Deconstructing uv’s Performance Secrets - Real World Projects

Goal: Deeply understand the engineering behind

uv’s speed—moving beyond “it’s written in Rust.” You will explore the PubGrub algorithm, content-addressable storage, HTTP/2 multiplexing, and filesystem-level copy-on-write (reflink) mechanisms. By the end, you will be able to build high-performance systems tools that handle massive dependency graphs and I/O-bound tasks with ease.

Why uv Performance Matters

For years, Python developers have grappled with slow package installations and complex dependency management. pip, while foundational, often struggles with large dependency trees, leading to lengthy installation times and cryptic error messages. This inefficiency impacts developer productivity, CI/CD pipelines, and the overall development experience.

uv changed the landscape by proving that developer tools can be as optimized as database kernels. It boasts 10-100x faster package operations compared to pip, transforming the Python development workflow.

Understanding uv’s architecture unlocks:

- Systems Thinking: Learning how to bypass high-level abstractions for direct OS control.

- Algorithmic Mastery: Understanding SAT solvers and conflict resolution (PubGrub).

- Rust Proficiency: Seeing why memory safety without a GC is critical for CLI startup times and memory efficiency.

- Filesystem Mastery: Using Reflinks and Hardlinks to avoid data duplication.

Core Concept Analysis

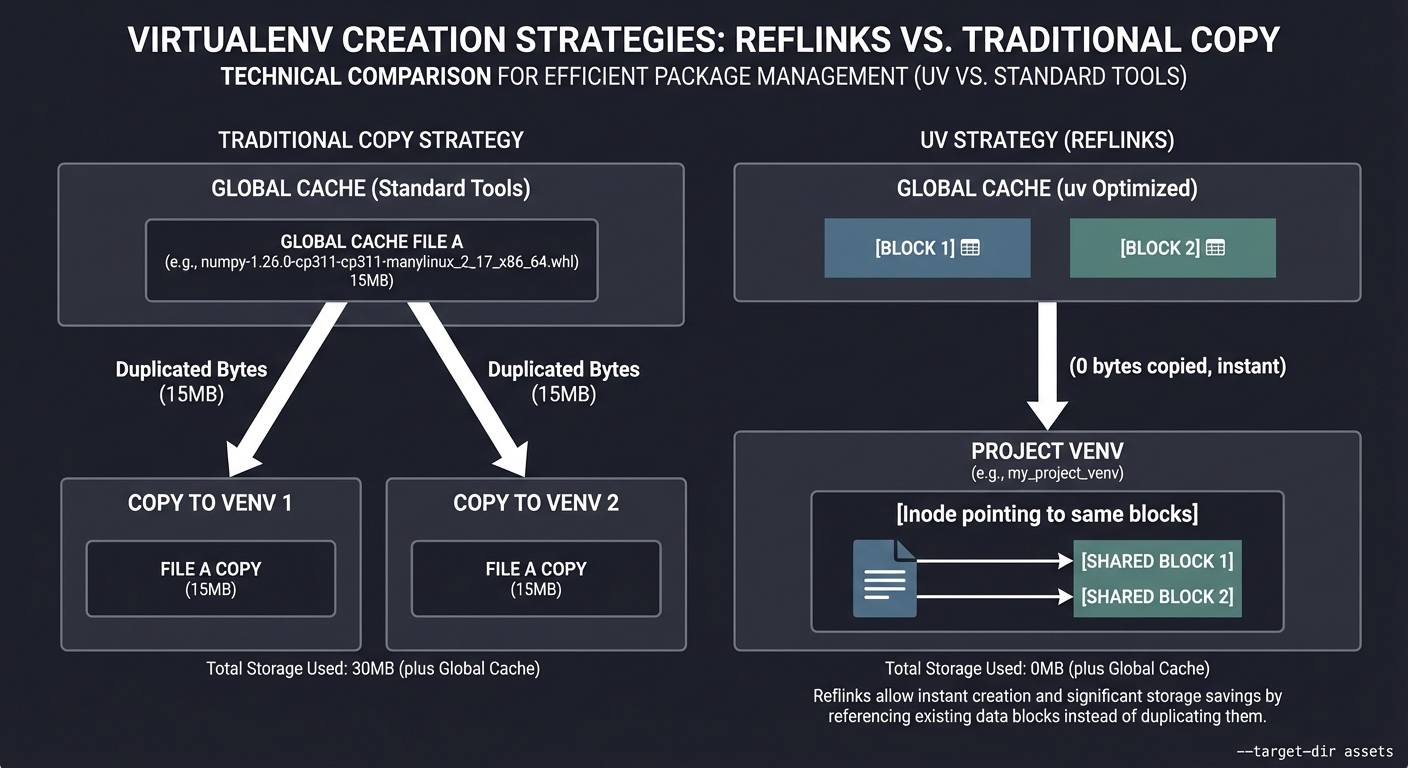

1. The Virtualenv Creation Bottleneck: Reflinks & Hardlinks

In traditional tools, creating a venv involves copying thousands of small files. uv avoids this using Reflinks (Copy-on-Write) or Hardlinks.

Traditional Copy (Slow + Space):

[Global Cache File A] ──► [Copy to Venv 1]

──► [Copy to Venv 2] (Duplicated Bytes)

uv Strategy (Instant + Shared Space):

┌──────────────────┐ ┌──────────────────┐

│ Global Cache │ │ Project Venv │

│ [Block 1][Block 2]────┐ │ [Inode pointing │

└──────────────────┘ │ │ to same blocks] │

│ └──────────────────┘

└────► (0 bytes copied, instant)

Key insight: On supported filesystems (APFS on macOS, XFS/Btrfs on Linux), a reflink points multiple files to the same physical blocks on disk without increasing disk usage until one of the files is modified.

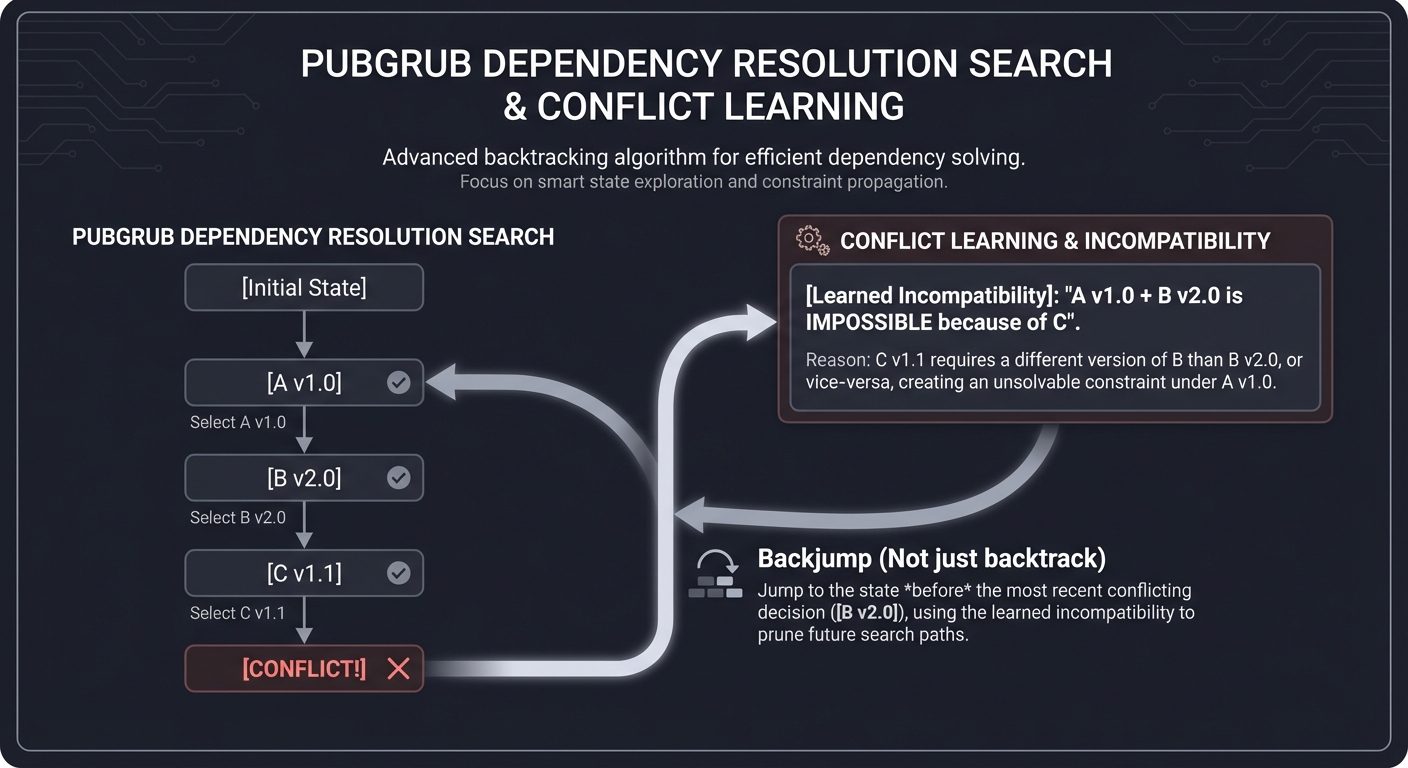

2. The Resolution Brain: PubGrub & CDNL

uv utilizes the PubGrub algorithm for dependency resolution. It’s inspired by Conflict-Driven Nogood Learning (CDNL), a technique from SAT solvers.

Resolution Search Tree:

[A v1.0] ──► [B v2.0] ──► [C v1.1] ──► CONFLICT!

│

┌─────────────────────────────────────┘

▼

[Learned Incompatibility]: "A v1.0 + B v2.0 is IMPOSSIBLE because of C"

│

└─► Backjump (Not just backtrack) to a state before B v2.0 was picked.

PubGrub avoids millions of useless checks by “learning” from every failure, making it significantly faster and more efficient than pip’s backtracking resolver.

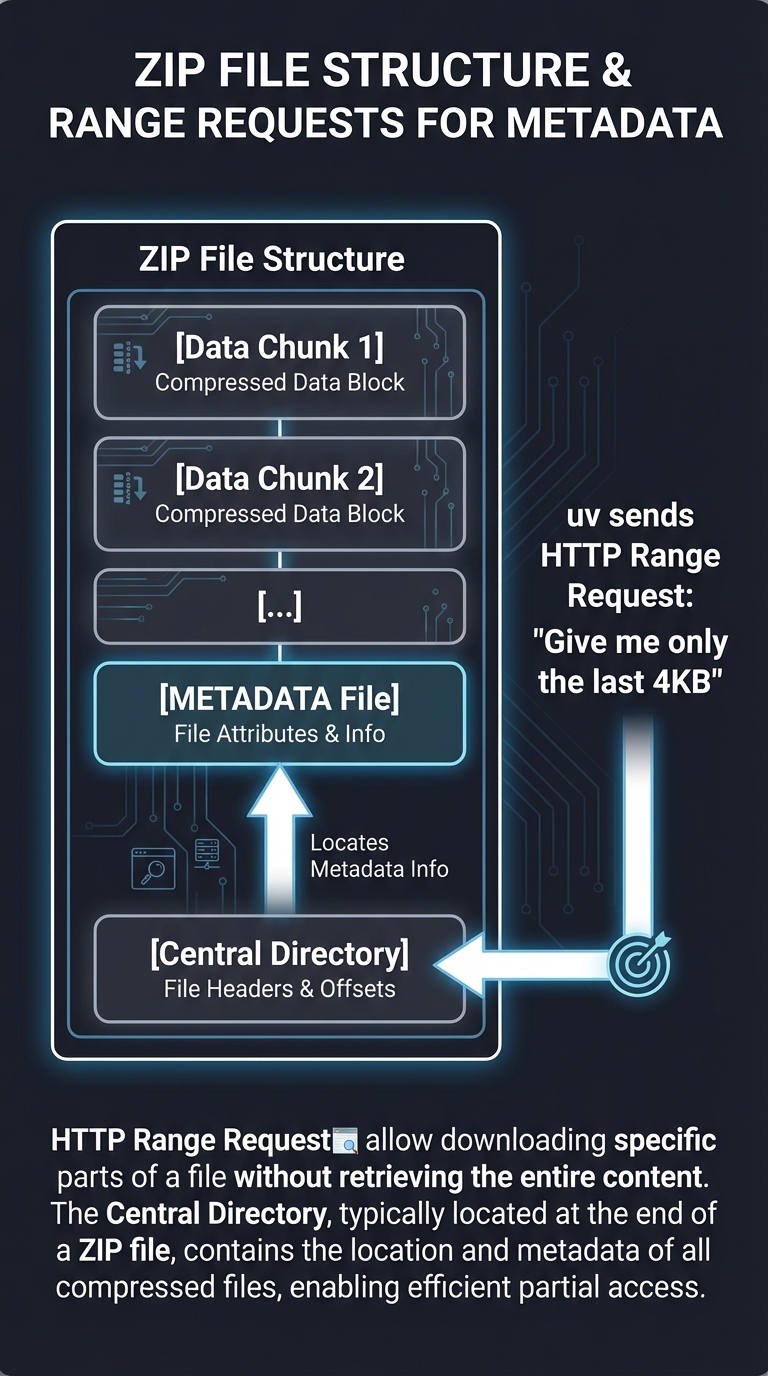

3. Metadata Pipelining & Range Requests

uv doesn’t wait for a wheel to download to see its dependencies. It fetches just the metadata (PEP 658) via JSON APIs or dedicated Range Requests.

ZIP File (Wheel) Structure:

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ [Data Chunk 1] │

│ [Data Chunk 2] │

│ [METADATA File] <───┐ │

│ ... │ │

│ [Central Directory] ─┴────┤

└───────────────────────────┘

▲

└─ uv sends HTTP Range Request: "Give me only the last 4KB"

By reading the Central Directory at the end of the ZIP file first, uv knows exactly where the METADATA file is located and can fetch only those specific bytes.

