Professional C Programming Mastery: Real-World Projects

Goal: Master professional C by understanding the language model, the toolchain, and the machine-level consequences of your code. You will build 16 real-world projects that force you to reason about types, memory, undefined behavior, portability, I/O, security, and performance. By the end, you will be able to design robust C libraries, debug low-level failures, and explain exactly why your program behaves the way it does across compilers and platforms.

Introduction

Professional C programming is the disciplined practice of writing C that is correct, portable, secure, and performant across compilers, operating systems, and architectures. It means understanding the C abstract machine, how your compiler interprets your code, and how real hardware executes the result. This guide turns that understanding into practice by building a complete set of production-style components: allocators, string libraries, I/O layers, test frameworks, portability shims, and performance-critical data structures.

What you will build (by the end of this guide):

- A compiler behavior lab that documents undefined, unspecified, and implementation-defined behavior

- A full custom allocator and safe string/buffer libraries

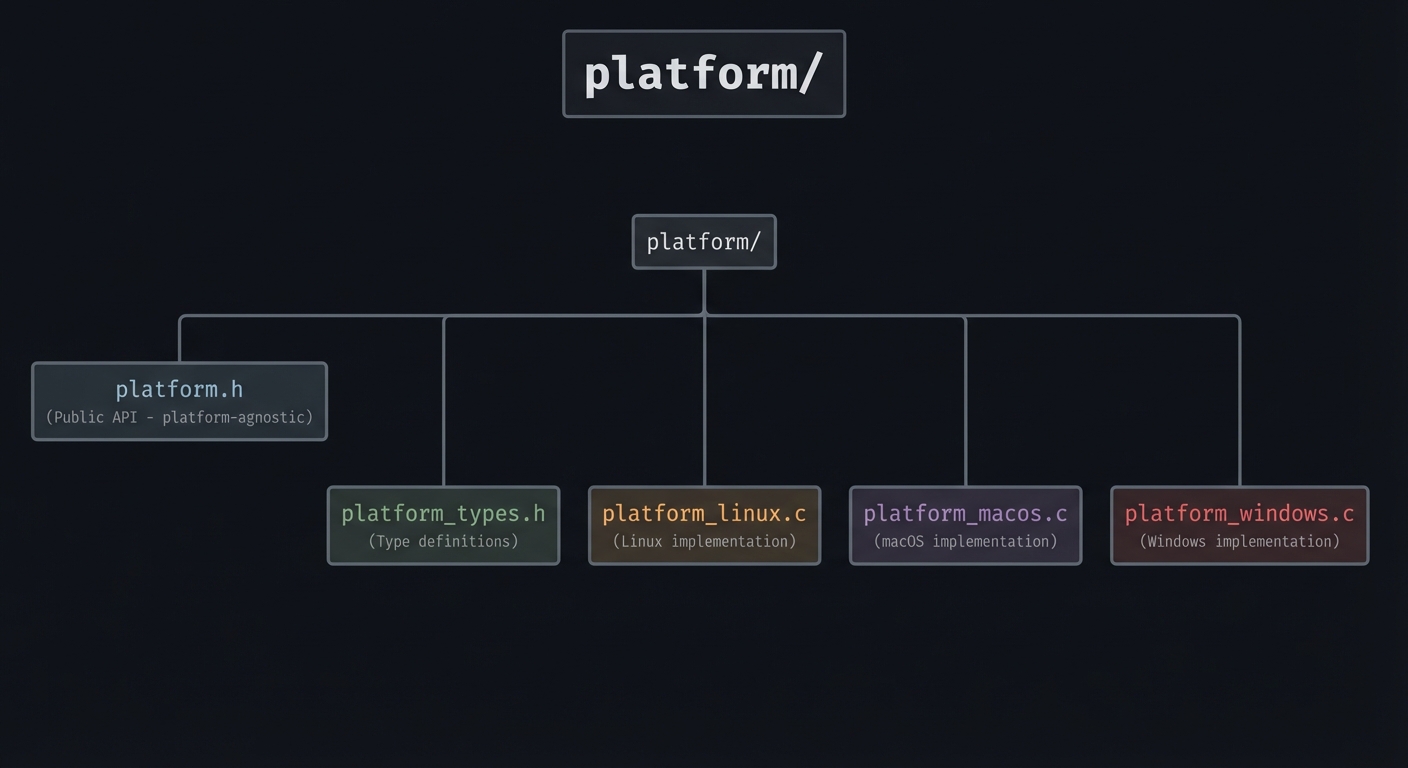

- A file I/O subsystem and a cross-platform portability layer

- A C23 features laboratory and a secure coding toolkit

- A performance-optimized data-structure benchmark suite

- A simulated real-time embedded environment

Scope (what is included):

- Modern C (C23) language and standard library usage

- The toolchain (preprocessor, compiler, linker, sanitizer, debugger)

- Memory management, data layout, and pointer safety

- Portability across compilers and operating systems

- Performance measurement and cache-aware design

Out of scope (for this guide):

- Writing operating system kernels

- C++-specific features and templates

- Vendor-specific intrinsics beyond what is needed for experiments

The Big Picture (Mental Model)

Source code -> Preprocessor -> Compiler/Optimizer -> Assembler -> Linker

| | | | |

| | | | v

| | | | Executable

| | | | |

v v v v v

Macro expansion Tokens Abstract machine Object files OS loader

| | |

v v v

Behavior categories (defined / impl-defined / unspecified / UB) -> Runtime effects

Key Terms You Will See Everywhere

- Abstract machine: The specification model the C standard uses to define behavior.

- Undefined behavior (UB): The program violates a rule; the standard imposes no requirements.

- Implementation-defined: Behavior must be documented by the compiler/ABI.

- Unspecified: Multiple outcomes are permitted; the standard does not choose one.

- Object representation: The byte-level layout of a C object in memory.

How to Use This Guide

- Read the Theory Primer first. The projects assume the mental models from each chapter.

- Pick a path in “Recommended Learning Paths” and follow it. The projects build on each other.

- Keep a lab notebook. Record compiler versions, flags, and outcomes. Your notes become a reference.

- Treat warnings as errors. Build with

-Wall -Wextra -Werrorand add sanitizers early. - Measure and verify. Each project has a Definition of Done checklist. Use it.

- Revisit earlier projects. As you learn more, you will notice subtleties you missed.

Prerequisites & Background Knowledge

Before starting these projects, you should have foundational understanding in these areas:

Essential Prerequisites (Must Have)

Programming Fundamentals:

- Ability to write and run programs in any language

- Comfort with variables, functions, loops, conditionals

- Basic command-line usage

- Recommended Reading: “C Programming: A Modern Approach” (K.N. King) Ch. 1-5

Computer Architecture Basics:

- What RAM, CPU, registers, and caches are

- Binary and hexadecimal number systems

- Recommended Reading: “Code: The Hidden Language” (Petzold) Ch. 10-14

Helpful But Not Required

Systems Programming Concepts:

- Process vs thread

- Files and file descriptors

- Can learn during: Projects 8, 10, 12

Assembly and Toolchain Basics:

- What a compiler outputs

- How a linker resolves symbols

- Can learn during: Projects 1, 9, 10

Self-Assessment Questions

- Can I compile and run a C program from the command line?

- Can I explain the difference between a pointer and the value it points to?

- Do I understand what

sizeofreturns for arrays vs pointers? - Can I read a compiler error message and fix the code?

- Do I know what undefined behavior is and can I name an example?

If you answered “no” to questions 1-3, spend 1-2 weeks with “Head First C” Ch. 1-6 first.

Development Environment Setup

Required Tools:

- A Linux or macOS system (Windows + WSL2 is acceptable)

- GCC 14+ or Clang 18+ for strong C23 support

makeorcmakegdborlldb

Recommended Tools:

valgrind(Linux) orleaks(macOS)clang-tidyorcppcheckperforhyperfinefor benchmarking

Testing Your Setup:

# Compilers

$ gcc --version

$ clang --version

# C23 mode (compiler support varies)

$ cat > /tmp/c23_test.c <<'C'

#include <stdckdint.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

int a = 1000000, b = 2000000, out = 0;

if (ckd_mul(&out, a, b)) {

puts("overflow");

} else {

printf("%d\n", out);

}

return 0;

}

C

$ clang -std=c23 /tmp/c23_test.c -o /tmp/c23_test && /tmp/c23_test

# Sanitizers

$ clang -fsanitize=address,undefined -g /tmp/c23_test.c -o /tmp/c23_test_asan

$ /tmp/c23_test_asan

Time Investment

- Simple projects (1, 2, 5): 4-8 hours each

- Moderate projects (3, 4, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11): 1-2 weeks each

- Complex projects (6, 12, 13, 14): 2-3 weeks each

- Advanced projects (15, 16): 3-4 weeks each

Important Reality Check

C is a power tool. The standard assumes you know what you are doing, and the compiler will optimize under that assumption. This guide teaches you to build correct mental models first, then use those models to write code that is both safe and fast.

Big Picture / Mental Model

+------------------+ +------------------+

| C Source Code | | Header Files |

+---------+--------+ +---------+--------+

| |

v v

+--------+---------+ +---------+--------+

| Preprocessor |------->| Preprocessed C |

+--------+---------+ +---------+--------+

| |

v v

+--------+---------+ +---------+--------+

| Compiler/IR |------->| Optimized IR |

+--------+---------+ +---------+--------+

| |

v v

+--------+---------+ +---------+--------+

| Assembler |------->| Object Files |

+--------+---------+ +---------+--------+

| |

+------------+---------------+

v

+-------+-------+

| Linker |

+-------+-------+

v

+-------+-------+

| Executable |

+-------+-------+

v

+-------+-------+

| OS Loader |

+---------------+

Behavior rules (defined / impl-defined / unspecified / UB) apply at the abstract machine level,

then the optimizer maps those rules to actual machine code.

Theory Primer

This section is the mini-book. Each chapter builds a mental model you will use in multiple projects.

