Learn The Art of Computer Programming: From Zero to Knuth Master

Goal: Build a working, internal model of TAOCP that goes beyond reading proofs. You will implement the core algorithms, data structures, and mathematical tools Knuth relies on, then validate them with empirical experiments and careful analysis. By the end, you will be able to translate TAOCP’s MIX/MMIX-style descriptions into real, correct, and efficient code, reason about performance with rigorous asymptotics, and explain why each algorithm works. The projects are sequenced to mirror the volumes: foundations first, then data structures, randomization, arithmetic, sorting/searching, and combinatorial methods.

Why TAOCP Matters

“The Art of Computer Programming” is widely considered the most comprehensive and rigorous work on computer science ever written. Bill Gates famously said, “If you think you’re a really good programmer… read Knuth’s Art of Computer Programming… You should definitely send me a résumé if you can read the whole thing.”

TAOCP teaches you to:

- Think mathematically about algorithms—analyzing their efficiency precisely

- Understand computers at the deepest level—from machine instructions to abstract algorithms

- Develop problem-solving skills that separate great programmers from good ones

- Master fundamental techniques that underpin all of computer science

The Practical Why

TAOCP is not a book of trivia. It is a machine for building transferable mental models:

- When a system slows down, you can reason about whether the cause is algorithmic growth, data structure shape, or memory layout.

- When you need a random generator, you will know how to test it rather than trust it.

- When you implement a search structure, you will know the exact invariants that keep it fast.

- When you compare algorithms, you will be able to quantify why one wins in practice.

This matters because real systems are built from these primitives. Databases depend on B-trees. Compilers depend on trees and symbol tables. Security depends on precise arithmetic and bit manipulation. Performance depends on choosing the right algorithm for the input distribution. TAOCP is the source code for all of that.

After completing these projects, you will:

- Understand algorithm analysis using Knuth’s rigorous mathematical framework

- Be able to implement any data structure from first principles

- Know the theory behind random number generation and can test for randomness

- Master every major sorting and searching algorithm with their trade-offs

- Solve hard combinatorial problems using backtracking and SAT solvers

- Have implemented a working RISC computer (MMIX) to truly understand machines

The Big Picture: From Math to Machine

TAOCP is a single story told at multiple layers. The projects are designed to make that story visible:

Mathematics ──► Algorithms ──► Data Structures ──► Machine Model ──► Performance

| | | | |

proofs procedures invariants MMIX code analysis

If you can move left to right in this pipeline, you can turn a theorem into working code. If you can move right to left, you can explain why a program behaves the way it does. This is the core skill TAOCP builds.

How the projects map to the pipeline:

- Math Toolkit + Randomness build the proof and analysis layer.

- Data Structures + Trees + Sorting build the invariants and algorithm layer.

- MMIX + Arithmetic build the machine model layer.

- Combinatorics + SAT build the search and optimization layer.

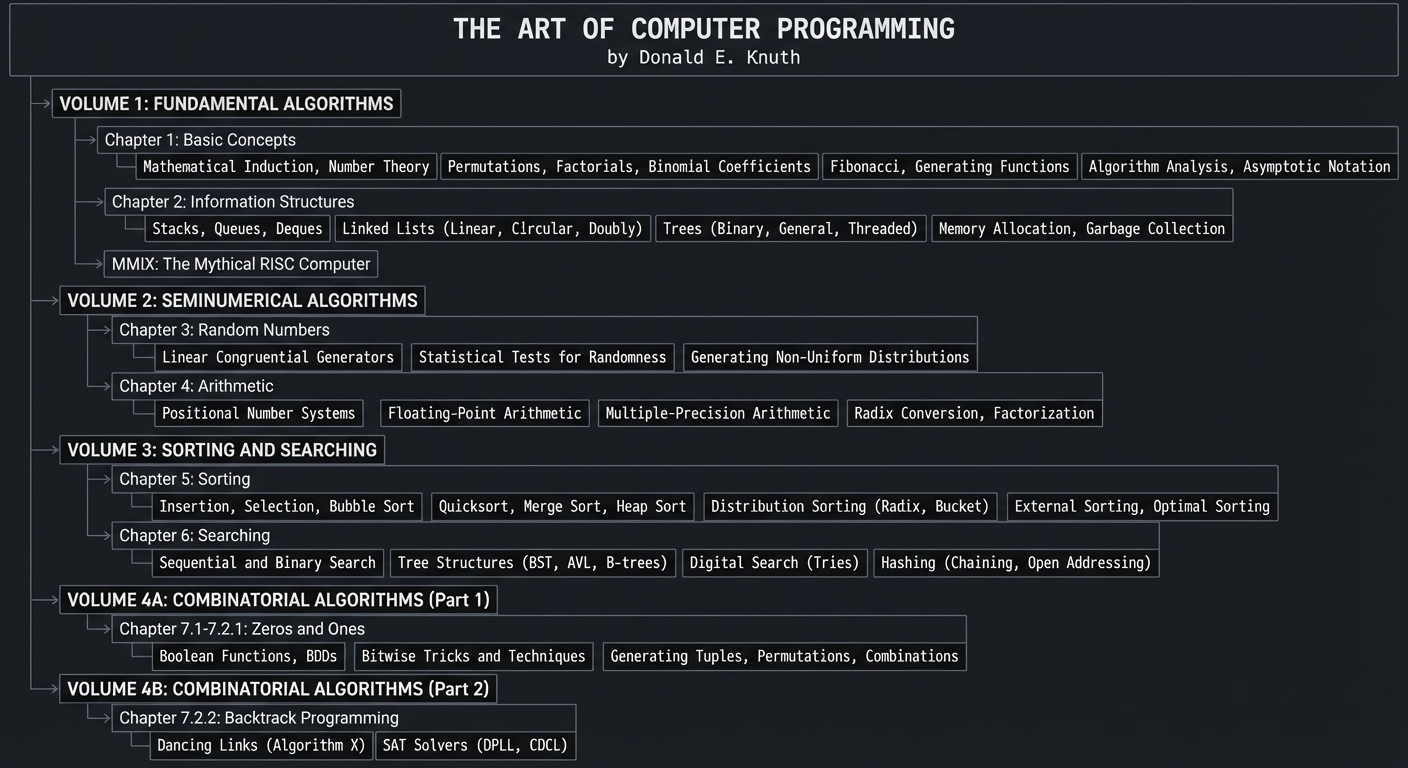

TAOCP Volume Overview

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ THE ART OF COMPUTER PROGRAMMING │

│ by Donald E. Knuth │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ VOLUME 1: FUNDAMENTAL ALGORITHMS │

│ ├── Chapter 1: Basic Concepts │

│ │ ├── Mathematical Induction, Number Theory │

│ │ ├── Permutations, Factorials, Binomial Coefficients │

│ │ ├── Fibonacci, Generating Functions │

│ │ └── Algorithm Analysis, Asymptotic Notation │

│ ├── Chapter 2: Information Structures │

│ │ ├── Stacks, Queues, Deques │

│ │ ├── Linked Lists (Linear, Circular, Doubly) │

│ │ ├── Trees (Binary, General, Threaded) │

│ │ └── Memory Allocation, Garbage Collection │

│ └── MMIX: The Mythical RISC Computer │

│ │

│ VOLUME 2: SEMINUMERICAL ALGORITHMS │

│ ├── Chapter 3: Random Numbers │

│ │ ├── Linear Congruential Generators │

│ │ ├── Statistical Tests for Randomness │

│ │ └── Generating Non-Uniform Distributions │

│ └── Chapter 4: Arithmetic │

│ ├── Positional Number Systems │

│ ├── Floating-Point Arithmetic │

│ ├── Multiple-Precision Arithmetic │

│ └── Radix Conversion, Factorization │

│ │

│ VOLUME 3: SORTING AND SEARCHING │

│ ├── Chapter 5: Sorting │

│ │ ├── Insertion, Selection, Bubble Sort │

│ │ ├── Quicksort, Merge Sort, Heap Sort │

│ │ ├── Distribution Sorting (Radix, Bucket) │

│ │ └── External Sorting, Optimal Sorting │

│ └── Chapter 6: Searching │

│ ├── Sequential and Binary Search │

│ ├── Tree Structures (BST, AVL, B-trees) │

│ ├── Digital Search (Tries) │

│ └── Hashing (Chaining, Open Addressing) │

│ │

│ VOLUME 4A: COMBINATORIAL ALGORITHMS (Part 1) │

│ └── Chapter 7.1-7.2.1: Zeros and Ones │

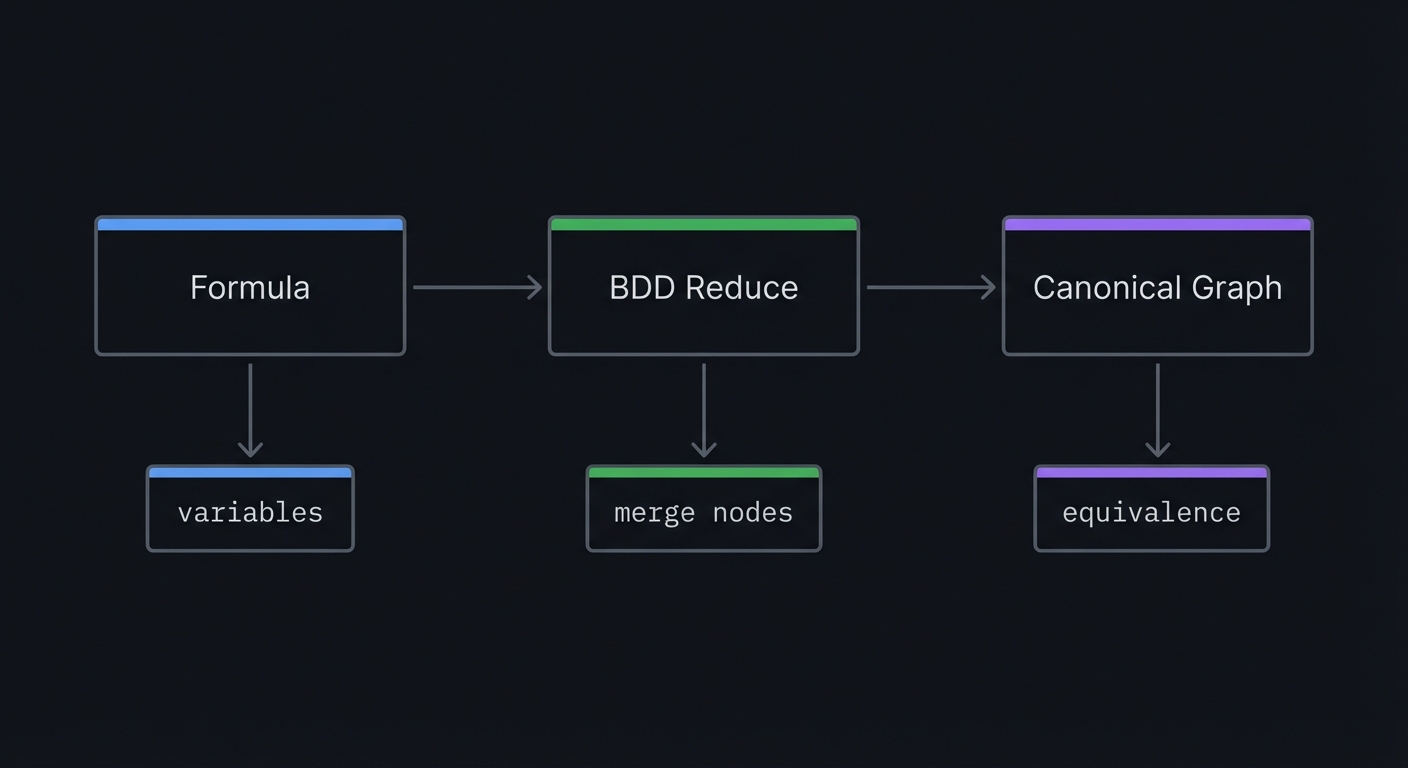

│ ├── Boolean Functions, BDDs │

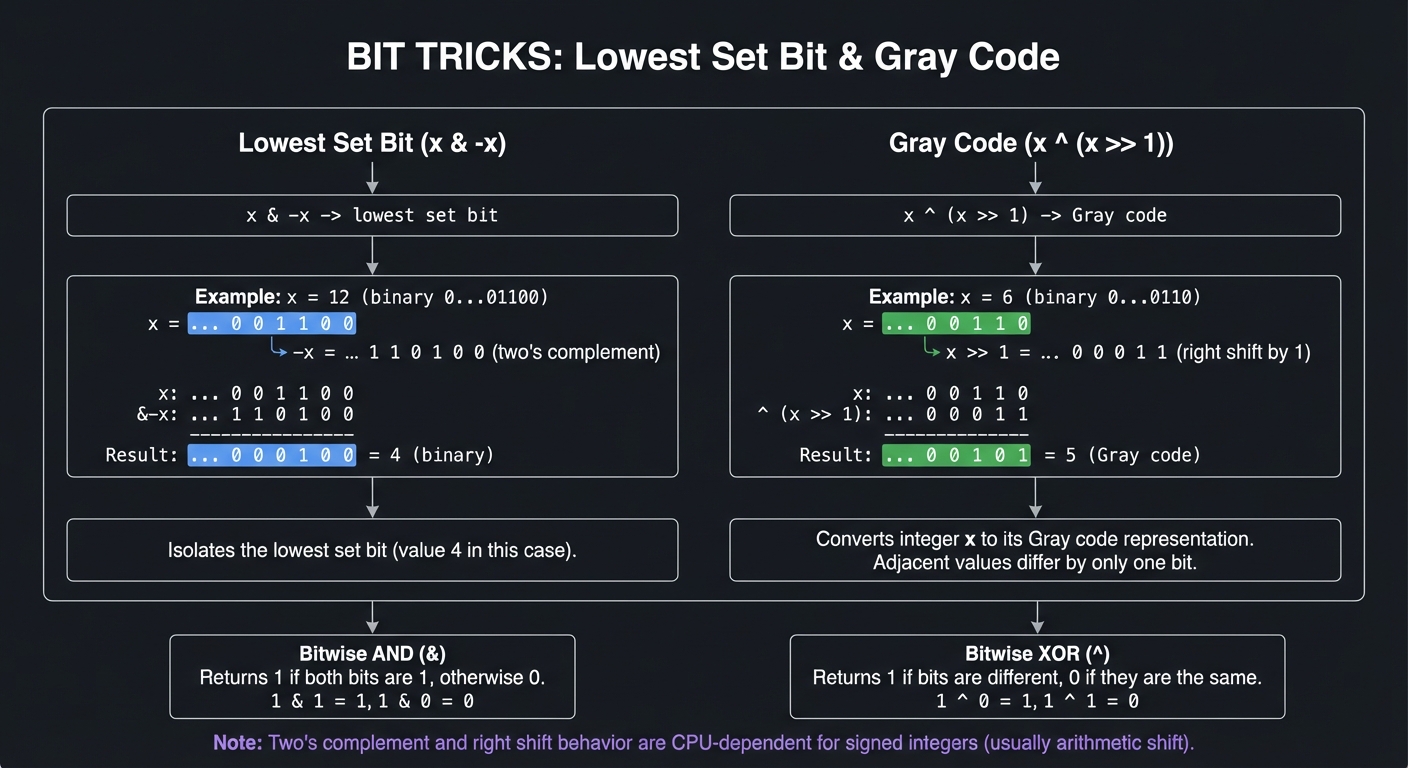

│ ├── Bitwise Tricks and Techniques │

│ └── Generating Tuples, Permutations, Combinations │

│ │

│ VOLUME 4B: COMBINATORIAL ALGORITHMS (Part 2) │

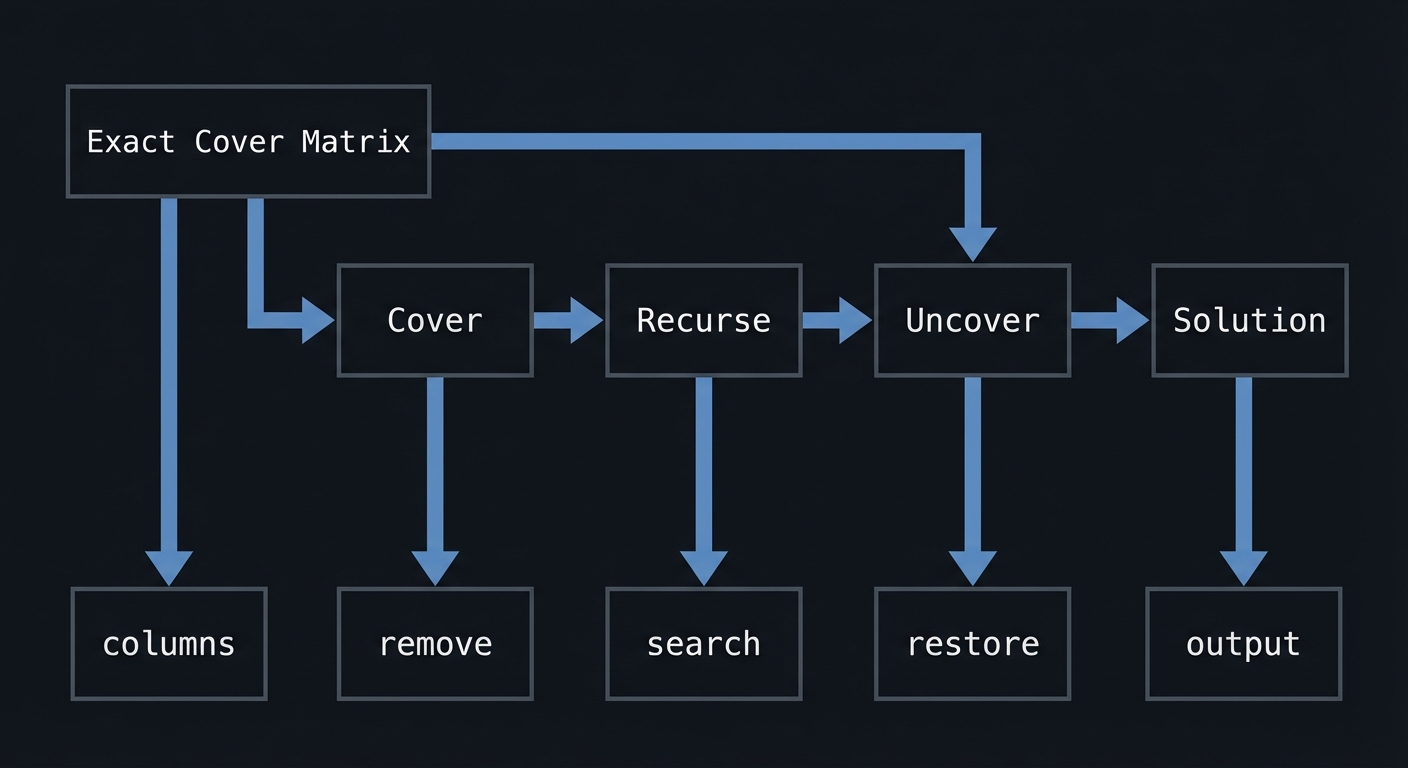

│ └── Chapter 7.2.2: Backtrack Programming │

│ ├── Dancing Links (Algorithm X) │

│ └── SAT Solvers (DPLL, CDCL) │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Knuth’s Exercise Difficulty Scale

TAOCP uses a unique rating system for exercises (0-50):

| Rating | Meaning |

|---|---|

| 00 | Immediate—you should see the answer instantly |

| 10 | Simple—a minute of thought should suffice |

| 20 | Medium—may take 15-20 minutes |

| 30 | Moderately hard—requires significant work |

| 40 | Quite difficult—term paper level |

| 50 | Research problem—unsolved or PhD-level |

| M | Mathematical—requires math beyond calculus |

| HM | Higher mathematics—graduate level math |

Our projects target concepts from exercises rated 10-40, making TAOCP accessible through practical implementation.

Prerequisites & Background Knowledge

Essential Prerequisites (Must Have)

- C programming fundamentals: pointers, structs, manual memory management, and file I/O.

- Discrete math basics: induction, summations, permutations/combinations, and modular arithmetic.

- Comfort with proofs: you should be able to follow a proof, even if you do not write them daily.

- Algorithm literacy: Big-O notation and basic data structures (arrays, linked lists, trees).

Helpful But Not Required

- Assembly exposure: even a short introduction helps when reading MMIX.

- Probability & statistics: useful for randomness and testing distributions.

- Numerical methods: helpful for Chapter 4 (arithmetic and precision).

Self-Assessment Questions

- Can you implement a linked list without memory leaks?

- Can you explain the difference between O(n log n) and O(n^2)?

- Can you follow a proof by induction and re-derive a result with small examples?

- Can you compute factorials, binomial coefficients, and Fibonacci numbers without a calculator?

Development Environment Setup

- Compiler:

gccorclangwith-Wall -Wextra -Werror - Build:

make(useMakefiles for repeatable experiments) - Plotting (optional): Python + matplotlib for performance charts

- Testing: a lightweight test harness (e.g., a

tests/directory + a single runner)

Time Investment

- Foundations: 2-4 weeks

- MMIX + data structures: 4-6 weeks

- Random numbers + arithmetic: 3-5 weeks

- Sorting/searching + combinatorics: 4-8 weeks

Important Reality Check

TAOCP is rigorous by design. Expect to revisit chapters multiple times. Your reward is a durable, machine-level understanding that transfers to any language or system you build later.

Core Concept Analysis

Think of TAOCP as six interlocking concept clusters. Each project reinforces one cluster while depending on the previous ones.

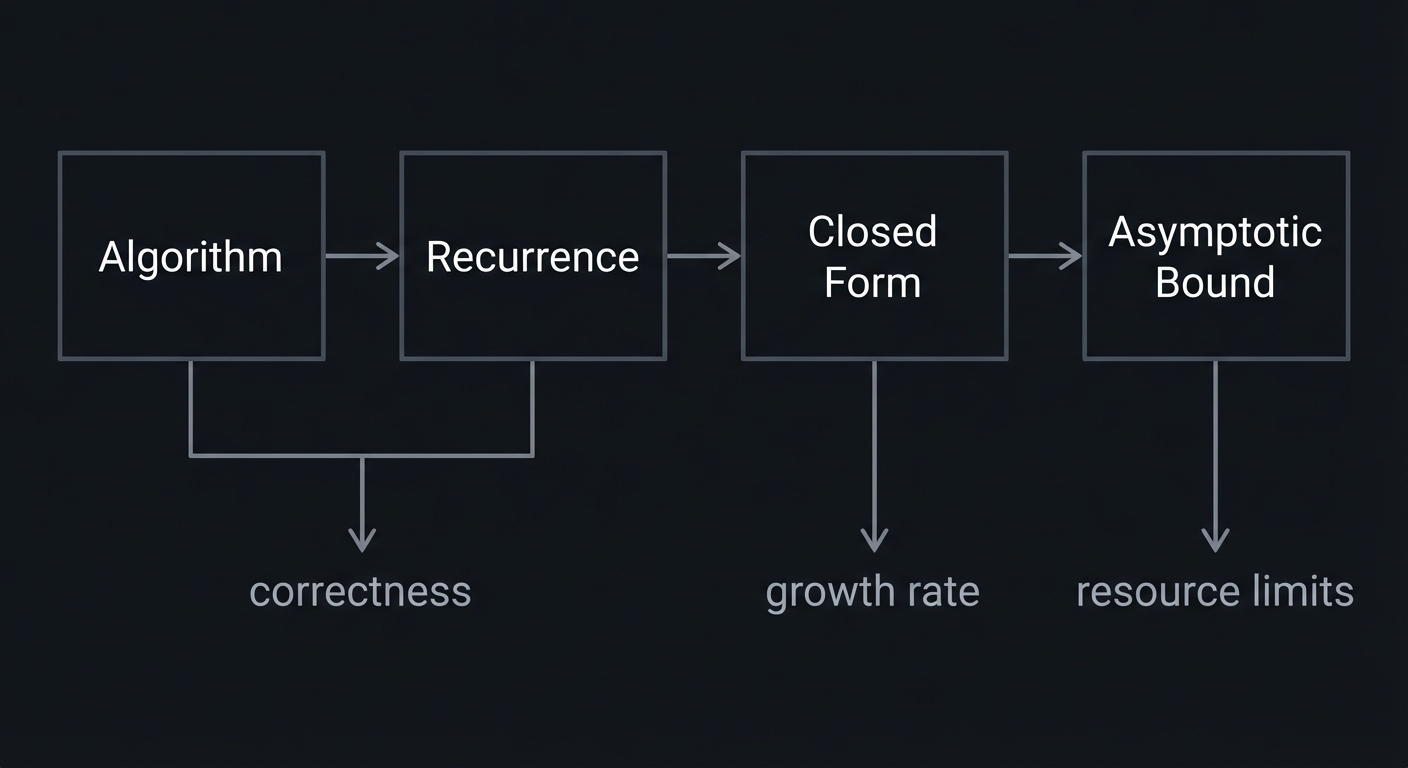

A. Mathematical Foundations and Analysis

Central question: How do you prove that an algorithm is correct and quantify its cost?

Key ideas:

- Asymptotic notation (O, Ω, Θ) and rigorous bounding

- Summations and recurrences for time analysis

- Generating functions to solve recurrence relations

- Induction as the default proof technique

What this unlocks:

- You can predict performance before writing code.

- You can explain why a slow algorithm fails at scale.

- You can justify correctness beyond “it seems to work.”

Algorithm → Recurrence → Closed Form → Asymptotic Bound

│ │ │ │

│ ▼ ▼ ▼

└────────── correctness growth rate resource limits

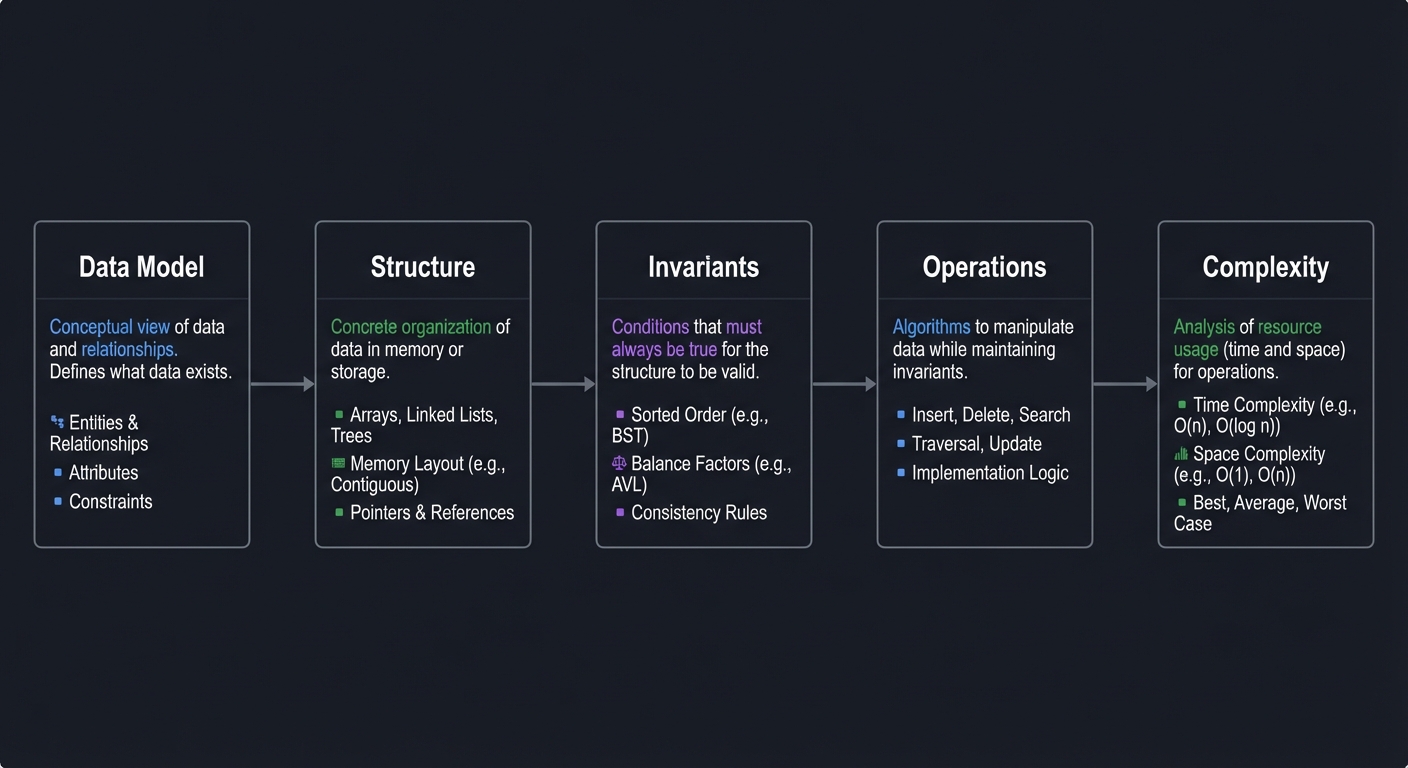

B. Information Structures and Memory

Central question: How do you represent data so operations are fast and predictable?

Key ideas:

- Stacks, queues, deques as fundamental building blocks

- Linked structures and pointer invariants

- Trees (binary, general, threaded) and traversal mechanics

- Storage allocation and garbage collection strategies

What this unlocks:

- You can reason about memory usage and locality.

- You can build robust, leak-free data structures.

- You can choose the right structure for the workload.

Data Model ──► Structure ──► Invariants ──► Operations ──► Complexity

C. Randomness and Experimental Validation

Central question: How do we generate randomness and validate its properties?

Key ideas:

- Linear congruential generators and period analysis

- Statistical tests (frequency, runs, serial correlation)

- Transforming distributions (uniform → non-uniform)

What this unlocks:

- You can test RNG quality instead of trusting it.

- You can build simulations and sampling pipelines confidently.

D. Arithmetic and Precision

Central question: How does the machine represent numbers and where does error creep in?

Key ideas:

- Radix representation and mixed-radix systems

- Multiple-precision arithmetic and carry propagation

- Floating-point error and rounding analysis

What this unlocks:

- You can build reliable numeric code.

- You can spot precision bugs and edge cases.

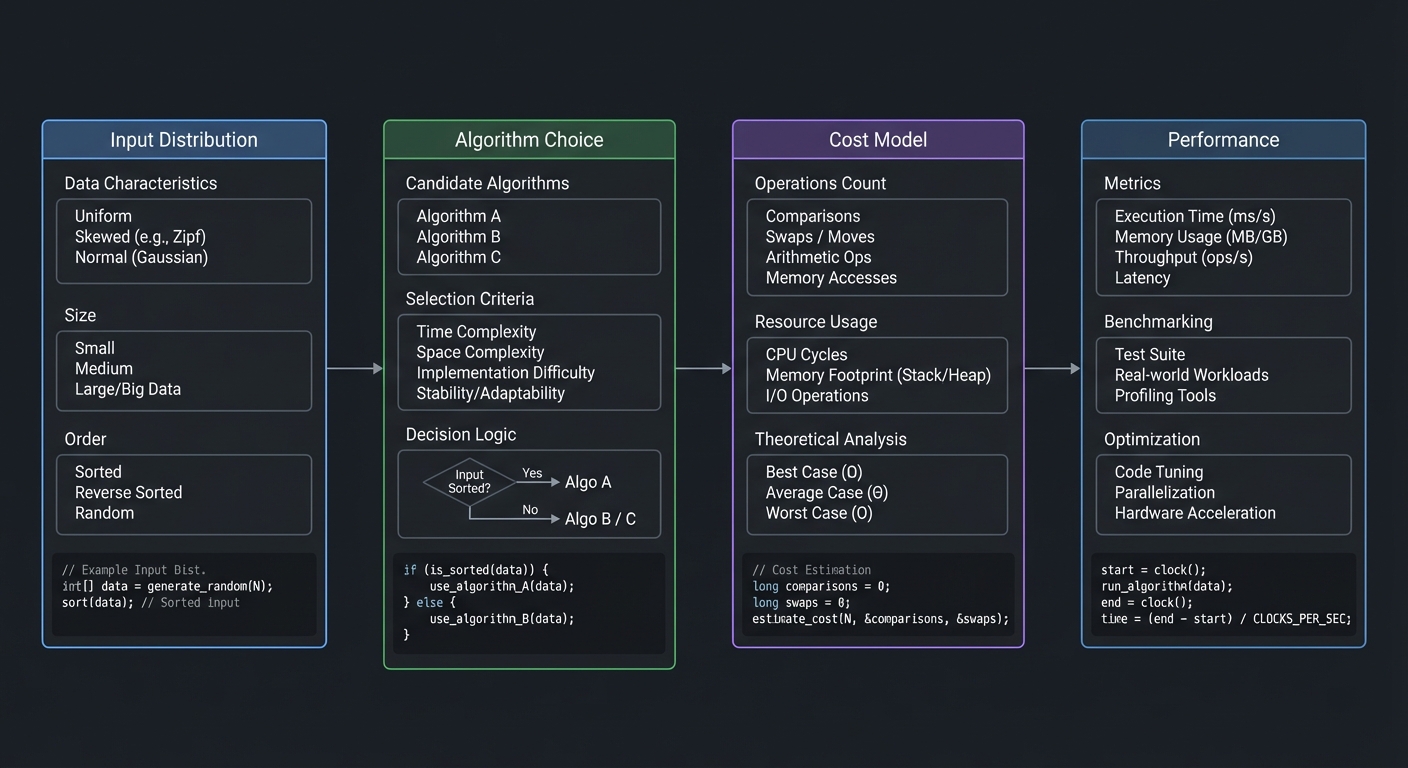

E. Sorting and Searching as Systems

Central question: Why do these algorithms actually behave the way the analysis predicts?

Key ideas:

- Distribution vs comparison sorting

- Tree-based searching and balancing

- Hashing and collision behavior

What this unlocks:

- You can select algorithms based on data distribution, not habit.

- You can quantify when a data structure stops scaling.

Input Distribution ──► Algorithm Choice ──► Cost Model ──► Performance

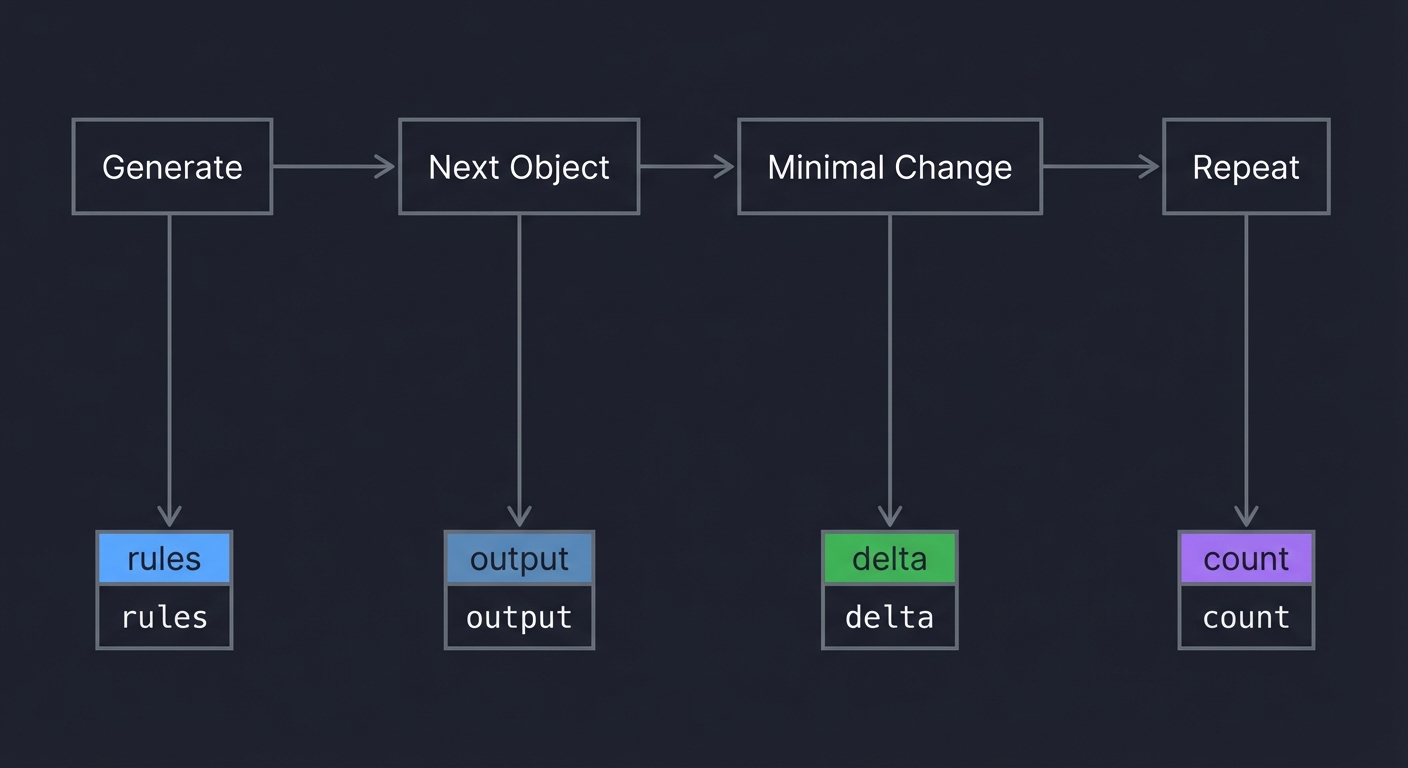

F. Combinatorial Algorithms and Backtracking

Central question: How do you explore enormous search spaces efficiently?

Key ideas:

- Generating tuples/permutations/combinations

- Algorithm X and Dancing Links

- SAT solving strategies (DPLL/CDCL)

What this unlocks:

- You can model and solve constraint problems (Sudoku, scheduling, verification).

- You can build practical search tools with strong pruning.

Success Metrics (What “Mastery” Looks Like)

You can consider this track successful when you can:

- Explain any algorithm in TAOCP in plain language and derive its complexity.

- Implement the algorithm from scratch without external libraries.

- Test correctness with invariant checks and small exhaustive inputs.

- Predict performance trends as input size grows.

- Translate TAOCP’s MMIX descriptions into working code.

These are the same skills used in high-end systems, database, and compiler work.

How to Use This Guide

If you want to finish these projects, follow this workflow for each one:

- Read the Core Question and restate it in your own words.

- Skim the Concepts and look up any missing definitions immediately.

- Do the Thinking Exercise on paper first (it makes the code obvious).

- Implement in small layers and verify each layer with tests.

- Compare results to theory using the provided formulas or counts.

Golden rule: every project should end with both correctness proof and empirical validation. If you cannot validate, you do not yet understand it.

Definitions & Notation You Must Be Fluent In

- O(g(n)): upper bound on growth rate (worst-case ceiling).

- Ω(g(n)): lower bound (best-case floor).

- Θ(g(n)): tight bound (both upper and lower).

- [x] / ⌊x⌋ / ⌈x⌉: floor/ceiling operators.

- Σ / Π: summation and product notation used constantly in TAOCP.

- Invariant: a property that must remain true after every operation.

- Algorithm (Knuth’s sense): a finite sequence of precise, effective steps.

Concept Summary Table

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize |

|---|---|

| Mathematical Foundations | Translate algorithms into recurrences, solve them, and justify bounds. |

| Information Structures | Maintain pointer invariants and reason about storage costs. |

| Randomness & Tests | Generate random sequences and detect non-randomness with statistical checks. |

| Arithmetic & Precision | Implement number representations and quantify rounding error. |

| Sorting & Searching | Choose algorithms based on input distribution and cost models. |

| Combinatorial Methods | Generate and search large state spaces without brute-force explosion. |

| MMIX & Machine Model | Map abstract algorithms to a concrete machine and instruction set. |

Deep Dive Reading by Concept

| Concept | Primary TAOCP Source | Supporting Book |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical analysis | Volume 1, Ch. 1 | Concrete Mathematics Ch. 1-3 |

| Data structures | Volume 1, Ch. 2 | Algorithms in C Parts 1-4 |

| Random numbers | Volume 2, Ch. 3 | Algorithms in C Part 4 (Random) |

| Arithmetic | Volume 2, Ch. 4 | Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective Ch. 2 |

| Sorting/searching | Volume 3, Ch. 5-6 | Algorithms, 4th Edition Ch. 2-3 |

| Combinatorial algorithms | Volume 4A/4B, Ch. 7 | The Recursive Book of Recursion Ch. 7-9 |

| Machine model (MMIX) | Volume 1, Fascicle 1 | Write Great Code, Vol. 1 Ch. 3 |

Quick Start (First 48 Hours)

- Read TAOCP Vol. 1, Ch. 1 overview and skim the notation section.

- Implement a small math toolkit: factorial, binomial coefficients, and Fibonacci (iterative + fast).

- Write a tiny benchmarking harness to compare naive vs optimized approaches.

- Prove one lemma (e.g., sum of first n integers) with induction in your own words.

- Create a notes file that tracks definitions and symbols you encounter.

Recommended Learning Paths

Path A: Systems-first (if you like hardware)

- Project 1 (MMIX Simulator)

- Project 2 (Mathematical Toolkit)

- Projects on data structures and memory

- Sorting/searching projects

Path B: Math-first (if you like proofs)

- Project 2 (Mathematical Toolkit)

- Randomness + arithmetic projects

- Data structure projects

- MMIX simulator last

Path C: Interview/Industry-first

- Sorting and searching projects

- Data structures projects

- Randomness and testing

- Combinatorial algorithms

Project List

Projects are organized by TAOCP volume and chapter, building from foundations to advanced topics.

VOLUME 1: FUNDAMENTAL ALGORITHMS

Project 1: MMIX Simulator (Understand the Machine)

- File: LEARN_TAOCP_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, C++, Go

- Coolness Level: Level 5: Pure Magic

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 4: Expert

- Knowledge Area: Computer Architecture / Assembly / Emulation

- Software or Tool: Building: CPU Emulator

- Main Book: “The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 1, Fascicle 1: MMIX” by Donald E. Knuth

What you’ll build: A complete simulator for MMIX, Knuth’s 64-bit RISC computer architecture, capable of running MMIX assembly programs with full instruction set support.

Why it teaches TAOCP: All algorithms in TAOCP are presented in MMIX assembly language. To truly understand the book, you need to understand the machine. Building an MMIX simulator teaches you computer architecture from the ground up—registers, memory, instruction encoding, and execution.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Implementing 256 general-purpose registers → maps to register file design

- Decoding 256 instruction opcodes → maps to instruction set architecture

- Simulating memory with virtual addressing → maps to memory hierarchy

- Implementing special registers (rA, rD, etc.) → maps to processor state

Key Concepts:

- MMIX Architecture: “TAOCP Volume 1, Fascicle 1” - Donald E. Knuth

- Computer Organization: “Computer Organization and Design RISC-V Edition” Chapter 2 - Patterson & Hennessy

- Instruction Encoding: “The MMIX Supplement” - Martin Ruckert

- CPU Simulation: “Write Great Code, Volume 1” Chapter 3 - Randall Hyde

Resources for key challenges:

- Knuth’s MMIX Page - Official documentation

- GIMMIX Simulator - Reference implementation

Difficulty: Expert Time estimate: 3-4 weeks Prerequisites:

- Basic C programming

- Understanding of binary/hexadecimal

- Willingness to read Knuth’s MMIX specification

Real world outcome:

$ cat hello.mms

LOC #100

Main GETA $255,String

TRAP 0,Fputs,StdOut

TRAP 0,Halt,0

String BYTE "Hello, MMIX World!",#a,0

$ ./mmixal hello.mms # Assemble

$ ./mmix hello.mmo # Run

Hello, MMIX World!

$ ./mmix -t hello.mmo # Trace execution

1. 0000000000000100: e7ff0010 (GETA) $255 = #0000000000000110

2. 0000000000000104: 00000601 (TRAP) Fputs to StdOut

Hello, MMIX World!

3. 0000000000000108: 00000000 (TRAP) Halt

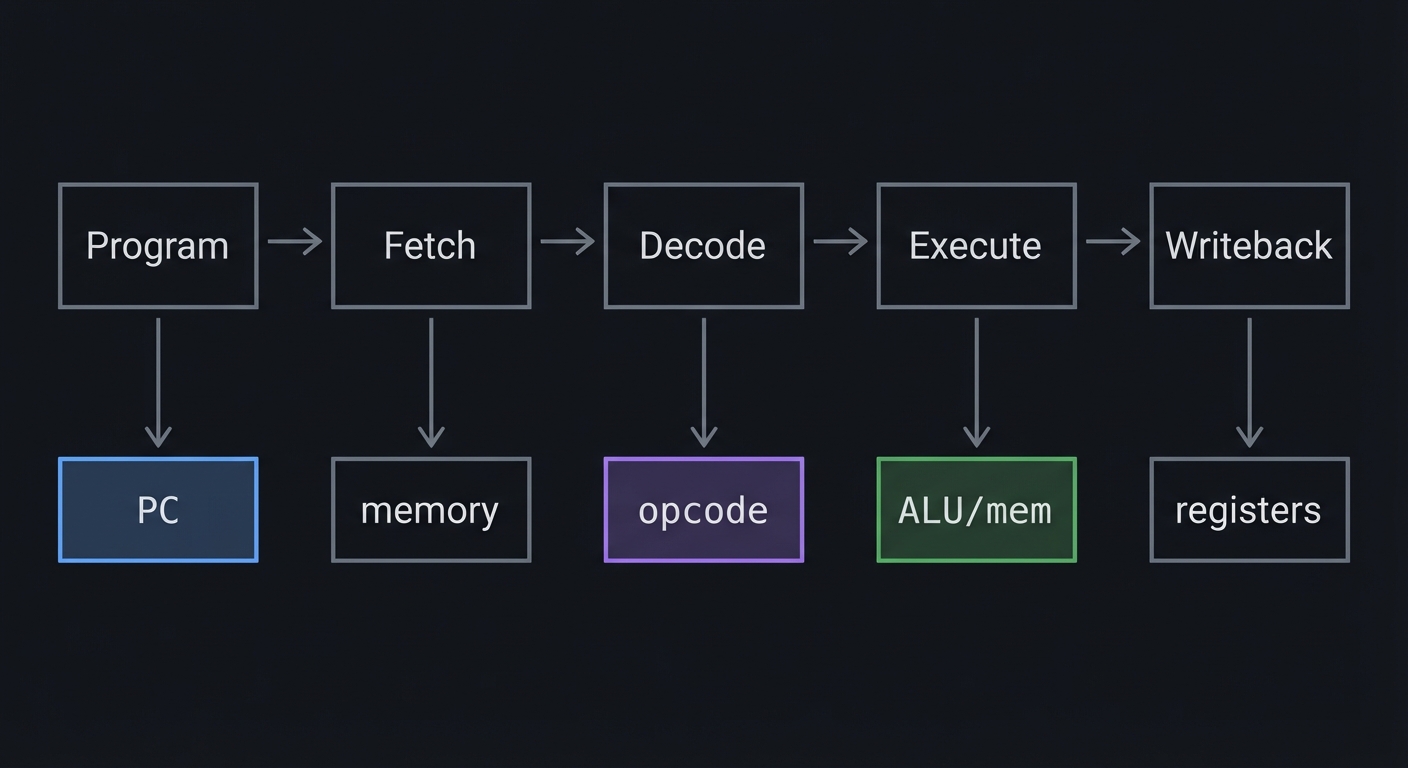

Visual Model

Program -> Fetch -> Decode -> Execute -> Writeback

| | | | |

PC memory opcode ALU/mem registers

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How does a concrete machine execute an algorithm step by step, and how do its rules shape every TAOCP program?”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Instruction encoding and field extraction (TAOCP Vol 1, Fascicle 1)

- Register files and program counter discipline

- Addressing modes, alignment, and byte order

- Traps, interrupts, and privileged behavior

- State invariants (what must remain true after every step)

Questions to Guide Your Design

- How will you represent memory so byte, wyde, tetra, and octa accesses are correct?

- What is your instruction decode strategy (table, switch, or data-driven)?

- How do you model special registers and side effects cleanly?

- How will you test correctness for each opcode without writing 256 bespoke tests?

Thinking Exercise

Hand-execute this microprogram by tracking registers and PC:

SETL $1,#0001

SETL $2,#0002

ADD $3,$1,$2

STOU $3,0($0)

What value ends up at address 0? What is PC after the last instruction?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- How do you decode and dispatch instructions efficiently?

- What is the difference between a trap and an interrupt?

- How would you validate emulator correctness?

- What are the classic endianness pitfalls?

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start Small Implement just memory, registers, PC, and a handful of opcodes (ADD, LDOU, STOU).

Hint 2: Build a Tiny Assembler Loader Parse a minimal subset of MMIXAL output to avoid full assembler complexity.

Hint 3: Add Traps as Function Hooks Map TRAP instructions to host callbacks for I/O.

Hint 4: Create a Golden Trace Use known instruction traces and compare register snapshots after each step.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| MMIX execution | TAOCP Vol 1, Fascicle 1 | Entire fascicle |

| CPU organization | Computer Organization and Design | Ch. 2-3 |

| Emulator structure | Write Great Code, Vol. 1 | Ch. 3 |

| Low-level execution | Low-Level Programming | Ch. 1-2 |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem: “Registers look correct but memory is wrong”

- Why: Endianness or misaligned access in loads/stores.

- Fix: Verify byte ordering with a known pattern (0x0102030405060708).

- Quick test: Store a constant, then load it byte-by-byte and compare.

Problem: “PC jumps unpredictably”

- Why: Forgetting to increment PC for non-branch instructions.

- Fix: Centralize PC increment and only override for branch/trap.

- Quick test: Run a straight-line program and verify PC progression by 4.

Implementation Hints:

MMIX register structure:

General registers: $0 - $255 (64-bit each)

Special registers:

rA - Arithmetic status

rB - Bootstrap register

rC - Continuation register

rD - Dividend register

rE - Epsilon register

rH - Himult register

rJ - Return-jump register

rM - Multiplex mask

rR - Remainder register

rBB, rTT, rWW, rXX, rYY, rZZ - Trip registers

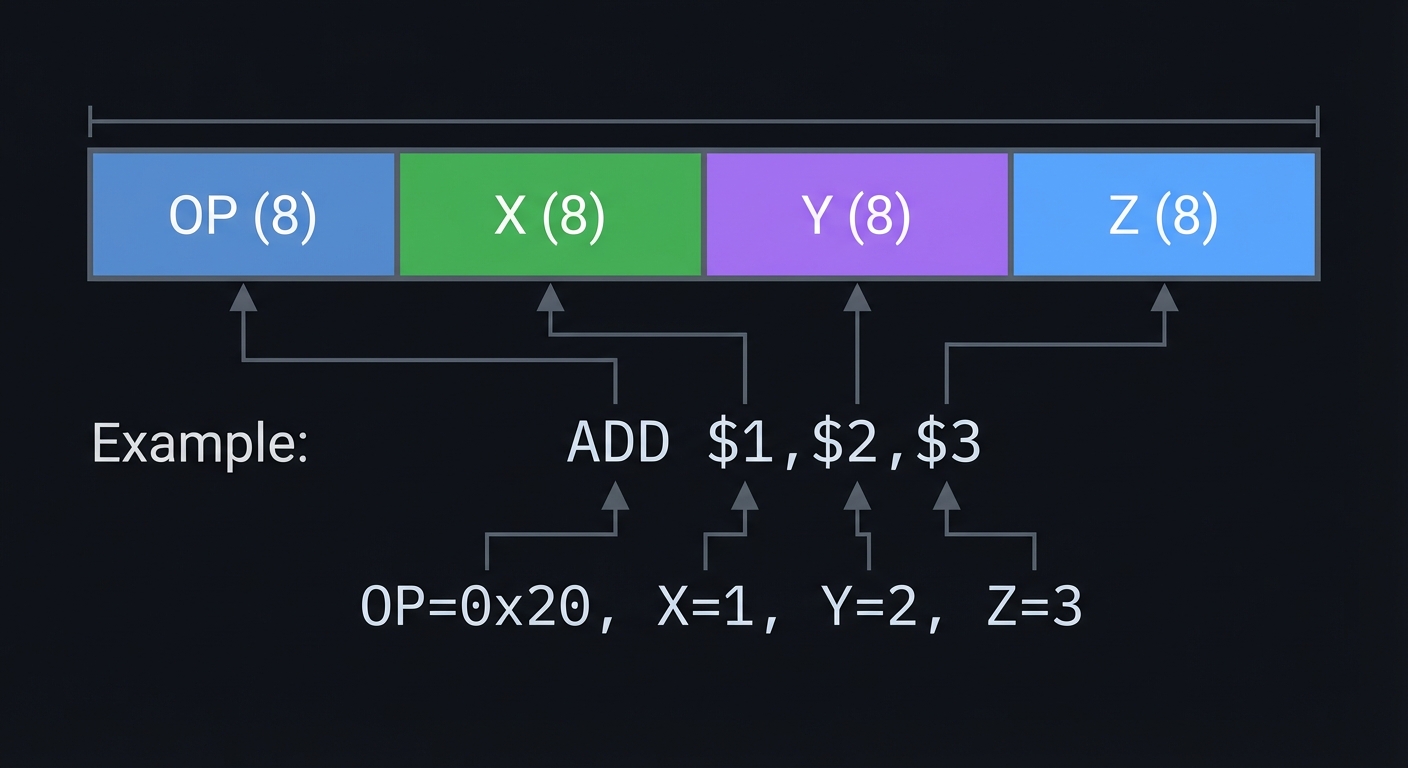

Instruction format (32 bits):

┌────────┬────────┬────────┬────────┐

│ OP (8) │ X (8) │ Y (8) │ Z (8) │

└────────┴────────┴────────┴────────┘

Example: ADD $1,$2,$3

OP=0x20, X=1, Y=2, Z=3

Core execution loop:

while (!halted) {

instruction = memory[PC];

OP = (instruction >> 24) & 0xFF;

X = (instruction >> 16) & 0xFF;

Y = (instruction >> 8) & 0xFF;

Z = instruction & 0xFF;

switch (OP) {

case 0x20: // ADD

reg[X] = reg[Y] + reg[Z];

break;

case 0xF8: // POP (return)

// Complex stack unwinding

break;

// ... 254 more cases

}

PC += 4;

}

Think about:

- How do you handle overflow in arithmetic operations?

- What happens on TRAP instructions (system calls)?

- How do you implement the stack with rO and rS?

- How do you handle interrupts and trips?

Learning milestones:

- Basic arithmetic instructions work → You understand ALU operations

- Memory loads/stores work → You understand addressing modes

- Branches and jumps work → You understand control flow

- TRAP instructions work → You understand I/O and system calls

- Can run TAOCP example programs → You’re ready for the algorithms!

Definition of Done

- Runs the sample MMIX program and produces correct output

- Opcode test suite covers arithmetic, load/store, branch, and TRAP

- Trace output matches a golden trace for a known program

- Memory and register invariants validated after each step

Project 2: Mathematical Toolkit (TAOCP’s Foundations)

- File: LEARN_TAOCP_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Python, Haskell

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Mathematics / Number Theory / Combinatorics

- Software or Tool: Building: Math Library

- Main Book: “The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 1” Chapter 1 - Knuth

What you’ll build: A comprehensive mathematical library implementing the foundations from TAOCP Chapter 1—including arbitrary precision arithmetic, binomial coefficients, Fibonacci numbers, harmonic numbers, and generating functions.

Why it teaches TAOCP: Chapter 1 is the mathematical foundation for everything that follows. Knuth uses these tools constantly—binomial coefficients for counting, generating functions for solving recurrences, and harmonic numbers for algorithm analysis.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Implementing binomial coefficients without overflow → maps to Pascal’s triangle

- Computing Fibonacci numbers efficiently → maps to matrix exponentiation

- Harmonic number approximations → maps to asymptotic analysis

- Polynomial arithmetic → maps to generating functions

Key Concepts:

- Mathematical Induction: TAOCP Vol 1, Section 1.2.1

- Binomial Coefficients: TAOCP Vol 1, Section 1.2.6

- Fibonacci Numbers: TAOCP Vol 1, Section 1.2.8

- Generating Functions: TAOCP Vol 1, Section 1.2.9

- Asymptotic Notation: TAOCP Vol 1, Section 1.2.11

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 1-2 weeks Prerequisites:

- Basic algebra and calculus

- C programming with arbitrary precision (or implement it)

- Interest in mathematics

Real world outcome:

$ ./math_toolkit

math> binomial 100 50

100891344545564193334812497256

math> fibonacci 1000

43466557686937456435688527675040625802564660517371780402481729089536555417949051890403879840079255169295922593080322634775209689623239873322471161642996440906533187938298969649928516003704476137795166849228875

math> harmonic 1000000

14.392726722865723631415730

math> gcd 1234567890 987654321

9

math> solve_recurrence "F(n) = F(n-1) + F(n-2), F(0)=0, F(1)=1"

Closed form: F(n) = (phi^n - psi^n) / sqrt(5)

Where phi = (1+sqrt(5))/2, psi = (1-sqrt(5))/2

math> prime_factorize 1234567890

2 × 3² × 5 × 3607 × 3803

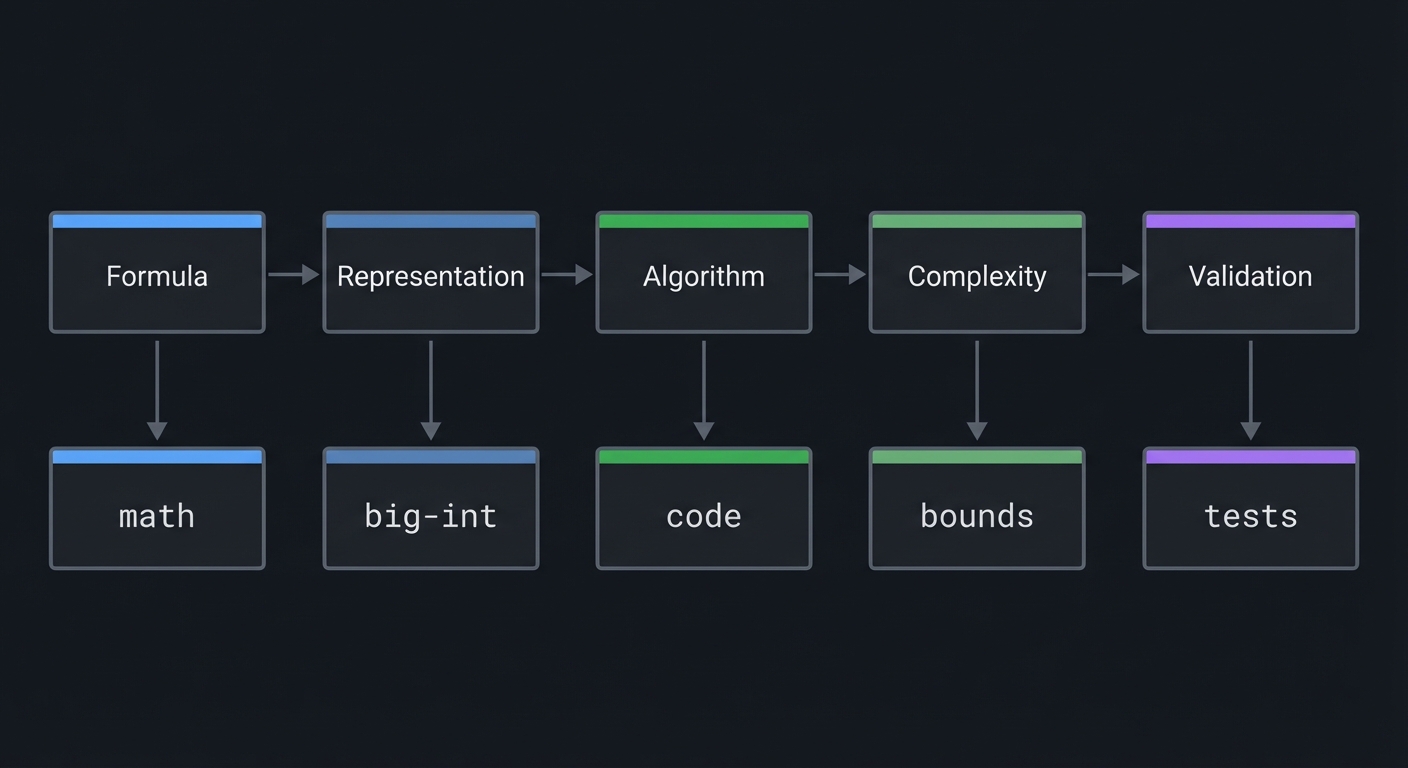

Visual Model

Formula -> Representation -> Algorithm -> Complexity -> Validation

| | | | |

math big-int code bounds tests

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do you compute and analyze mathematical quantities exactly, without losing correctness to overflow or approximation?”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Integer representations and overflow (CS:APP Ch. 2)

- Induction and recurrence solving (Concrete Mathematics Ch. 1-3)

- Modular arithmetic and GCD

- Generating functions and series manipulation

Questions to Guide Your Design

- What base will you store digits in, and how does it impact speed?

- When do you use exact formulas vs approximations?

- How will you validate results for very large inputs?

- Which functions need memoization to stay fast?

Thinking Exercise

Compute by hand:

- C(6,3)

- H(5) = 1 + 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/4 + 1/5

- gcd(252, 198)

Then verify your toolkit matches each result.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- How do you compute Fibonacci in O(log n)?

- Why does naive binomial overflow, and how do you avoid it?

- How do you implement gcd efficiently?

- What is a generating function and why is it useful?

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start With BigInt Add/Sub Everything else relies on correct carry propagation.

Hint 2: Implement gcd and modular exponent These unlock many later algorithms and tests.

Hint 3: Add Binomial and Fibonacci Use multiplicative formulas and fast doubling/matrix methods.

Hint 4: Validate With Known Sequences Compare with published values (Catalan numbers, Fibonacci, primes).

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Induction and recurrences | Concrete Mathematics | Ch. 1-3 |

| Integer representation | CS:APP | Ch. 2 |

| Algorithmic math | Math for Programmers | Ch. 2-4 |

| Fundamental algorithms | TAOCP Vol 1 | Ch. 1 |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem: “Binomial results are incorrect for large n”

- Why: Intermediate multiplication overflows before division.

- Fix: Multiply/divide incrementally and reduce by gcd.

- Quick test: Compare C(100,50) with a known value.

Problem: “Harmonic approximation is off”

- Why: Using too few terms in the asymptotic expansion.

- Fix: Add more terms or use direct summation for smaller n.

- Quick test: Compare H(10^6) to a high-precision reference.

Implementation Hints:

Efficient binomial coefficient:

// C(n,k) = n! / (k! * (n-k)!)

// But compute incrementally to avoid overflow

uint64_t binomial(int n, int k) {

if (k > n - k) k = n - k; // C(n,k) = C(n, n-k)

uint64_t result = 1;

for (int i = 0; i < k; i++) {

result = result * (n - i) / (i + 1); // Order matters!

}

return result;

}

Fibonacci via matrix exponentiation:

[F(n+1)] [1 1]^n [1]

[F(n) ] = [1 0] × [0]

Matrix power in O(log n) using repeated squaring!

Harmonic numbers with Euler-Maclaurin:

H(n) ≈ ln(n) + γ + 1/(2n) - 1/(12n²) + 1/(120n⁴) - ...

Where γ ≈ 0.5772156649... (Euler-Mascheroni constant)

Think about:

- How do you compute binomial(1000, 500) without overflow?

- What’s the fastest way to compute Fibonacci(1000000)?

- How do you represent generating functions as data structures?

- How precise should harmonic number approximations be?

Learning milestones:

- Binomials compute correctly → You understand Pascal’s triangle

- Large Fibonacci numbers work → You understand matrix exponentiation

- Harmonic approximations are accurate → You understand asymptotics

- GCD is efficient → You understand Euclid’s algorithm

Definition of Done

- Big-int add/sub/mul/div pass randomized tests

- Binomial/Fibonacci/Harmonic outputs match known values

- Recurrence solver matches closed forms for sample inputs

- Benchmarks show asymptotically faster methods win at scale

Project 3: Dynamic Data Structures Library

- File: LEARN_TAOCP_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, C++

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 2. The “Micro-SaaS / Pro Tool”

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Data Structures / Memory Management

- Software or Tool: Building: Data Structures Library

- Main Book: “The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 1” Chapter 2 - Knuth

What you’ll build: A complete library of fundamental data structures as described in TAOCP Chapter 2—stacks, queues, deques, linked lists (all variants), and general trees.

Why it teaches TAOCP: Chapter 2 covers information structures—how data lives in memory. Knuth’s treatment is deeper than most textbooks, covering circular lists, doubly-linked lists, symmetric lists, and orthogonal lists. You’ll understand the design choices at the deepest level.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Implementing all linked list variants → maps to pointer manipulation

- Circular doubly-linked lists → maps to symmetric structures

- Tree traversals and threading → maps to recursive structures

- Memory allocation and garbage collection → maps to storage management

Key Concepts:

- Stacks and Queues: TAOCP Vol 1, Section 2.2.1

- Linked Lists: TAOCP Vol 1, Section 2.2.3-2.2.5

- Trees: TAOCP Vol 1, Sections 2.3.1-2.3.3

- Garbage Collection: TAOCP Vol 1, Section 2.3.5

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 2 weeks Prerequisites:

- C programming (pointers, malloc/free)

- Basic data structure concepts

- Project 1 helpful but not required

Real world outcome:

$ ./test_structures

Testing circular doubly-linked list:

Insert: A -> B -> C -> D -> (back to A)

Forward traverse: A B C D A B C ...

Backward traverse: D C B A D C B ...

Delete C: A -> B -> D -> (back to A)

✓ All operations O(1)

Testing threaded binary tree:

Inorder: A B C D E F G

Inorder successor of D: E (via thread, O(1))

Inorder predecessor of D: C (via thread, O(1))

✓ No stack needed for traversal!

Testing garbage collection:

Allocated 10000 nodes

Created reference cycles

Running mark-sweep GC...

Freed 7500 unreachable nodes

✓ Memory reclaimed correctly

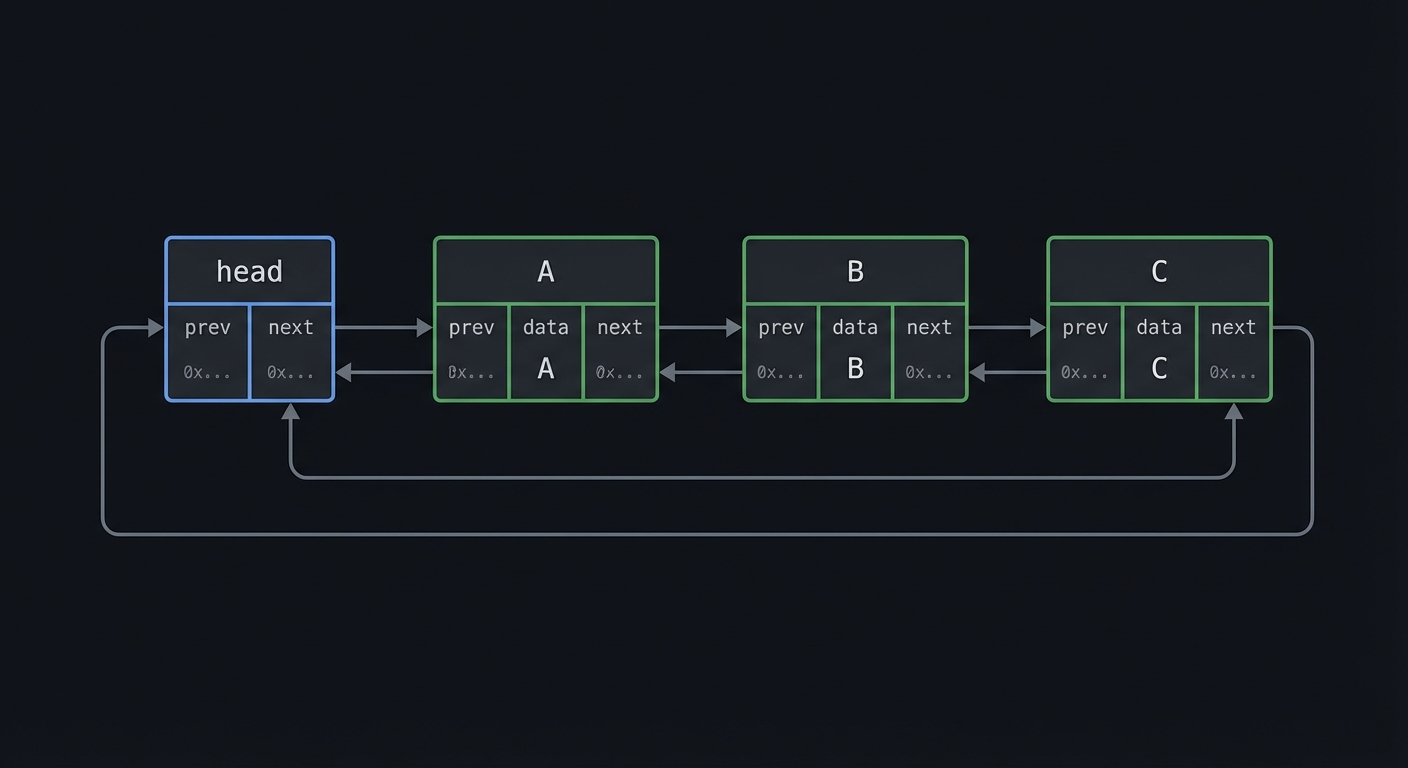

Visual Model

[head] <-> [A] <-> [B] <-> [C] <-> [head]

^ |

+--------------------------------------+

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do you keep pointer-based structures correct under every insert, delete, and traversal?”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Pointer invariants and ownership rules

- Sentinel nodes and circular list advantages

- Stack/queue/deque semantics

- Heap allocation strategies and GC basics

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Will you use sentinels to simplify empty-list edge cases?

- How will you enforce invariants after each mutation?

- How will you test for memory leaks and dangling pointers?

- Which operations must be O(1), and which can be O(n)?

Thinking Exercise

Draw a circular doubly-linked list with nodes A, B, C. Delete B and update the four pointer assignments by hand.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- Why use a circular list instead of NULL-terminated?

- How do you implement a queue with O(1) enqueue/dequeue?

- What are common linked-list bugs in C?

- How would you detect and fix a memory leak?

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start With Stack and Queue These are the simplest structures and build confidence.

Hint 2: Add a Sentinel Head It removes special cases and simplifies deletion.

Hint 3: Implement Threaded Trees Separately Keep the list library small and reliable.

Hint 4: Add GC as an Independent Module Test GC with a synthetic graph of nodes and cycles.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Lists and trees | TAOCP Vol 1 | Ch. 2 |

| Practical structures | Algorithms in C | Parts 1-2 |

| Pointer discipline | Understanding and Using C Pointers | Ch. 3-6 |

| API design | C Interfaces and Implementations | Ch. 4-6 |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem: “List traversal loops forever”

- Why: Circular list links not updated correctly after delete.

- Fix: Validate that each node’s next/prev are consistent.

- Quick test: Traverse forward/backward for 2*n steps and ensure repetition.

Problem: “Random crashes on delete”

- Why: Use-after-free or double-free.

- Fix: Null out pointers after free and track ownership.

- Quick test: Run with address sanitizer and delete every node twice in tests.

Implementation Hints:

Circular doubly-linked list node:

typedef struct Node {

void* data;

struct Node* prev;

struct Node* next;

} Node;

// Empty list: head->prev = head->next = head (self-loop)

// Insert after p: new->next = p->next; new->prev = p;

// p->next->prev = new; p->next = new;

// Delete p: p->prev->next = p->next; p->next->prev = p->prev;

Threaded binary tree:

typedef struct TNode {

void* data;

struct TNode* left;

struct TNode* right;

bool left_is_thread; // true if left points to predecessor

bool right_is_thread; // true if right points to successor

} TNode;

// Inorder successor without stack:

TNode* successor(TNode* p) {

if (p->right_is_thread) return p->right;

p = p->right;

while (!p->left_is_thread) p = p->left;

return p;

}

Mark-sweep garbage collection:

mark_phase(root):

if root is marked: return

mark root

for each pointer p in root:

mark_phase(*p)

sweep_phase():

for each object in heap:

if not marked:

free(object)

else:

unmark object

Think about:

- What’s the advantage of circular lists over NULL-terminated?

- Why use threading in trees?

- How does reference counting differ from mark-sweep?

- What are the trade-offs of different memory allocation strategies?

Learning milestones:

- All list variants work → You understand linked structures

- Threaded traversal is stackless → You understand threading

- GC reclaims memory correctly → You understand reachability

- Performance matches expected complexity → You can analyze structures

Definition of Done

- All list/stack/queue operations pass edge-case tests

- Threaded tree traversal works without recursion

- GC reclaims cycles and reports accurate counts

- No leaks or use-after-free under sanitizers

Project 4: Tree Algorithms and Traversals

- File: LEARN_TAOCP_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Go

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Trees / Recursion / Combinatorics

- Software or Tool: Building: Tree Library

- Main Book: “The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 1” Section 2.3 - Knuth

What you’ll build: A comprehensive tree library including binary trees, general trees, forests, and the algorithms from TAOCP—including the correspondence between forests and binary trees, tree enumeration, and path length analysis.

Why it teaches TAOCP: Knuth’s treatment of trees is extraordinarily deep, covering not just operations but the combinatorics of trees—how many trees exist with n nodes, the average path length, and the natural correspondence between forests and binary trees.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Forest-to-binary-tree conversion → maps to natural correspondence

- Counting trees (Catalan numbers) → maps to combinatorics

- Computing path lengths → maps to algorithm analysis

- Huffman encoding → maps to optimal trees

Key Concepts:

- Tree Traversals: TAOCP Vol 1, Section 2.3.1 (Algorithm T, S, etc.)

- Binary Trees: TAOCP Vol 1, Section 2.3.1

- Tree Enumeration: TAOCP Vol 1, Section 2.3.4.4

- Huffman’s Algorithm: TAOCP Vol 1, Section 2.3.4.5

- Path Length: TAOCP Vol 1, Section 2.3.4.5

Difficulty: Advanced Time estimate: 2 weeks Prerequisites:

- Project 3 completed

- Understanding of recursion

- Basic combinatorics

Real world outcome:

$ ./tree_toolkit

# Convert forest to binary tree

tree> forest_to_binary "((A B) (C (D E)) F)"

Binary tree:

A

/

B

\

C

/

D

\

E

\

F

# Count binary trees with n nodes (Catalan numbers)

tree> count_trees 10

16796 distinct binary trees with 10 nodes

(This is C(10) = C(20,10)/(10+1) = 16796)

# Compute internal/external path length

tree> path_lengths "example.tree"

Internal path length: 45

External path length: 75

Relation: E = I + 2n ✓

# Build Huffman tree

tree> huffman "AAAAABBBBCCCDDE"

Symbol frequencies: A:5, B:4, C:3, D:2, E:1

Huffman codes:

A: 0 (1 bit)

B: 10 (2 bits)

C: 110 (3 bits)

D: 1110 (4 bits)

E: 1111 (4 bits)

Average bits per symbol: 2.07

Entropy: 2.03 bits (Huffman is near-optimal!)

Visual Model

Forest: Binary Tree:

A A

/|\ /

B C D B

| E C

D

/

E

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do different tree representations change traversal, counting, and optimal coding?”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Inorder/preorder/postorder traversal invariants

- Tree enumeration and Catalan numbers

- Path length definitions (internal vs external)

- Huffman coding and optimal prefix trees

Questions to Guide Your Design

- How will you represent general trees and forests in memory?

- Can you compute path lengths without recursion?

- How will you verify Catalan counts for small n?

- What data structure will you use for Huffman priority queue?

Thinking Exercise

Given symbols A:5, B:4, C:3, D:2, E:1, build the Huffman tree and compute average bits per symbol.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- Why does E = I + 2n for binary trees?

- How does forest-to-binary-tree correspondence work?

- What makes Huffman coding optimal?

- How do you compute the number of binary trees with n nodes?

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Implement Basic Traversals Start with recursive traversals and validate orderings.

Hint 2: Add the Forest Conversion Use first-child/next-sibling mapping.

Hint 3: Implement Catalan via DP Verify counts for n=0..10.

Hint 4: Add Huffman With a Min-Heap Each combine step removes two smallest nodes.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Tree algorithms | TAOCP Vol 1 | Ch. 2.3 |

| Practical trees | Algorithms in C | Part 5 |

| Recursion and trees | The Recursive Book of Recursion | Ch. 7-8 |

| Encoding | Algorithms, 4th Edition | Ch. 5 |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem: “Traversal output is wrong”

- Why: Left/right children swapped or incorrect base cases.

- Fix: Test on a tiny tree with known traversal orders.

- Quick test: For tree (A (B C)), inorder should be B A C.

Problem: “Huffman codes are not prefix-free”

- Why: Tree construction step not preserving left/right leaf structure.

- Fix: Verify that only leaves get codes and internal nodes do not.

- Quick test: Check that no code is a prefix of any other.

Implementation Hints:

Forest to binary tree (natural correspondence):

For each node in forest:

- First child becomes LEFT child in binary tree

- Next sibling becomes RIGHT child in binary tree

Forest: Binary tree:

A A

/|\ /

B C D B

| \

E C

\

D

/

E

Catalan numbers (count of binary trees):

C(n) = (2n)! / ((n+1)! * n!)

C(n) = C(n-1) * 2(2n-1) / (n+1)

C(0)=1, C(1)=1, C(2)=2, C(3)=5, C(4)=14, C(5)=42, ...

Internal/External path length:

I = sum of depths of internal nodes

E = sum of depths of external nodes (null pointers)

Theorem: E = I + 2n (where n = number of internal nodes)

This is fundamental to analyzing search trees!

Huffman’s algorithm:

1. Create leaf node for each symbol with its frequency

2. While more than one node in queue:

a. Remove two nodes with lowest frequency

b. Create new internal node with these as children

c. Frequency = sum of children's frequencies

d. Insert new node back into queue

3. Remaining node is root of Huffman tree

Learning milestones:

- Traversals work correctly → You understand tree navigation

- Forest conversion is reversible → You understand the correspondence

- Catalan numbers match tree counts → You understand enumeration

- Huffman achieves near-entropy → You understand optimal coding

Definition of Done

- Forest-to-binary conversion is reversible on test trees

- Catalan counts match for n=0..10

- Huffman codes are prefix-free and near-entropy

- Path length relation E = I + 2n verified

VOLUME 2: SEMINUMERICAL ALGORITHMS

Project 5: Random Number Generator Suite

- File: LEARN_TAOCP_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Go, Python

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 3. The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Random Numbers / Statistics / Number Theory

- Software or Tool: Building: RNG Library

- Main Book: “The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 2” Chapter 3 - Knuth

What you’ll build: A complete random number generation library with linear congruential generators, parameter selection, period analysis, and statistical testing—exactly as described in TAOCP Chapter 3.

Why it teaches TAOCP: Chapter 3 is the definitive treatment of random numbers. Knuth explains not just how to generate them, but how to test if they’re “random enough.” You’ll understand why rand() in most C libraries is terrible, and how to do better.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Implementing LCG with optimal parameters → maps to number theory

- Computing the period of an LCG → maps to group theory

- Statistical tests (chi-square, KS) → maps to hypothesis testing

- The spectral test → maps to lattice theory

Key Concepts:

- Linear Congruential Method: TAOCP Vol 2, Section 3.2.1

- Choice of Parameters: TAOCP Vol 2, Section 3.2.1.2-3

- Statistical Tests: TAOCP Vol 2, Section 3.3.1-3.3.2

- Spectral Test: TAOCP Vol 2, Section 3.3.4

- Other Generators: TAOCP Vol 2, Section 3.2.2

Resources for key challenges:

- Linear Congruential Generator - Wikipedia - Quick reference

- Spectral Test Explanation - Columbia lecture notes

Difficulty: Advanced Time estimate: 2-3 weeks Prerequisites:

- Basic number theory (modular arithmetic, GCD)

- Statistics fundamentals

- Project 2 (mathematical toolkit) helpful

Real world outcome:

$ ./rng_suite

# Create LCG with specific parameters

rng> lcg_create m=2147483647 a=48271 c=0

LCG created: X(n+1) = 48271 * X(n) mod 2147483647

# Analyze period

rng> analyze_period

Full period achieved: 2147483646

(m-1 because c=0, so 0 is not in sequence)

# Generate and test

rng> generate 1000000

Generated 1,000,000 random numbers

rng> test_uniformity

Chi-square test (100 bins):

χ² = 94.7, df = 99

p-value = 0.612

Result: PASS (uniformly distributed)

rng> test_serial

Serial correlation test:

r = 0.00023

Result: PASS (independent)

rng> spectral_test

Spectral test results:

Dimension 2: ν₂ = 0.998 (excellent)

Dimension 3: ν₃ = 0.891 (good)

Dimension 4: ν₄ = 0.756 (acceptable)

Dimension 5: ν₅ = 0.623 (marginal)

# Compare with bad generator

rng> lcg_create m=256 a=5 c=1

rng> spectral_test

Dimension 2: ν₂ = 0.312 (TERRIBLE!)

Points lie on only 8 parallel lines!

Visual Model

X(n+1) = (a * X(n) + c) mod m

| | | |

state multiplier inc modulus

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How can a deterministic generator produce sequences that behave like randomness, and how do you prove it?”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Modular arithmetic and periods

- Parameter selection for full period

- Statistical tests (chi-square, serial correlation)

- Lattice structure and the spectral test

Questions to Guide Your Design

- How will you handle overflow in a * X(n)?

- Which tests will you implement first to detect obvious bias?

- How large a sample do you need for stable p-values?

- How will you compare two generators fairly?

Thinking Exercise

Pick m=16, a=5, c=1, seed=1. Generate the first 10 outputs and plot the pairs (x_i, x_{i+1}). What pattern do you see?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- Why are many standard rand() implementations poor?

- What does it mean for an LCG to have full period?

- How do you interpret a chi-square p-value?

- What does the spectral test reveal?

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Implement LCG Core Validate with a small modulus and compare with hand computation.

Hint 2: Add Simple Uniformity Tests Histogram counts and chi-square should be your first checks.

Hint 3: Add Serial Correlation Compute correlation between successive values.

Hint 4: Implement Spectral Test Start with 2D and 3D projections and measure line spacing.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Random numbers | TAOCP Vol 2 | Ch. 3 |

| Modular math | Concrete Mathematics | Ch. 1-2 |

| Statistical tests | Math for Programmers | Ch. 10 |

| Empirical analysis | Algorithms, 4th Edition | Ch. 1.4 |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem: “Sequence repeats too early”

- Why: Parameters do not meet full-period criteria.

- Fix: Verify gcd(c, m)=1 and factors of m divide (a-1).

- Quick test: Track first repeat of seed and compute period.

Problem: “Chi-square always fails”

- Why: Using too few samples or incorrect expected counts.

- Fix: Increase n and ensure each bin has expected count >= 5.

- Quick test: Test a known good generator to validate your test code.

Implementation Hints:

Linear Congruential Generator:

// X(n+1) = (a * X(n) + c) mod m

typedef struct {

uint64_t x; // Current state

uint64_t a; // Multiplier

uint64_t c; // Increment

uint64_t m; // Modulus

} LCG;

uint64_t lcg_next(LCG* rng) {

rng->x = (rng->a * rng->x + rng->c) % rng->m;

return rng->x;

}

Knuth’s recommended parameters:

m = 2^64 (use native overflow)

a = 6364136223846793005

c = 1442695040888963407

(These pass the spectral test well)

Period analysis:

For full period (period = m), need:

1. c and m are coprime: gcd(c, m) = 1

2. a-1 is divisible by all prime factors of m

3. If m is divisible by 4, then a-1 is divisible by 4

If c = 0 (multiplicative generator):

Period is at most m-1

Need m prime and a primitive root mod m

Chi-square test:

1. Divide [0,1) into k equal bins

2. Generate n random numbers

3. Count observations in each bin: O[i]

4. Expected count: E = n/k

5. χ² = Σ (O[i] - E)² / E

6. Compare with chi-square distribution (k-1 df)

Learning milestones:

- LCG generates correct sequence → You understand the algorithm

- Period analysis is correct → You understand number theory

- Chi-square test works → You understand statistical testing

- Spectral test reveals quality → You understand lattice structure

Definition of Done

- LCG period matches theoretical expectations

- Uniformity and serial tests pass for good parameters

- Spectral test differentiates good vs bad generators

- Results reproducible with fixed seeds

Project 6: Arbitrary-Precision Arithmetic

- File: LEARN_TAOCP_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Assembly

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 3. The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 4: Expert

- Knowledge Area: Arithmetic / Number Theory / Algorithms

- Software or Tool: Building: BigNum Library

- Main Book: “The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 2” Chapter 4 - Knuth

What you’ll build: A complete arbitrary-precision arithmetic library (like GMP but simpler) implementing addition, subtraction, multiplication (including Karatsuba), division, GCD, and modular exponentiation.

Why it teaches TAOCP: Chapter 4 is the bible of computer arithmetic. You’ll learn how computers really do math—not just integer addition, but the algorithms behind calculators, cryptography, and scientific computing.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Multiple-precision addition with carry → maps to basic arithmetic

- Karatsuba multiplication → maps to divide and conquer

- Long division algorithm → maps to classical algorithms

- Modular exponentiation → maps to cryptographic foundations

Key Concepts:

- Classical Algorithms: TAOCP Vol 2, Section 4.3.1

- Karatsuba Multiplication: TAOCP Vol 2, Section 4.3.3

- Division: TAOCP Vol 2, Section 4.3.1 (Algorithm D)

- GCD: TAOCP Vol 2, Section 4.5.2

- Modular Arithmetic: TAOCP Vol 2, Section 4.3.2

Difficulty: Expert Time estimate: 3-4 weeks Prerequisites:

- Solid C programming

- Understanding of binary representation

- Basic number theory

Real world outcome:

$ ./bignum

bignum> set A = 12345678901234567890123456789

bignum> set B = 98765432109876543210987654321

bignum> A + B

111111111011111111101111111110

bignum> A * B

1219326311370217952261850327338667891975126429917755911761289

bignum> factorial 1000

Factorial(1000) = 402387260077093773543702433923003985...

(2568 digits, computed in 0.02 seconds)

bignum> 2^10000

2^10000 = 1995063116880758...

(3011 digits)

bignum> mod_exp 2 1000000 1000000007

2^1000000 mod 1000000007 = 688423210

(Computed in 0.001 seconds using repeated squaring)

bignum> is_prime 170141183460469231731687303715884105727

PRIME (2^127 - 1, a Mersenne prime)

Miller-Rabin test: 64 rounds passed

Visual Model

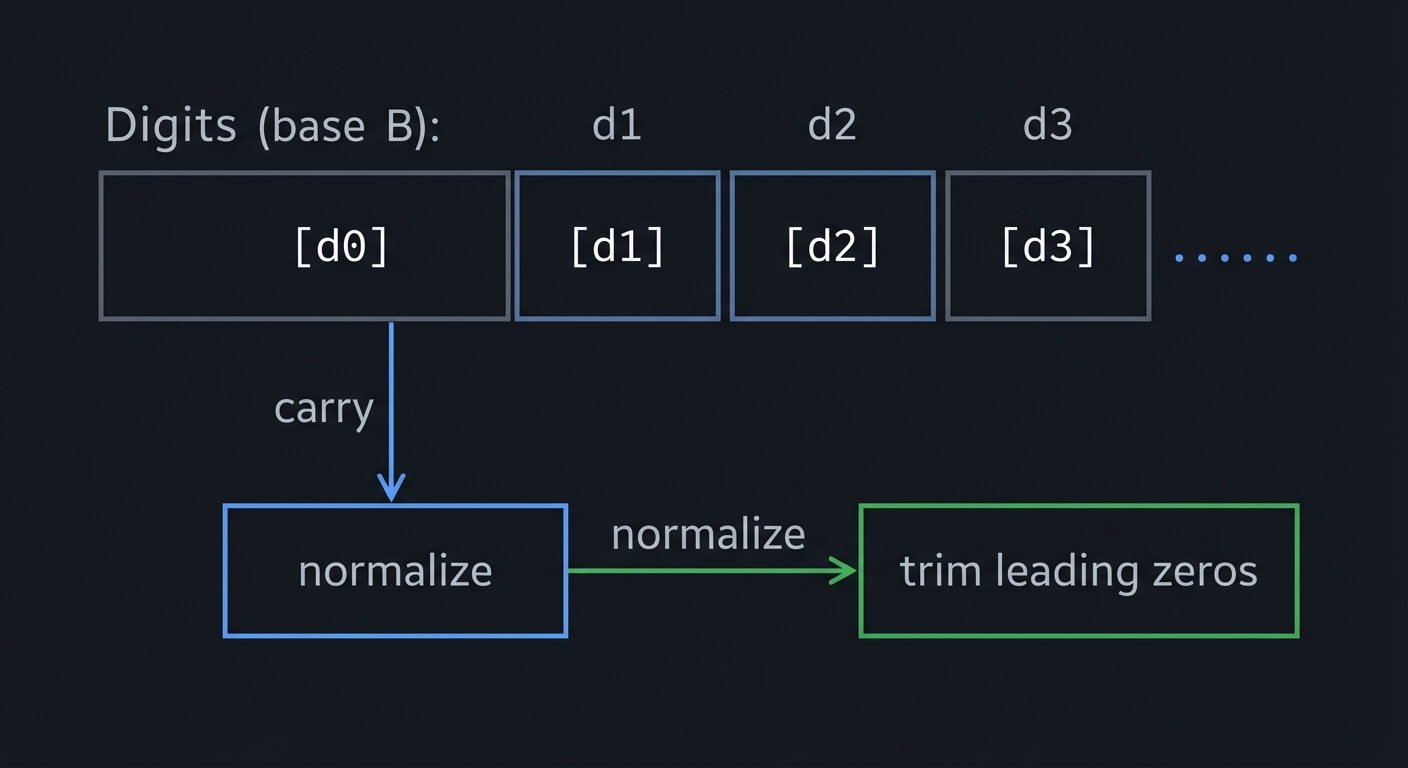

Digits (base B): [d0][d1][d2][d3]...

+ carry -> normalize -> trim leading zeros

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do you perform exact arithmetic beyond machine word size while staying fast enough for real workloads?”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Base representation and carry propagation

- Normalization and sign handling

- Long multiplication vs Karatsuba thresholds

- Division and modular exponentiation

Questions to Guide Your Design

- What base and digit size will you use (2^32, 2^64, 10^9)?

- When do you switch from classical multiply to Karatsuba?

- How will you represent negative values and zero?

- Which operations require normalization after every step?

Thinking Exercise

Multiply 1234 x 5678 using base 100. Write the digits of each number, perform the grade-school multiply, and carry-normalize the result.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- Why is Karatsuba faster than classical multiplication?

- How do you implement modular exponentiation efficiently?

- What is the complexity of long division?

- How do you avoid timing leaks in modular arithmetic?

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Get Add/Sub Correct First If carry/borrow is wrong, everything else will fail.

Hint 2: Implement Multiply Next Classical O(n^2) multiplication is easiest to validate.

Hint 3: Add Division Using Algorithm D Start with positive integers only, then add sign support.

Hint 4: Add ModExp and GCD These let you build RSA and primality tests.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple precision | TAOCP Vol 2 | Ch. 4 |

| Integer representation | CS:APP | Ch. 2 |

| Divide and conquer | Algorithms, 4th Edition | Ch. 2.3 |

| Low-level arithmetic | Write Great Code, Vol. 2 | Ch. 7 |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem: “Results contain random extra digits”

- Why: Leading zeros not trimmed or size not updated.

- Fix: Normalize after every operation and strip leading zeros.

- Quick test: Add a number to itself and compare sizes.

Problem: “Negative subtraction gives wrong sign”

- Why: Comparing magnitudes incorrectly before subtracting.

- Fix: Compare absolute values and swap operands when needed.

- Quick test: Verify (a - b) + b = a for random a,b.

Implementation Hints:

BigNum representation:

typedef struct {

uint32_t* digits; // Array of "digits" (base 2^32)

size_t size; // Number of digits

int sign; // +1 or -1

} BigNum;

// Example: 12345678901234567890

// In base 2^32 ≈ 4.29 billion

// = 2 * (2^32)^1 + 3755744766 * (2^32)^0

Classical addition:

void bignum_add(BigNum* result, BigNum* a, BigNum* b) {

uint64_t carry = 0;

for (size_t i = 0; i < max(a->size, b->size); i++) {

uint64_t sum = carry;

if (i < a->size) sum += a->digits[i];

if (i < b->size) sum += b->digits[i];

result->digits[i] = (uint32_t)sum;

carry = sum >> 32;

}

if (carry) result->digits[result->size++] = carry;

}

Karatsuba multiplication:

To multiply x and y (n digits each):

1. Split: x = x1 * B + x0, y = y1 * B + y0 (B = base^(n/2))

2. Compute:

z0 = x0 * y0

z2 = x1 * y1

z1 = (x0 + x1) * (y0 + y1) - z0 - z2

3. Result: z2 * B² + z1 * B + z0

Complexity: O(n^1.585) instead of O(n²)

Algorithm D (division):

Knuth's Algorithm D is the classical long division algorithm:

1. Normalize divisor (shift so leading digit >= base/2)

2. For each digit of quotient:

a. Estimate quotient digit

b. Multiply back and subtract

c. Correct if estimate was wrong

Learning milestones:

- Addition/subtraction work → You understand carry propagation

- Karatsuba is faster for large numbers → You understand divide-and-conquer

- Division works correctly → You’ve mastered Algorithm D

- RSA encryption works → You can do cryptography!

Definition of Done

- All arithmetic operations correct against a reference

- Karatsuba beats classical beyond a measured threshold

- Modexp and GCD work on large inputs

- Toy RSA encrypt/decrypt round-trip succeeds

Project 7: Floating-Point Emulator

- File: LEARN_TAOCP_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, C++

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 2. The “Micro-SaaS / Pro Tool”

- Difficulty: Level 4: Expert

- Knowledge Area: Floating-Point / IEEE 754 / Numerical Analysis

- Software or Tool: Building: Soft Float Library

- Main Book: “The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 2” Section 4.2 - Knuth

What you’ll build: A software floating-point library that implements IEEE 754 arithmetic from scratch—addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and rounding modes.

Why it teaches TAOCP: Section 4.2 covers floating-point arithmetic in detail. Understanding how floats work at the bit level is crucial for numerical programming. You’ll finally understand why 0.1 + 0.2 ≠ 0.3.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Encoding/decoding IEEE 754 format → maps to representation

- Alignment and normalization → maps to floating-point addition

- Rounding modes → maps to precision control

- Special values (NaN, Inf) → maps to exception handling

Key Concepts:

- Floating-Point Representation: TAOCP Vol 2, Section 4.2.1

- Floating-Point Addition: TAOCP Vol 2, Section 4.2.1

- Floating-Point Multiplication: TAOCP Vol 2, Section 4.2.1

- Accuracy: TAOCP Vol 2, Section 4.2.2

Difficulty: Expert Time estimate: 2 weeks Prerequisites:

- Project 6 (arbitrary precision) helpful

- Understanding of binary fractions

- Knowledge of IEEE 754 format

Real world outcome:

$ ./softfloat

# Decode IEEE 754

float> decode 0x40490FDB

Sign: 0 (positive)

Exponent: 10000000 (bias 127, actual = 1)

Mantissa: 10010010000111111011011

Value: 3.14159265... (pi approximation)

# Why 0.1 + 0.2 != 0.3

float> exact 0.1

0.1 decimal = 0.00011001100110011001100110011001... binary (repeating!)

Stored as: 0.100000001490116119384765625

float> 0.1 + 0.2

= 0.30000000000000004 (not exactly 0.3!)

# Rounding modes

float> mode round_nearest

float> 1.0 / 3.0

= 0.3333333432674408 (rounded to nearest)

float> mode round_toward_zero

float> 1.0 / 3.0

= 0.3333333134651184 (truncated)

# Special values

float> 1.0 / 0.0

= +Infinity

float> 0.0 / 0.0

= NaN (Not a Number)

Visual Model

[S][Exponent][Mantissa]

1 8 bits 23 bits

value = (-1)^S * 1.M * 2^(E-bias)

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do floating-point numbers represent real values, and where do the errors come from?”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Exponent bias and hidden leading 1

- Alignment, normalization, and rounding

- Denormals, infinities, and NaNs

- Guard, round, and sticky bits

Questions to Guide Your Design

- How will you handle rounding modes consistently?

- What precision do you keep during intermediate steps?

- How will you encode and decode NaN payloads?

- What happens on overflow or underflow?

Thinking Exercise

Convert 0.1 to binary and find the nearest representable 32-bit float. Compare it to decimal 0.1 and compute the error.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- Why does 0.1 + 0.2 not equal 0.3 in binary floats?

- What is a denormal number and why does it exist?

- How do rounding modes affect reproducibility?

- What is NaN, and how is it propagated?

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start With Decode/Encode Being able to parse bits correctly is the foundation.

Hint 2: Implement Addition With Alignment Handle exponent shifts before mantissa add/sub.

Hint 3: Add Rounding Use guard/round/sticky bits to implement IEEE rules.

Hint 4: Add Special Cases Handle NaN, Inf, and denormals last.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Floating-point | TAOCP Vol 2 | Ch. 4.2 |

| Number representation | CS:APP | Ch. 2 |

| Computer arithmetic | Computer Organization and Design | Ch. 3 |

| Low-level arithmetic | Write Great Code, Vol. 2 | Ch. 7 |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem: “Rounding off by 1 ULP”

- Why: Missing sticky bit or wrong tie-breaking rule.

- Fix: Track guard/round/sticky and implement round-to-even.

- Quick test: Compare against hardware results for edge cases.

Problem: “NaNs collapse to zero”

- Why: Treating NaN as a normal value during normalization.

- Fix: Short-circuit when exponent is all 1s and mantissa != 0.

- Quick test: NaN op NaN should yield NaN, not 0.

Implementation Hints:

IEEE 754 single precision (32-bit):

Bit layout: [S][EEEEEEEE][MMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMM]

[1][ 8 bits ][ 23 bits ]

S = sign (0 = positive, 1 = negative)

E = biased exponent (actual = E - 127)

M = mantissa (implicit leading 1)

Value = (-1)^S × 1.M × 2^(E-127)

Special cases:

E=0, M=0: Zero (±0)

E=0, M≠0: Denormalized (0.M × 2^-126)

E=255, M=0: Infinity (±∞)

E=255, M≠0: NaN

Floating-point addition:

add(a, b):

1. Align exponents: shift smaller mantissa right

2. Add mantissas (with implicit 1)

3. Normalize: if overflow, shift right, increment exponent

if leading zeros, shift left, decrement exponent

4. Round mantissa to 23 bits

5. Handle overflow/underflow

Rounding modes:

Round to nearest (even): Default, unbiased

Round toward zero: Truncate

Round toward +∞: Always round up

Round toward -∞: Always round down

Learning milestones:

- Encode/decode works → You understand representation

- Addition handles alignment → You understand the algorithm

- 0.1 + 0.2 behaves correctly → You understand precision limits

- All rounding modes work → You understand IEEE 754 fully

Definition of Done

- Encode/decode matches IEEE 754 for known values

- Arithmetic matches hardware for a test corpus

- All rounding modes produce expected results

- NaN/Inf/denormal cases behave correctly

VOLUME 3: SORTING AND SEARCHING

Project 8: Complete Sorting Algorithm Collection

- File: LEARN_TAOCP_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Go

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 2. The “Micro-SaaS / Pro Tool”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Sorting / Algorithm Analysis

- Software or Tool: Building: Sort Library

- Main Book: “The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 3” Chapter 5 - Knuth

What you’ll build: Every major sorting algorithm from TAOCP Chapter 5—insertion sort, shellsort, heapsort, quicksort, merge sort, radix sort—with instrumentation to count comparisons and moves.

Why it teaches TAOCP: Chapter 5 is the definitive reference on sorting. Knuth analyzes each algorithm mathematically, proving their complexity. You’ll understand not just how, but why each algorithm behaves as it does.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Implementing all major algorithms → maps to algorithm diversity

- Counting comparisons accurately → maps to algorithm analysis

- Choosing optimal shellsort gaps → maps to gap sequences

- Quicksort pivot selection → maps to randomization

Key Concepts:

- Insertion Sort: TAOCP Vol 3, Section 5.2.1

- Shellsort: TAOCP Vol 3, Section 5.2.1

- Heapsort: TAOCP Vol 3, Section 5.2.3

- Quicksort: TAOCP Vol 3, Section 5.2.2

- Merge Sort: TAOCP Vol 3, Section 5.2.4

- Radix Sort: TAOCP Vol 3, Section 5.2.5

- Minimum Comparisons: TAOCP Vol 3, Section 5.3

Difficulty: Advanced Time estimate: 2-3 weeks Prerequisites:

- Basic algorithm knowledge

- C programming

- Understanding of recursion

Real world outcome:

$ ./sort_suite benchmark --size 100000

Algorithm | Time | Comparisons | Moves | Stable?

----------------|---------|--------------|-----------|--------

Insertion Sort | 2.34s | 2,500,125,000| 2,500,124,999| Yes

Shell Sort | 0.023s | 2,341,567 | 2,341,567 | No

Heap Sort | 0.021s | 2,567,891 | 1,123,456 | No

Quick Sort | 0.015s | 1,789,234 | 567,123 | No

Merge Sort | 0.019s | 1,660,964 | 1,660,964 | Yes

Radix Sort | 0.008s | 0 | 800,000 | Yes

Theoretical minimums for n=100,000:

Comparisons: n log₂ n - 1.44n ≈ 1,560,000

Merge sort achieves: 1,660,964 (within 6%!)

$ ./sort_suite visualize quicksort

[Animated ASCII visualization of quicksort partitioning...]

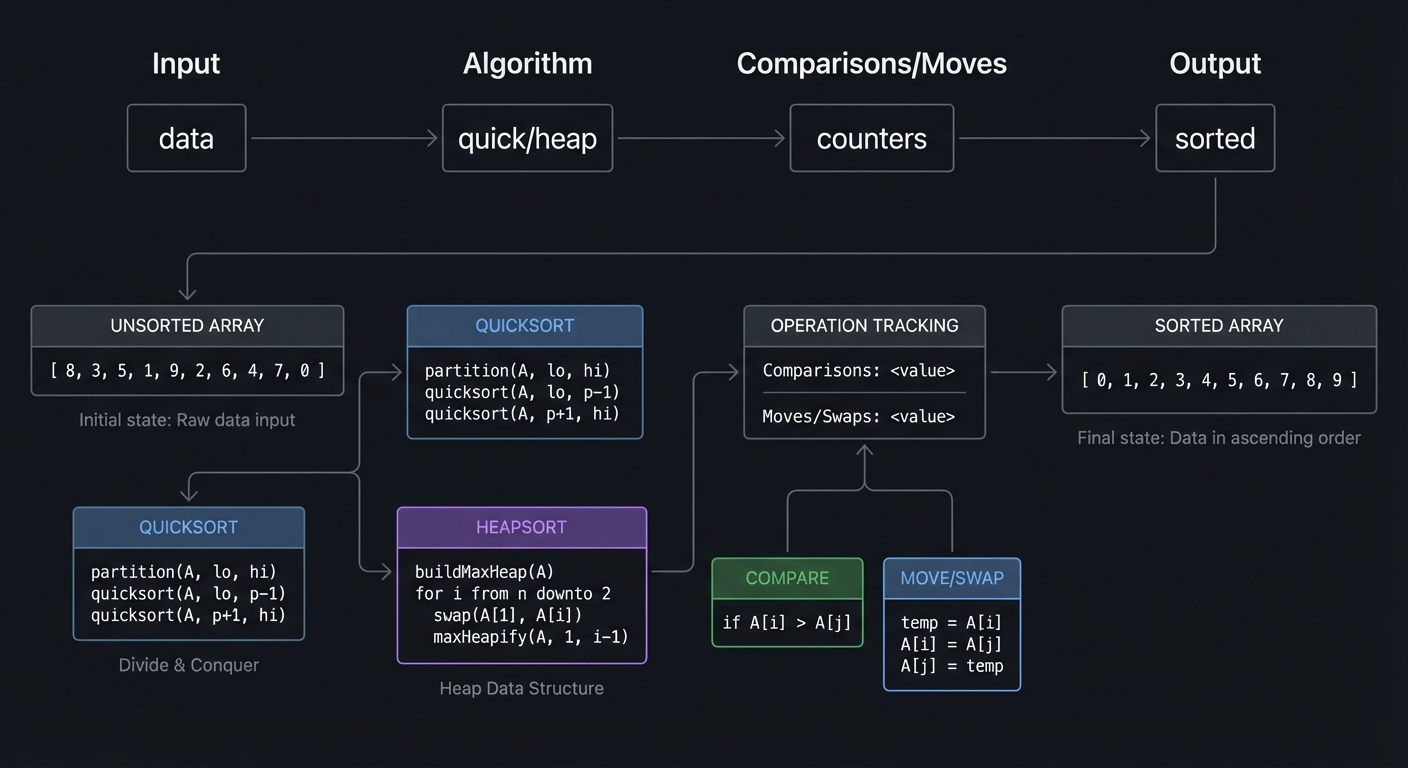

Visual Model

Input -> Algorithm -> Comparisons/Moves -> Output

| | | |

data quick/heap counters sorted

The Core Question You’re Answering

“Why do different sorting algorithms behave so differently on the same data, and how do you predict it?”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Stability and in-place constraints

- Average vs worst-case behavior

- Comparison vs distribution sorting

- Input distribution effects (nearly sorted, reversed, random)

Questions to Guide Your Design

- How will you count comparisons and moves consistently across algorithms?

- What data sets will you use to expose best/worst cases?

- Which algorithms share helper routines (partition, heapify)?

- How will you visualize and compare results fairly?

Thinking Exercise

Count the comparisons made by insertion sort on [3,1,2]. Then run your instrumentation to verify.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- Why is quicksort fast on average but risky in worst case?

- What makes a sort stable, and why does it matter?

- When is radix sort better than comparison sorts?

- How do you choose a sort for nearly-sorted data?

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Implement Insertion, Merge, Heap First These give you stable and worst-case guarantees.

Hint 2: Add Quicksort with Good Pivoting Use median-of-three or randomized pivots.

Hint 3: Add Shell and Radix Compare comparison-based to distribution-based sorts.

Hint 4: Instrument Every Operation Wrap comparisons and moves in macros.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Sorting analysis | TAOCP Vol 3 | Ch. 5 |

| Practical sorting | Algorithms in C | Part 3 |

| Complexity insights | Algorithms, 4th Edition | Ch. 2 |

| Data movement | Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective | Ch. 6 |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem: “Comparison counts don’t match theory”

- Why: Counting extra comparisons in loop conditions.

- Fix: Wrap only the value comparisons, not loop checks.

- Quick test: Validate on tiny arrays with known counts.

Problem: “Quicksort blows stack”

- Why: Worst-case recursion depth from bad pivots.

- Fix: Use tail recursion elimination or always recurse on smaller partition.

- Quick test: Sort already sorted input and ensure depth stays small.

Implementation Hints:

Shellsort with good gap sequence:

// Knuth's sequence: 1, 4, 13, 40, 121, ... (3^k - 1)/2

void shellsort(int* a, int n) {

int gap = 1;

while (gap < n/3) gap = gap * 3 + 1;

while (gap >= 1) {

for (int i = gap; i < n; i++) {

for (int j = i; j >= gap && a[j] < a[j-gap]; j -= gap) {

swap(&a[j], &a[j-gap]);

}

}

gap /= 3;

}

}

Quicksort with median-of-three:

int partition(int* a, int lo, int hi) {

// Median of three pivot selection

int mid = lo + (hi - lo) / 2;

if (a[mid] < a[lo]) swap(&a[mid], &a[lo]);

if (a[hi] < a[lo]) swap(&a[hi], &a[lo]);

if (a[mid] < a[hi]) swap(&a[mid], &a[hi]);

int pivot = a[hi];

int i = lo;

for (int j = lo; j < hi; j++) {

if (a[j] < pivot) {

swap(&a[i], &a[j]);

i++;

}

}

swap(&a[i], &a[hi]);

return i;

}

Heapsort:

1. Build max-heap in O(n) using bottom-up heapify

2. Repeatedly:

a. Swap root (maximum) with last element

b. Reduce heap size by 1

c. Heapify root down

Advantage: O(n log n) worst case, in-place

Disadvantage: Not stable, more comparisons than quicksort

Learning milestones:

- All algorithms implemented correctly → You understand sorting

- Comparison counts match theory → You understand analysis

- Can predict which is best for given data → You understand trade-offs

- Can explain each algorithm’s invariant → You truly understand sorting

Definition of Done

- All algorithms sort correctly across input distributions

- Comparison/move counters match small known cases

- Benchmarks show expected average/worst-case trends

- Stability verified for stable algorithms

Project 9: Search Tree Collection (BST, AVL, B-Trees)

- File: LEARN_TAOCP_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, C++

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 3. The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 4: Expert

- Knowledge Area: Search Trees / Balancing / Databases

- Software or Tool: Building: Tree Library

- Main Book: “The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 3” Section 6.2 - Knuth

What you’ll build: A complete collection of search trees—binary search trees, AVL trees, red-black trees (as 2-3-4 tree representation), and B-trees for disk-based storage.

Why it teaches TAOCP: Section 6.2 covers tree-based searching exhaustively. You’ll understand not just how to implement balanced trees, but the mathematics behind their height guarantees and why B-trees are optimal for disks.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- AVL rotations → maps to balance maintenance

- B-tree split and merge → maps to multi-way trees

- Red-black coloring rules → maps to 2-3-4 tree correspondence

- Disk-optimized operations → maps to I/O efficiency

Key Concepts:

- Binary Search Trees: TAOCP Vol 3, Section 6.2.2

- AVL Trees: TAOCP Vol 3, Section 6.2.3

- B-Trees: TAOCP Vol 3, Section 6.2.4

- Optimal BSTs: TAOCP Vol 3, Section 6.2.2

Difficulty: Expert Time estimate: 3-4 weeks Prerequisites:

- Project 4 (basic trees)

- Understanding of tree rotations

- Binary search knowledge

Real world outcome:

$ ./tree_collection

# Compare tree heights

tree> insert_random 10000

AVL tree:

Nodes: 10000

Height: 14

Theoretical max: 1.44 log₂(10001) ≈ 19.2

Actual/max: 73% (well balanced!)

B-tree (order 100):

Nodes: 10000

Height: 2

Minimum height: log₁₀₀(10000) = 2 ✓

# Visualize rotations

tree> insert_avl_trace 5 3 7 2 4 6 8 1

Inserting 5: Root is 5

Inserting 3: Left of 5

Inserting 7: Right of 5

Inserting 2: Left of 3

Inserting 4: Right of 3

Inserting 6: Left of 7

Inserting 8: Right of 7

Inserting 1: Left of 2

Balance factor of 3 is now 2 (left-heavy)

Performing RIGHT rotation at 3:

5 5

/ \ / \

3 7 → 2 7

/ \ / \

2 4 1 3

/ \

1 4

# B-tree disk operations

tree> btree_create "index.db" order=100

tree> btree_insert_bulk data.csv

Inserted 1,000,000 keys

Disk reads: 3 per lookup (height 3)

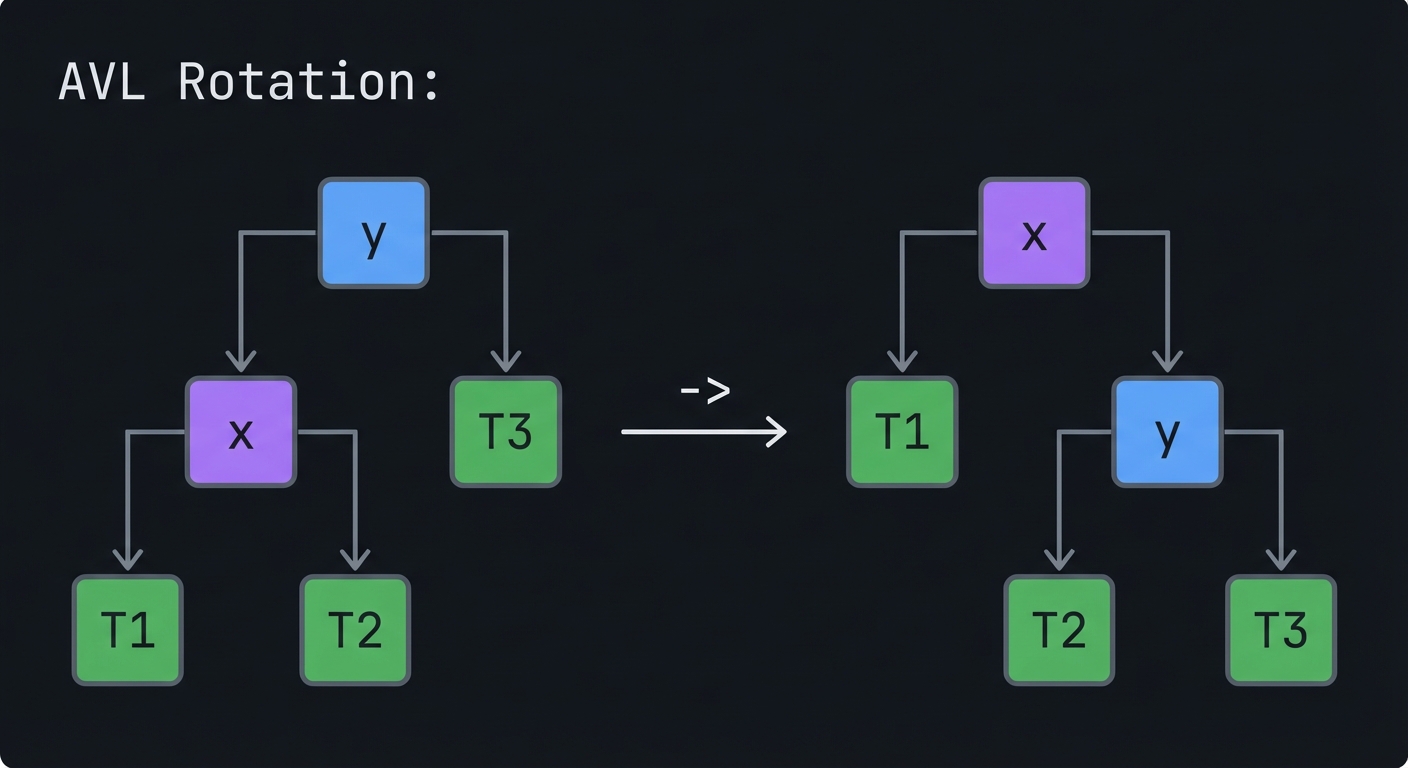

Visual Model

AVL Rotation:

y x

/ \ / \

x T3 -> T1 y

/ \ / \

T1 T2 T2 T3

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do balanced trees guarantee log-time operations, and why do B-trees dominate disk-based storage?”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Tree height invariants and balance factors

- Rotations (single and double)

- B-tree node capacity and split/merge

- Disk I/O model (block size vs height)

Questions to Guide Your Design

- How will you store parent pointers and node metadata?

- When do you trigger rotations or splits?

- How will you persist B-tree nodes to disk?

- What tests confirm height bounds for each tree?

Thinking Exercise

Insert 10, 20, 30 into an AVL tree. Show the rotation and the final shape.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- Compare AVL trees to red-black trees.

- Why are B-trees ideal for disks or SSDs?

- How do you implement a B-tree split?

- What is the amortized cost of rebalancing?

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Build a Correct BST First If your BST is wrong, rotations will not fix it.

Hint 2: Add AVL Rotations Implement single rotations, then double rotations.

Hint 3: Implement B-Tree Insert Handle splitting a full node before descent.

Hint 4: Add Disk Simulation Count block reads/writes to validate I/O efficiency.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Balanced trees | TAOCP Vol 3 | Ch. 6.2 |

| Search trees | Algorithms, 4th Edition | Ch. 3 |

| Disk-based structures | Algorithms in C | Part 5 |

| Data layout | Computer Organization and Design | Ch. 5 |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem: “AVL height metadata is wrong”

- Why: Not updating heights after rotations.

- Fix: Recompute heights bottom-up for affected nodes only.

- Quick test: Validate balance factors for every node after inserts.

Problem: “B-tree insert corrupts structure”

- Why: Split logic does not move the median key correctly.

- Fix: Carefully copy left/right halves and promote the median.

- Quick test: After each insert, traverse nodes and verify key ordering.

Implementation Hints:

AVL rotation:

Node* rotate_right(Node* y) {

Node* x = y->left;

Node* T = x->right;

x->right = y;

y->left = T;

y->height = 1 + max(height(y->left), height(y->right));

x->height = 1 + max(height(x->left), height(x->right));

return x; // New root

}

int balance_factor(Node* n) {

return height(n->left) - height(n->right);

}

// After insert, walk back up and rebalance

// |balance_factor| > 1 means rotation needed

B-tree structure:

#define ORDER 100 // Max children per node

typedef struct BTreeNode {

int num_keys;

int keys[ORDER - 1];

void* values[ORDER - 1];

struct BTreeNode* children[ORDER];

bool is_leaf;

} BTreeNode;

// Invariants:

// - All leaves at same depth

// - Each node has ceil(ORDER/2) to ORDER children

// - Each node has ceil(ORDER/2)-1 to ORDER-1 keys

B-tree split:

When inserting into full node:

1. Split node into two nodes

2. Median key moves up to parent

3. Left half goes to left child

4. Right half goes to right child

5. May recursively split parent

Learning milestones:

- BST operations work → You understand tree searching

- AVL maintains balance → You understand rotations

- B-tree has optimal height → You understand disk optimization

- Can implement red-black via 2-3-4 → You understand the connection

Definition of Done

- BST/AVL/B-tree insert/find/delete pass tests

- AVL height bounds hold across random inputs

- B-tree split/merge logic preserves invariants

- Disk I/O model shows expected lookup costs

Project 10: Hash Table Laboratory

- File: LEARN_TAOCP_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Go

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 3. The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Hashing / Collision Resolution / Analysis

- Software or Tool: Building: Hash Table Library

- Main Book: “The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 3” Section 6.4 - Knuth

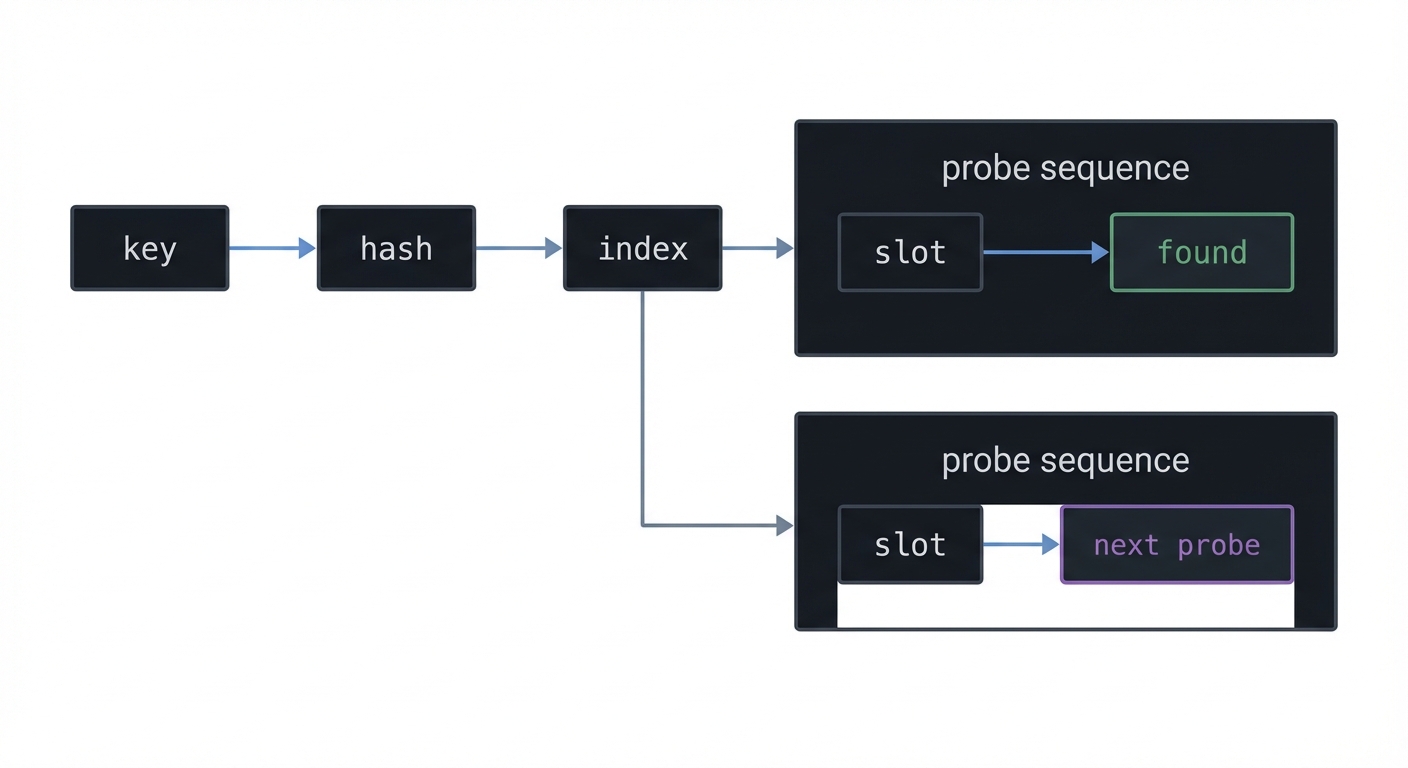

What you’ll build: A comprehensive hash table library implementing multiple collision resolution strategies—chaining, linear probing, quadratic probing, double hashing—with analysis tools.

Why it teaches TAOCP: Section 6.4 is the definitive analysis of hashing. Knuth derives the expected number of probes for each method, explains why load factor matters, and proves when linear probing clusters. You’ll understand hashing at the mathematical level.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Choosing good hash functions → maps to distribution quality

- Primary clustering in linear probing → maps to collision analysis

- Deletion in open addressing → maps to tombstones