Learn Shell Scripting: From Zero to Automation Master

Goal: Deeply understand shell scripting - from the fundamental mechanics of how shells interpret commands to advanced automation techniques that transform repetitive tasks into elegant, robust scripts. You’ll learn not just the syntax, but WHY shells work the way they do, how to think in pipelines, handle edge cases gracefully, and build tools that save hours of manual work. By the end, you’ll write scripts that are production-ready, maintainable, and genuinely useful.

Introduction: What This Guide Covers

Shell scripting is the art of composing operating-system commands into reliable programs that automate work. A shell is both a command interpreter and a programming language: it reads text, expands it, and orchestrates processes. In practice, shell scripts glue together the Unix toolbox-grep, sed, awk, find, tar, ssh, rsync, and your own programs-into repeatable workflows.

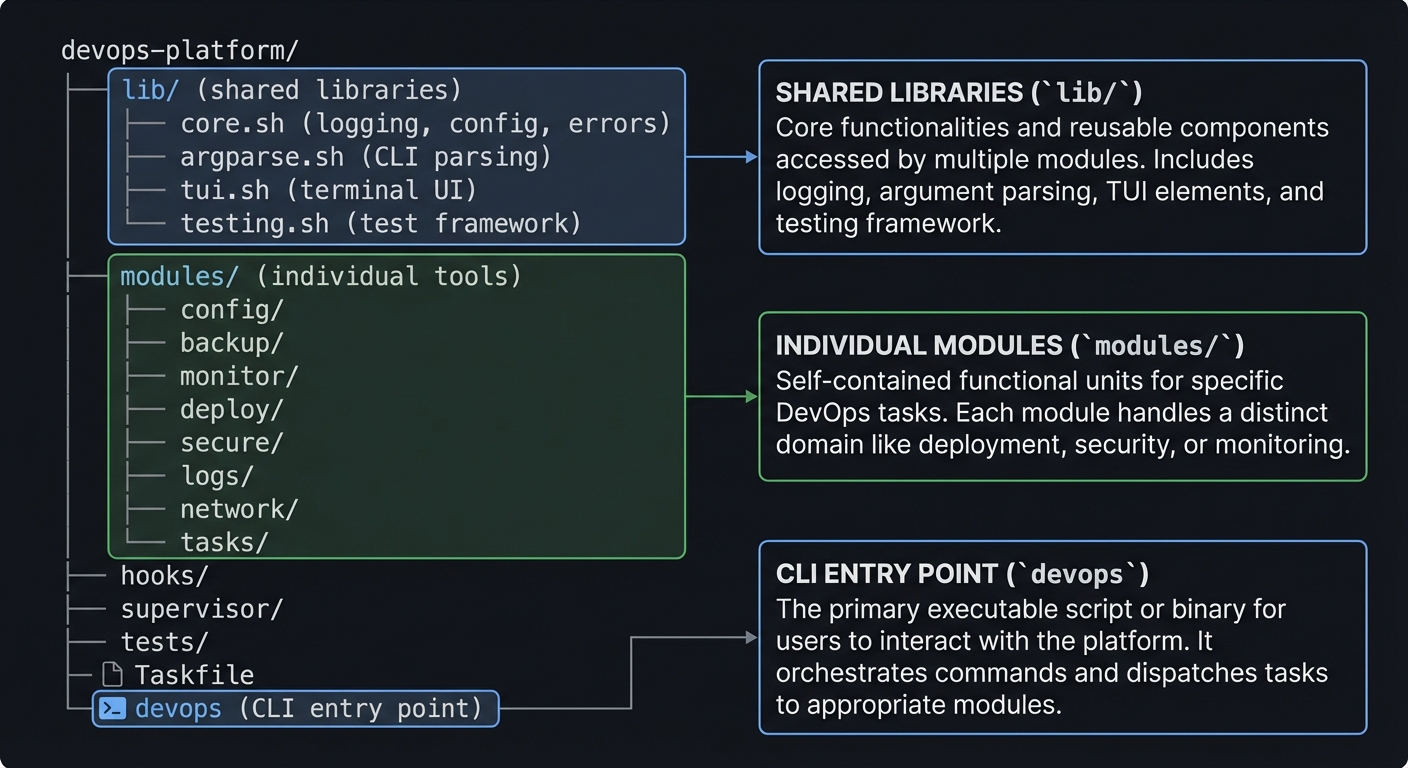

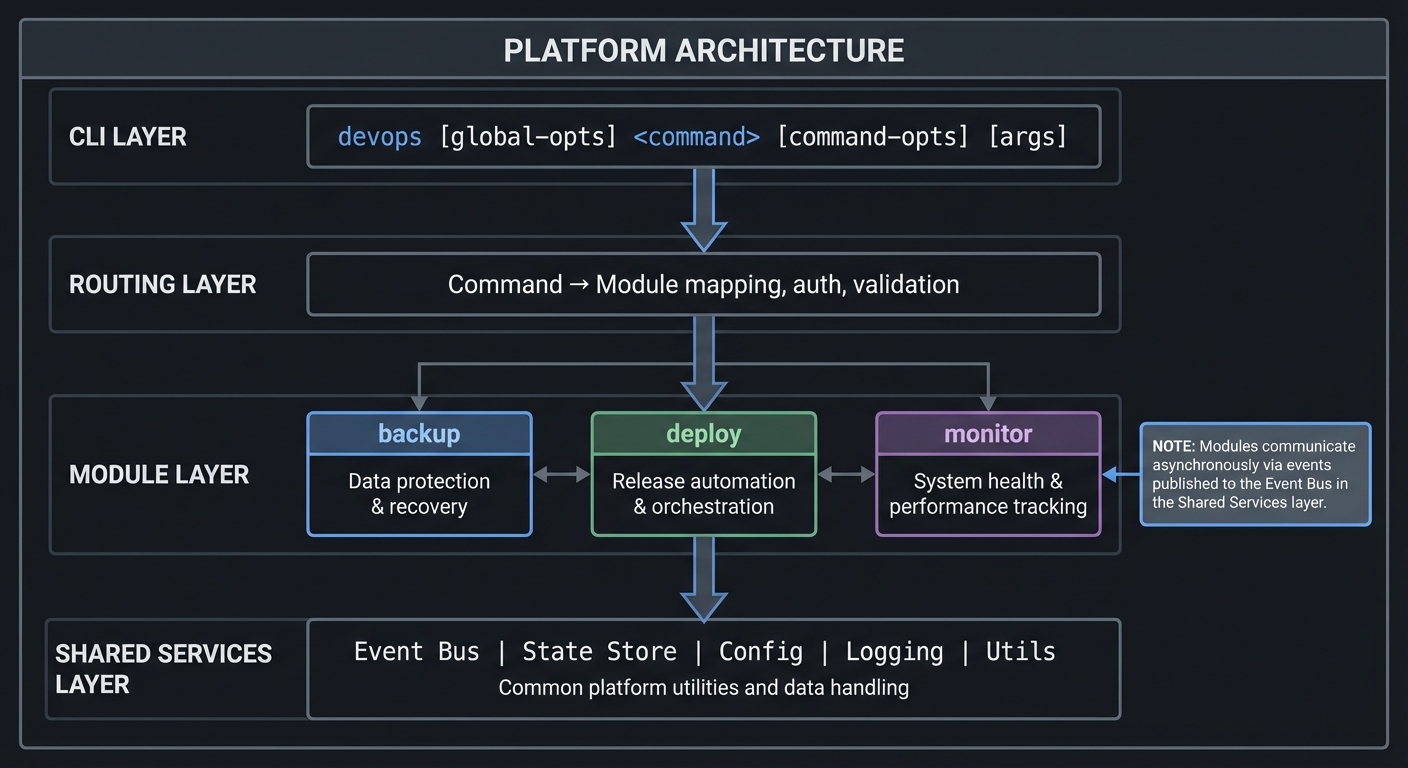

What you will build (by the end of this guide):

- A dotfiles manager, file organizer, log parser, and git hooks framework

- A backup system, system monitor dashboard, and process supervisor

- CLI libraries (argument parser, test runner, task runner)

- A network diagnostic toolkit and deployment automation tool

- A security audit scanner, interactive menu system, and mini shell

- A final integrated DevOps automation platform

Scope (what is included):

- Bash and POSIX shell scripting on Linux/macOS

- Process control, pipelines, redirection, signals, and job control

- Text processing with core Unix tools (grep/sed/awk/sort/uniq)

- Defensive scripting, testing patterns, and portability

Out of scope (for this guide):

- PowerShell (Windows-specific scripting)

- Writing kernel modules or C-based system utilities

- GUI automation frameworks

- Language-specific build systems beyond Make/Task runners

The Big Picture (Mental Model)

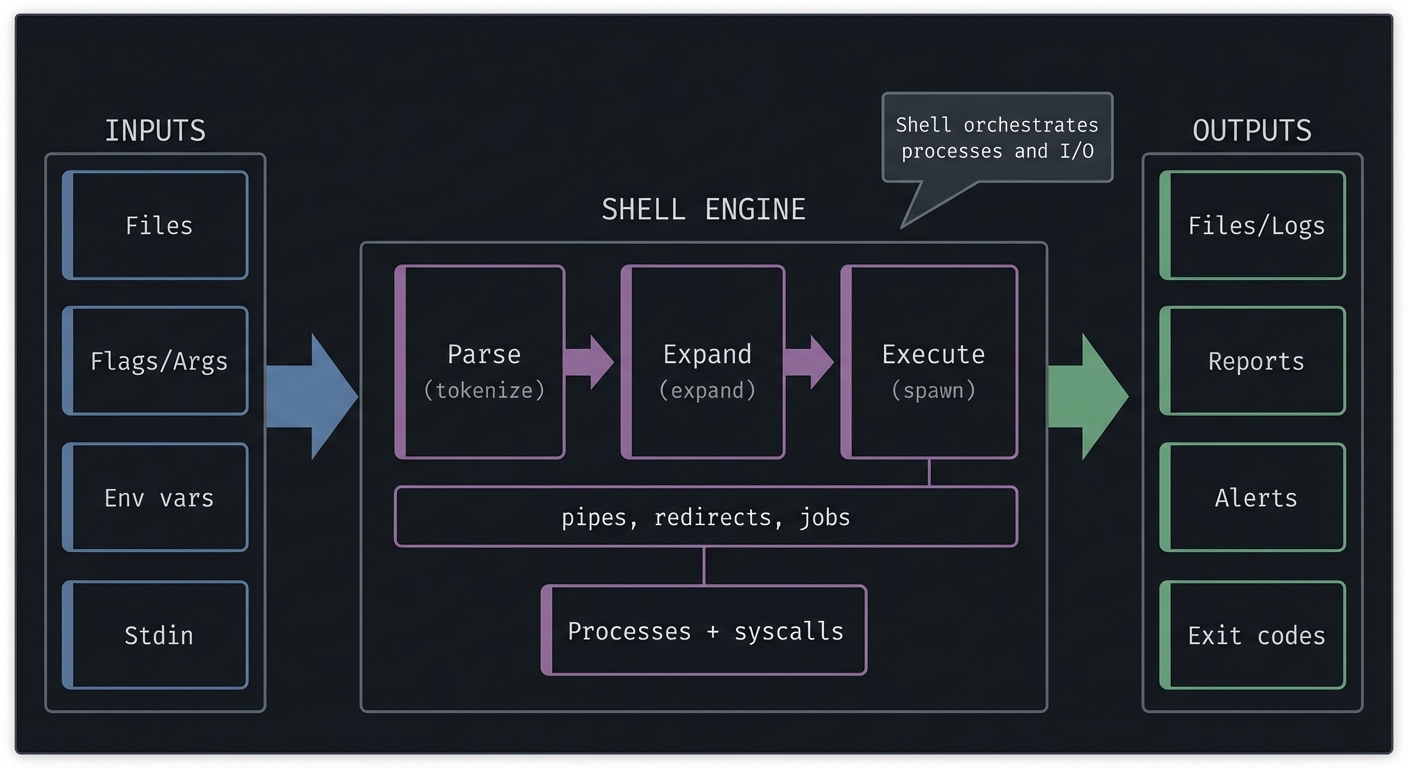

INPUTS SHELL ENGINE OUTPUTS

--------- -------------------------- -----------------

Files Parse -> Expand -> Execute Files/Logs

Flags/Args ---> (tokenize, expand, spawn) -> Reports

Env vars | pipes, redirects, jobs Alerts

Stdin v Exit codes

Processes + syscalls

Key Terms You Will See Everywhere

- Shell: The command interpreter (bash, zsh, dash). It parses and executes commands.

- Script: A file containing shell commands and logic.

- Expansion: The rules the shell uses to transform text before running commands.

- Pipeline: A chain of commands connected by

|where stdout becomes stdin. - Redirection: Connecting stdin/stdout/stderr to files, pipes, or devices.

How to Use This Guide

- Read the Theory Primer first. It explains how shells actually behave so you can predict script behavior instead of guessing.

- Do projects in increasing complexity. Each one unlocks patterns you’ll reuse later.

- Keep a scratchpad. Write down mistakes, edge cases, and the fixes you discovered.

- Test as you go. Every project includes a Definition of Done; treat it as your checklist.

- Rebuild the small tools. Re-implement early projects after a few weeks. You’ll be surprised how much faster you are.

Prerequisites & Background Knowledge

Before starting these projects, you should have foundational understanding in these areas:

Essential Prerequisites (Must Have)

Programming Skills:

- Comfort with variables, functions, and control flow (in any language)

- Basic familiarity with the terminal (cd, ls, cp, mv, rm)

- Ability to read and modify files with a text editor

Linux/Unix Fundamentals:

- File paths, permissions, and ownership

- Basic process concepts (PID, foreground/background)

- Understanding what stdin/stdout/stderr are

- Recommended Reading: “The Linux Command Line” by William Shotts - Ch. 1-6

Helpful But Not Required

Text processing tools:

- grep, sed, awk, cut, sort, uniq

- Can learn during: Project 3 (Log Parser), Project 9 (Network Toolkit)

Git basics:

- branches, commits, hooks

- Can learn during: Project 4 (Git Hooks Framework)

Networking basics:

- IP, ports, and basic tools like curl

- Can learn during: Project 9 (Network Toolkit)

Self-Assessment Questions

Before starting, ask yourself:

- Can I explain the difference between a file and a directory?

