Project 10: Kids Learning Hub

Build a modular learning hub that bundles multiple mini-apps with shared progress and a parent dashboard.

Quick Reference

| Attribute | Value |

|---|---|

| Difficulty | Level 3 (Advanced) |

| Time Estimate | 3-5 weeks |

| Main Programming Language | Swift (Alternatives: Objective-C, C# Unity, JavaScript React Native) |

| Alternative Programming Languages | Objective-C, C# Unity, JavaScript React Native |

| Coolness Level | Level 4 (Hardcore Tech Flex) |

| Business Potential | Level 3 (Service & Support Model) |

| Prerequisites | Projects 1-9 concepts |

| Key Topics | Modular architecture, content packs, shared progress |

1. Learning Objectives

By completing this project, you will:

- Design a modular architecture for multiple learning activities.

- Build a shared progress system with privacy-safe storage.

- Create a consistent UX across different mini-apps.

- Ensure compliance rules apply across all modules.

2. All Theory Needed (Per-Concept Breakdown)

Modular Content Packs and Shared Progress

Fundamentals

A learning hub is a container for multiple activities. Instead of one app, you manage a collection of mini-apps that share navigation, progress tracking, and parental controls. The key is modularity: each activity should be independent, but the hub should provide consistent UX and shared data.

A content pack is a structured set of assets and metadata for a module. For example, a flashcard module has letters, images, and audio. A counting module has object sets and answer choices. By defining each module as a content pack, you can add or remove modules without rewriting the hub.

Shared progress is a summary across modules. It should be local and anonymous. The hub should track what activities were completed, and provide a parent dashboard with a simple overview. The parent dashboard is gated, just like in Project 6.

A modular hub is also a product experience. The home screen is the child’s “map” of activities. It should be simple and inviting, with large tiles and clear icons. The module list should not overwhelm. A grid of 4-6 tiles per screen is enough.

Consistency is the other fundamental. If each module uses a different style, the child will feel like they are switching apps. A shared design language is part of the architecture. That means shared typography, consistent audio cues, and similar navigation patterns.

The hub should also respect parental trust. The parent zone should be visible and gated, and all modules should follow the same privacy rules. A single weak module can undermine trust in the whole hub.

Another fundamental is upgradeability. A hub will evolve over time. If you add a new module, the hub should handle it gracefully without breaking existing progress. This means the module list and progress store must be flexible and robust to change.

The hub should also provide a sense of progression. A small progress indicator on each tile helps children and parents see what has been completed. This does not require detailed analytics; a simple percent or “stars earned” is enough. The key is consistency across modules.

A hub also needs a clear exit path from modules. Children should always be able to return to the home screen without getting lost. A consistent “Home” button in the same position across modules is a simple but powerful design decision.

The hub can also encourage exploration by showing a “Try this next” suggestion based on recent activity. This can be a simple rule, such as recommending the next module in the grid order, without any data profiling.

Module tiles should be large enough for small hands. Even on phones, aim for no more than two tiles per row. This keeps tap targets large and reduces accidental selection.

The hub should load quickly even on older devices. This means the home screen should use lightweight assets and avoid large background images. Fast startup builds trust for parents.

A consistent home screen layout helps children build spatial memory for where each activity lives.

Even small consistency cues, like the same back button, build confidence.

Deep Dive into the Concept

Modular architecture solves two problems: scale and maintainability. In a learning hub, each module can evolve separately. If the flashcard module changes, the counting module should not break. This requires a clear interface between the hub and modules. A simple interface might include: module id, title, icon, entry screen, and progress summary function.

