RAG Pipeline for Code-Change Context in Code Agents - Real World Projects

Goal: Build a change-aware Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) pipeline that turns raw git history into trustworthy, queryable context for code agents like Codex and Claude. You will learn how to model code changes, chunk and embed them, retrieve the right pieces for a question, and package context so an agent can answer with grounded reasoning. You will also design evaluation loops that detect regressions, measure retrieval quality, and improve the system over time. By the end, you will be able to build a production-ready pipeline that keeps code agents aligned with what actually changed, why it changed, and how to verify it.

Introduction

- What is this topic? A RAG pipeline specialized for code changes is a system that ingests diffs, commits, PRs, and related metadata, then retrieves the most relevant change context for a question and feeds it to a code agent.

- What problem does it solve today? Code agents hallucinate or miss nuance when they do not know the exact changes, rationale, or historical context. A change-aware RAG pipeline grounds their answers in verifiable evidence.

- What will you build across the projects? A full pipeline from git ingestion to retrieval, ranking, context packing, evaluation, and safety filters.

- In scope vs out of scope: In scope is retrieval, indexing, ranking, prompt packaging, and evaluation for code-change context. Out of scope is training new foundation models or building a full IDE.

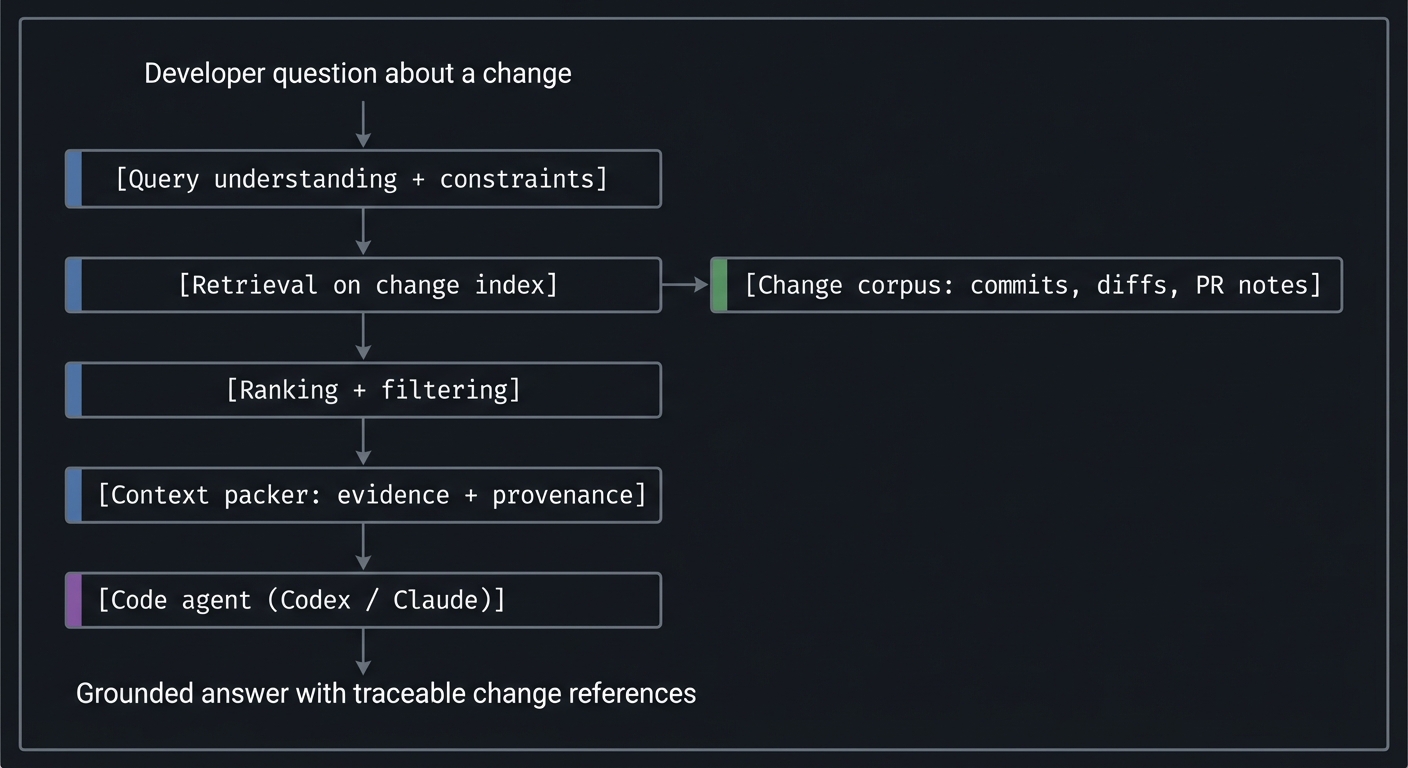

Big picture flow:

Developer question about a change

|

v

[Query understanding + constraints]

|

v

[Retrieval on change index] ----> [Change corpus: commits, diffs, PR notes]

|

v

[Ranking + filtering]

|

v

[Context packer: evidence + provenance]

|

v

[Code agent (Codex / Claude)]

|

v

Grounded answer with traceable change references

How to Use This Guide

- Read the theory primer first, then pick 1-2 learning paths based on your goal (builder, evaluator, or production path).

- After each project, validate outcomes using the Definition of Done and the provided tests and CLI outputs.

- Keep a learning log: for every project, record one failure mode you hit and how you detected it.

Prerequisites & Background Knowledge

Essential Prerequisites (Must Have)

- Comfortable with one scripting language (Python, Go, or JavaScript) and command-line workflows

- Working knowledge of git (commits, branches, diffs, and log inspection)

- Basic understanding of how embeddings and search work at a high level

- Recommended Reading: “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” by Martin Kleppmann - Ch. 1, 2

Helpful But Not Required

- Experience with vector databases or search engines

- Familiarity with software architecture and systems design

- Can learn during: Projects 4, 5, 9

Self-Assessment Questions

- Can you explain the difference between a commit, a diff hunk, and a merge commit?

- If a query is “Why was rate limiting changed last month?”, what evidence would you need to answer it?

- Can you describe how dense (embedding) retrieval differs from keyword search?

Development Environment Setup

Required Tools:

- Git (2.4+)

- A scripting language runtime (Python 3.11+ or Node 20+)

- ripgrep (rg) for fast code search

- A local database (SQLite or similar)

Recommended Tools:

- A local vector search library (FAISS or HNSW-based)

- A diagramming tool for documenting retrieval flows

Testing Your Setup: $ git –version Expected: git version 2.x

$ rg –version Expected: ripgrep 13+ (any recent version is fine)

$ python –version Expected: Python 3.11.x (or use node –version for Node 20+)

Time Investment

- Simple projects: 4-8 hours each

- Moderate projects: 10-20 hours each

- Complex projects: 20-40 hours each

- Total sprint: 2-4 months depending on depth

Important Reality Check

A change-aware RAG pipeline is not just “index code and search”. The hard part is knowing what changed, how it changed, and how to prove that retrieval is correct. Expect false positives, brittle chunking, and evaluation pain at first. That is normal. The goal is to make those failures visible and systematic, not to avoid them.

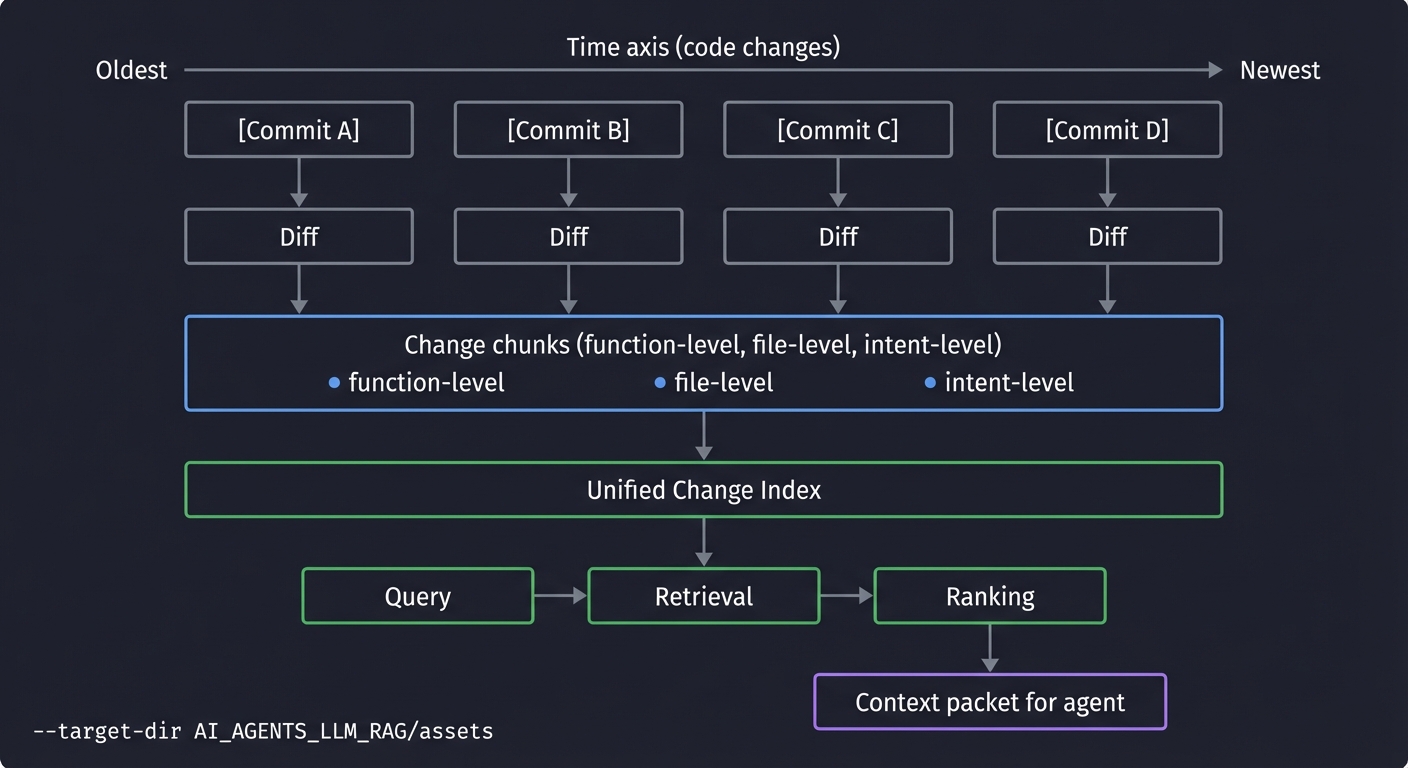

Big Picture / Mental Model

Think of this system as a specialized memory for code agents, where memory is not raw code but evidence of change. The pipeline transforms an evolving codebase into a time-aware, queryable index. When a user asks a question, the system retrieves the most relevant change evidence and packages it into a compact, high-signal context packet that an agent can reason over.

Time axis (code changes)

Oldest --------------------------------------> Newest

[Commit A] [Commit B] [Commit C] [Commit D]

| | | |

Diff Diff Diff Diff

| | | |

Change chunks (function-level, file-level, intent-level)

| | | |

Unified Change Index

|

v

Query -> Retrieval -> Ranking

|

v

Context packet for agent

The invariant: every answer must be grounded in a retrieved change artifact that can be traced back to git or documented rationale. If retrieval is wrong, the answer is wrong. This makes evaluation and provenance first-class concerns.