Chapter 1: The C Abstract Machine and Behavior Categories

Fundamentals

The C standard defines an abstract machine: an idealized model of how C programs execute. Your compiler maps your source code into real machine code, but the abstract machine defines what that code is allowed to do. This is why C has multiple behavior categories. Well-defined behavior is the part you can rely on across platforms. Implementation-defined behavior is defined by each compiler/ABI (and must be documented). Unspecified behavior means multiple outcomes are allowed and the standard does not choose one. Undefined behavior (UB) means the program violated a rule, and the compiler is no longer constrained. Professional C programming is largely about keeping your program in the well-defined subset, and consciously managing where you rely on implementation-defined behavior for performance or interoperability.

Deep Dive into the Concept

The C abstract machine exists to allow compilers to generate efficient machine code for a wide variety of hardware. The standard does not describe any specific CPU or OS. Instead, it gives semantic rules: how expressions are evaluated, how objects are laid out, and what happens when you read or write them. The compiler then proves that your program follows those rules and applies optimizations that would be invalid if the rules were violated. This is why UB is so dangerous: once the compiler proves that “this cannot happen” under the abstract machine, it can transform the program in ways that seem surprising when the rule is violated at runtime.

Consider signed integer overflow. In C, signed overflow is undefined behavior. That means the compiler can assume it never happens. If you write if (x + 1 < x) { ... }, the compiler is allowed to remove the branch entirely, because in the abstract machine x + 1 cannot be less than x for signed integers. This enables optimizations like loop strength reduction, vectorization, and common subexpression elimination. But it also means a program that does overflow might behave in seemingly unrelated ways, because the optimizer built a proof that overflow cannot happen and rearranged code accordingly.

Implementation-defined behavior is less dangerous because the compiler must document it. Examples include the size of int, the signedness of char, and the calling convention. When you read the compiler documentation (or ABI), you are explicitly choosing to rely on those definitions. This is often necessary for low-level code. For instance, you might depend on little-endian layout or two’s complement representation. The key is to document the dependency and isolate it so you can change it later.

Unspecified behavior is subtle. The classic example is the evaluation order of function arguments. The compiler is allowed to evaluate arguments in any order, and even interleave them with other computations. If your program depends on a particular order, it can break with different optimization levels or compilers. The fix is to break expressions into multiple statements or use sequencing operators (&&, ||, ,) that impose order.

Finally, there is the category of “constraints” in the standard. A constraint violation (like calling a function with the wrong number of arguments) requires a diagnostic. But after the diagnostic, behavior is still undefined unless the compiler provides a recovery extension. This is why professional code treats warnings as errors.

The “as-if rule” ties this all together. Compilers may transform programs freely as long as the observable behavior is the same as if the program were executed by the abstract machine. Observable behavior includes volatile accesses and I/O operations. Everything else can be rearranged or removed. This explains why reading uninitialized memory or using a dangling pointer can cause outcomes that seem unrelated to the bug itself: the compiler has already optimized under the assumption that such reads do not occur.

Understanding these categories is not just academic. It affects testing (your tests might pass at -O0 but fail at -O3), portability (your code may rely on implementation-defined features you did not know existed), and security (many vulnerabilities stem from UB). In professional C, you must learn to spot UB, design around it, and use tools (sanitizers, static analyzers) to catch it early.

How This Fits in Projects

You will apply this chapter directly in Projects 1, 4, 11, 14, and 15, and indirectly in almost every other project. The compiler behavior lab, expression mastery, and secure coding projects all depend on your understanding of UB and behavior categories.

Definitions & Key Terms

- Abstract machine: The model used by the C standard to define program behavior.

- As-if rule: Compilers may optimize as long as observable behavior is preserved.

- Undefined behavior (UB): The standard imposes no requirements; anything may happen.

- Implementation-defined behavior: Must be documented by the compiler/ABI.

- Unspecified behavior: Multiple outcomes allowed, no documentation required.

- Constraint violation: A rule the compiler must diagnose (typically a warning/error).

Mental Model Diagram

Source code

|

v

Abstract machine rules

|

v

Compiler proves constraints + assumes UB never happens

|

v

Optimizer transforms program

|

v

Machine code

|

v

Observed behavior (only I/O + volatile are "observable")

How It Works (Step-by-Step, Invariants, Failure Modes)

- Write code that (ideally) respects the C rules.

- Compiler checks constraints and emits diagnostics for violations.

- Optimizer assumes UB never occurs and rewrites code.

- Executable runs; only observable behavior must match the abstract machine.

Invariants:

- You must not trigger UB (e.g., signed overflow, out-of-bounds access).

- You must not rely on unspecified evaluation order.

- If you rely on implementation-defined behavior, document it.

Failure modes:

- Miscompiled code at higher optimization levels.

- Inconsistent behavior across compilers/architectures.

- Security vulnerabilities from out-of-bounds or use-after-free.

Minimal Concrete Example

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

int x = 2147483647; // INT_MAX on many platforms

int y = x + 1; // UB if overflow occurs

if (y < x) {

puts("overflow detected");

} else {

puts("no overflow");

}

return 0;

}

Common Misconceptions

- “UB just means the program will crash.” (It may do anything, including appear to work.)

- “If it passes tests at -O0, it is correct.” (Optimization can change behavior.)

- “Implementation-defined behavior is the same as UB.” (It is documented; UB is not.)

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- What is the difference between unspecified behavior and undefined behavior?

- Why can the compiler remove a branch that tests for signed overflow?

- What does the as-if rule allow the optimizer to do?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- Unspecified behavior allows multiple outcomes but still conforms to the standard; UB removes all requirements.

- Because the abstract machine says signed overflow cannot happen, so

x + 1 < xis always false. - It allows any transformation that preserves observable behavior (I/O and volatile effects).

Real-World Applications

- Building portable libraries that must work across compilers and CPUs.

- Auditing security-critical code for UB (buffer overflows, invalid pointer use).

- Debugging code that behaves differently at different optimization levels.

Where You Will Apply It

- Project 1: Compiler Behavior Laboratory

- Project 4: Expression and Operator Mastery

- Project 11: Testing and Analysis Framework

- Project 14: Secure String and Buffer Library

- Project 15: Performance-Optimized Data Structures

References

- “Effective C, 2nd Edition” (Seacord) Ch. 1-3

- “Expert C Programming” (van der Linden) Ch. 1-2

- John Regehr’s UB articles (blog.regehr.org)

Key Insight

The compiler is not a simulator of your CPU; it is a proof engine that assumes UB never happens.

Summary

The abstract machine defines the contract between your code and the compiler. If you violate that contract, the compiler is free to do anything. Professional C programmers keep programs inside the well-defined subset, isolate reliance on implementation-defined behavior, and use tooling to detect UB early.

Homework/Exercises

- Write five tiny programs that each trigger a different class of UB.

- Compile them with GCC and Clang at

-O0and-O3and compare outputs. - Document which behaviors are consistent and which diverge.

Solutions

- Use common UB cases: signed overflow, uninitialized read, out-of-bounds access, invalid shift, use-after-free.

- Compare outputs across compilers and optimization levels.

- Summarize results in a table with compiler/flags/outcome columns.

Chapter 2: Types, Objects, Alignment, and Effective Types

Fundamentals

In C, everything you manipulate is an object with a type, a size, and an alignment requirement. The type system tells the compiler how many bytes an object occupies and how to interpret those bytes. Alignment rules determine which addresses are valid for each type; violating alignment can cause crashes on some architectures or slowdowns on others. Structs and unions introduce padding and layout constraints that are often invisible in source code but critical for ABI compatibility and performance. Professional C programmers must understand how object representation, padding, and alignment affect correctness, binary compatibility, and memory usage.

Deep Dive into the Concept

The C type system is deceptively simple on the surface but has deep consequences for layout, aliasing, and optimization. Every object has a type, and that type implies a representation in memory. For example, int might be 4 bytes with 4-byte alignment on one platform and 2 bytes on another. The compiler uses this information to generate loads and stores, and to determine which operations are legal. When you access an object using a type that is not compatible with its effective type, you can trigger undefined behavior via the strict aliasing rule.

Alignment is the rule that objects of a given type must be stored at addresses that are multiples of some power of two. CPUs often require or strongly prefer aligned accesses. The compiler assumes you follow these rules, so it may use alignment-sensitive instructions. If you break alignment (for example, by casting a char* to an int* pointing at an unaligned address), behavior can be undefined or slower. The _Alignof and _Alignas operators allow you to query and enforce alignment, which is especially important for SIMD or custom allocators.

Padding is the hidden space inside structs inserted to satisfy alignment. Consider:

struct S {

char c; // 1 byte

int i; // 4 bytes

};

On most systems, struct S will be 8 bytes, not 5, because the compiler inserts 3 bytes of padding after c to align i. That padding is uninitialized and may contain garbage, which matters for serialization and hashing. If you memcmp two structs with padding, the padding may differ even if the fields are identical. Professional code either initializes padding or avoids relying on bytewise comparisons for structs.

Effective type is a rule that tells the compiler which type an object “is” for aliasing purposes. If you allocate raw memory with malloc, it has no effective type until you store a value into it. After that, the object takes on the effective type of the stored value. Accessing it through an incompatible type can break strict aliasing. The safe escape hatch is unsigned char (or char), which is allowed to alias any object representation. That is why memcpy works and why binary serialization often uses unsigned char buffers.

Unions are another common pitfall. The standard only guarantees that you can read the last stored member of a union (with some exceptions). Many compilers support type punning via unions as an extension, but it is not portable. The portable approach is to use memcpy into a different type. This matters in numeric representation experiments and in low-level bit manipulations.

Bit-fields introduce additional complexity. Their layout, ordering, and padding are implementation-defined. If you use bit-fields for hardware registers, you must verify layout on each compiler/target. For networking or file formats, bit-fields are usually the wrong choice; explicit bitwise operations are safer and more portable.

Because of these rules, type choices are not merely about readability. They are a contract between your code, the compiler, and the hardware. For example, choosing uint32_t instead of unsigned int communicates a fixed-width requirement. Choosing size_t or ptrdiff_t communicates that a value represents sizes or pointer differences and will match the platform. Professional code uses the right types, validates alignment, and avoids assumptions about padding and layout unless explicitly documented.

How This Fits in Projects

This chapter powers Projects 2, 6, 7, 10, 12, and 15. The type explorer, allocator, string library, and performance data structures all depend on correct reasoning about object layout and aliasing.

Definitions & Key Terms

- Object: A region of storage that holds a value.

- Object representation: The bytes that encode an object’s value.

- Alignment: The required address multiple for a type.

- Padding: Unused bytes inserted to satisfy alignment rules.

- Effective type: The type the compiler uses for aliasing rules.

- Strict aliasing: The rule that restricts how objects may be accessed through different types.

Mental Model Diagram

Memory bytes -> Type interpretation -> Alignment rules -> Legal accesses

| | |

v v v

Object representation Effective type Optimizer assumptions

How It Works (Step-by-Step, Invariants, Failure Modes)

- You declare a type; the compiler assigns size and alignment.

- Objects are laid out with padding as needed.

- Compiler enforces aliasing rules based on effective type.

- Violations become UB or hidden bugs (memcmp, hashing, serialization).

Invariants:

- Objects must be accessed with compatible types.

- Alignment must be respected.

- Padding bytes are not meaningful unless initialized.

Failure modes:

- Crashes on architectures with strict alignment.

- Miscompilations due to strict aliasing violations.

- Incorrect serialization or hashing due to padding differences.

Minimal Concrete Example

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdalign.h>

struct S { char c; int i; };

int main(void) {

printf("sizeof(struct S) = %zu\n", sizeof(struct S));

printf("alignof(struct S) = %zu\n", alignof(struct S));

printf("offsetof i = %zu\n", offsetof(struct S, i));

return 0;

}

Common Misconceptions

- “Struct size is the sum of its fields.” (Padding is often added.)

- “Union type punning is portable.” (It is not guaranteed by the standard.)

- “Strict aliasing is only a performance issue.” (It can change program behavior.)

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- Why does

struct { char c; int i; }usually take 8 bytes? - What types are always allowed to alias any object representation?

- What is the safe way to reinterpret bytes as a different type?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- The compiler inserts padding to align the

intfield. unsigned char(andchar) may alias any object representation.- Use

memcpyinto an object of the destination type.

Real-World Applications

- Interfacing with binary protocols and file formats.

- Designing ABI-stable libraries and public C APIs.

- Building custom allocators that require strict alignment.

Where You Will Apply It

- Project 2: Type System Explorer

- Project 6: Dynamic Memory Allocator

- Project 7: String Library from Scratch

- Project 10: Modular Program Architecture

- Project 12: Cross-Platform Portability Layer

- Project 15: Performance-Optimized Data Structures

References

- “Effective C, 2nd Edition” (Seacord) Ch. 4-6

- “Understanding and Using C Pointers” (Reese) Ch. 2-4

- “C Interfaces and Implementations” (Hanson) Ch. 2-3

Key Insight

Types are not only about readability; they define the memory contract your compiler relies on.

Summary

Correct C programs depend on a precise understanding of types, layout, alignment, and effective types. Padding and aliasing rules are not optional details; they directly impact correctness and portability. Professional C code treats layout as an explicit design choice.

Homework/Exercises

- Write a program that prints size and alignment for all fundamental types.

- Create three structs with different field orderings and compare sizes.

- Show how a strict aliasing violation can change program output at

-O3.

Solutions

- Use

sizeof,_Alignof, andoffsetof. - Reorder fields to group largest to smallest to reduce padding.

- Use a union or pointer cast to produce a strict aliasing violation; compare outputs under optimization.

Chapter 3: Expressions, Conversions, and Evaluation Order

Fundamentals

C expressions are not just arithmetic; they encode evaluation order, side effects, and type conversions. A single line of code can trigger integer promotions, pointer arithmetic, and implicit conversions between signed and unsigned types. The C standard defines how values are converted but leaves many evaluation orders unspecified. This means the result of a complex expression can differ across compilers and optimization levels if you depend on a particular order. Professional C programming means writing expressions that are explicit, predictable, and safe under the C sequencing rules.

Deep Dive into the Concept

Every expression in C produces a value and may have side effects. The standard describes the value computations and the side effects, and it specifies when those side effects are guaranteed to be sequenced relative to other operations. In modern terms, operations are sequenced before or unsequenced. If two side effects on the same scalar object are unsequenced, behavior is undefined. The classic example is i = i++ + 1; where the modification of i and the read of i are unsequenced. The rule is: do not modify an object more than once between sequence points unless the intervening accesses are well-ordered.

Integer promotions and usual arithmetic conversions are central to expression semantics. For example, char and short are promoted to int (or unsigned int) before arithmetic. When you mix signed and unsigned types, the unsigned often wins, which can convert negative values into large unsigned numbers. This is the root of many bugs: size_t n = -1; results in a huge value, and comparisons between signed and unsigned can produce surprising results.

Evaluation order is often unspecified in C. The order in which function arguments are evaluated is unspecified, as is the order of evaluation for most binary operators. Only certain operators impose sequencing: &&, ||, ?:, and the comma operator. This means code like f(i++, i++) is undefined because the increments are unsequenced relative to each other, and even if it were defined, the order would be unspecified. The fix is to split expressions into multiple statements so the order is explicit.

Floating-point conversions add additional complexity. When you convert between float, double, and long double, you lose precision. Converting from floating to integer truncates toward zero and is undefined if the value is outside the target range. This matters for parsing numeric input, fixed-point conversions, and safe casting in performance code.

Bitwise operators (&, |, ^, ~, <<, >>) operate on integer types after promotions. Shifting by a negative amount or by a value greater than or equal to the width of the type is undefined. Right shifts of signed values are implementation-defined (arithmetic vs logical shift). Professional code uses unsigned types for bitwise operations to avoid surprises.

Understanding expression semantics is also vital for macro design. Macros substitute tokens, not values, so #define SQUARE(x) x*x can produce unexpected results when x has side effects. The correct macro definition uses parentheses and avoids evaluating arguments multiple times. This is one reason static inline functions are often better than macros.

Finally, expression rules affect performance. The compiler is free to reorder operations that are not sequenced, as long as observable behavior is preserved. This is why volatile or atomic operations are used for synchronization: they impose ordering constraints. In normal C code, you should write expressions that do not depend on implicit ordering, and you should use explicit sequencing when order matters.

How This Fits in Projects

This chapter is core to Projects 1 and 4, and it influences Projects 5 and 9. Expression and operator mastery is the foundation for understanding UB, macro behavior, and control flow patterns.

Definitions & Key Terms

- Sequence point / sequencing: A rule that defines when side effects are guaranteed to be complete.

- Unsequenced: Two operations whose relative order is not specified (can lead to UB).

- Integer promotions: Automatic promotion of small integer types to

int/unsigned int. - Usual arithmetic conversions: Rules for balancing types in arithmetic expressions.

- Side effect: A change to program state (modifying an object, I/O).

Mental Model Diagram

Expression -> Promotions -> Conversions -> Evaluation order -> Result + side effects

(implicit) (implicit) (often unspecified)

How It Works (Step-by-Step, Invariants, Failure Modes)

- Parse expression into operators and operands.

- Apply integer promotions and usual arithmetic conversions.

- Evaluate operands in unspecified order (unless sequencing operators force order).

- Apply operator semantics and produce value/side effects.

Invariants:

- Do not modify an object more than once without sequencing.

- Avoid mixing signed and unsigned without explicit casts.

- Do not rely on argument evaluation order.

Failure modes:

- UB from unsequenced side effects.

- Surprise results from signed/unsigned conversions.

- Compiler-dependent behavior due to unspecified order.

Minimal Concrete Example

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

int i = 1;

int a = i++ + i++; // undefined behavior

printf("%d %d\n", i, a);

return 0;

}

Common Misconceptions

- “C evaluates left-to-right like many scripting languages.” (Often false.)

- “Signed and unsigned comparisons are safe.” (Unsigned can dominate.)

- “Macros behave like functions.” (They expand as text.)

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- Why is

i = i++ + 1;undefined? - What happens when you compare

int x = -1;withsize_t y = 1;? - Which operators guarantee left-to-right evaluation?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- The read and modification of

iare unsequenced. xis converted to a large unsigned value, sox > ymay be true.&&,||,?:, and the comma operator impose sequencing.

Real-World Applications

- Writing safe arithmetic and boundary checks.

- Building correct macros and compile-time utilities.

- Avoiding UB in performance-critical loops.

Where You Will Apply It

- Project 1: Compiler Behavior Laboratory

- Project 4: Expression and Operator Mastery

- Project 5: Control Flow Pattern Library

- Project 9: Preprocessor Metaprogramming

References

- “Effective C, 2nd Edition” (Seacord) Ch. 7-9

- “C Programming: A Modern Approach” (King) Ch. 7-10

- “Expert C Programming” (van der Linden) Ch. 3-4

Key Insight

In C, the order you write expressions is not always the order the machine will evaluate them.

Summary

Expressions are where C’s power and danger collide. The language gives you speed and flexibility, but it requires discipline: avoid unsequenced side effects, understand promotions and conversions, and be explicit about evaluation order.

Homework/Exercises

- Write a program that demonstrates integer promotions with

charandshort. - Create examples where signed/unsigned conversions cause surprising results.

- Refactor a complex expression into multiple statements and compare outputs.

Solutions

- Print results of

char + charandshort + shortand show they becomeint. - Compare

-1 < 1uand explain the conversion. - Use temporaries to sequence evaluation and eliminate UB.

Chapter 4: Storage Duration, Lifetimes, and Allocation

Fundamentals

C gives you precise control over where and how long objects live. Every object has a storage duration: automatic (stack), static (global or static local), thread (thread-local), or allocated (heap). Each duration has rules about initialization, lifetime, and destruction. Misunderstanding these rules leads to common bugs: returning pointers to local variables, using freed memory, or leaking allocations. Professional C programming is about making lifetime and ownership explicit, then enforcing those rules with tools and conventions.

Deep Dive into the Concept

At runtime, a typical C program uses multiple storage regions. The stack holds automatic objects created when you enter a block or function; they are destroyed when you leave. The static storage area holds globals, static locals, and string literals; they live for the entire program duration. The heap holds dynamically allocated objects created by malloc, calloc, or realloc, and destroyed by free. Thread-local storage provides per-thread objects with static lifetime but thread scope.

The distinction between scope and lifetime is critical. Scope is a compile-time visibility rule; lifetime is a runtime existence rule. A pointer can outlive the scope of an object, and if you use it after the object’s lifetime ends, you have a dangling pointer. This is a top source of bugs and vulnerabilities. Example: returning the address of a local variable is always wrong because the local’s lifetime ends when the function returns.

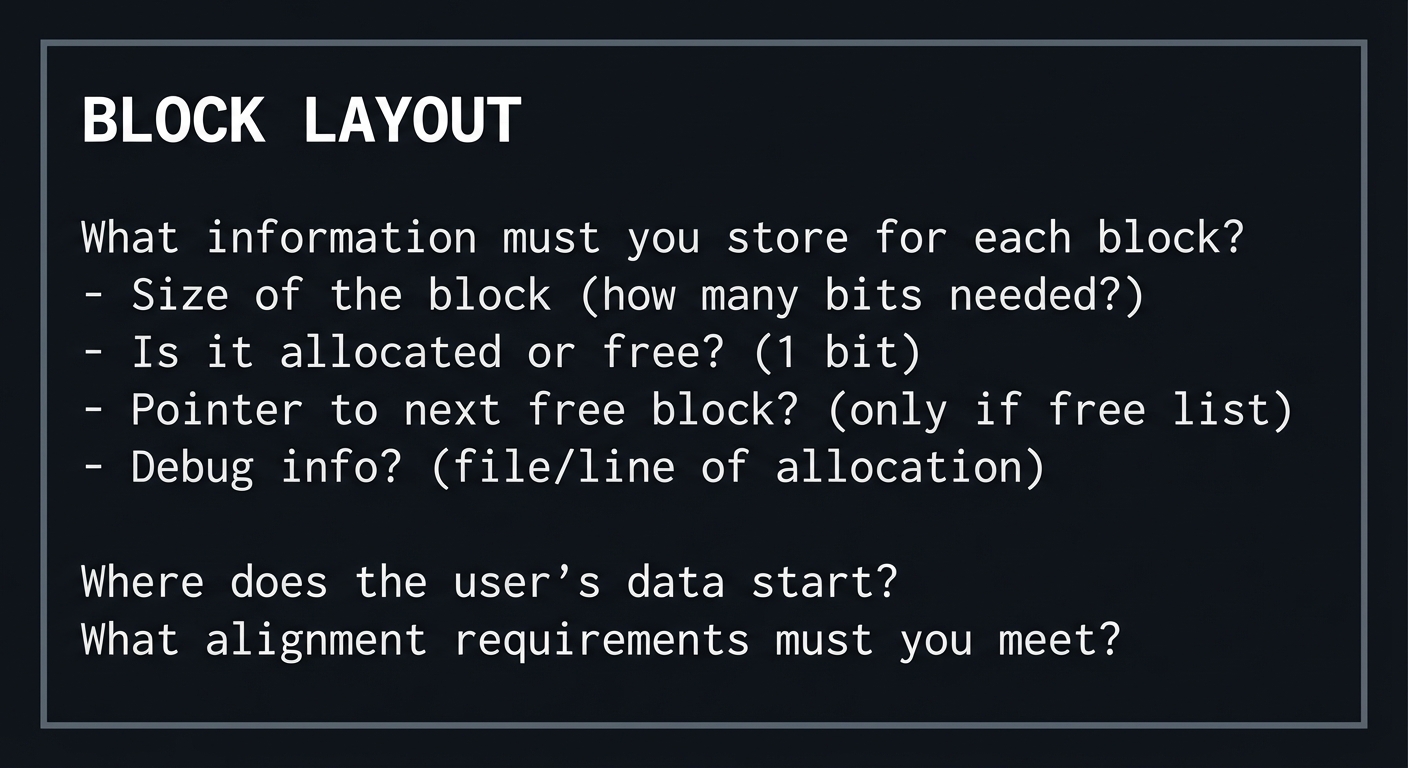

Dynamic allocation introduces its own hazards. malloc returns uninitialized memory; calloc returns zero-initialized memory. realloc may move the allocation and invalidate the original pointer. Double-free, use-after-free, and memory leaks are the classic failure modes. Allocators also have internal fragmentation (unused bytes within allocated blocks) and external fragmentation (unused space between blocks). Understanding these concepts is key for Project 6 (allocator) and Project 15 (performance).

Professional C code treats allocation as a policy decision. You choose an allocation strategy based on usage patterns: general-purpose malloc, arenas for bulk allocation, pools for fixed-size objects, or stack allocation for short-lived data. Each strategy has trade-offs in speed, memory usage, and complexity. It is common to use multiple strategies in a single system.

Alignment also matters in allocation. malloc guarantees a pointer suitable for any type, but custom allocators must enforce alignment or risk UB and performance penalties. Many allocators align to 16 bytes (or more) to support SIMD and cache line alignment.

Lifetime management also intersects with error handling. In C, you often need to release multiple resources on failure paths. This is why the “goto cleanup” pattern is idiomatic: it makes deallocation explicit and consistent. Projects 5 and 10 will teach these patterns.

Finally, the C standard library is not the whole story. On POSIX systems, there are functions like posix_memalign or aligned_alloc for aligned memory, and on Windows there are _aligned_malloc APIs. Professional C code isolates platform-specific allocation behind a small abstraction layer to stay portable.

How This Fits in Projects

This chapter is essential for Projects 5, 6, 7, 10, 14, 15, and 16. Allocation and lifetime rules underpin allocators, string libraries, error handling patterns, and embedded constraints.

Definitions & Key Terms

- Automatic storage: Objects created on block entry, destroyed on exit.

- Static storage: Objects that live for the entire program.

- Allocated storage: Objects created with

malloc/free. - Lifetime: The time interval during which an object exists.

- Dangling pointer: A pointer to an object whose lifetime has ended.

Mental Model Diagram

Stack (automatic) Heap (allocated) Static (global)

| | |

v v v

Short-lived Managed by allocators Whole program

How It Works (Step-by-Step, Invariants, Failure Modes)

- Automatic objects are created when a block is entered and destroyed on exit.

- Static objects are initialized before

mainand destroyed at program end. - Allocated objects are created by

malloc/callocand destroyed byfree. - Pointers must not outlive the lifetime of the objects they reference.

Invariants:

- Every allocated block must be freed exactly once.

- Do not use pointers after the object’s lifetime ends.

- Align allocations to the required boundary.

Failure modes:

- Use-after-free and double-free bugs.

- Memory leaks and unbounded growth.

- Misaligned access causing crashes or slowdown.

Minimal Concrete Example

#include <stdlib.h>

int *make_array(size_t n) {

int *p = malloc(n * sizeof(int));

if (!p) return NULL;

return p; // caller owns memory

}

void bad(void) {

int x = 42;

int *p = &x;

// p becomes dangling after function returns

}

Common Misconceptions

- “malloc returns zeroed memory.” (It does not; use

calloc.) - “realloc always grows in place.” (It may move memory.)

- “If the program exits, leaks do not matter.” (They matter for long-running services and libraries.)

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- What is the difference between scope and lifetime?

- When does a static local variable get initialized?

- Why is returning a pointer to a local variable unsafe?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- Scope is visibility in the source code; lifetime is runtime existence.

- It is initialized before program start (or on first use for some implementations).

- The local variable’s lifetime ends at function return, leaving a dangling pointer.

Real-World Applications

- Custom allocators for high-performance systems.

- Resource management patterns that avoid leaks.

- Embedded systems where heap usage is restricted or banned.

Where You Will Apply It

- Project 5: Control Flow Pattern Library

- Project 6: Dynamic Memory Allocator

- Project 7: String Library from Scratch

- Project 10: Modular Program Architecture

- Project 14: Secure String and Buffer Library

- Project 15: Performance-Optimized Data Structures

- Project 16: Real-Time Embedded Simulator

References

- “C Interfaces and Implementations” (Hanson) Ch. 5-6

- “The Linux Programming Interface” (Kerrisk) Ch. 6-7

- “Effective C, 2nd Edition” (Seacord) Ch. 10-12

Key Insight

In C, memory is not a convenience; it is a contract you must manage explicitly.

Summary

Storage duration and object lifetime rules are the backbone of safe C. Professional code makes ownership explicit, chooses allocation strategies intentionally, and validates memory with tools like sanitizers and Valgrind.

Homework/Exercises

- Write a program that intentionally leaks memory and detect it with Valgrind.

- Implement a simple arena allocator and compare it to

mallocfor bulk allocations. - Create a resource acquisition function that uses the “goto cleanup” pattern.

Solutions

- Use

valgrind --leak-check=full ./a.outto confirm leaks. - Use a pre-allocated buffer and a bump pointer for arena allocation.

- On failure, jump to a cleanup label that frees all acquired resources.

Chapter 5: Pointers, Arrays, Strings, and Buffers

Fundamentals

Pointers are the core abstraction in C: they let you work with memory addresses directly. Arrays are closely related; in most expressions, arrays decay to pointers to their first element. This relationship is powerful but also dangerous. Off-by-one errors, buffer overflows, and invalid pointer arithmetic are among the most common C bugs. Understanding pointer semantics, array bounds, and the structure of C strings is essential for building safe low-level libraries.

Deep Dive into the Concept

A pointer in C is a typed address. The type matters because pointer arithmetic is scaled by the size of the pointed-to type. When you add 1 to an int*, you move by sizeof(int) bytes, not 1 byte. This is why p + 1 means “the next int”. It also means that out-of-bounds pointer arithmetic can silently walk off the end of an allocation. The standard allows a pointer to move one element past the end of an array (the “one-past” rule) for comparisons or iteration, but dereferencing it is UB.

Arrays are not first-class values in C. When you pass an array to a function, it decays to a pointer and you lose size information. This is why functions that accept arrays must also accept a length parameter, and why sizeof behaves differently on arrays vs pointers. Example: sizeof(arr) is the size of the entire array in the scope where it is declared, but sizeof(ptr) is just the size of the pointer (often 8 bytes).

C strings are arrays of char terminated by a NUL byte ('\0'). This design makes strings easy to store but dangerous to manipulate. Functions like strcpy and strcat do not know the size of the destination buffer, which leads to buffer overflows. Safe string handling in C requires explicit length tracking, careful use of snprintf/strnlen, or the use of safer wrappers. A professional C coder treats every string as a (pointer, length) pair, even if the underlying representation is NUL-terminated.

Pointers also interact with the strict aliasing rule discussed in Chapter 2. A pointer to one type cannot safely access an object of an incompatible type, except for char and unsigned char. Violating this rule can yield miscompilations at high optimization levels. This is why memcpy is the portable way to reinterpret bytes, and why union type punning is nonportable without compiler extensions.

The const qualifier is another important tool. const char *p means the data is read-only through p, while char *const p means the pointer itself cannot be reassigned. Correct use of const communicates ownership and intent, and enables the compiler to enforce safety.

The restrict keyword (C99) promises that for the lifetime of a pointer, no other pointer will alias the same object. This enables optimizations and is often used in performance-sensitive code. But it is a contract: if you violate it, behavior is undefined. Use restrict only when you control all call sites and can guarantee non-aliasing.

Finally, pointer comparisons are only defined within the same array object (including one-past). Comparing pointers to unrelated objects is undefined. This matters for generic containers and memory allocators. Professional code avoids comparing unrelated pointers unless using integer types like uintptr_t for diagnostics, and even then with caution.

How This Fits in Projects

This chapter is central to Projects 6, 7, 8, 14, and 15. The string library, secure buffers, allocator, and performance projects all depend on correct pointer and array reasoning.

Definitions & Key Terms

- Pointer arithmetic: Adding/subtracting an integer to a pointer (scaled by element size).

- Array decay: Implicit conversion of array to pointer to its first element.

- One-past pointer: A pointer just past the last element; valid for comparison but not dereference.

- NUL-terminated string: A

chararray ending with\0. - Restrict: Keyword promising non-aliasing access.

Mental Model Diagram

[Array of N elements]

| e0 | e1 | e2 | ... | eN-1 | (one-past)

^

|

p points here

p+1 -> e1

p+N -> one-past (valid for comparison, invalid to dereference)

How It Works (Step-by-Step, Invariants, Failure Modes)

- Arrays decay to pointers in most expressions and function calls.

- Pointer arithmetic moves in units of the element size.

- Bounds are your responsibility; the language does not enforce them.

- C strings end at NUL; length is not stored with the buffer.

Invariants:

- Do not dereference out-of-bounds pointers.

- Always track buffer lengths explicitly.

- Do not compare unrelated pointers.

Failure modes:

- Buffer overflows and memory corruption.

- Use-after-free or out-of-bounds reads.

- Miscompilation due to aliasing violations.

Minimal Concrete Example

#include <stdio.h>

void print_buf(const char *buf, size_t n) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < n; i++) {

printf("%02x ", (unsigned char)buf[i]);

}

puts("");

}

int main(void) {

char s[] = "hi"; // 'h' 'i' '\0'

print_buf(s, sizeof(s));

return 0;

}

Common Misconceptions

- “Arrays are passed by value.” (They decay to pointers.)

- “strncpy is safe.” (It can leave strings unterminated and is slow.)

- “Pointer comparisons are always defined.” (Only within the same array object.)

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- Why does

sizeof(arr)differ fromsizeof(ptr)? - What is the one-past pointer rule?

- Why are C strings considered unsafe by default?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

sizeof(arr)is the full array size;sizeof(ptr)is just the pointer size.- You may form a pointer one element past the end of an array, but not dereference it.

- Because length is not stored, so functions can read or write past the end unless you track size.

Real-World Applications

- Secure string and buffer libraries.

- Network protocol parsers and serializers.

- Performance-sensitive data structures that rely on pointer arithmetic.

Where You Will Apply It

- Project 6: Dynamic Memory Allocator

- Project 7: String Library from Scratch

- Project 8: File I/O System

- Project 14: Secure String and Buffer Library

- Project 15: Performance-Optimized Data Structures

References

- “Understanding and Using C Pointers” (Reese) Ch. 5-8

- “Effective C, 2nd Edition” (Seacord) Ch. 13-15

- “C Programming: A Modern Approach” (King) Ch. 11-13

Key Insight

In C, a pointer is not a safe handle; it is a raw address with rules you must enforce.

Summary

Pointer and array semantics are a constant source of C bugs. Professional code treats every buffer as a (pointer, length) pair, avoids implicit assumptions, and respects the one-past rule and aliasing constraints.

Homework/Exercises

- Write a function that safely copies a buffer using explicit length checks.

- Implement

strnlenand explain how it avoids overreads. - Create a test that demonstrates a buffer overflow with

strcpyand then fix it.

Solutions

- Use

memcpywith validated lengths and return error codes for insufficient space. strnlenstops at either NUL or max length, preventing runaway reads.- Replace

strcpywithsnprintfor a length-tracked copy routine.

Chapter 6: Numeric Representation and Bit-Level Reasoning

Fundamentals

C exposes integers and floating-point numbers very close to their hardware representation. Most systems use two’s complement for integers and IEEE 754 for floating-point, but the C standard only guarantees ranges and relationships, not exact bit patterns. This makes numeric reasoning both powerful and dangerous. Professional C programmers understand how overflow, underflow, rounding, and endianness affect correctness, especially in serialization, cryptography, and performance-critical math.

Deep Dive into the Concept

Integers in C come in signed and unsigned variants, with implementation-defined sizes. Unsigned integers are defined to use modulo arithmetic: overflow wraps around. Signed integers, however, invoke undefined behavior on overflow. This distinction matters for safety and optimization. If you need defined wrap-around, use unsigned types. If you need to detect overflow, use checked arithmetic (C23’s <stdckdint.h> provides ckd_add, ckd_sub, ckd_mul).

Integer promotions and conversions interact with representation. For example, uint8_t promotes to int (or unsigned int), which can change the sign when you do bitwise operations. A common bug is shifting a signed value and expecting logical (zero-fill) shifts; the standard allows either arithmetic or logical right shift for signed types. The safe approach is to cast to an unsigned type before shifting.

Floating-point values are typically IEEE 754, but C only guarantees a minimum range and precision. IEEE 754 defines NaN, infinity, signed zero, and rounding modes. Converting a float to an integer truncates toward zero, and if the value is outside the integer range, the behavior is undefined. This is important for parsing input and for fixed-point conversions.

Endianness defines the byte order of multi-byte values in memory. Little-endian stores the least significant byte first; big-endian stores the most significant byte first. Endianness affects serialization, network protocols, and binary file formats. The standard does not specify endianness, so portable code must handle it explicitly. You can detect endianness at runtime and convert using bit shifts or standard functions (htonl, ntohl) in networking contexts.

Bitwise operations are a major tool for systems programming. They allow you to set flags, pack fields, and implement fast arithmetic. But you must respect rules: shifting by the width of the type or by a negative value is undefined; left-shifting into the sign bit is undefined for signed types. The safest pattern is to use unsigned types for bitwise work, and document assumptions about width.

Bit-fields are sometimes used for compact storage, but their layout and ordering are implementation-defined, making them unsuitable for portable file formats or protocols. If you need portable packed representations, explicit masks and shifts are more reliable.

Fixed-point arithmetic is common in embedded systems where floating-point is expensive or unavailable. You represent numbers as integers scaled by a power of two (e.g., Q16.16). This gives deterministic performance and predictable overflow behavior but requires careful scaling and rounding.

The key professional insight is that numeric representation is not just math; it is data layout and semantics. If you do not control these details, the compiler will make assumptions you did not intend.

How This Fits in Projects

This chapter is central to Projects 3, 8, 15, and 16. Numeric representation is also a hidden dependency in projects involving serialization and performance.

Definitions & Key Terms

- Two’s complement: Common signed integer representation.

- Modulo arithmetic: Unsigned overflow wraps around.

- IEEE 754: Floating-point standard defining NaN, infinity, rounding.

- Endianness: Byte order in memory.

- Fixed-point: Integer representation of scaled real numbers.

Mental Model Diagram

Integer bits -> Interpretation (signed/unsigned) -> Arithmetic rules -> Overflow behavior

Floating bits -> IEEE 754 rules -> Rounding/NaN/Inf -> Conversion behavior

How It Works (Step-by-Step, Invariants, Failure Modes)

- Choose types that match the range and semantics needed.

- Apply conversions consciously, especially signed/unsigned.

- Handle overflow explicitly (checked arithmetic or unsigned wrap).

- Normalize byte order for serialization.

Invariants:

- Use unsigned for defined wrap-around.

- Avoid signed overflow.

- Convert endianness explicitly for portable formats.

Failure modes:

- UB from signed overflow or invalid shifts.

- Data corruption due to endianness mismatches.

- Precision loss or NaN propagation in floating code.

Minimal Concrete Example

#include <stdint.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

uint16_t x = 0x1234;

unsigned char *p = (unsigned char *)&x;

printf("byte0=%02x byte1=%02x\n", p[0], p[1]);

return 0;

}

Common Misconceptions

- “Signed overflow wraps like unsigned.” (It is undefined.)

- “Bit-fields are portable.” (Layout is implementation-defined.)

- “Float to int conversion is safe.” (Out-of-range is undefined.)

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- Why is unsigned overflow defined but signed overflow is UB?

- What happens if you shift left into the sign bit of a signed integer?

- How do you make serialization portable across endianness?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- The standard explicitly defines modulo behavior for unsigned but not for signed.

- It is undefined behavior (can miscompile).

- Convert to a known byte order using masks/shifts or

htonl/ntohl.

Real-World Applications

- Binary file formats and network protocols.

- Cryptography and compression algorithms.

- Fixed-point math in embedded systems.

Where You Will Apply It

- Project 3: Numeric Representation Deep Dive

- Project 8: File I/O System

- Project 15: Performance-Optimized Data Structures

- Project 16: Real-Time Embedded Simulator

References

- “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” (Bryant, O’Hallaron) Ch. 2

- “Modern C” (Gustedt) Ch. 4-5

- “Low-Level Programming” (Zhirkov) Ch. 1-3

Key Insight

Numbers in C are data structures with rules, not just mathematical values.

Summary

Numeric representation affects portability, performance, and correctness. Professional C code treats integer and floating-point behavior as part of the program’s data model, not an implementation detail.

Homework/Exercises

- Write a program that prints the IEEE 754 bit pattern of a

float. - Implement checked multiplication using

<stdckdint.h>and compare to manual checks. - Write endianness conversion functions for 16/32/64-bit integers.

Solutions

- Use

memcpyfromfloattouint32_tand print bits. - Use

ckd_multo detect overflow and compare against manual range checks. - Use bit shifts and masks to swap bytes or detect system endianness.

Chapter 7: Translation Phases, Preprocessor, and Linkage

Fundamentals

The C toolchain is a pipeline: source code is preprocessed, compiled, assembled, and linked. The preprocessor performs textual substitution, which can radically change your program if macros are misused. Separate compilation and linkage allow large codebases, but they also introduce rules for symbol visibility and linkage that can cause subtle bugs. Professional C code treats the toolchain as part of the language, not an afterthought.

Deep Dive into the Concept

C translation happens in phases: characters are processed into tokens, macros are expanded, comments are removed, and the compiler then parses the resulting token stream. This means macros operate at the token level, not at the semantic level. A macro can replace x with x+1, but it cannot enforce types or safety. This is why macros must be carefully parenthesized and why static inline functions are often safer.

The preprocessor provides powerful techniques: include guards prevent duplicate inclusion, X-macros allow you to define a list once and generate enums, tables, or strings from it, and _Generic enables type-based dispatch. But macros also introduce hazards: they can evaluate arguments multiple times, they are not scoped, and they can create obscure debugging problems because the compiler reports errors in expanded code.

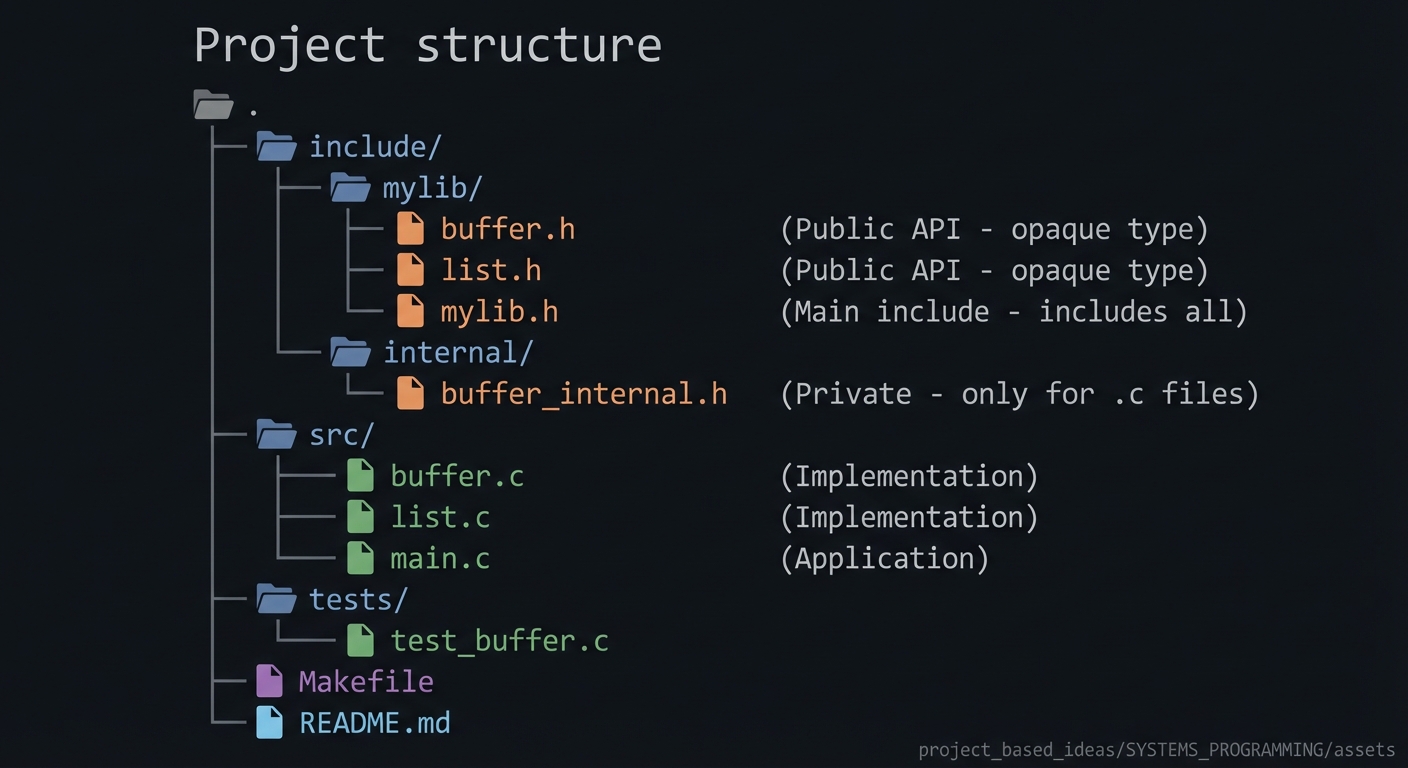

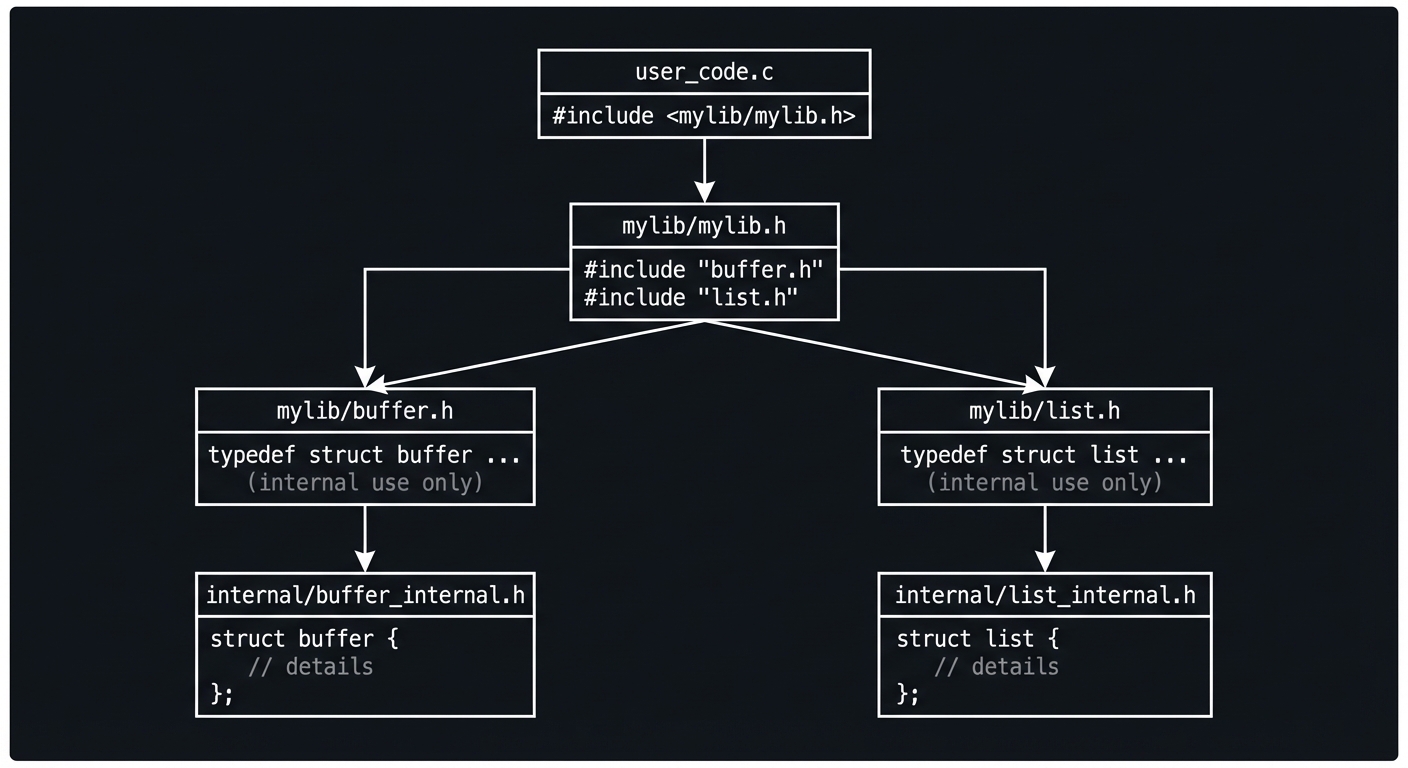

Separate compilation introduces translation units. A translation unit is a source file after preprocessing. Each translation unit is compiled independently to an object file. The linker then resolves symbols across object files. This is where static and extern matter: static gives internal linkage (symbol visible only within the translation unit), while extern declares a symbol defined elsewhere. Misusing these keywords leads to duplicate symbol errors or, worse, multiple copies of global state.

Header design is part of professional C. Headers should declare interfaces, not define storage (except for static inline functions and static const data). They should be idempotent (include guards), and they should minimize dependencies to reduce compile time. If you put function definitions in headers without static inline, you will create multiple definitions and linker errors.

Build systems and compiler flags are part of the story. Flags like -Wall -Wextra -Werror improve correctness; -O2/-O3 improve performance; -g enables debugging; -fno-strict-aliasing can mitigate aliasing bugs but at a performance cost. The linker can also perform link-time optimization (LTO) if enabled, which changes performance characteristics and sometimes exposes UB. Professional code must define a consistent build profile for debug and release, and test both.

Portability requires awareness of the platform ABI. Name mangling is not an issue in C, but calling conventions, struct layout, and alignment can vary. This is why public APIs should use stable, fixed-width types for external interfaces, and why binary compatibility is harder than source compatibility.

How This Fits in Projects

This chapter is essential for Projects 9, 10, 12, and 13. The preprocessor metaprogramming project is an explicit exercise in translation phases, and the modular architecture and portability projects rely on proper linkage discipline.

Definitions & Key Terms

- Translation unit: A source file after preprocessing.

- Internal linkage: Symbol visible only within a translation unit (

static). - External linkage: Symbol visible across translation units (

extern). - X-macros: A pattern for generating code from a single list.

- LTO: Link-time optimization performed by the linker.

Mental Model Diagram

Headers + Source -> Preprocessor -> Translation Unit -> Compiler -> Object File

^ |

| v

Include guards Linker -> Executable

How It Works (Step-by-Step, Invariants, Failure Modes)

- Preprocessor expands macros and includes headers.

- Compiler parses each translation unit independently.

- Assembler produces object files with symbols and relocations.

- Linker resolves symbols and produces the final executable.

Invariants:

- Headers should not define storage (unless

staticorinline). - Each external symbol must be defined exactly once.

- Macros must be safe against multiple evaluation.

Failure modes:

- Multiple definition linker errors.

- Subtle bugs from macro side effects.

- ABI mismatch between modules or libraries.

Minimal Concrete Example

// header.h

#ifndef HEADER_H

#define HEADER_H

int add(int a, int b); // declaration only

#endif

// file.c

#include "header.h"

int add(int a, int b) { return a + b; }

Common Misconceptions

- “Putting function bodies in headers is fine.” (It creates multiple definitions unless

static inline.) - “Macros are just like functions.” (They are text substitution.)

- “Linker errors are only build issues.” (They reflect API design problems.)

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- What is the difference between a declaration and a definition?

- Why can a macro with side effects be dangerous?

- What does

staticdo at file scope?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- A declaration introduces a symbol; a definition allocates storage or provides the body.

- The macro may evaluate its argument multiple times, causing unintended side effects.

- It gives internal linkage, making the symbol private to that translation unit.

Real-World Applications

- Building reusable C libraries with stable headers.

- Implementing portability layers across OSes.

- Using generated code for enums, tables, and dispatch.

Where You Will Apply It

- Project 9: Preprocessor Metaprogramming

- Project 10: Modular Program Architecture

- Project 12: Cross-Platform Portability Layer

- Project 13: C23 Modern Features Laboratory

References

- “Expert C Programming” (van der Linden) Ch. 5-7

- “The Linux Programming Interface” (Kerrisk) Ch. 42-44

- “Managing Projects with GNU Make” (Mecklenburg) Ch. 1-3

Key Insight

The C toolchain is part of the language; ignoring it creates fragile software.

Summary

Understanding translation phases, macros, and linkage is essential to building large, maintainable C programs. Professional C programmers design headers, build systems, and compilation models with the same care as the code itself.

Homework/Exercises

- Write an X-macro list and generate both an enum and a string table from it.

- Create a small multi-file project and intentionally break linkage rules, then fix them.

- Compare debug and release builds and document the differences in behavior.

Solutions

- Use a macro list like

X(ERR_OK) X(ERR_FAIL)and expand into enum and string array. - Add duplicate definitions or missing

externdeclarations to see linker errors. - Build with

-O0 -gvs-O3and compare output and warnings.

Chapter 8: I/O, Files, and the OS Boundary

Fundamentals

C provides two main layers of I/O: the stdio library (FILE*, fread, fwrite, fprintf) and the low-level OS interfaces (read, write, file descriptors on POSIX). stdio is buffered and portable, while low-level I/O is unbuffered and OS-specific. Professional C programmers must understand both, because buffering, error handling, and binary/text mode differences can break programs in subtle ways.

Deep Dive into the Concept

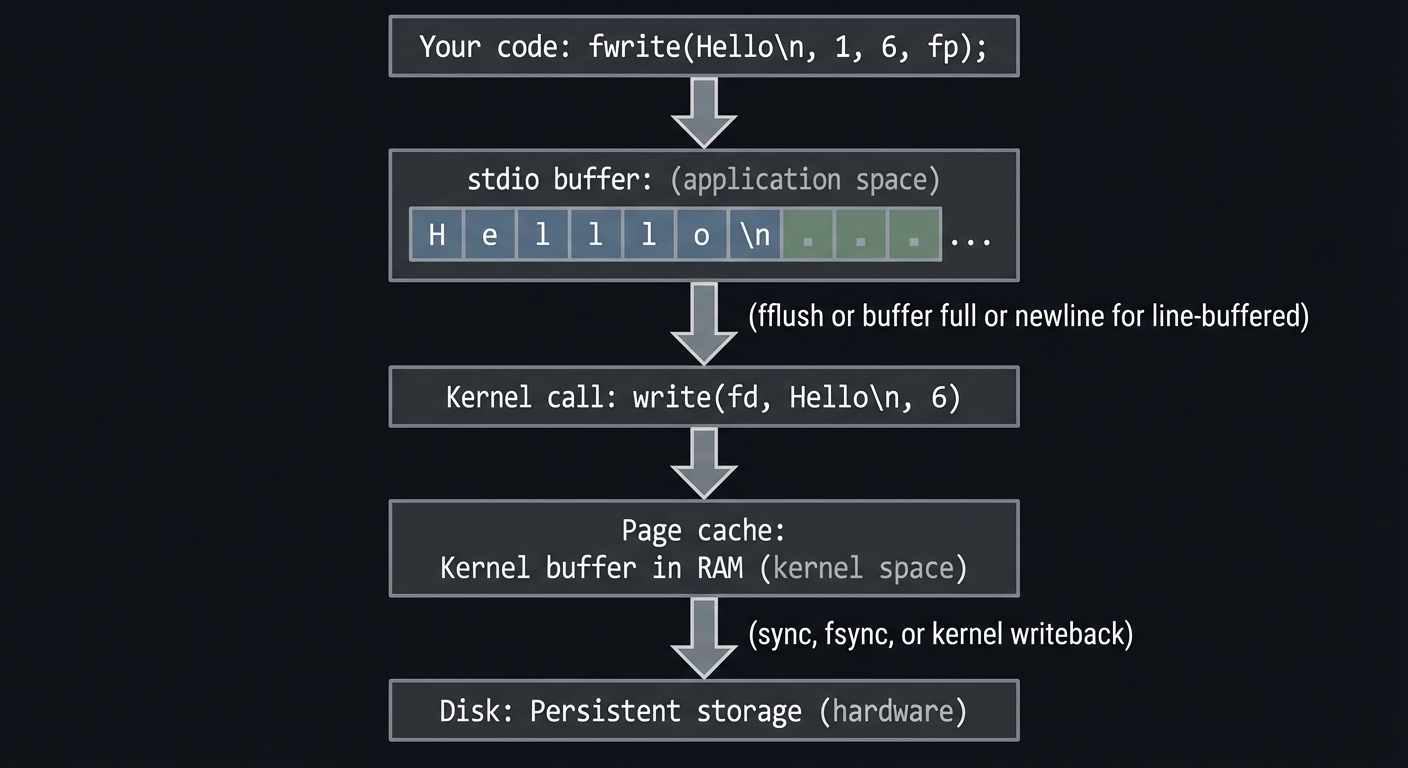

The stdio library is designed for portability and convenience. A FILE* wraps an OS-level file descriptor and adds buffering. The buffer reduces system calls, which improves performance. But buffering also introduces ordering issues: data written with fprintf may not reach the disk until you flush or close the stream. This is why logs can disappear after a crash if you do not flush, and why you must call fflush when you need data to be visible immediately.

There are three buffering modes: fully buffered (default for files), line buffered (default for terminals), and unbuffered (often used for stderr). You can change buffering with setvbuf. Choosing the correct mode is critical for performance and correctness in streaming applications.

Text and binary modes are another portability hazard. On Windows, text mode translates \n to \r\n and treats certain bytes as EOF. On POSIX, text and binary are the same. If you are reading or writing binary formats (images, network packets, serialized data), you must open files in binary mode ("rb", "wb") to avoid data corruption on Windows.

Error handling is subtle. Many stdio functions signal errors by returning a short count or a negative value and setting errno. feof and ferror must be checked after a read to distinguish end-of-file from errors. Low-level read/write can return partial results even on success, so robust code loops until the full buffer is processed. Nonblocking I/O complicates this further, but even blocking I/O can return partial writes if signals occur.

File positioning functions (fseek, ftell) are limited by the underlying OS and file type. For large files, use fseeko/ftello or off_t where available. For portability, treat file offsets as potentially large and avoid assuming long is large enough.

Finally, the OS boundary matters for performance and correctness. stdio is portable, but if you need precise control, you may drop to OS APIs like open, read, and write. Professional systems often wrap these in a platform abstraction so the rest of the codebase remains portable.

How This Fits in Projects

This chapter directly supports Projects 8 and 12 and indirectly affects Projects 7 and 14. File I/O, portability layers, and secure buffer handling all rely on correct I/O semantics.

Definitions & Key Terms

- FILE*: Buffered I/O stream in the C standard library.

- File descriptor: OS-level handle for open files (POSIX).

- Buffering: Accumulating data to reduce system calls.

- Text vs binary mode: Platform-specific translation of newlines and EOF.

- Partial read/write: I/O operations that transfer fewer bytes than requested.

Mental Model Diagram

Your code -> stdio buffer -> OS syscall -> kernel -> storage device

(buffered) (unbuffered)

How It Works (Step-by-Step, Invariants, Failure Modes)

- Open a stream or descriptor (

fopenoropen). - Read/write data via buffered or unbuffered APIs.

- Check errors (

ferror,errno) and handle partial results. - Flush and close to ensure data is written.

Invariants:

- Always check return values.

- Flush buffered output when needed.

- Use binary mode for binary formats on Windows.

Failure modes:

- Data loss due to unflushed buffers.

- Corrupted files due to text-mode translation.

- Partial reads/writes causing truncated data.

Minimal Concrete Example

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

FILE *f = fopen("data.bin", "wb");

if (!f) return 1;

int x = 0x12345678;

fwrite(&x, sizeof(x), 1, f);

fflush(f);

fclose(f);

return 0;

}

Common Misconceptions

- “fwrite writes all bytes or fails.” (It can write fewer elements.)

- “Text mode is the same as binary everywhere.” (Not on Windows.)

- “Checking

feofbefore reading is enough.” (You must read first, then check.)

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- Why can stdio buffering cause missing log output after a crash?

- What is the correct way to detect EOF vs error?

- When do you need to use binary mode?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- Data may still be in the buffer and not flushed to disk.

- Perform a read, then check

feofandferror. - Whenever you read/write binary formats, especially on Windows.

Real-World Applications

- Implementing loggers and data pipelines.

- Building binary file formats or network packet capture tools.

- Writing portability layers for different OSes.

Where You Will Apply It

- Project 8: File I/O System

- Project 12: Cross-Platform Portability Layer

- Project 14: Secure String and Buffer Library

References

- “The Linux Programming Interface” (Kerrisk) Ch. 13-14

- “Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment” (Stevens, Rago) Ch. 3-5

- “Practical C Programming” (Oualline) Ch. 11-12

Key Insight

I/O is not just reading and writing bytes; it is an interaction with the OS and its buffering rules.

Summary

Robust C I/O requires careful handling of buffering, partial reads/writes, and platform differences. Professional C programmers treat I/O as a system boundary, not a simple API call.

Homework/Exercises

- Write a file copier that handles partial reads/writes correctly.

- Implement a hex dump tool that reads binary data safely.

- Compare buffered vs unbuffered I/O performance for large files.

Solutions

- Use a loop around

read/write(orfread/fwrite) and check for partial results. - Read into a byte buffer and print hex with offsets.

- Benchmark using

timeorhyperfineand vary buffer sizes.

Chapter 9: Safety, Tooling, and Modern C (C23)

Fundamentals

Professional C code is built with aggressive warnings, runtime sanitizers, and static analysis. These tools catch undefined behavior, memory safety bugs, and API misuse before they reach production. Modern C standards also add features that improve safety and expressiveness. C23 introduces new language and library features such as nullptr, _BitInt, and checked integer arithmetic (<stdckdint.h>), and compilers are steadily improving support. The combination of disciplined coding and tooling is how professional C code stays safe and maintainable.

Deep Dive into the Concept

Compiler warnings are your first line of defense. Flags like -Wall -Wextra -Wconversion -Wshadow (plus -Werror in CI) surface many classes of bugs: missing returns, implicit conversions, sign mismatches, and unused variables. Warnings are not perfect, but they dramatically reduce defect rates when treated seriously.

Sanitizers are runtime instrumentation tools. AddressSanitizer (ASan) inserts red zones around heap/stack objects and uses shadow memory to detect out-of-bounds and use-after-free. UndefinedBehaviorSanitizer (UBSan) inserts checks for UB such as signed overflow or invalid shifts. MemorySanitizer (MSan) tracks uninitialized memory, and ThreadSanitizer (TSan) detects data races. These tools are extremely effective at surfacing bugs that tests would otherwise miss.

Static analysis (clang-tidy, cppcheck, CodeQL) inspects code without executing it. It can detect issues like null dereferences, unchecked return values, and insecure functions. Static analysis is essential for large codebases because it scales without running tests and can enforce style and safety rules.

Fuzzing complements testing by generating random or adversarial inputs. Libraries like libFuzzer or AFL can quickly find parser bugs, buffer overruns, and assertion failures. Fuzzing is particularly important for string libraries, file parsers, and network protocol handling (Projects 7, 8, 14).

Modern C (C23) adds features that improve safety and clarity. According to compiler status pages and release notes, C23 includes:

nullptrandnullptr_tfor safer null pointer constants._BitInt(N)for fixed-width integer types beyond 64 bits.<stdckdint.h>for checked arithmetic (ckd_add,ckd_sub,ckd_mul).- Standard attributes like

[[deprecated]],[[maybe_unused]], and[[nodiscard]].

Support varies by compiler and version, so professional code must check feature availability and provide fallbacks. The standard itself (ISO/IEC 9899:2024) defines the behavior, while compiler docs detail what is implemented.

Secure C guidelines (such as the CERT C Coding Standard) provide rules for avoiding common vulnerabilities: buffer overflows, integer overflows, format string bugs, and undefined behavior. Many organizations treat these guidelines as part of their coding standards. The key is to encode them into your tooling: static analysis, sanitizer builds, and mandatory code review checklists.

The professional workflow is therefore: write code, compile with warnings-as-errors, run unit tests under sanitizers, run static analysis, and fuzz critical components. The earlier you integrate these steps, the less time you spend debugging low-level failures.

How This Fits in Projects

This chapter underpins Projects 1, 11, 13, and 14. Your compiler behavior lab, test framework, C23 features lab, and secure string library all depend on modern tooling and safety practices.

Definitions & Key Terms

- ASan/UBSan/TSan/MSan: Sanitizers for memory, UB, threading, and uninitialized memory.

- Static analysis: Automated reasoning about code without running it.

- Fuzzing: Randomized testing to find edge cases and crashes.

- C23: The ISO C standard revision published in 2024.

- CERT C: Secure coding standard for C.

Mental Model Diagram

Code -> Warnings -> Tests -> Sanitizers -> Static Analysis -> Fuzzing

(compile) (run) (runtime) (analysis) (random inputs)

How It Works (Step-by-Step, Invariants, Failure Modes)

- Compile with warnings-as-errors.

- Run unit tests under sanitizers.

- Run static analysis and fix findings.

- Fuzz inputs for parsers and libraries.

Invariants:

- Zero sanitizer findings in CI.

- Warnings treated as errors.

- Critical code paths fuzzed and reviewed.

Failure modes:

- Security vulnerabilities from unchecked inputs.

- UB that only appears under optimization.

- Silent data corruption from integer overflow.

Minimal Concrete Example

#include <stdckdint.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

int a = 1000000, b = 2000000, out = 0;

if (ckd_mul(&out, a, b)) {

puts("overflow detected");

} else {

printf("%d\n", out);

}

return 0;

}

Common Misconceptions

- “Warnings are optional.” (They are early indicators of real bugs.)

- “Sanitizers are too slow to use.” (Use them in tests and CI, not necessarily production.)

- “C23 features are everywhere.” (Support varies; always check compiler status.)

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- What kinds of bugs does ASan detect?

- Why is fuzzing especially valuable for parsers?

- How should you handle C23 features on older compilers?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- Out-of-bounds reads/writes, use-after-free, and other memory errors.

- Parsers handle untrusted input; fuzzing explores edge cases that unit tests miss.

- Use feature detection and provide fallback implementations or compatibility layers.

Real-World Applications

- Hardening libraries against exploitation.

- Reducing security incidents in embedded and systems software.

- Creating CI pipelines that enforce safe C practices.

Where You Will Apply It

- Project 1: Compiler Behavior Laboratory

- Project 11: Testing and Analysis Framework

- Project 13: C23 Modern Features Laboratory

- Project 14: Secure String and Buffer Library

References

- ISO/IEC 9899:2024 (C23) standard overview (iso.org)

- GCC 14 and Clang 18 C23 status pages

- CERT C Coding Standard (SEI)

Key Insight

C safety is not a single feature; it is a disciplined toolchain and workflow.

Summary

Modern C development relies on compiler diagnostics, sanitizers, static analysis, and careful use of newer language features. Professional C programmers embed these tools into their workflow to catch bugs early and enforce secure coding practices.

Homework/Exercises

- Compile a project with

-fsanitize=address,undefinedand fix all findings. - Run

clang-tidyand resolve at least five warnings. - Write a fuzz target for your string library and run it for an hour.

Solutions

- Add sanitizer builds to your Makefile or CMake.

- Use

clang-tidy -checks='*'and suppress only with justification. - Use libFuzzer with a corpus of real and randomized inputs.

Chapter 10: Performance and Cache-Aware Design

Fundamentals

Performance in C is not just about algorithms; it is about data layout, memory access patterns, and measurement discipline. Modern CPUs are extremely fast at arithmetic but slow at fetching data from memory. Cache misses, branch mispredictions, and poor locality can dominate runtime. Professional C programmers design data structures and loops that respect the memory hierarchy and measure performance with real workloads.

Deep Dive into the Concept

CPUs access memory through a hierarchy: registers, L1/L2/L3 caches, main memory, and storage. Accessing L1 cache may take a few cycles; main memory can take hundreds. This means cache locality is often more important than raw instruction count. If your data is laid out contiguously, you benefit from spatial locality. If you access the same data repeatedly, you benefit from temporal locality. Poor locality can make a fast algorithm slow in practice.

Data layout is the first lever. An array-of-structs (AoS) layout keeps fields for one object together; a struct-of-arrays (SoA) layout keeps each field in its own array. AoS is convenient for per-object operations, but SoA is often better for vectorized or cache-friendly operations. Performance-critical code often uses SoA for hot loops and AoS for configuration or metadata.

Alignment and padding affect cache line usage. If a struct crosses cache line boundaries frequently, you pay extra misses. Aligning hot structures to cache lines (often 64 bytes) can help. alignas(64) and careful field ordering can reduce false sharing in multithreaded code.

Branch prediction is another factor. Unpredictable branches cause pipeline flushes. Techniques like branchless programming, lookup tables, or data-driven loops can improve performance, but at the cost of readability. Measure before you optimize.

Benchmarking discipline is critical. Microbenchmarks can lie due to cache warmup, CPU frequency scaling, and compiler optimizations that remove “dead” code. Use tools like hyperfine, perf, or cachegrind to measure. Always benchmark with realistic workloads and multiple iterations, and report variance (min/median/max). Pin your process to a CPU core if possible and disable turbo for consistent results.

Compiler optimization flags (-O2, -O3, -march=native) can dramatically change performance. But optimizations can also expose UB and change numeric precision. Professional code maintains separate debug and release builds and validates correctness under optimization.

Finally, remember that algorithmic complexity still matters. Cache-aware tweaks cannot rescue a poor algorithm. The best performance comes from combining good algorithms with cache-conscious implementations.

How This Fits in Projects

This chapter drives Project 15 and influences Projects 6, 7, and 10. The performance data structures project is the explicit application, but allocator and string performance also depend on these principles.

Definitions & Key Terms

- Cache line: The unit of data transferred between memory and cache (often 64 bytes).

- Spatial locality: Accessing data stored close together.

- Temporal locality: Reusing data in a short time window.

- False sharing: Multiple threads writing to different data in the same cache line.

- Microbenchmark: A small benchmark that measures isolated operations.

Mental Model Diagram

CPU registers -> L1 cache -> L2 cache -> L3 cache -> RAM

(fast) (fast) (medium) (slower) (slow)

How It Works (Step-by-Step, Invariants, Failure Modes)