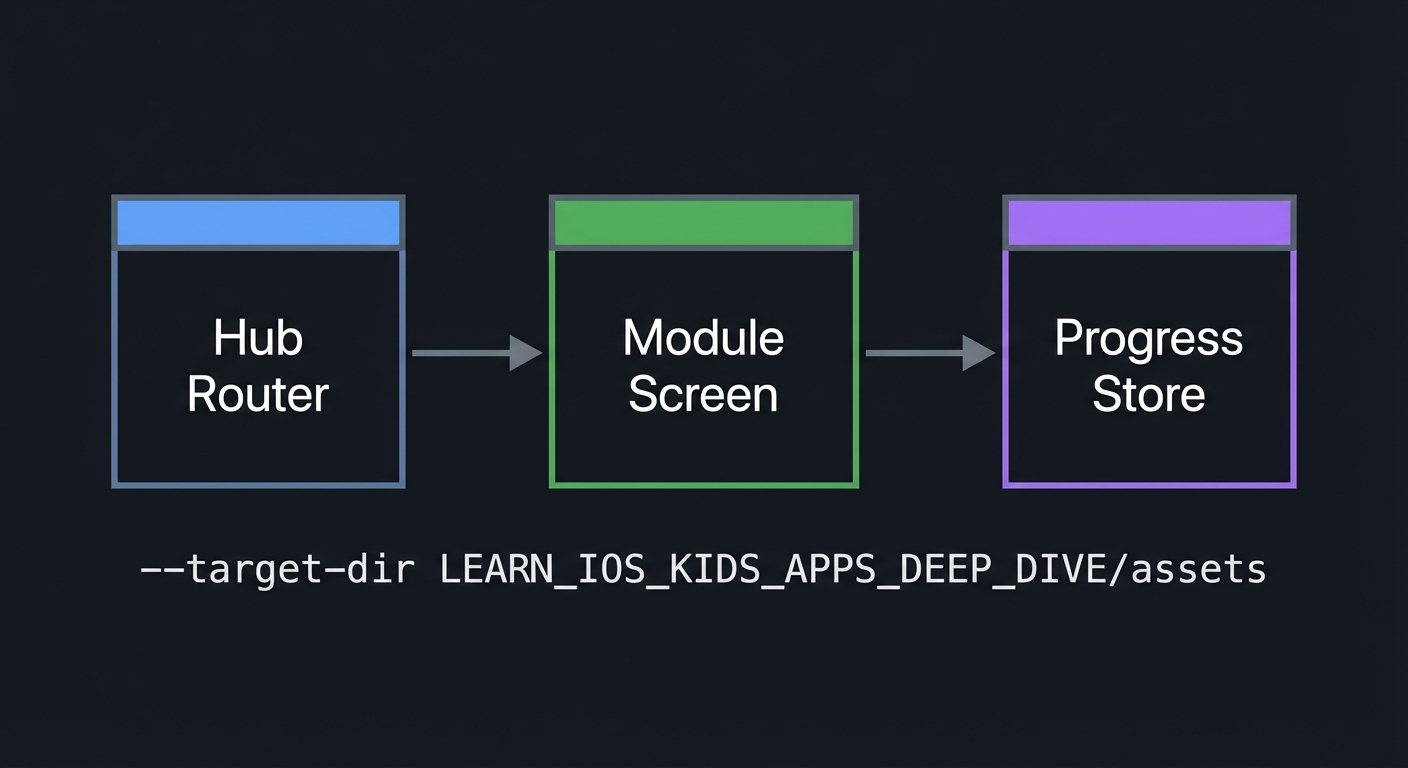

The hub acts like a router. It displays a home screen with tiles for each module. When a tile is tapped, the hub switches to that module’s screen. The module owns its internal state, but the hub owns the global navigation and progress store. This separation reduces coupling and makes it easier to test modules independently.

Content packs are the data layer for modules. For a kid-safe app, these packs should be static and bundled with the app. That avoids network dependencies and data collection. A pack includes assets and a small manifest file. The manifest describes the module’s content and rules. This is similar to how storybook pages are defined in Project 3, but generalized.

Shared progress is trickier. Each module must report progress in a consistent way. For example, the flashcard module might report “letters completed,” while the memory game reports “pairs matched.” The hub should translate these into a common progress summary. A simple approach is to normalize each module’s progress into a percentage or a completion count. The hub then displays these in a parent dashboard.