Theory Primer (Mini-Book)

Chapter 1: RAG Architecture for Code Agents

Fundamentals

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) is the practice of grounding a model’s response in external evidence that can be retrieved on demand. For code agents, that evidence is often not just static documentation or code snapshots, but the history of change: diffs, commit messages, review discussions, release notes, and test outcomes. When an agent answers questions about a change, it is effectively doing forensic reasoning. It must locate the most relevant evidence, compress it into a short context window, and then reason over it without inventing facts. This is where RAG matters. It shifts the agent from “guessing what might be true” to “citing what actually changed.”

A change-aware RAG pipeline has four distinct phases: capture, index, retrieve, and compose. Capture turns raw signals (git commits, diffs, PR metadata) into structured change records. Index converts those records into search-ready artifacts such as vectors, keywords, and structured fields. Retrieval finds candidate evidence based on a user query. Composition packages evidence into a compact context packet that the agent can use. The failure mode is obvious: if retrieval fails, the answer is wrong. This makes retrieval quality and provenance non-negotiable. The most important mindset shift is that the RAG system is a memory system with strict rules about how memory is created, stored, and recalled.

For code agents, context is expensive and bounded. The agent can only “see” a slice of the evidence. This makes packaging critical. You are not dumping raw diffs; you are curating an evidence bundle. The bundle should include a small number of change chunks, each with metadata (commit, author, time, file, rationale), plus a short summary that explains why each chunk is relevant. This introduces a second discipline: evidence design. You are building an interface between a retrieval system and a reasoning system. If the interface is noisy, the agent will be noisy. If it is precise, the agent can be precise.

RAG for code changes also involves temporal reasoning. Some questions care about the most recent change, others about a change window (“when did we first add feature X?”), and others about causal chains (“what change introduced this bug and what fixed it?”). The RAG pipeline must respect time, not just semantic similarity. This means every change record needs a timestamp and a lineage to the main branch history.

Finally, RAG for code agents must cope with ambiguity. A question like “Why was caching removed?” could refer to multiple subsystems. The pipeline must detect ambiguity and either retrieve diverse candidates or ask clarifying questions. This makes query understanding part of retrieval. A robust RAG pipeline includes a query router: it decides which signals to use (diff text, commit message, PR summary, tests) and how to weight them.

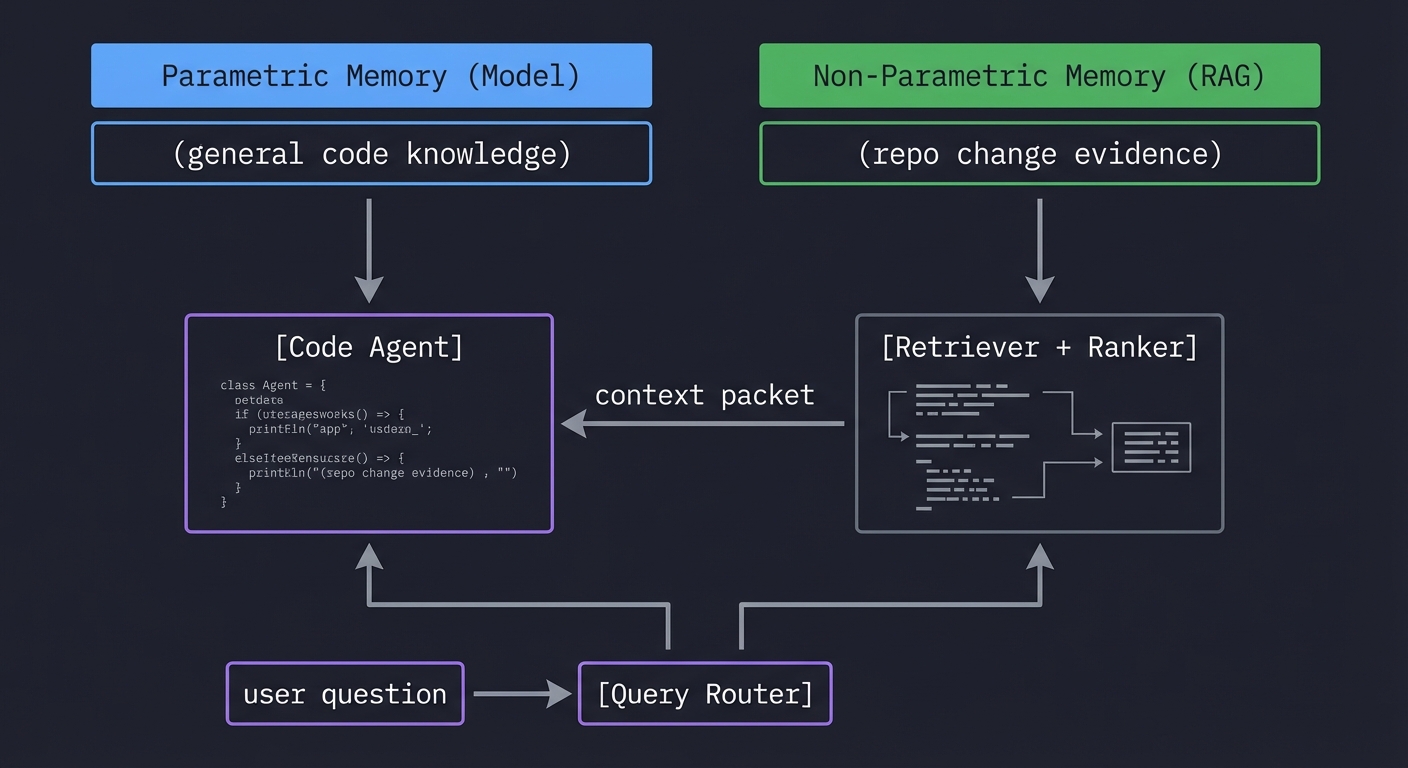

Deep Dive

At a deep level, RAG is a system that mediates between parametric memory (what the model learned during training) and non-parametric memory (what your pipeline stores and retrieves). Code agents already know general programming knowledge, but they do not know your repository’s recent changes unless you provide them. The RAG system is the bridge. For change-aware RAG, your data is extremely high variance: some commits are trivial, some are architectural. Some diffs are noisy (reformatting), some are high-signal (behavior change). A robust architecture treats each change as a first-class entity with its own structure and metadata. That structure then becomes the basis for retrieval and ranking.

A common pitfall is to treat diffs as plain text and embed them wholesale. This usually fails because diffs have a format-specific syntax (“+” and “-“ lines) and often include long blocks of context that are not semantically central. Instead, a change-aware RAG system typically produces change chunks that are smaller, more coherent units: a modified function, a single configuration entry, or a short doc update. Chunking requires understanding the language structure or at least the hunk boundaries. This is not optional. If chunking is wrong, retrieval is wrong. The system should preserve the original diff but also create structured sub-chunks that capture intent.

Another deep issue is intent inference. A commit message often contains rationale that is not present in the diff. A review comment might explain why a change exists. A test log might show that a change fixed a specific failure. These are different evidence sources that must be aligned. The RAG pipeline should attach each change chunk to a bundle of “rationale artifacts”: commit message, PR description, linked issue titles, and test results. When the agent responds, it should cite the rationale artifact, not just the diff. This is how you avoid brittle answers that only describe what changed, not why.

Change-aware RAG also needs a temporal policy. You may want to weight recent changes more heavily when a question is ambiguous, but not always. If the question contains explicit time filters (“last week”, “before 2023-12”), the retrieval system must honor them. If the question is about a long-lived design decision, the retrieval should prefer the original introduction commit. This implies query parsing with time filters and a ranking function that can combine semantic relevance with temporal constraints. This is one of the most powerful differentiators for code-change RAG compared to generic RAG.

RAG systems also need to handle scope. A question like “Why did we remove rate limiting?” could involve only one service, or a cross-service change. The RAG pipeline should use scope signals: file paths, ownership, service tags, or repo modules. If the question mentions a service name or folder, that should narrow retrieval. If not, the pipeline might search across multiple repos and then cluster results by service. This leads to a key architectural principle: retrieval should be modular and composable. Instead of one monolithic retriever, use multiple retrieval channels (diff text, commit messages, issue titles, tests) and then fuse the results.

A strong RAG pipeline is designed with provenance as a data type. Every retrieved chunk must include a stable identifier that maps back to the original change artifact. If you cannot point to the exact commit and file, your system is not trustworthy. This is also crucial for debugging: if the system retrieves the wrong evidence, you must be able to inspect exactly how it got there. Provenance is the backbone of evaluation. It allows you to ask: “Did the retriever pick the right change? Did the ranker mis-order it? Did the context packer drop the crucial line?”

The final deep consideration is context packing. Context is a bottleneck. You cannot dump all relevant changes. You must select, compress, and sometimes summarize. This makes the packer a reasoning component of the system. It should preserve exact evidence (unchanged snippets) while allowing summaries that explain the relationship between changes. It should also provide a disciplined layout so the agent can parse it: each chunk includes file path, commit, time, and diff lines. This is like designing an API. An agent that sees consistent context will behave more consistently. This is why many production RAG systems define an explicit “context packet” schema.

Definitions and key terms

- RAG: Retrieval-Augmented Generation; a method where retrieved evidence is provided to a model before it generates an answer.

- Change artifact: Any evidence item derived from source control, such as a commit, diff hunk, or PR summary.

- Context packet: A structured bundle of retrieved evidence designed to fit within a model’s context window.

- Provenance: Metadata that traces an evidence chunk back to its original source (commit, file, line range).

- Query router: A component that decides which retrieval channels to use based on the question.

Mental model diagram

Parametric Memory (Model) Non-Parametric Memory (RAG)

(general code knowledge) (repo change evidence)

| |

v v

[Code Agent] <--- context packet --- [Retriever + Ranker]

^ ^

| |

user question ----------------> [Query Router]

How it works (step-by-step, invariants, failure modes)

- Capture: ingest commits, diffs, PR metadata, and test outcomes into a structured store.

- Index: create embeddings, keyword indexes, and structured fields for each change chunk.

- Retrieve: generate retrieval queries (semantic + lexical) based on the user question.

- Rank: combine scores (semantic relevance, time, ownership, file paths) to order candidates.

- Compose: assemble a context packet with exact evidence and provenance.

- Respond: the agent answers using only evidence in the packet.

Invariants: every retrieved chunk must be traceable to a commit; every answer must cite at least one chunk.

Failure modes: stale indexes, overly large chunks, noisy diffs, missing rationale, and context overflow that hides the key evidence.

Minimal concrete example (pseudocode)

INPUT: question = "Why did we change the cache TTL last month?"

STEP 1: classify -> change-rationale + time filter

STEP 2: retrieve -> (commit messages + diffs + PR titles)

STEP 3: rank -> prefer last-30-days, config files, service=cache

STEP 4: pack -> 3 chunks + rationale note + provenance

OUTPUT: context packet with commit IDs, file paths, and diff snippets

Common misconceptions

- “If I embed the whole diff, retrieval will work.” (Large diffs are noisy; chunking is essential.)

