Understanding PDF Generation from PostScript & Ghostscript

Goal: Master the complete document processing pipeline—from understanding PostScript as a stack-based programming language that draws, to PDF as a structured document format, to Ghostscript as the transformation engine between them. By completing these projects, you’ll understand what really happens when you “print to PDF,” why these formats were designed the way they were, and how production-grade document processors work at a systems level.

Why PostScript, PDF, and Ghostscript Matter

In 1984, Adobe invented PostScript to solve a fundamental problem: how to describe pages of text and graphics in a way that any printer could reproduce exactly. Their solution was radical—make it a Turing-complete programming language.

That decision shaped modern computing:

- Every PDF you’ve ever seen is descended from PostScript. PDF is “PostScript without the programming”

- Every laser printer from 1985-2010 had a PostScript interpreter built-in (literally a computer inside your printer)

- The entire desktop publishing revolution (PageMaker, QuarkXPress, InDesign) was built on PostScript

- Ghostscript (1988-present) is the open-source implementation that powers Linux printing, PDF generation, and document conversion worldwide

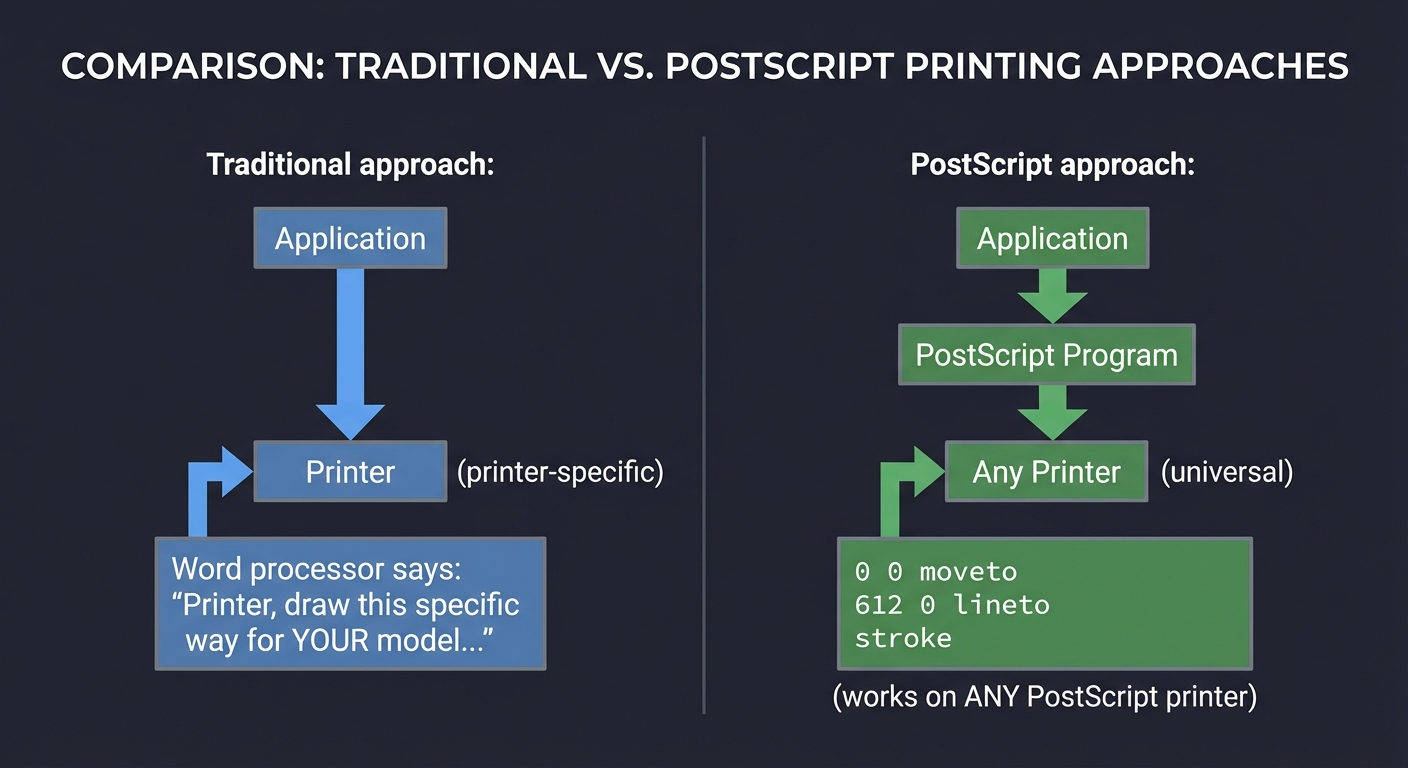

The key insight that makes this whole ecosystem work:

Traditional approach: PostScript approach:

Application → Printer Application → PostScript Program → Any Printer

(printer-specific) (universal)

Word processor says: Word processor emits:

"Printer, draw this 0 0 moveto

specific way for YOUR 612 0 lineto

model..." stroke

(works on ANY PostScript printer)

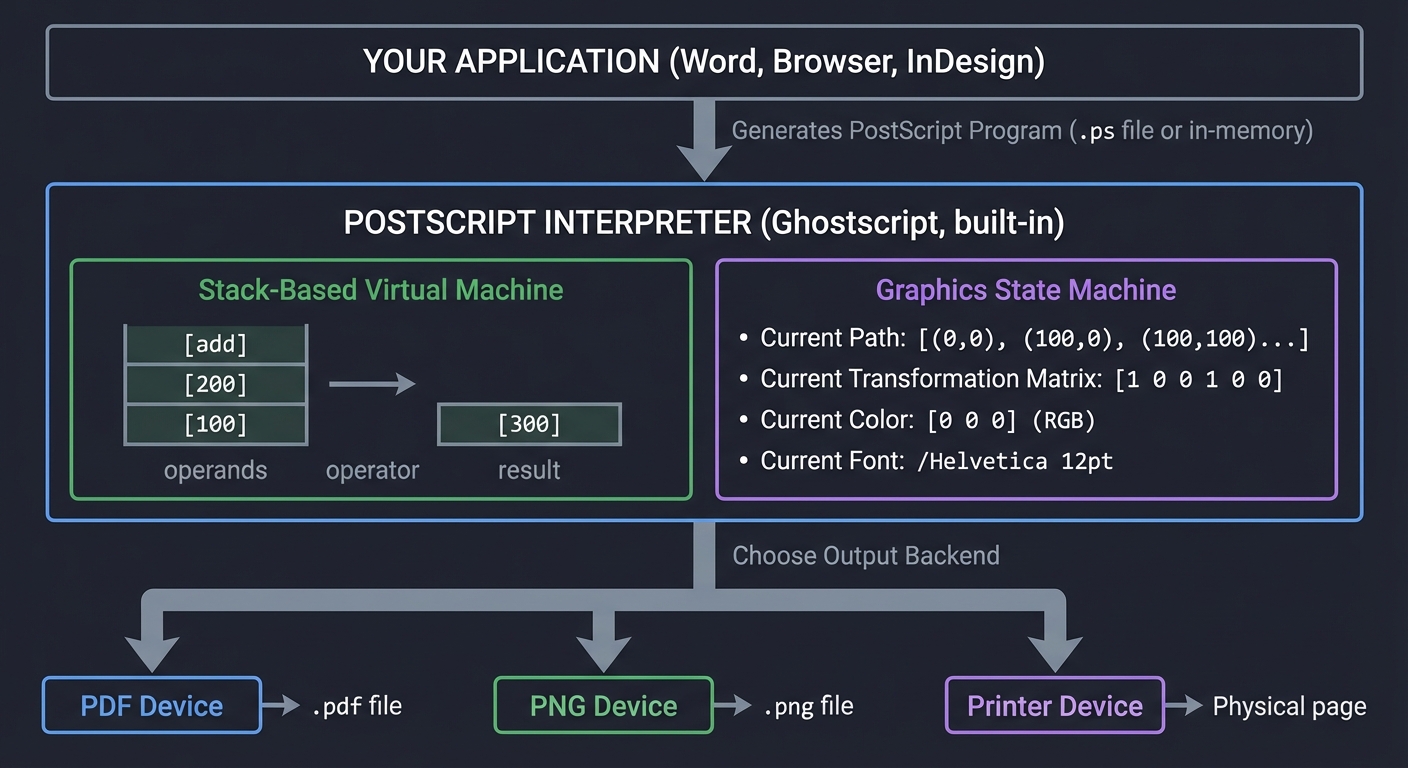

The Document Processing Pipeline: What Actually Happens

When you click “Export as PDF” or “Print to PDF,” here’s the real flow:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ YOUR APPLICATION │

│ (Word, Browser, InDesign) │

└────────────────────────────┬────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

Generates PostScript Program

(.ps file or in-memory)

│

▼

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ POSTSCRIPT INTERPRETER │

│ (Ghostscript, built-in) │

│ │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Stack-Based Virtual Machine │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Stack: [100] [200] [add] → [300] │ │

│ │ operands operator result │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ ↓ │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Graphics State Machine │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ • Current Path: [(0,0), (100,0), (100,100)...] │ │

│ │ • Current Transformation Matrix: [1 0 0 1 0 0] │ │

│ │ • Current Color: [0 0 0] (RGB) │ │

│ │ • Current Font: /Helvetica 12pt │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

└────────────────────────────┬────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

Choose Output Backend

│

┌───────────────────┼───────────────────┐

▼ ▼ ▼

┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐ ┌──────────┐

│ PDF │ │ PNG │ │ Printer │

│ Device │ │ Device │ │ Device │

└─────────┘ └─────────┘ └──────────┘

│ │ │

▼ ▼ ▼

.pdf file .png file Physical page

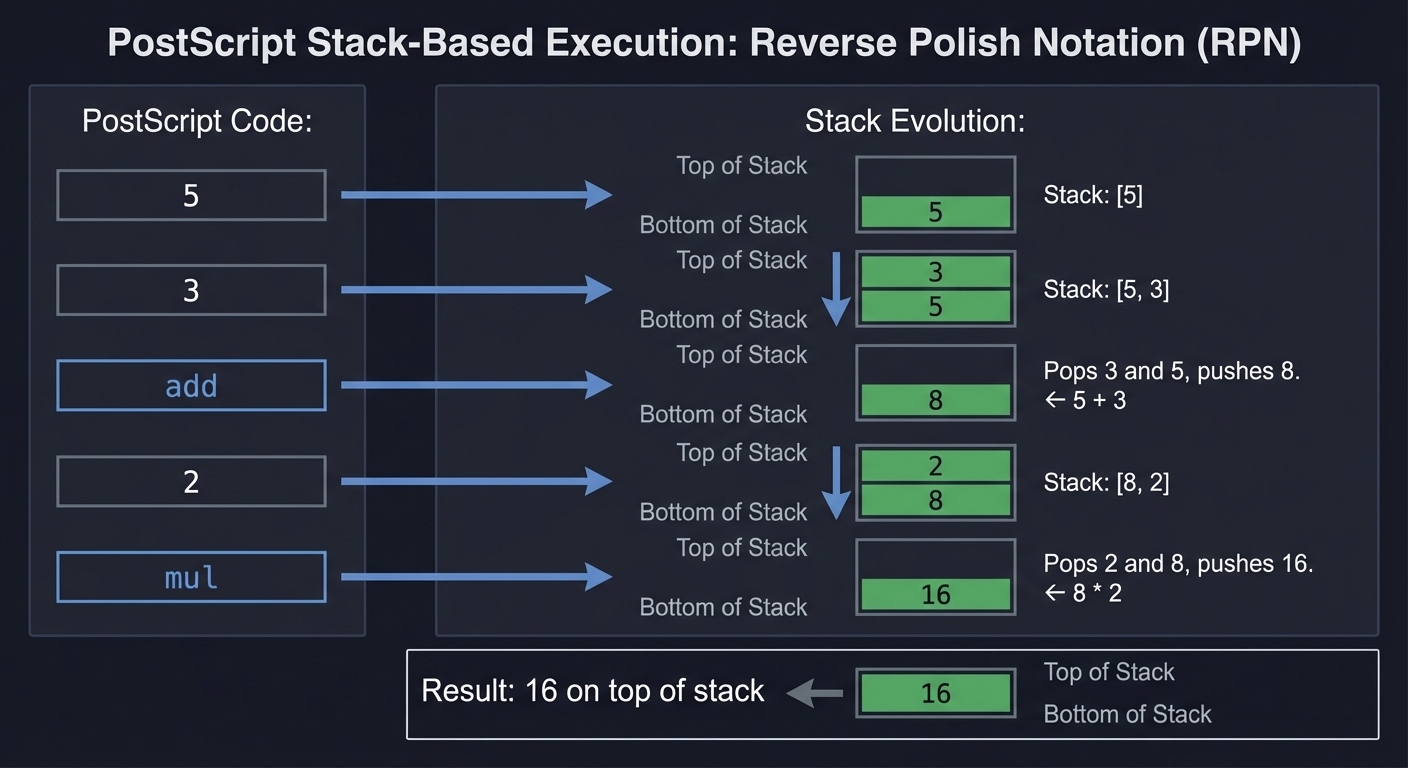

The Stack-Based Execution Model: PostScript’s Secret Weapon

PostScript uses Reverse Polish Notation (RPN) like old HP calculators. Instead of (5 + 3) * 2, you write 5 3 add 2 mul:

PostScript Code: Stack Evolution:

5 [5]

3 [5, 3]

add [8] ← 5 + 3

2 [8, 2]

mul [16] ← 8 * 2

Result: 16 on top of stack

Why is this powerful for graphics?

Drawing a line from (0,0) to (100,100):

Traditional (C-like):

drawLine(0, 0, 100, 100);

PostScript:

0 0 moveto ← Push 0, push 0, move current point

100 100 lineto ← Push 100, push 100, add line to path

stroke ← Actually draw the path

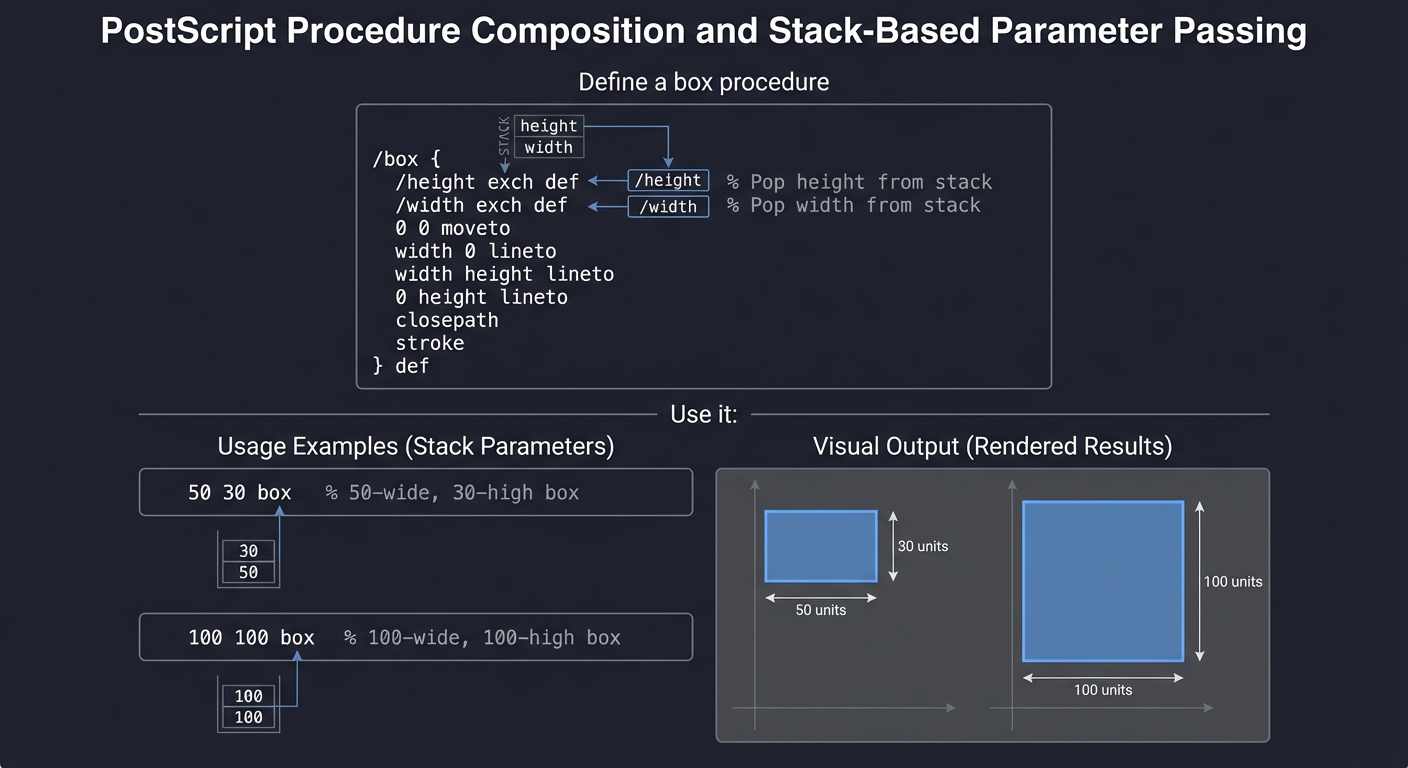

The stack makes composition natural:

% Define a box procedure

/box {

/height exch def % Pop height from stack

/width exch def % Pop width from stack

0 0 moveto

width 0 lineto

width height lineto

0 height lineto

closepath

stroke

} def

% Use it:

50 30 box % 50-wide, 30-high box

100 100 box % 100-wide, 100-high box

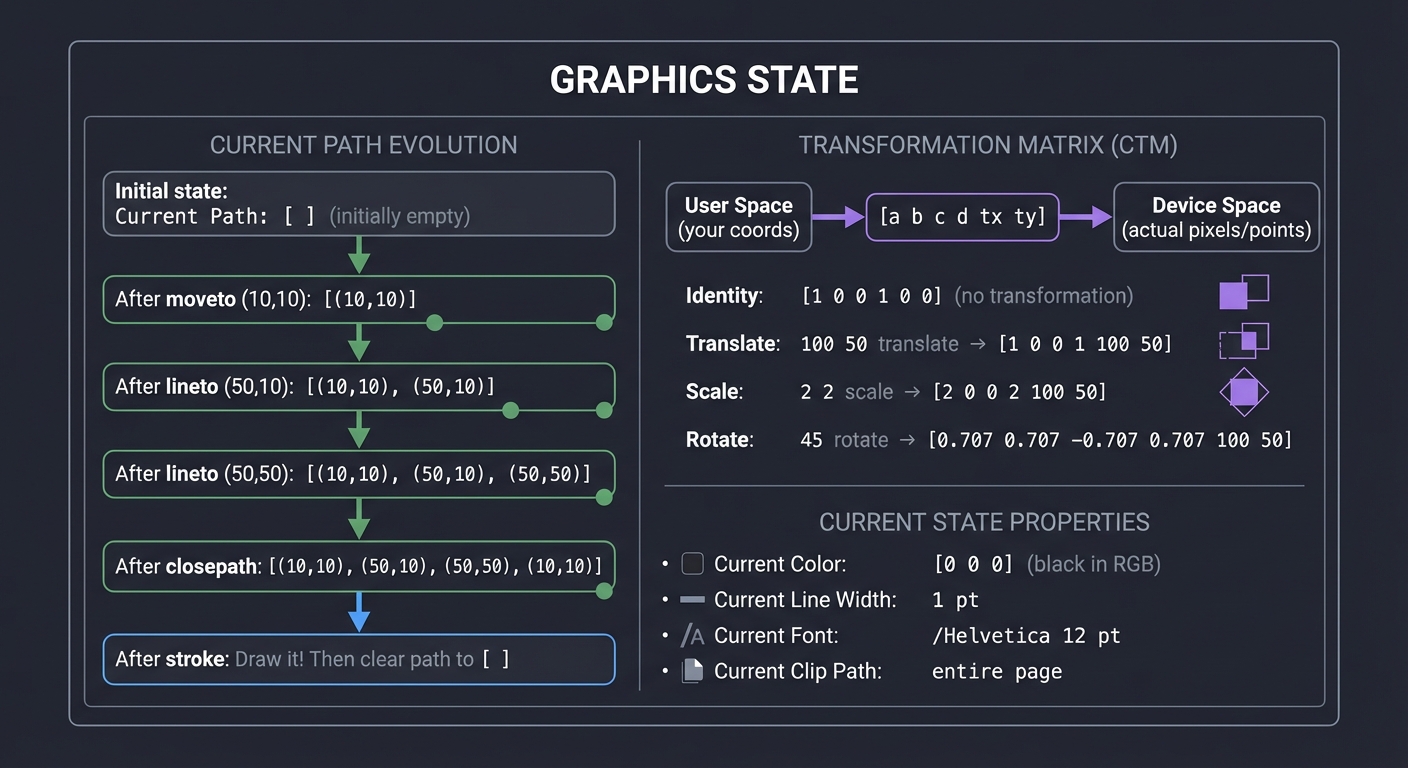

The Graphics State Machine: How Drawing Actually Works

PostScript maintains a graphics state that tracks everything about “how to draw”:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ GRAPHICS STATE │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ Current Path: [ ] (initially empty) │

│ ↓ │

│ moveto (10,10) → [(10,10)] │

│ lineto (50,10) → [(10,10), (50,10)] │

│ lineto (50,50) → [(10,10), (50,10), (50,50)] │

│ closepath → [(10,10), (50,10), (50,50), (10,10)] │

│ stroke → Draw it! Then clear path to [ ] │

│ │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ Transformation Matrix (CTM): │

│ │

│ User Space Device Space │

│ (your coords) (actual pixels/points) │

│ │ │

│ └──> [a b c d tx ty] ──> (transformed coords) │

│ │

│ Identity: [1 0 0 1 0 0] (no transformation) │

│ Translate: 100 50 translate → [1 0 0 1 100 50] │

│ Scale: 2 2 scale → [2 0 0 2 100 50] │

│ Rotate: 45 rotate → [0.707 0.707 -0.707 0.707 100 50] │

│ │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ Current Color: [0 0 0] (black in RGB) │

│ Current Line Width: 1 pt │

│ Current Font: /Helvetica 12 pt │

│ Current Clip Path: entire page │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

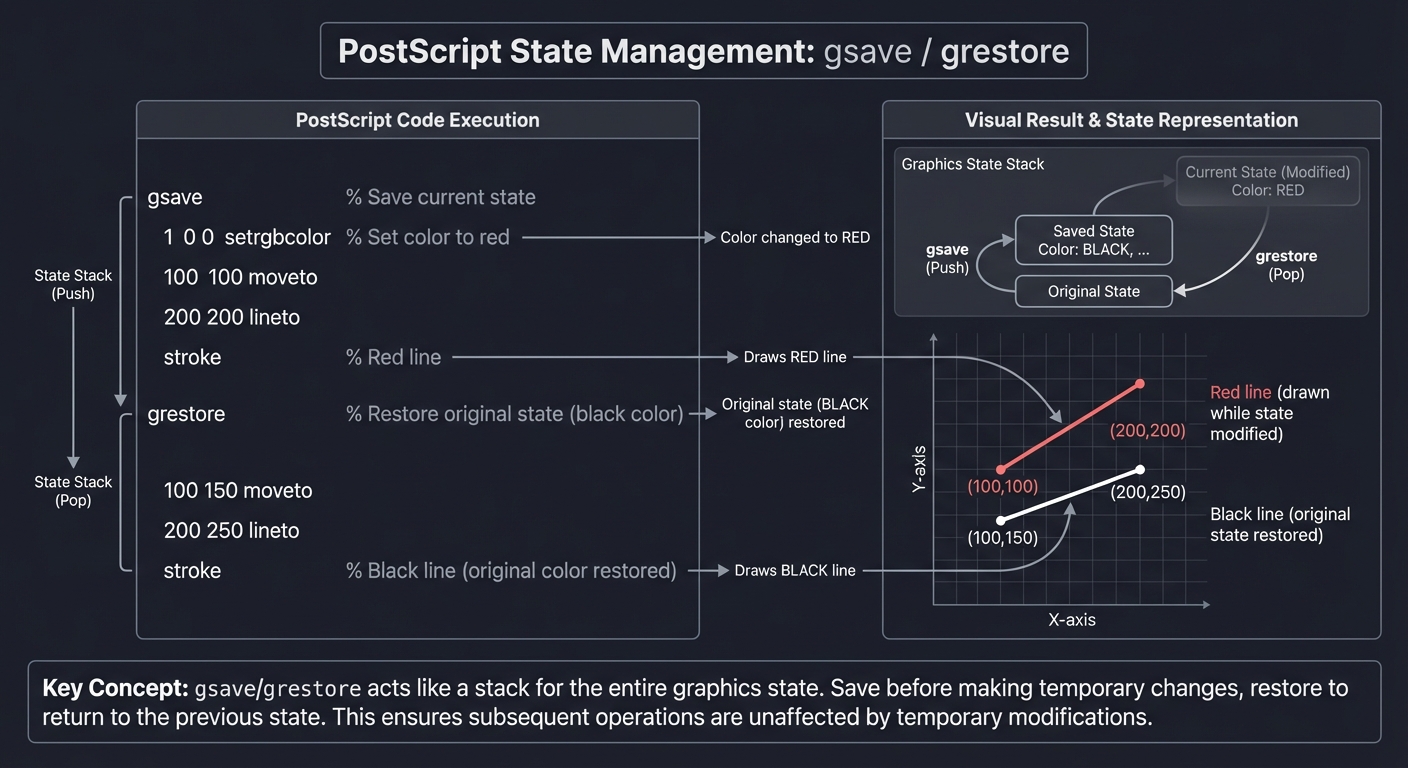

Critical insight: You can save/restore the entire state with gsave/grestore:

gsave % Save current state

1 0 0 setrgbcolor % Set color to red

100 100 moveto

200 200 lineto

stroke % Red line

grestore % Restore original state (black color)