Privacy is critical. The hub must not collect personal data across modules. Progress should be stored locally with anonymous identifiers. If you support multiple child profiles, use icons or colors instead of names. The parent dashboard should show aggregated progress, not detailed logs.

Consistency in UX is another challenge. Each module should feel like part of the same app. That means consistent typography, color palette, and feedback tone. You can allow small variations, but the overall experience should feel unified. This consistency builds trust for parents and reduces confusion for kids.

The hub also enforces compliance. If any module has an external link, it must be gated. If any module uses audio, it must follow the same privacy rules. The hub can define global policies: no network calls, no analytics, no external links without gate. Modules must comply with these policies.

Performance is important because the hub might load multiple modules. You should lazy-load assets for a module only when it is opened, to avoid heavy startup times. But you should still keep the experience smooth when switching modules. This can be achieved by caching recently used assets in memory.

Testing modular systems requires both module-level tests and hub-level integration tests. You should verify that a module can be opened and closed without losing its state, and that progress updates propagate to the hub. You should also verify that the parent dashboard shows accurate summaries.

Finally, the hub should provide a clear path for growth. A hub is not just a container; it is a product. It should communicate what the child can do, what they have done, and what is next. This can be as simple as a progress bar and a “next recommended” tile. The recommendation should be local and simple, not data-mined.

Module contracts are the technical backbone of the hub. A contract defines what the hub expects from each module and what the module can expect from the hub. This includes how progress is reported and how the module is launched. A strict contract makes it easier to add new modules without breaking existing ones.

Progress normalization is also crucial. If one module reports progress as “5 completed” and another as “80 percent,” the hub cannot compare them. A normalized format, such as a percent complete plus a short text summary, allows a consistent parent dashboard.

Storage namespacing prevents data collisions. Every module should store its data under a unique prefix. This prevents the memory game from overwriting flashcard progress and makes it easier to debug data issues.

Global policies should be enforced at the hub level. For example, if external links are allowed only through the parent gate, the hub should provide a shared link-opening function that always enforces the gate. This reduces the chance that a module accidentally bypasses compliance rules.

Versioning is an advanced but important concept. If a module changes its progress format, the hub must migrate old data. You can handle this by storing a version number with each module’s data and providing a simple migration step on load.

Integration testing should include switching between modules, updating progress, and checking the parent dashboard. Because the hub is a system-of-systems, integration bugs are common. A dedicated “integration test checklist” helps you verify that modules work together.

A shared style guide is a practical tool. Define a small set of colors, font sizes, button styles, and feedback sounds. Each module should use these shared resources. This prevents drift and reduces cognitive load for children who move between activities.

When adding new modules, the hub should validate that required assets exist. A missing icon or title should not crash the app. Instead, show a fallback tile. This defensive design keeps the hub stable as it grows.

When multiple modules write to shared storage, you should define a conflict rule. For example, if a module writes progress during an app background event, ensure that data is not lost. A simple last-write-wins policy is usually sufficient for local-only storage.

Document your module interface in a short README inside the modules folder. This is not just for other developers; it helps you maintain consistency as you add more modules later.

A simple health check on startup can verify that all modules registered correctly. If a module is missing, you can hide its tile rather than showing a broken entry. This keeps the hub stable.

When a module updates its progress, the hub should update the tile without a full refresh. This keeps the UI responsive and reinforces the sense of progress for the child.

How this Fits in the Project

This project is the culmination of the series. It combines modules, shared progress, and parental controls into a single product structure.

Definitions & Key Terms

- Module: A self-contained mini-app inside the hub.

- Content pack: A bundle of assets and metadata for a module.

- Hub router: The navigation layer that switches between modules.

- Shared progress: A unified summary across modules.

- Global policy: Compliance and UX rules applied across modules.

Mental Model Diagram (ASCII)

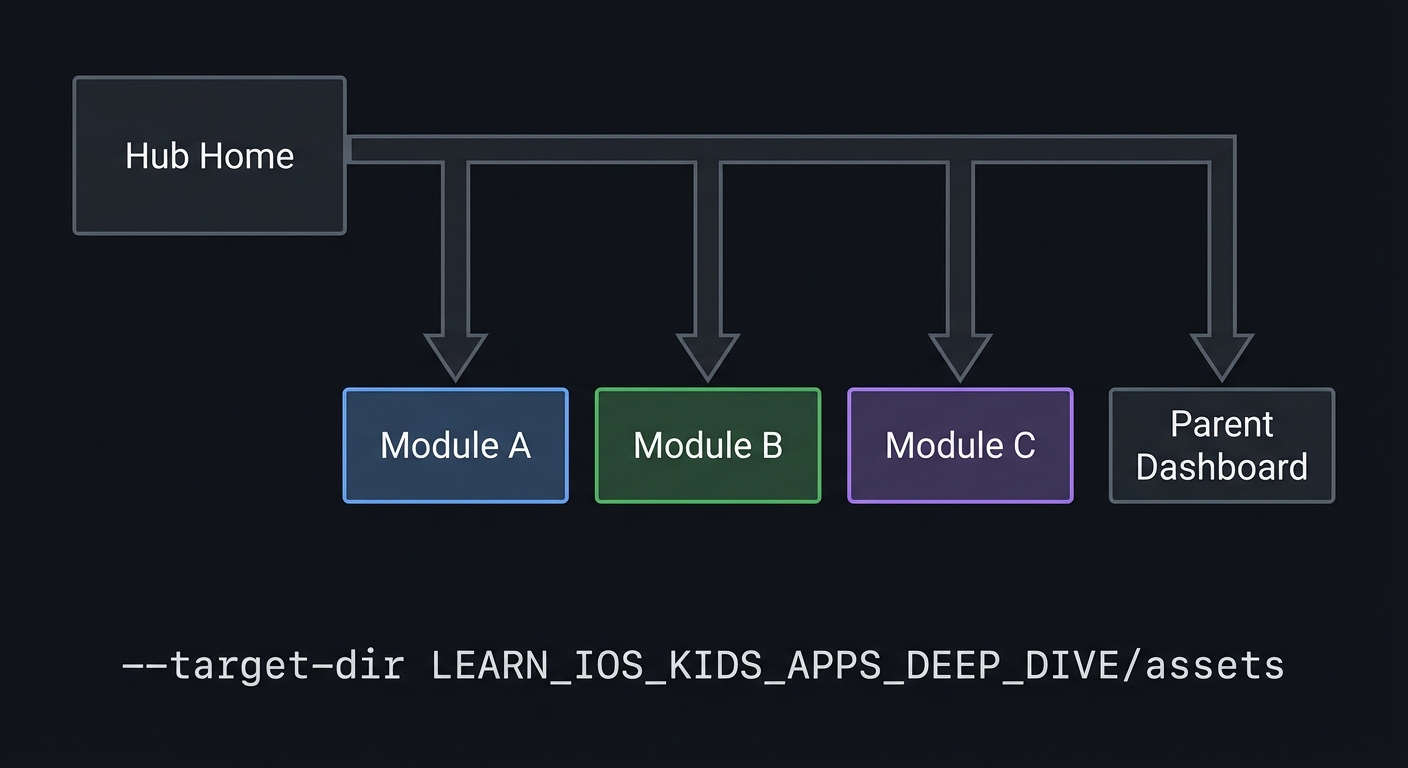

Hub Home -> Module A

-> Module B

-> Module C

-> Parent Dashboard

How It Works (Step-by-Step)

- Load module list from content packs.

- Render hub home tiles.

- On tile tap, open the module screen.

- Module updates its progress in the shared store.

- Parent dashboard reads progress from shared store.

Invariants:

- Modules are independent.

- Parent zone is gated.

Failure modes:

- Progress from one module overwrites another.

- Module bypasses compliance rules.

Minimal Concrete Example (Pseudocode)

STATE: modules[], progressStore

ON moduleComplete:

UPDATE progressStore[moduleId]

ON parentDashboardOpen:

READ all progress summaries

Common Misconceptions

- “A hub is just a menu.” It is also a shared architecture and data system.

- “Modules can be fully independent.” They must still follow global policies.

- “Progress tracking requires accounts.” It can be local and anonymous.

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- Why is a shared progress format important?

- How do content packs reduce coupling?

- What risks arise if modules ignore global policies?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- Without it, the hub cannot compare or summarize modules.

- Modules can be updated by changing data, not code.

- A module could violate privacy or App Store rules.

Real-World Applications

- Learning suites with multiple mini-games

- Educational subscription apps

- Classroom activity hubs

Where You Will Apply It

- In this project: see Section 3.7 Real World Outcome and Section 5.10 Implementation Phases.

- Also used in: all previous projects as modules.

References

- “Clean Architecture” by Robert C. Martin - Ch. 2-3

- “Design It!” by Michael Keeling - Ch. 3

Key Insight

A hub succeeds when modules are independent but progress and policies are shared.

Summary

The learning hub is a modular system with shared progress and consistent UX. It is the natural evolution of the earlier projects.

Homework / Exercises to Practice the Concept

- Define a common progress format for three different modules.

- Sketch a hub home screen with six tiles and a parent button.

- List global policies that all modules must follow.

Solutions to the Homework / Exercises

- Each module reports a percent complete and a short summary string.

- Grid of six large tiles with a small parent icon in corner.

- No external links without gate, no analytics, offline-first.

3. Project Specification

3.1 What You Will Build

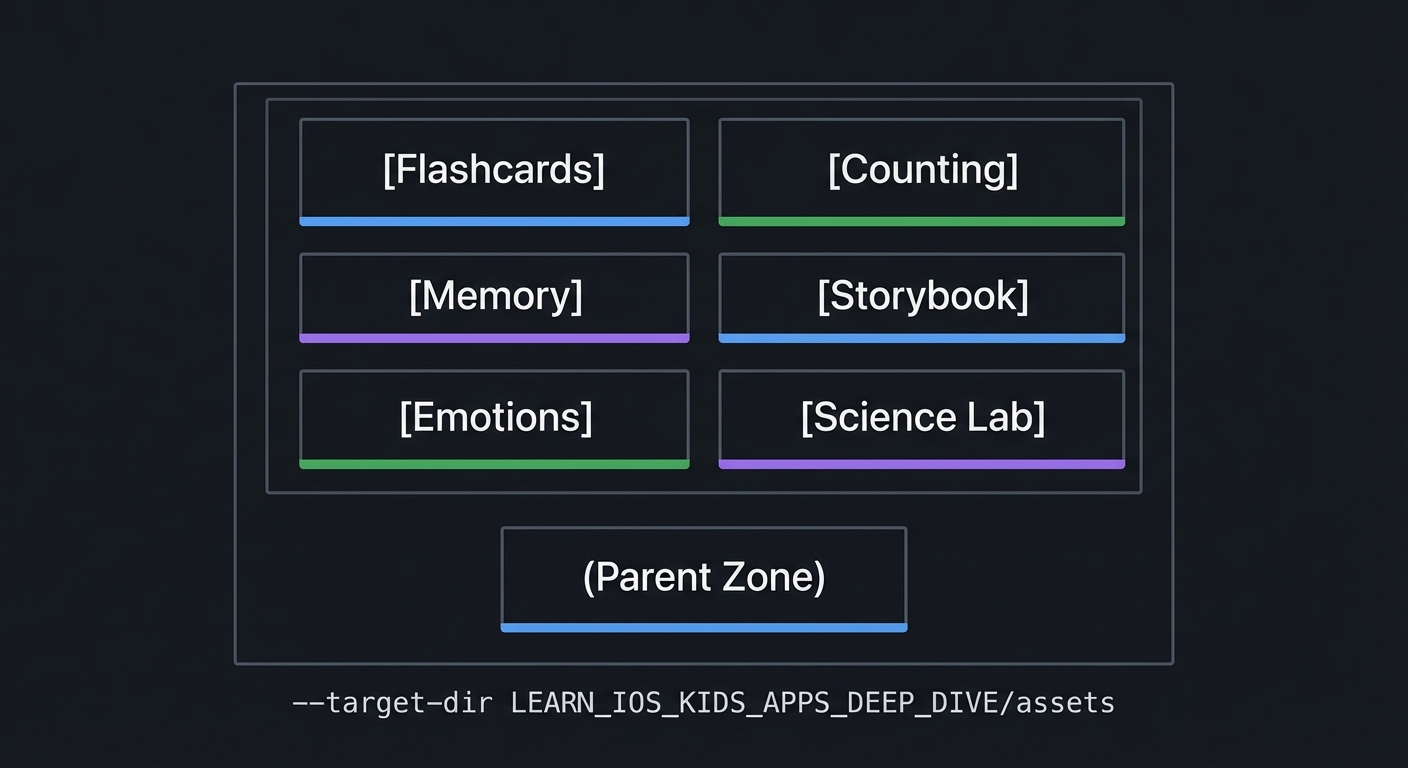

A hub app with six modules (flashcards, counting, memory, storybook, emotions, science lab), a shared progress store, and a gated parent dashboard.

3.2 Functional Requirements

- Hub home: Display module tiles.

- Module routing: Open modules from tiles.

- Shared progress: Store module progress locally.

- Parent dashboard: Show progress summaries with gate.

3.3 Non-Functional Requirements

- Performance: Hub loads quickly.

- Reliability: Progress is consistent across modules.

- Usability: Consistent UI across modules.

3.4 Example Usage / Output

ASCII wireframe:

+----------------------------------+

| [Flashcards] [Counting] |

| [Memory] [Storybook] |

| [Emotions] [Science Lab] |

| |

| (Parent Zone) |

+----------------------------------+

3.5 Data Formats / Schemas / Protocols

- Module: { id, title, icon, entry }

- Progress: { module_id, percent_complete, summary }

3.6 Edge Cases

- Module missing assets

- Progress store corrupted

- Parent zone opened mid-module

3.7 Real World Outcome

3.7.1 How to Run (Copy/Paste)

- Run in iPad simulator for grid layout.

3.7.2 Golden Path Demo (Deterministic)

Scenario: Open hub, launch flashcards, complete a card, return to hub.

Expected behavior:

- Hub shows updated progress for flashcards.

- No other module progress changes.

3.7.3 Failure Demo (Deterministic)

Scenario: Module progress key missing.

Expected behavior:

- Hub shows “0%” for that module and continues.

3.7.4 Mobile UI Details

- Grid of large tiles.

- Parent zone button in corner.

- Consistent colors across modules.

4. Solution Architecture

4.1 High-Level Design

+-------------+ +------------------+ +------------------+

| Hub Router | ---> | Module Screen | ---> | Progress Store |

+-------------+ +------------------+ +------------------+

4.2 Key Components

| Component | Responsibility | Key Decisions |

|---|---|---|

| Hub Home | Displays tiles | Grid layout |

| Module Interface | Entry + progress summary | Common format |

| Progress Store | Shared local data | Namespaced keys |

| Parent Dashboard | Aggregates progress | Gated access |

4.3 Data Structures (No Full Code)

- ModuleList: list of module descriptors

- ProgressMap: map of module_id -> summary

4.4 Algorithm Overview

Key Algorithm: Progress Update

- Module reports progress update.

- Hub updates shared store.

- Dashboard reads summaries.

Complexity Analysis:

- Time: O(M) to render hub (M modules)

- Space: O(M) for progress store

5. Implementation Guide

5.1 Development Environment Setup

xcodebuild -version

5.2 Project Structure

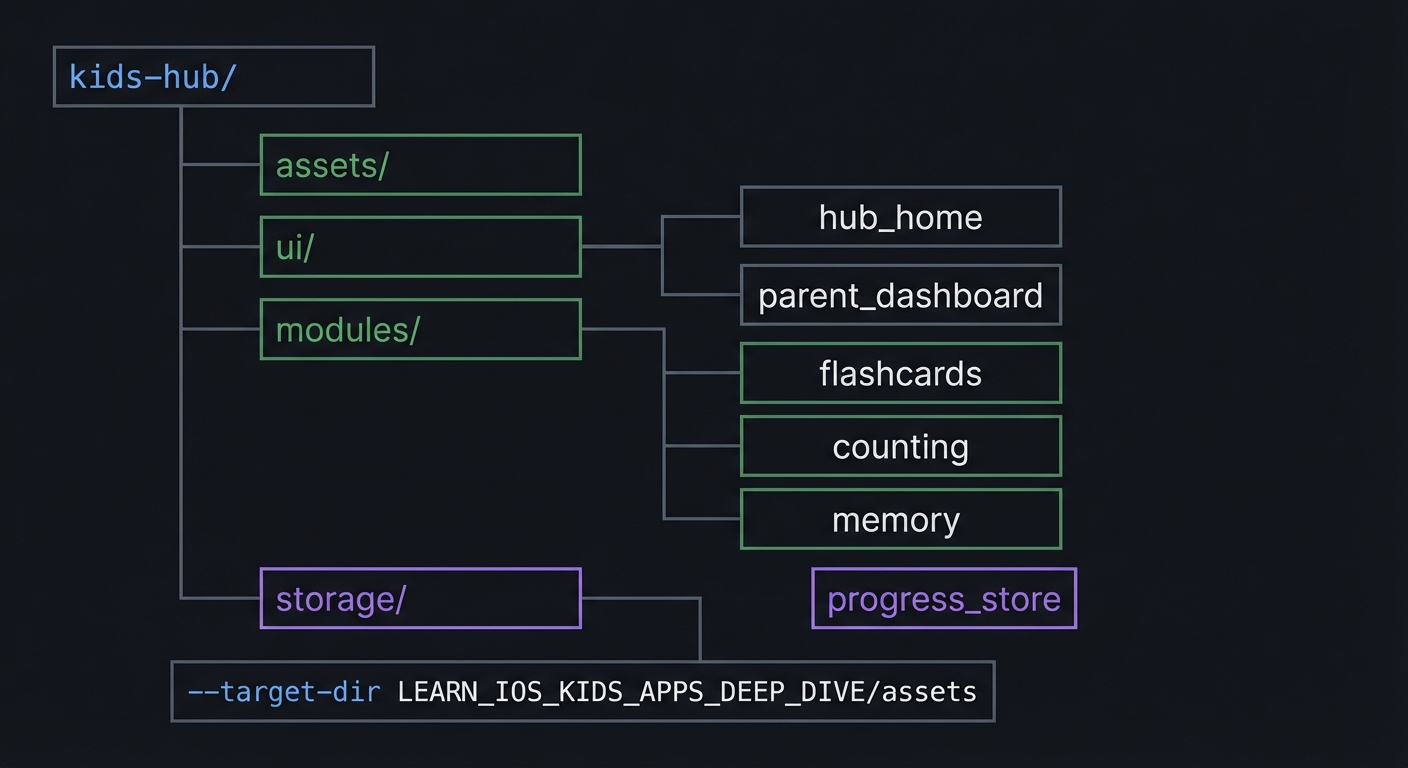

kids-hub/

+-- assets/

+-- ui/

| +-- hub_home

| `-- parent_dashboard

+-- modules/

| +-- flashcards

| +-- counting

| `-- memory

`-- storage/

`-- progress_store

5.3 The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do I scale from one kids app to a unified learning platform?”

5.4 Concepts You Must Understand First

- Modular architecture

- How do modules communicate with the hub?

- Book Reference: “Clean Architecture” - Ch. 2

- Shared progress

- How do you normalize progress across modules?

- Book Reference: “Clean Architecture” - Ch. 2

5.5 Questions to Guide Your Design

- Module interface

- What is the minimal contract each module must implement?

- Progress store

- How do you avoid key collisions between modules?

5.6 Thinking Exercise

Hub Contract

Write down the interface every module should expose (id, title, entry, progress summary).

5.7 The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “How do you design a modular learning hub?”

- “Why does shared progress need normalization?”

- “How do you enforce global compliance rules?”

- “What happens if a module fails?”

- “How do you test module boundaries?”

5.8 Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with two modules Do not add all modules at once.

Hint 2: Define a module contract Force each module to expose progress summary.

Hint 3: Namespace keys Prefix storage keys with module id.

Hint 4: Add a debug dashboard Show raw progress data for testing.

5.9 Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Architecture | “Clean Architecture” | Ch. 2-3 |

5.10 Implementation Phases

Phase 1: Foundation (6-10 hours)

Goals:

- Hub home UI

- Module list

Tasks:

- Build hub home with tiles.

- Define module descriptors.

Checkpoint: Hub lists modules correctly.

Phase 2: Core Functionality (12-18 hours)

Goals:

- Module navigation

- Shared progress store

Tasks:

- Implement navigation to modules.

- Store progress per module.

Checkpoint: Progress updates appear on hub.

Phase 3: Polish & Edge Cases (10-16 hours)

Goals:

- Parent dashboard

- Consistent styling

Tasks:

- Add gated parent dashboard.

- Apply consistent style across modules.

Checkpoint: Hub feels unified and safe.

5.11 Key Implementation Decisions

| Decision | Options | Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Module contract | Loose vs strict | Strict | Consistency |

| Progress format | Raw vs normalized | Normalized | Comparable summaries |

| Asset loading | All at start vs lazy | Lazy | Faster startup |

6. Testing Strategy

6.1 Test Categories

| Category | Purpose | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Unit | Progress updates | Map entries |

| Integration | Module switching | Navigation |

| Edge Case | Missing module | Safe fallback |

6.2 Critical Test Cases

- Progress from one module does not overwrite others.

- Hub loads even if a module fails to load assets.

- Parent dashboard shows correct summaries.

6.3 Test Data

Module progress: flashcards 30%, counting 10%

7. Common Pitfalls & Debugging

7.1 Frequent Mistakes

| Pitfall | Symptom | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Key collisions | Progress overwrites | Namespace keys |

| Inconsistent UI | Modules feel different | Shared style guide |

| Heavy startup | Slow load | Lazy load assets |

7.2 Debugging Strategies

- Add a debug screen showing raw progress data.

- Simulate missing assets to test fallback behavior.

7.3 Performance Traps

- Loading all module assets at startup.

8. Extensions & Challenges

8.1 Beginner Extensions

- Add a new module tile and stub screen.

8.2 Intermediate Extensions

- Add a parent toggle to disable modules.

8.3 Advanced Extensions

- Add anonymous multi-profile support.

9. Real-World Connections

9.1 Industry Applications

- Subscription learning suites

- Classroom app bundles

9.2 Related Open Source Projects

- Look for modular educational app frameworks.

9.3 Interview Relevance

- Modular architecture

- Shared data models

10. Resources

10.1 Essential Reading

- “Clean Architecture” - Ch. 2-3

10.2 Video Resources

- Talks on modular architecture

10.3 Tools & Documentation

- Apple HIG for app suites

10.4 Related Projects in This Series

11. Self-Assessment Checklist

11.1 Understanding

- I can explain a module contract.

- I can explain shared progress normalization.

- I can explain global compliance rules.

11.2 Implementation

- Hub lists modules correctly.

- Progress updates are accurate.

- Parent dashboard is gated.

11.3 Growth

- I can describe how to add a new module.

- I can explain the architecture in an interview.

12. Submission / Completion Criteria

Minimum Viable Completion:

- Hub with two modules and shared progress

Full Completion:

- Six modules with parent dashboard

Excellence (Going Above & Beyond):

- Multi-profile support and module toggles