Project 8: Lazy Evaluation Demonstrator

Understanding Haskell’s Secret Weapon and Biggest Footgun

- Main Programming Language: Haskell

- Alternative Languages: Scala (with lazy vals), OCaml (with Lazy module)

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Difficulty: Level 4: Expert

- Knowledge Area: Evaluation Strategies / Laziness

- Estimated Time: 3-4 weeks

- Prerequisites: Basic Haskell, understanding of recursion, familiarity with data structures

Learning Objectives

After completing this project, you will be able to:

- Explain the difference between strict and lazy evaluation - Describe call-by-value, call-by-name, and call-by-need with precise definitions

- Understand thunks at the implementation level - Draw diagrams showing how thunks are represented in memory and when they get evaluated

- Recognize Weak Head Normal Form (WHNF) - Identify when a value is in WHNF vs fully evaluated

- Work with infinite data structures - Create and manipulate infinite lists, trees, and other structures enabled by laziness

- Diagnose and fix space leaks - Identify when thunk accumulation causes memory problems and apply solutions

- Use strictness annotations effectively - Apply

seq,deepseq,BangPatterns, and strict data types appropriately - Implement a lazy evaluator - Build a simple interpreter that demonstrates thunk creation, forcing, and sharing

Conceptual Foundation

What Is Evaluation Strategy?

An evaluation strategy determines when and how arguments to functions are evaluated. This seemingly simple choice has profound consequences for expressiveness, performance, and reasoning about programs.

Consider this function call:

f (expensive_computation)

When is expensive_computation evaluated?

Three main strategies:

- Call-by-value (Strict/Eager): Evaluate argument before calling function

- Used by: C, Java, Python, Rust, OCaml (default)

expensive_computationruns beforefis called- If

fdoesn’t use its argument, we wasted work

- Call-by-name: Substitute argument expression into function body

- Each use re-evaluates the expression

- If

fuses its argument 3 times,expensive_computationruns 3 times

- Call-by-need (Lazy): Evaluate argument only when needed, then cache the result

- Used by: Haskell, Miranda, Clean

expensive_computationruns at most once, when first needed- Result is shared for subsequent uses

The Church-Rosser Property

A crucial theoretical result underpins lazy evaluation: the Church-Rosser theorem states that if an expression can be reduced to a normal form (fully evaluated result), any reduction order will reach the same result.

This means:

-- These produce the same answer:

(\x -> x + x) (2 + 3)

-- Eager evaluation:

(\x -> x + x) 5 -- Evaluate argument first

5 + 5

10

-- Lazy evaluation:

(2 + 3) + (2 + 3) -- Substitute argument

5 + (2 + 3) -- Evaluate left

5 + 5 -- Evaluate right

10

Same answer! But different amounts of work. Eager evaluation computed 2 + 3 once. Our naive lazy version computed it twice.

Call-by-need solves this with sharing: the first time we need (2 + 3), we evaluate it and remember the result.

Why Laziness Matters: Termination

Lazy evaluation can find answers that strict evaluation cannot:

-- This function ignores its second argument

first :: a -> b -> a

first x y = x

-- What happens here?

first 42 (error "crash!")

Strict evaluation:

- Evaluate first argument:

42 - Evaluate second argument:

error "crash!"- CRASH!

Lazy evaluation:

- Call

firstwith unevaluated thunks firstonly needsx, never forcesy- Returns

42- no crash!

This isn’t just academic. It enables:

-- Safe default values

fromMaybe default maybeValue = case maybeValue of

Nothing -> default

Just x -> x

-- 'default' is only evaluated if needed!

fromMaybe (expensive_computation) (Just 42) -- Never computes default

-- Short-circuit operators

(&&) :: Bool -> Bool -> Bool

False && _ = False -- Second argument never evaluated!

True && x = x

-- 'error' is never evaluated:

False && error "crash" -- Returns False

Infinite Data Structures

Laziness enables something impossible in strict languages: infinite data structures.

-- An infinite list of ones

ones :: [Int]

ones = 1 : ones

-- What does this mean?

-- ones = 1 : (1 : (1 : (1 : ...)))

-- An infinite list!

-- All natural numbers

nats :: [Int]

nats = 0 : map (+1) nats

-- nats = 0 : 1 : 2 : 3 : 4 : ...

-- Fibonacci sequence

fibs :: [Int]

fibs = 0 : 1 : zipWith (+) fibs (tail fibs)

-- fibs = 0 : 1 : 1 : 2 : 3 : 5 : 8 : 13 : ...

How can we store an infinite list? We can’t! But we don’t need to. We only store what we’ve computed so far, plus a thunk representing “the rest.”

Before any evaluation:

ones = THUNK(1 : ones)

After taking 1 element:

ones = 1 : THUNK(1 : ones)

After taking 3 elements:

ones = 1 : 1 : 1 : THUNK(1 : ones)

The thunk is a suspended computation. It contains enough information to continue the computation when needed.

Thunks: Suspended Computations

A thunk is a data structure representing an unevaluated expression. It contains:

