Retro Game Emulation: Learn by Building

Goal: Deeply understand how computers work at the hardware level by building emulators—software that recreates the behavior of classic gaming hardware. You’ll learn CPU architectures, memory systems, graphics rendering, audio synthesis, and timing-critical systems programming. By the end of this journey, you’ll understand how a Game Boy cartridge becomes pixels on screen, how a 6502 CPU executes machine code, and how hardware limitations shaped the games we love.

Why Emulation Matters

Emulation sits at the intersection of computer architecture, systems programming, and reverse engineering. Learning emulation gives you:

Real-World Technical Skills:

- CPU Architecture Understanding: You’ll implement instruction sets from scratch, giving you a mental model of how CPUs actually work—knowledge that applies to debugging production systems, performance optimization, and understanding compiler output.

- Memory Management Expertise: Emulating memory controllers, bank switching, and DMA teaches you how operating systems and hardware manage memory at the lowest level.

- Timing-Critical Programming: Games relied on precise timing to work correctly. You’ll learn to think in clock cycles, understand race conditions, and appreciate the importance of deterministic execution.

- Bit Manipulation Mastery: Emulation involves constant bit-twiddling—decoding opcodes, manipulating flags, encoding graphics data. You’ll become fluent in bitwise operations.

Career Applications:

- Embedded Systems: Understanding how constrained hardware operates is directly applicable to IoT, robotics, and automotive systems.

- Game Engine Development: The techniques for managing state, rendering graphics, and synchronizing audio apply directly to modern game engines.

- Compiler/VM Development: Emulating a CPU is structurally similar to building a bytecode interpreter or JIT compiler.

- Hardware Verification: Test ROM development and cycle-accurate emulation mirror techniques used in chip verification.

- Reverse Engineering: ROM hacking and understanding undocumented opcodes are fundamental reverse engineering skills.

Intellectual Satisfaction:

- Emulation is tangible—you see your code translate opcodes into running games. There’s immediate feedback.

- It’s historically rich—you’ll understand the clever engineering that made 1980s/90s games possible.

- It’s complete—building a full emulator exercises every part of your programming brain: algorithms, systems programming, debugging, optimization.

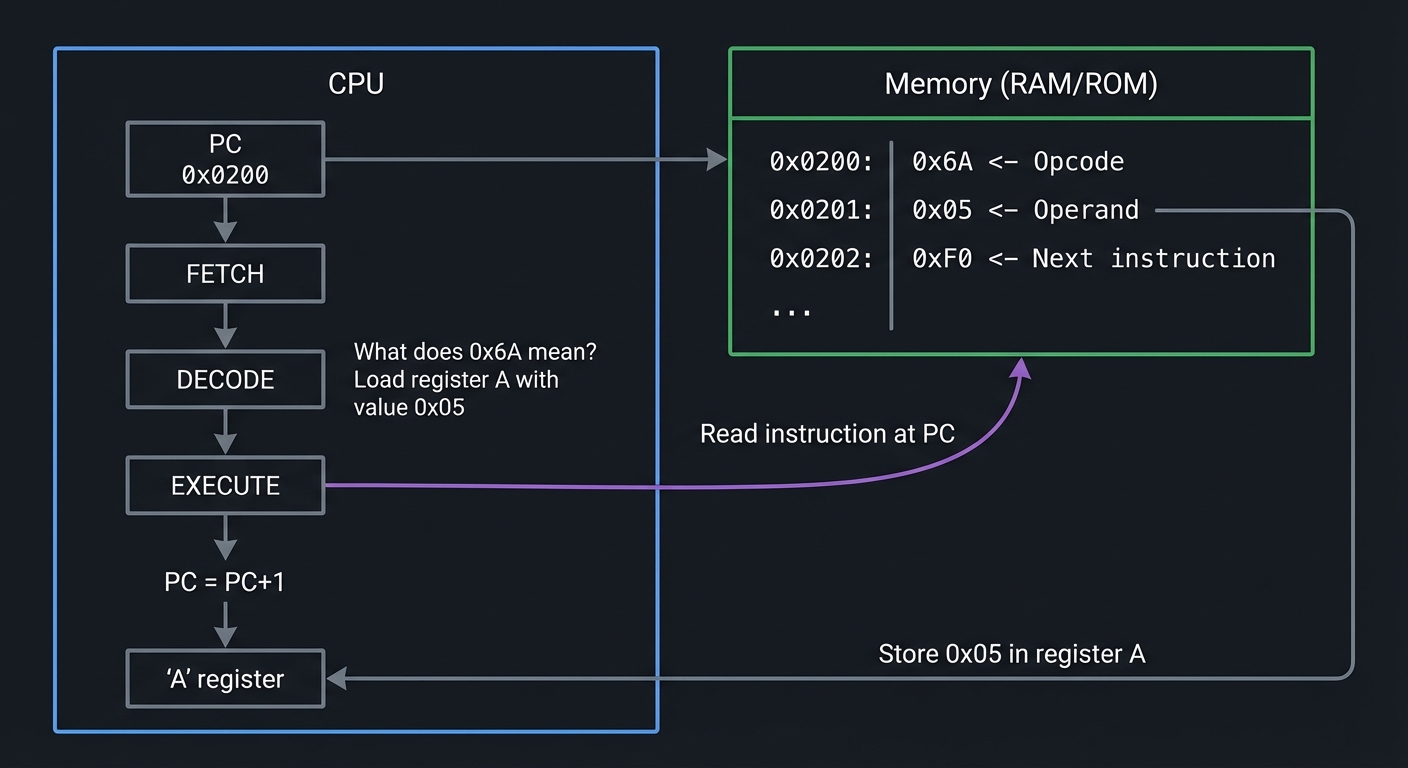

The Fetch-Decode-Execute Cycle

At the heart of every CPU—and every emulator—is the fetch-decode-execute cycle. This is the fundamental loop that turns bytes in memory into running programs.

How CPUs Work: A Mental Model

Think of a CPU as a clerk in an office with three tasks:

- Fetch: The clerk looks at a to-do list (program counter) to find the next instruction.

- Decode: The clerk reads the instruction and figures out what it means.

- Execute: The clerk performs the action and updates the to-do list to point to the next instruction.

This repeats millions of times per second, creating the illusion of a “running program.”

The Cycle in Detail

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ FETCH-DECODE-EXECUTE CYCLE │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

┌──────────┐

│ CPU │

│ │

│ ┌────┐ │ ┌─────────────────────────────────────┐

│ │ PC │──┼──────>│ Memory (RAM/ROM) │

│ └────┘ │ │ │

│ │ │ │ 0x0200: 0x6A <- Opcode │

│ v │ │ 0x0201: 0x05 <- Operand │

│ FETCH │ │ 0x0202: 0xF0 <- Next instruction │

│ │ │ │ ... │

│ v │ └─────────────────────────────────────┘

│ DECODE │ ^

│ │ │ │

│ v │ │ Read instruction at PC

│ EXECUTE │──────────────┘

│ │ │

│ v │ What does 0x6A mean?

│ PC = PC+1│ "Load register A with value 0x05"

│ │

│ ┌────┐ │

│ │ A │<─┼───── Store 0x05 in register A

│ └────┘ │

└──────────┘

Example: CHIP-8 Instruction Execution

Let’s trace one instruction through the cycle:

Memory at 0x200:

0x200: 0x6A 0x05 (Instruction: "LD V[A], 0x05" - Load register V[10] with value 5)

Fetch:

uint16_t opcode = (memory[PC] << 8) | memory[PC + 1]; // opcode = 0x6A05

PC += 2; // Move program counter to next instruction

Decode:

uint8_t instruction_type = (opcode & 0xF000) >> 12; // 0x6 = "LD Vx, byte"

uint8_t x = (opcode & 0x0F00) >> 8; // 0xA = register index

uint8_t value = opcode & 0x00FF; // 0x05 = value to load

Execute:

V[x] = value; // V[10] = 5

Why This Matters for Emulation

When you build an emulator, you are implementing this cycle in software. Your emulator’s main loop looks like this:

while (running) {

uint16_t opcode = fetch(cpu); // Read from emulated memory

Instruction instr = decode(opcode); // Figure out what it means

execute(cpu, instr); // Perform the operation

update_timers(cpu); // Advance system state

if (should_render_frame(cpu)) {

render_screen(); // Draw to screen

}

}

Every emulator—from CHIP-8 to PlayStation—follows this pattern. The complexity varies (Game Boy has 500+ opcodes, PS1 has coprocessors), but the fundamental structure is the same.

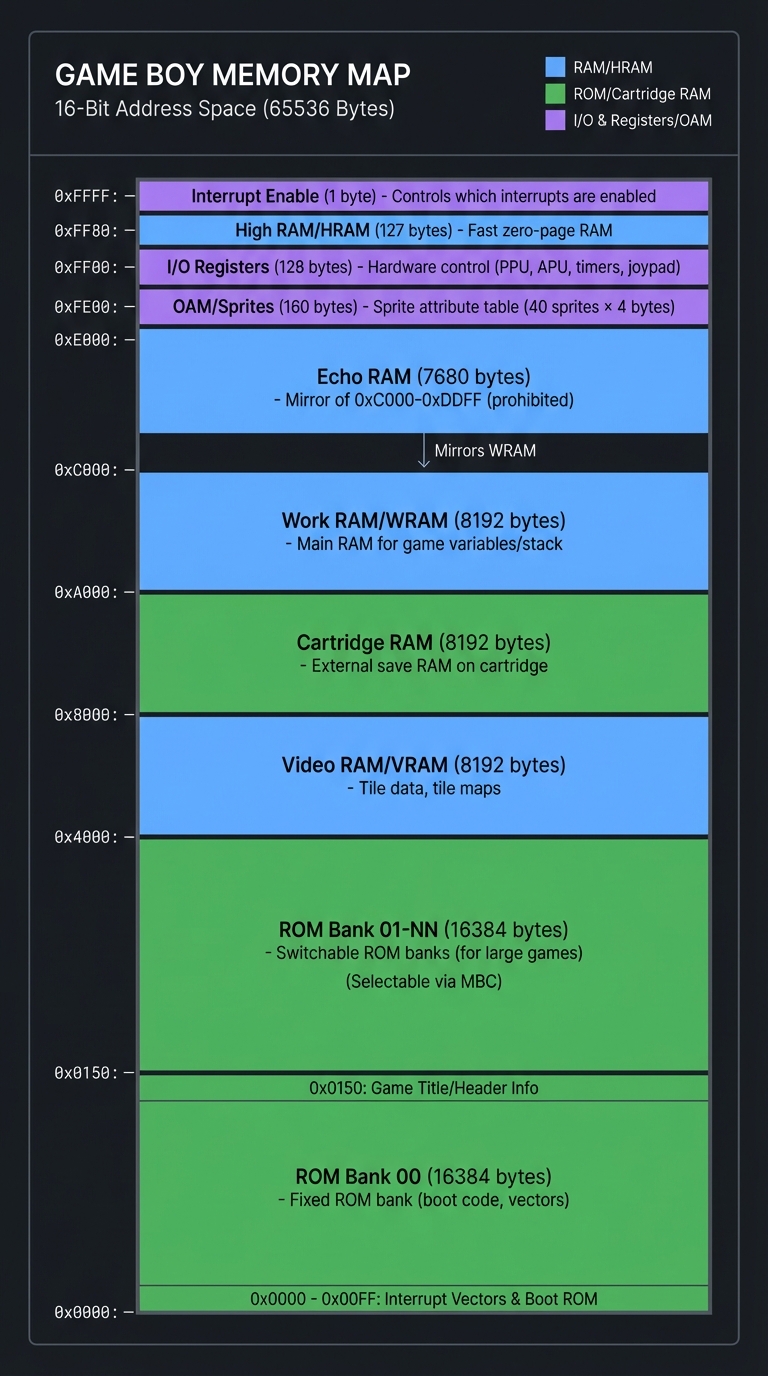

Memory Architecture in Emulation

Memory is not just “a big array.” In retro systems, memory was carefully partitioned, often with special-purpose regions and hardware tricks to overcome addressing limitations.

Memory Maps: Where Everything Lives

A memory map describes what lives at each address range. Here’s the Game Boy’s memory map:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ GAME BOY MEMORY MAP │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

0xFFFF ┌──────────────────┐

│ Interrupt Enable│ (1 byte) - Controls which interrupts are enabled

├──────────────────┤

0xFF80 │ High RAM (HRAM) │ (127 bytes) - Fast zero-page RAM

├──────────────────┤

0xFF00 │ I/O Registers │ (128 bytes) - Hardware control (PPU, APU, timers, joypad)

├──────────────────┤

0xFE00 │ OAM (Sprites) │ (160 bytes) - Sprite attribute table (40 sprites × 4 bytes)

├──────────────────┤

0xE000 │ Echo RAM │ (7680 bytes) - Mirror of 0xC000-0xDDFF (prohibited)

├──────────────────┤

0xC000 │ Work RAM (WRAM) │ (8192 bytes) - Main RAM for game variables/stack

├──────────────────┤

0xA000 │ Cartridge RAM │ (8192 bytes) - External save RAM on cartridge

├──────────────────┤

0x8000 │ Video RAM (VRAM)│ (8192 bytes) - Tile data, tile maps

├──────────────────┤

0x4000 │ ROM Bank 01-NN │ (16384 bytes) - Switchable ROM banks (for large games)

├──────────────────┤

0x0000 │ ROM Bank 00 │ (16384 bytes) - Fixed ROM bank (boot code, vectors)

└──────────────────┘

When the CPU reads from 0xFF00, it's not reading RAM—it's reading

the joypad register. When it writes to 0x8000, it's modifying tile

graphics, not general memory. This is called MEMORY-MAPPED I/O.

Memory-Mapped I/O

In retro systems, hardware registers appear as memory addresses. Writing to these addresses controls hardware:

// Reading joypad state on Game Boy

uint8_t joypad_state = memory[0xFF00]; // This reads a hardware register!

// Writing to PPU control register

memory[0xFF40] = 0x91; // Enable LCD, background, sprites - controls hardware!

// Loading a tile into VRAM

memory[0x8000] = 0xFF; // This writes to video memory, changing graphics

This is why emulators implement memory as functions, not arrays:

uint8_t read_byte(uint16_t address) {

if (address < 0x8000) {

return rom[address]; // Reading ROM

} else if (address >= 0xFF00 && address <= 0xFF7F) {

return read_io_register(address); // Reading hardware

} else if (address >= 0x8000 && address < 0xA000) {

return vram[address - 0x8000]; // Reading video RAM

}

// ... and so on for every memory region

}

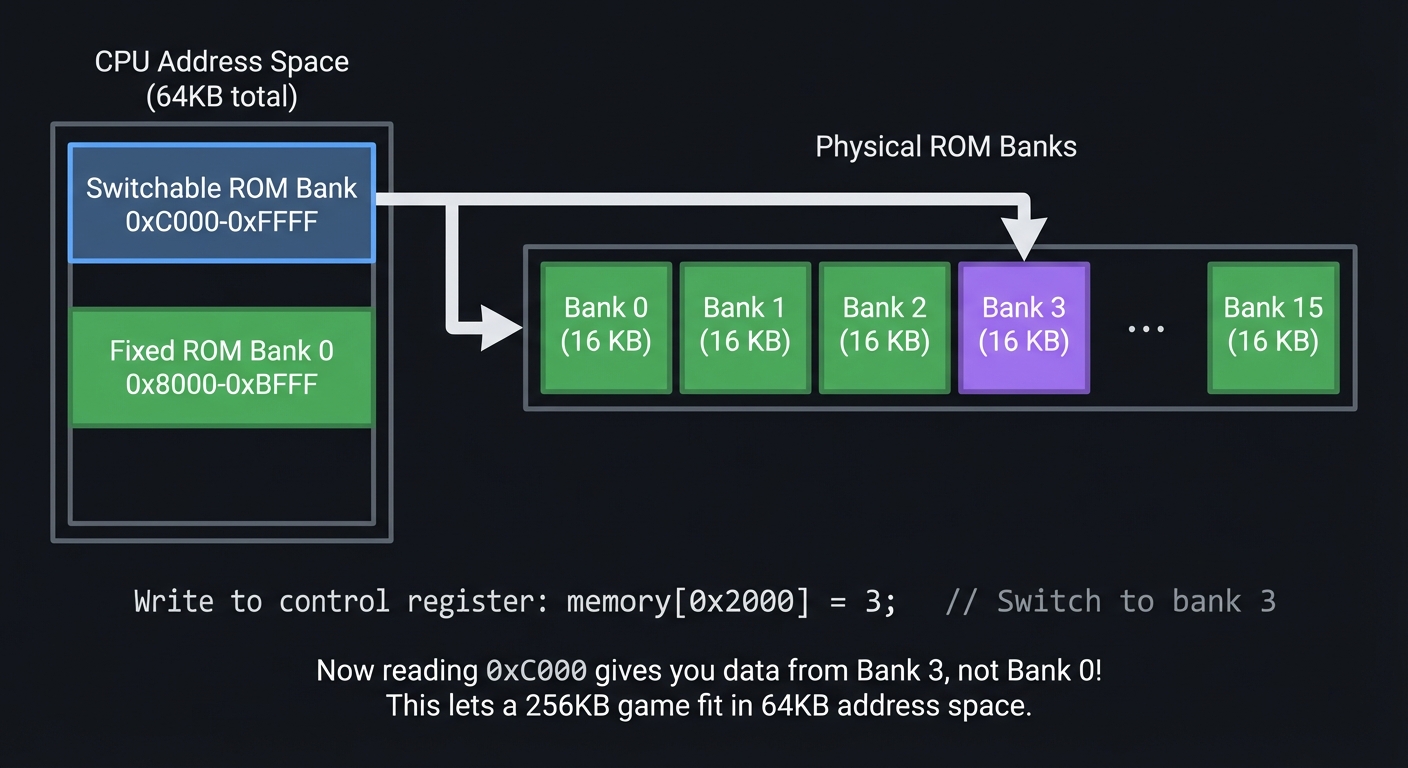

Bank Switching: Overcoming Address Space Limits

Early CPUs had limited addressing (8-bit or 16-bit), meaning they could only address 64KB. But games grew larger than 64KB. The solution? Bank switching—hardware that swaps which ROM/RAM is visible at a given address.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ BANK SWITCHING EXAMPLE │

│ (NES Mapper / GB MBC Cartridge) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

CPU Address Space (64KB total):

┌─────────────────┐

│ 0xC000-0xFFFF │ ──┐

│ Switchable │ │ ┌──────────────────────────────────┐

│ ROM Bank │ └─>│ Bank 0 │ Bank 1 │ Bank 2 │ ... │ Bank 15 │

├─────────────────┤ │ 16 KB │ 16 KB │ 16 KB │ │ 16 KB │

│ 0x8000-0xBFFF │ └──────────────────────────────────┘

│ Fixed │ ^

│ ROM Bank 0 │ │

└─────────────────┘ │

│

Write to control register:

memory[0x2000] = 3; // Switch to bank 3

Now reading 0xC000 gives you data from Bank 3, not Bank 0!

This lets a 256KB game fit in 64KB address space.

Your emulator must track which bank is active:

uint8_t current_rom_bank = 1; // Track active bank

void write_byte(uint16_t address, uint8_t value) {

if (address >= 0x2000 && address < 0x4000) {

// Writing to bank controller

current_rom_bank = value & 0x1F; // Switch banks

}

}

uint8_t read_byte(uint16_t address) {

if (address >= 0x4000 && address < 0x8000) {

// Reading from switchable bank

uint32_t rom_address = (current_rom_bank * 0x4000) + (address - 0x4000);

return rom[rom_address];

}

}

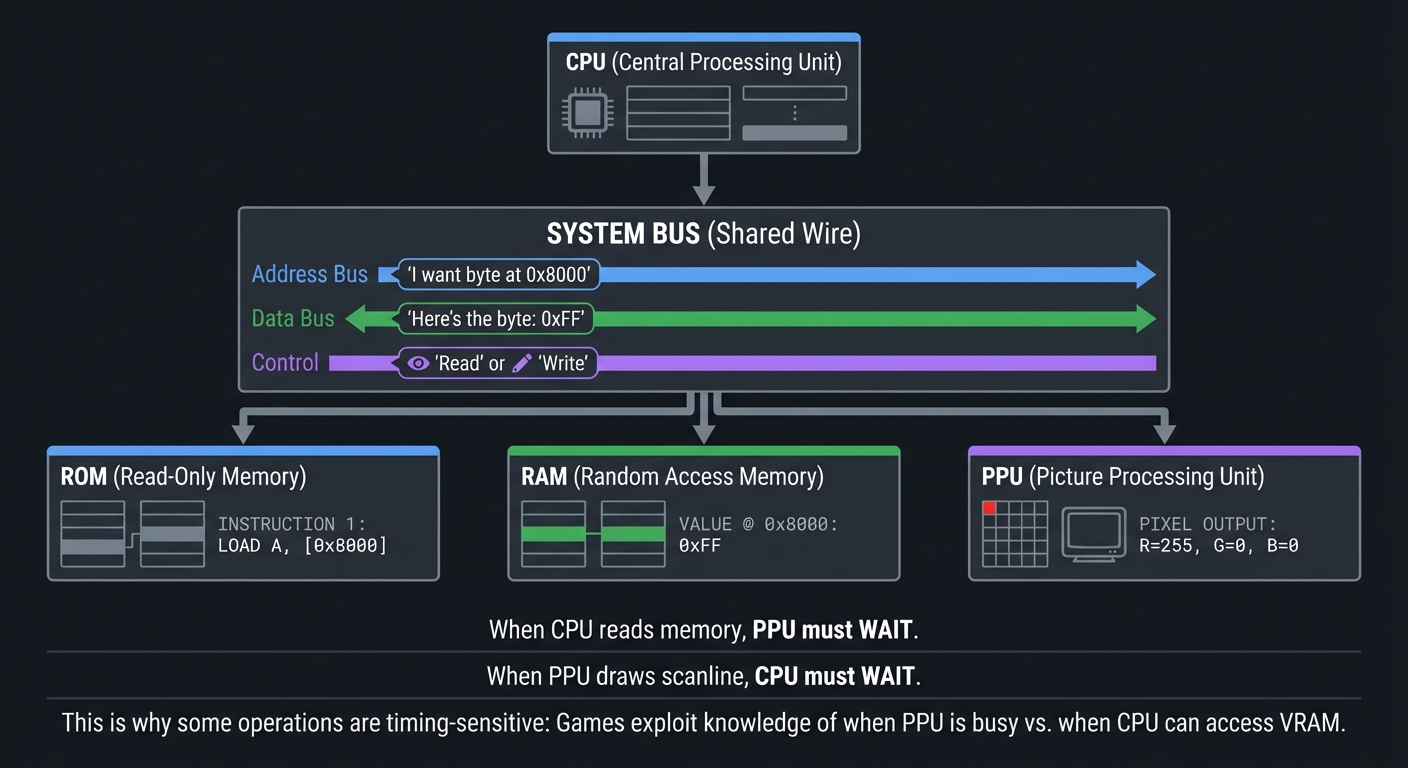

Bus Architecture: Shared Highway

The bus is the shared pathway connecting CPU, memory, and peripherals. Only one component can use it at a time.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ BUS ARCHITECTURE │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

┌─────────┐

│ CPU │

└────┬────┘

│

v

┌────────────────┐ (Address Bus: "I want byte at 0x8000")

│ SYSTEM BUS │ (Data Bus: "Here's the byte: 0xFF")

│ (Shared Wire) │ (Control: "Read" or "Write")

└────────────────┘

│ │ │

v v v

┌───┐ ┌───┐ ┌────┐

│ROM│ │RAM│ │PPU │

└───┘ └───┘ └────┘

When CPU reads memory, PPU must WAIT.

When PPU draws scanline, CPU must WAIT.

This is why some operations are timing-sensitive:

Games exploit knowledge of when PPU is busy vs. when CPU can access VRAM.

Graphics/PPU Fundamentals

Retro graphics weren’t drawn pixel-by-pixel. They used tile-based rendering—a memory-efficient system that made games possible on limited hardware.

Tile-Based Graphics: Building Blocks

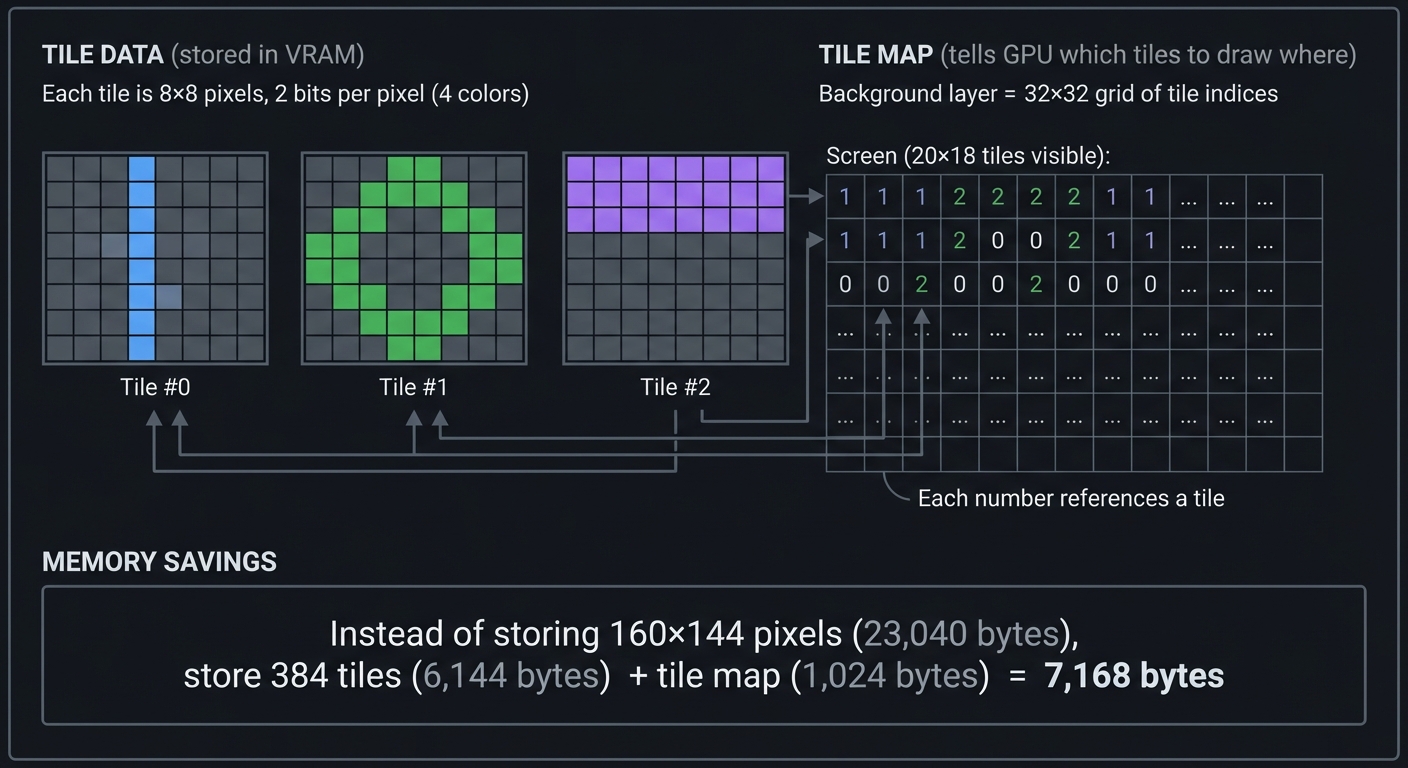

Instead of storing every pixel, games stored 8×8 tiles and assembled them into screens.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ TILE-BASED RENDERING │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

TILE DATA (stored in VRAM):

Each tile is 8×8 pixels, 2 bits per pixel (4 colors)

Tile #0: Tile #1: Tile #2:

┌────────┐ ┌────────┐ ┌────────┐

│........│ │..████..│ │████████│

│..██....│ │.██..██.│ │██....██│

│..██....│ │██....██│ │██....██│

│..██....│ │██....██│ │██....██│

│..██....│ │.██..██.│ │████████│

│..██....│ │..████..│ │........│

│..██....│ │........│ │........│

│........│ │........│ │........│

└────────┘ └────────┘ └────────┘

TILE MAP (tells GPU which tiles to draw where):

Background layer = 32×32 grid of tile indices

Screen (20×18 tiles visible):

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│ 1 1 2 2 2 2 1 1 ... │ <- Each number references a tile

│ 1 1 2 0 0 2 1 1 ... │

│ 0 0 2 0 0 2 0 0 ... │

│ ... ... ... ... ... ... │

└─────────────────────────────┘

Instead of storing 160×144 pixels (23,040 bytes),

store 384 tiles (6,144 bytes) + tile map (1,024 bytes) = 7,168 bytes

Your emulator must render tiles to a framebuffer:

void render_scanline(int line) {

for (int x = 0; x < 160; x++) {

// Which tile are we in?

int tile_x = (x + scroll_x) / 8;

int tile_y = (line + scroll_y) / 8;

// Which pixel within the tile?

int pixel_x = (x + scroll_x) % 8;

int pixel_y = (line + scroll_y) % 8;

// Look up tile index from tile map

uint8_t tile_index = tile_map[tile_y * 32 + tile_x];

// Get pixel color from tile data

uint8_t color = get_tile_pixel(tile_index, pixel_x, pixel_y);

// Draw to framebuffer

framebuffer[line * 160 + x] = palette[color];

}

}

Scanline Rendering: Drawing Line by Line

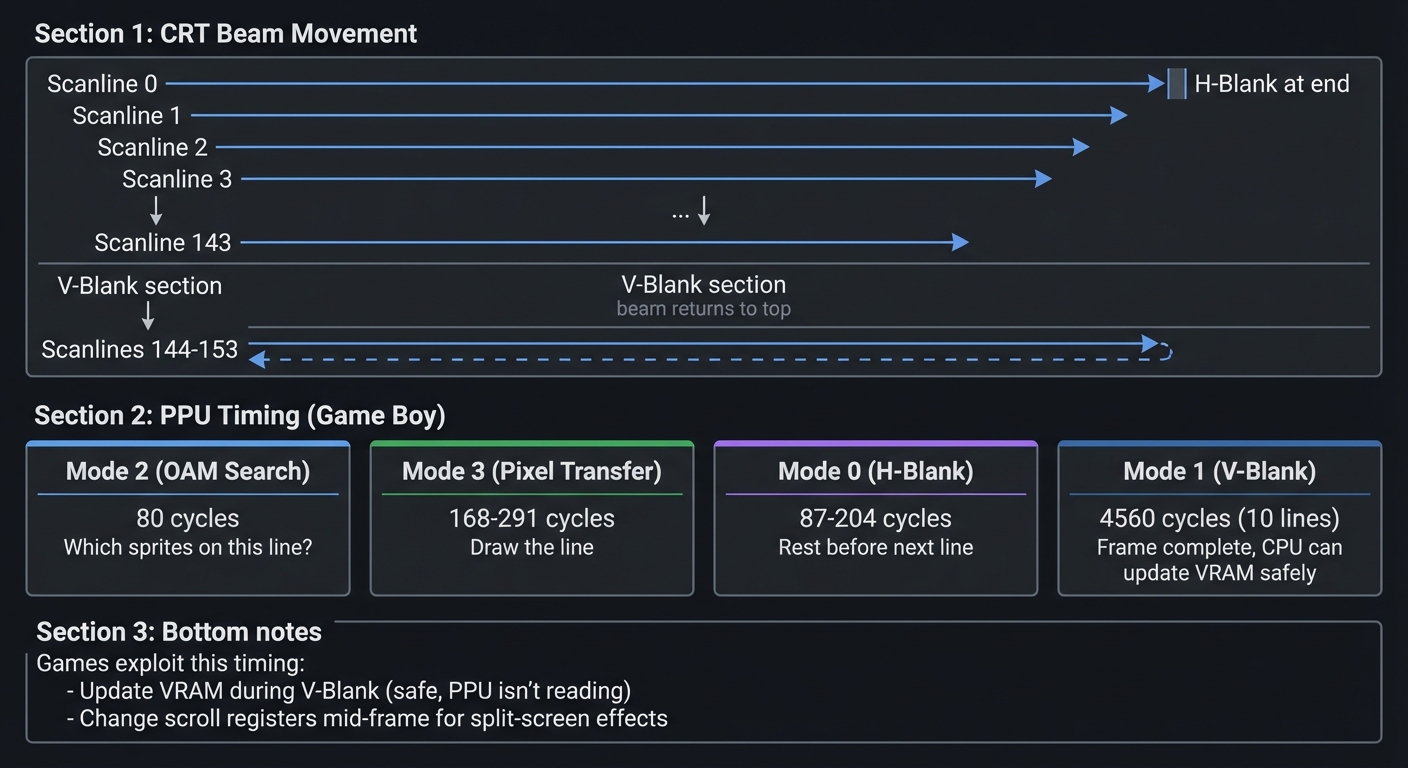

Old CRT TVs drew the screen line-by-line using an electron beam. Emulators simulate this:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ SCANLINE RENDERING │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

CRT Beam Movement:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ >─────────────────────────────────────> │ Scanline 0 (H-Blank at end)

│ >───────────────────────────────────> │ Scanline 1

│ >─────────────────────────────────> │ Scanline 2

│ >───────────────────────────────> │ Scanline 3

│ ... │

│ │

│ >─────────────────────────────────────> │ Scanline 143

├─────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ (V-Blank - beam returns to top) │ Scanlines 144-153

└─────────────────────────────────────────┘

PPU Timing (Game Boy):

- Mode 2 (OAM Search): 80 cycles - "Which sprites on this line?"

- Mode 3 (Pixel Transfer): 168-291 cycles - "Draw the line"

- Mode 0 (H-Blank): 87-204 cycles - "Rest before next line"

- Mode 1 (V-Blank): 4560 cycles (10 lines) - "Frame complete, CPU can update VRAM safely"

Games exploit this timing:

- Update VRAM during V-Blank (safe, PPU isn't reading)

- Change scroll registers mid-frame for split-screen effects

Sprites vs Background

Two layers: background (scrolling world) and sprites (moving objects).

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ SPRITES VS BACKGROUND │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Background Layer (32×32 tiles, scrolls):

┌──────────────────────────────────┐

│ ░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░ │

│ ░░░░ Level 1-1 Ground ░░░░░░░ │ <- Stored in tile map

│ ░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░ │

│ ██████████████████████████████ │

└──────────────────────────────────┘

Sprite Layer (40 sprites, 8×8 or 8×16 each):

┌──────────────────────────────────┐

│ ┌──┐ │

│ │🍄│ (Sprite 0)│ <- Stored in OAM

│ ┌──┐ └──┘ │ (Object Attribute Memory)

│ │👤│ (Sprite 1) │

│ └──┘ │

└──────────────────────────────────┘

Combined (as displayed):

┌──────────────────────────────────┐

│ ░░░░░░░░░░░░ ┌──┐ ░░░░░░░░░░░ │

│ ░░░░░░░░░░░░ │🍄│ ░░░░░░░░░░░ │ Sprite over background

│ ░░░░░░░┌──┐░░ └──┘ ░░░░░░░░░░░░ │

│ ███████│👤│████████████████████ │ Sprite over ground

│ └──┘ │

└──────────────────────────────────┘

Priority Rules:

- Sprite pixel = transparent (color 0) → Show background

- Sprite priority flag = 0 → Sprite always on top

- Sprite priority flag = 1 → Sprite behind background color 1-3

![]()

Audio/APU Fundamentals

Retro audio was synthesized in real-time using simple waveform generators.

Sound Channels: Building Music from Waves

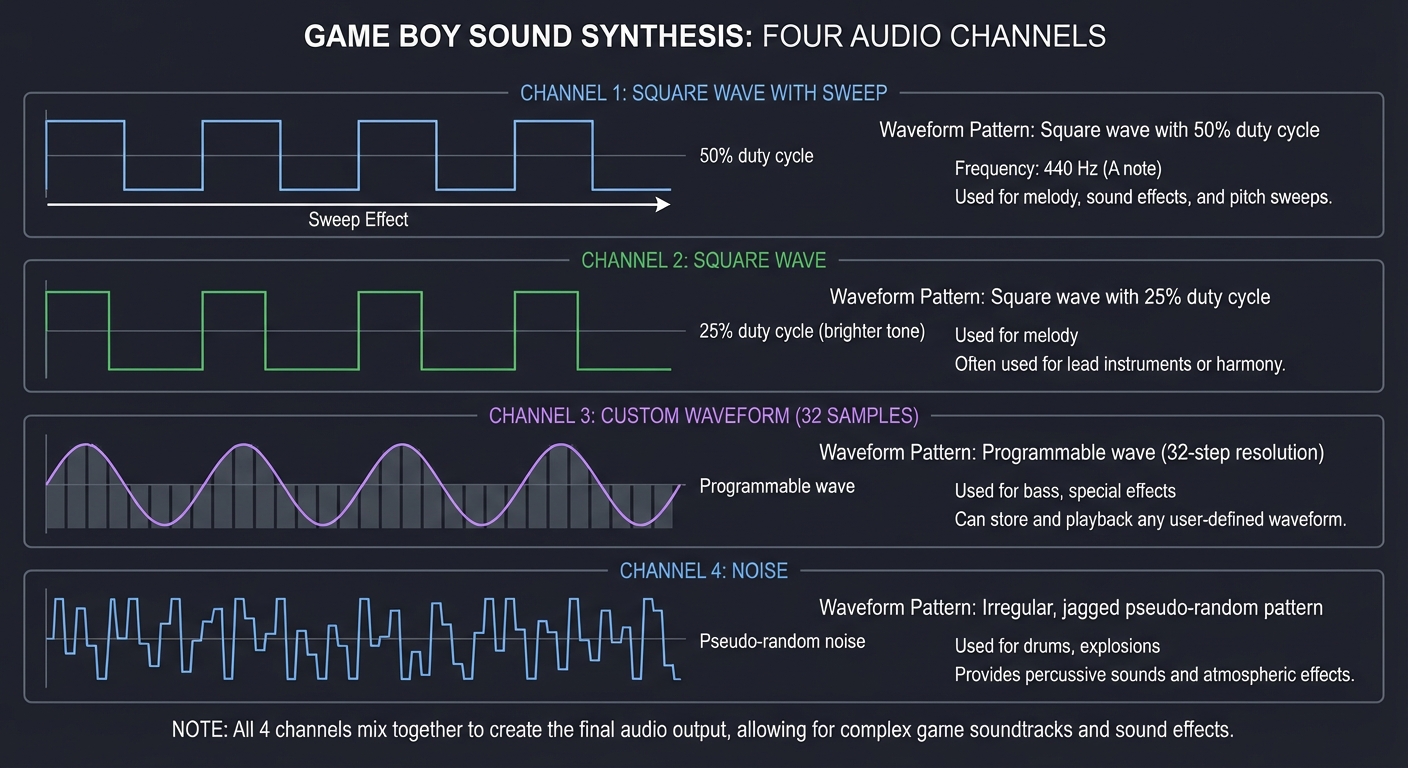

Game Boy has 4 channels, each generating different waveforms:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ AUDIO CHANNELS │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Channel 1: Square Wave with Sweep

____ ____ ____ ← 50% duty cycle

| | | | | |

_| |__| |__| |__ Frequency: 440 Hz (A note)

Channel 2: Square Wave

__ __ __ __ __ ← 25% duty cycle (brighter tone)

| || || || || |

_| || || || || |____ Used for melody

Channel 3: Custom Waveform (32 samples)

/\ /\ /\ ← Programmable wave

/ \ / \ / / \/ \/ \ Used for bass, special effects

Channel 4: Noise

|___|‾|____|‾‾|__|‾|_|‾| ← Pseudo-random noise

Used for drums, explosions

All 4 channels mix together to create the final audio output.

Your emulator generates these waveforms:

// Square wave generation (Channel 1)

int16_t generate_square_wave(Channel *ch) {

// Frequency determines how fast wave oscillates

ch->phase += ch->frequency / SAMPLE_RATE;

if (ch->phase >= 1.0) ch->phase -= 1.0;

// Duty cycle determines wave shape

float threshold = duty_cycles[ch->duty]; // 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75

int16_t amplitude = ch->volume * 512;

return (ch->phase < threshold) ? amplitude : -amplitude;

}

// Mix all channels

int16_t mix_audio() {

int16_t sample = 0;

sample += generate_square_wave(&channel1);

sample += generate_square_wave(&channel2);

sample += generate_wave(&channel3);

sample += generate_noise(&channel4);

return sample / 4; // Average the channels

}

Envelopes: Shaping Sound Over Time

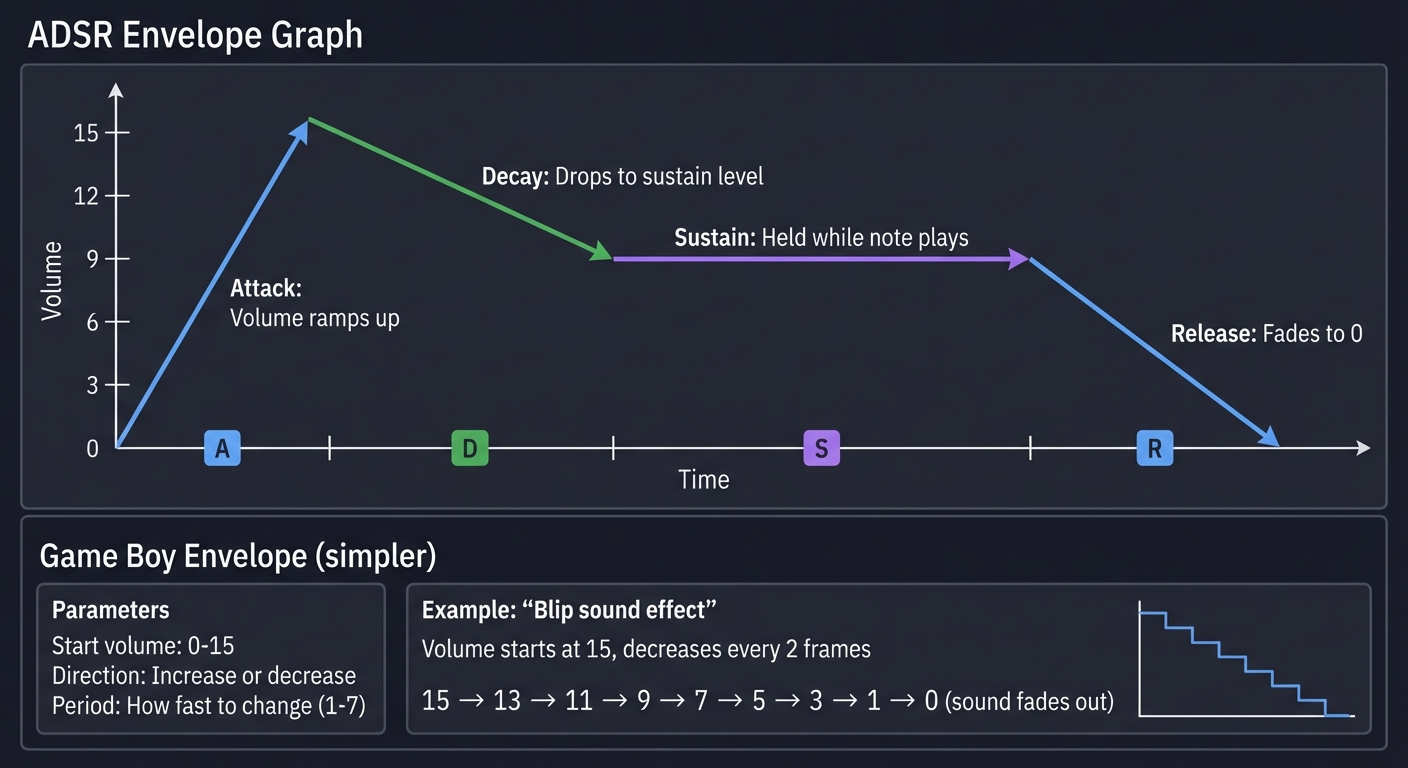

Envelopes control how volume changes over time (think of how a piano note fades):

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ VOLUME ENVELOPE (ADSR) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Volume

^

15│ / │ / \___________ Attack: Volume ramps up

│ / \ Decay: Drops to sustain level

│ / \ Sustain: Held while note plays

│/ \__ Release: Fades to 0

0└────────────────────────> Time

A D Sustain R

Game Boy Envelope (simpler):

- Start volume: 0-15

- Direction: Increase or decrease

- Period: How fast to change (1-7)

Example: "Blip" sound effect

Volume starts at 15, decreases every 2 frames

15 → 13 → 11 → 9 → 7 → 5 → 3 → 1 → 0 (sound fades out)

Timing & Synchronization

Accurate emulation requires running components in sync at precise clock speeds.

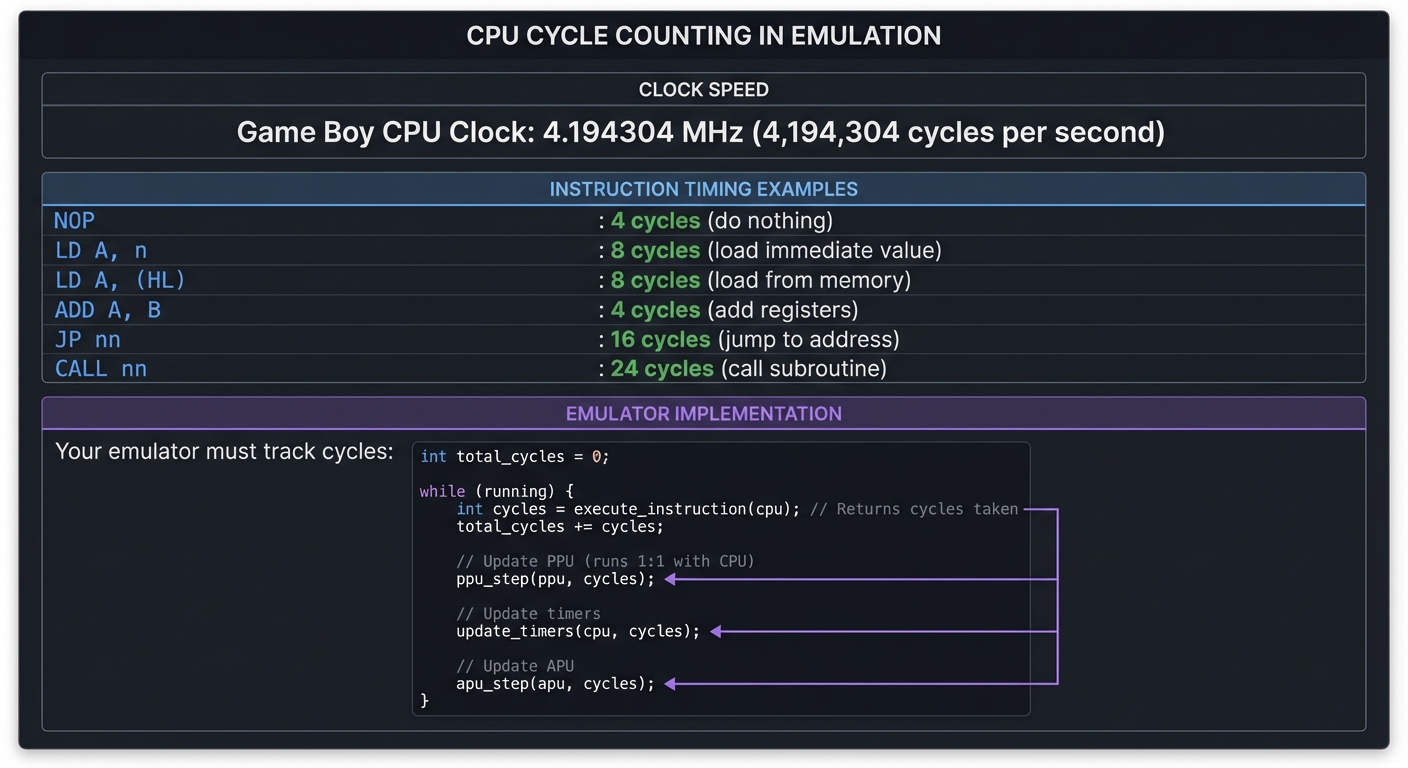

Cycle Counting: The Emulator’s Heartbeat

CPUs don’t execute instructions instantly—each takes a specific number of clock cycles.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ CYCLE COUNTING │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Game Boy CPU Clock: 4.194304 MHz (4,194,304 cycles per second)

Instruction timing examples:

NOP : 4 cycles (do nothing)

LD A, n : 8 cycles (load immediate value)

LD A, (HL) : 8 cycles (load from memory)

ADD A, B : 4 cycles (add registers)

JP nn : 16 cycles (jump to address)

CALL nn : 24 cycles (call subroutine)

Your emulator must track cycles:

int total_cycles = 0;

while (running) {

int cycles = execute_instruction(cpu); // Returns cycles taken

total_cycles += cycles;

// Update PPU (runs 1:1 with CPU)

ppu_step(ppu, cycles);

// Update timers

update_timers(cpu, cycles);

// Update APU

apu_step(apu, cycles);

}

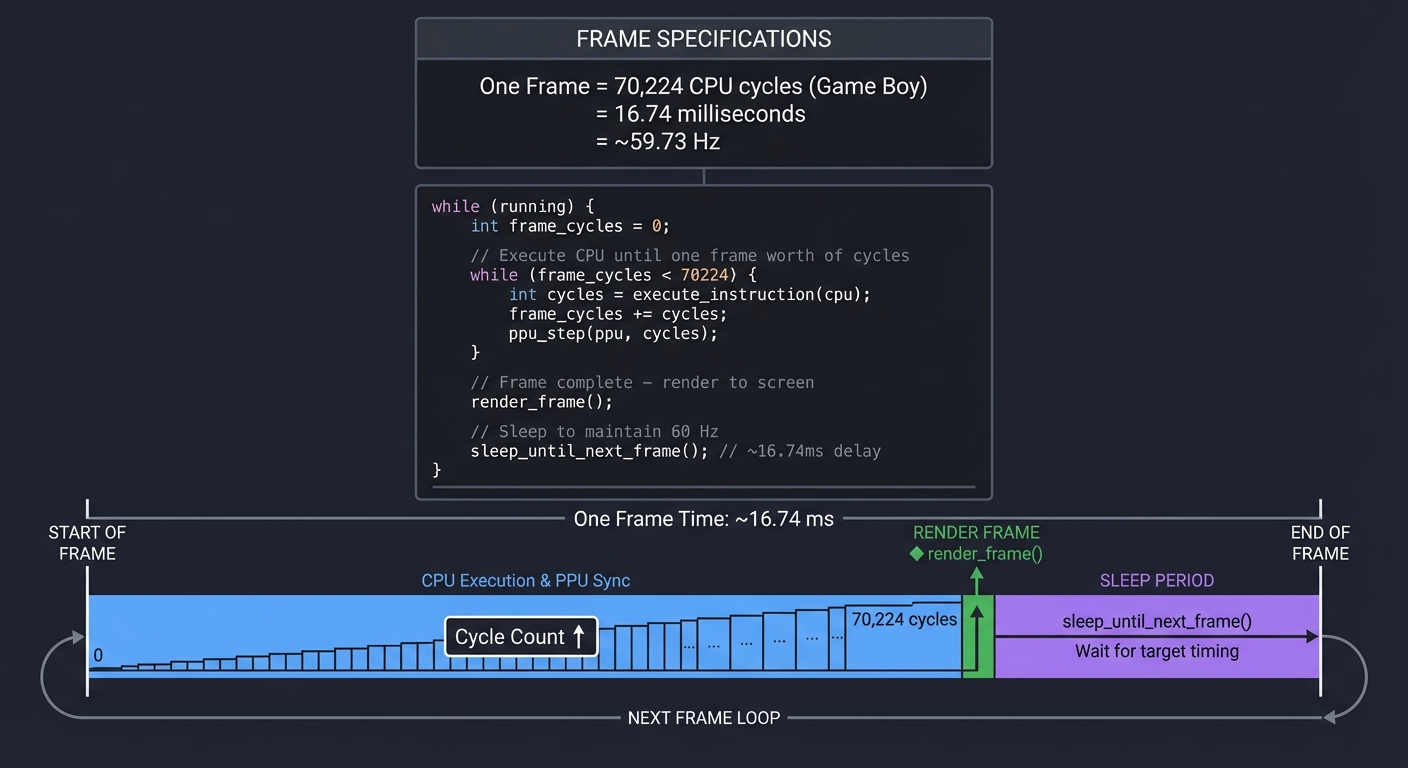

Frame Timing: 60 Hz Synchronization

Retro consoles rendered at 59.73 Hz (NTSC) or 50 Hz (PAL). Your emulator must match this:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ FRAME TIMING │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

One Frame = 70,224 CPU cycles (Game Boy)

= 16.74 milliseconds

= ~59.73 Hz

Emulator loop:

while (running) {

int frame_cycles = 0;

// Execute CPU until one frame worth of cycles

while (frame_cycles < 70224) {

int cycles = execute_instruction(cpu);

frame_cycles += cycles;

ppu_step(ppu, cycles); // PPU keeps pace

}

// Frame complete - render to screen

render_frame();

// Sleep to maintain 60 Hz

sleep_until_next_frame(); // ~16.74ms delay

}

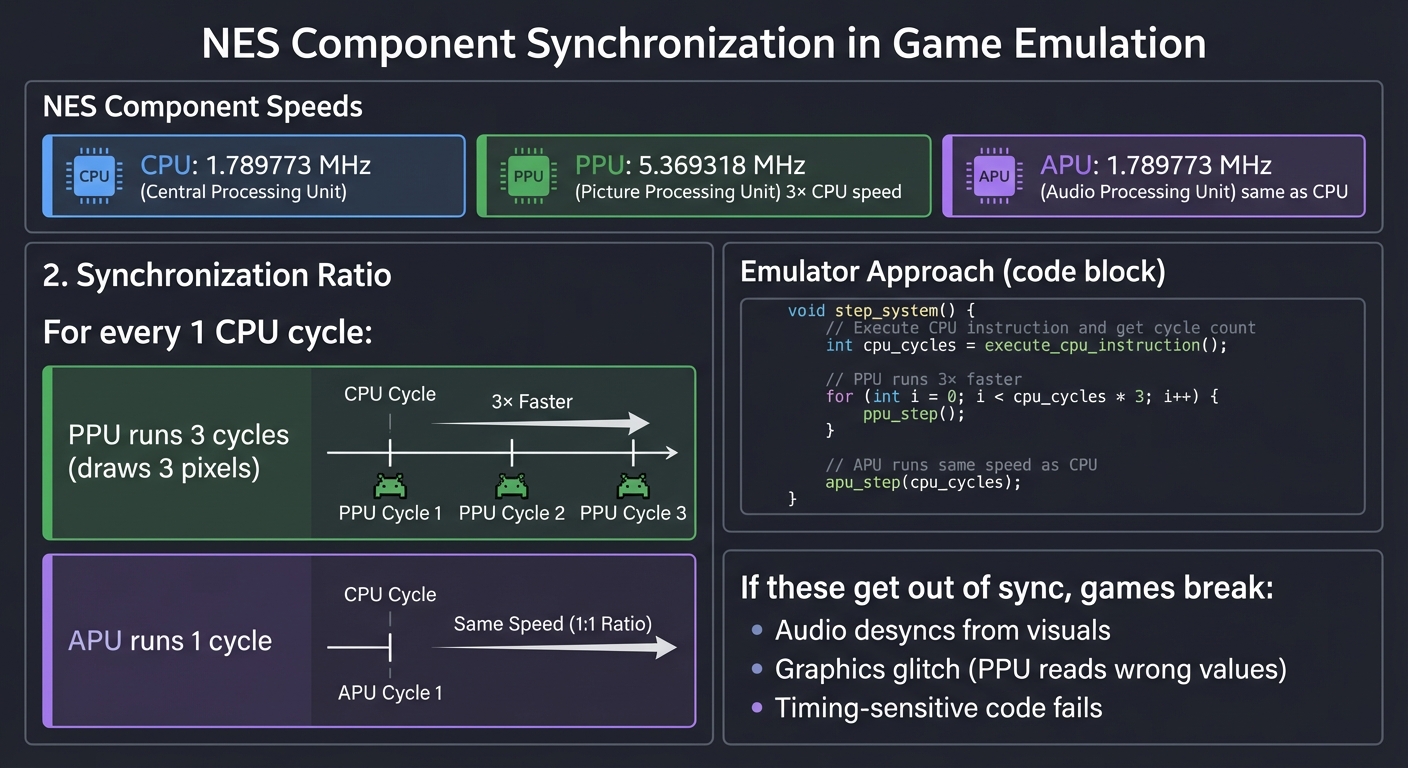

Component Synchronization

CPU, PPU, and APU run at different speeds but must stay synchronized:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ COMPONENT SYNCHRONIZATION │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

NES Example:

CPU: 1.789773 MHz

PPU: 5.369318 MHz (3× CPU speed)

APU: 1.789773 MHz (same as CPU)

For every 1 CPU cycle:

- PPU runs 3 cycles (draws 3 pixels)

- APU runs 1 cycle

Emulator approach:

void step_system() {

int cpu_cycles = execute_cpu_instruction();

// PPU runs 3× faster

for (int i = 0; i < cpu_cycles * 3; i++) {

ppu_step();

}

// APU runs same speed as CPU

apu_step(cpu_cycles);

}

If these get out of sync, games break:

- Audio desyncs from visuals

- Graphics glitch (PPU reads wrong values)

- Timing-sensitive code fails

Concept Summary Table

This table maps high-level concepts to what you need to internalize for building emulators:

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Fetch-Decode-Execute | How instructions are read, parsed, and executed in sequence | This is the CPU’s fundamental loop—every emulator implements this |

| Opcode Decoding | Extracting instruction type and operands from binary | You’ll decode 35 opcodes (CHIP-8) to 500+ opcodes (Game Boy) to thousands (PlayStation) |

| Registers & Flags | CPU internal state: program counter, stack pointer, status flags | All CPU operations manipulate this state; bugs here break everything |

| Memory Maps | Different address ranges map to ROM, RAM, I/O, graphics | Reading 0xFF00 vs 0xC000 does completely different things |

| Memory-Mapped I/O | Hardware registers appear as memory addresses | Writing to 0x8000 changes graphics; reading 0xFF00 reads controller input |

| Bank Switching | Swapping which ROM/RAM is visible at an address | Games larger than 64KB require this; your emulator must track active banks |

| Tile-Based Graphics | Screens built from 8×8 reusable tiles, not individual pixels | Memory-efficient; you’ll implement tile lookup and rendering |

| Scanline Rendering | Drawing the screen line-by-line, matching CRT timing | Games exploit scanline timing for effects; you’ll implement PPU state machines |

| Sprites vs Background | Two layers with priority rules | Games need moving objects (sprites) over scrolling worlds (background) |

| Sound Synthesis | Generating waveforms (square, triangle, noise) mathematically | You’ll implement oscillators, mix channels, and output to speakers |

| Envelopes | Volume changes over time (attack, decay, sustain, release) | Makes sounds musical instead of harsh beeps |

| Cycle Counting | Tracking how many clock cycles elapsed | Games rely on precise timing; off by 1 cycle can break games |

| Frame Timing | Synchronizing to 50/60 Hz refresh rate | Keeps emulator running at correct speed, not too fast or slow |

| Component Sync | CPU, PPU, APU must stay in lockstep | Async components cause audio/video desync and glitches |

| Interrupts | Hardware signals that pause CPU to handle events | V-Blank interrupt signals frame complete; button press triggers interrupt |

| Test-Driven Development | Using test ROMs to verify accuracy | Test ROMs catch subtle bugs; essential for accurate emulation |

Deep Dive Reading By Concept

This table maps each concept to specific book chapters and online resources:

| Concept | Resource | Chapter/Section | Why Read This |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fetch-Decode-Execute | Code: The Hidden Language by Charles Petzold | Chapters 17-18 | Best intuitive explanation of how CPUs work |

| CPU Architecture | Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective by Bryant & O’Hallaron | Chapter 4 | Y86 processor design teaches CPU internals |

| Opcode Decoding | The Secret Life of Programs by Jonathan Steinhart | Chapter 8 | Practical instruction set design |

| Memory Management | Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective by Bryant & O’Hallaron | Chapter 6 | Memory hierarchy, caching, addressing |

| Memory-Mapped I/O | The Secret Life of Programs by Jonathan Steinhart | Chapter 10 | How hardware appears as memory |

| Bitwise Operations | C Programming: A Modern Approach by K.N. King | Chapter 20 | Mastering bit manipulation for opcode decoding |

| Graphics Fundamentals | Computer Graphics from Scratch by Gabriel Gambetta | Chapters 1-3, 11 | Pixel rendering, rasterization, tile systems |

| Tile-Based Rendering | Pan Docs - Rendering | Full page | Definitive Game Boy graphics reference |

| Scanline Rendering | Game Boy Coding Adventure by Maximilien Dagois | Chapter 5 | Practical PPU state machine implementation |

| Sprites & OAM | Pan Docs - OAM | Full page | Sprite attribute memory format and priority |

| Sound Synthesis | Designing Sound by Andy Farnell | Chapters 5-8 | Pure Data sound synthesis from scratch |

| APU Architecture | Pan Docs - Audio | Full page | Game Boy sound hardware specification |

| Digital Audio | Computer Music by Charles Dodge & Thomas Jerse | Chapter 3 | Sample rates, digital waveforms, synthesis |

| Timing & Synchronization | Computer Organization and Design by Patterson & Hennessy | Chapter 5 | Processor timing, pipelining, interrupts |

| Cycle-Accurate Emulation | Emulation Accuracy by endrift | Full article | Why cycle accuracy matters, how to achieve it |

| Interrupts | Computer Organization and Design by Patterson & Hennessy | Chapter 5.6 | Interrupt handling, priorities, vectors |

| 6502 Architecture | NESDev Wiki - CPU | Full page | 6502 opcodes, addressing modes, quirks |

| Z80/LR35902 | Pan Docs - CPU | Full page | Game Boy CPU instruction set reference |

| ARM Architecture | ARM System Developer’s Guide by Andrew Sloss | Chapters 2-4 | ARM7TDMI for Game Boy Advance |

| MIPS Architecture | See MIPS Run by Dominic Sweetman | Chapters 1-5 | MIPS R3000 for PlayStation |

| Test-Driven Development | Test Driven Development by Kent Beck | Chapters 1-5 | Writing test ROMs, verification methodology |

| Binary Analysis | Practical Binary Analysis by Dennis Andriesse | Chapters 2, 6 | Disassembly, reverse engineering, debugging |

| JIT Compilation | Engineering a Compiler by Cooper & Torczon | Chapters 4, 13 | Code generation, register allocation |

| Digital Logic (FPGA) | Digital Design and Computer Architecture by Harris & Harris | Chapters 1-5 | Building CPUs in hardware |

| Verilog (FPGA) | Verilog HDL by Samir Palnitkar | Chapters 2-7 | Hardware description language for FPGAs |

Project Recommendations

The following projects are ordered by difficulty and complexity. Each builds upon concepts learned in previous projects.

Project 1: CHIP-8 Interpreter

- File: RETRO_GAME_EMULATION_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Python, Go

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold” (Educational/Personal Brand)

- Difficulty: Level 1: Beginner (The Tinkerer)

- Knowledge Area: CPU Emulation / Virtual Machines

- Software or Tool: CHIP-8 Virtual Machine

- Main Book: “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” by Bryant & O’Hallaron

What you’ll build: A complete interpreter for the CHIP-8 virtual machine that can run classic games like Pong, Space Invaders, and Tetris clones.

Why it teaches emulation: CHIP-8 is the “Hello World” of emulator development. It has only 35 opcodes, simple graphics (64x32 monochrome), and no complex timing requirements. You’ll learn the fundamental fetch-decode-execute loop that every emulator uses, without getting lost in hardware complexity.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Opcode decoding (parsing 2-byte instructions, extracting operands) → maps to instruction set understanding

- Register management (16 general-purpose registers, I register, timers) → maps to CPU state modeling

- Stack implementation (for subroutine calls/returns) → maps to control flow

- Display rendering (XOR-based sprite drawing) → maps to graphics fundamentals

- Keyboard input mapping (hex keypad to modern keyboard) → maps to I/O handling

Key Concepts:

- Fetch-Decode-Execute: “Code: The Hidden Language” Chapter 17-18 - Charles Petzold

- Bitwise Operations: “C Programming: A Modern Approach” Chapter 20 - K.N. King

- Memory-Mapped I/O: “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” Chapter 6 - Bryant & O’Hallaron

- Stack Machines: “The Secret Life of Programs” Chapter 8 - Jonathan Steinhart

Difficulty: Beginner Time estimate: Weekend to 1 week Prerequisites: Basic C/Rust/Python, understanding of binary/hex

Real world outcome:

- Run classic CHIP-8 ROMs: Pong, Breakout, Space Invaders, Tetris clones

- See pixels appearing on screen as your emulator executes instructions

- Play the games with your keyboard mapped to the hex keypad

$ ./chip8 roms/PONG [CHIP-8] Loading ROM: PONG (246 bytes) [CHIP-8] Starting execution... # A playable Pong game appears in your window!

Learning milestones:

- ROM loads and opcodes print → You understand instruction fetching

- Simple opcodes execute (jumps, register loads) → You’ve built a working CPU core

- Graphics appear on screen → You understand display/sprite rendering

- Games are fully playable → You’ve internalized the emulation loop

Resources:

- CHIP-8 Guide by Tobias V. Langhoff - Excellent high-level walkthrough

- Austin Morlan’s CHIP-8 in C++ - Detailed implementation guide

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How does a processor fetch, decode, and execute instructions in a continuous loop?”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Binary Representation & Hexadecimal

- Can you convert 0x6A02 to binary and explain what each bit might represent?

- Why do we use hexadecimal instead of binary when reading opcodes?

- How many bits are in a CHIP-8 instruction?

- Book: “C Programming: A Modern Approach” Chapter 20 - K.N. King

- Bitwise Operations (AND, OR, XOR, Shifts)

- How would you extract the second nibble from 0x6A02?

- Why does CHIP-8 use XOR for drawing pixels instead of just setting them?

- What’s the difference between » (right shift) and & (bitwise AND) for extracting bits?

- Book: “C Programming: A Modern Approach” Chapter 20 - K.N. King

- Memory as an Array of Bytes

- If memory starts at address 0x200, where is the byte at index 0?

- How do you read a 2-byte instruction from memory at address PC?

- What’s the difference between memory[PC] and *(memory + PC)?

- Book: “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” Chapter 3 - Bryant & O’Hallaron

- The Stack (LIFO Structure)

- When you call a subroutine, what must you save?

- Why does the stack pointer increment when you push and decrement when you pop?

- What happens if you return when the stack is empty?

- Book: “The Secret Life of Programs” Chapter 8 - Jonathan Steinhart

- Program Counter (PC)

- Why does PC automatically advance by 2 after fetching an instruction?

- How does a jump instruction differ from incrementing PC?

- What happens to PC during a subroutine call?

- Book: “Code: The Hidden Language” Chapter 17-18 - Charles Petzold

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Should you decode all 35 opcodes with a giant switch statement, or use a lookup table?

- How will you handle the two-byte instruction format - read byte-by-byte or combine them first?

- Should timers decrement in the main loop or on a separate thread/timer?

- How do you map the CHIP-8 hex keypad (0-F) to a modern QWERTY keyboard?

- Should you render pixels immediately when DRW executes, or buffer them for the next frame?

Thinking Exercise

Trace through this CHIP-8 code by hand. What appears on screen?

Address | Opcode | Instruction

--------|--------|------------

0x200 | 6A 05 | LD VA, 5 (Set V[A] = 5)

0x202 | 6B 02 | LD VB, 2 (Set V[B] = 2)

0x204 | A2 10 | LD I, 0x210 (Set I = 0x210)

0x206 | DA B5 | DRW VA, VB, 5 (Draw 5-byte sprite at (V[A], V[B]))

0x208 | 12 08 | JP 0x208 (Infinite loop)

Memory at 0x210:

0xF0 (11110000)

0x90 (10010000)

0x90 (10010000)

0x90 (10010000)

0xF0 (11110000)

Questions:

- Where on the 64x32 screen will the sprite appear?

- What does the sprite look like? (Hint: Draw it out on graph paper)

- Why is there a jump at the end?

- What happens if the sprite overlaps with something already drawn?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “Walk me through what happens when your emulator executes one frame. Start from reading the ROM.”

- “The instruction 0x8XY4 adds VY to VX and sets VF to 1 if there’s a carry. How do you detect carry in C?”

- “CHIP-8 instructions are 2 bytes but memory is byte-addressable. How do you fetch instructions?”

- “Explain how the XOR-based drawing works. Why does drawing the same sprite twice erase it?”

- “Your emulator runs too fast on modern hardware. How do you throttle it to ~60 FPS?”

- “How would you debug a ROM that displays garbage on screen? What would you check first?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Decoding Instructions The opcode 0x6A02 means “Set register A to 0x02”. Notice the pattern:

- First nibble (6) = instruction type

- Second nibble (A) = which register

- Last two nibbles (02) = the value

uint16_t opcode = 0x6A02;

uint8_t instr = (opcode & 0xF000) >> 12; // 6

uint8_t x = (opcode & 0x0F00) >> 8; // A

uint8_t nn = (opcode & 0x00FF); // 02

Hint 2: The Fetch-Decode-Execute Loop Your main emulation loop should look like:

while (running) {

uint16_t opcode = fetch(PC);

PC += 2;

decode_and_execute(opcode);

update_timers();

if (draw_flag) render();

}

Hint 3: Drawing with XOR When DRW executes, for each pixel in the sprite:

bool pixel = sprite_data & (0x80 >> bit);

bool current = screen[x][y];

screen[x][y] = current ^ pixel; // XOR

if (current && pixel) VF = 1; // Set collision flag

Hint 4: Don’t Overthink It CHIP-8 is simple. No pipeline, no cache, no interrupts (except timers). If your code is getting complex, you’re probably overengineering. Start with the simplest implementation that could possibly work.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter | |——-|——|———| | Fetch-Decode-Execute | “Code: The Hidden Language” by Charles Petzold | 17-18 | | Bitwise Operations | “C Programming: A Modern Approach” by K.N. King | 20 | | Memory & Pointers | “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” by Bryant & O’Hallaron | 3, 6 | | Stack Machines | “The Secret Life of Programs” by Jonathan Steinhart | 8 | | Binary/Hex Arithmetic | “The Elements of Computing Systems” by Nisan & Schocken | 1-2 |

Project 2: CHIP-8 Disassembler & Debugger

- File: RETRO_GAME_EMULATION_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Python, Go

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold” (Educational/Personal Brand)

- Difficulty: Level 1: Beginner (The Tinkerer)

- Knowledge Area: Reverse Engineering / Debugging Tools

- Software or Tool: Debugger / Disassembler

- Main Book: “Practical Binary Analysis” by Dennis Andriesse

What you’ll build: A tool that converts CHIP-8 binary ROM files back into readable assembly, plus a step-debugger that lets you execute one instruction at a time, inspect registers, set breakpoints, and watch memory.

Why it teaches emulation: Understanding what a program does at the instruction level is essential for debugging emulators. When your emulator doesn’t work, you need to see exactly what’s happening. Building the debugger forces you to deeply understand the instruction set.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Binary parsing (reading raw bytes, interpreting as instructions) → maps to machine code understanding

- Instruction formatting (turning

0x6A02intoLD VA, 0x02) → maps to assembly language - Breakpoint implementation (stopping execution at specific addresses) → maps to debugger internals

- State inspection (displaying registers, memory, stack in real-time) → maps to system introspection

- Single-stepping (executing exactly one instruction, then pausing) → maps to execution control

Key Concepts:

- Binary File Parsing: “Practical Binary Analysis” Chapter 2 - Dennis Andriesse

- Disassembly Techniques: “Practical Binary Analysis” Chapter 6 - Dennis Andriesse

- Debugger Architecture: “The Art of Debugging” Chapter 1 - Norman Matloff

Difficulty: Beginner Time estimate: Weekend Prerequisites: Completed CHIP-8 interpreter

Real world outcome:

- Load any CHIP-8 ROM and see human-readable assembly listing

- Step through execution instruction by instruction

- Set breakpoints and watch the program pause when hit

- Inspect register values and memory contents at any point

$ ./chip8dbg roms/PONG 0x200: LD V0, 0x00 0x202: LD V1, 0x00 0x204: LD I, 0x2EA 0x206: DRW V0, V1, 5 ... (dbg)> break 0x220 Breakpoint set at 0x220 (dbg)> run Hit breakpoint at 0x220 (dbg)> regs V0=0x1F V1=0x10 V2=0x00 ... PC=0x220 I=0x2EA

Learning milestones:

- Disassembler outputs readable assembly → You understand instruction encoding

- Single-step works correctly → You’ve separated fetch from execute

- Breakpoints pause execution → You understand program counter manipulation

- Full debugging session works → You can debug your own emulator bugs

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do you reverse-engineer binary code into human-readable form and control execution flow for debugging?”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Instruction Encoding/Decoding

- How is the instruction 0x6A02 different from 0x7A02 in terms of what it does?

- Can you write a function that takes a 2-byte opcode and returns a string like “LD VA, 0x02”?

- Why can’t you just disassemble from byte 0? Where should disassembly start?

- Book: “Practical Binary Analysis” Chapter 2 - Dennis Andriesse

- String Formatting in C

- How do you format “LD V%X, 0x%02X” to produce “LD VA, 0x02”?

- What’s the difference between %X, %02X, and %04X?

- How do you build strings dynamically without buffer overflows?

- Book: “C Programming: A Modern Approach” Chapter 22 - K.N. King

- Breakpoints as Program Counter Checks

- Where in your emulation loop should you check for breakpoints?

- Should you check before or after incrementing the PC?

- What data structure is best for storing breakpoint addresses - array, linked list, hash set?

- Book: “The Art of Debugging” Chapter 1 - Norman Matloff

- State Inspection without Modifying State

- How do you display memory contents without affecting the running program?

- Should register inspection be a read-only operation?

- What’s the difference between displaying memory and watching memory for changes?

- Book: “The Art of Debugging” Chapter 3 - Norman Matloff

- Single-Stepping Implementation

- What’s the simplest way to execute exactly one instruction?

- Should single-step be implemented as a special breakpoint?

- How do you prevent the emulator from continuing after a step?

- Book: “Practical Binary Analysis” Chapter 6 - Dennis Andriesse

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Should your disassembler be a separate tool, or integrated into your emulator?

- How will you handle invalid opcodes - display as “???” or try to interpret them?

- Should breakpoints persist across emulator restarts (save to file)?

- What’s the minimum debugger UI - command-line REPL, or do you need a GUI?

- How do you represent the current instruction differently from upcoming instructions (highlighting)?

Thinking Exercise

You’re debugging a Pong game that glitches when the ball reaches the right edge. You set a breakpoint at 0x240 where the ball position is updated:

(dbg)> break 0x240

(dbg)> run

Hit breakpoint at 0x240: LD V2, 0x3F

(dbg)> regs

V0=0x05 V1=0x1F V2=0x3E V3=0x00 ... PC=0x240

(dbg)> mem 0x240 16

0x240: 62 3F 83 24 63 00 40 00 |b?.$c.@.|

0x248: 60 02 F0 15 F0 07 30 00 |`.....0.|

(dbg)> step

Hit breakpoint at 0x242: ADD V2, V4

(dbg)> regs

V2=0x3F V4=0x02 ...

(dbg)> step

V2=0x41 # Overflow! Should wrap to 0x00 but screen is only 64 pixels wide

Questions:

- What instruction should check for screen boundary wrapping?

- How would you use the debugger to find where the bug occurs?

- If you wanted to “fix” the ROM temporarily, what would you patch?

- How would a memory watch on V2 help find this bug faster?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “How does a debugger’s breakpoint work at the assembly level? Does it modify the code?”

- “You’re disassembling a ROM but some instructions appear as garbage. What could cause this?”

- “Explain the difference between ‘step over’ and ‘step into’ for a CALL instruction. Would CHIP-8 need both?”

- “Your debugger needs to display 4KB of memory. How do you format it for readability?”

- “How would you implement a ‘watch’ feature that breaks when a register changes value?”

- “What’s the difference between a debugger’s ‘run’ and your emulator’s normal execution?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Disassembly is Just Pattern Matching

char* disassemble(uint16_t opcode) {

static char buffer[32];

uint8_t x = (opcode & 0x0F00) >> 8;

uint8_t y = (opcode & 0x00F0) >> 4;

uint8_t n = (opcode & 0x000F);

uint16_t nnn = (opcode & 0x0FFF);

switch (opcode & 0xF000) {

case 0x6000: sprintf(buffer, "LD V%X, 0x%02X", x, opcode & 0xFF); break;

case 0xA000: sprintf(buffer, "LD I, 0x%03X", nnn); break;

// ... etc

}

return buffer;

}

Hint 2: Breakpoints are Just Address Comparisons

bool breakpoints[4096] = {0}; // One bool per memory address

void set_breakpoint(uint16_t addr) {

breakpoints[addr] = true;

}

// In your main loop:

if (breakpoints[PC]) {

printf("Hit breakpoint at 0x%03X\n", PC);

enter_debugger_shell();

}

Hint 3: Single-Step is a Temporary Breakpoint

bool single_step_mode = false;

void step() {

execute_one_instruction();

enter_debugger_shell(); // Return to debugger after one instruction

}

Hint 4: A Simple REPL is Enough You don’t need a fancy GUI. A command-line debugger is powerful:

void debugger_shell() {

char cmd[64];

while (1) {

printf("(dbg)> ");

fgets(cmd, sizeof(cmd), stdin);

if (starts_with(cmd, "break")) { /* ... */ }

else if (starts_with(cmd, "run")) { break; }

else if (starts_with(cmd, "step")) { /* ... */ }

else if (starts_with(cmd, "regs")) { dump_registers(); }

}

}

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter | |——-|——|———| | Disassembly Techniques | “Practical Binary Analysis” by Dennis Andriesse | 2, 6 | | Debugger Internals | “The Art of Debugging” by Norman Matloff | 1-3 | | String Formatting | “C Programming: A Modern Approach” by K.N. King | 22 | | Binary File Parsing | “Practical Binary Analysis” by Dennis Andriesse | 3 | | Reverse Engineering | “Practical Reverse Engineering” by Dang et al. | 1 |

Project 3: Intel 8080 Space Invaders Arcade Emulator

- File: RETRO_GAME_EMULATION_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, C++, Go

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold” (Educational/Personal Brand)

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate (The Developer)

- Knowledge Area: CPU Emulation / Arcade Hardware

- Software or Tool: Intel 8080 CPU / Arcade Cabinet

- Main Book: “Computer Organization and Design” by Patterson & Hennessy

What you’ll build: A complete emulator for the 1978 Space Invaders arcade cabinet, including the Intel 8080 CPU, dedicated video hardware, and sound effects.

Why it teaches emulation: The 8080 is a “real” CPU with a documented instruction set. Unlike CHIP-8, you’ll deal with cycle timing, hardware interrupts (screen drawing triggers interrupts), and external hardware (shift register for the video display). This is your first taste of emulating actual silicon.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Full 8080 instruction set (256 opcodes, flags, addressing modes) → maps to real CPU architecture

- Cycle-accurate timing (2 MHz clock, instructions take different cycles) → maps to timing accuracy

- Hardware interrupts (RST 1 and RST 2 at screen midpoint and vblank) → maps to interrupt handling

- External shift register (hardware assist for video memory) → maps to custom hardware

- Rotated display (screen is 90° rotated, 1-bit per pixel) → maps to framebuffer manipulation

Key Concepts:

- 8080 Architecture: Emulator101 8080 Reference

- Interrupt Handling: “Computer Organization and Design” Chapter 5 - Patterson & Hennessy

- Cycle Counting: “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” Chapter 4 - Bryant & O’Hallaron

- Memory-Mapped Hardware: “The Secret Life of Programs” Chapter 10 - Jonathan Steinhart

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 2-3 weeks Prerequisites: CHIP-8 complete, comfort with binary operations

Real world outcome:

- Play the actual 1978 Space Invaders game

- See the classic alien invasion, shoot them down, watch them speed up

- Hear the iconic sound effects (dun-dun-dun-dun)

- Insert virtual coins and start games

$ ./spaceinvaders roms/invaders.zip [8080] ROM loaded: 8KB [8080] Starting at 2MHz... # The classic Space Invaders title screen appears! # Press 1 to insert coin, ENTER to start # Arrow keys to move, SPACE to fire

Learning milestones:

- CPU passes test ROMs (cpudiag) → Your 8080 is correctly implemented

- Something appears on screen → Interrupts and display work

- Game is playable → Timing and input are correct

- Sound effects play → You understand output ports

Resources:

- Emulator101.com - The canonical Space Invaders emulator guide

- Computer Archeology - Space Invaders Hardware - Detailed hardware docs

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do hardware interrupts work, and how does timing accuracy affect whether a game plays correctly?”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- CPU Flags Register (Zero, Sign, Parity, Carry, Auxiliary Carry)

- When you ADD two numbers and get 0, which flags change?

- How is the Carry flag different from overflow?

- Why does the 8080 have both Carry and Auxiliary Carry flags?

- What does the Parity flag tell you about a byte?

- Book: “Computer Organization and Design” Chapter 2 - Patterson & Hennessy

- Hardware Interrupts vs Software Interrupts

- What’s the difference between RST (restart) and CALL?

- When the screen hits mid-frame, how does the hardware tell the CPU?

- Should interrupts execute immediately or wait for the current instruction to finish?

- What happens to the Program Counter when an interrupt occurs?

- Book: “Computer Organization and Design” Chapter 5 - Patterson & Hennessy

- Cycle-Accurate Timing

- If the CPU runs at 2 MHz, how many cycles per 60 Hz frame?

- Why do different instructions take different numbers of cycles?

- How do you track partial cycles (instruction takes 10 cycles, you’ve executed 7)?

- Book: “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” Chapter 4 - Bryant & O’Hallaron

- Memory-Mapped I/O vs Port-Mapped I/O

- The 8080 uses IN/OUT instructions for ports. How is this different from reading memory?

- Why does Space Invaders read input from port 1 instead of a memory address?

- What happens when you write to port 2 (shift register)?

- Book: “The Secret Life of Programs” Chapter 10 - Jonathan Steinhart

- Framebuffer and Video Memory

- Space Invaders has 256x224 pixels, 1 bit per pixel. How many bytes is that?

- Why is the screen rotated 90 degrees in memory?

- If bit 0 of byte 0x2400 is set, where does that pixel appear on screen?

- Book: “Computer Graphics from Scratch” Chapter 1 - Gabriel Gambetta

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Should you implement all 256 8080 opcodes first, or start with a subset and expand?

- How do you test your CPU before graphics work (use cpudiag.bin test ROM)?

- Should interrupts fire after a specific number of cycles, or based on scanline position?

- How do you map the rotated framebuffer to your display library (SDL, etc.)?

- Should the shift register be a separate hardware component or just two bytes?

Thinking Exercise

The screen refreshes at 60 Hz. The CPU runs at 2 MHz. Two interrupts fire per frame:

- RST 1 (interrupt vector 0x08) fires when the screen reaches scanline 96 (mid-screen)

- RST 2 (interrupt vector 0x10) fires when the screen reaches scanline 224 (vblank)

Cycles per frame = 2,000,000 Hz / 60 Hz = 33,333 cycles

First interrupt (mid-screen) = 33,333 * (96/224) ≈ 14,285 cycles

Second interrupt (vblank) = 33,333 cycles

Questions:

- If you track cycles and call the interrupt at exactly 14,285 cycles, what could go wrong?

- What happens if an instruction is in the middle of executing when the interrupt should fire?

- How do you save the CPU state when an interrupt fires?

- Why does the game need two interrupts instead of just one at vblank?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “Explain how the 8080’s flags register works. Give an example instruction that sets multiple flags.”

- “The Space Invaders shift register is 2 bytes but only outputs 1 byte. How does it work?”

- “Your emulator runs Space Invaders but the aliens move too fast. What’s wrong?”

- “How do you implement the 8080’s DAA (Decimal Adjust Accumulator) instruction?”

- “The game writes to port 3 and 5 for sound. How would you handle this in your emulator?”

- “Why can’t you just check for interrupts every N instructions instead of tracking cycles?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Use a Test ROM First Don’t debug Space Invaders with your half-working CPU. Use cpudiag.bin:

// cpudiag.bin tests all 8080 instructions

// If your CPU is correct, it prints "CPU IS OPERATIONAL"

// If not, it prints which test failed

$ ./emu cpudiag.bin

CPU IS OPERATIONAL

Hint 2: Cycle Timing Table Each instruction takes a specific number of cycles:

int cycles_table[256] = {

4, 10, 7, 5, 5, 5, 7, 4, // 0x00-0x07

4, 10, 7, 5, 5, 5, 7, 4, // 0x08-0x0F

// ... etc (look up in 8080 manual)

};

uint8_t opcode = memory[PC];

int cycles = execute_instruction(opcode);

total_cycles += cycles;

Hint 3: Interrupt Implementation

void emulate_frame() {

int cycles = 0;

while (cycles < CYCLES_PER_FRAME) {

// Execute one instruction

cycles += execute_instruction();

// Check for interrupts

if (cycles >= CYCLES_PER_HALF_FRAME && !mid_frame_interrupt_done) {

generate_interrupt(1); // RST 1

mid_frame_interrupt_done = true;

}

}

// End of frame

generate_interrupt(2); // RST 2

mid_frame_interrupt_done = false;

}

void generate_interrupt(int num) {

if (interrupts_enabled) {

push_word(PC); // Save return address

PC = num * 8; // Jump to interrupt vector

interrupts_enabled = false;

}

}

Hint 4: The Shift Register Mystery Port 2 sets the shift offset. Port 4 writes to the shift register. Port 3 reads the shifted result:

uint16_t shift_register = 0;

uint8_t shift_offset = 0;

void write_port(uint8_t port, uint8_t value) {

switch(port) {

case 2: shift_offset = value & 0x7; break;

case 4: shift_register = (shift_register >> 8) | (value << 8); break;

}

}

uint8_t read_port(uint8_t port) {

if (port == 3) {

return (shift_register >> (8 - shift_offset)) & 0xFF;

}

// ... handle other ports

}

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter | |——-|——|———| | 8080 Architecture | 8080 Programmer’s Manual | All | | Interrupt Handling | “Computer Organization and Design” by Patterson & Hennessy | 5 | | Cycle Counting | “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” by Bryant & O’Hallaron | 4 | | I/O Ports | “The Secret Life of Programs” by Jonathan Steinhart | 10 | | Framebuffers | “Computer Graphics from Scratch” by Gabriel Gambetta | 1 |

Project 4: Game Boy (DMG) Emulator - CPU Only

- File: RETRO_GAME_EMULATION_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, C++, Zig

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold” (Educational/Personal Brand)

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced (The Engineer)

- Knowledge Area: CPU Emulation / Handheld Consoles

- Software or Tool: Game Boy / Sharp LR35902 CPU

- Main Book: “Game Boy Coding Adventure” by Maximilien Dagois

What you’ll build: The CPU core of a Game Boy emulator - the Sharp LR35902 (a Z80-like processor) that can execute instructions, pass test ROMs, and run simple homebrew.

Why it teaches emulation: The Game Boy CPU is more complex than the 8080 but extensively documented. You’ll implement 500+ opcodes (including the CB-prefixed set), deal with the flag register quirks, and learn to use test ROMs to validate your implementation. This is a real production-quality CPU emulator.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Extended instruction set (256 base + 256 CB-prefixed opcodes) → maps to complete CPU implementation

- Flag register quirks (half-carry, specific flag behaviors) → maps to edge case handling

- Memory banking basics (ROM/RAM bank switching via MBC) → maps to memory controller logic

- Test ROM validation (Blargg’s test ROMs, mooneye) → maps to test-driven development

- Interrupt system (5 interrupt sources, IME flag) → maps to interrupt priorities

Key Concepts:

- LR35902 Opcode Reference: Pan Docs - CPU

- Z80-style Architecture: “Game Boy Coding Adventure” Chapter 2 - Maximilien Dagois

- Test-Driven Emulation: Blargg’s Test ROMs

- Flag Behavior: “Game Boy: Complete Technical Reference” - gekkio

Difficulty: Intermediate-Advanced Time estimate: 2-4 weeks (CPU only) Prerequisites: Space Invaders complete, understanding of interrupts

Real world outcome:

- CPU passes Blargg’s cpu_instrs test ROM (all 11 tests)

- Run simple Game Boy homebrew that uses only CPU/serial output

- See test results printed to serial console or screen

$ ./gameboy tests/cpu_instrs.gb [GB] Running cpu_instrs... 01:ok 02:ok 03:ok 04:ok 05:ok 06:ok 07:ok 08:ok 09:ok 10:ok 11:ok Passed all tests!

Learning milestones:

- Opcodes decode correctly → You understand the instruction encoding

- Simple test ROMs pass → Basic instructions work

- All Blargg cpu_instrs pass → Your CPU is production-ready

- Interrupts work correctly → You can handle async events

Resources:

- Pan Docs - The definitive Game Boy technical reference

- Cinoop Tutorial - Practical Game Boy emulator walkthrough

- Inspired Python - Game Boy Emulator - Detailed Python tutorial

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do you implement a complex, production-quality CPU with 500+ opcodes, verify correctness with test ROMs, and handle subtle flag behaviors?”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Extended Instruction Sets (CB-Prefixed Opcodes)

- Why does the Game Boy need a CB prefix byte for some instructions?

- How do you decode 0xCB followed by 0x37? What instruction is this?

- Do CB-prefixed instructions take extra cycles?

- Book: “Game Boy Coding Adventure” Chapter 2 - Maximilien Dagois

- Half-Carry Flag (H Flag)

- What is a half-carry and why does it exist?

- When adding 0x0F + 0x01, which flags are set?

- Why does the DAA (Decimal Adjust) instruction need the H flag?

- How is half-carry different from regular carry?

- Book: Pan Docs - CPU Instruction Set

- Test-Driven Development with ROMs

- What is Blargg’s cpu_instrs test ROM and why is it important?

- How do test ROMs communicate results (serial output, memory locations)?

- Why test with ROMs instead of unit tests?

- Book: “Test Driven Development” by Kent Beck

- Memory Banking (MBC - Memory Bank Controller)

- Why can’t the Game Boy access more than 32KB of ROM directly?

- How does writing to ROM addresses 0x2000-0x3FFF switch ROM banks?

- What’s the difference between MBC1, MBC3, and MBC5?

- Book: Pan Docs - Memory Bank Controllers

- Interrupt Priorities and IME (Interrupt Master Enable)

- What are the 5 interrupt sources on Game Boy?

- What’s the difference between IME (interrupt master enable) and IE (interrupt enable)?

- If VBlank and Timer interrupts fire simultaneously, which executes first?

- Why is there a one-instruction delay after EI (enable interrupts)?

- Book: “Game Boy: Complete Technical Reference” by gekkio

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Should you implement all 256 base opcodes + 256 CB opcodes at once, or incrementally?

- How do you structure your code - one giant switch, or separate function per opcode?

- Should you run test ROMs from the start, or implement blindly then test?

- How will you debug when a test ROM fails - single-step through thousands of instructions?

- Should your opcode table include cycle counts, or calculate them dynamically?

Thinking Exercise

Trace through this Game Boy code and predict the flag register after each instruction:

Initially: A=0x3A, B=0xC9, F=0x00

1. ADD A, B ; A = 0x3A + 0xC9 = 0x03, Carry=1, HalfCarry=1, Zero=0

2. SUB B ; A = 0x03 - 0xC9 = 0x3A (with borrow), Carry=1, HalfCarry=?, Zero=0

3. AND A ; A = 0x3A & 0x3A = 0x3A, Carry=0, HalfCarry=1, Zero=0

4. XOR A ; A = 0x3A ^ 0x3A = 0x00, Carry=0, HalfCarry=0, Zero=1

Questions:

- Why does ADD set both Carry and HalfCarry?

- What’s the half-carry behavior for SUB? (Hint: Check if lower nibble borrowed)

- Why does AND always set HalfCarry=1 on Game Boy?

- After XOR A, what is the complete F register value?

Now consider the CB-prefixed instruction:

A = 0b10110101

CB 37 ; SWAP A, then SET 6,A

What is A after execution?

Step 1: SWAP → 0b01011011

Step 2: SET 6 → 0b01011011 | 0b01000000 = 0b01011011 (wait, bit 6 already set!)

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “Explain the difference between the Game Boy’s Sharp LR35902 CPU and the Z80. What’s missing?”

- “Walk me through how you’d implement the SWAP instruction. Which flags does it affect?”

- “Blargg’s test 03 (bit operations) fails. How would you debug this?”

- “The half-carry flag is confusing. Explain when it’s set for ADD, SUB, and INC instructions.”

- “How do you handle the one-instruction delay after EI (enable interrupts)?”

- “Your emulator passes cpu_instrs but fails on real games. What could cause this?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with Test ROMs Don’t implement blindly. Run Blargg’s cpu_instrs from instruction 1:

// Load blargg_cpu_instrs/01-special.gb

// This tests: NOP, STOP, HALT, DI, EI, etc.

// Expected output (via serial): "01-special Passed"

// If it fails, you know exactly which category is broken

Hint 2: Flag Calculation Helpers

void set_flags_add(uint8_t a, uint8_t b, bool carry_in) {

uint16_t result = a + b + carry_in;

FLAG_Z = ((result & 0xFF) == 0);

FLAG_N = 0; // Addition clears N

FLAG_H = ((a & 0xF) + (b & 0xF) + carry_in) > 0xF; // Half-carry

FLAG_C = (result > 0xFF); // Carry

}

void set_flags_sub(uint8_t a, uint8_t b, bool carry_in) {

int result = a - b - carry_in;

FLAG_Z = ((result & 0xFF) == 0);

FLAG_N = 1; // Subtraction sets N

FLAG_H = ((a & 0xF) - (b & 0xF) - carry_in) < 0; // Half-borrow

FLAG_C = (result < 0); // Borrow

}

Hint 3: CB-Prefix Handling

uint8_t opcode = fetch_byte(PC++);

if (opcode == 0xCB) {

uint8_t cb_opcode = fetch_byte(PC++);

execute_cb_opcode(cb_opcode);

cycles = cb_cycles_table[cb_opcode];

} else {

execute_opcode(opcode);

cycles = cycles_table[opcode];

}

Hint 4: Use Lookup Tables for Repetitive Opcodes Many opcodes are identical except for the register:

// Instead of 8 separate cases for LD r, n

const uint8_t* reg_map[8] = {&B, &C, &D, &E, &H, &L, &(memory[HL]), &A};

// Opcode 0x06, 0x0E, 0x16, 0x1E, 0x26, 0x2E, 0x36, 0x3E

case 0x06: case 0x0E: case 0x16: case 0x1E:

case 0x26: case 0x2E: case 0x36: case 0x3E: {

uint8_t reg_index = (opcode >> 3) & 0x7;

*reg_map[reg_index] = fetch_byte(PC++);

break;

}

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter | |——-|——|———| | LR35902 Architecture | Pan Docs - CPU | All | | Z80-style CPUs | “Game Boy Coding Adventure” by Maximilien Dagois | 2 | | Flag Behaviors | “Game Boy: Complete Technical Reference” by gekkio | CPU section | | Test-Driven Emulation | Blargg’s Test ROMs | README | | Memory Controllers | Pan Docs - MBC | All | | Interrupt System | “Computer Organization and Design” by Patterson & Hennessy | 5 |

Project 5: Game Boy PPU (Graphics) Implementation

- File: RETRO_GAME_EMULATION_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, C++, Zig

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold” (Educational/Personal Brand)

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced (The Engineer)

- Knowledge Area: Graphics Rendering / PPU Emulation

- Software or Tool: Game Boy PPU

- Main Book: “Computer Graphics from Scratch” by Gabriel Gambetta

What you’ll build: The Picture Processing Unit for your Game Boy emulator - tile-based backgrounds, window layer, sprite rendering, and proper timing.

Why it teaches emulation: The Game Boy PPU is a masterclass in understanding how retro consoles render graphics. You’ll learn about tile maps, sprite tables, palettes, and most importantly - scanline-based rendering with precise timing. Games like Road Rash rely on mid-scanline register changes.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Tile-based rendering (8x8 pixel tiles, 384 tiles in VRAM) → maps to character-based graphics

- Background scrolling (SCX/SCY registers, wrapping) → maps to viewport management

- Sprite rendering (OAM, 40 sprites, 10-per-line limit) → maps to object rendering

- Scanline timing (mode 0/1/2/3 transitions) → maps to PPU state machine

- STAT interrupts (LY=LYC, mode transitions) → maps to graphics-driven interrupts

Key Concepts:

- Tile-Based Graphics: “Computer Graphics from Scratch” Chapter 11 - Gabriel Gambetta

- PPU State Machine: Pan Docs - Rendering

- Sprite Priority: Pan Docs - OAM

- Scanline Rendering: “Game Boy Coding Adventure” Chapter 5 - Maximilien Dagois

Difficulty: Advanced Time estimate: 2-3 weeks Prerequisites: Game Boy CPU complete

Real world outcome:

- See the Nintendo logo scroll down during boot

- Watch title screens render with backgrounds and sprites

- Play games like Tetris, Dr. Mario, and Pokemon Red

$ ./gameboy roms/tetris.gb [GB] Loading Tetris... # The Nintendo logo scrolls down # Tetris title screen appears with the Russian buildings # Tetrominoes fall and you can play!

Learning milestones:

- Nintendo logo appears → Basic tile rendering works

- Background scrolls correctly → SCX/SCY implementation is correct

- Sprites render → OAM parsing works

- Games are playable → Timing is accurate enough for real games

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How does a retro console draw 144 lines of pixels 60 times per second using only 8KB of video RAM and a state machine?”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Tile-Based Graphics Systems

- Why use 8x8 tiles instead of a framebuffer? What’s the memory advantage?

- How do tile maps work? How does the PPU translate tile indices to pixel data?

- Book: “Computer Graphics from Scratch” Chapter 11 - Gabriel Gambetta

- Resource: Pan Docs - Tile Data

- Scanline Rendering

- What are the 4 PPU modes (OAM search, pixel transfer, H-blank, V-blank)?

- Why does the PPU draw one line at a time instead of the whole screen?

- How do games use H-blank and V-blank for safe VRAM access?

- Book: “Game Boy Coding Adventure” Chapter 5 - Maximilien Dagois

- Sprite Priority and Rendering

- How does OAM (Object Attribute Memory) store sprite data?

- What’s the 10-sprite-per-scanline limit and why does it exist?

- How does sprite priority work (lower X coordinate wins)?

- Resource: Pan Docs - OAM

- Background Scrolling

- How do SCX/SCY registers implement infinite scrolling with wrapping?

- What’s the difference between background and window layers?

- How can games change scroll values mid-frame for parallax effects?

- Book: “Game Boy: Complete Technical Reference” - gekkio

- PPU State Machine and Timing

- How long does each PPU mode take (in clock cycles)?

- How do STAT interrupts allow games to synchronize with rendering?

- Why is LY=LYC comparison important for raster effects?

- Resource: Pan Docs - STAT Interrupt

Questions to Guide Your Design

-

Data Structure Design: How will you store tiles, tile maps, and sprite data? Will you cache decoded tiles or decode on-the-fly?

-

Scanline Rendering: Will you render the entire scanline at once or pixel-by-pixel? How will you track which mode the PPU is in?

-

Sprite Handling: How will you efficiently find the 10 sprites for the current scanline from the 40 in OAM? Will you sort them by priority?

-

Timing Accuracy: Will you update the PPU every CPU cycle, or batch updates? How will you handle games that write to VRAM during rendering?

-

Window Layer: How will you handle the window layer (which doesn’t scroll)? How do you track when it becomes visible?

Thinking Exercise

Trace how the Nintendo logo scrolls down during the Game Boy boot sequence:

// The boot ROM does this in a loop:

// 1. Waits for V-blank

while (!(read_byte(0xFF44) == 144)) { } // Wait until LY == 144 (V-blank)

// 2. Increments SCY to scroll the logo down

uint8_t scroll_y = read_byte(0xFF42); // Read SCY

write_byte(0xFF42, scroll_y + 1); // Increment SCY

// Mental model exercise:

// - The boot ROM has loaded the Nintendo logo into VRAM as tiles

// - Tile map points to these tiles

// - Each frame, SCY increases by 1

// - What happens to the pixels the PPU draws for scanline 0?

// * Before: scanline 0 shows tile row at Y=0

// * After SCY=1: scanline 0 shows tile row at Y=1

// * The entire background "shifts" down visually

// Trace one scanline (say line 10) across multiple frames:

// Frame 0, SCY=0: PPU draws background row 10

// Frame 1, SCY=1: PPU draws background row 11 (10+1)

// Frame 2, SCY=2: PPU draws background row 12 (10+2)

// This creates the scrolling effect!

Now trace sprite rendering:

// During OAM search (mode 2), for scanline LY:

for (int sprite_idx = 0; sprite_idx < 40; sprite_idx++) {

uint8_t sprite_y = oam[sprite_idx * 4 + 0]; // Y position

uint8_t sprite_height = (lcdc & 0x04) ? 16 : 8;

// Is this sprite on the current scanline?

if (LY >= sprite_y - 16 && LY < sprite_y - 16 + sprite_height) {

// Add to list of sprites to render this scanline

// But only keep first 10!

}

}

// Why subtract 16 from sprite_y?

// Because sprite Y values are offset by 16 pixels

// (allows sprites to smoothly scroll on/off screen top)

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “Why does the Game Boy PPU have a 10-sprite-per-scanline limit?”

- It’s a hardware limitation - the PPU only has time to fetch and render 10 sprites during the pixel transfer phase of each scanline

- “Explain the 4 PPU modes and when each occurs during a scanline.”

- Mode 2 (OAM scan): Cycles 0-79, searching OAM for sprites on this line

- Mode 3 (Drawing): Cycles 80-252, rendering pixels to LCD

- Mode 0 (H-blank): Cycles 252-456, horizontal blanking

- Mode 1 (V-blank): Lines 144-153, vertical blanking period

- “How would you implement mid-scanline register changes (like changing SCX during rendering)?”

- Track the current dot/cycle within the scanline; when registers change, only affect pixels not yet drawn

- “What happens when a game writes to VRAM during mode 3 (pixel transfer)?”

- On real hardware, writes are blocked and the value doesn’t change. Emulators should ignore these writes for accuracy.

- “How does the window layer differ from the background layer?”

- Window doesn’t scroll (ignores SCX/SCY), has separate tile map, and once activated on a scanline, it covers the background for the rest of that line

- “Explain sprite priority when two sprites overlap.”

- Lower X coordinate has priority; if X coordinates are equal, the sprite with lower OAM index (earlier in the table) wins

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with background rendering only

// Render one scanline of background

void render_scanline_background(int ly) {

uint8_t scy = read_byte(0xFF42); // Scroll Y

uint8_t scx = read_byte(0xFF43); // Scroll X

// Which row of the 32x32 tile map are we rendering?

uint8_t tile_y = (ly + scy) / 8; // 8 pixels per tile

uint8_t pixel_y_in_tile = (ly + scy) % 8;

for (int x = 0; x < 160; x++) { // Screen width

uint8_t tile_x = (x + scx) / 8;

uint8_t pixel_x_in_tile = (x + scx) % 8;

// Get tile index from tile map

uint16_t tile_map_addr = get_tile_map_base();

uint8_t tile_index = vram[tile_map_addr + tile_y * 32 + tile_x];

// Get pixel color from tile data

uint8_t color = get_tile_pixel(tile_index, pixel_x_in_tile, pixel_y_in_tile);

// Draw pixel to framebuffer

framebuffer[ly * 160 + x] = palette[color];

}

}

Hint 2: Implement the PPU state machine

void ppu_step(int cycles) {

if (!lcd_enabled()) return;

ppu_dots += cycles;

switch (ppu_mode) {

case MODE_OAM_SCAN: // Mode 2

if (ppu_dots >= 80) {

ppu_dots -= 80;

ppu_mode = MODE_DRAWING;

find_sprites_for_scanline(ly); // Find the 10 sprites

}

break;

case MODE_DRAWING: // Mode 3

if (ppu_dots >= 172) { // Can vary 172-289

ppu_dots -= 172;

ppu_mode = MODE_HBLANK;

render_scanline(ly); // Actually draw this line

}

break;

case MODE_HBLANK: // Mode 0

if (ppu_dots >= 204) {

ppu_dots -= 204;

ly++;

if (ly == 144) {

ppu_mode = MODE_VBLANK;

request_vblank_interrupt();

} else {

ppu_mode = MODE_OAM_SCAN;

}

}

break;

case MODE_VBLANK: // Mode 1

if (ppu_dots >= 456) {

ppu_dots -= 456;

ly++;

if (ly == 154) {

ly = 0;

ppu_mode = MODE_OAM_SCAN;

}

}

break;

}

}

Hint 3: Decode Game Boy tile format

// Game Boy tiles are 8x8 pixels, 2 bits per pixel

// Each tile is 16 bytes: 2 bytes per row

// Bit 0 of color comes from byte 0, bit 1 from byte 1

uint8_t get_tile_pixel(uint8_t tile_index, int x, int y) {

uint16_t tile_addr = get_tile_data_base() + (tile_index * 16);

// Each row is 2 bytes

uint8_t byte1 = vram[tile_addr + y * 2 + 0];

uint8_t byte2 = vram[tile_addr + y * 2 + 1];

// Extract the bit for this X position (tiles go right to left in bits)

int bit_pos = 7 - x;

uint8_t color_bit_0 = (byte1 >> bit_pos) & 1;

uint8_t color_bit_1 = (byte2 >> bit_pos) & 1;

return (color_bit_1 << 1) | color_bit_0; // 2-bit color value (0-3)

}

Hint 4: Sprite rendering with priority

void render_scanline_sprites(int ly) {

Sprite sprites[10];

int sprite_count = find_sprites_for_scanline(ly, sprites);

// Sprites are rendered right to left (higher indices drawn first)

for (int i = sprite_count - 1; i >= 0; i--) {

Sprite* spr = &sprites[i];

int sprite_y = spr->y - 16; // Adjust for offset

int sprite_x = spr->x - 8;

int tile_line = ly - sprite_y;

// Handle Y flip

if (spr->flags & FLAG_Y_FLIP) {

tile_line = sprite_height - 1 - tile_line;

}

for (int x = 0; x < 8; x++) {

int screen_x = sprite_x + x;

if (screen_x < 0 || screen_x >= 160) continue;

int tile_x = x;

if (spr->flags & FLAG_X_FLIP) {

tile_x = 7 - x;

}

uint8_t color = get_tile_pixel(spr->tile_index, tile_x, tile_line);

if (color == 0) continue; // Transparent

// Check background priority

if (spr->flags & FLAG_BG_PRIORITY) {

// Only draw sprite if background is color 0

if (bg_buffer[ly * 160 + screen_x] != 0) continue;

}

framebuffer[ly * 160 + screen_x] = sprite_palette[color];

}

}

}

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter | |——-|——|———| | Tile-based rendering | Computer Graphics from Scratch by Gabriel Gambetta | Chapter 11 (2D Graphics) | | Scanline rendering | Game Boy Coding Adventure by Maximilien Dagois | Chapter 5 (PPU Implementation) | | Graphics hardware | Computer Organization and Design by Patterson & Hennessy | Chapter 6 (I/O and Graphics) | | Game Boy PPU details | Game Boy: Complete Technical Reference by gekkio | Full reference | | Sprite systems | Game Engine Architecture by Jason Gregory | Chapter 10 (Rendering) | | Pixel manipulation | C Programming: A Modern Approach by K.N. King | Chapter 20 (Bit manipulation) |

Project 6: Game Boy APU (Audio) Implementation

- File: RETRO_GAME_EMULATION_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, C++, Zig

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold” (Educational/Personal Brand)

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced (The Engineer)

- Knowledge Area: Audio Synthesis / APU Emulation

- Software or Tool: Game Boy APU / Sound Synthesis

- Main Book: “Designing Sound” by Andy Farnell

What you’ll build: The Audio Processing Unit for your Game Boy - two square wave channels, one wave channel, one noise channel, and the mixer.

Why it teaches emulation: Audio emulation teaches you about sound synthesis from first principles. You’ll generate waveforms mathematically, understand sampling rates, and deal with timing-sensitive operations. The Game Boy’s audio is simple enough to implement but complex enough to sound authentic.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Square wave generation (variable duty cycle: 12.5%, 25%, 50%, 75%) → maps to oscillator design

- Frequency sweeps (channel 1’s frequency sweep unit) → maps to modulation

- Length counters (automatic note cutoff) → maps to envelope generators

- Volume envelopes (attack/decay patterns) → maps to ADSR concepts

- Audio mixing (combining 4 channels to stereo) → maps to digital audio

Key Concepts:

- Sound Synthesis Basics: “Designing Sound” Chapter 5-8 - Andy Farnell

- APU Registers: Pan Docs - Audio

- Sample Rate Conversion: “Computer Music” Chapter 3 - Charles Dodge

- Digital Audio Fundamentals: Game Boy Sound Hardware

Difficulty: Advanced Time estimate: 1-2 weeks Prerequisites: Game Boy CPU + PPU complete

Real world outcome:

- Hear the iconic Game Boy boot chime

- Listen to game music (Tetris “Korobeiniki”, Pokemon themes)

- Sound effects play in sync with gameplay

$ ./gameboy roms/tetris.gb [GB] Audio initialized at 44100 Hz # *ding!* - the boot sound plays # Tetris music starts: da-da-da-da-da-da...

Learning milestones:

- Square wave plays at correct pitch → Basic oscillator works

- Volume envelopes work → Notes fade in/out correctly

- All 4 channels mix → Full audio system functional

- Music sounds accurate → You’ve nailed the Game Boy sound

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do you create sound from nothing but math? How do simple waveforms combine to create music?”

Sound seems magical, but it’s really just air pressure changes over time. The Game Boy generates these changes mathematically—square waves, noise, custom waveforms—and mixes them together. Understanding audio synthesis gives you deep appreciation for both music and signal processing.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Waveform Fundamentals

- What is a square wave? Why does duty cycle affect timbre?

- What frequencies correspond to musical notes? (A4 = 440 Hz)

- What is Nyquist frequency and why does sample rate matter?

- Book: “Designing Sound” Chapters 5-8 - Andy Farnell

- Envelope Generators