Web3 Deep Understanding - Project-Based Learning Path

Goal: Deeply understand Web3 from first principles—what cryptographic primitives make decentralized systems possible, why blockchains work, how consensus emerges without central authority, what the Ethereum Virtual Machine actually does, and why this technology represents a fundamental shift from trust-based to math-based systems. After completing these projects, you’ll understand not just how to use Web3, but why it exists and how every layer functions.

Prerequisites & Background Knowledge

Essential Prerequisites (Must Have)

Before diving into Web3, you need:

- Solid Programming Skills (intermediate level in at least one language)

- Comfortable with data structures (arrays, hash maps, trees)

- Understanding of pointers/references and memory management

- Experience with debugging and reading error messages

- Basic Cryptography Concepts

- What encryption means (symmetric vs. asymmetric)

- General idea of hashing (even if you’ve never implemented one)

- Understanding that “random” is hard in computers

- Networking Fundamentals

- How HTTP requests work (client-server model)

- Basic understanding of TCP/IP

- What an API is and how to call one

- Command Line Comfort

- Running scripts and compiling programs

- Basic Unix commands (ls, cd, grep, curl)

- Environment variables and PATH

Helpful But Not Required

You’ll learn these concepts through the projects:

- Advanced cryptography (ECC, zero-knowledge proofs)

- Distributed systems theory (CAP theorem, Byzantine fault tolerance)

- Formal verification and security auditing

- Game theory and mechanism design

- Virtual machine design and bytecode interpretation

Self-Assessment Questions

Answer these to verify readiness:

- Can you explain what a hash function does in one sentence?

- Have you built a non-trivial project (500+ lines of code)?

- Can you debug a program using print statements or a debugger?

- Do you understand what “O(n log n)” means?

- Have you used Git for version control?

- Can you read and understand technical documentation?

If you answered “yes” to 4+ questions, you’re ready. If not, consider working through basic programming tutorials first.

Development Environment Setup

Required Tools:

- Language of choice: Rust (recommended), Go, Python, or JavaScript/TypeScript

- Code editor: VS Code, Vim, or any IDE with syntax highlighting

- Version control: Git installed and configured

- Terminal: Bash, Zsh, or equivalent Unix shell (WSL2 on Windows)

Recommended Tools:

- Blockchain explorers: Etherscan.io, Blockchain.com (for reference)

- Test networks: Access to Sepolia or Goerli Ethereum testnets

- Documentation: Ethereum Yellow Paper (reference), Solidity docs

- Visualization: Graphviz (for Merkle trees and block visualizations)

Optional but Helpful:

- Docker: For running local blockchain nodes

- Postman/curl: For testing JSON-RPC endpoints

- Jupyter notebooks: For interactive cryptography experiments (Python)

Time Investment

Realistic time estimates:

- Foundational projects (1-5): 1-2 weeks each (cryptography, blockchain basics)

- Intermediate projects (6-12): 2-3 weeks each (smart contracts, DeFi)

- Advanced projects (13-18): 3-4 weeks each (security, Layer 2, full client)

Total commitment: 4-6 months of focused, part-time work (10-15 hours/week)

This isn’t a weekend tutorial. Deep understanding requires building, debugging, and internalizing concepts over time.

Important Reality Check

What this learning path IS:

- ✅ Hands-on implementation of blockchain primitives from scratch

- ✅ Deep dive into “why” things work, not just “how” to use libraries

- ✅ Understanding cryptographic and economic guarantees

- ✅ Building intuition for security vulnerabilities and attack vectors

What this learning path is NOT:

- ❌ A get-rich-quick crypto trading guide

- ❌ A tutorial on using MetaMask and buying NFTs

- ❌ Copy-paste code snippets without understanding

- ❌ Shortcut to blockchain development jobs without fundamentals

If you want to truly understand Web3 at a systems level—what makes it secure, why certain design decisions were made, and how to reason about new protocols—this path is for you.

Overview

Web3 represents a paradigm shift from centralized to decentralized systems. To truly understand it, you must understand why it exists and how each component works at a fundamental level.

The Explosive Growth of Web3 (2025)

The blockchain industry has reached mainstream adoption with compelling statistics:

Market Size:

- Global blockchain market: $96.3 billion (2025), projected to reach $100+ billion by 2034 (47% CAGR)

- North America Web3 market: $3.4 billion (2025) → $100.1 billion by 2034 (45.8% CAGR)

Adoption:

- 560 million people (6.8% of global population) own cryptocurrency and use Web3 tools

- 820 million unique crypto wallets active globally

- 240 million active Web3 wallet users (19% year-over-year growth)

- 47% of global enterprises have blockchain in active deployment (not just pilots)

DeFi Ecosystem:

- $123.6 billion Total Value Locked (TVL) in DeFi protocols (41% YoY increase)

- Ethereum hosts 62% of all NFT contracts and transaction volume

- $40 billion locked in DAO treasuries

- 28% of Fortune 100 companies use enterprise-branded NFTs for loyalty programs

Developer Activity:

- $12.9 billion in VC funding for blockchain startups (first 5 months of 2025 alone)

- Over 6.2 million new smart contracts deployed in early 2025

This isn’t speculative anymore—it’s infrastructure powering billions in real economic activity.

Why Web3 Exists

The traditional web (Web2) has fundamental problems:

- Trust: You must trust centralized entities (banks, tech companies) not to manipulate data

- Censorship: Single points of control can deny access

- Ownership: You don’t truly own your digital assets; you rent access

- Privacy: Your data is harvested and monetized without consent

Web3 solves these through cryptographic guarantees and decentralized consensus—code that enforces rules without requiring trust in any party.

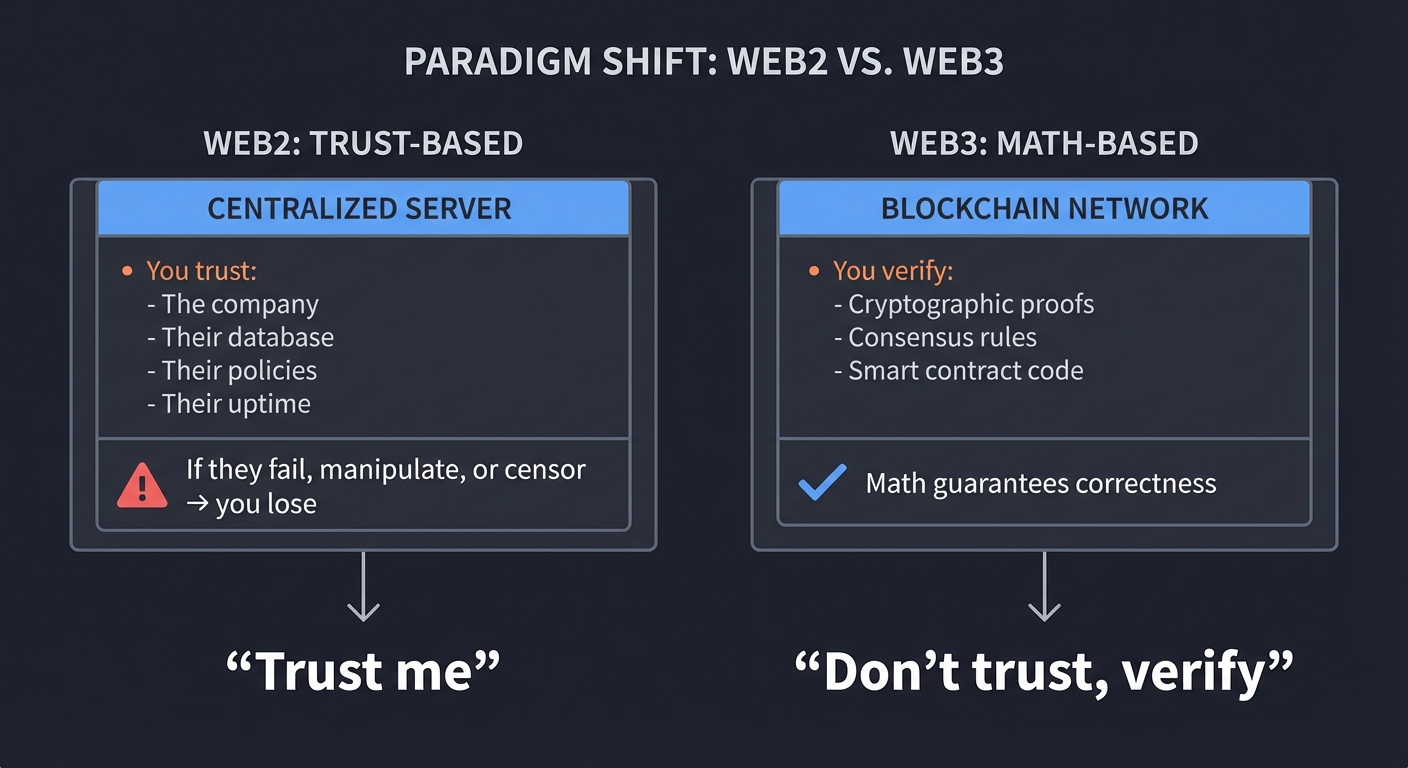

The Paradigm Shift

Web2 (Trust-Based) Web3 (Math-Based)

┌─────────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────────┐

│ Centralized Server │ │ Blockchain Network │

│ │ │ │

│ You trust: │ │ You verify: │

│ - The company │ │ - Cryptographic │

│ - Their database │ │ proofs │

│ - Their policies │ │ - Consensus rules │

│ - Their uptime │ │ - Smart contract │

│ │ │ code │

│ If they fail, │ │ │

│ manipulate, or │ │ Math guarantees │

│ censor → you lose │ │ correctness │

└─────────────────────┘ └─────────────────────┘

↓ ↓

"Trust me" "Don't trust,

verify"

This shift is profound: Web3 replaces institutional trust with mathematical certainty.

Cryptographic Foundations: The Building Blocks

Before blockchains can exist, we need cryptographic primitives that provide specific guarantees. These are the mathematical tools that make trustless systems possible.

Hash Functions: One-Way Fingerprints

A cryptographic hash function takes arbitrary input and produces a fixed-size output (digest) with three critical properties:

- Deterministic: Same input always produces same output

- One-way: Cannot reverse hash to find input (pre-image resistance)

- Avalanche effect: Changing one bit flips ~50% of output bits

Input: "Hello World"

SHA-256 Output: a591a6d40bf420404a011733cfb7b190d62c65bf0bcda32b57b277d9ad9f146e

Input: "hello World" (lowercase 'h')

SHA-256 Output: 8663bab6d124806b9727f89bb4ab9db4cbcc3862f6bbf22024dfa7212afa964f

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

(Notice: 32 of 64 characters changed = 50% different)

Why this matters for Web3:

- Block hashing: Each block’s hash depends on all its contents

- Transaction IDs: Every transaction gets a unique, verifiable identifier

- Mining: Proof-of-Work is finding a hash below a target value

- Merkle trees: Efficiently prove transaction inclusion without downloading entire blocks

Real-world security: Bitcoin’s blockchain uses SHA-256. To reverse a single block hash would require 2^256 operations—more energy than exists in the known universe.

SHA-256 remains the industry standard, though SHA-3 (Keccak, chosen by NIST in 2012) and BLAKE3 offer faster alternatives with equal security. Ethereum used Keccak-256 for its hashing needs.

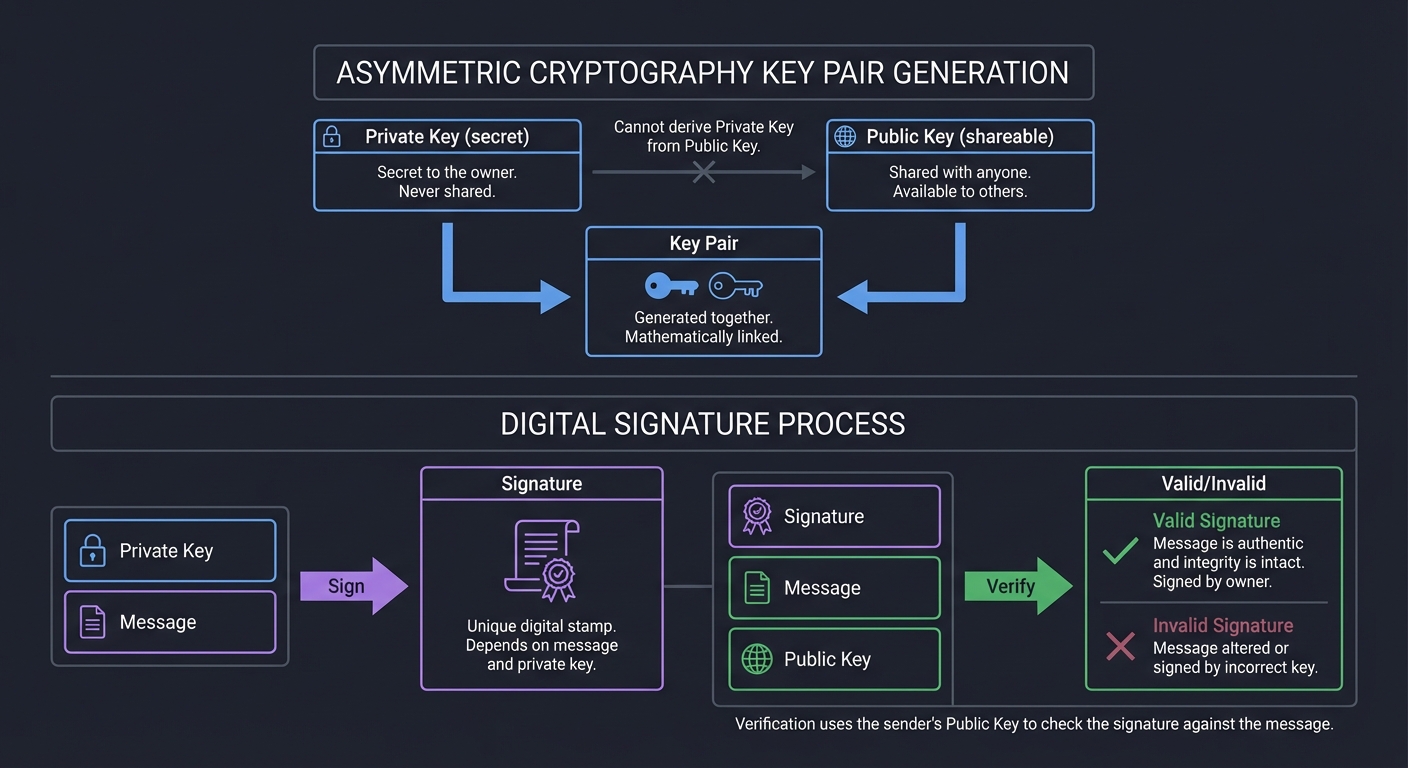

Digital Signatures: Proving Ownership Without Revealing Secrets

Digital signatures solve the problem: “How do I prove I own an account without revealing my private key?”