- Do I know how to redirect output with

>and>>? - Can I read a simple shell script and predict its output?

- Do I know how to search files with

grep? - Have I used a terminal regularly for at least a few weeks?

If you answered “no” to questions 1-3: Spend 1-2 weeks with “The Linux Command Line” (Ch. 1-12). If you answered “yes” to all 5: You are ready to begin.

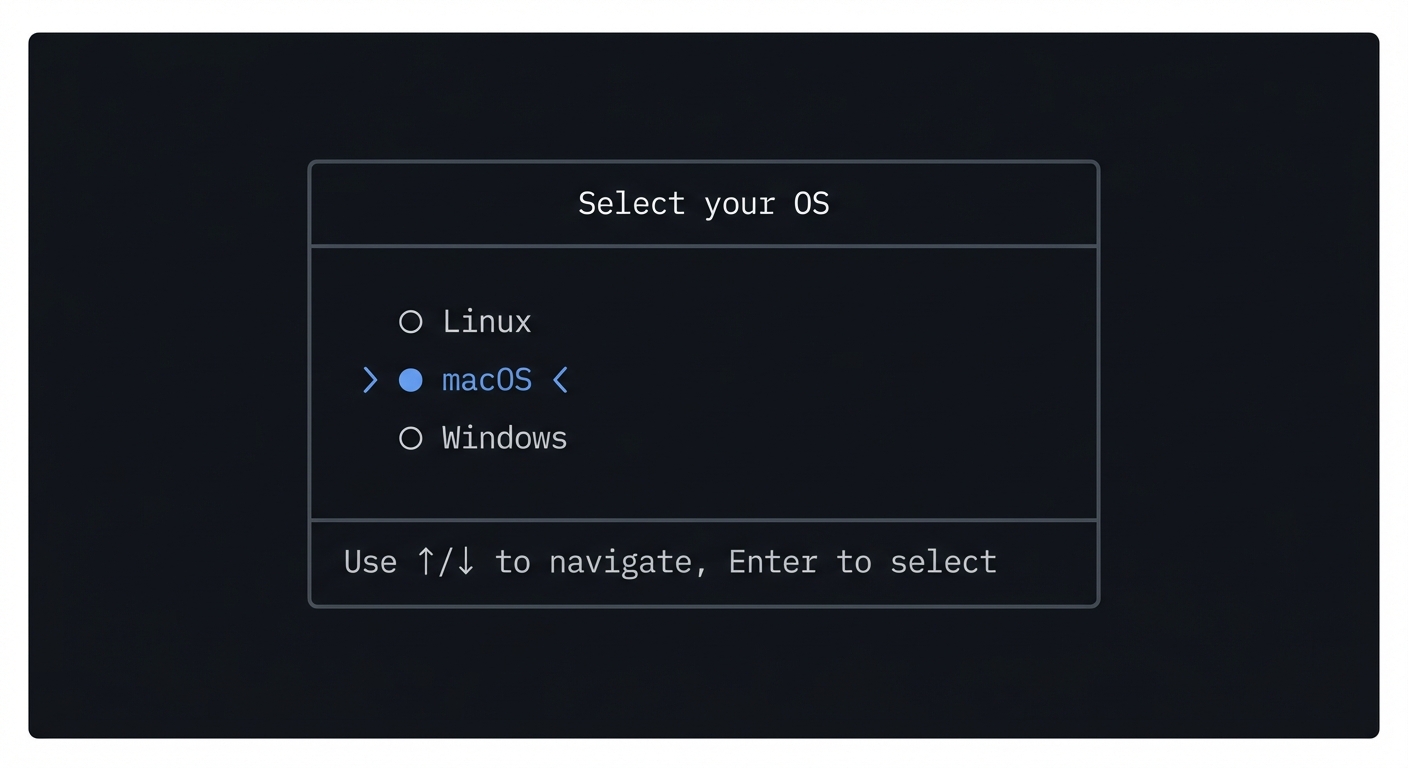

Development Environment Setup

Required Tools:

- A Linux machine (Ubuntu 22.04+ recommended) or macOS

- Bash 5.x+ (macOS users:

brew install bash) - Core Unix tools:

grep,sed,awk,find,xargs,tar,rsync - Git for version control

Recommended Tools:

shellcheckfor static analysisshfmtfor consistent formattingbatsfor testing (Projects 7 and 11)tmuxfor long-running sessions

Testing Your Setup:

$ bash --version

GNU bash, version 5.x

$ command -v awk sed grep

/usr/bin/awk

/usr/bin/sed

/usr/bin/grep

Time Investment

- Simple projects (1, 2, 14): Weekend (4-8 hours each)

- Moderate projects (3, 4, 5, 11): 1-2 weeks each

- Complex projects (6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 15): 2-4 weeks each

- Final capstone (DevOps Platform): 2-3 months

Important Reality Check

Shell scripting mastery is not about memorizing syntax. It is about learning to think in streams, predict expansion, and design reliable automation. Expect to:

- Build something that works

- Debug edge cases

- Refactor into clean, reusable functions

- Learn the true behavior of the shell

That cycle is the point.

Big Picture / Mental Model

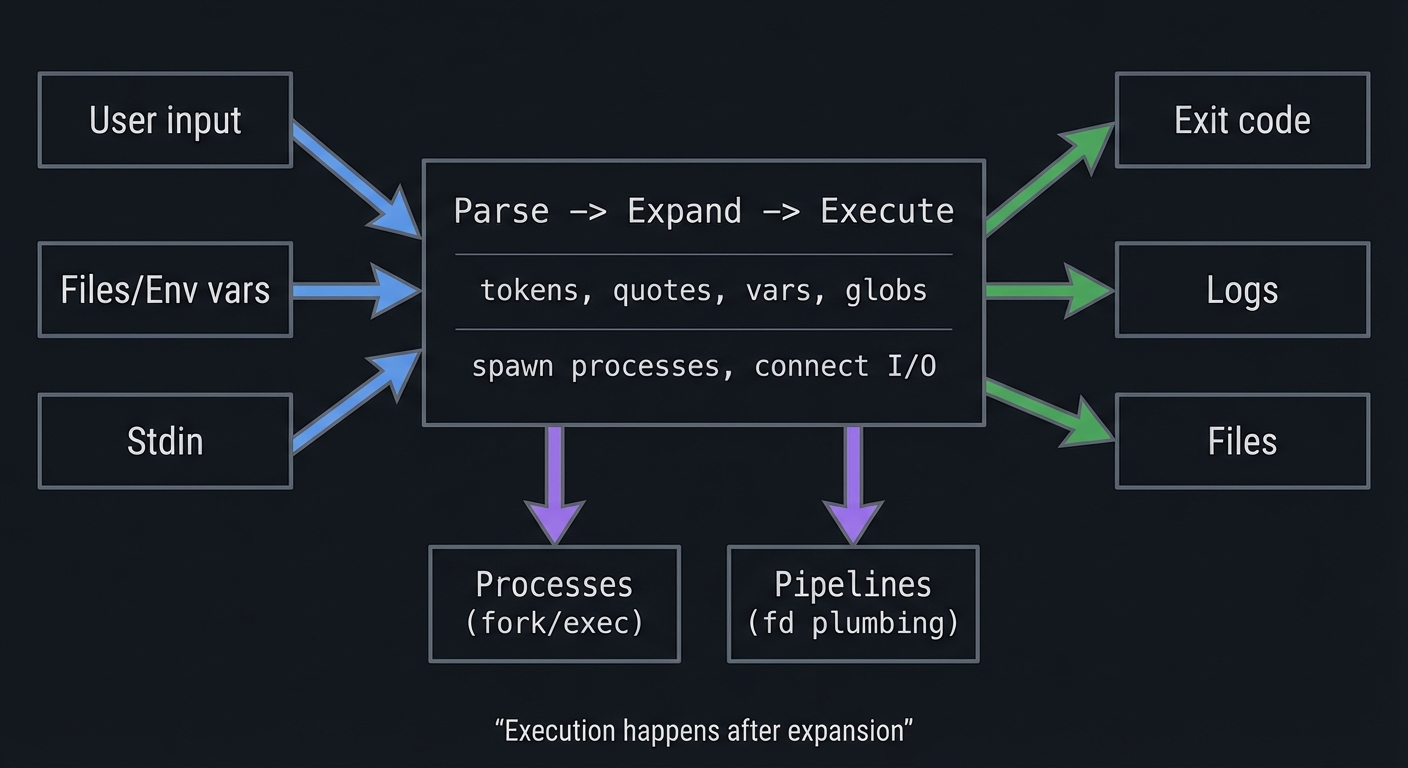

A shell script is a process coordinator. It does not do heavy computation itself; it orchestrates other programs and the OS.

+-------------------------------+

User input ----> | Parse -> Expand -> Execute | ----> Exit code

Files/Env vars ->| (tokens, quotes, vars, globs) | ----> Logs

Stdin ---------->| spawn processes, connect I/O | ----> Files

+-------------------------------+

| |

v v

Processes Pipelines

(fork/exec) (fd plumbing)

The mental model to keep in your head:

- Text becomes tokens (lexing)

- Tokens become words (expansion and splitting)

- Words become commands (execution)

- Commands become processes (fork/exec)

- Processes communicate via file descriptors (pipes/redirection)

Theory Primer (Read This Before Coding)

This section is the mini-book. Read it before you start coding. Every project is an application of one or more chapters below.

Chapter 1: Parsing, Quoting, and Expansion (The Language Engine)

Fundamentals

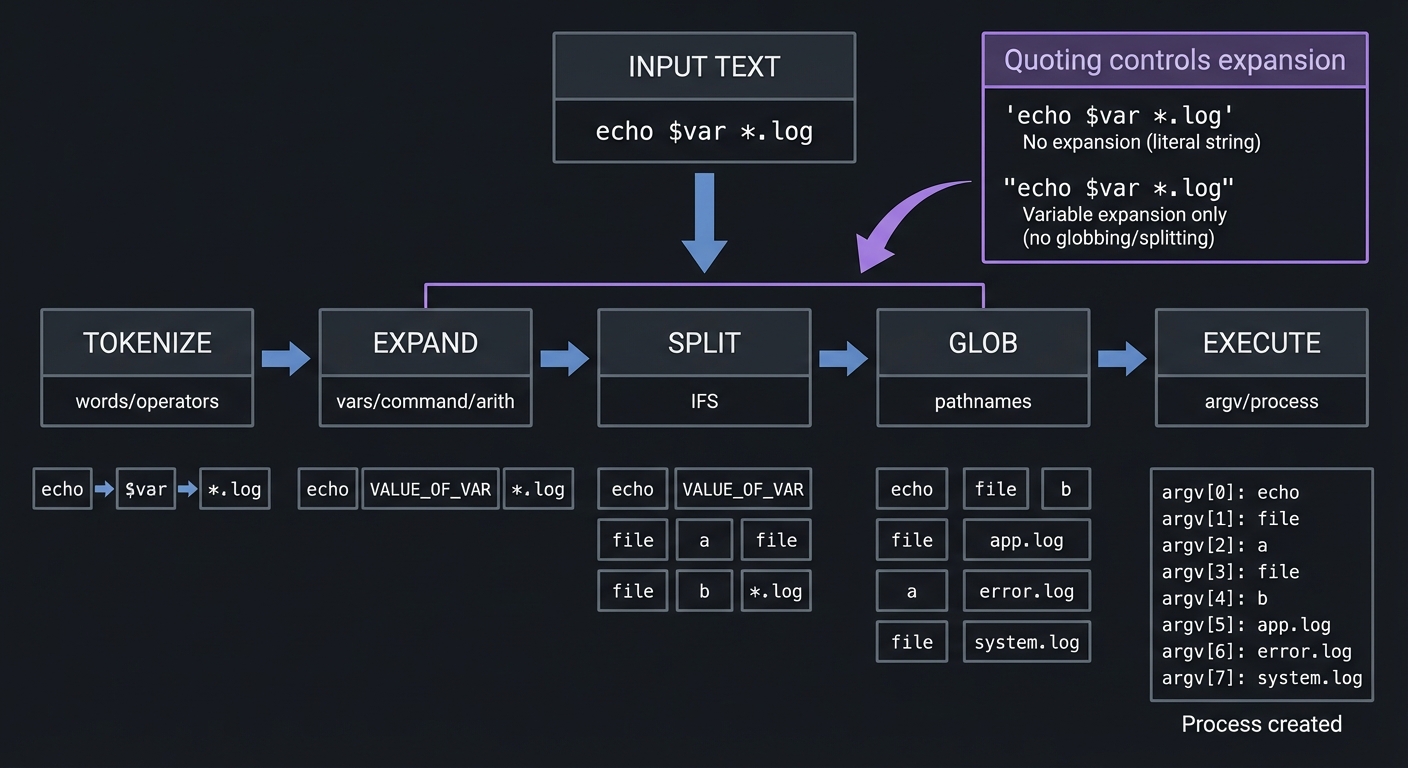

Shells do not execute the text you type directly. They first parse it into tokens and then run a fixed sequence of expansions that transform those tokens into the final arguments passed to a command. This is why the same script can behave correctly in one case and explode in another: it is not the command that is wrong, it is your assumptions about parsing that are wrong. At a high level, the shell reads characters, groups them into words, applies expansions, splits words into fields, and only then runs a command. That ordering matters. If you understand it, you stop fearing shell scripts; you can predict them.

Quoting is the single most important control you have over parsing. Unquoted variables are subject to word splitting and globbing. That means a variable that contains spaces, tabs, or newlines can explode into multiple arguments, and characters like * and ? can expand into filenames. The safe default is to quote variables: "$var". That simple habit prevents a majority of real-world shell bugs, including accidental file deletion and wrong command arguments. ShellCheck repeatedly flags unquoted variables because the risk is so high. The POSIX shell specification describes an ordered expansion process, and Bash adds extra expansion features that can change behavior if you are not deliberate. You will see this again and again in the projects.

Another fundamental is parameter expansion. This is the feature that lets you transform variables without calling external commands. It is both more efficient and more reliable because it happens before word splitting. If you know ${var%.*} to strip a file extension or ${var// /_} to replace spaces, you avoid invoking sed or awk inside loops. That makes your script faster, safer, and easier to read. The shell is not just a glue language; it has a real string manipulation toolkit.

Finally, the shell is not a general-purpose programming language. Its syntax is deeply tied to string expansion rules. That makes it powerful for text-based pipelines but dangerous for complex data structures. Learn the expansion rules well, and the shell becomes predictable. Treat it like Python, and it will punish you.

Deep Dive into the Concept

The POSIX shell command language defines expansions in a strict order. Bash follows this order with some Bash-specific features. The exact order matters because each phase changes the text that the next phase sees. The major steps are: brace expansion (Bash-specific), tilde expansion, parameter expansion, command substitution, arithmetic expansion, field splitting, pathname expansion (globbing), and quote removal. The key is that word splitting happens after parameter and command expansion, so the content of a variable can create multiple words if it is unquoted. Then pathname expansion happens on those words. This is why rm $files is dangerous: if $files is "*.log" unquoted, it can expand to every log file in the directory. If $files contains "report 2024", it becomes two arguments. The safest pattern is almost always rm -- "$files", which forces a single argument and prevents accidental option parsing.

Parsing also involves recognizing operators (|, &&, ;, >, <) before the shell looks at expansions. That means the character | inside quotes is just a literal pipe character in the argument, but outside quotes it splits the pipeline. Similarly, > outside quotes becomes a redirection operator; inside quotes it is literal text. Understanding this lets you intentionally construct commands that contain these characters without confusing the parser.

Quoting is subtle because it is not just “on” or “off”. Single quotes preserve literal text exactly (no expansion). Double quotes allow parameter, command, and arithmetic expansion but prevent word splitting and globbing. Backslash escapes the next character in many contexts. ANSI-C quotes ($'...') allow escape sequences in Bash but are not portable. The most reliable approach for scripts is: use double quotes around variables; use single quotes for literal strings; only use backslash escapes when you have to. Avoid unquoted strings unless you explicitly want word splitting or globbing. When you do want splitting, be explicit about it by setting IFS locally or using arrays.

Field splitting is governed by the IFS variable, which defaults to space, tab, and newline. If you read a file line by line with for line in $(cat file), you are not reading lines; you are splitting on whitespace. This is one of the most common beginner bugs. The safer pattern is while IFS= read -r line; do ...; done < file, which preserves whitespace and avoids backslash escapes. That single line demonstrates the intersection of parsing, quoting, and field splitting. If you deeply understand why it works, you will write correct shell scripts for the rest of your career.

Parameter expansion has default values, error checking, pattern removal, and substring extraction. ${var:-default} substitutes a default if var is unset or empty. ${var:?message} aborts the script with a message if var is missing. ${var#pattern} removes the shortest matching prefix, ${var##pattern} removes the longest. These are not just conveniences; they are safeguards. Using ${var:?} is a defensive programming pattern that turns missing configuration into a clear error rather than a subtle bug.

Command substitution ($(...)) is another source of errors. It captures the output of a command and then is subject to word splitting unless quoted. That means files=$(ls *.log) followed by rm $files is fragile. The correct approach is to avoid command substitution for file lists entirely: use globs directly, or populate arrays with mapfile/readarray, or iterate with find -print0 and xargs -0 or while IFS= read -r -d ''.

Finally, there is portability. POSIX shell does not have arrays, [[ ]], or ${var//pat/repl}. Bash does. If your scripts must run on /bin/sh (often dash on Ubuntu), you must restrict yourself to POSIX features. That decision should be explicit at the top of your script, usually by choosing the right shebang (#!/usr/bin/env bash vs #!/bin/sh). Portability is a design choice, not an accident.

How This Fits on Projects

This chapter powers Projects 1-5 (file-heavy automation), Project 7 (CLI parser), Project 11 (test framework), and Project 15 (mini shell). If you cannot predict expansion, you cannot correctly parse arguments or filenames. These projects force you to handle whitespace, globbing, and command substitution safely.

Definitions & Key Terms

- Token: A syntactic unit recognized by the parser (word, operator, redirection).

- Expansion: The transformation of text into its final form before execution.

- Field splitting: Breaking expanded text into separate words based on

IFS. - Globbing: Pathname expansion of patterns like

*.txt. - Quoting: The mechanism that controls which expansions apply.

Mental Model Diagram

INPUT TEXT

"echo $var *.log"

|

v

TOKENIZE -> EXPAND -> SPLIT -> GLOB -> EXECUTE

words vars IFS files process

How It Works (Step-by-Step)

- Shell reads characters and identifies tokens and operators.

- Quoting is recorded; operators like

|and>are recognized. - Expansions run: parameter, command, arithmetic, tilde, brace (Bash).

- Field splitting occurs on unquoted expansions using

IFS. - Globbing expands patterns into file names.

- Quotes are removed; final argv is built and executed.

Minimal Concrete Example

name="Ada Lovelace"

files="*.log"

# Unsafe

rm $files # expands to matching files

printf "%s\n" $name # splits into 2 words

# Safe

rm -- "$files" # literal *.log unless globbed intentionally

printf "%s\n" "$name"

Common Misconceptions

- “Quotes are optional if my variables are simple.” -> They are not. You cannot guarantee future content.

- “Command substitution gives me lines.” -> It gives you words, split on

IFS. - “Globs are like regex.” -> They are simpler and match filenames, not strings.

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- Why does

rm $filesometimes delete multiple files? - What is the difference between single and double quotes in Bash?

- Why is

for f in $(cat file)incorrect for line processing? - What does

${var:?}do and when should you use it?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- Because

$fileis unquoted, it is subject to word splitting and globbing. - Single quotes prevent all expansion; double quotes allow variable/command expansion but prevent splitting/globbing.

$(cat file)produces a single string that is then split on whitespace, not on lines.- It aborts with an error if

varis unset or empty, preventing silent failures.

Real-World Applications

- Safe file management tools (Projects 1 and 2)

- Parsing complex command lines (Project 7)

- Input validation and configuration handling (Project 10)

Where You Will Apply It

- Project 1: Dotfiles Manager

- Project 2: File Organizer

- Project 3: Log Parser

- Project 7: CLI Argument Parser

- Project 11: Test Framework

- Project 15: Mini Shell

References

- POSIX Shell Command Language - “Shell Expansions” (The Open Group): https://pubs.opengroup.org/onlinepubs/9699919799/utilities/V3_chap02.html

- GNU Bash Reference Manual - “Shell Expansions” and “Quoting”: https://www.gnu.org/software/bash/manual/bash.html

- ShellCheck Wiki - “SC2086: Double quote to prevent globbing and word splitting”: https://www.shellcheck.net/wiki/SC2086

Key Insight

If you can predict how the shell expands text, you can predict almost every bug before it happens.

Summary

Parsing and expansion are the core of shell behavior. Quoting controls expansion, and expansion determines what the command actually receives. Most shell bugs are not logic bugs; they are expansion bugs.

Homework / Exercises

- Write a script that lists files matching a user-supplied pattern safely.

- Demonstrate the difference between

"$@"and"$*". - Create a test file with spaces and newlines and handle it safely.

Solutions

- Use

printf '%s\n' -- "$pattern"andfor f in $patternonly if you intend globbing. "$@"preserves arguments;"$*"joins them into one string.- Use

while IFS= read -r line; do ...; done < fileto preserve whitespace.

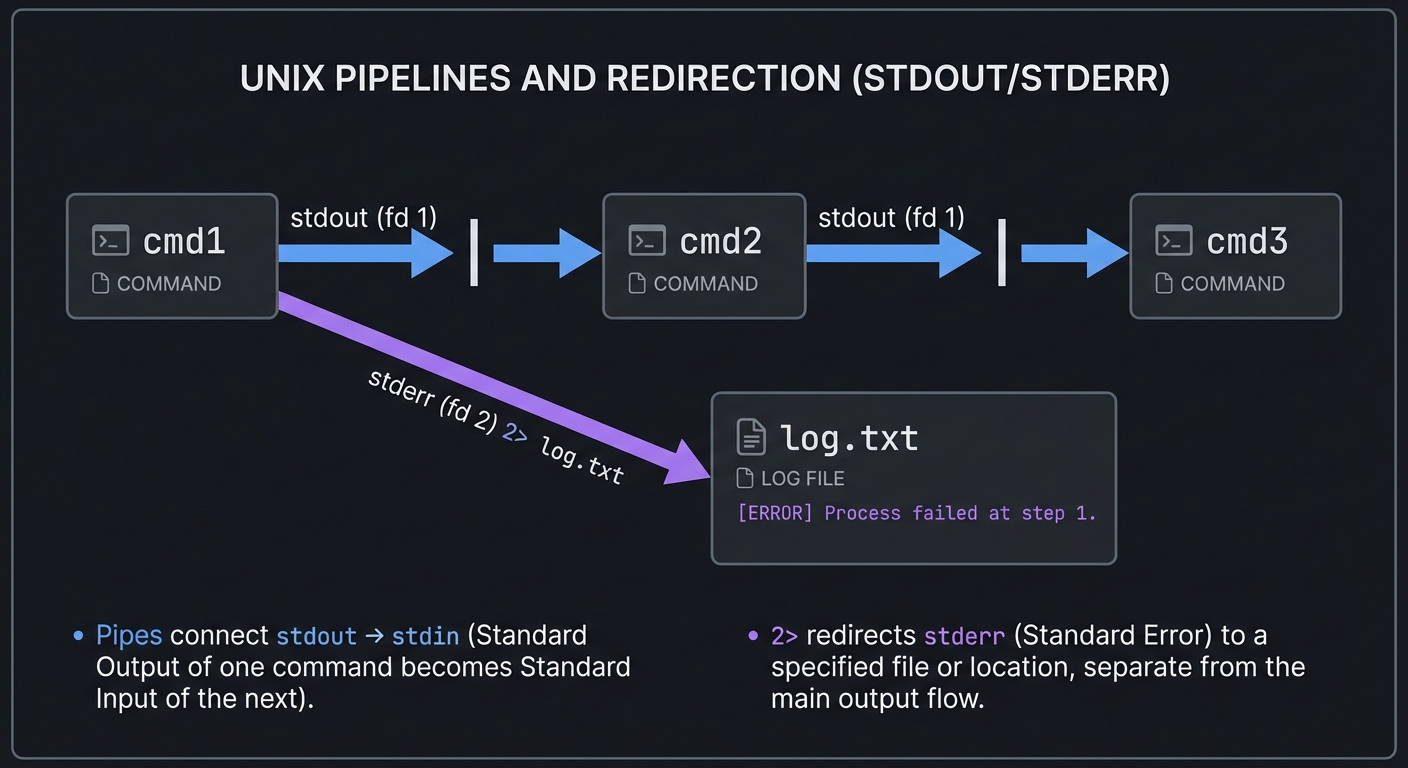

Chapter 2: Streams, Redirection, and Pipelines (The Plumbing)

Fundamentals

Every process on Unix has three default file descriptors: stdin (0), stdout (1), and stderr (2). Shell scripts are powerful because they let you connect these file descriptors like LEGO bricks. Redirection lets you send output to files, read input from files, or merge streams. Pipelines let you feed the output of one command directly into another. This is the heart of the Unix philosophy: build small tools, connect them with pipes, and compose them into workflows.

Understanding file descriptors is not optional. If you send errors to stdout, you corrupt your data stream. If you forget to close a pipe, your script hangs waiting for EOF. If you redirect inside a loop, you can unintentionally truncate a file on every iteration. You must know which stream you are using and why. When your scripts get complex, you may create additional file descriptors (3, 4, 5) to manage logs, temporary files, or parallel streams. This is advanced, but it is often the difference between a hack and a robust tool.

Pipelines are also subtle: in many shells, each pipeline segment runs in a subshell. That means variable changes in one segment do not affect the parent shell. This is why cmd | while read line; do count=$((count+1)); done often leaves count unchanged. Knowing this leads you to safer patterns, such as process substitution or redirection into a loop. Bash has pipefail to detect failures in any segment of a pipeline, which is critical for reliability. Without it, a failing command can be masked by a successful last command.

Deep Dive into the Concept

Redirection is specified by the shell before the command runs. The shell opens files, creates pipes, and duplicates file descriptors so the process inherits the correct I/O setup. This means redirection errors happen before command execution. For example, cmd > /root/file fails because the shell cannot open the file, even if cmd itself would have worked. Understanding this helps you debug errors that look like they are in your command but are actually in the redirection.

The syntax is compact but exact: > truncates a file, >> appends, < reads, 2> redirects stderr, 2>&1 merges stderr into stdout, and &> redirects both (Bash). Here-documents (<<EOF) allow you to embed input directly in the script, and here-strings (<<<) pass a single string as stdin. Process substitution (<(cmd) or >(cmd)) creates a named pipe or /dev/fd entry so you can treat a command like a file. That unlocks patterns like diff <(cmd1) <(cmd2).

Pipelines are not just about speed; they are about structure. Each command should do one transformation. This is why grep | awk | sort | uniq remains the canonical example. But you must respect buffering: some commands buffer output when not connected to a terminal. Tools like stdbuf or grep --line-buffered can help in streaming scenarios. In monitoring scripts, a buffered command can look like a hang.

Exit status in pipelines is tricky. By default, most shells return the exit code of the last command in a pipeline. If grep fails (no matches) but sort succeeds, the pipeline returns success. That might be wrong for your script. Bash’s set -o pipefail changes this: the pipeline fails if any command fails. This is essential for reliable automation and is part of the recommended strict mode.

How This Fits on Projects

Pipelines and redirection power the log parser (Project 3), system monitor (Project 6), network toolkit (Project 9), and test framework (Project 11). Every project that transforms data streams depends on these concepts. If you do not understand how stdin/stdout/stderr flow, you cannot design correct tools.