- “The LLM will figure it out even if retrieval is messy.” (Bad evidence leads to bad answers.)

- “Recency always wins.” (Some questions require historical or root-cause context.)

Check-your-understanding questions

- Why is provenance a non-negotiable part of a change-aware RAG system?

- What is the difference between retrieval and context packing?

- Why is temporal reasoning essential for questions about code changes?

Check-your-understanding answers

- Without provenance, you cannot verify or debug retrieved evidence, and the agent cannot cite sources.

- Retrieval finds candidate evidence; context packing selects and formats evidence so the agent can reason over it.

- Change questions are time-sensitive; the meaning of a change depends on when it occurred and its sequence.

Real-world applications

- Post-incident analysis: “What change introduced this regression?”

- Release notes automation: “Summarize all API changes this sprint.”

- Code review assistance: “Has this pattern been changed elsewhere recently?”

Where you will apply it (projects)

Projects 1-12, especially Projects 1, 4, 5, 7, and 12.

References

- “Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks” (Lewis et al.)

- “RAG Survey” (recent survey papers on RAG architectures)

- “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” by Martin Kleppmann - Ch. 1, 2

- “Fundamentals of Software Architecture” by Richards and Ford - Ch. 2, 5

Key insight

RAG is not just retrieval; it is a memory architecture that makes evidence and provenance first-class.

Summary

A change-aware RAG pipeline is a memory system for code agents. It captures change artifacts, indexes them, retrieves relevant evidence, and composes a context packet that the agent can trust. The quality of answers is bounded by the quality of retrieval and context packing.

Homework / exercises

- Pick a real repository and list three questions that require change history, not just current code.

- For one question, outline the evidence you would want (diffs, commit messages, issues).

- Sketch a context packet layout that would help an agent answer that question.

Solutions

- Examples: “Why was feature X removed?”, “When did we change retry logic?”, “Which commits touched rate limiting?”

- Evidence: commit message, diff hunks, PR summary, related tests.

- Packet layout: header, query summary, ranked chunks with provenance, rationale notes.

Chapter 2: Code-Change Data Model and Provenance

Fundamentals

A change-aware RAG system is only as good as its change model. The change model defines how you represent commits, diffs, and related artifacts in a way that can be retrieved and trusted. If you treat every change as a blob of text, you will lose the meaning of the change. If you ignore metadata, you will lose the timeline. The core idea is to design a change record that is rich enough to answer real questions, but structured enough to index efficiently.

At the most basic level, a change record captures what changed, where it changed, when it changed, and why it changed. “What” is the diff content. “Where” is the file path and optionally the function or symbol. “When” is the commit timestamp and its position in the branch history. “Why” is the commit message, PR description, or linked issue. A good change model stores all four dimensions explicitly, because retrieval questions often target one dimension. For example, “What changed in the caching module?” is about scope and content. “Why did we switch to exponential backoff?” is about rationale. “When did this behavior change?” is about time.

Code changes are not only textual. A diff is a representation of a transformation between two versions of a file. It contains context lines, deleted lines, and added lines. The diff format uses hunk headers to indicate line offsets and counts. If your system does not parse hunks, you cannot map a change chunk back to the right part of a file. This breaks provenance. For code agents, provenance is not optional; it is the backbone of trust. A change model must therefore keep references to commit hashes, file paths, and line ranges, and it must preserve the original diff for verification.

The change model also needs to handle edge cases. Renames, moves, and binary files introduce ambiguity. If a file is renamed, a naive system might treat it as deletion and addition, losing lineage. If a change is large reformatting, the diff may be noisy and meaningless for semantic retrieval. For change-aware RAG, you must detect and tag such cases. This is why the change model includes metadata fields for file operation type (modify, add, delete, rename) and for diff category (behavioral, formatting, dependency, config, docs). These tags become critical signals during retrieval and ranking.

Finally, the change model must be stable over time. It should support incremental ingestion, not full reindexing, and it should maintain backward links to older versions of the file. This makes it possible to answer questions about chains of changes, not just isolated commits. In practice, this means your change record is not just a snapshot; it is a node in a change graph that can be traversed.

Deep Dive

The deep problem in change modeling is that code history is a graph, not a list. Git history forms a directed acyclic graph (DAG) of commits. Each commit has parents, sometimes multiple (merge commits). The same file can diverge on branches and then converge. A change-aware RAG system that only records linear history will get questions wrong. For example, “Why did this change appear in main?” might require walking through a merge commit and its parents. This means your change model should include commit parent relationships and branch labels. Even if you do not fully traverse the DAG during retrieval, the provenance metadata must preserve it so the system can support future queries.

Diffs are another subtle area. A unified diff hunk includes line numbers from both the old and new file plus a block of surrounding context. That context is valuable for retrieval because it anchors the change in the file, but it can also dilute semantic similarity. A robust change model stores hunks separately from their context and marks which lines are additions, deletions, and context. This allows you to compute multiple representations: one that embeds only added lines, one that embeds added and deleted lines, and one that embeds the full hunk. These representations can be used by different retrieval channels. For example, a question about “what was removed” should bias toward deleted lines. A question about “why” may rely more on commit message and PR summary.

Another deep issue is rationale alignment. The commit message may not mention the same terminology as the code. A PR description might use product terms, while code uses internal names. To align these, the change model can include a “rationale text” field that concatenates commit message, PR description, issue title, and labels. This is a separate text field used for retrieval. In parallel, the change model stores a “code change text” field derived from the diff. This separation is crucial for hybrid retrieval because it lets you search rationale and code separately and then fuse results.

You also need to model scope. Scope is not just file path; it is about ownership and module boundaries. A change in services/auth/ might be more relevant to an authentication question than a diff in a generic utility file. The change model should therefore include tags for module, service, or component. These can be extracted from folder conventions, monorepo metadata, or ownership files. Scope tags are used by the query router to filter the candidate set. Without them, retrieval will be noisy in large repos.

Change impact is another dimension. Some changes are trivial refactors, others change runtime behavior. If you can tag changes by impact, you can prioritize them for retrieval. Impact tags can be derived from file type (config vs code), from changed functions (public API vs internal), or from test outcomes. For example, a change that touches a public API should rank higher when a question mentions the API. A change that fails tests should be flagged because it might be related to regressions. This is a key feature for production-grade RAG systems.

To make all this work, you need a stable schema for change records. A minimal schema might include: commit id, parent ids, author, timestamp, branch, files changed, operation type per file, hunk list, rationale text, code text, tags, and external links. But in practice you will also want fields for “confidence” and “quality” (was this change large, was it reviewed, was it reverted?). These fields can be used by the ranker to penalize noisy evidence.

Finally, provenance is more than a hash. It is a path back to truth. When the agent answers a question, the system should be able to point to the exact commit, file, and line range that supports the answer. If the change model loses this link, you cannot validate answers. This is why the change model is the foundation of evaluation. You can only measure retrieval accuracy if you can compare retrieved items to a ground truth. Provenance provides that bridge.

Definitions and key terms

- Commit DAG: The directed acyclic graph of commits in git history.

- Change record: A structured representation of a code change with metadata and provenance.

- Diff hunk: A section of a diff that shows contiguous changes with line offsets.

- Rationale text: Human-facing explanation of why a change exists (commit message, PR description).

- Scope tag: Metadata that identifies the subsystem, module, or service affected by a change.

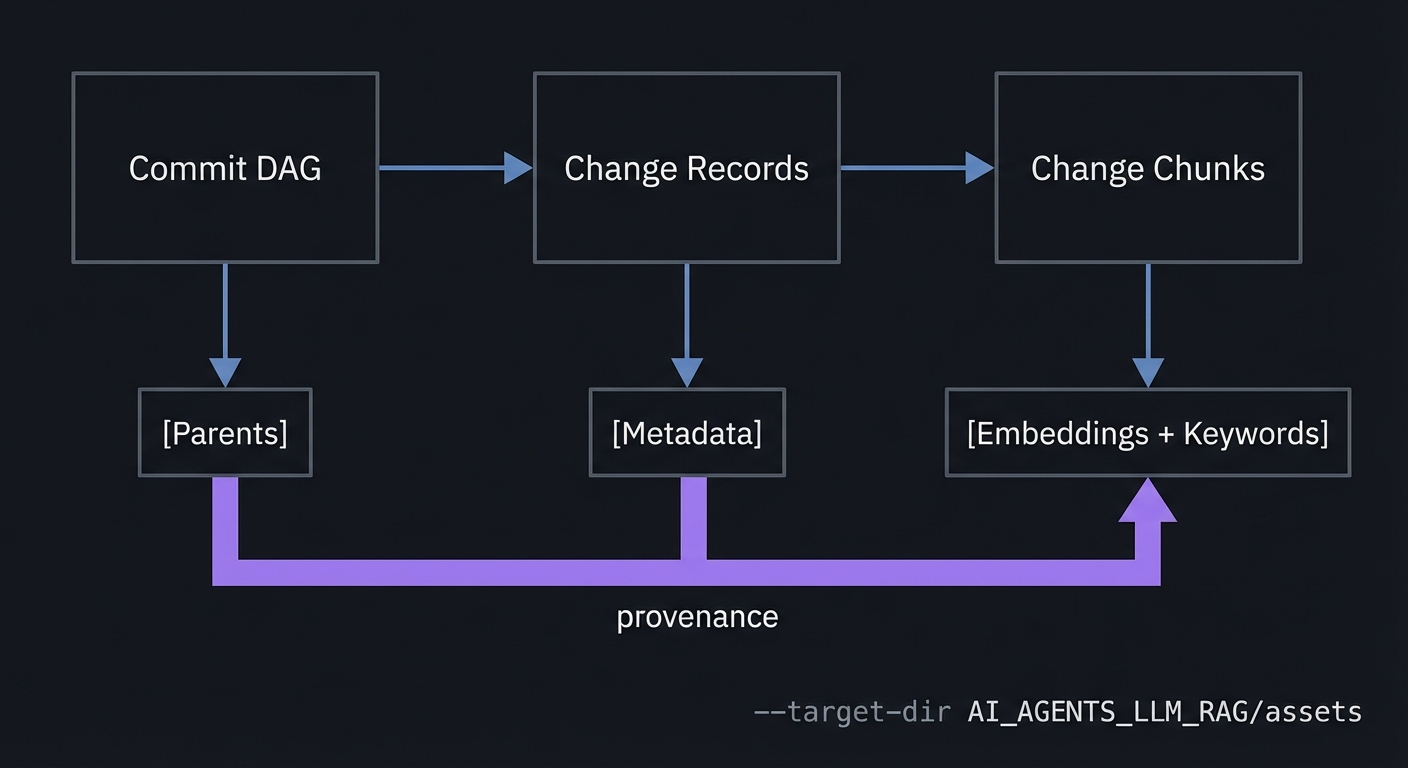

Mental model diagram

Commit DAG -----> Change Records -----> Change Chunks

| | |

v v v

[Parents] [Metadata] [Embeddings + Keywords]

| | |

+-------------- provenance --------------+

How it works (step-by-step, invariants, failure modes)

- Extract commits and parent links from git history.

- Parse diffs into files and hunks, with add/delete/context lines.

- Build change records with metadata (author, time, branch, scope tags).

- Attach rationale text from commit messages and PR descriptions.