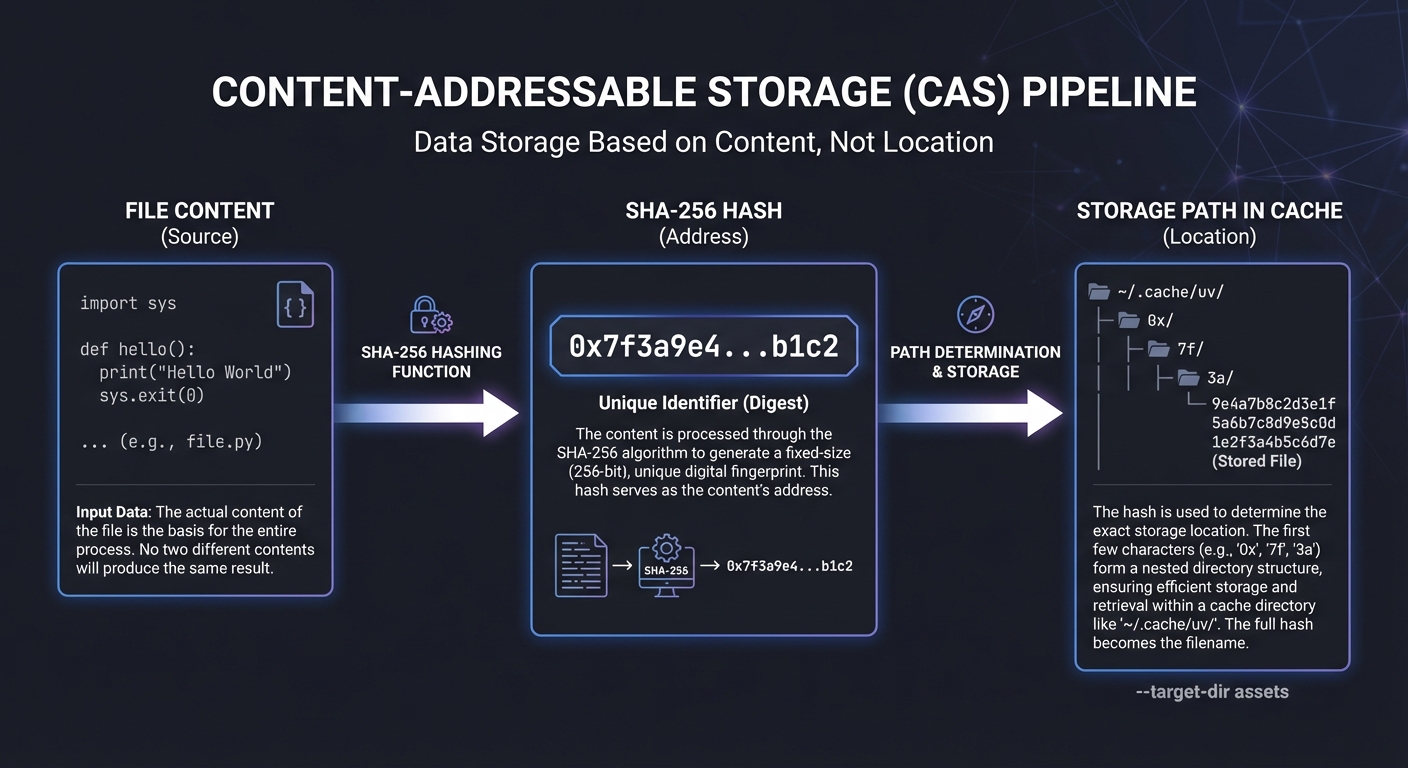

4. Content-Addressable Storage (CAS)

uv stores files in a global cache indexed by their content hashes (e.g., SHA-256).

File Content ──► [SHA-256 Hash] ──► Path in Cache

"import sys..." ──► 0x7f3a... ──► ~/.cache/uv/0x/7f/3a...

This ensures that if two different packages contain the exact same file content (e.g., a README or a common license), it is only stored once on disk.

5. Why C/Rust vs Python for CLI Tools

| Feature | Python (pip) | Rust (uv) |

|---|---|---|

| Startup | ~100-300ms (Interpreter load) | <5ms (Static binary) |

| GIL | Yes (Sequential I/O) | No (Parallel threads) |

| Deserialization | json.load (Copying) |

rkyv (Zero-copy) |

| Memory | GC overhead | Manual/RAII control |

Concept Summary Table

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize |

|---|---|

| Performance Drivers | Rust, parallel operations, optimized algorithms (PubGrub), and efficient caching. |

| PubGrub | How logic solvers find valid states in NP-hard graphs using conflict learning. |

| I/O Efficiency | The difference between cp, ln, and reflink. Filesystem inodes. |

| Networking | HTTP/2 multiplexing and Range requests for partial ZIP parsing. |

| Metadata | Native parsing of pyproject.toml and wheel metadata without Python subprocesses. |

| CAS Storage | Content-addressable storage and deduplication via hashing. |

Deep Dive Reading by Concept

Essential Resources

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Systems & Perf | Programming Rust, 3rd Edition (Blandy) — Ch. 1: “Why Rust?” & Ch. 16: “Concurrency” |

| Filesystems | Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces (Arpaci-Dusseau) — Ch. 39: “Files and Directories” |

| SAT Solvers | The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 4, Fascicle 6 (Knuth) — Satisfiability |

| ZIP/Formats | Write Great Code, Volume 1 (Hyde) — Ch. 3: “Data Representation” |

| Network (HTTP) | TCP/IP Illustrated, Volume 1 (Fall/Stevens) — Ch. 20: “HTTP” |

| System Programming | The Linux Programming Interface (Kerrisk) — Ch. 14: “File I/O” |

Project 1: Fast Metadata Parser (The “Static” Speed)

- Main Programming Language: Rust

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Difficulty: Level 1: Beginner

- Knowledge Area: ZIP Internals, String Parsing

- Software or Tool:

zipcrate

What you’ll build: A CLI tool that opens a Python Wheel (.whl) and extracts the METADATA file without scanning the entire archive.

Real World Outcome

You will create a CLI tool called wheel-meta that can instantly extract dependency information from any Python wheel file. You’ll see how uv avoids downloading whole files by jumping straight to the “index” of the ZIP.

$ ./wheel-meta requests-2.31.0-py3-none-any.whl

[File Info]

Name: requests-2.31.0-py3-none-any.whl

Size: 62.4 KB

[Parsed METADATA]

Name: requests

Version: 2.31.0

Requires-Dist: charset-normalizer (<4,>=2)

Requires-Dist: idna (<4,>=2.5)

Requires-Dist: urllib3 (<3,>=1.21.1)

Requires-Dist: certifi (>=2017.4.17)

# Execution Time: 0.002s (vs pip's ~0.2s)

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How can I read specific data from a 100MB file in constant time without reading the whole 100MB?”

Most developers treat files as streams (start to finish). uv treats files as random-access databases. This project proves that understanding file formats (like ZIP) allows you to bypass 99% of I/O.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- The ZIP Format Anatomy

- What is the Central Directory?

- Why is the Central Directory at the end of the file?

- What is an End of Central Directory Record (EOCD)?

- File Seeking

- What does

fseek()(orSeektrait in Rust) do at the OS level? - Why is seeking “free” while reading is “expensive”?

- What does

- Rust’s

SeekandReadTraits- How does the

zipcrate use a seeker to find files? - Difference between

BufReaderand rawFile.

- How does the

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Locating the Index

- If a ZIP file is a collection of files, where is the list of those files stored?

- How do you find that list if you don’t know the file size beforehand?

- Parsing the Wheel

- Python Wheels are just ZIPs. Where is the

METADATAfile stored inside them? (Hint:*.dist-info/METADATA). - How do you filter for just this specific file?

- Python Wheels are just ZIPs. Where is the

- Performance Measurement

- How can you measure exactly how many bytes your program read from the disk?