- Code pointer: The function to compute the value

- Environment/Free variables: Values needed for the computation

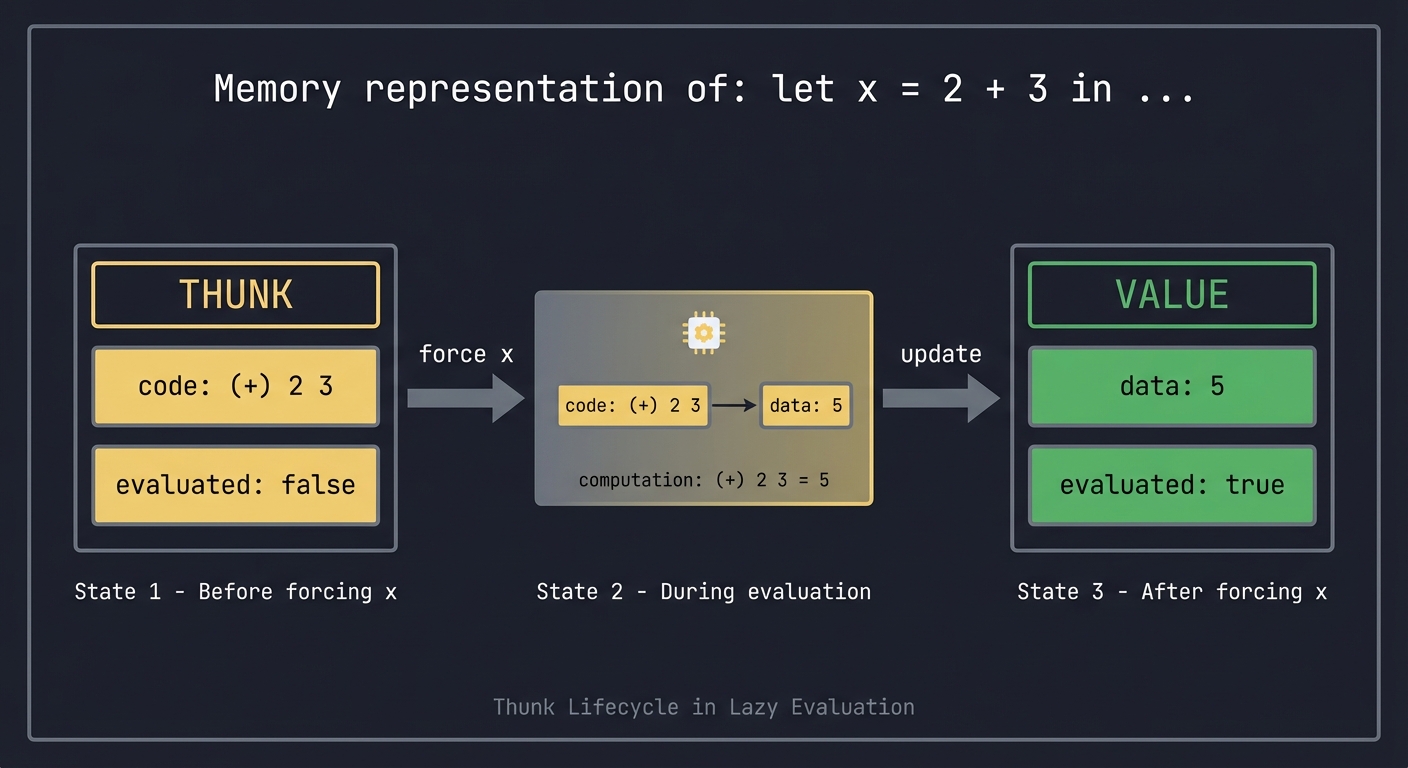

Memory representation of: let x = 2 + 3 in ...

Before forcing x:

+------------------+

| THUNK |

+------------------+

| code: (+) 2 3 |

| evaluated: false |

+------------------+

After forcing x:

+------------------+

| VALUE |

+------------------+

| data: 5 |

| evaluated: true |

+------------------+

When the thunk is forced (its value is needed), it:

- Executes the computation

- Overwrites itself with the result

- Future accesses get the value directly

This overwriting is called update or memoization, and it’s what makes call-by-need efficient.

Weak Head Normal Form (WHNF)

Haskell doesn’t fully evaluate expressions; it evaluates them to Weak Head Normal Form (WHNF). Understanding WHNF is crucial for understanding laziness.

A value is in WHNF if:

- It’s a constructor applied to (possibly unevaluated) arguments, OR

- It’s a lambda (partial application counts)

Examples:

-- In WHNF (constructor applied):

Just (2 + 3) -- Just applied to thunk

(2 + 3) : [1, 2, 3] -- (:) applied to thunks

\x -> x + expensive -- Lambda

(+) 5 -- Partial application (a lambda)

-- NOT in WHNF (computation needed to expose constructor):

2 + 3 -- Need to compute to get a number

if True then 1 else 2 -- Need to compute to get the 1

head [1, 2, 3] -- Need to compute to get 1

Just (2 + 3) >>= f -- Need to pattern match on Just

Why WHNF? It’s the minimal evaluation needed to make decisions:

case xs of

[] -> ...

(y:ys) -> ...

We need to know: is xs empty or non-empty? We need to see the outermost constructor. We don’t need to evaluate the elements.

Normal Form vs WHNF

Normal Form (NF): Fully evaluated, no thunks anywhere

-- In NF:

5

[1, 2, 3]

Just "hello"

-- In WHNF but NOT NF:

Just (2 + 3) -- The (2 + 3) is still a thunk

1 : [2 + 3] -- The [2 + 3] contains thunks

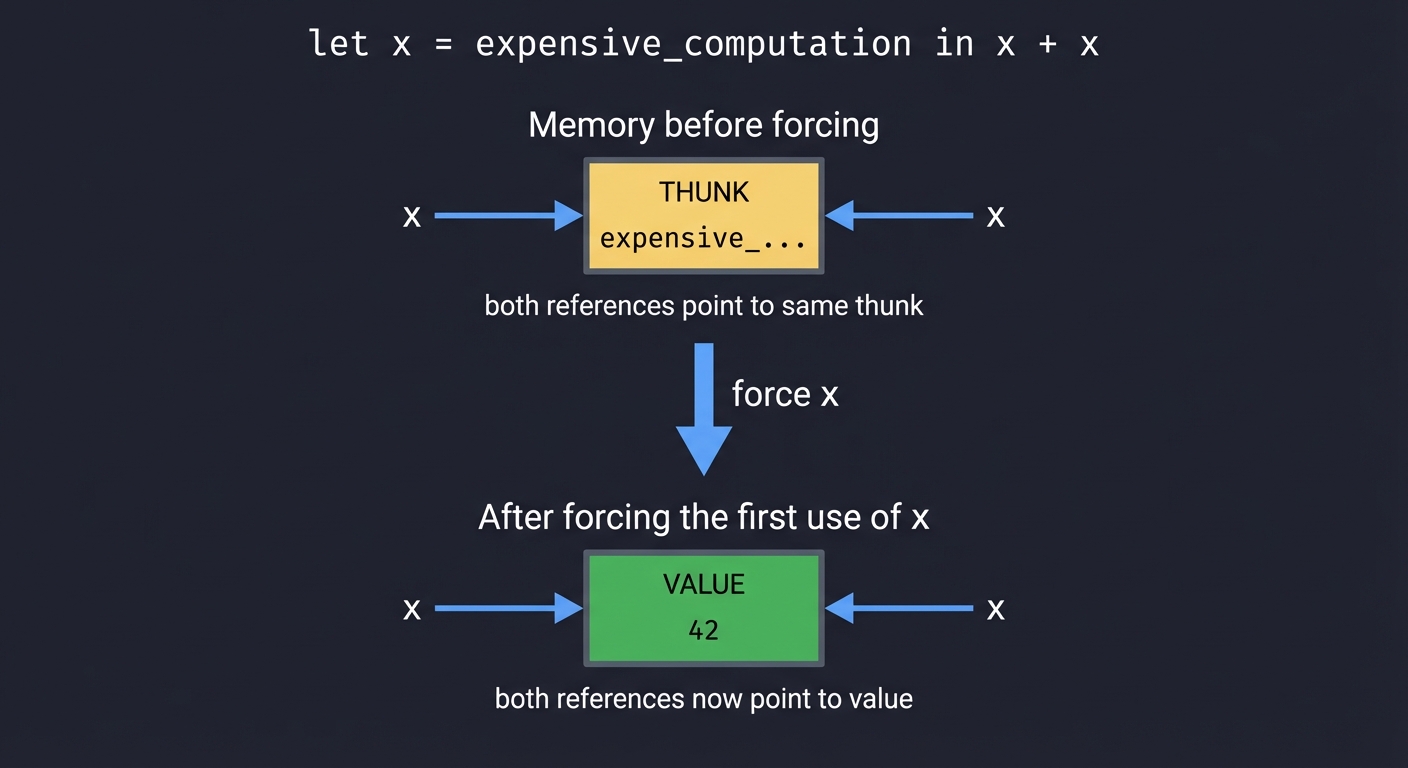

Sharing: The Key to Efficiency

Sharing means multiple references to the same thunk. When the thunk is forced, all references see the computed value.

let x = expensive_computation

in x + x

Memory before forcing:

+---------------+

| THUNK |

| expensive_... |

+---------------+

^ ^

| |

x x (both references point to same thunk)

After forcing the first use of x:

+---------------+

| VALUE |

| 42 |

+---------------+

^ ^

| |

x x (both references now point to value)

The computation happens once, and both uses of x see the result.

Contrast with call-by-name (no sharing):

-- Call-by-name would substitute:

expensive_computation + expensive_computation

-- And compute twice!

When Is a Thunk Forced?

Understanding when evaluation happens is essential. A thunk is forced when:

- Pattern matching on its outermost constructor

case thunk of

Just x -> ... -- Forces thunk to expose Just or Nothing

Nothing -> ...

- Primitive operations that need the value

thunk + 1 -- (+) needs the numeric value

show thunk -- show needs the value

- seq or deepseq explicitly force evaluation

seq thunk rest -- Forces thunk to WHNF, returns rest

deepseq thunk rest -- Forces thunk to NF, returns rest

- IO operations that need to perform effects

print thunk -- Must evaluate to print

Space Leaks: When Laziness Goes Wrong

A space leak occurs when thunks accumulate faster than they’re evaluated, consuming excessive memory.

Classic example: naive sum

sum :: [Int] -> Int

sum [] = 0

sum (x:xs) = x + sum xs

sum [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

Evaluation:

sum [1,2,3,4,5]

= 1 + sum [2,3,4,5]

= 1 + (2 + sum [3,4,5])

= 1 + (2 + (3 + sum [4,5]))

= 1 + (2 + (3 + (4 + sum [5])))

= 1 + (2 + (3 + (4 + (5 + sum []))))

= 1 + (2 + (3 + (4 + (5 + 0))))

Before any additions happen, we’ve built a chain of thunks proportional to the list length! This uses O(n) memory instead of O(1).

The fix: strict accumulator

sum :: [Int] -> Int

sum = go 0

where

go !acc [] = acc

go !acc (x:xs) = go (acc + x) xs

The ! (bang pattern) forces acc at each step:

go 0 [1,2,3,4,5]

go 1 [2,3,4,5] -- acc forced to 1

go 3 [3,4,5] -- acc forced to 3

go 6 [4,5] -- acc forced to 6

go 10 [5] -- acc forced to 10

go 15 [] -- acc forced to 15

15

Now we use O(1) memory!

The foldl vs foldl’ Distinction

-- foldl builds up thunks (lazy)

foldl :: (b -> a -> b) -> b -> [a] -> b

foldl f z [] = z

foldl f z (x:xs) = foldl f (f z x) xs -- (f z x) is a thunk!

-- foldl' forces the accumulator (strict)

foldl' :: (b -> a -> b) -> b -> [a] -> b

foldl' f z [] = z

foldl' f z (x:xs) = let z' = f z x in z' `seq` foldl' f z' xs

Always use foldl’ for reducing to a value. Only use foldl if you have a specific reason.

Controlling Strictness

Haskell provides several tools to add strictness:

1. seq: Force to WHNF

seq :: a -> b -> b

-- Evaluates first argument to WHNF, returns second

x `seq` (x + 1) -- Forces x, then computes x + 1

2. ($!): Strict application

($!) :: (a -> b) -> a -> b

f $! x = x `seq` f x

-- Forces argument before applying function

sum $! expensive -- Computes expensive, then calls sum

3. BangPatterns: Force on pattern match

{-# LANGUAGE BangPatterns #-}

go !n = ... -- n is forced when go is called

4. Strict data fields

data Strict = Strict !Int !String

-- Fields are forced when constructor is applied

let x = Strict (2+3) "hi"

-- (2+3) is immediately evaluated to 5

5. deepseq: Force to Normal Form

import Control.DeepSeq

deepseq :: NFData a => a -> b -> b

-- Fully evaluates first argument

force :: NFData a => a -> a

force x = x `deepseq` x

Strictness Analysis

GHC performs strictness analysis to automatically add strictness where safe. It detects when:

- A value will definitely be used

- Using it earlier won’t change the program’s meaning

-- GHC can see that 'n' will be used:

factorial n = if n <= 1 then 1 else n * factorial (n-1)

