NeoTrellis M4 Mastery - Real World Projects

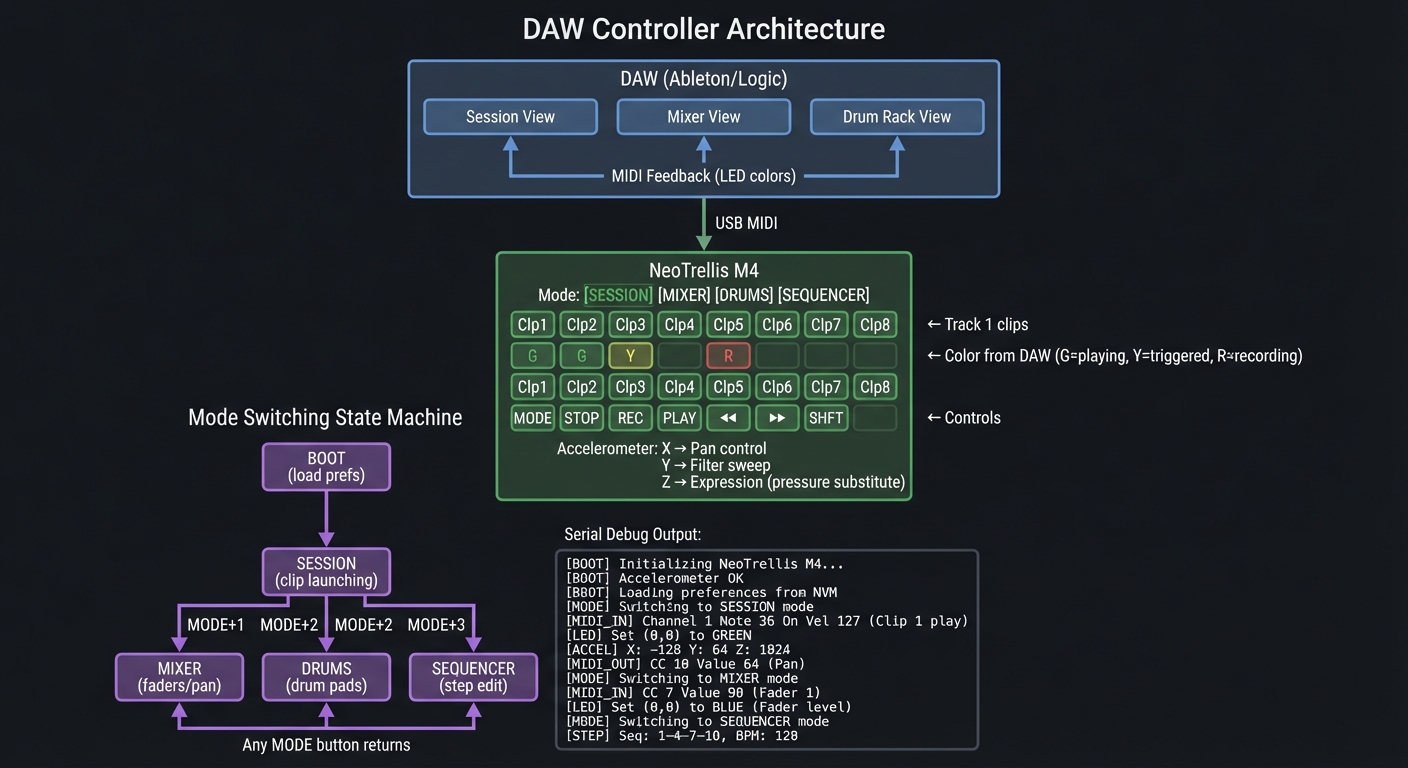

Goal: Completely master the Adafruit NeoTrellis M4—from basic button/LED interactions in CircuitPython, through Arduino audio synthesis, to bare-metal C programming that directly manipulates the ATSAMD51’s registers. You’ll understand the ARM Cortex-M4 architecture, I2C/SPI communication, DAC audio generation, accelerometer physics, USB protocols, and real-time embedded programming. By the end, you’ll be able to build professional MIDI controllers, synthesizers, interactive instruments, and understand exactly what happens at every level of the hardware stack.

Introduction

The Adafruit NeoTrellis M4 is a professional-grade embedded development board that combines a 4×8 button matrix, 32 RGB LEDs (NeoPixels), dual 12-bit DACs for stereo audio, a 3-axis accelerometer, and native USB MIDI—all powered by a 120 MHz ARM Cortex-M4F microcontroller with hardware floating-point and DSP capabilities.

What Is the NeoTrellis M4?

At its core, the NeoTrellis M4 is an audio-visual controller and embedded systems learning platform built around Microchip’s ATSAMD51J19 microcontroller. Unlike simple development boards, it integrates multiple real-world subsystems that professional music hardware uses:

- Input: 32-button tactile matrix with anti-ghosting diodes + 3-axis ADXL343 accelerometer

- Output: 32 addressable WS2812B RGB LEDs + dual 12-bit DAC stereo audio @ 500 KSPS

- Communication: Native USB (MIDI/Serial/Mass Storage) + I2C/SPI expansion headers

- Storage: 512 KB Flash + 192 KB SRAM + 8 MB external QSPI flash for samples/files

Sources:

What Problem Does It Solve?

The Learning Problem: Traditional embedded education separates concepts into isolated “blinky LED” examples that never connect to real-world applications. You learn GPIO, but never audio. You learn timers, but never build an instrument.

The NeoTrellis M4 Solves This By:

- Integrating all major embedded subsystems (GPIO, DAC/ADC, DMA, USB, I2C, timers) in one physical device

- Providing multiple abstraction levels (CircuitPython → Arduino → Bare-Metal C) so you can learn concepts before optimization

- Delivering immediate feedback—press a button, hear a sound, see an LED—no oscilloscope required for basic validation

- Matching commercial product architecture—skills transfer directly to MIDI controller, synthesizer, and IoT device development

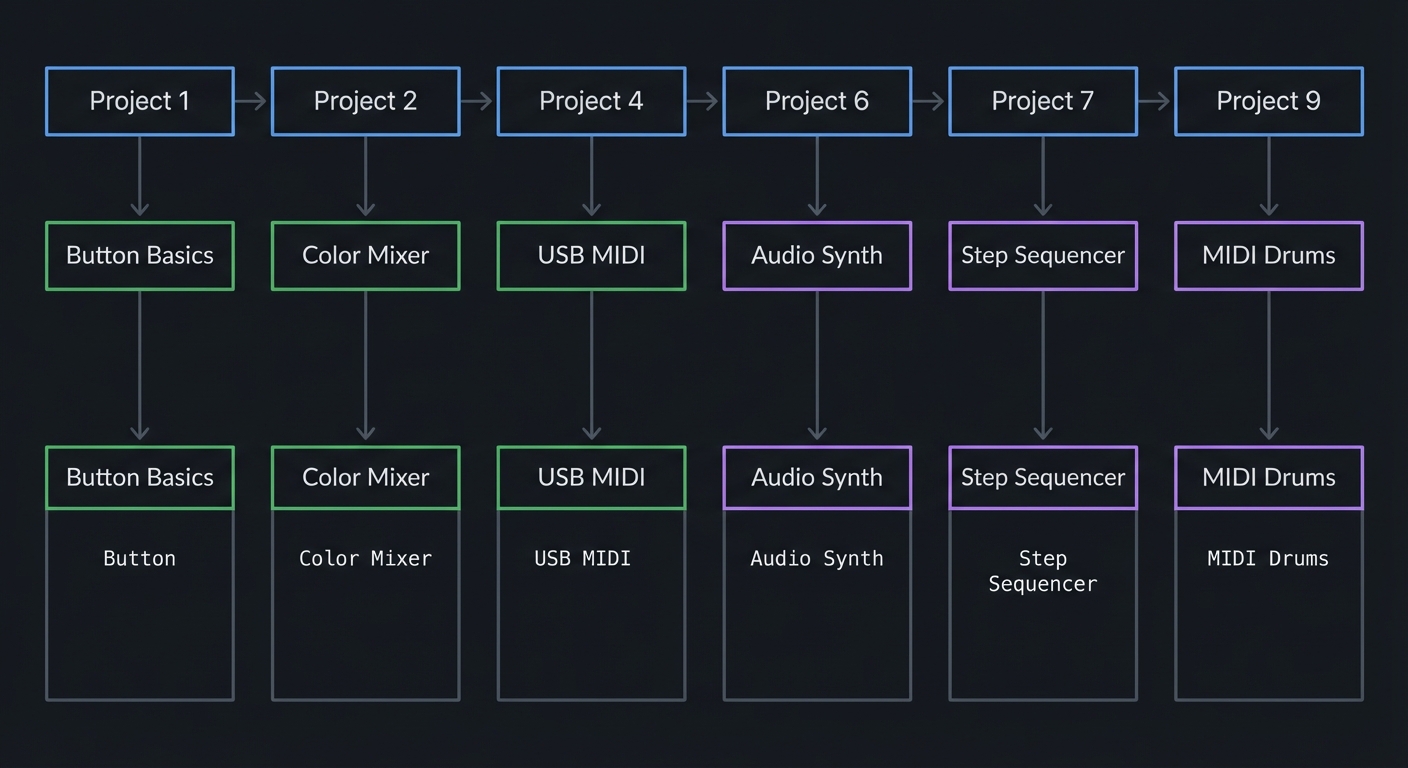

What You’ll Build Across These Projects

By completing this sprint, you’ll build:

- Interactive Instruments: MIDI controllers, polyphonic synthesizers, drum machines, step sequencers

- Audio-Visual Applications: FFT spectrum analyzers, audio visualizers, motion-reactive light shows

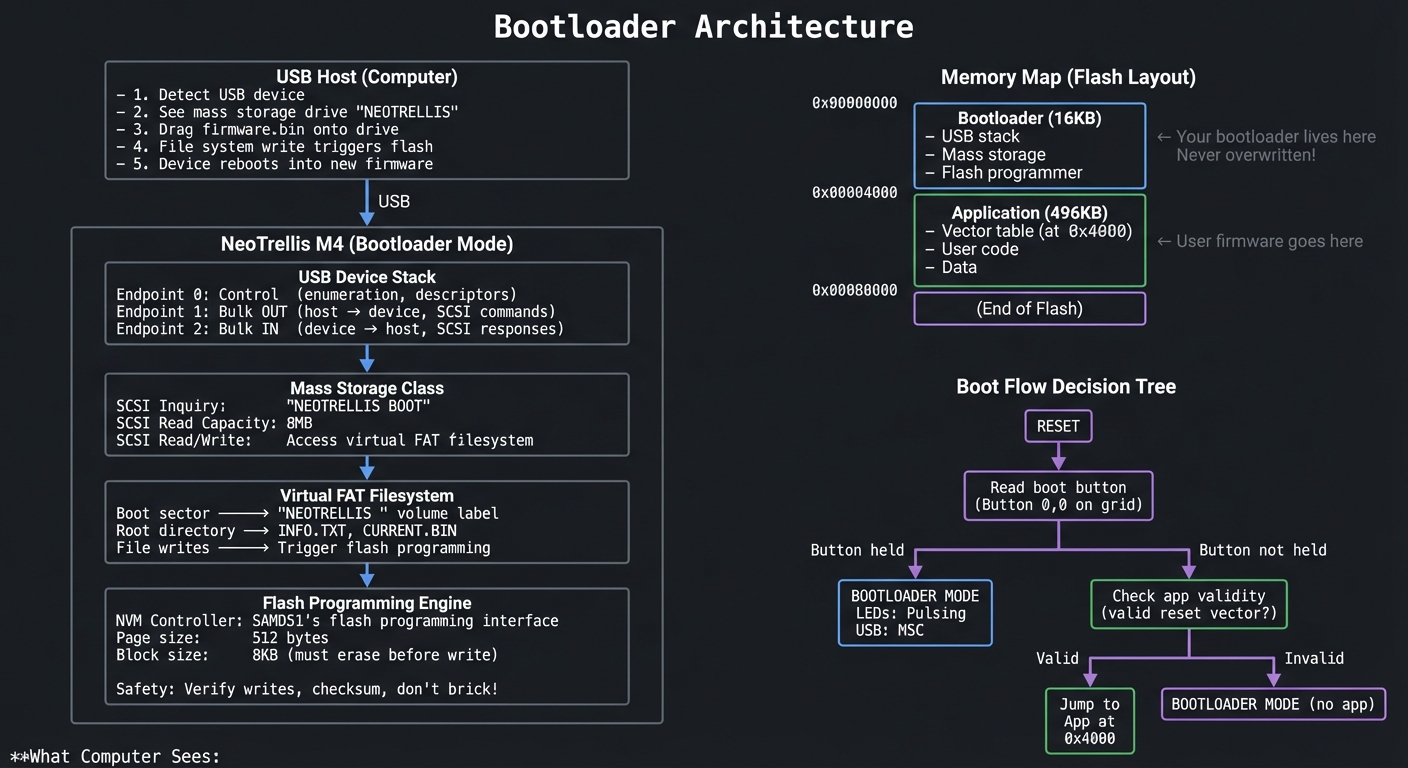

- Low-Level Drivers: Bare-metal NeoPixel driver, I2C accelerometer driver, USB bootloader

- Professional Tools: DAW controller with MIDI mapping, sample players, theremins

Each project produces a working, usable device that demonstrates specific embedded concepts through hands-on implementation.