Definitions & Key Terms

- File descriptor (fd): A numeric handle to an open file/stream.

- Redirection: Connecting a file descriptor to a file/pipe.

- Pipeline: A chain of commands connected with

|. - Here-document: Inline input provided to a command.

- Process substitution: Treating a command output as a file.

Mental Model Diagram

cmd1 --stdout--> pipe --stdin--> cmd2 --stdout--> cmd3

\--stderr--------------------> log.txt

How It Works (Step-by-Step)

- Shell parses the command line and identifies redirection operators.

- It opens files and creates pipes before executing the command.

- It duplicates file descriptors (dup2) so the process inherits the new I/O.

- It forks processes for each pipeline segment and connects pipes.

- Each process executes its command with the modified descriptors.

Minimal Concrete Example

# Capture stdout and stderr separately

cmd > out.log 2> err.log

# Merge stderr into stdout for a single stream

cmd > all.log 2>&1

# Process a stream

tail -f app.log | grep --line-buffered ERROR | awk '{print $1, $5}'

Common Misconceptions

- “

2>&1and> fileare interchangeable.” -> The order matters. - “Pipelines preserve variables.” -> Most pipeline parts run in subshells.

- “

cat file | while read ...is always safe.” -> It can run in a subshell and lose state.

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- Why does

cmd > file 2>&1differ fromcmd 2>&1 > file? - When do pipeline failures get masked?

- What problem does

set -o pipefailsolve? - Why might

while readin a pipeline not update variables?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- The first redirects stdout to file, then redirects stderr to stdout (file). The second redirects stderr to current stdout (terminal), then stdout to file.

- When a non-last command fails but the last command succeeds.

- It makes the pipeline fail if any component fails.

- Because the loop often runs in a subshell, so variable changes do not propagate.

Real-World Applications

- Log processing pipelines for incident response

- Streaming monitoring dashboards

- Automated ETL and report generation

Where You Will Apply It

- Project 3: Log Parser & Alert System

- Project 6: System Health Monitor

- Project 9: Network Diagnostic Toolkit

- Project 11: Test Framework & Runner

- Project 12: Task Runner

References

- GNU Bash Reference Manual - “Pipelines” and “Redirections”: https://www.gnu.org/software/bash/manual/bash.html

- Bash “set” builtin and pipefail: https://www.gnu.org/software/bash/manual/html_node/The-Set-Builtin.html

Key Insight

Pipes and redirection are the shell’s circulatory system; if you can see the streams, you can debug almost anything.

Summary

Redirection and pipelines turn isolated commands into data processing systems. Mastering file descriptors and pipeline semantics is mandatory for reliable automation.

Homework / Exercises

- Build a pipeline that extracts the top 5 IP addresses from a log file.

- Write a script that captures stdout and stderr to separate files.

- Use process substitution to compare two command outputs.

Solutions

grep -oE '([0-9]{1,3}\.){3}[0-9]{1,3}' access.log | sort | uniq -c | sort -nr | head -5cmd > out.log 2> err.logdiff <(cmd1) <(cmd2)

Chapter 3: Control Flow, Functions, and Exit Status (Program Structure)

Fundamentals

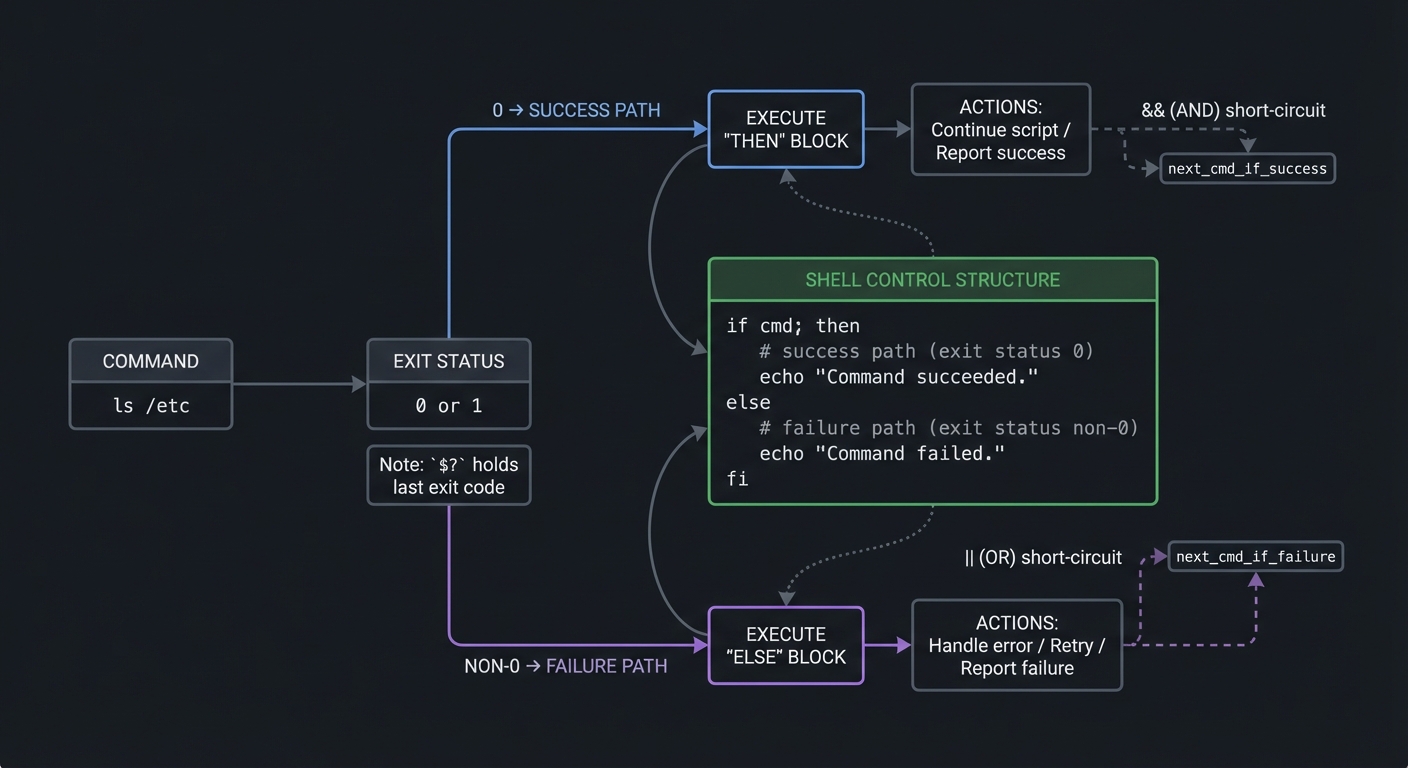

Shell scripts are programs. They have branches, loops, functions, and state. But shell control flow is built on exit status rather than Boolean types. Every command returns a numeric status: 0 means success, non-zero means failure. This is the core logic primitive of the shell. if cmd; then ...; fi does not ask if the command returned “true”; it asks if the command succeeded. Once you internalize this, you stop writing brittle if [ "$var" == true ] and start writing scripts that naturally compose with Unix commands.

The test command ([ ... ]) and Bash’s [[ ... ]] are the backbone of conditional logic. [[ ]] is safer because it avoids many word-splitting issues and supports pattern matching. The case statement is the most robust way to handle multiple command modes, especially for CLI tools. Loops (for, while, until) allow iteration, but their behavior depends on parsing rules covered in Chapter 1. If you iterate over for f in $(ls), you have already lost; if you iterate over globs or arrays, you are safe.

Functions in shell are simple but powerful. They allow modularity, reuse, and testing. But functions have subtle scoping rules: variables are global by default unless declared local (Bash). Return values are exit codes, not strings, so you typically print to stdout and capture with command substitution. This design encourages a pipeline model: functions emit data; callers capture and process it. That is different from many other languages and requires a shift in thinking.

Deep Dive into the Concept

Exit status rules are defined by POSIX. Most commands treat 0 as success, 1 as general failure, and 2 or higher for specific errors. But some tools use 1 to mean “no matches” (e.g., grep), which is not necessarily a failure in all contexts. This makes error handling nuanced. A robust script distinguishes between acceptable non-zero exit codes and fatal failures. For example, searching for a string that does not exist should not necessarily crash your script.

The set builtin controls shell behavior. set -e (errexit) causes the script to exit when a command fails, but this has exceptions: it does not trigger in all contexts, and it can be suppressed in conditional expressions. set -u (nounset) makes the shell treat unset variables as errors, which prevents silent bugs. set -o pipefail ensures pipeline failures are not masked. Together, these form the typical “strict mode” header, but you must understand their edge cases or they can backfire. Many advanced scripts implement explicit error checking rather than relying exclusively on set -e.

Function design in shell must account for global state, shared variables, and the fact that subshells receive copies. If you write count=0; cmd | while read; do count=$((count+1)); done, count will be updated in a subshell and lost. This is not a bug; it is the definition of pipeline execution. Instead, you can avoid the subshell by using redirection: while read; do ...; done < <(cmd) or while read; do ...; done < file.

case statements are the most reliable way to parse CLI arguments because they avoid nested if chains and are easy to extend. For more complex parsing, getopts or a custom parser (Project 7) is required. When you parse arguments, you must decide whether flags are global or command-specific. This design decision affects the architecture of your CLI tools.

Functions should follow a consistent contract: return status codes for success/failure and print human-readable output to stderr for errors. For reusable libraries, keep stdout clean and return data explicitly or via global variables. This distinction matters in larger tools where you want to compose functions as if they were commands.

How This Fits on Projects

Projects 1, 2, 4, 7, 11, 12, and 15 all depend on correct control flow and function design. Project 7 (CLI parser) is explicitly about control flow and argument routing, while Project 11 (test framework) depends on reliable exit status semantics.

Definitions & Key Terms

- Exit status: Numeric result of a command, used as the shell’s truth value.

- Short-circuit:

&&and||run commands based on exit status. - Function: A named block of shell code, optionally with local variables.

- Strict mode: Common combination of

set -euo pipefail.

Mental Model Diagram

[command] -> exit status

0 => success path

non-0 => failure path

if cmd; then

success actions

else

failure actions

fi

How It Works (Step-by-Step)

- Each command sets

$?to its exit status. - Conditionals and

&&/||check that status. set -ecan force an immediate exit on failure.- Functions return an exit status with

return. - Callers combine exit codes and outputs to control flow.

Minimal Concrete Example

backup_file() {

local src="$1" dst="$2"

cp -- "$src" "$dst" || return 1

return 0

}

if backup_file "$f" "$f.bak"; then

echo "backup ok"

else

echo "backup failed" >&2

fi

Common Misconceptions

- “

if [ $var ]is safe.” -> Unquoted variables can break tests. - “

set -emakes my script safe.” -> It has exceptions and can hide errors. - “Functions can return strings.” -> They return exit codes; use stdout for data.

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- Why does

grepreturning 1 sometimes not mean failure? - When can

set -ebe dangerous? - What is the difference between

returnandexit? - Why is

[[ ]]safer than[ ]in Bash?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

grepuses 1 to mean “no matches” which may be acceptable.- It can exit unexpectedly in complex conditionals or be ignored in pipelines.

returnexits a function;exitterminates the script.[[ ]]prevents word splitting and supports safer pattern matching.

Real-World Applications

- Robust CLI tools with clear error codes

- Automation scripts that fail fast with meaningful messages

- Test frameworks that aggregate pass/fail results

Where You Will Apply It

- Project 4: Git Hooks Framework

- Project 7: CLI Argument Parser

- Project 11: Test Framework

- Project 12: Task Runner

References

- POSIX Shell Command Language - “Exit Status” and “Conditional Constructs”: https://pubs.opengroup.org/onlinepubs/9699919799/utilities/V3_chap02.html

- GNU Bash Reference Manual - “Conditional Constructs” and “Shell Functions”: https://www.gnu.org/software/bash/manual/bash.html

- Bash “set” builtin: https://www.gnu.org/software/bash/manual/html_node/The-Set-Builtin.html

Key Insight

Shell control flow is not about booleans; it is about exit status. Treat success and failure as data.

Summary

You structure shell scripts by composing commands, checking exit codes, and organizing logic into functions. The more deliberate your error handling, the more trustworthy your scripts become.

Homework / Exercises

- Write a script that retries a command up to 3 times with backoff.

- Implement a

case-based CLI withstart|stop|status. - Create a function library that returns exit codes and writes errors to stderr.

Solutions

- Use a loop with

sleepand check$?after each command. case "$1" in start) ... ;; stop) ... ;; status) ... ;; *) usage ;; esac- Use

returnfor status andecho "error" >&2for errors.

