Video Streaming Deep Dive: From Progressive Download to Adaptive Bitrate

Goal: By completing these 20 projects, you will deeply understand how modern video streaming platforms like Netflix, YouTube, and Twitch work from first principles. You’ll build everything from low-level MP4 parsers that understand container formats and codec structures, to complete adaptive bitrate streaming systems that dynamically adjust quality based on network conditions. You’ll implement the core technologies behind live streaming (RTMP ingest servers, WebRTC peer-to-peer delivery), content delivery networks with edge caching strategies, and digital rights management systems that protect premium content. Most importantly, you’ll understand why the industry evolved from simple progressive download to sophisticated multi-bitrate HLS/DASH protocols, and gain the expertise to debug streaming issues, optimize quality of experience, and architect scalable video platforms that serve millions of concurrent users.

Why Video Streaming Matters

The Dominance of Video in Modern Internet

Video streaming has become the primary use case of the modern internet, fundamentally reshaping how we consume media, learn, communicate, and entertain ourselves:

-

Market Scale: The video streaming market reached $192 billion in 2025 and is projected to grow to $787 billion by 2035 (12.3% CAGR), representing one of the fastest-growing sectors in technology (Video Streaming Market Growth Analysis).

-

Internet Traffic: Video accounts for 82% of global internet traffic in 2025, making it the dominant workload that drives infrastructure decisions from CDN architecture to ISP capacity planning (Video Marketing Statistics).

-

Platform Reach: Netflix alone has 301.6 million users worldwide (market leader), while YouTube serves billions of hours of video daily, and live streaming platforms like Twitch have created entirely new industries (Video Streaming App Report).

-

Protocol Adoption: HLS is used by 78% of streaming platforms, while DASH is used by 56%, with adaptive bitrate streaming being the industry standard that replaced simple progressive download (Bitmovin Survey).

The Evolution: Why Adaptive Streaming Won

Progressive Download Era (2005-2010)

┌────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ HTTP Server │

│ ┌──────────────────────┐ │

│ │ video.mp4 (720p) │ │

│ │ Single bitrate │───────────────► │ User gets buffering on slow networks

│ └──────────────────────┘ │ or wastes bandwidth on fast networks

└────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Adaptive Bitrate Streaming Era (2010-Present)

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Origin Server + CDN Edge Caches │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Manifest (playlist.m3u8 or manifest.mpd) │ │

│ │ ├── 360p @ 800 kbps ──► segments: 0.ts, 1.ts, 2.ts... │ │

│ │ ├── 720p @ 2500 kbps ──► segments: 0.ts, 1.ts, 2.ts... │ │

│ │ ├── 1080p @ 5000 kbps ──► segments: 0.ts, 1.ts, 2.ts... │ │

│ │ └── 4K @ 15000 kbps ──► segments: 0.ts, 1.ts, 2.ts... │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ Client-Side ABR Algorithm │

│ ┌────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Measure: network speed, buffer level │ │

│ │ Decide: switch to optimal bitrate │───────────► Smooth playback

│ │ Request: next segment at chosen quality│ No buffering, optimal quality

│ └────────────────────────────────────────┘ Uses only available bandwidth

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Real-World Impact & Industry Applications

- Streaming Platforms (Netflix, Disney+, HBO Max)

- Multi-CDN strategies to serve 300M+ users globally

- Per-title encoding optimization to reduce bandwidth costs by 30-50%

- A/B testing of ABR algorithms to improve Quality of Experience (QoE)

- Live Streaming (Twitch, YouTube Live, sports broadcasting)

- Ultra-low latency requirements (sub-3 second glass-to-glass)

- RTMP ingest → HLS/DASH distribution pipelines

- WebRTC for interactive streaming (gaming, video calls)

- Enterprise Video (corporate training, video conferencing)

- DRM integration for protected content

- Analytics for viewer engagement and completion rates

- Adaptive streaming for varying corporate network conditions

- Edge Computing & 5G

- CDN edge nodes processing video at the network edge

- Mobile-first adaptive streaming for cellular networks

- Real-time transcoding to optimize for device capabilities

Why Engineers Need to Understand This Deeply

-

Debugging Production Issues: When users report buffering, you need to understand whether it’s a CDN cache miss, ABR algorithm failing to downshift, or segment duration misconfiguration.

-

Cost Optimization: Video delivery is expensive (bandwidth costs can reach millions/month). Understanding codec efficiency (H.265 vs. H.264), segment sizing, and CDN hit ratios directly impacts infrastructure costs.

-

Quality of Experience: The difference between a good and great streaming platform is in the details: startup time, rebuffering ratio, bitrate switching smoothness, and live latency.

-

Architectural Decisions: Should you use HLS or DASH? What segment duration? How many bitrate ladders? These decisions require deep understanding of trade-offs.

Core Concept Analysis

To truly understand how YouTube works, you need to grasp these fundamental layers:

Layer 1: Video Basics (The “What”)

- Container formats: MP4, WebM, MKV are just “boxes” holding video/audio streams

- Codecs: H.264, H.265, VP9, AV1 - compression algorithms that make video transmittable

- Resolution & Bitrate: The fundamental tradeoff between quality and bandwidth

Layer 2: Delivery Evolution (The “How It Changed”)

- Progressive Download (Pre-2007): Download the whole file, play as it downloads

- Pseudo-streaming (2007-2010): Seek to any point, server sends from there

- Adaptive Streaming (2010-present): Multiple quality levels, switch on-the-fly

Layer 3: Modern Streaming Architecture (The “How It Works Now”)

- HLS/DASH protocols: Video split into 2-10 second chunks, served over plain HTTP

- Manifest files: Playlists that tell the player what chunks exist at what quality

- ABR algorithms: Client-side logic deciding which quality to fetch next

- CDN edge caching: Video chunks cached at 200+ global locations

Layer 4: Real-Time (The “Live” Challenge)

- RTMP ingest: How creators push live video to YouTube

- Low-latency HLS/DASH: Reducing the 10-30 second delay

- WebRTC: Sub-second latency for video calls

The Historical Context: Why Streaming Was Hard

Before diving into projects, understand why this problem was unsolved for so long:

1995-2005: The Dark Ages

- Videos were downloaded completely before playing

- A 3-minute video at 320x240 was 15MB - took 30+ minutes on dial-up

- RealPlayer and Windows Media Player tried proprietary streaming (terrible)

- Flash Video (.flv) emerged but still required full download

2005-2010: The YouTube Revolution

- YouTube launched using Flash with progressive download

- “Buffering” spinner became iconic - you’d wait, watch 30 seconds, wait again

- Key insight: HTTP works everywhere, proprietary protocols get blocked

2010-Present: Adaptive Streaming

- Apple invented HLS (HTTP Live Streaming) for iPhone

- DASH (Dynamic Adaptive Streaming over HTTP) became the open standard

- Key insight: Split video into small HTTP-fetchable chunks, let client choose quality

Prerequisites & Background Knowledge

Essential Prerequisites (Must Have)

Before starting these projects, you should have:

- Programming Fundamentals

- Proficiency in at least one language (Python, C, Go, or Rust recommended)

- Understanding of HTTP protocols and REST APIs

- Basic command-line skills and text editor/IDE familiarity

- Networking Basics

- TCP/IP fundamentals (what IP addresses, ports, and sockets are)

- HTTP request/response cycle

- Understanding of bandwidth, latency, and throughput

- Binary & Data Formats

- Hexadecimal notation

- Byte order (big-endian vs little-endian)

- Basic file I/O operations

- Web Development (for player projects)

- HTML5

<video>tag basics - JavaScript DOM manipulation

- Browser developer tools (Network tab, Console)

- HTML5

Helpful But Not Required

These topics will be learned through the projects, but having exposure helps:

- Video/Audio Concepts: Frame rates, codecs, bitrates

- Async Programming: Promises, callbacks, event loops

- Systems Programming: C pointers, memory management

- Docker/Containers: For deployment projects

- WebRTC: For P2P projects

Self-Assessment Questions

Can you answer YES to these questions?

- Can you write a program that reads a binary file and prints bytes in hex?

- Do you understand what an HTTP GET request looks like at the protocol level?

- Can you explain what a “codec” is in one sentence?

- Have you used browser DevTools to inspect network requests?

- Can you write a simple HTTP server in your chosen language?

If you answered YES to 4+, you’re ready. If not, consider reviewing HTTP and binary file basics first.

Development Environment Setup

Required Tools:

# FFmpeg - The Swiss Army knife of video

brew install ffmpeg # macOS

apt install ffmpeg # Ubuntu/Debian

choco install ffmpeg # Windows

# Verify installation

ffmpeg -version

ffprobe -version # Analyze video files

Recommended Tools:

- Media Inspector: MediaInfo - GUI for analyzing video files

- Network Analysis: Wireshark or Chrome DevTools Network tab

- Hex Editor: HexFiend (macOS), HxD (Windows),

hexdump(Linux) - Video Test Files: Big Buck Bunny - free test content

Optional Cloud Accounts (for later projects):

- AWS Free Tier (for CDN projects)

- Cloudflare Workers (for edge computing)

- GitHub Pages (for hosting players)

Time Investment

Realistic Estimates Per Project:

- Beginner Projects (1-5): 2-5 days each (part-time)

- Intermediate Projects (6-12): 1-2 weeks each

- Advanced Projects (13-19): 2-4 weeks each

- Capstone Project (20): 4-8 weeks

Total Time for All 20 Projects: 6-12 months (part-time), 3-6 months (full-time)

Important Reality Check

These projects are challenging. You will:

- Get stuck debugging binary parsing errors

- Spend hours reading RFCs and specifications

- Rebuild things 2-3 times as understanding deepens

- Encounter cryptic FFmpeg errors

- Deal with timing bugs in video players

This is normal and valuable. The struggle is where the learning happens. When you’re stuck:

- Read the relevant book chapter listed

- Use

ffprobeto analyze video files - Check the RFCs/specs (they’re drier than books but authoritative)

- Build a minimal test case to isolate the issue

- Ask specific questions in communities (Stack Overflow, Discord)

Concept Summary Table

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize |

|---|---|

| Container Formats | MP4, WebM, and MKV are “boxes within boxes” - structured binary formats that package video/audio streams with metadata. Not the video itself, but the wrapper. |

| Codecs & Compression | H.264, H.265, VP9, AV1 are compression algorithms. They turn raw frames (50 Mbps) into transmittable streams (5 Mbps) using temporal/spatial compression. |

| Progressive Download | The pre-streaming era: download a file, play as it arrives. HTTP Range requests enable seeking. Simple but inflexible. |

| Adaptive Bitrate Streaming (ABR) | The modern approach: encode video at multiple quality levels, split into chunks, let client choose quality per-chunk based on network speed. |

| HLS vs DASH | HLS (Apple’s .m3u8) and DASH (industry standard .mpd) are chunk-based protocols. Same concept, different manifest formats. |

| Manifests & Playlists | Text files that list available chunks, qualities, and URLs. The “table of contents” for streaming. |

| Client-Side ABR Algorithms | Logic that measures network speed and buffer level to decide which quality chunk to fetch next. The “brain” of adaptive streaming. |

| CDN Edge Caching | Video chunks cached at 200+ global locations. Reduces latency and origin load. Critical for scale. |

| Live Streaming (RTMP/HLS) | RTMP ingest (upload) → transcoding → HLS/DASH (delivery). Adds 10-30 second delay. |

| WebRTC | Peer-to-peer video with sub-second latency. Completely different architecture (UDP, not HTTP). Used for video calls. |

| DRM (Digital Rights Management) | Encryption + license servers to protect premium content. Widevine, PlayReady, FairPlay. |

| Quality Metrics (QoE) | VMAF, SSIM, PSNR - objective measures of video quality. Rebuffering ratio, startup time - user experience metrics. |

Deep Dive Reading by Concept

This section maps each concept from above to specific book chapters for deeper understanding. Read these before or alongside the projects to build strong mental models.

Video Fundamentals

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Container Formats (MP4, WebM) | “Practical Binary Analysis” by Dennis Andriesse — Ch. 2: “The ELF Format” (sections 2.1–2.3) (Apply binary parsing techniques to video containers) |

| Codecs & Compression | “Digital Video and HD” by Charles Poynton — Ch. 9: “Raster Images” & Ch. 20: “Video Compression” |

| Frame Types (I, P, B frames) | “Digital Video and HD” by Charles Poynton — Ch. 20: “Video Compression” (sections on GOP structure) |

| Bitrate vs Quality Tradeoff | “High Performance Browser Networking” by Ilya Grigorik — Ch. 16: “Optimizing Application Delivery” |

HTTP & Networking

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| HTTP Protocol Basics | “TCP/IP Illustrated, Volume 1” by W. Richard Stevens — Ch. 14: “TCP Connection Management” |

| HTTP Range Requests | RFC 7233 — Sections 2 (“Range Units”) and 4 (“Responses”) Free online: https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc7233 |

| CDN Architecture | “High Performance Browser Networking” by Ilya Grigorik — Ch. 14: “Primer on Web Performance” |

| Bandwidth Estimation | “Computer Networks, Fifth Edition” by Tanenbaum & Wetherall — Ch. 5: “The Network Layer” (section 5.3 on congestion control) |

Streaming Protocols

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| HLS (HTTP Live Streaming) | RFC 8216 — Apple’s HLS specification Free online: https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc8216 |

| DASH (Dynamic Adaptive Streaming) | ISO/IEC 23009-1 specification (overview available free) |

| Adaptive Bitrate Algorithms | Academic paper: “A Survey on Bitrate Adaptation Schemes for Streaming Media Over HTTP” — IEEE 2019 |

| Segmentation & Chunking | “Streaming Systems” by Tyler Akidau et al. — Ch. 2: “The What, Where, When, and How of Data Processing” |

Live Streaming

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| RTMP Protocol | “Programming with RTMP” — Free guide from Adobe (archived) |

| WebRTC Fundamentals | “High Performance Browser Networking” by Ilya Grigorik — Ch. 18: “WebRTC” |

| Low-Latency HLS | Apple Developer Documentation — “Enabling Low-Latency HLS” |

Advanced Topics

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| DRM (Widevine, PlayReady) | W3C Encrypted Media Extensions (EME) specification Free online: https://www.w3.org/TR/encrypted-media/ |

| Video Quality Metrics (VMAF) | Netflix Tech Blog — “Toward A Practical Perceptual Video Quality Metric” |

| FFmpeg Internals | “FFmpeg Basics” by Frantisek Korbel — Entire book (covers command-line usage and concepts) |

Essential Reading Order

For maximum comprehension, read in this order:

- Foundation (Week 1):

- “High Performance Browser Networking” Ch. 14 (HTTP basics)

- RFC 7233 (Range requests)

- “Digital Video and HD” Ch. 9 (raster images)

- Streaming Protocols (Week 2-3):

- RFC 8216 (HLS) — skim sections 4 and 6

- “High Performance Browser Networking” Ch. 16 (delivery optimization)

- DASH specification overview

- Advanced Topics (Week 4+):

- “Practical Binary Analysis” Ch. 2 (for MP4 parser)

- “High Performance Browser Networking” Ch. 18 (WebRTC)

- Netflix VMAF paper

Quick Start: Your First 48 Hours

Feeling overwhelmed by 20 projects? Start here.

Day 1: See It Working (2-3 hours)

Goal: Understand what you’re building toward by playing with finished tools.

- Download test video:

wget http://commondatastorage.googleapis.com/gtv-videos-bucket/sample/BigBuckBunny.mp4 - Analyze with ffprobe:

ffprobe -v quiet -print_format json -show_format -show_streams BigBuckBunny.mp4 > analysis.json cat analysis.json | grep -A 5 "codec_name"What you’re seeing: Container format, codecs, bitrates - the “DNA” of the video.

- Serve with Range requests:

python3 -m http.server 8080Open browser to

http://localhost:8080/BigBuckBunny.mp4. Seek around. Open DevTools Network tab. See theRangerequests. - Generate HLS chunks:

ffmpeg -i BigBuckBunny.mp4 \ -c:v copy -c:a copy \ -f hls -hls_time 6 -hls_playlist_type vod \ output.m3u8 ls -lh output*.ts # See the chunks! cat output.m3u8 # See the manifest!

What you learned: The progression from monolithic file → HTTP-served file → chunked HLS.

Day 2: Build Something (3-4 hours)

Goal: Get your hands dirty with Project 2 (simplest web project).

Follow Project 2 (Progressive Download Server) and build a Python server that:

- Serves a video file

- Handles Range requests

- Visualizes buffering

By end of Day 2, you’ll have a working video server and understand HTTP Range requests.

Next Steps

After the first 48 hours, choose a learning path below based on your interests.

Recommended Learning Paths

Different engineers need different journeys. Choose your path:

Path 1: The Full Stack Engineer (Web-Focused)

Goal: Build video platforms (think YouTube clone).

Projects in Order:

- Project 2 (Progressive Download) → Understand HTTP delivery

- Project 4 (HLS Segmenter) → Learn chunking

- Project 5 (HLS Player) → Build client-side player

- Project 6 (ABR Algorithm) → Implement adaptive bitrate

- Project 8 (Mini-CDN) → Add caching

- Project 20 (YouTube Clone) → Capstone

Time: 3-4 months part-time

Skills Gained: End-to-end streaming platform, deployable portfolio project

Path 2: The Systems Engineer (Low-Level Focused)

Goal: Understand video internals, debug production issues.

Projects in Order:

- Project 1 (MP4 Parser) → Binary formats

- Project 14 (MPEG-TS Demuxer) → Transport streams

- Project 3 (Transcoder) → FFmpeg pipelines

- Project 10 (VMAF Quality) → Quality metrics

- Project 12 (Codec Comparison) → Compression algorithms

Time: 2-3 months part-time

Skills Gained: Deep video expertise, debugging skills, performance optimization

Path 3: The Live Streaming Specialist

Goal: Build Twitch-like live platforms.

Projects in Order:

- Project 2 (Progressive Download) → HTTP basics

- Project 7 (RTMP to HLS) → Live pipeline

- Project 9 (WebRTC) → P2P streaming

- Project 18 (LL-HLS) → Low-latency streaming

- Project 11 (Bandwidth Estimator) → Network simulation

Time: 3-4 months part-time

Skills Gained: Real-time video systems, low-latency optimization

Path 4: The Infrastructure Engineer (Scale-Focused)

Goal: Optimize for millions of users.

Projects in Order:

- Project 8 (Mini-CDN) → Edge caching

- Project 16 (Thumbnail Generator) → Batch processing

- Project 19 (Analytics Pipeline) → Data collection

- Project 17 (P2P Delivery) → Distribution optimization

- Project 20 (YouTube Clone) → Full system integration

Time: 4-5 months part-time

Skills Gained: Scalability, cost optimization, distributed systems

Path 5: The Interview Prep Path (Fastest)

Goal: Understand core concepts for FAANG interviews in 1 month.

Projects in Order:

- Project 1 (MP4 Parser) → Binary parsing (systems design)

- Project 5 (HLS Player) → Event-driven architecture

- Project 6 (ABR Algorithm) → Algorithm design

- Project 8 (Mini-CDN) → Caching strategies

- Project 11 (Bandwidth Estimator) → Network protocols

Time: 4-6 weeks intensive (full-time equivalent)

Skills Gained: Interview-relevant depth, design pattern knowledge

Project 1: Video File Dissector (Container Format Parser)

- File: VIDEO_STREAMING_DEEP_DIVE_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Python, Go

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Binary Parsing / Media Containers

- Software or Tool: MP4/WebM Parser

- Main Book: “Practical Binary Analysis” by Dennis Andriesse

What you’ll build: A tool that opens MP4/WebM files and displays their internal structure - showing you exactly where the video frames, audio samples, and metadata live inside the file.

Why it teaches video fundamentals: Before you can stream video, you must understand what video IS. An MP4 file isn’t a blob of pixels—it’s a carefully structured binary format with “atoms” (boxes) containing codec info, timestamps, keyframe locations, and compressed frame data. This knowledge is essential for understanding why seeking is instant vs slow, why some videos won’t play, and how streaming protocols work.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Binary parsing (reading bytes, handling endianness) → maps to understanding file formats

- Recursive structures (atoms contain atoms contain atoms) → maps to container hierarchy

- Codec identification (finding the avc1/hev1/vp09 codec box) → maps to codec awareness

- Timestamp math (timescale, duration, sample tables) → maps to media timing

- Finding keyframes (sync sample table) → maps to why seeking works

Key Concepts:

- Binary File Parsing: “Practical Binary Analysis” Chapter 2 - Dennis Andriesse

- MP4 Box Structure: ISO 14496-12 specification (free online) - ISO/IEC

- Endianness & Byte Order: “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” Chapter 2 - Bryant & O’Hallaron

- Media Timing: “Digital Video and HD” Chapter 20 - Charles Poynton

Difficulty: Intermediate-Advanced Time estimate: 1-2 weeks Prerequisites: C basics, familiarity with binary/hex

Real world outcome:

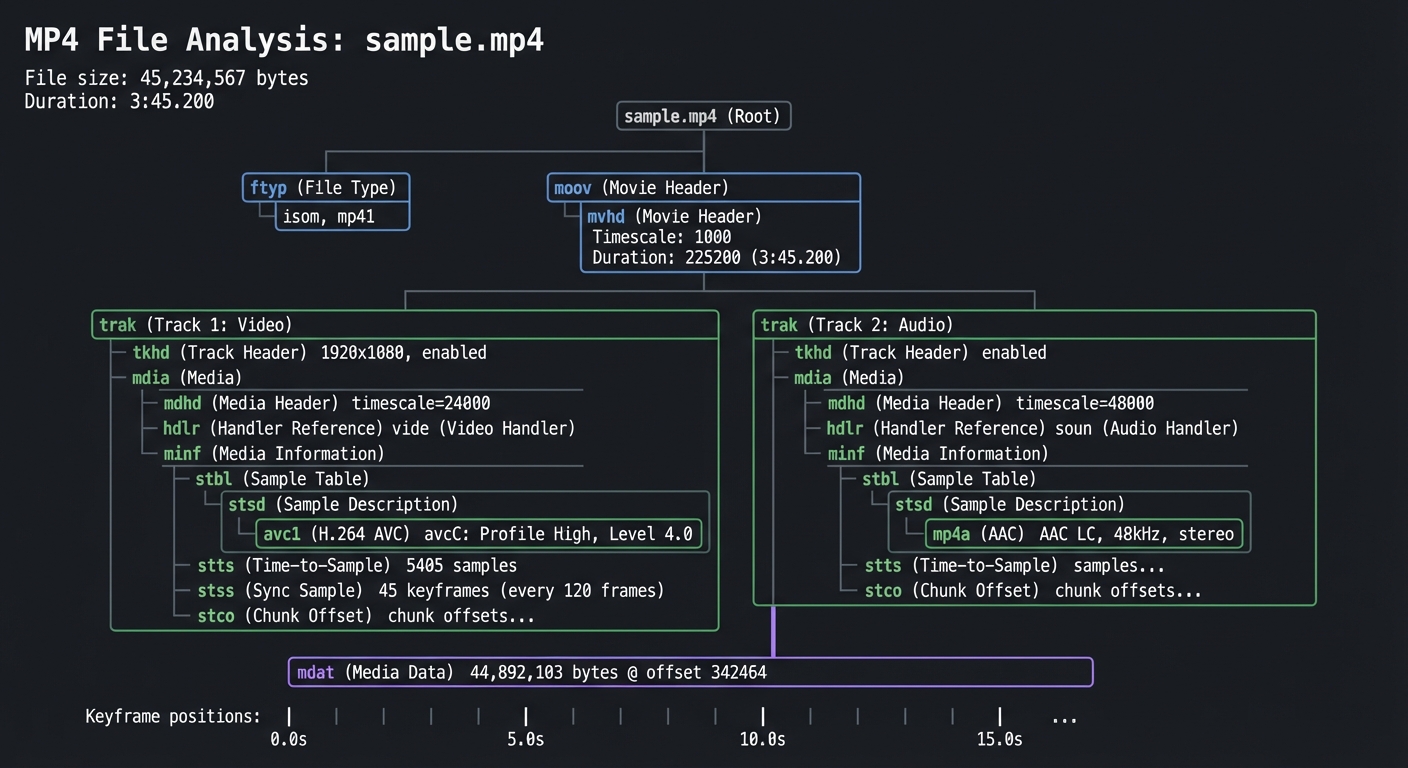

$ ./mp4dissect sample.mp4

MP4 File Analysis: sample.mp4

================================

File size: 45,234,567 bytes

Duration: 3:45.200

Container Structure:

├── ftyp (File Type): isom, mp41

├── moov (Movie Header)

│ ├── mvhd (Movie Header)

│ │ ├── Timescale: 1000

│ │ └── Duration: 225200 (3:45.200)

│ ├── trak (Track 1: Video)

│ │ ├── tkhd: 1920x1080, enabled

│ │ └── mdia

│ │ ├── mdhd: timescale=24000

│ │ ├── hdlr: vide (Video Handler)

│ │ └── minf/stbl

│ │ ├── stsd: avc1 (H.264 AVC)

│ │ │ └── avcC: Profile High, Level 4.0

│ │ ├── stts: 5405 samples

│ │ ├── stss: 45 keyframes (every 120 frames)

│ │ └── stco: chunk offsets...

│ └── trak (Track 2: Audio)

│ └── ... (AAC LC, 48kHz, stereo)

└── mdat (Media Data): 44,892,103 bytes @ offset 342464

Keyframe positions: 0.0s, 5.0s, 10.0s, 15.0s...

Implementation Hints: MP4 files use a “box” (or “atom”) structure. Each box has:

- 4 bytes: size (big-endian)

- 4 bytes: type (ASCII, like ‘moov’, ‘trak’, ‘mdat’)

- (size-8) bytes: payload

Some boxes are containers (moov, trak, mdia) and contain other boxes. Others are leaf boxes with actual data. Start by reading the file and printing all top-level boxes. Then recursively parse container boxes.

The ‘stss’ (Sync Sample) box tells you which frames are keyframes—this is crucial for understanding why seeking is fast (you can only seek TO keyframes).

Learning milestones:

- Parse top-level boxes → You understand binary formats

- Navigate the moov/trak hierarchy → You understand container structure

- Extract codec info from stsd → You understand what a “codec” actually means in practice

- Map keyframes to timestamps → You understand why YouTube can seek instantly

The Core Question You’re Answering

“What IS a video file? Is it just pixels and audio, or is there more structure?”

Before you write any code, sit with this question. Most developers think of video files as blobs of frames. In reality, MP4 is an intricate database: a hierarchical structure of “atoms” containing metadata tables (keyframe positions, timestamps, codec configs) and the actual compressed media data. Understanding this structure is the difference between using FFmpeg blindly vs. understanding WHY certain operations are instant (seek) vs. slow (re-encode).

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Binary File Formats

- How do you read 4 bytes and interpret them as a 32-bit integer?

- What is big-endian vs little-endian, and why does it matter?

- How do you navigate a file using byte offsets?

- Book Reference: “Practical Binary Analysis” Ch. 2 (“The ELF Format”) - Dennis Andriesse

- Recursive Tree Structures

- How do you parse a container that contains containers (atoms within atoms)?

- When do you recurse vs. when do you read raw data?

- How do you track your current position in a deeply nested structure?

- Book Reference: “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” Ch. 2 (“Representing and Manipulating Information”) - Bryant & O’Hallaron

- Video Fundamentals

- What is a codec (H.264, H.265, VP9) vs. a container (MP4, WebM)?

- What is a keyframe (I-frame) vs. a delta frame (P/B frames)?

- Why can you only seek TO keyframes, not between them?

- Book Reference: “Digital Video and HD” Ch. 20 (“Video Compression”) - Charles Poynton

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Parsing Strategy

- Will you recursively parse all atoms at once, or lazily parse on-demand?

- How will you handle atoms with unknown types (forward compatibility)?

- Will you build an in-memory tree, or just print as you discover?

- Error Handling

- What if an atom’s size is corrupted (claims to be 2GB but file is 50MB)?

- What if the atom hierarchy is malformed (moov appears after mdat)?

- Will you validate checksums or trust the data?

- Display Format

- How will you visualize the nested structure (tree view, JSON, indented text)?

- Will you display byte offsets for debugging?

- How much detail: just atom types, or full codec configs?

Thinking Exercise

Exercise: Trace an MP4 by Hand

Before coding, download a small MP4 file and open it in a hex editor. Find the first 12 bytes:

Offset Hex ASCII

00000000: 0000 0020 6674 7970 6973 6f6d 0000 0200 ... ftypisom....

└─┬─┘ └─┬─┘

Size Type

Questions while exploring:

- At offset 0: What are the first 4 bytes (in decimal)? That’s the atom size.

- At offset 4: What are the next 4 bytes (as ASCII)? That’s the atom type (‘ftyp’).

- If size is 32 bytes, where does the next atom start?

- Navigate to the ‘moov’ atom. How deep is the nesting?

- Find ‘stsd’ (sample description). Can you identify the codec name in ASCII?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “Explain why seeking is instant in some video files but slow in others.”

- “You’re building a video streaming service. Why do you need to understand container formats?”

- “A user reports that your player won’t seek past 1:30 in a 5-minute video. What could cause this?”

- “What’s the difference between a codec and a container? Give examples.”

- “Walk me through what happens when a browser requests a 10MB MP4 file with Range: bytes=5000000-5999999.”

- “Why do MP4 files have ‘moov’ before ‘mdat’ for streaming, but ‘mdat’ before ‘moov’ for download?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start Simple Don’t parse everything at once. Write a function that reads one atom: size (4 bytes, big-endian uint32), type (4 bytes ASCII), then skip the payload. Print all top-level atoms first.

Hint 2: Handle Container Atoms Certain atom types (‘moov’, ‘trak’, ‘mdia’, ‘minf’, ‘stbl’) are containers. After reading their header (8 bytes), their payload contains child atoms. Recursively parse these.

Hint 3: Extract Keyframe Data The ‘stss’ atom contains the “sync sample table”—a list of frame numbers that are keyframes. It’s in ‘moov/trak/mdia/minf/stbl/stss’. The structure is:

uint32_t version_flags; // Usually 0

uint32_t entry_count;

uint32_t sample_numbers[entry_count]; // 1-indexed frame numbers

Hint 4: Debugging Tools

Use ffprobe to verify your parsing:

ffprobe -v quiet -print_format json -show_format -show_streams file.mp4

Compare your output to ffprobe’s. Use a hex editor to cross-reference byte offsets.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Binary File Parsing | “Practical Binary Analysis” by Dennis Andriesse | Ch. 2: “The ELF Format” (apply techniques to MP4) |

| Endianness & Byte Order | “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” by Bryant & O’Hallaron | Ch. 2: “Representing and Manipulating Information” (sections 2.1-2.3) |

| MP4 Container Spec | ISO/IEC 14496-12 (Free online) | Sections 4-8 (atom structure) |

| Video Compression Basics | “Digital Video and HD” by Charles Poynton | Ch. 20: “Video Compression” |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem 1: “My parser claims the file is 4GB but it’s only 10MB”

- Why: You’re reading the size field as little-endian instead of big-endian. MP4 uses network byte order (big-endian).

- Fix: Use

ntohl()in C orstruct.unpack('>I', bytes)in Python. - Quick test: The first atom is always ‘ftyp’, usually 20-32 bytes. If your size is wrong, endianness is the culprit.

Problem 2: “I can’t find the codec information”

- Why: You’re not recursing into ‘moov/trak/mdia/minf/stbl/stsd’.

- Fix: Print the full path as you traverse. The codec is in the ‘stsd’ atom, which contains child atoms like ‘avc1’ (H.264), ‘hev1’ (H.265), ‘vp09’ (VP9).

- Quick test:

ffprobeshows codec_name. Cross-reference with your output.

Problem 3: “Some atoms have weird sizes (1 or 0)”

- Why: Size 1 means the atom uses extended size (next 8 bytes are the real size). Size 0 means “rest of the file”.

- Fix: Check if size == 1, read 8 more bytes for the real size. If size == 0 and atom type is ‘mdat’, it extends to EOF.

- Quick test: Large files (>4GB) often use extended size for ‘mdat’.

Problem 4: “Keyframe table shows frame 1, 121, 241… What’s the timestamp?”

- Why: Frame numbers aren’t timestamps. You need the ‘stts’ (time-to-sample) table to convert frame numbers to time.

- Fix: ‘stts’ is a run-length-encoded table: “frames 1-120 have duration 41 (1/24000 sec each)”. Sum up durations.

- Quick test:

ffprobe -show_frames file.mp4 | grep key_frameshows actual keyframe timestamps.

Project 2: Progressive Download Server & Player

- File: VIDEO_STREAMING_DEEP_DIVE_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: Python

- Alternative Programming Languages: Go, Node.js, Rust

- Coolness Level: Level 2: Practical but Forgettable

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: HTTP / Network Protocols

- Software or Tool: HTTP Server

- Main Book: “TCP/IP Illustrated, Volume 1” by W. Richard Stevens

What you’ll build: A simple HTTP server that serves video files with proper support for Range requests, and a web page that plays video showing exactly what bytes are being downloaded in real-time.

Why it teaches pre-streaming video: This is how YouTube worked in 2005-2008. The browser requests the video file, the server sends bytes, the <video> tag buffers and plays. But here’s the magic—HTTP Range requests let you seek! When you click the progress bar, the browser sends Range: bytes=1000000- and the server responds with just those bytes. Understanding this is the foundation for understanding why modern streaming works.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- HTTP Range requests (parsing Range header, responding with 206 Partial Content) → maps to seeking mechanism

- Content-Length and Accept-Ranges headers → maps to seekability negotiation

- Buffering visualization (showing what’s downloaded vs playing) → maps to buffer understanding

- Bandwidth throttling (simulate slow connections) → maps to understanding buffering

Key Concepts:

- HTTP Range Requests: RFC 7233 - IETF (read sections 2 and 4)

- HTTP Protocol: “TCP/IP Illustrated, Volume 1” Chapter 14 - W. Richard Stevens

- HTML5 Video API: MDN Web Docs - Mozilla

- Buffer Management: “High Performance Browser Networking” Chapter 16 - Ilya Grigorik

Difficulty: Beginner-Intermediate Time estimate: 3-5 days Prerequisites: Basic Python, HTTP understanding

Real world outcome:

$ python progressive_server.py --port 8080 --video big_buck_bunny.mp4

Serving video on http://localhost:8080

Open browser, see:

- Video player with progress bar

- Real-time visualization showing:

- Blue bar: bytes downloaded

- Green bar: playback position

- Red markers: keyframe positions

- Network log showing each Range request:

GET /video.mp4 Range: bytes=0-999999 → 206 (1MB) GET /video.mp4 Range: bytes=1000000-1999999 → 206 (1MB) [User seeks to 2:30] GET /video.mp4 Range: bytes=45000000-45999999 → 206 (1MB)

Implementation Hints:

The key insight is that browsers handle most of the work. When you provide Accept-Ranges: bytes in your response headers, the browser knows it can request specific byte ranges.

Your server needs to:

- Check for

Rangeheader in requests - If present, parse

bytes=START-ENDformat - Return status 206 (not 200) with

Content-Rangeheader - Send only the requested bytes

Bonus: Add bandwidth throttling (time.sleep() between chunks) to simulate slow connections and watch buffering behavior.

Learning milestones:

- Basic file serving works → You understand HTTP fundamentals

- Range requests enable seeking → You understand how “skip to 2:00” works without downloading everything

- Buffer visualization shows fetch-ahead → You understand why videos “buffer”

- Throttled connection shows buffering pain → You understand why adaptive streaming was invented

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How can a user jump to any point in a video without downloading the entire file first?”

This question drove the entire evolution of web video. Before HTTP Range requests, seeking required downloading everything up to that point, or using proprietary protocols like RTSP. Understanding why Range requests work—and their limitations—explains why we eventually needed adaptive streaming protocols like HLS and DASH.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- HTTP Request/Response Cycle

- What happens between when you type a URL and when bytes arrive?

- How does TCP connection establishment relate to HTTP?

- Book Reference: “TCP/IP Illustrated, Volume 1” Ch. 14 - W. Richard Stevens

- HTTP Status Codes (206 vs 200)

- Why does 206 Partial Content exist as a separate status?

- What happens if you send 200 OK with only partial bytes?

- Book Reference: RFC 7233 Sections 2 and 4

- File I/O and Byte Seeking

- How does

file.seek()work at the operating system level? - What’s the performance difference between sequential and random access?

- Book Reference: “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” Ch. 10 - Bryant & O’Hallaron

- How does

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Range Request Parsing

- How will you handle

Range: bytes=0-499,bytes=500-, andbytes=-500? - What should you do if the range is invalid or exceeds file size?

- How will you handle

- Connection Management

- Should you support keep-alive connections for sequential range requests?

- How many simultaneous connections should a player be allowed to make?

- Buffer Strategy

- Should your server pre-fetch the next likely range request?

- How much should the browser buffer ahead of current playback position?

Thinking Exercise

Before writing code, trace this scenario on paper:

A user opens your video player. The video is 100MB, 10 minutes long. Trace:

- What HTTP requests are sent in the first 5 seconds?

- User seeks to 5:00 (50% through). What requests now?

- Connection drops to 100 KB/s (was 1 MB/s). What happens to playback?

Draw the timeline with bytes downloaded vs bytes played. Where does it break?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “Explain the difference between HTTP 200 and 206 responses. When would you use each?”

- “A user seeks to 80% through a video, then immediately seeks back to 10%. How many bytes did they waste downloading?”

- “Why can’t progressive download support live streaming?”

- “How would you implement bandwidth throttling without affecting other HTTP traffic on the system?”

- “What’s the relationship between video keyframes and seek accuracy in progressive download?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with the headers

The browser tells you what it wants. Read the Range header, parse it, check if it’s valid against your file size.

Hint 2: Use the right status code

If you see a Range header, respond with 206, not 200. Include Content-Range: bytes START-END/TOTAL and Content-Length: (END-START+1).

Hint 3: Python file seeking

with open('video.mp4', 'rb') as f:

f.seek(start_byte)

chunk = f.read(end_byte - start_byte + 1)

Hint 4: Verify with curl Test your server without a browser first:

curl -H "Range: bytes=0-999" http://localhost:8080/video.mp4 -v

# Should see: HTTP/1.1 206 Partial Content

# Should see: Content-Range: bytes 0-999/FILESIZE

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter | |——-|——|———| | HTTP Protocol Fundamentals | “TCP/IP Illustrated, Volume 1” by W. Richard Stevens | Ch. 14 | | Range Requests Specification | RFC 7233 (free online) | Sections 2, 4 | | Browser Networking Behavior | “High Performance Browser Networking” by Ilya Grigorik | Ch. 14, 16 | | File I/O and Buffering | “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” by Bryant & O’Hallaron | Ch. 10 | | HTML5 Video API | MDN Web Docs (free online) | Video/Audio APIs |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem 1: “Seeking doesn’t work - video restarts from beginning”

- Why: You’re sending 200 OK instead of 206 Partial Content, so browser thinks it’s a new file

- Fix: Check your status code logic. If

Rangeheader exists, use 206 - Quick test:

curl -I -H "Range: bytes=0-999" http://localhost:8080/video.mp4should show206

Problem 2: “Video plays but seeking is slow/unreliable”

- Why: Your file seeks are inefficient, or you’re reading too much into memory

- Fix: Use

os.stat()to get file size without reading. Seek directly to byte offset - Quick test: Add logging for file.seek() calls and chunk sizes

Problem 3: “Browser makes dozens of tiny range requests”

- Why: Browser is trying to fetch exact byte ranges for optimal buffering

- Fix: This is normal! Modern browsers are smart. Watch the pattern to understand buffering

- Quick test: Open browser DevTools Network tab, filter by your video file

Problem 4: “Content-Length doesn’t match actual bytes sent”

- Why: Off-by-one error in range calculation.

bytes=0-999is 1000 bytes, not 999 - Fix: Length = (end - start + 1)

- Quick test:

curl -H "Range: bytes=0-10" http://localhost:8080/video.mp4 | wc -cshould show 11

Project 3: Video Transcoder & Quality Ladder Generator

- File: VIDEO_STREAMING_DEEP_DIVE_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: Python (with FFmpeg)

- Alternative Programming Languages: Go, Rust, Node.js

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 3. The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Video Encoding / Compression

- Software or Tool: FFmpeg

- Main Book: “Video Encoding by the Numbers” by Jan Ozer

What you’ll build: A tool that takes a source video and generates a complete “quality ladder” - multiple versions at different resolutions and bitrates (1080p, 720p, 480p, 360p, 240p), ready for adaptive streaming.

Why it teaches video encoding: This is exactly what YouTube does when you upload a video. Within minutes, your 4K upload becomes available in 8+ quality levels. Understanding the relationship between resolution, bitrate, and perceptual quality is crucial for understanding why streaming works. A 1080p video can be 1 Mbps (blocky) or 20 Mbps (pristine)—the encoder decides.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Resolution vs bitrate tradeoff → maps to quality perception

- Codec selection (H.264 vs H.265 vs VP9) → maps to compression efficiency

- Two-pass encoding → maps to quality optimization

- Keyframe alignment → maps to why chunks must start with keyframes

- Audio normalization → maps to complete media pipeline

Key Concepts:

- Video Compression Fundamentals: “Video Encoding by the Numbers” Chapter 1-3 - Jan Ozer

- H.264 Encoding: “H.264 and MPEG-4 Video Compression” Chapter 5 - Iain Richardson

- Rate Control: Apple Tech Note TN2224 - Apple Developer

- FFmpeg Usage: FFmpeg official documentation - FFmpeg.org

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 1 week Prerequisites: Command line familiarity, basic video concepts

Real world outcome:

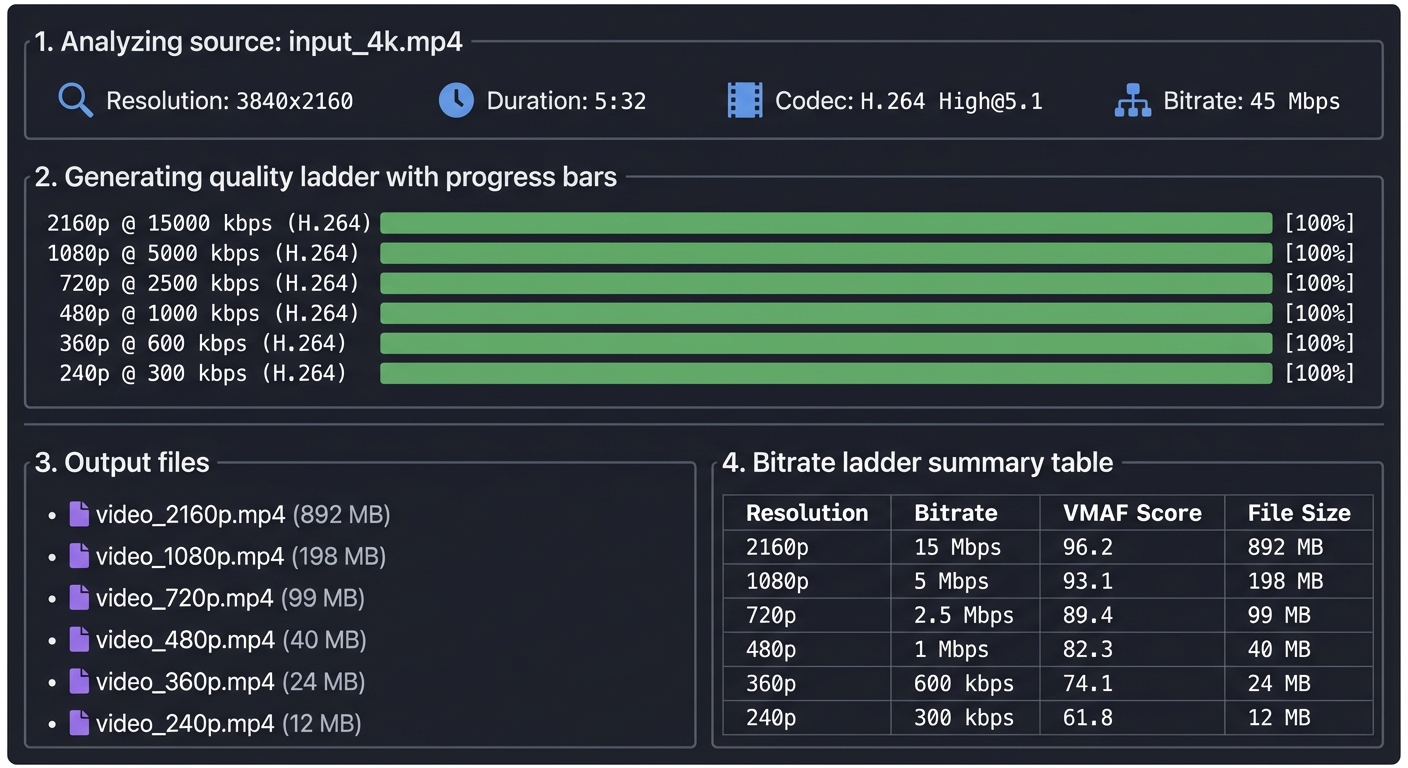

$ ./transcode.py input_4k.mp4 --output-dir ./ladder/

Analyzing source: input_4k.mp4

Resolution: 3840x2160

Duration: 5:32

Codec: H.264 High@5.1

Bitrate: 45 Mbps

Generating quality ladder...

[████████████████████] 2160p @ 15000 kbps (H.264)

[████████████████████] 1080p @ 5000 kbps (H.264)

[████████████████████] 720p @ 2500 kbps (H.264)

[████████████████████] 480p @ 1000 kbps (H.264)

[████████████████████] 360p @ 600 kbps (H.264)

[████████████████████] 240p @ 300 kbps (H.264)

Output:

./ladder/video_2160p.mp4 (892 MB)

./ladder/video_1080p.mp4 (198 MB)

./ladder/video_720p.mp4 (99 MB)

./ladder/video_480p.mp4 (40 MB)

./ladder/video_360p.mp4 (24 MB)

./ladder/video_240p.mp4 (12 MB)

Bitrate ladder summary:

Resolution | Bitrate | VMAF Score | File Size

------------|----------|------------|----------

2160p | 15 Mbps | 96.2 | 892 MB

1080p | 5 Mbps | 93.1 | 198 MB

720p | 2.5 Mbps | 89.4 | 99 MB

480p | 1 Mbps | 82.3 | 40 MB

360p | 600 kbps | 74.1 | 24 MB

240p | 300 kbps | 61.8 | 12 MB

Implementation Hints: FFmpeg is the industry standard tool. Your Python script will call FFmpeg with appropriate parameters. Key FFmpeg flags:

-vf scale=1280:720for resolution-b:v 2500kfor target bitrate-c:v libx264 -preset mediumfor H.264 encoding-g 48 -keyint_min 48for keyframe interval (crucial for streaming!)-x264-params "scenecut=0"to prevent unaligned keyframes

The keyframe alignment is critical: all quality levels must have keyframes at exactly the same timestamps, or switching between qualities mid-stream will fail.

Learning milestones:

- Generate multiple quality levels → You understand resolution/bitrate relationship

- Compare quality at same resolution, different bitrates → You understand why bitrate matters more than resolution

- Align keyframes across all levels → You understand the streaming constraint

- Compare H.264 vs H.265 file sizes → You understand codec efficiency evolution

The Core Question You’re Answering

“Why does the same video at 720p look crystal clear on Netflix but blocky on a low-quality stream?”

Resolution is just pixel count—quality comes from bitrate. A 1080p video encoded at 1 Mbps looks worse than 720p at 5 Mbps. This project forces you to understand the relationship between resolution, bitrate, codec settings, and perceptual quality—the same tradeoffs YouTube, Netflix, and Twitch make when processing uploads.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Video Compression Fundamentals (I/P/B Frames)

- Why can’t you start playback from a P-frame?

- What’s a Group of Pictures (GOP), and why does GOP size matter for streaming?

- Book Reference: “Digital Video and HD” by Charles Poynton - Ch. 20 (Video Compression)

- Bitrate vs Quality Tradeoff

- How does Constant Bitrate (CBR) differ from Variable Bitrate (VBR)?

- Why do streaming services use two-pass encoding?

- Book Reference: “Video Encoding by the Numbers” Ch. 1-3 - Jan Ozer

- Codec Efficiency (H.264 vs H.265 vs AV1)

- What does “50% better compression” mean in practice?

- Why hasn’t H.265 replaced H.264 everywhere?

- Book Reference: “H.264 and MPEG-4 Video Compression” Ch. 5 - Iain Richardson

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Quality Ladder Strategy

- How do you decide which resolutions/bitrates to generate? (240p, 360p, 480p, 720p, 1080p?)

- Should you ever upscale? (e.g., 720p source to 1080p output?)

- Keyframe Alignment

- Why must all quality levels have keyframes at the exact same timestamps?

- What breaks if keyframes are misaligned by even 100ms?

- Encoding Performance

- Should you encode all qualities in parallel or sequentially?

- How would you estimate total encoding time for a 2-hour video?

Thinking Exercise

Before writing code, think through this scenario:

You have a 1080p 60fps source video (10 Mbps bitrate). You need to create:

- 1080p @ 5 Mbps

- 720p @ 3 Mbps

- 480p @ 1.5 Mbps

- 360p @ 0.8 Mbps

For each output:

- What resolution will you target?

- What bitrate will you use?

- What’s your keyframe interval (in seconds and frames)?

- How will you verify keyframes are aligned across all outputs?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “Explain the difference between resolution and bitrate. Which matters more for perceived quality?”

- “Why do streaming platforms use fixed keyframe intervals instead of scene-based keyframe insertion?”

- “How would you determine the optimal bitrate for a 720p stream?”

- “A user complains that quality switching causes brief freezes. What encoding parameter is likely misconfigured?”

- “Why is two-pass encoding better than one-pass for streaming, and when would you skip it?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with FFmpeg basics You don’t need to understand video codecs at the bit level. FFmpeg does the heavy lifting. Your job is to call it with the right parameters.

Hint 2: The critical parameters For streaming-compatible output, you must set:

- Resolution:

-vf scale=W:H - Bitrate:

-b:v XMbpsor-crf XX(Constant Rate Factor) - Keyframe interval:

-g FRAMES -keyint_min FRAMES - Disable scene detection:

-x264-params "scenecut=0"

Hint 3: Alignment verification

Use ffprobe to extract keyframe timestamps:

ffprobe -select_streams v -show_frames -show_entries frame=pkt_pts_time,key_frame \

output_720p.mp4 | grep key_frame=1

Compare timestamps across all quality levels—they should match exactly.

Hint 4: Quality comparison Generate a test file at the same resolution but different bitrates (e.g., 720p @ 1, 2, 3, 5 Mbps). Play them side-by-side. Where do you stop seeing improvement? That’s your diminishing returns point.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter | |——-|——|———| | Video Compression Basics | “Digital Video and HD” by Charles Poynton | Ch. 20 | | Practical Encoding Guide | “Video Encoding by the Numbers” by Jan Ozer | Ch. 1-3 | | H.264 Deep Dive | “H.264 and MPEG-4 Video Compression” by Iain Richardson | Ch. 5 | | FFmpeg Reference | FFmpeg Official Docs (free online) | Encoding Guide | | Adaptive Streaming Encoding | Apple Tech Note TN2224 (free online) | Best Practices |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem 1: “Quality switching causes video freezes or glitches”

- Why: Keyframes are not aligned across quality levels. Player can only switch at keyframes

- Fix: Use fixed keyframe interval (

-g 48 -keyint_min 48for 2-sec at 24fps) and disable scene cut (scenecut=0) - Quick test:

ffprobe -show_framesand grep for keyframes, verify timestamps match across files

Problem 2: “720p output looks worse than the 1080p source, even at high bitrate”

- Why: You might be using a fast preset that sacrifices quality for speed

- Fix: Use

-preset mediumor-preset slow. Slower = better quality at same bitrate - Quick test: Encode same clip with

-preset ultrafastvs-preset slow, compare file sizes and visual quality

Problem 3: “Encoding takes forever (hours for a 10-minute video)”

- Why: Using

-preset veryslowor doing two-pass on every quality level - Fix: For testing, use

-preset fastor-preset medium. Two-pass is optional for local testing - Quick test: Encode a 10-second clip first to estimate time:

(clip_time / 10) * video_duration

Problem 4: “Output file is larger than input, even at lower resolution”

- Why: You’re not setting bitrate constraints. FFmpeg defaults to quality-based encoding (CRF)

- Fix: Use

-b:vfor target bitrate and-maxrate/-bufsizefor rate control - Quick test:

ffprobe output.mp4 | grep bitrateshould show lower bitrate than source

Project 4: HLS Segmenter & Manifest Generator

- File: VIDEO_STREAMING_DEEP_DIVE_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: Python

- Alternative Programming Languages: Go, Rust, C

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 3. The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Streaming Protocols

- Software or Tool: HLS

- Main Book: “High Performance Browser Networking” by Ilya Grigorik

What you’ll build: A tool that takes the quality ladder from Project 3 and segments each quality level into 4-6 second chunks, generating HLS playlists (M3U8 files) that any video player can consume.

Why it teaches streaming: This is the core of how YouTube/Netflix/Twitch work. Instead of one big file, you have thousands of tiny files. The player fetches a playlist, then fetches chunks one by one. If your bandwidth drops, it fetches lower quality chunks. If it improves, it fetches higher quality. This is the magic of adaptive streaming.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Segment boundary alignment (must be on keyframes) → maps to why encoding matters for streaming

- Playlist generation (#EXTINF, #EXT-X-STREAM-INF) → maps to manifest structure

- Master playlist with multiple qualities → maps to adaptive bitrate selection

- Segment duration consistency → maps to buffer management

Key Concepts:

- HLS Specification: RFC 8216 (HTTP Live Streaming) - IETF

- M3U8 Playlist Format: Apple HLS Authoring Specification - Apple Developer

- Segment Alignment: “High Performance Browser Networking” Chapter 16 - Ilya Grigorik

- Adaptive Streaming: “Streaming Media with HTML5” - Nigel Thomas

Difficulty: Intermediate-Advanced Time estimate: 1 week Prerequisites: Project 3 completed, HTTP understanding

Real world outcome:

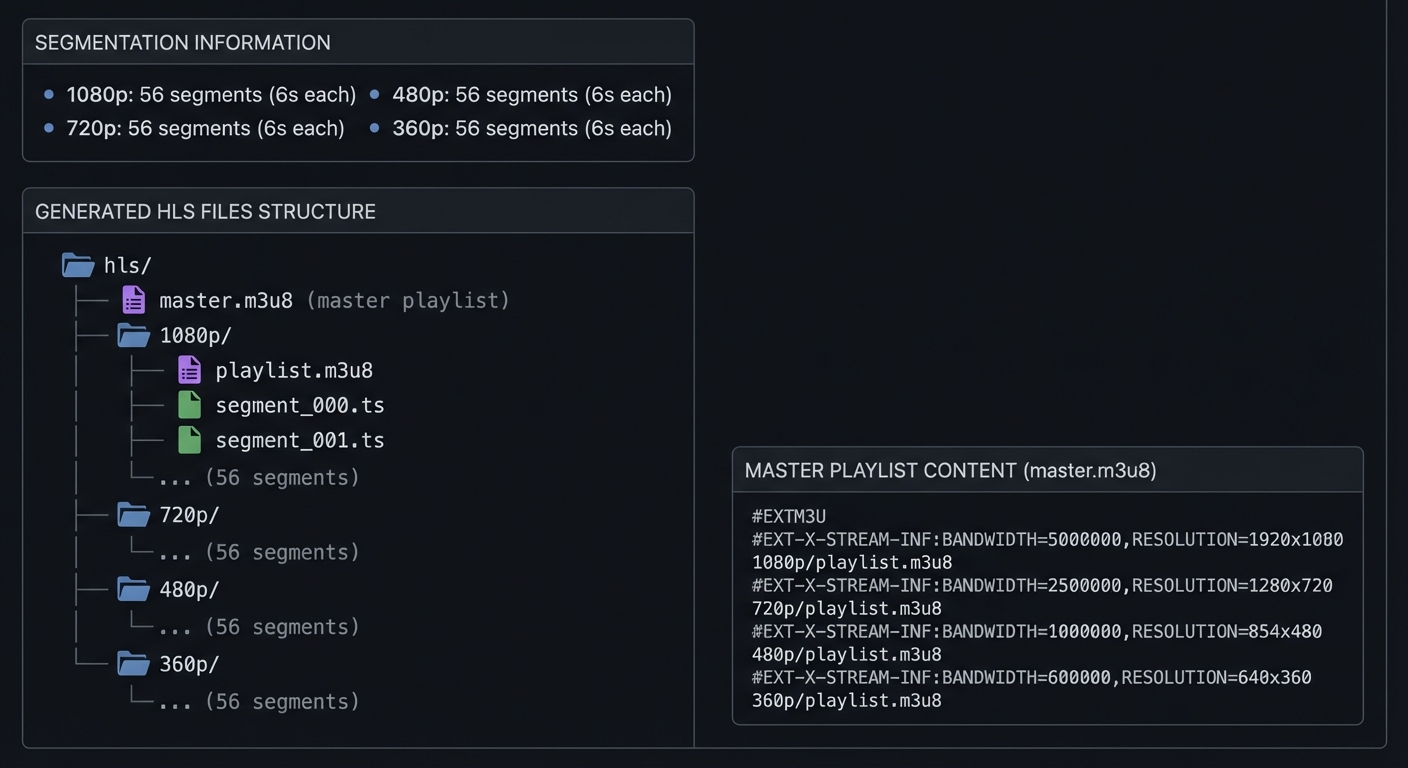

$ ./hls_segmenter.py ./ladder/ --segment-duration 6 --output ./hls/

Segmenting quality levels...

1080p: 56 segments (6s each)

720p: 56 segments (6s each)

480p: 56 segments (6s each)

360p: 56 segments (6s each)

Generated files:

./hls/

├── master.m3u8 (master playlist)

├── 1080p/

│ ├── playlist.m3u8

│ ├── segment_000.ts

│ ├── segment_001.ts

│ └── ... (56 segments)

├── 720p/

│ └── ... (56 segments)

├── 480p/

│ └── ... (56 segments)

└── 360p/

└── ... (56 segments)

Master playlist (master.m3u8):

#EXTM3U

#EXT-X-STREAM-INF:BANDWIDTH=5000000,RESOLUTION=1920x1080

1080p/playlist.m3u8

#EXT-X-STREAM-INF:BANDWIDTH=2500000,RESOLUTION=1280x720

720p/playlist.m3u8

#EXT-X-STREAM-INF:BANDWIDTH=1000000,RESOLUTION=854x480

480p/playlist.m3u8

#EXT-X-STREAM-INF:BANDWIDTH=600000,RESOLUTION=640x360

360p/playlist.m3u8

You can now serve ./hls/ with any HTTP server and play with hls.js or VLC:

$ python -m http.server 8080 --directory ./hls/

# Open http://localhost:8080/master.m3u8 in VLC

Implementation Hints:

Use FFmpeg to create segments: -f hls -hls_time 6 -hls_segment_filename "segment_%03d.ts". But the real learning is understanding what those playlists mean:

Media playlist (per quality):

#EXTM3U

#EXT-X-VERSION:3

#EXT-X-TARGETDURATION:6

#EXT-X-MEDIA-SEQUENCE:0

#EXTINF:6.006,

segment_000.ts

#EXTINF:6.006,

segment_001.ts

...

#EXT-X-ENDLIST

Each #EXTINF:6.006 tells the player that segment’s duration. The player sums these to build a timeline. When you seek to 2:30, it calculates which segment contains that timestamp.

Learning milestones:

- Generate valid HLS that plays in VLC → You understand HLS basics

- Master playlist with quality switching → You understand adaptive streaming structure

- Verify segments are keyframe-aligned → You understand why encoding parameters matter

- Calculate which segment contains any timestamp → You understand seeking in chunked streaming

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How does a video player know which 6-second chunk to download next when the video is split into hundreds of pieces?”

This is the fundamental problem HLS solves: breaking a video into small HTTP-fetchable chunks, then providing a manifest (playlist) that tells the player the sequence, duration, and location of each chunk. Understanding M3U8 playlist structure is the key to understanding all modern streaming protocols (HLS, DASH, Smooth Streaming).

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- HLS Protocol & M3U8 Format

- What’s the difference between a master playlist and media playlist?

- Why does HLS use MPEG-TS (.ts) segments instead of MP4?

- Book Reference: RFC 8216 (HLS Specification) - Sections 4 and 8

- Container Formats (MPEG-TS vs MP4)

- How does MPEG-TS allow arbitrary byte-range cutting without breaking?

- What’s a “muxer” and “demuxer” in FFmpeg terminology?

- Book Reference: “Digital Video and HD” by Charles Poynton - Ch. 9

- Seeking in Segmented Streams

- How do you calculate which segment contains timestamp 2:35?

- What happens if segment durations are variable?

- Book Reference: “Streaming Systems” Ch. 2 - Tyler Akidau et al.

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Segmentation Strategy

- Should all segments be exactly 6 seconds, or allow variable duration?

- How do you handle the last segment if video duration doesn’t divide evenly?

- Playlist Generation

- Should you generate master + media playlists in one pass or two?

- How do you compute

#EXT-X-TARGETDURATION(max segment duration)?

- Live vs VOD

- What changes in the M3U8 for a live stream vs video-on-demand?

- How would you update the playlist for a live stream every 6 seconds?

Thinking Exercise

Before writing code, manually create this M3U8:

You have a 30-second video encoded at 720p. You want 6-second segments.

- How many segments will you have?

- Write out the media playlist by hand (segment filenames, #EXTINF tags)

- Now add a 1080p version. Write the master playlist that references both

- What happens if you seek to 20 seconds? Which segment number is that?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “Explain the difference between a master playlist and a media playlist in HLS.”

- “Why does HLS use MPEG-TS segments instead of MP4? What breaks if you use MP4?”

- “How would you implement seeking in an HLS player? What information from the playlist do you need?”

- “A client downloads master.m3u8 and sees two quality options. How does it decide which to start with?”

- “What’s the purpose of #EXT-X-TARGETDURATION, and why must it be accurate?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Use FFmpeg for segmentation

You don’t need to write a video segmenter from scratch. FFmpeg’s -f hls output format does the heavy lifting:

ffmpeg -i input.mp4 -f hls -hls_time 6 -hls_list_size 0 -hls_segment_filename "seg_%03d.ts" output.m3u8

Hint 2: Parse the FFmpeg output FFmpeg generates the media playlist. Your job is to:

- Generate multiple qualities (run FFmpeg multiple times with different resolutions/bitrates)

- Create a master playlist that references each media playlist

- Verify segment alignment (check that all qualities have same number of segments)

Hint 3: Master playlist structure

#EXTM3U

#EXT-X-STREAM-INF:BANDWIDTH=5000000,RESOLUTION=1920x1080

1080p.m3u8

#EXT-X-STREAM-INF:BANDWIDTH=2500000,RESOLUTION=1280x720

720p.m3u8

Hint 4: Verify with VLC The fastest way to test:

python -m http.server 8080

# Open http://localhost:8080/master.m3u8 in VLC

If it plays and you can switch qualities (Tools > Track > Video Track), it works.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter | |——-|——|———| | HLS Protocol Specification | RFC 8216 (free online) | Sections 4, 8 | | Container Formats | “Digital Video and HD” by Charles Poynton | Ch. 9 | | Segmentation & Chunking | “Streaming Systems” by Tyler Akidau et al. | Ch. 2 | | FFmpeg HLS Guide | FFmpeg Official Docs (free online) | HLS Muxer | | HTTP Streaming Overview | “High Performance Browser Networking” by Ilya Grigorik | Ch. 16 |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem 1: “VLC plays the stream but can’t seek”

- Why: You’re missing

#EXT-X-ENDLISTat the end of media playlists (tells player it’s VOD, not live) - Fix: Add

#EXT-X-ENDLISTas the last line of each media playlist - Quick test:

tail -1 output.m3u8should show#EXT-X-ENDLIST

Problem 2: “Master playlist shows multiple qualities but only one plays”

- Why: Paths in master playlist are wrong, or files don’t exist

- Fix: Use relative paths from master.m3u8 location. If master is in

/hls/, media playlists should be/hls/720p.m3u8 - Quick test:

curl http://localhost:8080/720p.m3u8should return the media playlist, not 404

Problem 3: “Segments play but quality switching causes freezes”

- Why: Keyframes aren’t aligned—you encoded each quality separately without matching GOP structure

- Fix: Use same

-gvalue for all qualities (e.g.,-g 48for 2-sec keyframes at 24fps) - Quick test: Count segments in each quality’s playlist—should be identical

Problem 4: “Player downloads all segments immediately instead of one at a time”

- Why: This is actually correct behavior for VOD! Players pre-fetch for smooth playback

- Fix: Not a bug. To see sequential fetching, simulate live stream (update playlist every 6 seconds, don’t include

#EXT-X-ENDLIST) - Quick test: Open DevTools Network tab, watch segment requests happen in order as buffer fills

Project 5: HLS Player from Scratch (No Libraries)

- File: VIDEO_STREAMING_DEEP_DIVE_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: JavaScript

- Alternative Programming Languages: TypeScript, Rust (WebAssembly)

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 4: Expert

- Knowledge Area: Media APIs / Streaming

- Software or Tool: HTML5 Media Source Extensions

- Main Book: “High Performance Browser Networking” by Ilya Grigorik

What you’ll build: A web-based HLS player that parses M3U8 manifests, fetches TS segments, and plays video using the Media Source Extensions API—without using hls.js or any video library.

Why it teaches streaming internals: hls.js and video.js hide all the magic. By building from scratch, you’ll understand exactly how browsers handle streaming: parsing playlists, managing buffers, feeding raw bytes to the decoder, handling seek operations, and dealing with quality switches mid-stream. This is the deepest understanding of streaming possible.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- M3U8 parsing (regex/state machine for playlist format) → maps to protocol parsing

- Media Source Extensions API (SourceBuffer, appendBuffer) → maps to browser media internals

- Buffer management (keeping ~30s ahead of playback) → maps to streaming buffer strategy

- Transmuxing TS to fMP4 (browsers need fMP4, not TS) → maps to container transformation

- Seek implementation (find correct segment, flush buffer, refill) → maps to playback control

Key Concepts:

- Media Source Extensions: W3C MSE Specification - W3C

- M3U8 Parsing: RFC 8216 - IETF

- Transmuxing: “mux.js” source code - Brightcove (open source)

- Buffer Management: “hls.js” architecture docs - video-dev GitHub

Difficulty: Advanced-Expert Time estimate: 2-3 weeks Prerequisites: Strong JavaScript, Projects 3-4 completed

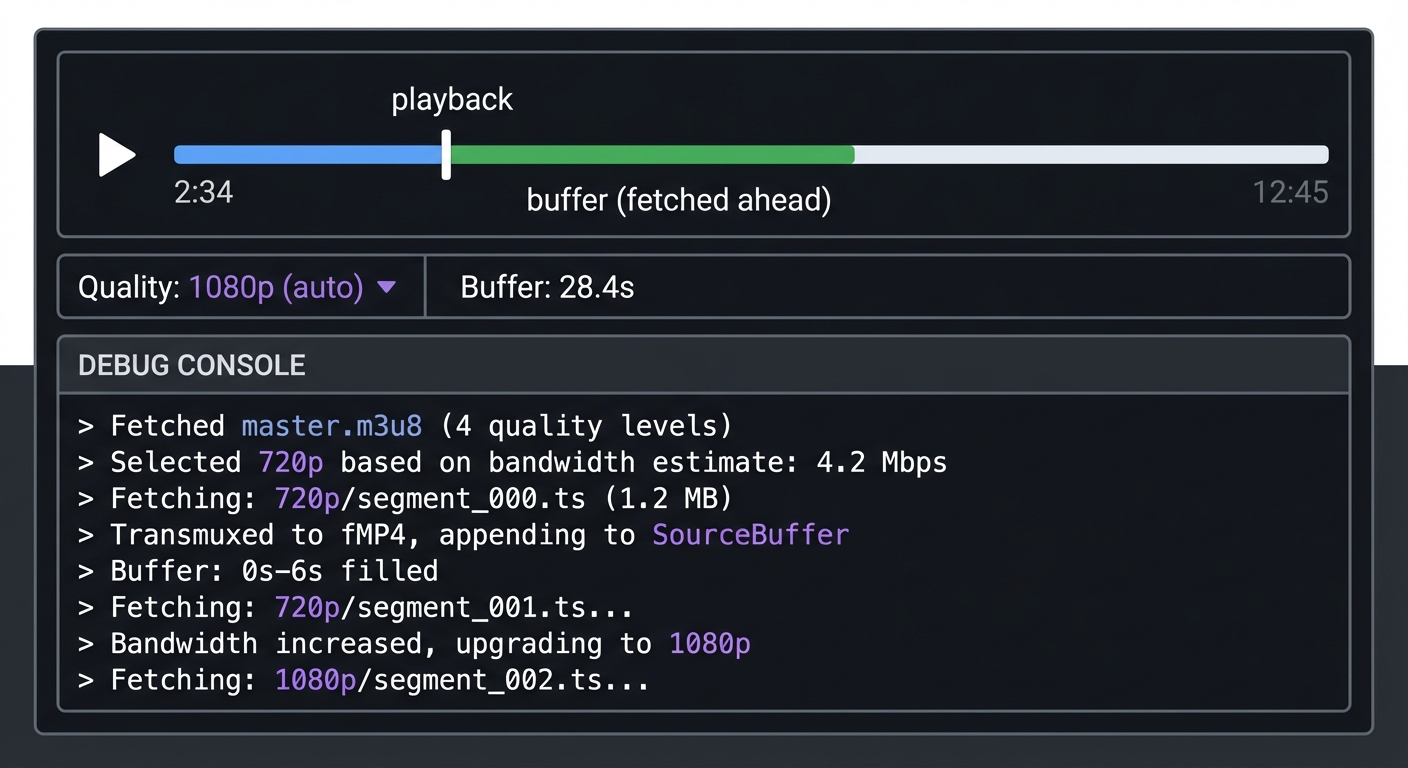

Real world outcome: A web page with your custom player:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ ▶ [==================|========== ] 2:34 │

│ └── playback └── buffer (fetched ahead) │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Quality: 1080p (auto) ▼ Buffer: 28.4s │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Debug Console: │

│ > Fetched master.m3u8 (4 quality levels) │

│ > Selected 720p based on bandwidth estimate: 4.2 Mbps │

│ > Fetching: 720p/segment_000.ts (1.2 MB) │

│ > Transmuxed to fMP4, appending to SourceBuffer │

│ > Buffer: 0s-6s filled │

│ > Fetching: 720p/segment_001.ts... │

│ > Bandwidth increased, upgrading to 1080p │

│ > Fetching: 1080p/segment_002.ts... │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Implementation Hints: The key APIs are:

MediaSource- Create a source for your<video>elementSourceBuffer- Append media data to be decodedfetch()- Get playlist and segment files

The tricky part is that browsers expect fragmented MP4 (fMP4), but HLS uses MPEG-TS (.ts) segments. You’ll need to transmux—convert TS container to fMP4 container without re-encoding the video. Study mux.js source code or implement the container transformation yourself (very educational but adds 1-2 weeks).

const mediaSource = new MediaSource();

video.src = URL.createObjectURL(mediaSource);

mediaSource.addEventListener('sourceopen', () => {

const sourceBuffer = mediaSource.addSourceBuffer('video/mp4; codecs="avc1.64001f"');

// Fetch segment, transmux to fMP4, then:

sourceBuffer.appendBuffer(fmp4Data);

});

Learning milestones:

- Parse M3U8 and log segment URLs → You understand playlist structure

- Fetch segments and append to SourceBuffer → You understand MSE basics

- Implement seek (flush and refetch) → You understand buffer management

- Switch quality mid-stream without glitches → You understand seamless ABR

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How does Netflix seamlessly switch from 1080p to 480p when your Wi-Fi slows down, without pausing or rebuffering?”

This is the magic of HLS and adaptive bitrate streaming: the player downloads chunks sequentially, parses playlists, manages a buffer, and decides quality on-the-fly. Building a player from scratch—without hls.js—forces you to understand Media Source Extensions (MSE), buffer management, and transmuxing (MPEG-TS to fragmented MP4).

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Media Source Extensions (MSE) API

- What’s the difference between

MediaSourceandSourceBuffer? - Why can’t you just set

video.src = "segment_000.ts"? - Book Reference: MDN Web Docs (free online) - Media Source Extensions API

- What’s the difference between

- Container Transmuxing (MPEG-TS to fMP4)

- Why does HLS use MPEG-TS but browsers expect fragmented MP4?

- What’s the difference between transcoding and transmuxing?

- Book Reference: “Digital Video and HD” by Charles Poynton - Ch. 9 (Container Formats)

- Buffer Management & State Machines

- What are the MSE

readyStatevalues and what do they mean? - How do you handle buffer stalls vs intentional pauses?

- Book Reference: “High Performance Browser Networking” Ch. 16 - Ilya Grigorik

- What are the MSE

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Playlist Parsing

- How will you parse M3U8 (regex, line-by-line, or a parser library)?

- Should you handle both master and media playlists in one function?

- Segment Fetching Strategy

- Should you pre-fetch the next segment while the current one plays?

- How much buffer should you maintain ahead of playback position?

- Quality Switching

- Can you switch mid-segment, or only at segment boundaries?

- How do you prevent a “quality thrashing” loop (switching constantly)?

Thinking Exercise

Before writing code, trace this flow on paper:

User clicks play. Your player must:

- Fetch

master.m3u8→ parse quality options - Choose starting quality (how?)

- Fetch that quality’s media playlist (

720p.m3u8) - Parse segment URLs and durations

- Fetch

segment_000.ts, transmux to fMP4, append toSourceBuffer - Fetch

segment_001.tswhilesegment_000plays - User seeks to 2:30. What happens to the buffer? What segments do you fetch?

Draw this as a state machine with 5 states: IDLE, LOADING_MANIFEST, BUFFERING, PLAYING, SEEKING.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “Explain how Media Source Extensions work. What’s the relationship between MediaSource and SourceBuffer?”

- “Why can’t you just set video.src to an MPEG-TS segment URL? What has to happen first?”

- “How would you implement seeking in an HLS player? What state changes occur?”

- “A user seeks forward 30 seconds. Should you flush the entire buffer or keep some?”

- “What’s the difference between transmuxing and transcoding? Which does an HLS player do?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with M3U8 parsing Don’t build the player yet. First, write a function that fetches and parses a master playlist, extracts quality options, then fetches a media playlist and extracts segment URLs and durations.

Hint 2: Use MediaSource API

Create a MediaSource, attach it to a <video> element, then add a SourceBuffer. The SourceBuffer is where you append decoded media data.

const mediaSource = new MediaSource();

video.src = URL.createObjectURL(mediaSource);

mediaSource.addEventListener('sourceopen', () => {

const sourceBuffer = mediaSource.addSourceBuffer('video/mp4; codecs="avc1.64001f"');

// Now fetch and append segments

});

Hint 3: Transmuxing is hard—use a library (or challenge yourself) The browser expects fragmented MP4 (fMP4), but HLS segments are MPEG-TS. You can:

- Use

mux.jslibrary (easiest, good for learning MSE) - Study mux.js source and implement yourself (advanced, 1-2 weeks extra)

- Use

ffmpeg.wasmto convert in-browser (creative but overkill)

Hint 4: Test incrementally

- First, parse M3U8 and log segment URLs to console

- Fetch one segment, log its size

- Transmux one segment, append to SourceBuffer, verify playback

- Fetch and append segments in sequence

- Finally, add seeking and quality switching

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter | |——-|——|———| | Media Source Extensions API | MDN Web Docs (free online) | MSE Guide | | Browser Media Processing | “High Performance Browser Networking” by Ilya Grigorik | Ch. 16 | | Container Formats | “Digital Video and HD” by Charles Poynton | Ch. 9 | | HLS Protocol | RFC 8216 (free online) | Sections 4, 8 | | JavaScript Async Patterns | “JavaScript: The Definitive Guide” by David Flanagan | Ch. 13 |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem 1: “MediaSource throws ‘QuotaExceededError’ when appending segments”

- Why: You’re appending segments faster than the browser can process, or buffer is too large

- Fix: Wait for

sourceBuffer.updating === falsebefore appending next segment - Quick test: Add

sourceBuffer.addEventListener('updateend', () => { /* append next */ })

Problem 2: “Video plays first segment then stops”

- Why: You’re not fetching and appending subsequent segments

- Fix: Use

video.addEventListener('timeupdate')to monitor playback position and fetch next segment when buffer is running low - Quick test: Log

video.buffered.end(0) - video.currentTime(should stay above 6 seconds)

Problem 3: “Seeking causes ‘Failed to execute appendBuffer’ error”

- Why: You didn’t flush the old buffer before appending new segments

- Fix: Call

sourceBuffer.remove(0, sourceBuffer.buffered.end(0))before seeking, then append new segments - Quick test: Add logging around

remove()andappendBuffer()during seek

Problem 4: “MPEG-TS segments won’t play—’codec not supported’ error”

- Why: Browsers don’t support MPEG-TS containers directly via MSE. You must transmux to fMP4

- Fix: Use

mux.jsto convert TS to fMP4 before appending to SourceBuffer - Quick test: Check

MediaSource.isTypeSupported('video/mp2t')→ returnsfalse

Problem 5: “Quality switching works but causes brief playback pause”

- Why: You’re flushing the entire buffer on quality switch, causing rebuffering

- Fix: Only remove buffered data ahead of current playback position, keep already-played buffer

- Quick test: Log buffer ranges before/after switch:

video.buffered.start(0)andend(0)

Project 6: Adaptive Bitrate Algorithm

- File: VIDEO_STREAMING_DEEP_DIVE_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: JavaScript

- Alternative Programming Languages: TypeScript, Python (simulation), Rust

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 2. The “Micro-SaaS / Pro Tool”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Algorithms / Control Systems

- Software or Tool: ABR Algorithm

- Main Book: “Computer Networks” by Andrew Tanenbaum

What you’ll build: Multiple ABR (Adaptive Bitrate) algorithms that decide which quality level to fetch next, based on bandwidth measurements and buffer status. Compare throughput-based, buffer-based, and hybrid approaches.

Why it teaches the “magic” of YouTube quality: Ever notice how YouTube starts fuzzy, gets sharp, and rarely buffers? That’s the ABR algorithm. It’s constantly making decisions: “I have 15 seconds buffered, bandwidth looks good, let me try 1080p for the next chunk.” If bandwidth drops, it switches down before you see a stall. This is the core intelligence of modern streaming.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Bandwidth estimation (segment download time, exponential moving average) → maps to measurement

- Buffer-based selection (more buffer = be aggressive, less = be conservative) → maps to control theory

- Quality oscillation prevention (don’t switch every segment) → maps to stability

- Startup optimization (fast quality ramp-up) → maps to user experience

Key Concepts:

- Throughput-Based ABR: “A Buffer-Based Approach to Rate Adaptation” - Stanford Paper (Te-Yuan Huang)

- BBA Algorithm: “Buffer-Based Rate Selection” - Stanford/Netflix Research

- BOLA Algorithm: “BOLA: Near-Optimal Bitrate Adaptation” - Kevin Spiteri et al.

- MPC-Based ABR: “A Control-Theoretic Approach” - MIT CSAIL

Difficulty: Advanced Time estimate: 1-2 weeks Prerequisites: Project 5 completed or understanding of streaming basics

Real world outcome:

ABR Algorithm Comparison (3-minute video, variable network)

Network profile: [8Mbps → 2Mbps → 6Mbps → 1Mbps → 4Mbps]

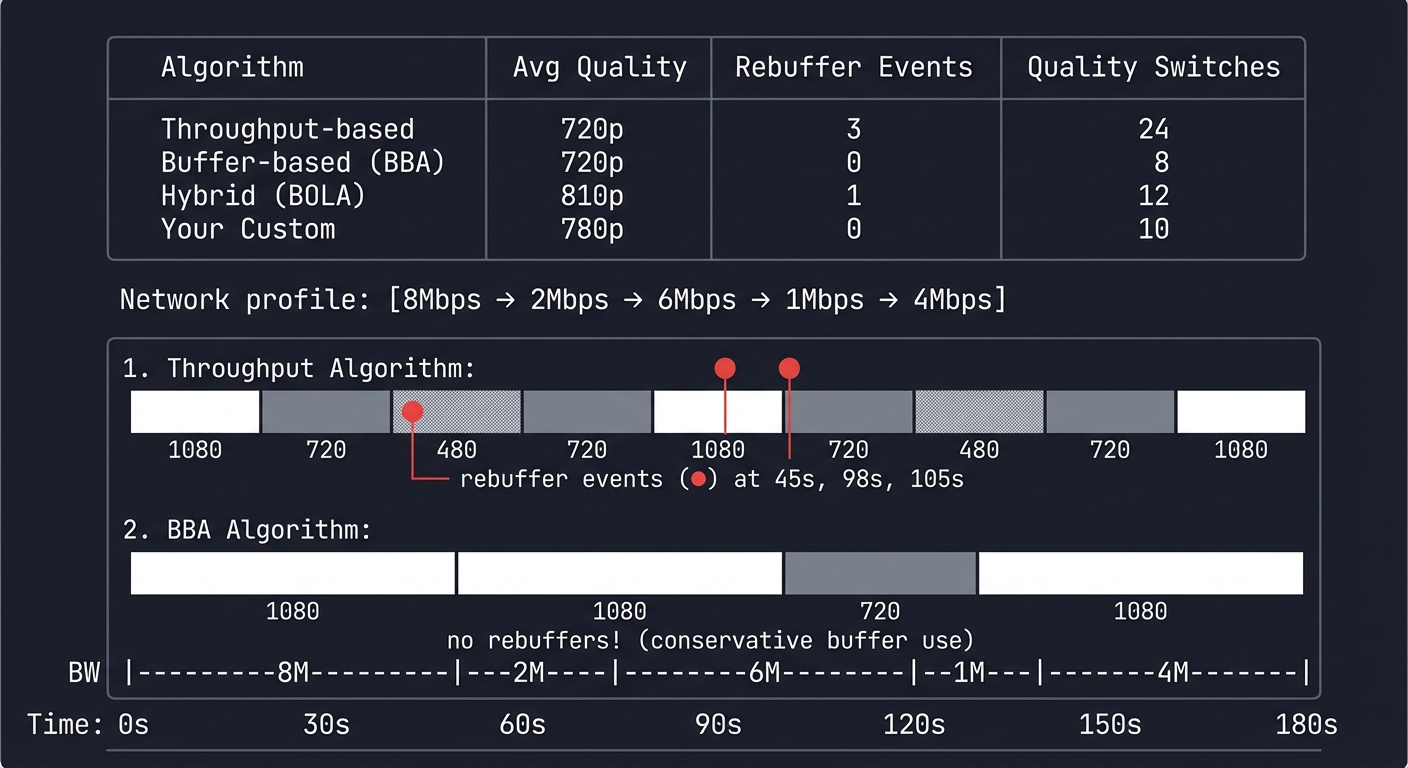

Algorithm | Avg Quality | Rebuffer Events | Quality Switches

-------------------|-------------|-----------------|------------------

Throughput-based | 720p | 3 | 24

Buffer-based (BBA) | 720p | 0 | 8

Hybrid (BOLA) | 810p | 1 | 12

Your Custom | 780p | 0 | 10

Timeline visualization:

Time: 0s 30s 60s 90s 120s 150s 180s

BW: |---8M---|--2M--|---6M---|--1M--|---4M---|

Throughput: ████│▓▓░░▓▓│████│▓▓░░░░│▓▓████│

1080 720 480 720 1080 720 480 720 1080

└── rebuffer events (●) at 45s, 98s, 105s

BBA: ████│████│████│▓▓▓▓│▓▓▓▓│████│████│

1080 1080 720 1080

└── no rebuffers! (conservative buffer use)

Implementation Hints: The simplest ABR: measure how long each segment takes to download, calculate bandwidth, pick the highest quality that fits.

function selectQuality(downloadTimeMs, segmentBytes, bufferLevel, qualities) {

const bandwidthBps = (segmentBytes * 8) / (downloadTimeMs / 1000);

const safeBandwidth = bandwidthBps * 0.8; // 20% safety margin

// Pick highest quality below safe bandwidth

for (let i = qualities.length - 1; i >= 0; i--) {

if (qualities[i].bitrate <= safeBandwidth) return qualities[i];

}

return qualities[0]; // Lowest quality fallback

}

Buffer-based adds: “If buffer > 30s, be aggressive. If buffer < 10s, be very conservative.”

Learning milestones:

- Throughput-based works → You understand bandwidth measurement

- Buffer-based prevents rebuffers → You understand the quality/stall tradeoff

- Oscillation damping works → You understand stability in control systems

- Compare algorithms on same network trace → You understand engineering tradeoffs

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How does a video player predict future network conditions and choose the optimal quality level in real-time, balancing the competing goals of high quality, zero rebuffering, and smooth playback?”

YouTube doesn’t just react to network changes—it anticipates them. The ABR algorithm is a prediction and control system that must make decisions under uncertainty. Too aggressive and you’ll rebuffer. Too conservative and users watch blurry video on a fast connection. This is the essence of adaptive streaming.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Bandwidth Estimation Techniques

- How do you calculate throughput from segment download time? (bytes / seconds = bps)

- Why use exponential moving average instead of raw measurements? (smooths noise, gives recent values more weight)

- What’s the difference between instantaneous bandwidth and sustainable bandwidth? (burst vs steady-state)

- Book Reference: “Computer Networks” Ch. 6.3 - Andrew Tanenbaum (congestion control, bandwidth probing)

- Buffer Management & Control Theory

- Why does buffer level matter more than bandwidth for preventing rebuffering? (buffer is time-to-stall, bandwidth is just prediction)

- How does a buffer-based algorithm work without measuring bandwidth at all? (BBA maps buffer level to quality: high buffer = high quality)

- What’s the difference between buffer-based and throughput-based ABR? (reactive vs predictive)

- Book Reference: “Streaming Systems” Ch. 8 - Tyler Akidau (buffer management, watermarks)

- Quality Oscillation & Stability

- Why is switching quality every segment a bad user experience? (human eye notices changes, visual distraction)

- How do you prevent oscillation without being too slow to adapt? (hysteresis, minimum switch interval)

- What’s the tradeoff between responsiveness and stability? (fast changes vs smooth experience)

- Book Reference: “Feedback Control of Dynamic Systems” Ch. 7 - Franklin (stability analysis, overshoot prevention)

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Measurement Strategy

- How long should you observe network conditions before making a decision? (one segment? five segments? exponential average?)

- What safety margin should you apply to bandwidth estimates? (80%? 90%? depends on risk tolerance)

- How do you handle startup when you have no bandwidth measurements yet? (start low and ramp up, or probe aggressively?)

- Decision Logic

- Should you prioritize quality or rebuffer avoidance? (depends on content type: live sports vs on-demand movie)

- How do you detect when network conditions have truly changed vs temporary fluctuation? (threshold crossing, sustained change)

- When should you switch down preemptively vs waiting for buffer to drain? (proactive vs reactive)

- Algorithm Selection

- When would throughput-based ABR fail? (variable latency, bursty networks, bufferbloat)