- Store provenance pointers to commit id, file path, and line ranges.

Invariants: each change record maps to exactly one commit; each hunk has a stable provenance path.

Failure modes: rename detection errors, noisy formatting changes, missing rationale, and incorrect line mappings.

Minimal concrete example (CLI output)

$ git log --name-status -1

commit abc1234

Author: dev@example.com

Date: 2025-10-12

Reduce cache TTL to prevent stale reads

M services/cache/ttl_config.yaml

M services/cache/cache_manager.py

Common misconceptions

- “Commit messages are optional for retrieval.” (They are often the only source of intent.)

- “File paths are enough to define scope.” (Large repos need richer module tags.)

- “A diff hunk is the same as a function change.” (A hunk can include multiple symbols.)

Check-your-understanding questions

- Why is the commit DAG important for change-aware retrieval?

- What is the difference between code change text and rationale text?

- How do rename operations affect provenance?

Check-your-understanding answers

- It preserves parent relationships and merge context, which matter for history questions.

- Code change text captures what changed in code; rationale text captures why it changed.

- Renames can break lineage unless you record the operation type and original path.

Real-world applications

- Change impact analysis for incidents and regressions

- Automated release note generation

- Compliance audits that require traceability

Where you will apply it (projects)

Projects 1-4 and Projects 8-12.

References

- Git documentation on diff formats and name-status output

- “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” by Martin Kleppmann - Ch. 3, 4

- “Working Effectively with Legacy Code” by Michael Feathers - Ch. 2

Key insight

A change-aware RAG pipeline is only as trustworthy as its change model and provenance chain.

Summary

Change modeling turns raw git history into structured evidence. It must capture diffs, metadata, rationale, and lineage, while preserving provenance. Without this, retrieval cannot be accurate or verifiable.

Homework / exercises

- Choose a recent commit from a repo and write down the minimal change record fields you would store.

- Identify one case where rename detection would matter for retrieval.

- Create a taxonomy of change types (behavioral, config, docs, formatting) for your repo.

Solutions

- Commit id, timestamp, author, file list, diff hunks, rationale text, scope tags, provenance pointers.

- Refactoring a file path while keeping the same functionality; without rename tracking, history looks broken.

- Example: behavioral changes in core logic, config changes, documentation changes, formatting only.

Chapter 3: Chunking, Embeddings, and Index Design for Code Diffs

Fundamentals

Chunking is the act of turning a large change into smaller, semantically meaningful pieces that can be retrieved. For code-change RAG, chunking is not optional. Diffs can be enormous and noisy. If you embed an entire diff, the vector will be dominated by unrelated context lines. If you chunk too small, you lose meaning. The goal is to pick a chunk size that captures a coherent unit of change: a function, a config entry, or a doc section. This makes retrieval precise and interpretable.

Embeddings convert these chunks into vectors that capture semantic similarity. For code changes, you often need two embedding channels: one for code change text (added and removed lines) and one for rationale text (commit messages and PR descriptions). These channels answer different types of questions. A user asking “what changed in the retry logic” is likely best served by code embeddings. A user asking “why did we switch to backoff” is better served by rationale embeddings. A robust RAG pipeline uses multiple embeddings and fuses their results.

Index design matters because your corpus is dynamic. Code changes are constantly added. A static index will quickly become stale. You need a design that supports incremental ingestion, efficient updates, and filtering by metadata (time, repo, service). This implies a combination of data structures: a vector index for semantic search, a keyword index for exact terms, and a metadata store for filtering. For many systems, the simplest design is a hybrid index: vectors in a similarity search library, keyword search in a local search engine, and metadata in a relational store.

Chunking, embeddings, and indexing are a pipeline. If chunking is wrong, embeddings are weak. If embeddings are weak, retrieval is noisy. If indexing is stale, retrieval is wrong. The pipeline must therefore be designed as a unit, with explicit assumptions and evaluation checkpoints at each stage.

Deep Dive

The most subtle part of chunking for code diffs is deciding what semantic unit you care about. A diff hunk is not necessarily a semantic unit; it is a formatting unit. A function change can span multiple hunks, or a single hunk can touch multiple functions. A robust chunker combines multiple signals: hunk boundaries, language syntax, and file structure. For example, you can parse the file into a syntax tree and map diff line ranges to function nodes. If you cannot parse the language, you can approximate by using blank-line separators or indentation patterns. The critical idea is to anchor each chunk in a stable symbol name when possible.

Another issue is mixed changes. Many diffs include both functional changes and formatting changes. If you embed everything, the embedding may reflect the formatting noise rather than the semantic change. One strategy is to separate added and removed lines and remove lines that are only whitespace changes. Another is to compute two representations: a “raw diff” embedding and a “normalized diff” embedding. The raw diff preserves exact evidence; the normalized diff improves semantic retrieval. This dual representation can be used during ranking: semantic match uses normalized, while context packing uses raw.

Embeddings for code changes are also tricky because the change is not just code; it is a transformation. Standard code embeddings are trained on static code, not diffs. This means a diff embedding might not capture the direction of change. A workaround is to embed “before” and “after” states separately, then store a combined representation that includes both. Another approach is to embed a textual summary of the change (“Removed retry loop, added exponential backoff”) produced during ingestion. This summary can be created by rules or by a small model and then stored in the change record. The summary is not the evidence itself; it is a retrieval aid.

Index design must handle growth and updates. Each new commit adds change chunks. You can either rebuild the index periodically or incrementally insert new vectors. Incremental inserts are faster but can degrade recall if the index is not optimized. This is why many systems have a dual-index approach: a “hot” incremental index for recent changes and a “cold” optimized index for older history. Retrieval queries search both and then merge results. This design also supports recency weighting naturally.

Metadata filtering is critical for large repositories. Your vector index alone cannot handle queries like “changes in the payments service” unless you filter by tags. Therefore, each vector entry must carry metadata fields (repo, service, file path, time). The retrieval system then applies filters before or after vector search. This is not just a performance optimization; it is a correctness feature. Without filters, a similar change in another service might rank higher than the relevant change in the target service.

Choosing an indexing algorithm is another deep issue. HNSW-based indexes are often used for in-memory retrieval, while FAISS offers a range of algorithms optimized for scale. The right choice depends on corpus size and latency goals. For a single repo with tens of thousands of change chunks, a simple HNSW index might be enough. For multi-repo corpora with millions of chunks, you need more aggressive indexing and possibly sharding. The key is to be explicit about your scale assumptions and test retrieval latency under realistic workloads.

Finally, chunking and indexing must support evaluation. You cannot improve retrieval if you cannot measure it. This means your ingestion pipeline should log chunk statistics: average size, token count, number of chunks per commit, and ratio of code vs rationale text. These metrics help you tune chunking. If average chunk size is too large, retrieval will be noisy. If it is too small, you will retrieve many tiny fragments that do not answer questions. The pipeline must be instrumented.

Definitions and key terms

- Chunking: Splitting a change into semantically meaningful parts for retrieval.

- Embedding: Vector representation of a text or code chunk.

- Hybrid index: Combination of vector search, keyword search, and metadata filtering.

- HNSW: Hierarchical Navigable Small World graph for approximate nearest neighbor search.

- FAISS: A similarity search library optimized for vector retrieval at scale.

Mental model diagram

Raw diff + metadata

|

v

[Chunker] ---> [Chunk A] [Chunk B] [Chunk C]

|

v

[Embeddings] (code + rationale)

|

v

[Vector Index + Keyword Index + Metadata Store]

How it works (step-by-step, invariants, failure modes)

- Parse diffs into hunks and map hunks to semantic units.

- Generate change chunks with stable identifiers.

- Create embeddings for code text and rationale text.

- Insert vectors into the index with metadata tags.

- Maintain incremental updates and periodic compaction.

Invariants: each chunk has a stable id and provenance; embeddings are computed with a fixed model version.

Failure modes: oversized chunks, whitespace noise, stale indexes, missing metadata tags.

Minimal concrete example (pseudocode)

INPUT: diff hunk + file path

STEP 1: map to function boundaries (if possible)

STEP 2: create chunk: {symbol, added_lines, removed_lines}

STEP 3: embed added_lines and rationale text

STEP 4: store vectors with metadata {repo, path, time}

OUTPUT: indexed chunk id

Common misconceptions

- “Bigger chunks give better answers.” (They reduce precision and waste context.)

- “One embedding is enough.” (Code change queries often need separate code and rationale channels.)

- “Indexing is just a storage detail.” (Index structure determines retrieval quality and latency.)

Check-your-understanding questions

- Why is diff chunking different from normal text chunking?

- What problem does a dual-index (hot and cold) design solve?

- Why keep both raw and normalized diff representations?

Check-your-understanding answers

- Diff chunking must preserve change semantics and provenance, not just token length.

- It allows fast updates for recent changes while keeping older history optimized.

- Raw diffs preserve evidence; normalized diffs improve semantic retrieval.

Real-world applications

- Fast retrieval of configuration changes for incident review

- Change summaries for release management

- Audit trails for compliance questions

Where you will apply it (projects)

Projects 2-6 and Projects 11-12.

References

- FAISS paper on similarity search at scale

- HNSW paper by Malkov and Yashunin

- CodeSearchNet dataset and paper

- “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” by Martin Kleppmann - Ch. 5, 6

Key insight

Chunking defines the retrieval unit; everything else depends on it.

Summary

Chunking, embeddings, and index design form the retrieval backbone. A robust system uses multiple embedding channels, metadata filters, and incremental indexing, while preserving provenance and measuring chunk quality.

Homework / exercises

- Take a large diff and propose three different chunking strategies.

- Define what metadata tags you need for your repo to make retrieval precise.

- Estimate how many change chunks your repo will produce per month.

Solutions

- Strategy examples: function-level chunks, hunk-level chunks, semantic sections by comment headers.

- Metadata: repo name, service, file path, language, timestamp, author, change type.

- Multiply average commits per month by average hunks per commit; add a buffer for spikes.

Chapter 4: Retrieval and Ranking for Change-Aware Queries

Fundamentals

Retrieval is the act of finding candidate evidence given a question. Ranking is the act of ordering those candidates so the most relevant ones are seen first. In a change-aware RAG pipeline, retrieval must consider not only semantic similarity but also time, scope, and rationale. A question like “Why did we reduce cache TTL?” is not just a similarity search over code; it is a search over change intent, configuration files, and recent timelines. This means retrieval must be hybrid by default.

Hybrid retrieval combines lexical search (exact keywords) with dense retrieval (semantic similarity). Lexical search is strong when the query contains specific terms like file names or function identifiers. Dense retrieval is strong when the query is phrased in natural language. For code change RAG, you often need both because users will ask in a mix of natural language and code terms. A hybrid approach gives you the best of both worlds. The retrieval system should produce a candidate set from multiple channels and then fuse the results.

Ranking is where you encode your domain assumptions. Should recent changes rank higher? Should changes in a specific service take priority? Should reverted changes be penalized? These are ranking decisions. A good ranker is not just a similarity function; it is a policy. It enforces constraints and preference rules. If your ranker is naive, the agent will be inconsistent and untrustworthy. If your ranker is thoughtful, the agent will be grounded and predictable.