100 150 moveto

200 250 lineto

stroke % Black line (original color restored)

From PostScript (Executable) to PDF (Static)

The fundamental difference:

| Aspect | PostScript | |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Programming language (Turing-complete) | Data format (not executable) |

| Execution | Interpreted at runtime | Parsed and rendered |

| Page Order | Can compute pages dynamically | Pages are numbered objects |

| File Structure | Sequential commands | Random-access object graph |

| Loops | for, repeat, loop |

Not allowed |

| Conditionals | if, ifelse |

Not allowed |

| Use Case | Generate complex documents programmatically | Distribute final documents reliably |

PostScript example (dynamic):

% Draw 10 concentric circles

0 10 90 { % Loop from 0 to 90, step 10

0 0 moveto % Start at center

0 360 arc % Draw circle with radius from loop

stroke

} for

PDF equivalent (static):

% You must explicitly specify each circle:

0 0 m 0 0 10 0 360 arc S % Circle radius 10

0 0 m 0 0 20 0 360 arc S % Circle radius 20

0 0 m 0 0 30 0 360 arc S % Circle radius 30

% ... repeat for each circle

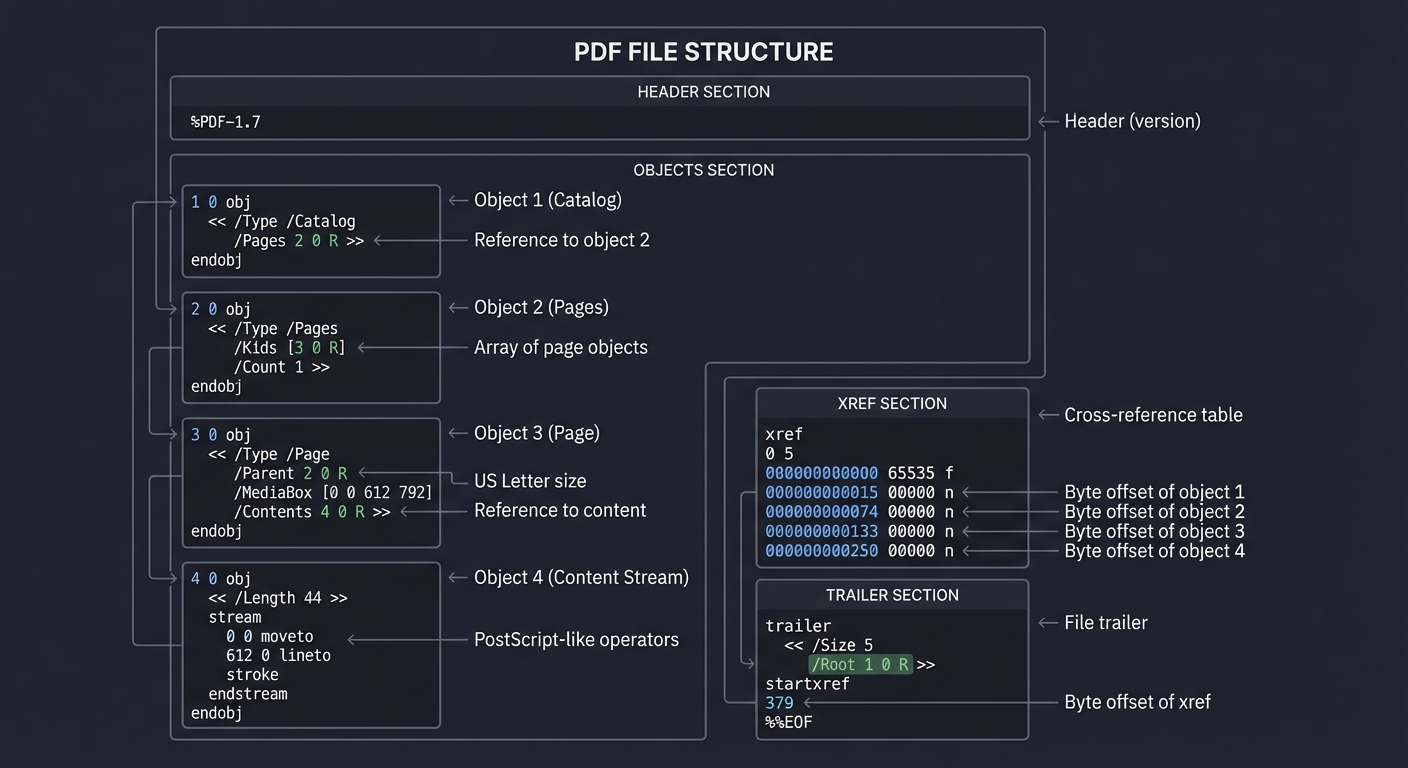

PDF’s Object Structure: The Building Blocks

PDF files are collections of numbered objects:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ PDF FILE STRUCTURE │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ %PDF-1.7 ← Header (version) │

│ │

│ 1 0 obj ← Object 1 (Catalog) │

│ << /Type /Catalog │

│ /Pages 2 0 R >> ← Reference to object 2 │

│ endobj │

│ │

│ 2 0 obj ← Object 2 (Pages) │

│ << /Type /Pages │

│ /Kids [3 0 R] ← Array of page objects │

│ /Count 1 >> │

│ endobj │

│ │

│ 3 0 obj ← Object 3 (Page) │

│ << /Type /Page │

│ /Parent 2 0 R │

│ /MediaBox [0 0 612 792] ← US Letter size │

│ /Contents 4 0 R >> ← Reference to content │

│ endobj │

│ │

│ 4 0 obj ← Object 4 (Content Stream) │

│ << /Length 44 >> │

│ stream │

│ 0 0 moveto ← PostScript-like operators │

│ 612 0 lineto │

│ stroke │

│ endstream │

│ endobj │

│ │

│ xref ← Cross-reference table │

│ 0 5 │

│ 0000000000 65535 f │

│ 0000000015 00000 n ← Byte offset of object 1 │

│ 0000000074 00000 n ← Byte offset of object 2 │

│ 0000000133 00000 n ← Byte offset of object 3 │

│ 0000000250 00000 n ← Byte offset of object 4 │

│ │

│ trailer ← File trailer │

│ << /Size 5 │

│ /Root 1 0 R >> │

│ startxref │

│ 379 ← Byte offset of xref │

│ %%EOF │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Key insight: The xref table makes PDF random access—you can jump directly to any page without reading the entire file. PostScript requires sequential interpretation.

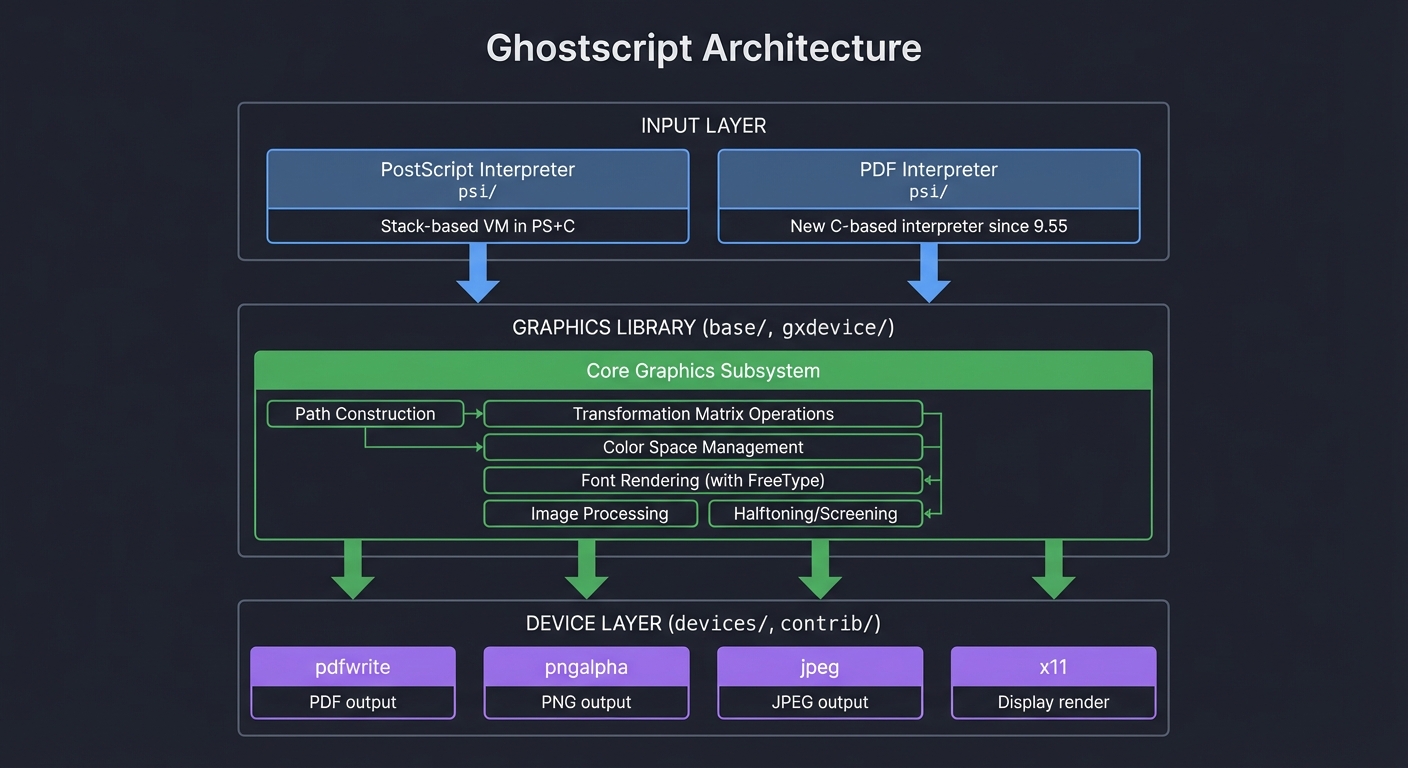

Why Ghostscript Exists: The Transformation Engine

Ghostscript solves multiple problems:

- PostScript Rendering: Execute

.psfiles and render to screen/printer/image - PostScript to PDF: Convert executable PostScript to static PDF (

ps2pdf) - PDF Rendering: Render PDF files to images or printers

- Format Conversion: PDF ↔ PostScript ↔ PNG/JPEG/etc.

Ghostscript’s architecture:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ GHOSTSCRIPT │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ ┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ INPUT LAYER │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ PostScript Interpreter │ PDF Interpreter (new!) │ │

│ │ (PS + C code) │ (pure C, fast) │ │

│ └──────────────────────┬───────────────┬─────────────┘ │

│ │ │ │

│ └───────┬───────┘ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ GRAPHICS LIBRARY │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ • Path construction │ │

│ │ • Transformation matrix ops │ │

│ │ • Color space management │ │

│ │ • Font rendering │ │

│ │ • Image processing │ │

│ └──────────────────────┬─────────────────────────────┘ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ OUTPUT DEVICES │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ pdfwrite │ pngalpha │ jpeg │ pswrite │... │ │

│ │ (PDF) │ (PNG) │ (JPEG) │ (PS) │ │ │

│ └────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

└─────────────────────────┼────────────────────────────────────────┘

▼

Output File

How ps2pdf works internally:

- Parse PostScript program

- Execute it (run the stack-based VM)

- Graphics library captures all drawing operations

pdfwritedevice converts operations to PDF objects- Write PDF file with xref table

Historical Context: Why These Formats Won

1984: PostScript invented

- Problem: Every printer manufacturer had their own protocol

- Solution: Universal programming language for printing

- Impact: Desktop publishing revolution (Macintosh + LaserWriter)

1993: PDF invented

- Problem: PostScript is complex, files are large, can’t random-access pages

- Solution: “PostScript without the programming” + compression + xref table

- Impact: Universal document exchange (replaced fax, standardized forms)

1988-present: Ghostscript

- Problem: PostScript interpreters were proprietary and expensive

- Solution: Open-source implementation

- Impact: Enabled Linux printing, free PDF generation, document conversion

2021: Ghostscript 9.55 - Major rewrite

- Problem: PDF interpreter written in PostScript was slow and had security issues

- Solution: Rewrite PDF interpreter in pure C

- Impact: 2-3x faster PDF rendering, better security

Core Concept Analysis

To truly understand PDF generation from PostScript via Ghostscript, you need to grasp:

| Concept | What It Is |

|---|---|

| PostScript | A Turing-complete stack-based programming language for describing pages (text, graphics, images) |

| A document format derived from PostScript but with a fixed structure (not a programming language) | |

| Ghostscript | An interpreter that executes PostScript programs and can output to various formats including PDF |

| Page Description | How vector graphics, fonts, and images are mathematically described |

| Rendering Pipeline | How abstract descriptions become rasterized pixels or structured documents |

The key insight: PostScript is a program that draws; PDF is a static snapshot of what was drawn.

Concept Summary Table

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize |

|---|---|

| Stack-based execution | PostScript is a stack machine. Every operation pops arguments from the stack and pushes results. Understanding this is understanding how PostScript executes. |

| Graphics state machine | Drawing operations modify state (current path, transformation matrix, color, font). gsave/grestore save/restore entire state. This is the core of how graphics work. |

| Transformation matrix (CTM) | All coordinates pass through a 2D transformation matrix. Understanding translate, scale, rotate, concat is understanding how coordinate systems work. |

| PostScript as language | PostScript is Turing-complete with procedures, conditionals, loops. It’s not just “data”—it’s executable code that generates graphics. |

| PDF object graph | PDF is a collection of numbered objects with references between them. The xref table enables random access. This structure makes PDFs fast to navigate. |

| Content streams | PDF pages contain content streams—sequences of PostScript-like operators. The operators are almost identical to PostScript but in a static, non-executable context. |

| PS→PDF transformation | Converting PostScript to PDF means executing the program, capturing all drawing operations, and serializing them as PDF objects. Ghostscript’s pdfwrite device does this. |

| Document structure vs rendering | PostScript mixes computation and rendering. PDF separates structure (objects, pages) from rendering (content streams). This is why PDF is better for distribution. |

| Binary file parsing | PDF files are binary with ASCII markers. Understanding byte offsets, xref tables, and stream compression is essential for PDF manipulation. |

| Device abstraction | Ghostscript’s architecture separates interpreters (PS/PDF) from graphics library from output devices. This design enables supporting many output formats from one codebase. |

Deep Dive Reading by Concept

This section maps each concept to specific book chapters. Read these before or alongside projects to build strong mental models.

PostScript Language Fundamentals

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Stack-based execution model | Language Implementation Patterns by Terence Parr — Ch. 3: “Enhanced Tree Walkers” (section on stack-based execution) |

| PostScript syntax and operators | PostScript Language Tutorial and Cookbook (Blue Book) by Adobe — Ch. 1-3: “A First Session”, “Types, Operators, and the Stack” |

| Reverse Polish Notation | The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 1 by Donald Knuth — Section 2.2.1: “Stacks” |

| Implementing interpreters | Language Implementation Patterns by Terence Parr — Ch. 9: “Bytecode Assemblers and Interpreters” |

| Stack machines fundamentals | Low-Level Programming by Igor Zhirkov — Ch. 7: “General-Purpose Computation on Stack” |

Graphics and Rendering

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| 2D graphics fundamentals | Computer Graphics from Scratch by Gabriel Gambetta — Ch. 1-3: “Lines”, “Filled Triangles”, “Shaded Triangles” |

| Transformation matrices | Computer Graphics from Scratch by Gabriel Gambetta — Ch. 4: “Perspective Projection” (2D matrix operations) |

| Vector graphics rendering | Computer Graphics from Scratch by Gabriel Gambetta — Ch. 1: “Introductory Concepts” |

| Coordinate systems | Mathematical Illustrations by Bill Casselman — Ch. 4: “Coordinates and conditionals in PostScript” |

| Path construction | PostScript Language Reference Manual by Adobe — Ch. 4: “Graphics” (path operators) |

PDF Structure and Parsing

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| PDF file structure | Developing with PDF by Leonard Rosenthol — Ch. 1: “PDF Syntax” |

| Binary file parsing | Practical Binary Analysis by Dennis Andriesse — Ch. 2: “The ELF Format” (general principles apply to PDF) |

| Object graph structures | Domain Specific Languages by Martin Fowler — Ch. 26: “Serialization” |

| Cross-reference tables | PDF Reference Manual 1.7 by Adobe — Section 3.4: “File Structure” |

| Stream compression | Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective by Bryant & O’Hallaron — Ch. 6: “The Memory Hierarchy” (compression algorithms) |

Document Processing Architecture

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Pipeline architecture | Language Implementation Patterns by Terence Parr — Ch. 2: “Building Recursive-Descent Parsers” |

| Device abstraction layers | Working Effectively with Legacy Code by Michael Feathers — Ch. 25: “Dependency-Breaking Techniques” |

| Code generation | Engineering a Compiler by Cooper & Torczon — Ch. 7: “Code Generation” |

| Interpreter design | Language Implementation Patterns by Terence Parr — Ch. 3: “Enhanced Tree Walkers” |

| System architecture | Software Architecture in Practice by Bass, Clements & Kazman — Ch. 13: “Pipe-and-Filter Architecture” |

Language Implementation

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Virtual machines | Language Implementation Patterns by Terence Parr — Ch. 9: “Bytecode Assemblers and Interpreters” |

| Symbol tables and scoping | Engineering a Compiler by Cooper & Torczon — Ch. 5: “Symbol Tables” |

| Lexing and parsing | Language Implementation Patterns by Terence Parr — Ch. 2: “Building Recursive-Descent Parsers” |

| Domain-specific languages | Domain Specific Languages by Martin Fowler — Ch. 1-3: “An Introductory Example”, “Using Domain-Specific Languages” |

Systems Programming Foundations

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| C systems programming | 21st Century C by Ben Klemens — Ch. 6: “Your Pal the Pointer” |

| Working with large codebases | Working Effectively with Legacy Code by Michael Feathers — Ch. 16: “I Don’t Understand the Code Well Enough to Change It” |

| Data structures for graphics | C Interfaces and Implementations by David Hanson — Ch. 11: “Sequences” & Ch. 13: “Strings” |

| Memory management | The C Programming Language by Kernighan & Ritchie — Ch. 8: “The UNIX System Interface” |

Essential Reading Order

For maximum comprehension, read in this sequence:

- PostScript Foundations (Week 1):

- PostScript Language Tutorial and Cookbook Ch. 1-3 (understand the language)

- Language Implementation Patterns Ch. 3 (understand stack-based execution)

- Computer Graphics from Scratch Ch. 1-3 (understand 2D graphics)

- PDF Structure (Week 2):

- Developing with PDF Ch. 1 (understand PDF file format)

- PDF Reference Manual 1.7 Section 3.4 (understand xref tables)

- Practical Binary Analysis Ch. 2 (general binary parsing principles)

- Transformation Pipeline (Week 3):

- Engineering a Compiler Ch. 7 (code generation concepts)

- Language Implementation Patterns Ch. 9 (interpreter implementation)

- Domain Specific Languages Ch. 1-3 (DSL design principles)

- Production Implementation (Week 4+):

- Working Effectively with Legacy Code Ch. 16 (reading Ghostscript source)

- Software Architecture in Practice Ch. 13 (pipeline architecture)

- 21st Century C Ch. 6 (C programming for systems)

Project 1: PostScript Subset Interpreter

- File: POSTSCRIPT_PDF_GHOSTSCRIPT_LEARNING_PROJECTS.md

- Programming Language: C

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 3. The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Interpreters / Graphics

- Software or Tool: PostScript

- Main Book: “PostScript Language Tutorial and Cookbook” (Blue Book) by Adobe

What you’ll build: A minimal interpreter that executes a subset of PostScript (stack operations, basic drawing commands) and outputs to SVG or PNG.

Why it teaches PostScript→PDF: You’ll understand that PostScript is executed to produce graphics. Every moveto, lineto, stroke is an instruction your interpreter runs. This is exactly what Ghostscript does before converting to PDF.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Implementing a stack-based virtual machine (maps to understanding PostScript’s execution model)

- Parsing and tokenizing PostScript syntax (maps to language processing)

- Tracking graphics state (current point, transformation matrix, color) (maps to how PDF stores page content)

- Converting drawing operations to output format (maps to the PS→PDF conversion process)

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 2-3 weeks Prerequisites: Basic parsing concepts, understanding of coordinate systems

Real world outcome:

- You’ll be able to feed simple

.psfiles to your interpreter and see rendered output (PNG/SVG) - You can visualize the execution step-by-step, showing the stack state and drawing operations

Key Concepts:

- Stack-based VMs: “The Art of Computer Programming, Vol 1” Ch. 2.2.1 - Donald Knuth (stack fundamentals)

- PostScript Language: “PostScript Language Tutorial and Cookbook” (Blue Book) - Adobe (free PDF online)

- Graphics State Machines: “Computer Graphics from Scratch” Ch. 1-3 - Gabriel Gambetta

Learning milestones:

- Execute basic stack operations (

push,pop,dup,exch) - understand PS is just a stack machine - Implement path construction (

moveto,lineto,curveto,stroke,fill) - understand how shapes are described - Handle coordinate transformations (

translate,scale,rotate) - understand the transformation matrix - Output to SVG/PNG - see PostScript execution produce real graphics

Real World Outcome

When you complete this project, you’ll have a working PostScript interpreter that you can actually use in production. Here’s exactly what you’ll see and be able to do:

Running Your Interpreter: The Complete Experience

Basic execution with verbose output:

$ ./ps_interpreter simple_shape.ps output.svg

PostScript Subset Interpreter v1.0

================================

Loading: simple_shape.ps

File size: 147 bytes

Parsing tokens... 74 tokens found

Executing PostScript program...

Stack trace (top = rightmost):

Step 1: newpath → Stack: []

Step 2: 100 → Stack: [100]

Step 3: 100 → Stack: [100, 100]

Step 4: moveto → Stack: []

Step 5: 300 → Stack: [300]

Step 6: 100 → Stack: [300, 100]

Step 7: lineto → Stack: []

Step 8: 200 → Stack: [200]

Step 9: 300 → Stack: [200, 300]

Step 10: lineto → Stack: []

Step 11: closepath → Stack: []

Step 12: 0.5 → Stack: [0.5]

Step 13: setgray → Stack: []

Step 14: fill → Stack: []

Execution complete. Total operations: 14

Graphics State Summary:

- Path segments: 4 (3 lines + 1 closepath)

- Drawing operations: 1 fill

- Current point: (100.0, 100.0)

- Current color: RGB(0.5, 0.5, 0.5) [gray]

- Transformation matrix: [1.000 0.000 0.000 1.000 0.000 0.000]

- Clipping path: none (full page)

Output written to: output.svg (842 bytes)

Rendering time: 0.003s

The input PostScript file (simple_shape.ps):

%!PS-Adobe-3.0

% Draw a simple triangle

newpath

100 100 moveto

300 100 lineto

200 300 lineto

closepath

0.5 setgray

fill

showpage

What You Can Actually Visualize

1. SVG Output - See Your Graphics Rendered

Open output.svg in any browser (Chrome, Firefox, Safari) and see:

- A filled gray triangle with vertices at (100,100), (300,100), and (200,300)

- Coordinates in PostScript’s coordinate system (origin at bottom-left)

- Exact color matching (0.5 gray = RGB(127, 127, 127))

The SVG file contains:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" width="612" height="792" viewBox="0 0 612 792">

<!-- PostScript coordinate system: Y grows upward -->

<path d="M 100 692 L 300 692 L 200 492 Z"

fill="rgb(127, 127, 127)"

stroke="none"/>

</svg>

Note: Y-coordinate flipped because SVG has origin at top-left (792 - 100 = 692)

2. Step-by-step Execution Trace - Watch the Stack Evolve

Add --trace flag to see every operation in detail:

$ ./ps_interpreter --trace triangle.ps output.svg

=== PostScript Execution Trace ===

[Token 1] 'newpath'

Type: operator

Stack before: []

Stack after: []

Graphics state change:

- Current path cleared

- Path segments: 0

[Token 2] '100'

Type: number (integer)

Stack before: []

Stack after: [100]

Graphics state: no change

[Token 3] '100'

Type: number (integer)

Stack before: [100]

Stack after: [100, 100]

Graphics state: no change

[Token 4] 'moveto'

Type: operator

Pops: y=100, x=100

Stack before: [100, 100]

Stack after: []

Graphics state change:

- Current point: (100.0, 100.0)

- Path: M 100.0 100.0

- Path segments: 1

[Token 5] '300'

Type: number (integer)

Stack before: []

Stack after: [300]

Graphics state: no change

[Token 6] '100'

Type: number (integer)

Stack before: [300]

Stack after: [300, 100]

Graphics state: no change

[Token 7] 'lineto'

Type: operator

Pops: y=100, x=300

Stack before: [300, 100]

Stack after: []

Graphics state change:

- Current point: (300.0, 100.0)

- Path: M 100.0 100.0 L 300.0 100.0

- Path segments: 2

[Token 8] '200'

Type: number (integer)

Stack before: []

Stack after: [200]

Graphics state: no change

[Token 9] '300'

Type: number (integer)

Stack before: [200]

Stack after: [200, 300]

Graphics state: no change

[Token 10] 'lineto'

Type: operator

Pops: y=300, x=200

Stack before: [200, 300]

Stack after: []

Graphics state change:

- Current point: (200.0, 300.0)

- Path: M 100.0 100.0 L 300.0 100.0 L 200.0 300.0

- Path segments: 3

[Token 11] 'closepath'

Type: operator

Stack before: []

Stack after: []

Graphics state change:

- Path closed: adds line from (200.0, 300.0) to (100.0, 100.0)

- Path: M 100.0 100.0 L 300.0 100.0 L 200.0 300.0 Z

- Path segments: 4

[Token 12] '0.5'

Type: number (real)

Stack before: []

Stack after: [0.5]

Graphics state: no change

[Token 13] 'setgray'

Type: operator

Pops: gray=0.5

Stack before: [0.5]

Stack after: []

Graphics state change:

- Color: RGB(0.5, 0.5, 0.5)

- Previous color: RGB(0.0, 0.0, 0.0)

[Token 14] 'fill'

Type: operator

Stack before: []

Stack after: []

Graphics state change:

- Filled path with current color RGB(0.5, 0.5, 0.5)

- Current path CLEARED (important!)

- Path segments: 0

=== Execution Complete ===

Total tokens: 14

Final stack depth: 0 (stack is empty - correct!)

3. PNG Rendering - Actual Rasterized Images

Use Cairo or libpng to output actual bitmap images:

$ ./ps_interpreter --format png --width 500 --height 500 triangle.ps triangle.png

Rendering to PNG...

Canvas size: 500x500 pixels

DPI: 72 (default)

Background: white

Anti-aliasing: enabled

Rasterizing path...

Triangle vertices: (100,100), (300,100), (200,300)

Fill color: gray (0.5)

Writing PNG...

Done. File size: 3,247 bytes

You can now open triangle.png in any image viewer.

4. Interactive REPL Mode - Experiment Live

Run your interpreter interactively to test operators:

$ ./ps_interpreter --repl

PostScript Subset Interpreter v1.0 - REPL Mode

Type 'quit' to exit, 'stack' to show stack, 'gstate' to show graphics state

PS> 10 20 add

Stack: [30]

PS> dup

Stack: [30, 30]

PS> mul

Stack: [900]

PS> stack

Operand stack (top = rightmost):

[0] 900 (integer)

Stack depth: 1

PS> pop

Stack: []

PS> 100 100 moveto

Graphics state updated.

Current point: (100, 100)

Path: M 100 100

PS> 200 200 lineto

Graphics state updated.

Current point: (200, 200)

Path: M 100 100 L 200 200

PS> stroke

Drawing operation executed: STROKE

Path stroked with current line width (1.0)

Current path cleared.

PS> gstate

Graphics State:

Current point: undefined (no current path)

Transformation matrix: [1.000 0.000 0.000 1.000 0.000 0.000]

Current color: RGB(0.000, 0.000, 0.000) [black]

Line width: 1.0

Line cap: butt

Line join: miter

Path: empty

PS> quit

Goodbye!

What Makes This Impressive

You’re building what professional tools use:

- Ghostscript uses this exact execution model

- Adobe’s RIP (Raster Image Processor) in printers uses this model

- PDF renderers (Poppler, MuPDF) use similar state machines

You can process real PostScript files:

# Generate a PS file from any Linux/macOS application

$ echo "Testing PostScript" | enscript -B -o test.ps

# Run through your interpreter

$ ./ps_interpreter test.ps test.svg

# Compare with Ghostscript's output

$ gs -sDEVICE=svg -o ghostscript_output.svg test.ps

# Visual comparison (both should look identical)

$ open test.svg ghostscript_output.svg

Visualize how PDF converters work:

# Your interpreter shows what ps2pdf sees internally

$ ./ps_interpreter --trace document.ps

# You'll see the exact sequence of operations that become PDF content streams

# This is what Ghostscript does when you run: ps2pdf document.ps

Testing with Complex PostScript

Test with transformations:

$ cat > transform_test.ps << 'EOF'

%!PS-Adobe-3.0

gsave

% Original square

newpath

0 0 moveto

100 0 lineto

100 100 lineto

0 100 lineto

closepath

0 setgray

stroke

grestore

gsave

% Translate and scale

150 150 translate

2 2 scale

newpath

0 0 moveto

100 0 lineto

100 100 lineto

0 100 lineto

closepath

0.5 setgray

fill

grestore

showpage

EOF

$ ./ps_interpreter --trace transform_test.ps transform.svg

You’ll see:

- How

gsave/grestoresave and restore the graphics state - How transformation matrices compose

- Why the second square appears larger and offset

Understanding the Graphics State Machine

After completing this project, you’ll viscerally understand:

1. Stack-based execution is simple but powerful:

- No operator precedence rules

- Natural for building graphics incrementally

- Easy to implement (just push/pop data structures)

2. Graphics state is separate from operand stack:

- Operand stack: temporary calculation values

- Graphics state: current point, color, transformation matrix, path

- This separation is why

strokecan clear the path but not affect the stack

3. Path construction vs. path painting:

moveto,lineto,curveto,closepath→ build the pathstroke,fill→ paint the path (and clear it!)- You can build complex paths incrementally, then paint once

4. Why PDF is “frozen PostScript”:

- PostScript:

for loop { draw circle }→ executes at rendering time - PDF: must pre-compute and store each circle as static data

- Your interpreter shows why PDF files are larger but faster to display

The “Aha!” Moment

When you run this:

$ ./ps_interpreter --trace

PS> 5 3 add 2 mul

You’ll see:

[5] → [5, 3] → [8] → [8, 2] → [16]

And realize: This is exactly how Python, Java, and all stack-based VMs work internally. You’ve built a real virtual machine.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“What does it mean for a programming language to ‘draw’? How can code become graphics?”

This is profound because most developers think of programs as producing text output or manipulating data. PostScript inverts this: the language itself IS the graphics. There’s no separation between “code” and “image” - executing the code creates the image.

When you write:

100 100 moveto

200 200 lineto

stroke

You’re not describing a line. You’re not telling some other program to draw a line. You’re executing instructions that move a virtual pen and paint pixels. The language runtime maintains a graphics state machine.

This mental model is critical because:

- Every graphics API works this way: OpenGL, Canvas, Cairo, DirectX - they’re all state machines influenced by PostScript

- PDF is frozen PostScript: Understanding execution → static representation is how you understand PS→PDF conversion

- Interpreters aren’t magic: You’ll see that “running code” just means “updating state based on instructions”

By the end of this project, you’ll internalize: Graphics are state + operations, not static data.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Stack-Based Execution Model

- What does “stack-based” mean for a programming language?

- How is this different from register-based VMs (like the JVM’s evolution)?

- Why did PostScript choose a stack model? (Hint: 1982 hardware constraints)

- What operations must every stack-based VM support? (push, pop, dup, exch, roll)

- Book Reference: “Low-Level Programming” by Igor Zhirkov — Ch. 9: “Stack Machine” sections

- Online Reference: “Virtual Machine Showdown: Stack Versus Registers” by Yunhe Shi (academic paper)

- Reverse Polish Notation (RPN)

- Why does PostScript use

2 3 addinstead ofadd(2, 3)? - How does RPN eliminate the need for parentheses?

- What’s the relationship between RPN and stack machines?

- Practice: Convert

(5 + 3) * 2to RPN:5 3 add 2 mul - Book Reference: “The Art of Computer Programming, Vol 1” by Donald Knuth — §2.2.1 (Stack usage in expression evaluation)

- Why does PostScript use

- Graphics State Machine

- What is “graphics state”? (Current point, transformation matrix, color, line width, etc.)

- Why must rendering systems maintain state?

- What operations modify state vs. query state vs. use state?

- How does

gsave/grestorework? (Stack of graphics states!) - Book Reference: “Computer Graphics from Scratch” by Gabriel Gambetta — Ch. 1-2 (Graphics pipeline fundamentals)

- Coordinate Systems and Transformations

- What is a transformation matrix?

- How do

translate,scale, androtatecompose? - Why is matrix multiplication order critical? (

translate(10,0)thenscale(2)≠scale(2)thentranslate(10,0)) - What does the identity matrix

[1 0 0 1 0 0]mean in PostScript? - Book Reference: “Computer Graphics from Scratch” by Gabriel Gambetta — Ch. 4: “Coordinate Systems and Transformations”

- Path Construction vs. Path Painting

- What’s the difference between building a path and rendering it?

- Why separate

moveto/lineto(construction) fromstroke/fill(painting)? - What happens to the current path after

stroke? (It’s cleared!) - How do subpaths work? (

movetowithoutclosepath) - Book Reference: “PostScript Language Tutorial and Cookbook” (Blue Book) — Adobe Systems, Ch. 3

- Tokenization and Parsing

- How do you split PostScript into tokens? (Whitespace, delimiters like

{}[]) - What’s the difference between executable names (

moveto) and literal names (/moveto)? - How are strings delimited? (

(Hello World)) - What are procedures? (

{ 100 100 moveto 200 200 lineto stroke }) - Book Reference: “Engineering a Compiler” by Cooper & Torczon — Ch. 2: “Lexical Analysis”

- How do you split PostScript into tokens? (Whitespace, delimiters like

- Vector Graphics vs. Raster Graphics

- What does it mean to describe graphics mathematically?

- How do you convert a vector path to pixels? (Rasterization)

- Why is SVG output easier than PNG output for this project?

- What is antialiasing and when does it matter?

- Book Reference: “Computer Graphics from Scratch” by Gabriel Gambetta — Ch. 6: “Rasterization”

Self-assessment questions:

- Can you implement a stack data structure with push/pop/dup/exch in C?

- Can you parse

3 4 add 2 mulinto tokens and evaluate it using a stack? - Do you know what a 2D transformation matrix looks like?

- Have you written a tokenizer/lexer before?

If you answered “no” to any of these, stop and study those concepts first. The project will be frustrating without these foundations.

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Interpreter Architecture

- How will you represent the data stack? (array? linked list?)

- What types can be on the stack? (numbers, strings, arrays, procedures, names)

- How will you map PostScript names to C functions? (function pointer table? hash map?)

- Should you use a dictionary stack for variable lookups?

- Token Processing

- Will you tokenize all at once or stream tokens?

- How do you handle comments? (

%to end-of-line) - How do you distinguish numbers from names? (regex? character checks?)

- What about nested procedures? (

{ { inner } outer })

- Graphics State Management

- How do you represent the current path? (array of points? linked list of segments?)

- Where do you store current color, line width, transformation matrix?

- How will you implement

gsave/grestore? (stack of structs?) - What’s the default graphics state when your interpreter starts?

- Rendering Backend

- Will you output to SVG (text-based, easy) or PNG (binary, requires library)?

- For SVG: How do you convert PostScript paths to SVG path syntax?

- For PNG: Which library? (Cairo? libpng? stb_image_write?)

- How do you handle coordinate system differences? (PostScript: origin bottom-left, SVG: origin top-left)

- Operator Implementation Priority

- Which operators are essential for a minimal demo? (

moveto,lineto,stroke,fill) - Which operators can you defer? (

arc,curveto,clip,image) - How will you handle unimplemented operators gracefully?

- Which operators are essential for a minimal demo? (

- Error Handling

- What happens if the stack underflows? (

3 addwith empty stack) - What if an operator gets wrong types? (

movetoneeds two numbers) - Should you have a “verbose mode” for debugging?

- What happens if the stack underflows? (

- Testing Strategy

- How will you test each operator in isolation?

- What simple PostScript programs will verify correctness?

- Can you generate reference outputs from Ghostscript for comparison?

Key insight to internalize: Your interpreter is a loop: read token → execute operator → update state → repeat. Everything else is just details of “how to execute” and “what state to track.”

Thinking Exercise

Build the Mental Model on Paper

Before writing a single line of code, do this exercise with pen and paper:

% Simple PostScript program

100 100 moveto

200 100 lineto

200 200 lineto

100 200 lineto

closepath

0.5 setgray

fill

Trace the execution step-by-step:

Create a table like this and fill it out manually:

| Step | Token | Stack Before | Action | Stack After | Graphics State Changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 |

[] |

Push 100 | [100] |

None |

| 2 | 100 |

[100] |

Push 100 | [100, 100] |

None |

| 3 | moveto |

[100, 100] |

Pop y, pop x, move to (x,y) | [] |

Current point = (100, 100), Path = M 100 100 |

| 4 | 200 |

[] |

Push 200 | [200] |

None |

| 5 | 100 |

[200] |

Push 100 | [200, 100] |

None |

| 6 | lineto |

[200, 100] |

Pop y, pop x, line to (x,y) | [] |

Path += L 200 100 |

| … | … | … | … | … | … |

Questions while tracing:

- After

closepath, what does the path look like? (Draw it!) - What’s on the stack before

fillexecutes? - What happens to the path after

fill? (Hint: it’s cleared) - If you added

gsavebeforefillandgrestoreafter, how would that change things?

Draw the graphics state:

Sketch a box showing:

Current Graphics State:

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│ Current Point: (100, 200) │

│ Current Path: M 100 100 │

│ L 200 100 │

│ L 200 200 │

│ L 100 200 │

│ Z │

│ Color: 0.5 (gray) │

│ Transform Matrix: [1 0 0 1 0 0] │

└─────────────────────────────┘

Now simulate a transformation:

gsave

2 2 scale

50 50 moveto

100 100 lineto

stroke

grestore

Trace this and answer:

- What are the actual coordinates rendered? (After applying

scale) - After

grestore, what’s the transformation matrix? (Back to identity) - Why does this matter for understanding PDF? (PDF has the same save/restore model)

The aha moment:

When you manually execute PostScript on paper, you’ll realize: you’re doing exactly what your C program will do. The interpreter is just mechanizing what you’re doing manually.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

When you’ve completed this project, you should be able to confidently answer:

Conceptual Questions:

- “What is PostScript, and why is it Turing-complete?”

- Answer should include: Stack-based language, has loops/conditionals, can compute anything, but designed for graphics

- “Explain how a stack-based language executes

3 4 add 2 mul”- Trace: Push 3 → Push 4 → Pop 4, pop 3, push 7 → Push 2 → Pop 2, pop 7, push 14

- “What’s the difference between building a path and painting a path?”

- Answer:

moveto/linetoconstruct geometry,stroke/fillrasterize it with current color/width

- Answer:

- “Why does PostScript use Reverse Polish Notation?”

- Answer: Natural for stack machines, no need for operator precedence, simpler parser

- “What is the graphics state, and why must it be saved/restored?”

- Answer: Current color, transformation, clip path, etc. Save/restore enables local changes without affecting caller

Technical Questions:

- “How would you implement

dup(duplicate top of stack)?”void ps_dup(Stack* s) { if (s->size == 0) error("Stack underflow"); push(s, s->items[s->size - 1]); } - “What data structure represents a PostScript path?”

- Possible answer: Array of segments, each tagged with type (MOVE, LINE, CURVE, CLOSE)

- “How do you convert PostScript coordinates to SVG?”

- Answer: PostScript origin is bottom-left, SVG is top-left. Transform:

svg_y = page_height - ps_y

- Answer: PostScript origin is bottom-left, SVG is top-left. Transform:

- “What happens if you call

linetowithout a current point?”- Answer: Error - must

movetofirst to establish current point

- Answer: Error - must

- “How would you implement

gsave/grestore?”Stack* gstate_stack; void ps_gsave() { push(gstate_stack, copy(current_gstate)); } void ps_grestore() { current_gstate = pop(gstate_stack); }

Design Questions:

- “Why would you choose SVG output over PNG?”

- Answer: SVG is text-based (easier debugging), lossless, doesn’t require rasterization library

- “How would you debug a PostScript interpreter?”

- Answer: Trace mode (print stack after each op), compare output with Ghostscript, unit test each operator

- “What’s the hardest part of implementing PostScript?”

- Honest answer: Procedures and scoping (dictionary stack), OR font rendering, OR complex paths with curves

Comparison Questions:

- “How is PostScript different from PDF?”

- Answer: PS is executable (Turing-complete), PDF is declarative (frozen state). PS uses operators, PDF has similar operators but in static streams.

- “Why did Adobe create PDF if they already had PostScript?”

- Answer: PS requires interpreter to view (slow, unpredictable). PDF is direct representation (fast, reliable, can jump to pages).

Prepare to draw:

Be ready to draw on a whiteboard:

- Stack state during execution

- Path being constructed

- Transformation matrix application

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with a calculator

Don’t try to build graphics first. Start with a pure stack calculator:

// Minimal PS interpreter: just arithmetic

Stack* stack = stack_new();

while (token = next_token()) {

if (is_number(token)) {

push(stack, atof(token));

} else if (strcmp(token, "add") == 0) {

double b = pop(stack), a = pop(stack);

push(stack, a + b);

} else if (strcmp(token, "mul") == 0) {

double b = pop(stack), a = pop(stack);

push(stack, a * b);

}

}

print_stack(stack); // Show result

Test: echo "3 4 add 2 mul" | ./ps_calc should output 14

Hint 2: Add path construction (no rendering yet)

typedef struct {

double x, y;

} Point;

typedef struct {

Point* points;

int count;

} Path;

Path* current_path = path_new();

Point current_point = {0, 0};

// In your token loop:

else if (strcmp(token, "moveto") == 0) {

current_point.y = pop(stack);

current_point.x = pop(stack);

path_add_move(current_path, current_point);

}

else if (strcmp(token, "lineto") == 0) {

Point p = {pop(stack), pop(stack)};

path_add_line(current_path, p);

current_point = p;

}

Test by printing the path: Path: M 100 100 L 200 200

Hint 3: Output to SVG (text-based, easy to debug)

SVG is just XML. You can generate it with fprintf:

void path_to_svg(Path* path, FILE* out) {

fprintf(out, "<svg xmlns=\"http://www.w3.org/2000/svg\" width=\"500\" height=\"500\">\n");

fprintf(out, " <path d=\"");

for (int i = 0; i < path->count; i++) {

if (path->segments[i].type == MOVE)

fprintf(out, "M %.2f %.2f ", path->segments[i].x, 500 - path->segments[i].y);

else if (path->segments[i].type == LINE)

fprintf(out, "L %.2f %.2f ", path->segments[i].x, 500 - path->segments[i].y);

}

fprintf(out, "\" stroke=\"black\" fill=\"none\"/>\n");

fprintf(out, "</svg>\n");

}

Note the 500 - y coordinate flip!

Hint 4: Use a function pointer table for operators

Instead of giant if-else chains, use a dispatch table:

typedef void (*OperatorFunc)(Interpreter*);

typedef struct {

char* name;

OperatorFunc func;

} Operator;

Operator operators[] = {

{"add", ps_add},

{"mul", ps_mul},

{"moveto", ps_moveto},

{"lineto", ps_lineto},

{"stroke", ps_stroke},

// ... more operators

{NULL, NULL}

};

void execute_operator(Interpreter* interp, char* name) {

for (int i = 0; operators[i].name; i++) {

if (strcmp(operators[i].name, name) == 0) {

operators[i].func(interp);

return;

}

}

fprintf(stderr, "Unknown operator: %s\n", name);

}

Hint 5: Handle colors and stroke/fill

typedef struct {

double r, g, b;

double line_width;

// ... more state

} GraphicsState;

void ps_setgray(Interpreter* interp) {

double gray = pop(interp->stack);

interp->gstate.r = interp->gstate.g = interp->gstate.b = gray;

}

void ps_stroke(Interpreter* interp) {

path_to_svg(interp->current_path, interp->output,

interp->gstate, false); // false = stroke, not fill

path_clear(interp->current_path); // Important!

}

void ps_fill(Interpreter* interp) {

path_to_svg(interp->current_path, interp->output,

interp->gstate, true); // true = fill

path_clear(interp->current_path);

}

Hint 6: Test with real PostScript files

Generate simple test files:

cat > test1.ps << 'EOF'

%!PS-Adobe-3.0

newpath

100 100 moveto

200 200 lineto

stroke

showpage

EOF

./ps_interpreter test1.ps test1.svg

open test1.svg # macOS

# or: firefox test1.svg

Compare with Ghostscript:

gs -sDEVICE=svg -o gs_test1.svg test1.ps

diff test1.svg gs_test1.svg # Won't be identical, but visually similar

Hint 7: Add verbose tracing for debugging

if (interp->verbose) {

printf("Token: '%s'\n", token);

printf("Stack before: ");

print_stack(interp->stack);

execute_operator(interp, token);

printf("Stack after: ");

print_stack(interp->stack);

printf("Current point: (%.2f, %.2f)\n",

interp->current_point.x, interp->current_point.y);

printf("\n");

}

Run with: ./ps_interpreter --verbose test.ps

Hint 8: Study the PostScript Language Reference

Download the “PostScript Language Reference Manual” (3rd edition, the “Red Book”) from Adobe. It’s free as PDF. Look at:

- Chapter 4: Graphics

- Chapter 8: Operators (reference)

- Appendix B: Operators (quick ref)

This is the canonical specification. When in doubt, consult it.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Stack-based virtual machines | “Low-Level Programming” by Igor Zhirkov | Ch. 9: “Virtual Machine” |

| Stack fundamentals | “The Art of Computer Programming, Vol 1” by Donald Knuth | Ch. 2.2.1: “Stacks, Queues, and Deques” |

| PostScript language | “PostScript Language Tutorial and Cookbook” (Blue Book) by Adobe | All chapters (it’s a tutorial) |

| PostScript reference | “PostScript Language Reference Manual” (Red Book) by Adobe | Ch. 4: “Graphics”, Ch. 8: “Operators” |

| Graphics fundamentals | “Computer Graphics from Scratch” by Gabriel Gambetta | Ch. 1-4: “Basic Rendering” |

| Coordinate transformations | “Computer Graphics from Scratch” by Gabriel Gambetta | Ch. 4: “Transformations” |

| Tokenization/parsing | “Engineering a Compiler” by Cooper & Torczon | Ch. 2: “Lexical Analysis” |

| Language implementation | “Language Implementation Patterns” by Terence Parr | Ch. 2: “Tree Grammars”, Ch. 3: “Symbol Tables” |

| Vector to raster conversion | “Computer Graphics from Scratch” by Gabriel Gambetta | Ch. 6: “Rasterization” |

| Real-world interpreter design | “Crafting Interpreters” by Robert Nystrom | Part II: “A Tree-Walk Interpreter” |

| C data structures | “C Interfaces and Implementations” by David Hanson | Ch. 3: “Stacks”, Ch. 4: “Dynamic Arrays” |

| Graphics state machines | “Computer Graphics: Principles and Practice” by Hughes et al. | Ch. 6: “The Graphics Pipeline” |

Reading order for this project:

- Start here: “PostScript Language Tutorial and Cookbook” (Blue Book) - Ch. 1-3 to understand the language

- Implement stack: “C Interfaces and Implementations” - Ch. 3 for a robust stack implementation

- Graphics concepts: “Computer Graphics from Scratch” - Ch. 1-4 before implementing path operations

- Reference during coding: “PostScript Language Reference Manual” (Red Book) - look up each operator as you implement it

Project 2: PDF File Parser & Renderer

- File: POSTSCRIPT_PDF_GHOSTSCRIPT_LEARNING_PROJECTS.md

- Programming Language: C

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 3. The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Document Formats / Compression

- Software or Tool: PDF Structure

- Main Book: “PDF Reference Manual 1.7” by Adobe

What you’ll build: A tool that parses PDF files, extracts their structure, and renders pages to images.

Why it teaches PostScript→PDF: You’ll see that PDF is essentially “frozen PostScript” - the same drawing operations exist, but in a declarative structure rather than executable code. You’ll understand what Ghostscript produces when it converts PS to PDF.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Parsing PDF’s object structure (dictionaries, arrays, streams) (maps to understanding PDF internals)

- Decompressing content streams (Flate, LZW) (maps to how PDF compresses data)

- Interpreting PDF operators (nearly identical to PostScript drawing commands)

- Rendering text with embedded/referenced fonts (maps to font handling complexity)

Difficulty: Intermediate-Advanced Time estimate: 3-4 weeks Prerequisites: Project 1 or equivalent understanding of graphics state

Real world outcome:

- Feed a PDF and get a PNG rendering of each page

- Dump the internal structure showing objects, streams, and cross-references

- Extract and display the raw drawing operators from content streams

Key Concepts:

- PDF Structure: “PDF Reference Manual 1.7” - Adobe (the specification, free)

- Compression Algorithms: “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” Ch. 6 - Bryant & O’Hallaron

- Binary File Parsing: “Practical Binary Analysis” Ch. 2 - Dennis Andriesse

Learning milestones:

- Parse PDF header, xref table, and trailer - understand PDF’s physical structure

- Dereference indirect objects and parse dictionaries - understand PDF’s logical structure

- Decompress and parse content streams - see the PostScript-like operators inside

- Render basic shapes and text to image - complete the pipeline

Real World Outcome

When you complete this project, you’ll have a powerful PDF analysis and rendering tool. Here’s exactly what you’ll be able to do:

Running your PDF parser:

$ ./pdf_parser document.pdf --dump-structure

PDF Parser v1.0

================

File: document.pdf

PDF Version: 1.7

File size: 45,823 bytes

=== HEADER ===

%PDF-1.7

=== CROSS-REFERENCE TABLE ===

Location: byte offset 45650

Objects: 1-25 (25 total)

Object Offset Generation Type

------ ------ ---------- -----

1 15 0 n (in use)

2 74 0 n (in use)

3 133 0 n (in use)

4 250 0 n (in use)

5 0 65535 f (free)

...

=== TRAILER ===

<< /Size 26

/Root 1 0 R

/Info 24 0 R >>

=== DOCUMENT CATALOG (Object 1) ===

<< /Type /Catalog

/Pages 2 0 R

/Metadata 25 0 R >>

=== PAGE TREE (Object 2) ===

<< /Type /Pages

/Kids [3 0 R]

/Count 1 >>

=== PAGE 1 (Object 3) ===

<< /Type /Page

/Parent 2 0 R

/MediaBox [0 0 612 792] % US Letter (8.5" x 11")

/Contents 4 0 R

/Resources << /Font << /F1 10 0 R >> >> >>

=== CONTENT STREAM (Object 4) ===

Stream length: 187 bytes

Filter: /FlateDecode (zlib compression)

Decompressed content:

----------------------------------------

BT % Begin Text

/F1 12 Tf % Set font F1, size 12

72 720 Td % Move to position (72, 720)

(Hello, World!) Tj % Show text

ET % End Text

q % Save graphics state

1 0 0 1 100 600 cm % Translate to (100, 600)

100 0 m % Move to (100, 0)

200 100 l % Line to (200, 100)

200 200 l % Line to (200, 200)

100 200 l % Line to (100, 200)

h % Close path

S % Stroke

Q % Restore graphics state

----------------------------------------

Extracting and visualizing PDF operators:

$ ./pdf_parser document.pdf --extract-operators

Page 1 Operators:

==================

1. BT (Begin Text)

2. /F1 12 Tf (Set Font: F1, Size: 12pt)

3. 72 720 Td (Text Position: x=72, y=720)

4. (Hello, World!) Tj (Show Text: "Hello, World!")

5. ET (End Text)

6. q (Save Graphics State)

7. 1 0 0 1 100 600 cm (Transform Matrix: translate(100, 600))

8. 100 0 m (Move To: 100, 0)

9. 200 100 l (Line To: 200, 100)

10. 200 200 l (Line To: 200, 200)

11. 100 200 l (Line To: 100, 200)

12. h (Close Path)

13. S (Stroke)

14. Q (Restore Graphics State)

Summary:

- Text operations: 4

- Path operations: 6

- State operations: 4

- Total: 14 operators

Rendering PDF to image:

$ ./pdf_parser document.pdf --render output.png

Rendering PDF to PNG...

Page 1: 612x792 pixels

- Decompressing content stream... done

- Parsing operators... 14 found

- Rendering text: "Hello, World!" at (72, 720)

- Drawing rectangle: (100,0)→(200,100)→(200,200)→(100,200)

- Applying stroke

Output written to: output.png (147 KB)

Comparing with industry tools:

# Your tool

$ ./pdf_parser sample.pdf --dump-structure > my_analysis.txt

# Compare with pdfinfo (Poppler)

$ pdfinfo sample.pdf

# Compare with pdftk

$ pdftk sample.pdf dump_data

# Your tool shows MORE detail because you built it!

$ ./pdf_parser sample.pdf --show-bytes

Showing raw bytes of object 4:

Offset 0x0250: 34 20 30 20 6F 62 6A 0A 3C 3C 20 2F 4C 65 6E 67 |4 0 obj.<< /Leng|

Offset 0x0260: 74 68 20 31 38 37 20 2F 46 69 6C 74 65 72 20 2F |th 187 /Filter /|

Offset 0x0270: 46 6C 61 74 65 44 65 63 6F 64 65 20 3E 3E 0A 73 |FlateDecode >>.s|

Offset 0x0280: 74 72 65 61 6D 0A 78 9C ... |tream.x.|

What makes this impressive:

- Deep Understanding: You’ll know PDF structure better than 99% of developers

- Practical Tool: Use it to debug PDF generation issues in your projects

- Security Analysis: Understand how PDF exploits work (malformed objects, zip bombs)

- Format Conversion: Build the foundation for PDF→HTML, PDF→Markdown converters

Real-world use cases:

# Debug why your app generates broken PDFs

$ ./pdf_parser broken_output.pdf --validate

ERROR: Object 15 referenced but not in xref table

ERROR: Stream has declared length 500 but actual length is 327

WARNING: Page MediaBox missing, using default

# Extract embedded files

$ ./pdf_parser document_with_attachments.pdf --list-embedded

Embedded files:

- invoice.xlsx (45 KB, Object 78)

- receipt.pdf (12 KB, Object 79)

# Analyze PDF for compression opportunities

$ ./pdf_parser large_document.pdf --analyze-streams

Content Stream Statistics:

Uncompressed: 15 streams (234 KB)

FlateDecode: 42 streams (1.2 MB → 340 KB, 72% compression)

LZW: 3 streams (45 KB → 38 KB, 16% compression)

Recommendation: Recompress uncompressed streams → save 180 KB

You’ll have built a Swiss Army knife for PDF analysis that you’ll use for years.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“What IS a PDF file, really? How does ‘frozen PostScript’ work without an interpreter?”

This is the key insight that separates developers who use PDFs from developers who understand them.

PDF isn’t just “a document format”—it’s a carefully designed data structure that solves a specific problem: How do you distribute PostScript documents without requiring an interpreter?

The answer: Separate structure from content.

PostScript (dynamic):

% This is EXECUTABLE CODE

/box {

/h exch def /w exch def

0 0 moveto w 0 lineto w h lineto 0 h lineto closepath

} def

100 50 box fill % Calls procedure - requires interpreter

PDF (static):

% This is FROZEN DATA

4 0 obj

<< /Length 44 >>

stream

0 0 m % moveto is now just 'm' - an operator, not a procedure call

100 0 l % All coordinates are pre-calculated

100 50 l % No variables, no loops, no procedure calls

0 50 l

h % closepath

f % fill

endstream

endobj

The profound difference:

| Aspect | PostScript | |

|---|---|---|

| Execution | Requires Turing-complete interpreter | Simple operator parsing |

| Page Access | Must execute from page 1 to get to page 100 | Jump directly to any page via xref table |

| File Size | Can be small (code generates content) | Larger (all content explicit) but compressed |

| Security | Dangerous (arbitrary code execution) | Safer (no loops/conditionals) |

| Reliability | Can hang, crash, or produce different output | Deterministic rendering |

By building this parser, you’ll internalize: PDF traded flexibility for reliability and random access.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Binary File Formats

- What does it mean that PDF is “partially binary, partially ASCII”?

- How do you parse a file format with mixed binary and text?

- What are “magic numbers” and why does PDF have

%PDF-at the start? - How do byte offsets work? Why does the xref table store them?

- Book Reference: “Practical Binary Analysis” by Dennis Andriesse — Ch. 2: “The ELF Format” (general principles)

- Object Graphs and References

- What is an “indirect object” in PDF? (vs. direct objects)

- How does PDF’s reference system work? (

10 0 Rmeans “reference to object 10, generation 0”) - Why use references instead of duplicating data?

- How do you resolve a reference? (Look up in xref table → jump to byte offset → parse object)

- Book Reference: “Developing with PDF” by Leonard Rosenthol — Ch. 1: “PDF Syntax”

- Cross-Reference (xref) Tables

- What problem does the xref table solve? (Random access to objects)

- Why store byte offsets instead of object IDs?

- What’s a “generation number”? (For incremental updates)

- How do you find the xref table? (Start from end of file, read

startxref) - Book Reference: “PDF Reference Manual 1.7” — Section 3.4.3: “Cross-Reference Table”

- Compression Algorithms

- What is Flate/Deflate compression? (zlib - same as gzip)

- How do you decompress a PDF stream? (Use zlib library)

- What’s the difference between stream compression and object compression?

- Why compress? (PDFs can be huge without it - images, fonts, repeated content)

- Book Reference: “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” by Bryant & O’Hallaron — Ch. 6.5: “Compression”

- PDF Dictionary Syntax

- How are PDF dictionaries structured? (

<< /Key1 Value1 /Key2 Value2 >>) - What’s the difference between a name (

/Type) and a string ((Hello))? - What are the basic PDF types? (boolean, integer, real, string, name, array, dictionary, stream, null)

- How do you parse nested dictionaries and arrays?

- Book Reference: “Developing with PDF” by Leonard Rosenthol — Ch. 1: “PDF Syntax”

- How are PDF dictionaries structured? (

- Content Stream Operators

- How are PDF operators similar to PostScript? (Almost identical!)

- What’s the difference between

moveto(PS) andm(PDF)? - How do you parse a content stream? (Tokenize → execute graphics state machine)

- Why are operators abbreviated? (

mnotmoveto,lnotlineto) - Book Reference: “PDF Reference Manual 1.7” — Appendix A: “Operator Summary”

- Page Tree Structure

- Why does PDF use a tree of pages instead of an array?

- What’s inherited in the page tree? (Resources, MediaBox, CropBox)

- How do you find page N? (Walk the tree, counting Kids)

- What’s the difference between

/Pagesand/Page? - Book Reference: “Developing with PDF” by Leonard Rosenthol — Ch. 3: “Page Geometry”

Self-assessment questions:

- Can you parse a binary file format in C? (fopen, fseek, fread)

- Do you understand pointers and dynamic memory? (Essential for object graph)

- Have you worked with compression libraries? (zlib or equivalent)

- Can you implement a hash table for object lookup?

If you answered “no” to any of these, stop and build those foundations first.

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- File Reading Strategy

- Will you load the entire PDF into memory? (Easy but memory-intensive)

- Or use file seeking to read objects on demand? (Complex but efficient)

- How do you handle large PDFs (100+ MB)?

- Should you memory-map the file? (mmap on Unix, MapViewOfFile on Windows)

- Object Storage

- How do you store parsed objects? (Hash table? Array indexed by object number?)

- Do you cache parsed objects or re-parse on each access?

- How do you handle circular references? (e.g., Page → Resources → Font → Page)

- What about linearized PDFs? (Optimized for web streaming)

- Parsing Architecture

- Will you parse the entire PDF upfront or lazily?

- How do you handle PDF versions? (1.3, 1.4, …, 2.0)

- What about malformed PDFs? (Many real-world PDFs violate the spec!)

- Should you support incremental updates? (PDF allows appending changes)

- Content Stream Processing

- How do you tokenize a content stream? (Similar to PostScript!)

- Will you execute operators or just extract them?

- How do you handle operator stacks? (Graphics state stack, text state, etc.)

- What about inline images? (Binary data within content streams)

- Rendering Backend

- Which library for rendering? (Cairo? Skia? Roll your own?)

- How do you handle fonts? (Embedded TrueType/Type1 vs. system fonts)

- What about images? (JPEG, JPEG2000, JBIG2, etc.)

- How do you handle transparency and blend modes?

- Decompression

- Which decompression filters to support? (Flate is most common)

- How do you detect filter type? (

/Filterkey in stream dictionary) - What about cascaded filters? (

[/ASCII85Decode /FlateDecode]) - How do you handle decompression errors gracefully?

- Validation and Error Handling

- What makes a PDF “valid”?

- How do you handle missing required keys?

- What about out-of-bounds object references?

- Should you try to repair broken PDFs?

Key insight to internalize: PDF parsing is two-phase: physical structure (xref, objects) → logical structure (document tree, content). Parse physical first.

Thinking Exercise

Manually Parse a Minimal PDF

Before writing code, do this exercise with a text editor and hex viewer:

Create the simplest valid PDF by hand:

%PDF-1.4

1 0 obj

<< /Type /Catalog /Pages 2 0 R >>

endobj

2 0 obj

<< /Type /Pages /Kids [3 0 R] /Count 1 >>

endobj

3 0 obj

<< /Type /Page /Parent 2 0 R /MediaBox [0 0 612 792]

/Contents 4 0 R >>

endobj

4 0 obj

<< /Length 44 >>

stream

BT

/F1 12 Tf

100 700 Td

(Hello!) Tj

ET

endstream

endobj

xref

0 5

0000000000 65535 f

0000000009 00000 n

0000000058 00000 n

0000000117 00000 n

0000000218 00000 n

trailer

<< /Size 5 /Root 1 0 R >>

startxref

315

%%EOF

Trace the parsing manually:

- Find xref table: Read from end, find

startxref 315, seek to byte 315 - Parse xref: Object 1 at byte 9, object 2 at byte 58, etc.

- Read trailer: Root is object 1

- Parse object 1 (Catalog): Seek to byte 9, read

<< /Type /Catalog /Pages 2 0 R >> - Follow reference

2 0 R: Look up object 2 in xref → byte 58 - Parse object 2 (Pages): Has one kid: object 3

- Parse object 3 (Page): Content is object 4

- Parse object 4 (Stream): Decompress and parse content

Questions while tracing:

- Why is object 0 marked as “free” (

f)? (Reserved for PDF internals) - What are the byte offsets for each object? (Calculate manually!)

- How do you know where the content stream ends? (

/Length 44means 44 bytes) - What do the operators in the stream mean?

BT= Begin Text/F1 12 Tf= Set font F1, 12pt100 700 Td= Move to (100, 700)(Hello!) Tj= Show text “Hello!”ET= End Text

Now add compression:

Replace object 4’s stream with a compressed version:

4 0 obj

<< /Length 32 /Filter /FlateDecode >>

stream

x\x9c\x0b\x1b\x50\xe0\xe2\xb3\xb4\x30\x54\x30\xe2\x08\x19\xc6\x05...

endstream

endobj

Trace the decompression:

- Read stream dictionary → see

/Filter /FlateDecode - Read 32 bytes of compressed data

- Pass to zlib’s

inflate()function - Get back the original text operators

The aha moment:

When you manually parse a PDF, you’ll realize: it’s just a binary database with a clever indexing scheme. The xref table is the index, objects are records, references are foreign keys.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

When you’ve completed this project, be ready to answer:

Conceptual Questions:

- “What is the fundamental difference between PDF and PostScript?”

- Answer: PS is Turing-complete executable code, PDF is static data structure. PS requires interpreter, PDF is parsed deterministically.

- “How does PDF achieve random page access?”

- Answer: Cross-reference table maps object IDs to byte offsets. Each page is an object. Jump directly to any page’s byte offset without parsing the whole file.

- “Why is PDF considered safer than PostScript for email attachments?”

- Answer: PDF has no loops, conditionals, or arbitrary code execution. PS can run infinite loops or malicious code.

- “Explain PDF’s object reference system”

- Answer: Indirect objects have IDs (

10 0 obj). References (10 0 R) point to them. Xref table resolves references to byte offsets.

- Answer: Indirect objects have IDs (

- “What problem do content streams solve?”

- Answer: Separate page structure (objects) from page content (drawing operators). Allows compression and logical organization.

Technical Questions:

- “How do you find the xref table in a PDF?”

```

- Seek to end of file

- Read backwards to find “startxref”

- Read the byte offset after it

- Seek to that offset → xref table ```

- “What are the steps to render a PDF page?”

```

- Find Catalog → Pages tree → specific Page object

- Get page’s /Contents reference

- Dereference to get content stream object

- Decompress stream if /Filter present

- Parse operators and update graphics state

- Render based on final state ```

- “How would you implement PDF object dereferencing?”

Object* dereference(PDF* pdf, Reference ref) { XRefEntry* entry = &pdf->xref[ref.obj_num]; fseek(pdf->file, entry->byte_offset, SEEK_SET); return parse_object(pdf->file); } - “What’s the difference between

/Type /Pagesand/Type /Page?”- Answer:

/Pagesis an internal node in the page tree (has/Kidsarray)./Pageis a leaf node (the actual page with/Contents).

- Answer:

- “How do you decompress a Flate-encoded stream?”

#include <zlib.h> unsigned char* decompress_flate(unsigned char* compressed, size_t comp_len, size_t* out_len) { z_stream stream = {0}; inflateInit(&stream); // ... allocate output buffer, call inflate(), cleanup return decompressed; }

Design Questions:

- “How would you handle a PDF with thousands of pages efficiently?”

- Answer: Lazy loading - parse page tree structure, but only load page content on demand. Don’t load all pages into memory.

- “What’s your strategy for malformed PDFs?”

- Answer: Parse leniently (accept common violations), but log warnings. Attempt repair (e.g., rebuild xref from scan). Fail gracefully on corruption.

- “How would you optimize for streaming/progressive loading?”

- Answer: Support linearized PDFs (hint table at front). Parse critical objects first. Stream decompression.

Comparison Questions:

- “Compare PDF object graphs to ELF section tables”

- Answer: Both use indirection (offsets/references), both have header→index→data structure, both support linking (ELF relocations = PDF references)

- “How is PDF compression different from compressing the whole file (gzip)?”

- Answer: PDF compresses individual streams, not file structure. Allows random access without decompressing everything. More complex but more flexible.

Prepare to draw:

- PDF file structure (header, body, xref, trailer)

- Object reference graph

- Page tree hierarchy

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with structure dumping, not rendering

Don’t try to render immediately. First, just print the file structure:

// Phase 1: Just find and parse xref table

int main() {

FILE* f = fopen("test.pdf", "rb");

// Seek to end, find "startxref"

fseek(f, -50, SEEK_END);

char buf[50];

fread(buf, 1, 50, f);

// Parse backwards for "startxref"

// Jump to xref location

// Parse xref table

// Print object offsets

}

Test: ./pdf_parser simple.pdf prints xref table correctly

Hint 2: Implement object dereferencing

typedef struct {

int obj_num;

int gen_num;

long byte_offset;

bool in_use;

} XRefEntry;

typedef struct {

FILE* file;

XRefEntry* xref;

int xref_size;

} PDF;

Object* get_object(PDF* pdf, int obj_num) {

if (obj_num >= pdf->xref_size) return NULL;

XRefEntry* entry = &pdf->xref[obj_num];

if (!entry->in_use) return NULL;

fseek(pdf->file, entry->byte_offset, SEEK_SET);

return parse_object(pdf->file);

}

Hint 3: Parse dictionaries recursively

Dictionary* parse_dictionary(FILE* f) {

expect_token(f, "<<");

Dictionary* dict = dict_new();

while (true) {

Token tok = next_token(f);

if (tok.type == TOKEN_DICT_END) break; // ">>"

if (tok.type != TOKEN_NAME) error("Expected name");

char* key = tok.value; // e.g., "/Type"

Object* value = parse_value(f); // Recursive!

dict_insert(dict, key, value);

}

return dict;

}

Hint 4: Handle streams separately

Object* parse_object(FILE* f) {

Dictionary* dict = parse_dictionary(f);

// Check if this is a stream

Token tok = peek_token(f);

if (strcmp(tok.value, "stream") == 0) {

consume_token(f);

int length = dict_get_int(dict, "/Length");

unsigned char* data = malloc(length);

fread(data, 1, length, f);

expect_token(f, "endstream");

return stream_object_new(dict, data, length);

}

return dict_object_new(dict);

}

Hint 5: Use zlib for decompression

#include <zlib.h>

unsigned char* decompress_stream(Stream* stream) {

Object* filter = dict_get(stream->dict, "/Filter");

if (!filter || strcmp(filter->value, "/FlateDecode") != 0) {

return stream->data; // Not compressed

}

// Decompress with zlib

int length = dict_get_int(stream->dict, "/Length");

unsigned char* decompressed = malloc(length * 4); // Estimate

z_stream z = {0};

z.next_in = stream->data;

z.avail_in = stream->raw_length;

z.next_out = decompressed;

z.avail_out = length * 4;

inflateInit(&z);

inflate(&z, Z_FINISH);

inflateEnd(&z);

return decompressed;

}

Hint 6: Parse content stream operators

void parse_content_stream(unsigned char* data, int length) {

Tokenizer* tok = tokenizer_new(data, length);

while (!tokenizer_done(tok)) {

Token t = next_token(tok);

if (t.type == TOKEN_OPERATOR) {

if (strcmp(t.value, "m") == 0) { // moveto

double y = pop_number(stack);

double x = pop_number(stack);

graphics_state_moveto(gstate, x, y);

}

else if (strcmp(t.value, "l") == 0) { // lineto

double y = pop_number(stack);

double x = pop_number(stack);

graphics_state_lineto(gstate, x, y);

}

// ... more operators

}

else if (t.type == TOKEN_NUMBER) {

push_number(stack, t.number_value);

}

}

}

Hint 7: Test with hand-crafted PDFs

Create minimal test PDFs to verify each feature:

# Minimal PDF (no compression)

cat > test_simple.pdf << 'EOF'

%PDF-1.4

1 0 obj

<< /Type /Catalog /Pages 2 0 R >>

endobj

2 0 obj

<< /Type /Pages /Kids [3 0 R] /Count 1 >>

endobj

3 0 obj

<< /Type /Page /Parent 2 0 R /MediaBox [0 0 612 792] /Contents 4 0 R >>

endobj

4 0 obj

<< /Length 15 >>

stream

100 100 m 200 200 l S

endstream

endobj

xref

0 5

0000000000 65535 f

0000000009 00000 n

0000000058 00000 n

0000000117 00000 n

0000000231 00000 n

trailer

<< /Size 5 /Root 1 0 R >>

startxref

310

%%EOF

EOF

./pdf_parser test_simple.pdf --dump-operators

Hint 8: Use existing tools to verify your parsing

# Compare your output with pdfinfo

pdfinfo test.pdf

# Extract content streams with pdftk

pdftk test.pdf output uncompressed.pdf uncompress

# Now you can read content streams as plain text!

# Analyze structure with qpdf

qpdf --qdf test.pdf - | less

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| PDF file structure | “Developing with PDF” by Leonard Rosenthol | Ch. 1: “PDF Syntax”, Ch. 2: “Document Structure” |