- How many bytes are in the

METADATAfile vs the whole wheel?

Thinking Exercise

Trace the ZIP Jump

Imagine a 1GB ZIP file.

- Your code opens the file.

- It “jumps” to the last 22 bytes to find the EOCD.

- The EOCD tells it the Central Directory is at offset 950MB.

- Your code “jumps” to 950MB and reads the directory.

- It finds

METADATAis at offset 10MB and is 2KB long. - It “jumps” to 10MB and reads 2KB.

Question: How many total bytes were actually read from the disk? (Answer: ~22 bytes + directory size + 2KB. NOT 1GB).

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “Why is the ZIP Central Directory at the end of the file instead of the beginning?”

- “What is the complexity (O) of finding a file in a ZIP if you have the Central Directory?”

- “How does

uvuse this property to optimize network downloads?” (Hint: Range requests). - “What happens if a ZIP file is truncated? Can you still recover any data?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Use the zip crate

Don’t write a ZIP parser from scratch. Use zip::ZipArchive. It requires a type that implements Read + Seek.

Hint 2: Find the METADATA path

Iterate through archive.file_names(). Look for a name that ends in .dist-info/METADATA.

Hint 3: Stream the content

Once you have the ZipFile handle, you can read it directly into a String.

Hint 4: Benchmarking

Use std::time::Instant to wrap your main logic. Try running it on a very large wheel (like torch) and notice it’s just as fast as a small one.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Data Representation | Write Great Code, Volume 1 | Ch. 3 |

| Rust File I/O | Programming Rust | Ch. 15: “Input and Output” |

| Filesystem Internals | Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces | Ch. 39 |

| Python Packaging Specs | Python Packaging User Guide | “The Wheel Binary Package Format” |

Project 2: The “Reflink” Explorer (Zero-Copy I/O)

- Main Programming Language: Rust

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Filesystems, System Calls

- Software or Tool:

libc,nixcrate

What you’ll build: A tool that clones files using FICLONE (Linux) or clonefile (macOS).

Real World Outcome

You will build a tool called fast-cp. Unlike regular cp, which copies every byte, fast-cp will create a “clone” of a file that takes up zero extra space until it is changed. This is exactly how uv makes virtualenvs “free.”

# Create a 1GB dummy file

$ dd if=/dev/zero of=bigfile bs=1M count=1000

# Regular copy (Slow)

$ time cp bigfile copy1

real 0m1.2s

# Your fast-cp (Instant)

$ time ./fast-cp bigfile copy2

real 0m0.001s

# Check disk usage (Both exist, but only 1GB is used on disk)

$ du -sh .

1.0G .

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How can I have two files on disk with the same content but only store the bytes once, without using symlinks?”

Symlinks break if the source is deleted. Hardlinks break if you edit one file (both change). Reflinks are the “holy grail”: they share blocks until you write to one, then the OS automatically splits them (Copy-on-Write).

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Inodes vs Blocks

- An Inode is the metadata (name, size).

- Blocks are the physical data on the disk platter/SSD.

- Usually, 1 Inode = 1 set of Blocks. Reflinks allow N Inodes to point to the same set of Blocks.

- Copy-on-Write (CoW)

- What happens when you write to a shared block?

- How does the OS handle the split?

- System Calls (ioctl)

- On Linux, reflinking is done via

ioctlwithFICLONE. - On macOS, it’s

clonefile().

- On Linux, reflinking is done via

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Detecting Support

- How do you check if a filesystem (EXT4, Btrfs, APFS) actually supports reflinks?

- What happens if it doesn’t? (Fallback to

std::fs::copy).

- The

libcBridge- How do you call a C function like

ioctlorclonefilefrom Rust? - How do you handle file descriptors safely?

- How do you call a C function like

- Verifying the Magic

- How can you programmatically verify that a copy is a reflink and not a full copy? (Hint: compare

blocksinstatvs file size).

- How can you programmatically verify that a copy is a reflink and not a full copy? (Hint: compare

Thinking Exercise

The Virtualenv Space Trap

You have 10 Python projects. Each uses pandas (30MB).

- With pip: 10 projects * 30MB = 300MB used.

- With uv (Reflinks): 10 projects * 0MB (cloned from cache) + 1 cache * 30MB = 30MB used.

Question: If you edit a file inside one virtualenv’s pandas folder, do the other 9 projects see the change? (Answer: No, the OS copies that specific block just for that file).

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is the difference between a Hardlink and a Reflink?”

- “Why does

uvprefer reflinks over symlinks for packages?” (Hint: Symlinks break portable environments). - “What happens to a reflinked file if the original source is deleted from the cache?”

- “Which filesystems support

FICLONE?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Use the nix crate

The nix crate provides safer wrappers for ioctl and system calls. For macOS, you might need to use std::os::unix::fs::ext or direct libc bindings.

Hint 2: Linux FICLONE

// Simplified Linux Logic

let src = File::open("src")?;

let dst = File::create("dst")?;

unsafe {

libc::ioctl(dst.as_raw_fd(), libc::FICLONE, src.as_raw_fd());

}

Hint 3: macOS clonefile

On macOS, look for copyfile with the COPYFILE_CLONE flag.

Hint 4: Fallback Strategy

Always implement a fallback. If the reflink fails (e.g., source and dest are on different partitions), perform a standard std::fs::copy.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Filesystem Implementation | Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces | Ch. 40 |

| Linux I/O and ioctl | The Linux Programming Interface | Ch. 4 & 5 |

| APFS Internals | macOS Internals (Levin) | File Systems |

| Rust FFI | The Rust Programming Language | Ch. 19: “Advanced Features” |

Project 3: Async Parallel Resolver (Networking)

- Main Programming Language: Rust

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Networking, Async/Await, HTTP/2

- Software or Tool:

tokio,reqwest

What you’ll build: A tool that fetches package metadata from the PyPI JSON API for 50 packages simultaneously using a single TCP connection (Multiplexing).

Real World Outcome

You’ll create a tool pypi-peek that can resolve a list of 100 packages in the time it takes to resolve one. You’ll see the power of tokio’s concurrent execution.

$ ./pypi-peek requirements.txt

[Parallel Fetch]

Fetching: requests... OK

Fetching: flask... OK

Fetching: numpy... OK

...

Fetched 100 metadata files in 0.45s!

# (pip would take ~5-10s for this)

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do I maximize network throughput without being blocked by ‘Wait’ times?”

Networking is mostly waiting. Waiting for the server, waiting for the packet. uv fills these “wait gaps” by starting other requests.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Async/Await & Futures

- Why do we need an “Executor” (Tokio)?

- What is a “Zero-cost Future”?

- HTTP/2 Multiplexing

- Difference between opening 50 TCP connections (slow) and 1 connection with 50 streams (fast).

- Concurrency vs Parallelism

- How does Rust handle thousands of “tasks” on just 8 CPU cores?

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Throttling

- If you send 1000 requests at once, will PyPI ban you?

- How do you use a

Semaphoreto limit concurrency to 50 at a time?

- Error Handling

- If 1 out of 50 requests fails, should the whole program stop?

- How do you use

join_allvsFuturesUnordered?

Thinking Exercise

The Wait-Time Math

- Request 1: 100ms wait.

- Request 2: 100ms wait.

- Sequential: 1 + 2 = 200ms.

- Concurrent: Max(1, 2) = 100ms.

Question: If you have 10,000 requests, what happens to your RAM if you start them all at once? (Answer: Each task has an overhead; you need a way to queue them).

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is the difference between

tokio::spawnandfutures::join_all?” - “How does HTTP/2 help with the ‘Head-of-Line Blocking’ problem?”

- “How would you implement a retry logic with exponential backoff in an async context?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with reqwest

Use reqwest::Client. It is designed to be shared across many tasks.

Hint 2: Use tokio::spawn

Loop through your packages and tokio::spawn a fetch task for each. Collect the JoinHandles.

Hint 3: Use a Semaphore

let permit = semaphore.acquire_owned().await.unwrap();

// Do work

drop(permit);

Hint 4: Metadata API

Use the PyPI JSON API: https://pypi.org/pypi/<package>/json.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Async Rust | Programming Rust | Ch. 20: “Asynchronous Programming” |

| HTTP Internals | TCP/IP Illustrated | Ch. 20 |

| Distributed Systems | Designing Data-Intensive Applications | Ch. 1: “Reliable, Scalable Systems” |

Project 4: The PubGrub Logic Solver (The Brain)

- Main Programming Language: Rust

- Difficulty: Level 5: Master

- Knowledge Area: Algorithms, Logic, SAT Solvers

What you’ll build: A simplified PubGrub solver that finds a valid solution for a dependency graph using “Conflict Learning.”

Real World Outcome

You’ll build a solver that can find a version path for a set of constraints that would make a human’s head spin.

$ ./my-resolver "A requires B>=2.0, B 2.0 requires C<1.0, C 1.0 is incompatible with A"

[Searching...]

Trying A v1.0...

Trying B v2.0...

Conflict detected at C!

Learning: A v1.0 is incompatible with B v2.0.

Backjumping...

Trying A v0.9...

Success! Solution: A 0.9, B 2.1, C 0.5

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do I solve a puzzle with millions of combinations without checking every single one?”

Dependency resolution is “NP-Hard.” It’s essentially a Sudoku puzzle where every package you pick constraints the others.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Version Ranges (SemVer)

- How to check if

1.2.3satisfies^1.0.0.

- How to check if

- Conflict-Driven Nogood Learning (CDNL)

- The idea of “Learning from failure.” If A and B don’t work together, never try A and B together again in any other branch.

- Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAG)

- How to represent dependencies as a graph.

Questions to Guide Your Design

- The Search Loop

- How do you pick the “next” package to resolve? (Heuristics).

- Should you pick the one with the most constraints first?

- The Incompatibility List

- How do you store “Nogoods” (invalid combinations) so they can be checked quickly?

- Backjumping

- If a conflict happens at level 10, but the cause was a choice at level 2, how do you jump straight back to level 2?

Thinking Exercise

The Puzzle Solver

You have:

AppneedsLib v1.Lib v1needsHelper v2.Appalso needsHelper v1. Conflict!

Question: Instead of just saying “Error”, how can the program explain why it failed? (Answer: By tracing the path of constraints back to the root).

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What makes dependency resolution an NP-Hard problem?”

- “What is ‘Diamond Dependency’ and how do resolvers handle it?”

- “How does PubGrub differ from a simple recursive backtracking resolver?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Study the spec Read the PubGrub guide. It is the clearest explanation of the algorithm.

Hint 2: Small Steps Start with a graph that has no conflicts. Implement simple breadth-first search.

Hint 3: The “Incompatibility” Struct

Define a struct that represents (Package A, Version Range) + (Package B, Version Range) = IMPOSSIBLE.

Hint 4: Use a Crate for SemVer

Don’t write your own version parser. Use the semver crate.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Graphs & Search | Algorithms, 4th Edition | Ch. 4: “Graphs” |

| SAT Solving | The Art of Computer Programming, Vol 4 | Fascicle 6 |

| Logic & Type Systems | Types and Programming Languages | Ch. 1: “Introduction” |

Project 5: Content-Addressable Cache (Storage)

- Main Programming Language: Rust

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Hashing, Storage, Deduplication

- Software or Tool:

sha2crate

What you’ll build: A storage system where files are indexed by their SHA-256 hash rather than their original filename.

Real World Outcome

You’ll build a tool cas-store. When you “store” a file, it returns a hash. If you store the same file 100 times, it only takes up space once.

$ ./cas-store save package_v1.tar.gz

Stored as: a1b2c3d4...

$ ./cas-store save same_file_different_name.tar.gz

Already exists: a1b2c3d4... (No data written)

$ ./cas-store get a1b2c3d4... > restored.file

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How can I store millions of files and ensure I never download or store the same content twice?”

Filenames are unreliable. uv uses Content-Addressable Storage (CAS) to create a “Single Source of Truth” for every package version.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Cryptographic Hashing (SHA-256)

- What is a “Collision”?

- Why is the hash of a file always the same regardless of its name?

- Directory Sharding

- Why is it bad to have 100,000 files in one folder?

- How does

uvuse the first few characters of a hash (e.g.,ab/c1/...) to create subdirectories?

- Atomic Writes

- How do you ensure a file isn’t corrupted if the computer crashes while writing to the cache? (Hint: Write to a temp file, then rename).

Questions to Guide Your Design

- The Hash Pipeline

- Should you read the whole file into memory to hash it? (Hint: Use

sha2’s streaming interface).

- Should you read the whole file into memory to hash it? (Hint: Use

- Cleanup/GC

- How do you know when it’s safe to delete a file from the cache? (Reference counting).

- Concurrency

- What happens if two threads try to write the same hash at the exact same time?

Thinking Exercise

The Git Comparison

Git is a CAS. Every “commit” and “blob” (file) is stored by its hash.

Question: If you rename index.js to app.js but don’t change the code, does Git’s database grow in size? (Answer: No, the hash of the content remains identical).

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “Why use SHA-256 instead of MD5 for a cache?”

- “What is directory sharding and why is it important for high-performance filesystems?”

- “Explain how you would handle partial writes in a content-addressable system.”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Use sha2 crate

let mut hasher = Sha256::new();

hasher.update(data);

let result = hasher.finalize();

Hint 2: Streaming Hash

Read files in 8KB chunks and update the hasher to avoid high memory usage.

Hint 3: Atomic Rename

Always write your file to ~/.cache/tmp/<uuid> first, then move it to ~/.cache/<hash_prefix>/<hash>. Moving a file on the same partition is an atomic operation in Linux/macOS.

Hint 4: Sharding

If the hash is a1b2c3d4, save it at cache_root/a1/b2/c3d4. This prevents folder-read performance degradation.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Hashing | Serious Cryptography | Ch. 6: “Hash Functions” |

| Filesystems | Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces | Ch. 40 |

| Data Structures | The Joys of Hashing | Ch. 1 |

Project 6: Virtualenv “Factory” (Layout)

- Main Programming Language: Rust

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: OS Internals, Python Environment Specs

What you’ll build: A tool that manually constructs a Python virtual environment layout from scratch, including the pyvenv.cfg and the correct folder hierarchy.

Real World Outcome

You’ll build my-venv-create. It will create a folder that Python recognizes as a valid environment, allowing you to source .venv/bin/activate.

$ ./my-venv-create my-env --python /usr/bin/python3

Created venv at ./my-env

$ source my-env/bin/activate

(my-env) $ which python

/your/path/my-env/bin/python

The Core Question You’re Answering

“What is a ‘Virtual Environment’ really? Is it a container? Is it a VM?”

No. It’s just a folder with a specific structure and a configuration file that tells the Python interpreter where to look for libraries.

Concepts You Must Understand First

pyvenv.cfg- What are the required keys? (

home,include-system-site-packages,version).

- What are the required keys? (

- The

bin/Scriptsfolder- On Unix, why does the

pythonexecutable in a venv often just symlink back to the system python?

- On Unix, why does the

- Site-Packages

- How does Python know to look in the venv’s

lib/pythonX.Y/site-packages?

- How does Python know to look in the venv’s

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Cross-Platform Pathing

- In Windows, it’s

Scripts/python.exe. In Linux, it’sbin/python. How does your Rust code handle this?

- In Windows, it’s

- Python Version Detection

- How do you extract the version string from the system Python to put into the

pyvenv.cfg?

- How do you extract the version string from the system Python to put into the

- Symlinking vs Copying

- Should you symlink the interpreter or copy it? What does

uvdo? (Usually symlinks or uses a shim).

- Should you symlink the interpreter or copy it? What does

Thinking Exercise

Trace the Python Search Path

When you run import requests, Python looks in sys.path.

Question: How does creating a pyvenv.cfg file in a directory change sys.path? (Answer: The interpreter checks the folder it lives in for this config file; if found, it resets the prefix).

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What happens when you ‘activate’ a virtual environment?” (Hint: It just changes the

PATHenv variable). - “What is the purpose of the

homekey inpyvenv.cfg?” - “Can a virtual environment work without the

bin/activatescript?” (Answer: Yes, by calling the binary directly).

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: The Structure On Linux:

bin/lib/pythonX.Y/site-packages/include/pyvenv.cfg

Hint 2: The Config

home = /usr/bin

include-system-site-packages = false

version = 3.10.12

executable = /usr/bin/python3

command = /path/to/your/tool my-env

Hint 3: Use std::fs::create_dir_all

Build the nested lib/pythonX.Y/site-packages path in one go.

Hint 4: Version Discovery

Run python --version as a subprocess and parse the output to get the version string.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Python Internals | Expert Python Programming | Ch. 2: “Modern Python Development” |

| OS Processes | How Linux Works | Ch. 3: “Devices and Filesystems” |

| Rust Shell commands | Programming Rust | Ch. 18: “Foreign Functions” (for subprocesses) |

Project 7: Lockfile Generator (Serialization)

- Main Programming Language: Rust

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Serialization, TOML, Deterministic Outputs

- Software or Tool:

serde,tomlcrates

What you’ll build: A tool that takes a resolved dependency graph and saves it as a deterministic uv.lock file.

Real World Outcome

You’ll create lock-gen. It takes a list of packages and versions and produces a TOML file that is guaranteed to be identical every time it’s generated for the same input.

$ ./lock-gen --add requests:2.31.0 --add urllib3:2.0.7

# Output (uv.lock format):

[[package]]

name = "requests"

version = "2.31.0"

dependencies = ["urllib3"]

[[package]]

name = "urllib3"

version = "2.0.7"

[metadata]

hash = "sha256:e3b0c442..."

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do I ensure that a project installed today will be exactly the same when installed 5 years from now?”

A lockfile is a “snapshot” of a resolution. uv uses them to bypass the expensive resolution phase entirely if the input hasn’t changed.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Serialization (Serde)

- Converting Rust structs to TOML/JSON.

- Using

#[derive(Serialize, Deserialize)].

- Determinism

- Why do we sort the list of packages before saving? (Answer: To avoid git diff noise).

- Integrity Hashes

- Storing a hash of the package content in the lockfile to prevent “dependency confusion” attacks.

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Sorting

- Which fields should be used to sort the package list? (Name? Version?).

- Recursive Structure

- How do you represent dependencies in the lockfile? (Strings? Inline tables?).

- The Global Hash

- How do you calculate a single hash that represents the entire state of the lockfile?

Thinking Exercise

The Git Diff Nightmare

You have 100 packages. You generate a lockfile.

- Run A: Packages are in order [A, B, C].

- Run B: Packages are in order [C, B, A].

Question: If the content is the same, why is it vital for a tool like

uvto always output [A, B, C]? (Answer: To prevent merge conflicts and keep git history clean).

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is the difference between

pyproject.tomlanduv.lock?” - “Why use TOML instead of JSON for lockfiles?” (Hint: Human readability and diff-friendliness).

- “How does a lockfile help speed up CI/CD pipelines?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Serde and TOML

Use serde for the data structures and toml for the string conversion.

Hint 2: The BTreeMap

Use std::collections::BTreeMap for dependencies to ensure they are always sorted alphabetically in the output.

Hint 3: Deterministic Sorting

packages.sort_by(|a, b| a.name.cmp(&b.name));

Hint 4: Metadata Section

Include a [metadata] section at the bottom to store a hash of the pyproject.toml that generated the lock.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Serialization | Programming Rust | Ch. 10: “Enums and Patterns” (for data modeling) |

| Determinism | The Pragmatic Programmer | Ch. 2: “A Pragmatic Approach” |

| TOML Spec | TOML Official Documentation | Complete Spec |

Project 8: Python Interpreter Finder (Discovery)

- Main Programming Language: Rust

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: System Paths, Environment Variables, File Metadata

What you’ll build: A tool that scans the system PATH and common installation directories to find and identify every installed Python version.

Real World Outcome

You’ll create python-find. It will output a clean list of interpreters, their versions, and their architecture.

$ ./python-find

Found 3 Interpreters:

1. /usr/bin/python3 (3.12.1) [System]

2. /opt/homebrew/bin/python3.11 (3.11.5) [Homebrew]

3. ~/.pyenv/versions/3.10.12/bin/python (3.10.12) [Pyenv]

The Core Question You’re Answering

“Where does Python actually live on my machine, and how do I find the ‘right’ one?”

There is no single “Python path.” uv has to be smart enough to find Pythons from Homebrew, Pyenv, Conda, and the system.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- The

PATHEnvironment Variable- How to parse a string separated by

:or;.

- How to parse a string separated by

- File Permissions

- How to check if a file is “executable”.

- Subprocess Execution

- Running

python --versionand capturing the output reliably.

- Running

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Exhaustive Search vs Fast Search

- Should you scan the whole disk? (No). What are the standard paths for macOS vs Linux?

- Validating the Binary

- A file named

pythonmight be a shell script or a broken symlink. How do you verify it’s a real interpreter?

- A file named

- Version Extraction

- Some pythons output version to

stdout, others tostderr. How do you handle both?

- Some pythons output version to

Thinking Exercise

The Path Shadowing

You have /usr/local/bin/python (v3.11) and /usr/bin/python (v3.8).

Question: If your PATH is /usr/bin:/usr/local/bin, which one runs when you type python? Why? (Answer: /usr/bin/python, because search is sequential).

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is the difference between

pythonandpython3binaries on most systems?” - “How would you find Python on Windows without using the

PATH?” (Hint: Registry keys). - “Why does

uvprefer finding an existing Python over installing a new one?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Use std::env::var("PATH")

Split it by the OS-specific separator (: on Unix, ; on Windows).

Hint 2: is_executable

On Unix, use the std::os::unix::fs::PermissionsExt trait to check the execute bit.

Hint 3: Search common paths

Don’t just trust PATH. Look in /usr/bin, /usr/local/bin, ~/.pyenv/versions, and /opt/homebrew/bin.

Hint 4: Cache the results

Scanning can take 100ms. Save the results to a JSON file and only re-scan if the PATH changes.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Environment Variables | How Linux Works | Ch. 2: “The Shell” |

| Rust Subprocesses | Programming Rust | Ch. 18: “Foreign Functions” |

| Windows Registry | Windows Internals | Ch. 4: “Management Mechanisms” |

Project 9: Universal CLI (UX)

- Main Programming Language: Rust

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: CLI Design, Argument Parsing, Subcommands

- Software or Tool:

clapcrate

What you’ll build: A unified CLI interface with subcommands like run, install, and sync, using high-performance parsing.

Real World Outcome

You’ll create a tool my-uv that feels professional. It will have help text, auto-completions, and a “clean” interface.

$ ./my-uv --help

A fast Python package manager.

Usage: my-uv [COMMAND]

Commands:

install Install dependencies from pyproject.toml

sync Synchronize the venv with the lockfile

run Run a command in the venv

help Print this message or the help of the given subcommand(s)

$ ./my-uv install --verbose

[INFO] Resolving dependencies...

[INFO] Materializing venv...

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do I build a tool that is powerful yet simple to use for humans?”

A tool’s speed doesn’t matter if the interface is confusing. uv excels by providing a single binary that replaces 5 different tools.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Subcommands

- Why structure a CLI like

git <command>instead of 50 different flags?

- Why structure a CLI like

- The

clapDerive API- How to use Rust structs to define your CLI interface.

- ANSI Colors & Progress Bars

- How to provide feedback to the user without slowing down the core logic.

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Global vs Local Flags

- Should

--verboseapply to all commands or justinstall?

- Should

- Error Formatting

- How do you print errors so they are helpful? (e.g., “File not found” vs “Error: Os { code: 2, .. }”).

- Performance

- Does adding a big CLI library slow down your 5ms startup goal? (Hint:

clapis very fast, but watch out for binary size).

- Does adding a big CLI library slow down your 5ms startup goal? (Hint:

Thinking Exercise

The UX Flow

Imagine you are a developer. You just cloned a project.

- Pip Flow: Create venv -> activate -> pip install -> pip install dev-requirements.

- uv Flow:

uv sync. Question: How does your CLI design reduce the number of commands a user has to remember?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What are the advantages of using a ‘Single Binary’ approach for developer tools?”

- “How would you implement auto-completion for a custom CLI tool?”

- “Explain the ‘Rule of Silence’ in Unix CLI design.”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Use clap with the derive feature

#[derive(Parser)]

struct Cli {

#[command(subcommand)]

command: Commands,

}

Hint 2: The run subcommand

The run command should take a variable number of arguments (e.g., my-uv run python main.py). Use trailing_var_arg = true in clap.

Hint 3: Use miette or anyhow

For beautiful error reporting, use the miette crate. It allows you to point to specific lines in a pyproject.toml where a syntax error occurred.

Hint 4: Progress Bars

Use the indicatif crate for progress bars, but make sure they don’t print if the output is not a TTY (e.g., in CI).

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| CLI Design | The Art of Unix Programming | Ch. 11: “Interfaces” |

| Rust CLI | Command-Line Rust | Ch. 1: “Getting Started” |

| UX for Devs | The Design of Everyday Things | Ch. 1 |

Project 10: Metadata Pipelining (Range Requests)

- Main Programming Language: Rust

- Difficulty: Level 4: Expert

- Knowledge Area: HTTP Range Requests, ZIP Directory Parsing, Binary I/O

What you’ll build: A tool that uses HTTP Range requests to read the METADATA file of a remote Wheel on PyPI without downloading the entire archive.

Real World Outcome

You’ll create remote-peek. It will tell you the dependencies of a 500MB wheel (like tensorflow) by only downloading ~10KB of data.

$ ./remote-peek https://pypi.org/.../tensorflow-2.15.0-cp311...whl

[Remote ZIP Analysis]

1. Fetching last 22 bytes... Found EOCD.

2. Fetching Central Directory (Offset 498MB, Size 50KB)...

3. Locating METADATA... Found at Offset 12MB.

4. Fetching 5KB at Offset 12MB...

[Results]

Tensorflow 2.15.0 depends on: numpy, absl-py, etc.

Total Data Downloaded: 65 KB (0.01% of file size!)

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do I ‘search’ a file that I don’t actually have on my disk?”

This is the ultimate speed hack. uv combines Project 1 (ZIP Parsing) with Project 3 (Networking) to peek inside files across the internet.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- HTTP

RangeHeaderRange: bytes=-22(get last 22 bytes).Range: bytes=100-200(get specific slice).

- Network Latency vs Bandwidth

- Why is doing 3 small requests sometimes better than 1 big download?

- The ZIP End-of-Central-Directory (EOCD)

- Understanding that the “map” of the ZIP is always at the end.

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Calculating Offsets

- If the EOCD says the directory is at offset X, how do you handle the case where the server doesn’t support Range requests? (Fallback to full download).

- State Management

- How do you keep the HTTP connection open between the 3 different “jumps”?

- Security

- How do you verify the metadata is authentic without downloading the whole file? (Hint: check the hash of the range if available).

Thinking Exercise

The Cloud Economy

You have 100 dependencies to resolve. Each wheel is 100MB.

- Standard pip: 100 * 100MB = 10GB downloaded just to check versions.

- uv Range Peeking: 100 * 100KB = 10MB downloaded.

Question: How much faster is the

uvapproach on a typical 100Mbps home internet? (Answer: ~100x faster).

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is an HTTP Range request and how does it relate to ZIP files?”

- “Why might a Range request fail even if the URL is correct?”

- “How would you handle a ZIP file that is larger than 4GB (Zip64)?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Use reqwest with Headers

let res = client.get(url)

.header("Range", "bytes=-22")

.send().await?;

Hint 2: The EOCD structure The last 22 bytes of a ZIP contain the “offset to start of central directory” at bytes 16-20 (little-endian).

Hint 3: Async Streams

Instead of res.text(), use res.bytes() to get the raw binary data.

Hint 4: Binary Parsing

Use the byteorder crate to read integers from the binary buffer (ZIP headers are Little Endian).

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| HTTP Protocols | TCP/IP Illustrated | Ch. 20: “HTTP” |

| ZIP Internals | Write Great Code, Volume 1 | Ch. 3 |

| Rust Binary Parsing | Programming Rust | Ch. 15 |

Project 11: The Incremental Builder

- Main Programming Language: Rust

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: File Metadata, Caching Strategies, Invalidation

What you’ll build: A tool that checks if pyproject.toml or uv.lock has changed and exits in <0.01s if no work is needed.

Real World Outcome

You’ll create is-up-to-date. It’s a “gatekeeper” tool. If you run it twice, the second time is nearly instantaneous.

$ ./is-up-to-date

[Checking] pyproject.toml hash changed.

[Action] Running resolution...

Done.

$ ./is-up-to-date

Everything up to date. (Exited in 0.002s)

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do I avoid doing any work at all if the state hasn’t changed?”

The fastest code is the code that never runs. uv is famous for its “no-op” speed.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- mtime (Modification Time)

- Why checking file timestamps is faster than hashing.

- Why timestamps can be unreliable (e.g., in CI or git clones).

- State Persistence

- Where to store the “last known good” hash. (Hint:

~/.cache/my-uv/state.json).

- Where to store the “last known good” hash. (Hint:

- Merkle Trees (Conceptual)

- How a single hash can represent a collection of many files.

Questions to Guide Your Design

- The Comparison Logic

- Should you compare hashes or timestamps first? (Hint: Timestamps first, then hash if timestamp changed).

- The “Freshness” Check

- What happens if the venv folder was deleted manually but the

pyproject.tomlhasn’t changed? Your tool needs to check for the existence of the output too.

- What happens if the venv folder was deleted manually but the

- Locking

- What if two processes try to check freshness at the same time?

Thinking Exercise

The CI/CD Bill

Your company runs 1,000 builds a day. Each build takes 1 minute to “check” dependencies.

- Without Incrementalism: 1,000 minutes = 16 hours of compute time.

- With Incrementalism: 1,000 * 0.01s = 10 seconds of compute time. Question: How much money did Project 11 save the company?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “Why is checking Modification Time (mtime) faster than reading the file content?”

- “What are the pitfalls of relying on mtime in a distributed environment like Git?”

- “How would you design a ‘Build Cache’ that works across different developer machines?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Use std::fs::metadata

This returns the Metadata struct which contains modified().

Hint 2: Store a manifest

Save a small JSON file that maps filename -> (size, mtime, sha256).

Hint 3: Fast-Path vs Slow-Path

- Fast-path: All files exist and mtimes match manifest -> EXIT.

- Slow-path: Recalculate hashes of changed files. If hashes match -> EXIT.

- If hashes changed -> RUN PROJECT 12.

Hint 4: Check the Venv

Don’t forget to check if the .venv/bin/python actually exists. If it’s gone, the state is invalid regardless of hashes.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Build Systems | The GNU Make Book | Ch. 1: “How Make Works” |

| Filesystem Metadata | The Linux Programming Interface | Ch. 15: “File Attributes” |

| Performance | Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective | Ch. 6: “The Memory Hierarchy” |

Project 12: Mini-UV (The Final Integration)

- Main Programming Language: Rust

- Difficulty: Level 5: Master

- Knowledge Area: Software Architecture, Integration Testing, Systems Programming

What you’ll build: Combine Projects 1-11 into a single tool that resolves, downloads, caches, and materializes a virtual environment.

Real World Outcome

You’ll have your own functional package manager. It won’t have all the features of uv, but it will be able to install a real project with real dependencies using all the performance tricks you’ve learned.

$ ./mini-uv sync

1. Found 3 Pythons. Using 3.12.

2. Checking pyproject.toml... Changed.

3. Resolving graph (PubGrub)...

- requests 2.31.0

- urllib3 2.0.7

4. Peeking remote wheels... OK.

5. Downloading & Hashing... (Parallel)

6. Materializing Venv (Reflinks)... OK.

Done in 0.8s!

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do I orchestrate complex, independent modules into a high-performance system?”

This is where you learn “Systems Engineering.” How to make the Networking module talk to the Logic Solver, and the Cache module talk to the Filesystem module.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Trait-Based Architecture

- Using traits to swap out the “Real Filesystem” for a “Mock Filesystem” in tests.

- Dependency Injection

- How to pass the Cache handle to the Downloader.

- Error Propagation

- Using

?and custom Error types to ensure a network failure in a thread is reported correctly to the main UI.

- Using

Questions to Guide Your Design

- The Pipeline

- Should you resolve the whole graph before downloading anything, or download as you find new dependencies? (Hint:

uvdoes “Metadata Pipelining”).

- Should you resolve the whole graph before downloading anything, or download as you find new dependencies? (Hint:

- Concurrency management

- How do you ensure the UI (Progress Bars) stays smooth while the Logic Solver is crunching numbers in a background thread?

- Logging & Debugging

- How do you implement a

--verboseflag that shows exactly which performance trick was used for each file?

- How do you implement a

Thinking Exercise

The Architect’s Review

Look at your finished mini-uv.

- Which part is the “Bottleneck”?

- If you had to make it 2x faster, where would you start?

- How much of the speed comes from Rust, and how much comes from the design?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “Walk me through the lifecycle of a package installation in your tool.”

- “How did you ensure thread safety when multiple tasks write to the global cache?”

- “What was the hardest bug you encountered when integrating the Logic Solver with the Downloader?”

- “If you had to port this to Windows, what would be your biggest challenge?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Create a Context struct

Store the shared state (Cache path, HTTP Client, Semaphore) in a Context and pass it around.

Hint 2: Define a “Package” Lifecycle

- Specifier -> 2. Resolved Version -> 3. Metadata -> 4. Cached Wheel -> 5. Materialized Files.

Hint 3: Async/Sync Bridge

The Resolver (PubGrub) might be CPU-bound (Sync), but the Downloader is I/O-bound (Async). Use tokio::task::spawn_blocking for the Resolver.

Hint 4: Test with a small project

Create a pyproject.toml with only 2 dependencies (e.g., requests and idna) and get the full flow working before adding more complexity.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Software Architecture | Clean Architecture | Ch. 1: “Design and Architecture” |

| Systems Design | Fundamentals of Software Architecture | Part II: “Architecture Styles” |

| Integration | The Pragmatic Programmer | Ch. 5: “Bend, or Break” |

| Rust Integration | Rust for Rustaceans | Ch. 1: “Foundations” |

Project Comparison Table

| Project | Difficulty | Time | Depth | Fun Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metadata Parser | 2 | Weekend | High | 4/5 |

| Reflink Explorer | 4 | 1 week | Extreme | 5/5 |

| PubGrub Solver | 5 | 2 weeks | Deep | 5/5 |

| Async Resolver | 3 | 1 week | Medium | 4/5 |

| Mini-UV | 5 | 1 month | Full | 5/5 |

Recommendation

Start with Project 1 (Metadata Parser). It teaches you that binary formats are just maps you need to navigate and sets the stage for efficient I/O.

Final Overall Project: The “Project Ghost”

Build a tool that can “instantly” restore a Python environment for any git commit in a repository using a global cache and reflinks.

Summary

| # | Project Name | Language | Difficulty | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Metadata Parser | Rust | Beginner | Weekend |

| 2 | Reflink Explorer | Rust | Advanced | 1 week |

| 3 | Async Resolver | Rust | Advanced | 1 week |

| 4 | PubGrub Solver | Rust | Master | 2 weeks |

| 5 | Cache System | Rust | Intermediate | Weekend |

| 6 | Venv Factory | Rust | Intermediate | Weekend |

| 7 | Lockfile Gen | Rust | Intermediate | Weekend |

| 8 | Interpreter Finder | Rust | Intermediate | Weekend |

| 9 | Universal CLI | Rust | Intermediate | Weekend |

| 10 | Range Requests | Rust | Expert | 1 week |

| 11 | Incremental Builder | Rust | Advanced | 1 week |

| 12 | Mini-UV | Rust | Master | 1 month |

Expected Outcomes

After completing these projects, you will:

- Master Rust’s

tokiofor high-performance networking. - Understand low-level filesystem CoW (copy-on-write).

- Be able to implement complex SAT-solver-like algorithms (PubGrub).

- Know how to optimize binary file access to save I/O.

- Understand the “Why” behind the fastest developer tools in the world.