A key idea is to separate retrieval signals from ranking policy. Retrieval signals are scores: semantic similarity, keyword match, recency score, ownership match. Ranking policy combines these scores into a final ordering. The benefit of separation is debuggability. If a result is wrong, you can see which signal misled the system. This is essential for building a system that improves over time.

Deep Dive

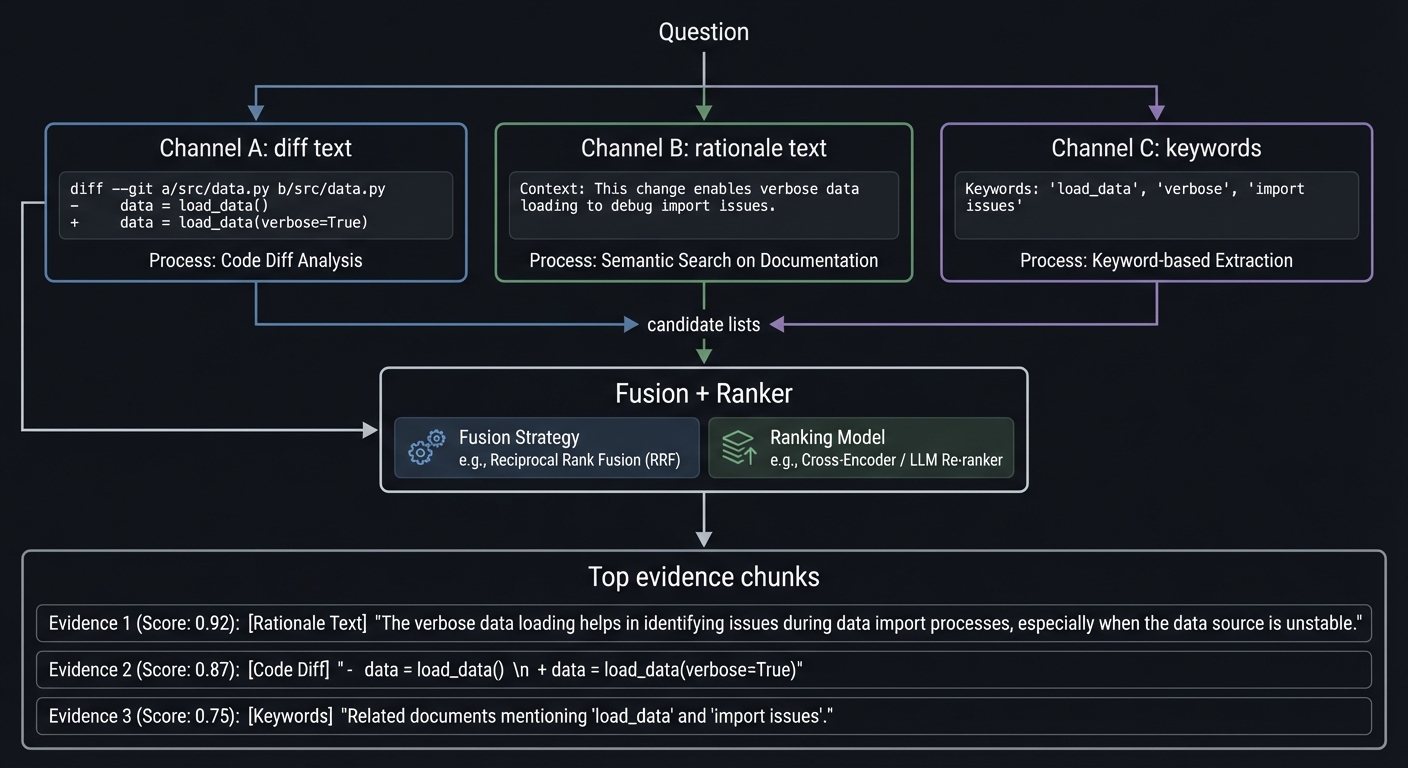

In practice, retrieval for code changes often uses at least three channels: diff text, rationale text, and metadata filters. A query like “Why did we remove the retry loop?” might retrieve matches from diff text (“remove retry loop”) and from rationale text (“simplify retries for latency reasons”). The retriever should run separate searches on each channel, then merge the results. This is where fusion methods like Reciprocal Rank Fusion (RRF) are valuable: they combine multiple ranked lists without requiring score calibration.

Dense retrieval introduces a subtle risk: semantic drift. If embeddings are trained on general text or code, they might consider two unrelated changes “similar” because of shared vocabulary. For example, “cache” could mean data caching in one service and HTTP caching headers in another. This is where metadata filters and scope tags protect you. You can constrain retrieval to relevant services or directories when the query implies scope. If the query has no explicit scope, you can let retrieval broaden but then cluster results by scope and surface the top clusters.

Lexical retrieval (e.g., BM25) is critical for exact tokens. Code change questions often include exact identifiers: function names, config keys, and error codes. Dense retrieval sometimes fails to match these precisely. A hybrid strategy ensures that exact matches are not lost. In ranking, you can boost lexical matches when they are rare or when they match a symbol name. This is a form of “symbol-aware ranking” that improves correctness for code agents.

Another deep issue is time-aware ranking. For change queries, time is a first-class signal. But not all questions prefer recency. Some questions seek the origin of a feature, others seek the most recent modification. This means the ranker must infer time intent. You can detect time intent by parsing phrases like “last week” or “since release X” and by recognizing verbs like “introduced” or “removed.” When time intent is unclear, you can use a gentle time decay that favors recent changes without suppressing older but highly relevant changes.

Reranking is often the difference between a system that “sort of works” and one that is reliable. A reranker is a secondary model or heuristic that reorders the top candidates by deeper understanding. For example, a reranker might compare the question to the combined diff and rationale text, or it might check whether the diff actually touches the symbol named in the question. Reranking can also filter out false positives. For instance, if the question mentions “TTL” and the diff only changes documentation, a reranker can demote it.

Ranking also needs to handle negative evidence. If a change is reverted, it might still be relevant for historical questions but should be treated carefully for current behavior. This implies a negative flag in the change model and a policy decision: do you allow reverted changes in the candidate set, and if so, how do you label them? Many systems choose to include them but clearly mark them as reverted. This helps agents answer questions like “Why did we roll back the retry change?”

Finally, retrieval must be evaluated. You need relevance judgments: which changes are actually relevant to a question. These judgments can come from human labeling or from synthetic generation (questions derived from commit messages). Ranking quality should be measured with metrics like MRR and nDCG. The goal is not to maximize one metric, but to balance precision (correctness) with recall (coverage). For code agents, precision is often more important because wrong evidence can mislead the agent. But recall matters for questions that require multi-change context. This is why evaluation is a separate chapter and a separate project later in this guide.

Definitions and key terms

- BM25: A keyword-based ranking function used in information retrieval.

- Dense retrieval: Retrieval based on vector similarity of embeddings.

- RRF: Reciprocal Rank Fusion, a method for combining ranked lists.

- Reranking: A second-stage reordering of top candidates using deeper signals.

- Time decay: A scoring function that reduces relevance as evidence becomes older.

Mental model diagram

Question

|

v

[Channel A: diff text] [Channel B: rationale text] [Channel C: keywords]

\ | /

\ | /

+---- candidate lists +-----> [Fusion + Ranker]

|

v

Top evidence chunks

How it works (step-by-step, invariants, failure modes)

- Parse query for scope, time intent, and identifiers.

- Run retrieval across multiple channels.

- Merge candidates with fusion (e.g., RRF).

- Apply metadata filters and time-aware ranking.

- Rerank top results for precision.

Invariants: ranking must be reproducible; time filters must be respected when explicit.

Failure modes: semantic drift, over-weighted recency, keyword misses, and noisy diffs.

Minimal concrete example (pseudocode)

INPUT: question = "When did we remove the retry loop?"

STEP 1: detect time intent = origin of change

STEP 2: retrieve in rationale + diff channels

STEP 3: rank with boost for "remove" and history depth

STEP 4: return top 3 commits with dates

OUTPUT: evidence list ordered by earliest matching removal

Common misconceptions

- “Dense retrieval replaces keyword search.” (It does not for code identifiers.)

- “Recency is always best.” (Origin questions need older evidence.)

- “Ranking is just sorting by similarity.” (Ranking is a policy with domain rules.)

Check-your-understanding questions

- Why is hybrid retrieval essential for code-change questions?

- What does RRF solve compared to a single scoring system?

- How do you handle queries that ask for the origin of a change?

Check-your-understanding answers

- It captures both exact identifiers and semantic meaning in natural language.

- It fuses multiple ranked lists without needing score calibration.

- Use time intent detection and prioritize older, first-introduction commits.

Real-world applications

- Root cause analysis for regressions

- Audit searches for compliance-driven change tracking

- Migration tracking across releases

Where you will apply it (projects)

Projects 5-7 and Projects 9-12.

References

- BM25 and information retrieval references

- RRF paper (Cormack, Clarke, and Buettcher)

- nDCG paper (Jarvelin and Kekalainen)

Key insight

Retrieval quality is not just similarity; it is similarity constrained by time, scope, and intent.

Summary

Change-aware retrieval uses hybrid channels, fusion, and time-aware ranking to deliver precise evidence. It treats ranking as a policy decision, not just a math function, and it requires rigorous evaluation.

Homework / exercises

- Write three example queries and decide which retrieval channel should dominate.

- Propose a simple ranking formula that combines semantic score and recency.

- Identify a scenario where reranking would remove a false positive.

Solutions

- Example: “config key” -> keyword; “why changed” -> rationale; “similar changes” -> dense retrieval.

- Score = (0.6 * semantic) + (0.3 * keyword) + (0.1 * time decay).

- A diff that mentions the same word but only in comments; reranker demotes it.

Chapter 5: Context Assembly, Prompt Orchestration, and Tooling Contracts

Fundamentals

Retrieval alone does not produce good answers. The retrieved evidence must be assembled into a context packet that a code agent can reliably interpret. This is the role of context assembly and prompt orchestration. A context packet is a structured, compact representation of evidence. It includes the question, the most relevant change chunks, and clear provenance for each chunk. Prompt orchestration defines how this packet is presented to the agent and what constraints the agent must follow. Without consistent structure, the agent will treat evidence as noise, or it will overfit to irrelevant details.

Context assembly is a compression task. The total evidence retrieved might be far larger than the model’s context window. The packer must choose what to include and what to summarize. The safest strategy is to include exact evidence for the top few chunks and summaries for lower-ranked chunks. Exact evidence is necessary for trust. Summaries are useful for recall. This is why the context packet often has two tiers: a “high-trust” tier with direct diff snippets and a “support” tier with summaries or metadata.

Prompt orchestration is the contract between your RAG pipeline and the agent. It must instruct the agent to answer only using the provided evidence and to call out uncertainty. It should also enforce a response format that includes citations to the evidence chunks. This contract is the difference between a grounded answer and a hallucination. The best prompt contracts are short, unambiguous, and consistent across interactions. They remind the agent that evidence is mandatory and that missing evidence should trigger a clarifying question.

For code changes, context assembly has an extra challenge: the evidence often includes additions and deletions. An agent might misinterpret a deleted line as current behavior. The context packet should therefore label lines clearly as “added” or “removed” and include timestamps. It should also include the commit message or rationale text to prevent the agent from guessing the reason for the change. In short, context assembly must make the change direction and intent explicit.

Deep Dive

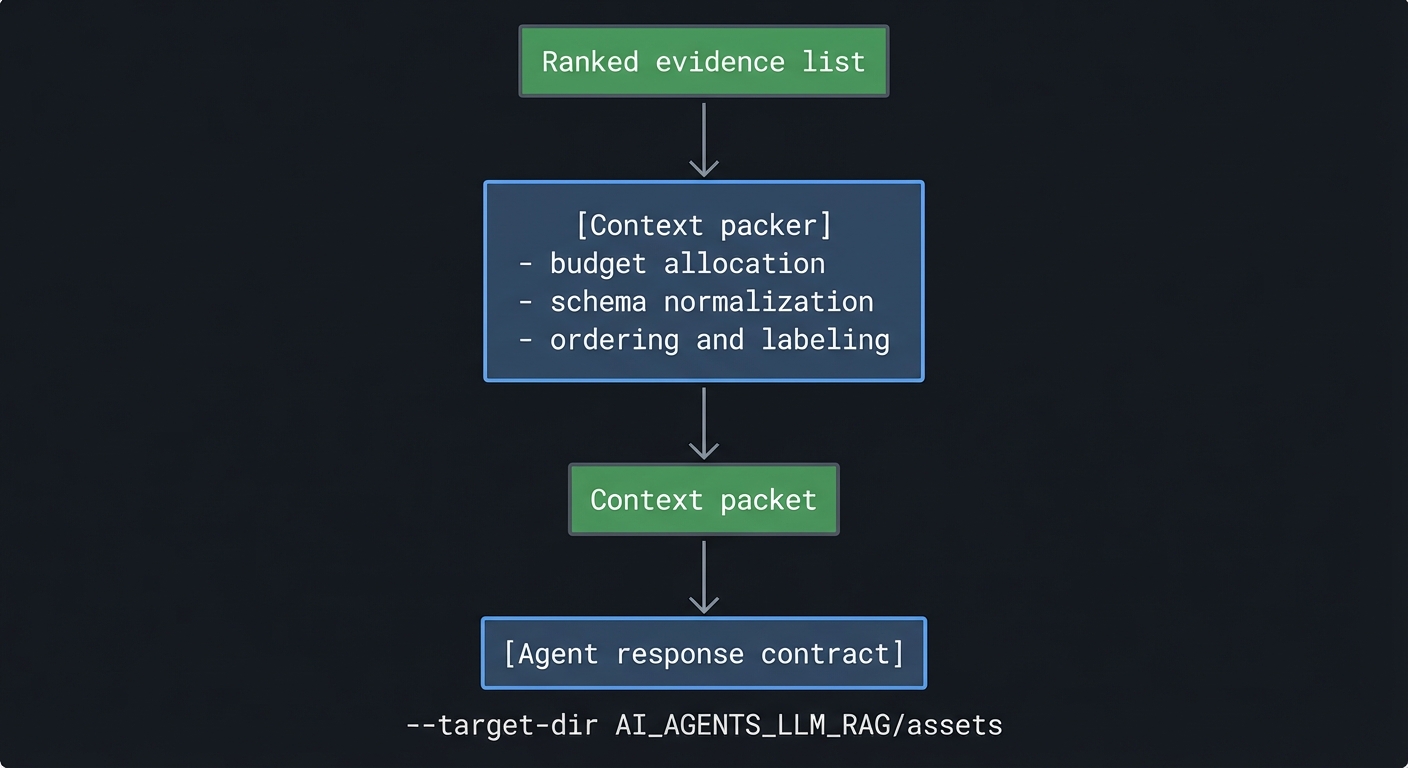

Context assembly is an optimization problem with multiple constraints: evidence relevance, provenance, token budget, and interpretability. The packer must solve this under uncertainty. The retrieval system provides a ranked list, but ranking scores are not perfect. If the packer blindly takes the top N items, it might miss an essential supporting change. A more robust strategy is to allocate budget across categories: for example, reserve 60 percent for top-ranked chunks, 20 percent for alternative hypotheses, and 20 percent for metadata summaries. This gives the agent a more balanced evidence set.

The packer should also normalize evidence into a consistent schema. For example, each chunk can be represented as:

- Chunk ID

- Commit ID

- Timestamp

- File path

- Change type (add, delete, modify, rename)

- Evidence lines (with line-type labels)

- Rationale text (commit or PR summary)

- Relevance score (optional)

This schema is the backbone of a tooling contract. If the agent sees the same schema every time, it can parse it reliably. In practice, the packer should be deterministic so that the same evidence set yields the same packet. This supports reproducibility and debugging.

Prompt orchestration must define both behavioral rules and output format. Behavioral rules include: “Only use evidence provided,” “If evidence is insufficient, ask a clarifying question,” and “Call out contradictions.” Output format defines how the agent should respond, such as: “Answer” section, “Evidence” section with chunk ids, and “Uncertainty” section. This structure is crucial for evaluating agent performance because it allows you to compare answers to evidence. Without a structure, you cannot automate evaluation.

A subtle but important issue is evidence ordering. The agent tends to overweight early context. If you place lower-quality evidence at the top, the agent may anchor on it. Therefore, the packer should order evidence by relevance and confidence, and it should clearly separate primary evidence from secondary. It should also annotate when evidence is conflicting. This helps the agent reason about uncertainty instead of guessing.

Another deep consideration is context window economics. Different models have different context limits, and these limits change over time. A robust pipeline should not hardcode a single token budget. Instead, the packer should be configurable by model type and include a preflight step that estimates token usage. If the packet exceeds the budget, the packer should drop the lowest-value evidence or compress it further. This is a constant tradeoff between recall and precision. In practice, most systems prefer precision for code changes because incorrect evidence can cause wrong decisions.

For multi-turn conversations, context assembly becomes stateful. The system must know what evidence has already been shown to the agent and avoid repeating it. It should also update the evidence set if the user changes the question or scope. This requires a session store that tracks prior packets. If a user asks a follow-up question, the packer can reuse previous evidence and add incremental pieces. This is a form of conversational retrieval, where the query is updated with conversation context.

Finally, context assembly should anticipate downstream actions. A code agent might take actions like generating a patch, writing tests, or explaining a behavior. The packer should include evidence that supports those actions. For example, if the user wants to revert a change, the packet should include the original diff and the related tests. If the user asks for a rationale, the packet should emphasize the commit message and PR discussion. This means the packer should be action-aware, not just query-aware.

Definitions and key terms

- Context packet: A structured bundle of evidence that fits into the model context.

- Prompt contract: The explicit rules the agent must follow when using evidence.

- Evidence tiering: Separating top evidence from secondary summaries.

- Token budget: The maximum context size allowed by the target model.

- Action-aware packing: Selecting evidence based on the action the agent must take.

Mental model diagram

Ranked evidence list

|

v

[Context packer]

- budget allocation

- schema normalization

- ordering and labeling

|

v

Context packet

|

v

[Agent response contract]

How it works (step-by-step, invariants, failure modes)

- Determine token budget based on target model.

- Select top evidence chunks and allocate tiers.

- Normalize evidence into the packet schema.

- Insert prompt contract and output format rules.

- Deliver packet to the agent.

Invariants: every chunk is labeled with provenance and change direction; evidence ordering is deterministic.

Failure modes: context overflow, unlabeled deletions, inconsistent schema, and prompt drift.

Minimal concrete example (structured outline)

CONTEXT PACKET

- Question: "Why was caching removed?"

- Primary Evidence:

* Chunk A (commit, file, add/remove lines)

* Chunk B (commit, rationale text)

- Secondary Evidence:

* Chunk C (earlier related change)

- Contract:

* Answer only using evidence above

* If unsure, ask for scope or timeframe

OUTPUT FORMAT

- Answer

- Evidence (chunk IDs)

- Uncertainty

Common misconceptions

- “More context always helps.” (Too much context hides the signal.)

- “Prompting is a one-time setup.” (Prompt contracts need versioning and testing.)

- “The agent will interpret diff lines correctly.” (You must label additions and deletions.)

Check-your-understanding questions

- Why is evidence tiering useful?

- What should a prompt contract contain for change-aware RAG?

- How does evidence ordering affect agent behavior?

Check-your-understanding answers

- It balances precision and recall under limited context budgets.

- Rules about evidence use, uncertainty handling, and output structure.

- The agent anchors on early evidence, so ordering shapes its interpretation.

Real-world applications

- Code review chat assistants that cite exact diffs

- Incident response assistants that summarize recent changes

- Release management assistants that explain rationale

Where you will apply it (projects)

Projects 6-8 and Project 12.

References

- Prompting best practices for grounded LLMs

- RAG system design guides

- “Clean Architecture” by Robert C. Martin - Ch. 1, 22

Key insight

Context assembly is the interface between retrieval and reasoning; if the interface is weak, the agent is weak.

Summary

Context assembly and prompt orchestration ensure retrieved evidence is usable, traceable, and constrained. A strong context packet design and contract prevent hallucinations and make evaluation possible.

Homework / exercises

- Design a context packet schema for your repo and list the required fields.

- Write a short prompt contract that enforces evidence-only answers.

- Plan how you would adapt the packet for a smaller context window.

Solutions

- Fields: question, chunk id, commit id, file path, diff lines, rationale text, timestamp.

- Contract: “Use only provided evidence, cite chunk IDs, ask clarifying questions if evidence is insufficient.”

- Reduce to top 2 chunks, summarize secondary evidence, remove low-value metadata.