-- GHC might automatically make n strict

You can see GHC’s strictness analysis with:

ghc -ddump-stranal MyModule.hs

Infinite Structures in Practice

Laziness enables elegant solutions:

1. Memoization via infinite structures

-- Fibonacci with automatic memoization

fibs :: [Integer]

fibs = 0 : 1 : zipWith (+) fibs (tail fibs)

fib :: Int -> Integer

fib n = fibs !! n -- O(n) first time, cached afterward

2. Generating primes (Sieve of Eratosthenes)

primes :: [Int]

primes = sieve [2..]

where

sieve (p:xs) = p : sieve [x | x <- xs, x `mod` p /= 0]

-- take 10 primes = [2,3,5,7,11,13,17,19,23,29]

3. Game trees

data GameTree = Node GameState [GameTree]

-- Generate the entire (possibly infinite) game tree lazily

gameTree :: GameState -> GameTree

gameTree state = Node state [gameTree s | s <- nextStates state]

-- Then prune to desired depth

prune :: Int -> GameTree -> GameTree

prune 0 (Node s _) = Node s []

prune n (Node s ts) = Node s [prune (n-1) t | t <- ts]

4. Circular/Tying-the-knot structures

data DList a = DNode

{ value :: a

, prev :: DList a

, next :: DList a

}

-- Create a circular doubly-linked list

fromList :: [a] -> DList a

fromList xs = head nodes

where

nodes = zipWith3 DNode xs (last nodes : init nodes) (tail nodes ++ [head nodes])

-- 'nodes' refers to itself! Only possible with laziness

Profiling Space Usage

GHC provides tools to diagnose space leaks:

1. Heap profiling

# Compile with profiling

ghc -prof -fprof-auto -rtsopts MyProgram.hs

# Run with heap profile

./MyProgram +RTS -hc -RTS

# Generate graph

hp2ps -c MyProgram.hp

2. Cost center profiling

./MyProgram +RTS -p -RTS

# Generates MyProgram.prof

3. EventLog for detailed analysis

ghc -eventlog MyProgram.hs

./MyProgram +RTS -l -RTS

# View with ThreadScope or ghc-events

Memory Layout of Thunks

Understanding GHC’s representation helps debug:

Thunk layout:

+------------------+

| Info pointer | -> Points to code + metadata

+------------------+

| Free variable 1 |

| Free variable 2 |

| ... |

+------------------+

After forcing:

+------------------+

| Info pointer | -> Points to constructor info

+------------------+

| Field 1 |

| Field 2 |

| ... |

+------------------+

A thunk is updated in place when forced. This is why sharing works - all pointers to the thunk now point to the value.

Haskell’s Evaluation Order in Detail

Let’s trace evaluation precisely:

take 2 (map (+1) [1, 2, 3])

Step by step:

take 2 (map (+1) [1, 2, 3])

-- take needs to pattern match on the list

-- Must force (map (+1) [1, 2, 3]) to WHNF

take 2 (map (+1) (1 : [2, 3]))

-- map (+1) pattern matches, produces constructor

take 2 ((+1) 1 : map (+1) [2, 3])

take 2 (1+1 : map (+1) [2, 3]) -- Thunk for 1+1, thunk for rest

-- take sees non-empty list

-- n=2, (y:ys) = (1+1 : map (+1) [2, 3])

y : take 1 ys

(1+1) : take 1 (map (+1) [2, 3])

-- Repeat for take 1

(1+1) : take 1 ((+1) 2 : map (+1) [3])

(1+1) : (2+1) : take 0 (map (+1) [3])

-- take 0 = []

(1+1) : (2+1) : []

-- Note: 1+1 and 2+1 are STILL thunks!

-- They're only evaluated when the list elements are needed

The Operational Semantics View

More formally, Haskell uses graph reduction:

- The expression is represented as a graph (shared structure = shared nodes)

- Reduction applies rewrite rules to the graph

- Lazy means: only reduce what’s needed for output

- Sharing means: each node is reduced at most once

Expression: let x = 2 + 3 in (x, x)

Graph representation:

(,)

/ \

x x

\ /

+

/ \

2 3

After reducing + to 5:

(,)

/ \

x x

\ /

5

Both x's point to same node - sharing!

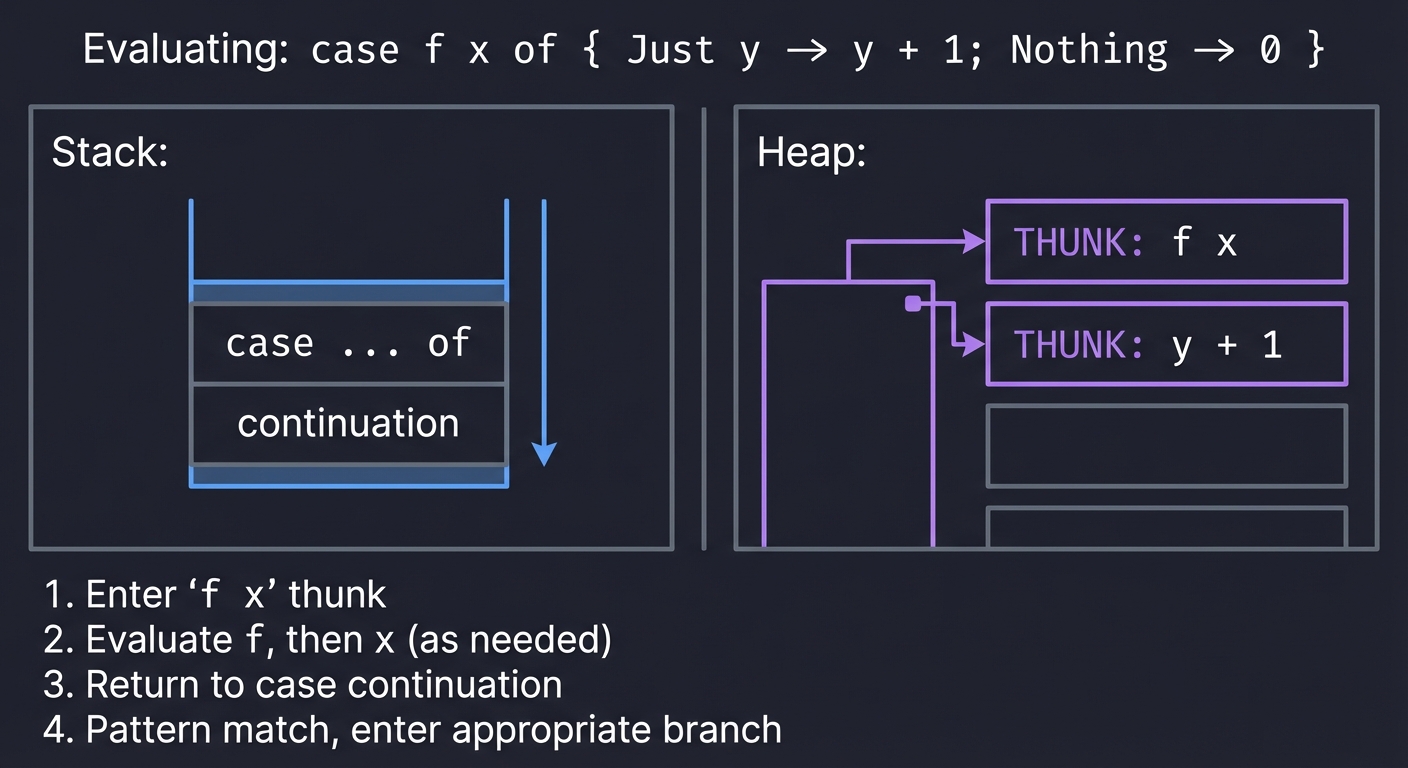

The STG Machine

GHC compiles Haskell to the Spineless Tagless G-machine (STG). Key concepts:

- Thunks are heap-allocated closures

- Forcing means entering a closure (jumping to its code)

- Updating means overwriting the thunk with its value

- The stack tracks what to do with the result

Evaluating: case f x of { Just y -> y + 1; Nothing -> 0 }

Stack: Heap:

+----------------+ +------------------+

| case ... of | | THUNK: f x |

| continuation | +------------------+

+----------------+ | THUNK: y + 1 |

+------------------+

1. Enter "f x" thunk

2. Evaluate f, then x (as needed)

3. Return to case continuation

4. Pattern match, enter appropriate branch

Project Specification

Core Requirements

Build a visualization tool that demonstrates lazy evaluation. Your tool should:

1. Thunk Visualization

- Display expressions as trees with explicit thunks

- Show which parts are evaluated (values) vs unevaluated (thunks)

- Animate the forcing process step by step

2. Evaluation Trace

- Record each reduction step

- Show which thunk is being forced

- Display the resulting expression/graph

3. Sharing Demonstration

- Visualize when multiple references share a thunk

- Show how forcing once updates all references

- Contrast with what call-by-name would do

4. Space Leak Examples

- Demonstrate thunk accumulation

- Show memory growth over time

- Compare strict vs lazy versions

5. Infinite Structure Support

- Handle infinite lists (display with “…”)

- Show how

take nfrom an infinite list works - Demonstrate cycle detection for circular structures

Implementation Options

Option A: Interpreted Language

- Design a small lazy language

- Implement a graph-reduction interpreter

- Visualize the graph and reduction steps

Option B: Haskell Instrumentation

- Use GHC’s heap profiling data

- Parse and visualize heap profiles

- Trace evaluation with Debug.Trace

Option C: Interactive Demonstrator

- Step-by-step execution mode

- User controls when to force thunks

- Shows expression tree at each step

Stretch Goals

- Implement your own strictness analyzer

- Visualize the STG machine stack and heap

- Compare different evaluation orders

- Show garbage collection effects

- Generate animated GIFs of evaluation

Solution Architecture

Option A: Lazy Interpreter Architecture

src/

Language/

Syntax.hs -- AST definition

Parser.hs -- Parse source to AST

Evaluator.hs -- Graph reduction engine

Thunk.hs -- Thunk representation

Visualization/

Graph.hs -- Expression tree to graph

Renderer.hs -- Output (text/graphviz/HTML)

Trace.hs -- Reduction step recording

Examples/

InfiniteList.hs -- Infinite structure demos

SpaceLeak.hs -- Space leak demonstrations

app/

Main.hs -- Interactive REPL or batch mode

Language Definition

A minimal lazy language:

data Expr

= Var Name -- Variable

| Lit Int -- Integer literal

| Lam Name Expr -- Lambda abstraction

| App Expr Expr -- Application

| Let Name Expr Expr -- Let binding (lazy!)

| LetRec [(Name, Expr)] Expr -- Recursive let

| If Expr Expr Expr -- Conditional

| Prim PrimOp [Expr] -- Primitive operation

| Cons Name [Expr] -- Data constructor

| Case Expr [(Pattern, Expr)] -- Pattern matching

deriving (Show, Eq)

data PrimOp = Add | Sub | Mul | Div | Eq | Lt

deriving (Show, Eq)

data Pattern

= PVar Name

| PCons Name [Pattern]

| PWild

deriving (Show, Eq)

Graph Representation

-- A node in the reduction graph

data Node

= Thunk Expr Env NodeId -- Unevaluated

| Value Value NodeId -- Evaluated

| Indirection NodeId -- Points to another node

| BlackHole NodeId -- Being evaluated (for cycle detection)

deriving (Show)

data Value

= VInt Int

| VCons Name [NodeId] -- Constructor with pointers to args

| VClosure Name Expr Env -- Lambda closure

deriving (Show)

type Env = Map Name NodeId -- Environment maps names to node IDs

type Heap = IntMap Node -- The graph/heap

data EvalState = EvalState

{ heap :: Heap

, nextId :: NodeId

, trace :: [ReductionStep]

}

data ReductionStep = ReductionStep

{ stepDescription :: String

, forcedNode :: NodeId

, beforeHeap :: Heap

, afterHeap :: Heap

}

Evaluation Engine

-- Force a node to WHNF

force :: NodeId -> State EvalState Value

force nodeId = do

node <- getNode nodeId

case node of

Value v _ -> return v

BlackHole _ -> error "Infinite loop detected!"

