Learn Traffic Management: From Sockets to Service Mesh

Goal: Deeply understand how traffic flows through modern infrastructure—from raw TCP packets in a Layer 4 load balancer to complex HTTP routing in a Service Mesh. You will build your own proxies, implement service discovery algorithms, and master the tools (NGINX, Envoy) that power the internet.

Why Traffic Management Matters

In a distributed system, the network is the computer. A single application might span hundreds of servers, containers, or data centers. “Traffic Management” is the art of ensuring that a user’s request (a click) reaches the correct destination (a service) reliably, securely, and quickly.

The Scale of the Problem

Real-world statistics (2025):

- NGINX powers 38.6% of all web servers globally and 60% of reverse proxy servers

- 67.1% of the top 10,000 websites rely on NGINX

- The global service mesh market grew from $1.2B in 2023 to $1.44B in 2025, projected to reach $8.1B by 2032

- Istio holds 21.3% mindshare, Envoy 20.8% in the service mesh market

- Layer 4 load balancers achieve 10-40 Gbps with sub-millisecond latency

- Layer 7 load balancers add 5-20ms latency but enable content-based routing

Historical Context

The concept of load balancing emerged in the 1990s when websites began experiencing traffic that exceeded a single server’s capacity. Early solutions were hardware-based (F5, Citrix). In 2004, Igor Sysoev created NGINX to solve the “C10K problem” (handling 10,000 concurrent connections). By 2012, microservices architecture created new challenges, leading to the rise of service meshes. Lyft open-sourced Envoy in 2016, revolutionizing how modern infrastructure handles traffic.

Without Traffic Management, You Have:

- Downtime: One crashed server takes down the whole app.

- Chaos: Services don’t know where other services live (IP churn).

- Security holes: Every service needs to handle its own SSL and Auth.

- Latency: Requests travel inefficient routes.

- No observability: You can’t debug what you can’t see.

With Traffic Management, You Enable:

- 99.99% uptime (4 minutes of downtime per month)

- Zero-downtime deployments (canary releases, blue-green deployments)

- Geographic distribution (users routed to nearest datacenter)

- Security at the edge (SSL termination, authentication centralized)

- Intelligent routing (A/B testing, feature flags)

By mastering this, you become the architect of availability.

Core Concept Analysis

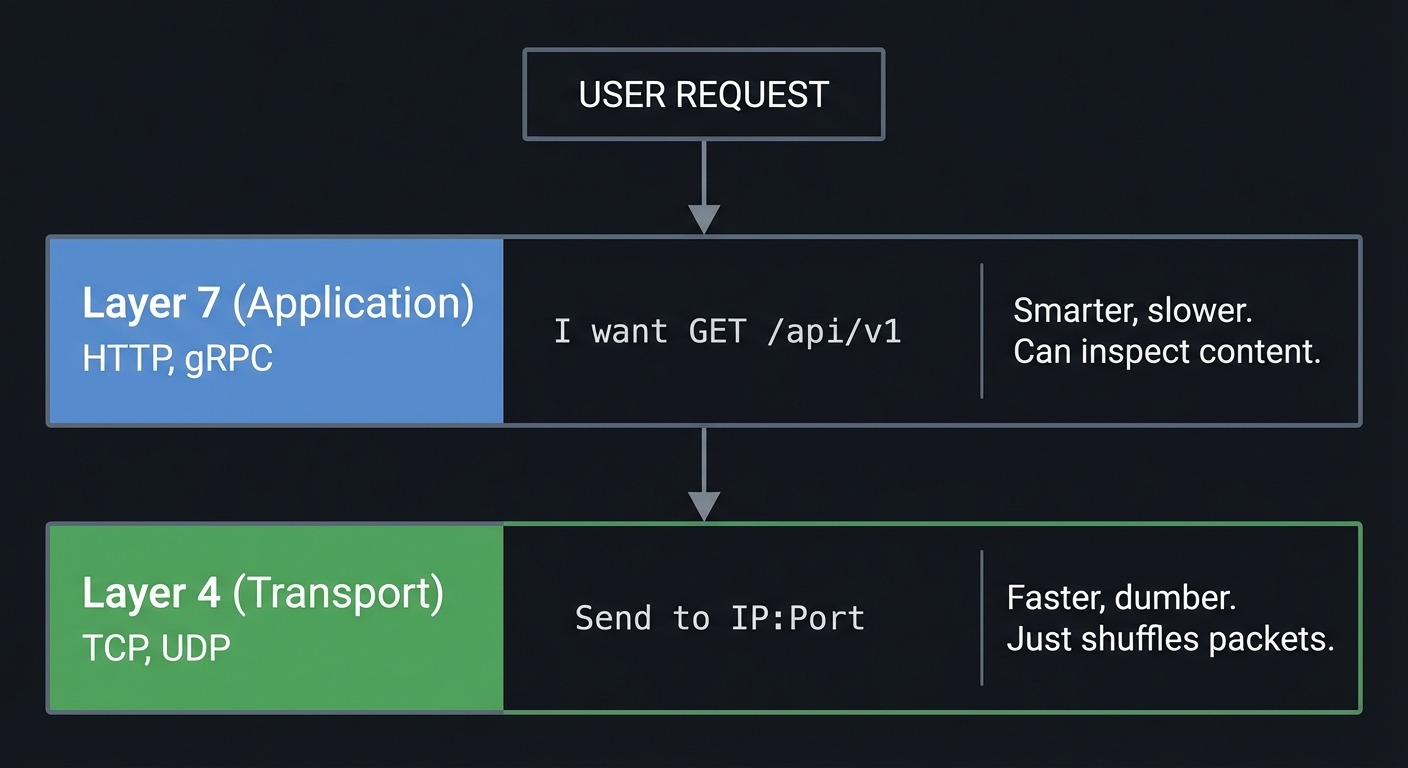

1. The OSI Model & Load Balancing Layers

Traffic can be managed at different layers of the networking stack.

USER REQUEST

│

▼

┌───────────────────────┐

│ Layer 7 (Application) │ HTTP, gRPC

│ "I want GET /api/v1" │ -> Smarter, slower. Can inspect content.

└───────────┬───────────┘

│

┌───────────────────────┐

│ Layer 4 (Transport) │ TCP, UDP

│ "Send to IP:Port" │ -> Faster, dumber. Just shuffles packets.

└───────────────────────┘

2. The Reverse Proxy Pattern

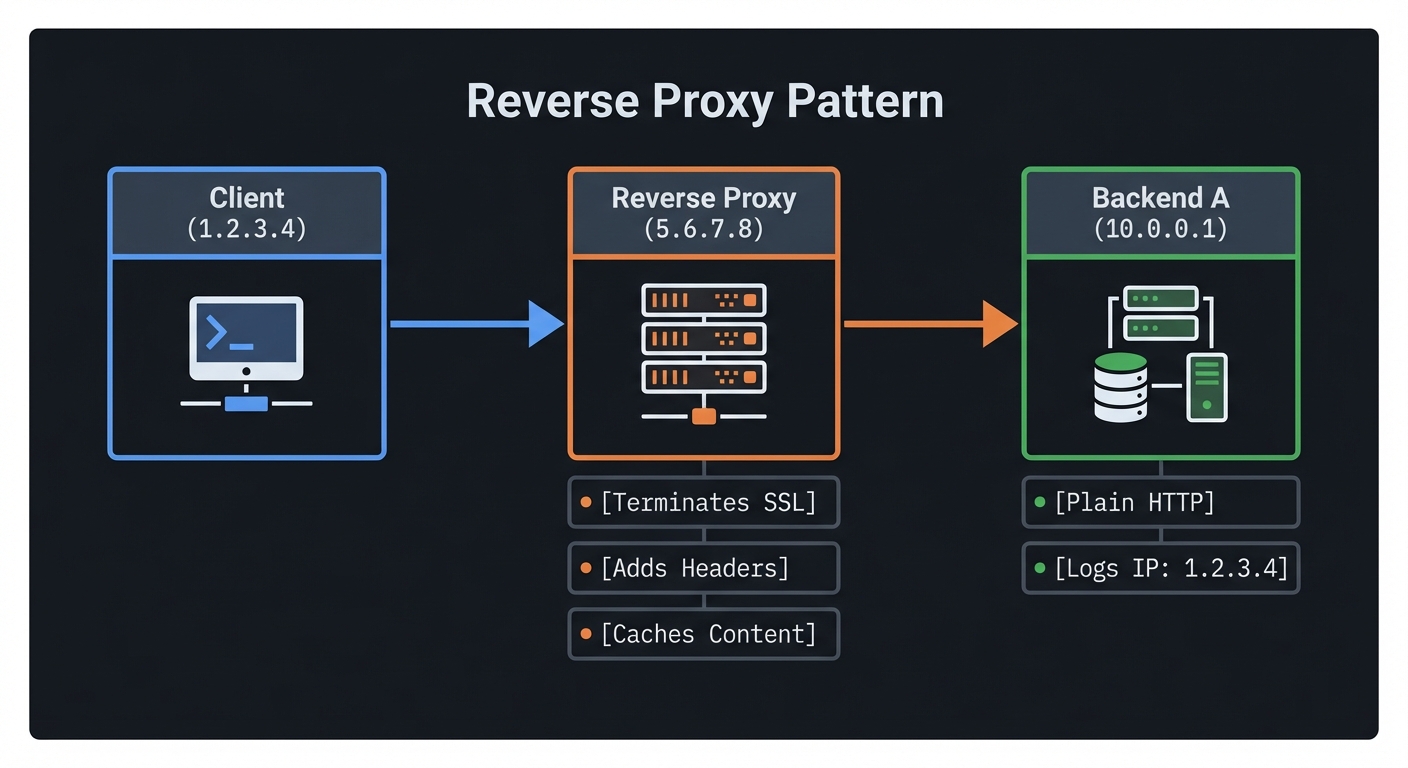

A reverse proxy stands in front of web servers. To the client, the proxy is the server. To the server, the proxy is the client.

Client (1.2.3.4) ───> Reverse Proxy (5.6.7.8) ───> Backend A (10.0.0.1)

[Terminates SSL] [Plain HTTP]

[Adds Headers] [Logs IP: 1.2.3.4]

[Caches Content]

3. Service Discovery: The Phonebook

In modern infrastructure, IPs change constantly (containers die, autoscaling happens). Hardcoding IPs is impossible.

The Solution:

- Registration: Service A starts up → Tells Registry “I am Service A at 10.0.0.5:8080”.

- Discovery: Service B asks Registry “Where is Service A?” → Registry returns list of IPs.

- Health Checking: Registry pings Service A. If it fails, it removes it from the list.

4. The API Gateway vs. Service Mesh

- API Gateway (North-South Traffic): The “Front Door”. Handles external users entering your datacenter. Auth, Rate Limiting, Billing.

- Service Mesh (East-West Traffic): The “Internal Network”. Handles service-to-service calls. Retries, Tracing, Mutual TLS.

Concept Summary Table

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize |

|---|---|

| L4 vs L7 | L4 sees connections (IP:Port); L7 sees requests (Headers, URL). |

| Proxying | The proxy terminates the connection. It creates a new connection to the backend. |

| Load Balancing Algos | Round Robin (turn-taking), Least Connections (fill the empty bucket), Consistent Hashing (sticky). |

| Health Checking | Active (pings) vs. Passive (observing failed errors). |

| Control Plane | The “Brain” that configures the proxies (The “Data Plane”). |

Deep Dive Reading by Concept

Load Balancing & Proxies

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Proxy Internals | “High Performance Browser Networking” by Ilya Grigorik — Ch. 1-4 (Networking basics) |

| NGINX Architecture | “The Architecture of Open Source Applications” (Vol 2) — Chapter: NGINX (Free Online) |

| Envoy Internals | “Envoy Proxy Documentation” — “Life of a Request” (Official Docs) |

Distributed Systems & Discovery

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Service Discovery | “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” by Martin Kleppmann — Ch. 6 (Partitioning/Routing) |

| API Gateways | “Microservices Patterns” by Chris Richardson — Ch. 8 (External API patterns) |

| Reliability | “Site Reliability Engineering” (Google) — Ch. 20 (Load Balancing at the Datacenter) |

Prerequisites & Background Knowledge

Essential Prerequisites (Must Have)

Before diving into traffic management projects, you should have:

- Networking Fundamentals

- Understanding of TCP/IP stack (OSI model layers)

- How DNS resolution works

- What happens when you type a URL in a browser

- Programming Skills

- Proficiency in at least one language: Go, Python, or C

- Understanding of concurrency (threads, goroutines, async/await)

- Experience with sockets and network programming

- Linux/Unix Command Line

- Comfort with terminal navigation and commands

- Basic understanding of process management (

ps,kill,netstat) - Ability to read logs and debug issues

- HTTP Protocol Basics

- Understanding request/response cycle

- Familiarity with headers, methods (GET, POST)

- Status codes (200, 404, 500)

Helpful But Not Required

These topics will be learned through the projects:

- Advanced Go concurrency patterns

- gRPC and Protocol Buffers

- Docker and containerization

- Kubernetes basics

- Redis or other key-value stores

- YAML configuration syntax

Self-Assessment Questions

Can you answer these confidently?

- What are the 7 layers of the OSI model, and what does each do?

- How does a TCP three-way handshake work?

- What is the difference between a socket and a port?

- How does DNS translate a domain name to an IP address?

- What happens when you run

curl https://example.comat the network level? - What is the purpose of the

Hostheader in HTTP/1.1? - How do you create a TCP socket in your preferred language?

- What is the difference between blocking I/O and non-blocking I/O?

If you answered “no” to 3+ questions, spend 1-2 weeks reviewing:

- “Computer Networks” by Tanenbaum — Chapters 1-4

- “TCP/IP Illustrated, Volume 1” by Stevens — Chapters 1-3, 17-18

Development Environment Setup

Required tools:

- Go (1.21+) or Python (3.10+) or C with GCC

- curl or HTTPie for testing

- netcat (

nc) for low-level testing - tcpdump or Wireshark for packet inspection

- Docker (for Projects 5+)

- Text editor or IDE of your choice

Recommended tools:

- jq for JSON parsing in terminal

- ab (Apache Bench) or wrk for load testing

- redis-cli for Project 4

- Postman or Insomnia for API testing

Installation check:

# Verify installations

go version # Should show 1.21+

python3 --version # Should show 3.10+

docker --version # Should show 20.10+

curl --version

nc -h 2>&1 | head -1

Time Investment Expectations

Realistic time estimates per project:

- Projects 1-2: 8-16 hours (one weekend)

- Projects 3-4: 15-25 hours (one full week, evenings)

- Project 5: 6-10 hours (one weekend, mostly configuration)

- Projects 6-7: 20-40 hours (two weeks)

Total journey: 10-14 weeks at 10 hours/week

Important Reality Check

This learning path is challenging. You will:

- Get stuck debugging obscure network issues

- Deal with concurrency bugs that appear randomly

- Read RFCs and protocol specifications

- Rewrite code multiple times as you understand concepts better

But you will emerge with:

- Deep understanding of how the internet actually works

- Ability to architect high-availability systems

- Skills that are in high demand (DevOps, SRE, Platform Engineering)

- Confidence to read NGINX/Envoy source code

Signs you’re ready:

- You’ve built at least one web application (any framework)

- You’re comfortable reading technical documentation

- You enjoy understanding “how things work” beneath abstractions

- You’re willing to spend hours debugging a single network issue

Quick Start Guide (For Overwhelmed Learners)

Feeling overwhelmed? Start here—your first 48 hours:

Day 1: Understand the Basics (4 hours)

Morning (2 hours):

- Read “Why Traffic Management Matters” and “Core Concept Analysis” sections above

- Watch: “Life of a Request” (NGINX or Envoy talk, ~30min)

- Experiment with

curl:curl -v https://google.com # See the HTTP exchange curl -x localhost:8080 https://google.com # Try using a proxy (will fail, but shows concept)

Afternoon (2 hours):

- Install a local NGINX:

# macOS brew install nginx # Linux sudo apt install nginx - Configure a simple reverse proxy:

server { listen 8080; location / { proxy_pass http://httpbin.org; } } - Test it:

curl localhost:8080/get - Read the NGINX logs to see what happened

Day 2: Build Something Tiny (4 hours)

Goal: Build a “Hello World” TCP proxy in 50 lines of code

Using Python:

# Save as mini_proxy.py

import socket

import threading

def handle_client(client_sock):

# Connect to real server

server_sock = socket.socket()

server_sock.connect(('httpbin.org', 80))

# Forward client -> server

request = client_sock.recv(4096)

server_sock.send(request)

# Forward server -> client

response = server_sock.recv(4096)

client_sock.send(response)

client_sock.close()

server_sock.close()

# Listen for connections

server = socket.socket()

server.bind(('0.0.0.0', 9000))

server.listen(5)

while True:

client, addr = server.accept()

threading.Thread(target=handle_client, args=(client,)).start()

Test it:

python mini_proxy.py &

curl -H "Host: httpbin.org" localhost:9000/get

What you just did: You built a Layer 4 proxy! It doesn’t understand HTTP, it just shuffles bytes.

Next Steps After 48 Hours

If you’re excited: Jump into Project 1 (The Packet Shuffler) and make it production-quality.

If you’re confused: Re-read the “Core Concept Analysis” section and the prerequisite books.

If you’re intrigued but intimidated: Start with Project 2 (Header Inspector) instead—it uses higher-level libraries.

Recommended Learning Paths

Different backgrounds require different approaches. Choose your path:

Path A: For Backend Developers (Coming from Web Frameworks)

You know: Django, Rails, Express, Spring Boot You want: To understand what happens below the framework

Recommended order:

- Start with Project 2 (Header Inspector) — familiar HTTP territory

- Move to Project 4 (API Gateway) — extends your web knowledge

- Then Project 1 (Packet Shuffler) — go deeper into TCP

- Then Project 3 (Service Registry) — dynamic infrastructure

- Finally Projects 5-7 — industry tools and architectures

Why this works: You start in familiar territory (HTTP) and gradually descend into lower-level networking.

Path B: For Systems Programmers (Coming from C/C++/Rust)

You know: Pointers, memory management, systems programming You want: To apply low-level skills to distributed systems

Recommended order:

- Start with Project 1 (Packet Shuffler) — right in your wheelhouse

- Then Project 2 (Header Inspector) — understand protocols

- Then Project 6 (Control Plane) — complex architecture

- Then Project 7 (Geo-DNS) — protocol implementation

- Finally Projects 3-5 — distributed systems patterns

Why this works: You leverage your systems knowledge first, then learn distributed patterns.

Path C: For DevOps/SRE Engineers (Coming from Operations)

You know: Kubernetes, Docker, CI/CD, cloud platforms You want: To understand the tools you’re configuring

Recommended order:

- Start with Project 5 (Envoy Sidecar) — tool you recognize

- Then Project 3 (Service Registry) — service discovery

- Then Project 4 (API Gateway) — production patterns

- Then Project 2 (Header Inspector) — understand internals

- Finally Projects 1, 6-7 — deep dives

Why this works: You start with familiar tools and work backward to understand their internals.

Path D: For Complete Beginners (Strong CS Fundamentals)

You know: Data structures, algorithms, basic networking You want: To learn modern infrastructure from scratch

Recommended order:

- Week 1-2: Read prerequisite books (TCP/IP Illustrated, Ch. 1-3)

- Week 3: Complete the “Quick Start Guide” above

- Week 4-5: Project 1 (Packet Shuffler)

- Week 6-7: Project 2 (Header Inspector)

- Week 8-9: Project 3 (Service Registry)

- Week 10-11: Project 4 (API Gateway)

- Week 12-13: Project 5 (Envoy Sidecar)

- Week 14-16: Projects 6-7 (Advanced topics)

Why this works: Sequential progression from fundamentals to advanced architecture.

Project 1: The Packet Shuffler (Layer 4 TCP Load Balancer)

- File: TRAFFIC_MANAGEMENT_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: Go

- Alternative Programming Languages: C, Rust, Python

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 4. The “Open Core” Infrastructure

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Networking / Sockets

- Software or Tool:

netpackage (Go) orsocket(C/Python) - Main Book: “TCP/IP Illustrated” by W. Richard Stevens

What you’ll build: A TCP load balancer that listens on a specific port, accepts connections, and forwards the raw bytes to one of multiple backend servers using a Round-Robin algorithm.

Why it teaches Traffic Management: This removes the “magic” of HTTP. You aren’t routing requests; you are piping bytes. You will understand that at L4, the balancer doesn’t know what data is passing through (it could be HTTP, MySQL, or SSH)—it just ensures the pipe connects to an available destination.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Connection Splice: How to copy bytes from Client→Backend and Backend→Client simultaneously without blocking.

- Concurrency: Handling 100 simultaneous connections (Goroutines or AsyncIO).

- Backend Health: What happens if you try to dial a backend that is down?

Key Concepts:

- TCP Handshake: RFC 793

- Network Address Translation (NAT): Why the backend sees the Proxy’s IP, not the Client’s.

- Multiplexing: Handling multiple sockets in one process.

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: Weekend Prerequisites: Basic socket programming understanding.

Real World Outcome

You’ll start 3 simple web servers (backends) and 1 load balancer. You will hit the load balancer with curl 10 times and see the responses rotate 1-2-3-1-2-3.

Example Output:

# Terminals 1, 2, 3: Start Backends

$ python3 -m http.server 8001

$ python3 -m http.server 8002

$ python3 -m http.server 8003

# Terminal 4: Start Your Balancer

$ ./packet_shuffler --port 9000 --backends 8001,8002,8003

[INFO] Listening on :9000

[INFO] New connection from 127.0.0.1:54321 -> Forwarding to :8001

[INFO] New connection from 127.0.0.1:54322 -> Forwarding to :8002

# Terminal 5: Test

$ curl localhost:9000

Server 8001

$ curl localhost:9000

Server 8002

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How does a load balancer ‘move’ a connection without interrupting the stream?”

It doesn’t “move” it. It acts as a man-in-the-middle, maintaining two connections: one to the client, one to the server, and blindly copying data between them.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- TCP Connection Lifecycle

- What happens during the three-way handshake (SYN, SYN-ACK, ACK)?

- How does the four-way termination work (FIN, ACK, FIN, ACK)?

- What is a “half-open” connection?

- Book Reference: “TCP/IP Illustrated, Volume 1” by W. Richard Stevens — Ch. 18 (TCP Connection Management)

- Socket Programming

- What is the difference between

listen()andaccept()? - Why do you need

SO_REUSEADDR? - What is a socket backlog?

- Book Reference: “UNIX Network Programming, Volume 1” by Stevens — Ch. 4 (Elementary TCP Sockets)

- What is the difference between

- Bidirectional Data Flow

- How do you read from two sockets simultaneously without blocking?

- What is

select(),poll(), orepoll()? - How do goroutines (Go) or async/await (Python) help?

- Book Reference: “The Linux Programming Interface” by Michael Kerrisk — Ch. 63 (I/O Multiplexing)

- Load Balancing Algorithms

- How does Round-Robin work?

- What is the difference between stateless and stateful balancing?

- Why doesn’t Round-Robin consider server load?

- Book Reference: “Site Reliability Engineering” (Google) — Ch. 20 (Load Balancing at the Datacenter)

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Connection Handling

- Will you spawn a new thread/goroutine per connection, or use async I/O?

- How will you copy data from client→backend and backend→client concurrently?

- What happens if the client closes the connection mid-transfer?

- Backend Selection

- Where will you store the list of backends (array, config file)?

- How will you implement Round-Robin (counter, iterator)?

- What happens if all backends are down?

- Error Handling

- What if

dial()to a backend fails (connection refused)? - Should you remove the backend from the pool or retry?

- How do you handle partial writes (not all bytes sent)?

- What if

- Resource Management

- Will you leak file descriptors if you don’t close sockets?

- How do you gracefully shut down (wait for active connections)?

- Should you set read/write timeouts to prevent hanging?

Thinking Exercise

Trace a Single Connection

Before coding, trace this scenario step-by-step on paper:

Setup:

- Load balancer listening on

:9000 - Three backends:

:8001,:8002,:8003 - Counter starts at 0

Client action:

curl localhost:9000

Questions while tracing:

- Which backend gets chosen first (Round-Robin starts at index 0)?

- How many sockets are involved? (Client→LB, LB→Backend = 2 sockets)

- What happens if backend

:8001sends a 1MB response—does the LB buffer it or stream it? - If you run

curl localhost:9000three more times, what is the backend selection pattern? - What system calls does the LB make? (

accept(),connect(),read(),write(),close())

Draw the flow:

Client ──TCP handshake──> LB (port 9000)

│

└──TCP handshake──> Backend 8001

Client ──HTTP GET /──────> LB

│

└──HTTP GET /──────> Backend 8001

Client <──200 OK──────────LB

│

<──200 OK───────────Backend 8001

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “What is the difference between Layer 4 and Layer 7 load balancing?”

- L4 operates on IP/Port (transport layer), L7 operates on HTTP headers/URLs (application layer)

- L4 is faster (just forwards packets), L7 is smarter (can route based on content)

- “How would you handle a backend server failing mid-request?”

- Detect the failure (connection reset, timeout)

- Return an error to the client (502 Bad Gateway)

- Mark the backend as unhealthy and retry on another backend (if idempotent)

- “Why doesn’t a Layer 4 load balancer see the original client IP?”

- Because it creates a new connection to the backend (proxy mode)

- The backend sees the LB’s IP as the source

- Layer 7 solves this with

X-Forwarded-Forheader

- “How do you prevent one slow backend from affecting all clients?”

- Set connection/read timeouts

- Use health checks to remove slow backends

- Implement circuit breaking (stop sending traffic after N failures)

- “What happens if your load balancer crashes?”

- All active connections drop (single point of failure)

- Solution: Run multiple LBs with DNS round-robin or use a VIP (Virtual IP) with failover

- “How does a load balancer handle long-lived connections (WebSockets, gRPC)?”

- L4 keeps the connection open as long as both sides are alive

- The challenge: connections stick to one backend (can cause imbalance)

- Solution: Connection-based balancing instead of request-based

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Starting Point

Think of your load balancer as having two jobs:

- Accept Loop: Continuously accept new client connections

- Proxy Loop: For each connection, shuttle bytes between client and backend

Start by writing the accept loop first. Get it to print “New connection from X” before worrying about backends.

Hint 2: Next Level

For the bidirectional copy, you need to run two operations concurrently:

- Read from client → Write to backend

- Read from backend → Write to client

If either side closes, you must close both sockets. In Go, use two goroutines. In Python, use asyncio or threads.

Hint 3: Technical Details

Pseudocode for the proxy function:

func proxyConnection(clientConn, backendConn net.Conn) {

// Close both when done

defer clientConn.Close()

defer backendConn.Close()

// Spawn goroutine for client→backend

go io.Copy(backendConn, clientConn)

// Main goroutine handles backend→client

io.Copy(clientConn, backendConn)

// When io.Copy returns (EOF or error), both sides close

}

For Round-Robin, use a simple counter:

backends := []string{":8001", ":8002", ":8003"}

counter := 0

// Each new connection:

chosen := backends[counter % len(backends)]

counter++

Hint 4: Tools/Debugging

Test your balancer under load:

# Send 100 requests

for i in {1..100}; do curl -s localhost:9000 & done

wait

# Check distribution

# You should see ~33 requests per backend

Debug connection issues with netstat:

# See active connections to your balancer

netstat -an | grep 9000

# See connections from balancer to backends

netstat -an | grep ESTABLISHED

Use tcpdump to see packets:

sudo tcpdump -i lo -A port 9000

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| TCP connection lifecycle | “TCP/IP Illustrated, Volume 1” by W. Richard Stevens | Ch. 18 (Connection Management) |

| Socket API basics | “UNIX Network Programming, Volume 1” by W. Richard Stevens | Ch. 4 (Elementary TCP Sockets) |

| Concurrent I/O | “The Linux Programming Interface” by Michael Kerrisk | Ch. 63 (I/O Multiplexing) |

| Load balancing theory | “Site Reliability Engineering” (Google, free online) | Ch. 20 (Load Balancing at the Datacenter) |

| Go concurrency | “Concurrency in Go” by Katherine Cox-Buday | Ch. 3 (Go’s Concurrency Building Blocks) |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem 1: “Connection refused when dialing backend”

- Why: Backend server isn’t running or isn’t listening on the expected port

- Fix: Start your backend servers first:

python3 -m http.server 8001 - Quick test:

curl localhost:8001should work directly before testing the balancer

Problem 2: “Balancer hangs after first request”

- Why: You’re blocking on

read()without using concurrency - Fix: Ensure you’re copying client→backend and backend→client concurrently (goroutines/threads)

- Quick test: Add timeout:

conn.SetReadDeadline(time.Now().Add(5 * time.Second))

Problem 3: “All requests go to the same backend”

- Why: Counter isn’t incrementing or you’re using a shared counter without synchronization

- Fix:

// Use atomic increment (Go) import "sync/atomic" var counter uint64 chosen := backends[atomic.AddUint64(&counter, 1) % len(backends)] - Quick test: Print which backend is chosen for each request

Problem 4: “File descriptor limit reached”

- Why: You’re accepting connections but not closing sockets

- Fix: Always use

defer conn.Close()or ensure close in all code paths - Quick test:

lsof -p <pid>shows open file descriptors

Problem 5: “Responses are corrupted or incomplete”

- Why: You’re not copying all bytes (only one

read()call) - Fix: Use

io.Copy()(Go) or loop until EOF - Quick test: Test with large responses:

curl localhost:9000/large_file

Problem 6: “Load balancer becomes slow under high traffic”

- Why: Creating goroutines/threads has overhead; need connection pooling

- Fix: For production, use a worker pool pattern (limit concurrent connections)

- Quick test: Benchmark with

ab -n 10000 -c 100 http://localhost:9000/

Learning Milestones

- First Milestone: Basic Forwarding Works

- You can send one HTTP request through the balancer and get a response

- You understand that the balancer is “invisible” to both client and server

- You’ve seen TCP connections in

netstat

- Second Milestone: Round-Robin Distribution

- 100 requests are distributed evenly across backends

- You understand that L4 balancing is stateless (each connection is independent)

- You’ve debugged at least one concurrency issue

- Final Milestone: Production-Ready Features

- Graceful shutdown (wait for active connections to finish)

- Connection timeouts (prevent hanging)

- Basic health checks (skip backends that are down)

- You can explain why Layer 4 is faster than Layer 7

Project 2: The Header Inspector (Layer 7 HTTP Proxy)

- File: TRAFFIC_MANAGEMENT_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: Go or Python

- Alternative Programming Languages: Node.js, Rust

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 3. Service & Support

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: HTTP Protocol / Parsing

- Software or Tool: Standard Libraries

- Main Book: “High Performance Browser Networking” by Ilya Grigorik

What you’ll build: A reverse proxy that parses incoming HTTP requests. It will route traffic based on the URL path (/api goes to Server A, /static goes to Server B) and inject the X-Forwarded-For header so backends know the real client IP.

Why it teaches Traffic Management: This moves you up the stack. Now you are reading the content. You’ll see the cost of parsing text protocols vs. raw TCP. You’ll understand why L7 is smarter but slower than L4.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- HTTP Parsing: Reading the socket until

\r\n\r\nto find headers. - Header Modification: Adding

X-Forwarded-Forwithout corrupting the request. - Routing Logic: Implementing a matching algorithm for paths.

Key Concepts:

- HTTP Message Format: RFC 7230

- X-Forwarded-For: The standard for tracking original IPs.

- Host Header: How one IP serves multiple domains.

Real World Outcome

You will have a proxy that sends requests to different servers based on the URL.

Example Output:

$ ./header_inspector --config routes.json

# Test API route

$ curl localhost:8080/api/users

< Forwarded to Backend A (10.0.0.1) >

{"users": []}

# Test Static route

$ curl localhost:8080/static/logo.png

< Forwarded to Backend B (10.0.0.2) >

(binary image data)

Concepts You Must Understand First (Project 2)

Stop and research these before coding:

- HTTP Message Format

- What is the structure of an HTTP request? (Request line, headers, body)

- How do you detect the end of headers? (

\r\n\r\n) - What is chunked transfer encoding?

- Book Reference: “High Performance Browser Networking” by Ilya Grigorik — Ch. 9 (Brief History of HTTP)

- URL Routing and Pattern Matching

- How do you match

/api/*vs./api/usersvs./static/*.jpg? - Should you use exact match, prefix match, or regex?

- What is the order of precedence (most specific first)?

- Book Reference: “Microservices Patterns” by Chris Richardson — Ch. 8 (External API Patterns)

- How do you match

- X-Forwarded-For Header

- Why does the backend need to know the original client IP?

- What if the request already has

X-Forwarded-For(chained proxies)? - How do you prevent spoofing (trusting client-provided headers)?

- Book Reference: “Site Reliability Engineering” (Google) — Ch. 20 (Load Balancing)

Questions to Guide Your Design (Project 2)

- Parsing Strategy

- Will you use built-in HTTP libraries (

net/httpin Go,http.serverin Python) or parse manually? - If parsing manually, how will you handle malformed requests?

- How do you handle HTTP/1.1 persistent connections (

Connection: keep-alive)?

- Will you use built-in HTTP libraries (

- Routing Configuration

- Will routes be hardcoded, in a JSON file, or in a DSL?

- Example config format:

{ "/api": "http://backend-a:8001", "/static": "http://backend-b:8002" } - Should you support wildcards or regex patterns?

- Header Manipulation

- Besides

X-Forwarded-For, what other headers might you add? (X-Real-IP,X-Forwarded-Proto) - Should you remove hop-by-hop headers (

Connection,Keep-Alive,Proxy-Authorization)?

- Besides

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask (Project 2)

- “Why is Layer 7 load balancing slower than Layer 4?”

- L7 must parse the entire HTTP request (CPU-intensive)

- L7 terminates the TCP connection (two separate connections)

- L4 just forwards packets without inspecting content

- “How does a reverse proxy differ from a forward proxy?”

- Reverse proxy sits in front of servers (hides servers from clients)

- Forward proxy sits in front of clients (hides clients from servers, e.g., corporate proxy)

- “What is the Host header used for?”

- Allows one IP address to host multiple domains (virtual hosting)

- Example:

nginxroutes based onHost: example.comvsHost: blog.example.com

- “How would you implement sticky sessions (session affinity)?”

- Hash the client IP or session cookie to always route to the same backend

- Trade-off: breaks even distribution but preserves session state

- “What happens if you modify a header incorrectly?”

- Could break HTTP parsing (e.g., missing

\r\n) - Could cause security issues (header injection attacks)

- Could break HTTP parsing (e.g., missing

Hints in Layers (Project 2)

Hint 1: Starting Point

Use the built-in HTTP library to avoid parsing manually. In Go:

http.HandleFunc("/", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

// Determine backend based on r.URL.Path

backend := routeRequest(r.URL.Path)

// Modify headers

r.Header.Set("X-Forwarded-For", r.RemoteAddr)

// Forward to backend...

})

Hint 2: Forwarding the Request

You can’t just “pass through” the request object. You need to create a new HTTP request to the backend:

backendURL := "http://backend:8001" + r.URL.Path

proxyReq, _ := http.NewRequest(r.Method, backendURL, r.Body)

proxyReq.Header = r.Header

Hint 3: Copying the Response

After getting the backend’s response, copy status, headers, and body back to the client:

client := &http.Client{}

resp, err := client.Do(proxyReq)

// Copy response to original requester

for k, v := range resp.Header {

w.Header()[k] = v

}

w.WriteHeader(resp.StatusCode)

io.Copy(w, resp.Body)

Hint 4: Routing Logic

Simple prefix matching:

func routeRequest(path string) string {

if strings.HasPrefix(path, "/api") {

return "http://backend-a:8001"

} else if strings.HasPrefix(path, "/static") {

return "http://backend-b:8002"

}

return "http://default:8000"

}

Common Pitfalls & Debugging (Project 2)

Problem 1: “Request headers are missing in backend”

- Why: You forgot to copy headers from original request to proxy request

- Fix:

proxyReq.Header = r.Header.Clone()

Problem 2: “Backend returns 400 Bad Request”

- Why: You modified the

Hostheader incorrectly - Fix: Set

Hostto the backend’s hostname:proxyReq.Host = backendURL.Host

Problem 3: “Large file uploads hang or fail”

- Why: You’re buffering the entire body in memory

- Fix: Stream the body:

io.Copy(proxyReq.Body, r.Body)

Problem 4: “Client sees wrong status code”

- Why: You called

w.Write()beforew.WriteHeader() - Fix: Always set status code first:

w.WriteHeader(resp.StatusCode)

Learning Milestones (Project 2)

- First Milestone: You can route

/apito one backend and/staticto another - Second Milestone: You can inspect request headers and inject

X-Forwarded-For - Final Milestone: You handle errors gracefully (502 Bad Gateway when backend is down)

Project 3: The Heartbeat Registry (Service Discovery)

- File: TRAFFIC_MANAGEMENT_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: Go or Python

- Alternative Programming Languages: Java, C#

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 4. Open Core Infrastructure

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Distributed Systems / Consensus

- Software or Tool: HTTP API + In-Memory Store

- Main Book: “Designing Data-Intensive Applications”

What you’ll build: A Service Registry (like a mini-Consul). Services will “register” themselves via an HTTP POST. Your registry will periodically “ping” them (Health Check). If they don’t respond, they are removed. You will then modify your Project 2 Proxy to query this registry instead of using a hardcoded config.

Why it teaches Traffic Management: Hardcoded IPs are the enemy of scale. This project teaches you dynamic infrastructure. You’ll deal with “Split Brain” (what if the registry thinks a service is down, but it’s just a network blip?) and eventual consistency.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- TTL (Time to Live): Expiring services that stop sending heartbeats.

- Concurrency: Reading the service list while simultaneously updating it (Reader-Writer Locks).

- Client-Side Balancing: Modifying the proxy to fetch the list and pick an IP.

Key Concepts:

- Health Checks: TCP Connect vs HTTP 200 OK.

- Service Registration Pattern: Self-registration vs Sidecar registration.

- Eventual Consistency: Why the proxy might have a stale list for a few seconds.

Real World Outcome

- Start the Registry.

- Start 5 backend services on random ports; they auto-register.

- Kill one backend.

- Watch the Registry logs remove it.

- Watch the Proxy stop sending traffic to the dead port automatically.

Example Output:

[Registry] Service 'api-v1' registered at 127.0.0.1:4501

[Registry] Service 'api-v1' registered at 127.0.0.1:4502

[Registry] Health Check failed for 127.0.0.1:4501 (Connection Refused)

[Registry] Removing 127.0.0.1:4501 from pool.

Concepts You Must Understand First (Project 3)

- Time-To-Live (TTL) and Expiration

- How do you track when a service last sent a heartbeat?

- Should you store timestamps or use expiring keys?

- What is the trade-off between TTL duration and detection speed?

- Book Reference: “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” by Martin Kleppmann — Ch. 8 (Distributed System Troubles)

- Eventual Consistency

- Why might different clients see different service lists for a few seconds?

- What is the CAP theorem (Consistency, Availability, Partition Tolerance)?

- How does this compare to Consul, etcd, or ZooKeeper?

- Book Reference: “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” — Ch. 9 (Consistency and Consensus)

- Concurrency and Locking

- How do you safely update the service list while serving reads?

- What is a read-write lock (

sync.RWMutexin Go)? - Why is a mutex needed even in single-threaded async code (race conditions)?

- Book Reference: “Concurrency in Go” by Katherine Cox-Buday — Ch. 2 (Modeling Your Code)

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask (Project 3)

- “How do you handle the split-brain problem in service discovery?”

- Split-brain: Registry thinks service is down, but it’s just a network partition

- Solution: Use consensus algorithms (Raft, Paxos) or accept eventual consistency

- “What happens if the registry itself crashes?”

- All services lose discovery capability (single point of failure)

- Solution: Run multiple registry nodes with data replication (like Consul cluster)

- “Why not just use DNS for service discovery?”

- DNS has high TTL (caching delays updates)

- DNS doesn’t do health checks (returns dead IPs)

- DNS is designed for infrequent changes, not dynamic infrastructure

- “How would you implement client-side load balancing?”

- Client queries registry, gets list of IPs

- Client picks one using Round-Robin or Random

- Trade-off: registry doesn’t control distribution, but clients avoid extra hop

Hints in Layers (Project 3)

Hint 1: Data Structure

Store services in a map with timestamps:

type ServiceRegistry struct {

mu sync.RWMutex

services map[string][]Instance

}

type Instance struct {

IP string

Port int

LastHB time.Time

}

Hint 2: Registration Endpoint

// POST /register

// Body: {"service": "api-v1", "ip": "127.0.0.1", "port": 8001}

func register(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

var req RegisterRequest

json.NewDecoder(r.Body).Decode(&req)

registry.mu.Lock()

defer registry.mu.Unlock()

registry.services[req.Service] = append(

registry.services[req.Service],

Instance{IP: req.IP, Port: req.Port, LastHB: time.Now()},

)

}

Hint 3: Background Health Checker

Run a goroutine that periodically removes stale services:

func (r *ServiceRegistry) cleanupLoop() {

ticker := time.NewTicker(5 * time.Second)

for range ticker.C {

r.mu.Lock()

for svc, instances := range r.services {

// Remove instances with LastHB > 30 seconds ago

alive := []Instance{}

for _, inst := range instances {

if time.Since(inst.LastHB) < 30*time.Second {

alive = append(alive, inst)

}

}

r.services[svc] = alive

}

r.mu.Unlock()

}

}

Common Pitfalls & Debugging (Project 3)

Problem 1: “Services are removed immediately after registration”

- Why: Health check runs before service can send heartbeat

- Fix: Use passive health checks (only remove after missed heartbeats, not failed TCP connects)

Problem 2: “Race condition: panic on concurrent map access”

- Why: Forgot to lock mutex when reading/writing services

- Fix: Always use

registry.mu.RLock()for reads,registry.mu.Lock()for writes

Problem 3: “Clients get stale service lists”

- Why: This is expected! Eventual consistency means short delays

- Fix: Document the behavior; clients should retry failed requests

Learning Milestones (Project 3)

- First Milestone: Services can register and appear in the list

- Second Milestone: Services disappear after timeout (TTL expiration)

- Final Milestone: Your Project 2 proxy queries the registry instead of using a config file

Project 4: The Intelligent Gatekeeper (API Gateway Features)

- File: TRAFFIC_MANAGEMENT_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: Go (extending Project 2/3)

- Alternative Programming Languages: Lua (inside NGINX), Python

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 4. Open Core Infrastructure

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: API Security / Rate Limiting

- Software or Tool: Redis (for state)

- Main Book: “Microservices Patterns” by Chris Richardson

What you’ll build: You will upgrade your L7 Proxy into an API Gateway. You will add:

- Rate Limiting: Use the Token Bucket algorithm (backed by Redis) to limit users to 10 requests/second.

- Authentication: Verify a dummy “API Key” header before forwarding.

- Metrics: Count 200s, 400s, and 500s and expose a

/metricsendpoint.

Why it teaches Traffic Management: Proxies aren’t just pipes; they are policy enforcement points. You’ll learn how to reject traffic before it hits your expensive backend servers, protecting them from DDoS and abuse.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Distributed State: Rate limits must be shared across multiple proxy instances (using Redis).

- Latency Impact: Checking Redis for every request adds latency. How do you minimize it? (Pipelining / Lua scripts).

- Fail-Open vs Fail-Closed: If Redis is down, do you block everyone or let everyone in?

Key Concepts:

- Token Bucket Algorithm: Standard for rate limiting.

- Circuit Breaking: Stopping requests to a failing service.

- Observability: The “Golden Signals” (Latency, Traffic, Errors, Saturation).

Real World Outcome

You will try to spam your gateway with curl. The first 10 succeed. The 11th returns 429 Too Many Requests.

Example Output:

$ for i in {1..15}; do curl -s -o /dev/null -w "%{http_code}\n" localhost:8080; done

200

200

...

200

429

429

429

Concepts You Must Understand First (Project 4)

- Token Bucket Algorithm

- How does a token bucket work? (Tokens refill at constant rate, requests consume tokens)

- Why is it better than simple counters? (Allows bursts while maintaining average rate)

- How do you implement it with Redis? (Use Lua scripts for atomic operations)

- Book Reference: “Site Reliability Engineering” (Google) — Ch. 21 (Handling Overload)

- Online Resource: KrakenD Token Bucket Explanation

- Circuit Breaking Pattern

- What is a circuit breaker? (Stops sending requests to failing services)

- What are the three states? (Closed, Open, Half-Open)

- How is it different from retries? (Prevents cascading failures)

- Book Reference: “Release It!” by Michael Nygard — Ch. 5 (Stability Patterns)

- Observability and Metrics

- What are the “Golden Signals”? (Latency, Traffic, Errors, Saturation)

- How do you expose metrics? (Prometheus format:

/metricsendpoint) - What is the difference between metrics, logs, and traces?

- Book Reference: “Site Reliability Engineering” — Ch. 6 (Monitoring Distributed Systems)

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask (Project 4)

- “Why store rate limit state in Redis instead of in-memory?”

- In-memory only works for single-instance gateways

- Redis allows multiple gateway instances to share state (distributed rate limiting)

- Trade-off: Redis adds latency (~1-2ms per check)

- “What happens if Redis goes down?”

- Fail-open: Allow all requests (risky, but maintains availability)

- Fail-closed: Block all requests (safe, but impacts availability)

- Best: Use local cache with fallback to Redis

- “How do you rate-limit by user vs. by IP?”

- Extract user ID from JWT/session cookie (more accurate)

- Fall back to IP address (easier to evade with proxies/VPNs)

- Use sliding window instead of fixed window (prevents burst at boundary)

- “What is the difference between throttling and circuit breaking?”

- Throttling: Limit request rate from clients (protect yourself)

- Circuit breaking: Stop calling failing backends (protect them)

- “How do you implement API key authentication?”

- Store API keys in database (hashed)

- Check

Authorization: Bearer <key>orX-API-Keyheader - Return 401 Unauthorized if missing/invalid

Hints in Layers (Project 4)

Hint 1: Token Bucket with Redis

Use Redis Lua script for atomic rate limiting:

-- rate_limit.lua

local key = KEYS[1]

local max_tokens = tonumber(ARGV[1])

local refill_rate = tonumber(ARGV[2])

local now = tonumber(ARGV[3])

local tokens = redis.call('GET', key)

if not tokens then

tokens = max_tokens

redis.call('SET', key, tokens)

end

if tonumber(tokens) >= 1 then

redis.call('DECR', key)

return 1 -- Allow

else

return 0 -- Deny

end

Call from Go:

result, err := redisClient.Eval(ctx, luaScript, []string{userID}, maxTokens, refillRate, time.Now().Unix()).Result()

if result == 0 {

http.Error(w, "Rate limit exceeded", http.StatusTooManyRequests)

return

}

Hint 2: Simpler In-Memory Rate Limiter

If you don’t want Redis complexity, use an in-memory map:

type RateLimiter struct {

mu sync.Mutex

limits map[string]*TokenBucket

}

type TokenBucket struct {

tokens float64

lastCheck time.Time

}

func (rl *RateLimiter) Allow(userID string) bool {

rl.mu.Lock()

defer rl.mu.Unlock()

bucket := rl.limits[userID]

if bucket == nil {

bucket = &TokenBucket{tokens: 10, lastCheck: time.Now()}

rl.limits[userID] = bucket

}

// Refill tokens based on elapsed time

elapsed := time.Since(bucket.lastCheck).Seconds()

bucket.tokens = math.Min(10, bucket.tokens + elapsed*1.0) // 1 token/second

if bucket.tokens >= 1 {

bucket.tokens -= 1

bucket.lastCheck = time.Now()

return true

}

return false

}

Hint 3: Metrics Endpoint

Expose Prometheus-style metrics:

var (

requestsTotal = 0

requests200 = 0

requests429 = 0

mu sync.Mutex

)

// Middleware to count requests

func metricsMiddleware(next http.Handler) http.Handler {

return http.HandlerFunc(func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

mu.Lock()

requestsTotal++

mu.Unlock()

// Wrap ResponseWriter to capture status code

rw := &responseWriter{ResponseWriter: w}

next.ServeHTTP(rw, r)

mu.Lock()

if rw.status == 200 {

requests200++

} else if rw.status == 429 {

requests429++

}

mu.Unlock()

})

}

// GET /metrics

func metricsHandler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

mu.Lock()

defer mu.Unlock()

fmt.Fprintf(w, "# HELP requests_total Total HTTP requests\n")

fmt.Fprintf(w, "requests_total %d\n", requestsTotal)

fmt.Fprintf(w, "requests_total{status=\"200\"} %d\n", requests200)

fmt.Fprintf(w, "requests_total{status=\"429\"} %d\n", requests429)

}

Common Pitfalls & Debugging (Project 4)

Problem 1: “Rate limiter blocks too early”

- Why: Token refill rate is too slow

- Fix: Increase refill rate or max bucket size:

rate: 10 req/sec, burst: 20

Problem 2: “Redis connection timeout”

- Why: Redis is slow or network issue

- Fix: Set Redis timeout:

client.Options().DialTimeout = 100 * time.Millisecond

Problem 3: “Metrics show 0 for all counters”

- Why: Forgot to use middleware on HTTP handlers

- Fix: Wrap handlers:

http.Handle("/", metricsMiddleware(myHandler))

Problem 4: “Rate limit applies globally instead of per-user”

- Why: Using the same Redis key for all users

- Fix: Include user ID in key:

key := fmt.Sprintf("ratelimit:%s", userID)

Learning Milestones (Project 4)

- First Milestone: Rate limiting works (11th request returns 429)

- Second Milestone: Metrics endpoint shows accurate request counts

- Final Milestone: API key authentication blocks unauthorized requests

Project 5: Envoy Sidecar Mastery

- File: TRAFFIC_MANAGEMENT_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: YAML (Configuration)

- Alternative Programming Languages: N/A

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 5. Industry Disruptor (Service Mesh skills are hot)

- Difficulty: Level 4: Expert

- Knowledge Area: Service Mesh / Modern Ops

- Software or Tool: Envoy Proxy, Docker

- Main Book: “Istio in Action” (covers Envoy deeply)

What you’ll build: You will stop writing your own proxy and move to Envoy, the industry standard. You will configure Envoy as a “Sidecar” next to a service. You will implement:

- Traffic Splitting: Send 90% of traffic to v1 and 10% to v2 (Canary Deployment).

- Fault Injection: Intentionally delay 50% of requests by 2 seconds to see how your app handles it.

Why it teaches Traffic Management: Writing a proxy is good for learning; using Envoy is good for production. This teaches you the “Data Plane” API. You will understand how modern meshes like Istio manipulate traffic without changing application code.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- YAML Hell: Envoy configuration is verbose and complex.

- Filter Chains: Understanding the order of operations (Listener -> Filter -> Route -> Cluster).

- Debugging: Why is Envoy rejecting my config? (Admin interface usage).

Key Concepts:

- Sidecar Pattern: Running a proxy in the same container/pod.

- xDS Protocol: How Envoy discovers configuration dynamically.

- Canary Releasing: Gradual rollouts.

Real World Outcome

You’ll have a docker-compose setup. When you hit localhost:8080, 1 out of 10 times you get a different response (v2), and sometimes the request hangs (simulated latency), proving your traffic rules are active.

Example Output:

# Envoy Config Snippet

routes:

- match: { prefix: "/" }

route:

weighted_clusters:

clusters:

- name: service_v1

weight: 90

- name: service_v2

weight: 10

Concepts You Must Understand First (Project 5)

- Sidecar Pattern

- What is a sidecar? (Auxiliary container running alongside main app)

- Why not run Envoy as a separate service? (Sidecar shares network namespace, sees localhost traffic)

- How does service mesh inject sidecars? (Kubernetes mutating webhook)

- Book Reference: “Istio in Action” by Christian Posta — Ch. 2 (Istio Architecture)

- xDS Protocol (Envoy Discovery Service)

- What is xDS? (gRPC APIs for dynamic configuration: LDS, RDS, CDS, EDS)

- Static vs dynamic configuration—when to use each?

- What is a snapshot in Envoy? (Versioned config state)

- Online Resource: Envoy xDS Protocol

- Traffic Splitting and Canary Deployments

- How do you route 10% of traffic to a new version?

- What is the difference between weighted routing and header-based routing?

- How do you measure canary success? (Error rate, latency)

- Book Reference: “Site Reliability Engineering” — Ch. 16 (Tracking Outages)

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask (Project 5)

- “Why use Envoy instead of NGINX?”

- Envoy is designed for service mesh (dynamic configuration via xDS)

- NGINX requires config file reloads (less dynamic)

- Envoy has better observability (built-in tracing, stats)

- “What is the difference between a listener, route, and cluster in Envoy?”

- Listener: Where Envoy accepts connections (e.g., port 8080)

- Route: How to match requests (e.g.,

/apigoes to cluster A) - Cluster: Group of backend endpoints (e.g., service-a:8001, service-a:8002)

- “How does Envoy handle TLS termination?”

- Configure

transport_socketwith TLS certificates - Envoy decrypts at the edge, sends plain HTTP to backends (more efficient)

- Configure

- “What is fault injection used for?”

- Testing resilience (chaos engineering)

- Inject delays or errors to see if app handles failures gracefully

Hints in Layers (Project 5)

Hint 1: Docker Compose Setup

version: '3'

services:

envoy:

image: envoyproxy/envoy:v1.28-latest

ports:

- "10000:10000"

- "9901:9901" # Admin interface

volumes:

- ./envoy.yaml:/etc/envoy/envoy.yaml

service_v1:

image: hashicorp/http-echo

command: ["-text", "Version 1"]

ports:

- "8001:5678"

service_v2:

image: hashicorp/http-echo

command: ["-text", "Version 2"]

ports:

- "8002:5678"

Hint 2: Minimal Envoy Config

static_resources:

listeners:

- name: listener_0

address:

socket_address: { address: 0.0.0.0, port_value: 10000 }

filter_chains:

- filters:

- name: envoy.filters.network.http_connection_manager

typed_config:

"@type": type.googleapis.com/envoy.extensions.filters.network.http_connection_manager.v3.HttpConnectionManager

stat_prefix: ingress_http

route_config:

name: local_route

virtual_hosts:

- name: backend

domains: ["*"]

routes:

- match: { prefix: "/" }

route:

weighted_clusters:

clusters:

- name: service_v1

weight: 90

- name: service_v2

weight: 10

http_filters:

- name: envoy.filters.http.router

clusters:

- name: service_v1

connect_timeout: 0.25s

type: STRICT_DNS

lb_policy: ROUND_ROBIN

load_assignment:

cluster_name: service_v1

endpoints:

- lb_endpoints:

- endpoint:

address:

socket_address: { address: service_v1, port_value: 5678 }

- name: service_v2

connect_timeout: 0.25s

type: STRICT_DNS

lb_policy: ROUND_ROBIN

load_assignment:

cluster_name: service_v2

endpoints:

- lb_endpoints:

- endpoint:

address:

socket_address: { address: service_v2, port_value: 5678 }

Hint 3: Testing Traffic Split

# Send 100 requests

for i in {1..100}; do curl -s localhost:10000; done | sort | uniq -c

# Expected output:

# 90 Version 1

# 10 Version 2

Common Pitfalls & Debugging (Project 5)

Problem 1: “Envoy fails to start: config validation error”

- Why: YAML indentation is wrong or missing required field

- Fix: Use

envoy --mode validate -c envoy.yamlto check config - Quick test: Check admin interface:

curl localhost:9901/config_dump

Problem 2: “All traffic goes to one version”

- Why: Weights are set incorrectly or cluster names don’t match

- Fix: Verify cluster names in

weighted_clustersmatch cluster definitions

Problem 3: “503 Service Unavailable”

- Why: Backend service isn’t reachable (wrong hostname/port)

- Fix: Check Envoy logs:

docker logs <envoy-container>

Learning Milestones (Project 5)

- First Milestone: Envoy forwards traffic to a single backend

- Second Milestone: Traffic splitting works (90/10 distribution)

- Final Milestone: Fault injection adds delays to requests

Project 6: The Mesh Control Plane (xDS Server)

- File: TRAFFIC_MANAGEMENT_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: Go

- Alternative Programming Languages: Java, Python

- Coolness Level: Level 5: Pure Magic

- Business Potential: 5. Industry Disruptor

- Difficulty: Level 5: Master

- Knowledge Area: Service Mesh Architecture

- Software or Tool: gRPC, Protobuf

- Main Book: Envoy Official Docs (xDS APIs)

What you’ll build: A simple Control Plane for Envoy. Instead of writing static YAML files (Project 5), your Go program will serve configuration to Envoy via gRPC. When a new service registers (like in Project 3), your Control Plane will push the new route to Envoy in real-time without restarting it.

Why it teaches Traffic Management: This is the pinnacle. You are building your own Istio. You’ll understand the separation of Control Plane (policy/config) and Data Plane (packet moving). This is how hyper-scale infrastructure works.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- gRPC/Protobuf: Implementing the Envoy Discovery Service (EDS) and Route Discovery Service (RDS) APIs.

- Version Processing: Envoy only updates if the config version changes.

- Snapshot Management: Keeping the state consistent.

Key Concepts:

- Control Plane vs Data Plane: The fundamental architecture of SDN (Software Defined Networking).

- gRPC Streaming: Bidirectional streams for config updates.

- Dynamic Reconfiguration: Zero-downtime changes.

Real World Outcome

You start Envoy with a “bootstrap” config pointing to your Go server. You start your Go server. Initially, Envoy has no routes. You type a command into your Go server CLI add-route /new -> service-b. Instantly, curl localhost:10000/new starts working.

Example Output:

[Control Plane] Received DiscoveryRequest from Envoy-1

[Control Plane] Pushing new snapshot (Version 2) with 1 Cluster, 1 Route.

[Envoy Log] config: all dependencies initialized. Starting workers.

Concepts You Must Understand First (Project 6)

- Control Plane vs Data Plane

- Control Plane: “The brain” that makes decisions (your xDS server)

- Data Plane: “The hands” that move packets (Envoy proxies)

- Why separate them? (Scale: 1 control plane can manage 1000s of data planes)

- Book Reference: “Istio in Action” — Ch. 3 (Control Plane Architecture)

- gRPC and Protobuf

- Why does Envoy use gRPC instead of REST? (Bidirectional streaming, efficiency)

- What is a

.protofile? (Contract defining messages and RPCs) - How do you version xDS APIs? (v2 vs v3)

- Book Reference: “gRPC: Up and Running” by Kasun Indrasiri — Ch. 1-2

- Snapshot Versioning

- Why does Envoy only update when version changes?

- How do you generate version strings? (Timestamp, hash, counter)

- What happens if version is the same? (Envoy ignores the update)

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask (Project 6)

- “How does Envoy know when the control plane has new config?”

- Envoy opens a gRPC stream to the control plane

- Control plane pushes updates when config changes

- Envoy ACKs or NACKs (negative acknowledgment) the update

- “What is the difference between EDS, CDS, LDS, and RDS?”

- EDS (Endpoint Discovery): List of backend IPs

- CDS (Cluster Discovery): Backend service definitions

- LDS (Listener Discovery): Where Envoy listens (ports)

- RDS (Route Discovery): URL routing rules

- “How would you handle config rollback if Envoy rejects it?”

- Envoy sends NACK with error message

- Control plane logs the error and reverts to previous snapshot

- Use validation before pushing (dry-run)

Hints in Layers (Project 6)

Hint 1: Use go-control-plane Library

Don’t implement xDS from scratch—use Envoy’s official Go library:

go get github.com/envoyproxy/go-control-plane

Hint 2: Minimal xDS Server

package main

import (

"context"

"github.com/envoyproxy/go-control-plane/pkg/cache/v3"

"github.com/envoyproxy/go-control-plane/pkg/server/v3"

"github.com/envoyproxy/go-control-plane/pkg/test/v3"

)

func main() {

snapshotCache := cache.NewSnapshotCache(false, cache.IDHash{}, nil)

srv := server.NewServer(context.Background(), snapshotCache, nil)

// Create initial snapshot

snapshot := generateSnapshot()

snapshotCache.SetSnapshot(context.Background(), "node1", snapshot)

// Start gRPC server...

}

Hint 3: CLI to Update Config

Add a simple HTTP API to your control plane:

// POST /update-route?path=/new&backend=service-b:8080

func updateRoute(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

path := r.URL.Query().Get("path")

backend := r.URL.Query().Get("backend")

// Generate new snapshot with updated route

newSnapshot := generateSnapshotWithRoute(path, backend)

// Push to Envoy

snapshotCache.SetSnapshot(context.Background(), "node1", newSnapshot)

fmt.Fprintf(w, "Updated!")

}

Learning Milestones (Project 6)

- First Milestone: Envoy connects to your control plane and receives initial config

- Second Milestone: You can add/remove routes dynamically without restarting Envoy

- Final Milestone: You integrate Project 3’s registry to automatically update Envoy when services register

Project 7: Global Traffic Director (Geo-DNS)

- File: TRAFFIC_MANAGEMENT_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: Go or Python

- Alternative Programming Languages: Bind9 (Config only), CoreDNS (Plugin)

- Coolness Level: Level 5: Pure Magic

- Business Potential: 5. Industry Disruptor

- Difficulty: Level 5: Master

- Knowledge Area: Global Networking / DNS

- Software or Tool: DNS Protocol, GeoIP Database

- Main Book: “High Performance Browser Networking”

What you’ll build: A custom DNS server that returns different IP addresses based on the geographic location of the requester (simulated). If a user from “US” asks for myapp.com, return 1.2.3.4. If from “EU”, return 5.6.7.8.

Why it teaches Traffic Management: Traffic management starts before the first TCP packet is sent. DNS is the ultimate global load balancer. You’ll learn how companies like Netflix route you to the closest datacenter.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- DNS Protocol Parsing: UDP Packet format for DNS (512 bytes limit).

- GeoIP Lookup: Querying a database to map IP -> Country.

- Anycast (Concept): Understanding how Google’s 8.8.8.8 exists everywhere.

Real World Outcome

You query your local DNS server asking for myapp.com while pretending to be from different subnets (using dig +subnet).

Example Output:

$ dig @localhost myapp.com +subnet=192.168.1.0/24 # Simulate US IP

;; ANSWER SECTION:

myapp.com. 300 IN A 10.0.0.1 (US-West)

$ dig @localhost myapp.com +subnet=100.20.30.0/24 # Simulate EU IP

;; ANSWER SECTION:

myapp.com. 300 IN A 10.0.0.2 (EU-Central)

Concepts You Must Understand First (Project 7)

- DNS Protocol Basics

- What is the structure of a DNS query packet? (Header, Question, Answer, Authority, Additional)

- How does UDP limit DNS packets to 512 bytes? (EDNS0 extends this)

- What is a DNS A record vs AAAA vs CNAME?

- Book Reference: “TCP/IP Illustrated, Volume 1” — Ch. 14 (DNS)

- GeoDNS and Anycast

- How does GeoDNS determine client location? (EDNS Client Subnet, GeoIP databases)

- What is Anycast routing? (Same IP announced from multiple locations)

- How does Google’s 8.8.8.8 exist everywhere? (BGP anycast)

- Book Reference: “High Performance Browser Networking” — Ch. 2 (Building Blocks of TCP)

- DNS Caching and TTL

- Why can’t you instantly change DNS records? (TTL causes caching)

- What is the difference between authoritative and recursive DNS?

- How do you flush DNS cache? (OS-specific commands)

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask (Project 7)

- “How do CDNs use DNS for traffic routing?”

- Return different IPs based on client location (GeoDNS)

- Client gets routed to nearest edge server

- Reduces latency and improves user experience

- “What is the difference between GeoDNS and Global Server Load Balancing (GSLB)?”

- GeoDNS: Returns different IPs based on location (DNS layer)

- GSLB: Redirects at application layer (HTTP 302)

- GeoDNS is faster but less flexible

- “Why is DNS still primarily UDP instead of TCP?”

- UDP is faster (no handshake overhead)

- DNS queries are small (fit in one packet)

- TCP is only used for zone transfers or large responses

Hints in Layers (Project 7)

Hint 1: DNS Packet Structure

Use a DNS library instead of parsing manually:

# Go

go get github.com/miekg/dns

# Python

pip install dnspython

Hint 2: Minimal DNS Server (Go)

package main

import (

"github.com/miekg/dns"

"log"

)

func handleDNS(w dns.ResponseWriter, r *dns.Msg) {

m := new(dns.Msg)

m.SetReply(r)

if r.Question[0].Name == "myapp.com." {

// Extract client IP (simplified)

clientIP := w.RemoteAddr().String()

// Lookup GeoIP (simplified: just check subnet)

var ip string

if clientIP[:3] == "192" { // US IP range

ip = "10.0.0.1"

} else {

ip = "10.0.0.2" // EU IP range

}

rr, _ := dns.NewRR("myapp.com. 300 IN A " + ip)

m.Answer = append(m.Answer, rr)

}

w.WriteMsg(m)

}

func main() {

dns.HandleFunc(".", handleDNS)

server := &dns.Server{Addr: ":53", Net: "udp"}

log.Fatal(server.ListenAndServe())

}

Hint 3: GeoIP Database

Use MaxMind GeoLite2 (free):

# Download database

wget https://github.com/P3TERX/GeoLite.mmdb/raw/download/GeoLite2-Country.mmdb

import "github.com/oschwald/geoip2-golang"

db, _ := geoip2.Open("GeoLite2-Country.mmdb")

defer db.Close()

record, _ := db.Country(net.ParseIP(clientIP))

country := record.Country.IsoCode // "US", "GB", etc.

if country == "US" {

return "10.0.0.1" // US datacenter

} else if country == "GB" || country == "DE" {

return "10.0.0.2" // EU datacenter

} else {

return "10.0.0.3" // APAC datacenter

}

Common Pitfalls & Debugging (Project 7)

Problem 1: “Permission denied when binding to port 53”

- Why: Ports <1024 require root privileges

- Fix: Run with

sudoor use port 5353 for testing

Problem 2: “dig returns SERVFAIL”

- Why: Your DNS response is malformed

- Fix: Use

dns.SetReply(r)to copy question section to response

Problem 3: “All clients get the same IP”

- Why: Not extracting client IP correctly (might see localhost)

- Fix: Use EDNS Client Subnet:

r.IsEdns0().Option

Learning Milestones (Project 7)

- First Milestone: Your DNS server responds to queries with hardcoded IPs

- Second Milestone: GeoDNS returns different IPs based on client location

- Final Milestone: Integrated with a GeoIP database for real location lookup

Project Comparison Table

| Project | Difficulty | Time | Depth of Understanding | Fun Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Packet Shuffler | ⭐⭐ | Weekend | Low-level TCP internals | ⭐⭐⭐ |

| 2. Header Inspector | ⭐⭐⭐ | 1 week | HTTP Protocol Mastery | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ |

| 3. Heartbeat Registry | ⭐⭐⭐ | 1 week | Dynamic Infrastructure | ⭐⭐⭐ |

| 4. Intelligent Gatekeeper | ⭐⭐⭐ | 1 week | Security & Limits | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ |

| 5. Envoy Sidecar | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ | Weekend | Industry Standard Tools | ⭐⭐⭐ |

| 6. Mesh Control Plane | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ | 2 weeks | Architecture Mastery | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ |

| 7. Global Traffic Director | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ | 1-2 weeks | Global Scale | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ |

Recommendation

Start with Project 2 (The Header Inspector). HTTP is the lingua franca of the web. Building a proxy from scratch removes all the mystery of NGINX configuration files.

If you want to be a DevOps/SRE: Jump to Project 5 (Envoy) and Project 3 (Registry).

If you want to be a Backend Architect: Focus on Project 4 (Gateway) and Project 6 (Control Plane).

Final Overall Project: The “Zero-Trust” Service Mesh

What you’ll build: A complete microservices platform combining all previous concepts.

- Data Plane: Envoy Sidecars running alongside 3 different microservices (User, Billing, Frontend).

- Control Plane: Your custom xDS server (Project 6) pushing configs.

- Discovery: Your Registry (Project 3) feeding the Control Plane.

- Edge: Your Gateway (Project 4) handling external traffic.

- Security: Enforce Mutual TLS (mTLS) between all services (Envoy handles this).

Why this is the ultimate test: It simulates a real production environment at a tech giant. You aren’t just moving bytes; you are defining policies, securing communication, and observing traffic flows across a distributed system.

Summary

This learning path covers Traffic Management through 7 hands-on projects. Here’s the complete list:

| # | Project Name | Main Language | Difficulty | Time Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Packet Shuffler | Go/C | Intermediate | Weekend |

| 2 | The Header Inspector | Go/Python | Advanced | 1 week |

| 3 | The Heartbeat Registry | Go/Python | Advanced | 1 week |

| 4 | The Intelligent Gatekeeper | Go | Advanced | 1 week |

| 5 | Envoy Sidecar Mastery | YAML | Expert | Weekend |

| 6 | The Mesh Control Plane | Go | Master | 2 weeks |

| 7 | Global Traffic Director | Go | Master | 1-2 weeks |

Expected Outcomes

After completing these projects, you will:

- Understand the difference between L4 and L7 load balancing at a packet level.

- Be able to write your own reverse proxy and load balancer from scratch.

- Master the configuration of Envoy and understand the xDS protocol.

- Architect high-availability systems using Service Discovery and Health Checking.

- Implement critical reliability patterns like Rate Limiting and Circuit Breaking.