Learn Procedural Roguelike Development: From Zero to Infinite Worlds

Goal: Deeply understand the fusion of procedural generation, game mechanics, and emergent AI. You will learn how to build “engines of infinite content” by mastering PRNG seeds, spatial partitioning algorithms, and autonomous agent behaviors. By the end, you won’t just be making a game; you’ll be building a self-generating universe where every playthrough is a unique, verifiable adventure.

Why Procedural Roguelikes Matter

In 1972, C gave programmers direct access to memory. In 1980, Rogue gave them a way to generate infinite universes using that memory. Procedural generation isn’t just a technical shortcut—it’s a fundamental shift in game design from “crafting experiences” to “crafting rules that create experiences.”

That decision shaped some of the most successful titles in history:

- Minecraft (300M+ copies sold) uses procedural generation to create a world roughly 9 million times the surface area of Earth.

- Dwarf Fortress simulates thousands of years of history, geology, and individual character psychology before the player even takes their first step.

- No Man’s Sky was built by a core team of only ~15 people, yet it contains 18 quintillion planets. They didn’t build planets; they built the math that builds planets.

The Power of Rule-Based Design

Why does this approach dominate replayable genres? Because understanding procedurality is understanding the limits of human content creation:

Static Design (Traditional) Procedural Design (Roguelike)

↓ ↓

Manual level design Design the "Dungeon Rules"

↓ ↓

Fixed player experience Infinite varied experiences

↓ ↓

Linear replay value Emergent replay value

In a traditional game, a player memorizes the level. In a roguelike, a player must master the systems. This knowledge—how to manage PRNG seeds, spatial partitioning, and autonomous agent behaviors—is the foundation of modern technical game development and high-performance simulation.

The Content Hierarchy: From Noise to Narrative

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ The Universe │

│ ┌─────────┐ │

│ │ Seeds │ ← The foundation (4-8 bytes of entropy) │

│ └────┬────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ┌────┴────┐ │

│ │ Noise │ ← The terrain (Perlin/Simplex gradients) │

│ └────┬────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ┌────┴────┐ │

│ │ Space │ ← The structure (BSP/Cellular Automata) │

│ └────┬────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ┌────┴────┐ │

│ │ Agents │ ← The life (A*, Behavior Trees, Ecosystems) │

│ └────┬────┘ │

└───────┼─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

┌───────┴─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ The Narrative (Quests, History, Lore) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

When you write Random rnd = new Random(seed);, you’re not just “picking a number”—you’re initializing an entire hierarchy of content. Understanding this is why procedural developers can create more content with fewer resources.

Core Concept Analysis

1. The Seed of Infinity: Pseudorandomness and Determinism

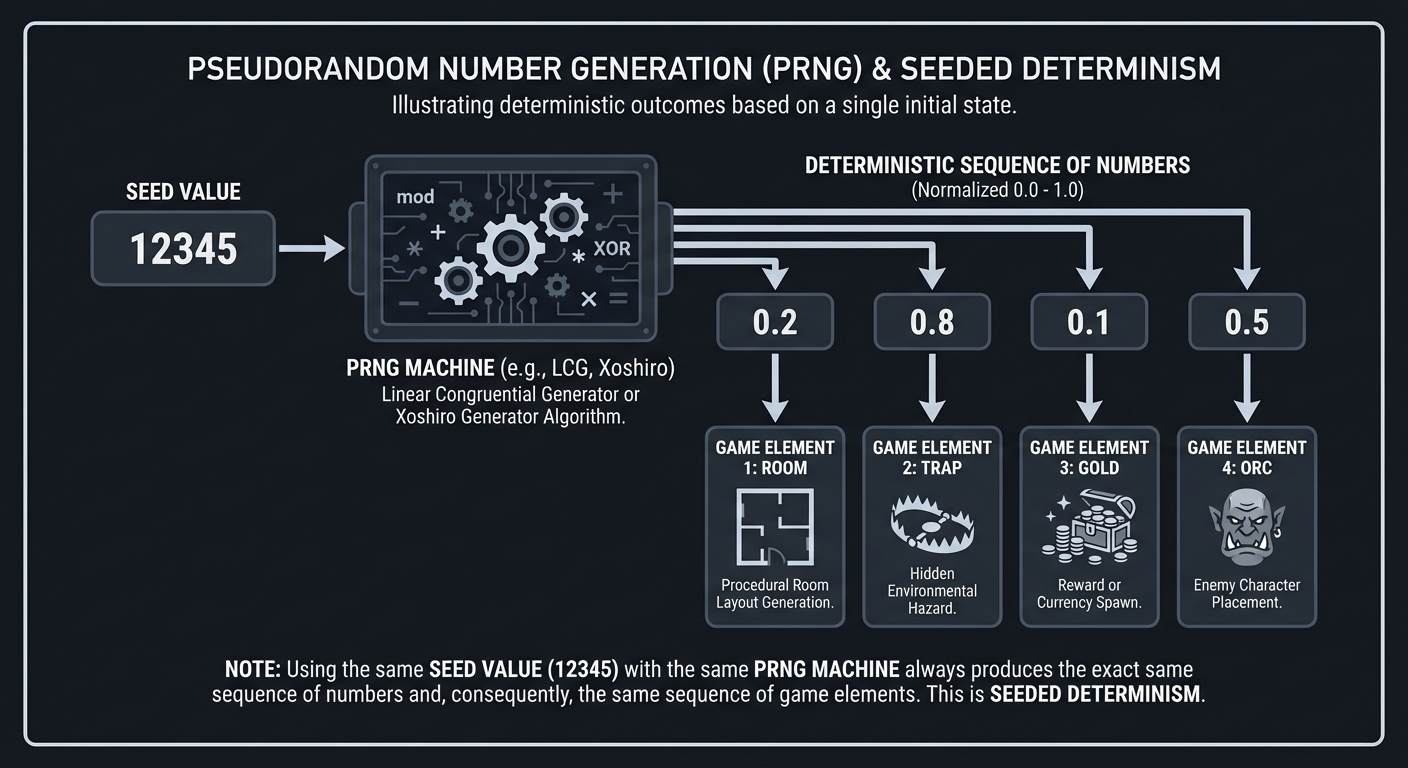

In a procedural game, “randomness” is an illusion. Most games use a Pseudorandom Number Generator (PRNG). A PRNG is a mathematical function that takes a starting value—the Seed—and produces a long, complicated, but entirely predictable sequence of numbers.

[Seed: 12345] -> [PRNG Machine (e.g. LCG or Xoshiro)] -> [Seq: 0.2, 0.8, 0.1, 0.5...]

| | | |

V V V V

[Room][Trap][Gold][Orc]

Key Insight: If you know the seed, you know the future. This allows for:

- Verifiable Worlds: Players can share a 4-byte string to play in the exact same world.

- Bug Reproducibility: If a crash happens on Level 4, saving the seed allows developers to recreate the exact level state for debugging.

- Data Compression: Instead of storing a 50MB level file, you store a single integer. The world is “re-calculated” rather than loaded.

Further Reading: The Nature of Code by Daniel Shiffman — Ch. 0: “Randomness”

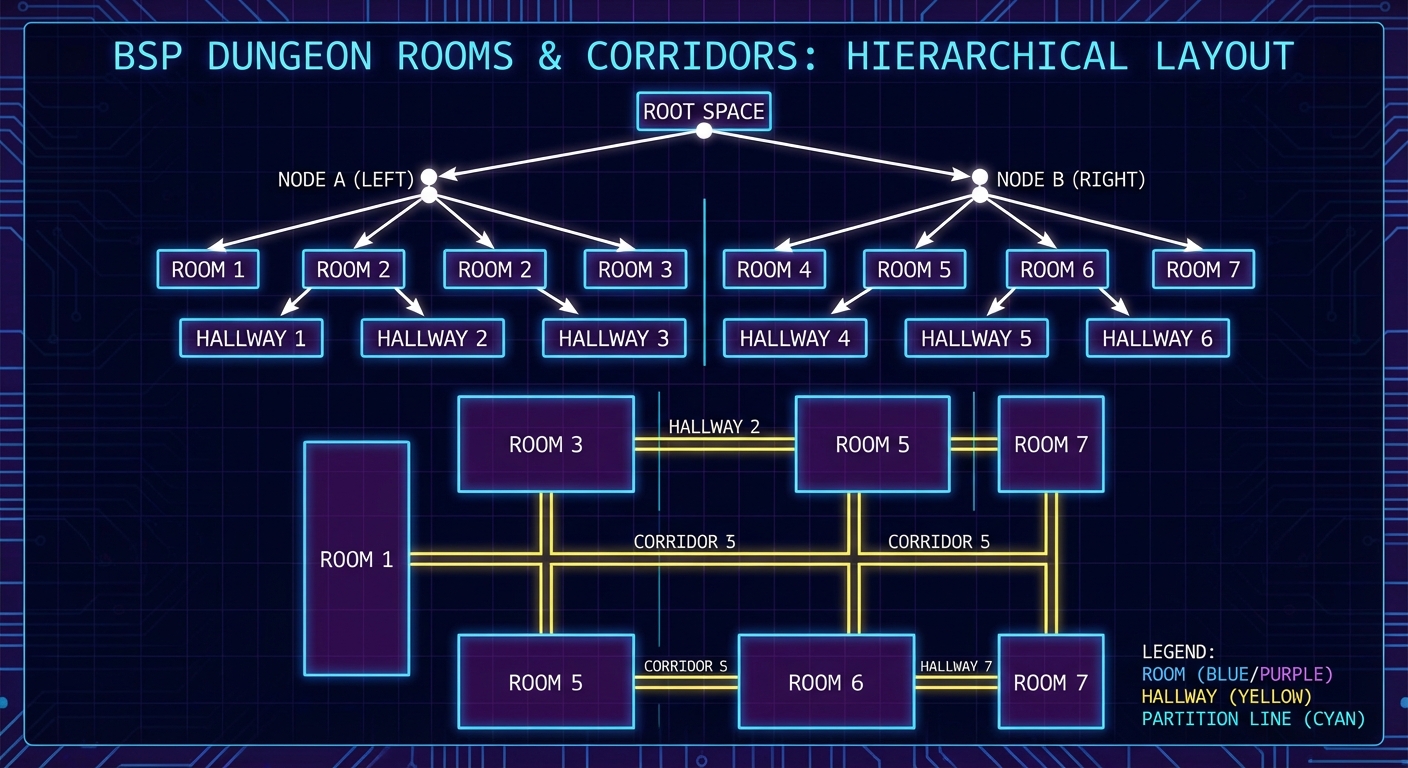

2. Spatial Partitioning: Binary Space Partitioning (BSP)

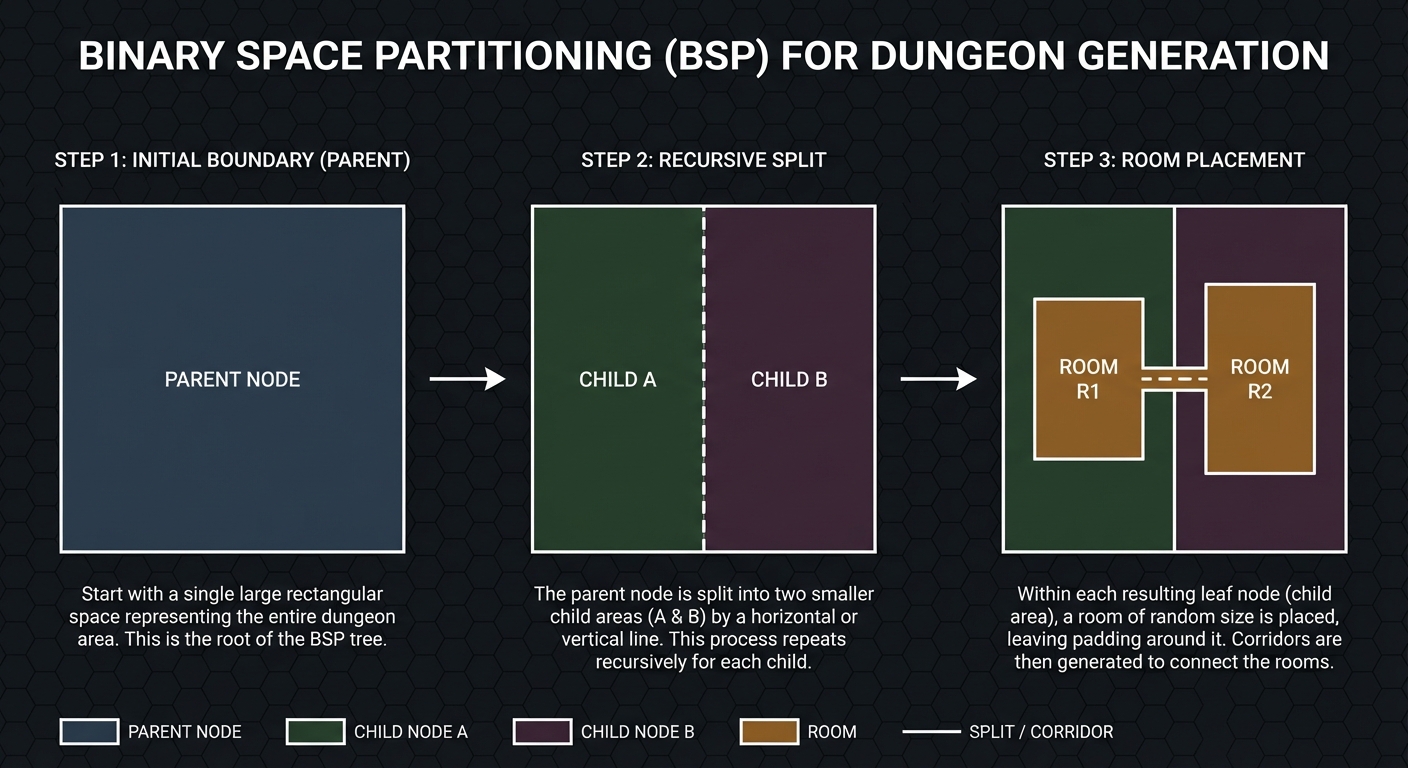

Dungeons aren’t just a mess of rooms; they are organized spaces. Binary Space Partitioning (BSP) is the technique of recursively dividing a space into smaller and smaller pieces, usually to place rooms within those pieces.

Step 1: Parent Step 2: Split Step 3: Rooms

┌───────────────┐ ┌───────┬───────┐ ┌───────┬───────┐

│ │ │ │ │ │ ┌───┐ │ ┌───┐ │

│ │ │ A │ B │ │ │ R1│ │ │ R2│ │

│ │ --> │ │ │ --> │ └───┘ │ └───┘ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

└───────────────┘ └───────┴───────┘ └───────┴───────┘

This hierarchical approach ensures:

- No Overlaps: By splitting the area first, you guarantee that rooms in different branches of the BSP tree can never overlap.

- Guaranteed Connectivity: By connecting “sibling” nodes in the tree, you can ensure a path exists between every room in the dungeon.

- Structural Variety: Different split ratios (e.g., 30/70 vs 50/50) create different architectural “feels”—from tight corridors to grand halls.

Further Reading: Data Structures for Game Developers by Allen Sherrod — Ch. 5: “Trees”

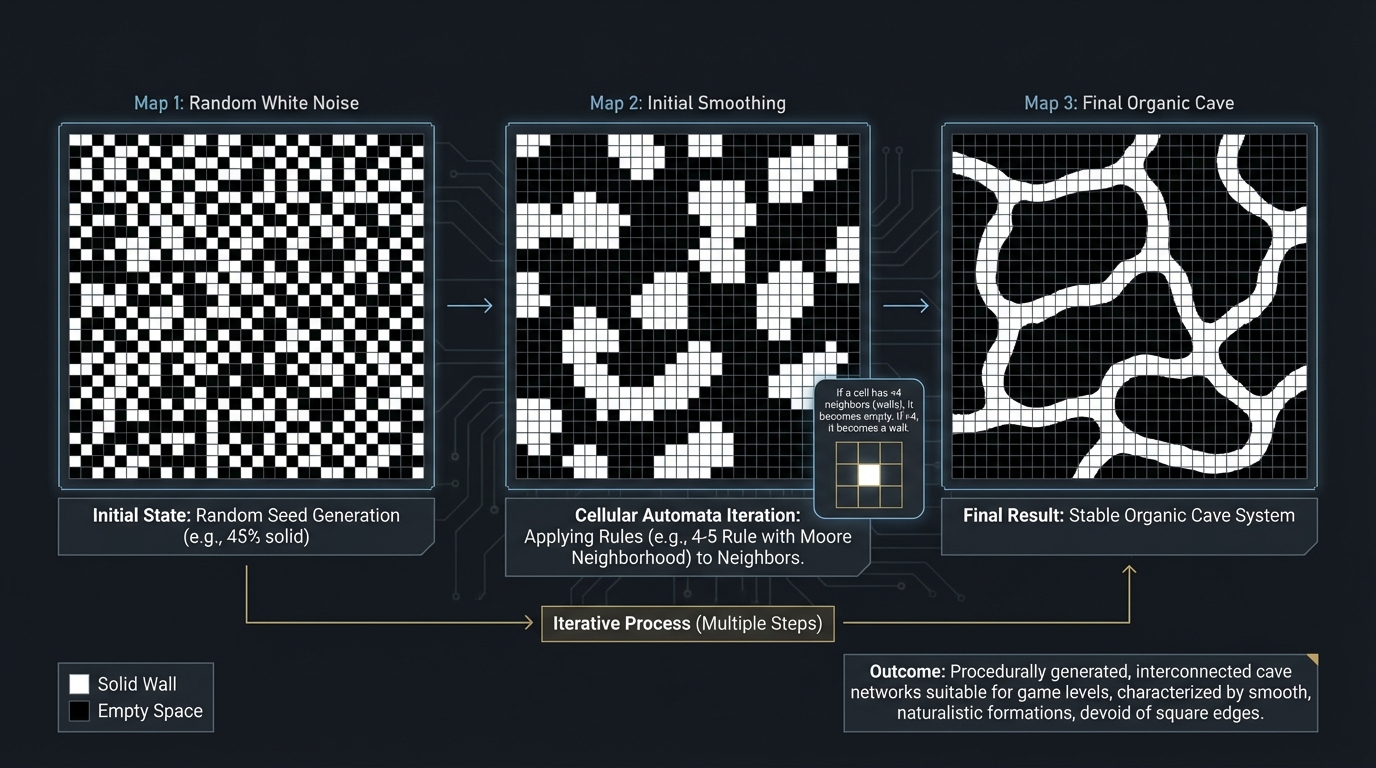

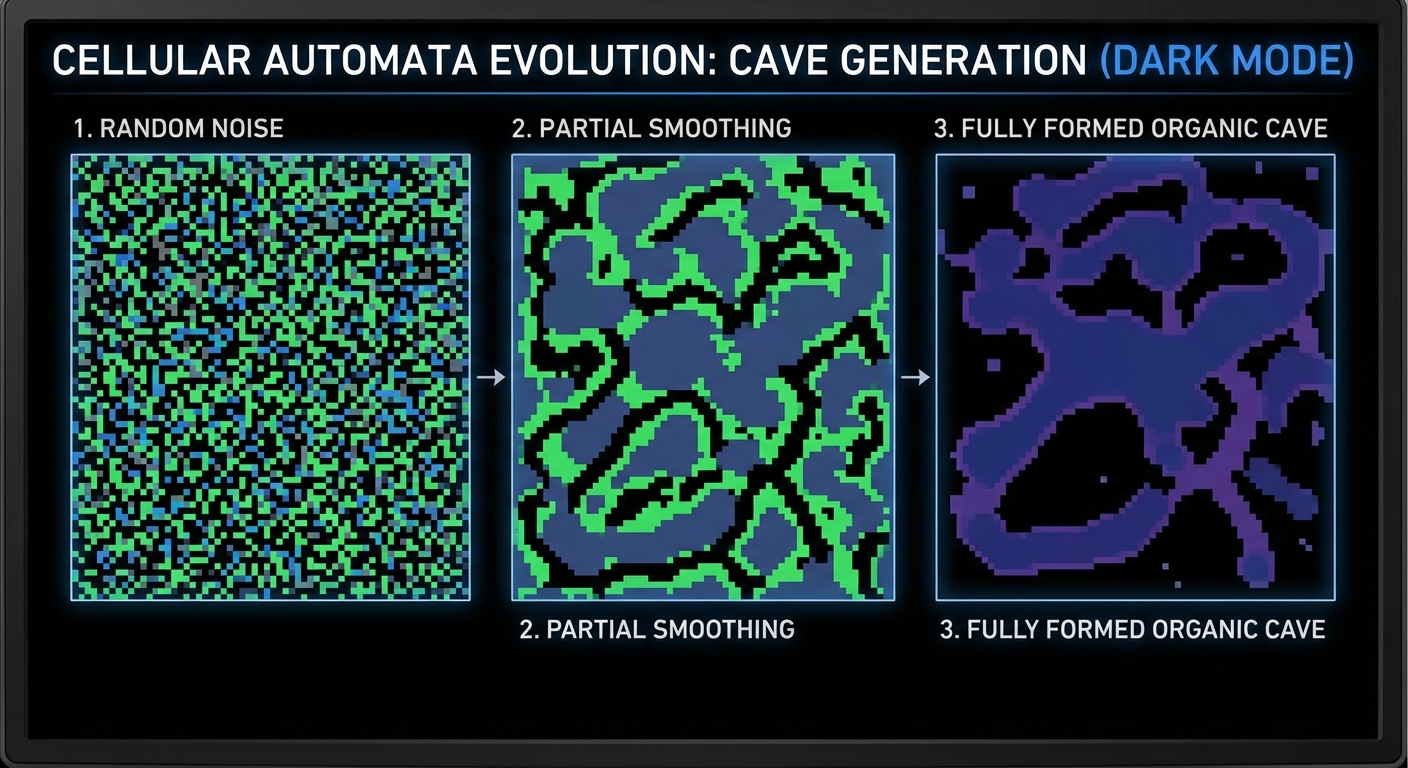

3. Organic Growth: Cellular Automata

For natural environments like caves, we use Cellular Automata (CA). This is a model where the state of a “cell” (a tile) is determined by its neighbors. In dungeon generation, we often use the “4-5 Rule”: if a tile has 5 or more wall neighbors, it becomes a wall; otherwise, it becomes floor.

Random Noise Iteration 1 Iteration 5 (Cave)

###.##..# ###.###..# ##########

#..#...## ##...#### ##......##

.#..#..#. --> .##...### --> #........#

#...#..## ##....### #........#

Key Insight: CA mimics natural erosion and growth. By running several “iterations” of these simple rules over a grid of random noise, the “noise” smoothens into organic, winding cavern structures.

Further Reading: Procedural Content Generation in Games by Shaker et al. — Ch. 3: “Dungeon Generation”

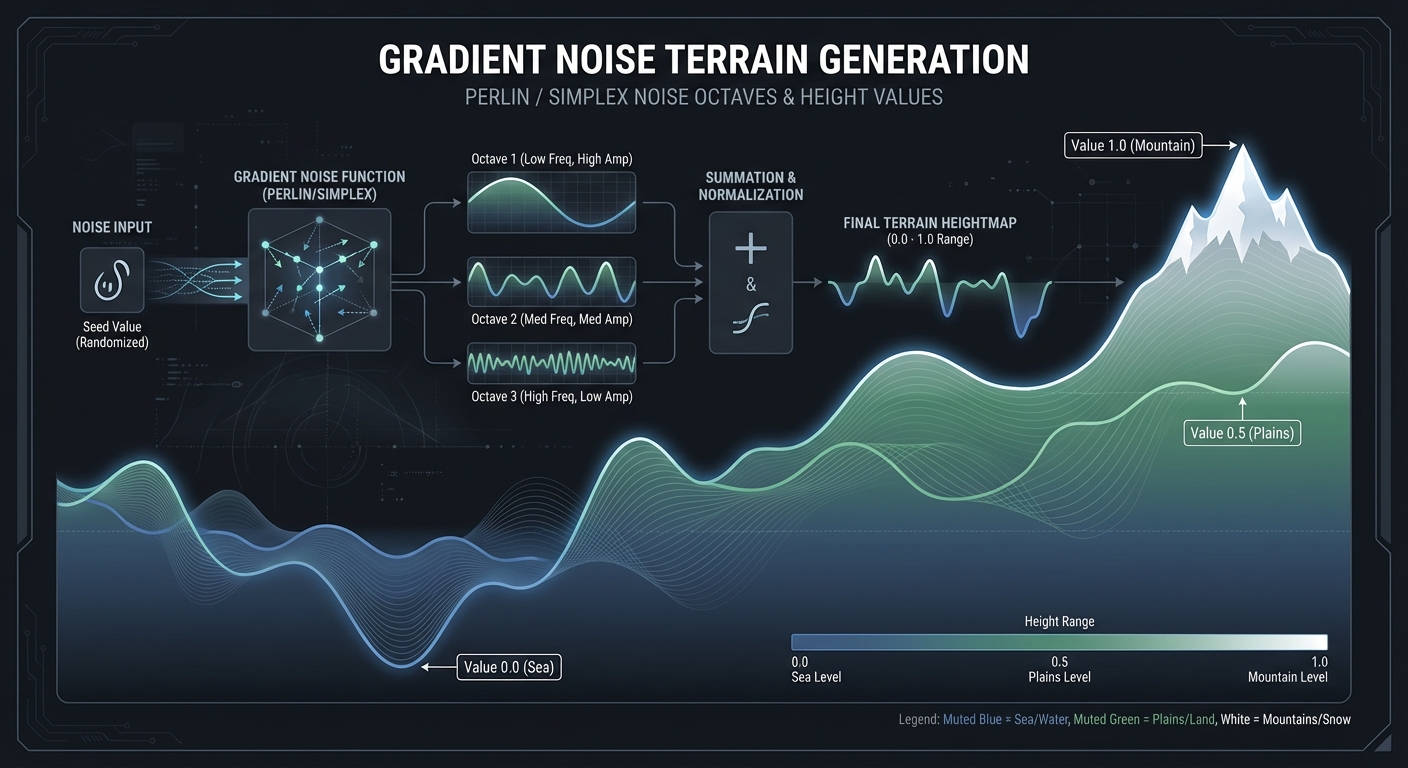

4. Coherent Noise: Perlin & Simplex

While CA is great for discrete grids, Perlin Noise is used for continuous, smooth terrain. Unlike “white noise” (where every pixel is independent), Perlin noise ensures that neighboring points have similar values.

Value 1.0 (Mountain) ^

/ \

Value 0.5 (Plains) / \_____

/ \

Value 0.0 (Sea) / \_____

By layering multiple “octaves” of noise—combining large, slow waves for continents with small, fast waves for pebbles—you create realistic heightmaps that can represent anything from mountain ranges to cloud patterns.

Further Reading: The Nature of Code by Daniel Shiffman — Ch. 0: “Noise”

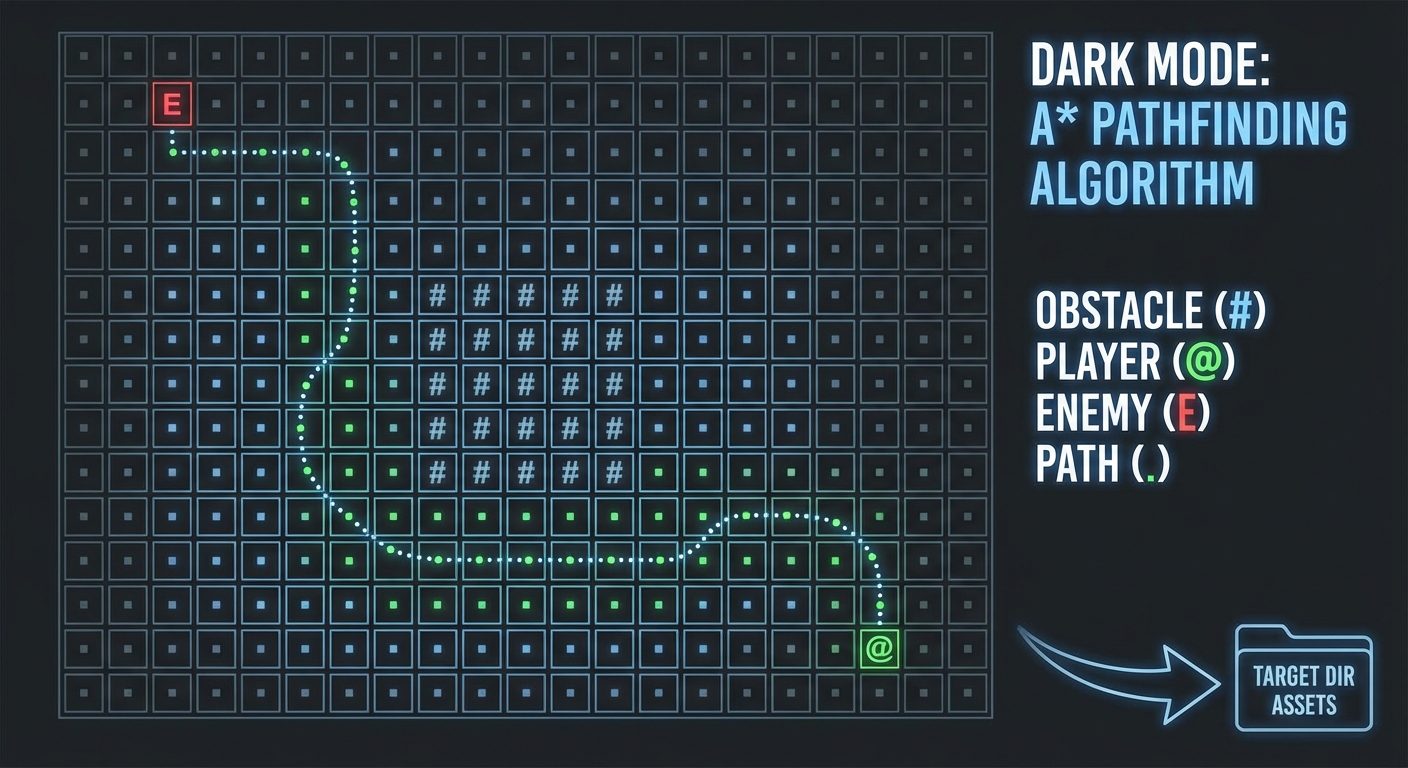

5. Intelligence in Chaos: A* Pathfinding

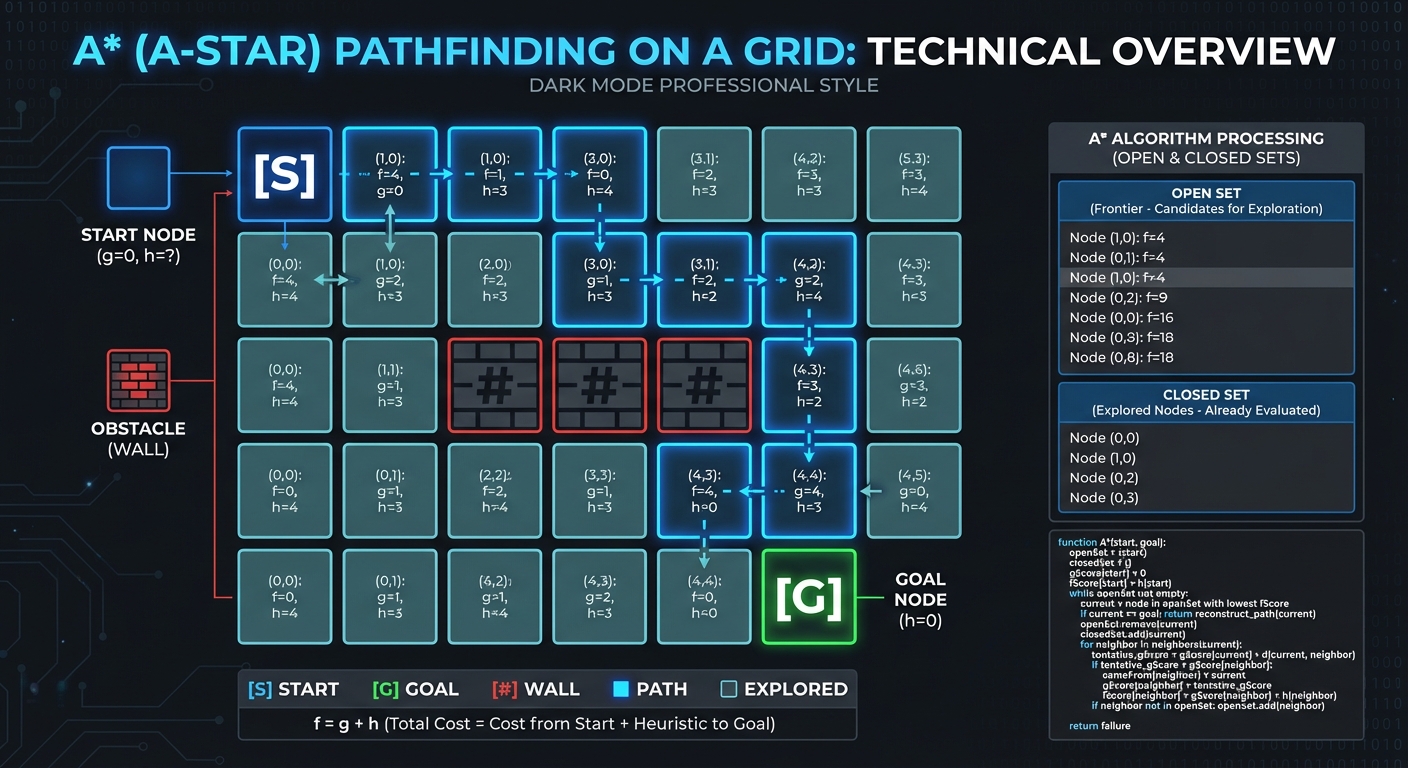

A procedural world is useless if the player or enemies can’t navigate it. A* (A-Star) is the algorithm that finds the shortest path by combining the distance traveled from the start (g-cost) with an estimated distance to the goal (h-cost, or heuristic).

[S] . . . [X] [S] = Start

. # # . . [G] = Goal

. . # . [G] [#] = Wall

Key Insight: The “Heuristic” (usually Manhattan Distance on a grid) allows the search to prioritize tiles that are “closer” to the goal, making it vastly more efficient than a blind search like BFS.

Further Reading: Artificial Intelligence for Games by Millington — Ch. 4: “Pathfinding”

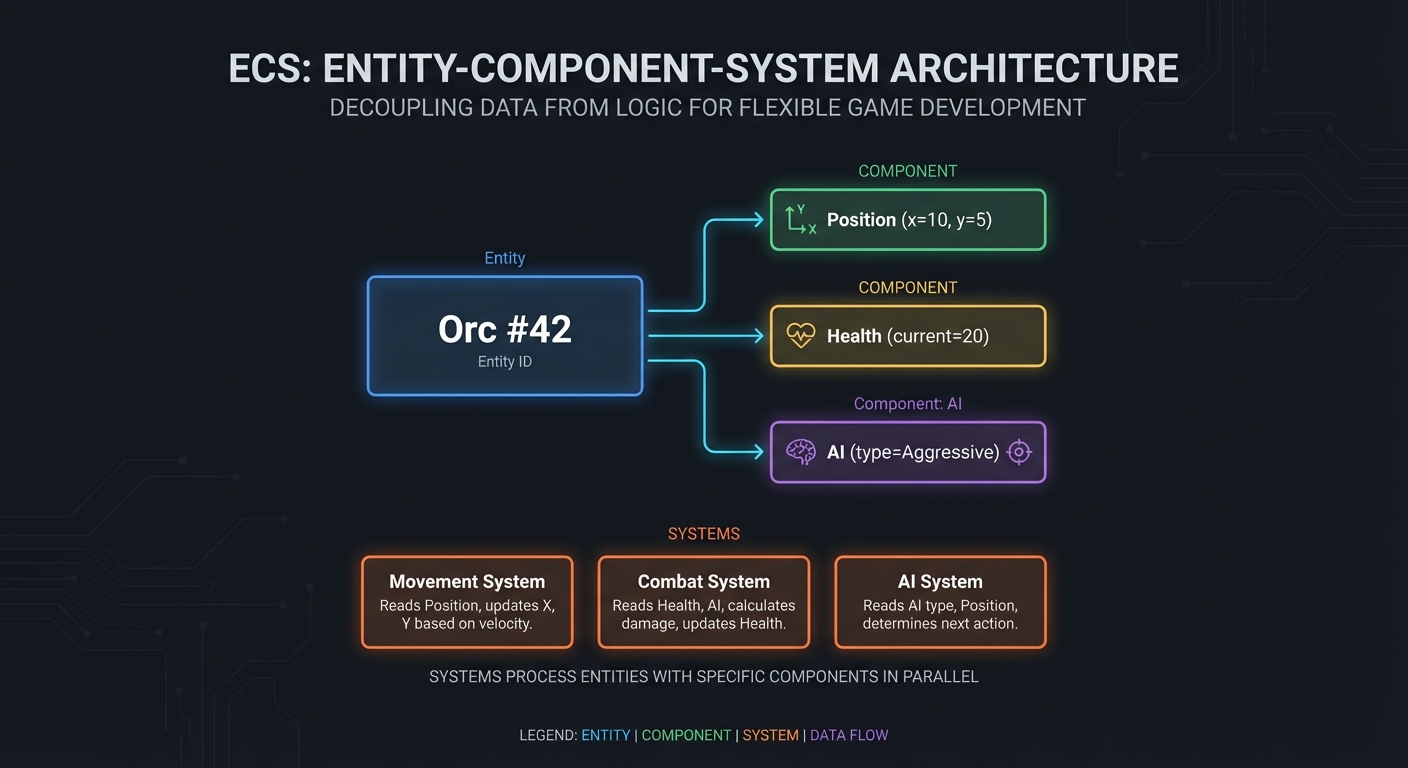

6. The Entity-Component-System (ECS)

Roguelikes often feature thousands of items, enemies, and interactive objects. Traditional Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) can become a bottleneck due to deep inheritance trees and poor cache locality. ECS decouples data from logic:

- Entities: Just a unique ID.

- Components: Pure data structures (e.g.,

Position,Health). - Systems: Logic that operates on entities having specific components.

Entity [Orc #42]

├─ Component: Position (x=10, y=5)

├─ Component: Health (current=20)

└─ Component: AI (type="Aggressive")

Further Reading: Game Programming Patterns by Robert Nystrom — Ch. 14: “Component”

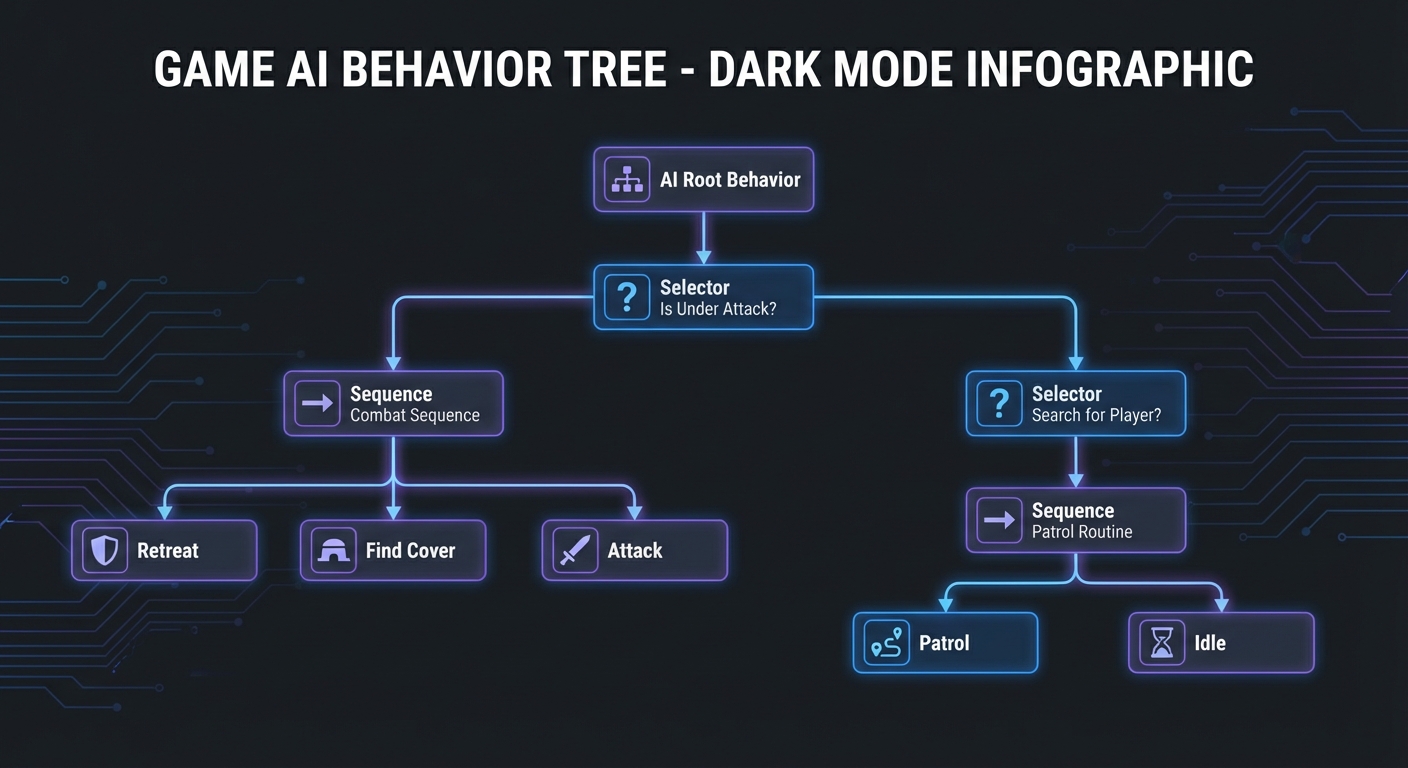

7. Logic Composition: Behavior Trees

Simple “if/else” logic fails when an NPC needs to decide between attacking, fleeing, or healing. Behavior Trees (BT) provide a hierarchical way to compose complex intelligence.

Root (Selector)

├── Sequence (Survival)

│ ├── Condition: IsHP_Low?

│ └── Action: Retreat_to_Safety

├── Sequence (Attack)

│ ├── Condition: IsPlayerInRange?

│ └── Action: AttackPlayer

└── Action: Idle_Patrol

Key Insight: BTs are reactive. Every turn, the tree is “ticked” from the root, allowing the NPC to instantly switch from “Patrolling” to “Survival” if their health drops.

Further Reading: Artificial Intelligence for Games by Millington — Ch. 5.4

8. Data Persistence: Serialization and the Delta Pattern

Saving an infinite world is impossible if you try to save every tile. Instead, we save the Seed and a Delta—a list of only the tiles or entities that have changed from their generated state.

Storage Strategy:

- world_seed: 84920

- player_pos: (120, 450)

- modified_tiles: {(120, 451): "BrokenWall"}

Key Insight: This separates the “Engine” (which generates the world) from the “State” (which records the player’s impact).

Further Reading: C# 12 in a Nutshell by Joseph Albahari — Ch. 15: “Serialization”

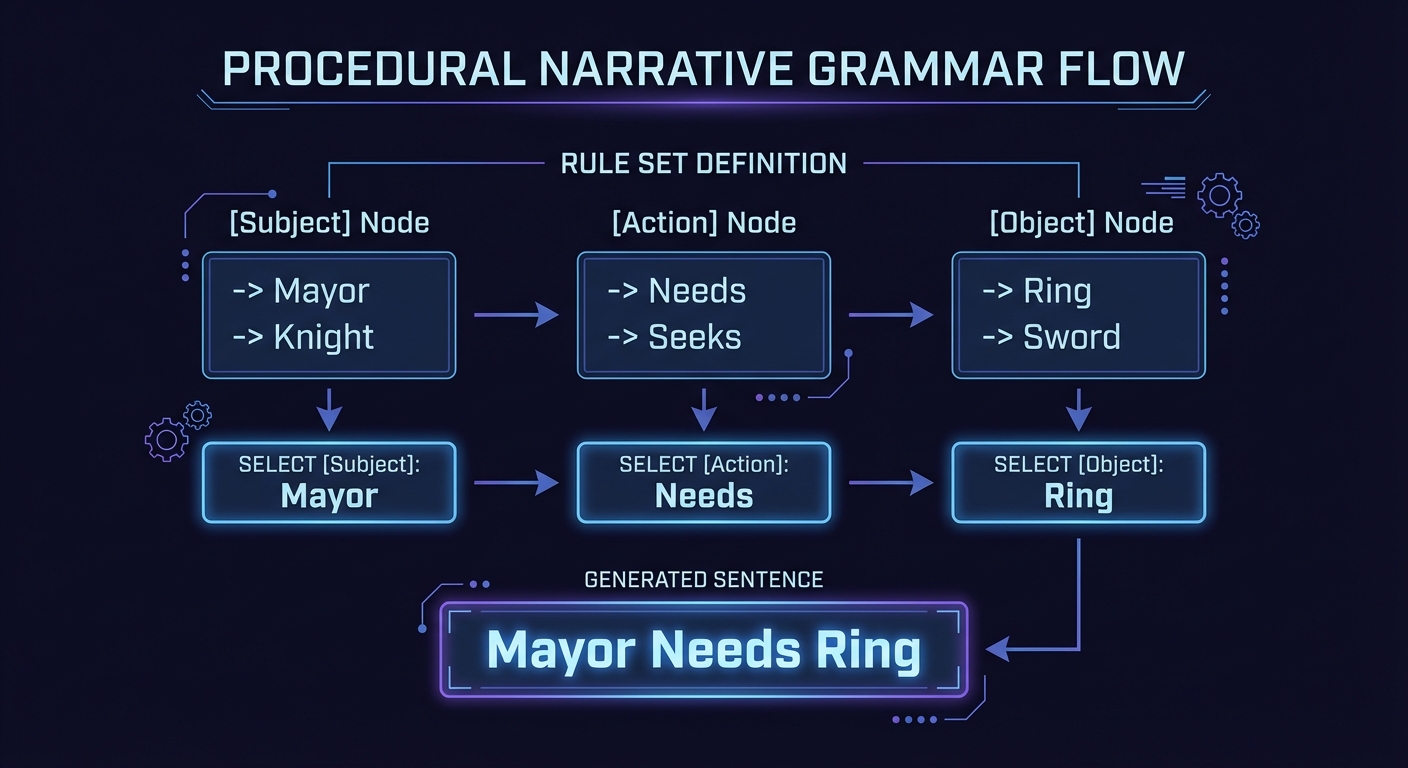

9. Narrative Generation: Grammars and Simulation

Modern roguelikes like Dwarf Fortress don’t just generate maps; they generate history. Using Context-Free Grammars (CFG), we can create infinite, logically consistent quests and lore.

[Subject] needs [Object] from [Location] because [Motivation]

Further Reading: Procedural Generation in Game Design by Tanya Short — Ch. 8: “Narrative PCG”

Concept Summary Table

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize |

|---|---|

| Determinism | Same seed = Same world. Crucial for bugs, sharing, and multiplayer. |

| Grid Logic | How to map 1D memory to 2D/3D space. Coordinate translation. |

| Recursive Partitioning | Breaking large problems into smaller ones (BSP/Quadtrees). |

| Smoothing & Erosion | Using neighborhood checks (CA) to refine raw randomness. |

| Gradient Noise | Understanding frequency and amplitude (Octaves) in Perlin noise. |

| Heuristic Search | How A* prioritizes paths based on “Distance to Goal.” |

| Data Decoupling | Composition over Inheritance (ECS/Components). |

| State Persistence | Distinguishing between “constant” world data and “variable” player changes. |

Deep Dive Reading by Concept

Foundational Theory & Genre

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| The Roguelike Genre | Game Design Deep Dive: Roguelikes by Joshua Bycer — Ch. 1-2 |

| Why Procedurality? | Procedural Generation in Game Design by Tanya Short — Ch. 1: “When and Why” |

| The History of Rogue | Dungeon Hacks by David L. Craddock — Ch. 1: “The Most Dangerous Dungeon” |

Algorithmic Deep Dives

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Cellular Automata | Procedural Content Generation in Games by Shaker et al. — Ch. 3 |

| BSP Trees | Data Structures for Game Developers by Allen Sherrod — Ch. 5 |

| Perlin Noise Masterclass | The Nature of Code by Daniel Shiffman — Ch. 0: “Randomness” |

| A* Pathfinding | Artificial Intelligence for Games by Millington — Ch. 4: “Pathfinding” |

| Map Generation Patterns | Game Programming Patterns by Robert Nystrom — Ch. 21: “Spatial Partition” |

Advanced Simulation & AI

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Behavior Trees | Artificial Intelligence for Games by Millington — Ch. 5.4 |

| Procedural Narrative | Procedural Generation in Game Design by Short — Ch. 8: “Narrative PCG” |

| Voxel Meshing | Computer Graphics from Scratch by Gabriel Gambetta — Ch. 1: “Intro” |

| Deterministic Logic | Clean Code by Robert C. Martin — Ch. 3: “Functions” (Side Effects) |

Essential Reading Order

- The Vision (Week 1):

- Procedural Generation in Game Design Ch. 1

- Game Design Deep Dive Ch. 1

- The Nature of Code (Ch. 0: Randomness)

- The Grid & The World (Week 2):

- Game Programming Patterns Ch. 21 (Spatial Partition)

- Procedural Content Generation in Games Ch. 3 (CA)

- Intelligence & Depth (Week 3):

- Artificial Intelligence for Games Ch. 4 (A*)

- Procedural Generation in Game Design Ch. 8 (Narrative)

Project List

Projects are ordered from fundamental logic to advanced “Infinite World” systems.

Project 1: The Seeded Log (The Soul of Determinism)

- Main Programming Language: C#

- Alternative Programming Languages: GDScript, C++, Python

- Coolness Level: Level 2: Practical but Forgettable

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 1: Beginner

- Knowledge Area: PRNG / Logic

- Software or Tool: Unity or Godot (Console/Terminal output only)

- Main Book: “The Nature of Code” by Daniel Shiffman

What you’ll build: A non-visual tool that generates a sequence of “events” (loot, monster spawns, weather) based on a string seed. You must prove that the same seed always produces the same sequence.

Why it teaches procedurality: This is the foundation. You’ll learn that randomness in games isn’t “random”—it’s a math sequence. If you can’t control the seed, you can’t debug a procedurally generated level.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Seed Hashing → Converting a string like “MySecretLevel” into an integer seed.

- State Leakage → Ensuring that checking a “random” loot drop doesn’t accidentally advance the sequence for the next monster spawn.

- Serialization → Saving the state of the sequence so you can resume it.

Real World Outcome

You will have a command-line tool or a console logger where entering the same text string always results in the same sequence of game events. This proves your game is deterministic.

Example Output:

$ dotnet run --seed "GoblinsCave123"

[Generation Started with Seed: 14829384]

[1] Event: Spawn Skeleton (HP: 12, Weapon: Rusty Sword)

[2] Event: Find Loot (Gold: 45, Item: Health Potion)

[3] Event: Weather Change (Rain, Visibility: -2)

[4] Event: Ambush (3 Bats)

$ dotnet run --seed "GoblinsCave123"

[Generation Started with Seed: 14829384]

[1] Event: Spawn Skeleton (HP: 12, Weapon: Rusty Sword)

[2] Event: Find Loot (Gold: 45, Item: Health Potion)

[3] Event: Weather Change (Rain, Visibility: -2)

[4] Event: Ambush (3 Bats)

# THE OUTPUT IS IDENTICAL. MISSION ACCOMPLISHED.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How can I create a billion different worlds without storing a single one on my hard drive?”

Before you write any code, sit with this question. If you understand that the Seed is the world, you understand how No Man’s Sky works.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Pseudorandom Number Generators (PRNG)

- What is the difference between

System.Randomand a truly random source? - What happens when you provide a “Seed” to a constructor?

- Book Reference: “The Nature of Code” Ch. 0 - Daniel Shiffman

- What is the difference between

- Seed Hashing

- How do you turn the string “Apple” into the number 52?

- What is a collision and why does it (rarely) happen?

- Book Reference: “Algorithms, 4th Ed” Ch. 3.4 - Sedgewick

- Determinism in Logic

- Why must the order of operations be identical every time?

- If you call

rnd.Next()10 times, why does the 11th call always return the same value for the same seed?

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Random Instance Management

- Should you have one global

Randomobject, or one per system (e.g.,LootRandom,MonsterRandom)? - What happens if the player skips a loot chest? Does the monster encounter change? How do you prevent this (decoupling)?

- Should you have one global

- Event Sequencing

- How do you map a random number (0.0 to 1.0) to a specific event? (e.g., 0.0-0.5 is Spawn, 0.5-0.8 is Loot).

Thinking Exercise

The Deterministic Trace

Look at this logic:

Random rnd = new Random(seed);

int gold = rnd.Next(1, 100);

int enemyType = rnd.Next(1, 5);

Questions:

- If I add a line

int luck = rnd.Next(1, 10);betweengoldandenemyType, willenemyTypestay the same? - Why is this a problem for “modding” or “updating” your game later?

- How would you structure your code so adding a new feature doesn’t break old seeds?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “Explain the difference between Random and Pseudorandom.”

- “How would you allow two players to play the exact same procedurally generated level?”

- “What is a ‘Seed’ in the context of a PRNG?”

- “How do you prevent ‘Save Scumming’ in a seeded roguelike?”

- “What happens to your generation if you change the order of calls in your code?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: The Setup

Use System.Random(int seed) in C#. If you don’t provide a seed, it uses the current clock time—which is NOT what you want for a roguelike.

Hint 2: String to Int

Don’t write your own hash. Use myString.GetHashCode() or a simple foreach(char c in str) seed += (int)c;.

Hint 3: Decoupling Randoms

If you want the loot to stay the same even if the number of enemies changes, give the Loot System its OWN Random object with a seed derived from the main seed (e.g., mainSeed + 1).

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Randomness Fundamentals | “The Nature of Code” | Ch. 0 |

| C# Standard Library | “C# 12 in a Nutshell” | Ch. 25 |

| Hashing Algorithms | “Algorithms, 4th Ed” | Ch. 3.4 |

Project 2: The Grid Walker (Mapping the Void)

- Main Programming Language: C#

- Alternative Programming Languages: GDScript, C++

- Coolness Level: Level 2: Practical but Forgettable

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Tilemaps / Grid Logic

- Software or Tool: Unity (Tilemap) or Godot (TileMapLayer)

- Main Book: “Game Programming Patterns” by Robert Nystrom

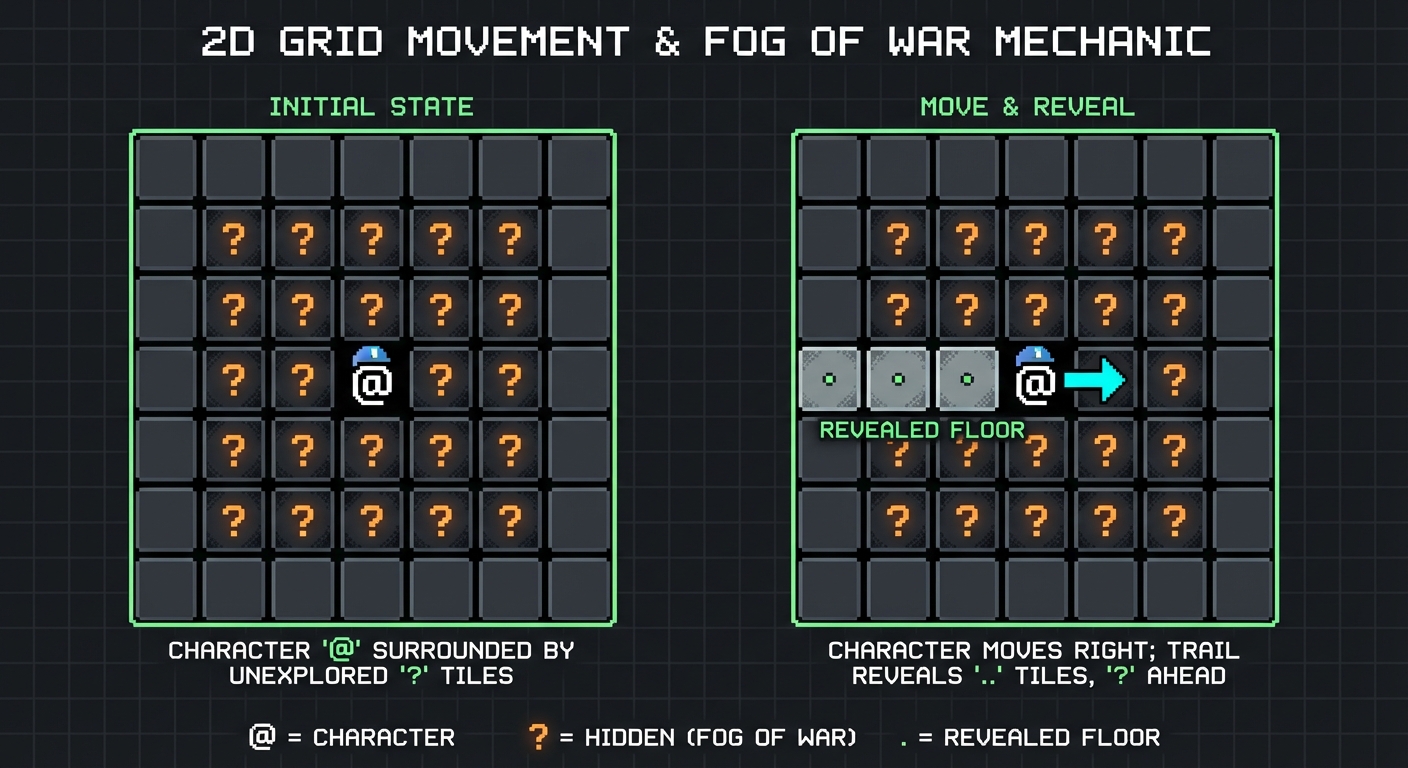

What you’ll build: A 2D grid system where a “player” (@) can move between tiles. You will implement a “Fog of War” system where tiles are only visible if the player has visited them.

Why it teaches roguelikes: Roguelikes are spatially discrete. Understanding how to map a 1D array or a Dictionary to a 2D coordinate system (x, y) is the first step to building a world.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Coordinate Mapping → Converting screen clicks to grid indices.

- Tile Data → Storing more than just an image (e.g., is this tile walkable? does it block sight?).

- Visibility State → Managing “Unexplored”, “Visible”, and “Hidden” states.

Real World Outcome

A playable screen where you move a character (the @ symbol or a sprite). As you move, the “Fog of War” clears, revealing the floor and walls. You cannot walk through walls.

Visual Representation:

[Initial State] [After Moving Right]

# # # # # # # # # #

# @?? # #. @? #

# ??? # --> #??? #

# ??? # #??? #

# # # # # # # # # #

(

(? is hidden, . is revealed floor, # is revealed wall)

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do I represent a physical world as a mathematical data structure?”

Most beginners try to use GameObjects/Nodes for every tile. This will crash your computer when the map gets large. You need to learn how to store a map as pure data.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- 2D Arrays vs. Dictionaries

- When is it better to use

Tile[width, height](fixed size, fast) vsDictionary<Vector2Int, Tile>(infinite size, flexible)? - Book Reference: “Data Structures the Fun Way” Ch. 4 - Jeremy Kubica

- When is it better to use

- The Flyweight Pattern

- If you have 1,000,000 “Grass” tiles, should they all have their own image data? (No, they should reference one “Grass” type).

- Book Reference: “Game Programming Patterns” Ch. 3 - Robert Nystrom

- Coordinate Systems

- The difference between World Space (pixels) and Grid Space (indices).

- How to translate a click at

(256.5, 12.0)to grid tile(10, 0).

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Movement Logic

- Does the player move instantly, or is there an animation?

- How do you check the “IsWalkable” property of the target tile before the player moves there?

- Data Separation

- Where is the “IsWalkable” property stored? In the visual Tilemap or in a separate

Mapclass? (Hint: Separate them).

- Where is the “IsWalkable” property stored? In the visual Tilemap or in a separate

Thinking Exercise

The Bound Check

Imagine your grid is 10x10. The player is at (9, 9). They move Right (+1, 0). What happens in your code?

- Does it return null?

- Does it crash with an

IndexOutOfRangeException? - How do you “wrap” or “block” this movement efficiently?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “How would you efficiently store a 1,000,000 x 1,000,000 tile map?”

- “What is the complexity of looking up a tile by coordinate in an array vs a hash map?”

- “How do you handle layers (e.g., ground vs. decoration) in your data structure?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: The Data

Start with an enum TileType { Wall, Floor }. Create a simple 2D array: TileType[,] map.

Hint 2: Rendering

Use Unity’s Tilemap.SetTile or Godot’s set_cell. Loop through your data array and update the visual tilemap whenever the data changes.

Hint 3: Input Handling

Intercept WASD or Arrow keys. Calculate Vector2Int targetPos = playerPos + inputDirection. Use an if statement to check if map[targetPos.x, targetPos.y] is a Floor before updating playerPos.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Memory Efficiency | “Game Programming Patterns” | Ch. 3 (Flyweight) |

| Grid Data Structures | “Data Structures the Fun Way” | Ch. 4 |

| Unity Tilemaps | “Unity Game Development Cookbook” | Ch. 5 |

Project 3: The Drunken Cave (Cellular Automata)

- Main Programming Language: C#

- Alternative Programming Languages: GDScript, Python

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Algorithms / CA

- Software or Tool: Unity/Godot

- Main Book: “Procedural Content Generation in Games” by Shaker et al.

What you’ll build: A cave generator. You start with a grid of random noise and “evolve” it into smooth, organic caverns using Cellular Automata rules (The “4-5 Rule”).

Why it teaches PCG: This is your first “Generative” project. You aren’t placing tiles; you’re setting rules for how tiles place themselves.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- The “Border” Problem → Handling neighbors for tiles on the edge of the map.

- Island Detection → What happens if the generator creates a small cave that isn’t connected to the main one? (Flood Fill).

- Iteration Count → Finding the “sweet spot” between messy noise and a single empty room.

Real World Outcome

A “Generate” button that, when clicked, transforms a static grid of random wall/floor noise into a beautiful, winding cave system. You can watch the “evolution” step-by-step.

Visual Evolution:

[Step 0: Random] [Step 2: Smoothing] [Step 5: Final Cave]

# . # #. # # # #. # # # # #

. # . . # --> # . . . # --> # . . . #

# #. #. #... # #... #

. . # . . . . . . # . . . . #

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How can simple local rules create complex global patterns?”

This is the secret of nature. A snowflake doesn’t have a blueprint; it has rules. You are learning “Emergent Design.”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Neighborhoods (Moore vs. Von Neumann)

- Do diagonal tiles count as neighbors? (Moore) or only adjacent? (Von Neumann).

- Book Reference: “Procedural Content Generation in Games” Ch. 3

- Double Buffering

- Why you can’t modify the map while you are reading from it.

- Book Reference: “Game Programming Patterns” Ch. 7 - Robert Nystrom

- Flood Fill Algorithm

- How to detect “islands” of walkable tiles that are trapped by walls.

- Book Reference: “Algorithms” - Sedgewick

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Rule Tuning

- What happens if the rule is 3 neighbors instead of 4? Does the cave become too empty?

- How many iterations are enough? (Usually 4-7).

- Border Security

- How do you handle a tile at

(0,0)? Does it have “phantom” neighbors outside the map? (Hint: Treating the border as “Wall” usually creates nice closed caves).

- How do you handle a tile at

Thinking Exercise

The 4-5 Rule

Rule: “If a tile has 5 or more Wall neighbors, it becomes a Wall. Otherwise, it becomes a Floor.” Trace this on a 3x3 grid where 6 neighbors are Walls. What happens? Now imagine a grid of pure random 50/50 noise. Will this rule make it “cleaner” or “messier”?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is Cellular Automata and how does it apply to game levels?”

- “Explain the ‘Border Problem’ in grid-based algorithms.”

- “How do you ensure a cave generated by CA is fully traversable?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Double Buffering

When calculating the next iteration, don’t modify the current map. Read from mapA, write to mapB. Then swap them (mapA = mapB). Otherwise, your changes will cascade through the same iteration!

Hint 2: Neighborhood Counting

Use a nested loop from -1 to 1 around your target tile:

for(int x = -1; x <= 1; x++)

for(int y = -1; y <= 1; y++)

if(x == 0 && y == 0) continue; // Skip self

if(map[tx+x, ty+y] == Wall) count++;

Hint 3: Connectivity Perform a Flood Fill starting from a random Floor tile. If any floor tiles remain “unmarked”, they are isolated. Fill them with Walls to ensure the player never spawns in a tiny box.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Generative Algorithms | “Procedural Content Generation in Games” | Ch. 3 |

| State Swapping | “Game Programming Patterns” | Ch. 7 (Double Buffer) |

| Search Algorithms | “Algorithms” | Ch. 4 (Flood Fill/BFS) |

Project 4: The Sliced Dungeon (BSP Rooms)

- Main Programming Language: C#

- Alternative Programming Languages: GDScript, C++

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 2. The “Micro-SaaS / Pro Tool”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Tree Structures / BSP

- Software or Tool: Unity/Godot

- Main Book: “Data Structures for Game Developers” by Allen Sherrod

What you’ll build: A classic “Rooms and Corridors” dungeon. You’ll use a Binary Space Partitioning (BSP) tree to divide the map into rectangles, place a room in each “leaf” rectangle, and connect them with hallways.

Why it teaches PCG: You’ll learn about hierarchical data structures. A dungeon isn’t just a grid; it’s a tree of “Areas” that contain “Rooms”.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Recursive Splitting → Knowing when to stop splitting (Min Room Size).

- Corridor Logic → Connecting “sibling” nodes in the tree to ensure the dungeon is fully connected.

- Tree Traversal → Walking the tree from the bottom up to draw the corridors.

Real World Outcome

A dungeon layout that looks like a structured floor plan. Rooms of varying sizes are connected by straight hallways, ensuring there are no unreachable areas.

Visual Representation:

┌───────────┐ ┌───────────┐

│ │ │ Room B │

│ Room A │───────┤ │

│ │ └─────┬─────┘

└─────┬─────┘ │

│ ┌─────┴─────┐

└─────────────┤ Room C │

└───────────┘

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do I balance randomness with architectural constraints?”

Cellular Automata (Project 3) is too wild for a mansion, a castle, or a laboratory. BSP provides the “structure” that humans build with. You are learning to control chaos.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Binary Trees

- What are “Nodes,” “Leaves,” and “Parents”?

- How do you store a tree in memory?

- Book Reference: “Algorithms” Ch. 3 - Sedgewick

- Recursion

- Writing a function that calls itself to slice the world into smaller and smaller pieces.

- Book Reference: “The Recursive Book of Recursion” - Al Sweigart

- Spatial Partitioning

- Why dividing space makes searching and placement faster.

- Book Reference: “Game Programming Patterns” Ch. 19

Questions to Guide Your Design

- The Stop Condition

- If you keep splitting forever, your rooms will be 1x1 tiles. What is the “Minimum Room Size” constant?

- Split Orientation

- How do you decide whether to split a rectangle Horizontally or Vertically? (Hint: Split along the longer axis to keep rooms square-ish).

- Connectivity

- When do you draw the hallway? (Hint: As you go back up the tree, connect the centers of the two child rectangles).

Thinking Exercise

The Split Ratio

Imagine a rectangle 100 tiles wide. If you split it exactly at 50, every dungeon looks identical. If you split it anywhere between 1 and 99, you get “sliver” rooms. What is the ideal “Random Split Range”? (e.g., between 30% and 70% of the width).

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is a Binary Space Partitioning tree?”

- “How do you ensure a BSP-generated dungeon is fully traversable?”

- “What are the trade-offs between BSP and Cellular Automata for level design?”

- “How do you handle ‘Dead Ends’ in a dungeon generator?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: The Leaf Class

Create a Leaf class that has Rect (x, y, w, h). It should have two properties: leftChild and rightChild of type Leaf.

Hint 2: Recursive Splitting

void Split() {

if (width > max_size || height > max_size) {

// Choose H or V

// Split into leftChild and rightChild

// Call leftChild.Split() and rightChild.Split()

}

}

Hint 3: Corridor Strategy The most reliable way to connect the dungeon is to iterate through your leaf nodes and draw a path to their “sibling” leaf. Since they share a parent, they are physically adjacent!

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Hierarchical Structures | “Data Structures for Game Developers” | Ch. 5 |

| Recursion Mastery | “The Recursive Book of Recursion” | All |

| Spatial Patterns | “Game Programming Patterns” | Ch. 19 |

Project 5: The Infinite Noise (Perlin Terrain)

- Main Programming Language: C#

- Alternative Programming Languages: GDScript, C++

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Math / Perlin Noise

- Software or Tool: Unity/Godot

- Main Book: “The Nature of Code” by Daniel Shiffman

What you’ll build: A terrain generator that allows for infinite scrolling. As the player moves, new chunks of terrain are generated using Perlin Noise. You will implement “Biomes” based on height thresholds.

Why it teaches PCG: This introduces Continuity. Unlike the discrete dungeons of Projects 3 and 4, this world is a mathematical function: Height = f(x, y, seed).

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Chunk Management → How to generate and “unload” pieces of the world so you don’t run out of memory.

- Octaves and Persistence → Layering noise to make it look like real mountains rather than smooth blobs.

- Seams → Ensuring that Chunk (0,0) and Chunk (1,0) align perfectly at the edges.

Real World Outcome

A window where you can “fly” or walk over an endless landscape. The terrain looks natural, with clusters of islands, continents, and mountains. As you move, the world generates ahead of you and disappears behind you.

Height Mapping (Biomes):

Height < 0.3: Deep Water (Blue)0.3 < Height < 0.4: Sand (Yellow)0.4 < Height < 0.7: Grass/Forest (Green)0.7 < Height < 0.9: Rock (Grey)Height > 0.9: Snow (White)

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How can I calculate the terrain at (1,000,000, 1,000,000) without calculating everything in between?”

This is the “Lazy Evaluation” of worlds. If the math is consistent, the world exists even if it hasn’t been generated yet.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Gradient Noise (Perlin vs. Simplex)

- Why simple

Random.Next()creates “White Noise” and why Perlin creates “Coherent Noise.” - Book Reference: “The Nature of Code” Ch. 0 - Daniel Shiffman

- Why simple

- Fractal Brownian Motion (fBm)

- The concept of “Octaves.” High frequency (small details) layered over low frequency (large shapes).

- Book Reference: “The Nature of Code” (Noise section)

- Floating Point Precision

- What happens when your

xcoordinate gets so large that the math becomes “choppy”? (The Far Lands).

- What happens when your

Questions to Guide Your Design

- The Scale Variable

- How does the “zoom level” affect the terrain? (Hint:

Noise(x / scale, y / scale)).

- How does the “zoom level” affect the terrain? (Hint:

- Seam Management

- How do you ensure that two different “Chunks” (e.g. 16x16 grids) share the same values at their borders? (Hint: Use global coordinates in your noise function).

Thinking Exercise

The Octave Layering

Imagine a wave with a height of 100 meters. Now add a wave with a height of 10 meters on top of it. Now add a wave with a height of 1 meter on top of that. Draw the resulting profile. This is how you make a “mountain” look jagged rather than like a smooth hill.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is the difference between Perlin Noise and White Noise?”

- “How do you achieve ‘Infinite’ generation without storing the whole map?”

- “What are ‘Octaves’ in the context of noise functions?”

- “How do you handle biomes using noise?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: The Function

In Unity, use Mathf.PerlinNoise(x, y). In Godot, use FastNoiseLite. Note that these functions return a value between 0.0 and 1.0.

Hint 2: Using the Seed

To use your seed, simply offset your coordinates: Noise((x + seedOffset), (y + seedOffset)). As long as the offset is the same, the world is the same.

Hint 3: Chunking Logic

Create a Dictionary<Vector2Int, Chunk>. Every frame, check which chunk the player is in. If the neighboring chunks (N, S, E, W) don’t exist in the dictionary, create them. If a chunk is too far away, Destroy() or Disable() it.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Noise and Randomness | “The Nature of Code” | Ch. 0 |

| Procedural Environments | “Procedural Content Generation in Games” | Ch. 4 |

| Optimization | “Game Programming Patterns” | Ch. 15 (Service Locator) |

Project 6: The Intelligent Stalker (A* Pathfinding)

- Main Programming Language: C#

- Alternative Programming Languages: GDScript, C++

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: AI / Algorithms

- Software or Tool: Unity/Godot

- Main Book: “Artificial Intelligence for Games” by Millington

What you’ll build: An enemy that follows the player through your procedurally generated cave (Project 3). The enemy must navigate around walls and find the most efficient path.

Why it teaches AI: PCG creates unpredictable layouts. Your AI cannot be hard-coded; it must “think” about the current grid state.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Priority Queues → Implementing the “Open List” efficiently so the game doesn’t lag when many enemies move.

- Heuristics → Understanding why “Manhattan Distance” is better than “Euclidean” for grid-based roguelikes.

- Dynamic Obstacles → What happens if the player drops a wall or another enemy blocks the path?

Real World Outcome

An enemy (@) that intelligently snakes through a complex maze or cavern to reach the player, never getting stuck on corners or moving into dead ends unless necessary.

Example Output (Console):

[A* Path Calculated]

Start: (2, 2) | Goal: (8, 9)

Path: (2,2) -> (2,3) -> (3,3) -> (4,3) -> (4,4) ... -> (8,9)

Nodes Explored: 42

Time: 0.01ms

Visual Output:

. . . # .

. E ->. .

. # # # .

. . . @ .

# E doesn't just walk into the wall; it calculates the route around it.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do I make an agent ‘see’ the world data I’ve generated?”

AI is just a search problem over the data structure you built in Project 2. You are teaching a computer to “solve” your generated levels.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Dijkstra vs. A*

- Why adding a “Heuristic” makes the algorithm significantly faster for games.

- Book Reference: “Algorithms” Ch. 4 - Sedgewick

- Heuristics (Manhattan vs. Euclidean)

- Why simple

abs(x1-x2) + abs(y1-y2)is the gold standard for grid-based movement.

- Why simple

- Priority Queues (Min-Heaps)

- How to always pick the “cheapest” node to explore next without sorting the list every time.

- Book Reference: “Data Structures the Fun Way” Ch. 8

Questions to Guide Your Design

- The Cost Function

- What if “Mud” tiles cost 2 to enter and “Grass” costs 1? How does A* handle that? (Hint:

g_cost).

- What if “Mud” tiles cost 2 to enter and “Grass” costs 1? How does A* handle that? (Hint:

- Path Refresh Rate

- Does the enemy calculate the path every frame, or only when the player moves? (Hint: Re-calculating only on player movement saves 99% of CPU).

Thinking Exercise

The Obstacle Course

Draw a 5x5 grid. Place a wall in the middle.

Calculate the “Manhattan Distance” from (0,0) to (4,4).

Now, trace the path manually as A* would, calculating f = g + h for each neighbor.

Why does A* explore toward the goal instead of away from it?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is the difference between BFS, Dijkstra, and A*?”

- “Why is A* usually preferred for games?”

- “What happens if your heuristic is ‘over-optimistic’ (admissible)?”

- “How would you optimize pathfinding for 100 simultaneous enemies?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: The Node Struct

Create a PathNode class that stores its worldPos, gCost (distance from start), hCost (distance to goal), and a parent pointer.

Hint 2: The Open List

Use a List<PathNode> for your “Open List” (nodes to check) and a HashSet<Vector2Int> for your “Closed List” (nodes already checked).

Hint 3: Reconstructing the Path

Once the current node == Goal, follow the parent pointers back to the Start. This gives you the path in reverse!

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Pathfinding Theory | “Artificial Intelligence for Games” | Ch. 4 |

| Heap Implementation | “Data Structures the Fun Way” | Ch. 8 |

| Graph Search | “Algorithms” | Ch. 4 |

Project 7: The Loot Roller (Procedural Items)

- Main Programming Language: C#

- Alternative Programming Languages: GDScript, Python

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 2. The “Micro-SaaS / Pro Tool”

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Data Structures / Design Patterns

- Software or Tool: Unity/Godot

- Main Book: “Game Programming Patterns” by Robert Nystrom

What you’ll build: A “Diablo-style” loot generator. Items have a base type (Sword), a prefix (Flaming), and a suffix (of the Whale). Each adds specific stats.

Why it teaches procedurality: PCG isn’t just for maps; it’s for content. This teaches you about Combinatorial Explosion—how 10 prefixes, 10 bases, and 10 suffixes create 1,000 unique items with zero hand-authoring.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Weighted Randomness → Ensuring “Legendary” items are rarer than “Common” ones.

- Stat Calculation → Applying modifiers correctly (e.g., +10 Damage vs +10% Damage).

- Tooltips → Dynamically generating text based on the item’s hidden data.

Real World Outcome

A “Chest” or “Enemy” that, when triggered, generates a random item with a unique name, randomized stats, and a colored rarity label.

Example Output:

> You opened the Ancient Chest!

> Found: "Flaming Dagger of Agility" (Rare)

- Base Damage: 5

- Modifiers: +2 Fire Damage, +10% Attack Speed

- Level Req: 12

> Found: "Rusty Spoon" (Common)

- Base Damage: 1

- Modifiers: -1 Hygiene

- Level Req: 1

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How can I generate 1,000,000 unique items using only 30 lines of configuration?”

This is the power of “Templates.” You are learning to build systems that multiply your creative effort.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Weighted Randomness

- How to make common items appear 90% of the time and epic items 1% of the time.

- Book Reference: “The Nature of Code” Ch. 0 (Probability)

- Data-Driven Design

- Storing your item names and stats in JSON or ScriptableObjects instead of hard-coding them.

- Book Reference: “Game Programming Patterns” Ch. 15 (Data Locality)

- Decorator or Component Pattern

- How to “attach” extra stats to a base item.

- Book Reference: “Game Programming Patterns” Ch. 14 (Component)

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Stacking Modifiers

- If an item has two speed boosts, do they add (+10% + 10% = +20%) or multiply (1.1 * 1.1 = +21%)?

- The “Rarity” Threshold

- How do you decide if an item is “Epic”? Is it based on the number of modifiers, or a separate random roll?

Thinking Exercise

The Multiplier Trap

If an item has “Double Damage” and “Triple Damage”, should it do 5x damage (Additive) or 6x damage (Multiplicative)? Which is easier to balance as a game designer? Why do most modern RPGs (like Path of Exile) prefer Additive stacking for large percentages?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “How do you implement weighted random selection efficiently?”

- “How would you handle localized names (different languages) for procedural items?”

- “Explain the difference between additive and multiplicative stat stacking.”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: The Data Tables

Create three lists: Prefixes (Flaming, Icy), Bases (Sword, Dagger), and Suffixes (of the Bear, of Agility).

Hint 2: Weighting Logic Assign a “Weight” to each item (Common=100, Rare=10, Legendary=1). To pick one, sum the weights (111), pick a random number between 1 and 111, and see which “bucket” it falls into.

Hint 3: String Formatting

Use string.Format("{0} {1} {2}", prefix.Name, baseItem.Name, suffix.Name) to generate the final title.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Procedural Content | “Procedural Generation in Game Design” | Ch. 14 |

| Design Patterns | “Game Programming Patterns” | Ch. 14 (Component) |

| C# Strings/JSON | “C# 12 in a Nutshell” | Ch. 6 |

Project 8: The Turn Keeper (State Machines)

- Main Programming Language: C#

- Alternative Programming Languages: GDScript, C++

- Coolness Level: Level 2: Practical but Forgettable

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Architecture / Game Loop

- Software or Tool: Unity/Godot

- Main Book: “Game Programming Patterns” by Robert Nystrom

What you’ll build: A robust Turn-Based System. The player moves, then all enemies move, then environmental effects happen. The game must “wait” for the player’s input before continuing.

Why it teaches roguelikes: This is the “Boring but Vital” part. Without a clean state machine, your roguelike will have bugs where enemies move twice, players act during animations, or events trigger out of order.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- State Transitions → Moving from

PLAYER_TURNtoENEMY_TURNonly after all animations have finished. - Input Blocking → Ensuring the player can’t spam keys to move 10 times in a single frame.

- Action Queuing → Handling simultaneous events (e.g., two enemies attacking at the same time).

Real World Outcome

A game that feels “crisp.” You press a key, your character moves, the enemy takes a step toward you, and the game waits for your next move. No overlapping turns or “frozen” states.

Turn Cycle Logic:

- Awaiting Input: Game waits for player to press a key.

- Player Action: Player moves/attacks.

- Enemy Turn: All enemies calculate and execute their move.

- Environment Phase: Poison ticks, fires spread, etc.

- Back to 1.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do I control the flow of time in a discrete, step-by-step world?”

Most games run at 60 FPS. A turn-based game runs at the “Speed of Choice.” You are learning to decouple the game logic from the frame rate.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Finite State Machines (FSM)

- What are States, Transitions, and Commands?

- Book Reference: “Game Programming Patterns” Ch. 7

- The Command Pattern

- Encapsulating an action (like “MoveNorth”) as an object so it can be delayed or undone.

- Book Reference: “Game Programming Patterns” Ch. 1

- Asynchronous Execution (Coroutines/Tasks)

- How to “wait” for a walk animation to finish before starting the next turn.

Questions to Guide Your Design

- The Turn Order

- Who goes first? Is it always the player? Or is there an “Initiative” or “Speed” stat?

- Animation vs. Logic

- If a fireball takes 1 second to travel, when does the damage happen? At the start of the turn or when the fireball “hits”?

Thinking Exercise

The Simultaneous Move

Two characters are 1 tile apart. They both decide to move into the SAME tile at the same time. How does your state machine handle this?

- Does the faster one get it?

- Do they both fail?

- Does the game crash? Design a “Conflict Resolution” rule.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is a State Machine and why is it useful in game development?”

- “How do you handle animations in a turn-based system?”

- “How would you implement ‘Speed’ (where some actors act faster than others)?”

- “Explain the ‘Command Pattern’ in the context of player actions.”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: The Enum

Define your states: enum GameState { PlayerTurn, EnemyTurn, Processing, Waiting }.

Hint 2: Transition Logic

Only allow input if the state is PlayerTurn. Once a valid move is made, switch the state to Processing.

Hint 3: The Enemy Loop

Don’t use a foreach loop that executes instantly. Use a system that triggers each enemy’s AI one by one, waiting for their “Action Finished” signal before moving to the next one.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| State Machines | “Game Programming Patterns” | Ch. 7 |

| Command Pattern | “Game Programming Patterns” | Ch. 1 |

| Architecture | “Clean Code” | Ch. 3 (Functions) |

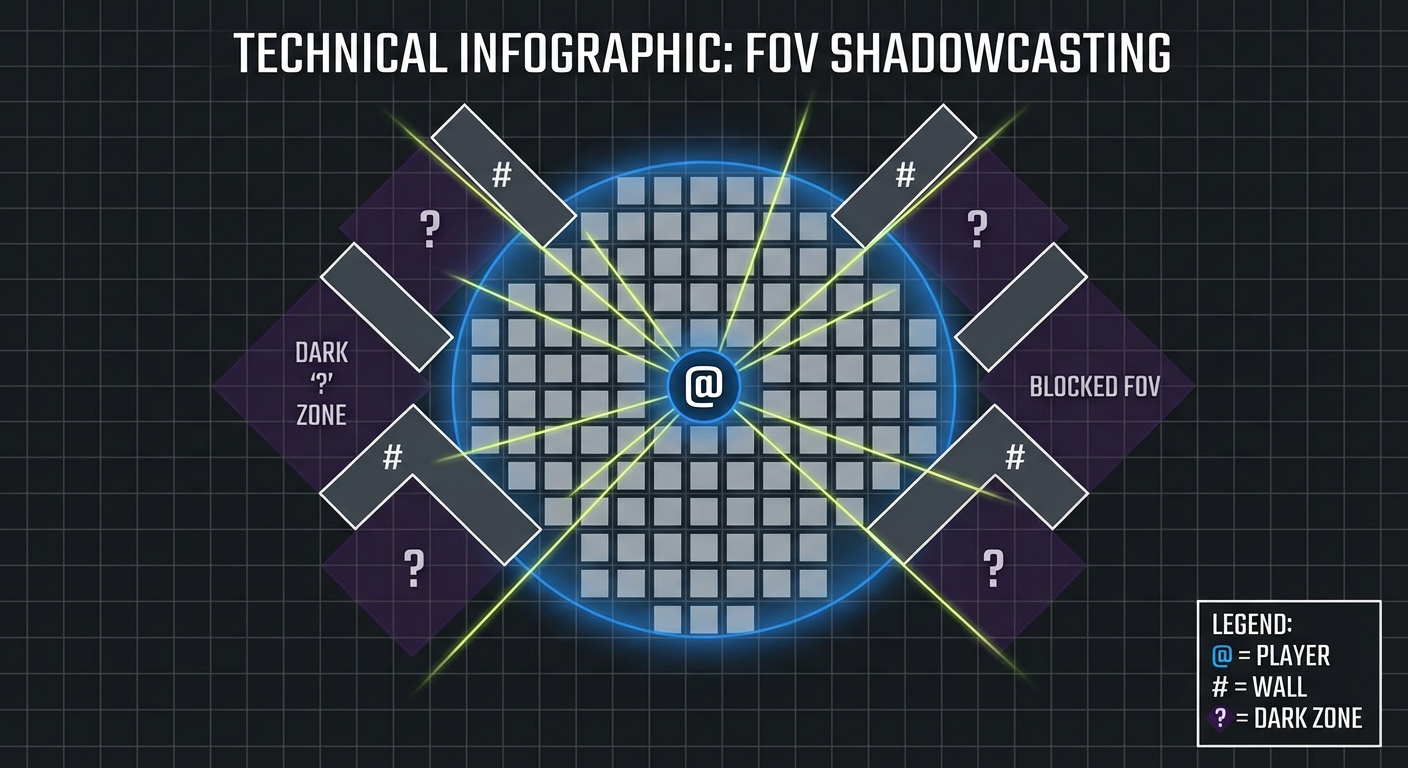

Project 9: The Shadow Caster (Field of View)

- Main Programming Language: C#

- Alternative Programming Languages: GDScript, C++

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Geometry / Raycasting

- Software or Tool: Unity/Godot

- Main Book: “Roguelike Development with Python” (Tutorial Concept)

What you’ll build: A “Field of View” (FOV) system. The player can only see tiles that have a clear line-of-sight. If a wall is in the way, the area behind it is shadowed.

Why it teaches roguelikes: FOV creates tension and mystery. You’ll learn about the intersection of geometry and grid-based data. This is where math meets atmosphere.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Symmetry → If I can see the Orc, can the Orc see me? (Symmetric Shadowcasting).

- Efficiency → Re-calculating FOV every move without dropping the frame rate.

- Corner Cases → Can you see “through” the crack where two walls meet at a diagonal?

Real World Outcome

A circle of “light” centered on the player that updates dynamically as you move. Areas outside the line-of-sight are hidden (black) or dimmed (remembered).

Visual Logic:

. . # ? ?

. . # ? ?

. @ # X ?

# Areas marked with '?' are hidden because the wall '#' blocks the ray from '@'.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do I simulate the physics of light using discrete grid tiles?”

Light travels in straight lines, but your world is made of squares. You need to reconcile these two realities.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Raycasting Fundamentals

- How to draw a line between two points on a grid and identify every tile the line crosses.

- Book Reference: “Bresenham’s Algorithm” - Wikipedia / “Computer Graphics from Scratch”

- Recursive Shadowcasting

- Dividing the world into 8 octants and “scanning” them to find visible slopes.

- Book Reference: “Procedural Content Generation in Games” Ch. 4 (Visibility)

- Slope Calculations

- Understanding how to block ranges of angles (slopes) as the algorithm scans outward.

Questions to Guide Your Design

- The Radius

- How far should the player see? Is there a “Falloff” where things get darker at the edge?

- Persistence

- Should tiles that were once visible stay “Explored” (grayed out) or go back to pitch black?

Thinking Exercise

Bresenham vs. Recursive Shadowcasting

Bresenham: Draw a line to every tile on the edge of the screen. If it hits a wall, stop. Recursive Shadowcasting: Treat the world as “Octants” (pie slices) and scan outward. Which one is “leakier” at the corners? Which one handles large distances better? (Hint: Bresenham is easier to code but often leaves “holes” or “blind spots”).

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “Explain the difference between Raycasting and Shadowcasting.”

- “Why is FOV performance-critical in a roguelike with many entities?”

- “How do you handle ‘peek-around’ corners in a grid system?”

- “What is Symmetric Shadowcasting?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with Bresenham

The easiest way to start is to loop through all tiles within a Radius and use Bresenham’s line algorithm to check if there is a wall between the player and that tile.

Hint 2: Recursive Octants If you want to be professional, research “Recursive Shadowcasting.” It only visits each visible tile once, making it much faster. It works by processing one octant at a time (0° to 45°).

Hint 3: The Visibility Flag

In your Tile class, add a bool isVisible and a bool isExplored. Update these every time the player moves.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Visibility Algorithms | “Procedural Content Generation in Games” | Ch. 4 |

| Geometry and Grids | “Computer Graphics from Scratch” | Ch. 1-2 |

| Algorithm Performance | “Algorithms” | Ch. 1 |

Project 10: The Brain Tree (Behavior Trees)

- Main Programming Language: C#

- Alternative Programming Languages: GDScript, C++

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: AI Architecture

- Software or Tool: Unity/Godot

- Main Book: “Artificial Intelligence for Games” by Millington

What you’ll build: A complex AI using a Behavior Tree. The entity shouldn’t just chase you. It should have priorities: If HP < 20% -> Heal; Else If Player Close -> Attack; Else -> Patrol.

Why it teaches AI: Simple State Machines (Project 8) get messy when you have dozens of states. Behavior Trees are composable, hierarchical, and reactive, allowing for complex, readable AI that is easy to debug and expand.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Selector vs. Sequence → Understanding the difference between “Do the first thing that works” and “Do all these things in order.”

- Conditionals → Building nodes that check game state (e.g.,

IsPlayerInRange,IsHealthy). - Tick Rate → Running the tree logic efficiently within your turn-based system.

Real World Outcome

An enemy that feels “alive” and tactical. Instead of walking into your sword, it might retreat to find a health potion, call for reinforcements if it sees you, or use a defensive stance when its shield is low.

Behavior Tree Visual Logic:

Root (Selector)

├── Sequence (Survival)

│ ├── Condition: IsHP_Low?

│ └── Action: Retreat_to_Safety

├── Sequence (Attack)

│ ├── Condition: IsPlayerInRange?

│ └── Action: AttackPlayer

└── Action: Idle_Patrol

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do I create complex behavior that is still easy for a human to read and modify?”

If you use if/else for everything, your AI will eventually break. Behavior Trees provide a “visual language” for intelligence.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Tree Traversal (Tick)

- How a signal “pulses” through the tree to find the current active action.

- Book Reference: “Artificial Intelligence for Games” Ch. 5.4

- Node Status (Success, Failure, Running)

- Why every node must report back its status to the parent.

- Book Reference: “Behavior Trees in Robotics and AI” - Colledani

- Composite Nodes (Selectors/Sequences)

- Selector: The “OR” gate. It tries children until one succeeds.

- Sequence: The “AND” gate. It tries children until one fails.

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Interruption

- If the AI is “Patrolling” and the player appears, how does the tree switch to “Attack” instantly? (Hint: The tree re-ticks from the root every turn).

- Shared State (Blackboards)

- Where do nodes store data like

targetEnemy? (Hint: Use a “Blackboard” object shared by all nodes).

- Where do nodes store data like

Thinking Exercise

The Healer’s Choice

Imagine a Healer AI. Goal 1: Heal self if low HP. Goal 2: Heal ally if ally low HP. Goal 3: Attack enemy. Draw the Behavior Tree for this. Where do you place the “Heal self” node? At the far left (highest priority) or far right? Why?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is the difference between a Finite State Machine and a Behavior Tree?”

- “Explain what a ‘Decorator’ node does in a Behavior Tree.”

- “How do you handle ‘Running’ states for actions that take multiple turns?”

- “Why are Behavior Trees better for large-scale games like Halo or Spore?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: The Node Interface

Create an abstract class BTNode with a public abstract NodeStatus Tick();.

Hint 2: The Selector Node

A Selector loops through children. If a child returns SUCCESS, the Selector immediately returns SUCCESS. If it returns FAILURE, it moves to the next child.

Hint 3: The Blackboard

Create a Dictionary<string, object> class called Blackboard. Pass this into the Tick() method so nodes can read and write game data (like PlayerPosition).

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| AI Architectures | “Artificial Intelligence for Games” | Ch. 5.4 |

| Advanced BTs | “Behavior Trees in Robotics and AI” | Ch. 1-3 |

| Logic Composition | “Clean Code” | Ch. 10 (Classes) |

Project 11: The Endless Save (Serialization)

- Main Programming Language: C#

- Alternative Programming Languages: GDScript, C++, Python

- Coolness Level: Level 2: Practical but Forgettable

- Business Potential: 3. The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Data Persistence

- Software or Tool: JSON, Protobuf, or Binary Serialization

- Main Book: “Code Complete, 2nd Edition” - Steve McConnell

What you’ll build: A system that saves the entire state of your procedural world. Because the world is generated, you only need to save the Seed and any Changes the player made (the “Delta”).

Why it teaches PCG: This forces you to distinguish between “Generated Data” (calculable) and “Modified Data” (unique). Saving every tile in an infinite world is impossible; saving the differences is engineering mastery.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Deterministic Drift → If you save the seed but change your code, the world will load differently. How do you version your generator?

- Entity Identification → How do you uniquely identify a procedural monster so you can save its current HP?

- File Size → Using binary formats instead of JSON for large maps.

Real World Outcome

A “Save & Load” system where a player can exit an infinite world and return to the exact same spot with the same inventory, the same dead monsters, and the same opened chests.

Storage Strategy:

world_seed: 84920generator_version: 1.2player_pos: (120, 450)modified_tiles: {(120, 451): “BrokenWall”, (10, 10): “Hole”}entities: { “Orc_72”: { “HP”: 5, “Pos”: (12, 5) } }

The Core Question You’re Answering

“If a tree falls in a procedural forest and I’m not there to see it, does it stay fallen when I come back?”

This is the challenge of “Permanence” in an infinite world. You are learning to separate “Function” from “State.”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Serialization vs. Deserialization

- Turning a complex object in RAM into a string of bytes on a disk.

- Book Reference: “C# 12 in a Nutshell” Ch. 15

- The Delta Pattern

- Only saving what has changed from the default generated state.

- Book Reference: “Clean Code” Ch. 6 (Data Structures)

- UIDs (Unique Identifiers)

- Giving every procedural monster a persistent ID based on its spawn coordinates.

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Versioning

- If you update your BSP algorithm (Project 4), how do you prevent old save files from “exploding” or loading rooms into solid walls?

- Large Scale Data

- If a player explores 1,000,000 chunks, your “Delta” file might get huge. How do you compress it? (Hint: Use binary writer instead of text).

Thinking Exercise

The Seed + Delta Strategy

You have an infinite world (Seed: 42).

The player digs a hole at (10, 10).

The player moves 10 miles away. The hole is unloaded from RAM.

The player comes back.

How does the game know there is a hole at (10, 10) if the generator says there is solid ground?

(Design the lookup logic: GetTile(pos) => DeltaMap.Contains(pos) ? DeltaMap[pos] : Generator.Generate(pos)).

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “Why is it inefficient to save every tile in a procedural world?”

- “How do you handle breaking changes in your procedural generator between game updates?”

- “What is the difference between shallow and deep serialization?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: The Delta Dictionary

Create a Dictionary<Vector2Int, TileType> modifiedTiles. When a tile is changed, add its coordinate and new type to this dictionary.

Hint 2: The ID Generator

For enemies, generate an ID using their starting coordinate: ID = string.Format("Mob_{0}_{1}", startX, startY). This ID will be the same every time the seed is loaded.

Hint 3: BinaryFormatter (or similar)

Avoid JSON for large maps. Use BinaryWriter to write raw integers and floats to a .dat file. It’s 10x smaller and 100x faster.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Data Persistence | “C# 12 in a Nutshell” | Ch. 15 |

| Reliable Systems | “Code Complete, 2nd Edition” | Ch. 8 |

| Architectural Design | “Clean Code” | Ch. 6 |

Project 12: The Voxel World (3D Procedurality)

- Main Programming Language: C#

- Alternative Programming Languages: C++, Rust

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 5. The “Industry Disruptor”

- Difficulty: Level 4: Expert

- Knowledge Area: 3D Graphics / Voxel Data

- Software or Tool: Unity/Godot (Mesh Generation)

- Main Book: “Computer Graphics from Scratch” by Gabriel Gambetta

What you’ll build: A basic 3D “Minecraft-style” chunk. Instead of a 2D grid, you’ll use a 3D array of bytes. You’ll use 3D Perlin Noise to generate hills, caves, and overhangs.

Why it teaches PCG: This is the leap from 2D to 3D. You’ll learn about Mesh Generation—creating triangles and vertices via code rather than importing models.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Greedy Meshing → Optimizing the mesh so you don’t draw the “internal” faces of cubes that no one sees.

- 3D Noise →

Noise(x, y, z)allows for tunnels and floating islands, which 2D heightmaps cannot do. - Performance → Managing 16x16x16 blocks (4,096 blocks) per chunk efficiently.

Real World Outcome

A 3D environment you can walk around in (First Person), with rolling hills, deep vertical caves, and floating islands—all generated from a single seed and rendered as a single optimized mesh.

Voxel Metrics:

- Chunk Size: 16x16x16

- Triangles per Block: 2 per face (12 total if isolated)

- Optimized Triangles: ~50% reduction by hiding internal faces.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do I turn raw volume data into a visual 3D mesh?”

A voxel world isn’t made of thousands of Cube objects; that would kill the GPU. It is one single “shape” that is calculated on the fly. You are learning the math of 3D rendering.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- The 3D Coordinate System

- Understanding

(x, y, z)and how to map a 3D index to a 1D array:index = x + (y * width) + (z * width * height). - Book Reference: “Computer Graphics from Scratch” Ch. 1

- Understanding

- Mesh Anatomy

- Vertices (points), Triangles (indices), and Normals (direction).

- Book Reference: “Computer Graphics from Scratch” Ch. 2

- Face Culling

- The logic of “If there is a block to my left, don’t draw my left face.”

Questions to Guide Your Design

- 3D Noise Threshold

- In 2D, noise = height. In 3D, noise = density. If

Noise(x,y,z) > 0.5, is there a block there? - How do you make the density decrease as

yincreases (to prevent infinite floating islands)?

- In 2D, noise = height. In 3D, noise = density. If

- Greedy Meshing

- Can you combine 4 small squares into one large rectangle to save on vertex count?

Thinking Exercise

The Invisible Face

Draw two cubes side-by-side. List all 12 faces. Now, identify which faces are “touching.” Why is it critical for performance to NOT send those touching faces to the Graphics Card? (Think about overdraw and vertex buffers).

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is the difference between a 2D Heightmap and 3D Voxel noise?”

- “How do you optimize 3D mesh generation for millions of voxels?”

- “Explain the ‘Marching Cubes’ algorithm (at a high level).”

- “How do you handle lighting in a voxel world (Vertex Colors vs. Textures)?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: The Data Structure

Use byte[,,] blocks = new byte[16, 16, 16]. 0 = Air, 1 = Stone.

Hint 2: Mesh Generation

Create a List<Vector3> vertices and List<int> triangles. Loop through every block. For each block, check its 6 neighbors. If a neighbor is “Air”, add the 4 vertices of that face to your list.

Hint 3: 3D Perlin

Most libraries only have 2D Perlin. You can simulate 3D by “layering” 2D noise or finding a dedicated library like FastNoiseLite.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| 3D Fundamentals | “Computer Graphics from Scratch” | Ch. 1-3 |

| Voxel Optimization | “Game Programming Patterns” | Ch. 21 (Spatial Partition) |

| C++ Performance | “Write Great Code, Vol 2” | Ch. 11 |

Project 13: The Dynamic Ecosystem (Agent Interaction)

- Main Programming Language: C#

- Alternative Programming Languages: GDScript, Python

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Systems Design / Emergence

- Software or Tool: Unity/Godot

- Main Book: “Procedural Generation in Game Design” by Short — Ch. 18

What you’ll build: A world where enemies interact with each other, not just the player. Goblins attack Wolves; Wolves hunt Rabbits; Rabbits eat procedurally generated grass.

Why it teaches PCG: This is Emergent Gameplay. You don’t script a fight; you give agents goals, and a fight “happens” because their goals conflict. You are building a simulation, not just a level.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Faction Systems → Managing relationships (Friend/Neutral/Foe) between 10+ species.

- Sensory Systems → “Sight” and “Smell” for animals so they can find food or avoid predators.

- Resource Depletion → If wolves eat all the rabbits, what happens to the wolves? (Population dynamics).

Real World Outcome

A “Living World” log or visual debug view where you can watch a goblin camp clear out a nearby wolf den without any player intervention. The map changes as resources are consumed and species migrate.

Ecosystem Log:

[Day 1, 12:00] Rabbit_A ate Grass at (10, 5).

[Day 1, 14:30] Wolf_B spotted Rabbit_A. Entering 'Hunt' mode.

[Day 1, 14:32] Wolf_B killed Rabbit_A.

[Day 2, 08:00] Goblin Patrol spotted Wolf_B. Entering 'Combat' mode.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do I make a world feel alive even when the player isn’t looking?”

Most games are static “museums” waiting for the player to walk through. A roguelike ecosystem is a “simulation” that exists for its own sake. You are learning “Systemic Design.”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Utility AI

- Scoring different actions based on needs (e.g., Hunger=90, Danger=10 -> Priority: Eat).

- Book Reference: “Artificial Intelligence for Games” Ch. 5.3

- Emergence

- How simple behaviors (Chase, Flee, Eat) create complex, unscripted stories.

- Book Reference: “Procedural Generation in Game Design” Ch. 18

- Spatial Hashing

- How an entity quickly finds the “closest rabbit” without checking every object in the world.

- Book Reference: “Game Programming Patterns” Ch. 19

Questions to Guide Your Design

- The Hunger Clock

- If you don’t eat for 100 turns, do you die? If so, does your body become “Meat” (a resource) for others?

- Perception Radius

- How do you simulate “Smell”? (Hint: A search that ignores walls/obstacles but has a larger radius than Sight).

Thinking Exercise

The Wolf-Rabbit Balance

If Rabbits reproduce every 50 turns and Wolves need to eat every 20 turns, will the population be stable? Trace a 100-turn simulation on paper. What happens if you introduce a “Hunter” (the player) into this balance?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is Emergent Gameplay and how do you design for it?”

- “How do you handle AI performance for 1,000+ interacting agents?”

- “Explain the difference between scripted behavior and systemic behavior.”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: The Goal Enum

Each agent should have a currentGoal (Idle, Hunt, Eat, Sleep, Flee).

Hint 2: Simple Utility

Every turn, calculate a “Desire Score” for each goal. HungerScore = currentHunger / maxHunger. The AI picks the goal with the highest score.

Hint 3: Faction Matrix

Use a 2D array or a Dictionary<Species, Dictionary<Species, float>> to store “Friendship” levels. If Relation[Goblin, Wolf] < -0.5, they attack on sight.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Emergent Systems | “Procedural Generation in Game Design” | Ch. 18 |

| Decision Making | “Artificial Intelligence for Games” | Ch. 5 |

| Systemic Optimization | “Game Programming Patterns” | Ch. 19 |

Project 14: The Rule-based Quest (Grammar Narrative)

- Main Programming Language: C#

- Alternative Programming Languages: Python, GDScript

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 2. The “Micro-SaaS / Pro Tool”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: NLP / Generative Text

- Software or Tool: Tracery or custom Grammar Engine

- Main Book: “Procedural Generation in Game Design” by Short — Ch. 8

What you’ll build: A procedural quest generator. It uses a formal grammar to build logical objectives: [Subject] needs [Object] from [Location] because [Motivation].

Why it teaches PCG: It moves procedurality into the realm of Narrative. You’ll learn about Context-Free Grammars (CFG) and how to ensure quests are not just random text but are logically tied to the game world.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Logic Constraints → Ensuring the “Lost Cave” actually exists in your generated map before assigning a quest there.

- Recursive Substitution → Building complex sentences from simple rules.

- Quest Chaining → One quest leading to another (e.g., getting the Ring requires a Key from a different quest).

Real World Outcome

A “Quest Board” in your game that generates unique, logical tasks every time you visit town. Each quest includes a title, a description, and a set of trackable objectives.

Example Quests:

- “The Mayor needs a Golden Ring from the Spider Cave because he wants to propose to the Blacksmith.”

- “A local Farmer needs a Magic Scythe from the Ruined Tower because his crops are possessed.”

- “The Guard Captain needs 10 Orc Ears from the Northern Woods to prove the threat is real.”

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do I turn ‘random strings’ into ‘meaningful stories’?”

A quest is just a data structure. You are learning to use “Generative Grammars” to create infinite writing.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Context-Free Grammars (CFG)

- Understanding non-terminal vs. terminal symbols.

- Book Reference: “Procedural Generation in Game Design” Ch. 8

- Graph-based Quests

- Visualizing a quest as a flow:

Unlock Door -> Kill Boss -> Get Loot. - Book Reference: “Procedural Content Generation in Games” Ch. 9 (Narrative)

- Visualizing a quest as a flow:

- Substitution Engines

- How libraries like Tracery work.

Questions to Guide Your Design

- World Consistency

- How do you prevent the generator from saying “Kill the Dragon” if the game only has Goblins?

- Motivation vs. Action

- Does the “Motivation” (e.g., “to pay off a debt”) change the “Action” (e.g., “Steal” vs “Kill”)?

Thinking Exercise

The Recursive Quest

Start with: [Objective].

Rule 1: [Objective] -> [Action] the [Target].

Rule 2: [Action] -> Retrieve, Destroy, or Protect.

Rule 3: [Target] -> [Item] or [Person].

Follow these rules 3 times. How many unique “Objective” strings can you create?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is a Context-Free Grammar?”

- “How do you ensure a procedurally generated quest is actually completable?”

- “How would you integrate a quest generator with a procedural map generator?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: The Dictionary of Lists

Create a Dictionary<string, List<string>> where the key is the category (e.g., “hero”) and the list contains options (e.g., “Knight”, “Mage”).

Hint 2: Recursive Replacement

Write a function Expand(string input) that finds any text inside {braces}, looks it up in your dictionary, picks a random value, and calls Expand() on that value.

Hint 3: Data Integrity

When picking a [Location], don’t pick a random string. Pick a random Room object from your BSP tree (Project 4) and use its name property. This guarantees the place exists.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Narrative Generation | “Procedural Generation in Game Design” | Ch. 8 |

| Formal Grammars | “Introduction to the Theory of Computation” | Ch. 2 |

| Logic in Games | “Game Programming Patterns” | Ch. 15 |

Project 15: The Procedural Soundscape (Generative Audio)

- Main Programming Language: C#

- Alternative Programming Languages: C++ (SuperCollider/PureData)

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 2. The “Micro-SaaS / Pro Tool”

- Difficulty: Level 4: Expert

- Knowledge Area: Digital Signal Processing (DSP)

- Software or Tool: Unity (OnAudioFilterRead) or Godot (AudioStreamGenerator)

- Main Book: “The Theory and Technique of Electronic Music” by Miller Puckette

What you’ll build: Music and ambience that changes based on the game state. If you are in a “Cave”, the music is low and echoey. If you find “Gold”, a bright chord plays.

Why it teaches PCG: Audio is just another data stream. This teaches you how to map game state (HP, Location, Danger Level) to audio parameters (Pitch, Tempo, Reverb, Oscillators). You are learning “Algorithmic Composition.”

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Buffer Management → Writing raw sine/square wave data to the audio card without “popping” noises.

- Musical Theory → Ensuring that procedural notes stay within a specific scale (e.g., C-Minor) so it doesn’t sound like random noise.

- Dynamic Mixing → Fading between a “Safe” track and a “Combat” track seamlessly.

Real World Outcome

A game where the music literally “reacts” to your gameplay in real-time. Running low on health makes the music more frantic (higher tempo); entering a boss room makes it deeper (lower octave); picking up a legendary item triggers a harmonized fanfare.

Audio Mapping:

- Biome: Cave -> High Reverb, Low-frequency drone.

- Danger Level: High -> 140 BPM, Minor Scale.

- Danger Level: Low -> 80 BPM, Major Scale.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do I turn game data into sound waves?”

Most games use static .wav files. You are learning to build a “Synthesizer” that lives inside your game engine.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Sine Waves & Oscillators

- How a mathematical function

sin(time * frequency)creates a pitch. - Book Reference: “The Theory and Technique of Electronic Music” Ch. 1

- How a mathematical function

- The Audio Buffer

- Why sound must be calculated in small “chunks” (usually 512 or 1024 samples).

- Book Reference: “Real-Time Audio Programming” - Digital Signal Processing (DSP)

- Music Theory for Programmers

- Mapping an integer (0-11) to a scale so your “Random” notes always sound musical.

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Synthesis vs. Sample Logic

- Will you generate raw waves from scratch, or “re-pitch” existing recordings?

- The “Hitch” Problem

- If your audio calculation takes too long, the sound will “crackle.” How do you optimize your math?

Thinking Exercise

The Frequency Double

If a note is 440Hz (A4), what is the frequency of the same note one octave higher?

Why does the human ear hear “Doubling the Frequency” as “The same note, but higher”?

(Hint: This logarithmic relationship is why log2(freq) is so common in audio code).

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is an Audio Buffer and why do we need one?”

- “How do you prevent ‘audio clipping’ when playing multiple sounds at once?”

- “Explain how you would map a ‘Fear’ level to a procedural melody.”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: The Basic Oscillator

In Unity’s OnAudioFilterRead(float[] data, int channels), fill the data array with a simple sine wave: Mathf.Sin(phase). Increment the phase every sample based on your desired frequency.

Hint 2: Scales as Arrays

Create an array int[] cMinor = { 0, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 10 };. To pick a random “good” note, pick a random index from this array and add it to a base MIDI note (e.g., 60).

Hint 3: Smoothing Transitions

Don’t jump from 80 BPM to 140 BPM instantly. Use Mathf.Lerp to gradually change the tempo over several seconds.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Audio Theory | “The Theory and Technique of Electronic Music” | Ch. 1-2 |

| DSP Programming | “Designing Sound” by Andy Farnell | Part II |

| Sound Design | “Procedural Generation in Game Design” | Ch. 22 |

Project 16: The Infinite UI (Dynamic Menus)

- Main Programming Language: C#

- Alternative Programming Languages: GDScript

- Coolness Level: Level 2: Practical but Forgettable

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: UI/UX Architecture

- Software or Tool: Unity (UI Toolkit) / Godot (Control Nodes)

- Main Book: “Code Complete, 2nd Edition” - Steve McConnell

What you’ll build: A dynamic inventory and character sheet. Because items are procedural (Project 7), your UI cannot be static. It must resize, create new text fields, and handle 100+ different possible item stats and names of varying lengths.

Why it teaches PCG: The “Final Mile” of PCG is presentation. If your UI can’t handle the variety of procedural data, the data doesn’t exist to the player. You are learning “Data-Driven UI.”

Core challenges you’ll face: