Regex: Pattern Mastery - Real World Projects

Goal: Build a deep, engineering-grade understanding of regular expressions: the syntax, the engines that execute them, the performance and security trade-offs, and the real-world applications that make regex a daily tool in systems, security, data, and language tooling. By the end, you will be able to design patterns deliberately (not by trial-and-error), explain why a pattern is correct, and predict when it will be fast or dangerously slow. You will understand how regex relates to finite automata and why some features (like backreferences) change the algorithmic game. The projects culminate in building a regex engine and optimization pipeline from first principles.

Introduction

Regular expressions (regex) are a compact language for describing sets of strings and rules for finding or transforming them. In practice, regex lets you answer questions like: “Does this input match a valid format?”, “Where are the tokens in this file?”, and “How can I extract and transform just the parts I care about?”.

What you will build (by the end of this guide):

- A grep-like pattern matcher and several real-world parsers/validators

- A search-and-replace engine with capture-aware transformations

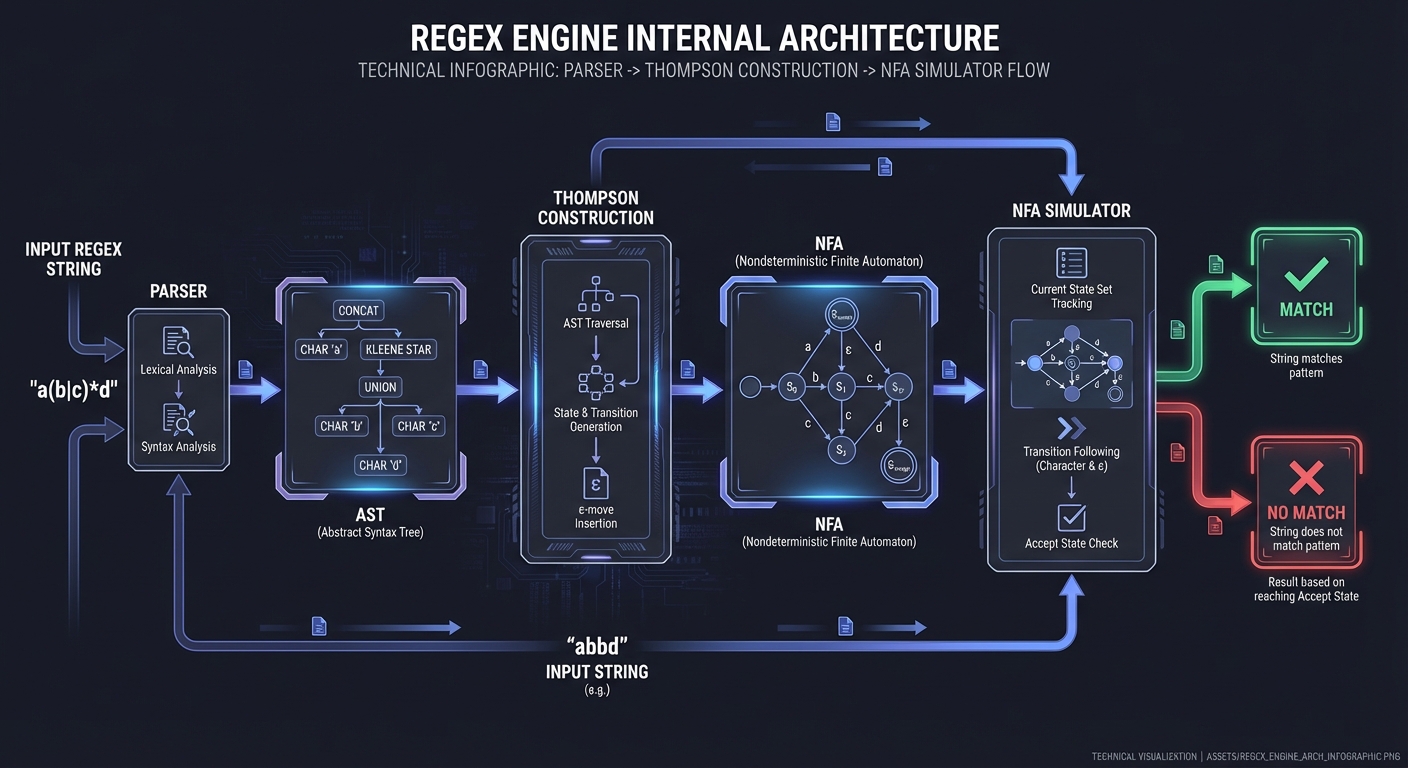

- A tokenizer and a miniature regex engine (NFA/DFA)

- A regex debugger/visualizer and a basic optimizer

Scope (what is included):

- Regex syntax and mental models (literal matching, classes, quantifiers, anchors)

- Engine internals (backtracking vs. Thompson NFA vs. DFA-style matching)

- Performance and security (catastrophic backtracking, ReDoS)

- Practical applications (validation, parsing, tokenization, log processing)

Out of scope (for this guide):

- Full formal proofs of regular language theory

- All vendor-specific regex extensions (we focus on portable concepts)

- GUI-centric tools or IDE-specific regex UIs

The Big Picture (Mental Model)

┌───────────────────────────────┐

│ Pattern │

│ "^(?<user>\w+):\s*(\d+)" │

└───────────────┬───────────────┘

│

v

┌───────────────────────────────┴──────────────────────────────┐

│ Regex Engine Pipeline │

├───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Parse -> AST -> (Optional) Optimize -> NFA/DFA -> Match Loop │

└───────────────────────────────┬───────────────────────────────┘

│

v

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ Match Objects │

│ spans, groups, captures │

└──────────────┬────────────┘

│

v

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ Use in App / Tool / CLI │

└───────────────────────────┘

Key Terms You Will See Everywhere

- Regex flavor: A specific implementation of regex features and semantics (POSIX, PCRE, Python, JavaScript, RE2, etc.).

- Backtracking: A matching strategy that tries alternatives by rewinding input to explore other paths; powerful but can be slow.

- NFA/DFA: Finite automata models used to execute regex efficiently.

How to Use This Guide

- Read the Theory Primer first. It is the “mini-book” that explains the concepts the projects rely on.

- Start with Project 1 to build a minimal matcher. This anchors the mental model.

- Build in layers. Each project adds a new idea (lookarounds, captures, sanitization, parsing, performance).

- Always test patterns with real data. Build a tiny test corpus for each project.

- Use the project checklists. The “Definition of Done” items are your completion criteria.

Prerequisites & Background

Before starting these projects, you should have foundational understanding in these areas:

Essential Prerequisites (Must Have)

Programming Skills:

- Proficiency in one language (Python, JavaScript, Go, or Rust)

- Comfortable with reading files and processing strings

- Basic command-line usage and tool invocation

CS Fundamentals:

- Basic data structures (arrays, stacks, hash maps)

- Big-O notation for understanding performance

- Basic state machines (you should know what “state” and “transition” mean)

Text Processing:

- Strings, encodings, and escaping rules

- Understanding of ASCII vs Unicode at a high level

Helpful But Not Required

Automata Theory:

- Formal definitions of NFA/DFA and regular languages

- Can learn during: Projects 9, 11, 13

Compiler Concepts:

- Tokenization and lexing

- Can learn during: Projects 9 and Project 14 (Capstone)

Self-Assessment Questions

- Can you read a file line by line and process each line in your language of choice?

- Do you understand why a pattern like

\nis different from a literaln? - Can you explain what a “state” and “transition” are in a finite state machine?

- Do you know how to measure the runtime of a function or script?

- Are you comfortable writing a simple CLI program?

If you answered “no” to 1-3, spend 1-2 weeks reviewing basic string processing and CLI projects first.

Development Environment Setup

Required Tools:

- A Unix-like environment (macOS or Linux recommended)

- Python 3.11+ or Node.js 18+ (for the early projects)

- A modern terminal and text editor

Recommended Tools:

ripgrepandjqfor quick test data generationhyperfinefor benchmarking regex performancetime,perf, or similar profiling tools

Testing Your Setup:

$ python3 --version

Python 3.11.9

$ node --version

v20.10.0

$ rg --version

ripgrep 14.1.0

Time Investment

- Simple projects (1-3): Weekend (4-8 hours each)

- Moderate projects (4-8): 1 week (10-20 hours each)

- Complex projects (9-14, including Capstone): 2+ weeks each

- Total sprint: ~2-3 months if completed end-to-end

Important Reality Check

Regex is deceptively simple. The first time through, your patterns will be wrong. That is normal. Mastery comes from understanding why a pattern matches or fails, and how the engine explores alternatives. The projects are structured so that each new feature explains a failure you hit in the previous project.

Big Picture / Mental Model

┌──────────────────────┐

│ Pattern Language │

└─────────┬────────────┘

│ parse

v

┌──────────────────────┐

│ Regex AST (tree) │

└─────────┬────────────┘

│ compile

v

┌──────────────────────┐

│ NFA / DFA / VM code │

└─────────┬────────────┘

│ execute

v

┌──────────────────────┐

│ Match + Captures │

└─────────┬────────────┘

│ integrate

v

┌──────────────────────┐

│ Tools & Products │

└──────────────────────┘

Theory Primer (Read This Before Coding)

This section is the “textbook” for the projects. Each chapter corresponds to a concept cluster that appears throughout the project list.

Chapter 1: Pattern Syntax, Literals, and Escaping

Fundamentals

Regex is a small language with its own syntax rules, and the first mental model you need is that a regex pattern is not the same as a plain string. A pattern is made of literals (characters that match themselves) and metacharacters (characters that change meaning, like . or *). The simplest patterns are literal characters: cat matches the string “cat”. As soon as you introduce metacharacters, you are describing sets of strings rather than one specific string. For example, c.t matches cat, cot, or c7t. Escaping is what keeps your intent precise: \. means “match a literal dot” instead of “any character”. Understanding escaping also requires understanding two layers of interpretation: your programming language string literal rules and the regex engine’s rules. That is why raw strings (r"..." in Python) are so important. If you do not control escaping, you will not control your pattern.

Deep Dive into the Concept

Regex syntax is best understood as a tiny grammar with precedence rules. At the core are atoms (literals, character classes, and grouped subexpressions). Atoms can be concatenated (juxtaposed), alternated (|), and repeated (quantifiers). Precedence matters: repetition binds tighter than concatenation, which binds tighter than alternation. That means ab|cd is (ab)|(cd) and not a(b|c)d. Different regex flavors implement different syntax, but the POSIX definitions are still the foundational mental model: POSIX defines basic (BRE) and extended (ERE) regular expressions, which differ mainly in whether characters like +, ?, |, and grouping parentheses need escaping. This matters when you write portable patterns for tools like sed (BRE) or grep -E (ERE). In many modern regex flavors (PCRE, Python, JavaScript), the syntax is closer to ERE but with many extensions.

The key to writing correct patterns is to recognize how your engine tokenizes the pattern. For example, in most engines, the dot . matches any character except newline, but that changes under a DOTALL/SINGLELINE flag. Similarly, metacharacters like { can either be a quantifier or a literal, depending on whether a valid quantifier follows. Escaping is therefore not cosmetic; it changes the meaning of the language. A good habit is to write regex in verbose mode (where supported) or to build it step-by-step: start with a literal baseline, then add operators one at a time, testing each expansion. The moment you add a metacharacter, re-ask: “Is this supposed to be syntax or a literal?”.

Regex flavor differences also emerge here. POSIX defines specific behavior for word boundaries and character classes, while many modern engines add shorthand like \w or Unicode property classes like \p{L}. RE2, for example, intentionally avoids features that require backtracking (like backreferences and lookarounds) to preserve linear-time guarantees. These flavor differences are not just about syntax; they change which algorithms the engine can use and thus how patterns behave in practice.

Another deep point is token boundary ambiguity. The pattern a{2,3} is a quantifier, but a{2, is a literal { followed by 2, in many engines because the quantifier is invalid. This means a malformed quantifier can silently change semantics rather than throw an error, depending on the flavor. That is why robust tools expose a "strict" mode or validate patterns before use. The safest practice is to test your pattern as a unit (in the exact engine you will use) and to prefer explicit, unambiguous syntax when possible.

Finally, there is a human syntax problem: readability. Most regex bugs are not because the regex is impossible to write, but because it is hard to read and maintain. The solution is to structure patterns: use non-capturing groups to clarify scope, whitespace/comments in verbose mode where available, and staged composition (build your regex from smaller sub-patterns). Treat regex like code. If it is too dense to explain in words, it is too dense to ship.

How This Fits in Projects

You will apply this in Projects 1-6 whenever you translate requirements into regex and need to escape user input correctly.

Definitions & Key Terms

- Literal: A character that matches itself.

- Metacharacter: A character with special meaning in regex syntax (

.,*,+,?,|,(,),[,],{,},^,$). - Escaping: Using

\to force a metacharacter to be treated as a literal. - Regex flavor: A specific implementation’s syntax and behavior.

Mental Model Diagram

pattern string --> lexer --> tokens --> AST

"a\.b" [a][\.][b] (concat a . b)

How It Works (Step-by-Step)

- The engine parses the pattern string into tokens.

- Tokens are grouped into atoms, concatenations, and alternations.

- The parser builds an AST that reflects precedence rules.

- That AST is later compiled into an NFA/DFA or VM bytecode.

Minimal Concrete Example

Pattern: "file\.(txt|md)"

Matches: file.txt, file.md

Rejects: file.csv, filetxt

Common Misconceptions

- “Regex is just a string.” -> It is a language with grammar and precedence.

- “If it works in my editor, it will work everywhere.” -> Flavor differences matter.

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- Why does

a.bmatchaXbbut nota\nb? - What does

\.mean inside a regex pattern? - How does

ab|cddiffer froma(b|c)d?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

.matches any character except newline unless DOTALL is enabled.- It escapes the dot, so it matches a literal

.. ab|cdmatchesaborcd;a(b|c)dmatchesabdoracd.

Real-World Applications

- Building portable CLI tools that support POSIX vs PCRE modes

- Escaping user input before inserting into a regex

Where You Will Apply It

- Project 1: Pattern Matcher CLI

- Project 2: Text Validator Library

- Project 3: Search and Replace Tool

References

- POSIX regex grammar and BRE/ERE rules: https://man.openbsd.org/re_format.7

- Russ Cox, “Regular Expression Matching Can Be Simple And Fast”: https://swtch.com/~rsc/regexp/regexp1.html

- RE2 design notes and syntax (linear-time, no backreferences): https://github.com/google/re2 and https://github.com/google/re2/wiki/Syntax

Key Insight: Regex is a language, not a string. Treat it like a language and you will write correct patterns.

Summary

Escaping and syntax rules are the foundation. Without them, every other concept will fail.

Homework/Exercises

- Convert these literal strings into correct regex literals:

a+b,file?.txt,hello(world). - Write both BRE and ERE versions of the same pattern: “one or more digits”.

Solutions

a\+b,file\?\.txt,hello\(world\)- BRE:

\{1,\}or[0-9]\{1,\}; ERE:[0-9]+

Chapter 2: Character Classes and Unicode

Fundamentals

Character classes are the “vocabulary” of regex. A character class matches one character from a set. The simplest is [abc], which matches a, b, or c. Ranges like [a-z] compress common sets. Negated classes like [^0-9] match anything except digits. In practice, classes are used for validation (is this a digit?), parsing (what starts a token?), and sanitization (what should be stripped). Modern regex engines also provide shorthand classes such as \d, \w, and \s, but those are flavor-dependent: in Unicode-aware engines they match a wider set than ASCII digits or letters. That is why Unicode awareness matters even in “simple” patterns.

Deep Dive into the Concept

The tricky part of character classes is that they are not just lists of characters; they are a bridge between the regex engine and the text encoding model. In ASCII, [a-z] is a straightforward range. In Unicode, ranges can behave unexpectedly if you do not understand collation and normalization. POSIX character classes like [:alpha:] or [:digit:] are defined in terms of locale and can shift meaning based on environment. Meanwhile, Unicode properties such as \p{L} (letters) or \p{Nd} (decimal digits) are explicit and stable across locales but are not universally supported across all regex flavors. A crucial design choice for any regex-heavy system is whether to treat text as bytes or characters. Python, JavaScript, and modern libraries operate on Unicode code points, but some legacy or performance-focused tools still operate on bytes. This changes how \w and . behave.

Unicode is large and evolving. Unicode 17.0 (2025) reports 159,801 graphic+format characters and 297,334 total assigned code points, and the release added 4,803 new characters in a single year. https://www.unicode.org/versions/stats/charcountv17_0.html and https://blog.unicode.org/2025/09/unicode-170-release-announcement.html This means a naive ASCII-only class is insufficient for global input. If you validate a username with [A-Za-z], you are excluding most of the planet. Conversely, using \\w may allow combining marks or scripts you did not intend. Regex designers must decide: do you want strict ASCII, full Unicode letters, or a custom set? This is why production-grade validation often uses explicit Unicode properties rather than shorthand classes.

Character classes also have subtle syntax rules. Inside [], most metacharacters lose their meaning, except for -, ^, ], and \. You must place - at the end or escape it to mean a literal hyphen. A common bug is forgetting that \b means backspace inside [] in some flavors, not word boundary. That is a cross-flavor hazard that breaks patterns when moved between engines.

Unicode also introduces normalization issues. The same user-visible character can be represented by different code point sequences (for example, an accented letter can be a single composed code point or a base letter plus a combining mark). A regex that matches a composed form may fail to match the decomposed form unless you normalize input or explicitly allow combining marks (\p{M}). This is why production-grade systems normalize text before regex validation, or they include combining marks in allowed classes. Without normalization, your regex might appear correct in tests but fail for real-world input from different devices or keyboards.

Case folding is another trap. In ASCII, case-insensitive matching is straightforward. In Unicode, case folding is language-dependent and not always one-to-one (some characters expand to multiple code points). Engines vary in how they implement this. If you depend on case-insensitive matching for international input, you must test with real samples and understand your engine’s Unicode mode. Otherwise, a pattern that seems correct for A-Z can quietly break for non-Latin scripts.

How This Fits in Projects

Classes show up in validation (Project 2), parsing (Project 5), log processing (Project 6), and tokenization (Project 9).

Definitions & Key Terms

- Character class: A set of characters matched by a single position.

- POSIX class:

[:alpha:],[:digit:], etc., often locale-dependent. - Unicode property: A named property such as

\p{L}(letter).

Mental Model Diagram

[Class] -> matches exactly 1 code point

┌──────────────┐

input │ a 9 _ 日 │

└─┬──┬──┬──┬───┘

│ │ │ │

[a-z] \d \w \p{L}

How It Works (Step-by-Step)

- The engine parses the class and builds a set of allowed code points.

- For each input position, it tests membership in that set.

- Negated classes invert the membership test.

Minimal Concrete Example

Pattern: "^[A-Za-z_][A-Za-z0-9_]*$"

Matches: _var, user123

Rejects: 9start, cafe

Common Misconceptions

- “[A-Z] is Unicode uppercase.” -> It is ASCII unless Unicode properties are used.

- “\w always means [A-Za-z0-9_].” -> It varies by flavor and Unicode settings.

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- What does

[^\s]match? - Why is

[A-Z]a poor choice for international names? - How do you include a literal

-inside a class?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- Any non-whitespace character.

- It excludes letters outside ASCII; Unicode names will fail.

- Place it first/last or escape it:

[-a-z]or[a\-z].

Real-World Applications

- Email/URL validation rules

- Token boundaries in programming languages

- Log parsing across multi-locale systems

Where You Will Apply It

- Project 2: Text Validator Library

- Project 5: URL/Email Parser

- Project 9: Tokenizer/Lexer

References

- Unicode character counts (Unicode 17.0): https://www.unicode.org/versions/stats/charcountv17_0.html

- Unicode 17.0 release announcement: https://blog.unicode.org/2025/09/unicode-170-release-announcement.html

- Unicode Standard, Chapter 3 (conformance and properties): https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode17.0.0/core-spec/chapter-3/

- POSIX class syntax and collation rules: https://man.openbsd.org/re_format.7

Key Insight: A character class is a policy decision. It encodes who and what you allow.

Summary

Character classes are where regex meets the real world: encodings, locales, and Unicode.

Homework/Exercises

- Write a pattern that matches only ASCII hex colors.

- Write a Unicode-friendly pattern that matches “letters” and “marks”.

Solutions

^#?[A-Fa-f0-9]{6}$^[\p{L}\p{M}]+$(in engines that support Unicode properties)

Chapter 3: Quantifiers and Repetition (Greedy, Lazy, Possessive)

Fundamentals

Quantifiers let you say “how many times” an atom can repeat. * means zero or more, + means one or more, ? means optional, and {m,n} lets you specify exact ranges. This is the backbone of pattern flexibility. By default, most engines are greedy: they match as much as they can while still allowing the rest of the pattern to match. But sometimes you need lazy behavior (minimal matching) or possessive behavior (no backtracking). Understanding these three modes is a core survival skill.

Deep Dive into the Concept

Quantifiers are a major reason regex can be both powerful and dangerous. Greedy quantifiers (*, +, {m,n}) cause the engine to consume as much input as possible, then backtrack if needed. This is what makes patterns like <.*> match across multiple tags: the .* is greedy and swallows everything. Lazy quantifiers (*?, +?, {m,n}?) invert that behavior: they consume as little as possible and expand only if needed. Possessive quantifiers (*+, ++, {m,n}+) are different: they consume as much as possible and never give it back. This is safer for performance but can cause matches to fail if later parts of the pattern need that input.

In many regex engines (including Python), lazy and possessive quantifiers are implemented as modifiers on the main quantifier. This creates an important mental model: the regex engine is not matching in a purely declarative way; it is executing a search strategy. Greedy means “take as much as you can; backtrack later”. Lazy means “take as little as you can; expand later”. Possessive means “take as much as you can; never backtrack”. These three strategies create different match results even though they describe similar sets of strings.

Quantifiers are also where catastrophic backtracking emerges. Nested quantifiers with overlapping matches ((a+)+, (.*a)*) create many possible paths. Backtracking engines will explore these paths and can take exponential time. This is a real-world security risk (ReDoS) and a major reason some engines (RE2) refuse to implement features like backreferences that require backtracking.

Quantifiers interact with anchors and alternation in non-obvious ways. For example, ^\d+\s+\w+ is efficient because it is anchored and linear. But .*\w at the start of a pattern is almost always a red flag because it forces the engine to attempt matches at many positions. The right mental model is “quantifiers multiply the search space”. If you add them, be sure you also add anchors or context to keep the search constrained.

Another advanced nuance is quantifier stacking and nested groups. A pattern like (\w+\s+)* is deceptively simple but often unstable: the inner \w+\s+ can match the same prefixes in multiple ways, and the outer * multiplies those choices. This ambiguity is exactly what causes exponential behavior in backtracking engines. The fix is to make the repeated unit unambiguous, for example by anchoring it to a delimiter or by using atomic/possessive constructs when supported. If you cannot make it unambiguous, consider switching to a safer engine or redesign the parsing strategy.

Quantifier ranges ({m,n}) are also a trade-off between correctness and performance. A tight range like {3,5} is predictable and efficient; a wide range like {0,10000} can be expensive because it allows huge variation. If you know realistic limits (e.g., username lengths), encode them. This not only improves performance but also improves security by bounding worst-case behavior. Think of ranges as constraints, not just matching convenience.

How This Fits in Projects

Quantifiers are everywhere: validators (Project 2), parsers (Project 5), search/replace (Project 3), and sanitizer (Project 4).

Definitions & Key Terms

- Greedy quantifier: Matches as much as possible, then backtracks.

- Lazy quantifier: Matches as little as possible, then expands.

- Possessive quantifier: Matches as much as possible, no backtracking.

Mental Model Diagram

input: <a> b <c>

pattern: <.*?>

^ ^

lazy expands until '>'

How It Works (Step-by-Step)

- Quantifier consumes input according to its strategy.

- Engine tries to match the rest of the pattern.

- If it fails, greedy/lazy backtrack differently; possessive does not.

Minimal Concrete Example

Pattern: "<.*?>"

Text: "<a> b <c>"

Match: "<a>"

Common Misconceptions

- ”

.*always means the same thing.” -> It depends on context and flags. - “Lazy is always better.” -> Sometimes you need greedy for correctness.

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- What does

a.*bmatch inaXbYb? - Why might

.*at the start of a regex be slow? - When should you use possessive quantifiers?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- Greedy:

aXbYb(whole string). Lazy:aXb. - It forces the engine to explore many backtracking paths.

- When you want to prevent backtracking for performance and the match logic allows it.

Real-World Applications

- Parsing HTML-like tags

- Extracting tokens with flexible lengths

- Avoiding ReDoS in validation patterns

Where You Will Apply It

- Project 3: Search and Replace Tool

- Project 4: Input Sanitizer

- Project 6: Log Parser

References

- Python

redocumentation (greedy/lazy/possessive quantifiers): https://docs.python.org/3/library/re.html - OWASP ReDoS guidance: https://owasp.org/www-community/attacks/Regular_expression_Denial_of_Service_-_ReDoS

Key Insight: Quantifiers are power tools. They can build or destroy performance.

Summary

Quantifiers define repetition and control the engine’s search strategy. Mastering them is essential.

Homework/Exercises

- Write a pattern to match quoted strings without spanning lines.

- Write a pattern that matches 3 to 5 digits, possessively.

Solutions

"[^"\n]*"\d{3,5}+(in engines that support possessive quantifiers)

Chapter 4: Anchors, Boundaries, and Modes

Fundamentals

Anchors match positions, not characters. ^ anchors to the beginning and $ to the end. Word boundaries (\b in many flavors, [[:<:]] and [[:>:]] in POSIX) match the transition between word and non-word characters. Anchors are critical for validation: without them, a pattern can match a substring and still succeed. Modes (flags) like MULTILINE and DOTALL change how anchors and . behave. Understanding these is the difference between “matches any line” and “matches the whole file”.

Deep Dive into the Concept

Anchors define context. Without anchors, the engine can search for a match starting at any position. With anchors, you tell the engine where a match is allowed to begin or end. This is not just a correctness feature; it is a performance feature. Anchoring a pattern to the start of the string reduces the number of candidate positions the engine must consider. This can turn a potentially expensive search into a linear one.

Word boundaries are trickier than they seem. In many engines, \b is defined as the boundary between a word character (\w) and a non-word character. That means its behavior changes if \w is Unicode-aware. In POSIX, word boundaries are defined differently (with [[:<:]] and [[:>:]]), and their behavior depends on locale and definition of “word”. This is a classic portability pitfall. If your regex must be portable across environments, explicit character classes may be safer than word boundaries.

Modes like MULTILINE and DOTALL alter the fundamental semantics of anchors and the dot. In MULTILINE mode, ^ and $ match at line boundaries within a multi-line string; in DOTALL mode, . matches newlines. These flags are powerful but also dangerous: accidentally enabling DOTALL can make .* span huge sections of text, leading to unexpected captures and performance problems. A best practice is to keep patterns local: use explicit \n when you mean newlines, and scope DOTALL to a group if the flavor supports inline modifiers (e.g., (?s:...)).

Anchors also interact with greedy quantifiers. A common performance bug is .* followed by an anchor like $, which can cause the engine to backtrack repeatedly. Anchoring early (^) and using more specific classes reduce this risk. The right mental model is that anchors and boundaries define the search space. Quantifiers explore within that space. Use anchors to make the search space as small as possible.

Another nuance is the difference between string anchors and line anchors. Some flavors provide explicit anchors for the absolute start and end of the string (e.g., \A and \Z), which are unaffected by multiline mode. This becomes important when you embed regex inside tools where the input might include newlines and you still want to match the entire string. If your engine supports these, use them when you mean "absolute start/end" to avoid surprises caused by multiline mode.

Boundaries also differ in locale-sensitive environments. POSIX word boundaries are defined in terms of character classes and locale-specific definitions of word characters. That means a regex written for one locale might behave differently in another. If you need portability, define explicit word character classes instead of relying on locale-sensitive boundaries.

How This Fits in Projects

Anchors are used in validation (Project 2), parsing structured data (Project 5), and log processing (Project 6).

Definitions & Key Terms

- Anchor: A zero-width assertion for positions (

^,$). - Boundary: A position between categories of characters (word vs non-word).

- Mode/Flag: Engine setting that changes behavior (MULTILINE, DOTALL).

Mental Model Diagram

line: "error: disk full"

^ $

MULTILINE:

^ matches after every \n, $ before every \n

How It Works (Step-by-Step)

- Engine checks whether current position satisfies anchor/boundary.

- If yes, it continues; if not, it fails at that position.

- Modes change what qualifies as “start” or “end”.

Minimal Concrete Example

Pattern: "^ERROR:"

Text: "INFO\nERROR: disk full"

Match: only if MULTILINE is enabled

Common Misconceptions

- ”^ always means start of string.” -> Not in multiline mode.

- “\b matches word boundaries in all languages equally.” -> It depends on \w and Unicode.

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- Why is

^\w+$a safe validation pattern? - What happens to

$in MULTILINE mode? - How does DOTALL change

.?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- It anchors the entire string so only full matches pass.

- It matches before newlines as well as end of string.

- It allows

.to match newline characters.

Real-World Applications

- Validating fields (usernames, IDs)

- Anchoring log parsers to line boundaries

Where You Will Apply It

- Project 2: Text Validator Library

- Project 6: Log Parser

- Project 10: Template Engine

References

- Python

redocs (anchor behavior, DOTALL, MULTILINE): https://docs.python.org/3/library/re.html - POSIX word boundary syntax: https://man.openbsd.org/re_format.7

Key Insight: Anchors do not match characters, they match positions. Use them to shrink the search space.

Summary

Anchors and boundaries define context, correctness, and performance.

Homework/Exercises

- Write a regex that matches a line starting with “WARN”.

- Write a regex that matches exactly one word (no spaces), across Unicode.

Solutions

^WARN(with MULTILINE if needed)^\p{L}+$(Unicode property-enabled engines)

Chapter 5: Grouping, Alternation, Captures, and Backreferences

Fundamentals

Grouping controls precedence, alternation selects between choices, and captures remember matched text. Parentheses (...) create groups; alternation | lets you say “this or that”. Capturing groups are useful because they let you reuse parts of the match later (in replacements or backreferences). But they also affect performance and clarity: groups that you do not need should be non-capturing ((?:...)) when supported.

Deep Dive into the Concept

Alternation is one of the most subtle performance traps in regex. The engine tries alternatives in order. If the first alternative is ambiguous or too broad, the engine will spend time exploring it before falling back to the second. This means that ordering matters: put the most specific alternatives first when using backtracking engines. A common optimization is prefix factoring: cat|car|cap becomes ca(?:t|r|p) which avoids re-evaluating the prefix.

Grouping also controls scope for quantifiers and anchors. (ab)* means repeat the group, while ab* means repeat only b. This is not just syntax; it changes the automaton. Capturing groups assign numbers based on their opening parenthesis, and those numbers are used in backreferences (\1, \2). Backreferences allow matching the same text that was previously captured. This breaks the regular-language model and forces backtracking engines to keep track of matched substrings. That is why RE2 and DFA-based engines do not support backreferences: they cannot be implemented with a pure automaton. The cost is expressive power; the benefit is linear-time guarantees.

Captures also power replacement. When you perform a substitution, you often reference groups by number or name (e.g., $1 or \g<name>). This is the basis of real-world text transformations. It is also a source of bugs: forgetting to escape $ or \ in replacement strings can create subtle errors. A best practice is to name your groups for clarity and to avoid numbering errors as patterns evolve.

Grouping interacts with quantifiers in subtle ways. For example, (ab)+ captures only the last iteration in many engines, not all iterations. If you need all iterations, you must collect matches using findall() or repeated matching instead of relying on a single capture group. This is a common misunderstanding that leads to data loss in extraction tools. Another common issue is catastrophic backtracking in alternations, especially when one alternative is a prefix of another (e.g., abc|ab). The engine will try abc, fail at c, then backtrack to try ab, potentially multiplying work across large inputs. Reordering or factoring alternatives fixes this.

Finally, group naming conventions matter in large regexes. If you build a template engine or parser, named groups become your API contract: they define the fields your code expects. Choose stable names and avoid renumbering. This makes refactoring safe and lowers the risk of silent bugs when the regex changes.

How This Fits in Projects

Captures and alternation are used in Projects 3, 5, 7, and 10, where you extract and reorganize text.

Definitions & Key Terms

- Capturing group: A parenthesized subexpression whose match is stored.

- Non-capturing group:

(?:...), used for grouping without storage. - Backreference: A reference to previously captured text (

\1).

Mental Model Diagram

Pattern: (user|admin):(\d+)

Groups: 1=user|admin, 2=digits

Match: admin:42

How It Works (Step-by-Step)

- The engine explores alternatives left-to-right.

- Each time a capturing group matches, its span is stored.

- Backreferences force later parts of the pattern to equal stored text.

Minimal Concrete Example

Pattern: "^(\w+)-(\1)$"

Matches: "abc-abc"

Rejects: "abc-def"

Common Misconceptions

- “Grouping always captures.” -> Not if you use non-capturing groups.

- “Alternation order doesn’t matter.” -> It matters in backtracking engines.

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- Why does

ab|abehave differently thana|ab? - What is a backreference and why is it expensive?

- When should you prefer

(?:...)?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- The engine tries left-to-right; first match wins.

- It forces the engine to compare with previous captures, breaking pure NFA/DFA matching.

- When you need grouping but not the captured text.

Real-World Applications

- Parsing key/value pairs

- Extracting tokens with labeled fields

- Template rendering with captures

Where You Will Apply It

- Project 3: Search and Replace Tool

- Project 5: URL/Email Parser

- Project 10: Template Engine

References

- RE2 documentation on unsupported backreferences: https://github.com/google/re2

- POSIX re_format notes on capturing groups: https://man.openbsd.org/re_format.7

Key Insight: Grouping controls structure; capturing controls memory. Use both deliberately.

Summary

Groups and alternation create structure and reuse. They are essential for real extraction tasks.

Homework/Exercises

- Write a regex that matches repeated words: “hello hello”.

- Convert

(foo|bar|baz)into a factored form.

Solutions

^(\w+)\s+\1$ba(?:r|z)|fooor(?:foo|ba(?:r|z))

Chapter 6: Lookarounds and Zero-Width Assertions

Fundamentals

Lookarounds are assertions that check context without consuming characters. Positive lookahead (?=...) requires that the following text matches; negative lookahead (?!...) requires it not to match. Lookbehind variants apply to text before the current position. These are powerful for constraints like “match a number only if followed by a percent sign” without including the percent sign in the match.

Deep Dive into the Concept

Lookarounds extend regex expressiveness without consuming input. That makes them ideal for validation and extraction tasks that require context. For example, \d+(?=%) matches the digits in 25% but not the percent sign. Negative lookahead lets you exclude patterns: ^(?!.*password).* rejects strings containing “password”. Lookbehind is even more precise for context, but it is not universally supported or has restrictions (fixed-length vs variable-length) depending on the engine. That means portability is a concern: a pattern that works in Python may fail in JavaScript or older PCRE versions.

From an engine perspective, lookarounds often require additional scanning. Many engines treat lookahead as a branch that is evaluated at the current position without advancing. In backtracking engines, that can be implemented naturally. In DFA-style engines, lookarounds are harder because they break the one-pass model. This is one reason RE2 does not support lookaround at all. In PCRE2, the alternative DFA-style matcher can handle some constructs but still has limitations around capturing and lookaround handling.

Lookarounds can also hide performance issues. A common trap is to use lookahead with .* inside, which can cause the engine to scan the remainder of the string repeatedly. You should treat lookarounds as advanced tools: use them sparingly, and prefer explicit parsing when possible.

There is also a portability dimension: some engines only allow fixed-length lookbehind, while others permit variable-length lookbehind with constraints. That means a pattern like (?<=\\w+) may compile in one engine and fail in another. When portability matters, avoid lookbehind entirely or constrain it to fixed-length tokens. If you must support multiple environments, document the supported subset and provide fallback patterns that avoid lookbehind.

Lookarounds can also be replaced with capture + post-processing. For example, instead of (?<=\\$)\\d+, you can capture \\$(\\d+) and then use the captured group in your application logic. This is often more portable and easier to debug, and it avoids hidden performance costs in complex lookarounds.

How This Fits in Projects

Lookarounds appear in sanitization (Project 4), URL parsing (Project 5), markdown parsing (Project 7), and template engines (Project 10).

Definitions & Key Terms

- Lookahead: Assertion about what follows the current position.

- Lookbehind: Assertion about what precedes the current position.

- Zero-width: Does not consume characters.

Mental Model Diagram

text: "$100.00"

regex: (?<=\$)\d+(?=\.)

match: 100

How It Works (Step-by-Step)

- Engine arrives at a position.

- Lookaround runs its subpattern without consuming input.

- If the assertion passes, the main match continues.

Minimal Concrete Example

Pattern: "\b\w+(?=\.)"

Text: "end." -> match "end"

Common Misconceptions

- “Lookarounds are always zero-cost.” -> They can be expensive.

- “All engines support lookbehind.” -> Many do not or restrict it.

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- What does

(?=abc)do at a position? - Why does RE2 not support lookarounds?

- How can lookarounds cause repeated scanning?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- It asserts that

abcfollows without consuming it. - They are not implementable with linear-time guarantees in RE2’s design.

- The engine may re-check the same prefix/suffix multiple times.

Real-World Applications

- Enforcing password policies

- Extracting substrings with context

Where You Will Apply It

- Project 4: Input Sanitizer

- Project 5: URL/Email Parser

- Project 7: Markdown Parser

References

- RE2 design notes (no lookaround for linear-time guarantee): https://github.com/google/re2

- RE2 syntax reference: https://github.com/google/re2/wiki/Syntax

- ECMAScript lookbehind support notes (MDN): https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Regular_expressions/Lookbehind_assertion

- PCRE2 matching documentation: https://www.pcre.org/current/doc/html/pcre2matching.html

Key Insight: Lookarounds are context checks. They are powerful but not universally supported.

Summary

Lookarounds allow you to express context without consumption but carry performance and portability risks.

Homework/Exercises

- Match numbers that are followed by “ms” without capturing “ms”.

- Match “error” only if it is not preceded by “ignore-“.

Solutions

\d+(?=ms)(?<!ignore-)error(if lookbehind is supported)

Chapter 7: Substitution, Replacement, and Match Objects

Fundamentals

Matching is only half of regex. The other half is transformation: using captured groups to rewrite text. Most engines provide a substitution operation (e.g., s/regex/repl/ or re.sub()) where you can reference groups in the replacement string. Understanding match objects (start, end, groups) lets you build tools like search-and-replace, refactoring scripts, and data extractors.

Deep Dive into the Concept

Substitution is where regex becomes a “text transformation language.” Capturing groups define what you want to keep, and the replacement string defines how to rearrange it. For example, converting YYYY-MM-DD into DD/MM/YYYY is a simple capture reorder. But real-world substitutions require more: conditional logic, case normalization, escaping special characters, and ensuring that replacements do not accidentally re-trigger patterns.

Match objects provide detailed metadata about a match: the span (start/end), groups, group names, and the original input. These details are critical when building tools that annotate or highlight matches. For example, a grep-like CLI can highlight matches by slicing the string using match.start() and match.end(). A parser can build structured objects from named groups. A refactoring tool can record match positions and apply replacements in reverse order to avoid shifting offsets.

Substitution also interacts with regex engine features like global matching and overlapping matches. Some engines treat replacements as non-overlapping: once a match is replaced, the engine continues after that match. Others allow overlapping matches through advanced APIs. This affects how you implement repeated substitutions. A safe approach is to iterate matches explicitly and build the output string manually, especially when you need custom logic.

Replacement strings introduce another layer of escaping. $1 or \1 means “insert group 1”, but a literal $ might need to be escaped. This is where bugs often happen. In production code, it is safer to use replacement functions (callbacks) rather than raw strings, because the function receives a match object and returns the intended replacement directly.

Substitution pipelines also require careful attention to order of operations. If you apply multiple regex replacements sequentially, earlier replacements can affect later patterns (either by changing the text or by introducing new matches). This is not necessarily wrong, but it must be intentional. A robust design documents the pipeline order, includes tests for order-dependent cases, and provides a dry-run mode that shows diffs so users can review changes before applying them.

Finally, consider streaming replacements for large files. Many simple implementations read the entire file into memory, apply replacements, and write out the result. For multi-gigabyte logs, this is not viable. The correct approach is to stream line-by-line or chunk-by-chunk, but that introduces edge cases where matches may span chunk boundaries. If you need streaming, either design patterns that are line-local or implement a rolling buffer with overlap.

How This Fits in Projects

This chapter powers Projects 3, 8, 10, and 12, where match objects and substitutions are core features.

Definitions & Key Terms

- Match object: A data structure representing one match (span + groups).

- Replacement string: Output text that can reference capture groups.

- Global match: Find all matches, not just the first.

Mental Model Diagram

input: 2024-12-25

pattern: (\d{4})-(\d{2})-(\d{2})

repl: $3/$2/$1

output: 25/12/2024

How It Works (Step-by-Step)

- Engine finds a match and records group spans.

- Replacement engine substitutes group references into output.

- Output is assembled, often by concatenating segments.

Minimal Concrete Example

Pattern: "(\w+),(\w+)"

Replace: "$2 $1"

Text: "Doe,John" -> "John Doe"

Common Misconceptions

- “Replacement is just string concatenation.” -> It depends on group references and escaping.

- “Matches are always non-overlapping.” -> Some APIs allow overlap.

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- Why is a callback replacement safer than a raw replacement string?

- What happens if your replacement inserts text that matches the pattern?

- How do you highlight matches in a CLI?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- It avoids escaping pitfalls and gives you full control via the match object.

- It may cause repeated replacements unless you control iteration.

- Use match spans to inject color codes before/after the match.

Real-World Applications

- Data cleaning and normalization

- Refactoring code (rename variables, reorder fields)

- Building extraction pipelines

Where You Will Apply It

- Project 3: Search and Replace Tool

- Project 8: Data Extractor

- Project 12: Regex Debugger & Visualizer

References

- Python

redocumentation (match objects, replacement syntax): https://docs.python.org/3/library/re.html

Key Insight: Substitution turns regex from a checker into a transformer.

Summary

Match objects and substitutions are essential for building tools, not just validators.

Homework/Exercises

- Replace all dates

YYYY-MM-DDwithMM/DD/YYYY. - Convert

LAST, FirstintoFirst Lastwith a single regex.

Solutions

(\d{4})-(\d{2})-(\d{2})->$2/$3/$1^\s*(\w+),\s*(\w+)\s*$->$2 $1

Chapter 8: Regex Engines, Automata, and Performance

Fundamentals

Regex engines are not all the same. Some are backtracking engines (Perl, PCRE, Python), while others are automata-based (Thompson NFA, DFA, RE2). Backtracking engines are flexible and support advanced features (like backreferences), but they can be slow in the worst case. Automata-based engines provide linear-time guarantees but often restrict features. Understanding this trade-off is the key to writing safe and fast regex.

Deep Dive into the Concept

The canonical automata model for regex is the NFA, which can be constructed from a regex using Thompson’s construction. An NFA can be simulated in two ways: naive backtracking (try one path, then backtrack) or parallel simulation (track all possible states at once). Russ Cox’s classic analysis shows that backtracking can explode exponentially for certain patterns, while Thompson NFA simulation runs in time proportional to input length. This is the theoretical basis for why some regex engines are “fast” and others are vulnerable to catastrophic backtracking.

PCRE2 documents this explicitly: its standard algorithm is depth-first NFA (backtracking) and its alternative algorithm is a DFA-like breadth-first approach that scans input once. The backtracking approach is fast in the common case and supports captures, but it can be exponential in the worst case. The DFA-like approach avoids backtracking but sacrifices features like backreferences and capturing. This trade-off appears across regex engines.

RE2 takes a strong stance: it guarantees linear-time matching by refusing to implement features that require backtracking, such as backreferences and lookarounds. This makes it suitable for untrusted input and high-scale environments. The cost is reduced expressiveness. If your use case requires backreferences or variable-length lookbehind, you will not be able to use RE2.

From a security perspective, backtracking engines can be exploited with ReDoS (Regular expression Denial of Service). OWASP documents how certain patterns (nested quantifiers with overlap) can take exponential time when fed crafted input. This means regex is not just about correctness; it is about security. A safe regex design includes: anchoring patterns, avoiding nested ambiguous quantifiers, and using engine-specific safety features like timeouts.

The practical takeaway is that engine internals must be part of your design process. Choose an engine appropriate for your risk profile. If regex is user-supplied or used on large untrusted inputs, prefer linear-time engines. If you need advanced features and have controlled input, backtracking engines may be acceptable but must be hardened.

Modern engines also use hybrid techniques. Some start with a fast pre-scan using literal prefixes (Boyer-Moore style), then fall back to full regex matching only when a candidate position is found. Others compile regex into a small virtual machine, which can be JIT-compiled for speed. These optimizations matter in high-throughput systems: when you run millions of regexes per second, even a small constant factor becomes significant. This is why real-world engines often include a literal "prefilter" step that finds likely matches before running the full engine.

From a tooling perspective, the internal representation (AST -> NFA -> DFA) is also where optimization opportunities arise. You can detect that a regex is a literal string and bypass the engine entirely. You can factor alternations into tries, or transform patterns to reduce backtracking. These optimizations are not just academic; they are required for production-grade engines and are the heart of the regex optimizer project in this guide.

How This Fits in Projects

This chapter is the foundation for Projects 9, 11, 12, 13, and Project 14 (Capstone).

Definitions & Key Terms

- Backtracking engine: Tries alternatives sequentially, may be exponential.

- Thompson NFA: An efficient NFA simulation approach.

- DFA-style matcher: Tracks multiple states in parallel for linear-time matching.

- ReDoS: Regex Denial of Service via catastrophic backtracking.

Mental Model Diagram

Regex -> NFA ->

backtracking: explore one path, rewind, try next

Thompson NFA: keep a set of states, advance all at once

How It Works (Step-by-Step)

- Regex is compiled into an NFA.

- Engine either backtracks or simulates multiple states.

- Backtracking explores exponential paths; NFA simulation stays linear.

Minimal Concrete Example

Pattern: "^(a+)+$"

Input: "aaaaX"

Result: catastrophic backtracking in many engines

Common Misconceptions

- “All regex engines are equivalent.” -> Engine choice changes performance and safety.

- “Backtracking only affects rare cases.” -> Attackers exploit those cases.

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

- Why does RE2 not support backreferences?

- What is the difference between backtracking NFA and Thompson NFA simulation?

- What makes

(a+)+dangerous?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- Backreferences require backtracking and break linear-time guarantees.

- Backtracking tries one path at a time; Thompson NFA tracks all possible states.

- Nested quantifiers create many overlapping paths, leading to exponential backtracking.

Real-World Applications

- Safe regex processing at scale (logs, security filters)

- Engine selection in production systems

Where You Will Apply It

- Project 9: Tokenizer/Lexer

- Project 11: Regex Engine

- Project 13: Regex Optimizer

- Project 14: Full Regex Suite (Capstone)

References

- Russ Cox: “Regular Expression Matching Can Be Simple And Fast” https://swtch.com/~rsc/regexp/regexp1.html

- PCRE2 matching documentation (standard vs DFA algorithm): https://www.pcre.org/current/doc/html/pcre2matching.html

- RE2 README (linear-time guarantee, unsupported features): https://github.com/google/re2

- OWASP ReDoS documentation: https://owasp.org/www-community/attacks/Regular_expression_Denial_of_Service_-_ReDoS

Key Insight: Regex is only as safe as the engine that runs it.

Summary

Regex performance is about algorithm choice. Backtracking is powerful but risky; automata are safe but limited.

Homework/Exercises

- Identify a regex that can cause catastrophic backtracking.

- Rewrite it into a safer version using atomic/possessive constructs if supported.

Solutions

(a+)+$is a classic ReDoS pattern.(?>a+)+$ora++$in engines that support atomic/possessive constructs.

Glossary

High-Signal Terms

- Anchor: A zero-width assertion that matches a position, not a character.

- Backtracking: Engine strategy that tries alternative paths by rewinding input.

- Backreference: A feature that matches the same text captured earlier (breaks regular-language guarantees).

- BRE/ERE (POSIX): Basic/Extended Regular Expression flavors with different escaping rules for operators like

+and|. - Catastrophic Backtracking: Exponential-time matching caused by nested/overlapping quantifiers.

- Capture Group: Parenthesized part of a regex whose match is stored.

- DFA (Deterministic Finite Automaton): Automaton with one transition per symbol per state.

- Leftmost-Longest: POSIX rule that prefers the earliest, then longest, match.

- Lookaround: Zero-width assertion that checks context without consuming input.

- NFA (Nondeterministic Finite Automaton): Automaton that can have multiple transitions per symbol.

- Regex Flavor: The syntax/semantics of a particular regex implementation.

- ReDoS: Denial of service caused by catastrophic backtracking.

- Thompson NFA: Classic linear-time NFA construction and simulation approach.

- Unicode Property Class: Character class based on Unicode properties (e.g.,

\\p{L}for letters). - Quantifier: Operator that repeats an atom (

*,+,{m,n}).

Why Regular Expressions Matter

The Modern Problem It Solves

Modern software is flooded with text: logs, configs, markup, API responses, and user input. Regex is the universal tool for quickly identifying and transforming patterns in this text. It powers search, validation, tokenization, and data extraction across every layer of software.

Real-world impact with current statistics:

- Unicode scale (2025): Unicode 17.0 reports 159,801 graphic+format characters and 297,334 total assigned code points. Regex engines must handle far more than ASCII. https://www.unicode.org/versions/stats/charcountv17_0.html

- Unicode growth: The Unicode Consortium’s 17.0 announcement notes 4,803 new characters added in 2025, reinforcing why Unicode-aware classes (

\p{L},\p{Nd}) matter. https://blog.unicode.org/2025/09/unicode-170-release-announcement.html - Security impact: OWASP defines ReDoS as a denial-of-service attack caused by regex patterns that can take extremely long (often exponential) time on crafted inputs. https://owasp.org/www-community/attacks/Regular_expression_Denial_of_Service_-_ReDoS

- Markdown ambiguity: CommonMark exists because Markdown implementations diverged without a strict spec, and it lists broad adoption across major platforms (GitHub, GitLab, Reddit, Stack Overflow). https://commonmark.org/

OLD APPROACH NEW APPROACH

┌───────────────────────┐ ┌──────────────────────────┐

│ Manual parsing │ │ Regex-driven pipelines │

│ Dozens of if/else │ │ Compact patterns + tests │

└───────────────────────┘ └──────────────────────────┘

Context & Evolution (Brief)

Regex began as a theoretical model (Kleene) and became practical through tools like grep and sed. Today, regex engines range from backtracking implementations (Perl/PCRE/Python) to safe automata-based engines (RE2), reflecting the trade-off between expressiveness and performance.

Concept Summary Table

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize |

|---|---|

| Pattern Syntax & Escaping | Regex is a language; precedence and escaping define meaning. |

| Character Classes & Unicode | Classes encode policy; Unicode makes ASCII-only patterns unsafe. |

| Quantifiers & Repetition | Greedy/lazy/possessive quantifiers control search and performance. |

| Anchors & Boundaries | Anchors define positions and shrink the search space. |

| Grouping & Captures | Grouping creates structure; captures store text; alternation order matters. |

| Lookarounds | Context checks without consuming input; not universally supported. |

| Substitution & Match Objects | Transformations require capture-aware replacements and spans. |

| Engine Internals & Performance | Backtracking vs automata determines correctness, speed, and security. |

Project-to-Concept Map

| Project | What It Builds | Primer Chapters It Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Project 1: Pattern Matcher CLI | Basic grep-like matcher | 1, 3, 4, 7 |

| Project 2: Text Validator Library | Validation patterns | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| Project 3: Search and Replace Tool | Capture-aware substitutions | 1, 3, 5, 7 |

| Project 4: Input Sanitizer | Security-focused filtering | 2, 3, 6, 8 |

| Project 5: URL/Email Parser | Structured extraction | 2, 3, 5, 6 |

| Project 6: Log Parser | Anchored parsing | 2, 4, 7 |

| Project 7: Markdown Parser | Nested parsing | 5, 6, 7 |

| Project 8: Data Extractor | Bulk extraction and transforms | 2, 7 |

| Project 9: Tokenizer/Lexer | Formal tokenization | 2, 8 |

| Project 10: Template Engine | Substitution + context | 5, 7 |

| Project 11: Regex Engine | NFA-based matcher | 1, 8 |

| Project 12: Regex Debugger | Visualization and tracing | 7, 8 |

| Project 13: Regex Optimizer | Automata transforms | 8 |

| Project 14: Full Regex Suite (Capstone) | Full engine + tools | 1-8 |

Deep Dive Reading by Concept

Fundamentals & Syntax

| Concept | Book & Chapter | Why This Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Regex syntax basics | Mastering Regular Expressions (Friedl) Ch. 1-2 | Core syntax and mental models |

| Pattern precedence | Mastering Regular Expressions Ch. 2 | Prevents incorrect matches |

| POSIX regex rules | The Linux Command Line (Shotts) Ch. 19 | CLI portability |

Engine Internals & Automata

| Concept | Book & Chapter | Why This Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Regex to NFA | Engineering a Compiler (Cooper & Torczon) Ch. 2.4 | Foundation for engine building |

| DFA vs NFA | Introduction to Automata Theory (Hopcroft et al.) Ch. 2 | Performance trade-offs |

| Practical regex mechanics | Mastering Regular Expressions Ch. 4 | Understand backtracking |

Performance & Security

| Concept | Book & Chapter | Why This Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Catastrophic backtracking | Mastering Regular Expressions Ch. 6 | Security and reliability |

| Input validation patterns | Regular Expressions Cookbook Ch. 4 | Real-world validators |

| Debugging patterns | Building a Debugger (Brand) Ch. 1-2 | Build the debugger project |

Standards & Specs (High-Value Primary Sources)

| Concept | Source | Why This Matters |

|---|---|---|

| URI/URL grammar | RFC 3986 | Canonical URL structure for Project 5 |

| Email addr-spec | RFC 5322 + RFC 5321 | Standards for parsing and validation in Project 5 |

| Markdown parsing rules | CommonMark Spec + test suite | Correctness baseline for Project 7 |

| POSIX regex grammar | OpenBSD re_format.7 | Precise BRE/ERE rules and leftmost-longest behavior |

| Safe regex engine constraints | RE2 Syntax/README | Why some features are disallowed for linear time |

| Thompson NFA explanation | Russ Cox regex article | Foundation for Projects 11-13 |

Quick Start

Your First 48 Hours

Day 1 (4 hours):

- Read Chapter 1 and Chapter 3 in the primer.

- Skim Chapter 8 (engines) for the high-level idea.

- Start Project 1 and build a minimal matcher with

search(). - Test with 5 simple patterns and 2 edge cases.

Day 2 (4 hours):

- Add flags

-i,-n, and-vto Project 1. - Add a simple highlight feature using match spans.

- Read Project 1’s Core Question and Hints.

- Run against a real log file and record results.

End of Weekend: You can explain how a regex engine walks through input and why anchors and quantifiers matter.

Recommended Learning Paths

Path 1: The Practical Engineer

Best for: Developers who want regex for daily work

- Projects 1 -> 2 -> 3

- Projects 5 -> 6

- Projects 8 -> 10

Path 2: The Security-Minded Builder

Best for: Anyone working with untrusted input

- Projects 1 -> 2 -> 4

- Projects 6 -> 8

- Project 13 (optimizer) for mitigation

Path 3: The Language Tooling Path

Best for: Compiler or tooling builders

- Projects 1 -> 9 -> 11

- Projects 12 -> 13

- Project 14 (Capstone)

Path 4: The Completionist

Best for: Full mastery

- Complete Projects 1-14 in order

- Finish Project 14 (Capstone) as an integrated system

Success Metrics

By the end of this guide, you should be able to:

- Design regex with explicit mental models (not trial-and-error)

- Predict performance issues and avoid catastrophic backtracking

- Explain engine trade-offs (backtracking vs automata)

- Build and debug a small regex engine

- Use regex safely for untrusted input

Optional Appendices

Appendix A: Regex Flavor Cheatsheet

| Flavor | Notes |

|---|---|

| POSIX BRE/ERE | Standardized; BRE escapes +, ?, |, () |

| PCRE/Perl | Feature-rich; backtracking engine |

Python re |

PCRE-like syntax; backtracking engine |

| JavaScript | ECMAScript regex; some lookbehind limitations |

| RE2 | Linear-time, no backreferences or lookaround |

Appendix B: Performance Checklist

- Anchor when possible (

^and$) - Avoid nested quantifiers with overlap

- Prefer specific classes over

.* - Use possessive/atomic constructs when supported

- Benchmark with worst-case inputs

Appendix C: Security Checklist (ReDoS)

- Never run untrusted regex in a backtracking engine

- Limit input length for regex validation

- Use timeouts or safe engines for large inputs

- Test patterns against evil inputs like

(a+)+$

Appendix D: Standards & Specs You Should Skim

- POSIX regex grammar and flavor rules (re_format.7): https://man.openbsd.org/re_format.7

- RE2 syntax restrictions (linear-time, no backreferences): https://github.com/google/re2/wiki/Syntax

- URI/URL grammar (RFC 3986): https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc3986

- Email address grammar (RFC 5322, addr-spec): https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc5322

- SMTP envelope constraints (RFC 5321): https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc5321

- CommonMark spec + test suite (Markdown parsing): https://spec.commonmark.org/

- Apache Common Log Format (real-world log parsing): https://httpd.apache.org/docs/2.4/logs.html

Project Overview Table

| Project | Difficulty | Time | Depth of Understanding | Fun Factor | Business Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pattern Matcher CLI | Beginner | Weekend | ⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐ | Resume Gold |

| 2. Text Validator | Beginner | Weekend | ⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐ | Micro-SaaS |

| 3. Search & Replace | Intermediate | 1 week | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐ | Micro-SaaS |

| 4. Input Sanitizer | Intermediate | 1 week | ⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐ | Service |

| 5. URL/Email Parser | Intermediate | 1 week | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐ | Micro-SaaS |

| 6. Log Parser | Intermediate | 1-2 weeks | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐ | Service |

| 7. Markdown Parser | Advanced | 2 weeks | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ | Open Core |

| 8. Data Extractor | Intermediate | 1-2 weeks | ⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ | Service |

| 9. Tokenizer/Lexer | Advanced | 2-3 weeks | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ | Open Core |

| 10. Template Engine | Intermediate | 1-2 weeks | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ | Service |

| 11. Regex Engine | Expert | 1 month | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ | Disruptor |

| 12. Regex Debugger | Advanced | 2-3 weeks | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ | Service |

| 13. Regex Optimizer | Expert | 1 month | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ | Open Core |

| 14. Full Regex Suite (Capstone) | Master | 3-4 months | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ | Industry Disruptor |

Project List

Project 1: Pattern Matcher CLI

- File: LEARN_REGEX_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: Python

- Alternative Programming Languages: JavaScript, Go, Rust

- Coolness Level: Level 2: Practical but Forgettable

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 1: Beginner

- Knowledge Area: Basic Pattern Matching

- Software or Tool: grep-like CLI

- Main Book: “Mastering Regular Expressions” by Jeffrey Friedl

What you’ll build: A command-line tool like grep that searches files for lines matching a regex pattern, with options for case-insensitive search, line numbers, and inverted matching.

Why it teaches regex: This project introduces you to basic regex operations in a practical context. You’ll learn how patterns are compiled, matched, and how different flags affect matching behavior.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Pattern compilation → maps to understanding regex engines

- Line-by-line matching → maps to anchors and multiline mode

- Case insensitivity → maps to regex flags

- Match highlighting → maps to capturing match positions

Key Concepts:

- Basic Pattern Matching: “Mastering Regular Expressions” Chapter 1 - Friedl

- Regex in Python: Python

remodule documentation - grep Internals: GNU grep source code comments

Difficulty: Beginner Time estimate: Weekend Prerequisites: Basic programming, command line familiarity

Real World Outcome

$ pgrep "error" server.log

server.log:42: Connection error: timeout

server.log:156: Database error: connection refused

server.log:203: Authentication error: invalid token

$ pgrep -i "ERROR" server.log # Case insensitive

server.log:42: Connection error: timeout

server.log:89: ERROR: Disk full

server.log:156: Database error: connection refused

$ pgrep -n "\d{3}-\d{4}" contacts.txt # Show line numbers

15: John: 555-1234

23: Jane: 555-5678

31: Bob: 555-9012

$ pgrep -v "^#" config.ini # Invert match (show non-comments)

host=localhost

port=8080

debug=true

$ pgrep -c "TODO" *.py # Count matches

main.py: 3

utils.py: 7

tests.py: 1

$ pgrep -o "https?://\S+" README.md # Only show matched part

https://github.com/user/repo

http://example.com/docs

https://api.example.com/v1

Implementation Hints:

Core matching logic:

1. Compile the regex pattern (with flags)

2. For each line in the file:

a. Apply the regex

b. If match found (or not found for -v):

- Store/display the result

- Track line numbers if needed

3. Handle output formatting (highlighting, counts, etc.)

Key operations to understand:

search() - Find pattern anywhere in string

match() - Find pattern at start of string

findall() - Find all occurrences

finditer() - Iterator over match objects (with positions)

Flags to implement:

-i re.IGNORECASE Case-insensitive matching

-v (invert logic) Show non-matching lines

-n (add numbers) Prefix with line numbers

-c (count mode) Only show count of matches

-o (only matching) Show only the matched part

-l (files only) Only show filenames with matches

Questions to consider:

- What happens with invalid regex syntax?

- How do you handle binary files?

- How do you match across multiple lines?

Learning milestones:

- Basic patterns work → You understand literal matching

- Metacharacters work → You understand special characters

- Flags affect matching → You understand regex modifiers

- Match positions available → You understand match objects

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do regex patterns actually find matches in text, and what happens step-by-step during the matching process?”

This project forces you to understand that regex isn’t magic—it’s a systematic character-by-character comparison process. You’ll discover how the engine walks through your pattern and your text simultaneously, how backtracking works when matches fail partway through, and why some patterns are fast while others can be catastrophically slow.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Before writing a single line of code, stop and research these concepts:

-

Finite State Machines - Can you draw a simple FSM for the pattern

/ab*c/? What states exist? What transitions happen on each character? Book reference: “Mastering Regular Expressions” Chapter 4 - The Mechanics of Expression Processing. -

Greedy vs Lazy Matching - If the pattern is

/a.*b/and the text is “aXXbYYb”, what gets matched? Why? What happens if you change it to/a.*?b/? -

Pattern Compilation - Why does Python have

re.compile()? What work happens during compilation vs during matching? What’s the performance difference? -

The Difference Between match(), search(), and findall() - Given the pattern

/\d+/and text “abc123def456”, what does each function return? Why would you use one over another? -

Regex Flags and Their Effects - What exactly does

re.IGNORECASEchange internally? What aboutre.MULTILINE? How do^and$behave differently with and without MULTILINE?

Questions to Guide Your Design

Work through these questions before coding—they’ll lead you to the right implementation:

-

How do you read a pattern from command line args and compile it safely? What exception gets raised for invalid patterns? How do you show the user where the error is?

-

What data structure should you use to store matches? Do you need just the matched text, or also positions? What about the groups?

-

How do you implement the

-v(invert match) flag efficiently? Do you still need to run the regex, or can you skip it somehow? -

What happens when the file is too large to fit in memory? Should you read line-by-line or load everything at once? What are the tradeoffs?

-

How do you highlight the matched portion within a line? What information does a match object give you? How do you splice the highlight codes into the output?

-

Why does grep use

search()semantics rather thanmatch()? What behavior difference would users notice if you usedmatch()instead?

Thinking Exercise

Before coding, trace through these examples by hand on paper:

Exercise 1: For the pattern /a.+b/ and text “aXYbZb”, walk through each step of the matching process:

- Where does the engine start?

- What happens at each character?

- When does backtracking occur?

- What is the final match?

Exercise 2: For the pattern /^error:/i with flag re.IGNORECASE and these lines:

Error: disk full

WARNING: low memory

error: connection refused

error: indented

Which lines match and why? What changes if you remove the ^ anchor?

Exercise 3: Draw a flowchart showing the logic for your CLI tool’s main loop. Include:

- Reading lines from file(s)

- Applying the pattern

- Handling all flags (-i, -v, -n, -c, -o)

- Producing output

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

After completing this project, you should be able to answer:

-

“What’s the difference between

match()andsearch()in Python’s regex?” - The answer involves anchoring behavior and where the engine starts looking. -

“Why might a regex pattern cause exponential time complexity?” - This leads to discussions of catastrophic backtracking, ReDoS vulnerabilities, and why patterns like

(a+)+$are dangerous. -

“How would you implement basic grep functionality?” - Walk through your implementation choices: line-by-line processing, flag handling, output formatting.

-

“What’s a character class and when would you use one?” - Explain

[abc]vs(a|b|c), efficiency implications, and negation with[^abc]. -

“How do regex flags work under the hood?” - Discuss how

re.IGNORECASEmight be implemented (case-fold comparison table), and whatre.MULTILINEchanges about anchor behavior. -

“What happens when you compile a regex pattern?” - Explain the transformation from pattern string to internal representation (NFA/DFA), and why compilation is a separate step.

-

“How would you debug a regex that’s not matching what you expect?” - Tools like regex101.com, breaking patterns into smaller pieces, using verbose mode with comments.

Hints in Layers

Only look at these if you’re stuck. Try to solve problems yourself first.

Hint 1: Starting the CLI Structure

Use Python’s argparse module for parsing command-line arguments. Start with just one flag (-i for case-insensitive) and one file. Get that working before adding more flags. The basic structure is: parse args → compile pattern → loop through file → print matches.

Hint 2: Compiling Patterns Safely

Wrap your re.compile() call in a try/except block. When you catch re.error, the exception object has a msg attribute with the error description and a pos attribute showing where in the pattern the error was detected. Print both to help users fix their patterns.

Hint 3: Implementing Match Highlighting

The match object from search() or finditer() has .start() and .end() methods giving you the position of the match. Use ANSI escape codes for coloring: \033[31m for red, \033[0m to reset. Slice the line: line[:start] + RED + line[start:end] + RESET + line[end:].

Hint 4: Debugging Unexpected Match Behavior

If your pattern isn’t matching what you expect, print out the pattern after compilation with print(repr(pattern.pattern)) to see exactly what regex is being used. Also print pattern.flags to verify your flags are being applied. Use re.VERBOSE mode to add comments to complex patterns.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter/Section |

|---|---|---|

| How regex engines work internally | “Mastering Regular Expressions” - Friedl | Chapter 4: The Mechanics of Expression Processing |

| Pattern syntax fundamentals | “Mastering Regular Expressions” - Friedl | Chapter 1: Introduction to Regular Expressions |

| Python’s re module specifics | “Mastering Regular Expressions” - Friedl | Chapter 9: Python |

| grep design and history | “The Linux Command Line” - Shotts | Chapter 19: Regular Expressions |

| Command-line tool design | “The Unix Programming Environment” - Kernighan & Pike | Chapter 4: Filters |

| Performance considerations | “High Performance Python” - Gorelick & Ozsvald | Chapter 2: Profiling (for understanding why regex can be slow) |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem 1: “Everything matches, even when it shouldn’t”

- Why: You used

search()on every line without anchoring or forgot the-vinversion logic. - Fix: Use anchors when intended (

^...$) and invert only after a match is computed. - Quick test:

pgrep "^ERROR" file.logshould only show lines that start with ERROR.

Problem 2: “Line numbers are off by one”

- Why: Line counters start at 0 or the file is read in chunks without tracking offsets.

- Fix: Start counting at 1 and increment on every newline read.

- Quick test: Compare output with

nl -ba file.log.

Problem 3: “Highlighting breaks output or colors the wrong span”

- Why: Using the wrong span (

match.start()/match.end()from a different match) or forgetting to reset ANSI codes. - Fix: Use the exact match object per line and wrap with

\033[31mand\033[0m. - Quick test: Ensure colors reset after each line.

Problem 4: “Binary files crash or show garbage”

- Why: Reading files as text without error handling.

- Fix: Use binary detection or

errors='replace'and document behavior. - Quick test: Run against a

.pngfile and ensure a clean warning.

Definition of Done

- Supports

-i,-v,-n,-c,-o,-lflags with correct behavior - Properly handles invalid regex with clear error position

- Highlights matches without corrupting output

- Processes large files line-by-line without high memory use

- Passes a test corpus covering anchors, classes, and quantifiers

Project 2: Text Validator Library