Chapter 6: Evaluation, Observability, and Safety for Change-Aware RAG

Fundamentals

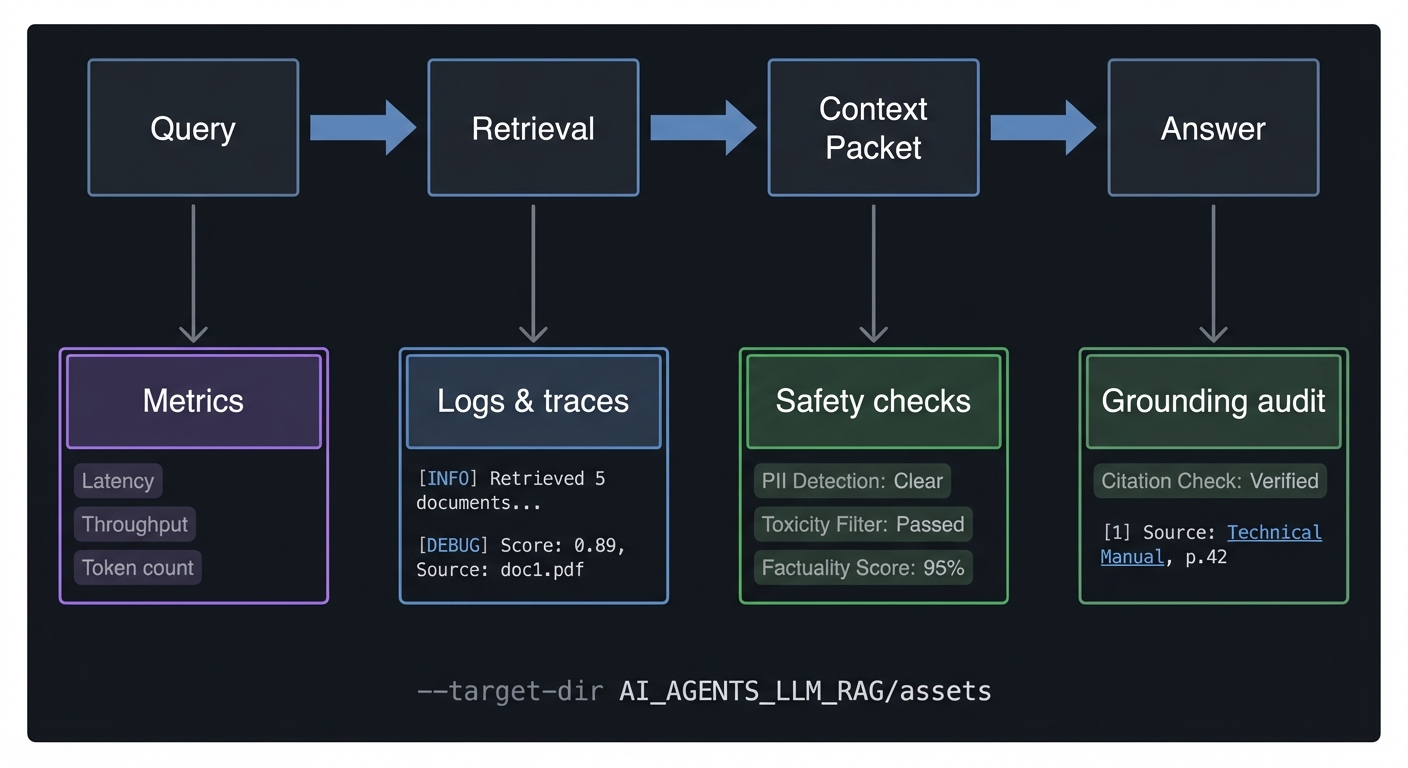

A RAG pipeline without evaluation is a guessing machine. Because retrieval is probabilistic, you must measure whether the system is returning the right evidence, and whether the agent is using that evidence correctly. Evaluation has two layers: retrieval evaluation (did we retrieve the right change chunks?) and answer evaluation (did the agent produce a correct, grounded response?). For change-aware systems, retrieval quality is usually the dominant factor. If the wrong diff is retrieved, the answer will be wrong regardless of how good the model is.

Observability is how you make failures visible. A production pipeline should log every retrieval query, the candidate set, the final context packet, and the agent’s response. These logs allow you to audit errors and understand whether they were caused by retrieval, ranking, or context packing. Observability also enables regression testing: you can replay old queries and see if retrieval quality improved or regressed.

Safety is the third pillar. Code changes often include sensitive data such as API keys, credentials, or internal system names. A change-aware RAG pipeline must include redaction and policy checks before evidence is shown to an agent. The safety layer should also enforce access control: a user should only retrieve changes they are allowed to see. This is especially important when you have multiple repositories or teams. Safety is not optional; it is part of system correctness.

Deep Dive

Evaluation starts with a dataset. You need a set of questions and the known relevant change chunks for each question. These can be collected in multiple ways: manual labeling by engineers, synthetic question generation from commit messages, or mining issue trackers. The dataset should cover different query types: “why” questions, “when” questions, “what changed” questions, and “where” questions. It should also include edge cases, such as questions about reverted changes or cross-service changes. Without coverage, your evaluation will mislead you.

Retrieval metrics are standard in information retrieval. Precision measures how many retrieved chunks are relevant. Recall measures how many relevant chunks were retrieved. Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR) measures how high the first relevant result appears. nDCG measures ranking quality across multiple relevant items. For change-aware RAG, you often care about precision at top K because the agent only sees a few chunks. This is why P@3 or P@5 is often more useful than overall recall. However, recall matters when questions require multiple change chunks to answer properly. A balanced evaluation includes both.

Answer evaluation is harder. You need to assess whether the agent’s response is grounded in evidence and whether it is correct. A common approach is to require the agent to cite chunk IDs. You can then verify whether those chunks contain the necessary evidence. If the agent cites a chunk that does not support the answer, that is a grounding failure. You can also evaluate whether the answer contains unsupported claims. This can be done manually or with heuristics such as checking for references to evidence fields.

Observability requires structured logging. Every query should produce a trace: query text, parsed intent, retrieval candidates with scores, final context packet, and response. You can then compute online metrics, such as retrieval latency, index freshness, and error rates. For example, you can detect if a new deployment causes a drop in MRR or an increase in “no answer” responses. This allows you to roll back quickly.

Safety is a multi-layered problem. First, you need redaction. This can be rule-based (detect keys, tokens, secrets) and can be applied during ingestion so sensitive lines are never stored. Second, you need access control. If your system supports multiple users or teams, retrieval must enforce permissions. This can be done by tagging change records with visibility scopes and filtering during retrieval. Third, you need output safety. Even if the evidence is safe, the agent might summarize it in a way that reveals sensitive details. This is why the prompt contract should include confidentiality rules and why output should be checked before display.

A critical but often ignored area is evaluation drift. As the repository evolves, the questions and relevant changes shift. Your evaluation dataset must be refreshed periodically. Otherwise, you optimize for outdated questions. This is why observability should include detection of “new query types” and data drift in change patterns. If you suddenly see many queries about a new subsystem, you should add those to the evaluation set.

Another important practice is counterfactual testing. You can test what happens when retrieval fails: feed the agent incorrect or incomplete evidence and see how it responds. This helps you design better prompt contracts and fallback behaviors. For example, if evidence is missing, the system should respond with a clarifying question rather than a guess. This is part of safety and trust.

Finally, evaluation and safety are not one-time tasks; they are continuous. A robust pipeline has automated regression tests, monitoring dashboards, and incident response playbooks. It treats retrieval errors as production incidents because they directly affect decision-making. In a change-aware system, wrong evidence can lead to incorrect code changes or faulty reasoning about past behavior. This is why evaluation and safety must be baked in from day one.

Definitions and key terms

- Precision / Recall: Measures of retrieval accuracy and coverage.

- MRR: Mean Reciprocal Rank, focused on the first relevant result.

- nDCG: Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain, evaluating ranked lists.

- Grounding failure: An answer that is not supported by the retrieved evidence.

- Redaction: Removing or masking sensitive data before storage or display.

Mental model diagram

Query -> Retrieval -> Context Packet -> Answer

| | | |

v v v v

Metrics Logs & traces Safety checks Grounding audit

How it works (step-by-step, invariants, failure modes)

- Build a labeled evaluation set of questions and relevant change chunks.

- Run retrieval and compute metrics (P@K, MRR, nDCG).

- Evaluate answers for grounding and correctness.

- Log every query and response for observability.

- Apply redaction and access control before output.

Invariants: every answer is traceable to evidence; sensitive data is never returned.

Failure modes: stale evaluation sets, unlogged queries, silent retrieval regressions, leaked secrets.

Minimal concrete example (CLI output)

$ ragc eval --set change_questions_v1

P@3: 0.72

MRR: 0.61

nDCG@5: 0.68

Grounding violations: 3

Common misconceptions

- “If retrieval is good, safety is automatic.” (Safety requires explicit controls.)

- “One evaluation set is enough.” (Change patterns drift over time.)

- “Answer quality is subjective.” (Grounding can be measured objectively.)

Check-your-understanding questions

- Why are retrieval metrics more critical than generation metrics in change-aware RAG?

- What is a grounding failure and how do you detect it?

- Why should evaluation datasets be refreshed regularly?

Check-your-understanding answers

- Wrong evidence guarantees wrong answers; generation cannot fix missing evidence.

- The answer cites evidence that does not support the claim or uses unsupported facts.

- Codebases and query patterns evolve, so old evaluation sets become stale.

Real-world applications

- Regression testing for RAG systems in production

- Security compliance for code-change visibility

- Quality gates for agent-assisted code review

Where you will apply it (projects)

Projects 9-12, and it underpins all other projects.

References

- Information retrieval evaluation literature (MRR, nDCG)

- Security best practices for handling secrets

- “Release It!” by Michael T. Nygard - Ch. 4, 17

Key insight

Evaluation and safety are not extras; they define whether a RAG pipeline is trustworthy.

Summary

A change-aware RAG system must measure retrieval quality, audit grounding, and enforce safety. Observability provides the feedback loop that makes the system reliable over time.

Homework / exercises

- Design a small evaluation set of 10 questions from your repo’s recent changes.

- Propose a logging schema that captures the full retrieval trace.

- List five types of sensitive data that must be redacted before retrieval.

Solutions

- Include questions about why, what, when, and where changes happened.

- Log fields: query, parsed intent, candidate ids with scores, final packet ids, response.

- API keys, passwords, tokens, secrets in env files, internal hostnames.

Glossary

- Change chunk: A semantically meaningful unit of a code change used for retrieval.

- Context packet: The structured evidence bundle provided to the agent.

- Evidence tier: Priority grouping of retrieved chunks (primary vs secondary).

- Provenance chain: The mapping from a chunk back to commit, file, and line range.

- Time intent: Whether a query wants the origin, most recent, or range of changes.

- Hybrid retrieval: Combining lexical and dense retrieval.

- Reranker: A second-stage component that refines candidate ordering.

- Grounding: Ensuring answers are supported by retrieved evidence.

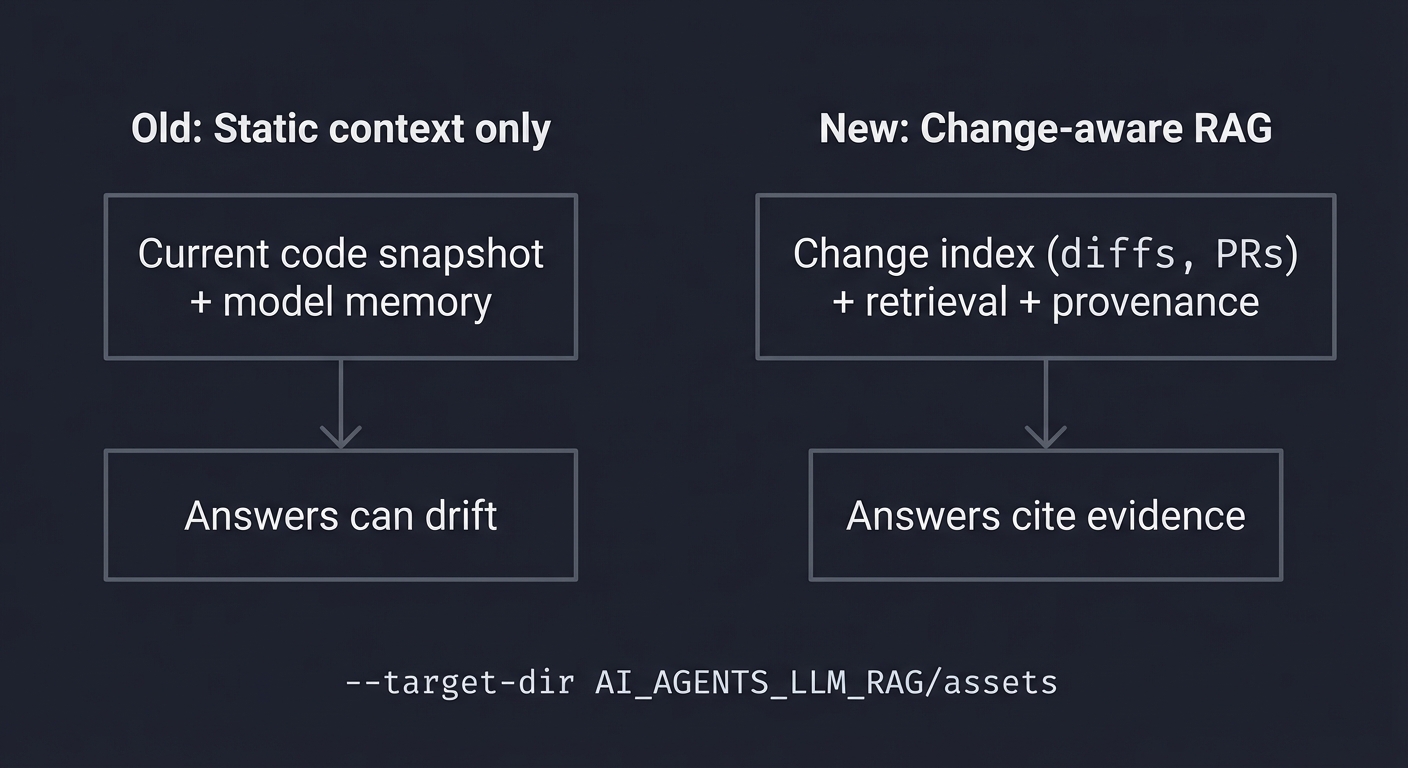

Why Change-Aware RAG for Code Agents Matters

Modern codebases are too large and too dynamic for a model to reason about without precise evidence. Code agents are increasingly used for analysis, review, and debugging, but their accuracy depends on the evidence you provide. A change-aware RAG pipeline turns raw history into verifiable context, reducing guesswork and improving trust.

Modern motivation and real-world use cases:

- Incident response: “Which change introduced the regression?”

- Code review: “Has this logic been changed elsewhere recently?”

- Release management: “Summarize all API changes this sprint.”

Real-world statistics and impact (include year and source):

- Stack Overflow Developer Survey 2025 (AI section): 84% of respondents use or plan to use AI tools, and 51% of professional developers use AI tools daily.

- Stack Overflow Developer Survey 2025 (AI TL;DR for leaders): only 29% trust AI output accuracy, while 46% actively distrust it.

- Stack Overflow Developer Survey 2025 (AI agents section): 52% do not use AI agents or stick to simpler AI tools, and 38% have no plans to adopt agents.

Context and evolution: Early code assistants relied on static context. As repositories and model context windows grew, retrieval systems became essential for precision and traceability. Change-aware RAG is the next step, focusing on why and when changes occurred, not just what the code is now.

Old vs new approach:

Old: Static context only New: Change-aware RAG

+-----------------------+ +---------------------------+

| Current code snapshot | | Change index (diffs, PRs) |

| + model memory | | + retrieval + provenance |

+-----------------------+ +---------------------------+

| Answers can drift | | Answers cite evidence |

+-----------------------+ +---------------------------+

Concept Summary Table

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize |

|---|---|

| RAG Architecture | RAG is a memory system that retrieves evidence and packages it for agents with strict provenance. |

| Change Modeling | Code history is a graph; changes need structured records with metadata and rationale. |

| Chunking & Indexing | Retrieval quality depends on semantic chunking and multi-channel embeddings with metadata filters. |

| Retrieval & Ranking | Hybrid retrieval and time-aware ranking are essential for correct change questions. |

| Context Assembly | Evidence must be compressed and structured into a consistent packet with a prompt contract. |

| Evaluation & Safety | Retrieval quality, grounding, and redaction are core system guarantees. |

Project-to-Concept Map

| Project | Concepts Applied |

|---|---|

| Project 1: Change Capture Ledger | Change Modeling, RAG Architecture |

| Project 2: Diff Normalizer and Hunk Parser | Change Modeling, Chunking |

| Project 3: Semantic Chunker | Chunking & Indexing |

| Project 4: Embedding + Vector Index Baseline | Chunking & Indexing |

| Project 5: Hybrid Retrieval for Change Queries | Retrieval & Ranking |

| Project 6: Time-Aware Ranker | Retrieval & Ranking |

| Project 7: Context Packet Assembler | Context Assembly |

| Project 8: Conversation-Aware Retrieval | Context Assembly, RAG Architecture |

| Project 9: Evaluation Harness | Evaluation & Safety |

| Project 10: Redaction and Access Control | Evaluation & Safety |

| Project 11: Multi-Repo Federation | Retrieval & Ranking, Change Modeling |

| Project 12: End-to-End Change-Aware RAG CLI | All Concepts |

Deep Dive Reading by Concept

| Concept | Book and Chapter | Why This Matters |

|---|---|---|

| RAG Architecture | “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” by Kleppmann - Ch. 1-2 | Data flows, system design, and storage tradeoffs. |

| Change Modeling | “Working Effectively with Legacy Code” by Feathers - Ch. 2 | Understanding and evolving existing systems. |

| Chunking & Indexing | “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” by Kleppmann - Ch. 5-6 | Index design and retrieval tradeoffs. |

| Retrieval & Ranking | “Algorithms, Fourth Edition” by Sedgewick and Wayne - Ch. 5 | Ranking and search fundamentals. |

| Context Assembly | “Clean Architecture” by Robert C. Martin - Ch. 1, 22 | Interface and boundary design. |

| Evaluation & Safety | “Release It!” by Nygard - Ch. 4, 17 | Reliability and production risk. |

Quick Start: Your First 48 Hours

Day 1:

- Read Chapters 1 and 2 of the primer.

- Start Project 1 and ingest a small repo.

Day 2:

- Validate Project 1 with the Definition of Done.

- Skim Chapter 3 and prepare for chunking decisions.

Recommended Learning Paths

Path 1: The Builder

- Project 1 -> Project 2 -> Project 3 -> Project 4 -> Project 7 -> Project 12

Path 2: The Evaluator

- Project 1 -> Project 4 -> Project 5 -> Project 9 -> Project 10 -> Project 12

Path 3: The Production Engineer

- Project 1 -> Project 3 -> Project 5 -> Project 6 -> Project 7 -> Project 11 -> Project 12

Success Metrics

- You can answer change questions with evidence that maps to exact commits and files.

- Your retrieval metrics (P@3, MRR) are stable across at least two evaluation sets.

- Your pipeline can ingest new commits incrementally and maintain provenance.

- Sensitive data is redacted before it reaches the agent.

Optional Domain Appendices

Appendix A: Diff Format Cheat Sheet

+lines are additions,-lines are deletions, and context lines show unchanged code.- Hunk headers include old and new line ranges; preserve them for provenance.

Appendix B: Context Packet Template (Outline)

- Question

- Scope filters

- Primary evidence (top 3 chunks)

- Secondary evidence (summaries)

- Rationale notes

- Provenance table

- Output contract

Project List

The following projects guide you from raw git history to a production-grade change-aware RAG pipeline for code agents.

## Project 1: Change Capture Ledger

- File: P01_CHANGE_CAPTURE_LEDGER.md

- Main Programming Language: Python

- Alternative Programming Languages: Go, Rust, JavaScript

- Coolness Level: Level 2: Practical but Forgettable

- Business Potential: Level 3: Service and Support Model

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Data pipelines, version control, metadata modeling

- Software or Tool: Git, SQLite

- Main Book: “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” by Martin Kleppmann

What you will build: A change capture ledger that ingests git history into structured change records with provenance.

Why it teaches change-aware RAG: Retrieval quality starts with accurate change records. This project forces you to model commits, diffs, and metadata correctly.

Core challenges you will face:

- Commit graph extraction -> Change Modeling

- Provenance fields and schema -> Change Modeling

- Incremental ingestion -> RAG Architecture

Real World Outcome

A CLI tool that ingests a repo and prints a summary of change records.

Example output:

$ ragc ingest --repo ./my_repo --since 90d

Ingested commits: 214

Files changed: 1,932

Change chunks: 4,876

Latest commit: 2025-10-12 abc1234 "Reduce cache TTL to prevent stale reads"

The Core Question You Are Answering

“How do I turn raw git history into structured, queryable change records with provenance?”

This question matters because every downstream retrieval operation depends on the integrity of the change ledger.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Commit DAG and provenance

- How do merges affect the lineage of a change?

- Book Reference: “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” by Kleppmann - Ch. 2

- Change record schema

- What fields are mandatory to answer change questions later?

- Book Reference: “Working Effectively with Legacy Code” by Feathers - Ch. 2

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Ingestion strategy

- Will you ingest full history or incremental windows?

- How will you detect and skip already ingested commits?

- Schema choices

- Which fields must be indexed for retrieval?

- How will you store provenance and line ranges?

Thinking Exercise

The Commit Graph Trace

Diagram a merge commit and trace how a single file change moves from a feature branch to main.

Questions to answer:

- Which commit id should be considered the source of truth?

- How would you handle a commit that is reverted later?

The Interview Questions They Will Ask

- “Explain how git stores history and why it is a DAG.”

- “What metadata is essential for tracing a change back to its source?”

- “How would you implement incremental ingestion safely?”

- “What happens to provenance when a file is renamed?”

- “How do you handle merge commits in a change history system?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Starting Point

Start with git log --name-status and capture commit ids, timestamps, and file lists.

Hint 2: Next Level Add diff extraction and store raw hunks alongside metadata.

Hint 3: Technical Details Create a change record schema with commit id, file path, operation type, and hunk list.

Hint 4: Tools/Debugging

Verify provenance by re-running git show <commit> and matching line ranges.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter | |——-|——|———| | Change history modeling | “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” | Ch. 2 | | Legacy system understanding | “Working Effectively with Legacy Code” | Ch. 2 |

Common Pitfalls and Debugging

Problem 1: “Missing commits after a re-run”

- Why: Incremental ingestion is not using a stable cursor.

- Fix: Store the last ingested commit id per branch.

- Quick test: Ingest twice and verify counts are unchanged.

Problem 2: “Renamed files look like deletes”

- Why: Rename detection is off.

- Fix: Use git rename detection flags and store rename metadata.

- Quick test: Ingest a known rename commit and inspect fields.

Definition of Done

- All commits within a time window are ingested with metadata

- Each change record has provenance (commit id, file path, line ranges)

- Incremental ingestion skips duplicates safely

- Sample queries show correct change counts

## Project 2: Diff Normalizer and Hunk Parser

- File: P02_DIFF_NORMALIZER.md

- Main Programming Language: Python

- Alternative Programming Languages: Go, Rust, JavaScript

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: Level 2: Micro-SaaS / Pro Tool

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Parsing, text processing, diff formats

- Software or Tool: Git diff

- Main Book: “Refactoring” by Martin Fowler

What you will build: A parser that converts unified diffs into structured hunks with line-level labels.

Why it teaches change-aware RAG: Proper chunking requires structured diffs; this is the foundation for semantic chunking.

Core challenges you will face:

- Diff format parsing -> Change Modeling

- Line classification (add/delete/context) -> Chunking & Indexing

- Rename and binary handling -> Change Modeling

Real World Outcome

A CLI tool that parses a diff and prints structured hunk statistics.

Example output: