raw change signals into stable, retrievable knowledge. At a minimum, it must preserve embedding inputs for diffs, approximate nearest neighbor search, and metadata filtering and routing so that later questions can be answered without guessing. This is not just data collection; it is building a dependable memory of how the system evolved. When a code agent asks a question, it depends on the integrity of this memory. If the memory is incomplete or mislabeled, the agent will answer confidently but incorrectly.

In a change-aware RAG pipeline, Embedding representations and vector indexing for diffs provides the base layer for retrieval. The retriever and ranker can only operate on what has been captured, which means the design of records, identifiers, and metadata must be deliberate. You need enough structure to filter by scope, enough provenance to trace evidence to commits and files, and enough normalization to make future indexing stable. This is why index freshness and updates and evaluation of embedding quality are part of the fundamentals, not optional enhancements.

The key to fundamentals is minimizing ambiguity. Every change record must answer: what changed, where it changed, when it changed, and why it changed. The what is captured in diffs and hunks, the where is captured in file paths and symbol names, the when is captured in commit timestamps and ordering, and the why is captured in rationale text. When these fields are consistent, downstream tasks become straightforward. When they are inconsistent, retrieval fails in subtle ways.

A strong foundation also makes scope explicit. That means tagging changes with module, service, or ownership metadata so later queries can be narrowed. This is especially important when the same vocabulary appears in multiple parts of a monorepo. Without clear scope tags, retrieval will surface similar but irrelevant changes. Scope tags also support access control policies when teams need different visibility levels.

Data quality is the other half of the fundamentals. Even if approximate nearest neighbor search is implemented, the output is only useful if formatting noise is removed and low- signal changes are flagged. A change pipeline should tag changes by type and mark evidence that is likely not behavioral. This helps later ranking stages avoid irrelevant evidence. It also reduces the size of your index and improves search latency.

Interfaces between stages matter as much as the stages themselves. If the change ledger cannot provide stable identifiers or consistent metadata, retrieval will become brittle. Define a minimal contract for each record and treat it like an API. This approach allows future improvements without breaking downstream consumers.

Another fundamental is repeatability. Ingestion should be deterministic given the same input history. Determinism is how you debug and how you build trust. If the same commit produces different records across runs, your pipeline is not reliable enough for an agent to trust. Repeatability is also essential for evaluation and regression testing.

Finally, fundamentals include failure awareness. Noise from formatting changes, missing commit messages, and rename events can corrupt the evidence pool. A solid baseline treats these as first-class signals. You do not need perfection, but you do need visibility. This is why the foundational design includes explicit flags, quality indicators, and traceable ids that make errors discoverable before they reach the agent.

Deep Dive into the concept

In a deep dive, Embedding representations and vector indexing for diffs becomes a system of tradeoffs. For embedding inputs for diffs, you must decide how to traverse history: topological order, time order, or branch-aware order. Each choice affects reproducibility. Topological order preserves parent relationships but can surprise users who expect chronological results. Time order is intuitive but can interleave branches in ways that obscure causality. A robust pipeline often stores both views so the ranker can choose the right one for a given question.

For approximate nearest neighbor search and metadata filtering and routing, you face structure versus speed. Rich schemas improve retrieval but cost storage and ingestion time. The schema should be normalized enough to avoid duplication and denormalized enough to support fast filtering. This is a classic systems design choice. You can keep a normalized core ledger and materialize search-friendly views for retrieval. This layered design supports both correctness and performance.

Index freshness and updates introduces reliability questions. Incremental ingestion is fragile if you do not track cursors carefully. Consider force pushes, rebases, and rewritten history. In controlled environments, you may rely on linear main branch history. In open source or complex teams, you must assume that history can change. One strategy is to treat ingestion as idempotent and allow reprocessing of a window of recent commits. This reduces the risk of missing changes.

Evaluation of embedding quality is not just about storing ids. Provenance is a contract: for any retrieved chunk, you must be able to reproduce the original diff and show exactly where it came from. This enables auditing and debugging. It also supports explainability for code agents. Without a provenance chain, you cannot test whether retrieval is correct. The deeper insight is that provenance is a prerequisite for evaluation, not a byproduct.

Change-aware systems benefit from dual representations: raw evidence and normalized views. Raw evidence is essential for trust and auditability, while normalized views improve search. The trick is to keep these views linked. Every normalized chunk should point back to raw diff lines and original commit ids. This reduces the risk of drifting semantics between what you search and what you show the agent.

Scaling Embedding representations and vector indexing for diffs also requires quality gates. You will encounter commits that are trivial reformats or mass renames. These can swamp retrieval with noise. The system should classify changes by type and allow policies that down-rank or suppress low-signal changes. This is not censorship; it is a form of signal-to-noise management that makes retrieval useful.

Instrumentation is a deep requirement. You should log ingestion stats, hunk counts, chunk sizes, and error rates. These metrics indicate whether your capture process is healthy. If a new parser update suddenly reduces average chunk counts, you may have silently broken the pipeline. Observability keeps the system honest. Treat ingestion like a production service with dashboards and alerts.

Testing strategy should include golden commits with known behavior changes. If a golden commit is ingested and the derived records change unexpectedly, it signals a breaking change in your parser or schema. Keeping a small set of golden commits provides stable regression tests for the ingestion pipeline.

Performance tuning often involves balancing batch and incremental workloads. Batch processing is efficient for initial history backfills, while incremental updates are needed for daily use. A hybrid strategy keeps both paths healthy. If either path is ignored, the system drifts and retrieval quality decays.

Data lifecycle policy is another deep consideration. Decide what history to retain, whether to prune low-signal diffs, and how to archive old records. Retention policies affect recall and storage costs. For agents, long retention improves historical answers but can require tighter ranking and filtering.

Edge cases drive the true complexity of Embedding representations and vector indexing for diffs. You must handle deletions, renames, merge commits, and partial reversions without losing lineage. Each edge case changes the interpretation of evidence, especially when a question asks about the origin of a behavior. Explicitly modeling these cases is the difference between a demo and a dependable system.

Consistency rules matter when multiple time sources disagree. Author time, commit time, and merge time can differ. Decide which timestamp is canonical for ranking, and store the others for audit and troubleshooting. A consistent time policy prevents subtle ranking bugs when users ask for changes during a specific window.

Resource constraints are real. Large repositories can generate millions of hunks. Compression and columnar storage can reduce cost, while tiered storage can keep recent data fast. If you ignore resource constraints, the pipeline becomes too expensive to operate and eventually gets turned off, which defeats the purpose.

Governance matters because code changes reflect human decisions. Encourage strong commit messages, consistent labeling, and clear PR descriptions. When human context is weak, the retriever is forced to rely on code signals alone, which is brittle for why- questions. Good governance is therefore a retrieval optimization, not just a process improvement.

Another deep layer is policy alignment. If the system is used for regulated or sensitive projects, the change ledger must encode policy metadata that supports audit requirements. These policies can dictate who can see which changes and how long they should be retained. Embedding policy signals into the evidence record avoids bolting on security later.

The evaluation loop should connect back to ingestion. When retrieval failures happen, your triage process must tell you whether the root cause was poor capture, poor chunking, or poor ranking. This feedback loop drives iterative improvement. Without it, the system stagnates and users lose trust.

Finally, the deep dive includes the human interface. Developers rely on clear explanations of what a change means. If your change records are inscrutable, the agent cannot help. You should include rationale text, commit summaries, and links to related issues so the evidence is interpretable. This is where data modeling meets usability. A good change ledger is not just correct; it is readable.

As you mature the system, you can add quality scores that represent confidence in each change record. These scores can depend on review status, test outcomes, or the presence of rationale text. When the ranker sees low-confidence evidence, it can either demote it or require additional corroboration. This is how a change pipeline becomes robust under real operational pressure.

How this fit on projects

This concept underpins the core mechanics of this project and ensures the outputs are usable by later stages in the change-aware RAG pipeline.

Definitions & key terms

- Embedding representations and vector indexing for diffs: the disciplined method for structuring change evidence

- provenance chain: a trace from chunk to commit, file, and line range

- signal-to-noise ratio: the proportion of meaningful change content to noise

- change record: a structured representation of a single commit or hunk

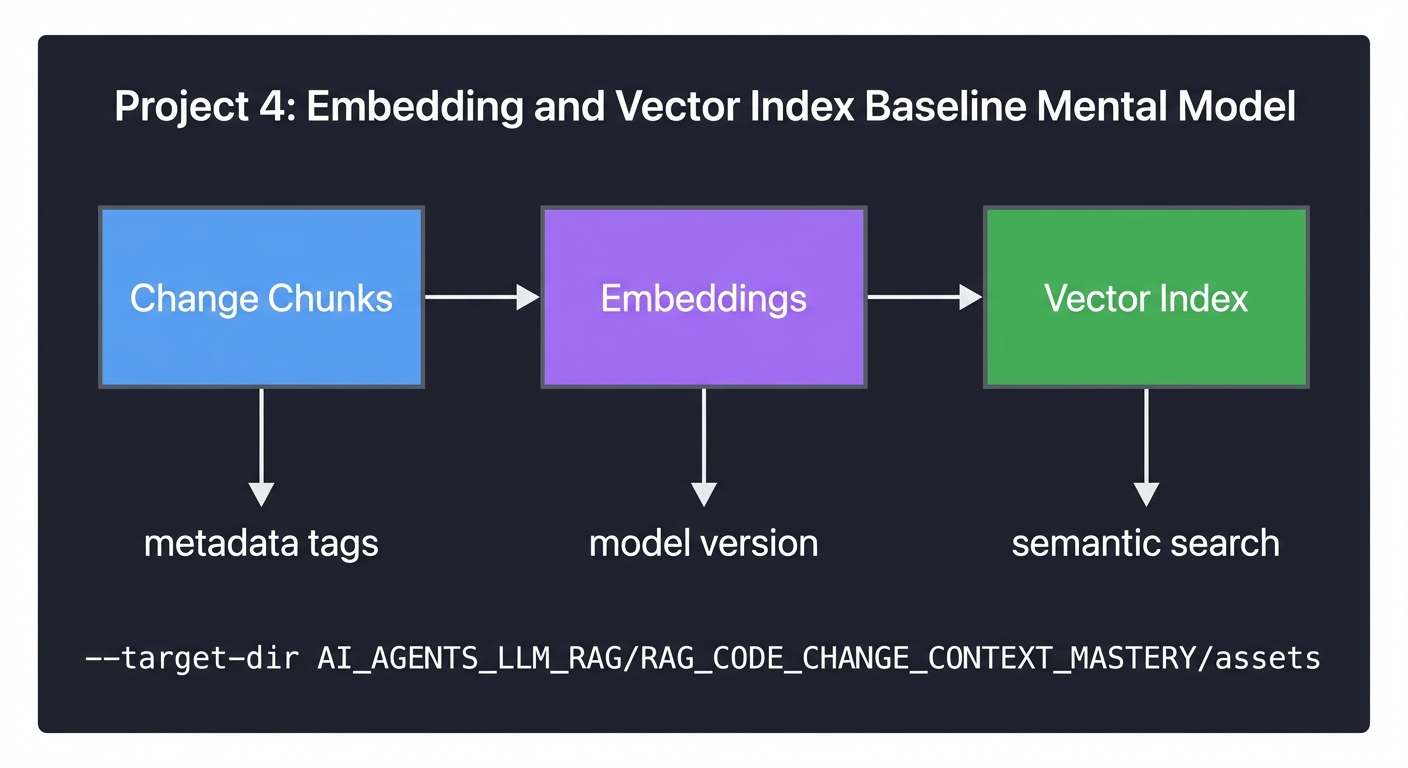

Mental model diagram

[Change Chunks] -> [Embeddings] -> [Vector Index]

| | |

v v v

metadata tags model version semantic search

How it works (step-by-step, with invariants and failure modes)

- Identify the inputs required for the concept in this project.

- Normalize and structure the inputs into stable records.

- Store evidence with provenance so it can be retrieved later.

- Enforce invariants: every chunk has a stable id and traceable source.

- Detect failure modes such as missing metadata, noisy diffs, or ambiguous scope.

Minimal concrete example (pseudocode or CLI output)

INPUT: chunk text + rationale text

STEP 1: create code embedding and rationale embedding

STEP 2: store vectors with metadata tags

STEP 3: query by semantic text and filter by repo

OUTPUT: ranked semantic matches

Common misconceptions

- One embedding channel is enough for every question.

- Vector search replaces keyword search entirely.

- Index updates are trivial.

Check-your-understanding questions

- Why separate code and rationale embeddings?

- What is the tradeoff between recall and latency?

- How do you handle stale indexes?

Check-your-understanding answers

- Because code and intent use different language and signals.

- Higher recall often requires larger indexes or slower search.

- Use incremental updates and periodic compaction.

Real-world applications

- Semantic search over change history

- Finding similar changes across services

- Trend analysis for recurring modifications

Where you will apply it

- Project 5 (Hybrid Retrieval)

- Project 6 (Time-Aware Ranker)

- Project 12 (End-to-End RAG CLI)

References

- Designing Data-Intensive Applications - Ch. 5

- FAISS paper and HNSW paper

- CodeSearchNet paper

Key insights

- Embedding quality defines the ceiling for semantic retrieval.

Summary

A vector index makes natural-language change queries possible, but only with good representations.

Homework/Exercises to practice the concept

- Design two embedding inputs: one for code diffs and one for rationale.

- List metadata tags that must accompany each vector.

- Estimate index size growth over six months.

Solutions to the homework/exercises

- Code diff text plus a normalized version; rationale text from commit and PR notes.

- Repo, path, service, timestamp, commit id, change type, model version.

- Use average chunks per month times retention window.

3. Implementation Plan (No Code)

Milestone 1: Define inputs and outputs

- Specify the raw inputs (diffs, metadata, query intent) and expected outputs.

- Create a checklist of invariants that must hold after processing.

Milestone 2: Build the core transformation

- Implement a deterministic pipeline stage that produces structured records.

- Include validation steps and error handling for edge cases.

Milestone 3: Add verification and logging

- Define CLI outputs or logs that prove each stage is working.

- Add small sample runs that you can repeat after changes.

Milestone 4: Integrate with the next project

- Confirm the outputs are compatible with the next pipeline component.

- Document any assumptions that downstream stages must respect.

4. Definition of Done

- The project produces stable outputs for at least 3 sample commits or change scenarios

- Each output includes provenance that traces back to commit and file

- Failure cases are detected and logged with clear error messages

- The pipeline stage can be re-run without producing duplicates

- A short report or CLI output demonstrates the results