Chapter 4: Processes, Jobs, and Signals (The OS Interface)

Fundamentals

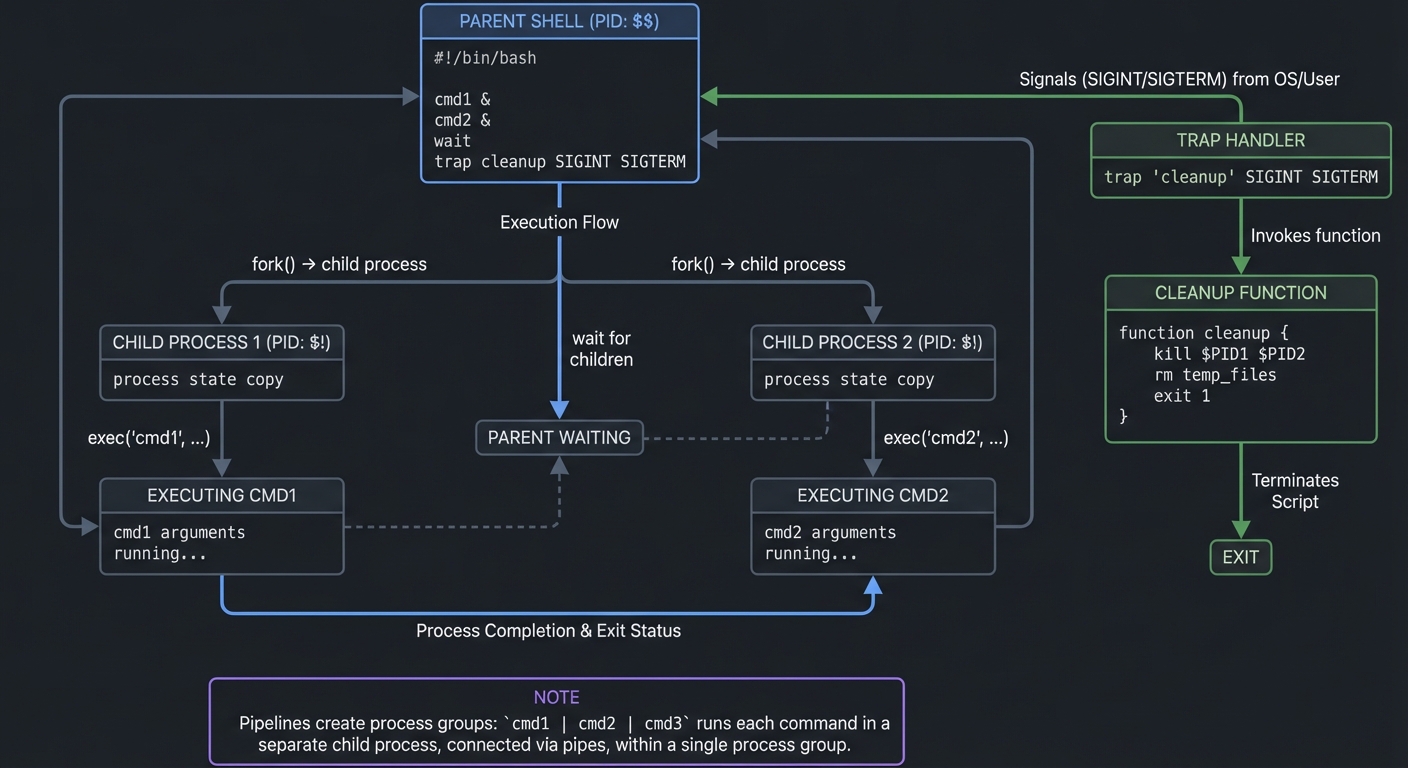

Shell scripts live in the operating system. Every command you run is a process. The shell creates processes using fork and exec, and it manages them through job control and signals. Understanding this is critical for building long-running automation, supervisors, and reliable cleanup. If you do not manage processes intentionally, your scripts will leak resources, leave zombies behind, or fail silently.

Signals are asynchronous notifications sent by the OS. SIGINT comes from Ctrl-C, SIGTERM requests graceful termination, SIGKILL is the forced kill, and SIGCHLD notifies about child process termination. trap lets you intercept these signals so you can clean up temporary files, stop child processes, and restore system state. This is essential for scripts that modify files, manage services, or run deployments.

Job control is the mechanism behind foreground/background tasks. cmd & runs a job in the background; wait blocks until a job finishes. If you start multiple background jobs, you must wait for them and track their exit codes. This is the foundation of parallel execution in shell, which you will use in the task runner and process supervisor projects.

Deep Dive into the Concept

When you run a pipeline, the shell typically creates a process group for the pipeline and sets the controlling terminal to that group. This is why Ctrl-C can interrupt the entire pipeline. Understanding process groups becomes important when you write supervisors or daemons. A daemon is just a process that detaches from the terminal, often with double-fork logic or with setsid. While you may not implement full daemonization in a beginner script, you will in the process supervisor project.

Subshells are another critical concept. Parentheses ( ... ) run commands in a subshell; braces { ...; } run in the current shell. The difference matters for state changes: cd inside a subshell does not affect the parent, but inside braces it does. Pipelines often run in subshells as well, which is why variable changes can vanish. Understanding when you are in a subshell determines whether your state changes persist.

Signals and traps are subtle. trap 'cleanup' EXIT runs when the script exits for any reason. trap '...' ERR runs when a command fails (in Bash, with set -E). You can trap SIGINT to handle Ctrl-C gracefully. But traps interact with subshells, functions, and set -e in non-obvious ways. The reliable pattern is: define cleanup in one place, set traps early, and ensure you kill child processes in the cleanup function.

Concurrency introduces race conditions. If two instances of a script run at once, they can clobber state, overwrite files, or produce corrupted output. This is why lock files exist. A common pattern is to use mkdir as an atomic lock or flock where available. You will see this in the backup and task runner projects.

How This Fits on Projects

Projects 6 (System Monitor), 8 (Process Supervisor), 9 (Network Toolkit), 10 (Deployment Tool), and the final DevOps Platform all require robust process management and signal handling.

Definitions & Key Terms

- Process: A running program with its own PID.

- Signal: An asynchronous notification to a process.

- Job control: Managing foreground/background tasks.

- Subshell: A child shell process with its own environment.

- Daemon: A long-running background process detached from the terminal.

Mental Model Diagram

Parent shell

|-- fork -> child -> exec cmd1

|-- fork -> child -> exec cmd2

\-- wait for children

Signals -> trap -> cleanup -> exit

How It Works (Step-by-Step)

- Shell forks for each external command.

- The child process replaces itself via exec.

- The parent waits for children (unless backgrounded).

- Signals can interrupt; traps allow cleanup.

- Background jobs are tracked with

$!andwait.

Minimal Concrete Example

pids=()

for host in host1 host2 host3; do

ping -c1 "$host" >/dev/null &

pids+=("$!")

done

for pid in "${pids[@]}"; do

wait "$pid" || echo "job failed" >&2

done

Common Misconceptions

- ”

&makes things safe.” -> Background jobs can fail silently. - “

traponly works on exit.” -> It works for signals too. - “Subshells are just syntax.” -> They create real processes with isolated state.

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- What is the difference between

( ... )and{ ...; }? - Why do you need to

waitfor background jobs? - How do you ensure cleanup on Ctrl-C?

- What is a zombie process and how does it occur?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- Parentheses run in a subshell; braces run in the current shell.

- Without

wait, you lose exit status and can leave zombies. - Use

trap 'cleanup' INT TERM EXIT. - A zombie is a finished child not reaped by the parent.

Real-World Applications

- Process supervisors and service managers

- Parallelized network checks

- Reliable deployment scripts with cleanup

Where You Will Apply It

- Project 6: System Health Monitor

- Project 8: Process Supervisor

- Project 9: Network Toolkit

- Project 10: Deployment Automation

- Final Project: DevOps Platform

References

- GNU Bash Reference Manual - “Job Control” and “Signals”: https://www.gnu.org/software/bash/manual/bash.html

- Bash “trap” builtin (example docs): https://manned.org/trap.1p

Key Insight

The shell is not just a scripting language; it is a process manager. If you control processes, you control automation.

Summary

Process control, job management, and signal handling are the difference between brittle scripts and reliable tools. Mastering these concepts unlocks advanced automation.

Homework / Exercises

- Write a script that runs 3 commands in parallel and fails if any one fails.

- Add a

trapthat deletes temp files on exit. - Build a simple watchdog that restarts a process if it dies.

Solutions

- Start each command with

&, capture PIDs, thenwaitand check exit codes. tmp=$(mktemp); trap 'rm -f "$tmp"' EXIT.- Loop with

while true; do cmd; sleep 1; doneandtrapto stop.

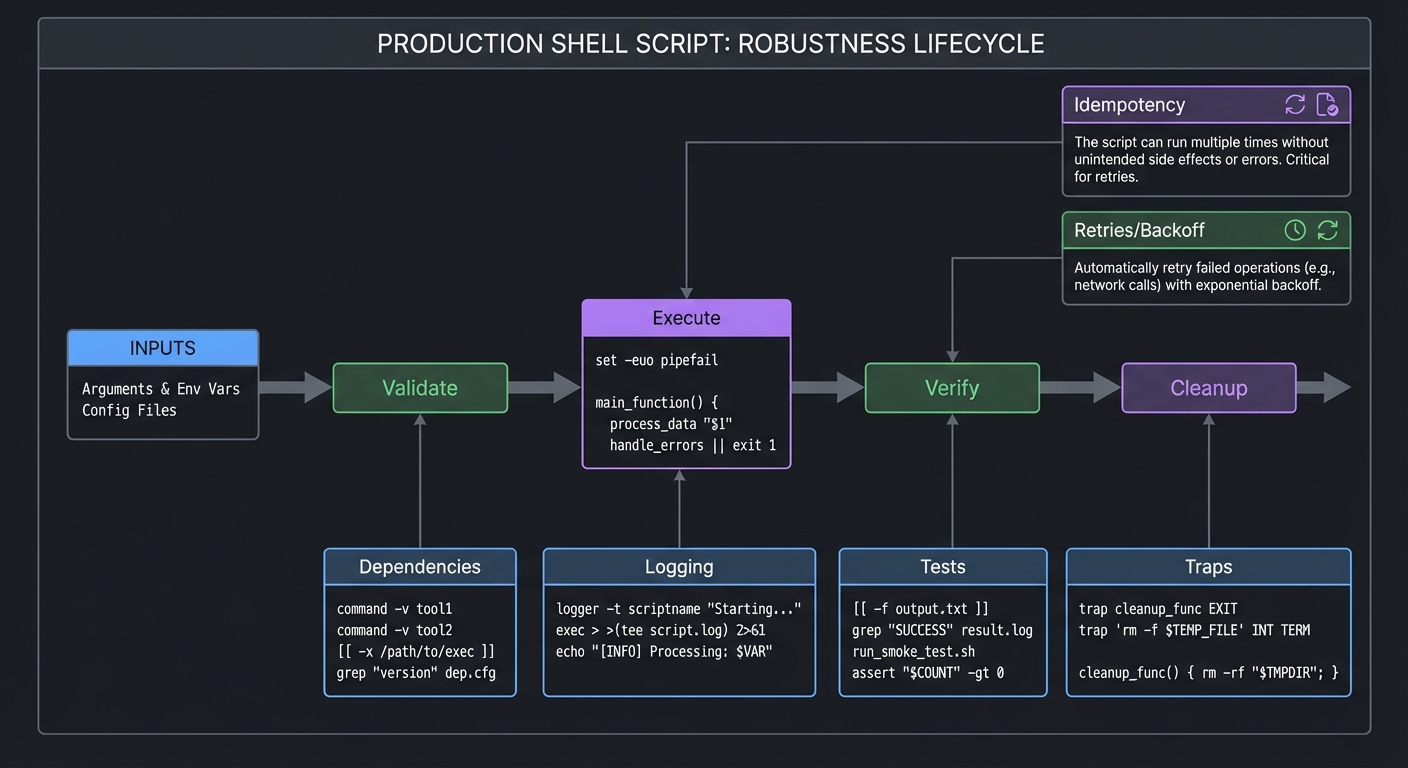

Chapter 5: Robustness, Portability, and Tooling (Production Scripts)

Fundamentals

The difference between a toy script and a production script is not the feature set; it is robustness. A production script handles missing inputs, unexpected filenames, partial failures, and concurrency. It cleans up after itself. It produces useful logs. It is consistent in its output. This chapter gives you the mindset and tools to make that shift.

Portability is a design choice. If your script runs only on your workstation, you can use Bash-specific features like arrays, [[ ]], and mapfile. If it must run on /bin/sh across diverse systems, you must restrict yourself to POSIX features. That affects your choice of syntax, command options, and built-ins. The key is to decide early and document it in the shebang and README.

Security is also part of robustness. Shell scripts often run with elevated permissions or handle sensitive files. That means you must protect against unsafe expansion, malicious filenames, and command injection. A safe script always quotes variables, uses -- to terminate options, and never evaluates untrusted input with eval or backticks. It uses safe temporary files (mktemp) and avoids predictable filenames in /tmp.

Testing and linting are how you keep scripts correct as they grow. shellcheck catches real bugs (missing quotes, incorrect tests, shadowed variables). shfmt keeps formatting consistent. Test frameworks like bats or shunit2 let you verify behavior. A script that cannot be tested will eventually be replaced.

Deep Dive into the Concept

Portability is not just syntax. It is command behavior. For example, sed -i works differently on GNU and BSD; echo -e is not portable; read -a is Bash-only. A portable script chooses POSIX alternatives (printf instead of echo, sed with explicit temp files, getopts for flags). The right pattern is to build a small portability layer: a few helper functions that normalize differences (e.g., sed_inplace()), and then use those helpers everywhere. This is exactly what your CLI parser and task runner projects will teach you.

Strict mode (set -euo pipefail) is powerful but not magical. set -e does not apply to all contexts (e.g., within if tests or || chains), and pipefail is Bash-specific. A robust script often combines strict mode with explicit checks and a clear error-handling function. For example, you can centralize error reporting, increment error counters, and decide whether to continue or abort based on severity. That is a better model than a simple exit-on-first-error for complex workflows.

Defensive patterns include: validating inputs (case on allowed values), checking dependencies (command -v), requiring configuration (: "${VAR:?missing}"), and refusing to run as root unless required. Another pattern is idempotency: running the script twice should not break the system or duplicate work. Your dotfiles manager, backup tool, and deployment script depend on this.

Tooling is a force multiplier. ShellCheck has a catalog of common errors; using it early will save you days of debugging. The Google Shell Style Guide encourages consistent naming, quoting, and structure; following a style guide makes scripts readable by teams. For complex scripts, include a --dry-run mode and a --verbose mode. These improve user trust and make debugging simpler.

How This Fits on Projects

Every project after the first two depends on robustness. The deployment tool (Project 10) and final platform require safe error handling and logging. The security scanner (Project 13) depends on safe parsing and not running unsafe commands. The test framework (Project 11) is itself an enforcement mechanism for robustness.

Definitions & Key Terms

- Portability: Ability to run across different shells and OSes.

- Idempotency: Running a script multiple times produces the same result.

- Linting: Static analysis that finds bugs without running code.

- Strict mode:

set -euo pipefail(Bash). - Safe temp file: A unique temp file created securely with

mktemp.

Mental Model Diagram

INPUTS -> Validate -> Execute -> Verify -> Cleanup

^ | | |

| v v v

Dependencies Logging Tests Traps

How It Works (Step-by-Step)

- Decide shell target (Bash vs POSIX) and declare in shebang.

- Validate inputs and dependencies early.

- Enable strict mode where appropriate.

- Use logging and clear error handling.

- Add linting and tests to keep behavior stable.

Minimal Concrete Example

#!/usr/bin/env bash

set -euo pipefail

require_cmd() {

command -v "$1" >/dev/null || { echo "missing $1" >&2; exit 1; }

}

require_cmd rsync

: "${BACKUP_DIR:?BACKUP_DIR is required}"

Common Misconceptions

- “Strict mode fixes all bugs.” -> It helps, but you still need explicit checks.

- “Portability is automatic.” -> It is a design choice and requires discipline.

- “Linting is optional.” -> It is the cheapest way to catch real errors.

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- Why is

echo -enot portable? - What does

mktempprotect you against? - When should you not use

set -e? - What does idempotency mean in practice?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

echobehavior varies across shells;printfis consistent.- Predictable filenames and race conditions in

/tmp. - In scripts that must tolerate controlled failures or complex pipelines.

- Running the script twice should not produce duplicate or destructive changes.

Real-World Applications

- Safe deployment scripts

- Cross-platform automation tools

- CI/CD tasks that must be deterministic

Where You Will Apply It

- Project 5: Backup System

- Project 10: Deployment Tool

- Project 11: Test Framework

- Project 13: Security Audit Scanner

- Final Project: DevOps Platform

References

- ShellCheck project and rules: https://www.shellcheck.net/

- Google Shell Style Guide: https://google.github.io/styleguide/shellguide.html

- GNU Coreutils

mktempdocumentation: https://www.gnu.org/software/coreutils/manual/html_node/mktemp-invocation.html

Key Insight

Reliability is designed, not accidental. Robust scripts are predictable because they defend against failure.

Summary

Robustness requires deliberate input validation, predictable behavior, and tooling. If you design for failure, your scripts become trustworthy automation.

Homework / Exercises

- Run ShellCheck on a script and fix all warnings.

- Add a

--dry-runmode to an existing script. - Create a portability checklist for one of your scripts.

Solutions

- Use

shellcheck script.shand address quoting, tests, and unused variables. - Guard destructive commands behind a

DRY_RUNflag that prints instead of executes. - Check for POSIX syntax, portable options, and avoid Bash-only features if using

/bin/sh.

Glossary (High-Signal)

- Builtin: A command implemented by the shell itself (e.g.,

cd,echo). - External command: A program executed via

exec(e.g.,/bin/ls). - Shebang: The

#!line that declares the interpreter. - POSIX shell: The portable subset of shell features defined by POSIX.

- Bash: A popular shell with extensions beyond POSIX.

- IFS: Internal Field Separator, controls word splitting.

- Glob: Filename pattern (

*.log) expanded by the shell. - Trap: A handler function run on signals or exit.

- Subshell: A child shell process with isolated state.

- Here-doc: Multi-line input embedded in a script.

- Here-string: A single string passed to stdin (

<<<in Bash). - Idempotent: Running the script multiple times produces the same result.

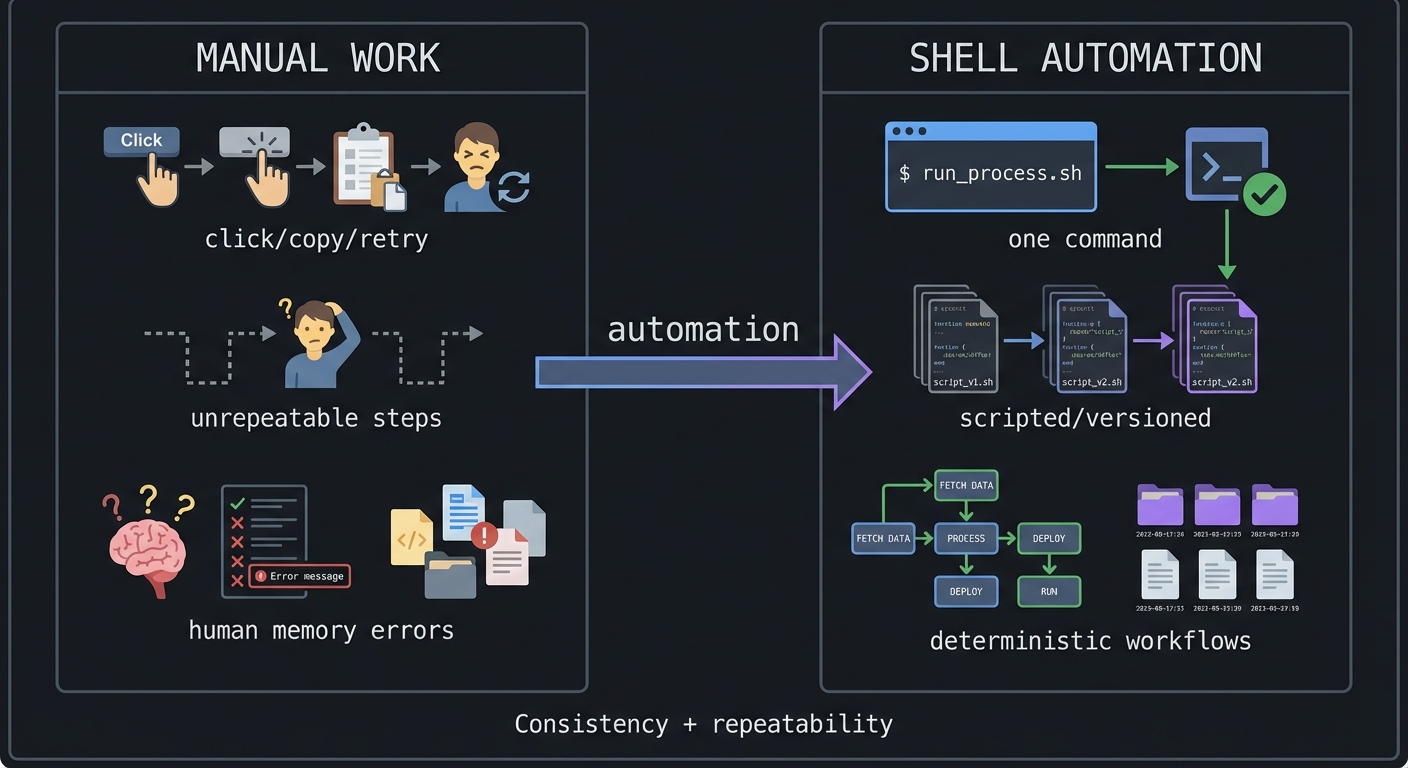

Why Shell Scripting Matters

The Modern Problem It Solves

Modern infrastructure is built on automation. Servers are provisioned, logs are parsed, builds are executed, and deployments are performed by scripts. Even in cloud-native environments, the final control plane often runs shell under the hood. CI/CD systems typically execute build steps in shells, and most container images rely on shell-based entrypoints.

Real-world impact (recent data points):

- Linux dominates web hosting: W3Techs reports Linux as the operating system for roughly 59% of websites (Dec 2025). This means shell scripts run on the majority of web-facing servers. Source: https://w3techs.com/technologies/details/os-linux

- CI defaults to shell: GitHub Actions uses

bashas the default shell on Linux runners. Source: https://docs.github.com/en/actions/using-workflows/workflow-syntax-for-github-actions#defaultsrun - CI runners default to bash: GitLab Runner uses

bashas the default shell on Unix systems. Source: https://docs.gitlab.com/runner/shells/

In short: if you can script, you can automate the infrastructure that powers real systems.

MANUAL WORK SHELL AUTOMATION

----------- -----------------

click, copy, retry one command

unrepeatable steps ---> scripted, versioned

human memory errors deterministic workflows

Context & Evolution (History)

The first Unix shell was created by Ken Thompson at Bell Labs in 1971. The idea was not just to provide a command prompt, but to build a composable programming environment where small tools could be chained together. That design survives because it scales: the shell is still the glue of modern systems.

Concept Summary Table

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize |

|---|---|

| Parsing & Expansion | The shell expands text before execution. Quoting is how you control safety. |

| Streams & Redirection | File descriptors are the plumbing. Understand stdout/stderr and pipes. |

| Control Flow & Exit Status | Success/failure drives logic. Functions return exit codes, not strings. |

| Processes & Signals | Scripts manage processes. Job control and traps make scripts reliable. |

| Robustness & Tooling | Portability, linting, and testing are what make scripts production-grade. |

Project-to-Concept Map

| Project | What It Builds | Primer Chapters It Uses |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Dotfiles Manager | Safe file manipulation + CLI flags | Ch. 1, 3, 5 |

| 2. File Organizer | Globbing, arrays, safe loops | Ch. 1, 3 |

| 3. Log Parser | Pipelines and text transforms | Ch. 1, 2 |

| 4. Git Hooks Framework | Exit codes and control flow | Ch. 3, 5 |

| 5. Backup System | Idempotency and safe I/O | Ch. 2, 5 |

| 6. System Monitor | Process management + streaming | Ch. 2, 4 |

| 7. CLI Parser Library | Argument parsing & functions | Ch. 1, 3 |

| 8. Process Supervisor | Job control + signals | Ch. 4 |

| 9. Network Toolkit | Parallel tasks + pipelines | Ch. 2, 4 |

| 10. Deployment Tool | Robust scripts + rollback | Ch. 3, 5 |

| 11. Test Framework | Exit status + isolation | Ch. 3, 5 |

| 12. Task Runner | DAG execution + concurrency | Ch. 3, 4, 5 |

| 13. Security Scanner | Safe parsing + defensive coding | Ch. 1, 5 |

| 14. Menu System | Input handling + control flow | Ch. 3 |

| 15. Mini Shell | Parsing + execution model | Ch. 1, 2, 4 |

| Final. DevOps Platform | Integration of all concepts | Ch. 1-5 |

Deep Dive Reading by Concept

Parsing & Expansion

| Concept | Book & Chapter | Why This Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Quoting and expansion order | “Effective Shell” by Dave Kerr - Ch. 9-12 | Prevents 90% of shell bugs |

| Parameter expansion | “Learning the Bash Shell” - Ch. 4 | String manipulation without external tools |

| POSIX vs Bash differences | “Shell Programming in Unix, Linux and OS X” - Ch. 2 | Portability decisions |

Streams & Redirection

| Concept | Book & Chapter | Why This Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Redirection basics | “The Linux Command Line” - Ch. 6 | Connect stdin/stdout/stderr correctly |

| Pipes and filters | “How Linux Works” - Ch. 3 | Build composable pipelines |

| Advanced I/O | “The Linux Programming Interface” - Ch. 44 | Pipes and FIFOs for complex workflows |

Control Flow & Exit Status

| Concept | Book & Chapter | Why This Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Exit status semantics | “Bash Idioms” - Ch. 6 | Reliable error handling |

| Functions and scope | “Learning the Bash Shell” - Ch. 6 | Build reusable libraries |

| Case statements | “The Linux Command Line” - Ch. 27 | Clean CLI parsing |

Processes & Signals

| Concept | Book & Chapter | Why This Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Process lifecycle | “Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment” - Ch. 8-9 | Understand fork/exec and job control |

| Signals and traps | “The Linux Programming Interface” - Ch. 20-22 | Safe cleanup and interrupt handling |

| Job control | “Learning the Bash Shell” - Ch. 8 | Parallelization basics |

Robustness & Tooling

| Concept | Book & Chapter | Why This Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Defensive scripting | “Wicked Cool Shell Scripts” - Ch. 1-2 | Safer production scripts |

| Testing shell scripts | “Effective Shell” - Ch. 28 | Build confidence with tests |

| Scripting for ops | “How Linux Works” - Ch. 6 | Real-world system automation |

Quick Start: Your First 48 Hours

Feeling overwhelmed? Start here instead of reading everything:

Day 1 (4 hours):

- Read Chapter 1 (Parsing & Expansion) and Chapter 2 (Streams).

- Watch a 15-minute video on “Bash quoting rules” (any reputable tutorial is fine).

- Start Project 1 (Dotfiles Manager) and get symlink creation working.

- Do not worry about logging or profile switching yet.

Day 2 (4 hours):

- Add error handling and a

statuscommand to Project 1. - Use

shellcheckonce and fix at least 5 warnings. - Read the “Core Question” section of Project 2.

- Build a minimal file organizer that moves

.txtfiles into a folder.

End of Weekend: You can explain quoting, word splitting, and basic redirection. That is 80% of shell scripting.

Recommended Learning Paths

Path 1: The Beginner (Recommended Start)

Best for: New developers or those new to Unix

- Project 1 -> Project 2 -> Project 3

- Project 4 -> Project 11

- Project 5 -> Project 14

Path 2: The DevOps Engineer

Best for: Ops and platform engineers

- Project 5 -> Project 10 -> Project 12

- Project 6 -> Project 8

- Final Project

Path 3: The Systems Deep Dive

Best for: People who want to understand OS internals

- Project 8 -> Project 15

- Project 6 -> Project 9

- Final Project

Path 4: The Security Path

Best for: Security engineers and auditors

- Project 3 -> Project 13

- Project 9 -> Project 10

- Final Project

Success Metrics

By the end of this guide, you should be able to:

- Predict how the shell will expand any given command line

- Build pipelines that correctly separate stdout and stderr

- Write scripts with clear exit codes and consistent error handling

- Implement traps for cleanup and safe termination

- Produce automated tools that are idempotent and safe to run repeatedly

- Run ShellCheck and fix warnings without guesswork

Optional Appendices

Appendix A: Portability Checklist (POSIX vs Bash)

- Decide your target shell and declare it in the shebang.

- Avoid Bash-only syntax (

[[ ]], arrays,${var//}) if using/bin/sh. - Use

printfinstead ofechofor portability. - Avoid

sed -iunless you handle GNU/BSD differences.

Appendix B: Debugging Toolkit

set -xfor tracingPS4='+ ${BASH_SOURCE}:${LINENO}:${FUNCNAME[0]}: 'for rich tracesbash -n script.shfor syntax checksshellcheck script.shfor static analysis

Appendix C: Safety Checklist

- Quote every variable unless you have a proven reason not to.

- Use

--to terminate options (rm -- "$file"). - Validate inputs and refuse to run with missing configuration.

- Use

mktempfor temporary files.

## Project 1: Personal Dotfiles Manager

- File: LEARN_SHELL_SCRIPTING_MASTERY.md

- Main Programming Language: Bash

- Alternative Programming Languages: Zsh, POSIX sh, Fish

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 1: Beginner

- Knowledge Area: File System, Symlinks, Configuration Management

- Software or Tool: GNU Stow alternative

- Main Book: “The Linux Command Line” by William Shotts

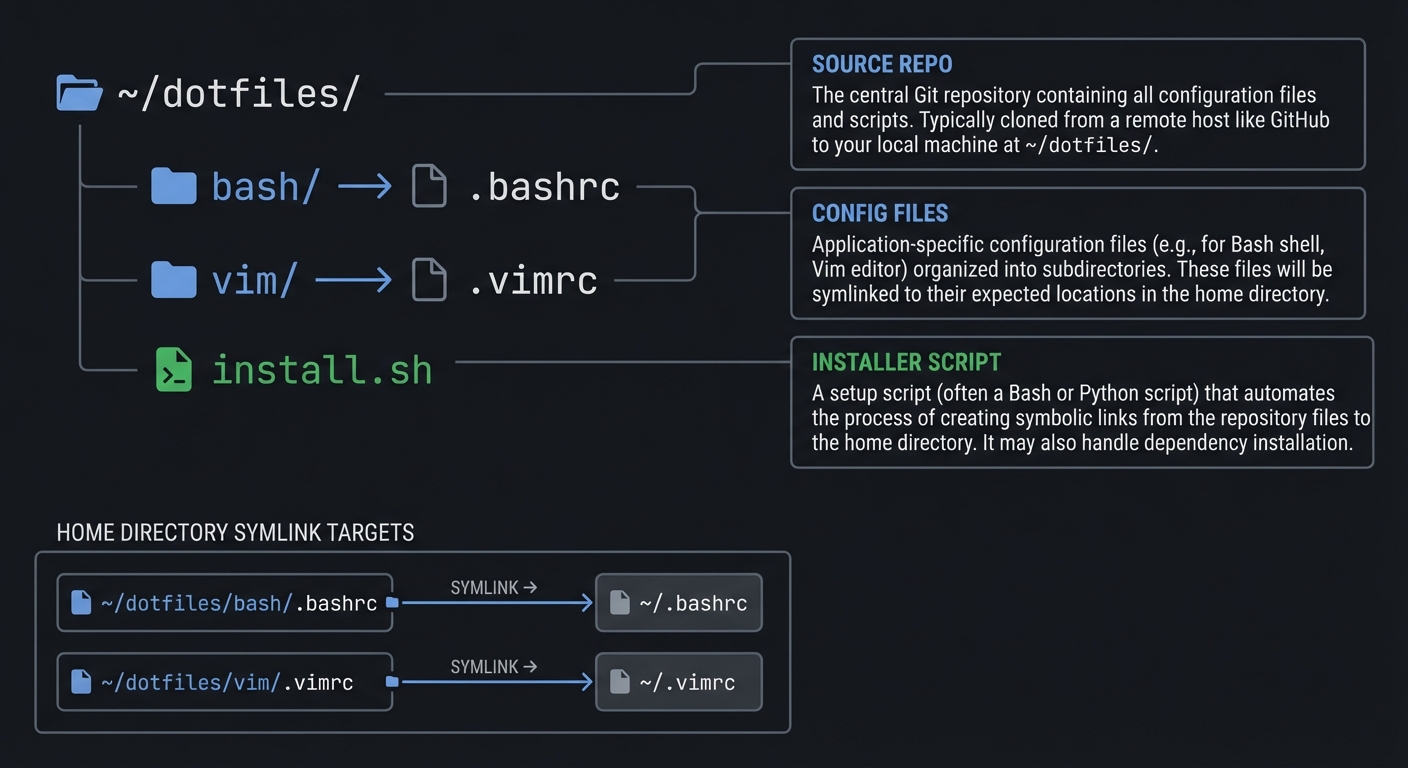

What you’ll build: A script that manages your dotfiles (.bashrc, .vimrc, .gitconfig, etc.) by creating symlinks from a central repository to their expected locations, with backup capabilities and profile switching.

Why it teaches shell scripting: This project forces you to understand paths, symlinks, conditionals, loops, and user interaction—the bread and butter of shell scripting. You’ll handle edge cases (files vs directories, existing configs) and learn defensive programming.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Parsing command-line arguments → maps to positional parameters and getopts

- Creating and managing symlinks → maps to file operations and path handling

- Handling existing files gracefully → maps to conditionals and error handling

- Iterating over files in a directory → maps to loops and globbing

- Providing user feedback → maps to echo, printf, and colors

Key Concepts:

- Symbolic links: “The Linux Command Line” Ch. 4 - William Shotts

- Positional parameters: “Learning the Bash Shell” Ch. 4 - Cameron Newham

- Test operators: “Bash Cookbook” Recipe 6.1 - Carl Albing

- For loops and globbing: “The Linux Command Line” Ch. 27 - William Shotts

Difficulty: Beginner Time estimate: Weekend Prerequisites: Basic command line navigation, understanding of what dotfiles are, familiarity with a text editor

Real World Outcome

You’ll have a command-line tool that you run from your dotfiles git repository. When you set up a new machine or want to apply your configurations:

$ cd ~/dotfiles

$ ./dotfiles.sh install

[dotfiles] Starting installation...

[dotfiles] Backing up existing ~/.bashrc to ~/.bashrc.backup.20241222

[dotfiles] Creating symlink: ~/.bashrc -> ~/dotfiles/bash/.bashrc

[dotfiles] Creating symlink: ~/.vimrc -> ~/dotfiles/vim/.vimrc

[dotfiles] Creating symlink: ~/.gitconfig -> ~/dotfiles/git/.gitconfig

[dotfiles] Skipping ~/.config/nvim (already linked correctly)

[dotfiles] ERROR: ~/.tmux.conf is a directory, skipping

[dotfiles] Installation complete!

4 symlinks created

1 skipped (already correct)

1 error (see above)

1 backup created

$ ./dotfiles.sh status

~/.bashrc -> ~/dotfiles/bash/.bashrc [OK]

~/.vimrc -> ~/dotfiles/vim/.vimrc [OK]

~/.gitconfig -> ~/dotfiles/git/.gitconfig [OK]

~/.tmux.conf -> (not a symlink) [WARN]

$ ./dotfiles.sh uninstall

[dotfiles] Removing symlink ~/.bashrc

[dotfiles] Restoring ~/.bashrc from backup

...

You can also switch between “profiles” (work vs personal):

$ ./dotfiles.sh profile work

[dotfiles] Switching to 'work' profile...

[dotfiles] Updated ~/.gitconfig with work email

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do I write a script that safely modifies the filesystem, handles errors gracefully, and gives clear feedback to the user?”

Before you write any code, sit with this question. Most beginner scripts assume everything will work. Real scripts anticipate what could go wrong: file doesn’t exist, file exists but is a directory, permission denied, disk full. Your dotfiles manager must be SAFE—it should never destroy data.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Symbolic Links vs Hard Links

- What happens when you delete the source of a symlink?

- Can symlinks cross filesystem boundaries?

- How does

ln -sdiffer fromln? - What does

readlinkdo? - Book Reference: “The Linux Command Line” Ch. 4 - William Shotts

- Exit Codes and Error Handling

- What does

$?contain after a command? - What’s the difference between

||and&&? - When should you use

set -e? When is it dangerous? - Book Reference: “Bash Cookbook” Ch. 6 - Carl Albing

- What does

- Path Manipulation

- How do you get the directory containing a script? (

dirname,$0,$BASH_SOURCE) - What’s the difference between

~and$HOME? - How do you resolve a relative path to absolute?

- Book Reference: “Learning the Bash Shell” Ch. 4 - Cameron Newham

- How do you get the directory containing a script? (

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- File Organization

- How will you structure the dotfiles repo? Flat? By category?

- Will you use a manifest file or infer from directory structure?

- How do you handle nested configs like

~/.config/nvim/init.lua?

- Safety

- What happens if the user runs

installtwice? - How do you detect if a file is already correctly linked?

- Should you prompt before overwriting, or use a

--forceflag? - How do you back up existing files?

- What happens if the user runs

- User Experience

- How do you show progress?

- How do you use colors without breaking non-terminal output?

- What information does

statusshow?

Thinking Exercise

Trace the Symlink Resolution

Before coding, trace what happens with this scenario:

~/dotfiles/

├── bash/

│ └── .bashrc

├── vim/

│ └── .vimrc

└── install.sh

Currently on system:

~/.bashrc (regular file, user's old config)

~/.vimrc (symlink -> ~/old-dotfiles/.vimrc)

Questions while tracing:

- When you run

ln -s ~/dotfiles/bash/.bashrc ~/.bashrc, what error do you get? - How do you detect that

~/.vimrcis already a symlink? - How do you detect if it points to the RIGHT location?

- What’s the safest sequence: backup, remove, link? Or check, prompt, then act?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “How would you handle the case where the target path doesn’t exist yet?” (e.g.,

~/.config/doesn’t exist) - “What’s the difference between

[ -L file ]and[ -e file ]?” (hint: broken symlinks) - “How do you make a script work regardless of where it’s called from?”

- “Explain what

${0%/*}does and when you’d use it.” - “How would you make this script idempotent?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start Simple First, make a script that just creates ONE symlink. Get that working, including error handling.

Hint 2: Check Before Acting

Use [[ -e target ]] to check if target exists, [[ -L target ]] to check if it’s a symlink, and readlink target to see where it points.

Hint 3: Safe Backup Pattern

if [[ -e "$target" && ! -L "$target" ]]; then

backup="${target}.backup.$(date +%Y%m%d)"

# Now you can move the file safely

fi

Hint 4: Getting Script Directory

script_dir="$(cd "$(dirname "${BASH_SOURCE[0]}")" && pwd)"

This works even if the script is called via symlink or from another directory.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| File test operators | “The Linux Command Line” by William Shotts | Ch. 27 |

| Symlinks explained | “How Linux Works” by Brian Ward | Ch. 2 |

| Command-line parsing | “Learning the Bash Shell” by Cameron Newham | Ch. 6 |

| Error handling patterns | “Bash Idioms” by Carl Albing | Ch. 6 |

Implementation Hints

Your script structure should follow this pattern:

- Header section: Set strict mode (

set -euo pipefail), define colors, set up paths - Function definitions:

log_info(),log_error(),backup_file(),create_link(),show_usage() - Argument parsing: Handle

install,uninstall,status,--help - Main logic: Loop through dotfiles, call appropriate functions

For the symlink logic, think in terms of states:

- Target doesn’t exist → create link

- Target exists and is correct symlink → skip

- Target exists and is wrong symlink → remove, create correct link

- Target exists and is regular file → backup, create link

- Target exists and is directory → error (or recurse?)

Use exit codes meaningfully: 0 for success, 1 for partial success with warnings, 2 for failure.

Learning milestones:

- Script creates symlinks → You understand

ln -sand path handling - Script handles existing files → You understand conditionals and file tests

- Script provides clear feedback → You understand user-facing scripting

- Script is idempotent (safe to run twice) → You understand defensive programming

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem 1: “Symlink points to the wrong target”

- Why: You resolved paths relative to the current working directory instead of the script location.

- Fix: Use

script_dir="$(cd "$(dirname "${BASH_SOURCE[0]}")" && pwd)"and build absolute paths. - Quick test:

readlink ~/.bashrcshould point into your dotfiles repo.

Problem 2: “Files with spaces break the script”

- Why: Unquoted variables are being split by the shell.

- Fix: Quote every path:

cp -- "$src" "$dst". - Quick test: Add a file named

my configand runstatus.

Problem 3: “Permissions denied when linking”

- Why: You attempted to write into protected directories or ownership is wrong.

- Fix: Run on user-owned paths only; avoid

sudofor dotfiles. - Quick test:

touch ~/.testfileshould succeed.

Problem 4: “Accidentally overwrote existing config”

- Why: Missing backup logic or backup triggered after deletion.

- Fix: Backup before removal and only if target is not already a correct symlink.

- Quick test: Ensure backups are created with timestamped names.

Definition of Done

install,uninstall, andstatuscommands work on a clean system- The script is idempotent (running install twice is safe)

- Existing files are backed up before changes

- Paths with spaces are handled correctly

- Errors are printed to stderr with non-zero exit codes

## Project 2: Smart File Organizer

- File: LEARN_SHELL_SCRIPTING_MASTERY.md

- Main Programming Language: Bash

- Alternative Programming Languages: Zsh, Python (for comparison), POSIX sh

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 2. The “Micro-SaaS / Pro Tool”

- Difficulty: Level 1: Beginner

- Knowledge Area: File System, Pattern Matching, Text Processing

- Software or Tool: File organization automation

- Main Book: “Wicked Cool Shell Scripts” by Dave Taylor

What you’ll build: A script that organizes files in a directory (like Downloads) by automatically sorting them into categorized folders based on file extension, date, size, or custom rules. Supports dry-run mode, undo functionality, and rule configuration.

Why it teaches shell scripting: This project exercises loops, conditionals, associative arrays, pattern matching, and date manipulation. You’ll learn to process files safely, handle edge cases (spaces in filenames!), and create user-friendly CLI tools.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Iterating over files with special characters → maps to proper quoting and globbing

- Extracting file metadata (extension, size, date) → maps to parameter expansion and stat

- Implementing dry-run mode → maps to conditional execution patterns

- Storing undo information → maps to file I/O and data persistence

- Making rules configurable → maps to config file parsing

Key Concepts:

- Parameter expansion for extensions: “Bash Cookbook” Recipe 5.11 - Carl Albing

- Associative arrays: “Learning the Bash Shell” Ch. 6 - Cameron Newham

- File metadata with stat: “The Linux Command Line” Ch. 16 - William Shotts

- Safe filename handling: “Bash Idioms” Ch. 3 - Carl Albing

Difficulty: Beginner Time estimate: Weekend Prerequisites: Project 1 (dotfiles manager), understanding of file extensions, basic loops

Real World Outcome

You’ll have a tool that transforms a messy Downloads folder into organized bliss:

$ ls ~/Downloads/

IMG_2024.jpg report.pdf budget.xlsx video.mp4

setup.exe notes.txt photo.png archive.zip

song.mp3 data.csv document.docx presentation.pptx

$ organize ~/Downloads/ --dry-run

[organize] DRY RUN - no files will be moved

[organize] Analyzing 12 files in /home/douglas/Downloads/

Would move:

IMG_2024.jpg -> Images/IMG_2024.jpg

photo.png -> Images/photo.png

report.pdf -> Documents/report.pdf

document.docx -> Documents/document.docx

presentation.pptx -> Documents/presentation.pptx

budget.xlsx -> Spreadsheets/budget.xlsx

data.csv -> Spreadsheets/data.csv

video.mp4 -> Videos/video.mp4

song.mp3 -> Music/song.mp3

archive.zip -> Archives/archive.zip

setup.exe -> Installers/setup.exe

notes.txt -> Text/notes.txt

Summary: 12 files would be organized into 7 folders

$ organize ~/Downloads/

[organize] Moving IMG_2024.jpg -> Images/

[organize] Moving photo.png -> Images/

[organize] Moving report.pdf -> Documents/

...

[organize] Complete! 12 files organized

[organize] Undo file created: ~/.organize_undo_20241222_143052

$ organize --undo ~/.organize_undo_20241222_143052

[organize] Reverting 12 file moves...

[organize] Undo complete!

$ organize ~/Downloads/ --by-date

[organize] Organizing by modification date...

IMG_2024.jpg -> 2024/12/IMG_2024.jpg

report.pdf -> 2024/11/report.pdf

...

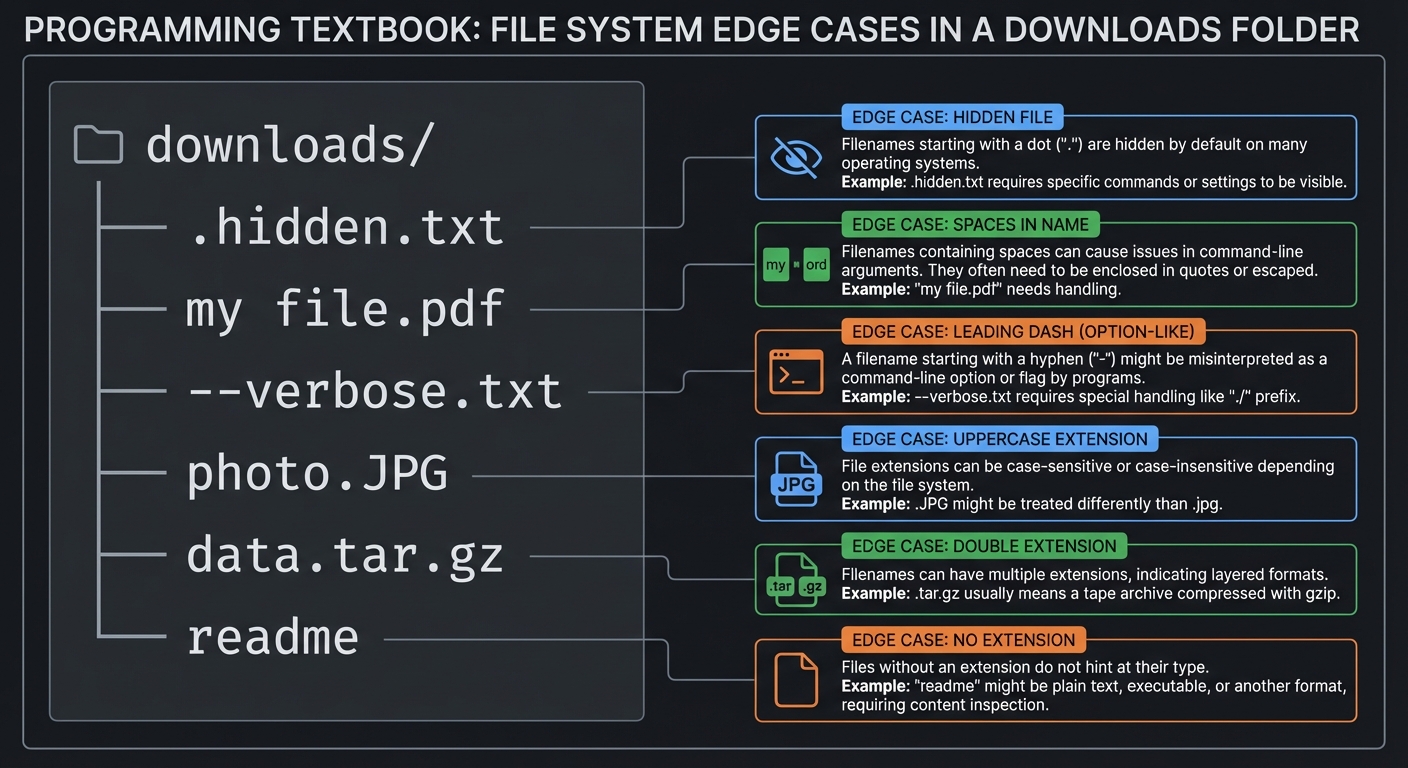

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do I safely process an arbitrary number of files, handling all the edge cases that real-world filesystems throw at me?”

Before coding, understand that filenames can contain: spaces, newlines, quotes, dollar signs, asterisks, leading dashes. Your script must handle ALL of these. This is where most shell scripts fail.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Safe File Iteration

- Why is

for f in $(ls)dangerous? - What’s the correct way to iterate over files?

- How do you handle files starting with

-? - Book Reference: “Bash Cookbook” Recipe 7.4 - Carl Albing

- Why is

- Parameter Expansion for Path Components

- How do you extract just the filename from a path?

- How do you get the extension from

file.tar.gz? - What’s the difference between

${var%.*}and${var%%.*}? - Book Reference: “Learning the Bash Shell” Ch. 4 - Cameron Newham

- Associative Arrays

- How do you declare an associative array in Bash?

- How do you iterate over keys? Values?

- Can you have arrays of arrays in Bash? (Spoiler: no, workarounds exist)

- Book Reference: “Bash Cookbook” Recipe 6.15 - Carl Albing

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Rule System

- How do you map extensions to categories? Hardcoded? Config file?

- What about files with no extension?

- What about case sensitivity (

.JPGvs.jpg)?

- Conflict Resolution

- What if

Images/photo.pngalready exists? - Do you skip, rename (

photo_1.png), or overwrite? - How do you handle the conflict in the undo file?

- What if

- Edge Cases

- What about hidden files (dotfiles)?

- What about directories inside the source folder?

- What about symlinks?

Thinking Exercise

Trace File Processing

Given this directory:

downloads/

├── .hidden.txt

├── my file.pdf

├── --verbose.txt

├── photo.JPG

├── data.tar.gz

└── readme

Questions to trace through:

- What extension should

.hidden.txtbe categorized as? (Hint: it’s a dotfile AND has .txt) - How do you safely

mva file named--verbose.txt? - For

data.tar.gz, do you extract.gzor.tar.gzas the extension? - What do you do with

readme(no extension)?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “Why is

for f in *safer thanfor f in $(ls)?” - “How would you handle filenames containing newlines?”

- “Explain the globbing option

nullgloband when you’d use it.” - “What’s the difference between

${file,,}and${file,,.*}?” - “How would you make this script resume-able if interrupted?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Safe Iteration Pattern

shopt -s nullglob # Empty glob returns nothing, not literal '*'

for file in "$dir"/*; do

[[ -f "$file" ]] || continue # Skip non-files

# process "$file"

done

Hint 2: Extension Extraction

For simple extensions: ext="${file##*.}"

For lowercase: ext="${ext,,}"

Handle no-extension: [[ "$file" == *"."* ]] || ext="noext"

Hint 3: Undo File Format Store moves as tab-separated original and destination:

/path/to/original.pdf /path/to/Documents/original.pdf

Undo by reading and reversing each line.

Hint 4: Dry Run Pattern

do_move() {

if [[ "$DRY_RUN" == true ]]; then

echo "Would move: $1 -> $2"

else

mv -- "$1" "$2"

fi

}

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Safe file handling | “Bash Cookbook” by Carl Albing | Ch. 7 |

| Parameter expansion | “Learning the Bash Shell” by Cameron Newham | Ch. 4 |

| Real-world script examples | “Wicked Cool Shell Scripts” by Dave Taylor | Ch. 1-2 |

| Filename edge cases | “Effective Shell” by Dave Kerr | Ch. 8 |

Implementation Hints

Structure your script with clear separation:

- Configuration: Define extension-to-category mappings using associative arrays

- Core functions:

get_category(),get_target_path(),safe_move(),log_move() - Main loop: Iterate with proper quoting, call functions

- Undo system: Write moves to temp file, provide

--undocommand

Think about extensibility:

- What if someone wants to organize by file size? (small/medium/large)

- What if someone wants custom rules? (e.g., “all files from domain X go to folder Y”)

The key insight: your script should be PREDICTABLE. The --dry-run output should exactly match what organize does without the flag.

Learning milestones:

- Files move to correct folders → You understand extension extraction and moves

- Special filenames handled → You understand quoting and edge cases

- Dry-run matches actual run → You understand clean separation of logic

- Undo works perfectly → You understand data persistence and reversibility

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem 1: “Files disappear or move incorrectly”

- Why: Unquoted globs or unsafe

mvpatterns. - Fix: Use

findor arrays and quote every path. - Quick test: Run in

--dry-runmode and compare output.

Problem 2: “Stat behaves differently on macOS”

- Why: BSD

statuses different flags than GNUstat. - Fix: Implement a portability layer (e.g.,

stat_size()function). - Quick test: Test on both Linux and macOS, or detect OS with

uname.

Problem 3: “Undo does not restore files”

- Why: Missing or corrupt undo log.

- Fix: Write a JSON/TSV log of moves and validate before undo.

- Quick test: Move 3 files, then

undoand verify location.

Problem 4: “Rules misclassify files”

- Why: Extension matching is too naive or case-sensitive.

- Fix: Normalize case and support fallback rules.

- Quick test: Ensure

.JPGfiles are handled the same as.jpg.

Definition of Done

- Organizes a test folder correctly by extension and date

--dry-runprints actions without moving filesundorestores all moved files- Handles filenames with spaces and newlines safely

- Configuration file overrides defaults

## Project 3: Log Parser & Alert System

- File: LEARN_SHELL_SCRIPTING_MASTERY.md

- Main Programming Language: Bash

- Alternative Programming Languages: AWK (embedded), Perl, Python

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 3. The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Text Processing, Pattern Matching, System Administration

- Software or Tool: Log monitoring / Logwatch alternative

- Main Book: “Effective Shell” by Dave Kerr

What you’ll build: A log analysis tool that parses various log formats (syslog, Apache, nginx, application logs), extracts patterns, generates summaries, and sends alerts when error thresholds are exceeded. Supports real-time tailing and historical analysis.

Why it teaches shell scripting: Log processing is the bread-and-butter of shell scripting. You’ll master grep, awk, sed, pipelines, regular expressions, and stream processing. This is where shell scripting SHINES compared to other languages.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Parsing different log formats → maps to regular expressions and awk

- Aggregating data (counts, percentages) → maps to awk and associative arrays

- Real-time processing → maps to tail -f and stream processing

- Sending notifications → maps to integrating external commands

- Handling large files efficiently → maps to streaming vs loading into memory

Key Concepts:

- Regular expressions in grep/awk: “Effective Shell” Ch. 15 - Dave Kerr

- AWK programming: “The AWK Programming Language” - Aho, Kernighan, Weinberger

- Stream processing with pipes: “The Linux Command Line” Ch. 20 - William Shotts

- Tailing and real-time monitoring: “Wicked Cool Shell Scripts” Ch. 4 - Dave Taylor

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 1-2 weeks Prerequisites: Project 2 (file organizer), basic regex understanding, familiarity with log files

Real World Outcome

You’ll have a powerful log analysis tool:

$ logparse /var/log/nginx/access.log --summary

╔══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╗

║ NGINX ACCESS LOG SUMMARY ║

║ /var/log/nginx/access.log ║

║ Period: 2024-12-21 00:00 to 2024-12-22 14:30 ║

╠══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╣

║ Total Requests: 145,832 ║

║ Unique IPs: 12,456 ║

║ Total Bandwidth: 2.3 GB ║

╠══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╣

║ STATUS CODE BREAKDOWN ║

║ ───────────────────────────────────────── ║

║ 200 OK │████████████████████████│ 89.2% (130,123) ║

║ 304 Not Modified │███ │ 5.1% (7,437) ║

║ 404 Not Found │██ │ 3.2% (4,667) ║

║ 500 Server Error │▌ │ 0.8% (1,167) ║

║ Other │▌ │ 1.7% (2,438) ║

╠══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╣

║ TOP 5 REQUESTED PATHS ║

║ ───────────────────────────────────────── ║

║ 1. /api/users 28,432 requests ║

║ 2. /api/products 21,876 requests ║

║ 3. /static/app.js 18,234 requests ║

║ 4. /api/auth/login 12,456 requests ║

║ 5. /images/logo.png 11,234 requests ║

╚══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╝

$ logparse /var/log/syslog --errors --last 1h

[ERROR] 14:23:45 systemd: Failed to start Docker service

[ERROR] 14:23:46 systemd: docker.service: Main process exited, code=exited

[ERROR] 14:25:12 kernel: Out of memory: Kill process 1234 (java)

[WARN] 14:28:33 sshd: Failed password for invalid user admin from 192.168.1.100

Summary: 3 errors, 1 warning in the last hour

$ logparse /var/log/nginx/access.log --watch --alert-on "500|502|503"

[logparse] Watching /var/log/nginx/access.log for patterns: 500|502|503

[logparse] Alert threshold: 10 matches per minute

14:32:15 [ALERT] 500 Internal Server Error - 192.168.1.50 - /api/checkout