Indirection target -> force target

Thunk expr env _ -> do

-- Mark as being evaluated (black hole)

setNode nodeId (BlackHole nodeId)

-- Evaluate the expression

resultId <- eval expr env

result <- force resultId

-- Update the thunk with the value

setNode nodeId (Value result nodeId)

recordStep $ "Forced thunk " ++ show nodeId

return result

-- Evaluate expression, returning node ID (may be a thunk)

eval :: Expr -> Env -> State EvalState NodeId

eval (Lit n) _ = allocValue (VInt n)

eval (Var x) env = case Map.lookup x env of

Just nodeId -> return nodeId

Nothing -> error $ "Unbound variable: " ++ x

eval (Lam x body) env = allocValue (VClosure x body env)

eval (App f arg) env = do

-- Allocate thunk for argument (lazy!)

argId <- allocThunk arg env

-- Force function

fId <- eval f env

fVal <- force fId

case fVal of

VClosure x body closureEnv -> do

let env' = Map.insert x argId closureEnv

eval body env'

_ -> error "Type error: applying non-function"

eval (Let x rhs body) env = do

-- Allocate thunk for RHS (lazy!)

rhsId <- allocThunk rhs env

let env' = Map.insert x rhsId env

eval body env'

Visualization

-- Convert heap to Graphviz DOT format

heapToDot :: Heap -> String

heapToDot heap = unlines

[ "digraph Heap {"

, " node [shape=record];"

, unlines $ map nodeToDoc $ IntMap.toList heap

, "}"

]

where

nodeToDoc (nodeId, node) = case node of

Thunk expr _ _ ->

printf " n%d [label=\"THUNK|%s\" style=filled fillcolor=yellow];"

nodeId (showExpr expr)

Value (VInt n) _ ->

printf " n%d [label=\"INT|%d\" style=filled fillcolor=green];"

nodeId n

Value (VCons name args) _ ->

printf " n%d [label=\"%s|%s\"];"

nodeId name (intercalate "|" $ map showArg $ zip [0..] args)

++ unlines [printf " n%d -> n%d;" nodeId arg | arg <- args]

Indirection target ->

printf " n%d -> n%d [style=dashed];" nodeId target

BlackHole _ ->

printf " n%d [label=\"BLACK HOLE\" style=filled fillcolor=red];"

nodeId

Implementation Guide

Phase 1: Basic Evaluator

Goal: Implement a simple interpreter without laziness first.

-- Start with strict evaluation

evalStrict :: Expr -> Env -> Value

evalStrict (Lit n) _ = VInt n

evalStrict (Var x) env = env Map.! x

evalStrict (App f arg) env =

let fVal = evalStrict f env

argVal = evalStrict arg env -- Eager!

in case fVal of

VClosure x body closureEnv ->

evalStrict body (Map.insert x argVal closureEnv)

-- Test:

-- evalStrict (App (Lam "x" (Var "x")) (Lit 42)) empty

-- => VInt 42

Phase 2: Add Thunks

Goal: Convert to lazy evaluation with thunks.

-- Now arguments are thunked, not evaluated

evalLazy :: Expr -> Env -> State Heap NodeId

evalLazy (Lit n) _ = allocNode (Value (VInt n))

evalLazy (Var x) env = return (env Map.! x)

evalLazy (App f arg) env = do

fId <- evalLazy f env

argId <- allocNode (Thunk arg env) -- Don't evaluate yet!

VClosure x body closureEnv <- forceToWHNF fId

evalLazy body (Map.insert x argId closureEnv)

Phase 3: Implement Sharing

Goal: Ensure thunks are updated after forcing.

forceToWHNF :: NodeId -> State Heap Value

forceToWHNF nodeId = do

heap <- get

case IntMap.lookup nodeId heap of

Just (Value v) -> return v

Just (Thunk expr env) -> do

-- Mark black hole to detect cycles

modify $ IntMap.insert nodeId BlackHole

-- Evaluate

resultId <- evalLazy expr env

result <- forceToWHNF resultId

-- UPDATE: Replace thunk with value (sharing!)

modify $ IntMap.insert nodeId (Value result)

return result

Just BlackHole -> error "Infinite loop!"

Phase 4: Add Tracing

Goal: Record each reduction step for visualization.

data TraceEntry = TraceEntry

{ entryStep :: Int

, entryAction :: String

, entryNodeId :: NodeId

, entryBefore :: String -- Heap snapshot

, entryAfter :: String

}

forceWithTrace :: NodeId -> StateT (Heap, [TraceEntry]) IO Value

forceWithTrace nodeId = do

(heap, trace) <- get

let step = length trace + 1

-- Record before state

let before = showHeap heap

-- Do the forcing (simplified)

result <- force' nodeId

-- Record after state

(heap', _) <- get

let after = showHeap heap'

let entry = TraceEntry step "force" nodeId before after

modify $ \(h, t) -> (h, t ++ [entry])

return result

Phase 5: Visualization Output

Goal: Render the trace as text, Graphviz, or HTML.

-- Text visualization

visualizeStep :: TraceEntry -> String

visualizeStep entry = unlines

[ "Step " ++ show (entryStep entry) ++ ": " ++ entryAction entry

, "Forcing node " ++ show (entryNodeId entry)

, ""

, "Before:"

, entryBefore entry

, ""

, "After:"

, entryAfter entry

, replicate 40 '-'

]

-- Graphviz animation (one DOT file per step)

generateAnimation :: [TraceEntry] -> IO ()

generateAnimation entries = do

forM_ (zip [1..] entries) $ \(i, entry) -> do

let filename = printf "step%03d.dot" i

writeFile filename (heapToDot entry)

-- Convert to images

system "for f in step*.dot; do dot -Tpng $f -o ${f%.dot}.png; done"

-- Create animated GIF

system "convert -delay 100 step*.png animation.gif"

Phase 6: Infinite Structures

Goal: Handle infinite lists and demonstrate termination.

-- Language support for infinite lists

-- ones = 1 : ones

onesExpr :: Expr

onesExpr = LetRec

[("ones", Cons "Cons" [Lit 1, Var "ones"])]

(Var "ones")

-- take 3 ones

takeExpr :: Expr

takeExpr = App (App (Var "take") (Lit 3)) onesExpr

-- Visualization shows:

-- Step 1: Allocate ones = Thunk(Cons 1 ones)

-- Step 2: force take, force n=3, force list

-- Step 3: Cons pattern match, force head (1)

-- Step 4: recursive call with n-1=2

-- ... stops after 3 elements

Phase 7: Space Leak Demonstration

Goal: Show thunk accumulation visually.

-- Naive sum that leaks

sumExpr :: [Int] -> Expr

sumExpr ns = foldr (\n acc -> Prim Add [Lit n, acc]) (Lit 0) ns

-- Run on [1..100], show thunk chain building up:

-- (1 + (2 + (3 + ... (99 + (100 + 0))...)))

--

-- Visualization: Chain of 100 thunks before any addition!

-- Fixed version with strict accumulator

sumStrictExpr :: Expr

sumStrictExpr = App (Var "sumStrict") (list [1..100])

-- Visualization: Only 1 accumulator thunk at a time

Testing Strategy

Unit Tests

-- Test thunk creation

testThunkCreation :: Spec

testThunkCreation = describe "Thunk allocation" $ do

it "creates thunk for let binding" $ do

let expr = Let "x" (Prim Add [Lit 1, Lit 2]) (Var "x")

(_, heap) <- runEval expr

-- x should be a thunk until forced

let xNode = heap IntMap.! 1

xNode `shouldSatisfy` isThunk

it "does not evaluate unused bindings" $ do

let expr = Let "x" (error "should not evaluate") (Lit 42)

result <- runEval expr

result `shouldBe` VInt 42

-- Test sharing

testSharing :: Spec

testSharing = describe "Sharing" $ do

it "evaluates shared binding only once" $ do

let expr = Let "x" (trace "evaluating" (Lit 42))

(Prim Add [Var "x", Var "x"])

output <- capture $ runEval expr

-- "evaluating" should appear exactly once

count "evaluating" output `shouldBe` 1

-- Test infinite structures

testInfinite :: Spec

testInfinite = describe "Infinite structures" $ do

it "can take from infinite list" $ do

let ones = LetRec [("ones", Cons "Cons" [Lit 1, Var "ones"])]

(Var "ones")

let expr = App (App (Var "take") (Lit 5)) ones

result <- runEval expr

result `shouldBe` VList [1, 1, 1, 1, 1]

-- Test space usage

testSpaceLeak :: Spec

testSpaceLeak = describe "Space leaks" $ do

it "naive sum accumulates thunks" $ do

let expr = sumNaive [1..1000]

(_, heap) <- runEvalWithHeap expr

-- Before final reduction, heap should have ~1000 thunks

length (filter isThunk $ IntMap.elems heap) `shouldBeGreaterThan` 900

it "strict sum has constant space" $ do

let expr = sumStrict [1..1000]

maxHeapDuring <- runEvalMeasuringMaxHeap expr

-- Should never exceed a small constant

maxHeapDuring `shouldBeLessThan` 10

Property-Based Tests

-- Lazy and strict evaluation should give same result

prop_lazyEqualsStrict :: Expr -> Property

prop_lazyEqualsStrict expr =

terminates expr ==>

evalLazy expr === evalStrict expr

-- Sharing: evaluating same expression twice uses result once

prop_sharing :: Expr -> Property

prop_sharing expr =

let doubled = Let "x" expr (pair (Var "x") (Var "x"))

evalCount = countEvaluations doubled

in evalCount <= 1 + countEvaluations expr

Common Pitfalls

Pitfall 1: Confusing WHNF with NF

Problem: Thinking Just (2+3) is fully evaluated.

-- This is in WHNF (Just constructor exposed)

x = Just (2+3)

-- But (2+3) is still a thunk!

-- Only NF would have: Just 5

Demonstration: In your visualizer, show that pattern matching on Just x doesn’t force x.

Pitfall 2: Forgetting About Accumulator Strictness

Problem: Using foldl instead of foldl'.

-- WRONG: Accumulates thunks

sum = foldl (+) 0

-- CORRECT: Forces accumulator each step

sum = foldl' (+) 0

Demonstration: Show the thunk chain for foldl (+) 0 [1..100].

Pitfall 3: Lazy I/O Pitfalls

Problem: File handles closed before data is read.

-- WRONG: File closed before lazy string is consumed!

readFile' path = do

h <- openFile path ReadMode

contents <- hGetContents h -- Returns lazy string

hClose h -- Oops! Contents not read yet

return contents

Solution: Use strict I/O or ensure full evaluation before closing.

import qualified Data.ByteString as BS

-- Strict:

contents <- BS.readFile path

-- Or force evaluation:

contents <- hGetContents h

length contents `seq` hClose h

return contents

Pitfall 4: Thinking seq Fully Evaluates

Problem: seq only goes to WHNF.

-- This doesn't fully evaluate the list!

xs `seq` useList xs

-- xs = [1+1, 2+2, 3+3]

-- After seq: xs is (:) applied to thunks

-- Elements are still thunks!

Solution: Use deepseq for full evaluation.

import Control.DeepSeq

xs `deepseq` useList xs

-- Now all elements are evaluated

Pitfall 5: CAFs and Unexpected Retention

Problem: Top-level values (Constant Applicative Forms) are never garbage collected.

-- This infinite list is NEVER garbage collected!

primes :: [Int]

primes = sieve [2..]

-- Every prime ever computed is kept forever

Solution: Make functions that compute on demand, or use weak references.

Extensions and Challenges

Extension 1: Implement Strictness Analysis

Build an analyzer that determines which function arguments will definitely be evaluated:

data Demand = Lazy | Strict | HyperStrict

analyzeStrictness :: Expr -> Map Name Demand

-- For example:

-- f x y = x + y

-- Analysis: x -> Strict, y -> Strict

-- g x y = if condition then x else y

-- Analysis: x -> Lazy, y -> Lazy (might not be evaluated)

Extension 2: STG Machine Simulator

Implement the Spineless Tagless G-machine:

- Stack for continuations

- Heap for closures

- Info tables for code pointers

- Update frames for thunk updates

This is how GHC actually executes Haskell!

Extension 3: Parallel Evaluation Strategies

Implement parallel evaluation primitives:

par :: a -> b -> b -- Spark first argument for parallel eval

pseq :: a -> b -> b -- Sequential eval (like seq)

-- Example: parallel map

parMap :: (a -> b) -> [a] -> [b]

parMap f [] = []

parMap f (x:xs) = fx `par` (fxs `pseq` (fx : fxs))

where

fx = f x

fxs = parMap f xs

Extension 4: Compare Evaluation Strategies

Implement all three strategies in your interpreter:

- Call-by-value (strict)

- Call-by-name (no sharing)

- Call-by-need (lazy with sharing)

Compare step counts and memory usage on the same expressions.

Extension 5: Optimizations

Implement GHC-style optimizations:

- Let floating

- Inlining

- Strictness-based worker/wrapper transformation

- Case-of-case

Real-World Connections

Where Laziness Shines

- Stream Processing: Process data that doesn’t fit in memory

-- Process a 10GB log file in constant memory

main = do

contents <- readFile "huge.log"

let errors = filter isError (lines contents)

mapM_ putStrLn (take 100 errors)

- Embedded DSLs: Build complex queries/computations without executing

-- Build a query, optimize it, then execute

let query = select users

& where_ (\u -> u.age > 18)

& orderBy (\u -> u.name)

& limit 10

-- 'query' is just a data structure until we run it

execute query

- Control Flow: Custom control structures

-- 'unless' only evaluates its body when condition is false

unless :: Bool -> IO () -> IO ()

unless True _ = return ()

unless False action = action

-- Works because 'action' is lazy

unless True (launchMissiles) -- Missiles NOT launched

Where Laziness Hurts

- Unpredictable performance: Hard to know when work happens

- Space leaks: Require careful attention to strictness

- Debugging: Stack traces don’t show where thunk was created

- I/O ordering: Need explicit sequencing for effects

Industry Uses

- Pandoc: Document converter uses laziness for streaming

- Xmonad: Window manager uses lazy configuration

- Yesod/Servant: Web frameworks use lazy text processing

- Compilers: Lazy abstract syntax trees for large codebases

Interview Questions

After completing this project, you should be able to answer:

- “What is the difference between call-by-value, call-by-name, and call-by-need?”

- CBV: Evaluate arguments before calling

- CBN: Substitute expressions, may re-evaluate

- CBN: Like CBN but cache results (sharing)

- “What is a thunk and how is it represented in memory?”

- Suspended computation: code pointer + free variables

- Updated in place when forced

- Becomes indirection then value

- “What is Weak Head Normal Form? Give examples.”

- Outermost constructor or lambda exposed

Just (1+2)is WHNF,1+2is not- Pattern matching forces to WHNF

- “How would you diagnose a space leak in Haskell?”

- Heap profiling with

-hcor-hd - Look for thunk accumulation

- Check for lazy accumulators, lazy I/O

- Heap profiling with

- “When would you use

seqvsdeepseq?”seqfor WHNF (one level)deepseqfor full evaluationseqfor strictness,deepseqfor data that must be fully computed

- “How do infinite data structures work with lazy evaluation?”

- Only compute what’s demanded

- Store computed prefix + thunk for rest

- Enable elegant algorithms (primes sieve, fibonacci)

- “Why is foldl’ often better than foldl?”

foldlbuilds thunk chainfoldl'forces accumulator each step- Constant vs linear space

Self-Assessment Checklist

Core Understanding

- I can explain call-by-need with an example

- I understand what a thunk contains

- I can identify if an expression is in WHNF

- I know when

seqforces vs when it doesn’t

Practical Skills

- I can write space-efficient folds

- I can use BangPatterns appropriately

- I can create and use infinite data structures

- I can profile and fix space leaks

Implementation

- I have implemented a simple lazy evaluator

- My evaluator demonstrates sharing

- I can visualize thunk forcing

- I can detect infinite loops (black holes)

Advanced Topics

- I understand GHC’s strictness analysis

- I know how the STG machine works at a high level

- I can explain when laziness helps vs hurts performance

- I can make informed decisions about strict vs lazy data structures

Resources

Books

| Book | Chapter | What You’ll Learn |

|---|---|---|

| “Haskell in Depth” (Bragilevsky) | Chapter 4 | Laziness, strictness, evaluation |

| “Real World Haskell” (O’Sullivan et al.) | Chapter 25 | Profiling and optimization |

| “Parallel and Concurrent Programming in Haskell” (Marlow) | Chapters 2-3 | Evaluation and parallelism |

| “The Implementation of Functional Programming Languages” (SPJ) | Full book | How lazy evaluation is implemented |

Papers

- “The Spineless Tagless G-Machine” by Simon Peyton Jones

- GHC’s abstract machine

- “Making a Fast Curry” by Simon Marlow & Simon Peyton Jones

- Function application in GHC

- “A Natural Semantics for Lazy Evaluation” by Launchbury

- Formal semantics of call-by-need

Online Resources

- GHC Commentary: Evaluation

- 24 Days of GHC Extensions: Bang Patterns

- Haskell Wiki: Memory Leak

- Haskell Wiki: Weak Head Normal Form

Tools

- GHC profiling:

-prof -fprof-auto -rtsopts - hp2ps/hp2any: Heap profile visualization

- ThreadScope: Parallel/concurrent execution visualization

- ghc-vis: Live visualization of Haskell data structures

Conclusion

Lazy evaluation is both Haskell’s superpower and its greatest source of confusion. By building a lazy evaluation demonstrator, you’ve learned:

- How thunks work - Suspended computations that update in place

- The importance of sharing - Why call-by-need is efficient

- WHNF and forcing - When and how evaluation happens

- Space leaks - How to diagnose and fix them

- Infinite structures - What laziness makes possible

You can now write efficient Haskell code, debug performance issues, and explain evaluation behavior to others.

Next Steps:

- Project 9: Monad Transformers - Stack effects to build complex programs

- Project 10: Property-Based Testing - QuickCheck and beyond