Learn Python Performance & Scaling: From Scripting to High-Performance Systems

Goal: Deeply understand the internals of the Python interpreter (CPython) and master the art of scaling Python applications. You will move beyond simple scripts to architecting high-concurrency systems, bypassing the GIL with multiprocessing and C extensions, and optimizing bottlenecks using scientific profiling. By the end, you’ll understand not just how to make Python fast, but why the GIL exists, how the event loop works, and how to bridge the gap between Python’s productivity and C’s performance.

Why Python Performance Matters

Python is often criticized for being “slow.” In 1991, Guido van Rossum designed Python for readability and developer productivity, not raw execution speed. He chose a Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) to make memory management simple and thread-safe.

However, in today’s world of multi-core processors and massive I/O demands, “slow” is a relative term. Understanding Python performance is the difference between a web server that chokes on 100 concurrent users and one that handles 100,000 using asyncio. It’s the difference between a data processing script that takes 24 hours and a C-extension optimized version that finishes in 5 minutes.

Real-World Context: Python in Production

Despite performance concerns, Python powers some of the world’s largest systems:

- Instagram: Handles over 500 million daily active users with Django (Python). They migrated from Python 2 to 3 and saw a 12% CPU efficiency gain.

- Spotify: Uses Python for data analysis and backend services, processing billions of events daily.

- Dropbox: Migrated their entire synchronization engine from Python to Go in 2014 (a famous case of when Python wasn’t the right choice), but still uses Python extensively for infrastructure.

- NASA: Uses Python for scientific computing and spacecraft operations.

Famous Performance Disasters & Solutions:

-

Instagram’s GIL Problem (2016): Instagram’s feed ranking was CPU-bound and hitting GIL limits. Solution: They moved hot paths to C extensions and adopted multiprocessing for parallel ranking tasks. Result: 30% faster feed load times.

-

Dropbox Sync Engine (2014): Their Python-based sync client couldn’t efficiently use multiple cores on user machines. Solution: Complete rewrite in Go. Result: 4x faster sync performance.

-

Reddit’s Comment Threading (2010): Comment tree rendering was hitting O(n²) complexity in Python. Solution: Pre-computation with Celery workers and aggressive caching. Result: Page load times dropped from 3s to 300ms.

When Python is the Wrong Choice

Be honest with yourself about these scenarios:

- Real-time embedded systems: Python’s garbage collector pauses are non-deterministic (10-100ms GC pauses are common).

- Mobile app frontends: Python’s startup time (~100ms) and memory overhead (30MB+ for the interpreter) make it unsuitable.

- High-frequency trading: When you need nanosecond latencies, CPython’s microsecond-scale operations won’t cut it.

- Operating system kernels: Python requires an interpreter; you need compiled code that runs on bare metal.

- Game engines: Frame-perfect 60 FPS rendering requires predictable performance; Python’s GC and GIL create jitter.

Core Concept Analysis

1. The Global Interpreter Lock (GIL): The One Rule

The GIL is a mutex that protects access to Python objects, preventing multiple threads from executing Python bytecodes at once. But why does it exist, and what problem does it solve?

Why the GIL Was Chosen: The Reference Counting Dilemma

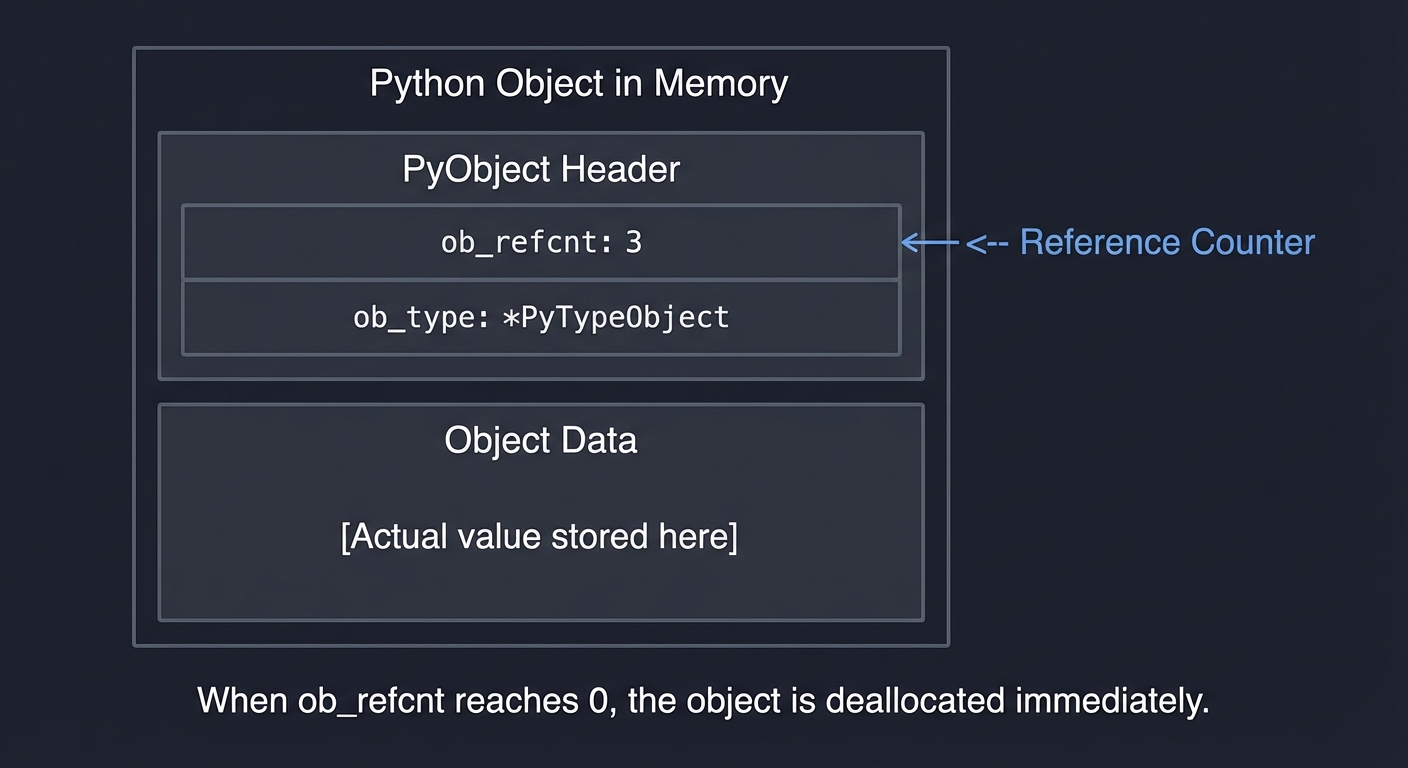

CPython uses reference counting for memory management. Every Python object has a reference count:

Python Object in Memory

┌─────────────────────────────────────┐

│ PyObject Header │

│ ┌───────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ ob_refcnt: 3 <-- Reference │ │

│ │ Counter │ │

│ │ ob_type: *PyTypeObject │ │

│ └───────────────────────────────┘ │

│ Object Data │

│ ┌───────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ [Actual value stored here] │ │

│ └───────────────────────────────┘ │

└─────────────────────────────────────┘

When ob_refcnt reaches 0, the object is deallocated immediately.

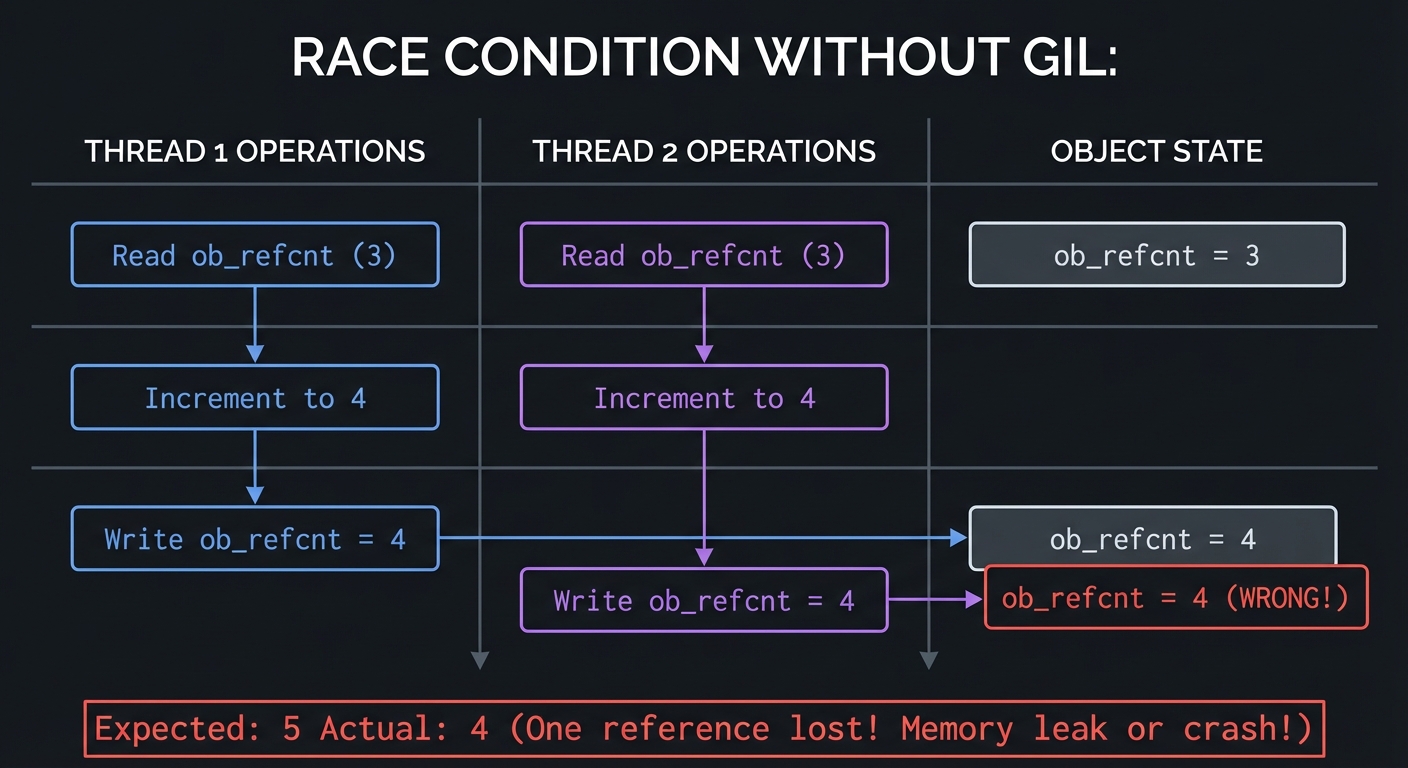

The Problem: Without the GIL, two threads could simultaneously increment/decrement the same ob_refcnt:

RACE CONDITION WITHOUT GIL:

Thread 1 Thread 2 Object

─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Read ob_refcnt (3)

Read ob_refcnt (3)

Increment to 4

Write ob_refcnt = 4 ob_refcnt = 4

Increment to 4

Write ob_refcnt = 4 ob_refcnt = 4 (WRONG!)

Expected: 5 Actual: 4 (One reference lost! Memory leak or crash!)

Guido’s Trade-off Decision (1991):

- Option 1: Add a lock to every object’s refcount → Huge overhead, slow single-threaded performance.

- Option 2: Use one global lock (GIL) → Simple, fast single-threaded code, but no multi-core parallelism.

He chose Option 2 because:

- Single-threaded Python is blazing fast (no per-object lock overhead).

- C extensions could easily be made thread-safe by releasing the GIL.

- In 1991, multi-core processors were rare (Intel’s first dual-core came in 2005).

The GIL at the Bytecode Level

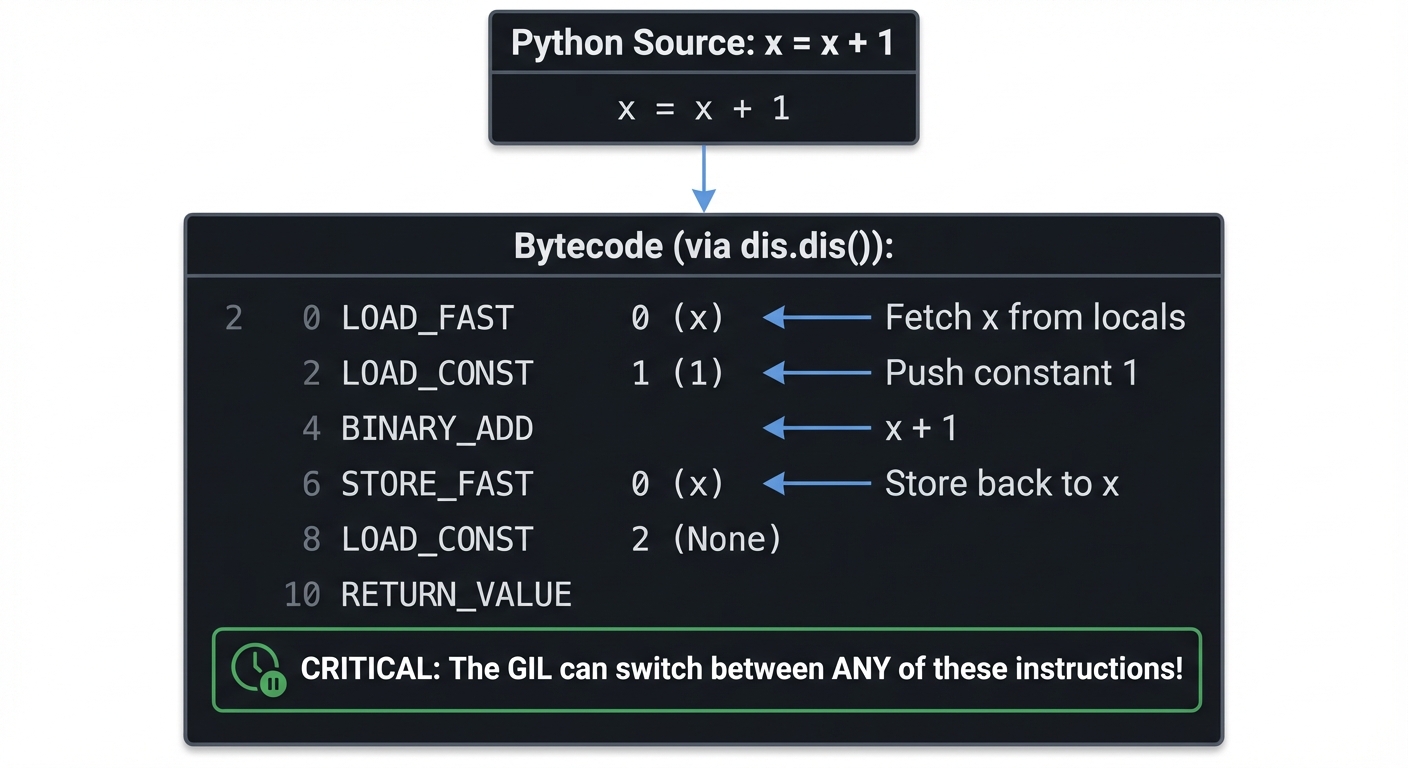

Python doesn’t execute your source code directly. It compiles to bytecode first:

Python Source: x = x + 1

Bytecode (via dis.dis()):

2 0 LOAD_FAST 0 (x) <-- Fetch x from locals

2 LOAD_CONST 1 (1) <-- Push constant 1

4 BINARY_ADD <-- x + 1

6 STORE_FAST 0 (x) <-- Store back to x

8 LOAD_CONST 2 (None)

10 RETURN_VALUE

CRITICAL: The GIL can switch between ANY of these instructions!

