Top 10 Projects for Job Interview Mastery - Learning Guide

Goal: Master the fundamental systems that power modern software by building 10 core projects that every senior engineer should deeply understand. You’ll learn how memory allocators work, how distributed systems achieve consensus, how databases persist data, and how abstractions like containers and interpreters actually function—not through theory, but by implementing them from scratch. After completing these projects, you’ll confidently answer any systems interview question, debug complex production issues, and design scalable architectures because you’ll understand the machinery underneath every abstraction layer.

This guide expands on each project to help you think deeply about what you’re building. No code here - just concepts, questions, and nudges to guide your learning journey.

Before You Start: The Right Mindset

These projects aren’t about “getting them done.” They’re about understanding the systems that power modern software.

When interviewers ask about these topics, they’re not looking for memorized answers. They want to see:

- How you think through problems

- Whether you understand trade-offs

- If you can explain why things work, not just what they do

For each project, ask yourself:

- “What problem is this really solving?”

- “What would happen if I didn’t have this?”

- “Where else have I seen this pattern?”

Part I: Deep Foundations

Before diving into any project, you need mental models of the systems you’re building. This section gives you the conceptual scaffolding that makes everything else click.

Why These 10 Projects?

These aren’t random projects. Each one forces you to confront a fundamental truth about computing that most developers never see:

| Project | The Truth It Reveals |

|---|---|

| malloc | Memory is just numbered bytes. Your language hides this. |

| Load Balancer | Networks fail. Everything in distributed systems is about handling failure. |

| Key-Value Store | All databases are files. The magic is in the data structures. |

| Raft Consensus | You cannot trust time, messages, or other machines. Agreement is hard. |

| Containers | There is no “container.” It’s just a process with isolation. |

| Interpreter | Code is data. Execution is tree walking. |

| Lock-Free Queue | CPUs reorder operations. Memory is not what you think. |

| TCP Server | HTTP is just text over a socket. Frameworks hide the simplicity. |

| Mini-React | UI frameworks are reconciliation engines. Virtual DOM is just diffing. |

| Git Objects | Git is a content-addressable filesystem. Commits are text files. |

Each project strips away an abstraction layer and shows you the machinery underneath.

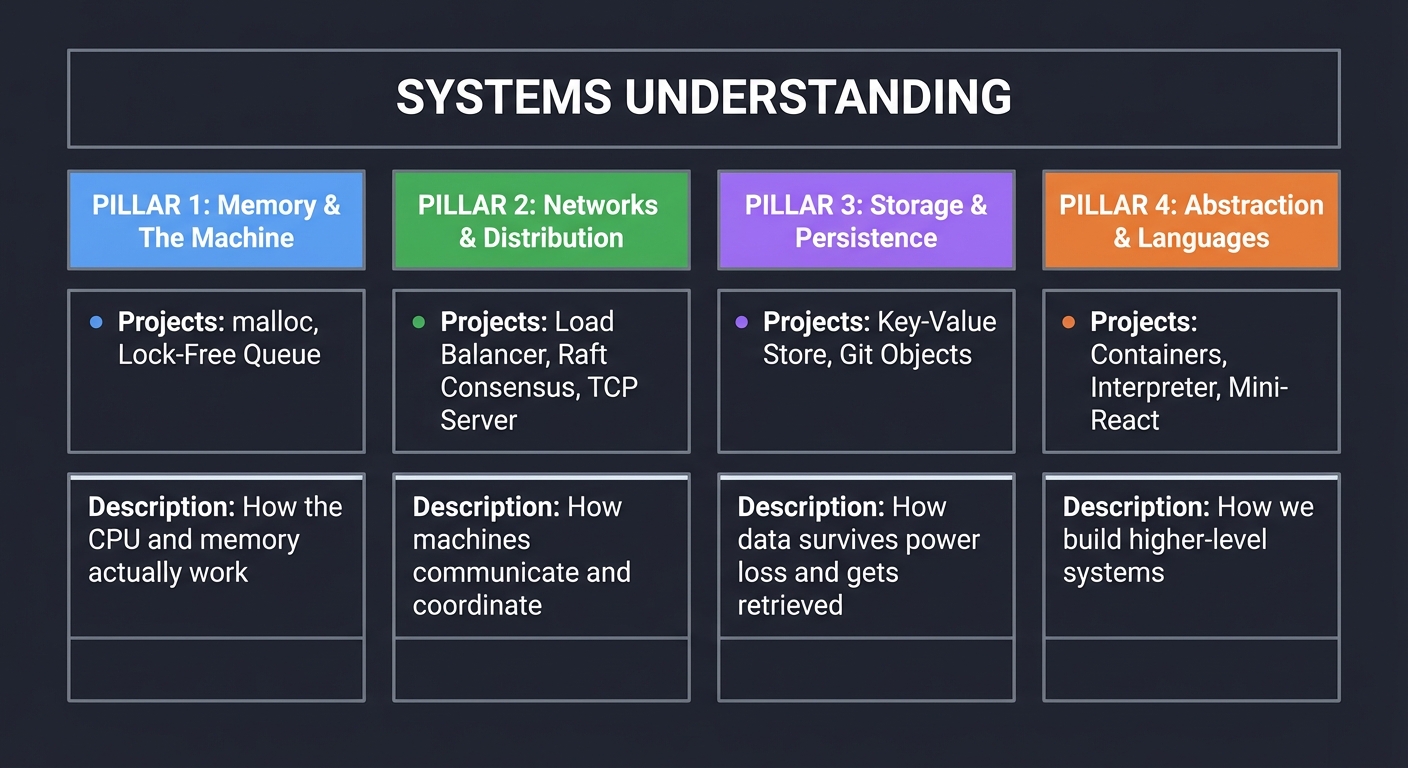

The Four Pillars of Systems Understanding

All 10 projects map to four fundamental areas. Master these, and you can build anything:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ SYSTEMS UNDERSTANDING │

├──────────────────┬──────────────────┬──────────────────┬───────────────────┤

│ PILLAR 1 │ PILLAR 2 │ PILLAR 3 │ PILLAR 4 │

│ Memory & │ Networks & │ Storage & │ Abstraction & │

│ The Machine │ Distribution │ Persistence │ Languages │

├──────────────────┼──────────────────┼──────────────────┼───────────────────┤

│ • malloc │ • Load Balancer │ • Key-Value Store│ • Containers │

│ • Lock-Free Queue│ • Raft Consensus │ • Git Objects │ • Interpreter │

│ │ • TCP Server │ │ • Mini-React │

├──────────────────┼──────────────────┼──────────────────┼───────────────────┤

│ How the CPU and │ How machines │ How data survives│ How we build │

│ memory actually │ communicate and │ power loss and │ higher-level │

│ work │ coordinate │ gets retrieved │ systems │

└──────────────────┴──────────────────┴──────────────────┴───────────────────┘

Pillar 1: Memory & The Machine

Projects: malloc (Project 1), Lock-Free Queue (Project 7)

The Big Picture: How Memory Really Works

Everything in computing ultimately happens in memory. When you understand memory, you understand computing.

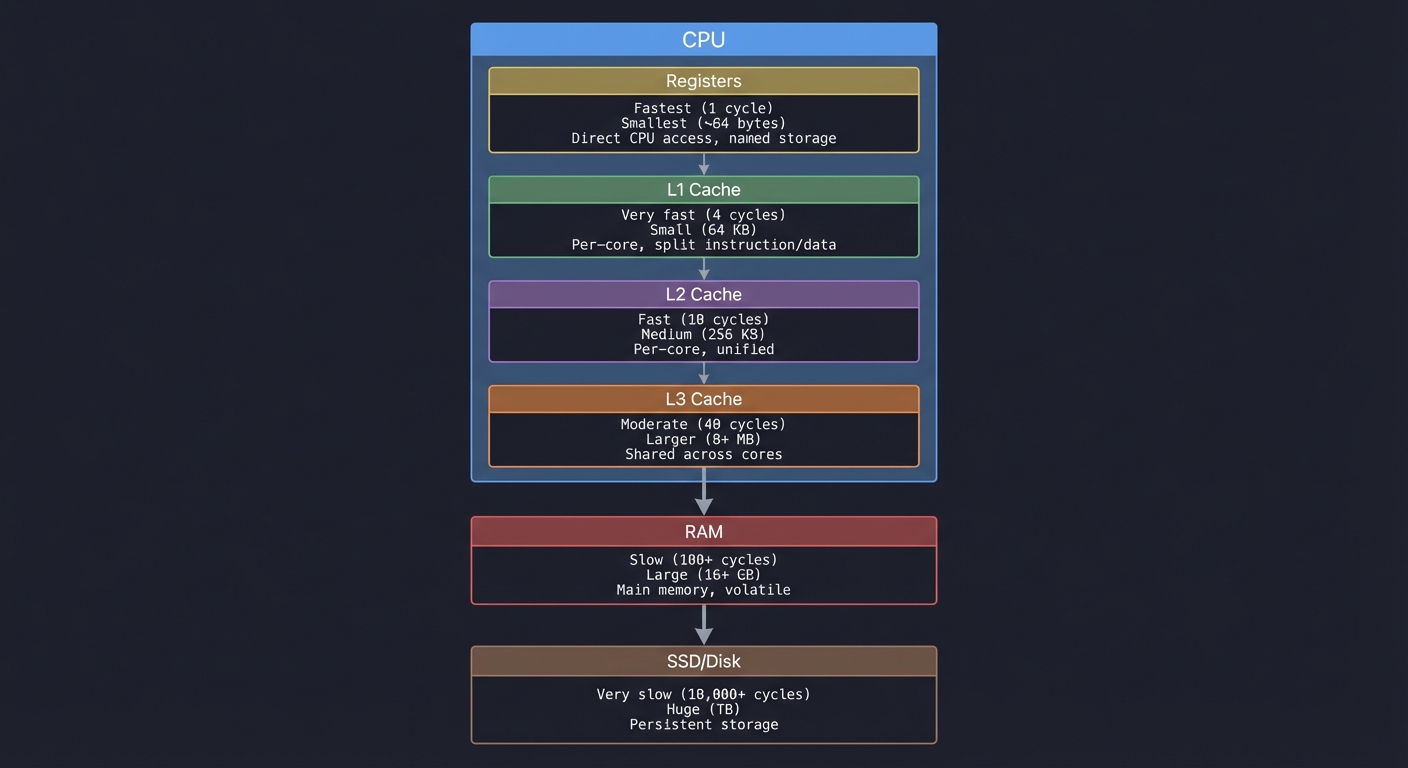

The Memory Hierarchy

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ CPU │

│ ┌─────────┐ │

│ │ Registers│ ← Fastest (1 cycle), smallest (~64 bytes) │

│ └────┬────┘ Direct CPU access, named storage │

│ │ │

│ ┌────┴────┐ │

│ │ L1 Cache│ ← Very fast (4 cycles), small (64 KB) │

│ └────┬────┘ Per-core, split instruction/data │

│ │ │

│ ┌────┴────┐ │

│ │ L2 Cache│ ← Fast (10 cycles), medium (256 KB) │

│ └────┬────┘ Per-core, unified │

│ │ │

│ ┌────┴────┐ │

│ │ L3 Cache│ ← Moderate (40 cycles), larger (8+ MB) │

│ └────┬────┘ Shared across cores │

└───────┼─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

┌───────┴─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ RAM ← Slow (100+ cycles), large (16+ GB) │

│ Main memory, volatile │

└───────┬─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

┌───────┴─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ SSD/Disk ← Very slow (10,000+ cycles), huge (TB) │

│ Persistent storage │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Key insight: A cache miss can be 100x slower than a hit. This is why data structures matter—not for theoretical Big-O, but for cache behavior.

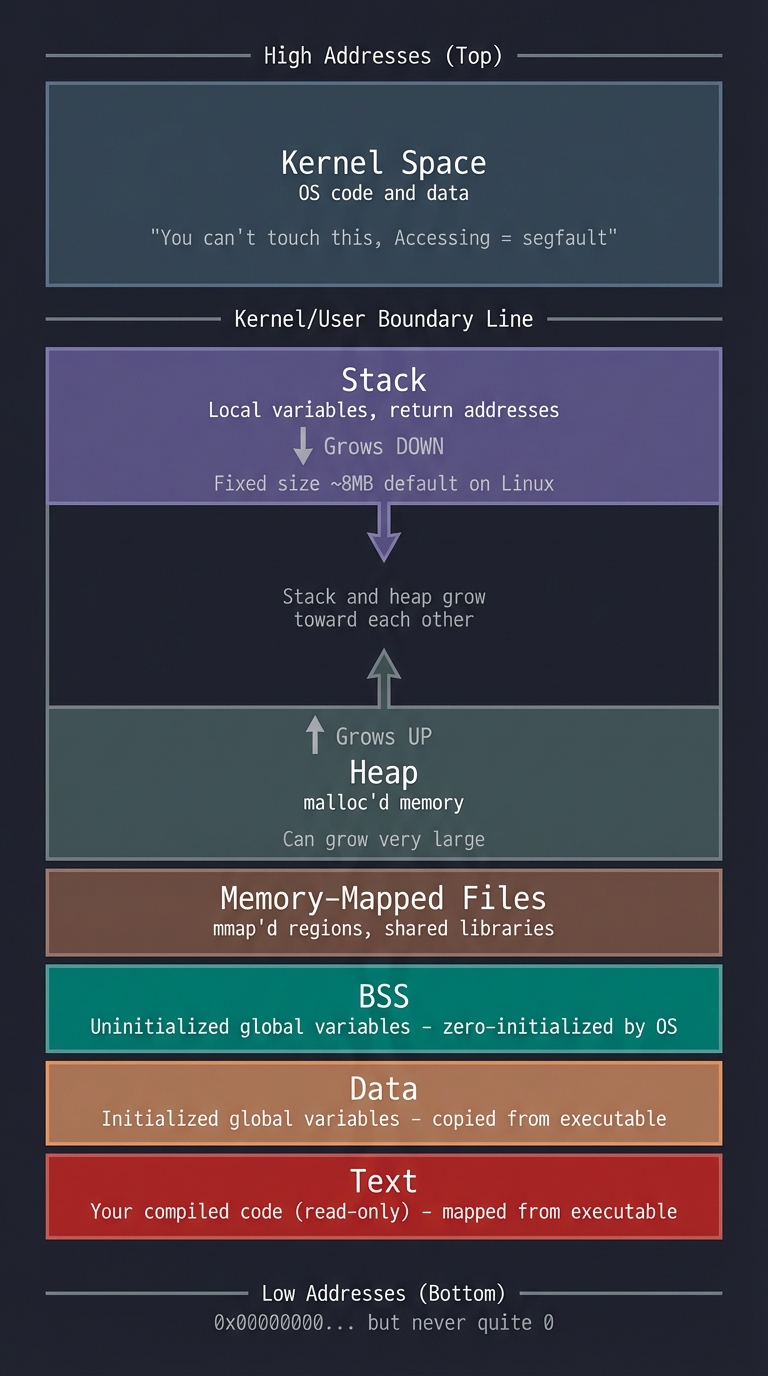

A Process’s Memory Layout

When your program runs, the OS gives it a virtual address space:

High addresses (0xFFFFFFFF on 32-bit / 0x7FFF... on 64-bit)

┌────────────────────────────┐

│ Kernel Space │ ← You can't touch this

│ (OS code and data) │ Accessing = segfault

├────────────────────────────┤ ← The "kernel/user boundary"

│ │

│ Stack │ ← Local variables, return addresses

│ ↓ │ Grows DOWN toward lower addresses

│ │ Fixed size (~8MB default on Linux)

│ (unmapped region) │

│ │ ← Stack and heap grow toward each other

│ ↑ │

│ Heap │ ← malloc'd memory

│ │ Grows UP toward higher addresses

│ │ Can grow very large

├────────────────────────────┤

│ Memory-Mapped Files │ ← mmap'd regions, shared libraries

├────────────────────────────┤

│ BSS │ ← Uninitialized global variables

│ │ (zero-initialized by OS)

├────────────────────────────┤

│ Data │ ← Initialized global variables

│ │ (copied from executable)

├────────────────────────────┤

│ Text │ ← Your compiled code (read-only)

│ │ (mapped from executable)

└────────────────────────────┘

Low addresses (0x00000000... but never quite 0)

Why this matters for malloc: malloc manages the heap region. It asks the OS for more heap space (via brk/sbrk or mmap) and carves it up for you.

Why this matters for lock-free: Multiple threads share this space. When two cores access the same cache line, you get “false sharing” and performance tanks.

