Deep Dive into SSH: From Protocol to Implementation

Goal: Master the Digital Master Key to the Modern World

Why SSH Matters in the Real World

SSH (Secure Shell) is not just another network protocol—it is the foundational security primitive that powers the entire modern infrastructure. Every time you deploy code to a server, manage cloud infrastructure, access a database, or administer a remote system, you’re relying on SSH. Understanding SSH deeply transforms you from a user who types ssh user@host into someone who understands the cryptographic handshake, the threat models, and the security guarantees that make remote administration possible in a hostile network environment.

Real-world systems powered by SSH:

- Cloud Infrastructure: AWS, Google Cloud, Azure—all remote access uses SSH

- DevOps Pipelines: CI/CD systems (GitHub Actions, GitLab CI, Jenkins) use SSH for deployment

- Database Administration: PostgreSQL, MySQL, MongoDB remote management

- Git Operations: GitHub, GitLab push/pull operations over SSH

- Container Orchestration: Kubernetes node management, Docker remote API access

- Network Equipment: Cisco, Juniper, and all enterprise networking gear management

- Critical Infrastructure: Power grids, financial systems, telecommunications rely on SSH

According to recent analyses, SSH is present on over 70% of all internet-connected servers, making it one of the most ubiquitous security protocols in existence. Recent 2024/2025 security trends show alarming statistics:

- 73% of confirmed identity-based breaches were due to compromised credentials (2024 data)

- Stolen credentials were the #1 attacker action, responsible for 80% of web app attacks (2023/24 data)

- Breaches involving stolen credentials cost an average of $4.8M per incident and took 88 days longer to resolve (292-day lifecycle)

- SSH adoption is projected to reach 96% among enterprises by 2032, showing strong continued growth

- 78% of enterprises now use advanced secure data transfer methods (up from 61% in 2023), with SSH as a cornerstone

- Major 2024 breaches (Ticketmaster, Change Healthcare, AT&T) involved over 1.24 billion compromised records due to lack of proper authentication controls

Understanding SSH isn’t optional—it’s mandatory for anyone serious about systems programming, security, or infrastructure. The statistics make clear that weak SSH key management and authentication are direct contributors to some of the costliest security incidents in modern history.

What You’ll Be Able to Do After These Projects

After completing this learning journey, you will:

- Understand Cryptographic Primitives in Practice: Move beyond theoretical knowledge to implementing real encryption, key exchange, and authentication protocols

- Read and Parse Network Protocols: Decode binary protocols, understand packet structures, and analyze network traffic at a deep level

- Build Secure Systems: Design and implement authentication systems that resist man-in-the-middle attacks, replay attacks, and credential theft

- Debug Production SSH Issues: Understand why SSH connections fail, diagnose authentication problems, and configure secure SSH servers

- Implement Tunneling and Multiplexing: Build tools that create secure channels through hostile networks

- Think Like a Security Engineer: Understand threat models, defense-in-depth, and the “why” behind security decisions

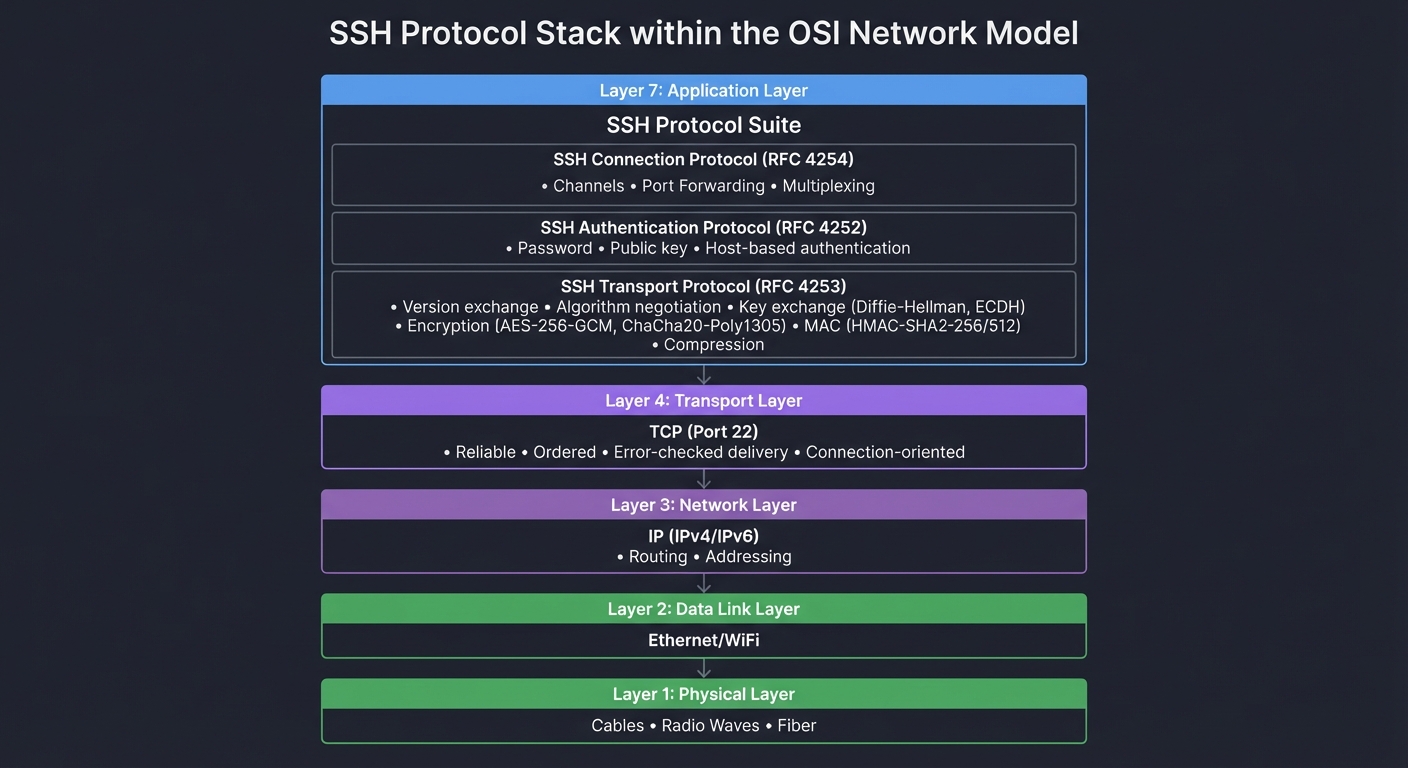

SSH in the Network Stack

Understanding where SSH sits in the protocol stack is crucial:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ APPLICATION LAYER (OSI Layer 7) │

│ ┌───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ SSH Protocol Suite (Your Programs Will Implement This) │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ SSH Connection Protocol (RFC 4254) │ │ │

│ │ │ - Channels (session, exec, shell, subsystem) │ │ │

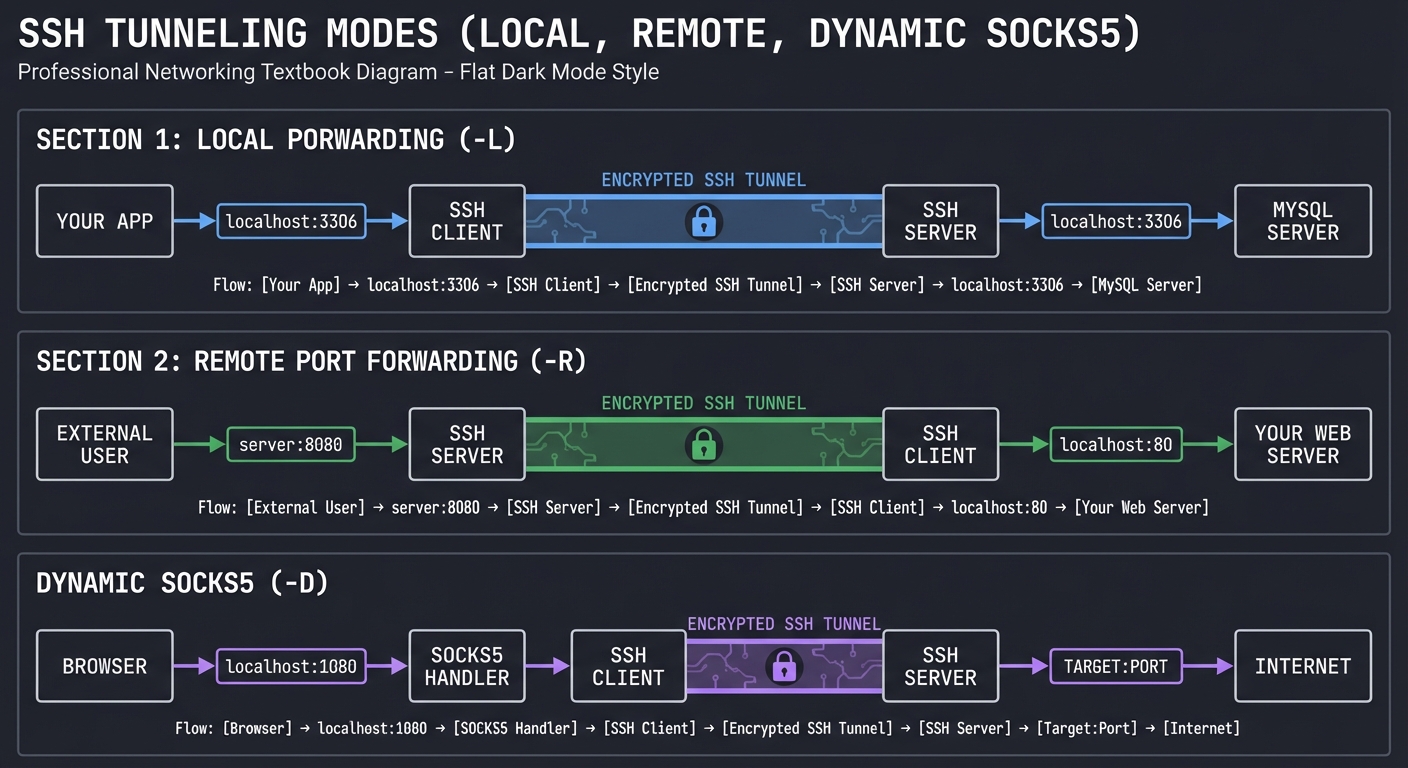

│ │ │ - Port Forwarding (local, remote, dynamic) │ │ │

│ │ │ - Multiplexing multiple logical streams │ │ │

│ │ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │ │

│ │ ↑ │ │

│ │ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ SSH Authentication Protocol (RFC 4252) │ │ │

│ │ │ - Password authentication │ │ │

│ │ │ - Public key authentication (RSA, Ed25519) │ │ │

│ │ │ - Host-based authentication │ │ │

│ │ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │ │

│ │ ↑ │ │

│ │ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ SSH Transport Protocol (RFC 4253) │ │ │

│ │ │ - Version exchange │ │ │

│ │ │ - Algorithm negotiation │ │ │

│ │ │ - Key exchange (Diffie-Hellman, ECDH) │ │ │

│ │ │ - Encryption (AES-256-GCM, ChaCha20-Poly1305) │ │ │

│ │ │ - MAC (HMAC-SHA2-256, HMAC-SHA2-512) │ │ │

│ │ │ - Compression (optional) │ │ │

│ │ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │ │

│ └───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

↓

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ TRANSPORT LAYER (OSI Layer 4) │

│ TCP (Port 22) │

│ - Reliable, ordered, error-checked delivery │

│ - Connection-oriented (3-way handshake) │

│ - Flow control and congestion control │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

↓

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ NETWORK LAYER (OSI Layer 3) │

│ IP (IPv4/IPv6) │

│ - Routing between networks │

│ - Addressing (IP addresses) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

↓

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ DATA LINK LAYER (OSI Layer 2) │

│ Ethernet / WiFi / etc. │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

↓

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ PHYSICAL LAYER (OSI Layer 1) │

│ Cables, Radio Waves, Fiber │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Key Insight: SSH is an APPLICATION layer protocol that runs on top of TCP.

This means SSH assumes TCP provides reliable, ordered delivery, and SSH

adds: encryption, authentication, integrity checking, and multiplexing.

Critical Understanding: SSH doesn’t replace TCP—it builds on top of it. When you implement SSH, you’ll work with TCP sockets to get reliable byte streams, then implement SSH’s layered protocol on top. This is why Project 1 starts with raw TCP communication.

Detailed Concept Explanations

This section provides deep dives into each concept area. Understanding these concepts at a fundamental level is what separates developers who use SSH from developers who understand SSH.

1. Cryptography: The Foundation of SSH Security

Why Cryptography Matters for SSH

SSH’s entire value proposition is security over an untrusted network. Without cryptography, SSH would just be Telnet—sending passwords and commands in plaintext for anyone to intercept. Cryptography provides three critical security properties:

- Confidentiality: Eavesdroppers can’t read your data

- Integrity: Attackers can’t modify your data without detection

- Authenticity: You’re talking to the right server (and the server knows it’s you)

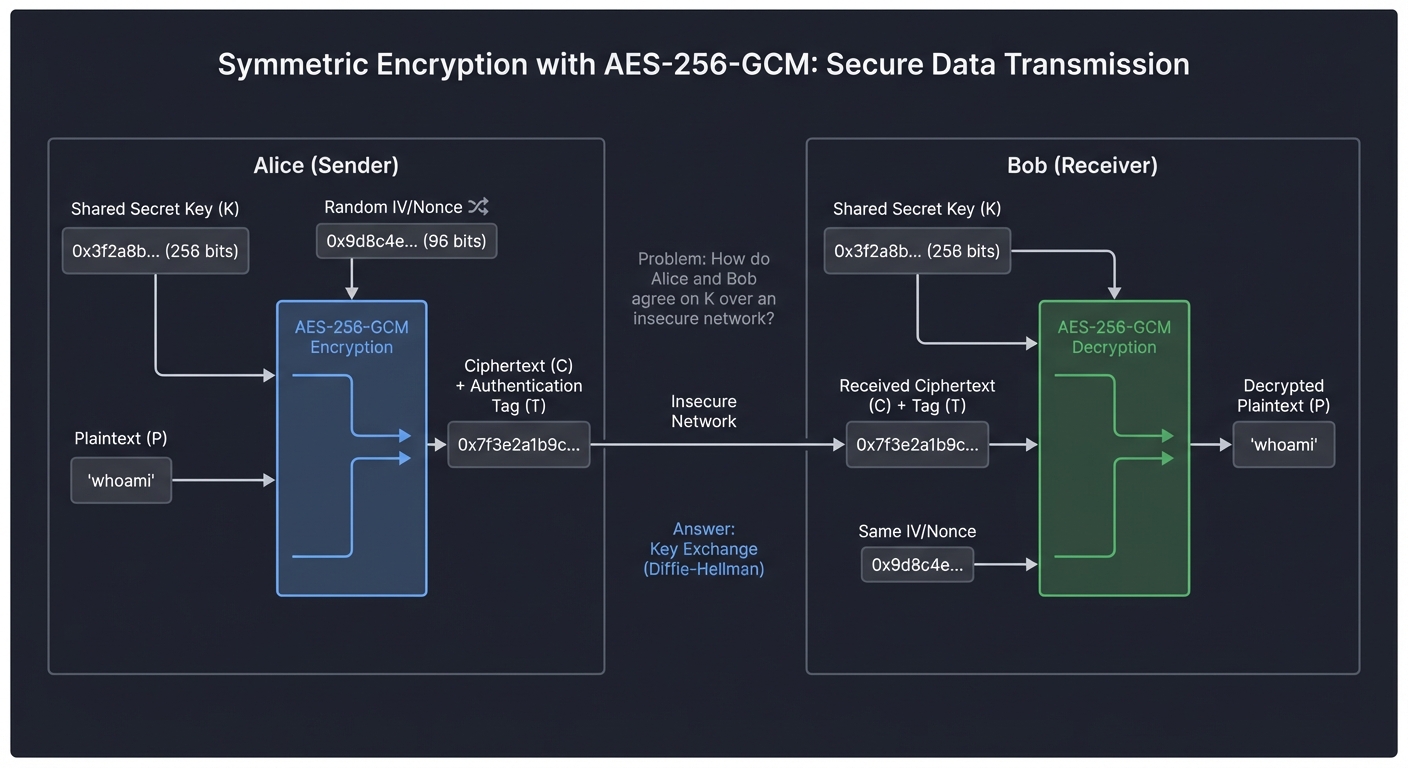

Symmetric Encryption (AES)

Symmetric encryption uses the same key for both encryption and decryption. It’s fast and efficient, making it perfect for bulk data encryption.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Symmetric Encryption (AES-256-GCM Example) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Alice Bob

│ │

│ Both share the same secret key: K = 0x3f2a8b... │

│ │

├─── Plaintext: "whoami" ───────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ │

│ ┌──────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ AES-256 Encrypt │ │ │

│ │ Key: K │ │ │

│ │ IV: random nonce │ │ │

│ └──────────────────────┘ │ │

│ ↓ │ │

├─── Ciphertext: 0x7f3e2a1b9c... ──────────────────────────►│ │

│ │ │

│ ┌──────────────────────┤ │

│ │ AES-256 Decrypt │ │

│ │ Key: K │ │

│ │ IV: same nonce │ │

│ └──────────────────────┘ │

│ ↓ │

│ Plaintext: "whoami" ◄───┘

│ │

Problem: How do Alice and Bob agree on K over an insecure network?

Answer: Key Exchange (Diffie-Hellman) - see next section!

Real Example in SSH: When you type ssh user@host, after the key exchange completes, all your keystrokes are encrypted with AES. A network sniffer sees random bytes, not your password or commands.

Book Reference: “Serious Cryptography” by Jean-Philippe Aumasson, Chapter 4 covers AES deeply—how it works, why it’s secure, and common pitfalls.

The “Why”: Why use symmetric crypto for data and not just public key crypto? Performance. AES can encrypt gigabytes per second on modern CPUs. RSA is 1000x slower. SSH uses public key crypto only for key exchange and authentication, then switches to symmetric crypto for actual data.

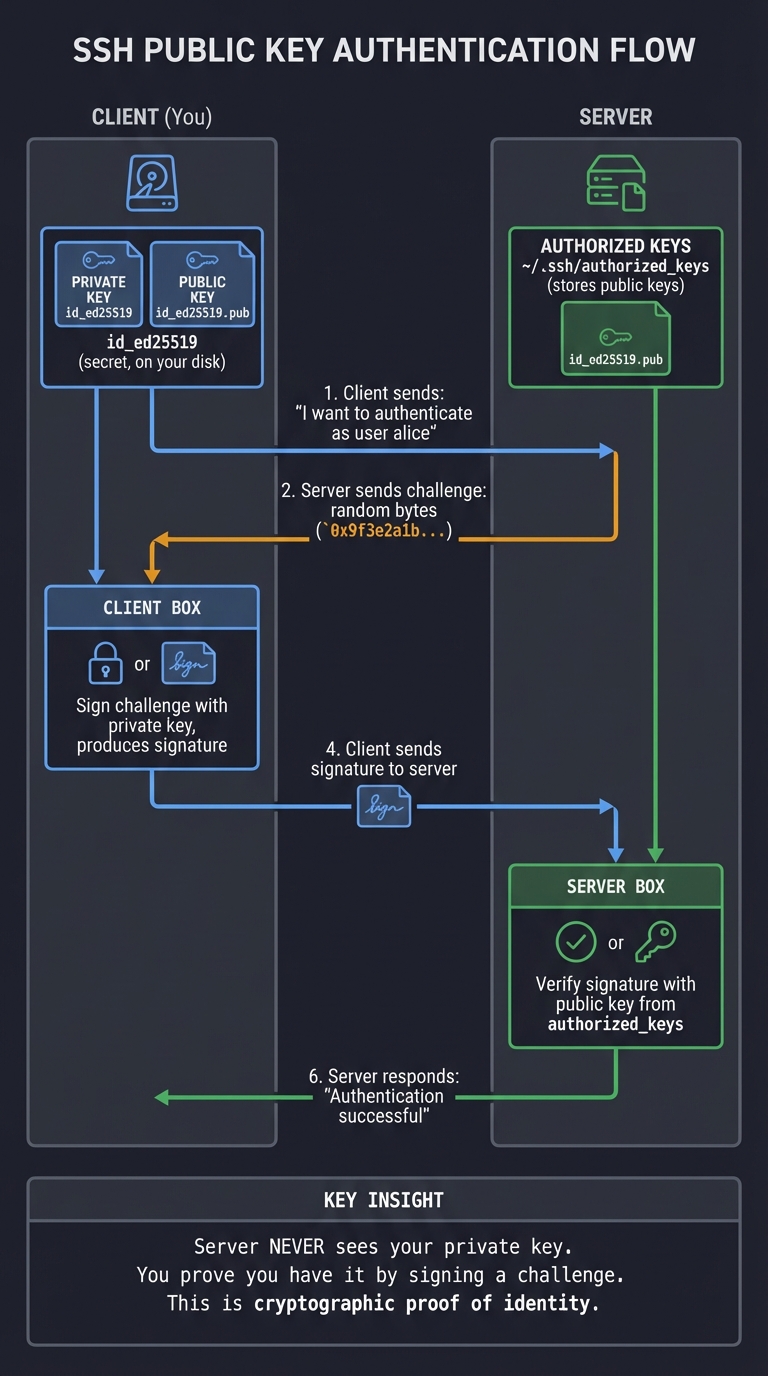

Asymmetric Encryption (RSA, Ed25519)

Asymmetric encryption uses a key pair: a public key (can be shared) and a private key (must be kept secret). What one key encrypts, only the other can decrypt.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Public Key Authentication (SSH Login Example) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Client (You) Server

│ │

│ Private Key: id_ed25519 (secret, on your disk) │

│ Public Key: id_ed25519.pub (in ~/.ssh/authorized_keys)

│ │

├──── "I want to authenticate as user 'alice'" ────►│

│ │

│ ◄───── Challenge: random bytes to sign ───────────┤

│ (0x9f3e2a1b...) │

│ │

│ ┌────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Sign challenge with │ │

│ │ private key │ │

│ │ Signature = Sign(data, │ │

│ │ privkey) │ │

│ └────────────────────────┘ │

│ ↓ │

├──── Send signature ───────────────────────────────►│

│ │

│ ┌────────────────────────────┤

│ │ Verify signature with │

│ │ public key from │

│ │ authorized_keys │

│ │ Verify(data, sig, pubkey) │

│ └────────────────────────────┘

│ ↓ │

│ ◄──── "Authentication successful" ─────────────────┤

│ │

Key Insight: Server NEVER sees your private key. You prove you have it

by signing a challenge. This is cryptographic proof of identity.

Real Example: Your ~/.ssh/id_ed25519 file is your private key. The server has your public key in ~/.ssh/authorized_keys. You can authenticate to infinite servers without ever sending your private key over the network.

Book Reference: “Serious Cryptography” Chapter 11 covers public key cryptography, including RSA, ECC, and modern algorithms like Ed25519.

The “Why”: Why use public key auth instead of passwords? Because passwords can be stolen, guessed, or phished. Your private key never leaves your machine. Even if the server is compromised, the attacker only gets your public key (which is… public).

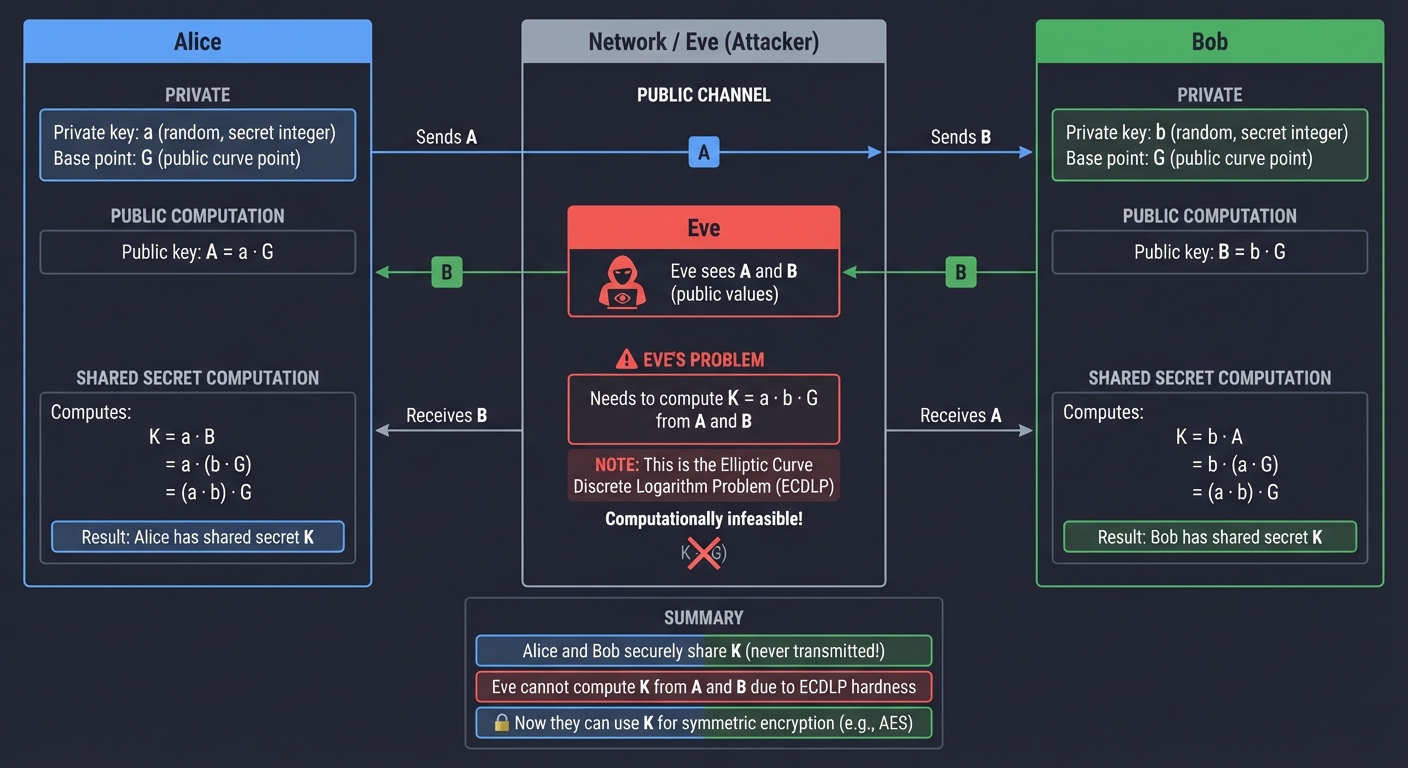

Key Exchange (Diffie-Hellman)

This is the magic that makes SSH possible. How do two parties who’ve never met before agree on a shared secret key over a network where attackers are listening?

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange (Simplified ECDH Example) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Alice Network (Eve listening) Bob

│ │ │

│ Private: a (random) │ Private: b (random)

│ Public: A = a·G │ Public: B = b·G │

│ (G = curve base point) │ │

│ │ │

├────── Send A ────────────────────┼──────────────────────────►│

│ │ │

│◄──────────────────────────────── ┼────────── Send B ─────────┤

│ │ │

│ Compute: K = a·B │ Compute: K = b·A │

│ = a·(b·G) │ = b·(a·G) │

│ = (a·b)·G │ = (a·b)·G │

│ │ │

│ Both have K! ──────────────────────── Both have K! │

│ │ │

│ │ │

Eve sees: A and B (public values) │ │

Eve needs: To compute a·b·G from A and B │

Problem: This is the Elliptic Curve Discrete Logarithm Problem │

(ECDLP) - believed to be computationally infeasible! │

Result: Alice and Bob share K, Eve cannot compute K

Now they can use K for AES encryption!

Real Example: When you connect to a new SSH server, you see “Server host key unknown” and a fingerprint. That handshake included a Diffie-Hellman exchange. Both sides now have a shared secret that was never transmitted.

Book Reference: “Serious Cryptography” Chapter 11, Section on Key Exchange. Also “Understanding Cryptography” by Paar & Pelzl, Chapter 10.

The “Why”: This solves the “key distribution problem” that plagued cryptography for centuries. Before Diffie-Hellman (invented 1976), two parties needed to meet in person to exchange keys. DH allows secure key agreement over insecure channels—this is foundational to all modern internet security (HTTPS, Signal, WhatsApp, SSH).

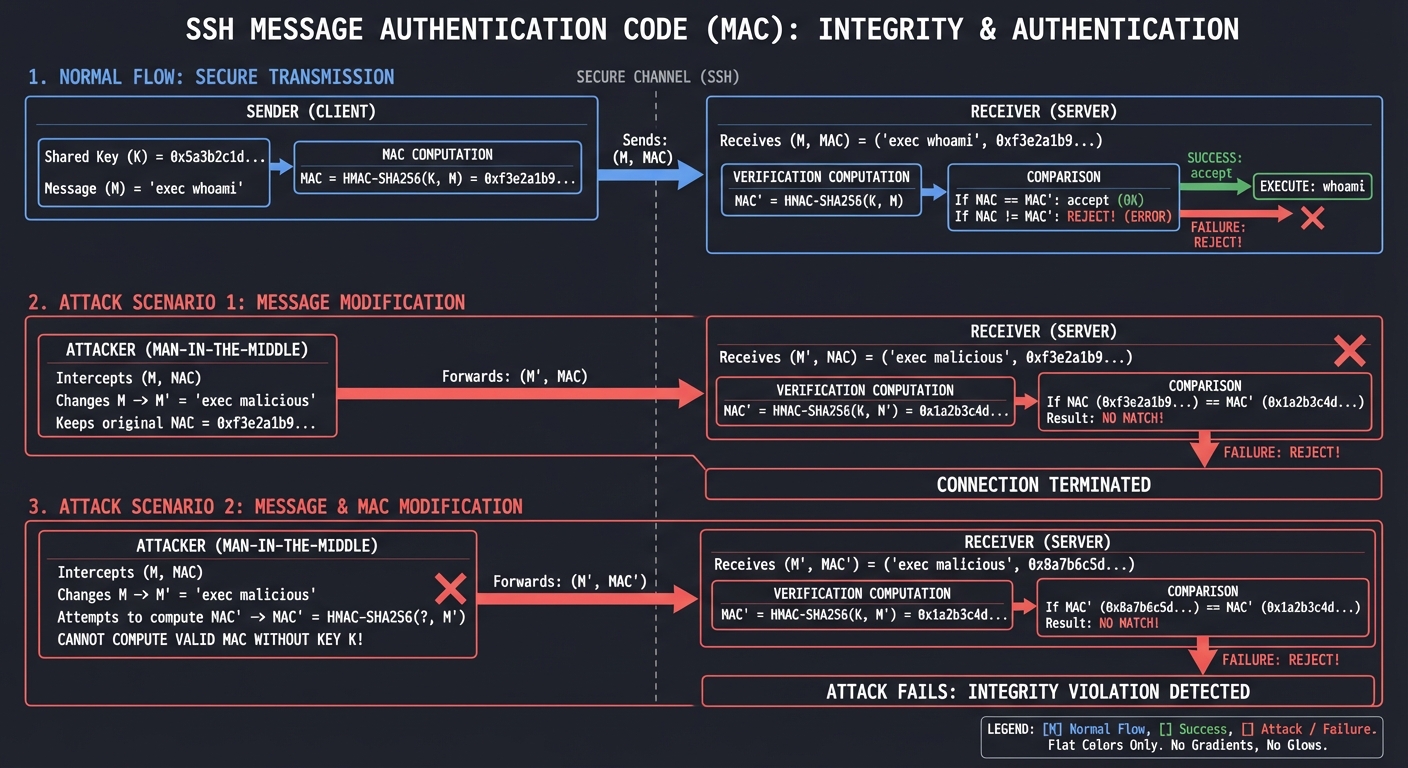

Message Authentication Codes (MACs)

Encryption provides confidentiality, but how do you know the ciphertext wasn’t modified in transit? MACs provide integrity and authenticity.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ MAC (Message Authentication Code) Example │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Sender Receiver

│ │

│ Shared Key: K │

│ Message: M = "exec whoami" │

│ │

│ ┌─────────────────────┐ │

│ │ MAC = HMAC-SHA256 │ │

│ │ (K, M) │ │

│ │ = 0xf3e2a1b9... │ │

│ └─────────────────────┘ │

│ ↓ │

├─── Send: (M, MAC) ────────────────────────────────────────►│

│ │

│ ┌───────────────────────────────┤

│ │ Compute MAC' = HMAC-SHA256 │

│ │ (K, M) │

│ │ If MAC == MAC': accept │

│ │ If MAC != MAC': REJECT! │

│ └───────────────────────────────┘

│ │

Attacker changes M to "exec rm -rf /" and keeps old MAC:

Server computes new MAC, doesn't match, connection terminated.

Attacker changes both M and MAC:

Can't compute valid MAC without key K. Attack fails.

Real Example in SSH: Every SSH packet includes a MAC. If an attacker tries to flip bits in your encrypted “whoami” command to make it “rm -rf /”, the MAC verification fails and SSH terminates the connection.

Book Reference: “Serious Cryptography” Chapter 6 covers MACs and authenticated encryption.

The “Why”: Encryption alone isn’t enough. Old encryption modes like AES-CBC are vulnerable to “bit-flipping attacks” where attackers modify ciphertext to change the resulting plaintext. MACs prevent this. Modern SSH uses AEAD (Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data) modes like AES-GCM that combine encryption and MAC in one operation.

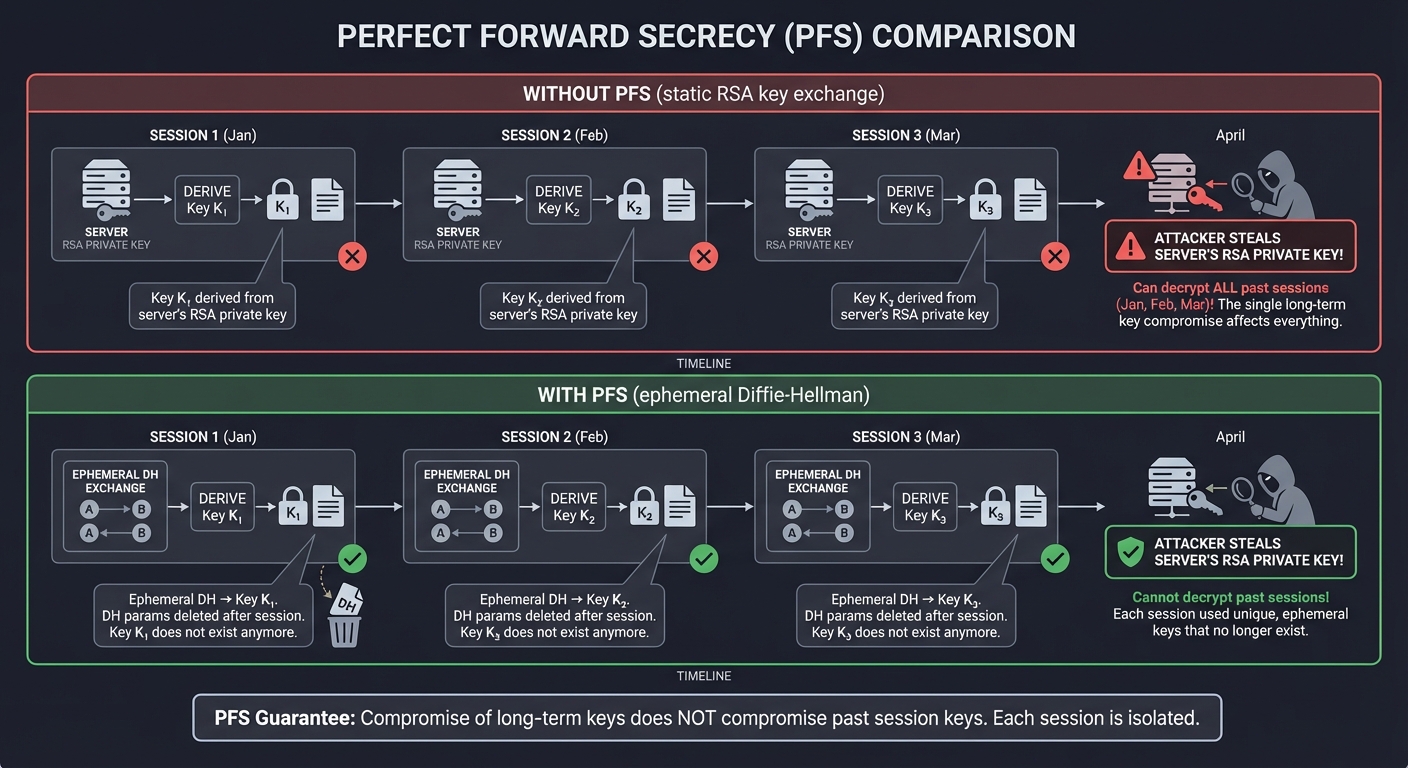

Perfect Forward Secrecy (PFS)

What if your server’s private key is stolen next year? Can an attacker who recorded all your past SSH sessions decrypt them?

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Perfect Forward Secrecy Visualization │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

WITHOUT PFS (static RSA key exchange):

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

Session 1 (Jan): Key K₁ derived from server's RSA private key

Session 2 (Feb): Key K₂ derived from server's RSA private key

Session 3 (Mar): Key K₃ derived from server's RSA private key

Attacker steals server's RSA private key in April:

⚠️ Can decrypt ALL past sessions (Jan, Feb, Mar)!

WITH PFS (ephemeral Diffie-Hellman):

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

Session 1 (Jan): Ephemeral DH → Key K₁ (DH params deleted)

Session 2 (Feb): Ephemeral DH → Key K₂ (DH params deleted)

Session 3 (Mar): Ephemeral DH → Key K₃ (DH params deleted)

Attacker steals server's RSA private key in April:

✅ Cannot decrypt past sessions!

✅ Each session used unique, ephemeral keys that no longer exist

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ PFS Guarantee: Compromise of long-term keys does NOT │

│ compromise past session keys. Each session is isolated. │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Real Example: Modern SSH defaults to curve25519-sha256 or diffie-hellman-group-exchange-sha256, which provide PFS. Even if your server is hacked and the host key stolen, past recorded sessions remain secure.

Book Reference: “Serious Cryptography” Chapter 11. Also see RFC 4419 for SSH’s Diffie-Hellman Group Exchange.

The “Why”: Nation-state adversaries and sophisticated attackers often record encrypted traffic in bulk (“collect now, decrypt later”). PFS ensures that even if they later compromise your server, those recordings are worthless. This is critical for long-term security.

2. Network Protocol: Understanding the Transport Layer

Why Network Protocols Matter for SSH

SSH doesn’t exist in a vacuum—it’s built on top of TCP/IP. Understanding how TCP works, how sockets provide an API to TCP, and how to design binary protocols is essential for implementing SSH.

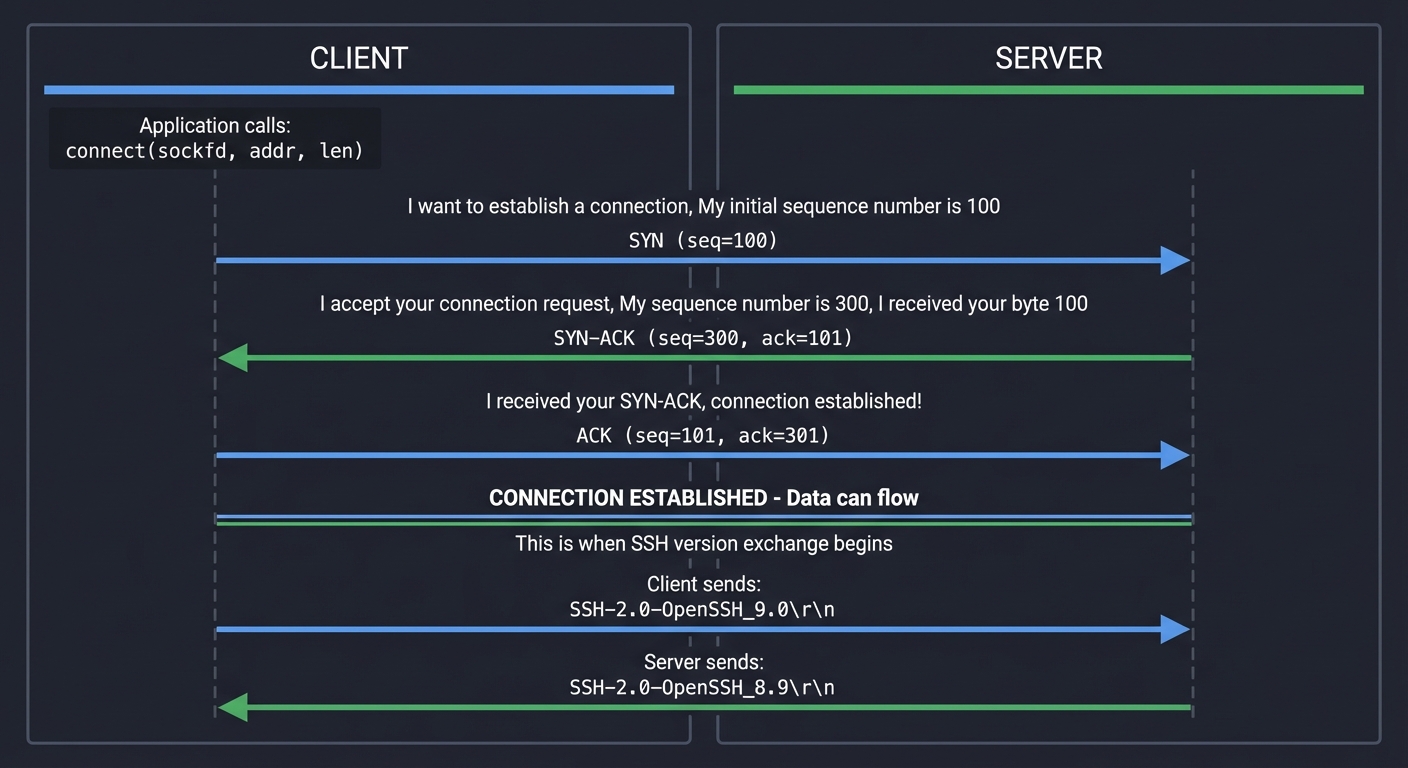

TCP: The Reliable Byte Stream

TCP provides a reliable, ordered, connection-oriented communication channel. Understanding TCP is crucial because SSH depends on these guarantees.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ TCP Three-Way Handshake (Connection Setup) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Client Server

│ │

│ ┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Application calls: connect(sockfd, addr, len) │ │

│ └────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ ↓ │

├─── SYN (seq=100) ─────────────────────────────────────────►│

│ │

│ "I want to establish a connection" │

│ My initial sequence number is 100 │

│ │

│ ◄─── SYN-ACK (seq=300, ack=101) ──────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ "I accept your connection request" │

│ My sequence number is 300, I received your byte 100 │

│ │

├─── ACK (seq=101, ack=301) ────────────────────────────────►│

│ │

│ "I received your SYN-ACK, connection established!" │

│ │

╞════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╡

│ CONNECTION ESTABLISHED - Data can flow │

│ (This is when SSH version exchange begins) │

╞════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╡

│ │

├─── SSH-2.0-OpenSSH_9.0\r\n ───────────────────────────────►│

│ ◄─── SSH-2.0-OpenSSH_8.9\r\n ──────────────────────────────┤

│ │

Real Example: When you run ssh user@host, your SSH client first establishes a TCP connection (port 22). Only after this handshake does SSH protocol communication begin.

Book Reference: “TCP/IP Illustrated, Volume 1” by Stevens, Chapter 13 (TCP Connection Management). This is the definitive guide to understanding TCP.

The “Why”: SSH relies on TCP’s reliability guarantees. SSH doesn’t have to worry about packets arriving out of order, being lost, or being duplicated—TCP handles all that. This lets SSH focus on security, not reliability.

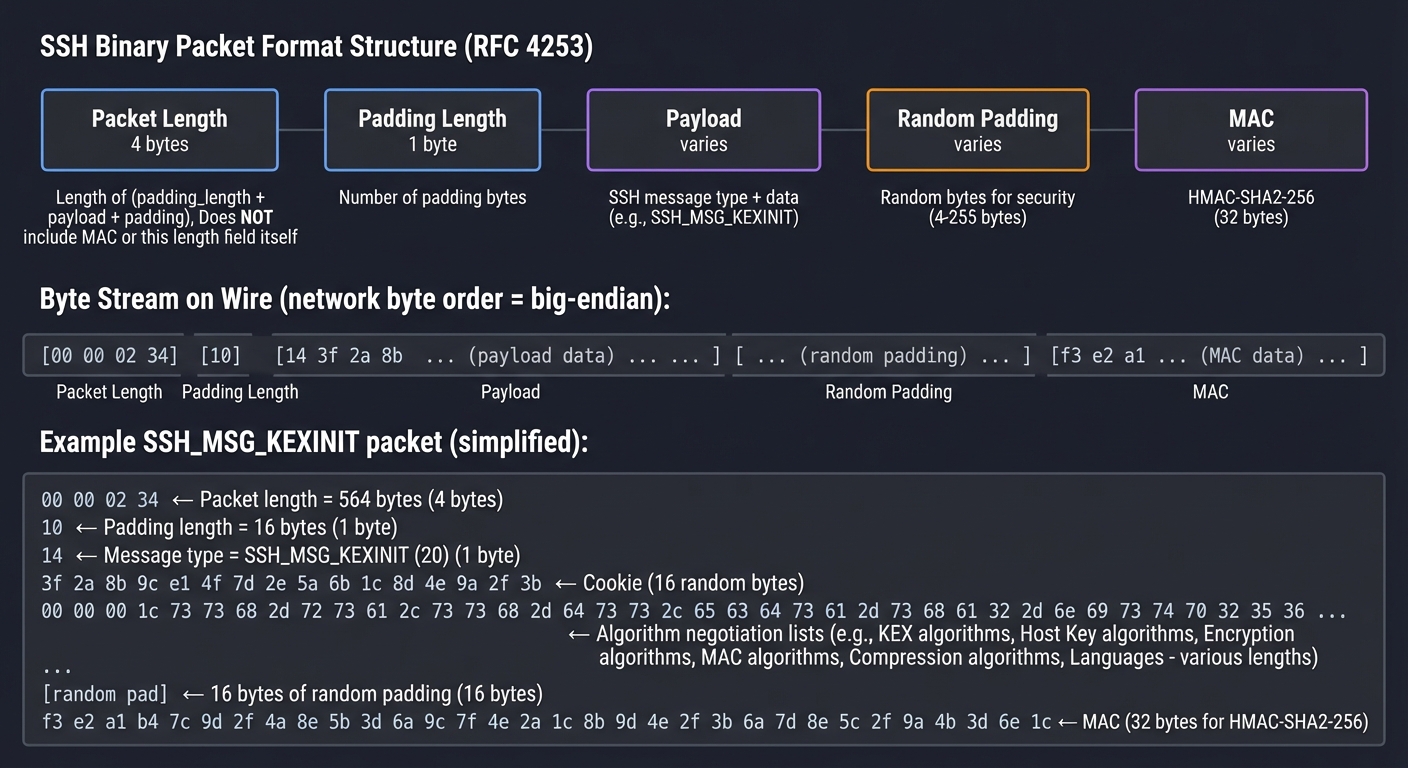

Binary Protocol Design

SSH is a binary protocol, not a text protocol like HTTP. Understanding binary protocol design is crucial.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ SSH Binary Packet Format (RFC 4253) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Byte Stream on Wire (network byte order = big-endian):

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

┌───────────────┬──────────┬─────────────┬──────────┬────────────┐

│ Packet Length │ Padding │ Payload │ Random │ MAC │

│ (4 bytes) │ Length │ (varies) │ Padding │ (varies) │

│ │ (1 byte) │ │ (varies) │ │

└───────────────┴──────────┴─────────────┴──────────┴────────────┘

│ │ │ │ │

│ │ │ │ └─ HMAC-SHA2-256

│ │ │ │ (32 bytes)

│ │ │ │

│ │ │ └─ Random bytes for security

│ │ │ (4-255 bytes)

│ │ │

│ │ └─ SSH message type + data

│ │ (e.g., SSH_MSG_KEXINIT)

│ │

│ └─ Number of padding bytes

│

└─ Length of (padding_length + payload + padding)

Does NOT include MAC or this length field itself

Example SSH_MSG_KEXINIT packet (simplified):

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

00 00 02 34 ← Packet length = 564 bytes

10 ← Padding length = 16 bytes

14 ← Message type = SSH_MSG_KEXINIT (20)

3f 2a 8b ... ← Cookie (16 random bytes)

00 00 00 ... ← Algorithm negotiation lists

...

[random pad] ← 16 bytes of random padding

f3 e2 a1 ... ← MAC (32 bytes for HMAC-SHA2-256)

Real Example: When you run Wireshark on an SSH connection, you see these binary packets. Understanding this format lets you parse SSH traffic (Project 2).

Book Reference: “TCP/IP Illustrated, Volume 1” Chapter 18 discusses protocol design principles. SSH RFCs 4253-4254 define SSH’s binary formats.

The “Why”: Binary protocols are more efficient than text protocols. Instead of “Content-Length: 1234\r\n”, SSH uses 4 bytes. This matters for high-throughput applications. Also, binary encoding is less ambiguous—no worrying about character encoding, whitespace, or parsing edge cases.

Concept Summary Table

This table maps each major concept cluster to what you need to internalize (not just memorize) to truly understand SSH:

| Concept Cluster | Core Understanding Required | Why It Matters | Projects That Teach This |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetric Crypto (AES) | How block ciphers work, cipher modes (CBC, GCM), why IV/nonce is critical, authenticated encryption | This is what encrypts your actual SSH data. Bulk encryption must be fast. | Project 1 (TCP Chat) |

| Asymmetric Crypto (RSA, Ed25519) | Public/private key pairs, digital signatures, why private keys must stay private | This enables authentication without passwords and key exchange signatures | Project 3 (Mini SSH Client), Project 5 (Host Key Manager) |

| Key Exchange (DH, ECDH) | How two parties agree on a secret over insecure channel, ephemeral vs static keys, perfect forward secrecy | This is THE magic that makes SSH possible. Solves the key distribution problem. | Project 1 (TCP Chat - implement DH), Project 3 (Mini SSH Client) |

| MACs & Hashing | HMAC construction, why encrypt-then-MAC, collision resistance, cryptographic vs non-cryptographic hashes | Provides integrity and authenticity. Prevents tampering. | Project 1 (adding MACs), Project 3 (protocol implementation) |

| TCP Sockets | socket(), bind(), listen(), accept(), connect(), read(), write(), network byte order | SSH runs on TCP. Must understand the transport layer to build on it. | Project 1 (TCP Chat - foundation) |

| Binary Protocols | Parsing binary data, endianness, length-prefixed vs delimited, packet framing | SSH is a binary protocol. Text-based thinking won’t work. | Project 2 (Protocol Dissector), Project 3 (Mini SSH Client) |

| Password Auth | Challenge-response, timing attacks, why password hashing matters | Understand the weakest link to appreciate stronger methods | Project 3 (Mini SSH Client - implement auth) |

| Public Key Auth | Challenge-response with signatures, authorized_keys format, key fingerprints | The strongest practical authentication method. Industry standard. | Project 3, Project 5 (Host Key Manager) |

| Host Key Verification | Trust-On-First-Use (TOFU) model, known_hosts format, fingerprint verification, MITM prevention | Critical for security. Most users skip this—you’ll understand why it matters. | Project 5 (Host Key Manager) |

| Port Forwarding | Local vs remote forwarding, channel multiplexing, TCP-in-TCP | SSH’s killer feature beyond remote shell. Understand VPN-like capabilities. | Project 4 (Tunnel Tool) |

| SOCKS Proxy | SOCKS5 protocol, dynamic forwarding, proxy vs VPN | Powerful tool for routing arbitrary traffic through SSH | Project 4 (Tunnel Tool) |

| MITM Attacks | How network interception works, ARP spoofing, DNS hijacking, why host keys matter | Understanding the threat model makes SSH’s design decisions clear | Project 2 (observe real traffic), Project 5 (security analysis) |

| Replay Attacks | Why encryption alone isn’t enough, sequence numbers, freshness | Subtle attack that many protocols get wrong. SSH gets it right. | Project 3 (implement sequence numbers) |

| Perfect Forward Secrecy | Ephemeral keys, why past sessions must stay secure, post-compromise security | Modern security requirement. Understand long-term vs session security. | Project 1 (ephemeral DH), Project 3 (key exchange) |

Deep Dive Reading By Concept

This section maps each concept to specific chapters/sections in recommended books for deeper understanding:

Cryptography Foundations

Start here: “Serious Cryptography, 2nd Edition” by Jean-Philippe Aumasson

- Chapter 1: Encryption - Understanding confidentiality

- Chapter 4: Block Ciphers (AES) - How AES works, cipher modes, padding

- Chapter 6: Message Authentication - MACs, HMAC, authenticated encryption (AES-GCM)

- Chapter 11: Public Key Cryptography - RSA, ECC, Diffie-Hellman, digital signatures

- Chapter 8: Key Derivation - How SSH derives multiple keys from one shared secret

Alternative/Supplement: “Understanding Cryptography” by Paar & Pelzl

- Chapter 4: AES (more mathematical depth than Aumasson)

- Chapter 7: RSA

- Chapter 10: Diffie-Hellman and Elliptic Curves

- Chapter 12: MACs

For implementation details: “Cryptography Engineering” by Ferguson, Schneier, & Kohno

- Chapter 6: Implementing Block Ciphers (practical issues like side-channels)

- Chapter 8: Authentication and Integrity (practical MAC implementation)

Network Programming

TCP/IP Fundamentals: “TCP/IP Illustrated, Volume 1, 2nd Edition” by Fall & Stevens

- Chapter 1: Introduction (OSI model, protocols, encapsulation)

- Chapter 13: TCP Connection Management (three-way handshake, connection state)

- Chapter 14: TCP Data Flow (how data actually moves through TCP)

- Chapter 15: TCP Timeout and Retransmission (reliability mechanisms)

Socket Programming in C: “TCP/IP Sockets in C, 2nd Edition” by Donahoo & Calvert

- Chapter 1: Introduction (basic socket concepts)

- Chapter 2: Basic TCP Sockets (connect, send, receive)

- Chapter 3: Constructing Messages (framing, byte order)

- Chapter 4: Using UDP Sockets (for contrast with TCP)

- Chapter 6: Beyond Basic Socket Programming (non-blocking I/O, multiplexing with select/poll)

Systems-level Socket Programming: “The Linux Programming Interface” by Kerrisk

- Chapters 56-61: Sockets (comprehensive coverage, Linux-specific details)

- Chapter 63: Advanced Socket Topics (non-blocking I/O, /dev/poll, epoll)

SSH Protocol Specifics

Practical SSH Usage: “SSH Mastery, 2nd Edition” by Michael W. Lucas

- Chapter 1: Introducing SSH (overview, use cases)

- Chapter 2: Key Concepts (keys, agents, forwarding)

- Chapter 4: Verifying Server Identity (host keys, known_hosts, TOFU)

- Chapter 6: Public Key Authentication (how it works, key management)

- Chapter 9: Port Forwarding (local, remote, dynamic)

- Chapter 12: SSH Automation (for understanding production usage patterns)

Protocol Specifications (dense but authoritative):

- RFC 4251: SSH Protocol Architecture (read first for overview)

- RFC 4253: SSH Transport Layer Protocol (key exchange, encryption, packet format)

- RFC 4252: SSH Authentication Protocol (password, public key auth)

- RFC 4254: SSH Connection Protocol (channels, port forwarding, shell sessions)

- RFC 4419: Diffie-Hellman Group Exchange for SSH (modern key exchange)

Systems Programming for SSH Implementation

Unix/Linux Systems: “Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment, 3rd Edition” by Stevens & Rago

- Chapter 13: Daemon Processes (for SSH server implementation)

- Chapter 14: Advanced I/O (non-blocking I/O, I/O multiplexing, async I/O)

- Chapter 15: Interprocess Communication (needed for privilege separation)

- Chapter 16: Network IPC (socket internals)

Comprehensive Linux Reference: “The Linux Programming Interface” by Kerrisk

- Chapter 44: Pipes and FIFOs (for session management)

- Chapter 60: Sockets: Server Design (iterative vs concurrent servers)

- Chapter 61: Advanced Socket Topics

Security and Threat Modeling

Information Security Foundations: “Foundations of Information Security” by Andress

- Chapter 8: Network Security (MITM, sniffing, replay attacks)

- Chapter 9: Cryptography (security properties, attack models)

Network Security Monitoring: “The Practice of Network Security Monitoring” by Bejtlich

- Chapter 6: Packet Analysis (understanding network traffic)

- Chapter 8: Security Logging and Monitoring (audit trails)

Practical Packet Analysis: “Practical Packet Analysis, 3rd Edition” by Chris Sanders

- Chapter 2: Tapping into the Wire (packet capture)

- Chapter 4: Working with Captured Packets

- Chapter 9: Analyzing TCP (understanding TCP from a security perspective)

Applied Cryptography in Systems

Building Secure Systems: “Security Engineering, 3rd Edition” by Ross Anderson

- Chapter 5: Cryptography (real-world crypto usage and pitfalls)

- Chapter 21: Network Attack and Defense (SSH in context of network security)

Side-Channel Attacks: “Fluent C” by Preschern (for implementation safety)

- Chapter 8: Data Structures (binary parsing, safe memory access)

- Chapter 12: Security (avoiding timing attacks, secure coding)

Prerequisites & Background Knowledge

Before diving into these SSH implementation projects, it’s important to assess your readiness and prepare your development environment. This section will help you determine if you’re ready to start and what you’ll need.

Essential Prerequisites (Must Have)

You must have these skills before starting Project 1:

- C Programming Fundamentals

- Pointers, structs, arrays, memory allocation (

malloc/free) - File I/O and error handling

- Understanding of undefined behavior and memory safety

- Comfortable reading C code and debugging with gdb

- Pointers, structs, arrays, memory allocation (

- Command Line Proficiency

- Unix/Linux command line navigation

- Basic shell scripting

- Using compilers (

gcc/clang) and build tools (make) - Running network diagnostic tools (

nc,telnet,ping)

- Basic Networking Concepts

- TCP/IP fundamentals (IP addresses, ports)

- Client-server model

- What happens when you type a URL in a browser

- Basic understanding of network layers (OSI or TCP/IP model)

- Mathematical Foundations

- Basic algebra and modular arithmetic

- Understanding of what logarithms are

- Comfortable with hexadecimal and binary number systems

Helpful But Not Required (You’ll Learn These During Projects)

These topics will be covered in depth through the projects—don’t worry if you don’t know them yet:

- Advanced Socket Programming:

select(),poll(), multiplexing, non-blocking I/O - Cryptography: You don’t need to understand AES, RSA, or Diffie-Hellman yet—the projects will teach you

- Binary Protocol Parsing: This is learned through Project 2

- Process Management:

fork(), signals, daemon programming (needed for later projects) - Security Concepts: Threat modeling, attack vectors, defense-in-depth

Self-Assessment Questions

Answer these honestly to gauge your readiness:

C Programming:

- Can you explain what happens when you call

malloc()andfree()? - Do you know the difference between stack and heap memory?

- Can you debug a segmentation fault using gdb?

- Have you written a program that reads/writes binary files?

Networking:

- Do you know what TCP ports are and how they differ from UDP?

- Can you explain what a socket is at a conceptual level?

- Have you used

telnetorncto connect to a server manually?

Tools:

- Can you compile a multi-file C project using

make? - Do you know how to use

manpages to look up function documentation? - Can you capture network packets with Wireshark or tcpdump?

If you answered “no” to more than 3 questions: Spend 1-2 weeks on C programming fundamentals and basic networking before starting. Recommended resources:

- “The C Programming Language” by Kernighan & Ritchie - Chapters 1-6

- “Beej’s Guide to Network Programming” (free online)

- CS50 course videos on C programming

If you answered “yes” to most questions: You’re ready for Project 1!

Development Environment Setup

You’ll need this software installed:

Required Tools

# On Ubuntu/Debian:

sudo apt-get install build-essential libssl-dev libpcap-dev \

wireshark tcpdump gdb valgrind git

# On macOS (with Homebrew):

brew install openssl libpcap wireshark gdb

# On Fedora/RHEL:

sudo dnf install gcc make openssl-devel libpcap-devel \

wireshark tcpdump gdb valgrind git

Recommended Tools

- Text Editor/IDE: VS Code, Vim, Emacs (your choice)

- Version Control: Git (for saving your work)

- Hex Editor:

hexdump,xxd, or a GUI hex editor - Virtual Machines: VirtualBox or VMware (for testing client/server on separate machines)

Verification Test

Run this to verify your environment is ready:

# Test OpenSSL installation

echo "Testing OpenSSL..."

echo -n "Hello" | openssl enc -aes-256-cbc -K 0123456789abcdef0123456789abcdef0123456789abcdef0123456789abcdef -iv 00000000000000000000000000000000 | xxd

# Test packet capture permissions (may need sudo)

echo "Testing libpcap..."

sudo tcpdump -i any -c 1

# Test compiler

echo "Testing GCC..."

echo 'int main() { return 0; }' | gcc -x c - -o /tmp/test && /tmp/test && echo "✓ GCC works"

If all three commands succeed, your environment is ready!

Time Investment Expectations

Be realistic about time commitments:

| Project | Typical Time | Fast (Experienced) | Slow (Learning) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Project 1 | 2-3 weeks | 1 week | 1 month |

| Project 2 | 1-2 weeks | 3 days | 3 weeks |

| Project 3 | 2-3 weeks | 1 week | 1 month |

| Project 4 | 1-2 weeks | 4 days | 3 weeks |

| Project 5 | 3-4 weeks | 2 weeks | 6 weeks |

Total: 2-4 months working evenings/weekends, or 6-12 months at a relaxed pace.

These are learning projects, not production code—don’t rush! The time you spend debugging and understanding why something works is where the deepest learning happens.

Important Reality Check

⚠️ These projects are hard. SSH is a complex, security-critical protocol. You will:

- Get stuck frequently (this is normal and good)

- Encounter bugs that take hours to debug

- Read RFCs that feel like a foreign language at first

- Question whether you’re “good enough” (you are)

The payoff: After completing these projects, you’ll understand network security at a level that 99% of developers never reach. You’ll be able to:

- Debug any network protocol issue

- Read and understand security code in the wild

- Design secure systems from first principles

- Answer any interview question about SSH, TLS, or network security

This knowledge compounds—everything you learn here applies to understanding TLS, VPNs, WebSockets, and any other network security protocol.

Recommended Learning Path

If you’re completely new to networking: Start with Project 1, spend extra time on the TCP socket programming sections. Don’t skip to later projects.

If you have networking experience but not security/crypto: Project 1 will teach you the crypto fundamentals. Take your time with the Diffie-Hellman implementation.

If you’re a security professional learning implementation: You might skim Project 1’s crypto sections but pay close attention to the implementation details and common pitfalls.

If you want to contribute to OpenSSH or similar projects: Complete all projects in order and compare your implementations with OpenSSH source code.

Quick Start Guide (For the Overwhelmed)

Feeling overwhelmed by the scope? Here’s your first 48 hours action plan:

Day 1 Morning (3 hours): TCP Echo Server

Goal: Get comfortable with socket programming.

- Read “TCP/IP Sockets in C” Chapter 1 (30 mins)

- Write a basic echo server:

socket()→bind()→listen()→accept()→recv()/send()loop - Write a basic client:

socket()→connect()→send()/recv() - Test them: client sends “Hello”, server echoes it back

- Capture the traffic in Wireshark and see your plaintext message

Success criteria: You can type in the client and see the message appear on the server.

Day 1 Afternoon (3 hours): Add Simple Encryption

Goal: Feel the pain of key distribution.

- Read “Serious Cryptography” Chapter 4 intro to AES (30 mins)

- Add AES-256-CBC encryption using OpenSSL’s EVP API

- Hardcode the same key in both client and server

- Encrypt messages before send, decrypt after receive

- Capture in Wireshark again—now it’s gibberish!

Success criteria: Your messages still work end-to-end, but Wireshark shows encrypted garbage.

Day 2 Morning (4 hours): Understand the Key Problem

Goal: Realize why Diffie-Hellman is necessary.

- Try to distribute the key somehow without hardcoding:

- Prompt user for key? (insecure, awkward)

- Send key over network? (defeats encryption!)

- Read from file? (key distribution problem persists)

- Read “Serious Cryptography” Chapter 11 on Diffie-Hellman (1 hour)

- Do the paper-and-pencil DH exercise in Project 1’s “Thinking Exercise” section

Success criteria: You understand conceptually how two parties can agree on a secret without ever transmitting it.

Day 2 Afternoon (4-5 hours): Implement Basic DH

Goal: Experience the “magic” of key exchange.

- Server generates (p, g) parameters at startup

- Server generates private key

a, computes public keyA = g^a mod p - Send (p, g, A) to client over plaintext connection

- Client generates private key

b, computes public keyB = g^b mod p - Client sends B to server

- Both sides compute shared secret:

s = A^b mod p = B^a mod p - Derive AES key from s using SHA-256

- Use that AES key to encrypt chat messages

Success criteria: Your chat still works, but now the AES key was never transmitted!

Weekend Goal

By the end of your first 48 hours (spread over a weekend), you should have:

- ✅ A working TCP client/server

- ✅ Encryption added (even if with hardcoded key first)

- ✅ Basic understanding of why DH is needed

- ✅ A working DH key exchange implementation

What’s next? You’ve now completed 70% of Project 1. The remaining work is polishing the protocol, adding message framing, handling edge cases, and studying the security implications.

Project 1: TCP Chat with Progressive Encryption (Foundation)

- File: SSH_DEEP_DIVE_LEARNING_PROJECTS.md

- Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Go, Python

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Network Security / Cryptography

- Software or Tool: Sockets / AES / OpenSSL

- Main Book: “Serious Cryptography” by Jean-Philippe Aumasson

What you’ll build: A client-server chat application over TCP where you manually implement encryption layers—first plaintext, then adding symmetric encryption (AES), then key exchange.

Why it teaches SSH: SSH is fundamentally “encrypted TCP with authentication.” By building a chat app and progressively adding encryption layers, you experience exactly why each SSH component exists. You’ll feel the pain of key distribution that Diffie-Hellman solves.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Implementing TCP socket communication in C (maps to SSH transport layer)

- Adding AES encryption and understanding block cipher modes (maps to SSH encryption)

- Implementing Diffie-Hellman key exchange (maps to SSH key exchange)

- Handling binary protocol framing (maps to SSH packet structure)

Resources for key challenges:

- “TCP/IP Sockets in C, 2nd Edition” by Donahoo & Calvert (Ch. 1-4) - Best practical intro to socket programming in C

- “Serious Cryptography, 2nd Edition” by Jean-Philippe Aumasson (Ch. 4-5, 11) - Clear explanation of AES and Diffie-Hellman

Key Concepts:

- TCP Sockets: “The Sockets Networking API” by Stevens, Fenner & Rudoff - Ch. 4

- AES Encryption: “Serious Cryptography” by Aumasson - Ch. 4

- Diffie-Hellman: “Serious Cryptography” by Aumasson - Ch. 11

- Binary Protocol Design: “TCP/IP Illustrated, Volume 1” by Stevens - Ch. 18

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 2-3 weeks Prerequisites: Basic C programming, understanding of TCP/IP basics

Real world outcome:

- Two terminals on different machines (or localhost ports) exchanging encrypted messages

- Wireshark capture showing encrypted gibberish instead of plaintext

- Visual demonstration: run without encryption (readable), then with encryption (unreadable)

Learning milestones:

- Plaintext chat working → You understand TCP socket programming

- AES encryption added → You understand symmetric encryption and why key sharing is hard

- Diffie-Hellman added → You understand how SSH establishes shared secrets over insecure channels

Real World Outcome (Expanded)

This project produces tangible, demonstrable results that prove your understanding:

Scenario 1: Plaintext Communication (Baseline)

# Terminal 1 (Server)

$ ./chat_server 8888

Server listening on port 8888...

Client connected from 192.168.1.100:52341

[Client]: Hey, what's the password?

[You]: The password is "secret123"

# Terminal 2 (Client)

$ ./chat_client localhost 8888

Connected to server!

[You]: Hey, what's the password?

[Server]: The password is "secret123"

In Wireshark, you see:

TCP Stream 1:

Hey, what's the password?

The password is "secret123"

☠️ Completely readable! Anyone on the network can see everything.

Scenario 2: AES-Encrypted Communication (Pre-shared Key)

# Terminal 1 (Server)

$ ./chat_server 8888 --aes-key "0123456789abcdef0123456789abcdef"

Server listening on port 8888...

Using AES-256-CBC encryption

Client connected from 192.168.1.100:52341

[Client]: Hey, what's the password?

[You]: The password is "secret123"

# Terminal 2 (Client)

$ ./chat_client localhost 8888 --aes-key "0123456789abcdef0123456789abcdef"

Connected to server!

Using AES-256-CBC encryption

[You]: Hey, what's the password?

[Server]: The password is "secret123"

In Wireshark, you see:

TCP Stream 1:

.8.K...?..m....e.Q...4.......v...........

...R..5.h...9...P.......Y.................

✅ Encrypted! But there’s a problem: how did both sides get the same key?

Scenario 3: Full Encryption with Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange

# Terminal 1 (Server)

$ ./chat_server 8888 --dh-kex

Server listening on port 8888...

Waiting for Diffie-Hellman key exchange...

Client connected from 192.168.1.100:52341

DH Parameters: p=FFFFFFFFFFFFFF... g=2

Server private key generated: [hidden]

Received client public key: 0x7a3e9f2b...

Server public key sent: 0x4c8d1e6a...

Shared secret computed: 0x9f2e4a7c...

Derived AES key: 0xa7c3f19e8b4d2e6f...

Secure channel established!

[Client]: Hey, what's the password?

[You]: The password is "secret123"

# Terminal 2 (Client)

$ ./chat_client localhost 8888 --dh-kex

Connecting to localhost:8888...

Connected! Starting Diffie-Hellman key exchange...

Received server DH parameters: p=FFF... g=2

Client private key generated: [hidden]

Client public key sent: 0x7a3e9f2b...

Received server public key: 0x4c8d1e6a...

Shared secret computed: 0x9f2e4a7c...

Derived AES key: 0xa7c3f19e8b4d2e6f...

Secure channel established!

[You]: Hey, what's the password?

[Server]: The password is "secret123"

In Wireshark, you see:

TCP Stream 1:

[Handshake Phase - plaintext DH public keys]

Client→Server: DH_PUBLIC_KEY: 0x7a3e9f2b4c8d1e6a...

Server→Client: DH_PUBLIC_KEY: 0x4c8d1e6a9f2e4a7c...

[Encrypted Phase - ciphertext]

Client→Server: .L..q....8.K...?..m....e.Q

Server→Client: ...R..5.h...9...P.......Y..

🎉 Perfect! The public keys are exchanged openly, but:

- An eavesdropper sees the public keys but cannot compute the shared secret (discrete logarithm problem)

- Both client and server independently compute the same AES key

- All messages after key exchange are encrypted

- No pre-shared secret was needed!

What You Can Demonstrate:

- Run all three versions side-by-side in Wireshark

- Show that plaintext is readable, encrypted is not

- Explain why pre-shared keys don’t scale (every client needs same key)

- Show how DH solves the key distribution problem

- Capture and analyze the full handshake sequence

The Core Question You’re Answering

“If I want to send you an encrypted message, but we’ve never met before and can’t meet in person to exchange keys, and everyone can see our communication, how can we possibly agree on a secret encryption key?”

This is the key distribution problem, and it’s the fundamental challenge that makes cryptography hard in the real world.

SSH solves this with Diffie-Hellman key exchange. Before DH, you needed:

- In-person key exchange (impractical for internet-scale)

- Trusted couriers (expensive, slow)

- Pre-shared keys (doesn’t scale, key management nightmare)

With DH, two parties can:

- Communicate entirely over a public channel

- Exchange mathematical values that everyone can see

- Each independently compute the same secret

- Use that secret as an encryption key

- All while an eavesdropper learns nothing

This project makes you feel why DH is revolutionary. You’ll implement plaintext (insecure), pre-shared keys (doesn’t scale), then DH (elegant solution). The “aha moment” when your DH implementation works is when you truly understand how SSH establishes secure channels.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Before writing a single line of code, you need solid understanding of these foundations:

1. TCP Socket Programming in C

Questions you should answer:

- What is the difference between

socket(),bind(),listen(), andaccept()? - Why does the server need

bind()but the client doesn’t? - What is the purpose of the backlog parameter in

listen()? - How do

send()andrecv()differ fromwrite()andread()? - What happens if you try to

recv()on a socket and no data is available? - Why must you check the return value of

send()and potentially call it multiple times?

Book Reference:

- “TCP/IP Sockets in C, 2nd Edition” by Donahoo & Calvert - Chapters 1-3

- “The Linux Programming Interface” by Kerrisk - Chapter 56-61 (Sockets)

2. Symmetric Encryption (AES)

Questions you should answer:

- What does it mean that AES is a “block cipher” with a 128-bit block size?

- Why do we need padding, and what is PKCS#7 padding?

- What is an Initialization Vector (IV), and why must it be random and unique?

- Why can’t you reuse the same IV with the same key?

- What is CBC mode, and how does each ciphertext block depend on all previous plaintext?

- How do you securely transmit the IV (hint: it doesn’t need to be secret, just unpredictable)?

Book Reference:

- “Serious Cryptography” by Aumasson - Chapter 4 (Block Ciphers)

- “Cryptography Engineering” by Ferguson, Schneier, Kohno - Chapter 4 (Block Cipher Modes)

3. Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange

Questions you should answer:

- What are the public parameters (p, g) and why can everyone know them?

- What are the private keys (a, b) and why must they never be shared?

- How do you compute public keys (A = g^a mod p, B = g^b mod p)?

- How does each side compute the same shared secret (s = B^a mod p = A^b mod p)?

- Why can’t an eavesdropper who sees A and B compute s? (discrete logarithm problem)

- What is the difference between static DH and ephemeral DH (DHE)?

Book Reference:

- “Serious Cryptography” by Aumasson - Chapter 11 (Key Exchange)

- “Understanding Cryptography” by Paar & Pelzl - Chapter 10

4. Binary Protocol Design

Questions you should answer:

- Why can’t you just send length-prefixed strings for encrypted data?

- What is network byte order (big-endian) and why does it matter?

- How do you use

htonl()andntohl()for integer serialization? - What is a Type-Length-Value (TLV) encoding?

- Why should message framing happen before encryption?

- How do you handle partial

recv()calls that don’t receive a full message?

Book Reference:

- “TCP/IP Illustrated, Volume 1” by Stevens - Chapter 1 (byte order), Chapter 18 (protocol design)

- “Beej’s Guide to Network Programming” (free online) - Section 7.4 (Serialization)

5. Modular Arithmetic for DH

Questions you should answer:

- What does “a mod p” mean, and why is it a one-way function?

- How do you efficiently compute (g^a mod p) for large a? (hint: not literally ggg*… a times)

- What is modular exponentiation, and why is the naive approach too slow?

- What is the square-and-multiply algorithm?

- Why must p be a large prime number (2048+ bits)?

- What makes certain primes “safe primes” for DH?

Book Reference:

- “An Introduction to Mathematical Cryptography” by Hoffstein et al. - Chapter 2

- “Serious Cryptography” by Aumasson - Chapter 11.2 (DH Math)

6. Memory Safety in C with Cryptographic Data

Questions you should answer:

- Why must you zero sensitive buffers (keys, plaintexts) after use?

- What is

memset_s()orexplicit_bzero(), and why is plainmemset()unsafe? - Why can’t you just rely on variables going out of scope to clear secrets?

- What is a timing attack, and how can

memcmp()leak key information? - Why should you use constant-time comparison for MACs/keys?

- What is the danger of leaving keys in heap memory after

free()?

Book Reference:

- “The Secure Coding Cookbook for C and C++” by Viega & Messier - Chapter 13

- “Secure Programming HOWTO” by Wheeler (free online) - Chapter 11

Questions to Guide Your Design

These questions will force you to make design decisions and understand tradeoffs:

-

Message Framing: How will the receiver know where one message ends and the next begins? Will you use length-prefixing, delimiters, or fixed-size frames? What happens if a message is larger than your buffer?

-

Key Exchange Initiation: Who initiates the Diffie-Hellman exchange—client or server? Does the server generate (p, g) each time, or use fixed parameters? What are the security implications of each choice?

-

IV Transmission: AES-CBC requires a unique IV for each message. Will you prepend the IV to each ciphertext, or derive it from a counter? How does the receiver know which IV was used?

-

Error Handling: What happens if DH key exchange fails partway through (network error)? Can you resume, or must you start over? How do you detect if the other party is using incorrect parameters?

-

Cryptographic Library Choice: Will you use OpenSSL’s EVP API, libsodium, a minimal AES library, or implement AES from scratch? What are the security/complexity tradeoffs? (Hint: never implement AES yourself for real-world use, but it’s educational)

-

Replay Attack Prevention: Can an attacker record and replay old encrypted messages? Should you include message sequence numbers? How would SSH handle this?

-

Authentication: Your DH exchange is vulnerable to man-in-the-middle attacks (attacker can impersonate both sides). How does real SSH solve this with host key verification? Can you add a simple challenge-response to your protocol?

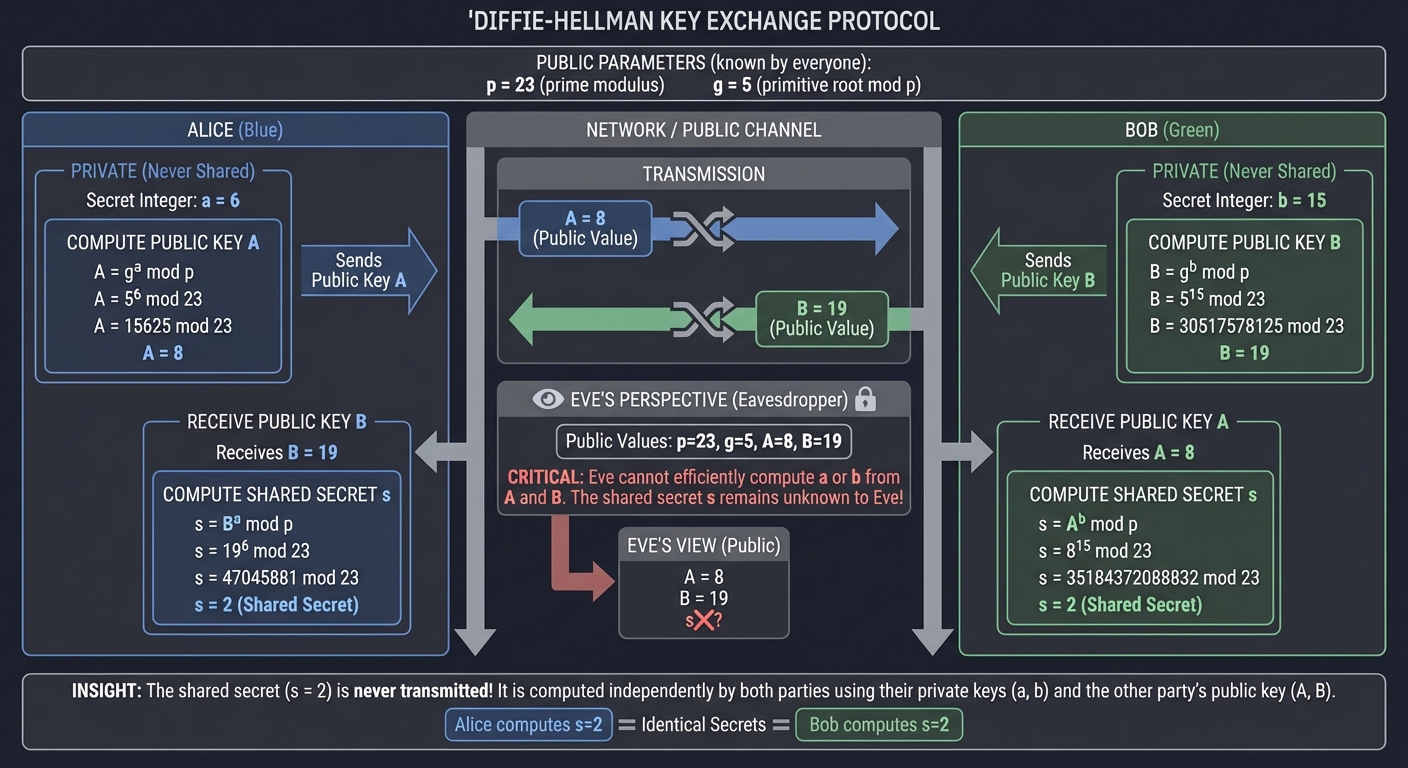

Thinking Exercise: Trace a DH Key Exchange on Paper

Before you write any code, grab paper and pencil and manually trace through a Diffie-Hellman exchange with small numbers:

Given parameters (intentionally small for hand calculation):

- Prime modulus: p = 23

- Generator: g = 5

Step-by-step trace:

- Alice chooses private key: a = 6 (random, secret)

- Alice computes public key: A = 5^6 mod 23 = ?

- Work it out: 5^6 = 15625, 15625 mod 23 = ?

- Bob chooses private key: b = 15 (random, secret)

- Bob computes public key: B = 5^15 mod 23 = ?

- (Hint: use repeated squaring to avoid computing 5^15 directly)

- Public key exchange (over insecure channel):

- Alice sends A to Bob

- Bob sends B to Alice

- Alice computes shared secret:

- s = B^a mod 23 = ?

- Bob computes shared secret:

- s = A^b mod 23 = ?

-

Verify: Did Alice and Bob compute the same s?

- Eavesdropper perspective:

- Eve sees: p = 23, g = 5, A = ?, B = ?

- To find s, Eve must solve: 5^? mod 23 = A (discrete logarithm)

- Try to solve this by brute force with small numbers

- Realize: with p = 2048-bit prime, this is computationally infeasible

Diagram the exchange:

Alice (private: a=6) Network (public) Bob (private: b=15)

| | |

Compute A=g^a mod p | |

| | |

|------------- A ----------->| |

| | Compute B=g^b mod p

| |<---------- B -------------|

| | |

Compute s=B^a mod p | Compute s=A^b mod p

| | |

s = shared secret Eve sees A, B s = shared secret

but cannot compute s!

Key insight from this exercise: The shared secret is never transmitted! It’s computed independently by both parties using their private keys and the other’s public key.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Once you complete this project, you should be able to confidently answer these real interview questions:

Networking Questions

- “Explain the difference between

connect()on the client andaccept()on the server. What exactly does each function do?”- Focus on: connection establishment, three-way handshake, blocking behavior, file descriptor creation

- “You call

send()with 1024 bytes, but it returns 512. What happened, and what should you do?”- Answer: Partial send due to TCP buffer limits. Must track sent bytes and loop with offset.

- “Your server needs to handle multiple clients. Explain three different approaches and their tradeoffs.”

fork()per client (simple, resource-heavy), threads (shared memory issues),select()/poll()/epoll()(complex, scalable)

Cryptography Questions

- “Why can’t you use the same Initialization Vector (IV) twice with the same AES key?”

- Answer: In CBC mode, identical plaintext blocks with same IV produce identical ciphertext, leaking information. Attacker can XOR ciphertexts to learn XOR of plaintexts.

- “Explain how Diffie-Hellman key exchange works. Why can’t an eavesdropper who sees all public values compute the shared secret?”

- Answer: Based on discrete logarithm problem. Given g^a mod p, computing a is hard. Attacker sees A and B but needs a or b to compute secret.

- “What is the difference between static and ephemeral Diffie-Hellman? Which does SSH use and why?”

- Answer: Static DH reuses keys (no forward secrecy). Ephemeral (DHE) generates new keys per session (forward secrecy). SSH uses ephemeral to ensure past sessions stay secure even if current key compromised.

Security Questions

- “Your DH implementation is vulnerable to man-in-the-middle attacks. Explain the attack and how SSH prevents it.”

- Answer: Attacker intercepts DH exchange, performs separate exchanges with both parties. SSH prevents with host key signatures—server signs DH exchange with private host key, client verifies with known public host key.

- “Why is it dangerous to use

memset()to clear sensitive key material in C?”- Answer: Compiler may optimize away memset as “dead store” if buffer isn’t read again. Use

explicit_bzero(),memset_s(), or volatile pointer.

- Answer: Compiler may optimize away memset as “dead store” if buffer isn’t read again. Use

Protocol Design Questions

- “How would you design a message format for encrypted messages that includes length, IV, and ciphertext?”

- Answer: Fixed header with version + length (4 bytes, network order), followed by IV (16 bytes), followed by ciphertext (variable). Discuss why TLV encoding is robust.

- “Your protocol needs to prevent replay attacks. How would you design this?”

- Answer: Include monotonically increasing sequence number in each message (authenticated with MAC). Receiver rejects messages with old/duplicate sequence numbers.

Implementation Questions

- “You’re implementing AES-CBC. Walk me through encrypting a message that’s not a multiple of 16 bytes.”

- Answer: Apply PKCS#7 padding (append bytes, each byte’s value = number of padding bytes). Generate random IV. Encrypt. Prepend IV to ciphertext.

- “Explain the steps your server takes from startup to successfully receiving an encrypted message from a client.”

- Answer: socket() → bind() → listen() → accept() → DH exchange (recv params, send pubkey, recv pubkey, compute secret) → derive AES key → recv encrypted message → decrypt with IV

Hints in Layers

If you get stuck, here are progressive hints from general to specific:

Layer 1: Architecture Hints (Try This First)

- Start with a working echo server/client before adding any encryption

- Build in three phases: (1) plaintext chat, (2) hardcoded AES key, (3) DH key exchange

- Use a message format with a fixed-size header (type + length) followed by variable payload

- Test each component in isolation: AES encrypt/decrypt separate from networking

Layer 2: Networking Hints

- Remember

send()andrecv()may not send/receive the full buffer; always loop until complete - Use

htonl()/ntohl()for length fields to ensure cross-platform compatibility - The server should handle

accept()blocking—this is normal, it waits for clients - For debugging, log every byte sent/received with hexdump-style output:

printf("%02x ", byte)

Layer 3: Cryptography Hints

- Use OpenSSL’s EVP API (EVP_EncryptInit_ex, EVP_EncryptUpdate, EVP_EncryptFinal_ex) rather than low-level AES functions

- Generate random IV with

RAND_bytes(), never hardcode it - For DH, use OpenSSL’s

DH_new(),DH_generate_parameters_ex(),DH_generate_key(), andDH_compute_key() - Don’t implement AES yourself—it’s error-prone and you’ll likely introduce timing vulnerabilities

Layer 4: DH Implementation Hints

- The server should generate (p, g) parameters once at startup, then send them to each client

- Use at least 2048-bit primes for p (DH_generate_parameters_ex with 2048 for key_bits)

- DH exchange flow: Server sends (p, g, server_pubkey) → Client generates keys, sends client_pubkey → Both compute shared secret

- The shared secret is raw bytes; derive an AES key from it using a KDF like HKDF or simple SHA-256 hash

Layer 5: Debugging-Specific Hints

- If messages decrypt to garbage, check: (1) same IV on both sides? (2) same key derived? (3) padding handled correctly?

- Use Wireshark to verify what’s actually on the wire vs. what you think you’re sending

- Add a “protocol handshake” before DH: client sends “HELLO”, server responds “READY”—ensures both are in sync

- Print DH values in hex at each step:

BN_print_fp(stdout, dh_pubkey)to verify math is correct - If

DH_compute_key()returns different values on client/server, you’ve likely swapped who’s using whose public key

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter/Section |

|---|---|---|

| TCP Socket Basics | “TCP/IP Sockets in C, 2nd Edition” by Donahoo & Calvert | Ch. 1-3: Basic client/server, send()/recv() |

| Advanced Socket Programming | “The Linux Programming Interface” by Kerrisk | Ch. 56-61: Sockets, client/server design, I/O multiplexing |

| Socket API Deep Dive | “UNIX Network Programming, Vol. 1” by Stevens | Ch. 4: Elementary TCP sockets, Ch. 6: I/O multiplexing |

| AES and Symmetric Crypto | “Serious Cryptography” by Aumasson | Ch. 4: Block Ciphers, Ch. 5: Block Cipher Modes (CBC, CTR) |

| Practical Crypto Implementation | “Cryptography Engineering” by Ferguson, Schneier, Kohno | Ch. 4: Block Ciphers, Ch. 6: Hash Functions, Ch. 9: SSL/TLS |

| Diffie-Hellman Math | “Serious Cryptography” by Aumasson | Ch. 11: Public-Key Encryption (DH key exchange) |

| DH Mathematical Foundations | “Understanding Cryptography” by Paar & Pelzl | Ch. 10: Key Establishment, discrete logarithm problem |

| Binary Protocol Design | “TCP/IP Illustrated, Volume 1” by Stevens | Ch. 1: Byte order, Ch. 18: TCP connection establishment |

| OpenSSL API Usage | “Network Security with OpenSSL” by Viega, Messier, Chandra | Ch. 3: Symmetric encryption, Ch. 6: Diffie-Hellman |

| Secure C Programming | “The Art of Software Security Assessment” by Dowd, McDonald, Schuh | Ch. 6: C Language Issues, Ch. 8: Strings and Metacharacters |

| Memory Safety for Crypto | “Secure Programming Cookbook for C and C++” by Viega & Messier | Ch. 13: Sensitive data handling, clearing memory |

| SSH Protocol Reference | “SSH, The Secure Shell: The Definitive Guide” by Barrett & Silverman | Ch. 3: SSH protocol internals, key exchange |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Here are the most common problems you’ll encounter and how to fix them:

Problem 1: “My client connects, but recv() blocks forever / returns 0 bytes”

- Why: The server might have crashed, the client/server are out of sync on message framing, or you’re not checking return values properly.

- Fix:

- Always check

recv()return value:< 0= error,== 0= connection closed,> 0= bytes received - Log immediately after

recv():printf("recv() returned %d\n", n); - Use Wireshark to verify the server is actually sending data

- Add a timeout to

recv()usingsetsockopt(SO_RCVTIMEO)for debugging

- Always check

- Quick test:

telnet localhost <port>to manually test if the server accepts connections

Problem 2: “AES decryption produces garbage / random bytes”

- Why: Most likely: (1) different keys on client/server, (2) different IVs, (3) wrong padding mode, or (4) corrupted ciphertext

- Fix:

- Print the AES key in hex on both sides—do they match?

- Print the IV in hex—is client using the same IV server generated?

- Verify you’re using the same cipher mode (CBC, GCM, etc.)

- Check that ciphertext wasn’t truncated in transit (send length first!)

- Ensure you’re calling

EVP_DecryptFinal_ex()which handles padding

- Quick test: Encrypt “Hello” with hardcoded key/IV on both sides, verify it works before adding DH

Problem 3: “Diffie-Hellman: client and server compute different shared secrets”

- Why: You’ve swapped which public key to use, or one side’s DH parameters are different.

- Fix:

- Print all DH values in hex: p, g, client_private, server_private, client_public, server_public

- Verify:

client_public = g^client_private mod p - Verify:

server_public = g^server_private mod p - Client computes:

shared = server_public^client_private mod p - Server computes:

shared = client_public^server_private mod p - These MUST be equal—if not, you’ve mixed up the variables

- Quick test: Use small values (p=23, g=5) and do the math by hand to verify your code logic

Problem 4: “OpenSSL DH_compute_key() crashes / returns -1”

- Why: DH structure not initialized properly, or you’re passing NULL/invalid pointers.

- Fix:

- Check that

DH_generate_parameters_ex()succeeded (returns 1) - Check that

DH_generate_key()succeeded (returns 1) - Verify the peer’s public key is valid:

0 < pubkey < p - Don’t call

DH_free()until after you’ve used the shared secret!

- Check that

- Quick test: Run with

valgrindto catch memory errors

Problem 5: “send() returns fewer bytes than I asked it to send”

- Why: TCP buffers are full. This is normal and expected with large messages.

- Fix:

ssize_t send_all(int sockfd, const void *buf, size_t len) { size_t total_sent = 0; while (total_sent < len) { ssize_t n = send(sockfd, (char*)buf + total_sent, len - total_sent, 0); if (n < 0) return -1; // Error total_sent += n; } return total_sent; } - Quick test: Send a 10MB message and verify it arrives intact

Problem 6: “Wireshark shows my DH public keys but I can’t read them”

- Why: You’re sending binary data without length-prefixing, so the receiver doesn’t know where one field ends and the next begins.

- Fix:

- Send length as 4-byte big-endian int:

uint32_t len_net = htonl(len); send(..., &len_net, 4); - Receiver reads length:

recv(..., &len_net, 4); uint32_t len = ntohl(len_net); - Then receiver reads exactly

lenbytes of data - Use this pattern for every variable-length field

- Send length as 4-byte big-endian int:

- Quick test: Send “ABC” with length prefix, verify receiver gets exactly 3 bytes

Problem 7: “My program crashes with ‘segmentation fault’ during encryption”

- Why: Buffer overflow, use-after-free, or passing wrong buffer sizes to OpenSSL.

- Fix:

- Ensure ciphertext buffer is big enough:

plaintext_len + block_size - Never trust input lengths—validate them first

- Use

valgrind --leak-check=full ./your_programto find the exact line - Check that you’re not freeing EVP contexts twice

- Ensure ciphertext buffer is big enough:

- Quick test: Run under

valgrindwith a simple 16-byte message

Problem 8: “Client and server both print ‘shared secret computed’ but messages still decrypt to garbage”

- Why: You computed the same shared secret but derived different AES keys from it.

- Fix:

- Both sides must use the exact same key derivation function

- If using SHA-256: both hash the exact same bytes (watch out for endianness!)

- Print the derived AES key in hex on both sides—must match

- Don’t include extra data (like newlines) when hashing

- Quick test: Hardcode a shared secret and verify key derivation works before using DH

Problem 9: “Connection works once, but second client connection hangs”

- Why: Server isn’t properly handling multiple connections—likely blocking on first client.

- Fix:

- Server should

fork()afteraccept()so each client gets its own process - Or use

select()/poll()for single-threaded multiplexing - Parent process should continue

accept()loop immediately - Install SIGCHLD handler to

waitpid()for zombie processes

- Server should

- Quick test: Connect with two clients simultaneously—both should work

Problem 10: “Everything works on localhost but fails on different machines”

- Why: Firewall blocking, wrong network interface, or endianness issues.

- Fix:

- Verify firewall allows port:

sudo ufw allow 8888/tcp(Linux) - Server should

bind()toINADDR_ANY(0.0.0.0) notlocalhost - Double-check all

htonl()/ntohl()calls for integers sent over network - Test with

nc -zv <server_ip> <port>to verify port is open

- Verify firewall allows port:

- Quick test:

telnet <server_ip> <port>from client machine to verify connectivity

Project 2: SSH Protocol Dissector

- File: SSH_DEEP_DIVE_LEARNING_PROJECTS.md

- Programming Language: C

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 3. The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Network Protocols / Packet Analysis

- Software or Tool: libpcap / Wireshark

- Main Book: “Practical Packet Analysis” by Chris Sanders

What you’ll build: A tool that captures and decodes SSH protocol packets in real-time, showing you the handshake, key exchange, authentication, and channel operations as they happen.

Why it teaches SSH: By parsing real SSH traffic, you’ll internalize the actual protocol structure. You’ll see the version exchange, algorithm negotiation, key exchange messages, and encrypted payload boundaries. This is “learning by observation.”

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Capturing network packets (libpcap) (maps to understanding network layers)

- Parsing SSH binary packet format (maps to protocol internals)

- Decoding SSH message types and their fields (maps to RFC 4253 understanding)

- Displaying human-readable output of the handshake sequence

Resources for key challenges:

- RFC 4253 (SSH Transport Layer Protocol) - The authoritative specification

- “Practical Packet Analysis” by Chris Sanders - How to think about packet capture

Key Concepts:

- Packet Capture: “The Practice of Network Security Monitoring” by Bejtlich - Ch. 6

- SSH Protocol Structure: RFC 4253 - Sections 4-8

- Binary Parsing in C: “Fluent C” by Preschern - Ch. 8 (Data Structures)

- Network Byte Order: “TCP/IP Illustrated, Volume 1” by Stevens - Ch. 1

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 1-2 weeks Prerequisites: Basic networking knowledge, C programming

Real world outcome:

- Run your dissector while SSH’ing to a server

- See output like:

[HANDSHAKE] Client Version: SSH-2.0-OpenSSH_9.0 [HANDSHAKE] Server Version: SSH-2.0-OpenSSH_8.9 [KEX_INIT] Client algorithms: curve25519-sha256,aes256-gcm... [KEX_INIT] Server algorithms: curve25519-sha256,aes256-ctr... [ECDH_INIT] Client public key: 0x3a8f2b... [ECDH_REPLY] Server public key: 0x7c4e1d... [NEWKEYS] Encryption activated [ENCRYPTED] 156 bytes (cannot decode without keys)

Learning milestones:

- Capture SSH packets → You understand where SSH sits in the network stack

- Parse unencrypted handshake → You understand SSH negotiation

- Identify encrypted boundaries → You understand when/why encryption starts

Real World Outcome

When you run your SSH Protocol Dissector, you’ll see the complete anatomy of an SSH connection. Here’s what a real capture session looks like with detailed explanations:

$ sudo ./ssh_dissector eth0

Listening on eth0... Press Ctrl+C to stop

[PACKET #1 - TCP HANDSHAKE]

Source: 192.168.1.100:52341 → Destination: 192.168.1.50:22

TCP Flags: SYN

Seq: 1234567890

[PACKET #2 - TCP HANDSHAKE]

Source: 192.168.1.50:22 → Destination: 192.168.1.100:52341

TCP Flags: SYN, ACK

Seq: 9876543210, Ack: 1234567891

[PACKET #3 - TCP HANDSHAKE]

Source: 192.168.1.100:52341 → Destination: 192.168.1.50:22

TCP Flags: ACK

Ack: 9876543211

[PACKET #4 - SSH VERSION EXCHANGE]

Source: 192.168.1.50:22 → Destination: 192.168.1.100:52341

SSH Version String: "SSH-2.0-OpenSSH_9.3p1 Ubuntu-1ubuntu3\r\n"

Protocol Version: 2.0

Software: OpenSSH_9.3p1

Comments: Ubuntu-1ubuntu3

Length: 40 bytes

[PACKET #5 - SSH VERSION EXCHANGE]

Source: 192.168.1.100:52341 → Destination: 192.168.1.50:22

SSH Version String: "SSH-2.0-OpenSSH_8.9\r\n"

Protocol Version: 2.0

Software: OpenSSH_8.9

Length: 21 bytes

[PACKET #6 - SSH_MSG_KEXINIT (Client)]

Source: 192.168.1.100:52341 → Destination: 192.168.1.50:22

Message Type: SSH_MSG_KEXINIT (20)

Packet Length: 1068 bytes

Padding Length: 6 bytes

Cookie: 16 random bytes: [0x3a, 0x8f, 0x2b, 0x9c, ...]

Key Exchange Algorithms:

- curve25519-sha256

- curve25519-sha256@libssh.org

- ecdh-sha2-nistp256

- ecdh-sha2-nistp384

- diffie-hellman-group14-sha256

Encryption Algorithms (client-to-server):

- aes256-gcm@openssh.com

- chacha20-poly1305@openssh.com

- aes256-ctr

- aes192-ctr

- aes128-ctr

Encryption Algorithms (server-to-client):

- aes256-gcm@openssh.com

- chacha20-poly1305@openssh.com

- aes256-ctr

MAC Algorithms (client-to-server):

- umac-128-etm@openssh.com

- hmac-sha2-256-etm@openssh.com

- hmac-sha2-512-etm@openssh.com

MAC Algorithms (server-to-client):

- umac-128-etm@openssh.com

- hmac-sha2-256-etm@openssh.com

Compression Algorithms:

- none

- zlib@openssh.com

[PACKET #7 - SSH_MSG_KEXINIT (Server)]

Source: 192.168.1.50:22 → Destination: 192.168.1.100:52341

Message Type: SSH_MSG_KEXINIT (20)

[Similar structure to client, showing server's preferred algorithms]

[PACKET #8 - SSH_MSG_KEXECDH_INIT]

Source: 192.168.1.100:52341 → Destination: 192.168.1.50:22

Message Type: SSH_MSG_KEXECDH_INIT (30)

Client Ephemeral Public Key (Curve25519):

Length: 32 bytes

Value: 0x3a8f2b9c4d5e6f7a8b9c0d1e2f3a4b5c6d7e8f9a0b1c2d3e4f5a6b7c8d9e0f1a

[PACKET #9 - SSH_MSG_KEXECDH_REPLY]

Source: 192.168.1.50:22 → Destination: 192.168.1.100:52341

Message Type: SSH_MSG_KEXECDH_REPLY (31)

Server Host Key (ssh-ed25519):

Algorithm: ssh-ed25519

Key Length: 51 bytes

Public Key: 0x7c4e1d2a3b4c5d6e7f8a9b0c1d2e3f4a5b6c7d8e9f0a1b2c3d4e5f6a7b8c9d0e

Server Ephemeral Public Key (Curve25519):

Length: 32 bytes

Value: 0x7c4e1d2a3b4c5d6e7f8a9b0c1d2e3f4a5b6c7d8e9f0a1b2c3d4e5f6a7b8c9d0e

Exchange Hash Signature:

Algorithm: ssh-ed25519

Signature Length: 83 bytes

[PACKET #10 - SSH_MSG_NEWKEYS (Client)]

Source: 192.168.1.100:52341 → Destination: 192.168.1.50:22

Message Type: SSH_MSG_NEWKEYS (21)

Packet Length: 12 bytes

--- Key Exchange Complete: Encryption Activated ---

[PACKET #11 - SSH_MSG_NEWKEYS (Server)]

Source: 192.168.1.50:22 → Destination: 192.168.1.100:52341

Message Type: SSH_MSG_NEWKEYS (21)

--- All subsequent packets will be encrypted ---

[PACKET #12 - ENCRYPTED DATA]

Source: 192.168.1.100:52341 → Destination: 192.168.1.50:22

Encrypted Packet Length: 156 bytes

MAC: hmac-sha2-256 (32 bytes)

⚠️ Cannot decode payload (requires session keys)

Likely contains: SSH_MSG_SERVICE_REQUEST (authentication request)

[PACKET #13 - ENCRYPTED DATA]

Source: 192.168.1.50:22 → Destination: 192.168.1.100:52341

Encrypted Packet Length: 92 bytes

MAC: hmac-sha2-256 (32 bytes)

⚠️ Cannot decode payload

Likely contains: SSH_MSG_SERVICE_ACCEPT (authentication accepted)

Field Explanations:

- Packet Length: First 4 bytes of each SSH packet (after version exchange), indicates total packet size excluding MAC

- Padding Length: 1 byte indicating how many padding bytes are at the end (SSH requires 4-255 bytes of padding)

- Message Type: 1 byte identifier (20 = KEXINIT, 30 = KEXECDH_INIT, 31 = KEXECDH_REPLY, 21 = NEWKEYS)

- Cookie: 16 random bytes in KEXINIT to prevent replay attacks and add randomness

- Algorithm Lists: Null-terminated, comma-separated lists of supported algorithms in preference order

- MAC (Message Authentication Code): Appended after encryption, computed over sequence number + unencrypted packet

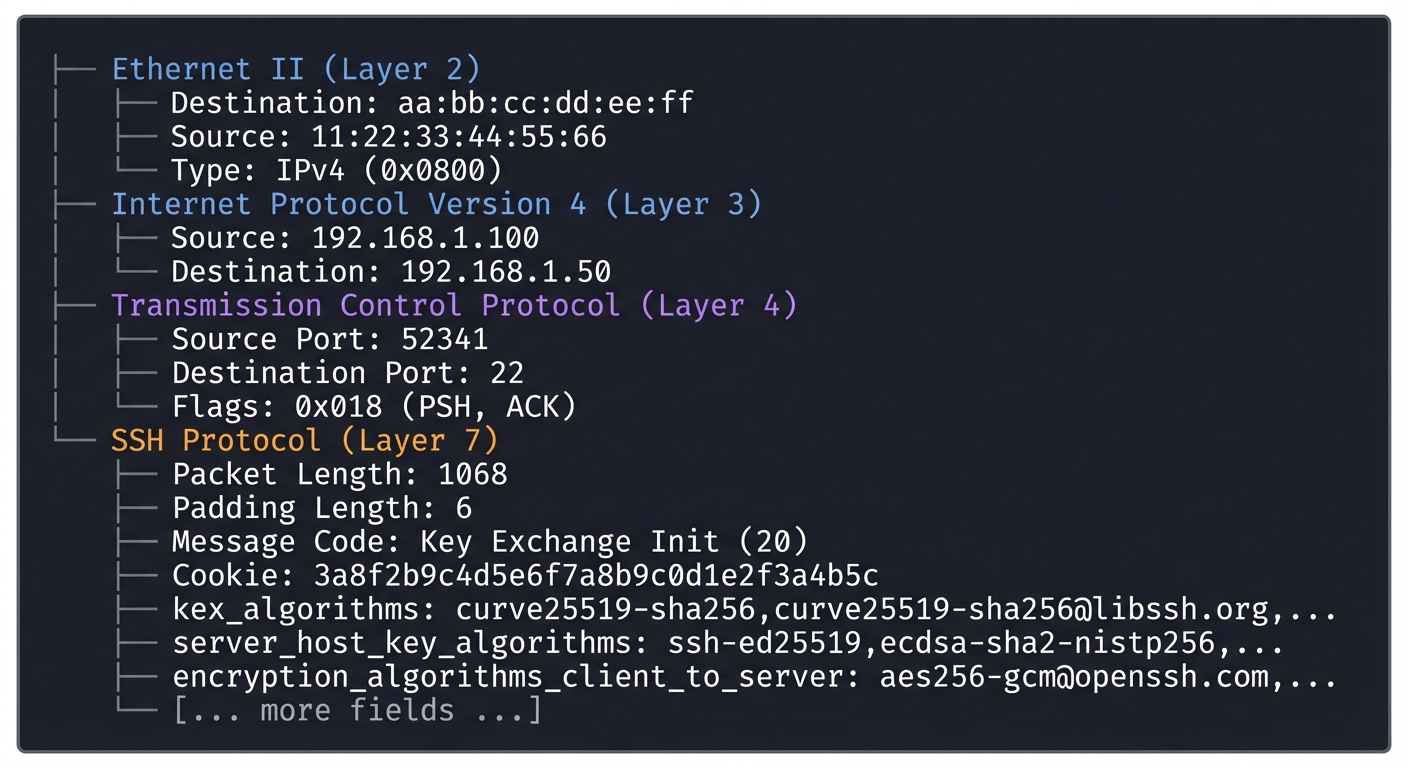

Comparison with Wireshark:

Your dissector should show similar information to Wireshark’s built-in SSH dissector:

Wireshark Display:

├── Ethernet II

│ ├── Destination: aa:bb:cc:dd:ee:ff

│ ├── Source: 11:22:33:44:55:66

│ └── Type: IPv4 (0x0800)

├── Internet Protocol Version 4

│ ├── Source: 192.168.1.100

│ └── Destination: 192.168.1.50

├── Transmission Control Protocol

│ ├── Source Port: 52341

│ ├── Destination Port: 22

│ └── Flags: 0x018 (PSH, ACK)

└── SSH Protocol

├── Packet Length: 1068

├── Padding Length: 6

├── Message Code: Key Exchange Init (20)

├── Cookie: 3a8f2b9c4d5e6f7a8b9c0d1e2f3a4b5c

├── kex_algorithms: curve25519-sha256,curve25519-sha256@libssh.org,...

├── server_host_key_algorithms: ssh-ed25519,ecdsa-sha2-nistp256,...

├── encryption_algorithms_client_to_server: aes256-gcm@openssh.com,...

└── [... more fields ...]

Capturing a Real SSH Session:

- Terminal 1 (run your dissector):

sudo ./ssh_dissector -i eth0 -f "tcp port 22" - Terminal 2 (initiate SSH connection):

ssh user@192.168.1.50 - What you’ll observe:

- First 3 packets: TCP three-way handshake (SYN, SYN-ACK, ACK)

- Packets 4-5: Version exchange (plaintext, human-readable)

- Packets 6-7: KEXINIT messages (plaintext, shows algorithm lists)

- Packets 8-9: Key exchange messages (ECDH_INIT, ECDH_REPLY with public keys)

- Packets 10-11: NEWKEYS messages (signals encryption activation)

- Packet 12+: All encrypted (you can only see packet boundaries and MACs)

- Compare with tcpdump:

sudo tcpdump -i eth0 'tcp port 22' -w ssh_capture.pcap # Then open in Wireshark to see the same dissection

The Core Question You’re Answering

“What actually happens on the wire when I type ‘ssh user@server’?”