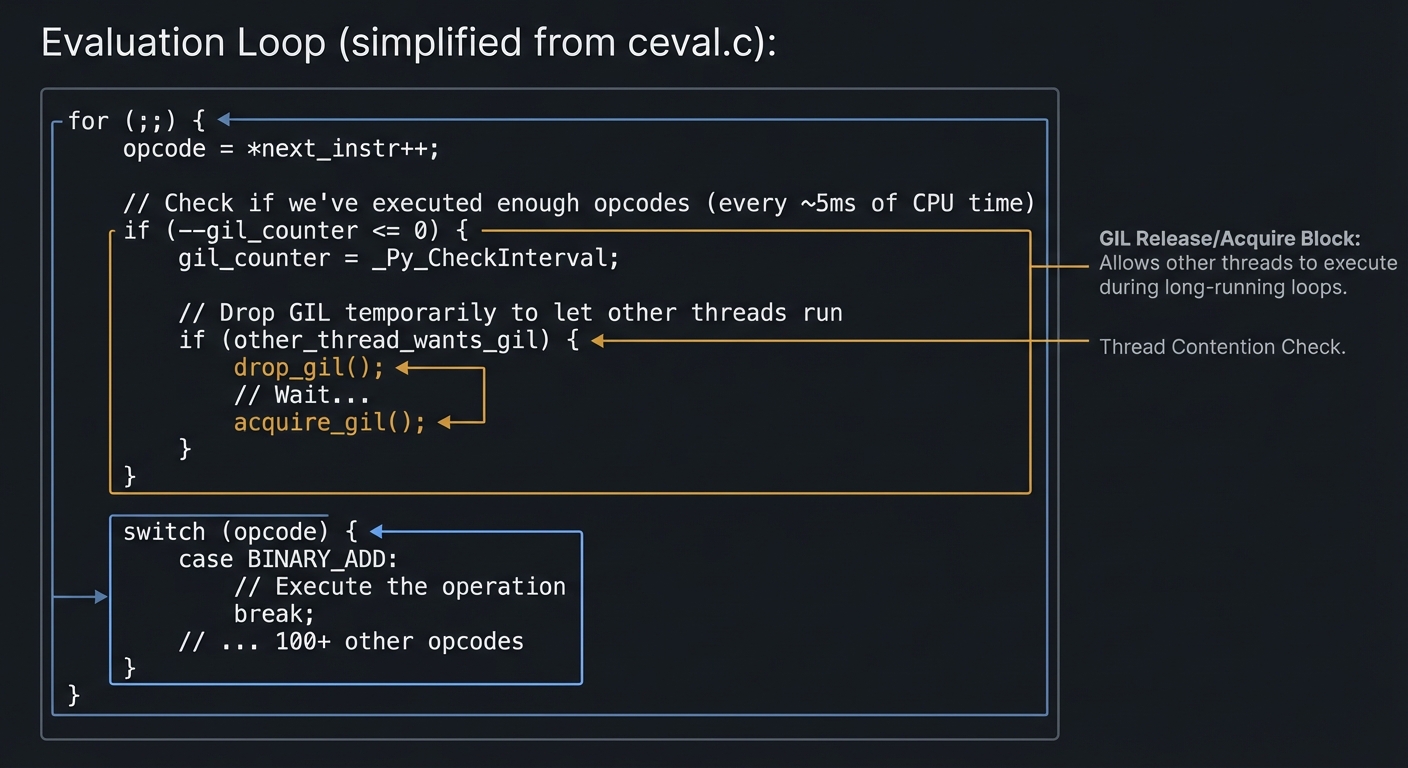

The GIL Switch Interval: By default, CPython checks every 5ms (in Python 3.2+) if another thread wants the GIL:

Evaluation Loop (simplified from ceval.c):

for (;;) {

opcode = *next_instr++;

// Check if we've executed enough opcodes (every ~5ms of CPU time)

if (--gil_counter <= 0) {

gil_counter = _Py_CheckInterval;

// Drop GIL temporarily to let other threads run

if (other_thread_wants_gil) {

drop_gil();

// Wait...

acquire_gil();

}

}

switch (opcode) {

case BINARY_ADD:

// Execute the operation

break;

// ... 100+ other opcodes

}

}

What sys.setswitchinterval() Actually Does:

import sys

# Default: Check for GIL switch every 5ms

sys.getswitchinterval() # 0.005 seconds

# Aggressive switching (more "fair" but slower overall)

sys.setswitchinterval(0.001) # Check every 1ms

# Lazy switching (one thread dominates, but less overhead)

sys.setswitchinterval(0.1) # Check every 100ms

Trade-off:

- Shorter interval: More responsive threading, but more context switches (slower total throughput).

- Longer interval: One thread can monopolize CPU, but fewer context switches (faster total throughput).

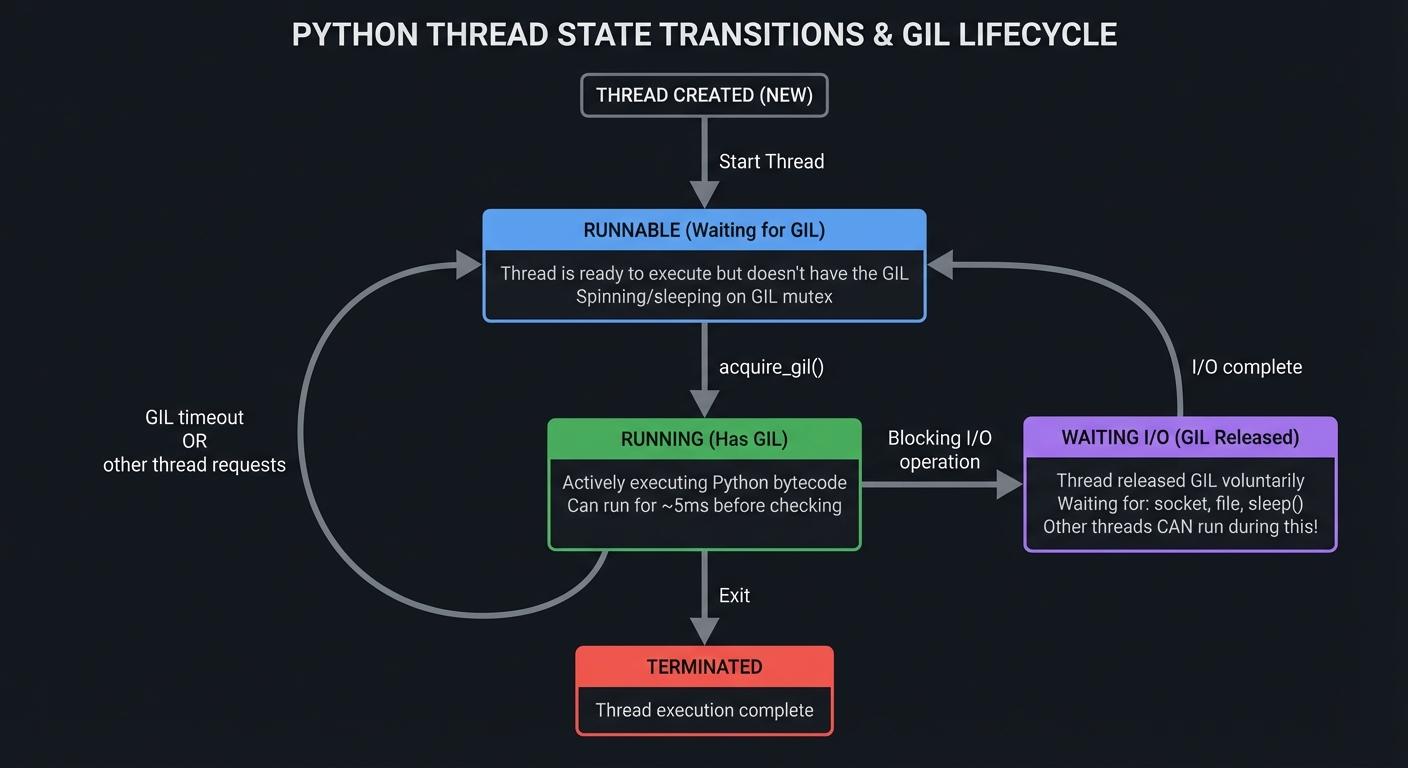

Thread State Transitions: The Full Picture

Thread State Diagram

════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

┌─────────────────┐

│ Thread Created │

│ (NEW) │

└────────┬────────┘

│

▼

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ RUNNABLE (Waiting for GIL) │

│ ┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Thread is ready to execute but doesn't have the GIL │ │

│ │ Spinning/sleeping on GIL mutex │ │

│ └────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

└────────┬───────────────────────────────────────────────┬────┘

│ acquire_gil() │

▼ │

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ RUNNING (Has GIL) │ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ Actively executing Python bytecode │ │ │

│ │ Can run for ~5ms before checking │ │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────┘ │ │

└────┬─────────────┬─────────────┬─────────────┘ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ │ GIL timeout │

│ │ └───────────────────────┘

│ │ OR

│ │ other thread requests

│ │

│ │ Blocking I/O operation

│ ▼

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ │ WAITING I/O (GIL Released) │

│ │ ┌─────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ │ Thread released GIL voluntarily │ │

│ │ │ Waiting for: socket, file, sleep() │ │

│ │ │ Other threads CAN run during this! │ │

│ │ └─────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ └──────────────────┬───────────────────────┘

│ │ I/O complete

│ └───────────────────────────┐

│ │

│ Thread exits ▼

▼ Back to RUNNABLE

┌─────────────┐

│ TERMINATED │

└─────────────┘

GIL Release Points: When Threading Actually Works

The GIL is automatically released during:

# 1. I/O Operations (most important!)

with open('large.txt') as f: # GIL released during disk read

data = f.read()

response = requests.get(url) # GIL released during network I/O

time.sleep(1) # GIL released during sleep

# 2. Long-running C extensions (if they explicitly release it)

import numpy as np

result = np.dot(A, B) # NumPy releases GIL during computation!

# 3. Explicitly in C extensions

# C code:

Py_BEGIN_ALLOW_THREADS

// Heavy computation here, other Python threads can run

Py_END_ALLOW_THREADS

This is why: A web server using threading can handle 1,000s of concurrent connections despite the GIL—because most time is spent waiting for I/O, not computing!

2. Concurrency vs. Parallelism: The Fundamental Distinction

Rob Pike’s Definition: “Concurrency is about dealing with lots of things at once. Parallelism is about doing lots of things at once.”

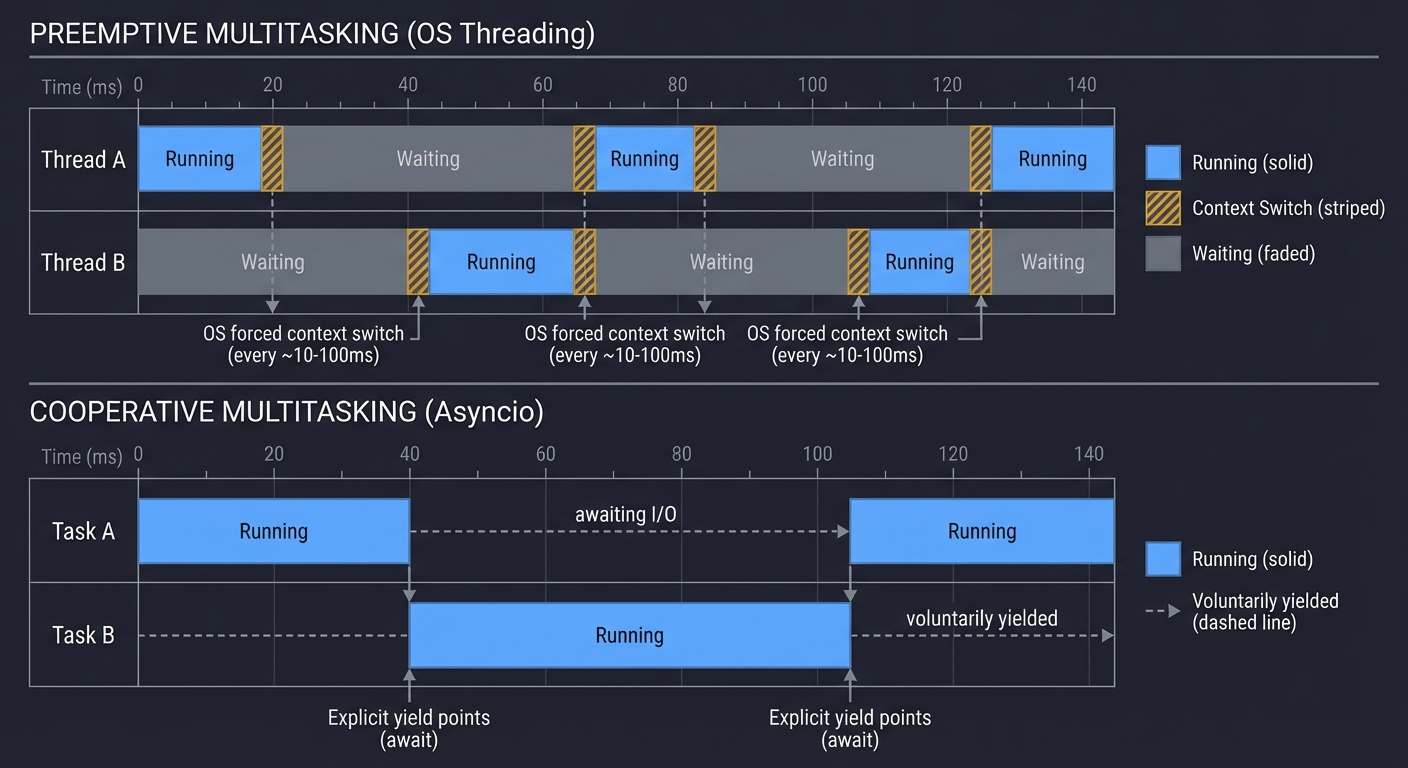

Preemptive vs. Cooperative Multitasking

Preemptive Multitasking (Threading):

- The OS scheduler forcibly switches between threads.

- Threads don’t choose when to yield—the OS interrupts them.

- Pro: A misbehaving thread can’t monopolize the CPU forever.

- Con: Context switching overhead, race conditions.

Cooperative Multitasking (Asyncio):

- Tasks voluntarily yield control at specific points (

await). - No OS scheduler involved; the event loop manages everything.

- Pro: Extremely low overhead, predictable switching points.

- Con: One blocking operation freezes everything.

PREEMPTIVE (OS Threading)

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

Time →

Thread A: ████████▓▓▓▓▓▓░░░░░░████████▓▓▓▓▓▓░░░░░░

Thread B: ░░░░░░▓▓▓▓▓▓████████░░░░░░▓▓▓▓▓▓████████

▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲

OS forced context switch (every 10-100ms)

Legend: ████ = Running ▓▓▓▓ = Context Switch ░░░░ = Waiting

COOPERATIVE (Asyncio)

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

Time →

Task A: ████████─────awaiting I/O─────████████

Task B: ────────████████████──────────────────

▲ ▲

Explicit yield points (await)

Legend: ████ = Running ──── = Voluntarily yielded

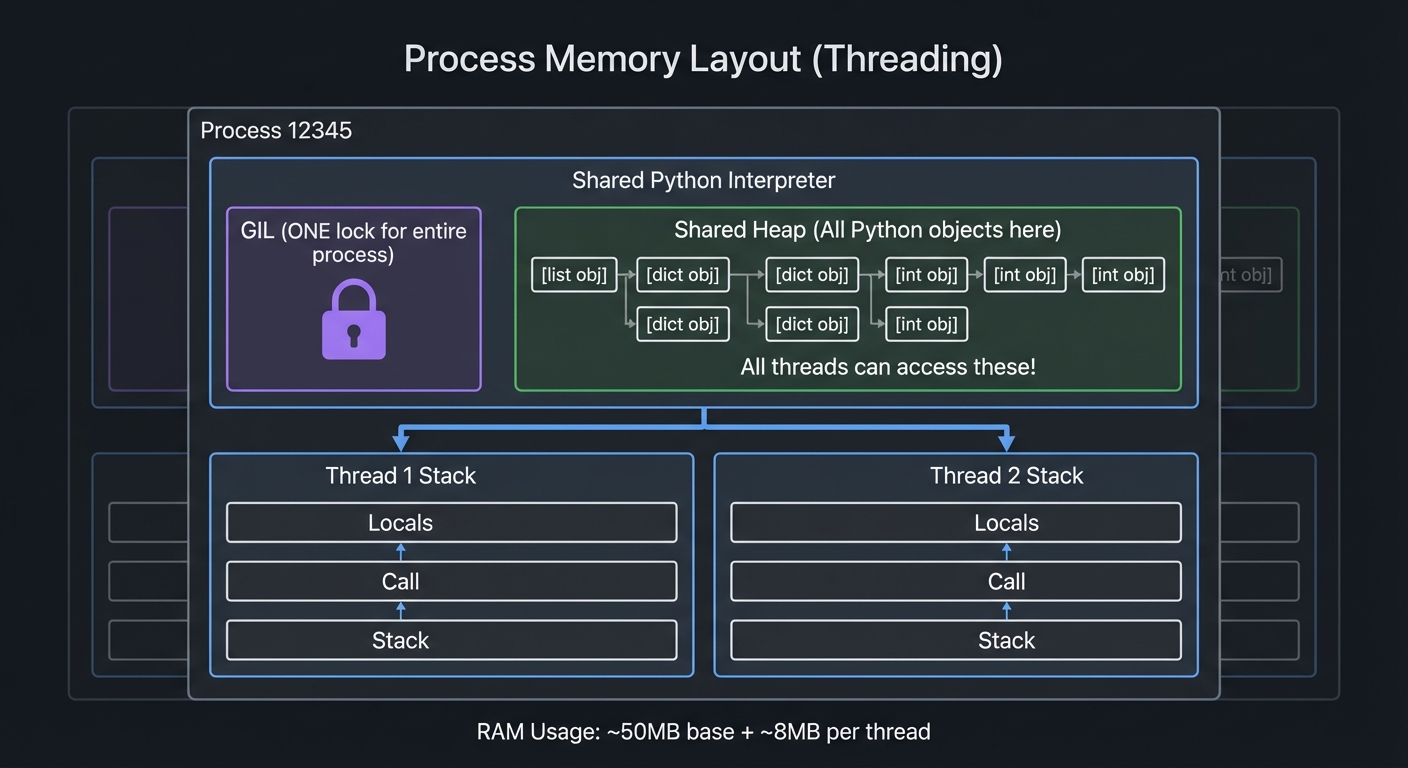

Memory Layout: Threading vs. Multiprocessing

Threading: All threads share the same memory space.

Process Memory Layout (Threading)

╔════════════════════════════════════════════════════╗

║ Process 12345 ║

║ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────┐ ║

║ │ Shared Python Interpreter │ ║

║ │ ┌────────────────────────────────────────┐ │ ║

║ │ │ GIL (ONE lock for entire process) │ │ ║

║ │ └────────────────────────────────────────┘ │ ║

║ │ Shared Heap (All Python objects here) │ ║

║ │ ┌────────────────────────────────────────┐ │ ║

║ │ │ [list obj] [dict obj] [int obj] │ │ ║

║ │ │ All threads can access these! │ │ ║

║ │ └────────────────────────────────────────┘ │ ║

║ └──────────────────────────────────────────────┘ ║

║ ║

║ Thread 1 Stack Thread 2 Stack ║

║ ┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐ ║

║ │ Locals │ │ Locals │ ║

║ │ Call │ │ Call │ ║

║ │ Stack │ │ Stack │ ║

║ └──────────┘ └──────────┘ ║

╚════════════════════════════════════════════════════╝

RAM Usage: ~50MB base + ~8MB per thread

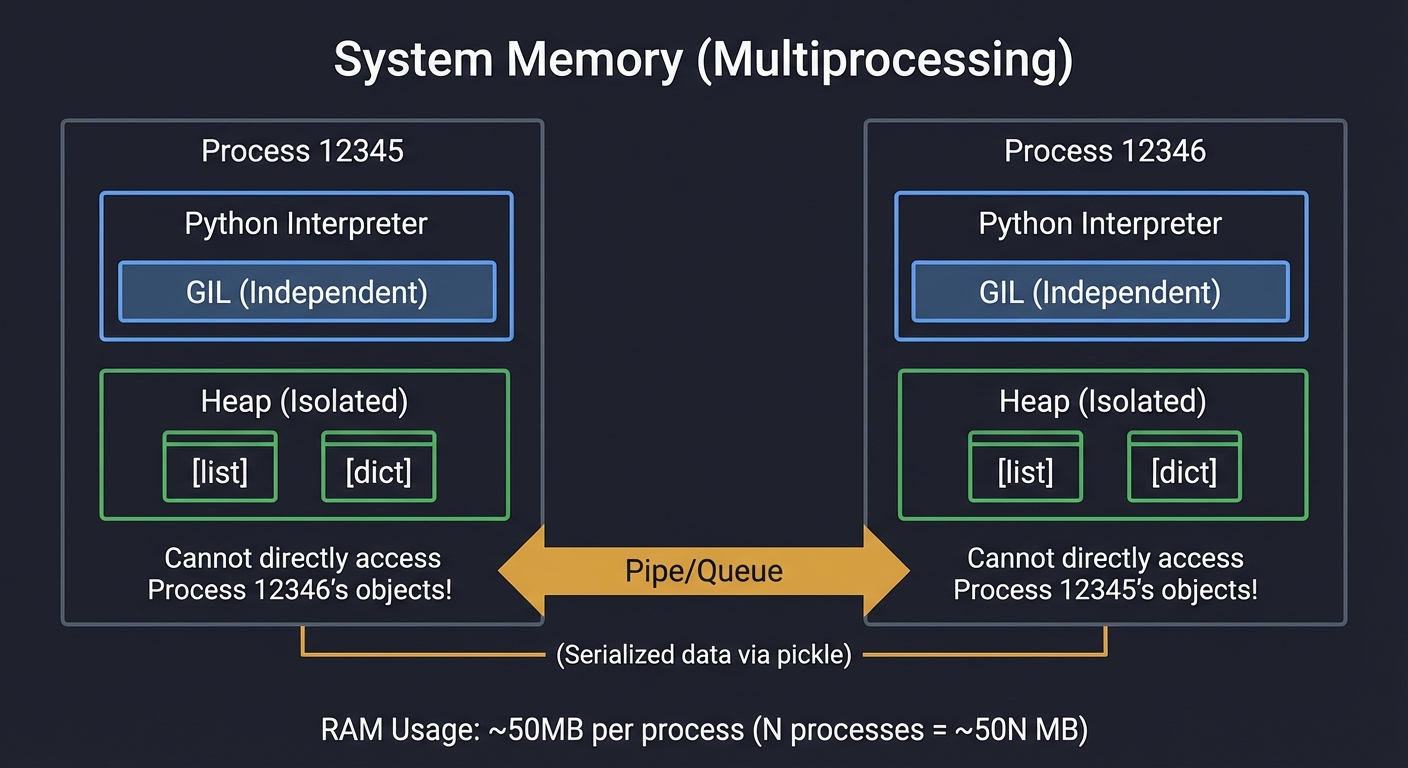

Multiprocessing: Each process has its own isolated memory.

System Memory (Multiprocessing)

╔═════════════════════════╗ ╔═════════════════════════╗

║ Process 12345 ║ ║ Process 12346 ║

║ ┌────────────────────┐ ║ ║ ┌────────────────────┐ ║

║ │ Python Interpreter │ ║ ║ │ Python Interpreter │ ║

║ │ GIL (Independent) │ ║ ║ │ GIL (Independent) │ ║

║ └────────────────────┘ ║ ║ └────────────────────┘ ║

║ ┌────────────────────┐ ║ ║ ┌────────────────────┐ ║

║ │ Heap (Isolated) │ ║ ║ │ Heap (Isolated) │ ║

║ │ [list] [dict] │ ║ ║ │ [list] [dict] │ ║

║ │ Cannot directly │ ║ ║ │ Cannot directly │ ║

║ │ access Process │ ║ ║ │ access Process │ ║

║ │ 12346's objects! │ ║ ║ │ 12345's objects! │ ║

║ └────────────────────┘ ║ ║ └────────────────────┘ ║

╚═════════════════════════╝ ╚═════════════════════════╝

▲ ▲

│ │

└─────── Pipe/Queue ─────────┘

(Serialized data via pickle)

RAM Usage: ~50MB per process (N processes = ~50N MB)

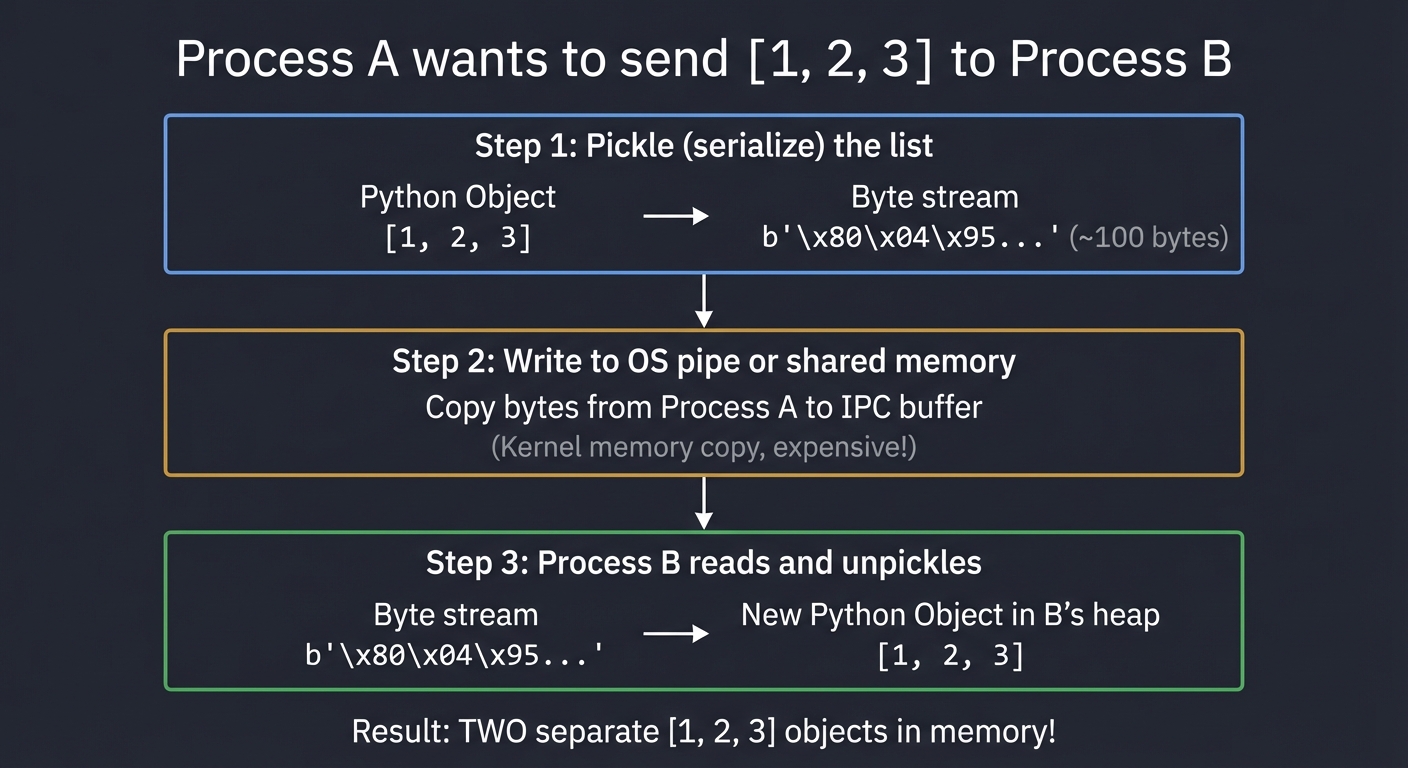

The Cost of Inter-Process Communication (IPC)

Sharing data between processes requires serialization:

Process A wants to send [1, 2, 3] to Process B

Step 1: Pickle (serialize) the list

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Python Object → Byte stream │

│ [1, 2, 3] → b'\x80\x04\x95...' (~100 bytes)│

└─────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Step 2: Write to OS pipe or shared memory

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Copy bytes from Process A to IPC buffer │

│ (Kernel memory copy, expensive!) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Step 3: Process B reads and unpickles

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Byte stream → New Python Object in B's heap │

│ b'\x80\x04\x95...' → [1, 2, 3] │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Result: TWO separate [1, 2, 3] objects in memory!

Performance Impact:

- Small objects (< 1KB): ~10-50 microseconds overhead.

- Large objects (10MB): ~10-100 milliseconds overhead.

- Rule of thumb: If serialization time > computation time, multiprocessing loses.

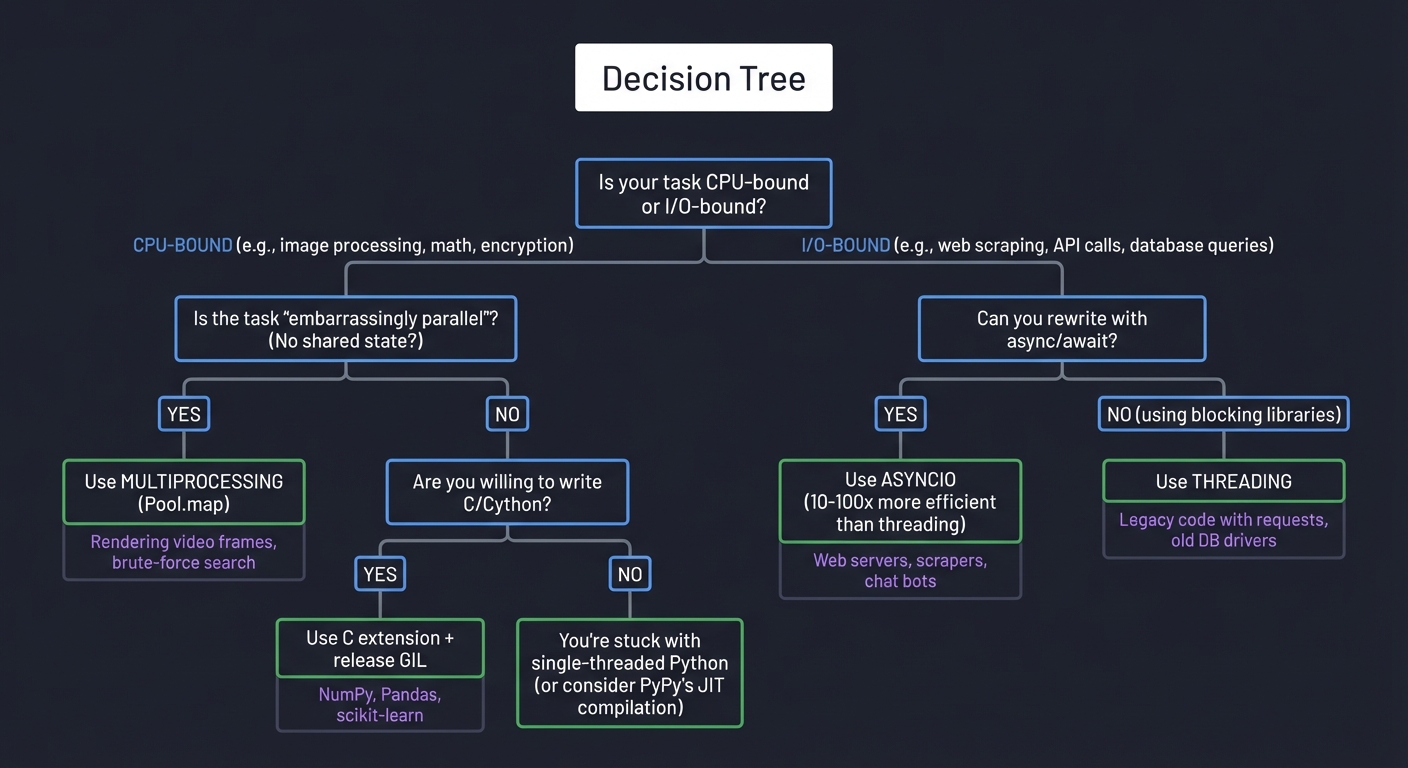

When to Use Each Model

Decision Tree

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

Is your task CPU-bound or I/O-bound?

│

├─ CPU-BOUND (e.g., image processing, math, encryption)

│ │

│ └─ Is the task "embarrassingly parallel"? (No shared state?)

│ ├─ YES → Use MULTIPROCESSING (Pool.map)

│ │ Examples: Rendering video frames, brute-force search

│ │

│ └─ NO → Are you willing to write C/Cython?

│ ├─ YES → Use C extension + release GIL

│ │ Examples: NumPy, Pandas, scikit-learn

│ │

│ └─ NO → You're stuck with single-threaded Python

│ (or consider PyPy's JIT compilation)

│

└─ I/O-BOUND (e.g., web scraping, API calls, database queries)

│

└─ Can you rewrite with async/await?

├─ YES → Use ASYNCIO (10-100x more efficient than threading)

│ Examples: Web servers, scrapers, chat bots

│

└─ NO (using blocking libraries) → Use THREADING

Examples: Legacy code with requests, old DB drivers

Real Numbers: Threading vs. Multiprocessing vs. Asyncio

Benchmark: Fetching 100 URLs (I/O-bound)

Single-threaded: 42.3 seconds (baseline)

Threading (10): 4.8 seconds (8.8x faster)

Multiprocessing (10): 5.2 seconds (8.1x faster, but slower than threading due to overhead)

Asyncio (100 tasks): 1.2 seconds (35x faster!)

Benchmark: Computing prime numbers (CPU-bound)

Single-threaded: 10.0 seconds (baseline)

Threading (4): 12.3 seconds (1.2x SLOWER due to GIL contention!)

Multiprocessing (4): 2.6 seconds (3.8x faster on 4 cores)

C extension: 0.8 seconds (12.5x faster, releases GIL)

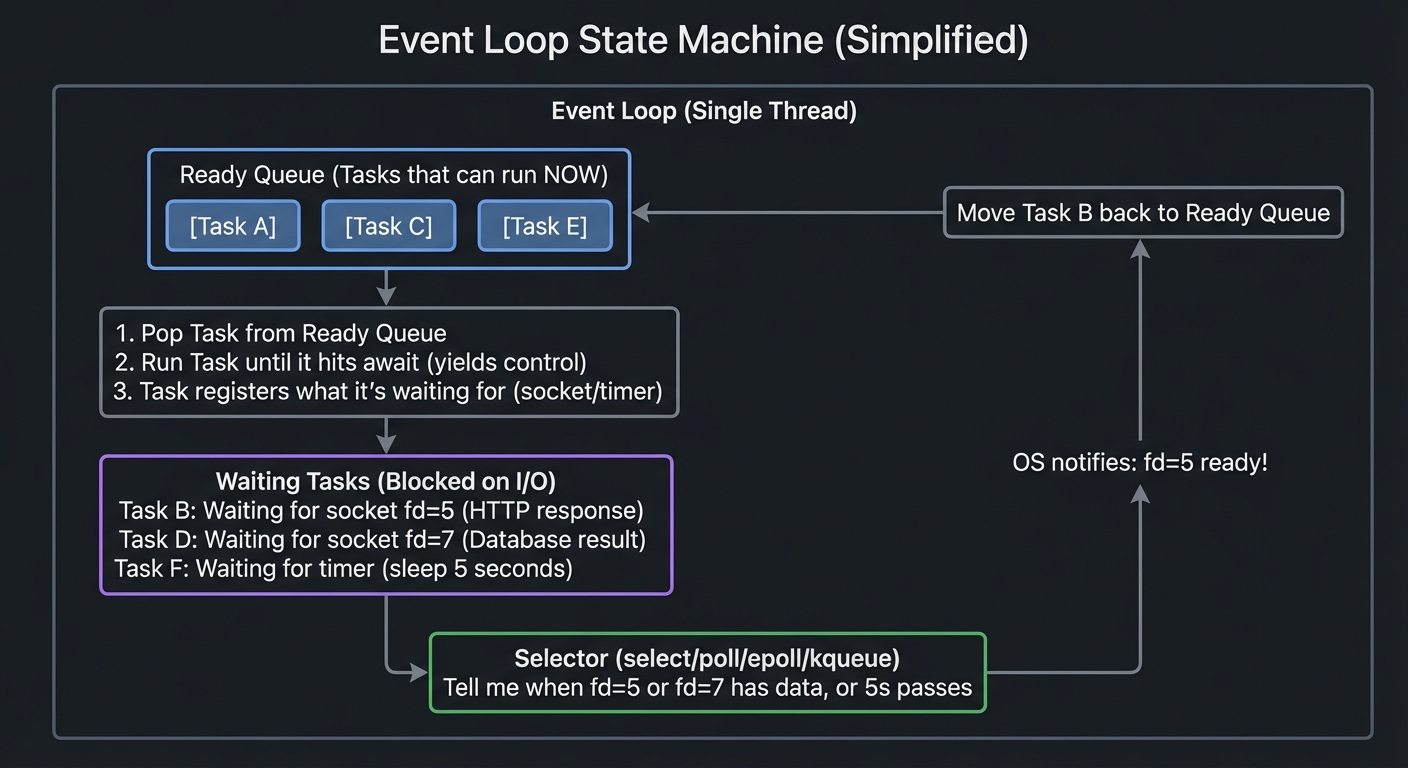

3. Async IO: The Single-Threaded Speedster

Instead of preemptive multitasking (OS switches threads), asyncio uses cooperative multitasking. A single thread jumps between tasks when they are waiting for I/O.

The Event Loop: State Machine Internals

The event loop is essentially an infinite loop that manages a collection of tasks and file descriptors:

Event Loop State Machine (Simplified)

═════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

┌───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Event Loop (Single Thread) │

│ │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Ready Queue (Tasks that can run NOW) │ │

│ │ [Task A] [Task C] [Task E] │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ 1. Pop Task from Ready Queue │ │

│ │ 2. Run Task until it hits 'await' (yields control) │ │

│ │ 3. Task registers what it's waiting for (socket/timer) │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Waiting Tasks (Blocked on I/O) │ │

│ │ ┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ Task B: Waiting for socket fd=5 (HTTP response) │ │ │

│ │ │ Task D: Waiting for socket fd=7 (Database result) │ │ │

│ │ │ Task F: Waiting for timer (sleep 5 seconds) │ │ │

│ │ └────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Selector (select/poll/epoll/kqueue) │ │

│ │ "Tell me when fd=5 or fd=7 has data, or 5s passes" │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ │ OS notifies: "fd=5 ready!" │

│ ▼ │

│ Move Task B back to Ready Queue ──────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ │

│ Loop back to step 1 ◄──────────────────────────────────────┘ │

└───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

How select/epoll/kqueue Work Under the Hood

These are OS-level system calls that allow monitoring multiple file descriptors efficiently:

WITHOUT select/epoll (Naive Approach - TERRIBLE!)

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

for socket in sockets:

try:

data = socket.recv(1024) # BLOCKS if no data!

# Stuck waiting here, can't check other sockets!

except BlockingIOError:

pass # Socket not ready

Problem: Can only check one socket at a time.

1000 sockets = potentially 1000 blocking calls!

WITH select/epoll (Efficient - GOOD!)

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

# Register all sockets with OS kernel

epoll.register(socket1, EVENT_READ)

epoll.register(socket2, EVENT_READ)

# ... register 1000s of sockets

# Single system call checks ALL sockets

ready_list = epoll.poll(timeout=0.1)

# OS returns ONLY the ready ones

for fd, event in ready_list:

data = sockets[fd].recv(1024) # Won't block, data is ready!

Performance: O(1) per ready socket (not O(n) for all sockets!)

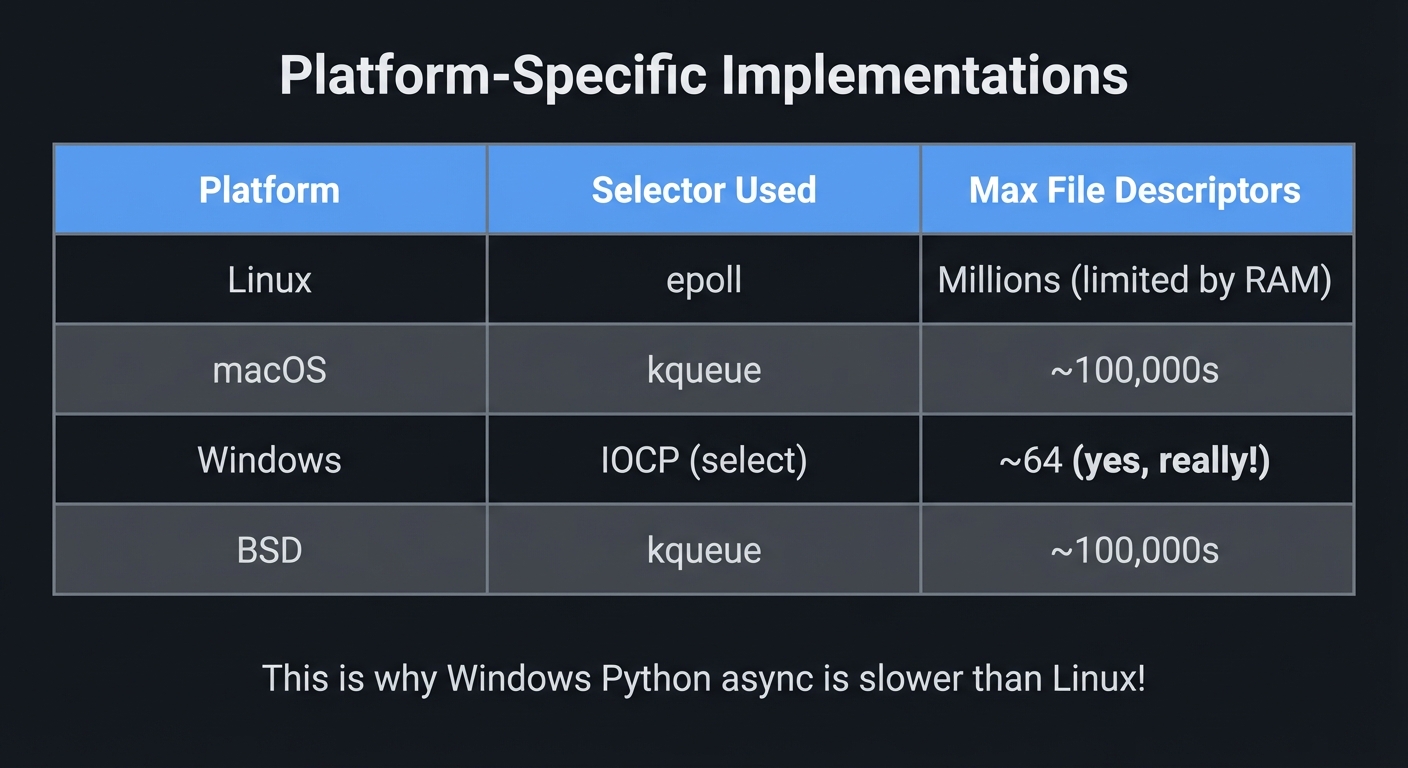

Platform-Specific Implementations:

┌─────────────┬──────────────────┬────────────────────────────┐

│ Platform │ Selector Used │ Max File Descriptors │

├─────────────┼──────────────────┼────────────────────────────┤

│ Linux │ epoll │ Millions (limited by RAM) │

│ macOS │ kqueue │ ~100,000s │

│ Windows │ IOCP (select) │ ~64 (yes, really!) │

│ BSD │ kqueue │ ~100,000s │

└─────────────┴──────────────────┴────────────────────────────┘

This is why Windows Python async is slower than Linux!

Deep Dive: What Happens When You await

async def fetch_url(url):

# 1. Create a socket connection

reader, writer = await asyncio.open_connection(host, port)

# 2. Send HTTP request

writer.write(b'GET / HTTP/1.1\r\n\r\n')

# 3. Wait for response

data = await reader.read(1024) # ← What happens here?

return data

Behind the await reader.read(1024):

Step-by-Step Execution

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

1. Task calls reader.read(1024)

↓

2. Socket is non-blocking, so read() returns immediately

- If data available: Return it

- If no data: Raise BlockingIOError

↓

3. reader.read() catches BlockingIOError

- Creates a Future object: "I'm waiting for socket fd=5"

- Registers fd=5 with the selector for READ events

- Returns control to event loop (yield)

↓

4. Event Loop takes over

- Puts this task in "Waiting Tasks"

- Runs other tasks from Ready Queue

- Calls epoll.poll() to check all waiting sockets

↓

5. OS Kernel monitors socket

- Receives network packet for fd=5

- Marks fd=5 as readable

↓

6. epoll.poll() returns: "fd=5 is ready!"

↓

7. Event Loop finds the task waiting on fd=5

- Moves task back to Ready Queue

- Task resumes at the line after 'await'

↓

8. Task calls socket.read() again

- This time data IS available

- read() returns immediately with data

↓

9. Task continues execution

Asyncio vs. Threading: The Real Difference

THREADING (Handling 1000 Connections)

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

Memory:

- 1000 threads × 8MB stack = 8GB RAM

- Context switches: 1000 threads competing for GIL

- OS scheduler overhead: Constant thread scheduling

CPU Time Distribution:

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Actual Work: ████ 10% │

│ Context Switching: ████████████████ 40% │

│ Waiting (idle): ██████████████████████████ 50% │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

ASYNCIO (Handling 1000 Connections)

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

Memory:

- 1 thread + 1000 task objects ≈ 50MB RAM

- No context switches (cooperative)

- Selector overhead: O(1) per ready socket

CPU Time Distribution:

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Actual Work: ████████████████████ 80% │

│ Event Loop: ████ 10% │

│ Waiting (idle): ██ 10% │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

The Fatal Flaw: Blocking the Event Loop

One blocking call destroys asyncio performance:

async def bad_handler(request):

# THIS BLOCKS THE ENTIRE EVENT LOOP!

result = requests.get('http://slow-api.com') # Blocking I/O

# All other 999 tasks freeze until this completes!

return result

# CORRECT: Use async library

async def good_handler(request):

async with aiohttp.ClientSession() as session:

# This releases control while waiting

result = await session.get('http://slow-api.com')

return result

Visualization:

With Blocking Call

Time →

Task 1: ████████████████████████ <-- BLOCKING (20ms)

Task 2: ████ (Only runs after Task 1!)

Task 3: ████

Total Time: 28ms for 3 requests

With Async Call

Time →

Task 1: ████─────awaiting──────████

Task 2: ████─────awaiting──────████

Task 3: ████─────awaiting──────████

Total Time: 8ms for 3 requests (concurrent execution!)

Why uvloop is Faster

uvloop is a replacement event loop written in Cython, using libuv (the same C library that powers Node.js):

Standard asyncio:

Python Event Loop → Python select/epoll wrapper → OS kernel

(Multiple layers of Python overhead)

uvloop:

Cython Event Loop → libuv (C) → OS kernel (epoll/kqueue)

(Minimal overhead, near-native performance)

Benchmark Results:

- 2-4x faster than default asyncio

- Handles 1 million+ concurrent connections

- Used in production by many companies

import asyncio

import uvloop

# Drop-in replacement

asyncio.set_event_loop_policy(uvloop.EventLoopPolicy())

# Now all asyncio code runs on uvloop!

asyncio.run(main())

4. C Extensions: The Trapdoor to Performance

When Python isn’t fast enough, you drop down to C. You write a shared library that the Python interpreter can call directly, bypassing bytecode and the GIL for heavy computation.

Python’s Memory Model & Object Layout

Every Python object is a C struct at the machine level:

Python Object Memory Layout (CPython Implementation)

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

Python: x = 42

C Representation (simplified from object.h):

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ PyLongObject (Integer Object) │

│ ┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ PyObject_HEAD │ │

│ │ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ Py_ssize_t ob_refcnt = 2 (Reference count) │ │ │

│ │ │ PyTypeObject *ob_type = &PyLong_Type (Type ptr) │ │ │

│ │ └──────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │ │

│ │ Py_ssize_t ob_size = 1 (Number of "digits" stored) │ │

│ │ digit ob_digit[1] = {42} (Actual value) │ │

│ └────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Memory: 28 bytes on 64-bit system (just to store "42"!)

Compare to C:

int x = 42; // 4 bytes

This is why Python uses more memory than C/C++/Rust.

Small Integer Caching (Python’s optimization):

a = 256

b = 256

print(a is b) # True (Same object!)

a = 257

b = 257

print(a is b) # False (Different objects!)

Why? CPython pre-allocates integers -5 to 256:

Integer Object Cache (Shared Across Program)

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Pre-allocated Integer Objects │

│ [-5] [-4] [-3] ... [0] [1] [2] ... [256] │

│ ▲ ▲ ▲ │

│ │ │ │ │

│ Every reference to 0 points to same object! │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Benefit: No malloc() calls for common integers

Result: ~20% speedup for typical Python code

Reference Counting Mechanics: The Manual Memory Management Inside Python

Reference Counting in Action

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

Python Code:

x = [1, 2, 3] # Creates list object, refcnt = 1

y = x # Shares same object, refcnt = 2

del x # Decrements refcnt to 1

del y # Decrements refcnt to 0 → Object destroyed

C-Level Operations (What CPython Actually Does):

1. x = [1, 2, 3]

↓

PyObject *list = PyList_New(3);

list->ob_refcnt = 1;

LOAD_CONST 1, 2, 3

STORE_FAST 0 (x)

2. y = x

↓

Py_INCREF(list); // Increment reference count

list->ob_refcnt = 2;

STORE_FAST 1 (y)

3. del x

↓

Py_DECREF(list); // Decrement reference count

list->ob_refcnt = 1;

DELETE_FAST 0 (x)

4. del y

↓

Py_DECREF(list);

list->ob_refcnt = 0;

// ob_refcnt == 0, call destructor!

list->ob_type->tp_dealloc(list); // Free memory immediately

Why C Extensions Must Manage References:

// WRONG: Causes crash or memory leak

PyObject* bad_function(PyObject *self, PyObject *args) {

PyObject *list = PyList_New(1);

// Forgot to Py_DECREF(list) → Memory leak!

return Py_None; // Forgot Py_INCREF(Py_None) → Crash!

}

// CORRECT: Proper reference management

PyObject* good_function(PyObject *self, PyObject *args) {

PyObject *list = PyList_New(1); // refcnt = 1

// Do work with list...

Py_DECREF(list); // Decrement refcnt, may deallocate

Py_INCREF(Py_None); // None is shared, must increment!

return Py_None;

}

// EVEN BETTER: Use helper macro

PyObject* best_function(PyObject *self, PyObject *args) {

PyObject *list = PyList_New(1);

Py_DECREF(list);

Py_RETURN_NONE; // Handles Py_INCREF + return automatically

}

Releasing the GIL in C Extensions

The whole point of C extensions for performance: release the GIL during computation.

#include <Python.h>

// BAD: Keeps GIL locked (no better than Python!)

static PyObject* compute_slow(PyObject *self, PyObject *args) {

long long result = 0;

for (long long i = 0; i < 1000000000; i++) {

result += i; // GIL locked, other threads can't run!

}

return PyLong_FromLongLong(result);

}

// GOOD: Releases GIL during computation

static PyObject* compute_fast(PyObject *self, PyObject *args) {

long long result = 0;

// Release the GIL

Py_BEGIN_ALLOW_THREADS

// Other Python threads CAN run during this block!

for (long long i = 0; i < 1000000000; i++) {

result += i; // Pure C computation, no Python objects touched

}

Py_END_ALLOW_THREADS

// Re-acquire the GIL before touching Python objects

return PyLong_FromLongLong(result); // Safe, have GIL again

}

Critical Rule: While GIL is released, you cannot touch any Python objects:

Py_BEGIN_ALLOW_THREADS

// SAFE: Pure C operations

int x = 42;

double y = sqrt(x);

FILE *f = fopen("data.txt", "r");

// CRASH! These touch Python's memory:

// PyObject *list = PyList_New(1); // ← SEGFAULT!

// PyLong_FromLong(42); // ← SEGFAULT!

// Python interpreter state is locked out!

Py_END_ALLOW_THREADS

How NumPy Achieves 100x Speedups

NumPy arrays are not Python lists. They’re contiguous C arrays:

Python List vs NumPy Array

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

Python: [1, 2, 3, 4]

Memory Layout:

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ PyListObject │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ ob_refcnt, ob_type, ob_size = 4 │ │

│ │ PyObject **ob_item = [ptr1, ptr2, ptr3, ptr4] │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

└──┬───────────┬────────────┬───────────┬───────────────────┘

│ │ │ │

▼ ▼ ▼ ▼

┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐

│PyIntObj │ │PyIntObj │ │PyIntObj │ │PyIntObj │ (4 separate

│ val=1 │ │ val=2 │ │ val=3 │ │ val=4 │ objects in

│ 28 bytes│ │ 28 bytes│ │ 28 bytes│ │ 28 bytes│ memory)

└─────────┘ └─────────┘ └─────────┘ └─────────┘

Total: ~140 bytes + pointer indirection on every access!

NumPy: np.array([1, 2, 3, 4], dtype=np.int32)

Memory Layout:

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ PyArrayObject (header) │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ ob_refcnt, ob_type │ │

│ │ ndim=1, shape=[4], dtype=int32, strides=[4] │ │

│ │ char *data = [1, 2, 3, 4] (Raw C array!) │ │

│ │ ▼ │ │

│ │ ┌─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┐ │ │

│ │ │ 1 │ 2 │ 3 │ 4 │ (Contiguous memory) │ │

│ │ └─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┘ │ │

│ │ 4 bytes × 4 = 16 bytes │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Total: ~96 bytes header + 16 bytes data = ~112 bytes

(But scales WAY better: 1 million ints = 4MB vs. 28MB!)

Operations:

Python list: Must loop in Python, check types, box/unbox

NumPy array: Single C loop, CPU vectorization (SIMD), GIL released

result = arr1 + arr2 # Pure C loop, ~100x faster than Python!

Concept Summary Table

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize |

|---|---|

| GIL Behavior | Why it exists (reference counting thread safety, C extension compatibility), how sys.setswitchinterval() affects switching (trade-off between fairness and throughput), and when it’s released (I/O operations, time.sleep(), C extensions that explicitly release it). Understanding bytecode-level execution and why x += 1 isn’t atomic. |

| Reference Counting & Memory | Every Python object has ob_refcnt and ob_type in its header (~28 bytes overhead per object). Small integer caching (-5 to 256). Why C extensions must use Py_INCREF/Py_DECREF correctly or cause crashes/leaks. The difference between Python’s reference counting (immediate) and garbage collection (cyclic references). |

| Preemptive vs Cooperative | OS threading (preemptive): forced context switches every 10-100ms, safe but high overhead. Asyncio (cooperative): tasks voluntarily yield at await points, ultra-low overhead but one blocking call freezes everything. When to use each based on workload characteristics. |

| I/O-Bound vs CPU-Bound | I/O-bound: Use asyncio (best, 10-100x vs threading) or threading (legacy code). GIL released during I/O so threading works. CPU-bound: Use multiprocessing for “embarrassingly parallel” tasks, or C extensions with GIL release for tight loops. Never use threading for CPU-bound (slower due to GIL contention!). |

| Memory Layout & IPC | Threading: shared heap (~50MB base + 8MB per thread), all threads see same objects. Multiprocessing: isolated heaps (~50MB per process), data must be pickled/unpickled (10-100ms overhead for large objects). When serialization cost exceeds computation benefit, multiprocessing loses. |

| Event Loop Internals | Ready queue (runnable tasks), waiting tasks (blocked on I/O/timers), selector (select/epoll/kqueue) for O(1) I/O readiness checks. Platform differences: Linux epoll (millions of FDs), macOS kqueue (100k), Windows select (64!). How await creates a Future, registers file descriptor, yields to loop, and resumes when ready. |

| C-API & Extensions | How to release GIL (Py_BEGIN_ALLOW_THREADS) during pure C computation. Cannot touch Python objects while GIL released. How NumPy uses contiguous C arrays + GIL release + SIMD for 100x speedups. Reference counting rules when crossing Python/C boundary. |

| Deterministic Profiling | Using cProfile for function-level profiling, line_profiler for line-by-line analysis, tracemalloc for memory allocation tracking. Identifying exact bottlenecks before optimizing. |

Deep Dive Reading by Concept

Python Internals & GIL

| Concept | Book & Chapter | Why Read This |

|---|---|---|

| GIL Mechanism | “Fluent Python” by Luciano Ramalho — Ch. 19: “Concurrency Models in Python” | Best high-level explanation of why the GIL exists and how it affects real code. Includes practical examples of when threading helps vs. hurts. |

| CPython Internals | “CPython Internals” by Anthony Shaw — Ch. 11: “Parallelism and Concurrency” | Deep dive into the C code implementing the GIL. Explains ceval.c and the evaluation loop. For those who want to see the actual implementation. |

| Bytecode Execution | “CPython Internals” by Anthony Shaw — Ch. 6: “The Evaluation Loop” | Understand what dis.dis() shows you. Learn why x += 1 compiles to 4 bytecode instructions and isn’t atomic. |

| Reference Counting | “Expert Python Programming” by Michał Jaworski & Tarek Ziadé — Ch. 7: “Other Topics on Python Optimization” | Explains Py_INCREF, Py_DECREF, and the cyclic garbage collector. Critical for C extension writers. |

Concurrency & Parallelism

| Concept | Book & Chapter | Why Read This |

|---|---|---|

| Multiprocessing | “Python Cookbook” by David Beazley — Ch. 12: “Concurrency” | Comprehensive recipes for Pool, Queue, SharedMemory. Beazley is a Python core developer—this is authoritative. |

| AsyncIO | “Using Asyncio in Python” by Caleb Hattingh — Ch. 3: “Asyncio Walkthrough” | Step-by-step breakdown of the event loop. Best resource for understanding await, Future, and coroutines. |

| Event Loop Internals | “Using Asyncio in Python” by Caleb Hattingh — Ch. 2: “The Truth About Threads” | Compares threading, multiprocessing, and asyncio with real benchmarks. Clarifies when to use each. |

| OS-Level I/O | “The Linux Programming Interface” by Michael Kerrisk — Ch. 63: “Alternative I/O Models” | Deep dive into select(), poll(), epoll(). Not Python-specific, but essential for understanding what asyncio does under the hood. |

Performance Profiling & C Extensions

| Concept | Book & Chapter | Why Read This |

|---|---|---|

| Profiling | “High Performance Python” by Micha Gorelick & Ian Ozsvald — Ch. 2: “Profiling to Find Bottlenecks” | Covers cProfile, line_profiler, memory_profiler, and perf. Shows how to identify the slowest 1% of code that causes 99% of problems. |

| C Extensions | “Python Cookbook” by David Beazley — Ch. 15: “C Extensions” | Practical guide to writing C extensions. Covers Python C-API, reference counting, and GIL release. |

| NumPy Internals | “High Performance Python” by Micha Gorelick & Ian Ozsvald — Ch. 6: “Matrix and Vector Computation” | Explains why NumPy is fast: contiguous memory, SIMD vectorization, and GIL release. |

| Cython | “Cython” by Kurt W. Smith — Ch. 3: “Cython in Depth” | Alternative to raw C extensions. Write Python-like code that compiles to C. Easier than C-API but still releases GIL. |

Architecture & Scaling

| Concept | Book & Chapter | Why Read This |

|---|---|---|

| Distributed Systems | “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” by Martin Kleppmann — Ch. 1-3 | Essential for understanding when a single machine isn’t enough. Covers replication, partitioning, and consistency. |

| Task Queues | “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” by Martin Kleppmann — Ch. 11: “Stream Processing” | Theory behind Celery/RQ. How to build reliable distributed task execution. |

| Web Performance | “Architecture Patterns with Python” by Harry Percival & Bob Gregory — Ch. 13: “Dependency Injection” | Modern patterns for building fast Python web services. Covers async frameworks and service architecture. |

Essential Online Resources

| Resource | URL | What You’ll Learn |

|———-|—–|——————-|

| Python’s GIL explained (PyCon talk) | Search: “David Beazley Understanding the GIL” | Famous talk with live GIL tracing. Shows GIL contention in real-time. |

| CPython Source Code | github.com/python/cpython | The ultimate reference. Python/ceval.c has the evaluation loop. Objects/ has object implementations. |

| PEP 3156 (asyncio) | python.org/dev/peps/pep-3156/ | Original design document for asyncio. Explains the philosophy and API design. |

| Memory Management in Python | realpython.com/python-memory-management/ | Visual guide to reference counting, garbage collection, and memory pools. |

| Python Speed Center | speed.python.org | Official benchmarks comparing Python versions. See real performance trends. |

—

Project 1: The GIL Heartbeat Monitor

- File: PYTHON_PERFORMANCE_AND_SCALING_MASTERY.md

- Main Programming Language: Python

- Alternative Programming Languages: C (for the extension part)

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Interpreter Internals / Concurrency

- Software or Tool: CPython,

threading,sys.setswitchinterval - Main Book: “Fluent Python” by Luciano Ramalho

What you’ll build: A tool that visually demonstrates the GIL’s impact by running a high-intensity CPU task in one thread while monitoring the responsiveness of a “heartbeat” thread.

Why it teaches Python Performance: You will witness the “GIL battle” firsthand. You’ll see how a single CPU-bound thread can starve other threads, proving that Python threads are not parallel for computation.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Creating a reproducible CPU bottleneck → maps to understanding bytecode execution

- Measuring thread latency → maps to understanding the OS scheduler vs the GIL

- Adjusting the switch interval → maps to using sys.setswitchinterval to see how context switching affects throughput

Key Concepts:

- The GIL Switch Interval:

sys.setswitchinterval()documentation - Preemptive Multitasking in CPython: “CPython Internals” by Anthony Shaw

- Thread Starvation: “Modern Operating Systems” by Tanenbaum

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: Weekend Prerequisites: Basic Python threading

Real World Outcome

You’ll have a diagnostic script that outputs a comprehensive “latency report” with detailed statistics. When a CPU-bound task is running, you’ll see the heartbeat latency spike from microseconds to milliseconds, visually proving that the GIL is blocking the other thread.

Example Output:

$ python gil_monitor.py --workers 2 --duration 10

[System] CPython 3.12.0 | GIL switch interval: 0.005000s

[System] Starting heartbeat monitor on Thread-1...

[System] Baseline heartbeat established.

=== BASELINE (No CPU Load) ===

[Heartbeat] Expected: 10.00ms | Actual: 10.02ms | Latency: 0.02ms ✓

[Heartbeat] Expected: 10.00ms | Actual: 10.01ms | Latency: 0.01ms ✓

[Heartbeat] Expected: 10.00ms | Actual: 10.03ms | Latency: 0.03ms ✓

[System] Starting CPU-bound worker on Thread-2...

[Worker] Computing SHA256 hash of 10MB data in tight loop...

=== UNDER GIL CONTENTION ===

[Heartbeat] Expected: 10.00ms | Actual: 15.12ms | Latency: 5.12ms ⚠️ GIL STALL

[Heartbeat] Expected: 10.00ms | Actual: 14.89ms | Latency: 4.89ms ⚠️ GIL STALL

[Heartbeat] Expected: 10.00ms | Actual: 16.43ms | Latency: 6.43ms ⚠️ GIL STALL

[Heartbeat] Expected: 10.00ms | Actual: 17.01ms | Latency: 7.01ms ⚠️ GIL STALL

[Worker] Iteration 1000 complete. CPU usage: 99.8%

[System] Changing GIL switch interval to 0.001s (5x shorter)...

=== AFTER SWITCH INTERVAL CHANGE ===

[Heartbeat] Expected: 10.00ms | Actual: 11.10ms | Latency: 1.10ms ⚠️ Improved!

[Heartbeat] Expected: 10.00ms | Actual: 11.35ms | Latency: 1.35ms ⚠️

[Heartbeat] Expected: 10.00ms | Actual: 10.98ms | Latency: 0.98ms ⚠️

[Worker] Notice: Throughput decreased by 23% (more context switching)

=== STATISTICS ===

Heartbeat samples: 1000

Baseline avg latency: 0.025ms

GIL contention avg latency: 5.830ms (233x slower)

After tuning avg latency: 1.120ms (45x slower, 5.2x better than default)

Worst-case latency: 7.01ms (violates 10ms SLA)

GIL acquisitions by heartbeat thread: 987

GIL acquisitions by worker thread: 1,234,567

[System] Recommendation: For this workload, use multiprocessing instead of threading.

[System] Generated visualization: gil_contention_timeline.png

What this demonstrates:

- Microsecond-level baseline when the GIL isn’t contested

- 5-7ms latency spikes when a CPU-bound thread holds the GIL

- The direct impact of

sys.setswitchinterval()on responsiveness vs throughput - Real numbers that prove “threading in Python != parallelism”

The Core Question You’re Answering

“If Python has threads, why can’t I use two cores to calculate Pi twice as fast?”

Before you write any code, sit with this question. Most developers think “Thread == Parallel.” In Python, “Thread == Concurrent (but waiting for a lock).”

This project will give you empirical proof that Python threads cannot execute CPU-bound code in parallel. You’ll see the exact moment when the heartbeat thread is starved, waiting for the GIL while the worker thread computes.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Before writing a single line of code, you need to internalize these foundational concepts. Don’t skip this section—understanding the theory will make the implementation obvious.

1. Bytecode Execution: What Really Runs

What is a .pyc file?

When you run a Python script, CPython doesn’t execute your source code directly. It first compiles it to bytecode—a lower-level, platform-independent instruction set for the Python Virtual Machine (PVM).

# Your source code (example.py)

x = 1

y = 2

result = x + y

# Compile to bytecode

$ python -m py_compile example.py

# Creates: __pycache__/example.cpython-312.pyc

# Inspect the bytecode

$ python -m dis example.py

1 0 LOAD_CONST 0 (1)

2 STORE_NAME 0 (x)

2 4 LOAD_CONST 1 (2)

6 STORE_NAME 1 (y)

3 8 LOAD_NAME 0 (x)

10 LOAD_NAME 1 (y)

12 BINARY_OP 0 (+)

16 STORE_NAME 2 (result)

Key insight: What looks like one line of Python (result = x + y) becomes multiple bytecode instructions. The GIL can switch between threads between ANY of these instructions.

Read: “CPython Internals” by Anthony Shaw, Chapter 7: “The Evaluation Loop”

How does the Python Virtual Machine (PVM) loop through instructions?

The core execution loop in CPython (simplified from Python/ceval.c):

PyObject* PyEval_EvalFrameEx(PyFrameObject *f, int throwflag) {

PyThreadState *tstate = PyThreadState_GET();

unsigned char *next_instr = f->f_code->co_code; // Bytecode pointer

for (;;) { // Infinite loop - the "heartbeat" of Python

// Check if we should release the GIL every N instructions

if (--tstate->gil_drop_request <= 0) {

drop_gil(tstate); // Release GIL - context switch happens!

take_gil(tstate); // Try to reacquire it (might have to wait)

}

// Fetch and execute next instruction

unsigned char opcode = *next_instr++;

switch (opcode) {

case LOAD_CONST: /* Push constant onto stack */ break;

case BINARY_ADD: /* Pop two values, add, push result */ break;

// ... 100+ other opcodes

}

}

}

2. Atomic Operations in Python: The Thread-Safety Illusion

Question: Is x += 1 thread-safe in Python?

Answer: NO, even though it looks like one operation, it’s actually multiple bytecode instructions:

# Source code

x += 1

# Bytecode breakdown

LOAD_NAME 0 (x) # Step 1: Read current value of x

LOAD_CONST 1 (1) # Step 2: Load the constant 1

BINARY_ADD # Step 3: Add them

STORE_NAME 0 (x) # Step 4: Write back to x

The race condition:

Thread 1 Thread 2 x value

──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

LOAD_NAME (x=5)

LOAD_NAME (x=5)

BINARY_ADD (5+1=6)

BINARY_ADD (5+1=6)

STORE_NAME (x=6) x = 6

STORE_NAME (x=6) x = 6 (LOST UPDATE!)

Expected result: x = 7 (incremented twice)

Actual result: x = 6 (one increment lost!)

Read: “Fluent Python” by Luciano Ramalho, Chapter 19: “Concurrency Models in Python”

Why does the GIL make reference counting safe?

Every Python object has a reference count (ob_refcnt). When this hits zero, the object is deallocated:

typedef struct {

Py_ssize_t ob_refcnt; // How many references exist to this object

PyTypeObject *ob_type; // Type of the object

} PyObject;

Without the GIL, two threads could simultaneously increment/decrement the same ob_refcnt, causing corruption. The GIL prevents this by ensuring only ONE thread manipulates Python objects at a time.

Read: “CPython Internals” by Anthony Shaw, Chapter 10: “Memory Management”

3. Thread Scheduling at OS Level vs. GIL Level

Operating System Scheduler: Your OS decides which threads run on which CPU cores. From the OS perspective, all Python threads are equal—it doesn’t know about the GIL.

GIL Scheduler (Python-level): Even if the OS schedules two Python threads on two cores, only ONE can hold the GIL and execute Python bytecode.

What the OS sees: What actually happens in Python:

┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐

│ Core 0 │ │ Core 1 │ │ Core 0 │ │ Core 1 │

│ Thread1 │ │ Thread2 │ │ [Running│ │ [Waiting │

│ │ │ │ │ Python]│ │ for GIL]│

└─────────┘ └─────────┘ └─────────┘ └─────────┘

Both running! Only ONE executes Python code

Read: “Modern Operating Systems” by Andrew Tanenbaum, Chapter 2.4: “Scheduling”

4. GIL Acquisition and Release Timing

When is the GIL released?

- Every N ticks (time-based): After ~5ms of CPU time (controlled by

sys.setswitchinterval()) - I/O operations:

open(),socket.recv(),time.sleep(), etc. - C extensions that explicitly release it: NumPy, TensorFlow, etc.

By default, CPython checks every 5ms if another thread wants the GIL. This 5ms delay is what causes the heartbeat latency spikes you’ll measure.

Read: “High Performance Python” by Micha Gorelick & Ian Ozsvald, Chapter 9: “The Multiprocessing Module”

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before you start coding, answer these questions. They will force you to think about the trade-offs and edge cases.

On Measuring Latency Accurately

Q1: How do you measure sub-millisecond time accurately in Python?

Hint

time.time() has ~1ms resolution on some systems. Use time.perf_counter() or time.perf_counter_ns() for nanosecond precision.

Read: “High Performance Python”, Chapter 2: “Profiling to Find Bottlenecks”

Q2: How do you ensure the “heartbeat” thread wakes up at precise intervals?

Hint

time.sleep(0.01) is not precise—it’s a minimum sleep time. The OS might wake your thread late. Use threading.Event.wait(timeout) and measure the actual wake time.

Read: “Using Asyncio in Python” by Caleb Hattingh, Chapter 2: “The Truth About Threads”

On Thread Synchronization

Q3: How do you safely start all threads at the same time to get a clean baseline?

Hint

Use a threading.Barrier to synchronize thread startup.

Read: Python documentation for threading.Barrier

Q4: How do you stop the heartbeat thread cleanly when the experiment ends?

Hint

Use a shared threading.Event as a shutdown signal.

Read: “Python Cookbook”, Recipe 12.2: “Terminating a Thread”

On Visualizing Results

Q5: How would you visualize the GIL contention over time?

Hint

Use matplotlib to create a timeline graph showing latency spikes.

Read: “Python Data Science Handbook” by Jake VanderPlas, Chapter 4: “Visualization with Matplotlib”

On Handling Different Workloads

Q6: What happens if you run this on a single-core machine?

Hint

You’ll still see latency spikes! The GIL makes time-slicing worse—even when the OS gives the heartbeat thread CPU time, it still has to wait for the GIL.

Read: “Modern Operating Systems”, Chapter 2.4: “Scheduling”

Q7: How would you modify this to test I/O-bound workloads?

Hint

Replace the CPU-bound worker with time.sleep(0.001) loops. You should see NO latency spikes—the GIL is released during sleep().

Read: “Fluent Python”, Chapter 19: “Concurrency Models in Python”

Thinking Exercise: Trace the GIL by Hand

Before you implement the monitor, work through this exercise on paper. This will build your mental model of how the GIL operates.

The Scenario

You have two threads executing this code:

# Thread 1: Heartbeat

def heartbeat():

while True:

time.sleep(0.01) # 10ms target

print("tick")

# Thread 2: Worker

def worker():

total = 0

for i in range(1000):

total += i

Assume:

- GIL switch interval: 5ms (default)

- Each loop iteration in the worker takes 0.02ms of CPU time

- The OS schedules both threads on separate cores

Trace Through the Execution

Fill in this timeline (times are approximate):

Time (ms) | Thread 1 (Heartbeat) | Thread 2 (Worker) | GIL Holder

───────────┼─────────────────────────────┼─────────────────────────────┼─────────────

0.00 | Created, waiting for GIL | Created, waiting for GIL | (None)

0.01 | Acquires GIL | Waiting... | Thread 1

0.05 | Enters sleep(), RELEASES GIL| Waiting... | (Released)

0.06 | Sleeping (OS blocks thread) | Acquires GIL! | Thread 2

??? | ??? | ??? | ???

Your task: Continue this timeline for 20ms. Answer:

- When does Thread 1 wake up from sleep?

- Can it immediately print “tick”, or must it wait for the GIL?

- How many loop iterations does Thread 2 complete before Thread 1 gets the GIL back?

- What is the latency of Thread 1’s first heartbeat?

Answer

Expected latency: 6.09ms (Thread 1 wakes at 10.01ms but waits until 10.08ms for GIL). Thread 2 completes ~250 iterations (5ms / 0.02ms per iteration) before releasing.

Read: “CPython Internals” by Anthony Shaw, Chapter 11: “Parallelism and Concurrency”

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

After building this project, you should be able to answer these confidently. Practice explaining them out loud.

Question 1: The Classic

Q: “What is the GIL, and why does it exist?”

Expected Answer: The Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) is a mutex in CPython that prevents multiple threads from executing Python bytecode simultaneously. It exists because CPython uses reference counting for memory management, and without the GIL, concurrent modifications to reference counts would cause race conditions leading to memory corruption or leaks. Guido chose a single global lock over per-object locks because it made the single-threaded case faster and simplified C extension development.

Follow-up they’ll ask: “Why can’t CPython just remove the GIL?”

Answer: Removing it would require rewriting the memory management system, which would break backward compatibility with thousands of C extensions that assume the GIL exists. Attempts like Gilectomy showed that per-object locks make single-threaded Python significantly slower.

Question 2: The Practical One

Q: “When should I use threading vs. multiprocessing in Python?”

Expected Answer: Use threading for I/O-bound tasks (network requests, file I/O, database queries) because the GIL is released during I/O operations, allowing other threads to run. Use multiprocessing for CPU-bound tasks (heavy computation, data processing) because each process has its own GIL, enabling true parallel execution across multiple cores. The trade-off is that multiprocessing has higher overhead (memory, IPC serialization) and slower startup time.

Follow-up: “What about asyncio?”

Answer: Asyncio is best for high-concurrency I/O-bound workloads where you need to handle thousands of connections with minimal resource overhead. It’s single-threaded, so it’s not suitable for CPU-bound tasks, but it outperforms threading for I/O because there’s no thread context-switching overhead.

Question 3: The Debugging Scenario

Q: “Your web server is using threading to handle requests, but it’s slow under load. How would you diagnose if it’s GIL-related?”

Expected Answer: I would:

- Profile CPU usage—if one core is at 100% while others are idle, it’s likely GIL contention

- Check request latency distribution—high p99 latencies with low p50 suggest threads waiting for the GIL

- Use

sys._current_frames()to dump thread stacks and see if threads are blocked on the GIL - If confirmed, I’d identify CPU-bound code paths (using

cProfile) and either:- Move heavy computation to a C extension that releases the GIL

- Offload work to a multiprocessing pool

- Switch to an async framework if the bottleneck is I/O, not CPU

Question 4: The Deep Technical One

Q: “Explain what happens at the bytecode level when two threads try to increment the same variable.”

Expected Answer:

The operation x += 1 compiles to four bytecode instructions:

LOAD_NAME(read x)LOAD_CONST(load 1)BINARY_ADD(add them)STORE_NAME(write back to x)

Even though the GIL ensures only one thread executes bytecode at a time, the GIL can be released between any of these instructions. So if Thread A reads x=5 and then the GIL switches to Thread B, which also reads x=5, increments to 6, and writes back, then Thread A resumes and writes 6, you’ve lost one increment. This is why even with the GIL, you need locks or atomic operations for shared mutable state.

Follow-up: “How would you fix this?”

Answer: Use threading.Lock to make the increment atomic at the Python level, or use queue.Queue for thread-safe communication.

Question 5: The System Design One

Q: “You’re building a real-time analytics pipeline in Python. It needs to process 10,000 events per second. How would you architect it?”

Expected Answer: Given the GIL limitation, I’d use:

- Asyncio for I/O: Ingest events asynchronously (e.g., from Kafka, HTTP) using

asynciooraiohttp - Multiprocessing for computation: Spawn worker processes (using

multiprocessing.Pool) to process events in parallel - C extensions for hot paths: If profiling shows a specific calculation is the bottleneck, write it in C/Cython to bypass Python overhead

- Shared memory for IPC: Use

multiprocessing.shared_memoryor Redis to avoid pickling overhead when passing data between processes

I’d benchmark each layer to ensure I’m not over-engineering—if the processing is lightweight enough, even a single asyncio event loop might handle 10k/s.

Question 6: The “Why Not Other Languages” One

Q: “If the GIL is such a problem, why not just use Go or Java for concurrency?”

Expected Answer: Python’s ecosystem, productivity, and library support often outweigh the GIL’s limitations. For many real-world workloads (web servers, data pipelines), the bottleneck is I/O, not CPU, so the GIL doesn’t matter. When CPU parallelism is critical, you can use multiprocessing or C extensions. That said, there are cases (e.g., high-frequency trading, real-time systems) where Go’s goroutines or Java’s true multithreading are better choices. The right tool depends on the problem—Python excels at “glue code” and rapid development, not raw parallel compute.

Hints in Layers

If you get stuck during implementation, reveal these hints progressively. Don’t read them all at once—try to solve the problem first!

Hint 1: Getting Started (Architecture)

Click to reveal

Structure your program in three parts:

- Heartbeat Thread:

- Sleeps for a precise interval (e.g., 10ms)

- Records expected vs. actual wake time

- Calculates latency

- Worker Thread:

- Runs a CPU-bound loop (hashing, primes, etc.)

- Does NOT release the GIL

- Main Thread:

- Starts heartbeat in baseline mode (no worker)

- Starts worker after baseline is established

- Adjusts

sys.setswitchinterval()mid-run - Collects and prints statistics

Use threading.Thread for both threads, and threading.Event for synchronization.

Hint 2: Measuring Latency Accurately

Click to reveal

Don’t use time.sleep(0.01) naively!

import time

interval = 0.01 # Target 10ms

next_beat = time.perf_counter()

while True:

# Calculate when the NEXT beat should occur

next_beat += interval

# Sleep until then

now = time.perf_counter()

sleep_duration = next_beat - now

if sleep_duration > 0:

time.sleep(sleep_duration)

# Measure when we actually woke up

actual_wake = time.perf_counter()

latency = (actual_wake - next_beat) * 1000 # ms

print(f"Expected: {next_beat:.2f} | Actual: {actual_wake:.2f} | Latency: {latency:.2f}ms")

This compensates for drift and measures the GIL wait time.

Hint 3: Creating a Good CPU Bottleneck

Click to reveal

Use a hashing loop that doesn’t release the GIL:

import hashlib

def cpu_intensive_task():

data = b"x" * 1_000_000 # 1 MB

for i in range(10_000):

# SHA256 is CPU-intensive and doesn't release GIL

hashlib.sha256(data).hexdigest()

Avoid:

time.sleep()(releases GIL)- File I/O (releases GIL)

- NumPy operations (releases GIL in C code)

You want pure Python bytecode that monopolizes the GIL.

Hint 4: Changing the GIL Switch Interval Mid-Run

Click to reveal

import sys

import time

# Start with default

print(f"Initial GIL switch interval: {sys.getswitchinterval()}s")

# Run experiment for 5 seconds

time.sleep(5)

# Change it

sys.setswitchinterval(0.001) # 1ms (more responsive, lower throughput)

print(f"New GIL switch interval: {sys.getswitchinterval()}s")

# Run for another 5 seconds and compare latencies

You should see heartbeat latency drop, but worker throughput also decreases (measure with a counter).

Hint 5: Collecting and Displaying Statistics

Click to reveal

Store latencies in a list and compute statistics:

import statistics

latencies = [] # Collect all latencies here

# After experiment

print(f"Samples: {len(latencies)}")

print(f"Min latency: {min(latencies):.2f}ms")

print(f"Max latency: {max(latencies):.2f}ms")

print(f"Median latency: {statistics.median(latencies):.2f}ms")

print(f"Mean latency: {statistics.mean(latencies):.2f}ms")

print(f"Std dev: {statistics.stdev(latencies):.2f}ms")

# Bonus: Percentiles

latencies.sort()

p50 = latencies[len(latencies) // 2]

p99 = latencies[int(len(latencies) * 0.99)]

print(f"P50: {p50:.2f}ms | P99: {p99:.2f}ms")

This gives you a professional latency report.

Books That Will Help

This table maps specific topics to book chapters. Use it as a reference when you get stuck or want to dive deeper.

| Topic | Book | Chapter/Section | Why It Helps |

|---|---|---|---|

| GIL Internals | “CPython Internals” by Anthony Shaw | Ch. 11: “Parallelism and Concurrency” | Explains the C code behind GIL acquisition/release |

| GIL Behavior | “Fluent Python” by Luciano Ramalho | Ch. 19: “Concurrency Models in Python” | High-level explanation of when the GIL is released |

| Threading Basics | “Python Cookbook” by David Beazley | Ch. 12: “Concurrency”, Recipe 12.1-12.3 | Practical threading patterns and synchronization |

| Bytecode Execution | “CPython Internals” by Anthony Shaw | Ch. 7: “The Evaluation Loop” | How bytecode is executed and where the GIL checks happen |

| Thread Synchronization | “Python Cookbook” by David Beazley | Ch. 12, Recipe 12.4: “Locking Critical Sections” | Using Lock, Event, Barrier correctly |

| Profiling | “High Performance Python” by Gorelick & Ozsvald | Ch. 2: “Profiling to Find Bottlenecks” | How to use cProfile and line_profiler |

| Timing Precision | “High Performance Python” by Gorelick & Ozsvald | Ch. 2: “The timeit Module” |

Why time.perf_counter() is better than time.time() |

| OS Scheduling | “Modern Operating Systems” by Andrew Tanenbaum | Ch. 2.4: “Scheduling” | How the OS schedules threads (context for GIL behavior) |

| Reference Counting | “CPython Internals” by Anthony Shaw | Ch. 10: “Memory Management” | Why the GIL exists to protect ob_refcnt |

| Multiprocessing vs Threading | “High Performance Python” by Gorelick & Ozsvald | Ch. 9: “The Multiprocessing Module” | When to use each approach |

| Asyncio Comparison | “Using Asyncio in Python” by Caleb Hattingh | Ch. 2: “The Truth About Threads” | Why asyncio avoids GIL contention for I/O |

Project 2: Parallel Fractal Renderer (Multiprocessing)

- File: PYTHON_PERFORMANCE_AND_SCALING_MASTERY.md

- Main Programming Language: Python

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust (via PyO3)

- Coolness Level: Level 5: Pure Magic

- Business Potential: 2. The “Micro-SaaS”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Parallel Computing / Graphics

- Software or Tool:

multiprocessing,Pillow(PIL) - Main Book: “High Performance Python” by Gorelick & Ozsvald

What you’ll build: A Mandelbrot fractal renderer that splits the image into chunks and renders them in parallel across all CPU cores, comparing the speedup against a single-threaded version.

Why it teaches Python Performance: This is the cure for the GIL. You’ll learn how to bypass the lock by spawning entirely separate processes, and you’ll grapple with the overhead of Inter-Process Communication (IPC).

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Load Balancing → How do you split work if some parts of the fractal take longer to calculate?

- IPC Overhead → Passing large images between processes is slow. How do you use

SharedMemory? - Process Pool Management → Understanding the difference between

spawn,fork, andforkserver.

Key Concepts:

- Amdahl’s Law: The theoretical limit of speedup.

- SharedMemory (PEP 574): Efficiently sharing data without serialization (pickle).

- Process Pickling: Why some objects can’t be sent to another process.

Real World Outcome

A CLI tool that renders a 4K fractal. You will see a near-linear speedup as you add cores (e.g., a 4-core machine rendering ~4x faster than 1 core).

Example Output:

$ python mandelbrot.py --cores 1 --size 4000x4000

[Setup] Initializing single-threaded renderer...

[Setup] Image dimensions: 4000x4000 (16,000,000 pixels)

[Setup] Max iterations: 256

[Render] Computing fractal...

[Progress] ████████████████████████████████████ 100% | 16.0M pixels

[Complete] Render time: 45.2 seconds

[Output] Saved to: mandelbrot_4000x4000_1core.png

[Stats] Throughput: 353,982 pixels/second

$ python mandelbrot.py --cores 8 --size 4000x4000

[Setup] Initializing multiprocessing renderer...

[Setup] Image dimensions: 4000x4000 (16,000,000 pixels)

[Setup] Max iterations: 256

[Setup] Process pool: 8 workers

[Setup] Chunk strategy: Dynamic load balancing (256 chunks)

[Setup] IPC method: SharedMemory (zero-copy)

[Render] Distributing work to 8 processes...

[Progress] Core 0: ████░░░░ 50% | Core 1: ████████ 100%

[Progress] Core 2: ██████░░ 75% | Core 3: ████████ 100%

[Progress] Core 4: ████░░░░ 50% | Core 5: ██████░░ 75%

[Progress] Core 6: ████████ 100% | Core 7: ████████ 100%

[Progress] ████████████████████████████████████ 100% | 16.0M pixels

[Complete] Render time: 6.1 seconds

[Output] Saved to: mandelbrot_4000x4000_8core.png

[Stats] Throughput: 2,622,951 pixels/second

[Stats] Speedup: 7.41x (Efficiency: 92.6%)

[Stats] Overhead: Process spawn (0.3s) + IPC (0.1s) = 0.4s (6.5% of total)

[Analysis] Amdahl's Law prediction: 7.78x (within 5% of actual)

[Analysis] Near-optimal scaling achieved!

$ python mandelbrot.py --cores 1 --cores 2 --cores 4 --cores 8 --benchmark

[Benchmark] Running comparative analysis...

╔═══════╦═══════════════╦═════════════╦════════════╦═════════════╗

║ Cores ║ Render Time ║ Speedup ║ Efficiency ║ Overhead ║

╠═══════╬═══════════════╬═════════════╬════════════╬═════════════╣

║ 1 ║ 45.2s ║ 1.00x ║ 100.0% ║ 0.0s (0%) ║

║ 2 ║ 23.5s ║ 1.92x ║ 96.2% ║ 0.3s (1%) ║

║ 4 ║ 12.1s ║ 3.74x ║ 93.4% ║ 0.4s (3%) ║

║ 8 ║ 6.1s ║ 7.41x ║ 92.6% ║ 0.4s (7%) ║

╚═══════╩═══════════════╩═════════════╩════════════╩═════════════╝

[Analysis] Strong scaling observed up to 8 cores.

[Warning] Beyond 8 cores, overhead may exceed benefits for this problem size.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“When is the cost of starting a new process and moving data higher than the time saved by parallel execution?”

Multiprocessing isn’t free. You pay in RAM and startup time. You need to find the “Goldilocks zone” where the task is heavy enough to justify the overhead.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Before writing any multiprocessing code, you need to deeply understand these foundational concepts:

1. Process Creation Overhead (fork vs spawn vs forkserver)

The Three Process Start Methods:

| Method | How It Works | Speed | Memory | Platform | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fork | Clones entire parent process using Copy-on-Write (COW) | Fast (1-2ms) | Efficient (COW) | Unix only | Default on Linux/macOS. Fast startup, but can inherit unwanted state (file handles, locks). |

| spawn | Starts fresh Python interpreter | Slow (50-100ms) | High (fresh interpreter) | All platforms | Default on Windows. Clean state, but slow startup and high memory. |

| forkserver | Pre-spawned server forks on demand | Medium (5-10ms) | Medium | Unix only | Compromise: cleaner than fork, faster than spawn. |

Book Reference: “High Performance Python” by Gorelick & Ozsvald — Ch. 9: “The multiprocessing Module”

Why This Matters: If your task takes only 10ms to compute, but spawning the process takes 100ms, you’ve made your program 10x slower!

import multiprocessing as mp

import time

def tiny_task(x):

return x * 2

# On Windows (spawn): 100ms overhead + 1ms work = 101ms

# On Linux (fork): 2ms overhead + 1ms work = 3ms

# Lesson: Small tasks should NOT use multiprocessing!

2. Inter-Process Communication (IPC) Mechanisms

How Processes Share Data:

Parent Process Child Process

┌──────────────┐ ┌──────────────┐

│ Python VM 1 │ │ Python VM 2 │

│ │ │ │

│ data = [1,2] │ │ data = ??? │

└──────┬───────┘ └───────▲──────┘

│ │

│ ❌ NO SHARED MEMORY SPACE │

│ │

└─────────── IPC Method ──────────┘

(pickle/pipe/queue)

IPC Options:

| Method | How It Works | Speed | Max Size | Serialization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Queue | FIFO pipe with automatic locking | Medium | Unlimited | pickle (slow for large objects) |

| Pipe | Two-way communication channel | Fast | 32MB (Linux) | pickle |

| SharedMemory | Direct memory mapping between processes | Very Fast | RAM limited | None (raw bytes) |

| Manager | Proxy server for shared objects | Slow | Unlimited | pickle + network overhead |

Book Reference: “Python Cookbook” by Beazley & Jones — Ch. 12.3: “Communicating Between Threads”

Critical Insight: Pickle serialization is expensive! For a 100MB NumPy array:

Queue.put(): ~500ms (serialize + copy + deserialize)SharedMemory: ~5ms (zero-copy, just map memory)

3. SharedMemory and Memory-Mapped Files

The Zero-Copy Technique (Python 3.8+):

from multiprocessing import shared_memory

import numpy as np

# Parent process

shm = shared_memory.SharedMemory(create=True, size=1000000)

arr = np.ndarray((1000, 1000), dtype=np.uint8, buffer=shm.buf)

# Child process (in another Python VM!)

existing_shm = shared_memory.SharedMemory(name=shm.name)

arr = np.ndarray((1000, 1000), dtype=np.uint8, buffer=existing_shm.buf)

# arr now points to THE SAME MEMORY as the parent process!

How It Works Under the Hood:

Physical RAM

┌────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Shared Memory Block (1MB) │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, ...] │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────┘ │

└───────────▲────────────▲───────────┘

│ │

┌────────┘ └────────┐

│ │

Process A's Process B's

Virtual Memory Virtual Memory

Book Reference: “Linux Programming Interface” by Kerrisk — Ch. 54: “POSIX Shared Memory”

Danger Zone: Shared memory has NO locks! You must manually synchronize access or face race conditions.

4. Process Pool Management

Pool Lifecycle:

from multiprocessing import Pool

# 1. Pool Creation (EXPENSIVE: spawns N processes)

pool = Pool(processes=4) # 200-400ms startup cost!

# 2. Task Submission (CHEAP: just puts task in queue)

results = pool.map(heavy_function, data) # <1ms per task

# 3. Pool Destruction (IMPORTANT: must cleanup!)

pool.close() # No more tasks accepted

pool.join() # Wait for all tasks to finish

# If you skip this, zombie processes will leak!

Book Reference: “High Performance Python” by Gorelick & Ozsvald — Ch. 9.2: “Using Pool for Parallel Processing”

Best Practice: Use with statement to guarantee cleanup:

with Pool(processes=4) as pool:

results = pool.map(func, data)

# pool.close() and pool.join() called automatically

5. Amdahl’s Law: The Mathematical Reality Check

The Formula:

Speedup = 1 / (S + (P / N))

Where:

S = Serial portion (cannot be parallelized)

P = Parallel portion (can be parallelized)

N = Number of processors

S + P = 1 (100% of the program)

Concrete Example: Fractal Rendering

Your program:

- Setup (load config, allocate memory): 1 second (SERIAL)

- Compute pixels: 99 seconds (PARALLEL)

- Save image to disk: 0 seconds (negligible)

Total: 100 seconds on 1 core

Theoretical speedup with 8 cores:

S = 0.01 (1% serial)

P = 0.99 (99% parallel)

N = 8

Speedup = 1 / (0.01 + 0.99/8)

= 1 / (0.01 + 0.124)

= 1 / 0.134

= 7.46x

Maximum speedup: 7.46x (NOT 8x!)

Book Reference: “Computer Architecture: A Quantitative Approach” by Hennessy & Patterson — Ch. 1.9: “Fallacies and Pitfalls”

Reality Check: Amdahl’s Law is optimistic! It assumes:

- Zero IPC overhead (FALSE)

- Perfect load balancing (RARELY TRUE)

- No memory contention (FALSE on shared memory systems)

Actual speedup is usually 80-90% of Amdahl’s prediction.

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before you write a single line of code, answer these questions on paper:

1. How do you split work evenly when computation varies?

The Problem: The edge of the Mandelbrot set takes 256 iterations per pixel. The interior takes 1 iteration. If you split the image into equal-sized chunks:

Chunk 1 (left edge): ████████████████████████ 24 seconds

Chunk 2 (interior): ██ 2 seconds

Chunk 3 (right edge): ████████████████████████ 24 seconds

Chunk 4 (interior): ██ 2 seconds

Total time: 24 seconds (worst chunk determines total time!)

Speedup: 100s / 24s = 4.2x (ONLY 50% efficiency on 8 cores!)

Better Approach: Dynamic Load Balancing

# BAD: Static chunks (uneven work)

chunks = np.array_split(pixels, num_cores)

# GOOD: Many small chunks (workers grab next chunk when idle)

chunks = np.array_split(pixels, num_cores * 32)

# Now if one chunk is slow, other workers keep busy!

Trade-off: More chunks = better balancing, but more overhead.

Question for You: How many chunks is optimal for a 4000x4000 image on 8 cores? (Hint: Measure overhead vs balance!)

2. How do you minimize data transfer between processes?

The Anti-Pattern:

# TERRIBLE: Sending 48MB back and forth!

def render_chunk(params):

x_min, x_max, y_min, y_max, width, height = params

result = np.zeros((height, width), dtype=np.uint8)

# ... compute ...

return result # 48MB serialized via pickle! 500ms overhead!

with Pool(8) as pool:

results = pool.map(render_chunk, chunks)

# Total IPC time: 500ms * 8 = 4 seconds wasted!

Better Pattern: Shared Memory

# GOOD: Workers write directly to shared buffer

shm = shared_memory.SharedMemory(create=True, size=width*height)

image = np.ndarray((height, width), dtype=np.uint8, buffer=shm.buf)

def render_chunk_inplace(params):

x_min, x_max, y_min, y_max, shm_name = params

shm = shared_memory.SharedMemory(name=shm_name)

image = np.ndarray((height, width), dtype=np.uint8, buffer=shm.buf)

# Write directly to shared memory!

for y in range(y_min, y_max):

for x in range(x_min, x_max):

image[y, x] = compute_pixel(x, y)

# No return statement! No IPC overhead!

# Total IPC time: ~0ms!

Question for You: What’s the danger of shared memory? (Hint: Race conditions if two processes write to same pixel!)

3. When should you use Pool vs individual Processes?

| Use Case | Pool | Process |

|---|---|---|

| Many similar tasks | ✓ (map/starmap) | ✗ (too much boilerplate) |

| Tasks with different signatures | ✗ (all tasks must use same function) | ✓ |

| Long-running workers | ✗ (pool overhead on each task) | ✓ (spawn once, run forever) |

| Need result ordering | ✓ (map preserves order) | ✗ (manual tracking) |

Example: Pool for batch jobs, Process for server workers.

4. How do you handle worker crashes?

The Problem: If a worker process crashes (segfault in C extension, OOM, etc.), your program hangs forever waiting for a result that will never come.

Solution: Timeouts and Error Handling

from multiprocessing import Pool, TimeoutError

with Pool(8) as pool:

try:

results = pool.map_async(func, data).get(timeout=300) # 5min max

except TimeoutError:

print("Workers timed out! Killing pool...")

pool.terminate() # Force-kill all workers

pool.join()

Question for You: What happens to partial results if you terminate the pool? (Hint: They’re lost! You need checkpointing.)

Thinking Exercise

Before writing code, work through this exercise by hand:

Exercise: Calculate Theoretical Speedup

Given:

- Task: Render 1,000,000 pixels

- Single-threaded performance: 10,000 pixels/second

- Total time on 1 core: 100 seconds

- Overhead per process: 50ms startup + 10ms per data transfer

- Available cores: 4

Questions:

- If you split into 4 chunks (one per core), what is the theoretical speedup?

- What is the actual speedup accounting for overhead?

- If you split into 16 chunks (4 chunks per core), how does overhead change?

- What is the minimum task size where multiprocessing breaks even (speedup > 1.0)?

Answers (work these out yourself first!):

Click to reveal answers

- Theoretical (no overhead):

- Each core processes 250,000 pixels

- Time per core: 250,000 / 10,000 = 25 seconds

- Speedup: 100 / 25 = 4.0x (perfect linear scaling)

- Actual (with overhead):

- Startup: 4 processes × 50ms = 200ms

- Data transfer: 4 chunks × 10ms = 40ms

- Total overhead: 240ms

- Compute time: 25 seconds

- Total time: 25.24 seconds