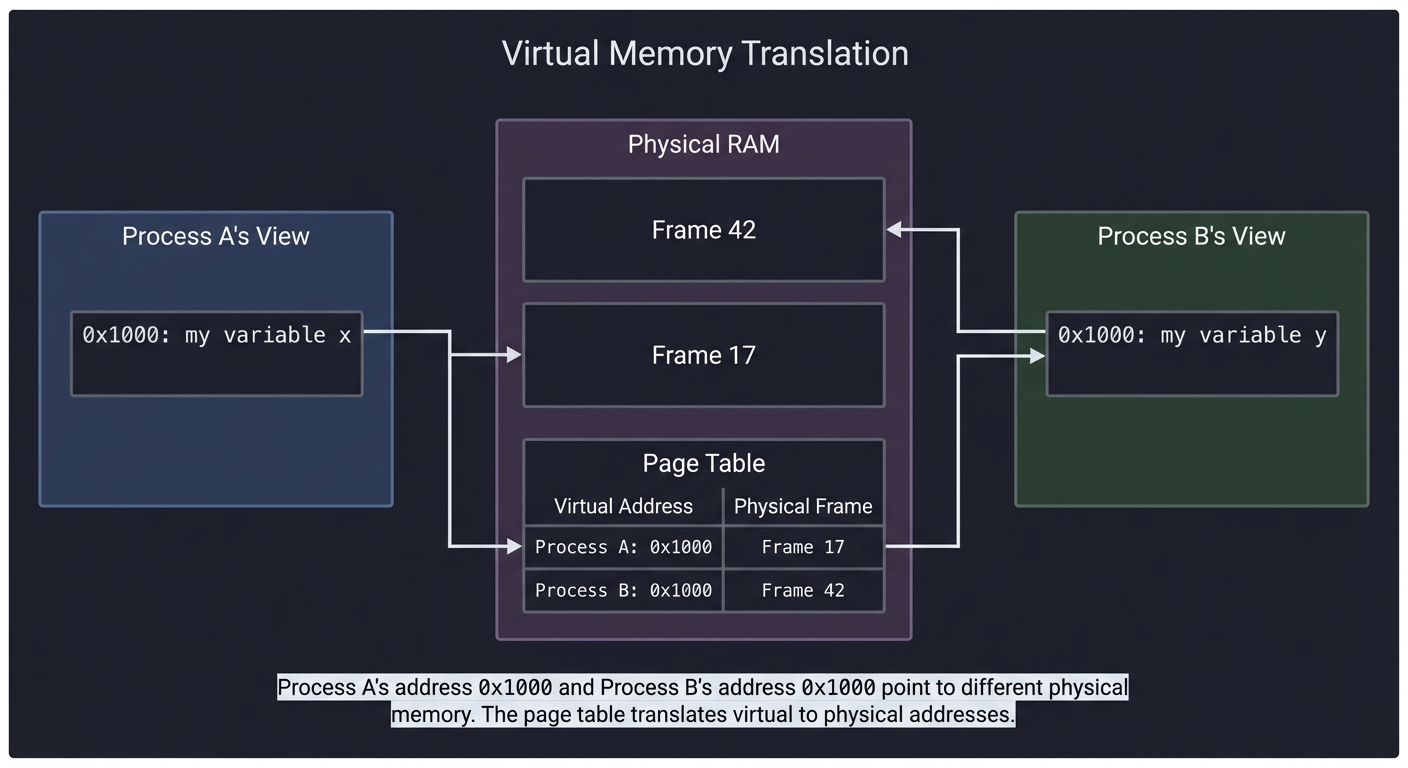

Virtual Memory: The Illusion

Every process thinks it has the entire address space to itself. This is an illusion:

Process A's View Physical RAM Process B's View

┌──────────────┐ ┌──────────────┐

│ 0x1000: my │ ┌──────────┐ │ 0x1000: my │

│ variable x │───┐ │ Frame 42 │ ┌────│ variable y │

└──────────────┘ │ └──────────┘ │ └──────────────┘

│ ↑ │

│ ┌──────────┐ │

└────→│ Frame 17 │←───┘

└──────────┘

↑

┌──────────┐

│ Page Table│ ← Maps virtual → physical

└──────────┘

Key insight: Process A’s address 0x1000 and Process B’s address 0x1000 point to different physical memory. The page table (managed by the OS) translates virtual addresses to physical addresses.

Why this matters for malloc: When you call brk() to grow the heap, you’re asking the OS to add entries to your page table—to make more virtual addresses valid.

Why this matters for containers: Linux namespaces give processes different “views” of the system. Memory isolation is one aspect of containerization.

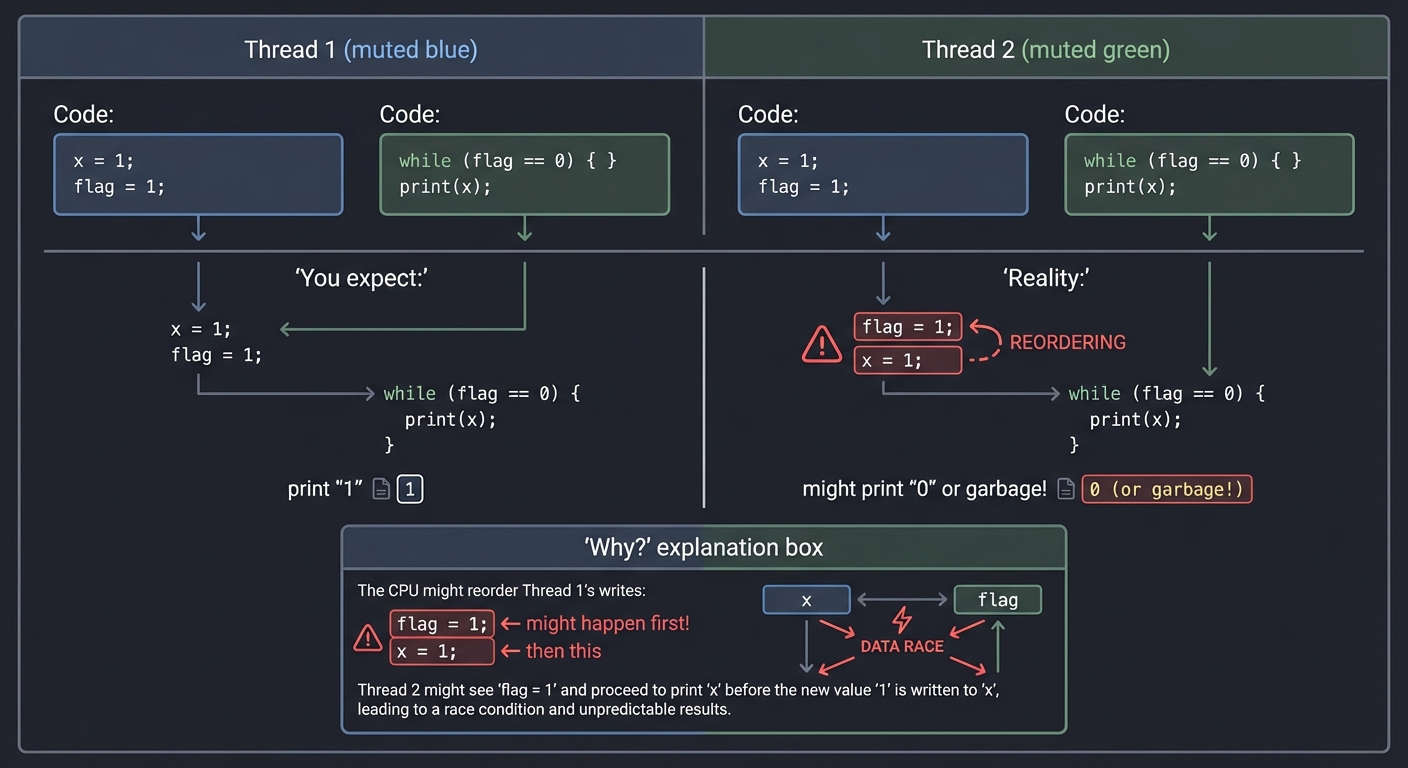

Atomic Operations and Memory Ordering

Modern CPUs reorder operations for performance. This breaks naive concurrent code:

Thread 1 Thread 2

───────── ─────────

x = 1; while (flag == 0) { }

flag = 1; print(x);

You expect: print "1"

Reality: might print "0" or garbage!

Why? The CPU might reorder Thread 1's writes:

flag = 1; ← might happen first!

x = 1; ← then this

Memory barriers (fences) force ordering. Atomic operations come with ordering guarantees:

| Ordering | Guarantee |

|---|---|

| Relaxed | No ordering, just atomicity |

| Acquire | No reads/writes can be reordered BEFORE this |

| Release | No reads/writes can be reordered AFTER this |

| SeqCst | Total ordering (slowest, safest) |

Why this matters for lock-free: Every lock-free data structure must carefully choose memory orderings. Wrong choice = subtle corruption.

Deep Dive Reading: Memory & The Machine

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Memory hierarchy | Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective Ch. 6 - Bryant & O’Hallaron |

| Virtual memory | Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective Ch. 9 - Bryant & O’Hallaron |

| Process address space | Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces Ch. 13-15 - Arpaci-Dusseau |

| malloc internals | Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective Ch. 9.9 - Bryant & O’Hallaron |

| Atomic operations | Rust Atomics and Locks Ch. 1-3 - Mara Bos |

| Memory ordering | C++ Concurrency in Action Ch. 5 - Anthony Williams |

| Cache behavior | What Every Programmer Should Know About Memory - Ulrich Drepper (paper) |

Pillar 2: Networks & Distribution

Projects: Load Balancer (Project 2), Raft Consensus (Project 4), TCP Server (Project 8)

The Big Picture: How Machines Communicate

All network programming boils down to two things: moving bytes between machines, and handling the fact that this can fail at any time.

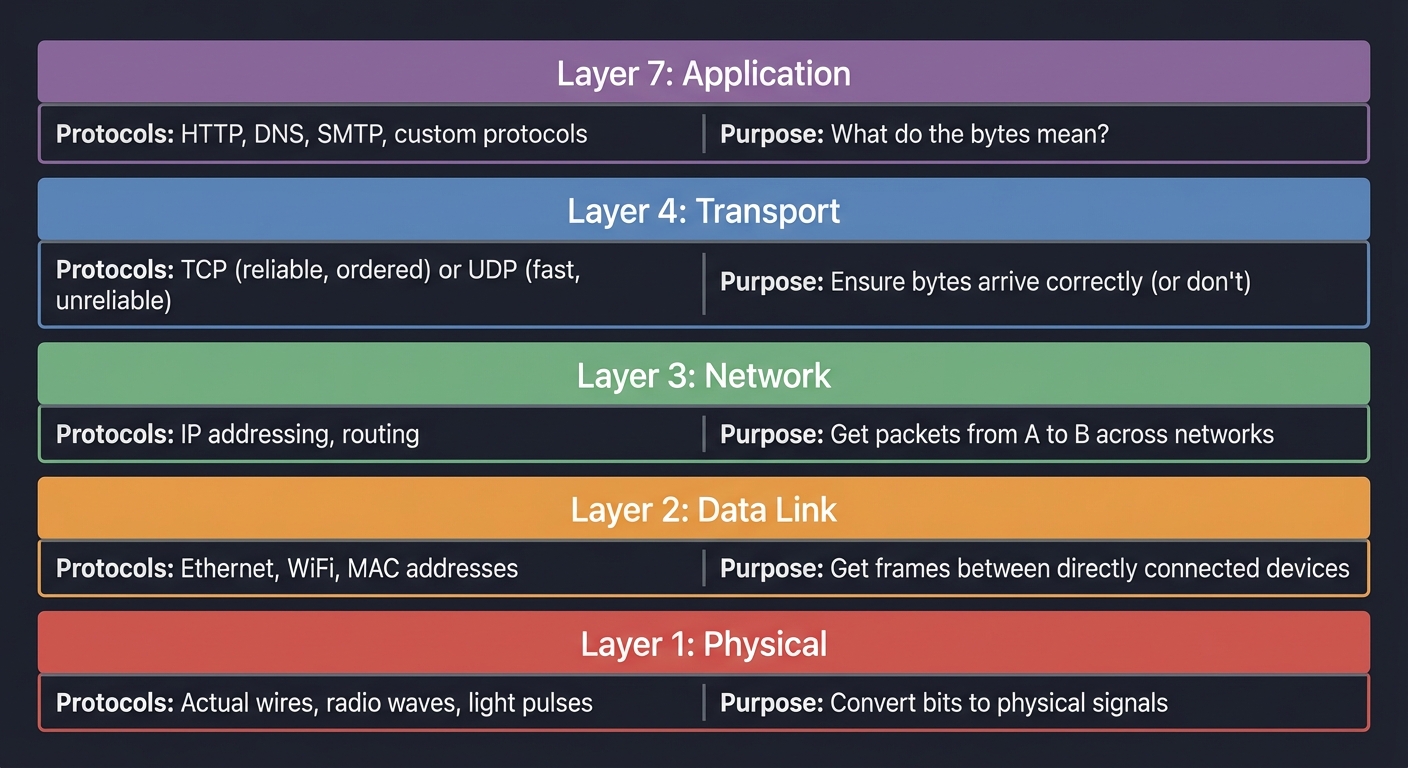

The Network Stack (Simplified)

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Layer 7: Application │

│ HTTP, DNS, SMTP, your custom protocols │

│ "What do the bytes mean?" │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Layer 4: Transport │

│ TCP (reliable, ordered) or UDP (fast, unreliable) │

│ "Ensure bytes arrive correctly (or don't)" │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Layer 3: Network │

│ IP addressing, routing │

│ "Get packets from A to B across networks" │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Layer 2: Data Link │

│ Ethernet, WiFi, MAC addresses │

│ "Get frames between directly connected devices" │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Layer 1: Physical │

│ Actual wires, radio waves, light pulses │

│ "Convert bits to physical signals" │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Why this matters for load balancers:

- L4 load balancer: Works at TCP level. Sees source/dest IP and port. Fast but limited.

- L7 load balancer: Works at HTTP level. Can route based on URL, headers, cookies. Slower but smarter.

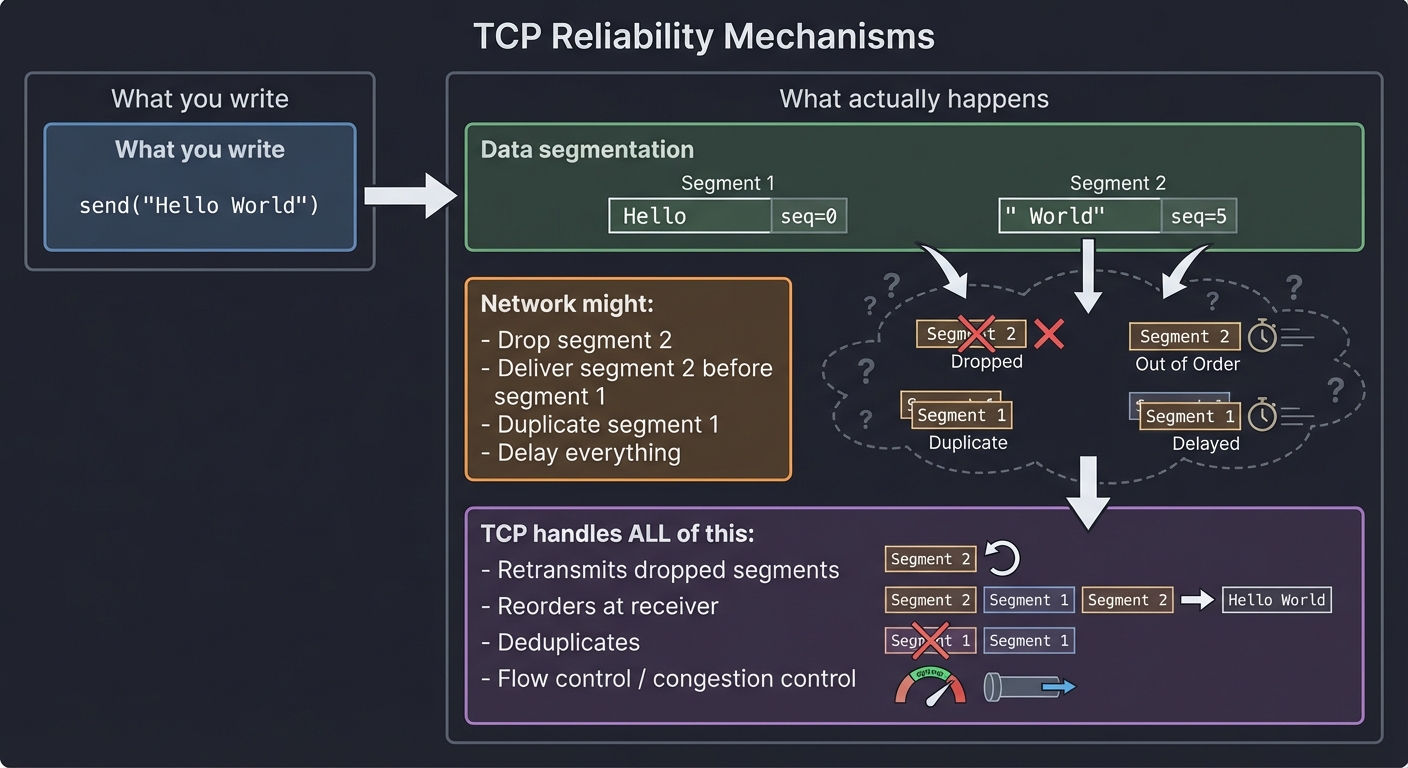

TCP: The Reliable Stream

TCP provides the illusion of a reliable, ordered byte stream. But it’s just an illusion built on unreliable packets:

What you write: What actually happens:

───────────────── ─────────────────────────

send("Hello World") → Segment 1: "Hello" + seq=0

Segment 2: " World" + seq=5

Network might:

- Drop segment 2

- Deliver segment 2 before segment 1

- Duplicate segment 1

- Delay everything

TCP handles ALL of this:

- Retransmits dropped segments

- Reorders at receiver

- Deduplicates

- Flow control / congestion control

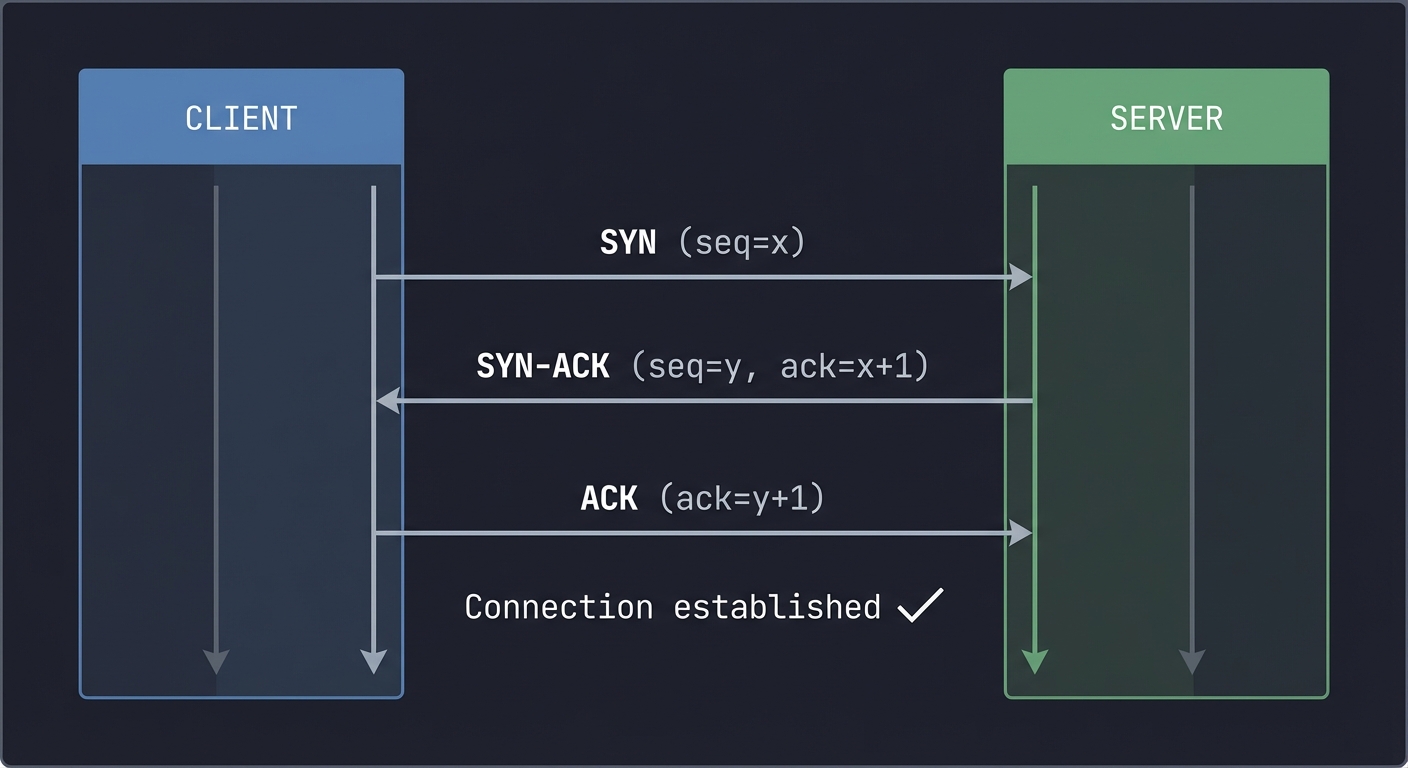

The Three-Way Handshake:

Client Server

│ │

│─────── SYN (seq=x) ──────────────→│

│ │

│←────── SYN-ACK (seq=y, ack=x+1) ──│

│ │

│─────── ACK (ack=y+1) ────────────→│

│ │

│ Connection established │

Why this matters for TCP servers: Your server’s listen() backlog is connections in SYN-RECEIVED state. accept() pulls from completed connections.

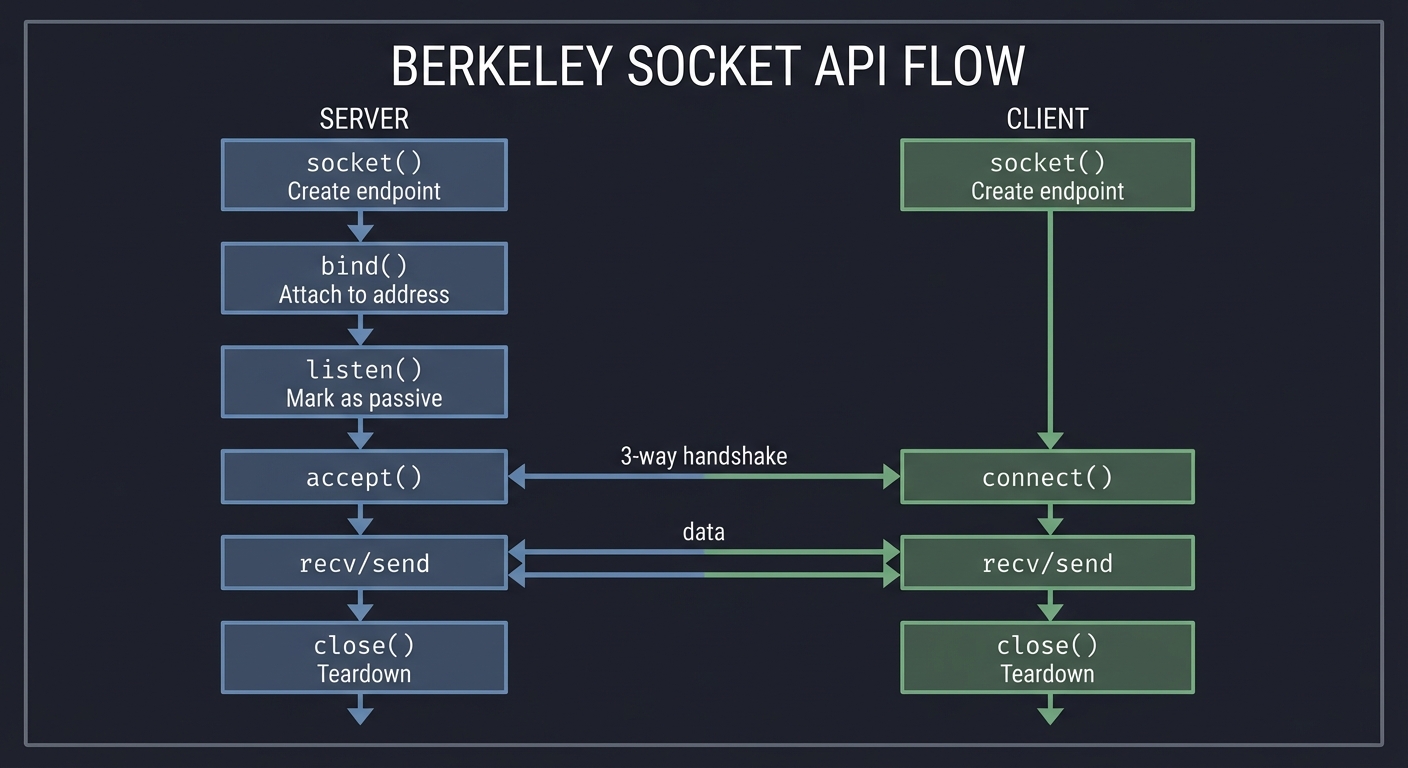

The Socket API

The Berkeley sockets API is the universal interface for network programming:

Server Client

─────── ──────

socket() Create endpoint socket()

↓ ↓

bind() Attach to address │

↓ │

listen() Mark as passive │

↓ │

accept() ←─── 3-way handshake ────→ connect()

↓ ↓

recv/send ←────── data ─────────→ recv/send

↓ ↓

close() Teardown close()

What each syscall does:

socket(): Create a file descriptor for network communicationbind(): Associate the socket with an address (IP + port)listen(): Convert socket from active to passive (server mode)accept(): Wait for and accept incoming connection (returns NEW socket)connect(): Initiate connection to a serversend()/recv(): Transfer data (orread()/write()- same thing for TCP)close(): Terminate the connection

Key insight: After accept(), you have TWO sockets: the original listening socket (still accepting new connections) and a new socket for THIS connection.

The Distributed Systems Reality

Once you have multiple machines, new problems emerge:

The Eight Fallacies of Distributed Computing (Peter Deutsch):

─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

1. The network is reliable ← It will fail

2. Latency is zero ← It's measurable and variable

3. Bandwidth is infinite ← It's finite and shared

4. The network is secure ← Assume hostile actors

5. Topology doesn't change ← Machines come and go

6. There is one administrator ← Multiple teams, policies

7. Transport cost is zero ← Cloud bills prove otherwise

8. The network is homogeneous ← Mix of protocols, hardware

Why this matters for Raft: You cannot assume messages arrive, arrive in order, or arrive once. You must handle all failure modes.

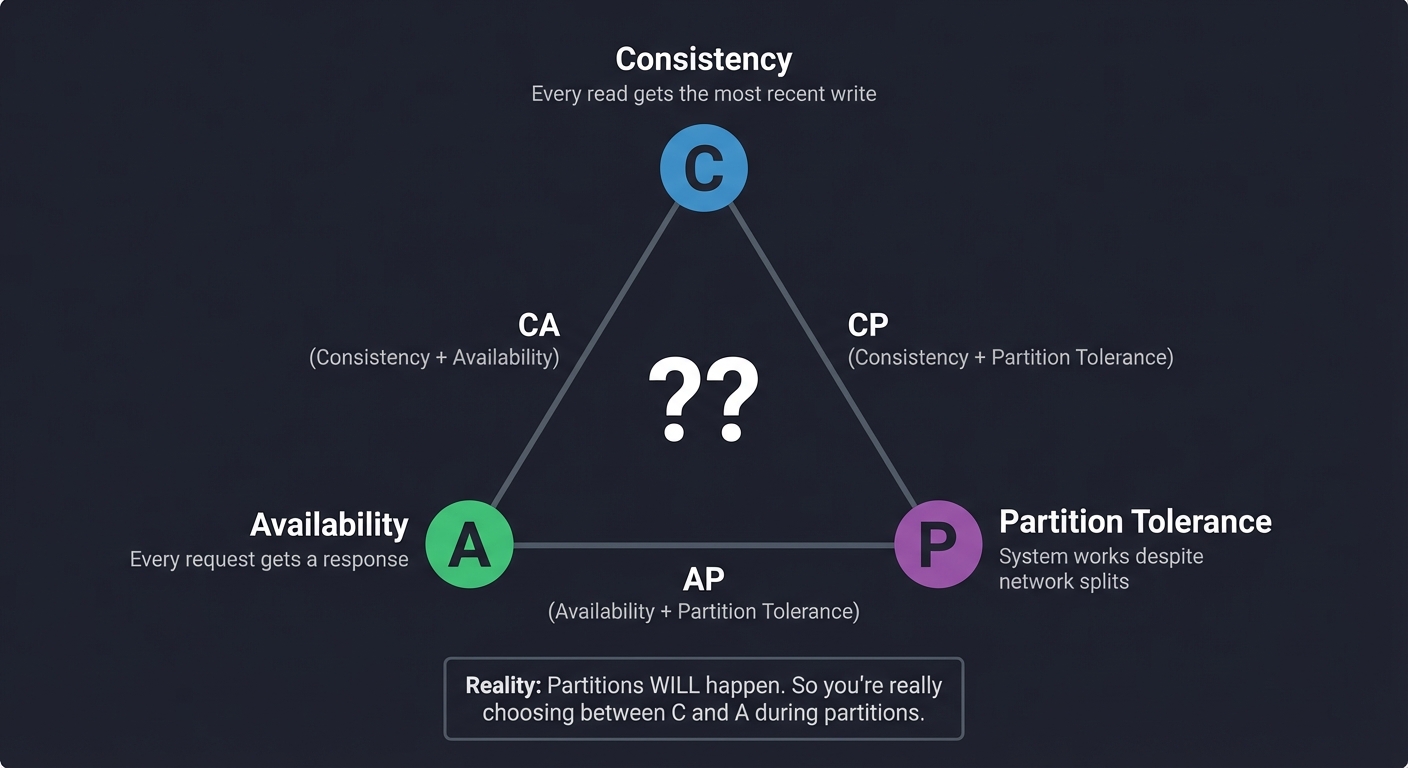

The CAP Theorem

You can only have two of three properties:

Consistency

/\

/ \

/ \

/ \

/ ?? \

/ \

/____________\

Availability Partition

Tolerance

- Consistency: Every read gets the most recent write

- Availability: Every request gets a response

- Partition Tolerance: System works despite network splits

Reality: Partitions WILL happen. So you’re really choosing between C and A during partitions.

Why this matters for Raft: Raft chooses Consistency. During a partition, the minority side CANNOT accept writes (no availability). The majority side continues (linearizable reads/writes).

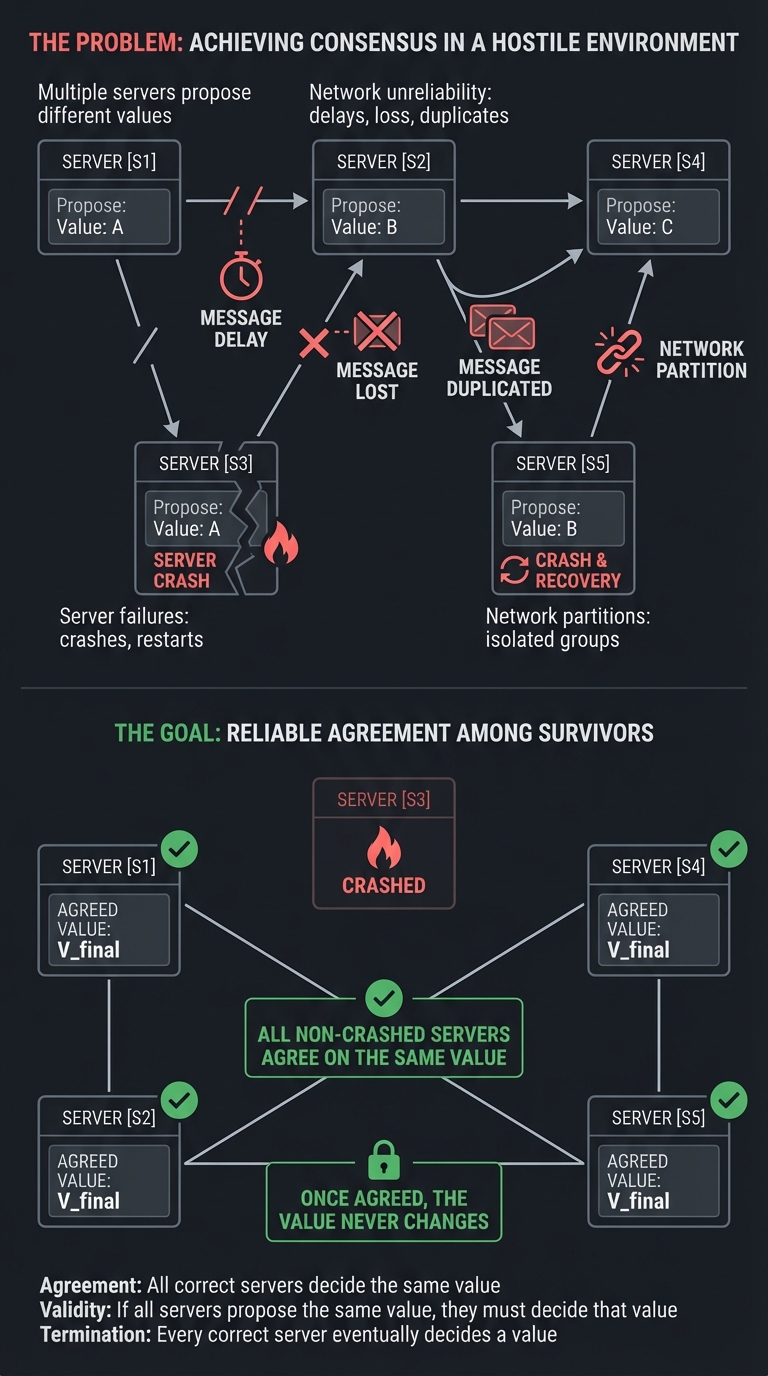

Consensus: The Fundamental Problem

How do N machines agree on a value, even when some might fail or be slow?

The Problem:

─────────────

5 servers, each might propose a value

Messages might be delayed, lost, duplicated

Some servers might crash and recover

Network might partition

The Goal:

─────────

All non-crashed servers eventually agree on THE SAME VALUE

Once agreed, the value never changes

Raft’s approach (simplified):

- Leader Election: One server becomes leader for a “term”

- Log Replication: Leader receives writes, replicates to followers

- Commitment: When majority have the entry, it’s “committed”

- Safety: Only servers with all committed entries can become leader

Deep Dive Reading: Networks & Distribution

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Socket programming | The Linux Programming Interface Ch. 56-61 - Michael Kerrisk |

| TCP/IP protocol | TCP/IP Illustrated, Volume 1 Ch. 1-24 - W. Richard Stevens |

| HTTP protocol | HTTP: The Definitive Guide Ch. 1-5 - David Gourley |

| Distributed systems intro | Designing Data-Intensive Applications Ch. 1-2 - Martin Kleppmann |

| Replication | Designing Data-Intensive Applications Ch. 5 - Martin Kleppmann |

| Consensus | Designing Data-Intensive Applications Ch. 9 - Martin Kleppmann |

| The Raft paper | “In Search of an Understandable Consensus Algorithm” - Ongaro & Ousterhout |

| Load balancing | Building Microservices, 2nd Ed Ch. 11 - Sam Newman |

Pillar 3: Storage & Persistence

Projects: Key-Value Store (Project 3), Git Objects (Project 10)

The Big Picture: How Data Survives

When you turn off the power, RAM is gone. Everything you want to keep must be written to disk. But disks are slow and have strange characteristics.

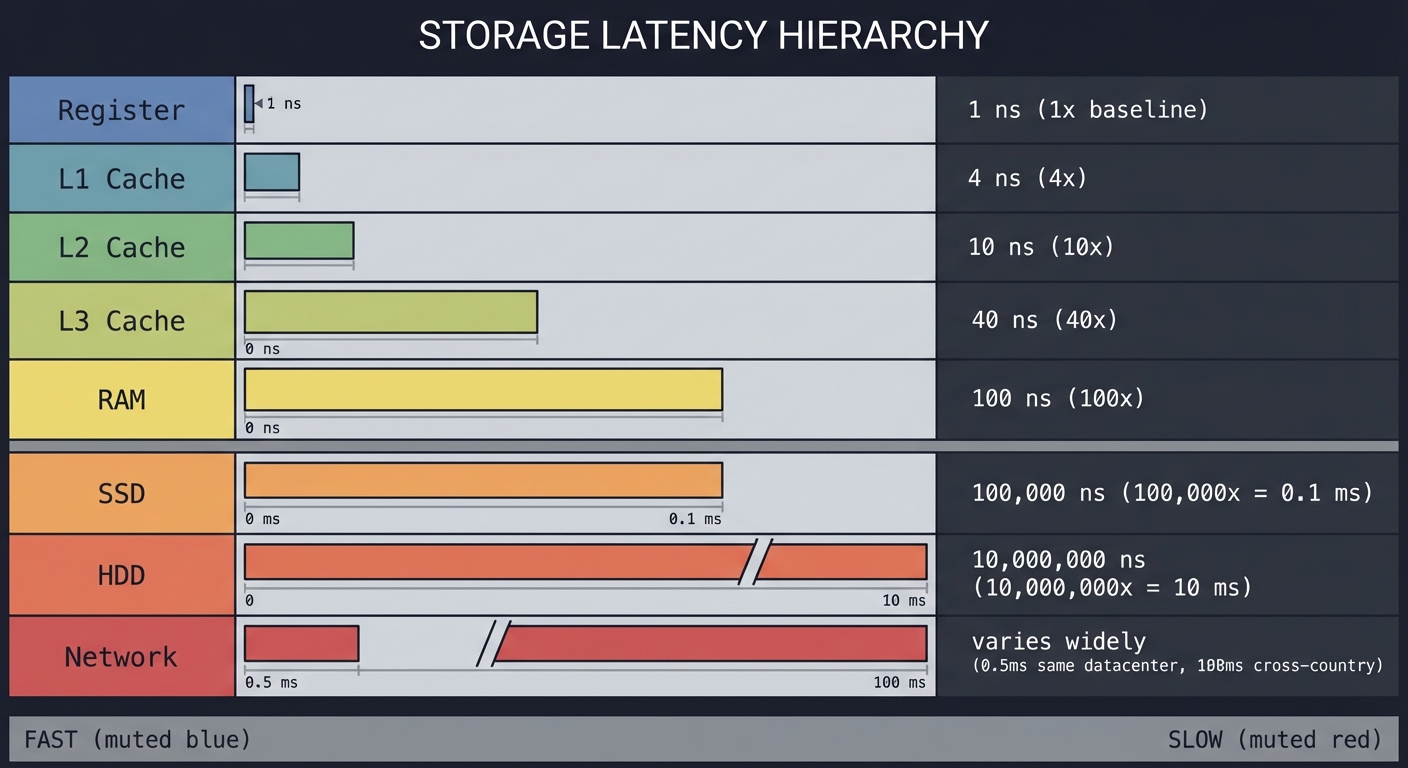

The Storage Hierarchy

Register ─→ 1 ns (1x)

L1 Cache ─→ 4 ns (4x)

L2 Cache ─→ 10 ns (10x)

L3 Cache ─→ 40 ns (40x)

RAM ─→ 100 ns (100x)

SSD ─→ 100,000 ns (100,000x = 0.1 ms)

HDD ─→ 10,000,000 ns (10,000,000x = 10 ms)

Network ─→ varies widely (0.5ms same datacenter, 100ms cross-country)

Key insight: SSD is 1000x slower than RAM. This is why databases don’t just write everything to disk for every operation—they batch, cache, and use clever data structures.

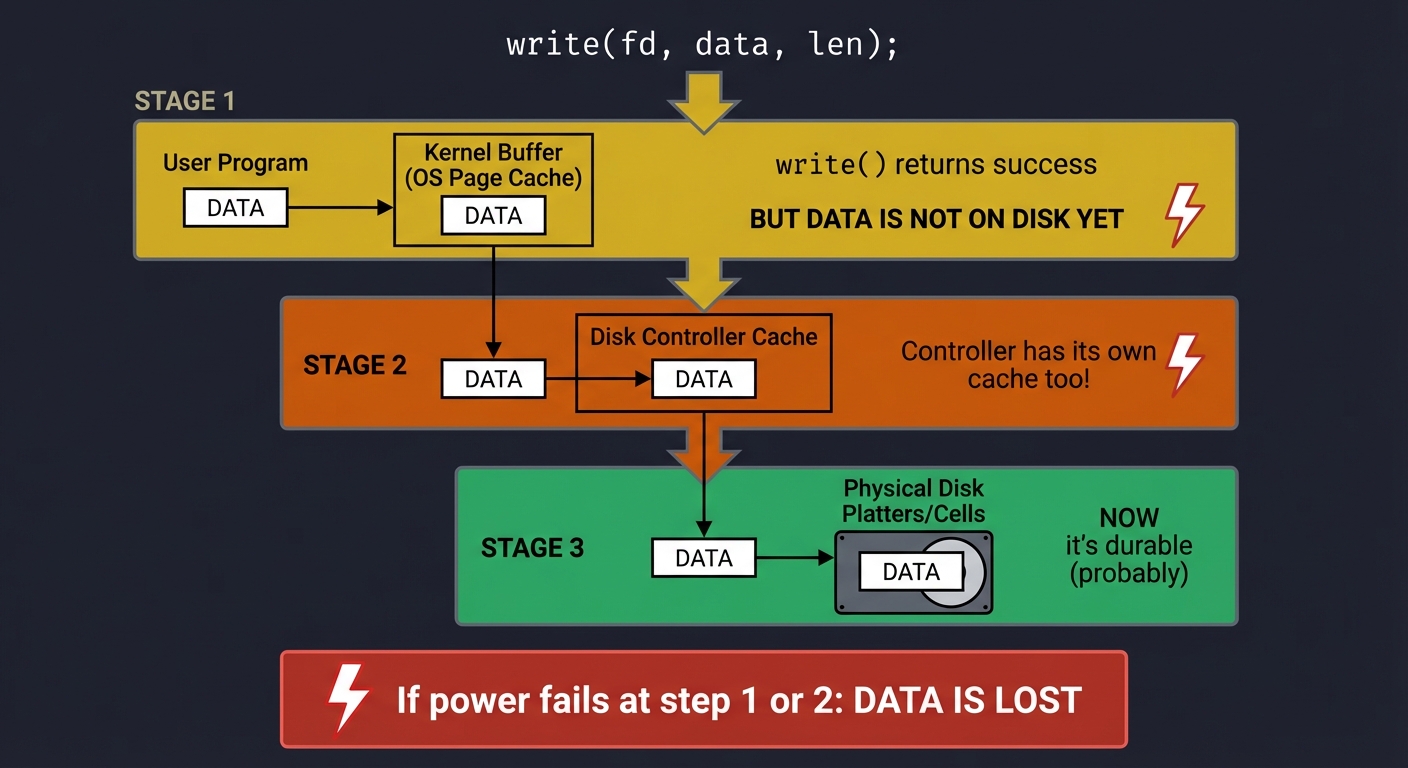

The Durability Problem

When is data “really” saved?

Your write call:

─────────────────

write(fd, data, len);

What actually happens:

─────────────────────

1. Data goes to kernel buffer (OS page cache)

└─ "write() returns success" - BUT DATA IS NOT ON DISK YET

2. Kernel eventually flushes to disk controller

└─ Controller has its own cache too!

3. Controller writes to actual disk platters/cells

└─ NOW it's durable (probably)

If power fails at step 1 or 2: DATA IS LOST

The solution: fsync()

write(fd, data, len); // Data in kernel buffer

fsync(fd); // WAIT until data is on physical media

// (or at least, controller says it is)

Why this matters for key-value stores: Every write must be durable before you tell the client “success.” Otherwise, you lose data on crash.

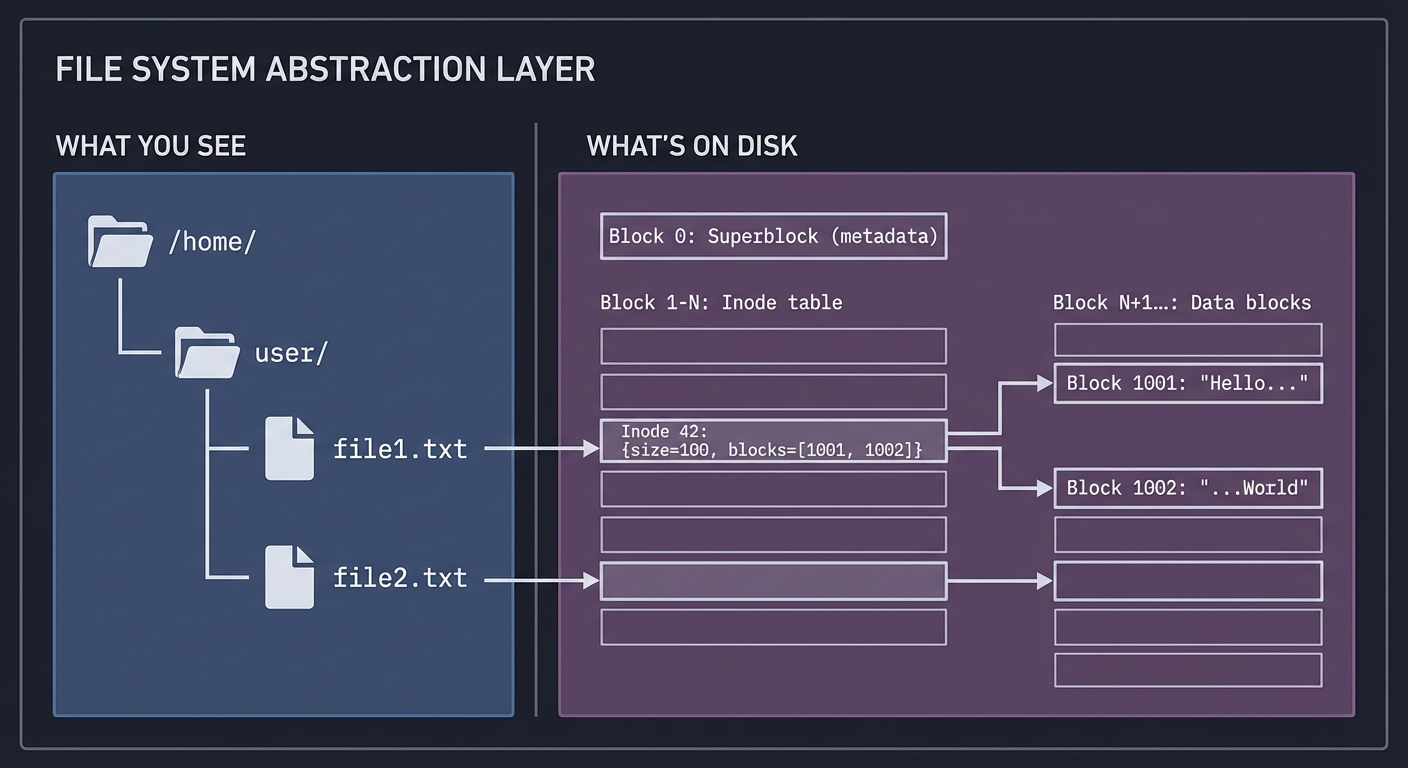

File Systems: The Abstraction Layer

File systems provide the abstraction of “files” and “directories” over raw disk blocks:

What you see: What's on disk:

──────────────── ───────────────────

/home/ Block 0: Superblock (metadata)

├── user/ Block 1-N: Inode table

│ ├── file1.txt Block N+1...: Data blocks

│ └── file2.txt

Inode 42: {size=100, blocks=[1001, 1002]}

Block 1001: "Hello..."

Block 1002: "...World"

Key concepts:

- Inode: Metadata about a file (size, permissions, block locations)

- Directory: A file that maps names → inode numbers

- Block: The unit of disk I/O (typically 4KB)

Why this matters for Git: Git stores objects as files. Each object is named by its SHA-1 hash and stored in .git/objects/XX/XXXX....

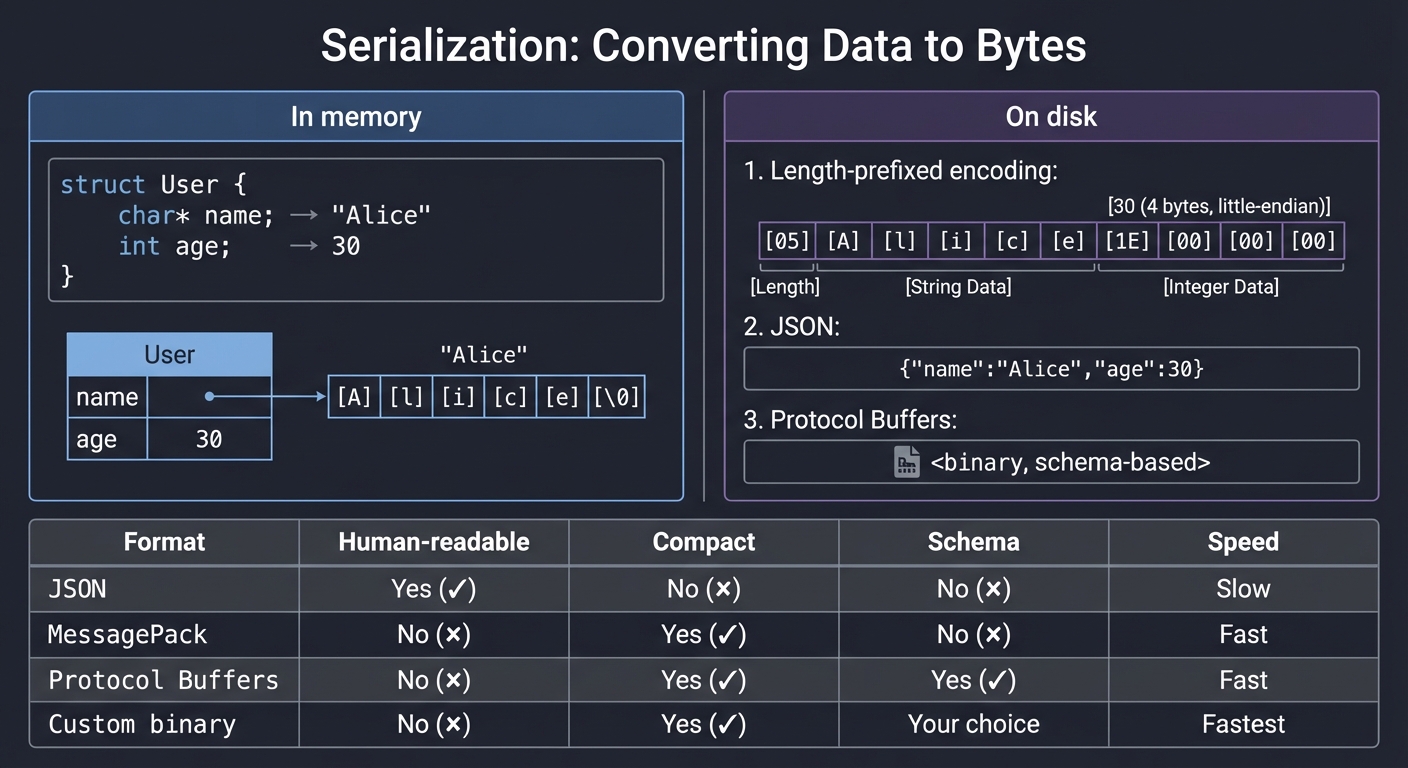

Serialization: Bytes to Structure and Back

To store data, you must convert it to bytes. To read it back, you must parse bytes into data:

In memory: On disk (one option):

────────── ────────────────────

struct User { Length-prefixed encoding:

char* name; → "Alice" ┌───────┬───────────┬───────┬────┐

int age; → 30 │05│Alice│ 30 (4 bytes, little-endian)│

} └───────┴───────────┴───────┴────┘

Or JSON:

{"name":"Alice","age":30}

Or Protocol Buffers:

<binary, schema-based>

Trade-offs: | Format | Human-readable | Compact | Schema | Speed | |——–|—————|———|——–|——-| | JSON | Yes | No | No | Slow | | MessagePack | No | Yes | No | Fast | | Protocol Buffers | No | Yes | Yes | Fast | | Custom binary | No | Yes | Your choice | Fastest |

Why this matters for key-value stores: You choose a format. Git uses a custom format. Databases often use custom binary formats for speed.

Data Structures for Storage

RAM data structures don’t work well on disk. You need disk-optimized structures:

Hash Tables:

In-memory hash table:

- O(1) lookup

- But: entire table must be in RAM

- No range queries

On-disk hash table (like Bitcask):

- Store values in append-only log

- Keep hash(key) → file_offset in RAM

- O(1) lookup, but index must fit in RAM

B-Trees:

Why B-trees for disk?

- Each node = one disk block (4KB)

- Minimize disk reads (shallow tree)

- Range queries work (sorted within nodes)

Height of B-tree with branching factor 1000:

- 1 billion keys = 3 levels = 3 disk reads!

Log-Structured Merge Trees (LSM):

Write-optimized structure (used by LevelDB, RocksDB):

1. Writes go to in-memory buffer (memtable)

2. When full, flush to sorted disk file (SSTable)

3. Background compaction merges SSTables

4. Reads check memtable, then SSTables (newest first)

Trade-off: Fast writes, slower reads, background work

Why this matters:

- Key-Value Store: You’ll likely start with a hash index, maybe progress to LSM

- Git Objects: Uses content-addressing (hash of content = filename), with pack files for efficiency

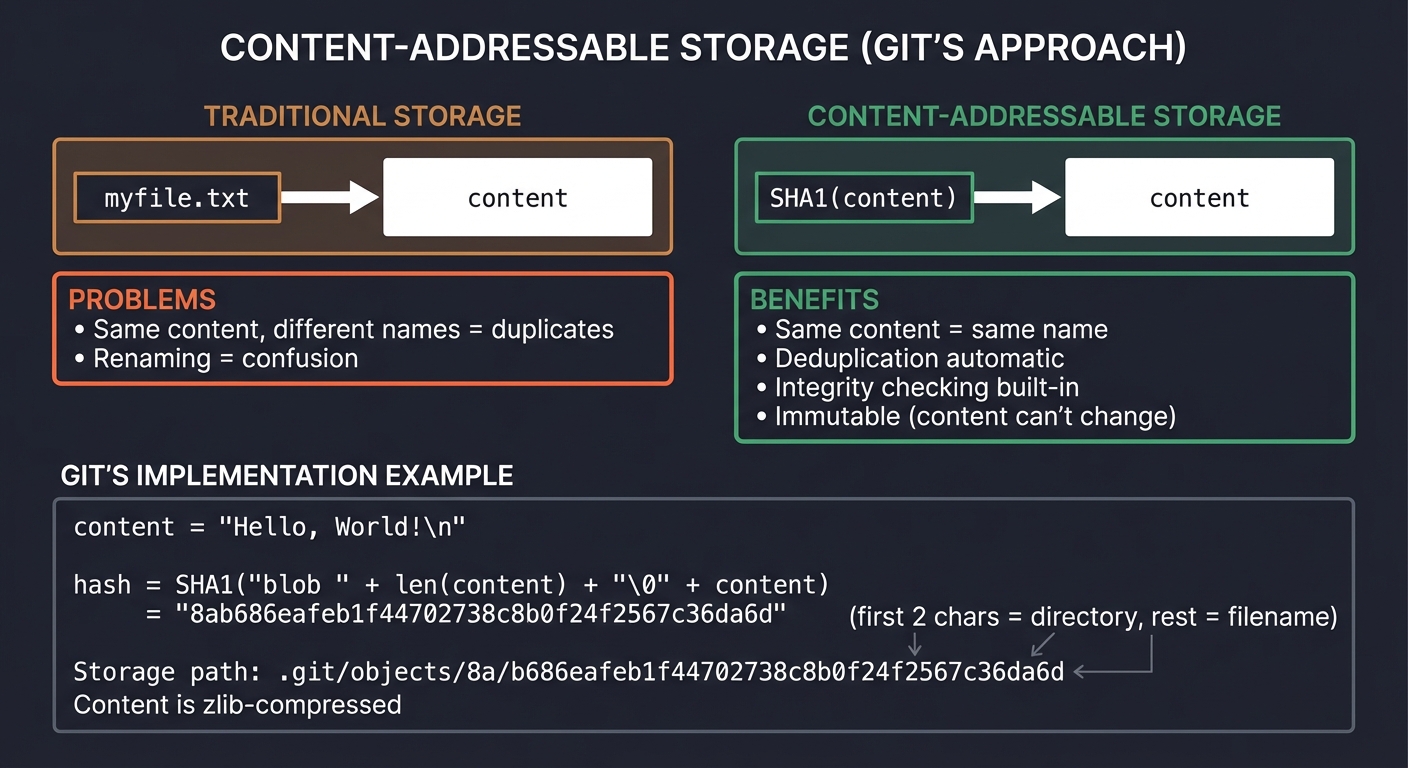

Content-Addressable Storage

Git’s brilliant insight: name files by their content hash.

Traditional storage: Content-addressable storage:

─────────────────── ────────────────────────────

"myfile.txt" → content SHA1(content) → content

Problems: Benefits:

- Same content, different - Same content = same name

names = duplicates - Deduplication automatic

- Renaming = confusion - Integrity checking built-in

- Immutable (content can't change)

How Git uses this:

# Store a file

content = "Hello, World!\n"

hash = SHA1("blob " + len(content) + "\0" + content)

= "8ab686eafeb1f44702738c8b0f24f2567c36da6d"

# Store in .git/objects/8a/b686eafeb1f44702738c8b0f24f2567c36da6d

# (first 2 chars = directory, rest = filename)

# Content is zlib-compressed

Deep Dive Reading: Storage & Persistence

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| File systems | Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces Ch. 36-42 - Arpaci-Dusseau |

| File I/O in C | The C Programming Language Ch. 7 - Kernighan & Ritchie |

| fsync and durability | The Linux Programming Interface Ch. 13 - Michael Kerrisk |

| Serialization | Designing Data-Intensive Applications Ch. 4 - Martin Kleppmann |

| Storage engines | Designing Data-Intensive Applications Ch. 3 - Martin Kleppmann |

| B-trees | Algorithms, Fourth Edition Section 3.3 - Sedgewick & Wayne |

| Git internals | Pro Git Ch. 10 - Scott Chacon (free online) |

| Content-addressing | “The Git Parable” by Tom Preston-Werner (blog post) |

Pillar 4: Abstraction & Languages

Projects: Containers (Project 5), Interpreter (Project 6), Mini-React (Project 9)

The Big Picture: Building Higher-Level Systems

The first three pillars are about understanding “what’s really happening.” This pillar is about building new abstractions on top of existing ones.

Abstraction: The Fundamental Tool

Computing progresses by building abstractions:

Level 5: Your application

↓ uses

Level 4: Framework (React, Django)

↓ uses

Level 3: Language runtime (JavaScript engine, Python interpreter)

↓ uses

Level 2: Operating system (Linux, Windows)

↓ uses

Level 1: Hardware (CPU, RAM, Disk)

↓ is

Level 0: Physics (electrons, transistors)

Key insight: Each level hides complexity from the level above. When you build an interpreter, you ARE level 3. When you build a framework, you ARE level 4.

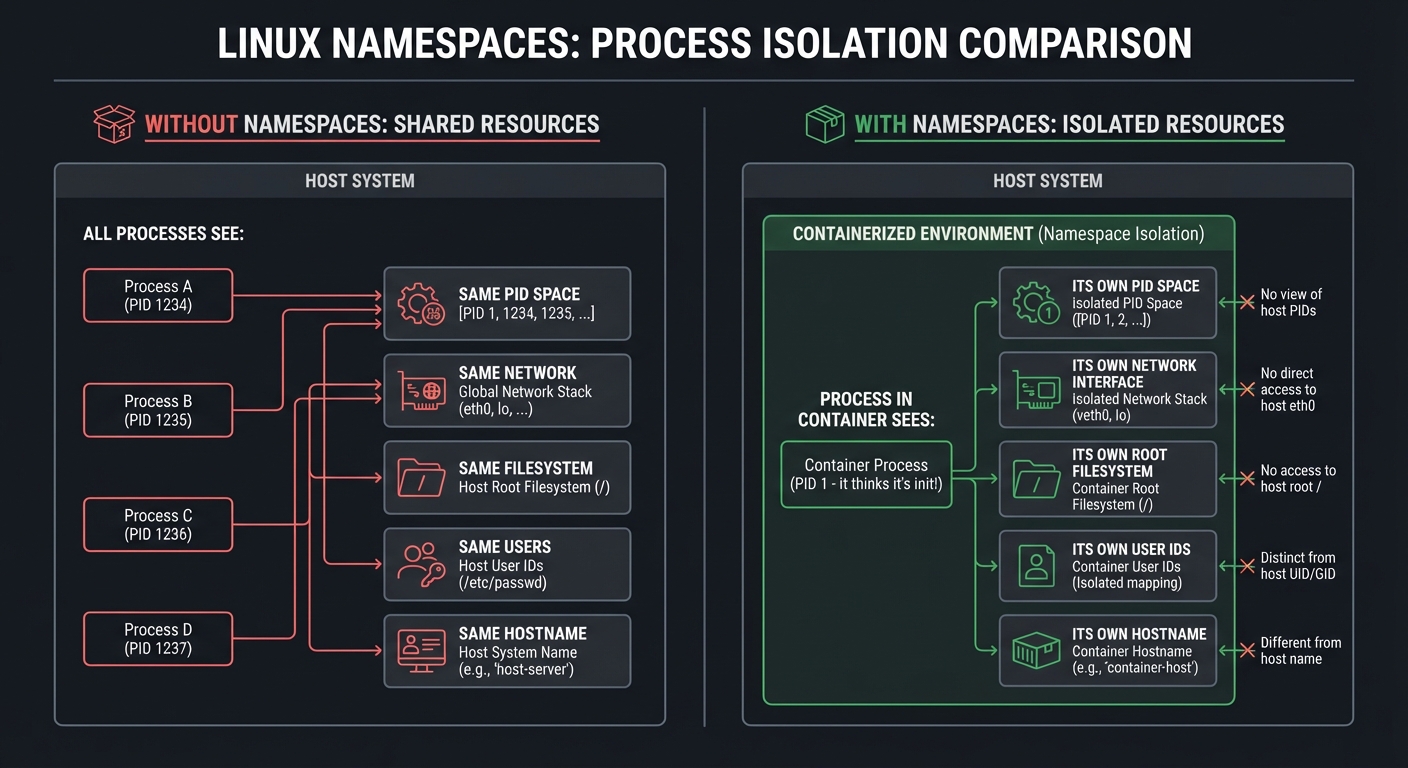

Linux Namespaces: Isolation Without Virtualization

Containers aren’t VMs. They’re just processes with isolated views of system resources:

Without namespaces: With namespaces:

────────────────── ─────────────────

All processes see: Process in container sees:

- Same PID space - PID 1 (it thinks it's init!)

- Same network - Its own network interface

- Same filesystem - Its own root filesystem

- Same users - Its own user IDs

- Same hostname - Its own hostname

The namespace types: | Namespace | What it isolates | |———–|—————–| | PID | Process IDs (container sees PID 1) | | NET | Network interfaces, ports, routing tables | | MNT | Filesystem mount points | | UTS | Hostname and domain name | | IPC | Inter-process communication (semaphores, message queues) | | USER | User and group IDs | | CGROUP | Which cgroup the process sees |

How to create namespaces:

// Clone with new namespaces

clone(child_func, stack,

CLONE_NEWPID | CLONE_NEWNS | CLONE_NEWNET | SIGCHLD,

arg);

// Or unshare from parent

unshare(CLONE_NEWPID | CLONE_NEWNS);

Why this matters: Docker is essentially: namespaces (isolation) + cgroups (resource limits) + union filesystem (image layers) + a nice CLI.

Cgroups: Resource Limits

Namespaces isolate what you can see. Cgroups limit what you can use:

# Create a cgroup

mkdir /sys/fs/cgroup/mycontainer

# Set memory limit to 100MB

echo 100000000 > /sys/fs/cgroup/mycontainer/memory.max

# Set CPU limit to 50% of one core

echo "50000 100000" > /sys/fs/cgroup/mycontainer/cpu.max

# Add a process to this cgroup

echo $PID > /sys/fs/cgroup/mycontainer/cgroup.procs

What you can limit:

- Memory (hard limit, soft limit)

- CPU (time quota, shares)

- I/O (bandwidth, IOPS)

- PIDs (prevent fork bombs)

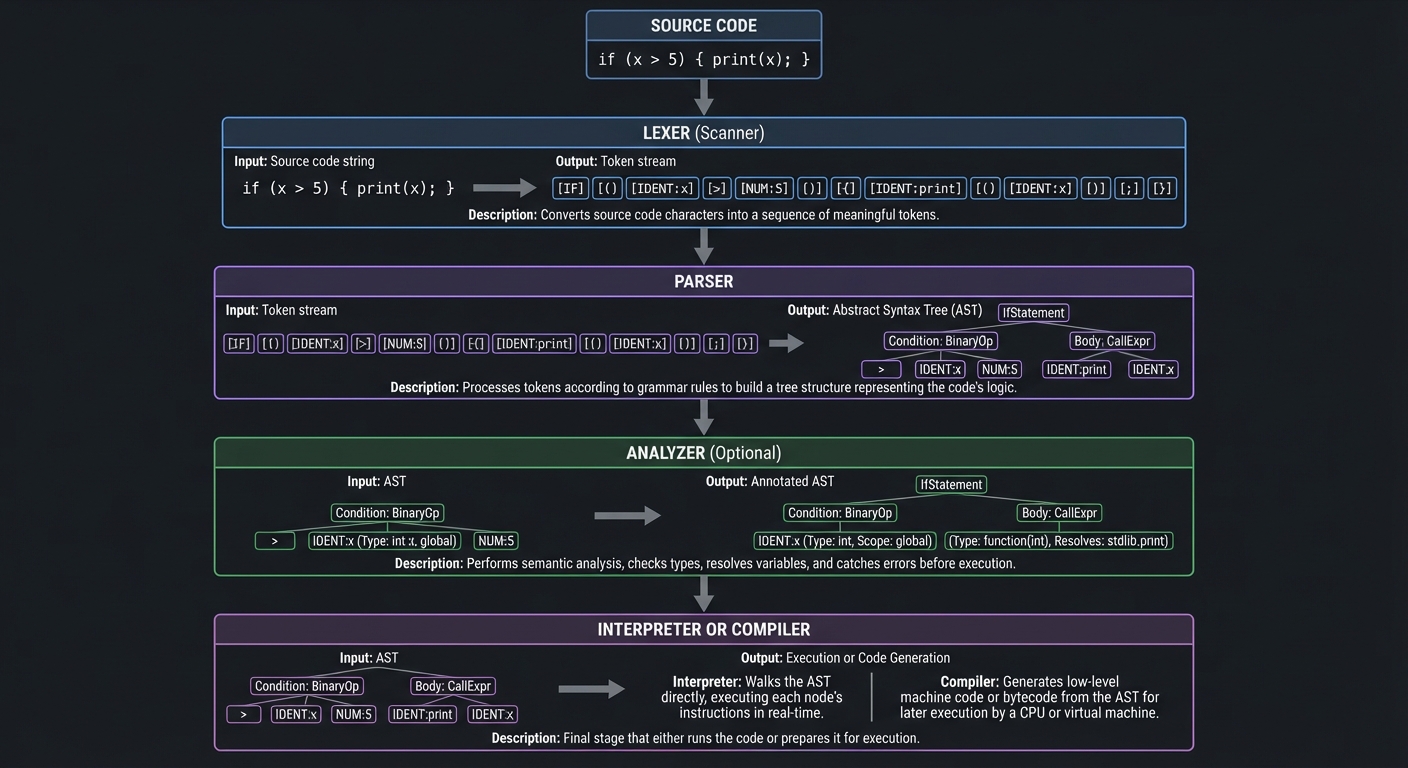

Language Implementation: The Pipeline

Every interpreter/compiler follows a similar pipeline:

Source Code

│

▼

┌─────────────────┐

│ Lexer │ "if (x > 5) { print(x); }"

│ (Scanner) │ ↓

└────────┬────────┘ [IF] [(] [IDENT:x] [>] [NUM:5] [)] [{] [IDENT:print] ...

│

▼

┌─────────────────┐

│ Parser │ Tokens → Abstract Syntax Tree

└────────┬────────┘ ↓

│ ┌─────────────────┐

│ │ IfStatement │

│ │ ┌───────┬────┐ │

│ │ │ > x 5 │body│ │

│ │ └───────┴────┘ │

│ └─────────────────┘

▼

┌─────────────────┐

│ Analyzer │ Check types, resolve variables

│ (optional) │ Catch errors before execution

└────────┬────────┘

│

▼

┌─────────────────┐

│ Interpreter │ Walk the tree, execute each node

│ OR │ ↓

│ Compiler │ Generate machine code / bytecode

└─────────────────┘

Key concepts:

- Token: The smallest unit of meaning (keyword, identifier, operator)

- AST: Tree structure representing program structure

- Environment: Where variables are stored (symbol table)

- Scope: Rules for variable visibility (lexical scoping)

Why closures are interesting:

function makeCounter() {

let count = 0; // This variable...

return function() {

count++; // ...is captured here

return count;

};

}

let counter = makeCounter();

counter(); // 1

counter(); // 2

A closure is a function + the environment where it was defined. When makeCounter returns, count should be “dead,” but the inner function keeps it alive.

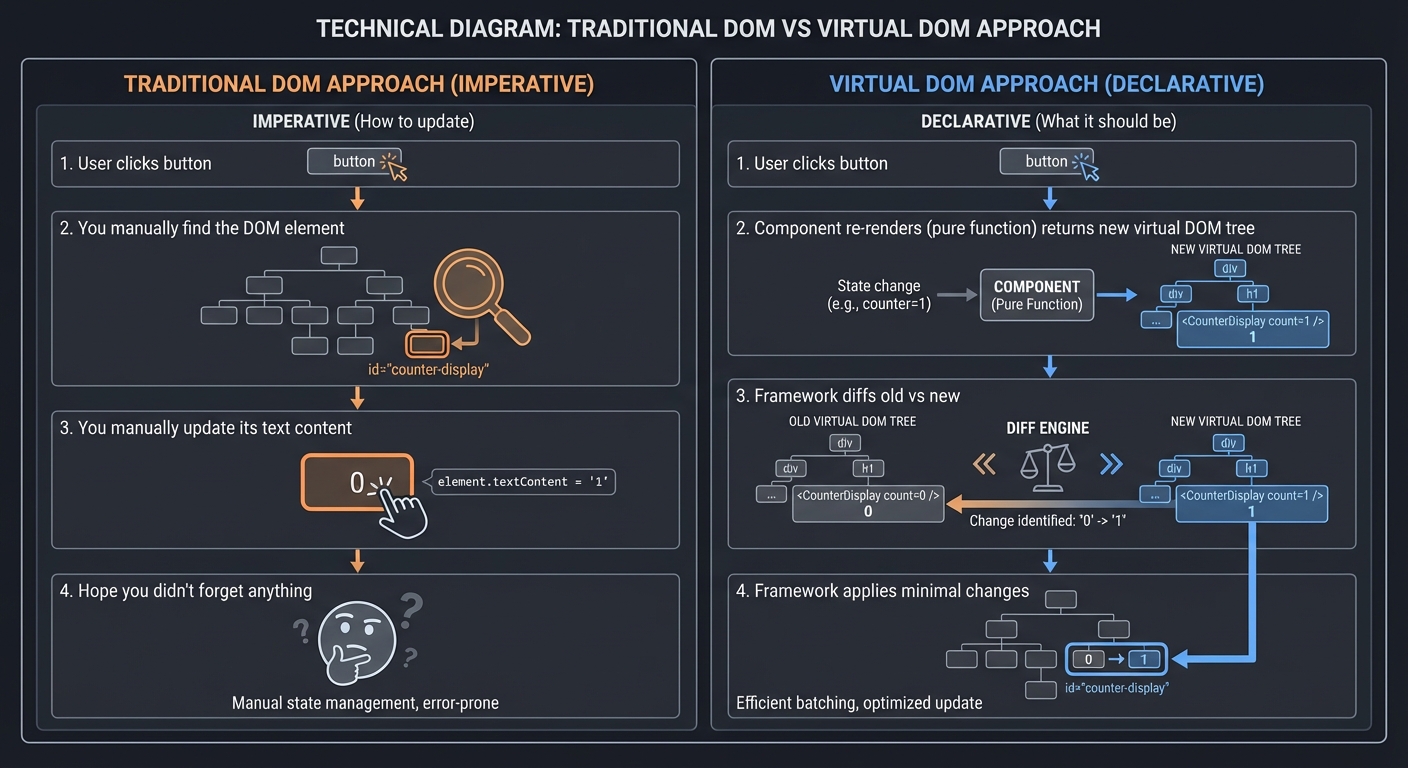

The Virtual DOM and Reconciliation

React’s key insight: describe what the UI should look like, let the framework figure out how to update it.

Traditional DOM: Virtual DOM approach:

──────────────── ───────────────────

1. User clicks button 1. User clicks button

2. You manually find 2. Component re-renders (pure function)

the DOM element returns new virtual DOM tree

3. You manually update 3. Framework diffs old vs new

its text content 4. Framework applies minimal changes

4. Hope you didn't

forget anything

Imperative Declarative

(how to update) (what it should be)

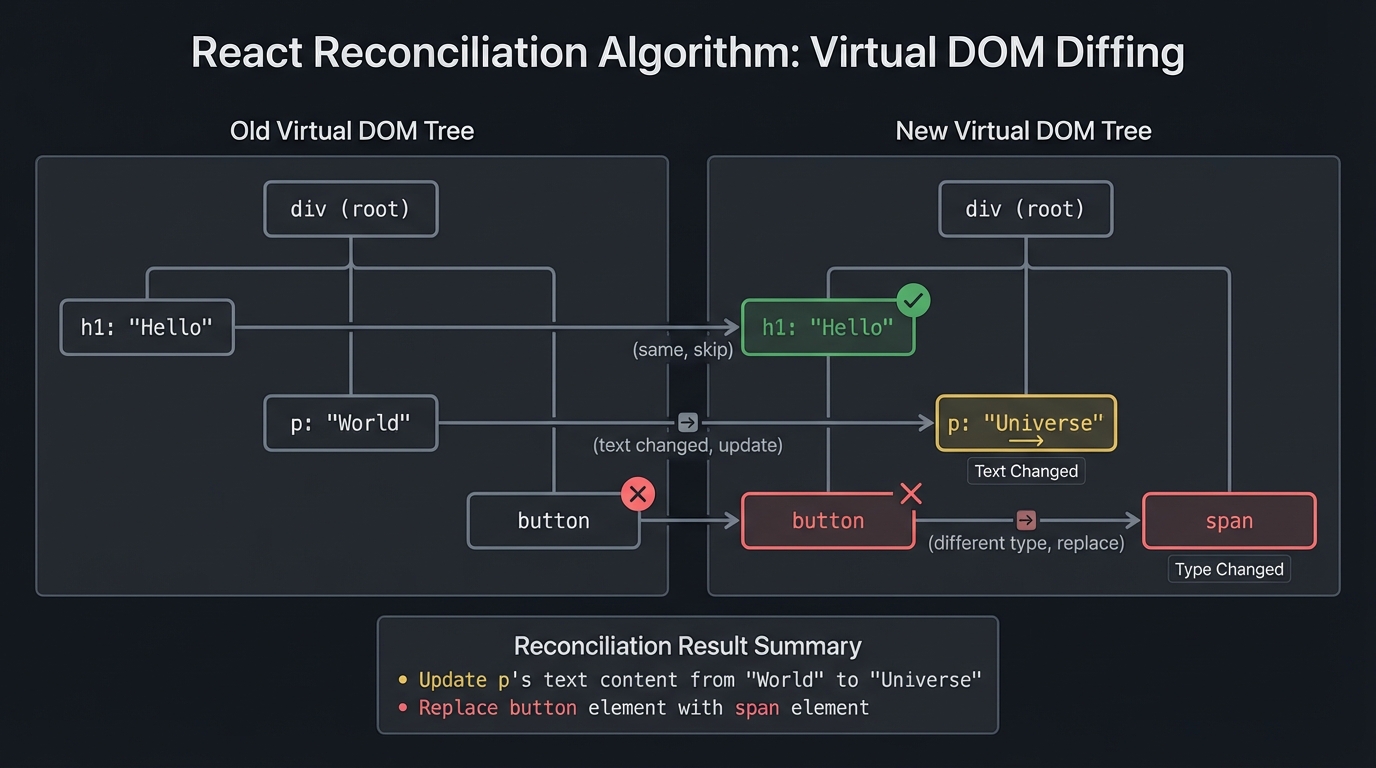

The reconciliation algorithm:

Old tree: New tree:

───────── ─────────

div div

├── h1: "Hello" ├── h1: "Hello" (same, skip)

├── p: "World" ├── p: "Universe" (text changed, update)

└── button └── span (different type, replace)

Result: Update p's text, replace button with span

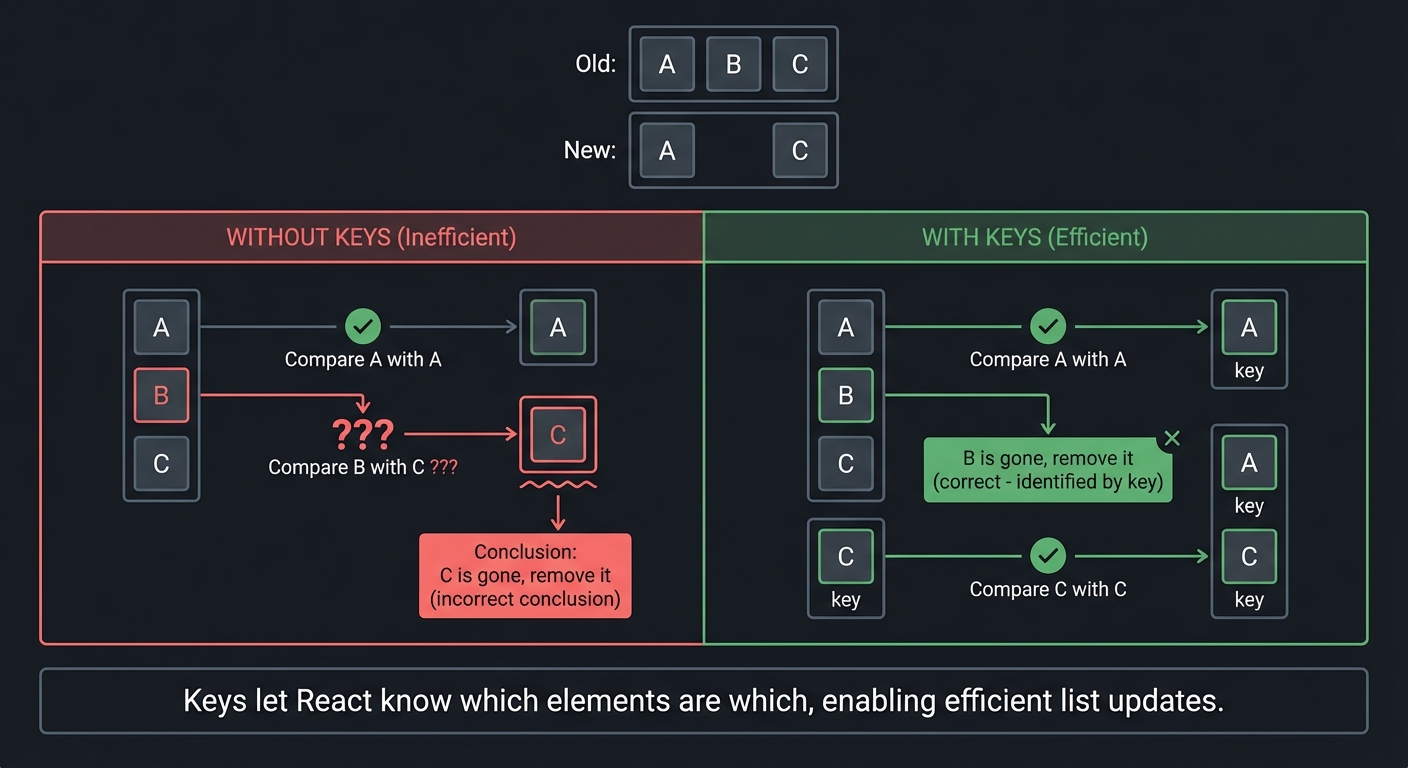

Why keys matter for lists:

Old: [A, B, C] New: [A, C]

Without keys: With keys:

- Compare A with A ✓ - Compare A with A ✓

- Compare B with C ??? - B is gone, remove it

- C is gone, remove it - Compare C with C ✓

Keys let React know which elements are which,

enabling efficient list updates.

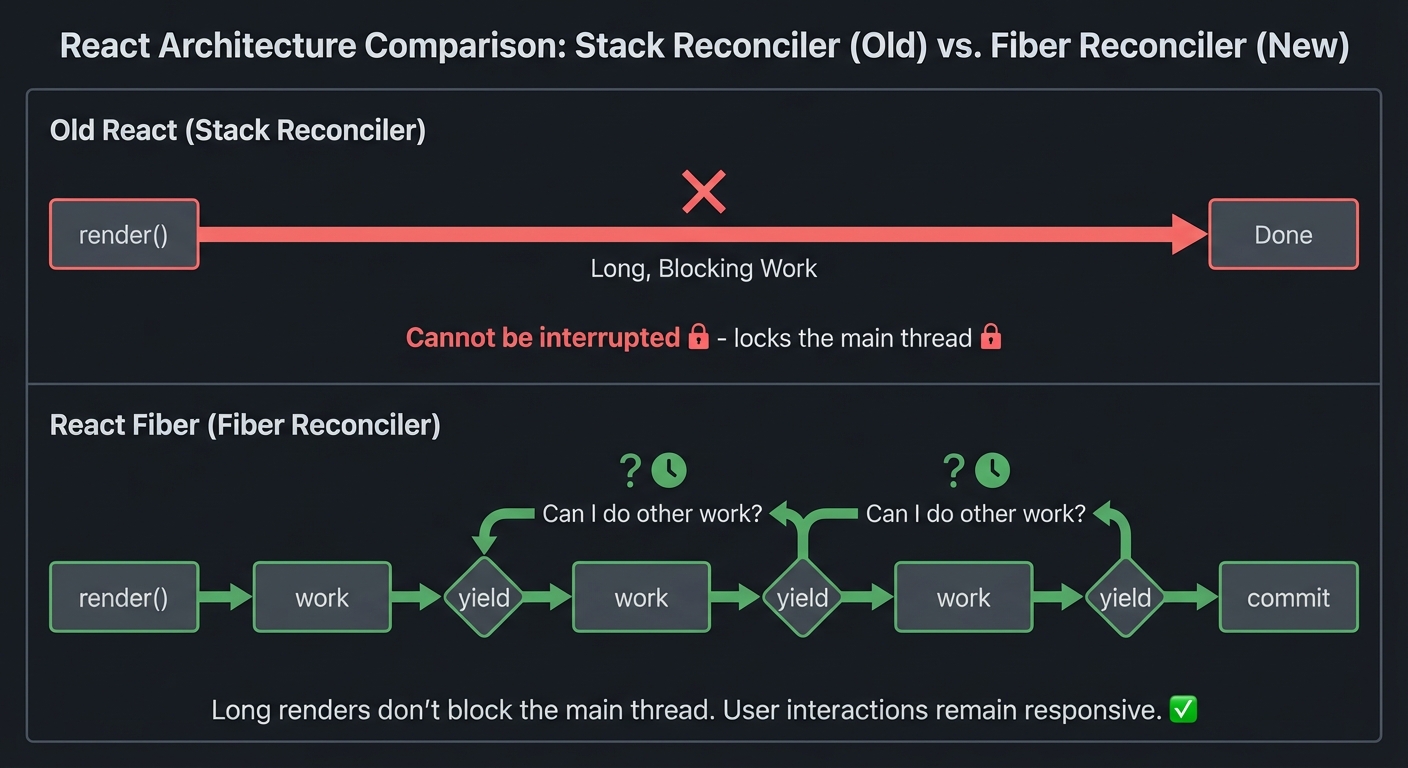

The Fiber Architecture: React can pause rendering and resume later:

Old React:

─────────

render() ─────────────────────────────────→ Done

(cannot be interrupted)

Fiber React:

────────────

render()→work→yield→work→yield→work→yield→commit

↑ ↑

└──────────┴── "Can I do other work?"

Why this matters: Long renders don’t block the main thread. User interactions remain responsive.

Deep Dive Reading: Abstraction & Languages

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Linux namespaces | The Linux Programming Interface Ch. 28 - Michael Kerrisk |

| Cgroups v2 | How Linux Works, 3rd Edition Ch. 8 - Brian Ward |

| Container internals | “Containers from Scratch” talk by Liz Rice (video) |

| Lexical analysis | Crafting Interpreters Ch. 4 - Bob Nystrom |

| Parsing | Crafting Interpreters Ch. 5-6 - Bob Nystrom |

| Interpreters | Crafting Interpreters Ch. 7-13 - Bob Nystrom |

| Closures | Crafting Interpreters Ch. 11 - Bob Nystrom |

| React Fiber | “React Fiber Architecture” by Andrew Clark (GitHub doc) |

| Virtual DOM | “Build Your Own React” by Rodrigo Pombo (pomb.us) |

Concept Summary Table

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize | Projects |

|---|---|---|

| Memory as bytes | Memory is just numbered boxes. Everything is bytes with interpretation layered on top. | malloc, Lock-Free |

| The stack | Automatic, fast, limited. Local variables live here. Grows down. LIFO. | malloc |

| The heap | Manual, flexible, fragmentation-prone. malloc/free. You control lifetime. | malloc |

| Pointers as addresses | A pointer is just a number that happens to be an address. Arithmetic follows type sizes. | malloc, Lock-Free |

| Atomics & ordering | CPUs reorder operations. Memory barriers enforce ordering. CAS is the primitive. | Lock-Free |

| Sockets | File descriptors for network communication. bind/listen/accept for servers. | TCP Server, Load Balancer |

| TCP semantics | Reliable, ordered byte stream. Built on unreliable packets. Three-way handshake. | TCP Server, Load Balancer |

| Distributed failure | Networks fail, machines crash, messages duplicate. Design for failure. | Raft, Load Balancer |

| Consensus | Agreement despite failures. Majority quorums. Terms/epochs prevent split-brain. | Raft |

| Durability | Data must hit disk before you confirm. fsync is your friend. | Key-Value Store |

| Serialization | Converting structures to bytes and back. Choose your format wisely. | Key-Value Store, Git |

| Content-addressing | Name things by their hash. Immutable, deduplicated, integrity-checked. | Git |

| Namespaces | Isolated views of system resources. The core of containerization. | Containers |

| Cgroups | Resource limits. Memory, CPU, I/O constraints. | Containers |

| Lexical analysis | Breaking source code into tokens. Regular languages. | Interpreter |

| Parsing | Building trees from token sequences. Context-free grammars. | Interpreter |

| Environments & scope | Where variables live. Lexical scoping. Closure capture. | Interpreter |

| Virtual DOM | Describe UI declaratively. Framework computes minimal updates. | Mini-React |

| Reconciliation | Diffing old and new trees. Keys for list stability. | Mini-React |

Prerequisites & Background Knowledge

Essential Prerequisites (Must Have)

Before starting these projects, you should have:

- Programming Fundamentals

- Proficiency in at least one systems language (C, C++, Rust, or Go preferred)

- Understanding of pointers, memory addresses, and manual memory management

- Ability to read and write multi-file programs

- Basic Systems Knowledge

- Familiarity with Linux/Unix command line

- Understanding of what a process is

- Basic knowledge of file descriptors and I/O

- Awareness that syscalls exist (even if you don’t know them all)

- Development Environment

- Linux machine (native, VM, or WSL2—macOS works for most projects)

- C compiler (gcc or clang)

- Text editor or IDE of choice

- Basic debugging tools (gdb/lldb, print statements)

Helpful But Not Required

You’ll learn these concepts through the projects, but prior exposure helps:

- Networking basics (what is TCP vs UDP, what is an IP address)

- Concurrency primitives (threads, mutexes, race conditions)

- Data structures (hash tables, trees, linked lists)

- How databases work at a high level

- Git usage (for the Git internals project)

- Web development basics (for TCP server and Mini-React)

Self-Assessment Questions

Check your readiness with these questions:

| Question | If you answered YES… |

|---|---|

| Can you explain what a pointer is and dereference one in code? | ✅ Ready for malloc, lock-free queue |

Do you know what fork() does? |

✅ Ready for containers |

| Have you written a program that opens and reads a file? | ✅ Ready for key-value store, Git |

| Do you understand what a TCP connection is (at least conceptually)? | ✅ Ready for load balancer, TCP server |

| Have you debugged a segmentation fault before? | ✅ You’ll survive the memory projects |

| Can you write a recursive function? | ✅ Ready for interpreter, Mini-React |

| Do you know what a hash function does? | ✅ Ready for Git, key-value store |

If you answered NO to most of these:

- Start with Projects 8 (TCP Server) or 6 (Interpreter)—they’re more forgiving

- Read “The C Programming Language” Chapters 1-6 first

- Consider taking a systems programming course before tackling malloc or Raft

Development Environment Setup

Minimum required tools:

# Check your C compiler

gcc --version || clang --version

# Install essential debugging tools

sudo apt install build-essential gdb valgrind # Ubuntu/Debian

brew install gcc gdb valgrind # macOS

# For networking projects

sudo apt install netcat-openbsd tcpdump wireshark

# For containers project (Linux only)

# No special tools needed—uses standard Linux syscalls

Recommended tools:

# AddressSanitizer support (better than valgrind in many cases)

# Use clang -fsanitize=address when compiling

# For Go projects

curl -L https://go.dev/dl/go1.21.linux-amd64.tar.gz | sudo tar -C /usr/local -xz

# For Rust projects

curl --proto '=https' --tlsv1.2 -sSf https://sh.rustup.rs | sh

# Code formatting

sudo apt install clang-format # For C/C++

Time Investment Expectations

Per-project time estimates:

| Project | Beginner | Intermediate | Advanced |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. malloc | 3-4 weeks | 2 weeks | 1 week |

| 2. Load Balancer | 2 weeks | 1 week | 3 days |

| 3. Key-Value Store | 2-3 weeks | 1-2 weeks | 1 week |

| 4. Raft | 4-6 weeks | 3-4 weeks | 2 weeks |

| 5. Containers | 2 weeks | 1 week | 3-4 days |

| 6. Interpreter | 3-4 weeks | 2 weeks | 1 week |

| 7. Lock-Free Queue | 3-4 weeks | 2-3 weeks | 1-2 weeks |

| 8. TCP Server | 1-2 weeks | 3-5 days | 2-3 days |

| 9. Mini-React | 2-3 weeks | 1-2 weeks | 3-5 days |

| 10. Mini Git | 1-2 weeks | 3-5 days | 2-3 days |

Total time commitment: 6-12 months if doing all 10 projects sequentially

These estimates assume:

- Working on this part-time (5-10 hours/week)

- Reading recommended chapters before coding

- Debugging and rewriting sections that don’t work

- Actually understanding, not just “getting it to compile”

Important Reality Check

These projects are HARD. That’s the point.

You will:

- ✅ Get stuck frequently

- ✅ Spend hours debugging strange behavior

- ✅ Rewrite entire sections when you realize your design was wrong

- ✅ Question whether you’re “smart enough” (you are—it’s just hard)

- ✅ Experience the satisfaction of finally understanding something deeply

You will NOT:

- ❌ Finish each project in a weekend (unless you already know the material)

- ❌ Write perfect code on the first try

- ❌ Understand everything immediately

- ❌ Find these as easy as following a tutorial

That’s okay. The struggle is where the learning happens.

If a project feels too easy, you’re probably not going deep enough. The goal isn’t to check boxes—it’s to genuinely understand the systems underneath.

Quick Start Guide: Your First 48 Hours

Feeling overwhelmed? Start here.

Day 1: Get Your Bearings (4 hours)

Morning: Pick Your First Project

Based on your background, start with:

- Have C experience? → Start with Project 1 (malloc) or Project 8 (TCP Server)

- More comfortable with Go/Rust? → Start with Project 2 (Load Balancer)

- Enjoy parsers/compilers? → Start with Project 6 (Interpreter)

- Want something visual? → Start with Project 9 (Mini-React) or Project 10 (Git)

- Just pick for me! → Start with Project 8 (TCP Server)—it’s the most forgiving

Afternoon: Read the Foundation

- Read the relevant “Pillar” section in this guide (30 minutes)

- Read the project’s “Core Question You’re Answering” section (5 minutes)

- Skim the recommended book chapter (1 hour)

- Read “Concepts You Must Understand First” and Google what you don’t know (1-2 hours)

End of Day 1: You should understand WHAT you’re building and WHY it matters, even if you don’t know HOW yet.

Day 2: Write Your First Line of Code (4 hours)

Morning: Minimal Viable Implementation

- Don’t try to build the full thing yet. Start with the absolute simplest version.

- malloc? Just use

sbrk()to grow heap and return pointers. No free yet. - Load balancer? Round-robin to 2 hardcoded backends. No health checks.

- TCP server? Accept one connection, echo back what’s sent, then exit.

- malloc? Just use

- Get it to compile and run (even if it doesn’t do much)

Afternoon: Make It “Work”

- Add ONE feature from the “Core Challenges” list

- Use the “Thinking Exercise” to trace what your code does

- Reference the “Hints in Layers”—start with Hint 1

End of Day 2: You should have a working (if incomplete) program that demonstrates you understand the core concept.

After 48 Hours: Iterate and Expand

Now that you have something working:

- Review the “Questions to Guide Your Design”—rethink your approach

- Read the interview questions—can you answer them now?

- Expand your implementation to handle the next challenge

- Use the debugging tools in “Tools for Understanding”

- When stuck, consult “Books That Will Help” for specific chapters

Key principle: Working code beats perfect code. Iterate toward correctness and completeness.

Recommended Project Order

If you’re doing multiple projects, follow this sequence:

Path 1: Systems Engineering Focus

- TCP Server (warm-up)

- malloc (understand memory)

- Lock-Free Queue (understand concurrency)

- Load Balancer (understand networking)

- Key-Value Store (understand storage)

- Raft (understand distribution)

- Containers (understand isolation)

Path 2: Language/Tools Focus

- Interpreter (understand execution)

- Mini-React (understand rendering)

- Git Objects (understand content addressing)

- TCP Server (understand protocols)

- Containers (understand namespaces)

Path 3: Interview Prep (Most Asked)

- TCP Server

- Load Balancer

- malloc

- Key-Value Store

- Raft

- Interpreter

Choose based on your goals, but finish one before starting another. Deep understanding beats broad surface knowledge.

Essential Reading Order

For maximum comprehension, read in this order before starting the projects:

Week 1: Foundations

- Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective Ch. 1-2

- What computers actually do, data representation

- The C Programming Language Ch. 5-6

- Pointers and structures (even if you know C, review this)

- Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces Ch. 1-6

- Virtualization fundamentals, what an OS does

Week 2: Memory & Processes

- Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective Ch. 9

- Virtual memory (critical for malloc, containers)

- The Linux Programming Interface Ch. 6-7

- Processes and memory allocation

- Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces Ch. 13-17

- Address spaces, memory API, free space management

Week 3: Networking

- The Linux Programming Interface Ch. 56-59

- Socket fundamentals

- TCP/IP Illustrated, Volume 1 Ch. 1-3, 12-24

- TCP protocol details (or skim if time-limited)

- Designing Data-Intensive Applications Ch. 1-2

- Distributed systems mindset

Week 4: Distribution & Storage

- Designing Data-Intensive Applications Ch. 3-5

- Storage engines, replication

- Designing Data-Intensive Applications Ch. 8-9

- Distributed systems problems, consensus

- Pro Git Ch. 10

- Git internals

Week 5: Abstraction & Languages

- Crafting Interpreters Ch. 1-8

- Scanning, parsing, evaluating (or full book if doing interpreter project)

- The Linux Programming Interface Ch. 28

- Namespaces

- Build Your Own React (pomb.us)

- React internals

Week 6: Advanced Topics

- Rust Atomics and Locks (full book)

- Memory ordering, lock-free programming

- C++ Concurrency in Action Ch. 5

- Memory model (applies to any language)

- The Raft paper

- “In Search of an Understandable Consensus Algorithm”

Tools for Understanding

Memory Debugging

# AddressSanitizer (compile-time instrumentation)

clang -fsanitize=address -g program.c -o program

./program # Reports memory errors with stack traces

# Valgrind (runtime instrumentation)

valgrind --leak-check=full ./program

valgrind --tool=helgrind ./program # For threading bugs

# GDB/LLDB

lldb ./program

(lldb) breakpoint set --name main

(lldb) run

(lldb) memory read &variable

(lldb) register read

Network Debugging

# See what's on the wire

tcpdump -i any port 8080 -A

# Interactive packet inspection

wireshark

# Test TCP connections

nc -l 8080 # Listen

nc localhost 8080 # Connect

# HTTP debugging

curl -v http://localhost:8080/

System Inspection

# Process memory map

cat /proc/$PID/maps

# Open files and sockets

lsof -p $PID

# System calls

strace ./program

# Namespace inspection

ls -la /proc/$PID/ns/

# Cgroup inspection

cat /sys/fs/cgroup/$CGROUP/memory.current

Part II: The Projects

With these foundations in place, you’re ready to tackle the projects. Each project below includes specific questions and guidance to help you apply what you’ve learned.

Project 1: Memory Allocator (malloc/free from scratch)

Source File: TRACK_A_OS_KERNEL_PROJECTS.md

Language: C

Why Interviewers Love This: Every C/C++ interview eventually goes to memory. Building malloc proves you understand what happens when you write int *p = malloc(sizeof(int) * 100);

Original Project Specification

- Programming Language: C

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Memory Management / Systems Programming

- Software or Tool: sbrk / mmap

- Main Book: “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” by Bryant & O’Hallaron

What you’ll build: A complete memory allocator that replaces malloc/free, using only brk() and mmap() syscalls, with visual debugging output showing heap state.

Why it teaches OS internals: malloc is the interface between your program and the kernel’s virtual memory system. By implementing it, you’ll understand why the heap exists, how the kernel grows your address space, the difference between virtual and physical memory, and why memory fragmentation happens.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Managing the program break with

brk()/sbrk()(maps to virtual memory, syscalls) - Using

mmap()for large allocations (maps to virtual memory, page faults) - Implementing free lists and coalescing (maps to memory management algorithms)

- Handling alignment requirements (maps to hardware memory model)

- Debugging memory corruption (maps to understanding address space layout)

Resources for key challenges:

- “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” Ch. 9.9 - Detailed malloc implementation walkthrough

- “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” Ch. 17 - Free space management

Key Concepts:

- Virtual address space layout: “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” Ch. 9 - Bryant & O’Hallaron

- Free list management: “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” Ch. 17 - Arpaci-Dusseau

- mmap syscall: “The Linux Programming Interface” Ch. 49 - Michael Kerrisk

- Memory alignment: “C Interfaces and Implementations” Ch. 5 - David Hanson

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 2-3 weeks Prerequisites: C, pointers, basic understanding of processes

Real world outcome:

LD_PRELOAD=./mymalloc.so ./some_program- Replace system malloc with yours- Visual heap dump:

[BLOCK 0x1000: 64 bytes USED] [BLOCK 0x1040: 128 bytes FREE] ... - Run benchmarks comparing your allocator to glibc malloc

- Successfully run complex programs (even a shell) using your allocator

Learning milestones:

- Basic allocation with brk works → You understand heap growth and the program break

- Free works with coalescing → You understand fragmentation and metadata management

- mmap for large allocations → You understand different memory mapping strategies

- Can run real programs → You’ve built something production-quality

The Core Question You’re Answering

“When I call malloc, where do those bytes come from? And when I call free, where do they go?”

Before you write a single line of code, sit with this question. Most developers have a vague sense of “the heap” but can’t explain what that actually means.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Virtual Memory vs Physical Memory

- What’s the difference? Why does it matter?

- What does the OS actually give you when you “get memory”?

- Book Reference: “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” Ch. 9 - Bryant & O’Hallaron

- The Program Break (

brk/sbrk)- What is the “program break”? Where is it in your address space?

- What system call changes it?

- Why is this called “growing the heap”?

mmapfor Anonymous Memory- When should you use

mmapinstead ofsbrk? - Why do production allocators use both?

- Book Reference: “The Linux Programming Interface” Ch. 49 - Michael Kerrisk

- When should you use

- Alignment Requirements

- Why can’t you just return any address?

- What happens if you return a misaligned pointer?

- How does the CPU access memory?

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Block Metadata

- How will you know, given a pointer from

free(), how big that block was? - Where will you store this information? Before the user’s data? After?

- What’s the minimum overhead per allocation?

- How will you know, given a pointer from

- Free List Management

- When you

free()a block, where does it go? - How will you find a suitable block for the next

malloc()? - What’s the trade-off between speed and memory efficiency?

- When you

- Finding a Free Block: Strategies

- First Fit: Find the first block big enough. What’s the problem?

- Best Fit: Find the smallest block that fits. Why is this slow?

- Next Fit: Start searching where you left off. Why might this help?

Think: Which would you choose, and why?

- Fragmentation

- What happens when you have 1000 bytes free, but split across 10 non-contiguous blocks?

- Can you satisfy

malloc(500)even though you have 1000 bytes free? - What is “external fragmentation”?

- Coalescing

- When you

free()a block, what if the blocks before and after are also free? - Should you merge them? How?

- What data structure lets you check neighbors quickly?

- When you

Thinking Exercise: Walk Through by Hand

Before coding, trace this sequence on paper:

malloc(100) -> returns 0x1000

malloc(50) -> returns 0x1068 (why?)

malloc(200) -> returns 0x10A0

free(0x1068)

malloc(30) -> returns ??? (where does this go?)

free(0x1000)

free(0x10A0)

malloc(300) -> what happens now?

Questions while tracing:

- Where are your metadata headers?

- How big is each block really (including metadata)?

- After the frees, what does your free list look like?

- Can you coalesce after the last two frees?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “Walk me through what happens when you call

malloc(1000).” - “Why do you need alignment? What could go wrong?”

- “What’s the difference between internal and external fragmentation?”

- “When would you use

mmapinstead ofsbrk?” - “How would you debug a double-free bug?”

- “What’s wrong with this code:

free(p); free(p);?”

Hints in Layers (Only If Stuck)

Hint 1: Start Simple

Implement a bump allocator first. Just keep a pointer and move it forward on each malloc. Never reuse memory. This is “wrong” but teaches you the basics.

Hint 2: Free List Structure

A free list is just a linked list where each node is a free block. The “next” pointer lives inside the free block itself (since it’s not being used for user data).

Hint 3: Boundary Tags

To check if your neighbors are free, put size information at BOTH ends of each block. This is called “boundary tags” and lets you coalesce in O(1).

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| The big picture | “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” | Ch. 9 (Virtual Memory) |

| Implementation walkthrough | “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” | Ch. 9.9 (Dynamic Memory Allocation) |

| Free space management | “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” | Ch. 17 |

| mmap syscall | “The Linux Programming Interface” | Ch. 49 |

| Clean C interface design | “C Interfaces and Implementations” | Ch. 5 |

Real World Outcome

You’ll create a drop-in replacement for the system malloc that can run real programs. Here’s EXACTLY what success looks like:

When you compile your allocator as a shared library:

$ gcc -shared -fPIC -o libmymalloc.so mymalloc.c

# Test with a simple program

$ cat > test.c <<EOF

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

char *str = malloc(100);

sprintf(str, "Hello from custom malloc!");

printf("%s\n", str);

free(str);

return 0;

}

EOF

$ gcc test.c -o test

# Run with your allocator instead of glibc's

$ LD_PRELOAD=./libmymalloc.so ./test

[MALLOC] Requesting 100 bytes

[MALLOC] Heap break at 0x5651a2b3d000

[MALLOC] sbrk(4096) to grow heap

[MALLOC] Allocated block at 0x5651a2b3d010, size=100, total=112 (with header)

Hello from custom malloc!

[FREE] Freeing block at 0x5651a2b3d010

[FREE] Coalescing with next free block

When you enable visual heap dumps, you’ll see memory state:

$ LD_PRELOAD=./libmymalloc.so MALLOC_DEBUG=1 ./test

Initial heap state:

Heap start: 0x5651a2b3d000

Heap end: 0x5651a2b3d000

Free list: (empty)

After malloc(100):

┌───────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ USED: 112 bytes @ 0x5651a2b3d000 │ ← Your allocation

├───────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ FREE: 3984 bytes @ 0x5651a2b3d070 │ ← Remaining heap

└───────────────────────────────────────────┘

After free:

┌───────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ FREE: 4096 bytes @ 0x5651a2b3d000 │ ← Coalesced

└───────────────────────────────────────────┘

Free list: 0x5651a2b3d000 → NULL

Running complex programs with your allocator:

# Can it run /bin/ls?

$ LD_PRELOAD=./libmymalloc.so /bin/ls

[MALLOC] 384 allocations, 127 frees, 94KB allocated

Desktop Documents Downloads Pictures

[MALLOC] Shutting down: 257 blocks still in use (leak detection)

# Can it run a shell?

$ LD_PRELOAD=./libmymalloc.so /bin/bash

bash-5.1$ echo "It works!"

It works!

bash-5.1$ exit

[MALLOC] Total stats: 8472 allocations, 8470 frees

# Performance comparison

$ time ./benchmark

glibc malloc: 1.23s, 0 bytes leaked

$ time LD_PRELOAD=./libmymalloc.so ./benchmark

my malloc: 2.87s, 0 bytes leaked

# Your allocator is ~2.3x slower than glibc (that's normal for a basic impl)

Advanced: Integration with debugging tools

# Your allocator should work with valgrind's memcheck

$ valgrind --leak-check=full --suppressions=malloc.supp ./test

# AddressSanitizer compatibility

$ gcc -fsanitize=address test.c -o test

$ LD_PRELOAD=./libmymalloc.so ./test

# Should report memory errors correctly

You know you’ve succeeded when:

- ✅ Simple test programs allocate and free correctly

- ✅ Complex programs (ls, bash, python) run without crashes

- ✅ Memory leaks are detected and reported

- ✅ Fragmentation is reasonable (check with long-running tests)

- ✅ Double-free is detected and causes controlled failure

- ✅ Performance is within 3-5x of glibc malloc

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem 1: “Segfault when freeing memory”

Symptom:

$ ./test

Hello from custom malloc!

Segmentation fault (core dumped)

- Why: You’re likely corrupting the free list pointers. When you free a block, you write a

nextpointer inside it. If the user’s code wrote past their allocation, they’ve overwritten your free list metadata. - Fix:

- Add “canary” values (magic numbers) before and after each block

- Check canaries on every malloc/free

- Use AddressSanitizer during development:

gcc -fsanitize=address

- Quick test: ```c // Add to your block header struct block { size_t size; unsigned int magic_start; // Set to 0xDEADBEEF // … user data … unsigned int magic_end; // Set to 0xBEEFDEAD at block+size };

// In free(), check: if (block->magic_start != 0xDEADBEEF) { fprintf(stderr, “Heap corruption detected at %p\n”, block); abort(); }

**Problem 2: "Program runs out of memory quickly"**

**Symptom:**

```bash

[MALLOC] sbrk(4096)

[MALLOC] sbrk(4096)

... (thousands of times)

[MALLOC] Failed to allocate: Cannot allocate memory

- Why: Your free list isn’t working. Every malloc calls

sbrkinstead of reusing freed blocks. Freed blocks aren’t being added to the free list, or your search algorithm never finds them. - Fix:

- Add logging to free():

printf("Added %p to free list\n", block); - Add logging to malloc search:

printf("Checking block %p, size=%zu, needed=%zu\n", ...); - Verify free list is a linked list: walk it and print all nodes

- Add logging to free():

- Quick test:

# Should see reuse malloc(100); free(); malloc(100); # Should NOT call sbrk twice

Problem 3: “Mysterious corruption after many allocations”

Symptom: Program runs fine for a while, then crashes randomly. Different behavior on each run.

- Why: Buffer overflow somewhere. User code wrote past allocation boundary, corrupting adjacent block headers.

- Fix:

- Allocate extra space for guard pages:

// Allocate 1 page before and after heap region, mark as PROT_NONE mmap(..., PROT_NONE); // Before mmap(..., PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE); // Actual heap mmap(..., PROT_NONE); // After // Any access to guard pages = instant crash at exact location - Use AddressSanitizer: It catches out-of-bounds writes

- Fill free blocks with pattern:

0xDEADBEEF— if you see this value in unexpected places, it’s a freed block being used

- Allocate extra space for guard pages:

- Quick test:

char *p = malloc(10); p[15] = 'X'; // Out of bounds write free(p); malloc(10); // Corruption might appear here

Problem 4: “Alignment errors on certain architectures”

Symptom:

Bus error (core dumped) # On ARM/RISC-V

# Or: SIGILL, Illegal instruction

- Why: You returned a misaligned pointer. Some CPUs require pointers to be aligned to their size (8-byte aligned for 64-bit values).

- Fix:

- Always align to 16 bytes (safe for all types):

#define ALIGNMENT 16 #define ALIGN(size) (((size) + (ALIGNMENT-1)) & ~(ALIGNMENT-1)) size_t alloc_size = ALIGN(requested_size + sizeof(header)); - Return pointer AFTER header, aligned:

void *user_ptr = (void *)((char *)block + sizeof(header)); assert((uintptr_t)user_ptr % 16 == 0); // Verify alignment

- Always align to 16 bytes (safe for all types):

- Quick test:

double *d = malloc(sizeof(double)); *d = 3.14; // Should NOT crash

Problem 5: “Double-free not detected”

Symptom:

free(p);

free(p); // Should crash or warn, but doesn't

malloc(...); // Returns garbage or crashes later

- Why: You’re not marking blocks as free/in-use. Can’t distinguish freed blocks from allocated blocks.

- Fix:

- Add a

is_freeflag to block header:struct block { size_t size; int is_free; // 0 = allocated, 1 = free struct block *next; // Only valid if is_free==1 }; - Check in free():

if (block->is_free) { fprintf(stderr, "Double-free detected at %p\n", ptr); abort(); } block->is_free = 1;

- Add a

- Quick test:

void *p = malloc(100); free(p); free(p); // Should abort with "Double-free detected"

Problem 6: “Huge memory waste (fragmentation)”

Symptom:

# After 1000 alloc/free cycles:

[MALLOC] Heap size: 512KB

[MALLOC] Actually in use: 50KB

[MALLOC] Wasted: 462KB across 789 tiny free blocks

- Why: External fragmentation. Lots of small free blocks that can’t satisfy larger requests.

- Fix:

- Implement coalescing: When freeing, check if adjacent blocks are also free and merge them.

- Use boundary tags: Put size at BOTH ends of block so you can check neighbors in O(1).

- Strategy choice: Best-fit is better than first-fit for fragmentation (but slower).

- Quick test:

// Worst case for fragmentation for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++) { malloc(8); malloc(64); } // Free all the 8-byte blocks // Then try malloc(100) — should succeed by coalescing

Debugging Tools Checklist:

| Tool | When to Use | Command |

|---|---|---|

| AddressSanitizer | Detect out-of-bounds access, use-after-free | gcc -fsanitize=address |

| Valgrind memcheck | Find memory leaks, uninitialized reads | valgrind --leak-check=full |

| GDB | Step through malloc/free logic | gdb ./program |

| strace | See actual sbrk/mmap syscalls | strace -e brk,mmap ./program |

| Heap profiler | Visualize fragmentation | Custom tool or Massif |

Project 2: Build a Load Balancer

Source File: SYSTEM_DESIGN_MASTERY_PROJECTS.md

Language: Go (or C, Rust, Python)

Why Interviewers Love This: This is THE classic system design question. “Design a load balancer” appears in almost every senior backend interview.

Original Project Specification

- Programming Language: Go

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, C, Python

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 3. The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Networking / Distributed Systems

- Software or Tool: HAProxy / Nginx (conceptual model)

- Main Book: “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” by Martin Kleppmann

What you’ll build: A TCP/HTTP load balancer that distributes incoming connections across multiple backend servers using configurable algorithms (round-robin, least-connections, weighted), performs health checks, and gracefully removes unhealthy servers.

Why it teaches system design: Load balancers are the front door of every distributed system. Building one forces you to understand:

- How to handle thousands of concurrent connections

- Health checking and failure detection

- The difference between L4 and L7 load balancing

- Connection pooling and keep-alive management

- Why NGINX and HAProxy make certain architectural choices

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Connection multiplexing (one goroutine per connection won’t scale) → maps to concurrency patterns

- Health check design (how often? what counts as “unhealthy”?) → maps to failure detection

- Graceful degradation (what happens when all backends are down?) → maps to fault tolerance

- Hot reload config (change backends without dropping connections) → maps to zero-downtime operations

- Sticky sessions (route same user to same backend) → maps to stateful vs stateless

Key Concepts:

- Connection Management: “The Linux Programming Interface” Chapter 59-61 - Michael Kerrisk

- Concurrency Patterns: “Learning Go, 2nd Edition” Chapter 12 - Jon Bodner

- Load Balancing Algorithms: “System Design Interview” Chapter 6 - Alex Xu

- Health Checks: “Building Microservices, 2nd Edition” Chapter 11 - Sam Newman

Difficulty: Advanced Time estimate: 2-3 weeks Prerequisites: Network sockets, concurrency basics, HTTP protocol

Real world outcome:

# Start 3 backend servers

$ ./backend --port 8081 --name "Server-A" &

$ ./backend --port 8082 --name "Server-B" &

$ ./backend --port 8083 --name "Server-C" &

# Start your load balancer

$ ./loadbalancer --config lb.yaml --port 80

[LB] Loaded 3 backends: 8081, 8082, 8083

[LB] Health checker started (interval: 5s)

[LB] Listening on :80

# Test distribution

$ for i in {1..6}; do curl http://localhost/; done

Response from Server-A

Response from Server-B

Response from Server-C

Response from Server-A

Response from Server-B

Response from Server-C

# Kill one backend, watch failover

$ kill %2 # Kill Server-B

[LB] Backend 8082 failed health check (3 consecutive failures)

[LB] Removed 8082 from pool

$ for i in {1..4}; do curl http://localhost/; done

Response from Server-A

Response from Server-C

Response from Server-A

Response from Server-C

Implementation Hints:

- Start with a simple TCP proxy that forwards bytes between client and one backend

- Add round-robin by maintaining a counter and using modulo

- Health checks should run in a separate goroutine with configurable intervals

- Use channels to communicate backend status changes to the main routing logic

- For HTTP, you’ll need to parse headers to implement features like sticky sessions (look at the

Cookieheader)

Learning milestones:

- TCP proxy works → You understand socket forwarding and connection lifecycle

- Round-robin distributes evenly → You understand stateless routing

- Unhealthy servers are removed → You understand failure detection patterns

- Zero-downtime config reload → You understand graceful operations

The Core Question You’re Answering

“If I have 10 servers, how do I decide which one handles each request?”

This seems simple until you consider: What if one server is down? What if one is slow? What if you need session persistence?

Concepts You Must Understand First

- OSI Layers: L4 vs L7

- What’s the difference between a Layer 4 and Layer 7 load balancer?

- At L4, what information do you have to make decisions?

- At L7, what additional information becomes available?

- Why is L7 more resource-intensive?

- Load Balancing Algorithms

- Round Robin: Simple, but what’s wrong with it?

- Least Connections: Better for long requests, but how do you track connection counts?

- Weighted: Not all servers are equal. How do you assign weights?

- IP Hash: Sticky without storing state. But what’s the problem when servers change?

- Health Checking

- Active vs Passive health checks - what’s the difference?

- How often should you check? What’s the trade-off?

- How many failures before you mark a server as down?

- What about “half-open” state for recovery?

- Connection Management

- What is keep-alive? Why does it matter?

- What’s connection pooling? Why do load balancers need it?

- What happens to in-flight requests when a backend dies?

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Data Flow

- When a client connects, what bytes are you reading?

- If you’re L7, how do you know when the HTTP request is complete?

- How do you forward bytes to the backend?

- How do you forward the response back?

- Concurrency Model

- One thread per connection? (Simple but doesn’t scale)

- Event-driven with epoll/kqueue? (Scalable but complex)

- Go’s goroutines? (Balance of simplicity and scale)

- What are the trade-offs?

- State Management

- What state do you need to track per connection?

- What state do you need globally (like backend health)?

- How do you share this state safely between threads/goroutines?

- Failure Modes

- What happens if a backend is slow but not down?

- What if your load balancer itself crashes?

- What about “cascading failures”?

Thinking Exercise: Design the Algorithm

Consider this scenario:

- 3 backends: A (weight=1), B (weight=2), C (weight=1)

- Backend B just failed a health check

- You need to route the next 10 requests

Questions:

- How do weighted round-robin work with these weights?

- What happens to B’s traffic while it’s marked unhealthy?

- When should B come back into rotation?

- What if B is marked healthy but then fails again immediately?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “How would you design a load balancer for 1 million requests per second?”

- “What’s the difference between L4 and L7 load balancing?”

- “How do you handle sticky sessions? What are the trade-offs?”

- “How would you implement graceful degradation when backends are failing?”

- “What happens to in-flight requests when you need to remove a backend?”

- “How do you prevent the thundering herd problem?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start as a Proxy

First, build a simple TCP proxy that forwards all traffic to ONE backend. Get this working perfectly before adding multiple backends.

Hint 2: Health Check Goroutine

Run health checks in a separate goroutine on a timer. Use a channel or atomic variable to communicate backend status to the main routing logic.

Hint 3: Hot Reload

To reload config without dropping connections, don’t close existing connections. Just let them drain while new connections use the new config.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Networking fundamentals | “The Linux Programming Interface” | Ch. 59-61 |

| System design context | “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” | Ch. 1 (Reliability, Scalability) |

| Health checks | “Building Microservices, 2nd Edition” | Ch. 11 |

| Load balancing concepts | “System Design Interview” | Ch. 6 |

Real World Outcome

You’ll build a production-ready L7 (application-layer) load balancer that distributes HTTP traffic across backend servers with health checking and multiple routing algorithms. Here’s exactly what you’ll see:

Starting your load balancer:

$ go build -o loadbalancer main.go

$ ./loadbalancer --port 8080 \

--backends "http://backend1:3000,http://backend2:3000,http://backend3:3000" \

--algorithm round-robin \

--health-check-interval 5s

[2024-12-28 10:15:30] Load Balancer starting on :8080

[2024-12-28 10:15:30] Backend pool:

[1] http://backend1:3000 (healthy)

[2] http://backend2:3000 (healthy)

[3] http://backend3:3000 (healthy)

[2024-12-28 10:15:30] Algorithm: Round Robin

[2024-12-28 10:15:30] Health check: every 5s

[2024-12-28 10:15:30] Ready to accept connections

When clients make requests, you’ll see routing decisions:

# Client makes requests

$ curl http://localhost:8080/api/users

{"users": [...]}

# Load balancer logs

[2024-12-28 10:15:35] 192.168.1.100 → backend1:3000 | GET /api/users | 200 OK | 45ms

[2024-12-28 10:15:36] 192.168.1.100 → backend2:3000 | GET /api/posts | 200 OK | 32ms

[2024-12-28 10:15:37] 192.168.1.100 → backend3:3000 | GET /api/comments | 200 OK | 28ms

[2024-12-28 10:15:38] 192.168.1.100 → backend1:3000 | GET /api/likes | 200 OK | 51ms

# Round-robin: backend1 → backend2 → backend3 → backend1 ...

Health checking in action:

# Backend2 crashes

[2024-12-28 10:16:00] Health check failed: backend2:3000 (connection refused)

[2024-12-28 10:16:00] Marking backend2:3000 as UNHEALTHY

[2024-12-28 10:16:00] Available backends: 2/3

# Traffic automatically reroutes

[2024-12-28 10:16:02] 192.168.1.100 → backend1:3000 | GET /api/users | 200 OK | 43ms

[2024-12-28 10:16:03] 192.168.1.100 → backend3:3000 | GET /api/users | 200 OK | 39ms

[2024-12-28 10:16:04] 192.168.1.100 → backend1:3000 | GET /api/users | 200 OK | 41ms

# Skipping backend2 (unhealthy)

# Backend2 recovers

[2024-12-28 10:16:30] Health check succeeded: backend2:3000

[2024-12-28 10:16:30] Marking backend2:3000 as HEALTHY

[2024-12-28 10:16:30] Available backends: 3/3

Different load balancing algorithms:

# Weighted round-robin

$ ./loadbalancer --algorithm weighted-round-robin \

--weights "backend1:3000=5,backend2:3000=3,backend3:3000=2"

[Requests] backend1 gets 50%, backend2 gets 30%, backend3 gets 20%

# Least connections

$ ./loadbalancer --algorithm least-connections

[2024-12-28 10:20:00] Active connections:

backend1:3000 → 12 connections

backend2:3000 → 8 connections

backend3:3000 → 15 connections

[2024-12-28 10:20:01] New request → backend2:3000 (least loaded)

# IP hash (sticky sessions)

$ ./loadbalancer --algorithm ip-hash

[2024-12-28 10:25:00] 192.168.1.100 → backend1:3000 (hash: 0x5A3B)

[2024-12-28 10:25:01] 192.168.1.100 → backend1:3000 (same client, same backend)

[2024-12-28 10:25:02] 192.168.1.101 → backend2:3000 (hash: 0x7C2F)

Metrics and monitoring:

# Access metrics endpoint

$ curl http://localhost:8080/metrics

{

"total_requests": 15234,

"successful_requests": 15102,

"failed_requests": 132,

"avg_response_time_ms": 42,

"backends": [

{

"url": "http://backend1:3000",

"healthy": true,

"total_requests": 5102,

"active_connections": 8,

"avg_response_time_ms": 45,

"error_rate": 0.008

},

{

"url": "http://backend2:3000",

"healthy": true,

"total_requests": 5051,

"active_connections": 6,

"avg_response_time_ms": 38,

"error_rate": 0.011

},

{

"url": "http://backend3:3000",

"healthy": true,

"total_requests": 5081,

"active_connections": 7,

"avg_response_time_ms": 43,

"error_rate": 0.009

}

]

}

Load testing to verify distribution:

# Generate 10,000 requests with 100 concurrent clients

$ hey -n 10000 -c 100 http://localhost:8080/api/test

Summary:

Total: 12.3456 secs

Requests/sec: 809.87

Status code distribution:

[200] 9987 responses

[503] 13 responses (backend temporarily down)

# Check distribution

$ curl http://localhost:8080/metrics | jq '.backends[].total_requests'

3329 # backend1

3337 # backend2

3321 # backend3

# Nearly perfect distribution with round-robin

Advanced: Circuit breaker pattern:

# Backend starts failing repeatedly

[2024-12-28 11:00:00] backend2:3000 error (timeout)

[2024-12-28 11:00:01] backend2:3000 error (timeout)

[2024-12-28 11:00:02] backend2:3000 error (timeout)

[2024-12-28 11:00:03] Circuit breaker OPEN for backend2:3000

[2024-12-28 11:00:03] Temporarily removing backend2 from pool (60s cooldown)

# After cooldown, try again

[2024-12-28 11:01:03] Circuit breaker HALF-OPEN for backend2:3000

[2024-12-28 11:01:03] Sending probe request...

[2024-12-28 11:01:04] Probe succeeded → Circuit breaker CLOSED

[2024-12-28 11:01:04] backend2:3000 back in rotation

You know you’ve succeeded when:

- ✅ Traffic distributes evenly across all healthy backends

- ✅ Failed backends are automatically detected and removed from rotation

- ✅ Recovered backends are automatically re-added

- ✅ No requests fail due to load balancer issues

- ✅ Performance overhead is < 5ms per request

- ✅ Can handle 1000+ req/sec without dropping connections

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem 1: “Connection refused when backends are actually up”

Symptom:

[ERROR] Failed to connect to backend1:3000: connection refused

# But: curl http://backend1:3000 works fine!

- Why: Your load balancer is likely binding to a network interface that can’t reach the backends. Common in Docker/VM environments where

localhostmeans different things in different namespaces. - Fix:

- Use fully qualified hostnames instead of

localhost:http://backend1.local:3000 - Check DNS resolution:

dig backend1.localorhost backend1 - Verify network connectivity:

telnet backend1 3000 - If using Docker: ensure all containers are on the same network

- Use fully qualified hostnames instead of

- Quick test:

# From load balancer container/host $ nc -zv backend1 3000 Connection to backend1 3000 port [tcp/*] succeeded!

Problem 2: “Requests pile up on one backend despite round-robin”

Symptom:

backend1: 8234 requests

backend2: 152 requests

backend3: 94 requests

# Expected even distribution!

- Why: You’re not thread-safe. Multiple goroutines/threads are reading and writing the “current backend index” simultaneously, causing race conditions.

- Fix:

- Use atomic operations:

import "sync/atomic" var currentIndex uint32 func nextBackend() *Backend { idx := atomic.AddUint32(¤tIndex, 1) return backends[idx % len(backends)] } - Or use a mutex:

var mu sync.Mutex var currentIndex int func nextBackend() *Backend { mu.Lock() defer mu.Unlock() backend := backends[currentIndex] currentIndex = (currentIndex + 1) % len(backends) return backend }

- Use atomic operations:

- Quick test:

# Run with race detector $ go run -race main.go # Should report: WARNING: DATA RACE if not properly synchronized

Problem 3: “Health checks mark healthy backends as down”

Symptom:

[2024-12-28] Health check failed: backend1:3000 (i/o timeout)

# But backend1 is fine and serving traffic!

- Why: Health check timeout is too aggressive. Backend might be slow but not dead. Or you’re checking during a legitimate slow moment.

- Fix:

- Increase timeout:

http.Client{Timeout: 10 * time.Second} - Use exponential backoff: Don’t mark unhealthy on first failure

if failureCount >= 3 { // 3 consecutive failures markUnhealthy(backend) } - Check a lightweight endpoint:

/healthinstead of/api/heavy-operation

- Increase timeout:

- Quick test:

```bash

Manually test health check endpoint

$ time curl -i http://backend1:3000/health HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Time: 0.523s

If consistently > your timeout, adjust timeout upward

**Problem 4: "Load balancer crashes under load"**

**Symptom:**

```bash

# At 500 req/sec

panic: runtime error: slice bounds out of range

# Or

fatal error: concurrent map writes

- Why: Either:

- You’re modifying the backend list while iterating (when removing unhealthy backends)

- You’re using a map without locks

- You’re hitting Go’s file descriptor limit

- Fix:

- For slice iteration:

// Copy slice before modifying healthyBackends := make([]*Backend, len(backends)) copy(healthyBackends, backends) // Now iterate over healthyBackends, modify backends - For map access:

type SafeMap struct { mu sync.RWMutex data map[string]*Backend } - Increase file descriptor limit:

ulimit -n 65536 # Or in code: syscall.Setrlimit(syscall.RLIMIT_NOFILE, ...)

- For slice iteration:

- Quick test:

# Load test $ ab -n 10000 -c 100 http://localhost:8080/ # Should not crash

Problem 5: “Sticky sessions don’t work (IP hash broken)”

Symptom:

# Same client IP, different backends

192.168.1.100 → backend1

192.168.1.100 → backend3

192.168.1.100 → backend2

- Why: You’re hashing the wrong IP. Likely hashing the connection’s local IP (always 127.0.0.1 if behind a proxy) instead of the original client IP.

- Fix:

- Read X-Forwarded-For header: