Functional Programming & Lambda Calculus with Haskell

A Project-Based Deep Dive into the Foundations of Computation

Goal

Build a precise mental model of computation by implementing lambda calculus in Haskell, then grow that model into a full functional toolkit: typed abstractions, evaluation strategies, and practical encodings you can apply to real-world program design.

Overview

Lambda calculus is not just a programming technique—it’s the mathematical theory of computation itself. Created by Alonzo Church in the 1930s, it predates computers and proved that functions alone are sufficient to express any computation.

Haskell is the purest practical embodiment of these ideas. Unlike languages that bolt on functional features, Haskell is lambda calculus extended with a type system, lazy evaluation, and syntactic sugar.

Why This Matters

Understanding lambda calculus and functional programming transforms how you think about code:

- From “how” to “what”: Describe the result, not the steps

- From mutation to transformation: Data flows through functions

- From side effects to purity: Functions are predictable, testable, composable

- From runtime errors to compile-time proofs: The type system catches errors before execution

Core Concepts You’ll Master

| Concept Area | What You’ll Understand |

|---|---|

| Lambda Calculus | Variables, abstraction, application, reduction, Church encodings, fixed points |

| Type Systems | Hindley-Milner inference, algebraic data types, parametric polymorphism |

| Higher-Order Functions | Functions as values, currying, composition, point-free style |

| Laziness | Thunks, infinite data structures, call-by-need evaluation |

| Type Classes | Ad-hoc polymorphism, Functor, Applicative, Monad, and beyond |

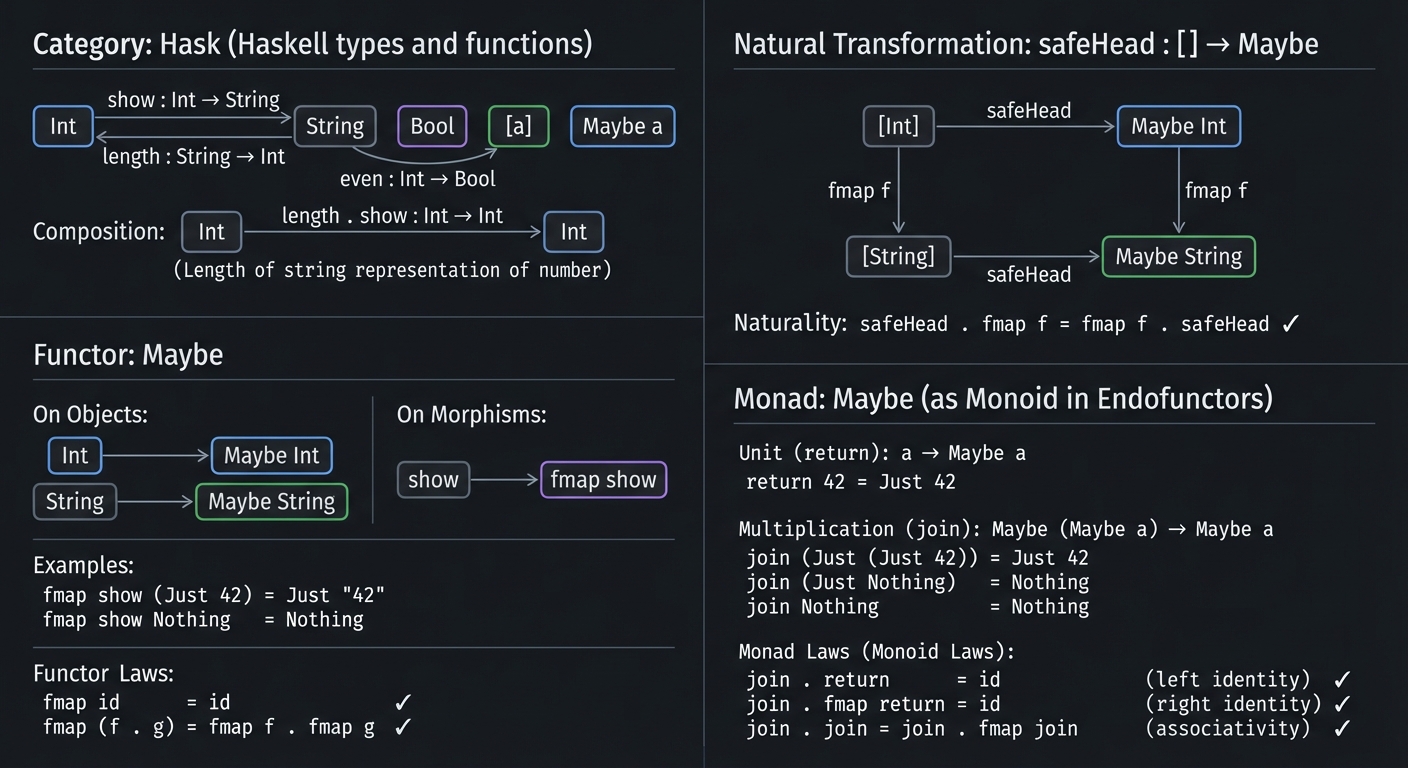

| Category Theory | Functors, natural transformations, monads as mathematical objects |

| Effects | IO, State, Reader, Writer, monad transformers |

| Advanced Types | GADTs, type families, dependent types (via singletons) |

Concept Summary Table

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize |

|---|---|

| Lambda calculus syntax | Variables, abstraction, application, alpha-equivalence, substitution. |

| Evaluation strategies | Normal order vs applicative order, confluence, termination tradeoffs. |

| Encodings as data | Booleans, numerals, pairs, lists as pure functions. |

| Fixed points & recursion | Y combinator, recursion without names, self-application. |

| Types and inference | Hindley-Milner inference, polymorphism, ADTs. |

| Laziness | Thunks, sharing, infinite structures, call-by-need semantics. |

| Type classes | Functor/Applicative/Monad as compositional interfaces. |

| Effects modeling | IO and state as explicit, composable effects. |

Deep Dive Reading by Concept

Lambda Calculus Core

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Syntax, substitution, alpha/beta | Types and Programming Languages by Benjamin Pierce — Ch. 5: “The Untyped Lambda-Calculus” |

| Church encodings | Introduction to Functional Programming by Richard Bird — Ch. 2: “Equational Reasoning” |

Evaluation & Semantics

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Normal order vs applicative order | Programming in Haskell, 2nd Edition by Graham Hutton — Ch. 15: “Lazy Evaluation” |

| Confluence and normal forms | The Lambda Calculus: Its Syntax and Semantics by Henk Barendregt — Ch. 6: “Reduction” |

Types & Abstractions

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Hindley-Milner inference | Types and Programming Languages — Ch. 22: “Type Reconstruction” |

| Type classes | Haskell Programming from First Principles — Ch. 16: “Functor”, Ch. 17: “Applicative”, Ch. 18: “Monad” |

Effects in Haskell

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| IO and purity boundary | Real World Haskell — Ch. 8: “IO” |

| Monads as effect modeling | Learn You a Haskell for Great Good! — Ch. 12: “A Fistful of Monads” |

Project 1: Pure Lambda Calculus Interpreter

- File: FUNCTIONAL_PROGRAMMING_LAMBDA_CALCULUS_HASKELL_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: Haskell

- Alternative Programming Languages: OCaml, Racket, Rust

- Coolness Level: Level 5: Pure Magic (Super Cool)

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold” (Educational/Personal Brand)

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Programming Language Theory / Lambda Calculus

- Software or Tool: Lambda Interpreter

- Main Book: “Haskell Programming from First Principles” by Christopher Allen and Julie Moronuki

What you’ll build

An interpreter for the untyped lambda calculus that parses lambda expressions, performs alpha-renaming, and reduces to normal form using different evaluation strategies (normal order, applicative order).

Why it teaches Lambda Calculus

Lambda calculus has only three constructs: variables (x), abstraction (λx.e), and application (e₁ e₂). By implementing an interpreter, you’ll see that these three things are sufficient to express any computation—numbers, booleans, loops, recursion—everything emerges from function application.

Core challenges you’ll face

- Parsing lambda syntax (handling nested abstractions and applications) → maps to syntax of lambda calculus

- Free vs bound variables (tracking variable scope) → maps to variable binding

- Alpha-renaming (avoiding variable capture) → maps to substitution correctness

- Beta-reduction (applying functions to arguments) → maps to computation itself

- Reduction strategies (which redex to reduce first) → maps to evaluation order

Key Concepts

- Lambda Calculus Syntax: A Tutorial Introduction to the Lambda Calculus (PDF) - Raúl Rojas

- Reduction Strategies: “Types and Programming Languages” Chapter 5 - Benjamin Pierce

- Substitution: Stanford CS 242: Lambda Calculus

- Parsing in Haskell: “Programming in Haskell” Chapter 13 - Graham Hutton

Difficulty

Advanced

Time estimate

2-3 weeks

Prerequisites

Basic Haskell syntax, understanding of recursion

Real world outcome

λ> (\x. \y. x) a b

Parsing: App (App (Lam "x" (Lam "y" (Var "x"))) (Var "a")) (Var "b")

Reduction trace (normal order):

(λx. λy. x) a b

→ (λy. a) b -- β-reduce: x := a

→ a -- β-reduce: y := b (y not used)

Normal form: a

λ> (\x. x x) (\x. x x)

WARNING: No normal form (diverges)

(λx. x x) (λx. x x)

→ (λx. x x) (λx. x x)

→ (λx. x x) (λx. x x)

→ ... (infinite loop)

λ> (\f. \x. f (f x)) (\y. y) z

Reduction trace:

(λf. λx. f (f x)) (λy. y) z

→ (λx. (λy. y) ((λy. y) x)) z

→ (λy. y) ((λy. y) z)

→ (λy. y) z

→ z

Normal form: z

Implementation Hints

Start with the data type for lambda terms:

Pseudo-Haskell:

data Term

= Var String -- Variable: x

| Lam String Term -- Abstraction: λx. e

| App Term Term -- Application: e₁ e₂

-- Free variables in a term

freeVars :: Term -> Set String

freeVars (Var x) = singleton x

freeVars (Lam x e) = delete x (freeVars e)

freeVars (App e1 e2) = union (freeVars e1) (freeVars e2)

-- Substitution: e[x := s] (replace x with s in e)

subst :: String -> Term -> Term -> Term

subst x s (Var y)

| x == y = s

| otherwise = Var y

subst x s (App e1 e2) = App (subst x s e1) (subst x s e2)

subst x s (Lam y e)

| x == y = Lam y e -- x is bound, no substitution

| y `notIn` freeVars s = Lam y (subst x s e) -- safe to substitute

| otherwise = -- need alpha-rename y first!

let y' = freshVar y (freeVars s `union` freeVars e)

in Lam y' (subst x s (subst y (Var y') e))

-- Beta reduction: (λx. e) s → e[x := s]

betaReduce :: Term -> Maybe Term

betaReduce (App (Lam x e) s) = Just (subst x s e)

betaReduce _ = Nothing

-- Normal order reduction (reduce leftmost-outermost redex first)

normalOrder :: Term -> Term

normalOrder term = case betaReduce term of

Just reduced -> normalOrder reduced

Nothing -> case term of

App e1 e2 -> let e1' = normalOrder e1

in if e1' /= e1 then App e1' e2

else App e1 (normalOrder e2)

Lam x e -> Lam x (normalOrder e)

_ -> term

Learning milestones

- Parser handles nested abstractions → You understand lambda syntax

- Substitution avoids capture → You understand variable binding

- Beta reduction works → You understand computation

- Different strategies give same normal forms → You understand Church-Rosser theorem

Project 2: Church Encodings - Numbers, Booleans, and Data from Nothing

- File: FUNCTIONAL_PROGRAMMING_LAMBDA_CALCULUS_HASKELL_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: Haskell

- Alternative Programming Languages: Racket, OCaml, JavaScript (for comparison)

- Coolness Level: Level 5: Pure Magic (Super Cool)

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold” (Educational/Personal Brand)

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Lambda Calculus / Church Encodings

- Software or Tool: Church Encoding Library

- Main Book: “Learn You a Haskell for Great Good!” by Miran Lipovača

What you’ll build

Implement Church numerals, Church booleans, Church pairs, and Church lists—representing data entirely as functions. Then build arithmetic (addition, multiplication, exponentiation), conditionals, and recursion using only lambda abstractions.

Why it teaches Lambda Calculus

This is the “magic trick” of lambda calculus: data is just patterns of function application. The number 3 is “apply a function 3 times.” True is “select the first of two options.” A pair is “given a selector, apply it to two values.” Once you see this, you understand that functions are sufficient for everything.

Core challenges you’ll face

- Church numerals (representing N as λf.λx. f(f(…f(x)))) → maps to data as functions

- Church booleans (True = λt.λf. t, False = λt.λf. f) → maps to control flow as selection

- Predecessor function (Kleene’s trick—famously difficult!) → maps to encoding complexity

- Church pairs and lists → maps to data structures as functions

- Y combinator for recursion → maps to fixed points

Key Concepts

- Church Encodings: Learn X in Y Minutes - Lambda Calculus

- Church Numerals: “Types and Programming Languages” Chapter 5 - Benjamin Pierce

- Y Combinator: Programming with Lambda Calculus

Difficulty

Advanced

Time estimate

1-2 weeks

Prerequisites

Project 1 (Lambda interpreter)

Real world outcome

-- In your Haskell library:

λ> let three = church 3

λ> let five = church 5

λ> unchurch (add three five)

8

λ> unchurch (mult three five)

15

λ> unchurch (power (church 2) (church 10))

1024

λ> unchurch (pred (church 7))

6

λ> let myList = cons (church 1) (cons (church 2) (cons (church 3) nil))

λ> unchurch (head myList)

1

λ> unchurch (head (tail myList))

2

λ> unchurch (factorial (church 5)) -- Using Y combinator!

120

Implementation Hints

Church numerals represent N as “apply f, N times, to x”:

Pseudo-Haskell (using Rank2Types for proper typing):

-- Church numeral: applies f to x, n times

-- zero = λf. λx. x

-- one = λf. λx. f x

-- two = λf. λx. f (f x)

-- three = λf. λx. f (f (f x))

type Church = forall a. (a -> a) -> a -> a

zero :: Church

zero = \f x -> x

succ' :: Church -> Church

succ' n = \f x -> f (n f x)

-- Convert Int to Church

church :: Int -> Church

church 0 = zero

church n = succ' (church (n - 1))

-- Convert Church to Int

unchurch :: Church -> Int

unchurch n = n (+1) 0

-- Addition: m + n = apply f, m+n times

add :: Church -> Church -> Church

add m n = \f x -> m f (n f x)

-- Multiplication: m * n = apply (apply f n times), m times

mult :: Church -> Church -> Church

mult m n = \f -> m (n f)

-- Power: m^n = apply multiplication by m, n times

power :: Church -> Church -> Church

power m n = n m

-- The predecessor is HARD! (Kleene's trick)

-- Idea: pair up (prev, current), iterate, extract prev

pred' :: Church -> Church

pred' n = \f x ->

-- Build (0, 0), then (0, f(0)), then (f(0), f(f(0))), ...

-- After n steps: (f^(n-1)(x), f^n(x))

fst' (n (\p -> pair (snd' p) (f (snd' p))) (pair x x))

-- Church booleans

type ChurchBool = forall a. a -> a -> a

true :: ChurchBool

true = \t f -> t

false :: ChurchBool

false = \t f -> f

if' :: ChurchBool -> a -> a -> a

if' b t f = b t f

-- Church pairs

pair :: a -> b -> ((a -> b -> c) -> c)

pair x y = \f -> f x y

fst' :: ((a -> b -> a) -> a) -> a

fst' p = p (\x y -> x)

snd' :: ((a -> b -> b) -> b) -> b

snd' p = p (\x y -> y)

Learning milestones

- Arithmetic works on Church numerals → You understand encoding

- Predecessor works → You understand Kleene’s insight

- Church lists work → You understand data structures as functions

- Factorial using Y combinator → You understand recursion without names

Project 3: Reduction Visualizer

- File: FUNCTIONAL_PROGRAMMING_LAMBDA_CALCULUS_HASKELL_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: Haskell

- Alternative Programming Languages: Elm, PureScript, Racket

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 2. The “Micro-SaaS / Pro Tool”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Lambda Calculus / Evaluation

- Software or Tool: Step-by-Step Reducer

- Main Book: “Types and Programming Languages” by Benjamin Pierce

What you’ll build

A visual/interactive tool that shows beta-reduction step-by-step, highlighting the redex being reduced, showing variable substitutions, and allowing the user to choose which redex to reduce (exploring different reduction orders).

Why it teaches Lambda Calculus

Seeing reduction happen step-by-step makes the abstract concrete. You’ll understand why different reduction strategies matter, what the Church-Rosser theorem means in practice, and how infinite loops (non-termination) arise.

Core challenges you’ll face

- Identifying all redexes (finding all places where reduction can happen) → maps to reduction locations

- Highlighting substitution (showing what gets replaced) → maps to substitution visualization

- Step-by-step control (pause, step, choose redex) → maps to interactive exploration

- Detecting loops (recognizing non-terminating reductions) → maps to termination

Key Concepts

- Reduction Strategies: “Types and Programming Languages” Chapter 5 - Pierce

- Church-Rosser Theorem: Normal forms are unique (if they exist)

- Normal Order: Always finds normal form if it exists

- Applicative Order: May loop even when normal form exists

Difficulty

Advanced

Time estimate

1-2 weeks

Prerequisites

Project 1, basic terminal/web UI

Real world outcome

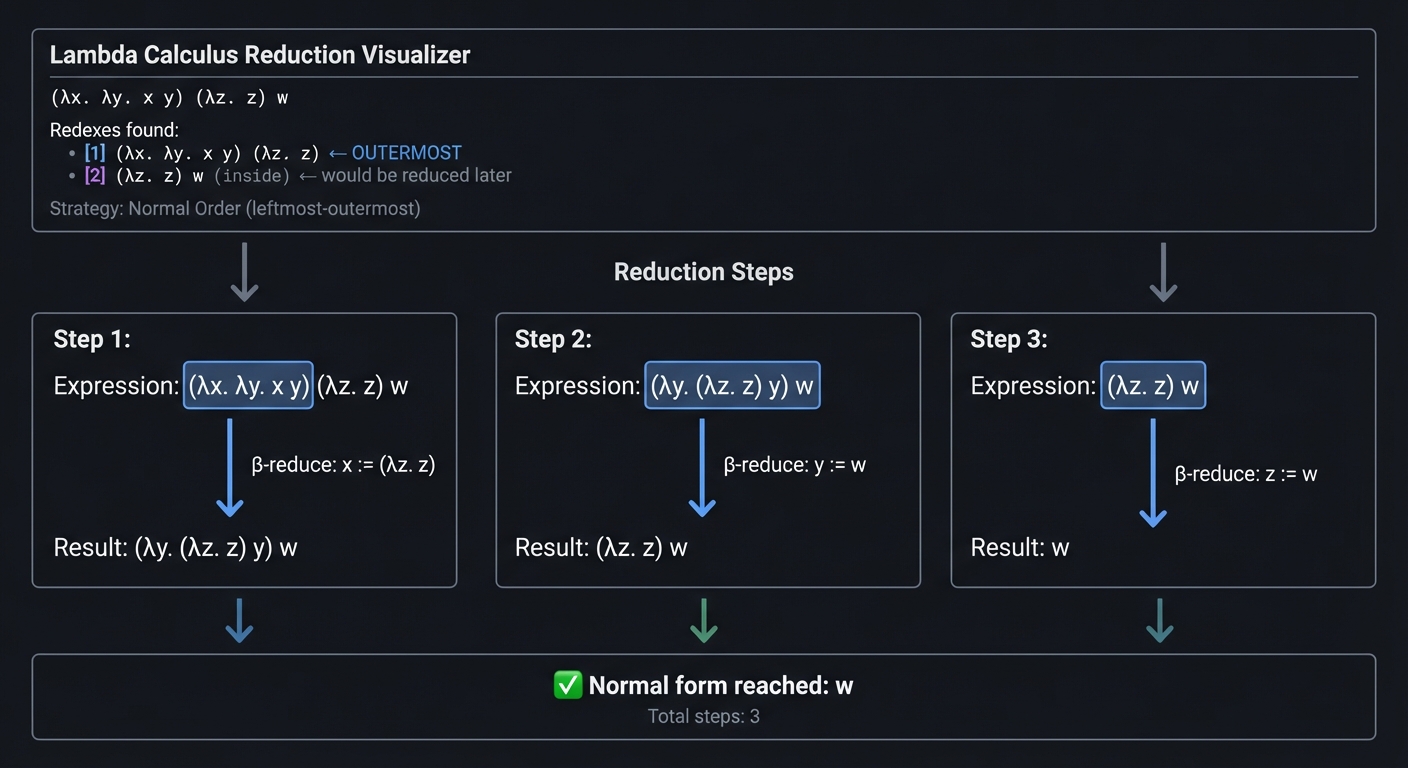

╔══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╗

║ Lambda Calculus Reduction Visualizer ║

╠══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╣

║ Expression: (λx. λy. x y) (λz. z) w ║

║ ║

║ Redexes found: ║

║ [1] (λx. λy. x y) (λz. z) ← OUTERMOST ║

║ [2] (λz. z) w (inside) ← would be reduced later ║

║ ║

║ Strategy: Normal Order (leftmost-outermost) ║

╠══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╣

║ Step 1: ║

║ (λx. λy. x y) (λz. z) w ║

║ └──────────┬────────┘ ║

║ ↓ β-reduce: x := (λz. z) ║

║ (λy. (λz. z) y) w ║

║ ║

║ Step 2: ║

║ (λy. (λz. z) y) w ║

║ └──────────┬─────┘ ║

║ ↓ β-reduce: y := w ║

║ (λz. z) w ║

║ ║

║ Step 3: ║

║ (λz. z) w ║

║ └───┬───┘ ║

║ ↓ β-reduce: z := w ║

║ w ║

║ ║

║ ✓ Normal form reached: w ║

║ Total steps: 3 ║

╚══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╝

Implementation Hints

Key is to find all redexes and tag them with their position:

Pseudo-Haskell:

-- A path through the term tree

data Path = Here | GoLeft Path | GoRight Path | GoBody Path

-- Find all redexes and their paths

findRedexes :: Term -> [(Path, Term)]

findRedexes term = case term of

App (Lam x body) arg ->

(Here, term) :

map (first GoLeft) (findRedexes (Lam x body)) ++

map (first GoRight) (findRedexes arg)

App e1 e2 ->

map (first GoLeft) (findRedexes e1) ++

map (first GoRight) (findRedexes e2)

Lam x body ->

map (first GoBody) (findRedexes body)

Var _ -> []

-- Reduce at a specific path

reduceAt :: Path -> Term -> Term

reduceAt Here (App (Lam x body) arg) = subst x arg body

reduceAt (GoLeft p) (App e1 e2) = App (reduceAt p e1) e2

reduceAt (GoRight p) (App e1 e2) = App e1 (reduceAt p e2)

reduceAt (GoBody p) (Lam x body) = Lam x (reduceAt p body)

-- Normal order: reduce leftmost-outermost first

normalOrderStep :: Term -> Maybe Term

normalOrderStep term =

case findRedexes term of

[] -> Nothing

((path, _):_) -> Just (reduceAt path term) -- first = leftmost-outermost

Learning milestones

- Can find all redexes → You understand reduction locations

- User can choose which to reduce → You understand strategies are choices

- Same expression, different paths, same result → You understand Church-Rosser

- Detects omega (infinite loop) → You understand non-termination

Project 4: Simply Typed Lambda Calculus + Type Inference

- File: FUNCTIONAL_PROGRAMMING_LAMBDA_CALCULUS_HASKELL_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: Haskell

- Alternative Programming Languages: OCaml, Rust, Scala

- Coolness Level: Level 5: Pure Magic (Super Cool)

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold” (Educational/Personal Brand)

- Difficulty: Level 4: Expert

- Knowledge Area: Type Theory / Type Inference

- Software or Tool: Hindley-Milner Type Checker

- Main Book: “Types and Programming Languages” by Benjamin Pierce

What you’ll build

Extend your lambda calculus interpreter with types: a type checker for the simply typed lambda calculus, then Hindley-Milner type inference with let-polymorphism.

Why it teaches Type Systems

Haskell’s type system is built on Hindley-Milner inference. By implementing it yourself, you’ll understand how the compiler figures out types, why polymorphism works, and what those type error messages really mean.

Core challenges you’ll face

- Type representation (function types, type variables) → maps to type syntax

- Type checking (given a type, verify the term has it) → maps to type verification

- Unification (finding substitutions that make types equal) → maps to constraint solving

- Generalization/Instantiation (let-polymorphism) → maps to polymorphic types

Key Concepts

- Simply Typed Lambda Calculus: “Types and Programming Languages” Chapters 9-11 - Pierce

- Hindley-Milner: “Types and Programming Languages” Chapter 22 - Pierce

- Algorithm W: Wikipedia: Hindley-Milner

- Unification: “The Art of Prolog” Chapter 3 - Sterling & Shapiro

Difficulty

Expert

Time estimate

3-4 weeks

Prerequisites

Project 1, understanding of substitution

Real world outcome

λ> :type \x -> x

Inferred type: a -> a

λ> :type \f -> \x -> f (f x)

Inferred type: (a -> a) -> a -> a

λ> :type \f -> \g -> \x -> f (g x)

Inferred type: (b -> c) -> (a -> b) -> a -> c

λ> let id = \x -> x in (id 1, id True)

Inferred type: (Int, Bool)

-- Note: id is polymorphic, used at both Int and Bool!

λ> :type \x -> x x

Type error: Cannot unify 'a' with 'a -> b'

(Occurs check failed - infinite type)

λ> :type \f -> \x -> f x x

Inferred type: (a -> a -> b) -> a -> b

Implementation Hints

The key insight: type inference generates constraints, then solves them via unification.

Pseudo-Haskell:

data Type

= TVar String -- Type variable: a, b, c

| TArrow Type Type -- Function type: a -> b

| TInt | TBool -- Base types

data Scheme = Forall [String] Type -- Polymorphic type: ∀a. a -> a

-- Unification: find substitution making two types equal

unify :: Type -> Type -> Either TypeError Substitution

unify (TVar a) t = bindVar a t

unify t (TVar a) = bindVar a t

unify (TArrow a1 a2) (TArrow b1 b2) = do

s1 <- unify a1 b1

s2 <- unify (apply s1 a2) (apply s1 b2)

return (compose s2 s1)

unify TInt TInt = return empty

unify TBool TBool = return empty

unify t1 t2 = Left (CannotUnify t1 t2)

bindVar :: String -> Type -> Either TypeError Substitution

bindVar a (TVar b) | a == b = return empty

bindVar a t | a `occursIn` t = Left (InfiniteType a t) -- Occurs check!

bindVar a t = return (singleton a t)

-- Algorithm W: infer type of term in environment

infer :: Env -> Term -> Infer (Substitution, Type)

infer env (Var x) =

case lookup x env of

Just scheme -> do

t <- instantiate scheme -- Replace ∀-bound vars with fresh vars

return (empty, t)

Nothing -> throwError (UnboundVariable x)

infer env (Lam x body) = do

a <- freshTypeVar

(s, t) <- infer (extend x (Forall [] a) env) body

return (s, TArrow (apply s a) t)

infer env (App e1 e2) = do

(s1, t1) <- infer env e1

(s2, t2) <- infer (apply s1 env) e2

a <- freshTypeVar

s3 <- unify (apply s2 t1) (TArrow t2 a)

return (compose s3 (compose s2 s1), apply s3 a)

infer env (Let x e1 e2) = do

(s1, t1) <- infer env e1

let scheme = generalize (apply s1 env) t1 -- Polymorphism!

(s2, t2) <- infer (extend x scheme (apply s1 env)) e2

return (compose s2 s1, t2)

Learning milestones

- Type checking works → You understand type verification

- Unification solves constraints → You understand type equations

- Occurs check catches infinite types → You understand termination

- Let-polymorphism works → You understand generalization

Project 5: Algebraic Data Types and Pattern Matching

- File: FUNCTIONAL_PROGRAMMING_LAMBDA_CALCULUS_HASKELL_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: Haskell

- Alternative Programming Languages: OCaml, Rust, Scala

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold” (Educational/Personal Brand)

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Functional Programming / Data Types

- Software or Tool: ADT Library

- Main Book: “Haskell Programming from First Principles” by Christopher Allen and Julie Moronuki

What you’ll build

Implement core Haskell data types from scratch: Maybe, Either, List, Tree, along with all their associated functions. Understand sums, products, recursive types, and exhaustive pattern matching.

Why it teaches Functional Programming

Algebraic Data Types are the way to model data in functional programming. Understanding that types are built from sums (OR) and products (AND), and that pattern matching is structural recursion, is fundamental to thinking functionally.

Core challenges you’ll face

- Sum types (Either, Maybe - one of several alternatives) → maps to tagged unions

- Product types (tuples, records - all fields together) → maps to structs

- Recursive types (List, Tree - types containing themselves) → maps to inductive definitions

- Pattern matching (destructuring and dispatch) → maps to structural recursion

Key Concepts

- Algebraic Data Types: “Haskell Programming from First Principles” Chapter 11

- Pattern Matching: “Learn You a Haskell for Great Good!” Chapter 4

- Recursive Data: “Programming in Haskell” Chapter 8 - Graham Hutton

Difficulty

Intermediate

Time estimate

1-2 weeks

Prerequisites

Basic Haskell syntax

Real world outcome

-- Your implementations:

λ> :t myMaybe

myMaybe :: MyMaybe a

λ> myJust 5 >>= (\x -> myJust (x * 2))

MyJust 10

λ> myNothing >>= (\x -> myJust (x * 2))

MyNothing

λ> myFoldr (+) 0 (myCons 1 (myCons 2 (myCons 3 myNil)))

6

λ> myMap (*2) (myCons 1 (myCons 2 (myCons 3 myNil)))

MyCons 2 (MyCons 4 (MyCons 6 MyNil))

λ> treeSum (Node 1 (Node 2 Leaf Leaf) (Node 3 Leaf Leaf))

6

λ> treeDepth (Node 1 (Node 2 (Node 3 Leaf Leaf) Leaf) Leaf)

3

Implementation Hints

Pseudo-Haskell:

-- Maybe: a value or nothing

data MyMaybe a = MyNothing | MyJust a

myFromMaybe :: a -> MyMaybe a -> a

myFromMaybe def MyNothing = def

myFromMaybe _ (MyJust x) = x

myMapMaybe :: (a -> b) -> MyMaybe a -> MyMaybe b

myMapMaybe _ MyNothing = MyNothing

myMapMaybe f (MyJust x) = MyJust (f x)

-- Either: one of two alternatives

data MyEither a b = MyLeft a | MyRight b

myEither :: (a -> c) -> (b -> c) -> MyEither a b -> c

myEither f _ (MyLeft x) = f x

myEither _ g (MyRight y) = g y

-- List: recursive sequence

data MyList a = MyNil | MyCons a (MyList a)

myFoldr :: (a -> b -> b) -> b -> MyList a -> b

myFoldr _ z MyNil = z

myFoldr f z (MyCons x xs) = f x (myFoldr f z xs)

myMap :: (a -> b) -> MyList a -> MyList b

myMap f = myFoldr (\x acc -> MyCons (f x) acc) MyNil

myFilter :: (a -> Bool) -> MyList a -> MyList a

myFilter p = myFoldr (\x acc -> if p x then MyCons x acc else acc) MyNil

-- Binary Tree

data MyTree a = Leaf | Node a (MyTree a) (MyTree a)

treeSum :: Num a => MyTree a -> a

treeSum Leaf = 0

treeSum (Node x left right) = x + treeSum left + treeSum right

treeFold :: b -> (a -> b -> b -> b) -> MyTree a -> b

treeFold leaf _ Leaf = leaf

treeFold leaf node (Node x left right) =

node x (treeFold leaf node left) (treeFold leaf node right)

Learning milestones

- Maybe and Either work → You understand sum types

- List fold/map work → You understand recursion schemes

- Tree operations work → You understand recursive data

- Can express any computation with folds → You understand catamorphisms

Project 6: The Functor-Applicative-Monad Hierarchy

- File: FUNCTIONAL_PROGRAMMING_LAMBDA_CALCULUS_HASKELL_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: Haskell

- Alternative Programming Languages: Scala, PureScript, OCaml

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold” (Educational/Personal Brand)

- Difficulty: Level 4: Expert

- Knowledge Area: Type Classes / Category Theory

- Software or Tool: Type Class Hierarchy

- Main Book: “Haskell Programming from First Principles” by Christopher Allen and Julie Moronuki

What you’ll build

Implement the Functor → Applicative → Monad hierarchy from scratch for multiple types (Maybe, Either, List, Reader, State), proving the laws hold and understanding why each abstraction is needed.

Why it teaches Functional Programming

Monads are infamous, but they’re just the third level of a beautiful abstraction hierarchy. Understanding this progression—from “mappable” (Functor) to “liftable” (Applicative) to “flattenable” (Monad)—is the key to advanced Haskell.

Core challenges you’ll face

- Functor (mapping over structure:

fmap) → maps to preserving structure - Applicative (applying wrapped functions:

<*>) → maps to independent effects - Monad (sequencing with result dependency:

>>=) → maps to dependent effects - Laws (proving identity, composition, associativity) → maps to correctness

Key Concepts

- Functors: “Haskell Programming from First Principles” Chapter 16

- Applicatives: “Haskell Programming from First Principles” Chapter 17

- Monads: “Haskell Programming from First Principles” Chapter 18

- Category Theory Connection: Haskell Wikibooks - Category Theory

Difficulty

Expert

Time estimate

2-3 weeks

Prerequisites

Project 5, understanding of type classes

Real world outcome

-- Your implementations work with any Functor/Applicative/Monad:

λ> myFmap (+1) (MyJust 5)

MyJust 6

λ> myPure (+) <*> MyJust 3 <*> MyJust 4

MyJust 7

λ> MyJust 3 >>= (\x -> MyJust 4 >>= (\y -> MyJust (x + y)))

MyJust 7

-- Same code works for List:

λ> myFmap (*2) (MyCons 1 (MyCons 2 (MyCons 3 MyNil)))

MyCons 2 (MyCons 4 (MyCons 6 MyNil))

λ> myPure (+) <*> (MyCons 1 (MyCons 2 MyNil)) <*> (MyCons 10 (MyCons 20 MyNil))

MyCons 11 (MyCons 21 (MyCons 12 (MyCons 22 MyNil)))

-- Functor laws verified:

λ> verifyFunctorIdentity (MyJust 5)

✓ fmap id = id

λ> verifyFunctorComposition (+1) (*2) (MyJust 5)

✓ fmap (f . g) = fmap f . fmap g

Implementation Hints

Pseudo-Haskell:

-- Functor: things you can map over

class MyFunctor f where

myFmap :: (a -> b) -> f a -> f b

-- Laws:

-- Identity: fmap id = id

-- Composition: fmap (f . g) = fmap f . fmap g

instance MyFunctor MyMaybe where

myFmap _ MyNothing = MyNothing

myFmap f (MyJust x) = MyJust (f x)

instance MyFunctor MyList where

myFmap _ MyNil = MyNil

myFmap f (MyCons x xs) = MyCons (f x) (myFmap f xs)

-- Applicative: Functors with "pure" and "apply"

class MyFunctor f => MyApplicative f where

myPure :: a -> f a

(<*>) :: f (a -> b) -> f a -> f b

-- Laws:

-- Identity: pure id <*> v = v

-- Homomorphism: pure f <*> pure x = pure (f x)

-- Interchange: u <*> pure y = pure ($ y) <*> u

-- Composition: pure (.) <*> u <*> v <*> w = u <*> (v <*> w)

instance MyApplicative MyMaybe where

myPure = MyJust

MyNothing <*> _ = MyNothing

_ <*> MyNothing = MyNothing

(MyJust f) <*> (MyJust x) = MyJust (f x)

instance MyApplicative MyList where

myPure x = MyCons x MyNil

fs <*> xs = myFlatMap (\f -> myFmap f xs) fs

-- Monad: Applicatives with "bind"

class MyApplicative m => MyMonad m where

(>>=) :: m a -> (a -> m b) -> m b

-- Laws:

-- Left identity: return a >>= f = f a

-- Right identity: m >>= return = m

-- Associativity: (m >>= f) >>= g = m >>= (\x -> f x >>= g)

instance MyMonad MyMaybe where

MyNothing >>= _ = MyNothing

(MyJust x) >>= f = f x

instance MyMonad MyList where

xs >>= f = myFlatMap f xs

myFlatMap :: (a -> MyList b) -> MyList a -> MyList b

myFlatMap _ MyNil = MyNil

myFlatMap f (MyCons x xs) = myAppend (f x) (myFlatMap f xs)

-- The difference between Applicative and Monad:

-- Applicative: effects are independent (can be parallelized)

-- Monad: later effects can depend on earlier results

-- With Applicative, you can do:

liftA2 :: MyApplicative f => (a -> b -> c) -> f a -> f b -> f c

liftA2 f x y = myPure f <*> x <*> y

-- With Monad, you can do:

-- x >>= (\a -> y >>= (\b -> if a > 0 then ... else ...))

-- The choice of second effect depends on first result!

Learning milestones

- Functor instances work → You understand mapping over structure

- Applicative instances work → You understand independent effects

- Monad instances work → You understand dependent sequencing

- Laws verified → You understand correctness guarantees

Project 7: Parser Combinator Library

- File: FUNCTIONAL_PROGRAMMING_LAMBDA_CALCULUS_HASKELL_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: Haskell

- Alternative Programming Languages: Scala, OCaml, F#

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 3. The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Parsing / Combinators

- Software or Tool: Parsec Clone

- Main Book: “Programming in Haskell” by Graham Hutton

What you’ll build

A monadic parser combinator library (like Parsec) from scratch. Combinators for sequencing, choice, repetition, and error reporting. Use it to parse a non-trivial language (JSON or a simple programming language).

Why it teaches Functional Programming

Parser combinators are the crown jewel of functional programming. They demonstrate how small, composable pieces combine into powerful tools. You’ll see monads in their natural habitat: sequencing computations that might fail.

Core challenges you’ll face

- Parser type (String → Maybe (a, String) or better) → maps to state + failure

- Functor/Applicative/Monad (making parsers composable) → maps to type class instances

- Alternative (choice between parsers:

<|>) → maps to backtracking - Error messages (what went wrong, where) → maps to practical usability

Key Concepts

- Parser Combinators: “Programming in Haskell” Chapter 13 - Graham Hutton

- Monadic Parsing: “Monadic Parsing in Haskell” paper by Hutton & Meijer

- Error Handling: “Megaparsec” documentation

Difficulty

Advanced

Time estimate

2-3 weeks

Prerequisites

Projects 5 & 6

Real world outcome

-- Define JSON parser using your combinators:

jsonValue :: Parser JSON

jsonValue = jsonNull <|> jsonBool <|> jsonNumber <|> jsonString

<|> jsonArray <|> jsonObject

-- Parse JSON:

λ> parse jsonValue "{\"name\": \"Alice\", \"age\": 30, \"active\": true}"

Right (JObject [("name", JString "Alice"), ("age", JNumber 30), ("active", JBool True)])

λ> parse jsonValue "[1, 2, 3]"

Right (JArray [JNumber 1, JNumber 2, JNumber 3])

λ> parse jsonValue "{invalid"

Left "Line 1, Column 2: Expected '\"', got 'i'"

-- Parse arithmetic expressions:

λ> parse expr "1 + 2 * 3"

Right (Add (Num 1) (Mul (Num 2) (Num 3)))

λ> parse expr "(1 + 2) * 3"

Right (Mul (Add (Num 1) (Num 2)) (Num 3))

Implementation Hints

Pseudo-Haskell:

-- Parser type: input → either error or (result, remaining input)

newtype Parser a = Parser { runParser :: String -> Either ParseError (a, String) }

data ParseError = ParseError { pePosition :: Int, peExpected :: String, peGot :: String }

instance Functor Parser where

fmap f (Parser p) = Parser $ \input -> do

(x, rest) <- p input

return (f x, rest)

instance Applicative Parser where

pure x = Parser $ \input -> Right (x, input)

(Parser pf) <*> (Parser pa) = Parser $ \input -> do

(f, rest1) <- pf input

(a, rest2) <- pa rest1

return (f a, rest2)

instance Monad Parser where

(Parser pa) >>= f = Parser $ \input -> do

(a, rest) <- pa input

runParser (f a) rest

instance Alternative Parser where

empty = Parser $ \_ -> Left (ParseError 0 "something" "nothing")

(Parser p1) <|> (Parser p2) = Parser $ \input ->

case p1 input of

Right result -> Right result

Left _ -> p2 input -- backtrack and try p2

-- Primitive parsers

satisfy :: (Char -> Bool) -> Parser Char

satisfy pred = Parser $ \input -> case input of

(c:cs) | pred c -> Right (c, cs)

(c:_) -> Left (ParseError 0 "matching char" [c])

[] -> Left (ParseError 0 "char" "end of input")

char :: Char -> Parser Char

char c = satisfy (== c)

string :: String -> Parser String

string = traverse char

-- Combinators

many :: Parser a -> Parser [a]

many p = many1 p <|> pure []

many1 :: Parser a -> Parser [a]

many1 p = (:) <$> p <*> many p

sepBy :: Parser a -> Parser sep -> Parser [a]

sepBy p sep = sepBy1 p sep <|> pure []

sepBy1 :: Parser a -> Parser sep -> Parser [a]

sepBy1 p sep = (:) <$> p <*> many (sep *> p)

between :: Parser open -> Parser close -> Parser a -> Parser a

between open close p = open *> p <* close

-- JSON parser (using your combinators!)

jsonNull :: Parser JSON

jsonNull = JNull <$ string "null"

jsonBool :: Parser JSON

jsonBool = (JBool True <$ string "true") <|> (JBool False <$ string "false")

jsonNumber :: Parser JSON

jsonNumber = JNumber . read <$> many1 (satisfy isDigit)

jsonString :: Parser JSON

jsonString = JString <$> between (char '"') (char '"') (many (satisfy (/= '"')))

jsonArray :: Parser JSON

jsonArray = JArray <$> between (char '[') (char ']') (sepBy jsonValue (char ','))

jsonObject :: Parser JSON

jsonObject = JObject <$> between (char '{') (char '}') (sepBy keyValue (char ','))

where keyValue = (,) <$> (jstring <* char ':') <*> jsonValue

Learning milestones

- Basic parsers work → You understand the parser type

- Combinators compose → You understand monadic sequencing

- JSON parses correctly → You’ve built something useful

- Good error messages → You’ve made it practical

Project 8: Lazy Evaluation Demonstrator

- File: FUNCTIONAL_PROGRAMMING_LAMBDA_CALCULUS_HASKELL_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: Haskell

- Alternative Programming Languages: Scala (with lazy vals), OCaml (with Lazy)

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold” (Educational/Personal Brand)

- Difficulty: Level 4: Expert

- Knowledge Area: Evaluation Strategies / Laziness

- Software or Tool: Thunk Visualizer

- Main Book: “Haskell in Depth” by Vitaly Bragilevsky

What you’ll build

A visualization tool showing how lazy evaluation works: thunks, forcing, sharing, and space leaks. Implement a lazy evaluator and demonstrate infinite data structures.

Why it teaches Functional Programming

Laziness is Haskell’s secret weapon and biggest footgun. Understanding thunks, weak head normal form, and when forcing happens lets you write efficient code and debug space leaks.

Core challenges you’ll face

- Thunk representation (suspended computations) → maps to call-by-need

- Forcing and WHNF (when evaluation happens) → maps to evaluation order

- Sharing (computing once, using many times) → maps to efficiency

- Space leaks (thunks accumulating) → maps to performance

- Infinite structures (lazy lists, streams) → maps to elegance

Key Concepts

- Lazy Evaluation: “Haskell in Depth” Chapter 4 - Bragilevsky

- Space Leaks: “Real World Haskell” Chapter 25 - O’Sullivan et al.

- Strictness Analysis: GHC documentation on strictness

Difficulty

Expert

Time estimate

2-3 weeks

Prerequisites

Projects 1-6

Real world outcome

λ> let xs = [1..] in take 5 xs

-- Visualization:

xs = 1 : <thunk>

↓ force (need 5 elements)

xs = 1 : 2 : <thunk>

↓ force

xs = 1 : 2 : 3 : <thunk>

↓ force

xs = 1 : 2 : 3 : 4 : <thunk>

↓ force

xs = 1 : 2 : 3 : 4 : 5 : <thunk> -- thunk remains!

Result: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

Thunks created: 6

Thunks forced: 5

Thunks remaining: 1 (rest of infinite list)

λ> let fibs = 0 : 1 : zipWith (+) fibs (tail fibs)

λ> take 10 fibs

-- Sharing visualization:

fibs[0] = 0 (computed)

fibs[1] = 1 (computed)

fibs[2] = <thunk: fibs[0] + fibs[1]>

↓ force

fibs[2] = 1 (computed, shared reference)

fibs[3] = <thunk: fibs[1] + fibs[2]>

↓ force (reuses computed fibs[2]!)

fibs[3] = 2 (computed)

...

Result: [0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34]

Additions performed: 8 (not exponential!)

λ> foldl (+) 0 [1..1000000]

-- Space leak visualization:

0 + 1 = <thunk>

<thunk> + 2 = <thunk>

<thunk> + 3 = <thunk>

... 1 million thunks! ...

Finally forced → stack overflow!

λ> foldl' (+) 0 [1..1000000]

-- Strict version:

0 + 1 = 1 (forced immediately)

1 + 2 = 3 (forced immediately)

3 + 3 = 6 (forced immediately)

... constant space! ...

Result: 500000500000

Implementation Hints

Build a small lazy language evaluator:

Pseudo-Haskell:

-- Thunk: unevaluated expression + environment

data Thunk = Thunk Expr Env | Forced Value

-- Value in WHNF (Weak Head Normal Form)

data Value

= VInt Int

| VBool Bool

| VClosure String Expr Env

| VCons Thunk Thunk -- Lazy list: head and tail are thunks

| VNil

-- Mutable thunk storage (for sharing)

type ThunkRef = IORef Thunk

-- Force a thunk: evaluate to WHNF and cache result

force :: ThunkRef -> IO Value

force ref = do

thunk <- readIORef ref

case thunk of

Forced v -> return v -- Already computed, return cached

Thunk expr env -> do

v <- eval expr env

writeIORef ref (Forced v) -- Cache the result!

return v

-- Evaluate expression to WHNF

eval :: Expr -> Env -> IO Value

eval (Var x) env =

case lookup x env of

Just ref -> force ref -- Force the thunk

Nothing -> error "Unbound variable"

eval (Lam x body) env = return (VClosure x body env)

eval (App f arg) env = do

fVal <- eval f env

case fVal of

VClosure x body closureEnv -> do

-- Don't evaluate arg yet! Create thunk

argRef <- newIORef (Thunk arg env)

eval body ((x, argRef) : closureEnv)

eval (Cons hd tl) env = do

-- Both head and tail are thunks!

hdRef <- newIORef (Thunk hd env)

tlRef <- newIORef (Thunk tl env)

return (VCons hdRef tlRef)

-- Infinite list of ones

-- ones = 1 : ones

-- ones = Cons (Int 1) (Var "ones")

-- with environment { "ones" -> <thunk: ones definition> }

Learning milestones

- Thunks visualize correctly → You understand lazy evaluation

- Sharing prevents recomputation → You understand efficiency

- Infinite structures work → You understand laziness power

- Space leaks identified → You understand strictness

Project 9: Monad Transformers from Scratch

- File: FUNCTIONAL_PROGRAMMING_LAMBDA_CALCULUS_HASKELL_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: Haskell

- Alternative Programming Languages: Scala, PureScript

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold” (Educational/Personal Brand)

- Difficulty: Level 4: Expert

- Knowledge Area: Effects / Monad Transformers

- Software or Tool: MTL Clone

- Main Book: “Haskell in Depth” by Vitaly Bragilevsky

What you’ll build

Implement the common monad transformers (MaybeT, EitherT, ReaderT, StateT, WriterT) and understand how to stack them to combine effects.

Why it teaches Functional Programming

Real programs need multiple effects: reading config, maintaining state, handling errors, logging. Monad transformers let you compose these effects. Understanding them is essential for real Haskell.

Core challenges you’ll face

- Transformer types (wrapping monads in other monads) → maps to effect composition

- Lift operation (running inner monad in outer) → maps to effect access

- MonadTrans class (abstracting over transformers) → maps to generic lifting

- Stack ordering (StateT over Maybe vs Maybe over State) → maps to effect semantics

Key Concepts

- Monad Transformers: “Haskell in Depth” Chapter 5 - Bragilevsky

- MTL Style: “Monad Transformers Step by Step” paper by Martin Grabmüller

- Effect Order: Different orders give different behaviors!

Difficulty

Expert

Time estimate

2-3 weeks

Prerequisites

Project 6 (Functor/Applicative/Monad)

Real world outcome

-- Stack: ReaderT Config (StateT AppState (ExceptT AppError IO))

type App a = ReaderT Config (StateT AppState (ExceptT AppError IO)) a

runApp :: Config -> AppState -> App a -> IO (Either AppError (a, AppState))

runApp config state app =

runExceptT (runStateT (runReaderT app config) state)

-- Your transformers in action:

myProgram :: App String

myProgram = do

config <- ask -- ReaderT effect

modify (incrementCounter) -- StateT effect

when (count config > 100) $

throwError TooManyRequests -- ExceptT effect

liftIO $ putStrLn "Hello" -- IO effect

return "done"

λ> runApp defaultConfig initialState myProgram

Right ("done", AppState { counter = 1, ... })

λ> runApp badConfig initialState myProgram

Left TooManyRequests

Implementation Hints

Pseudo-Haskell:

-- MaybeT: add failure to any monad

newtype MaybeT m a = MaybeT { runMaybeT :: m (Maybe a) }

instance Monad m => Functor (MaybeT m) where

fmap f (MaybeT mma) = MaybeT $ fmap (fmap f) mma

instance Monad m => Applicative (MaybeT m) where

pure = MaybeT . pure . Just

(MaybeT mmf) <*> (MaybeT mma) = MaybeT $ do

mf <- mmf

case mf of

Nothing -> return Nothing

Just f -> fmap (fmap f) mma

instance Monad m => Monad (MaybeT m) where

(MaybeT mma) >>= f = MaybeT $ do

ma <- mma

case ma of

Nothing -> return Nothing

Just a -> runMaybeT (f a)

-- StateT: add mutable state to any monad

newtype StateT s m a = StateT { runStateT :: s -> m (a, s) }

instance Monad m => Monad (StateT s m) where

(StateT f) >>= g = StateT $ \s -> do

(a, s') <- f s

runStateT (g a) s'

get :: Monad m => StateT s m s

get = StateT $ \s -> return (s, s)

put :: Monad m => s -> StateT s m ()

put s = StateT $ \_ -> return ((), s)

modify :: Monad m => (s -> s) -> StateT s m ()

modify f = get >>= put . f

-- ReaderT: add read-only environment to any monad

newtype ReaderT r m a = ReaderT { runReaderT :: r -> m a }

instance Monad m => Monad (ReaderT r m) where

(ReaderT f) >>= g = ReaderT $ \r -> do

a <- f r

runReaderT (g a) r

ask :: Monad m => ReaderT r m r

ask = ReaderT return

local :: (r -> r) -> ReaderT r m a -> ReaderT r m a

local f (ReaderT g) = ReaderT (g . f)

-- MonadTrans: lifting operations

class MonadTrans t where

lift :: Monad m => m a -> t m a

instance MonadTrans MaybeT where

lift ma = MaybeT (fmap Just ma)

instance MonadTrans (StateT s) where

lift ma = StateT $ \s -> fmap (\a -> (a, s)) ma

instance MonadTrans (ReaderT r) where

lift ma = ReaderT $ \_ -> ma

Learning milestones

- Individual transformers work → You understand each effect

- Stacking works → You understand composition

- Lift works at any level → You understand MonadTrans

- Different orders behave differently → You understand effect semantics

Project 10: Property-Based Testing Framework

- File: FUNCTIONAL_PROGRAMMING_LAMBDA_CALCULUS_HASKELL_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: Haskell

- Alternative Programming Languages: Scala (ScalaCheck), F# (FsCheck), Python (Hypothesis)

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 3. The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Testing / Generators

- Software or Tool: QuickCheck Clone

- Main Book: “Real World Haskell” by O’Sullivan, Stewart, and Goerzen

What you’ll build

A property-based testing framework like QuickCheck: random generators for data, shrinking failing cases, and the core property-checking loop.

Why it teaches Functional Programming

QuickCheck is a landmark Haskell invention that spread to every language. It shows the power of higher-order functions and type classes for building generic, composable test infrastructure.

Core challenges you’ll face

- Random generators (Gen monad for generating test data) → maps to monadic generation

- Arbitrary type class (generating any type) → maps to type class polymorphism

- Shrinking (finding minimal failing case) → maps to search algorithms

- Property composition (combining tests) → maps to combinator design

Key Concepts

- QuickCheck Paper: “QuickCheck: A Lightweight Tool for Random Testing” by Claessen & Hughes

- Generators: “Real World Haskell” Chapter 11

- Shrinking: Finding the smallest counterexample

Difficulty

Advanced

Time estimate

2-3 weeks

Prerequisites

Projects 5 & 6, understanding of randomness

Real world outcome

-- Properties written with your framework:

prop_reverse_reverse :: [Int] -> Bool

prop_reverse_reverse xs = reverse (reverse xs) == xs

prop_append_length :: [Int] -> [Int] -> Bool

prop_append_length xs ys = length (xs ++ ys) == length xs + length ys

-- Bug detection:

prop_bad_sort :: [Int] -> Bool

prop_bad_sort xs = badSort xs == sort xs

λ> quickCheck prop_reverse_reverse

+++ OK, passed 100 tests.

λ> quickCheck prop_append_length

+++ OK, passed 100 tests.

λ> quickCheck prop_bad_sort

*** Failed! Falsifiable (after 12 tests):

[3, 1, 2]

Shrinking...

*** Failed! Falsifiable (after 12 tests and 4 shrinks):

[1, 0] -- Minimal counterexample!

Implementation Hints

Pseudo-Haskell:

-- Generator monad

newtype Gen a = Gen { runGen :: StdGen -> (a, StdGen) }

instance Monad Gen where

return x = Gen $ \g -> (x, g)

(Gen f) >>= k = Gen $ \g ->

let (a, g') = f g

in runGen (k a) g'

-- Arbitrary: types that can be randomly generated

class Arbitrary a where

arbitrary :: Gen a

shrink :: a -> [a] -- List of "smaller" values

shrink _ = []

instance Arbitrary Int where

arbitrary = Gen $ \g -> random g

shrink 0 = []

shrink n = [0, n `div` 2] -- Shrink towards 0

instance Arbitrary a => Arbitrary [a] where

arbitrary = do

len <- choose (0, 30)

replicateM len arbitrary

shrink [] = []

shrink (x:xs) =

[] : xs : -- Remove first element

[x':xs | x' <- shrink x] ++ -- Shrink first element

[x:xs' | xs' <- shrink xs] -- Shrink rest

-- Core testing loop

quickCheck :: Arbitrary a => (a -> Bool) -> IO ()

quickCheck prop = do

g <- newStdGen

loop 100 g

where

loop 0 _ = putStrLn "+++ OK, passed 100 tests."

loop n g = do

let (value, g') = runGen arbitrary g

if prop value

then loop (n-1) g'

else do

putStrLn $ "*** Failed! Falsifiable (after " ++ show (101-n) ++ " tests):"

print value

shrinkLoop value

shrinkLoop value =

case filter (not . prop) (shrink value) of

[] -> do

putStrLn "Minimal counterexample:"

print value

(smaller:_) -> shrinkLoop smaller -- Keep shrinking!

-- Combinators

choose :: (Int, Int) -> Gen Int

choose (lo, hi) = Gen $ \g -> randomR (lo, hi) g

elements :: [a] -> Gen a

elements xs = do

i <- choose (0, length xs - 1)

return (xs !! i)

oneof :: [Gen a] -> Gen a

oneof gens = do

i <- choose (0, length gens - 1)

gens !! i

Learning milestones

- Generators work → You understand monadic random generation

- Arbitrary instances work → You understand type class polymorphism

- Shrinking finds minimal cases → You understand search

- Framework catches real bugs → You’ve built something useful

Project 11: Lenses and Optics Library

- File: FUNCTIONAL_PROGRAMMING_LAMBDA_CALCULUS_HASKELL_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: Haskell

- Alternative Programming Languages: Scala (Monocle), PureScript

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold” (Educational/Personal Brand)

- Difficulty: Level 4: Expert

- Knowledge Area: Data Access / Optics

- Software or Tool: Lens Clone

- Main Book: “Optics By Example” by Chris Penner

What you’ll build

Implement the lens hierarchy: Lens, Prism, Traversal, Iso. Understand how they compose and use them to elegantly access and update nested data.

Why it teaches Functional Programming

In imperative programming, updating nested data is trivial: person.address.city = "NYC". In pure FP, without mutation, this requires boilerplate. Lenses solve this elegantly, and understanding them reveals deep connections to profunctors and category theory.

Core challenges you’ll face

- Lens type (getter + setter combined) → maps to composable access

- Van Laarhoven encoding (lens as function) → maps to higher-order magic

- Prisms (for sum types) → maps to partial access

- Traversals (for multiple targets) → maps to batch updates

Key Concepts

- Lenses: “Optics By Example” by Chris Penner

- Van Laarhoven: “Lenses, Folds, and Traversals” by Edward Kmett

- Profunctor Optics: Academic papers on optics

Difficulty

Expert

Time estimate

3-4 weeks

Prerequisites

Projects 5 & 6, comfort with higher-order functions

Real world outcome

-- Deeply nested update, elegantly:

data Person = Person { _name :: String, _address :: Address }

data Address = Address { _city :: String, _street :: String }

-- Without lenses (ugly):

updateCity :: String -> Person -> Person

updateCity newCity person =

person { _address = (_address person) { _city = newCity } }

-- With your lenses (elegant):

λ> set (address . city) "NYC" person

Person { _name = "Alice", _address = Address { _city = "NYC", _street = "123 Main" }}

λ> view (address . city) person

"NYC"

λ> over (address . city) toUpper person

Person { _name = "Alice", _address = Address { _city = "NYC", _street = "123 Main" }}

-- Traversals (update multiple):

λ> over (employees . traverse . salary) (*1.1) company

-- Gives everyone a 10% raise!

-- Prisms (for sum types):

λ> preview _Left (Left 5)

Just 5

λ> preview _Left (Right "hello")

Nothing

Implementation Hints

Pseudo-Haskell:

-- Simple lens (getter + setter)

data Lens' s a = Lens'

{ view :: s -> a

, set :: a -> s -> s

}

-- Compose lenses

(.) :: Lens' a b -> Lens' b c -> Lens' a c

(Lens' viewAB setAB) . (Lens' viewBC setBC) = Lens'

{ view = viewBC . viewAB

, set = \c a -> setAB (setBC c (viewAB a)) a

}

-- The magic: Van Laarhoven representation

-- A lens is a function that, given a way to "focus" on the inner value,

-- produces a way to "focus" on the outer value

type Lens s t a b = forall f. Functor f => (a -> f b) -> s -> f t

type Lens' s a = Lens s s a a

-- Building a lens

lens :: (s -> a) -> (s -> b -> t) -> Lens s t a b

lens getter setter = \f s -> setter s <$> f (getter s)

-- Using a lens to get

view :: Lens' s a -> s -> a

view l s = getConst (l Const s)

-- Using a lens to set

set :: Lens' s a -> a -> s -> s

set l a s = runIdentity (l (\_ -> Identity a) s)

-- Using a lens to modify

over :: Lens' s a -> (a -> a) -> s -> s

over l f s = runIdentity (l (Identity . f) s)

-- Composition is just function composition!

-- (l1 . l2) automatically works because of the type signature

-- Traversals: focus on multiple values

type Traversal s t a b = forall f. Applicative f => (a -> f b) -> s -> f t

-- Traverse over a list

traverse :: Traversal [a] [b] a b

traverse f = sequenceA . map f

-- Prisms: for sum types (partial access)

type Prism s t a b = forall p f. (Choice p, Applicative f) => p a (f b) -> p s (f t)

_Left :: Prism (Either a c) (Either b c) a b

_Right :: Prism (Either c a) (Either c b) a b

Learning milestones

- Simple lenses work → You understand getter/setter fusion

- Lens composition works → You understand composability

- Traversals work → You understand multiple targets

- Prisms work → You understand partial access

Real World Outcome

When you run your lens library, you’ll experience the transformative power of composable accessors for nested data structures. Here’s exactly what you’ll see:

-- Start your GHCi REPL with your library loaded:

$ ghci LensLibrary.hs

GHCi, version 9.4.7: https://www.haskell.org/ghc/ :? for help

-- Define deeply nested data:

λ> data Person = Person { _name :: String, _address :: Address } deriving (Show)

λ> data Address = Address { _city :: String, _street :: Street } deriving (Show)

λ> data Street = Street { _number :: Int, _name :: String } deriving (Show)

-- Create test data:

λ> let alice = Person "Alice" (Address "NYC" (Street 42 "Main St"))

λ> alice

Person {_name = "Alice", _address = Address {_city = "NYC", _street = Street {_number = 42, _name = "Main St"}}}

-- WITHOUT LENSES (the old painful way):

λ> alice { _address = (_address alice) { _street = (_street (_address alice)) { _number = 100 }}}

Person {_name = "Alice", _address = Address {_city = "NYC", _street = Street {_number = 100, _name = "Main St"}}}

-- Deeply nested, hard to read, error-prone!

-- WITH YOUR LENSES (elegant composition):

λ> import Control.Lens

λ> set (address . street . number) 100 alice

Person {_name = "Alice", _address = Address {_city = "NYC", _street = Street {_number = 100, _name = "Main St"}}}

-- Beautiful! Reads like: "set the street number in the address to 100"

-- View (get) values deep in structures:

λ> view (address . city) alice

"NYC"

λ> view (address . street . number) alice

42

-- Modify (over) values with a function:

λ> over (address . city) (map toUpper) alice

Person {_name = "Alice", _address = Address {_city = "NYC", _street = Street {_number = 42, _name = "Main St"}}}

λ> over (address . street . number) (*2) alice

Person {_name = "Alice", _address = Address {_city = "NYC", _street = Street {_number = 84, _name = "Main St"}}}

-- TRAVERSALS - operate on multiple values at once:

λ> data Company = Company { _employees :: [Person] } deriving Show

λ> let company = Company [alice, Person "Bob" (Address "SF" (Street 10 "Oak"))]

λ> over (employees . traverse . address . city) (map toUpper) company

Company {_employees = [Person {_name = "Alice", _address = Address {_city = "NYC", ...}},

Person {_name = "Bob", _address = Address {_city = "SF", ...}}]}

-- Changed EVERY employee's city to uppercase in one elegant expression!

-- PRISMS - work with sum types (Either, Maybe):

λ> preview _Just (Just 42)

Just 42

λ> preview _Just Nothing

Nothing

λ> preview _Left (Left "error")

Just "error"

λ> preview _Left (Right 100)

Nothing

-- Practical example: safely extract from Maybe

λ> set _Just 100 (Just 42)

Just 100

λ> set _Just 100 Nothing

Nothing

-- Prism respects the structure!

-- FOLDING with lenses:

λ> toListOf (employees . traverse . address . city) company

["NYC","SF"]

-- Extract all cities from all employees!

-- MULTIPLE UPDATES:

λ> let complexData = Company [

Person "Alice" (Address "NYC" (Street 42 "Main")),

Person "Bob" (Address "SF" (Street 10 "Oak")),

Person "Carol" (Address "LA" (Street 7 "Elm"))

]

λ> over (employees . traverse . address . street . number) (+100) complexData

Company {_employees = [

Person {_name = "Alice", _address = Address {_city = "NYC", _street = Street {_number = 142, ...}}},

Person {_name = "Bob", _address = Address {_city = "SF", _street = Street {_number = 110, ...}}},

Person {_name = "Carol", _address = Address {_city = "LA", _street = Street {_number = 107, ...}}}]}

-- Added 100 to EVERY street number in the company!

What you’re experiencing:

- Composability: Lenses compose with

.just like functions - Type safety: The compiler ensures you’re accessing valid fields

- Elegance: What took 3 lines of nested record updates now takes 1 line

- Power: Traversals let you update multiple values simultaneously

- Flexibility: Same lens works for viewing, setting, and modifying

This is why lenses are ubiquitous in production Haskell code. You’ll never want to go back to manual nested record updates!

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do you elegantly access and update deeply nested immutable data structures without mutation or boilerplate?”

In imperative programming, updating nested data is trivial: person.address.city = "NYC". But in pure functional programming, data is immutable. You need to create a new structure with the changed value, which leads to nightmarish code like:

person { address = (address person) { city = (city (address person)) { name = "NYC" }}}

Lenses answer a deeper question: Can we make nested immutable updates as easy as mutable updates? The answer is yes, through the power of composable accessors.

But there’s an even deeper question: What if accessors were first-class values that compose? This leads to the Van Laarhoven representation, where a lens is not a pair of getter/setter, but a higher-order function that abstracts over different “actions” (getting, setting, modifying, folding).

By building this library, you’re answering:

- How can getters and setters fuse into a single composable value?

- How can the same abstraction work for single values (Lens), optional values (Prism), and multiple values (Traversal)?

- How does this connect to profunctors and category theory?

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Immutable Data Updates in Haskell

- How do record updates work in Haskell? (

person { field = newValue }) - Why is

person { address { city = "NYC" }}not valid syntax? - What’s the relationship between purity and immutability?

- Book Reference: “Learn You a Haskell for Great Good!” Chapter 8 - Miran Lipovaca

- How do record updates work in Haskell? (

- First-Class Functions and Composition

- What does it mean for a function to be “first-class”?

- How does function composition

(.)work at the type level? - Why is

(f . g) x = f (g x)? - Book Reference: “Haskell Programming from First Principles” Chapter 7 - Christopher Allen and Julie Moronuki

- Higher-Order Functions

- What is a function that takes a function as argument?

- What is a function that returns a function?

- How do combinators like

map,filter,foldrelate? - Book Reference: “Learn You a Haskell for Great Good!” Chapter 6 - Miran Lipovaca

- The Functor Type Class

- What does

fmap :: (a -> b) -> f a -> f breally mean? - What are the functor laws?

- How is

Consta functor? How isIdentitya functor? - Book Reference: “Haskell Programming from First Principles” Chapter 16 - Christopher Allen and Julie Moronuki

- What does

- Existential Quantification (forall)

- What does

forall f. Functor f => ...mean? - Why is

forallcalled “universal quantification”? - How does rank-2 polymorphism work?

- Book Reference: “Optics By Example” Chapter 2 - Chris Penner

- What does

- Product and Sum Types

- What’s the difference between a product type (record) and sum type (Either)?

- How do you access fields in a product?

- How do you pattern match on a sum?

- Book Reference: “Haskell Programming from First Principles” Chapter 11 - Christopher Allen and Julie Moronuki

- Getters and Setters as First-Class Values

- Can you pass a “getter” as a value?

- Can you compose getters?

getCity . getAddress? - How do you represent “set the city in the address”?

- Book Reference: “Optics By Example” Chapter 1 - Chris Penner

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Simple Lens Representation

- If a lens has a getter and a setter, what’s the type signature?

data Lens s a = Lens { view :: s -> a, set :: a -> s -> s }— does this work?- How do you compose two such lenses? What’s

lens1 . lens2? - Can you write

composeLens :: Lens a b -> Lens b c -> Lens a c?

- The Van Laarhoven Encoding

- Instead of storing getter/setter separately, what if a lens is a function?

type Lens s t a b = forall f. Functor f => (a -> f b) -> s -> f t- What does this type signature mean? “Given a way to focus on

a(producingf b), produce a way to focus ons(producingf t)” - Why does this automatically compose with

(.)?

- Using Different Functors for Different Operations

- To get a value: what functor captures “just return the value”? (

Const a) - To set a value: what functor captures “replace with a new value”? (

Identity) - To modify a value: what functor captures “apply a function”? (

Identityagain) - How does the same lens type work for all three operations?

- To get a value: what functor captures “just return the value”? (

- Traversals - Multiple Targets

- A Lens focuses on one value. What if you want to focus on many?

type Traversal s t a b = forall f. Applicative f => (a -> f b) -> s -> f t- Why

Applicativeinstead of justFunctor? - How does

traverseover a list fit this type?

- Prisms - Partial Access

- How do you focus on a value that might not exist?

- For

Either a b, how do you focus on thea(only if it’sLeft)? - What’s the type of a Prism? (Hint: involves

Choiceprofunctor) - Why can’t you always “set” through a prism?

Thinking Exercise

Build a Mental Model of Lens Composition

Before coding, trace this by hand:

-- Given:

data Person = Person { _address :: Address }

data Address = Address { _city :: String }

let alice = Person (Address "NYC")

-- Define simple lenses:

address :: Lens' Person Address

address = lens _address (\person newAddr -> person { _address = newAddr })

city :: Lens' Address String

city = lens _city (\addr newCity -> addr { _city = newCity })

-- Compose them:

addressCity :: Lens' Person String

addressCity = address . city

-- Now trace: view addressCity alice

-- Step by step:

-- 1. addressCity = address . city

-- 2. view (address . city) alice

-- 3. Expand composition: view city (view address alice)

-- 4. view address alice = _address alice = Address "NYC"

-- 5. view city (Address "NYC") = _city (Address "NYC") = "NYC"

-- Result: "NYC"

-- Trace: set addressCity "SF" alice

-- Step by step:

-- 1. set (address . city) "SF" alice

-- 2. set address (set city "SF" (view address alice)) alice

-- 3. view address alice = Address "NYC"

-- 4. set city "SF" (Address "NYC") = Address "SF"

-- 5. set address (Address "SF") alice = alice { _address = Address "SF" }

-- Result: Person (Address "SF")

Questions while tracing:

- At what point does the composition happen?

- How many times do you “dive into” the address?

- Draw a diagram showing the flow of data through the composed lens

- Why does this feel like function composition?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “What is a lens and why would you use one?”

- Answer: A composable accessor for nested data. In pure FP, updating nested structures without mutation is painful. Lenses make it elegant.

- “How do lenses compose? Why is it better than manual composition?”

- Answer: Lenses compose with

(.)because of the Van Laarhoven encoding. Manual composition requires writing boilerplate for each nesting level.

- Answer: Lenses compose with

- “What’s the difference between a Lens, a Prism, and a Traversal?”

- Answer: Lens focuses on one mandatory value. Prism focuses on one optional value (sum types). Traversal focuses on zero-or-more values.

- “Explain the type signature:

type Lens s t a b = forall f. Functor f => (a -> f b) -> s -> f t“- Answer: It’s a rank-2 polymorphic function. Given a way to focus on the small thing (

a), it produces a way to focus on the big thing (s). The functorfdetermines what “focus” means (get, set, modify).

- Answer: It’s a rank-2 polymorphic function. Given a way to focus on the small thing (

- “Why do Traversals require Applicative instead of just Functor?”

- Answer: Because traversals work with multiple values. Applicative allows combining effects (

<*>), which is necessary when you’re updating multiple targets.

- Answer: Because traversals work with multiple values. Applicative allows combining effects (

- “How would you implement

over(modify through a lens)?”- Answer:

over l f s = runIdentity (l (Identity . f) s). UseIdentityfunctor and apply the functionfat the focus point.

- Answer:

- “What real-world problems do lenses solve?”

- Answer: Updating deeply nested JSON in web APIs, modifying game state (player in level in world), updating configuration structures, working with databases/ORMs.

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with Simple Lenses (Data Constructor)

Don’t jump to Van Laarhoven encoding immediately. Start simple:

data Lens' s a = Lens'

{ view :: s -> a

, set :: a -> s -> s

}

-- Create a lens for a record field:

nameLens :: Lens' Person String

nameLens = Lens'

{ view = \(Person name _) -> name

, set = \newName (Person _ addr) -> Person newName addr

}

-- Use it:

view nameLens alice -- gets name

set nameLens "Bob" alice -- sets name

Hint 2: Implement over using view and set

over :: Lens' s a -> (a -> a) -> s -> s

over l f s = set l (f (view l s)) s

-- Example:

over nameLens (map toUpper) alice

-- Gets the name, applies toUpper to it, sets it back

Hint 3: Try to Compose Simple Lenses

composeLens :: Lens' a b -> Lens' b c -> Lens' a c

composeLens (Lens' viewAB setAB) (Lens' viewBC setBC) = Lens'

{ view = \a -> viewBC (viewAB a)

, set = \c a -> setAB (setBC c (viewAB a)) a

}

This works, but notice the complexity! This motivates the Van Laarhoven encoding.

Hint 4: Understand Van Laarhoven Encoding

The key insight: a lens is a way to apply a functor-wrapped function to a focused part.

type Lens s t a b = forall f. Functor f => (a -> f b) -> s -> f t

type Lens' s a = Lens s s a a -- simple version

-- Build a lens:

lens :: (s -> a) -> (s -> b -> t) -> Lens s t a b

lens getter setter = \f s -> setter s <$> f (getter s)

-- ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

-- Apply f to the focused value (getter s)

-- Then use setter to rebuild the structure

-- Use it to view:

view :: Lens' s a -> s -> a

view l s = getConst (l Const s)

-- ^^^^^^

-- l expects: a -> f a

-- Const :: a -> Const a b

-- Result: Const a, extract with getConst

-- Use it to set:

set :: Lens' s a -> a -> s -> s

set l newVal s = runIdentity (l (\_ -> Identity newVal) s)

-- ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

-- Ignore old value, return new value wrapped in Identity

-- Use it to modify:

over :: Lens' s a -> (a -> a) -> s -> s

over l f s = runIdentity (l (Identity . f) s)

-- ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

-- Apply f and wrap result in Identity

Hint 5: Implement Traversals

A traversal is just a lens that allows multiple focuses:

type Traversal s t a b = forall f. Applicative f => (a -> f b) -> s -> f t

-- Traverse a list:

traverseList :: Traversal [a] [b] a b

traverseList f [] = pure []

traverseList f (x:xs) = (:) <$> f x <*> traverseList f xs

-- ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

-- Applicative allows combining multiple effects

-- Use it:

toListOf :: Traversal s t a b -> s -> [a]

toListOf t s = getConst (t (\a -> Const [a]) s)

Hint 6: Implement Prisms

A prism is for sum types (optional values):

-- Simplified prism:

data Prism' s a = Prism'

{ preview :: s -> Maybe a -- might not exist

, review :: a -> s -- always can construct

}

_Just :: Prism' (Maybe a) a

_Just = Prism'

{ preview = id -- Maybe a -> Maybe a

, review = Just -- a -> Maybe a

}

_Left :: Prism' (Either a b) a

_Left = Prism'

{ preview = either Just (const Nothing)

, review = Left

}

Hint 7: Use lens Library’s Types for Reference

Once you understand the basics, look at the real lens library:

$ ghci

λ> :i Lens

type Lens s t a b = forall f. Functor f => (a -> f b) -> s -> f t

λ> :i Traversal

type Traversal s t a b = forall f. Applicative f => (a -> f b) -> s -> f t

λ> :i Prism

type Prism s t a b = forall p f. (Choice p, Applicative f) => p a (f b) -> p s (f t)

Study the difference in constraints. Each adds power at the cost of generality.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| What lenses are and why they matter | “Optics By Example” | Ch. 1-3 |

| Van Laarhoven encoding | “Optics By Example” | Ch. 4 |

| Composing lenses | “Optics By Example” | Ch. 5 |

| Traversals and multiple focuses | “Optics By Example” | Ch. 6 |

| Prisms for sum types | “Optics By Example” | Ch. 8 |

| Isos and other optics | “Optics By Example” | Ch. 9-10 |

| Functor and Applicative (prerequisites) | “Haskell Programming from First Principles” | Ch. 16-17 |

| Higher-order functions | “Learn You a Haskell for Great Good!” | Ch. 6 |

| Advanced type features (Rank-N types) | “Thinking with Types” by Sandy Maguire | Ch. 6 |

| Profunctor optics (advanced) | “Profunctor Optics: Modular Data Accessors” (paper) | Full paper |

| Real-world lens usage | “Haskell in Depth” | Ch. 7.3 |

Project 12: Free Monad DSL

- File: FUNCTIONAL_PROGRAMMING_LAMBDA_CALCULUS_HASKELL_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: Haskell

- Alternative Programming Languages: Scala, PureScript

- Coolness Level: Level 5: Pure Magic (Super Cool)

- Business Potential: 4. The “Open Core” Infrastructure

- Difficulty: Level 5: Master

- Knowledge Area: DSLs / Free Structures

- Software or Tool: Free Monad Interpreter

- Main Book: “Haskell in Depth” by Vitaly Bragilevsky

What you’ll build

Create a domain-specific language (DSL) using free monads. Define an algebra of operations, build programs in the DSL, and write multiple interpreters (production, testing, logging).

Why it teaches Functional Programming

Free monads separate what a program does from how it’s executed. This is the ultimate expression of declarative programming: describe the computation abstractly, then interpret it however you want.

Core challenges you’ll face

- Free monad construction (lifting an algebra into a monad) → maps to free structures

- Smart constructors (ergonomic DSL syntax) → maps to embedded DSLs

- Interpreters (different semantics for same program) → maps to interpretation

- Effect composition (combining multiple DSLs) → maps to effect systems

Key Concepts

- Free Monads: “Haskell in Depth” Chapter 11 - Bragilevsky

- Why Free Monads Matter: Paper by Gabriel Gonzalez

- Data Types à la Carte: Composing DSLs

Difficulty

Master

Time estimate

2-3 weeks

Prerequisites

Projects 6 & 9

Real world outcome

-- Define a DSL for a key-value store:

data KVStoreF k v next

= Get k (Maybe v -> next)

| Put k v next

| Delete k next

type KVStore k v = Free (KVStoreF k v)

-- Write programs in the DSL:

program :: KVStore String Int Int

program = do

put "x" 1

put "y" 2

x <- get "x"

y <- get "y"

return $ fromMaybe 0 x + fromMaybe 0 y

-- Interpreter 1: In-memory Map

runInMemory :: KVStore String Int a -> State (Map String Int) a

-- Interpreter 2: Logging

runWithLogging :: KVStore String Int a -> IO a

-- Interpreter 3: Testing (mock)

runMock :: [(String, Int)] -> KVStore String Int a -> a

λ> evalState (runInMemory program) Map.empty

3

λ> runWithLogging program

[LOG] PUT "x" = 1

[LOG] PUT "y" = 2

[LOG] GET "x" -> Just 1

[LOG] GET "y" -> Just 2

3

λ> runMock [("x", 10), ("y", 20)] program

30

Implementation Hints

Pseudo-Haskell:

-- Free monad: "free" data structure that forms a monad

data Free f a

= Pure a

| Free (f (Free f a))

instance Functor f => Functor (Free f) where

fmap f (Pure a) = Pure (f a)

fmap f (Free fa) = Free (fmap (fmap f) fa)

instance Functor f => Applicative (Free f) where

pure = Pure

Pure f <*> a = fmap f a

Free ff <*> a = Free (fmap (<*> a) ff)

instance Functor f => Monad (Free f) where

Pure a >>= f = f a

Free fa >>= f = Free (fmap (>>= f) fa)

-- Lift a functor value into Free

liftF :: Functor f => f a -> Free f a

liftF fa = Free (fmap Pure fa)

-- Our DSL functor

data KVStoreF k v next

= Get k (Maybe v -> next)

| Put k v next

| Delete k next

deriving Functor

type KVStore k v = Free (KVStoreF k v)

-- Smart constructors (ergonomic API)

get :: k -> KVStore k v (Maybe v)

get k = liftF (Get k id)

put :: k -> v -> KVStore k v ()

put k v = liftF (Put k v ())

delete :: k -> KVStore k v ()

delete k = liftF (Delete k ())