Learn Post-Quantum Cryptography: From Zero to PQC Master

Goal: Deeply understand the mathematical foundations, cryptographic constructions, and practical implementation challenges of the NIST Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC) standards. You will transition from a consumer of “black-box” crypto to an engineer capable of implementing, optimizing, and auditing quantum-resistant primitives like ML-KEM (Kyber), ML-DSA (Dilithium), and SLH-DSA (SPHINCS+). By the end, you will have built a full PQC-capable library and understood the geometry of high-dimensional lattices.

Why Post-Quantum Cryptography Matters

Modern security rests on a house of cards called “Integer Factorization” and “Discrete Logarithms.” In 1994, Peter Shor proved that a sufficiently large quantum computer could blow this house down in minutes. While such a computer doesn’t exist yet, the threat is already here: “Harvest Now, Decrypt Later.” Adversaries are capturing today’s encrypted traffic, waiting for the day they can unlock it with a quantum machine.

Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC) is the global shift to mathematical problems that even quantum computers find impossible to solve. This isn’t just a “library update”—it’s a fundamental change in how we represent keys, handle noise, and achieve security.

The Looming Threat: Shor’s Algorithm

Classical crypto (RSA, ECC) relies on “one-way” mathematical functions that are easy to do but hard to undo. Shor’s algorithm utilizes quantum superposition and interference to find the “period” of these functions, effectively reversing them.

CLASSICAL THREAT LANDSCAPE:

┌───────────────────┬──────────────────────┬───────────────────────┐

│ Algorithm │ Hard Problem │ Quantum Impact │

├───────────────────┼──────────────────────┼───────────────────────┤

│ RSA │ Factoring N=p*q │ BROKEN (Shor's) │

│ ECC / DH │ Discrete Logarithm │ BROKEN (Shor's) │

│ AES-128 │ Symmetric Search │ WEAKENED (Grover's) │

│ SHA-256 │ Collision Resistance │ NEGLIGIBLE │

└───────────────────┴──────────────────────┴───────────────────────┘

Core Concept Analysis

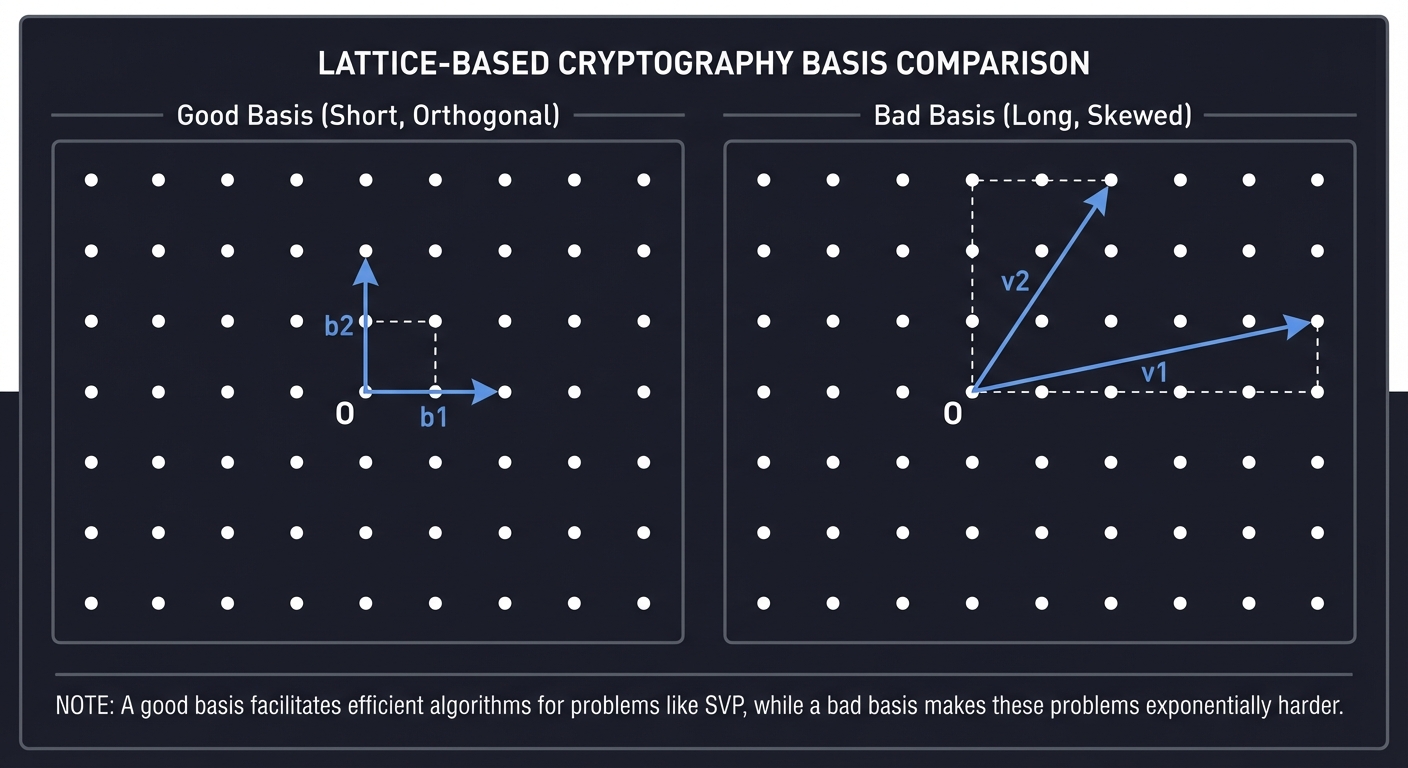

1. Lattice-Based Cryptography: Geometry in High Dimensions

Imagine a grid of points in 1,000+ dimensions. A “lattice” is the set of all integer combinations of some “basis” vectors.

Shortest Vector Problem (SVP): Given a “bad” basis (long, nearly parallel vectors), find the shortest non-zero vector in the lattice.

LATTICE VISUALIZATION (Good Basis vs. Bad Basis)

Good Basis (Short, Orthogonal): Bad Basis (Long, Skewed):

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

. O---> b1 . . . . . . .

. | . . . . O-----------> v1 .

. v b2 . . . \ .

. . . . . \-----> v2 .

In high dimensions, finding the shortest vector given a “bad” basis is exponentially hard. This is the “trapdoor”: the private key is the “good” basis, and the public key is the “bad” basis.

2. Learning With Errors (LWE): Linear Algebra with Noise

LWE is the engine of modern PQC. It’s essentially solving a system of linear equations where a small bit of “noise” is added to each result.

Without Noise (High School Algebra - EASY):

A * s = b

[ 1 2 ] [ s1 ] [ 5 ] => s1 + 2*s2 = 5

[ 3 4 ] * [ s2 ] = [ 11 ] => 3*s1 + 4*s2 = 11

(Easily solved using Gaussian Elimination)

With Noise (LWE - IMPOSSIBLE for computers):

A * s + e = b (mod q)

[ 1 2 ] [ s1 ] [ 1 ] [ 6 ]

[ 3 4 ] * [ s2 ] + [ -1] = [ 10]

Without knowing the noise e or the secret s, finding either is computationally infeasible. Encryption involves adding the message into this “noise” buffer.

3. Polynomial Rings: The CPU of Lattice Crypto

To make PQC efficient, we don’t use raw matrices; we use Polynomial Rings. Instead of multiplying large matrices, we multiply polynomials and “reduce” them modulo a specific polynomial (like x^n + 1) and a prime q.

POLYNOMIAL MULTIPLICATION (Conceptual)

A(x) = 3x^2 + 2x + 1

B(x) = 5x^2 + 1x + 4

A(x) * B(x) = (Product)

Result = (Product) MOD (x^n + 1) <-- Degree Reduction

Result = (Result) MOD q <-- Coefficient Reduction

This “wrapping” behavior is what allows PQC to be fast on modern CPUs using techniques like the Number Theoretic Transform (NTT).

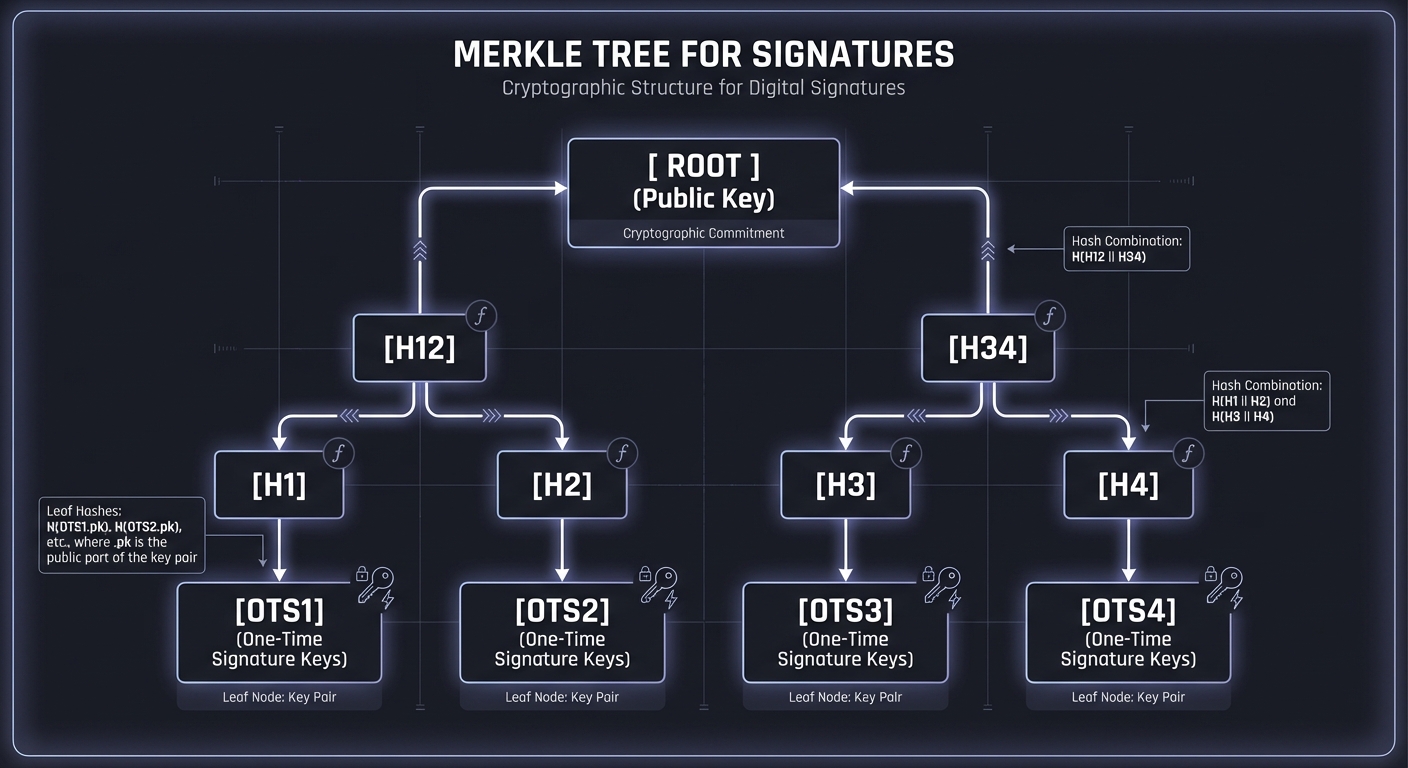

4. Hash-Based Signatures: Merkle Trees & OTS

Hash-based signatures (HBS) rely solely on the security of hash functions like SHA-3. They are “stateless” or “stateful” depending on how they manage many One-Time Signatures (OTS).

MERKLE TREE FOR SIGNATURES

[ ROOT ] (Public Key)

/ \

[H12] [H34]

/ \ / \

[H1] [H2] [H3] [H4]

| | | |

[OTS1][OTS2] [OTS3][OTS4] (One-Time Signature Keys)

To sign a message, you use one OTS key and provide the “authentication path” (the hashes of sibling nodes) to prove that OTS key belongs to the Root.

Concept Summary Table

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize |

|---|---|

| Lattices & SVP | High-dimensional grids. Finding the shortest vector is the core hard problem. |

| LWE & Noise | Adding small errors (e) to linear equations makes them impossible to solve without a secret. |

| Ring Arithmetic | Operations on polynomials mod (x^n + 1, q). This is where 90% of the CPU time goes. |

| Merkle Trees | Hierarchical hashing used to verify that a specific key is part of a larger set. |

| OTS (WOTS+) | Signatures that reveal pieces of a hash chain. Can only be used once safely. |

| Statelessness | Managing massive virtual trees of OTS keys using deterministic addressing. |

| NTT (Number Theoretic Transform) | A “Fast Fourier Transform” for polynomials over finite fields. |

Deep Dive Reading by Concept

Math & Lattices

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Lattice Fundamentals | Post-Quantum Cryptography by Bernstein et al. — Ch. 5 |

| LWE Hardness | Serious Cryptography, 2nd Edition by Aumasson — Ch. 15 |

| Ring Theory | A Course in Computational Algebraic Number Theory by Cohen — Ch. 1 |

Hash-Based Cryptography

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Merkle Trees | Serious Cryptography, 2nd Edition by Aumasson — Ch. 11.2 |

| Hash Functions (SHA-3) | Serious Cryptography, 2nd Edition by Aumasson — Ch. 6 |

| SPHINCS+ / SLH-DSA | NIST FIPS 205 (Standard Specification) |

Implementation & Standards

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| ML-KEM (Kyber) | NIST FIPS 203 |

| ML-DSA (Dilithium) | NIST FIPS 204 |

| Constant-Time Programming | Serious Cryptography, 2nd Edition by Aumasson — Ch. 14 |

Project List

Project 1: Polynomial Arithmetic Engine (The Lattice Core)

- File: LEARN_POST_QUANTUM_CRYPTO.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Knowledge Area: Abstract Algebra / Lattice Cryptography

- Main Book: NIST FIPS 203 (ML-KEM)

What you’ll build: a library that performs modular arithmetic on polynomials—specifically addition and multiplication in the ring $R_q = \mathbb{Z}_q[x] / (x^n + 1)$.

Why it teaches PQC: Almost all lattice-based schemes (Kyber, Dilithium) operate on polynomials. To understand them, you must understand how polynomials wrap around when multiplied (modular reduction) and how their coefficients are constrained by a prime $q$. This is the “CPU” of a lattice scheme.

Real World Outcome

Deliverables:

- Polynomial ring library with add/mul/reduce

- Test harness with known vectors

Validation checklist:

- Reduction matches reference implementation

- Coefficients stay within modulo range

- Multiplication is associative under mod rules

You’ll have a C library that can multiply two polynomials and return the reduced result. This will be the direct dependency for your future Kyber implementation.

Example Output:

$ ./poly_test

Poly A: [1, 2, 3, ... 0]

Poly B: [5, 4, 1, ... 0]

A + B (mod 3329): [6, 6, 4, ... 0]

A * B (mod 3329, x^256 + 1): [Reduced Coefficients]

Verification against reference implementation: SUCCESS

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do we perform multiplication when the result must stay within a fixed-sized ‘box’ of both degree and value?”

Standard algebra allows numbers to grow infinitely. In PQC, we need them to wrap around. Understanding this “wrapping” is the key to understanding how LWE errors are managed.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Modular Arithmetic

- How does

(a * b) % qbehave? - How do you handle negative numbers in modulo? (Hint: Always add

qbefore the final%)

- How does

- Polynomial Reduction

- What happens to $x^n$ in the ring $x^n + 1$? (Hint: it becomes -1).

- Ring Theory Basics

- What is a quotient ring?

- Why do we use $n=256$ and $q=3329$ in Kyber?

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Data Structures

- How will you store a polynomial? (An array of

int16_tis typical for Kyber).

- How will you store a polynomial? (An array of

- Reduction Logic

- When you multiply two polynomials of degree $n-1$, you get a polynomial of degree $2n-2$. How do you map that back to degree $n-1$? (Hint: $x^n = -1 ext{ mod } (x^n+1)$)

- Edge Cases

- What happens if the coefficients overflow a 16-bit or 32-bit integer during intermediate steps?

Thinking Exercise

Trace this on paper for $n=2$ and $q=7$: Ring: $\mathbb{Z}_7[x] / (x^2 + 1)$ $A(x) = 2x + 3$ $B(x) = 4x + 1$

- Compute $A(x) * B(x)$ normally.

- Apply $x^2 = -1$ (which is $x^2 = 6 \pmod 7$).

- Apply modulo $7$ to all coefficients.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “Why do we use $x^n + 1$ as the modulus instead of just $x^n$?”

- “What is the complexity of schoolbook polynomial multiplication vs. NTT?”

- “How do you ensure your polynomial addition is constant-time?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Storage

In C, a polynomial is just an array: int16_t poly[256];. Coefficient i represents the term $x^i$.

Hint 2: Addition

Addition is simple: result[i] = (a[i] + b[i]) % q. Be careful with negative results! Always add q before the final %.

Hint 3: Schoolbook Multiplication

For each coefficient i in A and j in B, the product adds to the i+j index of the result.

If i+j >= n, it wraps around: index i+j - n gets subtracted from ($x^n = -1$).

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Modular Arithmetic | “Serious Cryptography” | Ch. 2 |

| Ring Theory for PQC | “Post-Quantum Cryptography” (Bernstein) | Ch. 5 |

Project 2: SHA-3 (Keccak) from the FIPS 202 Spec

- File: LEARN_POST_QUANTUM_CRYPTO.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Knowledge Area: Hash Functions / Bit-level Permutations

- Main Book: NIST FIPS 202

What you’ll build: A bit-perfect implementation of the Keccak-f[1600] permutation and the SHAKE128/256 extendable output functions.

Why it teaches PQC: Classical SHA-2 is used in some PQC, but the NIST standards (ML-KEM, ML-DSA, SLH-DSA) are built entirely around SHA-3 and SHAKE. You’ll need SHAKE to “expand” small seeds into large matrices of polynomials or WOTS chains.

Real World Outcome

Deliverables:

- SHA-3 CLI supporting SHA3-256/512

- Test vectors from FIPS 202

Validation checklist:

- Matches FIPS 202 test vectors

- Streaming input yields same digest as one-shot

- Rate/capacity parameters are correct

A CLI tool that matches the output of openssl dgst -sha3-256. You will be able to take any string and produce the official SHA-3 hash.

Example Output:

$ echo -n "abc" | ./my_sha3 --256

3a9831518112edb1d7293112107c128f877595696a9e3f4a60143b1718260209

# Using SHAKE128 to generate a random-looking polynomial:

$ ./my_shake128 --seed "0123" --length 16

[ 14 2c 3a 0b f1 ... ]

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do we create an ‘infinite’ stream of random-looking bits from a single small secret?”

In RSA, we just need a few big numbers. In PQC, we need megabytes of “randomness” that both the sender and receiver can derive identically. SHAKE is the faucet that provides this water.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Sponge Construction

- What are the “Rate” and “Capacity”?

- How does “Absorbing” differ from “Squeezing”?

- Keccak State

- How is the 1600-bit state represented as a 5x5x64 array of bits?

- Bitwise Permutations

- Theta, Rho, Pi, Chi, Iota—how do these simple bit shifts create complex entropy?

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Efficiency

- Can you use

uint64_tto represent the “lanes” of the Keccak state?

- Can you use

- Padding

- How does the padding rule (

10*1) work for SHA-3 vs. SHAKE?

- How does the padding rule (

- Endianness

- Keccak uses a specific bit-ordering. How do you map bytes to bits without getting it backwards?

Thinking Exercise

Visualize the 5x5 grid of 64-bit lanes. If you change a single bit in the first lane and run one round of Keccak, how many bits in the grid change? (This is the “Avalanche Effect”).

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is the security difference between SHA-2 and SHA-3?”

- “Why does SHAKE use a ‘Capacity’ that is twice the security level?”

- “How would you implement Keccak on a 32-bit CPU without 64-bit registers?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: The State

Store the state as uint64_t state[25]. This represents the 1600 bits as 25 lanes of 64 bits each.

Hint 2: The Sponge For SHA3-256, the rate is 1088 bits (136 bytes). You XOR your input into the first 136 bytes of the state, then permute.

Hint 3: Round Constants Don’t calculate the Iota round constants on the fly. Hardcode them in an array as per FIPS 202.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Keccak Internals | “Serious Cryptography” | Ch. 6 |

| Sponge Functions | “NIST FIPS 202” | Section 3 |

| Bit Manipulation | “Hacker’s Delight” | Ch. 2 |

Project 3: Winternitz One-Time Signatures (WOTS+)

- File: LEARN_POST_QUANTUM_CRYPTO.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Knowledge Area: Hash-based Signatures

- Main Book: NIST FIPS 205

What you’ll build: An implementation of the WOTS+ signature scheme using your Project 2 hash functions.

Why it teaches PQC: WOTS+ is the atomic unit of the SLH-DSA standard. It teaches you how to sign a message by revealing secret intermediate points in a hash chain. You’ll understand why you can only sign once with a specific key.

Real World Outcome

Deliverables:

- WOTS+ keygen/sign/verify utilities

- Parameterized WOTS+ config file

Validation checklist:

- Sign/verify succeeds on known messages

- Modified message fails verification

- One-time key reuse is detected and blocked

A program that generates a WOTS+ key, signs a hash, and verifies it. You will see that a signature is essentially a collection of values from 67 different hash chains.

Example Output:

$ ./wots_sign --key secret.key --msg "hello"

Signature: [32-byte hash chain end 1] [32-byte hash chain end 2] ...

$ ./wots_verify --pub root.pub --msg "hello" --sig signature.bin

Verification: SUCCESS

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How can I prove I know a secret without revealing the secret itself, using only one-way hash functions?”

Traditional signatures use math like ECC. WOTS+ uses “Hash Chains.” If I show you $H(H(x))$, I’ve proven I know $H(x)$ or $x$ without giving you the full chain.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Hash Chains

- If I give you the 10th value in a chain, can you find the 9th? (No). Can you find the 11th? (Yes).

- WOTS Parameters

- What are

n(hash size) andw(Winternitz parameter)?

- What are

- Checksums

- Why does a WOTS signature need a checksum? (To prevent forging by advancing chains).

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Chain Logic

- How do you apply the “Address” to the hash at each step?

- Digit Mapping

- How do you turn a 32-byte message into a sequence of 4-bit digits?

Thinking Exercise

If you use WOTS to sign twice, why is it broken? Message 1: Digit = 5. Signature = $H^5(x)$. Message 2: Digit = 7. Signature = $H^7(x)$. An attacker now has $H^5(x)$. They can compute $H^6(x)$ and $H^7(x)$ themselves.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is the trade-off between the Winternitz parameter

wand signature size?” - “Why are hash-based signatures considered ‘quantum-resistant’?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: The Chain A chain of length $k$ is $H(H(H(…x…)))$. In WOTS+, each step also XORs a “random” mask derived from the Seed and Address.

Hint 2: The Address

Don’t ignore the Address struct in FIPS 205. It’s critical for security.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Hash-based Signatures | “Post-Quantum Cryptography” (Bernstein) | Ch. 3 |

| SLH-DSA / WOTS+ | “NIST FIPS 205” | Section 3 |

Project 4: Merkle Tree Authenticator

- File: LEARN_POST_QUANTUM_CRYPTO.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Knowledge Area: Data Structures / Authentication

- Main Book: Serious Cryptography Ch. 11

What you’ll build: A generic binary tree hasher that authenticates multiple WOTS+ keys into a single “root” public key.

Real World Outcome

Deliverables:

- Merkle tree builder with auth path output

- Verifier that checks leaf membership

Validation checklist:

- Auth path validates correct leaf

- Tampered auth path is rejected

- Root hash is deterministic for same inputs

A tool that generates a Merkle Root for 1,024 messages. It provides a proof for message #42 that is only ~10 hashes long.

Example Output:

$ ./merkle_tree --leaves 1024

Root: 8f3a...

$ ./merkle_proof --index 42

Leaf 42: abcd...

Proof: [hash1, hash2, ... hash10]

$ ./merkle_verify --root 8f3a... --leaf abcd... --proof [hash1...]

Verification: VALID

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How can I verify one item in a set of a million without downloading the million items?”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Binary Trees

- Hash Combinations

-

$H(L R)$

-

Project 4: Merkle Tree Authenticator

- File: LEARN_POST_QUANTUM_CRYPTO.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Knowledge Area: Data Structures / Authentication

- Main Book: Serious Cryptography Ch. 11

What you’ll build: A generic binary tree hasher that authenticates multiple WOTS+ keys into a single “root” public key.

Why it teaches PQC: In SPHINCS+ (SLH-DSA), we need to handle thousands of one-time keys. We can’t publish thousands of public keys. Instead, we hash them into a Merkle Tree and only publish the Root. To verify a signature, we provide the “Authentication Path”—the minimum set of hashes needed to recompute the Root.

Real World Outcome

Deliverables:

- Merkle tree builder with auth path output

- Verifier that checks leaf membership

Validation checklist:

- Auth path validates correct leaf

- Tampered auth path is rejected

- Root hash is deterministic for same inputs

A tool that generates a Merkle Root for 1,024 messages. It provides a proof for message #42 that is only ~10 hashes long.

Example Output:

$ ./merkle_tree --leaves 1024

Root: 8f3a5b2c...

$ ./merkle_proof --index 42

Leaf 42: abcd1234...

Proof: [h1: 9a2b..., h2: 3f4e..., ... h10: 1c2d...]

$ ./merkle_verify --root 8f3a5b2c... --leaf abcd1234... --proof [h1...]

Verification: VALID

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How can I verify one item in a set of a million without downloading the million items?”

This is the foundation of “Stateless” cryptography. By providing a short proof, you prove membership in a massive set that neither you nor the verifier needs to store in its entirety.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Binary Tree Traversal

- How do you find the sibling of node

iat levelj?

- How do you find the sibling of node

- Hash Domain Separation

- Why do we use different prefixes for leaf nodes vs. internal nodes? (To prevent second-preimage attacks).

- Authentication Paths

- Which nodes are required to compute the path from a leaf to the root?

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Tree Construction

- Should you build the tree from the bottom up or use a recursive approach?

- Memory Efficiency

- If the tree has $2^{20}$ leaves, you can’t store it in RAM. How can you compute the root using only $O(H)$ memory? (Hint: Use a stack).

- Ordering

-

Does it matter if the sibling is on the left or the right? (Yes, $H(L R) \neq H(R L)$).

-

Thinking Exercise

If you have a tree with 8 leaves, draw the tree and highlight the nodes needed to prove leaf #3. How many hashes are in the proof? Now do it for 16 leaves. Notice the logarithmic growth.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is the time complexity of generating a Merkle Proof vs. verifying it?”

- “How do you protect a Merkle Tree against length extension attacks?”

- “Why is the root of a Merkle Tree considered a ‘commitment’?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Indexing

A leaf at index i has a sibling at i ^ 1. Its parent is at i / 2.

Hint 2: Domain Separation

When hashing a leaf, use a byte like 0x00. When hashing two nodes together, use 0x01. This prevents an attacker from claiming an internal node is a leaf.

Hint 3: Space Optimization To compute the root without storing the whole tree, use the “TreeHash” algorithm: Keep a stack of hashes at different levels. Only merge two hashes if they are at the same level.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Merkle Trees | “Serious Cryptography” | Ch. 11 |

| Data Structures | “Algorithms, 4th Edition” | Ch. 3 |

Project 5: The SLH-DSA Address Scheme (Statelessness)

- File: LEARN_POST_QUANTUM_CRYPTO.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Knowledge Area: Deterministic State Management

- Main Book: NIST FIPS 205 Section 2.6

What you’ll build: A bit-level deterministic addressing system that generates unique 32-byte buffers for any position in a hyper-tree.

Why it teaches PQC: SPHINCS+ uses a “Hyper-tree” (a tree of trees). Each WOTS+ key and each Merkle node has a unique “Address.” If you get even one bit of the address wrong, the resulting hash will be completely different, and the signature will fail.

Real World Outcome

Deliverables:

- SLH-DSA address generator with fields

- Serialization/deserialization helpers

Validation checklist:

- Address fields are unique per operation

- Serialization is stable across platforms

- Endianness is explicitly handled

A function that, given (Seed, Layer=3, Tree=15, Leaf=2), always returns the same 32-byte private key component. You can generate any part of a billion-key signature on the fly without storing anything but the Master Seed.

Example Output:

$ ./slh_address --layer 0 --tree 1 --type WOTS_HASH --ots 5 --chain 3 --hash 1

Address Bytes: [ 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ... ]

$ ./slh_address --generate-key --seed "secret_seed" --layer 0 --tree 1 --ots 5

Key for Address: [ a1 b2 c3 d4 ... ] # Deterministically derived

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do we manage billions of one-time keys without a database?”

The answer is Deterministic Derivation. The address is a unique identifier that is XORed or hashed with the secret seed to produce a local secret.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Big-Endian Serialization

- NIST standards are very strict about how integers are converted to bytes.

- Hyper-tree Structure

- What is the difference between a “Tree Address” and an “OTS Address”?

- PRFs (Pseudo-Random Functions)

- How do we use SHAKE to turn a (Seed + Address) into a unique 32-byte key?

Questions to Guide Your Design

- The Address Struct

- How will you represent the 32-byte address in C? (Hint: A union or a struct with bitfields).

- Reuse

- How do you ensure that two different parts of the algorithm (e.g., WOTS vs. HORST) never use the same address?

Thinking Exercise

Imagine a tree with $2^{60}$ leaves. If each leaf is a 32-byte key, the total storage would exceed all hard drives on Earth. If you have a deterministic address scheme, how much storage do you actually need to sign a message?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “Why is it important to include the address in every hash operation in SLH-DSA?”

- “What happens if a user signs two different messages using the same address?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: The Struct

FIPS 205 defines the address as an array of 8 32-bit integers. Create a helper function set_layer_addr, set_tree_addr, etc.

Hint 2: Zeroing Always zero out the parts of the address you aren’t using. If you move from a WOTS operation to a Merkle operation, the “Chain Address” and “Hash Address” fields must be reset.

Hint 3: Key Derivation

Use PRF(Seed, Address) to get the secret for that specific location. In SLH-DSA, this is usually SHAKE.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| SLH-DSA Address Scheme | “NIST FIPS 205” | Section 2.6 |

| Pseudo-Random Functions | “Serious Cryptography” | Ch. 8 |

Project 6: FORS (Forest of Random Subsets) Signatures

- File: LEARN_POST_QUANTUM_CRYPTO.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Knowledge Area: Hash-based Crypto

- Main Book: NIST FIPS 205 Section 3.3

What you’ll build: An implementation of FORS (the successor to HORST), which is used in SLH-DSA to sign the message hash itself.

Why it teaches PQC: FORS is a “Few-Time Signature” (FTS). It allows you to sign a message by picking one leaf from each of $k$ different Merkle trees. It’s the “bridge” between the message and the hyper-tree.

Real World Outcome

Deliverables:

- FORS sign/verify implementation

- Auth path output for each tree

Validation checklist:

- Signature verifies against known vectors

- Altered signature fails verification

- Index calculations match spec parameters

A program that signs a 32-byte string and produces a FORS signature consisting of $k$ values and $k$ Merkle proofs.

Example Output:

$ ./fors_sign --msg "message_hash" --k 14 --t 2^8

FORS Signature Size: 14 * (32 + 8 * 32) bytes = 9.2 KB

$ ./fors_verify --sig signature.bin --root expected_root

Verification: SUCCESS

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How can we sign a message such that an attacker cannot forge a signature even if they see a few existing ones?”

FORS relies on the “subset” problem. Even if you know some secret leaves, the probability that a new message hash maps to the exact same set of leaves is astronomically low.

Thinking Exercise

If you have 10 trees of 1024 leaves each, and you reveal 1 leaf from each tree, what is the probability that a random message requires a leaf you haven’t revealed yet?

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| FORS / FTS | “NIST FIPS 205” | Section 3.3 |

| SPHINCS Analysis | “Post-Quantum Cryptography” (Bernstein) | Ch. 3 |

Project 7: ML-KEM (Kyber) Key Generation

- File: LEARN_POST_QUANTUM_CRYPTO.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Knowledge Area: Lattice-based Crypto

- Main Book: NIST FIPS 203 Section 11.1

What you’ll build: The key generation function for ML-KEM-768. This involves generating a public matrix $A$, a secret vector $s$, and an error vector $e$, and computing $t = As + e$.

Why it teaches PQC: This is the “Learning With Errors” (LWE) problem in action. You’ll learn how to “hide” a secret vector $s$ behind a matrix $A$ and a small amount of noise $e$. The complexity lies in sampling the noise from a Centered Binomial Distribution (CBD) and expanding the matrix $A$ from a seed.

Real World Outcome

Deliverables:

- ML-KEM key generator with seed input

- KAT comparison script

Validation checklist:

- Keypairs match NIST KAT outputs

- Public/secret key sizes are correct

- Deterministic mode reproduces keys

You’ll generate a public key (pk) and private key (sk) that are binary-compatible with the official NIST test vectors and libraries like liboqs.

Example Output:

$ ./kyber_keygen --out keys/

Generated Kyber-768 Keys:

Public Key (pk): 1184 bytes (Seed + Vector t)

Secret Key (sk): 2400 bytes

$ sha256sum keys/pk.bin

[Matching NIST Test Vector Hash]

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How can we create a ‘one-way’ function using only linear algebra and a little bit of noise?”

Without the noise e, anyone could solve for s using Gaussian elimination. The noise is the “trapdoor” that only the holder of s can bypass.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Module-LWE

- Why do we use vectors of polynomials instead of just raw numbers? (Efficiency and security).

- CBD (Centered Binomial Distribution)

- How do you sample noise such that it is “small” but random?

- XOF (Extendable Output Functions)

- Using SHAKE-128 to generate a $k \times k$ matrix of polynomials.

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Memory Management

- A Kyber-768 matrix $A$ is $3 \times 3$ polynomials of 256 coefficients each. How do you store this efficiently?

- NTT Domain

- Should you store your polynomials in the “Normal” domain or the “NTT” domain? (Hint: The spec performs multiplication in the NTT domain).

Project 8: ML-KEM Encapsulation & Decapsulation

- File: LEARN_POST_QUANTUM_CRYPTO.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Knowledge Area: Lattice-based Crypto

- Main Book: NIST FIPS 203 Section 11.2 & 11.3

What you’ll build: The full KEM logic where a sender “encapsulates” a shared secret for a receiver, and the receiver “decapsulates” it using their private key.

Why it teaches PQC: You’ll implement the actual “encryption” part of lattice crypto. You’ll see how the receiver uses their secret key to “subtract” the noise and recover the original bitstream. You’ll also learn about “compression” and “decompression” of polynomial coefficients to keep ciphertext small.

Real World Outcome

Deliverables:

- ML-KEM encaps/decap utilities

- Shared secret comparison tool

Validation checklist:

- Encap/decap shared secrets match

- Invalid ciphertext yields rejection behavior

- KATs pass for encaps/decap

A complete KEM suite. You can take a public key, produce a Ciphertext and a Shared Secret, and then use the private key to recover the same Shared Secret.

Example Output:

$ ./kyber_encaps --pk keys/pk.bin

Ciphertext: [1088 bytes]

Shared Secret (SS): [32 bytes - 8f3a...]

$ ./kyber_decaps --sk keys/sk.bin --ct ciphertext.bin

Recovered SS: [32 bytes - 8f3a...]

SUCCESS: Shared Secrets Match

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How can two parties agree on a secret key over an insecure channel that a quantum computer can’t crack?”

Thinking Exercise

If the noise $e$ in $As+e$ is too large, the decryption will fail. If it is too small, an attacker might solve the LWE problem. Kyber parameters are carefully chosen—can you calculate the probability of a “decryption failure”? (It’s roughly $2^{-128}$ for Kyber-768).

Interview Questions

- “What is the difference between a PKE (Public Key Encryption) and a KEM?”

- “Why does Kyber use ‘Re-encryption’ during decapsulation? (Fujisaki-Okamoto Transform).”

Project 9: ML-DSA (Dilithium) Key Generation

- File: LEARN_POST_QUANTUM_CRYPTO.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Knowledge Area: Lattice-based Signatures

- Main Book: NIST FIPS 204 Section 10.1

What you’ll build: Key generation for the ML-DSA signature scheme.

Why it teaches PQC: While Kyber is for encryption, Dilithium is for signatures. It uses a similar LWE-based approach but with a larger modulus $q$ and different polynomial sizes. You’ll learn about the “Fiat-Shamir with Aborts” framework.

Real World Outcome

Deliverables:

- ML-DSA keygen with deterministic seeds

- Key format exporter

Validation checklist:

- Keys match NIST KAT vectors

- Public key derived from secret key correctly

- Output sizes match spec

You’ll produce a Dilithium public/private key pair.

Example Output:

$ ./dili_keygen

Public Key: [1312 bytes]

Secret Key: [2528 bytes]

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Dilithium Specification | “NIST FIPS 204” | Section 10 |

| Fiat-Shamir Transform | “Serious Cryptography” | Ch. 12 |

Project 10: ML-DSA Signing & Verification

- File: LEARN_POST_QUANTUM_CRYPTO.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Knowledge Area: Lattice-based Signatures

- Main Book: NIST FIPS 204 Section 10.2 & 10.3

What you’ll build: The signing algorithm that produces a signature $(z, h)$ and the verification algorithm that checks its validity.

Why it teaches PQC: This is the most complex project. You’ll implement “Rejection Sampling”: if the signature might leak information about the secret key, you discard it and try again. This ensures that the signature is “Zero-Knowledge.”

Real World Outcome

Deliverables:

- ML-DSA sign/verify CLI

- Signature test suite

Validation checklist:

- Valid signatures verify

- Modified message fails verification

- Signature sizes match spec parameters

A signing utility that produces signatures that can be verified by anyone with the public key.

Example Output:

$ ./dili_sign --sk keys/sk.bin --msg "Protect the future"

Signature: [2420 bytes]

$ ./dili_verify --pk keys/pk.bin --msg "Protect the future" --sig sig.bin

Verification: VALID

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Rejection Sampling

- How do you implement the “while” loop such that it is constant-time? (Trick question: Signing Dilithium is not usually constant-time because of rejection, but the individual operations must be).

- Hint Bit Generation

- Dilithium uses “hints” ($h$) to help the verifier recover the high bits of the polynomial. How do you compute these?

Interview Questions

- “Why do we need rejection sampling in lattice signatures?”

- “What is a ‘side-channel’ attack, and how do we protect Dilithium from one?”

Project 11: PQC Interoperability Suite

- File: LEARN_POST_QUANTUM_CRYPTO.md

- Main Programming Language: Python

- Knowledge Area: Protocol Compliance / Data Serialization

What you’ll build: A Python test harness that takes your C implementations of Kyber and Dilithium and tests them against the official NIST test vectors (KAT - Known Answer Tests).

Why it teaches PQC: In the real world, crypto must be interoperable. If your library’s byte-ordering is different from the standard, it’s useless. You’ll learn how to parse the NIST .kat files and feed them into your C binaries.

Real World Outcome

Deliverables:

- Interop harness with multiple libraries

- Cross-implementation test report

Validation checklist:

- Sign/verify works across implementations

- KEM shared secrets match across libs

- Failure cases are consistent

A “Green/Red” dashboard showing that your library is 100% compliant with the international standards.

Example Output:

$ python3 test_interop.py --bin ./my_pqc_lib

Testing ML-KEM-768... [PASS] (100/100 vectors)

Testing ML-DSA-65... [PASS] (100/100 vectors)

Testing SLH-DSA-128f.. [PASS] (100/100 vectors)

Compliance Level: 100%

Project 12: PQC Performance Benchmarking

- File: LEARN_POST_QUANTUM_CRYPTO.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Knowledge Area: Performance Engineering

What you’ll build: A benchmarking tool that measures the CPU cycles and memory usage of each PQC primitive.

Why it teaches PQC: PQC is significantly heavier than ECC. You’ll see the massive difference in key sizes and signature sizes. You’ll use CPU performance counters (like rdtsc on x86) to measure exact costs.

Real World Outcome

Deliverables:

- Benchmark suite for keygen/encap/sign

- Report with latency and size metrics

Validation checklist:

- Results are repeatable within tolerance

- Measurements include CPU and memory

- Output format is machine-readable

A performance report comparing PQC to classical crypto.

Example Output:

$ ./benchmark

Algorithm | KeyGen (cyc) | Sign (cyc) | Key Size | Sig Size

--------------|--------------|------------|----------|---------

Ed25519 (ECC) | 50,000 | 60,000 | 32 B | 64 B

ML-DSA-65 | 1,200,000 | 3,500,000 | 1312 B | 2420 B

SLH-DSA-128f | 250,000,000 | 500,000,000 | 32 B | 17 KB

Project 13: Simulated PQC-TLS Handshake

- File: LEARN_POST_QUANTUM_CRYPTO.md

- Main Programming Language: Python

- Knowledge Area: Network Security / Cryptographic Protocols

What you’ll build: A simulated TLS 1.3 handshake that replaces ECDHE with ML-KEM and ECDSA with ML-DSA.

Why it teaches PQC: You’ll understand the “Post-Quantum Transition.” You’ll see how the larger keys impact network latency and packet fragmentation.

Real World Outcome

Deliverables:

- PQC-TLS handshake simulator

- Transcript log with derived secrets

Validation checklist:

- Client/server secrets match

- Transcript hash changes on tampering

- Hybrid mode combines classical + PQ secrets

A client/server simulation where you can see the handshake happening in real-time.

Example Output:

$ python3 pqc_tls_sim.py

[Client] Sending ClientHello (Kyber Public Key)...

[Server] Received ClientHello. Generating Kyber Ciphertext...

[Server] Sending ServerHello (Kyber CT + Dilithium Signature)...

[Client] Verifying Server Signature... [OK]

[Client] Decapsulating Shared Secret... [OK]

Handshake Complete.

Total Data Exchanged: 5.2 KB (Compared to 300 bytes for ECC)

Project Comparison Table

| Project | Difficulty | Time | Depth of Understanding | Fun Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Poly Engine | Level 2 | Weekend | High (Math) | Low |

| 2. SHA-3 | Level 3 | 1 Week | Medium | Medium |

| 3. WOTS+ | Level 3 | 1 Week | High (Hash-based) | Medium |

| 8. ML-KEM Full | Level 5 | 2 Weeks | Extreme (Lattice) | High |

| 10. ML-DSA Full | Level 5 | 3 Weeks | Extreme (Lattice) | High |

Summary

This learning path guides you from basic modular arithmetic to the frontier of quantum-resistant system design.

| # | Project Name | Main Language | Difficulty | Time Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Polynomial Engine | C | Level 2 | Weekend |

| 2 | SHA-3/SHAKE | C | Level 3 | 1 Week |

| 3 | WOTS+ Implementation | C | Level 3 | 1 Week |

| 4 | Merkle Authenticator | C | Level 2 | Weekend |

| 5 | SLH-DSA Address Scheme | C | Level 3 | Weekend |

| 6 | HORST Implementation | C | Level 4 | 1-2 Weeks |

| 7 | ML-KEM KeyGen | C | Level 4 | 1 Week |

| 8 | ML-KEM Encaps/Decaps | C | Level 5 | 2 Weeks |

| 9 | ML-DSA KeyGen | C | Level 4 | 1 Week |

| 10 | ML-DSA Sign/Verify | C | Level 5 | 3 Weeks |

| 11 | Interop Test Suite | Python | Level 3 | 1 Week |

| 12 | Performance Bench | C | Level 3 | 1 Week |

| 13 | Simulated PQC-TLS | Python | Level 4 | 2 Weeks |