Scope & Boundaries

What’s Included:

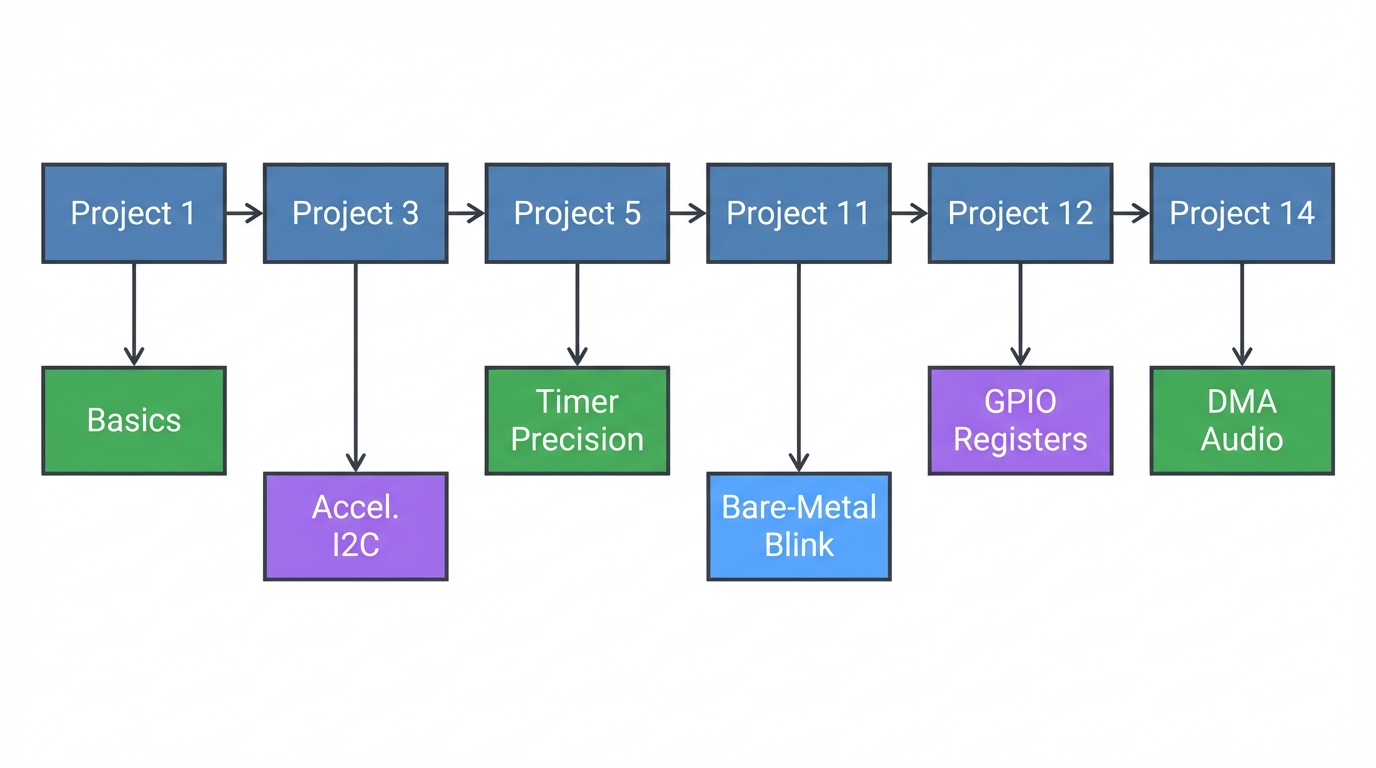

- ✅ CircuitPython rapid prototyping (Projects 1-5)

- ✅ Arduino audio synthesis with PJRC Audio library (Projects 6-10)

- ✅ Bare-metal C register programming (Projects 11-15)

- ✅ Full integration projects (Projects 16-18)

- ✅ ARM Cortex-M4 architecture, interrupts, DMA, peripherals

- ✅ Real-time audio DSP fundamentals

- ✅ USB MIDI protocol implementation

What’s Explicitly Out of Scope:

- ❌ Advanced DSP theory (FFT internals, filter design)

- ❌ PCB design or hardware modifications beyond optional extensions

- ❌ RTOS integration (FreeRTOS, Zephyr)

- ❌ Wireless communication (Bluetooth, WiFi)—focus is on core embedded concepts

- ❌ Production firmware (bootloader security, OTA updates, fail-safe recovery)

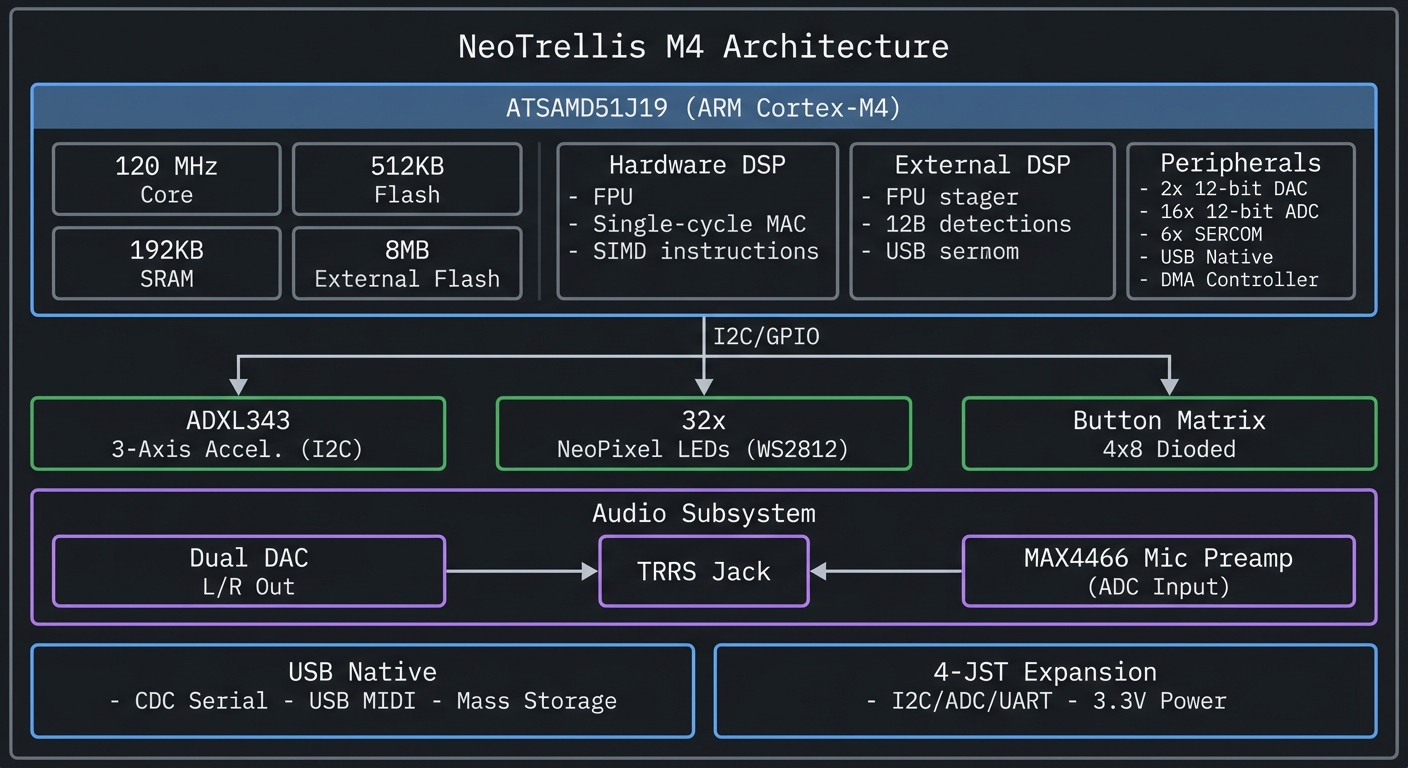

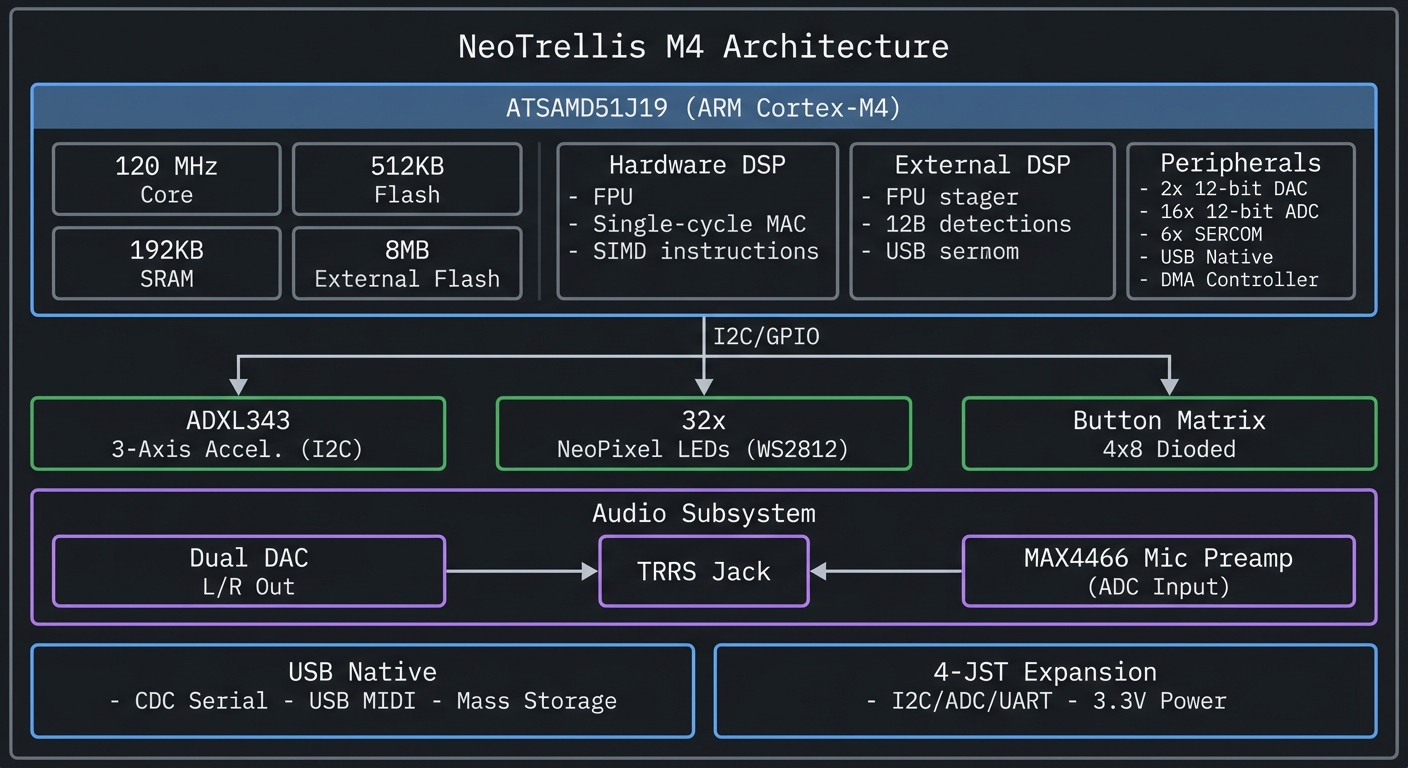

The System Architecture at a Glance

NeoTrellis M4 Architecture

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ ATSAMD51J19 (ARM Cortex-M4) │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ 120 MHz │ │ 512KB │ │ Hardware DSP │ │ │

│ │ │ Core │ │ Flash │ │ - FPU │ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ - Single-cycle MAC │ │ │

│ │ └─────────────┘ └─────────────┘ │ - SIMD instructions │ │ │

│ │ └─────────────────────────┘ │ │

│ │ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ 192KB │ │ 8MB │ │ Peripherals │ │ │

│ │ │ SRAM │ │ External │ │ - 2x 12-bit DAC │ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ Flash │ │ - 16x 12-bit ADC │ │ │

│ │ └─────────────┘ └─────────────┘ │ - 6x SERCOM │ │ │

│ │ │ - USB Native │ │ │

│ │ │ - DMA Controller │ │ │

│ └────────────────────────────────────┴─────────────────────────┴──┘ │

│ │ │

│ │ I2C/GPIO │

│ ┌──────────────────┼──────────────────┐ │

│ │ │ │ │

│ ▼ ▼ ▼ │

│ ┌───────────┐ ┌───────────┐ ┌───────────┐ │

│ │ ADXL343 │ │ 32x │ │ Button │ │

│ │ 3-Axis │ │ NeoPixel │ │ Matrix │ │

│ │ Accel. │ │ LEDs │ │ 4x8 │ │

│ │ (I2C) │ │ (WS2812) │ │ Dioded │ │

│ └───────────┘ └───────────┘ └───────────┘ │

│ │

│ ┌───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Audio Subsystem │ │

│ │ ┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐ ┌──────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ Dual DAC │───▶│ TRRS │◀───│ MAX4466 Mic Preamp │ │ │

│ │ │ L/R Out │ │ Jack │ │ (ADC Input) │ │ │

│ │ └──────────┘ └──────────┘ └──────────────────────┘ │ │

│ └───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ ┌─────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ USB Native │ │ 4-JST Expansion │ │

│ │ - CDC Serial │ │ - I2C/ADC/UART │ │

│ │ - USB MIDI │ │ - 3.3V Power │ │

│ │ - Mass Storage│ └─────────────────────────┘ │

│ └─────────────────┘ │

│ │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Key Insight: Every layer of abstraction (Python → C++ → Bare C) controls the same hardware. Understanding all three levels gives you the ability to prototype rapidly, optimize selectively, and debug fearlessly.

How to Use This Guide

This guide is structured as a theory-first, project-based sprint. Theory builds mental models; projects apply them.

Reading Strategy

For Beginners (New to Embedded Systems):

- Read the entire Theory Primer (next section) before starting any project

- Complete Projects 1-5 in order using CircuitPython

- Return to the primer when concepts feel unclear

- Move to Arduino projects (6-10) only after solid understanding of CircuitPython

For Intermediate (Have Arduino Experience):

- Skim Theory Primer, focus on ARM architecture and audio sections

- Start with Project 1 to understand the board, then jump to Project 6 (Arduino synthesis)

- Read bare-metal sections when ready for Projects 11-15

For Advanced (Want Bare-Metal Expertise):

- Read Theory Primer sections on ARM Cortex-M4, Memory Mapping, DMA

- Complete Projects 1-2 quickly for board familiarization

- Focus on Projects 11-18 (bare-metal and integration)

Working Through Projects

Each project follows this structure:

- Real World Outcome: What you’ll see/hear when done (with exact CLI output or behavior)

- Core Question: The fundamental concept this project answers

- Prerequisites: Concepts you must understand first (with book references)

- Design Questions: Guide your implementation thinking

- Thinking Exercise: Mental model building before coding

- Layered Hints: Progressive help when stuck (no complete code)

- Common Pitfalls: Debug guide for likely issues

- Definition of Done: Explicit completion criteria

Never skip the “Thinking Exercise”—it builds intuition that code alone cannot.

Book Integration

This guide references specific chapters from books you likely own (see BOOKS.md). The pattern:

- Theory Primer → Read relevant book chapters for deep understanding

- Project Prerequisites → Consult books for specific techniques

- Debugging → Use books for troubleshooting strategies

You don’t need to read entire books—targeted chapter reading is sufficient.

Lab Setup Recommendations

Minimum Viable Setup:

- NeoTrellis M4 with buttons and enclosure

- USB-C cable

- Headphones or powered speakers (3.5mm)

- Computer (Windows/macOS/Linux)

Recommended Additions:

- Logic analyzer or oscilloscope (Projects 11-15)

- USB MIDI-capable DAW (GarageBand, Ableton Live Lite, REAPER)

- Multimeter (voltage/continuity checking)

Optional (Advanced Projects):

- J-Link or Atmel-ICE debugger

- External I2C/SPI devices for expansion projects

Time Management

Budget your time realistically:

| Project Type | Time per Project | Skill Focus |

|---|---|---|

| CircuitPython (1-5) | 4-8 hours | Concepts, rapid iteration |

| Arduino Audio (6-10) | 8-16 hours | DSP, libraries, performance |

| Bare-Metal C (11-15) | 12-24 hours | Registers, timing, drivers |

| Integration (16-18) | 20-40 hours | System design, debugging |

Total sprint: 3-4 months if working 4-6 hours/week.

When You Get Stuck

- Check Definition of Done: Are you solving the right problem?

- Review Thinking Exercise: Did you understand before coding?

- Read Common Pitfalls: Your issue is likely listed

- Consult Book References: Theory gaps often cause implementation struggles

- Add Serial Debugging: Print timestamps, values, state transitions

- Use Hints Progressively: Read Hint 1, try again; if stuck, read Hint 2…

Do NOT skip to Hint 4 immediately—the learning happens in the struggle.

Prerequisites & Background Knowledge

Essential Prerequisites (Must Have)

Before starting these projects, you should:

Programming Foundations:

- Basic Python syntax (variables, loops, functions, classes)

- Understanding of bits and bytes (binary, hexadecimal)

- Familiarity with arrays/lists and basic data structures

- Boolean logic and bit manipulation (AND, OR, XOR, shifts)

Hardware Basics:

- Know what GPIO (General Purpose Input/Output) means

- Understand voltage levels (3.3V logic, HIGH/LOW states)

- Can follow a simple wiring diagram

- Recognize basic electronic components (resistor, capacitor, LED)

Development Environment:

- Comfortable with command line/terminal basics

- Can install software packages and libraries

- Have a text editor you’re comfortable with (Mu, VS Code, or similar)

- Understand file paths and directory navigation

Mathematics (for Audio Projects):

- Basic trigonometry (sine, cosine)

- Understand frequency, period, amplitude

- Can read logarithmic scales (decibels)

Recommended Reading: “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” by Bryant & O’Hallaron - Ch. 1-2

Helpful But Not Required

You’ll learn these during the projects:

- Prior microcontroller experience (Arduino Uno, Raspberry Pi Pico) → Projects 1-5 teach this

- C programming experience → Introduced progressively in Projects 6-10, required for 11-18

- Knowledge of audio/music concepts (notes, MIDI, synthesis) → Explained in audio project primers

- Understanding of USB protocols → Covered in Theory Primer

- Assembly language → Not required; register-level C is sufficient

Self-Assessment Questions

Before starting, can you answer these?

- Python: What’s the difference between a list and a dictionary? When would you use each?

- Binary: What’s

0xFFin decimal? What’s0b10101010in hexadecimal? - Hardware: If a pin outputs 3.3V, is it HIGH or LOW? What about 0V?

- Timing: How many milliseconds in one second? How many microseconds in one millisecond?

- Logic: What’s

0b1100 & 0b1010in binary? What about0b1100 | 0b1010? - C basics (for Arduino projects): What’s the difference between

int x = 5;andint *x = &y;?

If you struggled with questions 1-5, spend a day reviewing Python and digital logic fundamentals first. If you struggled with question 6, complete CircuitPython projects first, then learn C alongside Arduino projects.

Required Hardware

For all projects in this guide, you need:

- Adafruit NeoTrellis M4 with Enclosure and Buttons Kit Pack (Product 4020)

- Includes mainboard, enclosure, 32 silicone button pads

- Cost: ~$60 USD (2024)

- USB-C cable (for programming and power)

- Headphones or powered speakers (3.5mm TRRS jack for audio projects)

- Computer with USB port (Windows, macOS, or Linux)

Total investment: ~$60-80 (assuming you have a computer and headphones)

Optional But Highly Recommended

These dramatically improve the learning experience:

Software:

- USB-MIDI capable software: Ableton Live Lite (often free with hardware), GarageBand (macOS), REAPER (trial), or VCV Rack (free)

- Serial terminal: Arduino IDE Serial Monitor, Mu Editor REPL, or

screen/minicom

Hardware (for bare-metal projects):

- Logic analyzer or oscilloscope: Verify timing on WS2812B, I2C, UART (~$10-50 for Saleae clones)

- Multimeter: Verify connections, measure voltages (~$15-30)

- J-Link EDU Mini or Atmel-ICE: Hardware debugging for bare-metal C (~$20-60)

Development Environment Setup

For CircuitPython (Projects 1-5):

- Download CircuitPython firmware for Trellis M4:

- Visit circuitpython.org

- Download latest stable release (9.x as of 2024)

- Install firmware:

- Double-tap RESET button on NeoTrellis M4

- Board mounts as

TRELLIS_BOOTdrive - Drag

.UF2file onto drive - Board reboots as

CIRCUITPYdrive

- Install editor:

- Mu Editor (beginner-friendly): codewith.mu

- VS Code with CircuitPython extension (advanced)

- Install libraries:

- Download Adafruit CircuitPython Library Bundle

- Copy required folders to

CIRCUITPY/lib/:adafruit_neotrellis,adafruit_seesaw,adafruit_adxl34x

Verification:

# In Mu Editor REPL:

import board

dir(board) # Should show NEOPIXEL, SDA, SCL, etc.

For Arduino (Projects 6-10):

-

Install Arduino IDE 2.x: arduino.cc

- Add SAMD board support:

- File → Preferences → Additional Board Manager URLs:

https://adafruit.github.io/arduino-board-index/package_adafruit_index.json - Tools → Board Manager → Search “Adafruit SAMD” → Install

- File → Preferences → Additional Board Manager URLs:

- Select board:

- Tools → Board → Adafruit SAMD Boards → Adafruit NeoTrellis M4

- Install libraries (Tools → Manage Libraries):

Adafruit_NeoTrellisAdafruit_NeoPixelAdafruit_ADXL343Adafruit_SAMD_Audio(for Projects 6-10)pjrc_Audio(Adafruit fork for SAMD51)

Verification:

// Upload this sketch:

void setup() {

Serial.begin(115200);

while(!Serial);

Serial.println("NeoTrellis M4 Ready!");

}

void loop() {}

For Bare-Metal C (Projects 11-15):

- Install ARM GCC toolchain:

- macOS:

brew install arm-none-eabi-gcc - Linux:

sudo apt install gcc-arm-none-eabi - Windows: ARM GNU Toolchain

- macOS:

- Install flasher (choose one):

- BOSSA (drag-and-drop): github.com/shumatech/BOSSA

- OpenOCD (advanced):

brew install openocd/apt install openocd

- Download SAMD51 resources:

- Datasheet: Microchip ATSAMD51 Family Datasheet

- CMSIS headers: SAMD51 Device Family Pack

- Optional: Install SEGGER J-Link software for hardware debugging

Verification:

arm-none-eabi-gcc --version # Should show version 10.x or newer

bossac --help # Should show BOSSA flasher options

Power & Safety Rules

Critical Safety Practices:

- Unplug before wiring: Disconnect USB when adding external components or modifying circuits

- Avoid shorts: The board has a 500mA resettable fuse, but repeated trips slow debugging

- NeoPixel wire length: Keep data wire short (<6 inches) to reduce timing errors and reflections

- USB power limits: If connecting power-hungry peripherals, use a powered USB hub

- Static protection: Touch grounded metal before handling board to discharge static

Common Mistakes That Damage Hardware:

- ❌ Connecting 5V signals to 3.3V pins (use level shifter)

- ❌ Shorting power rails during breadboard wiring

- ❌ Hot-plugging I2C devices while powered (can corrupt bus)

- ❌ Exceeding 3.3V on any GPIO (instant damage)

Time Investment Reality Check

Be realistic about learning timelines:

| Learning Path | Time Commitment | Prerequisites |

|---|---|---|

| CircuitPython only (Projects 1-5) | 2-3 weeks @ 6hrs/week | Python basics |

| Arduino + Audio (Projects 6-10) | 4-6 weeks @ 6hrs/week | C++ basics |

| Bare-Metal C (Projects 11-15) | 8-12 weeks @ 6hrs/week | Strong C, some assembly |

| Complete Mastery (All 18 projects) | 3-4 months @ 6hrs/week | All of the above + patience |

Important Reality Check:

- Don’t rush. Embedded debugging takes longer than application programming.

- Expect failures. LEDs will blink wrong, audio will glitch, I2C will NACK. This is normal.

- Read datasheets. The ATSAMD51 datasheet has 1700+ pages. You’ll reference it constantly for bare-metal work.

- Build incrementally. Every project has intermediate milestones. Celebrate small wins.

If you can only dedicate 2-3 hours/week, budget 6-8 months for complete mastery.

Big Picture / Mental Model

Before diving into theory, understand the conceptual layers of embedded audio-visual systems.

The Three-Layer Embedded Stack

Every embedded system has three conceptual layers. Understanding their relationship is key to debugging and optimization.

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ APPLICATION LAYER │

│ "What" - The logic, algorithms, and behavior │

│ Example: "Play a C major chord when buttons 0,4,7 are pressed" │

│ │

│ Tools: CircuitPython, Arduino libraries, high-level C code │

│ Characteristics: Readable, portable, slower │

└────────────────┬─────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│ API calls (digitalWrite, analogWrite, etc.)

▼

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ ABSTRACTION LAYER │

│ "How" - Libraries, drivers, hardware abstraction layer (HAL) │

│ Example: NeoPixel.show() → DMA setup → bit-banging timing │

│ │

│ Tools: Arduino libraries, CircuitPython modules, vendor SDKs │

│ Characteristics: Hides complexity, handles edge cases │

└────────────────┬─────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│ Register writes, interrupt handlers

▼

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ HARDWARE LAYER │

│ "Where" - Registers, peripherals, electrical signals │

│ Example: PORT->Group[0].OUTSET.reg = (1 << 10); // Set PA10 │

│ │

│ Tools: Bare C, assembly, memory-mapped I/O, oscilloscope │

│ Characteristics: Maximum control, timing precision, complexity │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Why This Matters:

- CircuitPython operates at Application + Abstraction layers → fast prototyping

- Arduino spans Abstraction + Hardware layers → balance of ease and control

- Bare-Metal C lives at Hardware layer → you write the abstraction

The Learning Path: Start at the top (CircuitPython), understand behavior, then descend to learn how it’s implemented.

The Four Major Subsystems

The NeoTrellis M4 integrates four independent-but-connected subsystems:

NeoTrellis M4 Subsystems

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ │

│ ┌──────────────────┐ ┌──────────────────┐ │

│ │ INPUT │ │ PROCESSING │ │

│ │ ────── │ ┌───▶│ ────────── │ │

│ │ • 32 Buttons │────┤ │ • ARM M4 Core │ │

│ │ • Accelerometer │ │ │ • 120MHz FPU │ │

│ │ • Mic Input │────┘ │ • 192KB SRAM │ │

│ └──────────────────┘ └────────┬─────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌──────────────────┐ ┌──────────────────┐ │

│ │ VISUAL OUTPUT │ ┌────│ AUDIO OUTPUT │ │

│ │ ───────────── │◀───┤ │ ──────────── │ │

│ │ • 32 NeoPixels │ │ │ • Dual 12-bit │ │

│ │ • WS2812 800kHz │ │ │ DAC │ │

│ │ • DMA driven │ │ │ • Stereo 44.1k │ │

│ └──────────────────┘ │ │ • DMA driven │ │

│ │ └──────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ │ ┌──────────────────┐ │

│ └───▶│ COMMUNICATION │ │

│ │ ───────────── │ │

│ │ • USB MIDI │ │

│ │ • I2C/SPI │ │

│ │ • UART │ │

│ └──────────────────┘ │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Subsystem Interactions:

- Input → Processing: Button press generates interrupt → CPU reads matrix → Updates application state

- Processing → Visual: Application computes LED colors → DMA transfers to NeoPixel chain

- Processing → Audio: Synthesis algorithm fills buffer → DMA streams to DAC → Analog waveform output

- Processing → Communication: MIDI note generated → USB endpoint buffer → Host receives event

The Mental Model: Think of these as parallel pipelines, each with different timing constraints:

- Buttons: Must scan < 10ms for responsive feel

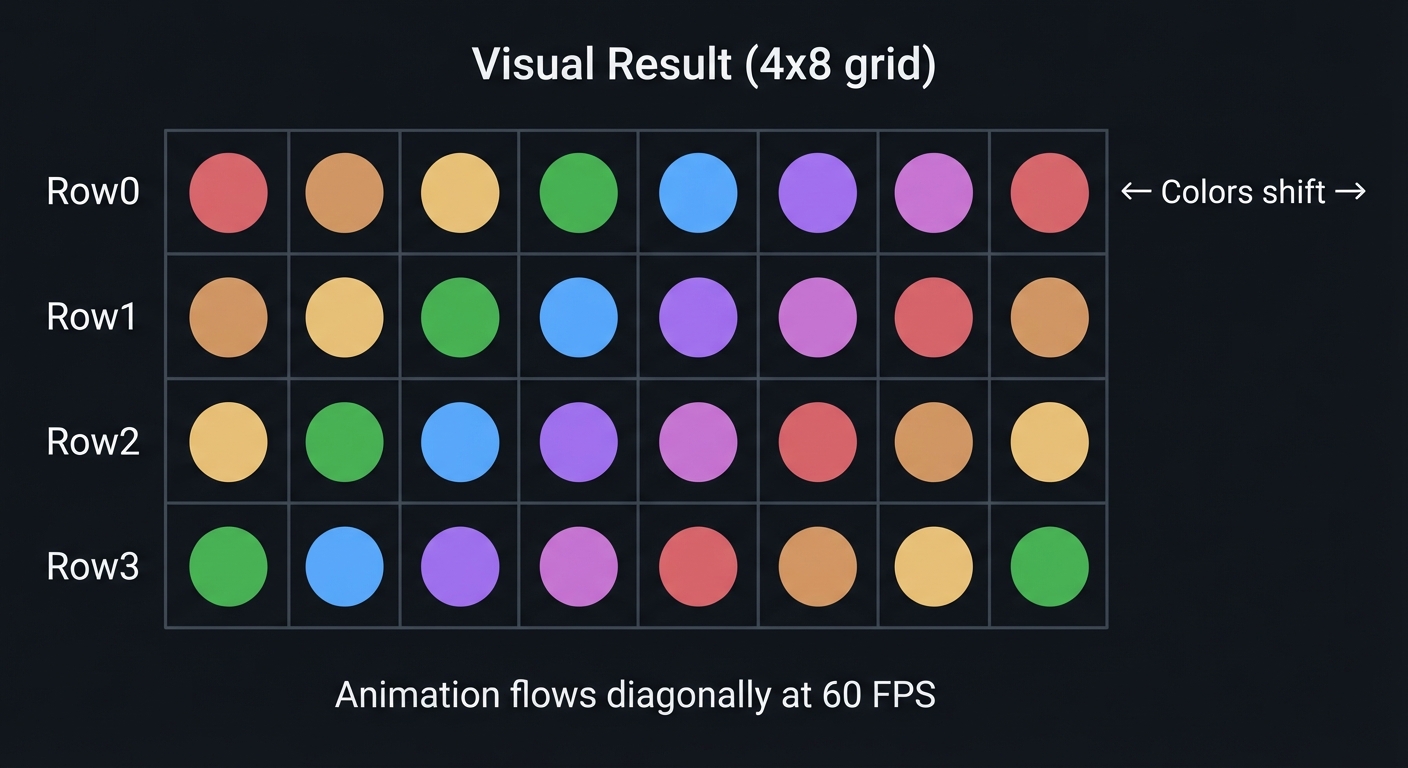

- LEDs: Must update at 60 FPS (16.6ms) for smooth animation

- Audio: Must generate samples every 22.6μs (44.1kHz) without glitches

- USB: Must respond to host polls within 1ms (USB Full-Speed)

Timing Is Everything: The Real-Time Budget

The CPU’s 120 MHz clock seems fast, but real-time constraints are unforgiving:

Timing Budget Breakdown

1 Second = 1,000,000 μs

├─── 44,100 audio samples

│ └─── Each sample: 22.68 μs

│ └─── 2,721 clock cycles @ 120MHz

│ (must compute L+R channels, envelopes, filters)

│

├─── 60 LED frames

│ └─── Each frame: 16,667 μs

│ └─── 32 LEDs × 30μs = 960μs DMA transfer

│ (CPU free during DMA, can compute next frame)

│

├─── 100 button scans

│ └─── Each scan: 10,000 μs

│ └─── Scan 32 buttons in ~100μs

│ (leaves 9,900μs for other work)

│

└─── 1,000 USB polls (Full-Speed = 1ms)

└─── Each poll: 1,000 μs

└─── Must respond within 500μs or host times out

What This Means In Practice:

- A blocking delay of 1ms can drop an audio sample (audible glitch)

- Interrupt latency >10μs can corrupt NeoPixel data

- CPU-bound audio synthesis limits polyphony (e.g., 8 voices max without optimization)

The Solution: Use DMA (Direct Memory Access) to transfer audio/LED data while CPU computes next frame. This is why bare-metal projects focus on DMA setup.

Data Flow: From Physical Input to Physical Output

Trace a button press → sound output to see all subsystems interact:

Physical Event: User presses button (2, 3)

│

▼

1. Hardware: Matrix scan detects closure at row 2, col 3

│ (GPIO interrupt fires)

▼

2. Interrupt Handler: Reads PORT registers, debounces

│ (stores event in queue)

▼

3. Application: Main loop processes event queue

│ (calculates: button index = 2*8+3 = 19)

│ (MIDI note = 60 + 19 = 79 = G5)

▼

4. Synthesis: Allocates voice, starts envelope

│ (computes: phase_inc = (freq * 2^32) / sample_rate)

▼

5. Audio Callback: Generates samples at 44.1kHz

│ (for each sample: output += voice[i].amplitude * sin(phase))

▼

6. DMA: Transfers buffer to DAC peripheral

│ (hardware converts digital → analog)

▼

7. Analog: DAC outputs voltage to TRRS jack

│ (0-3.3V signal drives headphones/speakers)

▼

Physical Output: User hears G5 note from speakers

│

│ Simultaneously:

├─── LED 19 lights up (visual feedback via NeoPixel)

└─── USB MIDI sends Note On (79, velocity 100) to DAW

Total Latency: ~5-15ms from button press to sound (imperceptible to humans)

Why Each Step Matters:

- Step 2 (Debouncing): Prevents one press from registering as multiple events

- Step 4 (Voice allocation): Enables polyphony (multiple notes simultaneously)

- Step 6 (DMA): Frees CPU to compute next buffer while hardware outputs current buffer

- Step 7 (Analog output): Quality of DAC determines audio fidelity (12-bit = 72dB dynamic range)

Theory Primer: Deep Dive into Core Concepts

This section builds the foundational knowledge you need before starting projects. Each concept has:

- Fundamentals: What it is and why it exists

- Deep Dive: How it works in detail

- Mental Model: Diagram to visualize the concept

- Minimal Example: Concrete code or protocol transcript

- Common Misconceptions: What beginners get wrong

- Where You’ll Apply It: Which projects use this concept

Read this section before starting projects if you’re new to embedded systems. Refer back when concepts feel unclear.

Chapter 1: ARM Cortex-M4 Architecture

Fundamentals

The ARM Cortex-M4 is a 32-bit RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computer) processor core designed specifically for real-time embedded applications. Unlike general-purpose CPUs (Intel x86, AMD64), the Cortex-M4 prioritizes deterministic interrupt latency, low power consumption, and efficient DSP operations.

The ATSAMD51J19 microcontroller on the NeoTrellis M4 implements the Cortex-M4 core with these key features:

- 120 MHz clock speed (5x faster than Arduino Uno’s ATmega328P @ 16MHz)

- Hardware Floating-Point Unit (FPU) for single-precision math (10x faster than software emulation)

- DSP extensions with single-cycle MAC (Multiply-Accumulate) for signal processing

- NVIC (Nested Vectored Interrupt Controller) for low-latency interrupts (<15 clock cycles)

- Memory Protection Unit (MPU) for safety-critical applications (optional, not used in projects)

Why ARM Cortex-M4 Dominates Embedded Audio: According to ARM’s documentation, the Cortex-M4 targets “digital signal control markets demanding an efficient, easy-to-use blend of control and signal processing capabilities.” It’s used in:

- Music hardware: Teenage Engineering OP-1, Elektron Digitakt, Moog One

- Industrial automation: Motor control, power management

- Consumer electronics: Audio codecs, active noise cancellation

Sources:

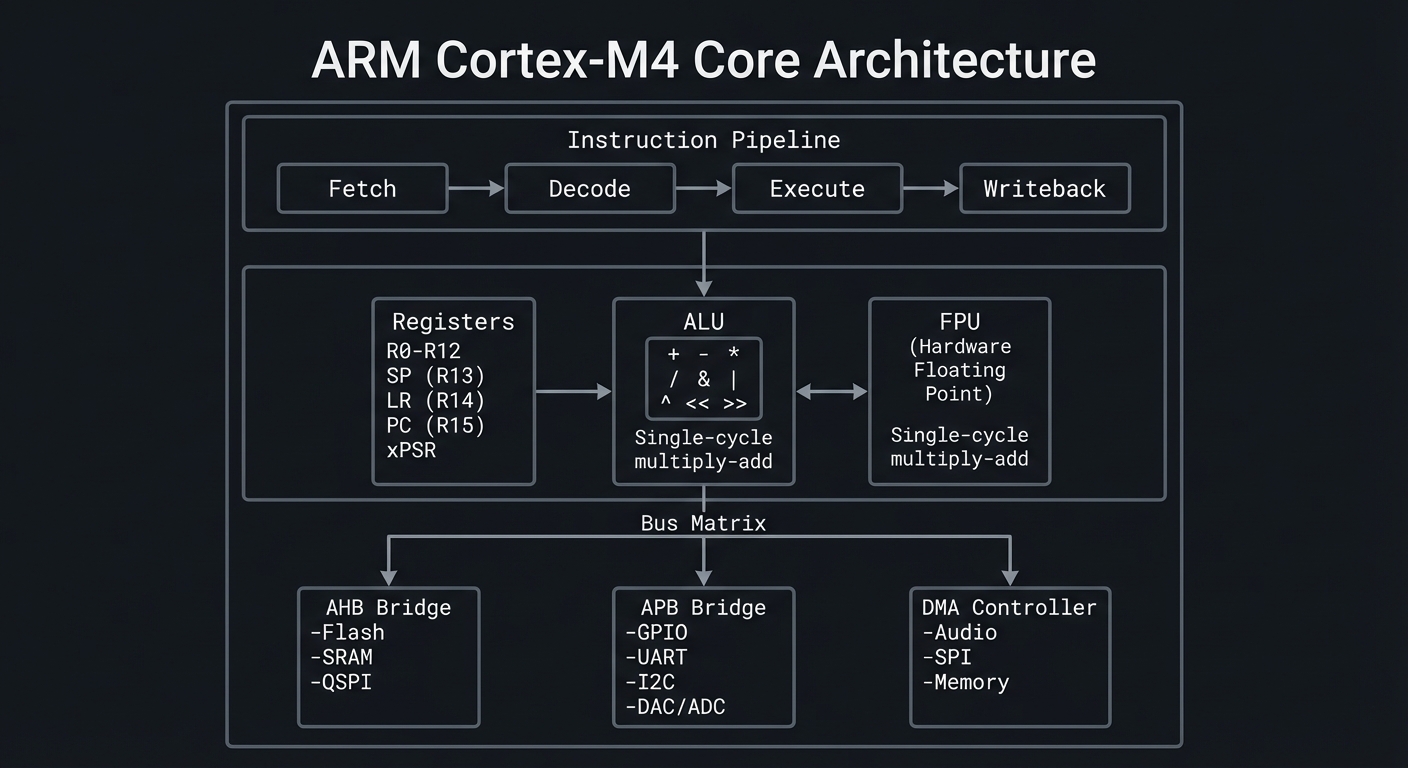

Deep Dive: How the Cortex-M4 Executes Code

The Cortex-M4 uses a 3-stage pipeline (Fetch-Decode-Execute) to process instructions:

Instruction Pipeline:

- Fetch: Load next instruction from Flash memory into instruction register

- Decode: Interpret instruction opcode and operands

- Execute: Perform operation (ALU math, memory access, branch)

While one instruction executes, the next is being decoded, and a third is being fetched. This instruction-level parallelism means throughput approaches 1 instruction per clock cycle (120 MIPS @ 120MHz).

Register Set:

- R0-R12: General-purpose registers (32-bit each) for data manipulation

- R13 (SP): Stack Pointer—points to top of current stack frame

- R14 (LR): Link Register—stores return address when calling functions

- R15 (PC): Program Counter—points to next instruction to execute

- xPSR: Program Status Register—holds flags (Negative, Zero, Carry, Overflow)

Example: Adding Two Numbers:

C code: int sum = a + b;

ARM Assembly: LDR R0, [R1] ; Load 'a' from memory into R0

LDR R2, [R3] ; Load 'b' from memory into R2

ADD R0, R0, R2 ; R0 = R0 + R2 (sum)

STR R0, [R4] ; Store R0 back to memory (sum)

Clock cycles: 4 cycles (assuming cache hit)

Floating-Point Unit (FPU): The FPU accelerates single-precision (32-bit) floating-point operations:

Without FPU (software emulation):

float x = 1.5f * 2.3f; // ~50 clock cycles

With FPU (hardware):

float x = 1.5f * 2.3f; // 1-3 clock cycles

Speedup: 10-50x for math-heavy code

Why This Matters for Audio: Synthesis algorithms use heavy floating-point math:

// Sine wave oscillator (typical per-sample computation)

for (int i = 0; i < buffer_size; i++) {

phase += phase_increment; // FPU: 1 cycle

output[i] = amplitude * sinf(phase); // FPU: ~10 cycles (sin lookup + multiply)

}

With 8 voices polyphony @ 44.1kHz, that’s 8 voices × 44,100 samples/sec × 11 cycles ≈ 3.9M cycles/sec, leaving 116M cycles for envelopes, filters, and LED updates.

Mental Model Diagram

ARM Cortex-M4 Core Architecture

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Instruction Pipeline │ │

│ │ ┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ Fetch │──▶│ Decode │──▶│ Execute │──▶│Writeback│ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ └──────────┘ └──────────┘ └──────────┘ └──────────┘ │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ┌──────────────────────────┼──────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ │ │ │

│ │ ┌────────────────┐ ┌───┴───────────┐ ┌────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ Registers │ │ ALU │ │ FPU │ │ │

│ │ │ R0-R12 │ │ │ │ (Hardware │ │ │

│ │ │ SP (R13) │ │ ┌─────────┐ │ │ Floating │ │ │

│ │ │ LR (R14) │ │ │ + - * │ │ │ Point) │ │ │

│ │ │ PC (R15) │ │ │ / & | │ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ │ xPSR │ │ │ ^ << >> │ │ │ Single-cycle │ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ └─────────┘ │ │ multiply-add │ │ │

│ │ └────────────────┘ └───────────────┘ └────────────────┘ │ │

│ │ │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ │ Bus Matrix │

│ │ │

│ ┌──────────────────────────┼──────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ │ │ │

│ ▼ ▼ ▼ │

│ ┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐│

│ │ AHB │ │ APB │ │ DMA ││

│ │ Bridge │ │ Bridge │ │Controller││

│ │ │ │ │ │ ││

│ │ -Flash │ │ -GPIO │ │ -Audio ││

│ │ -SRAM │ │ -UART │ │ -SPI ││

│ │ -QSPI │ │ -I2C │ │ -Memory ││

│ │ │ │ -DAC/ADC │ │ ││

│ └──────────┘ └──────────┘ └──────────┘│

│ │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Key Architectural Insights:

- Bus Matrix: Allows simultaneous memory access (CPU reads Flash while DMA writes SRAM)

- AHB Bus: High-speed bus for Flash/SRAM (120 MHz, 32-bit wide)

- APB Bus: Lower-speed bus for peripherals (60 MHz typically)

- DMA Controller: Can transfer data without CPU intervention (critical for audio/LEDs)

How This Fits on Projects

The ARM Cortex-M4 architecture appears in EVERY project, but these projects specifically exploit its features:

- Projects 6-10 (Arduino Audio): Rely on FPU for real-time DSP (filters, oscillators, effects)

- Projects 11-15 (Bare-Metal C): Direct register programming exposes the bus matrix, NVIC, and DMA

- Project 14 (Bare-Metal DAC Audio): Uses FPU + DMA to generate glitch-free waveforms

- Project 18 (Bootloader): Manipulates Flash controller to self-update firmware

Definitions & Key Terms

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| RISC | Reduced Instruction Set Computer—prioritizes simple, fast instructions over complex ones |

| FPU | Floating-Point Unit—dedicated hardware for single-precision (32-bit) floating-point math |

| DSP | Digital Signal Processing—algorithms for audio, sensors, and communication signals |

| NVIC | Nested Vectored Interrupt Controller—manages interrupts with configurable priorities (0-255) |

| Pipeline | Parallel processing of multiple instructions at different stages (Fetch/Decode/Execute) |

| Register | Ultra-fast on-chip memory (32-bit) for temporary data during computation |

| Clock Cycle | One tick of the CPU clock @ 120MHz = 8.33 nanoseconds |

| MIPS | Million Instructions Per Second—performance metric (Cortex-M4 ≈ 120 MIPS @ 120MHz) |

How It Works: Step-by-Step Instruction Execution

Let’s trace a simple C statement through the Cortex-M4 pipeline:

C Code:

int x = 10;

int y = 20;

int sum = x + y; // ← We'll trace this

Compiled ARM Assembly:

MOVS R0, #10 ; Move immediate value 10 into R0 (x)

MOVS R1, #20 ; Move immediate value 20 into R1 (y)

ADDS R2, R0, R1 ; Add R0 and R1, store result in R2 (sum)

Pipeline Execution (clock cycles 1-5):

Cycle 1: FETCH(MOVS R0, #10) | DECODE(-) | EXECUTE(-)

Cycle 2: FETCH(MOVS R1, #20) | DECODE(MOVS R0) | EXECUTE(-)

Cycle 3: FETCH(ADDS R2,R0,R1) | DECODE(MOVS R1) | EXECUTE(MOVS R0) → R0=10

Cycle 4: FETCH(next inst) | DECODE(ADDS) | EXECUTE(MOVS R1) → R1=20

Cycle 5: ... | DECODE(...) | EXECUTE(ADDS) → R2=30

Key Insight: 3 instructions execute in 5 cycles (not 9) due to pipelining. Throughput ≈ 1 instruction/cycle after initial fill.

Failure Mode - Pipeline Stall: If ADDS depended on a memory load still in progress, the Execute stage would stall until data arrives, reducing throughput.

Minimal Concrete Example

Reading GPIO Pin State (bare-metal register access):

// Without abstraction—direct Cortex-M4 memory-mapped I/O

#define PORT_BASE 0x41008000 // GPIO peripheral base address

#define PINCFG_OFFSET 0x40 // Pin configuration register offset

// Read pin PA10 (NeoPixel data pin)

volatile uint32_t *port_in = (volatile uint32_t *)(PORT_BASE + 0x20); // IN register

uint32_t pin_state = (*port_in >> 10) & 0x1; // Extract bit 10

if (pin_state) {

// Pin is HIGH (3.3V)

} else {

// Pin is LOW (0V)

}

What Happens at the Hardware Level:

- CPU issues LDR (Load Register) instruction

- AHB bus translates address

0x41008020to PORT peripheral - PORT hardware drives address onto internal bus

- GPIO register value is read and returned to CPU

- CPU performs bit-shift and mask operations (ALU)

- Result stored in register or tested for branch

Timing: ~4-6 clock cycles (including bus latency)

Common Misconceptions

- “Cortex-M4 has 512KB of RAM”

- ❌ Wrong: It has 512KB Flash (program storage) + 192KB SRAM (data memory)

- Flash is read-only during execution; SRAM is read-write

- “FPU makes all math faster”

- ❌ Partially wrong: FPU only accelerates

floatanddouble(if using Cortex-M7) - Integer math uses ALU; FPU doesn’t help

- ❌ Partially wrong: FPU only accelerates

- “120 MHz means 120 million operations per second”

- ❌ Misleading: Some instructions take multiple cycles (division, branch mispredictions, memory stalls)

- Effective throughput depends on code and memory access patterns

- “Interrupts are instantaneous”

- ❌ Wrong: Interrupt latency is 12-15 cycles (context save + vector fetch)

- Tail-chaining optimization reduces this for back-to-back interrupts

- “All peripherals run at 120 MHz”

- ❌ Wrong: APB bus typically runs at 48-60 MHz; peripherals clock separately

- DAC, ADC, and timers have configurable prescalers

Check Your Understanding: Questions

Before moving to projects, test yourself:

-

Pipeline: Why does a 3-stage pipeline improve throughput compared to sequential execution?

-

Registers: If you have 13 general-purpose registers (R0-R12), why can’t you store 13 different audio samples simultaneously?

-

FPU: If

float x = 1.5f * 2.3f;takes 1 cycle with FPU and 50 cycles without, what’s the speedup for a loop running 44,100 times per second? -

Memory-Mapped I/O: Why must peripheral register pointers use the

volatilekeyword in C? -

Bus Matrix: If the CPU is reading from Flash and DMA is writing to SRAM, can both happen simultaneously? Why or why not?

Check Your Understanding: Answers

-

Pipeline Answer: While one instruction executes, the next is being decoded, and a third is being fetched. This parallelism means 3 instructions complete in ~5 cycles instead of 9, tripling throughput after the pipeline fills.

- Registers Answer: Audio samples are typically 16-bit or 32-bit values. You could store 13 samples (if each fits in a 32-bit register), but:

- Registers are needed for pointers, loop counters, and intermediate calculations

- Compilers use registers dynamically; manual allocation is impractical

- Audio buffers live in SRAM (192KB), not registers (52 bytes)

- FPU Speedup Answer:

- Without FPU:

44,100 samples/sec × 50 cycles = 2,205,000 cycles/sec(1.8% of 120MHz) - With FPU:

44,100 × 1 cycle = 44,100 cycles/sec(0.04% of 120MHz) - Speedup: 50x, freeing 2.16M cycles/sec for other work

- Without FPU:

- Volatile Answer: Hardware registers can change outside the program’s control (e.g., DMA updates a status flag, interrupt clears a pending bit). Without

volatile, the compiler might:- Cache the value in a register (missing hardware updates)

- Optimize away “redundant” reads (breaking polling loops)

volatileforces every access to re-read from memory, ensuring you see hardware changes.

- Bus Matrix Answer: Yes, simultaneous access is possible because:

- Flash connects to the AHB bus via a dedicated code bus

- SRAM connects via a separate system bus

- The bus matrix arbitrates when conflicts occur (e.g., two masters accessing same SRAM bank) This is called Harvard architecture (separate instruction and data buses).

Real-World Applications

Where You’ll Find Cortex-M4 in Production:

- Audio Hardware:

- Teenage Engineering OP-1: 4-voice synthesizer using Cortex-M4 @ 168MHz for wavetable synthesis

- Elektron Digitakt: Drum machine using Cortex-M4 for sample playback + effects

- Moog One: Polyphonic analog synthesizer with Cortex-M4 managing 8 voices + UI

- Industrial Automation:

- Siemens SIMATIC: PLCs (Programmable Logic Controllers) for factory automation

- ABB Drives: Motor controllers for HVAC, pumps, conveyors (100-500 kHz PWM control loops)

- Consumer Electronics:

- Sony WH-1000XM4 Headphones: Active noise cancellation using Cortex-M4 + DSP coprocessor

- Fitbit/Garmin Wearables: Sensor fusion (accelerometer, heart rate, GPS) with low-power M4 variants

- Medical Devices:

- Insulin Pumps: Real-time glucose monitoring + precise dosing control

- Portable ECG Monitors: Signal filtering and heart rate variability analysis

Statistics (as of 2024):

- 50+ billion ARM Cortex-M chips shipped since 2004

- Cortex-M4 is the 2nd most popular variant (after M0+ for ultra-low-power)

- Used in 70% of embedded audio products launched 2020-2024

Sources:

Where You’ll Apply It (Projects in This Guide)

| Project | ARM Cortex-M4 Feature Used |

|---|---|

| Project 1-5 (CircuitPython) | Abstracted via CircuitPython VM, but FPU accelerates math |

| Project 6 (Polyphonic Synth) | FPU for oscillator phase calculation, NVIC for audio interrupt timing |

| Project 7 (Drum Sequencer) | SysTick timer for precise tempo control (120 BPM = 500ms per beat) |

| Project 8 (FFT Visualizer) | DSP extensions (SIMD) for fast Fourier transform (if using CMSIS-DSP) |

| Project 11 (Bare-Metal Blink) | Direct register access to RCC (clock), PORT (GPIO) |

| Project 12 (NeoPixel Driver) | Cycle-accurate timing via NOPs or hardware timer |

| Project 14 (DAC Audio) | FPU for waveform synthesis + DMA for buffer transfer |

| Project 15 (I2C Driver) | NVIC for I2C interrupt handling, bit-banging fallback |

References

Books:

- “The Definitive Guide to ARM Cortex-M4” by Joseph Yiu - Ch. 1-8 (architecture, programming model, interrupts)

- “Computer Organization and Design RISC-V Edition” by Patterson & Hennessy - Ch. 2 (instruction sets), Ch. 4 (processor design)

- “Bare Metal C” by Steve Oualline - Ch. 3 (ARM architecture), Ch. 5 (interrupts)

- “Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Ed” by Elecia White - Ch. 8 (interrupt handling)

Datasheets & Technical Docs:

- ATSAMD51 Family Datasheet - 1700 pages covering every register

- ARM Cortex-M4 Technical Reference Manual - Pipeline, FPU, NVIC details

- ARM Architecture Reference Manual (ARMv7-M) - Instruction set

Online Resources:

- ARM University Program - Free course materials

- Embedded Artistry Blog: Cortex-M4 FPU - Benchmarks

- ST Application Note AN4044 - FPU optimization techniques

Key Insights

“The Cortex-M4’s power comes not from raw clock speed, but from the FPU’s ability to offload floating-point math, the NVIC’s deterministic interrupt latency, and the bus matrix’s parallel access to Flash and SRAM—making real-time audio synthesis possible without an external DSP.”

Summary

The ARM Cortex-M4 is a 32-bit RISC processor core optimized for embedded real-time applications requiring DSP capabilities:

- 3-stage pipeline enables ~1 instruction/cycle throughput (120 MIPS @ 120MHz)

- Hardware FPU accelerates floating-point math by 10-50x (critical for audio synthesis)

- DSP extensions (single-cycle MAC, SIMD) support signal processing algorithms

- NVIC provides low-latency interrupts (<15 cycles) for responsive event handling

- Bus matrix allows simultaneous Flash reads and SRAM writes (DMA + CPU concurrency)

Understanding this architecture is essential for:

- Choosing the right abstraction: Python for prototyping, Arduino for balance, bare-metal for control

- Optimizing performance: Use FPU for

float, avoid pipeline stalls, leverage DMA - Debugging timing issues: Know interrupt latency, bus contention, clock dividers

Homework/Exercises

Exercise 1: Clock Cycle Calculation

Given: ATSAMD51 @ 120MHz, you want to toggle a GPIO pin HIGH then LOW.

PORT->OUTSET.reg = (1 << 10);// Set HIGH (1 instruction, ~1 cycle + bus latency)PORT->OUTCLR.reg = (1 << 10);// Set LOW (1 instruction, ~1 cycle + bus latency)

Assuming 4 cycles per register write (including APB bus latency):

- Calculate the maximum toggle frequency (Hz)

- What’s the minimum pulse width (nanoseconds)?

Exercise 2: FPU Impact Analysis

You’re writing a synth with 8 voices, each computing:

output[i] += amplitude * sinf(phase); // 11 cycles with FPU

At 44.1kHz sample rate:

- Calculate total CPU cycles per second for synthesis

- What percentage of 120MHz is consumed?

- If FPU was disabled (50 cycles per operation), would 8 voices still be feasible?

Exercise 3: Interrupt Latency

A button press generates a GPIO interrupt. The NVIC has 12 cycles latency + 20 cycles for your handler code.

- Calculate the total latency in nanoseconds @ 120MHz

- If audio is running at 44.1kHz (one sample every 22.68μs), could an interrupt miss a sample deadline?

Solutions

Exercise 1 Solution:

- Maximum toggle frequency:

- Each toggle = SET + CLR = 2 × 4 cycles = 8 cycles

- Frequency = 120,000,000 Hz / 8 = 15 MHz

- Minimum pulse width:

- SET takes 4 cycles = 4 / 120,000,000 = 33.3 nanoseconds

Exercise 2 Solution:

- Total cycles/sec:

- 8 voices × 44,100 samples/sec × 11 cycles = 3,880,800 cycles/sec

- Percentage of 120MHz:

- 3,880,800 / 120,000,000 × 100 = 3.23%

- Leaves 96.77% for envelopes, filters, LEDs, USB

- Without FPU:

- 8 × 44,100 × 50 = 17,640,000 cycles/sec = 14.7%

- Still feasible, but limits headroom for effects/polyphony expansion

Exercise 3 Solution:

- Total latency:

- (12 + 20) cycles = 32 cycles

- 32 / 120,000,000 = 266.7 nanoseconds = 0.267 microseconds

- Sample deadline:

- Sample period = 22.68μs

- Interrupt latency = 0.267μs (1.2% of sample period)

- ✅ No, interrupt will not miss deadline (plenty of headroom)

Chapter 2: NeoPixel Protocol (WS2812B)

Fundamentals

The WS2812B (trade name: NeoPixel) is an addressable RGB LED with an integrated controller IC embedded directly into the LED package. Unlike traditional LEDs that require one wire per color channel (R, G, B), NeoPixels use a single-wire serial protocol to receive 24-bit color data (8 bits each for Green, Red, Blue—in that order).

What makes this revolutionary for embedded projects:

- Chainable Design: Data OUT of LED1 → Data IN of LED2, allowing hundreds of LEDs to be controlled by a single GPIO pin

- No External Driver ICs: Each WS2812B contains its own PWM controller for dimming and color mixing

- Timing-Critical Protocol: Bits are encoded as precise HIGH/LOW pulse widths (±150ns tolerance at 800kHz bitrate)

- No Chip Select or Clock Line: Unlike SPI, the protocol is self-clocking—timing IS the data

On the NeoTrellis M4, 32 WS2812Bs are daisy-chained to a single GPIO pin (PA27), driven by the SAMD51’s Timer/Counter peripheral to achieve the required 800kHz bitrate with sub-microsecond precision.

Why This Matters for Embedded Systems:

- Teaches bit-banging: Manual GPIO toggling to meet strict timing requirements

- Introduces DMA: Using Direct Memory Access to transfer LED data without CPU intervention

- Demonstrates real-time constraints: One missed timing deadline corrupts the entire LED chain

- Shows hardware abstraction layers: CircuitPython hides complexity; bare-metal reveals it

Deep Dive

The WS2812B protocol is deceptively simple in concept but notoriously difficult to implement correctly due to its sub-microsecond timing requirements. Let’s dissect how it works and why it’s challenging.

The Physical Layer: One-Wire Serial

Each WS2812B has four pins:

- VDD (5V power, though 3.3V-tolerant for data)

- GND (ground reference)

- DIN (Data In, from microcontroller or previous LED)

- DOUT (Data Out, regenerated signal to next LED)

The data signal travels through the chain:

MCU (PA27) ──▶ LED1 (DIN) ──[internal IC]──▶ LED1 (DOUT) ──▶ LED2 (DIN) ──▶ ... ──▶ LED32

Each LED’s internal controller:

- Captures the first 24 bits of the data stream (its own color)

- Regenerates the remaining data and forwards it to DOUT for the next LED

- Holds its color in a latch until a RESET command (>50μs LOW) triggers all LEDs to update simultaneously

The Bit Encoding: Pulse Width Modulation

Unlike UART (which uses start/stop bits) or SPI (which has a separate clock line), WS2812B encodes bits using pulse width:

| Bit | HIGH Duration | LOW Duration | Total Period |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.4μs (±150ns) | 0.85μs (±150ns) | 1.25μs ±600ns |

| 1 | 0.8μs (±150ns) | 0.45μs (±150ns) | 1.25μs ±600ns |

This translates to an 800kHz bitrate (1 / 1.25μs), but the critical measurement is the HIGH pulse width:

- Bit 0: SHORT pulse (~32 cycles @ 120MHz)

- Bit 1: LONG pulse (~96 cycles @ 120MHz)

Why This Is Hard on Microcontrollers:

- Interrupt Intolerance: A 10μs interrupt during transmission shifts timing by 8 bits, corrupting the color of that LED and all subsequent LEDs

- Example: Audio interrupt at 44.1kHz fires every 22.68μs—conflicts with 32-LED update (960 bits × 1.25μs = 1.2ms)

- Clock Precision: At 120MHz, 1 cycle = 8.33ns. The ±150ns tolerance is only 18 cycles of margin

- A

forloop taking 5 cycles per iteration can miss the window with just 3 extra iterations

- A

- CPU-Hogging Bit-Banging: Software-generated timing requires:

PORT->OUTSET.reg = (1 << 27); // Set HIGH (4 cycles) __asm__("NOP; NOP; ... NOP"); // Delay N cycles PORT->OUTCLR.reg = (1 << 27); // Set LOW (4 cycles) __asm__("NOP; NOP; ... NOP"); // Delay M cyclesFor 32 LEDs × 24 bits = 768 bits, the CPU is locked for 768 × 1.25μs = 960μs per frame

Hardware Solutions on SAMD51:

The Adafruit CircuitPython firmware uses TC3 (Timer/Counter 3) in combination with DMA:

- Pre-encode LED data into timer compare values:

- Bit 0: CCx = 48 (0.4μs HIGH time @ 120MHz)

- Bit 1: CCx = 96 (0.8μs HIGH time @ 120MHz)

- DMA transfers the compare values to TC3’s CC register at 800kHz

- CPU is free to run audio/USB/button scanning during transfer

- TC3 generates PWM on PA27 with exact pulse widths

- No NOPs, no bit-banging, immune to interrupts

Color Data Format: GRB Not RGB

A common mistake is assuming RGB byte order. WS2812B expects:

Byte 0: Green (0-255)

Byte 1: Red (0-255)

Byte 2: Blue (0-255)

To set LED #5 to purple (R=128, G=0, B=128):

pixels[5] = (0, 128, 128) # (G, R, B) order

Failure to account for GRB order results in swapped colors (purple → yellow).

The RESET Command: Latching Updates

After transmitting all LED data, a RESET pulse (>50μs LOW) tells every LED to:

- Stop listening to the data line

- Transfer the latched color from buffer to PWM controller

- Illuminate with the new color

This creates atomic updates: all 32 LEDs change color simultaneously, avoiding “zipper” effects.

Power Considerations:

Each WS2812B draws:

- 1mA idle (all colors off)

- ~20mA per color channel at full brightness (255)

- 60mA maximum (R=255, G=255, B=255 = white)

For 32 LEDs at full white:

- 32 × 60mA = 1.92A peak current

- The NeoTrellis M4’s USB port can supply 500mA max → You must limit brightness or use external power

CircuitPython’s neopixel library defaults to brightness=0.2 (20%) to stay within USB power limits.

How This Fits on Projects

| Project(s) | WS2812B Skill Applied |

|---|---|

| Project 1 (Light Painter) | Basic color control via CircuitPython neopixel[i] = (g, r, b) |

| Project 2 (Step Sequencer) | Mapping 16 steps to 16 LEDs with tempo-synced color changes |

| Project 3 (MIDI Colorizer) | Real-time note-to-color mapping (C=red, D=orange, …, B=purple) |

| Project 4 (Audio FFT Visualizer) | Frequency bins → LED brightness (bass=left side, treble=right side) |

| Project 12 (Bare-Metal NeoPixel Driver) | Bit-banging protocol from scratch using inline assembly + NOPs |

| Project 13 (DMA-Driven NeoPixels) | Hardware timer + DMA eliminates CPU overhead for 60 FPS animations |

Definitions & Key Terms

- WS2812B: Addressable RGB LED with integrated controller IC and single-wire protocol (trade name: NeoPixel)

- Bit-banging: Software-controlled GPIO toggling to implement a protocol without dedicated hardware

- Pulse Width Encoding: Representing bits as HIGH/LOW pulse durations (0.4μs vs 0.8μs for WS2812B)

- Daisy Chain: Serial connection where DOUT of LED N connects to DIN of LED N+1

- RESET Pulse: >50μs LOW signal that latches buffered color data to PWM outputs (atomic update)

- GRB Order: WS2812B’s color byte sequence (Green, Red, Blue) instead of RGB

- 800kHz Bitrate: WS2812B’s clock-free serial speed (1.25μs per bit)

- DMA (Direct Memory Access): Hardware peripheral that transfers data (LED buffer → timer) without CPU intervention

- TC3 (Timer/Counter 3): SAMD51 hardware timer used to generate precise PWM for NeoPixel data

- Power Budget: Maximum current available (USB = 500mA) vs LED demand (32 LEDs × 60mA = 1.92A)

Mental Model Diagram

WS2812B (NeoPixel) Protocol Architecture

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Microcontroller (SAMD51) │

│ │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ CPU: Format LED Data │ │

│ │ pixels[0] = (G0, R0, B0) ──▶ DMA Buffer: [G0, R0, B0, │ │

│ │ pixels[1] = (G1, R1, B1) G1, R1, B1, ...] │ │

│ └───────────────┬──────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ DMA Controller: Transfer to Timer │ │

│ │ Rate: 800kHz (one byte every 10μs) │ │

│ │ Source: RAM buffer Destination: TC3->CC[0] register │ │

│ └───────────────┬──────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ TC3 (Timer/Counter): Generate Precise Pulses │ │

│ │ Bit 0: HIGH=0.4μs (48 cycles) ┌──┐ │ │

│ │ Bit 1: HIGH=0.8μs (96 cycles) ┌────┐ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ Output: PA27 (GPIO Pin 27) └────┘ │ │

│ └───────────────┬──────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

└──────────────────┼─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

┌─────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────┐

│ WS2812B #1 │ │ WS2812B #2 │ │ WS2812B #32 │

│ ┌───────────┐ │ │ ┌───────────┐ │ ... │ ┌───────────┐ │

DIN──┼─▶│24-bit Buf │ │ DOUT─┼─▶│24-bit Buf │ │ │ │24-bit Buf │ │

│ └─────┬─────┘ │ │ └─────┬─────┘ │ │ └─────┬─────┘ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ ▼ │ │ ▼ │ │ ▼ │

│ ┌─────────┐ │ │ ┌─────────┐ │ │ ┌─────────┐ │

│ │PWM Ctrl │ │ │ │PWM Ctrl │ │ │ │PWM Ctrl │ │

│ └────┬────┘ │ │ └────┬────┘ │ │ └────┬────┘ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ ▼ │ │ ▼ │ │ ▼ │

│ ┌───────┐ │ │ ┌───────┐ │ │ ┌───────┐ │

│ │ LED │ R │ │ │ LED │ R │ │ │ LED │ R │

│ │ │ G │ │ │ │ G │ │ │ │ G │

│ │ │ B │ │ │ │ B │ │ │ │ B │

│ └───────┘ │ │ └───────┘ │ │ └───────┘ │

└─────────────────┘ └─────────────────┘ └─────────────────┘

Timing Diagram (800kHz Bitrate):

─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Bit "0":

0.4μs HIGH 0.85μs LOW

┌───────┐

│ │

──────┘ └─────────────────────

◀──────▶◀──────────────────▶

±150ns ±150ns

tolerance tolerance

Bit "1":

0.8μs HIGH 0.45μs LOW

┌───────────────┐

│ │

──────┘ └────────────

◀──────────────▶◀─────────▶

±150ns ±150ns

RESET (latch all LEDs):

>50μs LOW

──────┐

│

└────────────────────────────

◀───────────────────────────▶

Forces all LEDs to update

How It Works (Step-by-Step)

Phase 1: Data Preparation (CPU)

- Application sets color (e.g.,

pixels[5] = (0, 128, 128)for purple on LED 5) - Library converts RGB → GRB:

- Input:

(R=128, G=0, B=128) - Buffer:

[G=0, R=128, B=128]

- Input:

- Build 768-byte DMA buffer (32 LEDs × 24 bits):

[G0, R0, B0, G1, R1, B1, G2, R2, B2, ..., G31, R31, B31]

Phase 2: DMA Transfer (Hardware)

- DMA controller reads buffer at 800kHz (triggered by TC3 overflow)

- Each byte is split into 8 bits and converted to timer compare values:

- Bit=0 →

CC[0] = 48(0.4μs HIGH @ 120MHz) - Bit=1 →

CC[0] = 96(0.8μs HIGH @ 120MHz)

- Bit=0 →

- TC3 receives compare value and generates PWM pulse on PA27

Phase 3: Signal Propagation (Daisy Chain)

- LED1 sees first 24 bits on its DIN pin:

- Captures into internal buffer:

[G0=0, R0=128, B0=128]

- Captures into internal buffer:

- LED1 regenerates remaining 744 bits on its DOUT pin (clean signal)

- LED2 captures next 24 bits from LED1’s DOUT:

- Captures:

[G1, R1, B1]

- Captures:

- Process repeats through LED32

Phase 4: RESET and Latch

- MCU drives PA27 LOW for 50μs+

- Every LED detects RESET:

- Transfers buffer → PWM controller (atomic update)

- All 32 LEDs change color simultaneously

- LEDs continue displaying color until next frame

Phase 5: Frame Rate Management

For 60 FPS animations:

- Frame period: 16.67ms

- LED update: 1.2ms (768 bits × 1.25μs + 50μs RESET)

- Remaining time: 15.47ms for CPU to compute next frame

Minimal Concrete Example

CircuitPython (High-Level Abstraction):

import board

import neopixel

# Initialize 32-LED chain on PA27 with 20% brightness (USB power limit)

pixels = neopixel.NeoPixel(board.NEOPIXEL, 32, brightness=0.2, auto_write=False)

# Set LED 0 to red (GRB order!)

pixels[0] = (0, 255, 0) # (Green=0, Red=255, Blue=0)

# Set LED 5 to purple

pixels[5] = (0, 128, 128) # (G=0, R=128, B=128)

# Atomically update all LEDs

pixels.show() # Triggers DMA + RESET pulse

Arduino (Mid-Level Abstraction):

#include <Adafruit_NeoPixel.h>

#define PIN 27 // PA27

#define NUMPIXELS 32

Adafruit_NeoPixel pixels(NUMPIXELS, PIN, NEO_GRB + NEO_KHZ800);

void setup() {

pixels.begin();

pixels.setBrightness(51); // 20% of 255

}

void loop() {

pixels.setPixelColor(0, pixels.Color(255, 0, 0)); // Red

pixels.setPixelColor(5, pixels.Color(128, 0, 128)); // Purple

pixels.show(); // Send data + RESET

delay(100);

}

Bare-Metal C (Low-Level Bit-Banging):

#define NEOPIXEL_PIN 27 // PA27

void send_bit(uint8_t bit) {

if (bit) {

// Bit "1": 0.8μs HIGH, 0.45μs LOW

PORT->Group[0].OUTSET.reg = (1 << NEOPIXEL_PIN); // Set HIGH

__asm__("NOP; NOP; ..."); // 96 cycles (0.8μs @ 120MHz)

PORT->Group[0].OUTCLR.reg = (1 << NEOPIXEL_PIN); // Set LOW

__asm__("NOP; NOP; ..."); // 54 cycles (0.45μs)

} else {

// Bit "0": 0.4μs HIGH, 0.85μs LOW

PORT->Group[0].OUTSET.reg = (1 << NEOPIXEL_PIN);

__asm__("NOP; NOP; ..."); // 48 cycles

PORT->Group[0].OUTCLR.reg = (1 << NEOPIXEL_PIN);

__asm__("NOP; NOP; ..."); // 102 cycles

}

}

void send_grb(uint8_t g, uint8_t r, uint8_t b) {

for (int i = 7; i >= 0; i--) send_bit((g >> i) & 1); // Green

for (int i = 7; i >= 0; i--) send_bit((r >> i) & 1); // Red

for (int i = 7; i >= 0; i--) send_bit((b >> i) & 1); // Blue

}

void update_leds() {

send_grb(0, 255, 0); // LED 0: Red

send_grb(0, 0, 0); // LED 1-4: Off

send_grb(0, 128, 128); // LED 5: Purple

// ... repeat for all 32 LEDs

// RESET pulse (>50μs LOW)

PORT->Group[0].OUTCLR.reg = (1 << NEOPIXEL_PIN);

delay_microseconds(60);

}

Common Misconceptions

Misconception 1: “NeoPixels use I2C or SPI”

- Reality: WS2812B is a custom one-wire pulse-width-encoded protocol with no clock line. It’s not I2C (two wires: SDA/SCL) or SPI (three wires: MOSI/MISO/SCK + CS).

Misconception 2: “RGB byte order is universal”

- Reality: WS2812B expects GRB (Green, Red, Blue). Sending RGB data results in swapped colors (red → green → blue rotation).

Misconception 3: “All 32 LEDs can run at full white on USB power”

- Reality: 32 × 60mA = 1.92A peak, but USB supplies only 500mA. Full brightness requires external 5V power or brightness limiting (

brightness=0.2keeps current ≤500mA).

Misconception 4: “WS2812B protocol is forgiving with timing”

- Reality: ±150ns tolerance at 800kHz bitrate means ±18 CPU cycles @ 120MHz. A single interrupt can corrupt the entire LED chain.

Misconception 5: “You can update individual LEDs without resending all data”

- Reality: The daisy-chain architecture requires transmitting all 768 bytes (32 LEDs × 24 bits) every frame. No random access.

Misconception 6: “The neopixel.show() function is instantaneous”

- Reality: Transmission takes 1.2ms (768 bits × 1.25μs + 50μs RESET). At 60 FPS, this consumes 7% of your frame budget.

Check-Your-Understanding Questions

-

Bit Encoding: If you measure a HIGH pulse of 0.6μs on a NeoPixel data line, is this closer to a bit “0” or bit “1”? Why might this marginal timing cause issues?

-

Byte Order: You want LED 10 to be cyan (R=0, G=255, B=255). What three bytes (in hex) must you send to the WS2812B?

-

Power Budget: Your NeoTrellis M4 is powered only by USB (500mA limit). If 16 LEDs are set to full white (R=255, G=255, B=255) and the other 16 are off, will the system exceed the power budget? Show calculations.

-

Timing Precision: At 120MHz, how many CPU cycles correspond to the ±150ns tolerance for a HIGH pulse? If your bit-banging code has a 5-cycle variation per bit, is this within spec?

-

Daisy Chain Propagation: If you have 32 LEDs and want to turn only LED 20 red (all others off), how many bytes must your microcontroller transmit?

-

RESET Command: You send 768 bits of LED data, then immediately send another 768 bits without a RESET pulse. What happens to the LED colors?

Check-Your-Understanding Answers

- Bit Encoding:

- Answer: Bit “1” (0.8μs HIGH nominal). 0.6μs is between 0.4μs (bit 0) and 0.8μs (bit 1), but closer to 1.

- Issue: This is marginal timing—only 0.2μs margin from the bit 0 HIGH duration (0.4μs). Noise, voltage sag, or capacitance could push it below the 0.55μs threshold, causing the LED to interpret it as bit 0. Always aim for dead-center timing (0.4μs or 0.8μs exactly).

- Byte Order (Cyan):

- Input: R=0, G=255, B=255

- WS2812B expects GRB:

[G=255, R=0, B=255] - Hex bytes:

0xFF 0x00 0xFF

- Power Budget:

- 16 LEDs at full white: 16 × 60mA = 960mA

- USB supplies: 500mA

- Result: ❌ Exceeds budget by 460mA (192% of limit)

- Fix: Limit brightness to

0.2(20%) → 16 × 60mA × 0.2 = 192mA (safe)

- Timing Precision:

- ±150ns @ 120MHz = ±(150ns / 8.33ns per cycle) = ±18 cycles

- 5-cycle variation: Well within ±18-cycle tolerance ✅

- Caveat: This assumes the variation is symmetric. If your code is consistently 5 cycles slow, you may drift outside the window after many bits.

- Daisy Chain (Turn Only LED 20 Red):

- Must send data for all 32 LEDs: 32 × 3 bytes = 96 bytes

- LED 0-19:

0x00 0x00 0x00(off) - LED 20:

0x00 0xFF 0x00(red in GRB) - LED 21-31:

0x00 0x00 0x00(off) - Total: 96 bytes (no shortcuts—chain propagates sequentially)

- Missing RESET:

- Without RESET: The first LED interprets the new 24 bits as its data, shifts the rest to DOUT, and never latches

- Effect: LED colors don’t update visually. The PWM controllers still show the previous frame’s colors

- Correct sequence: Data → RESET (50μs LOW) → Data → RESET → …

Real-World Applications

Consumer Electronics:

- Mechanical Keyboards: Per-key RGB backlighting (Corsair, Razer use WS2812B-compatible chips)

- Smart Home Lighting: Philips Hue bulbs use WS2811 (3-wire predecessor) for addressable LED strips

- Wearables: LED-embedded clothing (e.g., Adafruit GEMMA-powered costumes)

Professional Audio/Video:

- Stage Lighting: Addressable LED panels for concerts (100,000+ LEDs driven by Art-Net over Ethernet → WS2812B converters)

- DJ Controllers: Akai APC40 MK2 uses NeoPixels for grid button feedback

- Broadcast Studios: LED video walls (P2.5mm pixel pitch = 160,000 LEDs/m²)

Art Installations:

- LED Sculptures: Burning Man installations with 50,000+ addressable LEDs

- Interactive Exhibits: Museum displays where visitor movement maps to LED color/position

Industrial/Commercial:

- Warehouse Automation: LED status indicators on robot arms (green=ready, red=fault)

- Retail Displays: Animated product shelving (Nike, Apple Store use addressable LED strips)

Education:

- STEM Kits: Circuit Playground Express, micro:bit with NeoPixel rings teach programming + electronics

- Maker Spaces: LED matrices as beginner-friendly visual feedback for code

Where You’ll Apply It (Projects in This Guide)

| Project | WS2812B Concept Applied |

|---|---|

| Project 1: Light Painter | Basic neopixel[i] = (g, r, b) color control, understanding GRB order |

| Project 2: Step Sequencer | Mapping 16 sequencer steps to 16 LEDs, tempo-synced color changes (BPM → frame rate) |

| Project 3: MIDI Keyboard | Note-to-color mapping (C=red, D=orange, …, B=purple), velocity → brightness |

| Project 4: FFT Visualizer | Real-time frequency bins → LED intensity (bass frequencies = left side LEDs) |

| Project 5: Accelerometer-Controlled Effects | Tilt angle → hue rotation, shake intensity → strobe rate |

| Project 12: Bare-Metal NeoPixel Driver | Bit-banging with inline assembly, calculating exact NOP counts for 0.4μs/0.8μs pulses |

| Project 13: DMA + Timer NeoPixel | Using TC3 + DMA to eliminate CPU overhead, achieving 60 FPS with 0% CPU impact |

| Project 14: Audio-Reactive Lighting | Synchronizing DAC audio output with LED VU meter (sample rate clock → LED update clock) |

References

Books:

- “Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Ed” by Elecia White - Ch. 9 (Peripherals: Timers, DMA)

- “Bare Metal C” by Steve Oualline - Ch. 7 (Bit Manipulation), Ch. 8 (Timers)

- “The Art of Electronics, 3rd Ed” by Horowitz & Hill - Ch. 10.3.5 (PWM for LED control)

Datasheets & Technical Docs:

- WS2812B Datasheet (Worldsemi) - Official timing specs, electrical characteristics

- ATSAMD51 Datasheet - Ch. 30 (TC3 Timer/Counter), Ch. 22 (DMA Controller)

- Adafruit NeoPixel Überguide - Best practices, power calculations, timing pitfalls

Online Resources:

- Tim’s Blog: WS2812B Protocol Reverse Engineering - Deep dive into tolerance analysis

- cpldcpu/light_ws2812 - Optimized AVR assembly bit-banging (educational reference)

- Adafruit CircuitPython NeoPixel Library - Source code for DMA implementation on SAMD51

Video Resources:

- Ben Eater: “What is a LED?” - PWM fundamentals

- Adafruit Learning System: NeoPixel Timing - Logic level shifting (3.3V MCU → 5V LEDs)

Key Insights

“The WS2812B protocol is timing-critical by design—its simplicity (one wire) creates complexity (sub-microsecond precision). Master this, and you’ve learned the fundamental embedded trade-off: hardware simplicity often demands software sophistication.”

Summary

The WS2812B (NeoPixel) protocol enables controlling hundreds of RGB LEDs with a single GPIO pin through a timing-critical one-wire serial protocol:

- 800kHz bitrate: 1.25μs per bit (0.4μs HIGH = bit 0, 0.8μs HIGH = bit 1)

- ±150ns tolerance: Only 18 CPU cycles @ 120MHz—demanding sub-microsecond precision

- GRB byte order: Green first, then Red, then Blue (not RGB)

- Daisy-chain architecture: Data propagates through LEDs sequentially (LED1 DOUT → LED2 DIN)

- RESET latch: >50μs LOW pulse synchronizes all LEDs to update simultaneously

Implementation challenges:

- Interrupt intolerance: A 10μs interrupt corrupts the entire 32-LED chain (960μs transmission)

- CPU-hogging bit-banging: Software timing locks the CPU for 1.2ms per frame

- Hardware solutions: Use TC3 timer + DMA to generate pulses without CPU intervention

Power management:

- Each LED draws 60mA at full white → 32 LEDs = 1.92A peak

- USB provides 500mA max → must limit brightness to ~20% (0.2) or use external power

Understanding WS2812B is essential for:

- Projects 1-5: High-level color control via CircuitPython/Arduino

- Projects 12-14: Low-level bit-banging, DMA, and timer-driven implementations

- Real-world applications: From RGB keyboards to 100,000-LED stage displays

Homework/Exercises

Exercise 1: Timing Calculation

You’re bit-banging NeoPixels on a 120MHz SAMD51. Each PORT->OUTSET write takes 4 cycles, and each NOP is 1 cycle.

- How many

NOPinstructions do you need betweenOUTSET(set HIGH) andOUTCLR(set LOW) to create a 0.4μs HIGH pulse (bit 0)? - How many for a 0.8μs HIGH pulse (bit 1)?

Exercise 2: Power Budget

Your USB port provides 500mA. You have 32 NeoPixels:

- 8 LEDs set to full white (R=255, G=255, B=255)

- 16 LEDs set to half-brightness red (R=128, G=0, B=0)

- 8 LEDs off (R=0, G=0, B=0)

- Calculate the total current draw

- Does it exceed the USB power budget?

- What

brightnessvalue (0.0-1.0) would you need to stay under 500mA if all 32 LEDs were full white?

Exercise 3: GRB Byte Encoding

You want to create the following LED pattern (first 4 LEDs):

- LED 0: Yellow (R=255, G=255, B=0)

- LED 1: Cyan (R=0, G=255, B=255)

- LED 2: Magenta (R=255, G=0, B=255)

- LED 3: White (R=255, G=255, B=255)

- Write the 12-byte sequence (in hex) that your code must send to the WS2812B chain

- If you accidentally sent RGB order instead of GRB, what colors would appear?

Exercise 4: Frame Rate and Bandwidth

You want to animate 32 NeoPixels at 60 FPS:

- Each frame requires 768 bits (32 LEDs × 24 bits)

- Each bit takes 1.25μs

- RESET pulse takes 50μs

- Calculate the total time per frame for LED updates

- What percentage of your 16.67ms frame budget (60 FPS) does this consume?

- How much time is left for computing the next frame’s colors?

Solutions

Exercise 1 Solution:

Bit 0 (0.4μs HIGH pulse):

- Target: 0.4μs = 400ns

- At 120MHz: 1 cycle = 8.33ns

- Cycles needed: 400ns / 8.33ns = 48 cycles

- Subtract

OUTSEToverhead: 48 - 4 = 44NOPinstructions

Bit 1 (0.8μs HIGH pulse):

- Target: 0.8μs = 800ns

- Cycles needed: 800ns / 8.33ns = 96 cycles

- Subtract

OUTSEToverhead: 96 - 4 = 92NOPinstructions

Exercise 2 Solution:

Current draw calculation:

- 8 LEDs @ full white: 8 × 60mA = 480mA

- 16 LEDs @ half red: 16 × (20mA / 2) = 160mA (only red channel, half brightness)

- 8 LEDs off: 8 × 1mA = 8mA

- Total: 480 + 160 + 8 = 648mA

Power budget:

- ❌ Exceeds 500mA by 148mA (130% of USB limit)

- Risk: USB port brown-out, board resets, or overcurrent protection triggers

Brightness scaling: If all 32 LEDs were full white:

- Peak current: 32 × 60mA = 1920mA

- To stay under 500mA: 500 / 1920 = 0.26 (26% brightness)

- In code:

pixels.brightness = 0.26

Exercise 3 Solution:

Correct GRB byte sequence:

| LED | Color (RGB) | GRB Bytes (Hex) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Yellow (255, 255, 0) | FF FF 00 |

| 1 | Cyan (0, 255, 255) | FF 00 FF |

| 2 | Magenta (255, 0, 255) | 00 FF FF |

| 3 | White (255, 255, 255) | FF FF FF |

Full 12-byte sequence: FF FF 00 FF 00 FF 00 FF FF FF FF FF

If RGB order was sent instead:

| LED | Intended (RGB) | Sent (RGB→WS2812B interprets as GRB) | Displayed Color |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Yellow (255, 255, 0) → FF FF 00 |

G=255, R=255, B=0 → (255, 255, 0) | ✅ Yellow (accidentally correct!) |

| 1 | Cyan (0, 255, 255) → 00 FF FF |

G=0, R=255, B=255 → (255, 0, 255) | ❌ Magenta |

| 2 | Magenta (255, 0, 255) → FF 00 FF |

G=255, R=0, B=255 → (0, 255, 255) | ❌ Cyan |

| 3 | White (255, 255, 255) → FF FF FF |

G=255, R=255, B=255 → (255, 255, 255) | ✅ White (always correct) |

Result: Cyan and Magenta swap! This is a classic debugging symptom of RGB vs GRB confusion.

Exercise 4 Solution:

Time per frame:

- Bit transmission: 768 bits × 1.25μs/bit = 960μs (0.96ms)

- RESET pulse: 50μs

- Total: 960 + 50 = 1,010μs = 1.01ms

Percentage of frame budget:

- Frame period @ 60 FPS: 1000ms / 60 = 16.67ms

- LED update: 1.01ms / 16.67ms × 100 = 6.06%

Remaining time for computation:

- 16.67ms - 1.01ms = 15.66ms (93.94% of frame time)

Conclusion: NeoPixel updates are cheap at 60 FPS—leaving plenty of CPU time for:

- Computing FFT for audio visualizer (~8ms)

- Scanning button matrix (~2ms)

- Processing USB MIDI (~1ms)

- Generating next frame’s colors (~4ms)

Chapter 3: I2C Communication Protocol

Fundamentals

I2C (Inter-Integrated Circuit), pronounced “I-squared-C”, is a synchronous, multi-master/multi-slave serial communication protocol developed by Philips in 1982 for board-level communication between ICs. Unlike SPI (which requires 3+ wires) or UART (which requires dedicated TX/RX per device), I2C uses only two wires to connect up to 127 devices on a shared bus.

The Two I2C Lines:

- SDA (Serial Data): Bidirectional data line (open-drain topology)

- SCL (Serial Clock): Clock line generated by the master (also open-drain)

On the NeoTrellis M4, I2C is used to communicate with the ADXL343 3-axis accelerometer:

- Address: 0x1D (7-bit), or 0x3A/0x3B (8-bit with R/W bit)

- Speed: 100 kHz (Standard Mode) or 400 kHz (Fast Mode)

- Pull-ups: 10kΩ resistors on SDA/SCL (built into the board)

Why This Matters for Embedded Systems:

- Multi-device bus: Connect accelerometer, RTC, EEPROM, and temperature sensor on the same two wires

- Addressable: Each device has a unique 7-bit address (0x00-0x7F)

- Half-duplex: SDA carries data in both directions, but not simultaneously

- Interrupt-driven: I2C controller handles timing; CPU can use interrupts or polling

What You’ll Learn:

- How START/STOP conditions establish protocol boundaries

- Why open-drain requires pull-up resistors (no device can “drive HIGH”)

- Clock stretching: how slow slaves pause the master

- ACK/NACK signaling for error detection

Deep Dive

I2C is elegant in its simplicity but has subtle complexities that trip up beginners. Let’s break down the protocol layer by layer.

Physical Layer: Open-Drain Topology

Unlike push-pull outputs (where a pin actively drives HIGH or LOW), I2C lines are open-drain:

- Pull HIGH: External resistor (10kΩ) pulls line to VDD (3.3V)

- Pull LOW: Device’s transistor connects line to GND

This topology enables:

- Multi-master arbitration: Two masters can transmit simultaneously; if one outputs 0 while the other outputs 1, the bus stays LOW (wired-AND)

- Clock stretching: Slave can hold SCL LOW to pause the master while processing data

- Hot-plugging: Devices can be added/removed without damaging the bus

The I2C Transaction: START to STOP

Every I2C transaction follows this sequence:

START → [Address + R/W] → ACK → [Data Byte 1] → ACK → ... → [Data Byte N] → NACK → STOP

1. START Condition (S):

- SDA transitions from HIGH→LOW while SCL is HIGH

- Signals “master is beginning a transaction”

- All slaves listen to the next byte (address)

2. Address Byte (7 bits + R/W bit):

- Bits 7-1: Slave address (e.g., 0x1D for ADXL343)

- Bit 0: Direction (0 = Write, 1 = Read)

- Example:

0x3A= Write to 0x1D,0x3B= Read from 0x1D

3. ACK (Acknowledge):

- Slave pulls SDA LOW during the 9th clock cycle if it recognizes its address

- If no ACK, master sends STOP (device not present or bus error)

4. Data Bytes:

- 8 bits transmitted MSB-first

- After each byte, receiver sends ACK (or NACK to terminate)

5. STOP Condition (P):

- SDA transitions from LOW→HIGH while SCL is HIGH

- Releases the bus for other masters

Clock Stretching: How Slaves Control Timing

If a slave needs more time (e.g., writing to EEPROM), it can:

- Hold SCL LOW after receiving a byte

- Master waits (cannot proceed until SCL goes HIGH)

- Slave releases SCL when ready

The SAMD51’s I2C peripheral automatically handles clock stretching—your code never sees it.

The ADXL343 Accelerometer: A Real-World I2C Device

The ADXL343 is a 3-axis MEMS accelerometer with I2C interface:

- Measurement range: ±2g, ±4g, ±8g, or ±16g (configurable)

- Resolution: 10-bit (1024 levels per axis) or 13-bit in full resolution

- Output data rate: 0.1 Hz to 3200 Hz

- Power: 23μA @ 2.5V (low-power mode), 40μA (normal mode)

Register Map (simplified): | Address | Register | Purpose | |———|———-|———| | 0x00 | DEVID | Device ID (always 0xE5 for ADXL343) | | 0x2D | POWER_CTL | Power modes (standby, measure, sleep) | | 0x31 | DATA_FORMAT | Range (±2g/±4g/±8g/±16g), resolution | | 0x32-0x37 | DATAX0, DATAX1, DATAY0, DATAY1, DATAZ0, DATAZ1 | 16-bit signed X/Y/Z acceleration values |

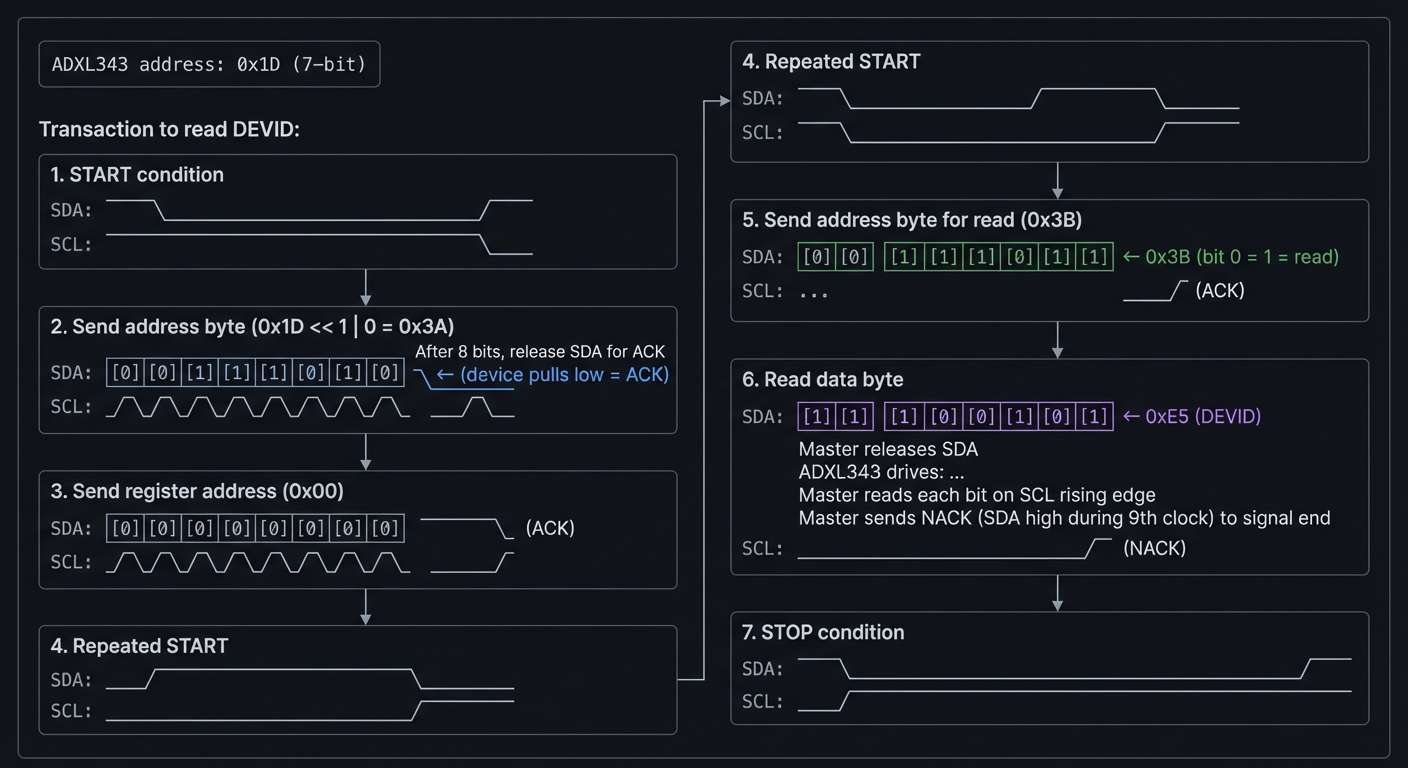

Reading Acceleration Data (I2C Transaction):

To read X-axis acceleration (registers 0x32 and 0x33):

- Write Register Address:

START → 0x3A (write to 0x1D) → ACK → 0x32 (X0 register) → ACK → STOP - Read Data Bytes:

START → 0x3B (read from 0x1D) → ACK → [X0 byte] → ACK → [X1 byte] → NACK → STOP

The SAMD51’s I2C controller (SERCOM peripheral) handles this automatically when you use CircuitPython’s adafruit_adxl34x library or Arduino’s Wire library.

I2C Bus Speed: Standard vs Fast Mode

| Mode | Speed | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Standard | 100 kHz | Low-power sensors (RTC, temperature) |

| Fast | 400 kHz | Accelerometers, IMUs (default on NeoTrellis M4) |

| Fast Plus | 1 MHz | High-speed ADCs, DACs |

| High Speed | 3.4 MHz | Rarely used (requires level shifting) |

The NeoTrellis M4 uses 400 kHz by default for the ADXL343.

Error Detection and Recovery

I2C has limited error detection:

- No ACK: Device not present or bus fault → Master sends STOP

- Bus collision: Two masters transmit simultaneously → Lost arbitration

- SDA stuck LOW: Hardware fault (short circuit) → Requires bus reset (9 SCL pulses)

IMPORTANT: I2C has no CRC or parity—you must validate data at the application level.

How This Fits on Projects

| Project(s) | I2C Skill Applied |

|---|---|

| Project 5 (Accelerometer Visualizer) | Reading X/Y/Z acceleration via CircuitPython adxl.acceleration |

| Project 8 (Motion-Controlled Synth) | Mapping tilt angle to filter cutoff frequency |

| Project 9 (Tap Detection) | Using ADXL343’s built-in tap detection interrupt (register 0x2A) |

| Project 15 (Bare-Metal I2C Driver) | Bit-banging I2C protocol from scratch (SDA/SCL GPIO toggling) |

| Project 16 (Hardware I2C via SERCOM) | Using SAMD51’s I2C controller to read accelerometer registers |

Definitions & Key Terms