Asymmetric Cryptography:

Private Key (secret) ──┐

├──> Key Pair

Public Key (shareable)──┘

Private Key + Message ───> Signature

Signature + Message + Public Key ───> Valid/Invalid

The Magic:

- Only the private key can create valid signatures

- Anyone with the public key can verify signatures

- The public key cannot derive the private key (discrete logarithm problem)

Web3 Application:

Transaction Structure:

{

from: "0x742d35Cc6634C0532925a3b844Bc454e4438f44e" (derived from public key)

to: "0x5aAeb6053F3E94C9b9A09f33669435E7Ef1BeAed"

value: 1.5 ETH

nonce: 42

signature: r=0x8f3d..., s=0x4e2a..., v=27

}

The signature proves:

1. The sender owns the private key for that address

2. This exact transaction was authorized (can't be modified)

3. The transaction can't be replayed (nonce prevents this)

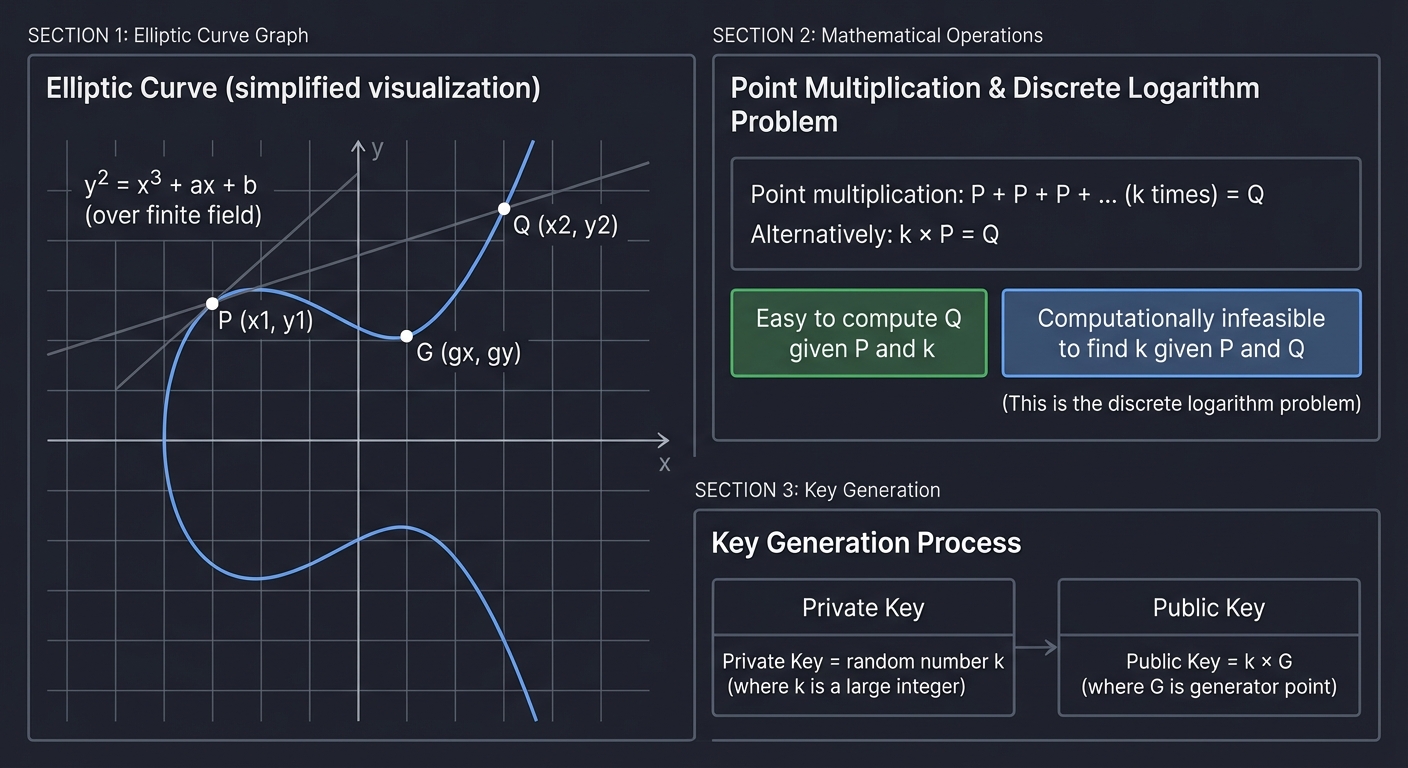

Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC): Both Bitcoin and Ethereum use SECP256k1 curve. Why?

- Smaller keys (256-bit ECC = 3072-bit RSA security)

- Faster signature generation/verification

- Well-studied and cryptanalytically sound

Elliptic Curve (simplified visualization):

y

│

────┼────────────────────

│ ╱╲

│ ╱ ╲

│ ╱ ╲

────┼──╱ ╲─────────

│ ╱ ╲

│╱ ╲

────┼────────────╲────── x

│ ╲

│ ╲

Point multiplication: P + P + P + ... (k times) = Q

- Easy to compute Q given P and k

- Computationally infeasible to find k given P and Q

(This is the discrete logarithm problem)

Private Key = random number k

Public Key = k × G (where G is generator point)

Security note: Ethereum’s wallet addresses are the last 20 bytes of the Keccak-256 hash of the public key. This adds another layer—even if ECDLP were broken, attackers would still need to reverse the hash.

Blockchain Data Structures: Building Tamper-Proof Chains

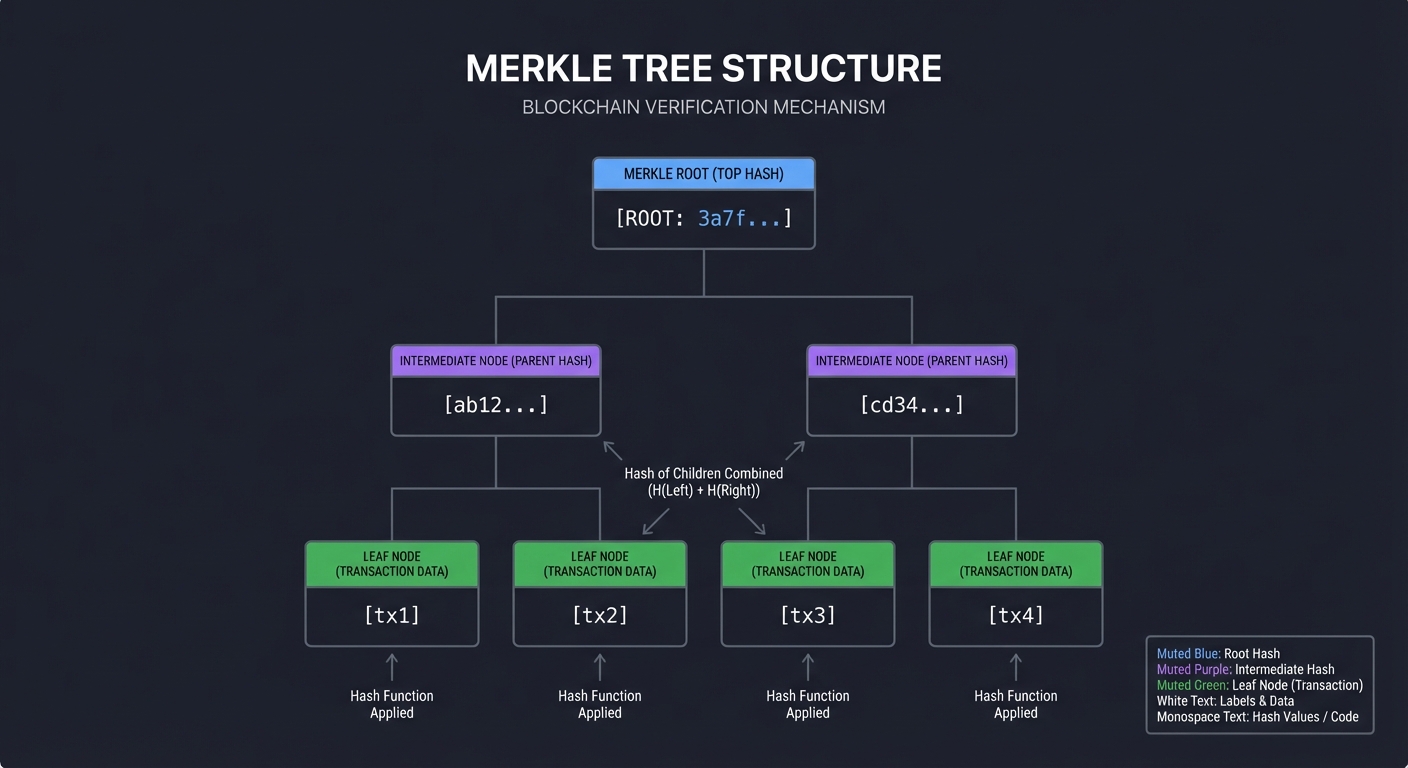

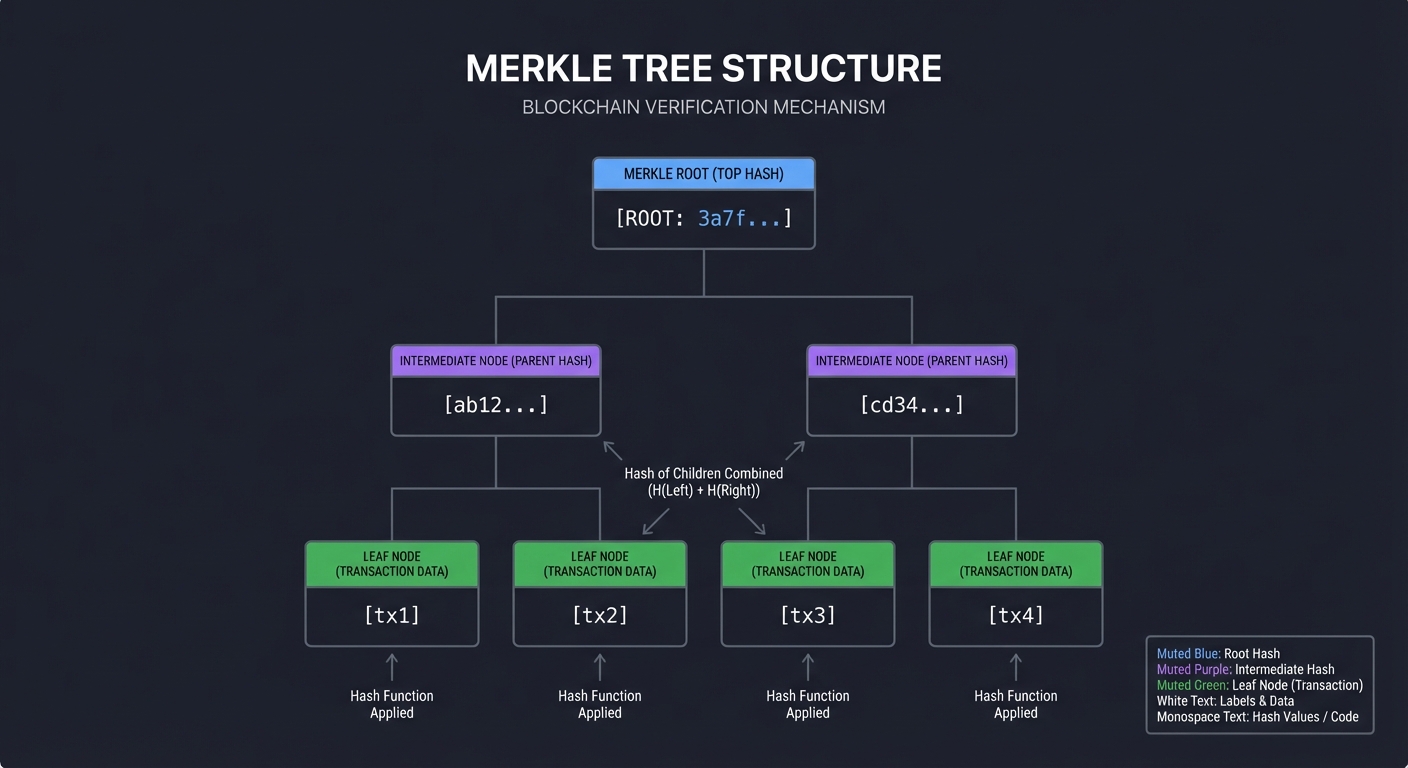

Merkle Trees: Efficient Proof of Inclusion

A Merkle tree allows you to prove a transaction exists in a block without downloading the entire block.

Root Hash

/ \

/ \

Hash(A+B) Hash(C+D)

/ \ / \

/ \ / \

Hash(A) Hash(B) Hash(C) Hash(D)

| | | |

Tx A Tx B Tx C Tx D

To prove Tx B is in the block, you only need:

- Tx B

- Hash(A)

- Hash(C+D)

Then verify:

1. Hash(B) → compute

2. Hash(A+B) = Hash(Hash(A) + Hash(B)) → compute

3. Root = Hash(Hash(A+B) + Hash(C+D)) → compare with block's root

This reduces proof size from O(n) to O(log n)

Real-world impact: Bitcoin blocks contain ~2,000 transactions. Instead of downloading 2MB, you can verify inclusion with ~384 bytes (12 hashes × 32 bytes).

Ethereum uses a more advanced structure called a Merkle Patricia Trie for its state tree, allowing efficient updates and proofs for account balances and contract storage.

Block Structure: Linking History with Hashes

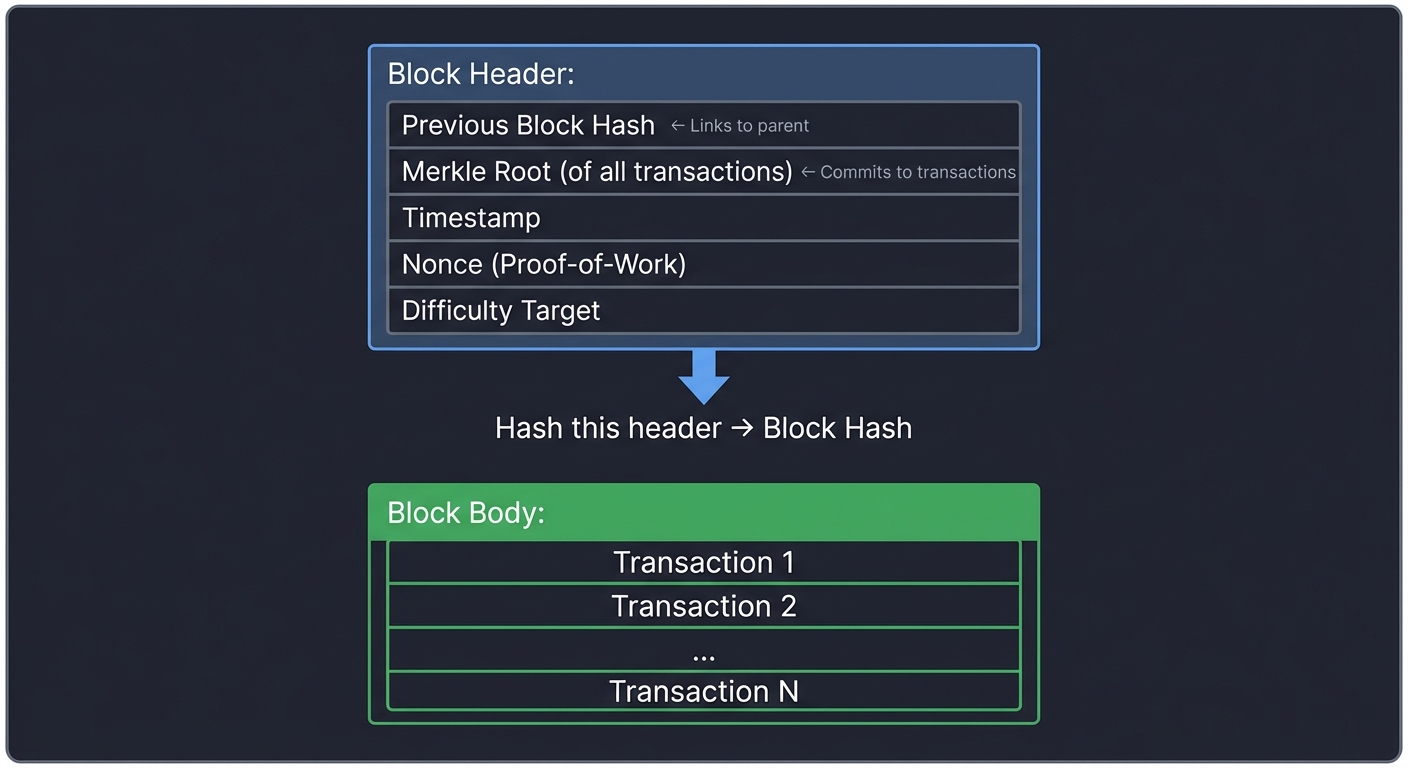

Each block contains:

Block Header:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Previous Block Hash │ ← Links to parent

│ Merkle Root (of all transactions) │ ← Commits to transactions

│ Timestamp │

│ Nonce (Proof-of-Work) │

│ Difficulty Target │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

├─> Hash this header → Block Hash

│

Block Body:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Transaction 1 │

│ Transaction 2 │

│ ... │

│ Transaction N │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────┘

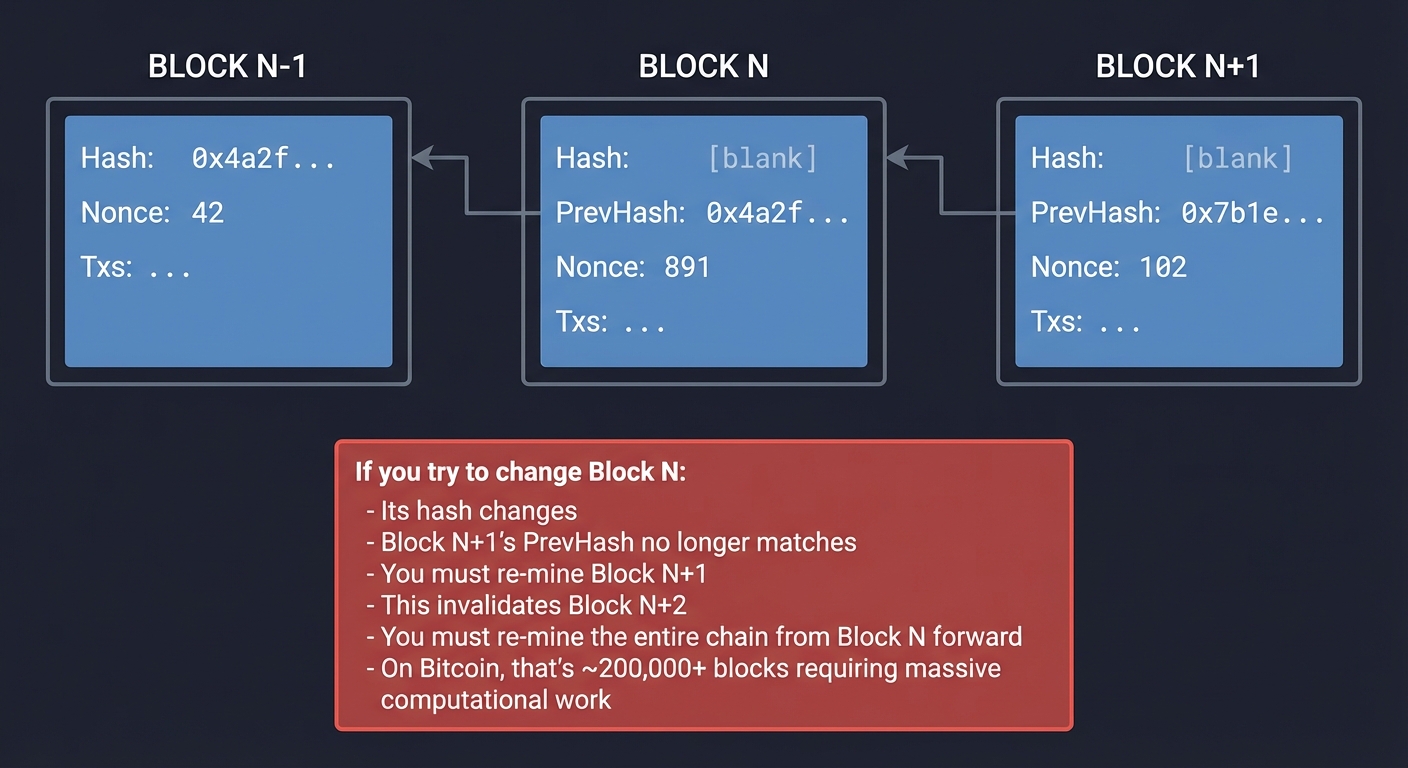

Why this creates immutability:

Block N-1 Block N Block N+1

┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐

│ Hash: │ │ Hash: │ │ Hash: │

│ 0x4a2f...│◄───┤ PrevHash:│◄───┤ PrevHash:│

│ │ │ 0x4a2f...│ │ 0x7b1e...│

│ Nonce: 42│ │ Nonce:891│ │ Nonce:102│

│ Txs: ... │ │ Txs: ... │ │ Txs: ... │

└──────────┘ └──────────┘ └──────────┘

If you try to change Block N:

- Its hash changes

- Block N+1's PrevHash no longer matches

- You must re-mine Block N+1

- This invalidates Block N+2

- You must re-mine the entire chain from Block N forward

- On Bitcoin, that's ~200,000+ blocks requiring massive computational work

This is why blockchains are append-only: modifying history requires redoing all subsequent work.

Consensus Mechanisms: Agreement Without Authority

The core challenge: How do thousands of untrusted nodes agree on a single version of history?

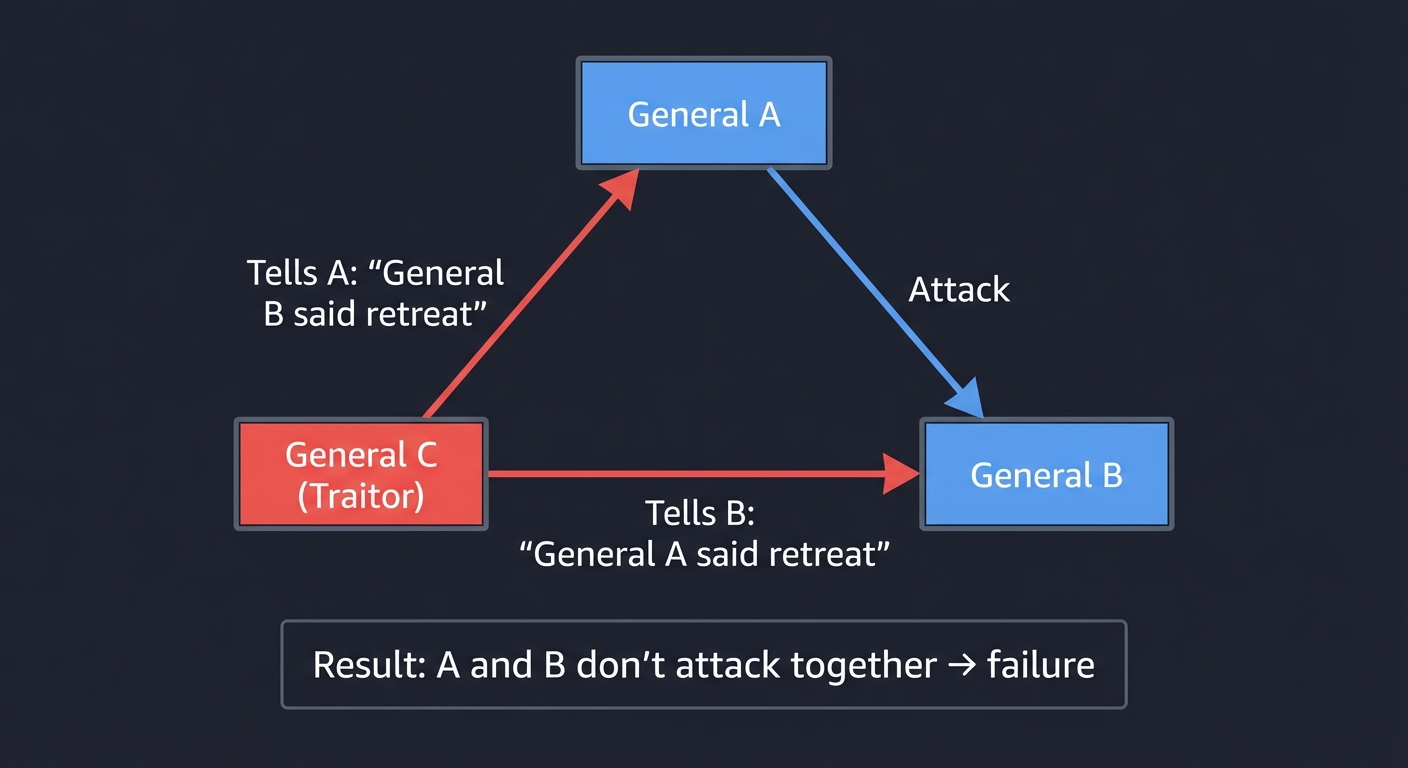

The Byzantine Generals Problem

General A General B

│ │

├─── "Attack" ────┤

│ │

General C (Traitor)

│

├─── Tells A: "General B said retreat"

└─── Tells B: "General A said retreat"

Result: A and B don't attack together → failure

The problem: In distributed systems, nodes may be faulty (crash) or malicious (Byzantine). How do you achieve consensus when you can’t trust messages?

Proof-of-Work (PoW): Making Dishonesty Expensive

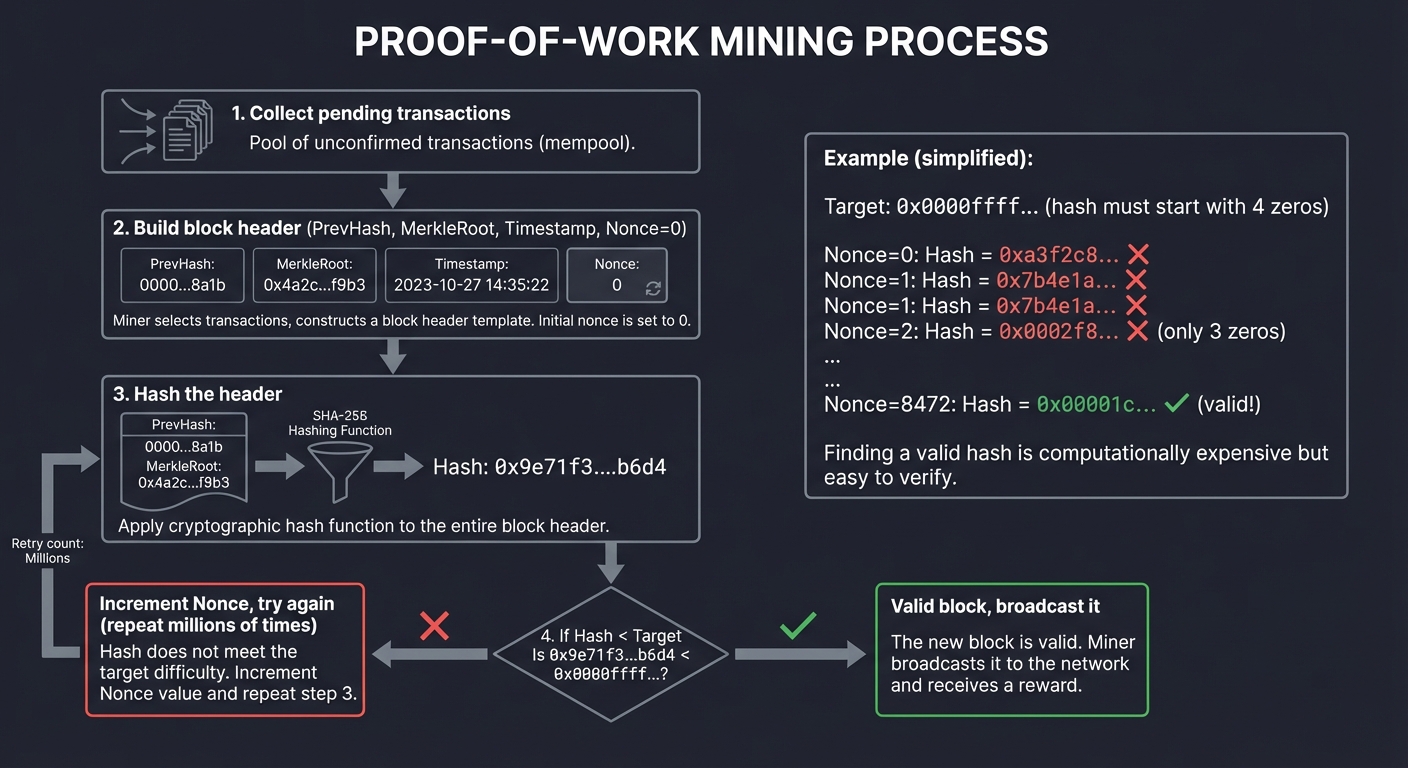

Bitcoin’s solution: Make creating blocks computationally expensive.

Mining Process:

1. Collect pending transactions

2. Build block header (PrevHash, MerkleRoot, Timestamp, Nonce=0)

3. Hash the header

4. If Hash < Target → valid block, broadcast it

Else increment Nonce, try again (repeat millions of times)

Example (simplified):

Target: 0x0000ffff... (hash must start with 4 zeros)

Nonce=0: Hash = 0xa3f2c8... ✗

Nonce=1: Hash = 0x7b4e1a... ✗

Nonce=2: Hash = 0x0002f8... ✗ (only 3 zeros)

...

Nonce=8472: Hash = 0x00001c... ✓ (valid!)

Why this works:

- Creating a valid block requires ~10 minutes of global mining power (billions of hashes)

- To rewrite history, you need to re-mine faster than the rest of the network combined

- Attacking costs more than the rewards (economic disincentive)

The 51% attack: If an attacker controls >50% of mining power, they can rewrite history. This is why decentralization matters—no single entity should have majority power.

Bitcoin’s difficulty adjustment: Every 2,016 blocks (~2 weeks), the network adjusts the difficulty target to maintain ~10-minute block times, regardless of total mining power.

Proof-of-Stake (PoS): Making Dishonesty Self-Destructive

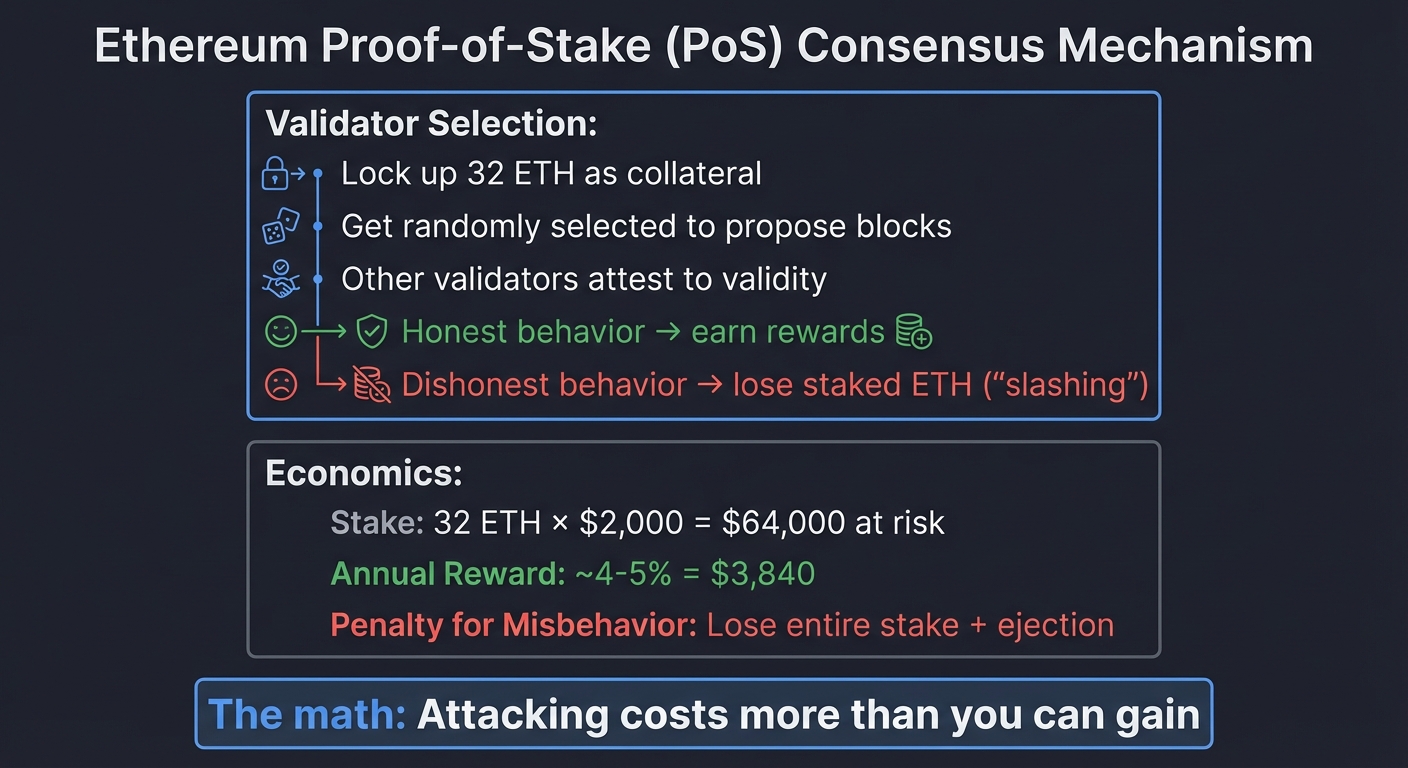

Ethereum 2.0’s approach: Replace computational work with economic stake.

Validator Selection:

- Lock up 32 ETH as collateral

- Get randomly selected to propose blocks

- Other validators attest to validity

- Honest behavior → earn rewards

- Dishonest behavior → lose staked ETH ("slashing")

Economics:

Stake: 32 ETH × $3,000 = $96,000 at risk

Annual Reward: ~4-5% = $3,840

Penalty for Misbehavior: Lose entire stake + ejection

The math: Attacking costs more than you can gain

Advantages over PoW:

- 99.95% less energy consumption

- Faster finality (blocks confirmed in minutes, not hours)

- More secure (costs $96,000 per validator to attack vs. buying mining hardware)

The “Nothing at Stake” problem: In PoS, validators could theoretically vote on multiple forks (no computational cost). Ethereum solves this with slashing—validators who sign conflicting blocks lose their stake.

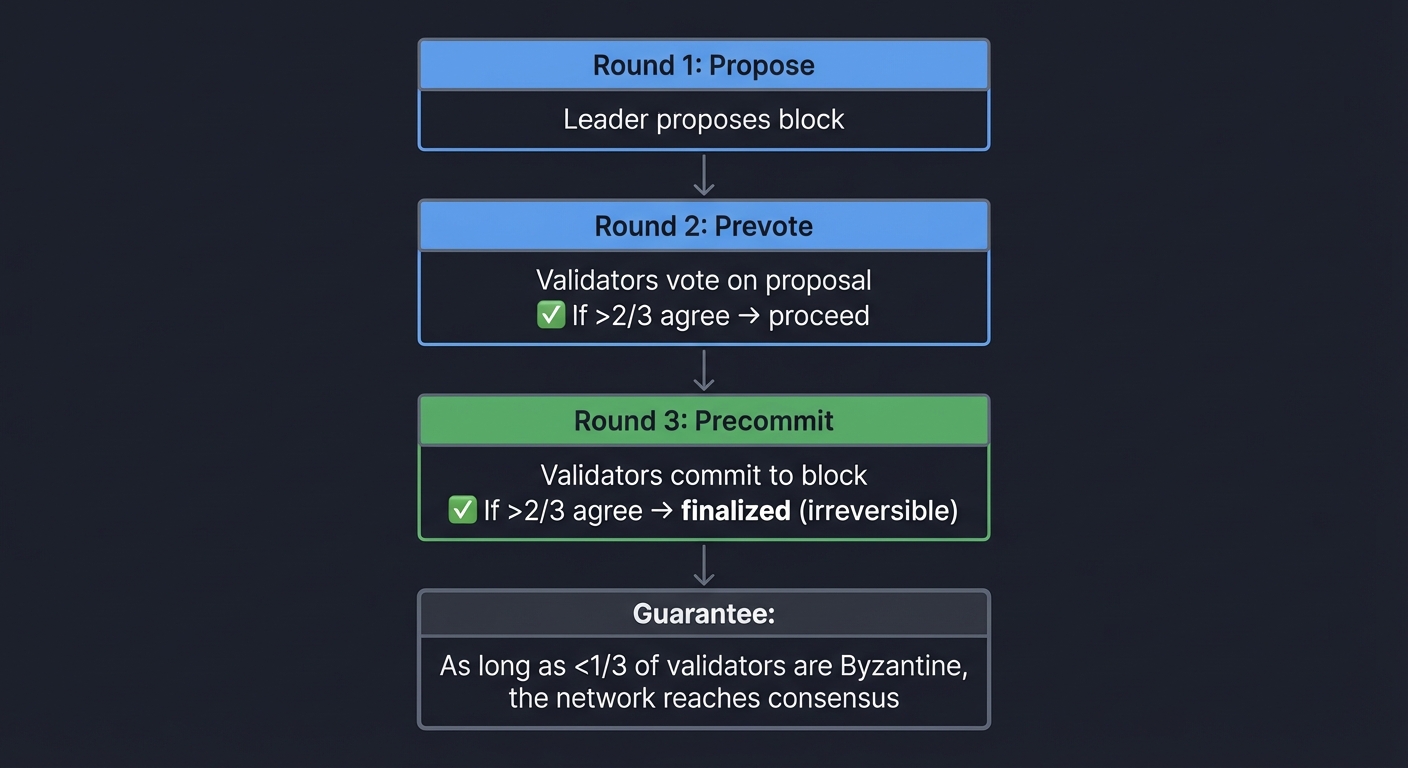

Byzantine Fault Tolerance (BFT)

Practical BFT algorithms (like Tendermint, used in Cosmos) guarantee finality:

Round 1: Propose

- Leader proposes block

Round 2: Prevote

- Validators vote on proposal

- If >2/3 agree → proceed

Round 3: Precommit

- Validators commit to block

- If >2/3 agree → finalized (irreversible)

Guarantee: As long as <1/3 of validators are Byzantine,

the network reaches consensus

Tradeoff: BFT requires knowing the validator set (permissioned or semi-permissioned), whereas PoW/PoS are fully permissionless.

Smart Contracts and the Ethereum Virtual Machine

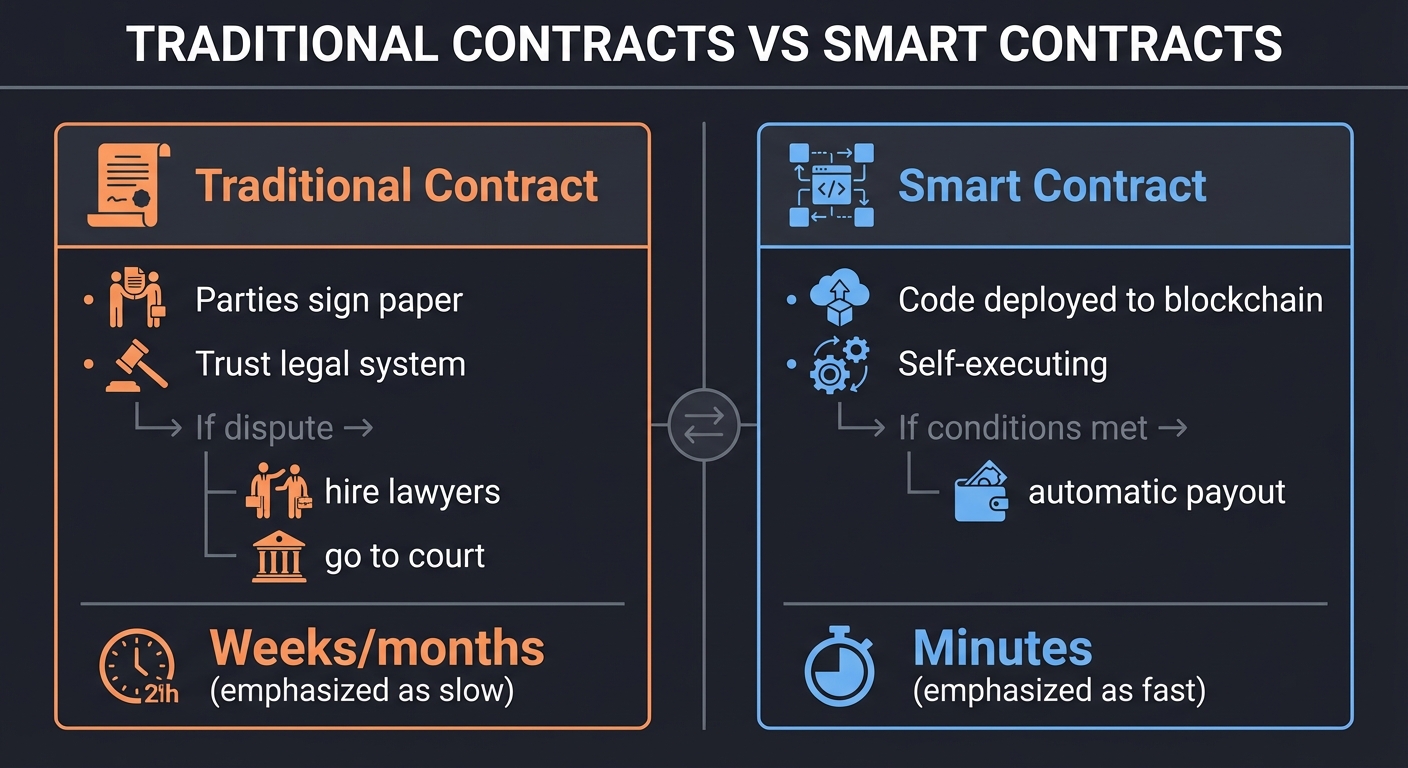

What Is a Smart Contract?

A smart contract is code that runs on a blockchain, making it:

- Immutable: Once deployed, cannot be changed

- Deterministic: Same inputs always produce same outputs

- Trustless: Execution is verified by all nodes

Traditional Contract Smart Contract

┌────────────────────┐ ┌────────────────────┐

│ Parties sign paper │ │ Code deployed to │

│ Trust legal system │ │ blockchain │

│ If dispute → │ │ Self-executing │

│ hire lawyers │ │ If conditions met →│

│ go to court │ │ automatic payout │

│ Weeks/months │ │ Minutes │

└────────────────────┘ └────────────────────┘

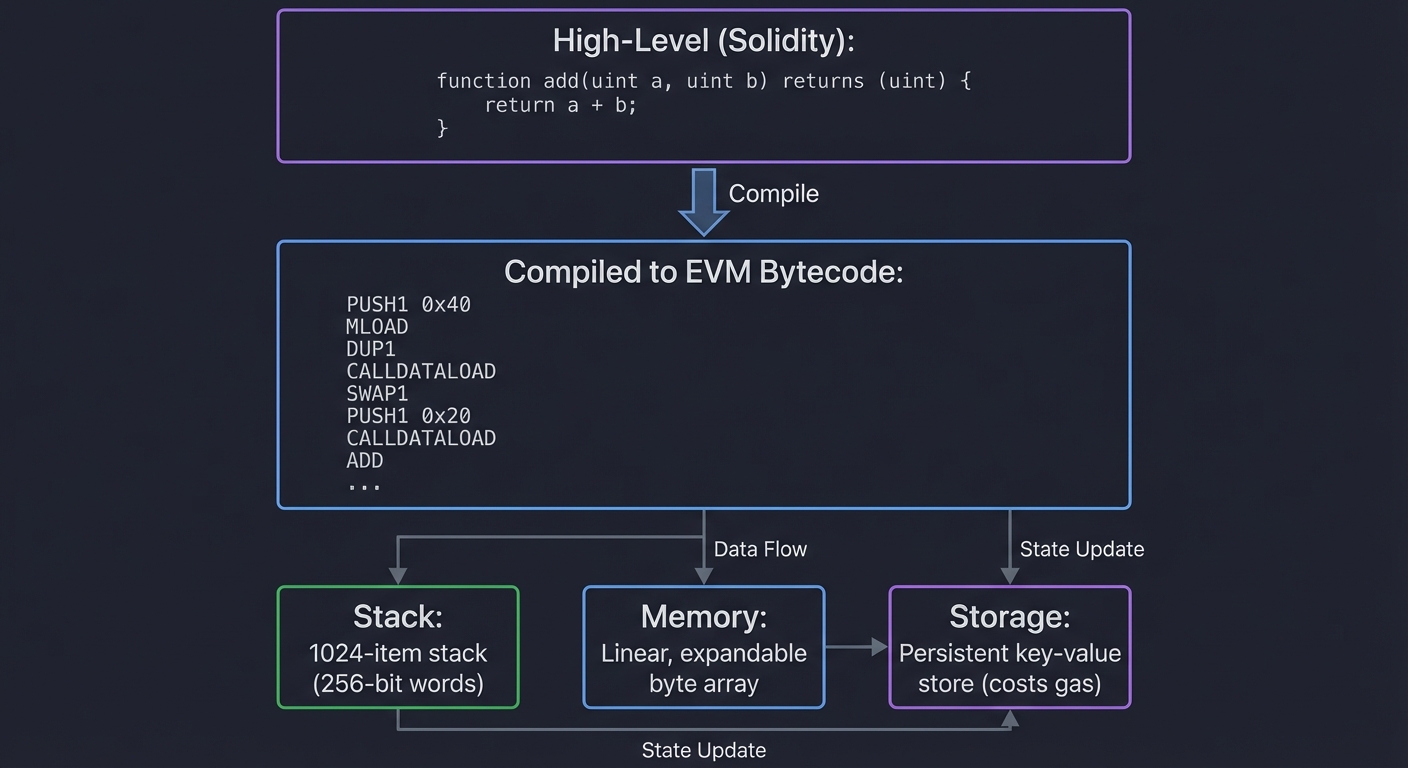

The Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM)

The EVM is a stack-based virtual machine that executes bytecode:

High-Level (Solidity):

function add(uint a, uint b) returns (uint) {

return a + b;

}

Compiled to EVM Bytecode:

PUSH1 0x40 // Stack: [0x40]

MLOAD // Stack: [mem[0x40]]

DUP1 // Stack: [mem[0x40], mem[0x40]]

CALLDATALOAD // Stack: [a, mem[0x40]]

SWAP1 // Stack: [mem[0x40], a]

PUSH1 0x20

CALLDATALOAD // Stack: [b, mem[0x40], a]

ADD // Stack: [a+b, mem[0x40]]

...

Execution:

- Stack: 1024-item stack (256-bit words)

- Memory: Linear, expandable byte array

- Storage: Persistent key-value store (costs gas)

Why bytecode matters: Every node must execute contracts identically. Bytecode ensures determinism across different hardware/software.

Gas: Metering Computation

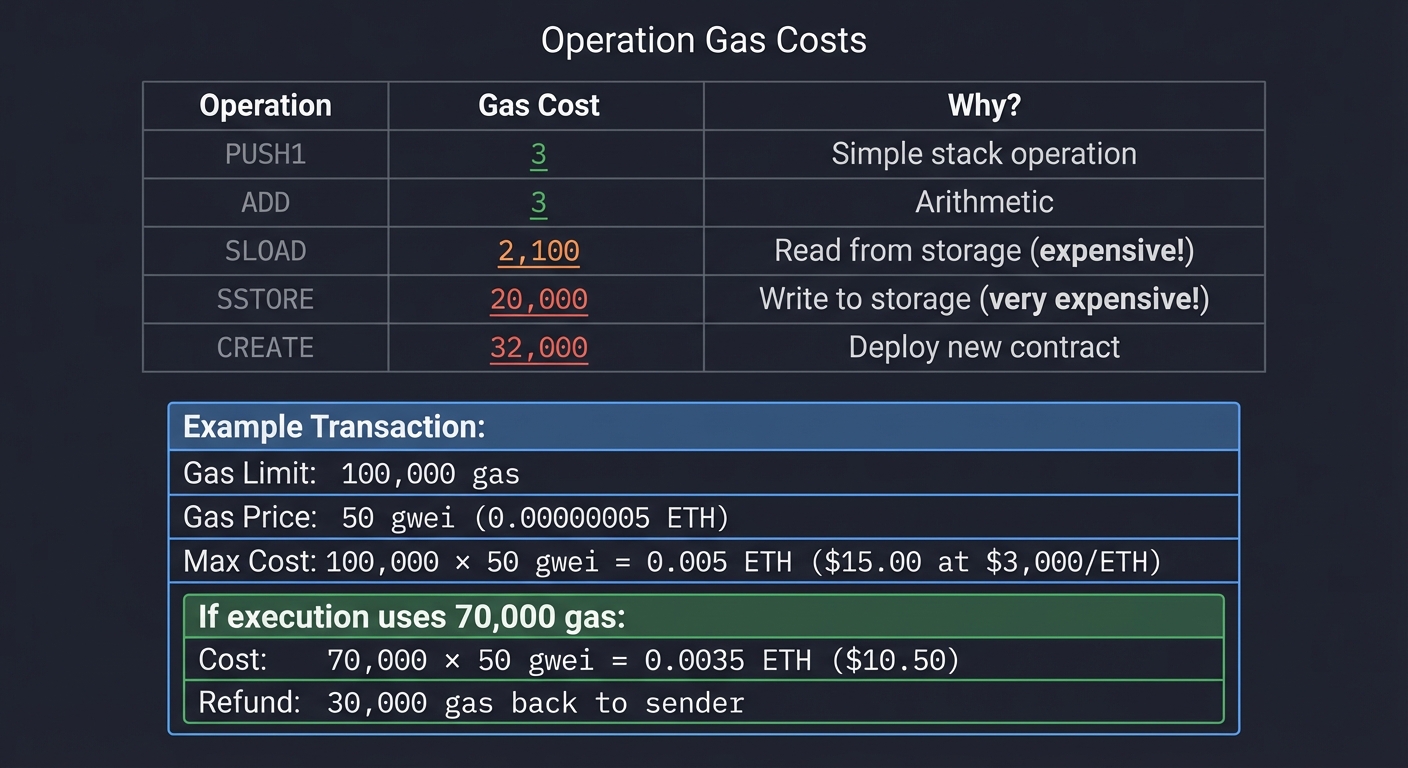

Every operation costs “gas” to prevent infinite loops and spam:

Operation Gas Cost Why?

─────────────────────────────────────────────────────

PUSH1 3 Simple stack operation

ADD 3 Arithmetic

SLOAD 2,100 Read from storage (expensive!)

SSTORE 20,000 Write to storage (very expensive!)

CREATE 32,000 Deploy new contract

Example Transaction:

Gas Limit: 100,000 gas

Gas Price: 50 gwei (0.00000005 ETH)

Max Cost: 100,000 × 50 gwei = 0.005 ETH ($15 at $3,000/ETH)

If execution uses 70,000 gas:

Cost: 70,000 × 50 gwei = 0.0035 ETH ($10.50)

Refund: 30,000 gas back to sender

Design rationale:

- Storage is expensive because it’s replicated across thousands of nodes

- Computation is cheaper but still metered to prevent abuse

- Users pay for resource consumption, aligning incentives

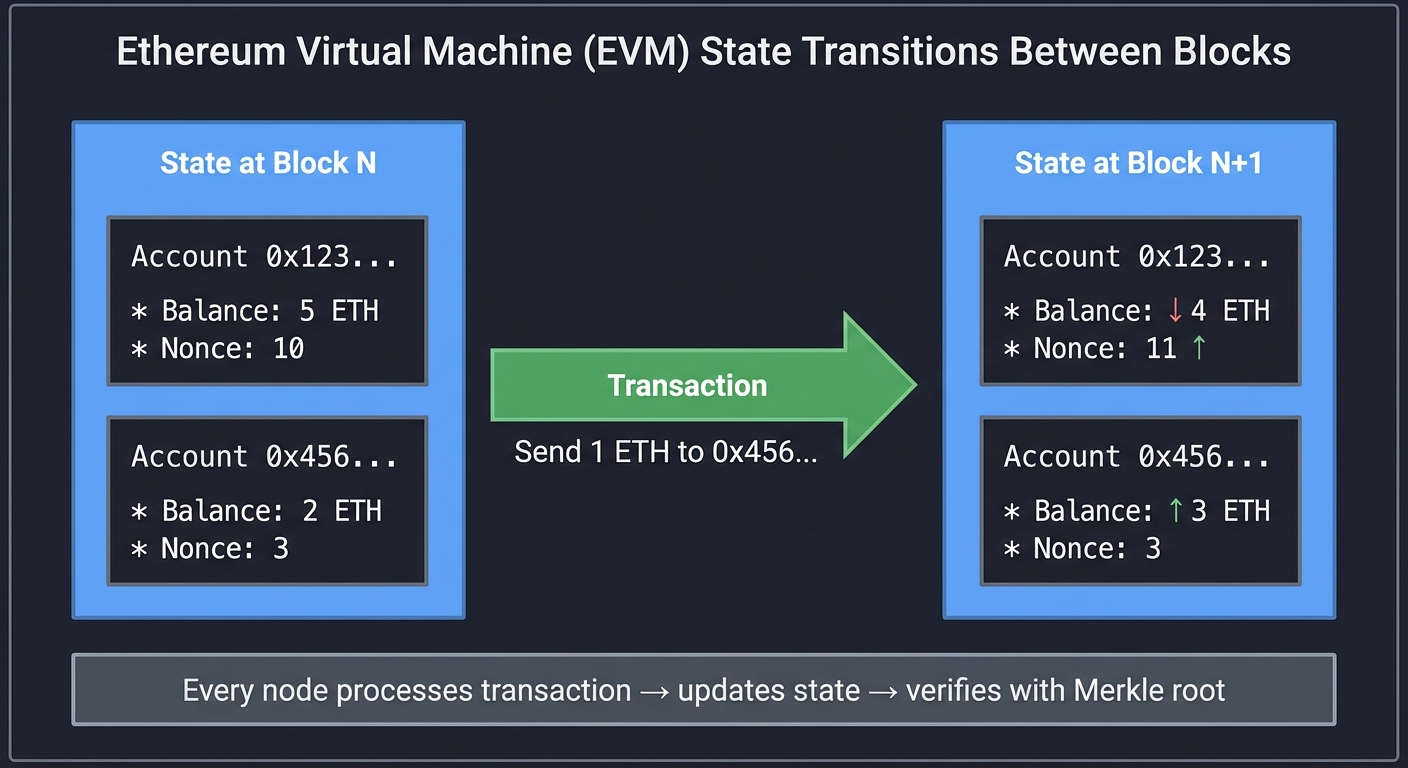

EVM State Transitions

State at Block N Transaction State at Block N+1

┌──────────────────┐ ┌──────────────────┐

│ Account 0x123... │ │ Account 0x123... │

│ Balance: 5 ETH │─── Send 1 ETH ───────> │ Balance: 4 ETH │

│ Nonce: 10 │ to 0x456... │ Nonce: 11 │

│ │ │ │

│ Account 0x456... │ │ Account 0x456... │

│ Balance: 2 ETH │ │ Balance: 3 ETH │

│ Nonce: 3 │ │ Nonce: 3 │

└──────────────────┘ └──────────────────┘

Every node processes transaction → updates state → verifies with Merkle root

World State: Ethereum maintains a giant Merkle Patricia Trie mapping addresses to account states. Every block’s header commits to this state root, allowing verification.

Decentralized Finance (DeFi): Programmable Money

DeFi recreates financial primitives (lending, trading, derivatives) as smart contracts.

Automated Market Makers (AMMs)

Traditional exchanges use order books. AMMs use liquidity pools and math:

Uniswap's Constant Product Formula:

x × y = k (where k is constant)

Liquidity Pool:

1,000 ETH × 3,000,000 USDC = 3,000,000,000 (constant)

If someone buys 100 ETH:

New ETH balance: 1,000 - 100 = 900

New USDC balance: 3,000,000,000 / 900 = 3,333,333

USDC paid: 3,333,333 - 3,000,000 = 333,333

Effective price: 333,333 / 100 = 3,333 USDC per ETH

(Higher than starting price due to slippage)

Why this matters: No order books, no centralized matching engine. Pure math executed by smart contracts.

Lending Protocols

Platforms like Aave let you lend/borrow without intermediaries:

Lender: Borrower:

Deposit 100 ETH Deposit 50 ETH (collateral)

↓ Borrow 30 ETH (60% LTV)

Earn 4% APY ↓

Withdraw anytime Pay 6% APY

If ETH price drops →

Liquidation (collateral sold)

Overcollateralization: You must deposit more than you borrow. Why? Smart contracts can’t chase you down for repayment—they need collateral they can liquidate.

Flash Loans: Borrow Millions for One Transaction

A unique DeFi innovation:

Single Transaction:

1. Borrow 10,000 ETH from Aave (no collateral)

2. Trade on Exchange A (exploit price difference)

3. Trade on Exchange B (arbitrage)

4. Repay 10,000 ETH + 0.09% fee

5. Keep the profit

If you can't repay → entire transaction reverts

(Atomicity: all-or-nothing execution)

Why this works: The EVM processes transactions atomically. If step 4 fails, steps 1-3 are undone.

Real-world stats (2025): Ethereum hosts over $78 billion in DeFi TVL, with smart contract interactions accounting for 62% of daily transactions.

Security Considerations: Where Things Go Wrong

Reentrancy Attacks

The infamous DAO hack (2016) exploited this:

// Vulnerable contract:

function withdraw(uint amount) public {

require(balances[msg.sender] >= amount);

msg.sender.call.value(amount)(""); // External call BEFORE state update

balances[msg.sender] -= amount; // Vulnerable!

}

// Attacker's contract:

function attack() public {

victim.withdraw(1 ether);

}

function () payable { // Fallback function

if (address(victim).balance >= 1 ether) {

victim.withdraw(1 ether); // Re-enter before balance is updated!

}

}

Execution:

1. Attacker calls withdraw(1 ETH)

2. Victim sends 1 ETH → triggers attacker's fallback

3. Attacker's fallback calls withdraw again (balance not yet updated!)

4. Victim sends another 1 ETH

5. Repeat until drained

Fix: Update state before external calls (Checks-Effects-Interactions pattern).

Oracle Manipulation

Smart contracts can’t access external data (stock prices, weather, etc.). They rely on “oracles”:

Problem:

Smart contract needs ETH price

↓

Query single oracle (centralized!)

↓

Oracle provides price

↓

If oracle is hacked/malicious → contract uses wrong price

Solution (Chainlink):

Query multiple independent oracles

↓

Aggregate answers (median)

↓

Decentralized price feed

Real attack (2020): Harvest Finance lost $24M because an attacker manipulated Curve pool prices by executing massive trades, making the oracle report false prices.

Integer Overflow/Underflow

Before Solidity 0.8.0:

uint8 maxValue = 255;

maxValue = maxValue + 1; // Wraps to 0 (overflow)

uint8 minValue = 0;

minValue = minValue - 1; // Wraps to 255 (underflow)

Impact: The BeautyChain (BEC) token hack (2018) used overflow to mint billions of tokens.

Fix: Solidity 0.8.0+ has automatic overflow checks (reverts on overflow).

Front-Running

Attackers watch the mempool (pending transactions) and insert their own with higher gas:

Mempool:

1. Alice: Buy 100 ETH at 3,000 USDC (gas: 50 gwei)

2. Bob (attacker) sees this → submits:

- Buy 100 ETH at 3,001 USDC (gas: 60 gwei) ← Executes first

- Sell 100 ETH at 3,050 USDC (gas: 50 gwei) ← Executes after Alice

Result: Bob profits from Alice's price impact

Mitigation: Use private mempools (Flashbots), slippage protection, or commit-reveal schemes.

Concept Summary Table

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize |

|---|---|

| Cryptographic Hash Functions | One-way, deterministic, avalanche effect. These create tamper-proof links between blocks and enable efficient Merkle proofs. |

| Digital Signatures (ECDSA) | Prove ownership without revealing private keys. Signatures can’t be forged, reused, or modified. This is how transactions prove authorization. |

| Merkle Trees | Hierarchical hashing for efficient proofs. Verify transaction inclusion with O(log n) data instead of O(n). |

| Blockchain Structure | Each block’s hash depends on its contents and the previous block’s hash. Changing history requires redoing all subsequent work (immutability). |

| Proof-of-Work (PoW) | Consensus through computational puzzles. Attacking requires majority hashpower (51% attack). Economic security through sunk energy costs. |

| Proof-of-Stake (PoS) | Consensus through economic stake. Validators risk their collateral (slashing). More energy-efficient, faster finality than PoW. |

| Byzantine Fault Tolerance | Achieving consensus when <1/3 of nodes are faulty/malicious. BFT algorithms guarantee finality but require known validator sets. |

| EVM & Bytecode | Stack-based VM executing deterministic bytecode. Every node must produce identical results. Operations cost gas to prevent spam/loops. |

| Gas Economics | Computation and storage aren’t free. Users pay for resources consumed. This aligns incentives and prevents network abuse. |

| Smart Contract Security | Reentrancy, oracle manipulation, overflow, front-running. Immutability means bugs are permanent. Security requires deep understanding. |

| DeFi Primitives | AMMs use math (x×y=k) instead of order books. Lending requires overcollateralization. Flash loans exploit transaction atomicity. |

| Decentralization Tradeoffs | Speed vs. decentralization vs. security (blockchain trilemma). Every design choice involves tradeoffs between these three properties. |

Deep Dive Reading by Concept

This section maps each concept cluster to specific book chapters for deeper understanding. Read these before or alongside the projects to build strong mental models.

Cryptographic Foundations

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Hash function properties and security | Serious Cryptography, 2nd Edition by Jean-Philippe Aumasson — Ch. 6: “Hash Functions” |

| SHA-256 implementation details | Understanding Cryptography by Christof Paar and Jan Pelzl — Ch. 11: “Hash Functions” |

| Digital signatures and ECDSA | Serious Cryptography, 2nd Edition by Jean-Philippe Aumasson — Ch. 10: “Digital Signatures” |

| Elliptic curve cryptography | An Introduction to Mathematical Cryptography by Jeffrey Hoffstein et al. — Ch. 6: “Elliptic Curves” |

| Zero-knowledge proofs (advanced) | Proofs, Arguments, and Zero-Knowledge by Justin Thaler — Ch. 1-3: Foundations |

Blockchain Data Structures

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Merkle trees and Patricia tries | Mastering Ethereum by Andreas Antonopoulos and Gavin Wood — Ch. 7: “Smart Contracts and Solidity” (section on data structures) |

| Blockchain structure and linking | Mastering Bitcoin, 3rd Edition by Andreas Antonopoulos — Ch. 9: “The Blockchain” |

| Data structures for blockchain | Algorithms, Fourth Edition by Robert Sedgewick and Kevin Wayne — Ch. 3: “Searching” (binary trees and hash tables) |

| Byzantine fault tolerance | Distributed Systems, 3rd Edition by Maarten van Steen and Andrew S. Tanenbaum — Ch. 8: “Fault Tolerance” |

Consensus Mechanisms

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Proof-of-Work mechanics | Mastering Bitcoin, 3rd Edition by Andreas Antonopoulos — Ch. 10: “Mining and Consensus” |

| Proof-of-Stake and Ethereum 2.0 | The Infinite Machine by Camila Russo — Part III: “The Pivot” (historical context of PoS transition) |

| Consensus algorithms overview | Blockchain Basics by Daniel Drescher — Ch. 7-9: Consensus mechanisms |

| Distributed consensus theory | Distributed Systems, 3rd Edition by Maarten van Steen and Andrew S. Tanenbaum — Ch. 6: “Coordination” |

| CAP theorem and tradeoffs | Designing Data-Intensive Applications, 2nd Edition by Martin Kleppmann — Ch. 9: “Consistency and Consensus” |

Smart Contracts and the EVM

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| EVM architecture and opcodes | Mastering Ethereum by Andreas Antonopoulos and Gavin Wood — Ch. 13: “The Ethereum Virtual Machine” |

| Solidity programming fundamentals | Mastering Ethereum by Andreas Antonopoulos and Gavin Wood — Ch. 7: “Smart Contracts and Solidity” |

| Gas mechanics and optimization | Ethereum for Web Developers by Patricio Palladino — Ch. 5: “Gas and Transactions” |

| Stack-based VM design | Virtual Machines by James E. Smith and Ravi Nair — Ch. 2: “High-Level Virtual Machines” |

DeFi and Economics

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Automated market makers | How to DeFi: Advanced by CoinGecko — Ch. 2: “Decentralized Exchanges” |

| Lending protocols and overcollateralization | How to DeFi: Advanced by CoinGecko — Ch. 3: “Lending and Borrowing” |

| Token economics and incentive design | Token Economy by Shermin Voshmgir — Ch. 4: “Cryptoeconomics & Governance” |

| Game theory in blockchain | Blockchain and the Law by Primavera De Filippi and Aaron Wright — Ch. 3: “Smart Contracts” |

Security and Attack Vectors

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Smart contract vulnerabilities | Mastering Ethereum by Andreas Antonopoulos and Gavin Wood — Ch. 9: “Smart Contract Security” |

| Reentrancy and common exploits | Smart Contract Security Field Guide by OpenZeppelin — All chapters (comprehensive security patterns) |

| Cryptographic attack models | Serious Cryptography, 2nd Edition by Jean-Philippe Aumasson — Ch. 3: “Block Ciphers” (attack methodologies) |

| Oracle problems and solutions | Truth Machines by Paul Vigna and Michael J. Casey — Ch. 8: “The Oracle Problem” |

Essential Reading Order

For maximum comprehension, read in this order:

- Cryptographic Foundations (Week 1-2):

- Serious Cryptography Ch. 6 (hash functions) and Ch. 10 (signatures)

- Mastering Bitcoin Ch. 4 (keys and addresses)

- Implement SHA-256 from scratch (Project 1)

- Blockchain Structure (Week 3):

- Mastering Bitcoin Ch. 9-10 (blockchain and mining)

- Blockchain Basics Ch. 7-9 (consensus)

- Build a simple blockchain (Project 2)

- Smart Contracts & EVM (Week 4-5):

- Mastering Ethereum Ch. 7 (Solidity) and Ch. 13 (EVM)

- Mastering Ethereum Ch. 9 (security)

- Implement EVM interpreter (Project 4)

- DeFi & Economics (Week 6+):

- How to DeFi: Advanced Ch. 2-3 (DEXs and lending)

- Token Economy Ch. 4 (incentive design)

- Build DeFi primitives (Projects 6-7)

Quick Start: Your First 48 Hours

Feeling overwhelmed by 18 projects? Start here. This is the absolute minimum path to get hands-on quickly and build momentum.

Day 1: Understanding What Makes Web3 Tick (4-5 hours)

Morning (2-3 hours): Hash Functions Are Everything

- Read (30 min):

- Serious Cryptography Ch. 6, pages 105-125 (hash function properties)

- NIST FIPS 180-4 SHA-256 specification (skim the algorithm overview)

- Experiment (30 min):

- Use an online SHA-256 calculator (like sha256algorithm.com)

- Hash “Hello World” → note the output

- Change ONE letter (“hello World”) → see avalanche effect

- Try to find two inputs with the same hash (spoiler: you can’t)

- Build (1-2 hours):

- Start Project 1’s message padding function

- Don’t worry about the full SHA-256 yet—just get input formatted correctly

- Goal: Take any string, convert to binary, add padding bits

Afternoon (2 hours): Why Blockchains Are Chains

- Visualization:

- Go to blockchain.com/explorer or etherscan.io

- Click on any Bitcoin or Ethereum block

- Notice: previous block hash, current block hash, list of transactions

- Ask yourself: “What happens if I change one transaction?”

- Minimal blockchain (90 min):

- Create a

Blockstruct with: data, previous_hash, hash - Write a function:

calculate_hash(block) -> hash - Create 3 blocks linked by hashes

- Try changing block #2’s data → all subsequent hashes break

- Create a

End of Day 1 Result: You now understand the two core insights:

- Hashes are one-way fingerprints (can’t be reversed or predicted)

- Chains of hashes make history tamper-evident (changing the past is visible)

Day 2: From Blockchain to Smart Contracts (4-5 hours)

Morning (2 hours): Proof of Work Intuition

- Concept (30 min):

- Read Mastering Bitcoin Ch. 10, pages 201-215 (mining overview)

- Understand: mining = finding hash < target value

- Build (90 min):

- Add a

noncefield to your Block struct - Write:

mine_block(difficulty) -> nonce - Goal: find nonce where hash starts with N zeros

- Try difficulty=1 (easy), then difficulty=4 (harder)

- Notice: time increases exponentially

- Add a

Afternoon (2-3 hours): Smart Contracts Are Code That Can’t Lie

- Read (30 min):

- Mastering Ethereum Ch. 7, pages 131-145 (what are smart contracts?)

- Understand: code runs identically on every node

- Experiment with existing contracts (60 min):

- Go to etherscan.io and view a verified ERC-20 token contract

- Read the

transfer()function in the code tab - See the state changes in transaction logs

- Notice: this code is law—no one can change it after deployment

- Conceptual design (60 min):

- Design (on paper) a simple “voting contract”

- What state does it need? (candidates, vote counts, voter addresses)

- What functions? (vote, getWinner, hasVoted)

- What could go wrong? (double voting, unauthorized voting)

End of Day 2 Result: You understand:

- Mining makes changing history computationally expensive

- Smart contracts are unstoppable code that everyone can verify

- Security is HARD because bugs are permanent

What to Do Next

After these 48 hours, you have three paths:

Path A: Cryptography-First (recommended for security-minded) → Complete Projects 1, 2, 3 (hash, signatures, Merkle trees) → Then Project 4 (full blockchain) → Understand the math before the applications

Path B: Blockchain-First (recommended for systems thinkers) → Complete Project 4 (blockchain from scratch) → Add Project 5 (proof of work) → Then backfill cryptography (Projects 1-3) → See the whole system first, then understand the parts

Path C: Smart Contracts-First (recommended for developers) → Complete Project 8 (simple EVM) → Then Project 9 (ERC-20 token) → Understand the application layer first → Backfill blockchain fundamentals later

No matter which path: You now have context for why these projects matter. The rest is building depth.

Recommended Learning Paths

Everyone learns differently. Choose the path that matches your background and goals.

Path 1: The Cryptographer’s Journey (Bottom-Up)

Best for: Security researchers, mathematically-inclined, or those who want bulletproof fundamentals

Order: Projects 1 → 2 → 3 → 4 → 5 → 14 → 6 → 7 → 8 → 9 → 10 → 16 → 17 → 13 → 11 → 12 → 15 → 18

Philosophy: Master the cryptographic primitives first, then build the systems that use them.

Milestones:

- Week 2: You’ve implemented SHA-256 by hand (Project 1)

- Week 4: You understand why digital signatures are unforgeable (Project 2)

- Week 6: You’ve built a blockchain from scratch (Project 4)

- Week 12: You can audit smart contracts for vulnerabilities (Project 14)

- Month 4-6: You understand Layer 2 scaling and can build production systems

Why this works: Every higher-level concept makes sense because you built the foundation yourself.

Path 2: The Systems Engineer’s Journey (Top-Down)

Best for: Infrastructure engineers, distributed systems background, or impatient learners

Order: Projects 4 → 5 → 8 → 9 → 10 → 1 → 2 → 3 → 6 → 7 → 16 → 14 → 13 → 11 → 12 → 17 → 15 → 18

Philosophy: See the whole system working first, then understand how the pieces work.

Milestones:

- Week 3: You’ve built a working blockchain (Project 4)

- Week 5: You understand mining and consensus (Project 5)

- Week 8: You can execute Ethereum smart contracts (Project 8)

- Week 12: You’ve built a DEX and understand DeFi (Project 10)

- Month 4-6: You backfilled cryptography and can explain security guarantees

Why this works: Motivation stays high because you see practical results immediately. You learn “why” through curiosity rather than upfront theory.

Path 3: The Application Developer’s Journey (Use-Case Driven)

Best for: Web developers, entrepreneurs, or those focused on building products

Order: Projects 9 → 10 → 11 → 12 → 8 → 16 → 17 → 4 → 5 → 14 → 1 → 2 → 3 → 6 → 7 → 13 → 15 → 18

Philosophy: Start with what users interact with, then dig deeper into how it works.

Milestones:

- Week 2: You’ve deployed an ERC-20 token (Project 9)

- Week 4: You’ve built a DEX interface (Project 10)

- Week 6: You’ve created an NFT marketplace (Project 11)

- Week 10: You understand EVM internals and can optimize gas (Project 8)

- Month 4-6: You understand the full stack from UI to cryptographic primitives

Why this works: You can show tangible projects to employers/users immediately, then deepen understanding through necessity.

Path 4: The Security Researcher’s Journey (Attack-Minded)

Best for: Penetration testers, bug bounty hunters, or those who think like attackers

Order: Projects 14 → 9 → 10 → 16 → 17 → 11 → 1 → 2 → 3 → 4 → 5 → 8 → 6 → 7 → 13 → 12 → 15 → 18

Philosophy: Learn to break things first, then understand why they’re vulnerable.

Milestones:

- Week 2: You’ve built a reentrancy scanner (Project 14)

- Week 4: You’ve exploited common ERC-20 bugs (Project 9 + testing)

- Week 6: You understand flash loan attacks (Project 17)

- Week 10: You can audit smart contracts professionally

- Month 4-6: You understand Layer 2 security models and novel attack surfaces

Why this works: Security mindset is built through hands-on exploitation, not just reading about vulnerabilities.

How to Choose Your Path

Ask yourself:

- “Do I learn better by building the foundation first, or seeing the final product?”

- Foundation-first → Path 1 or 4

- Product-first → Path 2 or 3

- “Am I more interested in how it works, or what I can build with it?”

- How it works → Path 1 or 2

- What I can build → Path 3 or 4

- “Do I have a strong math/cryptography background?”

- Yes → Path 1

- No → Path 2 or 3

- “What’s my career goal?”

- Blockchain protocol developer → Path 1 or 2

- DApp developer → Path 3

- Security auditor → Path 4

Important: These paths are suggestions, not rules. Feel free to mix-and-match or create your own order. The projects are designed to be mostly independent.

Project 1: Cryptographic Hash Function Visualizer

- File: WEB3_DEEP_UNDERSTANDING_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: Rust

- Alternative Programming Languages: C, Go, Python

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold” (Educational/Personal Brand)

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Cryptography / Hash Functions

- Software or Tool: SHA-256 Implementation

- Main Book: “Serious Cryptography, 2nd Edition” by Jean-Philippe Aumasson

What you’ll build

A command-line tool that implements SHA-256 from scratch (no crypto libraries), visualizing each step: message padding, block processing, compression function rounds, and the avalanche effect.

Why it teaches Web3

Hash functions are the foundation of everything in Web3. Block hashes, transaction IDs, Merkle trees, proof-of-work mining—all depend on understanding that hash functions are one-way, deterministic, and avalanche-sensitive. Without implementing one yourself, you’re just trusting magic.

Core challenges you’ll face

- Bit manipulation (rotating, shifting, XORing 32-bit words) → maps to low-level cryptography

- Message padding (handling arbitrary-length input) → maps to protocol specifications

- Compression function (64 rounds of mixing) → maps to understanding irreversibility

- Avalanche visualization (showing how 1-bit change affects output) → maps to security intuition

Key Concepts

- Hash Function Properties: “Serious Cryptography” Chapter 6 - Jean-Philippe Aumasson

- Bit Manipulation in C: “The C Programming Language” Chapter 2 - Kernighan & Ritchie

- SHA-256 Specification: NIST FIPS 180-4

Difficulty

Intermediate

Time estimate

1-2 weeks

Prerequisites

Basic programming, understanding of binary/hex

Real world outcome

$ ./sha256_visualizer "Hello"

Input: "Hello" (5 bytes)

Padded: 48656c6c6f80000000...0028 (64 bytes)

Round 0: A=5d6aeb04 B=6a09e667 C=bb67ae85 ...

Round 1: A=2a0c8e42 B=5d6aeb04 C=6a09e667 ...

...

Round 63: A=185f8db3 B=2271fe25 C=f14f0564 ...

Final Hash: 185f8db32271fe25f561a6fc938b2e264306ec304eda518007d1764826381969

Avalanche Test:

"Hello" → 185f8db32271fe25...

"hello" → 2cf24dba5fb0a30e...

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ (32/64 bytes different = 50%)

Implementation Hints

Start by reading FIPS 180-4 specification (it’s surprisingly readable). Implement the message schedule (W array) first, then the compression function. Use uint32_t for words. The key insight: each round mixes bits so thoroughly that reversing even one round is computationally infeasible. For visualization, print intermediate values in hex with color coding (green = bits that changed).

Pseudo-code structure:

function sha256(message):

padded = pad_message(message)

blocks = split_into_512bit_blocks(padded)

H = initial_hash_values // These are specific constants

for each block:

W = expand_to_64_words(block)

a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h = H

for round in 0..63:

// Apply mixing functions

T1 = h + Σ1(e) + Ch(e,f,g) + K[round] + W[round]

T2 = Σ0(a) + Maj(a,b,c)

// Shift and update

H = H + (a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h)

return concatenate(H)

Learning milestones

- Message padding works correctly → You understand protocol specifications

- Single block hashes match known values → You’ve implemented cryptographic primitives

- Avalanche visualization shows ~50% bit changes → You understand security properties

The Core Question You’re Answering

“Why can’t you reverse a hash? What makes SHA-256 ‘one-way’ at the mathematical level?”

This is the foundational question of all cryptography in Web3. Everyone says hash functions are “one-way,” but WHY? It’s not because we haven’t found the reverse algorithm—it’s because the mathematical operations destroy information in a way that’s fundamentally irreversible. Each of the 64 rounds in SHA-256 mixes bits using XOR, rotation, and modular addition in combinations that create avalanche effects. Reversing even ONE round requires solving systems of equations with more unknowns than equations—mathematically impossible.

When you implement SHA-256, you’ll see exactly how 5 bytes of input (“Hello”) becomes 32 bytes of output that changes completely if you flip a single bit. This isn’t magic—it’s deliberate mathematical chaos.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Binary and Hexadecimal Representation

- How do you convert between binary, hex, and decimal?

- What is a byte vs a bit vs a word (32 bits)?

- Why does cryptography use hex instead of decimal?

- Book Reference: “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” Ch. 2 (sections 2.1-2.2) - Bryant & O’Hallaron

- Bitwise Operations

- What do XOR, AND, OR, NOT operations do at the bit level?

- What is bit rotation vs bit shifting?

- Why is XOR reversible but hash functions aren’t?

- Book Reference: “The C Programming Language” Ch. 2.9 - Kernighan & Ritchie

- Book Reference: “Serious Cryptography” Ch. 6 - Jean-Philippe Aumasson

- Hash Function Properties

- What are the three critical properties: preimage resistance, second-preimage resistance, collision resistance?

- What is the avalanche effect and why does it matter?

- What’s the difference between SHA-256 and SHA-3 (Keccak)?

- Book Reference: “Serious Cryptography” Ch. 6 - Jean-Philippe Aumasson

- Web Resource: Understanding Hash Functions in Web3

- Message Padding Standards

- Why do we pad messages to 512-bit boundaries?

- How does the length encoding prevent length-extension attacks?

- What happens if you hash an empty string?

- Book Reference: NIST FIPS 180-4 specification (sections 5.1-5.2)

- Modular Arithmetic

- What does

(a + b) mod 2^32mean? - Why do we use 32-bit words instead of 64-bit or 16-bit?

- How does overflow work in fixed-width integer arithmetic?

- Book Reference: “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” Ch. 2.3 - Bryant & O’Hallaron

- What does

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Data Representation

- How will you represent a 32-bit word in your programming language?

- Should you use big-endian or little-endian byte order? (SHA-256 uses big-endian)

- How do you convert a string like “Hello” into an array of bytes?

- Message Padding Algorithm

- Given an input of arbitrary length, how do you calculate the padding length?

- Where does the ‘1’ bit go? Where does the length encoding go?

- How do you handle messages that are already close to 512-bit boundaries?

- Round Function Design

- The compression function has 64 rounds. Should you unroll the loop or use iteration?

- How do you implement the Σ (Sigma) and Ch/Maj functions?

- Where do the K constants come from? (Hint: cube roots of primes)

- Visualization Strategy

- How do you show the state of all 8 working variables (a-h) at each round?

- How do you highlight which bits changed between inputs?

- Should you use color coding, diff symbols, or both?

- Testing and Validation

- What are the official test vectors for SHA-256?

- How do you verify your implementation against known values?

- How do you measure the avalanche effect numerically?

Thinking Exercise

Trace SHA-256 by Hand (First 2 Rounds)

Before coding, work through this on paper to build intuition:

Given input: “A” (single character, ASCII 0x41)

Step 1: Padding

Original: 01000001 (1 byte)

Append '1': 01000001 1 0000000... (add single '1' bit)

Append zeros: Fill to 448 bits

Append length: ...00001000 (8 bits in binary, goes in last 64 bits)

Total: 512 bits (one block)

Step 2: Initialize working variables

H0 = 0x6a09e667 (first 32 bits of sqrt(2))

H1 = 0xbb67ae85 (first 32 bits of sqrt(3))

... (8 total initial values)

Step 3: Compute first two rounds

Round 0:

W[0] = first 32 bits of padded message

T1 = h + Σ1(e) + Ch(e,f,g) + K[0] + W[0]

T2 = Σ0(a) + Maj(a,b,c)

New h = g, g = f, f = e, e = d + T1, ...

Round 1:

W[1] = next 32 bits

(repeat calculation)

Questions while tracing:

- Can you identify which bits in T1 came from which source?

- If you change one bit in the input, which working variables change in round 0?

- By round 2, have all 8 variables been affected by the input?

Tip: Use a spreadsheet to track the hex values. It’s tedious but incredibly educational.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these after completing the project:

Fundamental Understanding:

- “Explain how SHA-256 achieves the avalanche effect.”

- “Why is SHA-256 considered ‘collision-resistant’ if the output space is finite?”

- “What’s the difference between SHA-256 and HMAC-SHA256?”

- “How does Bitcoin use SHA-256 twice (double-SHA256)? Why?”

Implementation Details:

- “How many rounds does SHA-256 have and why that number?”

- “What are the K constants in SHA-256 and where do they come from?”

- “Explain the message schedule array (W) and why it expands to 64 words.”

- “What happens if you don’t pad the message correctly?”

Security Concepts:

- “What’s a length-extension attack and how does SHA-256’s padding prevent it?”

- “If SHA-256 outputs 256 bits, why can’t you find collisions by testing 2^128 inputs?”

- “How would you verify a file’s integrity using SHA-256?”

- “What’s the relationship between hash functions and proof-of-work?”

Web3 Applications:

- “How do Merkle trees use hash functions to enable light clients?”

- “Why does Ethereum use Keccak-256 instead of SHA-256?”

- “Explain how Bitcoin’s block hash is calculated.”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with the constants The initial hash values (H0-H7) and round constants (K[0]-K[63]) are defined in the FIPS 180-4 spec. Hard-code these first:

const INITIAL_H: [u32; 8] = [

0x6a09e667, 0xbb67ae85, 0x3c6ef372, 0xa54ff53a,

0x510e527f, 0x9b05688c, 0x1f83d9ab, 0x5be0cd19,

];

const K: [u32; 64] = [

0x428a2f98, 0x71374491, 0xb5c0fbcf, 0xe9b5dba5,

// ... 60 more values (cube roots of first 64 primes)

];

Hint 2: Implement padding carefully

def pad_message(msg_bytes):

msg_len = len(msg_bytes)

msg_bits = msg_len * 8

# Append '1' bit (0x80 byte)

msg_bytes += b'\x80'

# Append zeros until length ≡ 448 mod 512

while (len(msg_bytes) * 8) % 512 != 448:

msg_bytes += b'\x00'

# Append original length as 64-bit big-endian

msg_bytes += msg_bits.to_bytes(8, 'big')

return msg_bytes

Hint 3: The round function building blocks

// Right rotate

#define ROTR(x, n) (((x) >> (n)) | ((x) << (32 - (n))))

// SHA-256 functions

#define CH(x, y, z) (((x) & (y)) ^ (~(x) & (z)))

#define MAJ(x, y, z) (((x) & (y)) ^ ((x) & (z)) ^ ((y) & (z)))

#define SIGMA0(x) (ROTR(x, 2) ^ ROTR(x, 13) ^ ROTR(x, 22))

#define SIGMA1(x) (ROTR(x, 6) ^ ROTR(x, 11) ^ ROTR(x, 25))

#define sigma0(x) (ROTR(x, 7) ^ ROTR(x, 18) ^ ((x) >> 3))

#define sigma1(x) (ROTR(x, 17) ^ ROTR(x, 19) ^ ((x) >> 10))

Hint 4: Visualizing the avalanche effect Hash two similar strings and compare bit-by-bit:

hash1 = sha256("Hello")

hash2 = sha256("hello") # Only case changed

different_bits = bin(int(hash1, 16) ^ int(hash2, 16)).count('1')

print(f"Different bits: {different_bits}/256 = {different_bits/256*100:.1f}%")

# Should be close to 50%

Hint 5: Test vectors for validation

Input: "" (empty string)

SHA-256: e3b0c44298fc1c149afbf4c8996fb92427ae41e4649b934ca495991b7852b855

Input: "abc"

SHA-256: ba7816bf8f01cfea414140de5dae2223b00361a396177a9cb410ff61f20015ad

Input: "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog"

SHA-256: d7a8fbb307d7809469ca9abcb0082e4f8d5651e46d3cdb762d02d0bf37c9e592

Your implementation must match these exactly.

Hint 6: Debugging strategy Print intermediate values at each round and compare with a working implementation:

Round 0: a=5d6aeb04 b=6a09e667 c=bb67ae85 d=3c6ef372

e=f46a2f5b f=510e527f g=9b05688c h=1f83d9ab

Use an existing implementation with verbose output as a reference.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Hash function fundamentals | “Serious Cryptography, 2nd Edition” by Jean-Philippe Aumasson | Chapter 6: Hash Functions |

| Cryptographic properties | “Serious Cryptography, 2nd Edition” by Jean-Philippe Aumasson | Chapter 7: Keyed Hashing |

| Binary representation | “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” by Bryant & O’Hallaron | Chapter 2.1-2.3: Information Representation |

| Bitwise operations in C | “The C Programming Language” by Kernighan & Ritchie | Chapter 2.9: Bitwise Operators |

| SHA-256 in Bitcoin | “Mastering Bitcoin” by Andreas M. Antonopoulos | Chapter 4: Keys, Addresses |

| Avalanche effect demonstration | “Understanding Cryptography” by Christof Paar | Chapter 11: Hash Functions |

| Web3 hash function usage | “Mastering Ethereum” by Antonopoulos & Wood | Chapter 4: Cryptography |

| Applied cryptography context | “Real-World Cryptography” by David Wong | Chapter 2: Hash Functions |

Recommended Reading Order:

- Start with “Serious Cryptography” Ch. 6 to understand WHY hash functions have these properties

- Read FIPS 180-4 specification (surprisingly accessible, ~30 pages)

- Study “Computer Systems” Ch. 2 for bit manipulation details

- Implement while referring to evm.codes and Bitcoin documentation for real-world context

Additional Resources:

- SHA-256 Cryptographic Hash Algorithm in JavaScript - detailed annotated implementation

- Understanding Hash Functions in Web3 - modern 2025 guide

- Hash Functions in Web3 (SHA-256, Keccak-256, Merkle Trees) - comprehensive overview

Project 2: ECDSA Digital Signature Implementation

- File: WEB3_DEEP_UNDERSTANDING_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: Rust

- Alternative Programming Languages: Python, Go, C

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold” (Educational/Personal Brand)

- Difficulty: Level 4: Expert

- Knowledge Area: Cryptography / Elliptic Curves

- Software or Tool: secp256k1 Signature Tool

- Main Book: “Elliptic Curve Cryptography for Developers” by Michael Rosing

What you’ll build

A complete ECDSA implementation using the secp256k1 curve (same as Bitcoin/Ethereum). Generate key pairs, sign messages, and verify signatures—all from scratch without crypto libraries.

Why it teaches Web3

Every transaction in Bitcoin and Ethereum is authorized via ECDSA. When you send crypto, you’re creating a signature that mathematically proves you own the private key. Understanding this means understanding ownership in Web3—not “someone says you own it,” but “math proves you own it.”

Core challenges you’ll face

- Modular arithmetic (operations in finite fields) → maps to mathematical foundations

- Point addition on curves (geometric operations become algebra) → maps to elliptic curve math

- Random number generation (k value must be truly random) → maps to critical security

- Signature malleability (understanding s-value normalization) → maps to protocol subtleties

Key Concepts

- Elliptic Curve Math: “Elliptic Curve Cryptography for Developers” Chapters 2-4 - Michael Rosing

- secp256k1 Parameters: Bitcoin Wiki ECDSA

- Practical Implementation: “Practical Cryptography for Developers” - cryptobook.nakov.com

- Security Considerations: “Serious Cryptography” Chapter 11 - Jean-Philippe Aumasson

Difficulty

Expert (requires comfort with modular arithmetic)

Time estimate

3-4 weeks

Prerequisites

Project 1 (hash functions), basic number theory, comfort with mathematical notation

Real world outcome

$ ./ecdsa generate

Private Key: 0x1a2b3c4d5e6f...

Public Key: 04:7b3f2a...

$ ./ecdsa sign --key private.key --message "Send 1 ETH to Alice"

Message Hash: 0x9f86d081884c...

Signature (r,s): (0x3045..., 0x3046...)

$ ./ecdsa verify --pubkey public.key --message "Send 1 ETH to Alice" --sig signature.bin

✓ Signature VALID - This message was signed by this key

$ ./ecdsa verify --pubkey public.key --message "Send 100 ETH to Eve" --sig signature.bin

✗ Signature INVALID - Message or signer mismatch

Implementation Hints

Start with finite field arithmetic: implement mod_add, mod_sub, mod_mul, mod_inv (use extended Euclidean algorithm for inverse). Then implement point operations: point_add, point_double, scalar_mult. The secp256k1 curve is y² = x³ + 7 over a prime field.

Critical security note: The random k value in signing MUST be cryptographically random. Reusing k or using predictable k leaks your private key (this is how the PlayStation 3 was hacked).

Pseudo-code for signing:

function sign(private_key, message_hash):

k = random_in_range(1, n-1) // n = curve order

R = k * G // G = generator point

r = R.x mod n

s = k_inv * (message_hash + r * private_key) mod n

return (r, s)

function verify(public_key, message_hash, r, s):

s_inv = modular_inverse(s, n)

u1 = message_hash * s_inv mod n

u2 = r * s_inv mod n

R = u1*G + u2*public_key

return r == R.x mod n

Learning milestones

- Modular inverse works correctly → You understand finite field arithmetic

- Point multiplication matches test vectors → You’ve implemented elliptic curve operations

- Sign/verify round-trips correctly → You understand digital signatures

- Your signatures validate in real Bitcoin/Ethereum libraries → You’ve achieved compatibility

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How can you prove you own something without revealing the secret that grants ownership?”

This is the paradox at the heart of Web3. Your private key IS your money—but you can’t show it to anyone or they can steal everything. Digital signatures solve this through elliptic curve mathematics: you can create a signature using your private key that anyone can verify using your public key, but the signature doesn’t leak information about the private key itself.

The deeper question: WHY is this mathematically impossible to reverse? It’s because multiplying a point on an elliptic curve by a scalar (k * G) is computationally easy, but given the result, finding k (the discrete logarithm problem) is computationally infeasible. This asymmetry—easy one way, impossible the other—is the foundation of all public-key cryptography in Web3.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Modular Arithmetic and Finite Fields

- What does (a + b) mod p mean and why does it form a field?

- How do you compute modular inverses? (Extended Euclidean Algorithm)

- What’s the difference between a field and a ring?

- Why do we use prime fields (GF(p)) for elliptic curves?

- Book Reference: “Concrete Mathematics” Ch. 4 - Knuth, Graham & Patashnik

- Book Reference: “Serious Cryptography” Ch. 11 (sections on modular arithmetic) - Jean-Philippe Aumasson

- Elliptic Curve Geometry

- What is the equation y² = x³ + ax + b and why this specific form?

- What does “point addition” mean geometrically? (Draw it!)

- Why is the identity element the “point at infinity”?

- How does point doubling differ from point addition?

- Book Reference: “Understanding Cryptography” Ch. 9 - Christof Paar

- Web Resource: Elliptic Curve Cryptography for Developers

- The secp256k1 Curve Parameters

- p = 2^256 - 2^32 - 977 (the prime field)

- a = 0, b = 7 (so y² = x³ + 7)

- G = generator point (04 79BE667E…)

- n = order of G (number of points in subgroup)

- Why these specific values? (Bitcoin chose secp256k1 for speed)

- Web Resource: Bitcoin Wiki - Secp256k1

- Book Reference: “Mastering Bitcoin” Ch. 4 - Andreas M. Antonopoulos

- Digital Signature Mechanics

- What makes a signature “unforgeable”?

- Why do we sign the hash of a message, not the message itself?

- What is signature malleability and why does it matter?

- How does the verification equation work: u1G + u2PubKey = R?

- Book Reference: “Serious Cryptography” Ch. 11 - Jean-Philippe Aumasson

- Book Reference: “Real-World Cryptography” Ch. 7 - David Wong

- Cryptographically Secure Random Numbers

- Why can’t you use

rand()for the k value? - What happened with the PlayStation 3 hack? (They used constant k!)

- How do you get entropy from the OS? (/dev/urandom, getrandom())

- What is the “k-reuse attack” and how does it leak private keys?

- Book Reference: “Serious Cryptography” Ch. 3 - Jean-Philippe Aumasson

- Why can’t you use

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Finite Field Implementation

- How will you represent 256-bit integers in your language?

- Do you have native big-integer support or need to implement it?

- How do you ensure operations don’t overflow?

- What’s the most efficient algorithm for modular inverse?

- Elliptic Curve Point Representation

- Should you use affine coordinates (x, y) or projective coordinates?

- How do you represent the point at infinity?

- Compressed vs uncompressed public keys—what’s the difference?

- How do you validate that a point lies on the curve?

- Scalar Multiplication Optimization

- Given k and G, how do you compute k*G efficiently?

- What is the “double-and-add” algorithm?

- Can you use pre-computed tables for the generator point G?

- What’s the computational complexity? (Hint: O(log k))

- Signature Format

- How do you serialize (r, s) values? (DER encoding in Bitcoin)

- What’s the difference between low-s and high-s signatures?

- Why does Ethereum require “v” in addition to (r, s)?

- How do you handle signature malleability?

- Security Validation

- How do you test that k reuse leaks the private key?

- What are the test vectors for secp256k1?

- How do you verify your implementation against real Bitcoin/Ethereum transactions?

Thinking Exercise

Trace ECDSA Signing By Hand (Simplified)

Use small numbers to understand the algorithm before implementing with 256-bit values:

Setup (toy example):

Prime field: p = 23

Curve: y² = x³ + 7 (mod 23)

Generator G = (5, 8) [verify: 8² = 5³ + 7 = 132 ≡ 17 (mod 23), 17 ≡ -6, so 8² ≡ 5³ + 7]

Order n = 29 (number of points)

Private key: d = 6

Public key: Q = d*G = 6*G

Exercise 1: Compute Public Key

1*G = (5, 8)

2*G = G + G = ? [use point doubling formula]

3*G = 2*G + G = ?

...

6*G = ?

Exercise 2: Sign message hash m = 10

Choose random k = 18 (in reality, must be cryptographically random)

1. R = k*G = 18*G = (?,?) [compute this]

2. r = R.x mod n

3. s = k⁻¹ * (m + r*d) mod n

- First find k⁻¹ mod 29 using extended Euclidean algorithm

- Then compute s

Signature = (r, s)

Exercise 3: Verify the signature

Given: Public key Q, message hash m=10, signature (r,s)

1. Compute s⁻¹ mod n

2. u1 = m * s⁻¹ mod n

3. u2 = r * s⁻¹ mod n

4. R' = u1*G + u2*Q

5. Verify: R'.x mod n == r

Questions while tracing:

- Can you derive the private key from the public key? Try it!

- If you know k, can you recover the private key d from the signature?

- What happens if you use k=1? Is the signature still valid?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these after completing the project:

Fundamental Understanding:

- “Explain how elliptic curve point addition works geometrically and algebraically.”

- “Why is ECDSA more efficient than RSA for the same security level?”

- “What is the discrete logarithm problem and why is it hard?”

- “How does ECDSA provide non-repudiation?”

Implementation Details:

- “What’s the difference between secp256k1 and secp256r1?”

- “How do you compute a modular inverse efficiently?”

- “What’s the difference between hardened and normal key derivation?” (BIP-32)

- “Explain the double-and-add algorithm for scalar multiplication.”

Security Concepts:

- “What happens if you reuse the same k value for two different messages?”

- “Why must k be cryptographically random, not just pseudo-random?”

- “What is signature malleability and how did it affect Bitcoin?”

- “How did the PlayStation 3 get hacked due to ECDSA implementation?”

Web3 Applications:

- “How does Ethereum recover the public key from a signature? (ecrecover)”

- “What’s the relationship between private keys, public keys, and Ethereum addresses?”

- “Why do Bitcoin transactions include the public key, while Ethereum doesn’t?”

- “Explain how hardware wallets sign transactions without exposing private keys.”

Advanced Topics:

- “What are Schnorr signatures and how do they differ from ECDSA?”

- “How do multi-signature schemes work on elliptic curves?”

- “What is the security level of secp256k1 in bits?”

- “Can quantum computers break ECDSA? How?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with the curve parameters

// secp256k1 parameters (256-bit)

const P: U256 = U256::from_be_hex(

"FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFEFFFFFC2F"

);

const N: U256 = U256::from_be_hex(

"FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFEBAAEDCE6AF48A03BBFD25E8CD0364141"

);

const G_X: U256 = U256::from_be_hex(

"79BE667EF9DCBBAC55A06295CE870B07029BFCDB2DCE28D959F2815B16F81798"

);

const G_Y: U256 = U256::from_be_hex(

"483ADA7726A3C4655DA4FBFC0E1108A8FD17B448A68554199C47D08FFB10D4B8"

);

Hint 2: Implement modular inverse using Extended Euclidean Algorithm

def mod_inverse(a, m):

"""Compute a⁻¹ mod m using Extended Euclidean Algorithm"""

if gcd(a, m) != 1:

return None # inverse doesn't exist

def extended_gcd(a, b):

if a == 0:

return b, 0, 1

gcd, x1, y1 = extended_gcd(b % a, a)

x = y1 - (b // a) * x1

y = x1

return gcd, x, y

_, x, _ = extended_gcd(a % m, m)

return (x % m + m) % m

Hint 3: Point addition formulas

If P = (x1, y1) and Q = (x2, y2):

Case 1: P ≠ Q (point addition)

λ = (y2 - y1) / (x2 - x1) mod p

x3 = λ² - x1 - x2 mod p

y3 = λ(x1 - x3) - y1 mod p

Case 2: P = Q (point doubling)

λ = (3*x1² + a) / (2*y1) mod p

x3 = λ² - 2*x1 mod p

y3 = λ(x1 - x3) - y1 mod p

For secp256k1, a = 0, so λ = (3*x1²) / (2*y1) mod p

Hint 4: Scalar multiplication (double-and-add)

def scalar_mult(k, point):

"""Compute k * point using double-and-add"""

result = POINT_AT_INFINITY

addend = point

while k:

if k & 1: # if bit is 1

result = point_add(result, addend)

addend = point_double(addend)

k >>= 1

return result

Hint 5: The k-reuse attack demonstration

# If you sign two messages m1, m2 with same k:

# s1 = k⁻¹(m1 + r*d) mod n

# s2 = k⁻¹(m2 + r*d) mod n

# Attacker can compute k:

k = (m1 - m2) * (s1 - s2)⁻¹ mod n

# Then recover private key d:

d = r⁻¹ * (k*s1 - m1) mod n

# This is EXACTLY how the PS3 was hacked!

Hint 6: Test vectors for validation

Private key: 0x01

Public key (uncompressed):

04 79BE667EF9DCBBAC55A06295CE870B07029BFCDB2DCE28D959F2815B16F81798

483ADA7726A3C4655DA4FBFC0E1108A8FD17B448A68554199C47D08FFB10D4B8

Message hash: 0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001

Signature (one possible):

r = 0x...

s = 0x...

(deterministic k produces consistent signature)

Use Bitcoin’s test vectors from the secp256k1 library.

Hint 7: Implementing signature verification The verification equation is: u1G + u2Q = R

Why does this work? Because:

u1*G + u2*Q

= (m*s⁻¹)*G + (r*s⁻¹)*Q

= (m*s⁻¹)*G + (r*s⁻¹)*(d*G)

= (m*s⁻¹ + r*d*s⁻¹)*G

= s⁻¹(m + r*d)*G

= s⁻¹(k*s)*G [because s = k⁻¹(m + r*d)]

= k*G

= R

The math is beautiful—trace through it!

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Elliptic curve fundamentals | “Understanding Cryptography” by Christof Paar | Chapter 9: Elliptic Curve Cryptosystems |

| ECDSA algorithm | “Serious Cryptography, 2nd Edition” by Jean-Philippe Aumasson | Chapter 11: Public-Key Encryption |

| Modular arithmetic | “Concrete Mathematics” by Knuth, Graham & Patashnik | Chapter 4: Number Theory |

| Finite field mathematics | “A Course in Number Theory and Cryptography” by Neal Koblitz | Chapters 5-6 |

| secp256k1 in Bitcoin | “Mastering Bitcoin” by Andreas M. Antonopoulos | Chapter 4: Keys, Addresses |

| Real-world implementation | “Real-World Cryptography” by David Wong | Chapter 7: Signatures and Zero-Knowledge |

| Security pitfalls | “Serious Cryptography” by Jean-Philippe Aumasson | Chapter 3: Randomness |

| Applied elliptic curves | “Guide to Elliptic Curve Cryptography” by Hankerson, Menezes & Vanstone | Chapters 3-4 |

Recommended Reading Order:

- Start with “Understanding Cryptography” Ch. 9 for geometric intuition

- Study “Serious Cryptography” Ch. 11 for the ECDSA algorithm

- Read Bitcoin Wiki secp256k1 page for parameter details

- Implement while referring to Practical Cryptography for Developers

- Deep dive into “Concrete Mathematics” Ch. 4 if modular arithmetic is unclear

Additional Resources:

- Secp256k1 Educational Resource - interactive 2025 tutorial

- ECDSA: Elliptic Curve Signatures - comprehensive guide

- Bitcoin Wiki ECDSA - implementation details

- A (Relatively Easy To Understand) Primer on Elliptic Curve Cryptography - visual explanation

Academic Papers:

- “The Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA)” by Don Johnson, Alfred Menezes, Scott Vanstone (1999)

- Bitcoin’s BIP-66: “Strict DER signatures” for signature encoding details

Project 3: Merkle Tree Library

- File: WEB3_DEEP_UNDERSTANDING_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: Go

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, C, TypeScript

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 3. The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Data Structures / Blockchain

- Software or Tool: Merkle Tree / Proof Generator

- Main Book: “Mastering Bitcoin” by Andreas M. Antonopoulos

What you’ll build

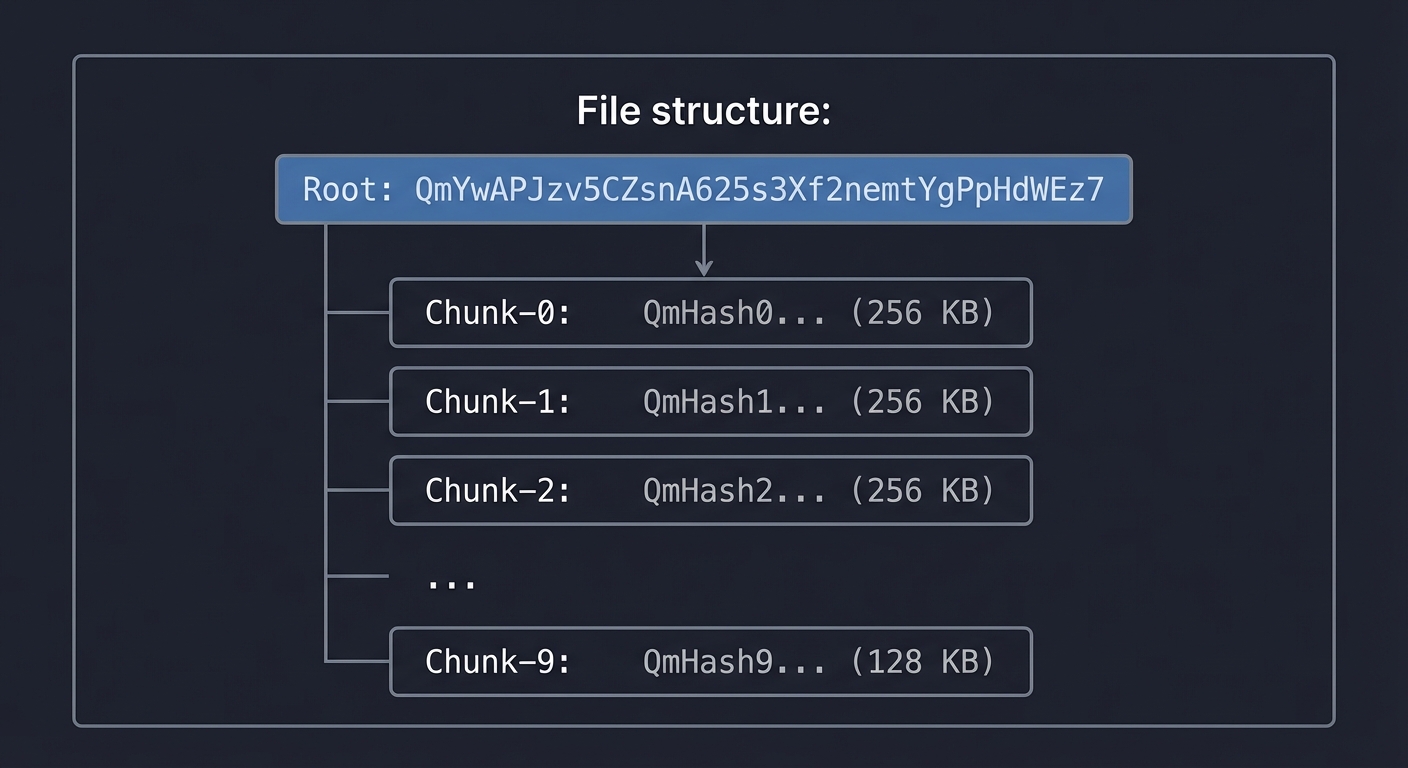

A Merkle tree library that constructs trees from data, generates inclusion proofs, and verifies proofs. Visualize tree structure and demonstrate how changing one leaf affects the root.

Why it teaches Web3

Merkle trees enable light clients—you can verify a transaction is in a block by downloading only ~10 hashes instead of millions of transactions. This is how mobile wallets work. Understanding Merkle proofs means understanding how trustless verification is even possible.

Core challenges you’ll face

- Tree construction (handling odd number of leaves, recursive hashing) → maps to data structure design

- Proof generation (collecting sibling hashes along the path) → maps to algorithmic thinking

- Proof verification (reconstructing root from leaf + proof) → maps to verification logic

- Sparse Merkle trees (efficient representation of mostly-empty trees) → maps to Ethereum state

Key Concepts

- Merkle Trees in Bitcoin: “Mastering Bitcoin” Chapter 9 - Andreas Antonopoulos

- Tree Data Structures: “Algorithms, Fourth Edition” Chapter 3 - Sedgewick & Wayne

- Merkle Proofs: Bitcoin Wiki - Merkle Trees

Difficulty

Intermediate

Time estimate

1 week

Prerequisites

Project 1 (hash functions), tree data structures

Real world outcome

$ ./merkle build --data transactions.json

Leaves: [tx1_hash, tx2_hash, tx3_hash, tx4_hash]

Tree Structure:

[ROOT: 3a7f...]

/ \

[ab12...] [cd34...]

/ \ / \

[tx1] [tx2] [tx3] [tx4]

Merkle Root: 3a7f8b2c...

$ ./merkle prove --index 2 --root 3a7f8b2c...

Proof for tx3:

- Sibling[0]: cd34... (right)

- Sibling[1]: ab12... (left)

$ ./merkle verify --leaf tx3_hash --proof proof.json --root 3a7f8b2c...

✓ Proof VALID - tx3 is in tree with root 3a7f8b2c...

Implementation Hints

Build bottom-up: hash pairs of nodes to create parent level. Handle odd counts by duplicating the last node. For proofs, track whether each sibling is left or right.

Pseudo-code:

function build_tree(leaves):

current_level = [hash(leaf) for leaf in leaves]

tree = [current_level]

while len(current_level) > 1:

next_level = []

for i in 0..len(current_level) step 2:

left = current_level[i]

right = current_level[i+1] if i+1 < len else left

next_level.append(hash(left + right))

tree.append(next_level)

current_level = next_level

return tree

function generate_proof(tree, index):

proof = []

for level in tree[:-1]: // exclude root

sibling_index = index ^ 1 // flip last bit

is_left = index % 2 == 1

proof.append({hash: level[sibling_index], is_left: is_left})

index = index // 2

return proof

Learning milestones

- Tree construction matches known test vectors → You understand the algorithm

- Proofs verify correctly → You understand trustless verification

- Changing one leaf changes the root → You understand data integrity

- Sparse Merkle tree works → You understand Ethereum’s state model

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How can you prove data exists in a massive dataset without downloading the entire dataset?”

This is the scalability breakthrough that makes blockchain practical. Bitcoin blocks can contain thousands of transactions (multiple MB of data). Without Merkle trees, every node would need to download and verify every transaction. With Merkle proofs, a light client can verify a transaction’s inclusion by downloading only log₂(n) hashes—about 10 hashes for 1000 transactions, about 20 hashes for 1 million transactions.

The magic: the Merkle root in the block header commits to ALL transactions. Changing even one bit in one transaction changes the root completely. Yet you can prove inclusion of ANY transaction with just a tiny proof.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Hash Functions as Commitments

- Why is a hash a “commitment” to data?

- What does it mean that hashes are “collision-resistant”?

-

How does hash(A B) commit to both A and B? - Book Reference: “Serious Cryptography” Ch. 6 - Jean-Philippe Aumasson

- Prerequisite: Project 1 (SHA-256 implementation)

- Binary Tree Data Structures

- What’s the height of a binary tree with n leaves?

- How do you traverse from leaf to root?

- What’s the parent index of node at index i?

- How do you handle odd numbers of children?

- Book Reference: “Algorithms, Fourth Edition” Ch. 3.3 - Sedgewick & Wayne

- Book Reference: “Data Structures the Fun Way” Ch. 8 - Jeremy Kubica

- Proof Systems

- What makes a proof “sound” vs “complete”?

- What’s the difference between a proof of inclusion and proof of exclusion?

- How small can a proof be? (Answer: O(log n) hashes)

- Book Reference: “Mastering Bitcoin” Ch. 9 - Andreas M. Antonopoulos

- Merkle Tree Variants

- Standard Merkle tree vs Merkle Patricia Trie (Ethereum)

- Sparse Merkle trees for state storage

- Why does Bitcoin use different approach than Ethereum?

- Book Reference: “Mastering Ethereum” Ch. 14 - Antonopoulos & Wood

- Web Resource: Understanding Merkle Trees and Proofs

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Tree Construction Algorithm

- How do you handle when the number of leaves isn’t a power of 2?

- Should you duplicate the last leaf or use a different strategy?

- How do you store the tree efficiently? (Array? Nested structs?)

- What’s the space complexity? (Hint: 2n - 1 nodes for n leaves)

- Proof Generation

- Given a leaf index, how do you find its siblings at each level?

- Do you need to store “left” or “right” for each sibling?

- How do you handle the edge case of the last node at odd levels?

- What’s the time complexity of proof generation?

- Proof Verification

- Given a leaf hash and proof, how do you reconstruct the path to root?

-

Do you hash(left right) or hash(right left)? - How do you know which order without storing it?

- Can you verify without rebuilding the entire tree?

- Optimization Challenges

- Can you update a single leaf without rebuilding the tree?

- How do you batch-update multiple leaves efficiently?

- Should you cache intermediate hashes?

- Can you parallelize tree construction?

- Sparse Merkle Trees

- How do you represent a tree with 2^256 possible leaves efficiently?

- What’s the “default hash” for empty nodes?

- How do you prove non-inclusion (that something is NOT in the tree)?

- Why does Ethereum need this for state storage?

Thinking Exercise

Hand-Trace a 4-Leaf Merkle Tree

Build intuition by working through a tiny example on paper:

Given 4 transactions:

tx0 = "Alice -> Bob: 1 BTC"