Learn M5Stack StickC Plus2: From Zero to IoT Hardware Master

Goal: Deeply understand embedded systems, IoT development, and hardware-software integration through the M5Stack StickC Plus2—a pocket-sized ESP32 powerhouse with display, sensors, wireless connectivity, and expansion capabilities. You’ll learn to harness microcontrollers, master low-power design, build real wireless devices, and understand how modern IoT products work from silicon to cloud.

Why M5Stack StickC Plus2 Matters

In 2016, Espressif Systems released the ESP32—a chip that democratized IoT development by packing WiFi, Bluetooth, dual cores, and rich peripherals into a $4 module. M5Stack took this further, creating development kits that turn the ESP32 into complete, deployable devices.

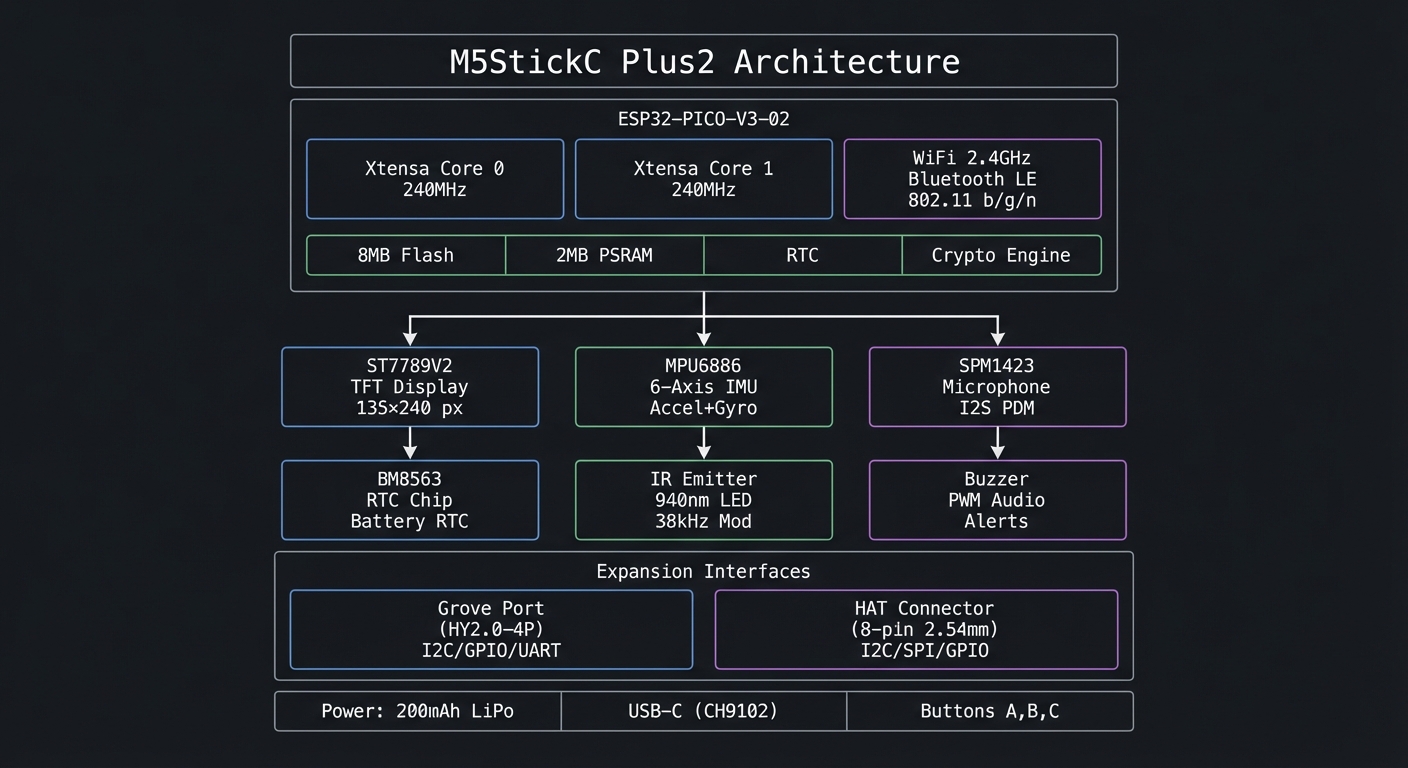

The StickC Plus2 (launched October 2023) represents the evolution of portable embedded computing:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ M5StickC Plus2 Architecture │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ ESP32-PICO-V3-02 │ │

│ │ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ Xtensa │ │ Xtensa │ │ WiFi 2.4GHz │ │ │

│ │ │ Core 0 │ │ Core 1 │ │ Bluetooth LE │ │ │

│ │ │ 240MHz │ │ 240MHz │ │ 802.11 b/g/n │ │ │

│ │ └─────────────┘ └─────────────┘ └─────────────────┘ │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ 8MB Flash │ 2MB PSRAM │ RTC │ Crypto Engine │ │ │

│ │ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ┌───────────────┼───────────────┐ │

│ │ │ │ │

│ ▼ ▼ ▼ │

│ ┌───────────────┐ ┌───────────────┐ ┌───────────────┐ │

│ │ ST7789V2 │ │ MPU6886 │ │ SPM1423 │ │

│ │ TFT Display │ │ 6-Axis IMU │ │ Microphone │ │

│ │ 135×240 px │ │ Accel+Gyro │ │ I2S PDM │ │

│ └───────────────┘ └───────────────┘ └───────────────┘ │

│ │ │ │ │

│ ▼ ▼ ▼ │

│ ┌───────────────┐ ┌───────────────┐ ┌───────────────┐ │

│ │ BM8563 │ │ IR Emitter │ │ Buzzer │ │

│ │ RTC Chip │ │ 940nm LED │ │ PWM Audio │ │

│ │ Battery RTC │ │ 38kHz Mod │ │ Alerts │ │

│ └───────────────┘ └───────────────┘ └───────────────┘ │

│ │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Expansion Interfaces │ │

│ │ ┌────────────────────┐ ┌────────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ Grove Port │ │ HAT Connector │ │ │

│ │ │ (HY2.0-4P) │ │ (8-pin 2.54mm) │ │ │

│ │ │ I2C/GPIO/UART │ │ I2C/SPI/GPIO │ │ │

│ │ └────────────────────┘ └────────────────────────┘ │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Power: 200mAh LiPo │ USB-C (CH9102) │ Buttons A,B,C │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

What Makes This Device Special

- Complete System: Unlike bare ESP32 modules, you get a working product—display, battery, sensors, case—ready to program

- Dual Expansion: Grove (I2C/UART) and HAT (SPI/GPIO) connectors support 100+ modules

- Portable: 54.2×25.5×13.7mm form factor fits in your pocket; wearable as a watch

- Production-Ready: Same hardware can go from prototype to deployed product

- Rich Ecosystem: Arduino, MicroPython, UIFlow (visual programming), and ESP-IDF support

What You’ll Learn Building With It

| Domain | Skills Gained |

|---|---|

| Embedded Programming | C/C++ on bare metal, memory management, interrupts, timers |

| Hardware Interfaces | SPI, I2C, UART, GPIO, ADC, PWM, I2S |

| Wireless Communication | WiFi networking, BLE beacons, MQTT/HTTP protocols |

| Display Graphics | Framebuffers, sprites, animations, UI design |

| Sensor Fusion | IMU data processing, gesture recognition, motion tracking |

| Power Management | Deep sleep, wake sources, battery optimization |

| IoT Architecture | Device-to-cloud, OTA updates, remote control |

Learning Outcomes Overview

This guide takes you from “I can flash a demo” to “I can design a production-grade IoT device.” You will learn how to:

- Build stable firmware that runs for days without crashing.

- Read sensors, filter their noise, and turn raw signals into meaningful data.

- Design responsive UIs on a tiny display without flicker or lag.

- Use WiFi/BLE safely and efficiently, including OTA updates.

- Optimize battery life using deep sleep and event-driven wakeups.

- Integrate external modules through Grove/HAT with correct bus timing.

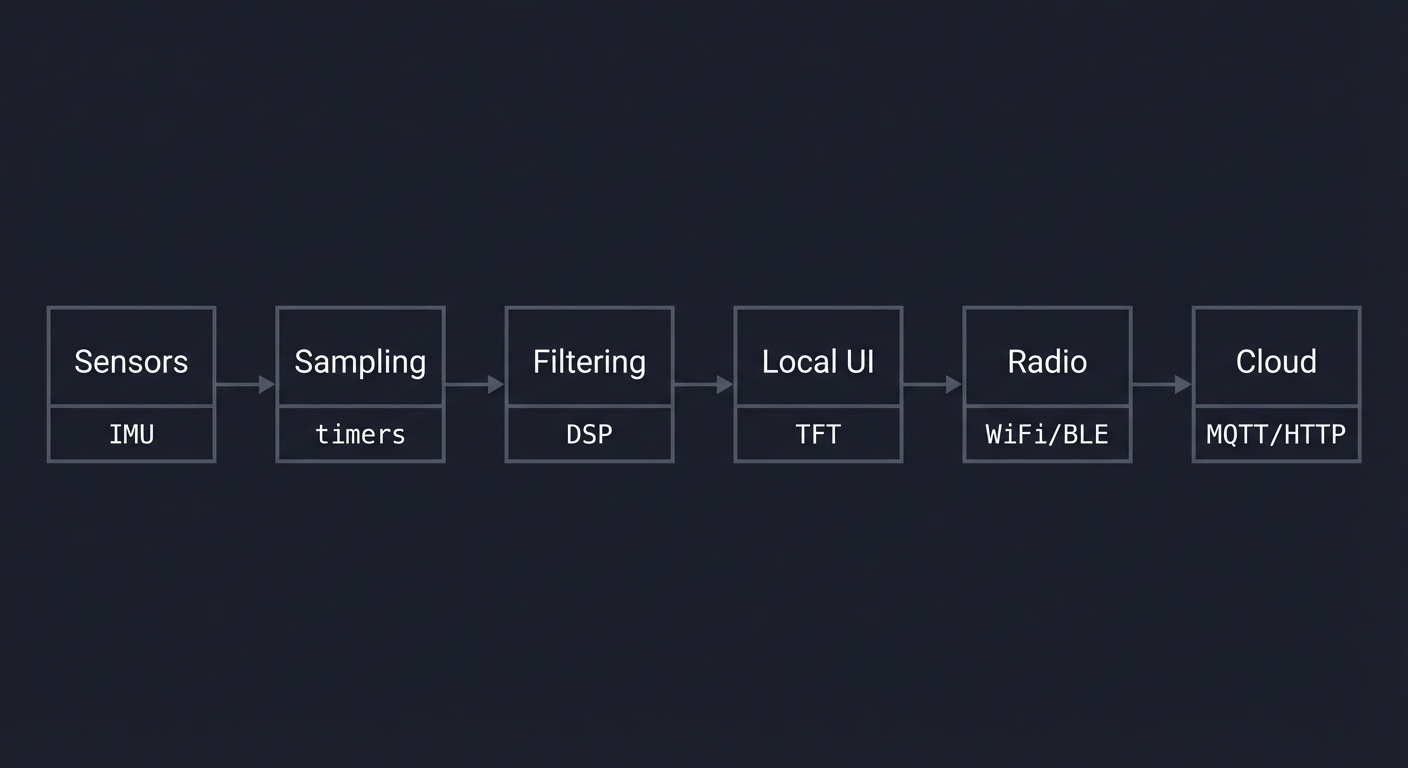

The Big Picture: From Sensor to Cloud

Every project you build is a variation of this pipeline:

Sensors ─► Sampling ─► Filtering ─► Local UI ─► Radio ─► Cloud

| | | | | |

IMU timers DSP TFT WiFi/BLE MQTT/HTTP

The StickC Plus2 is small, but the architecture is the same as modern wearables:

- Front end: sensors, buttons, IR, microphone

- Core: ESP32 dual-core + FreeRTOS

- Back end: WiFi/BLE + cloud endpoints

- Energy system: battery + sleep management

Once you understand this pipeline, you can design any IoT product.

Prerequisites & Background Knowledge

Essential Prerequisites (Must Have)

- Basic Arduino or C/C++ fundamentals (functions, loops, structs)

- Comfort with serial logs and flashing firmware

- Basic electronics: power, ground, pull-up resistors

Helpful But Not Required

- Familiarity with FreeRTOS tasks

- Simple networking concepts (IP, TCP/UDP)

- Basic signal processing (moving average, FFT)

Self-Assessment Questions

- Can you wire an I2C sensor correctly and scan its address?

- Can you debug a crash using serial logs?

- Can you read a datasheet table and extract pin requirements?

Development Environment Setup

- Arduino IDE or PlatformIO (recommended)

- M5StickC Plus2 board support package

- USB-C data cable

- Optional: logic analyzer for bus debugging

Time Investment

- Beginner path: 6–10 weeks

- Intermediate path: 4–6 weeks

- Advanced path: 3–5 weeks (if already familiar with ESP32)

How to Use This Guide

- Read the Core Question for each project and restate it.

- Implement minimal functionality first, then add polish.

- Validate with tests (sensor values, packet counts, frame rate).

- Measure power consumption at least once per project.

- Treat each project as a deployable product, not a throwaway demo.

Core Concept Analysis

Before building projects, you must internalize these foundational concepts.

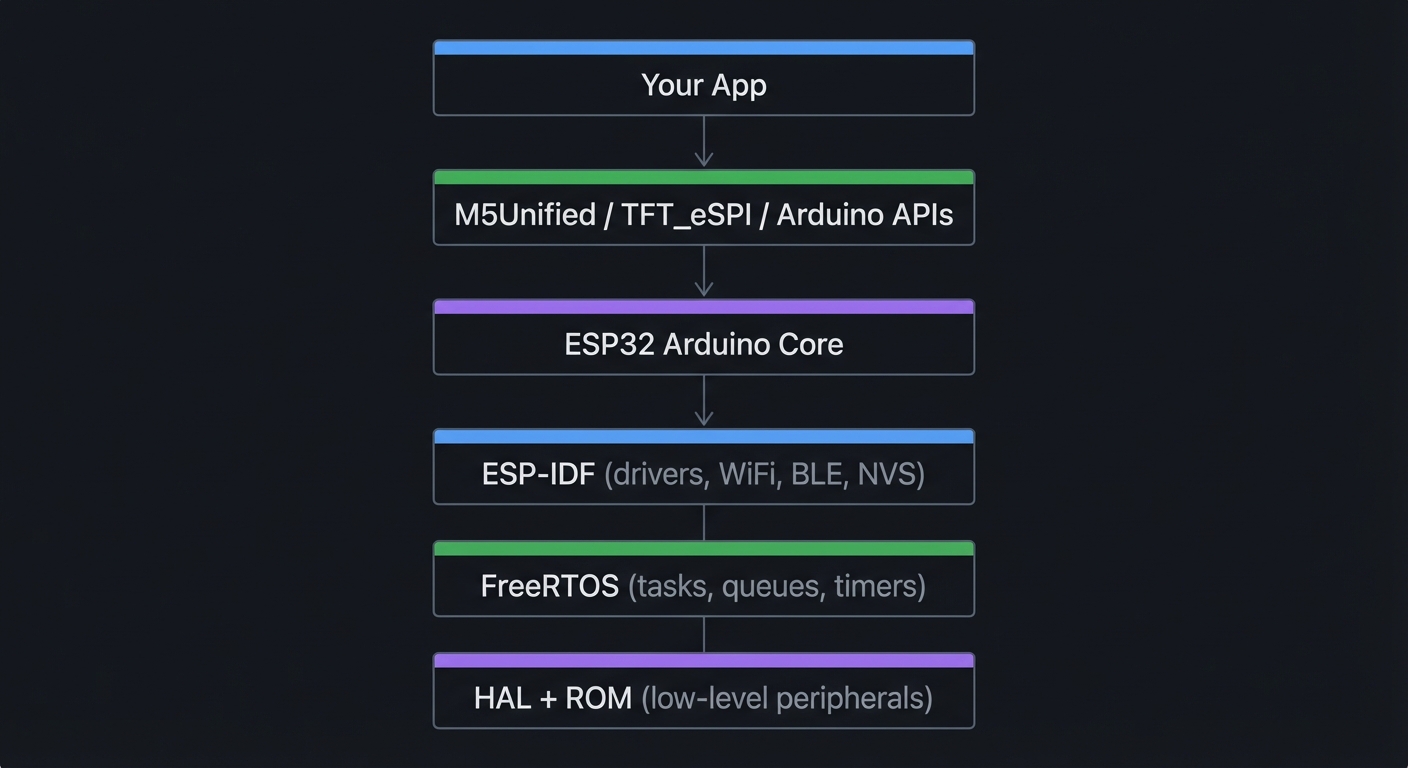

0. Firmware Stack and Tooling

The StickC Plus2 firmware stack layers hardware, RTOS, and libraries:

Your App

└─ M5Unified / TFT_eSPI / Arduino APIs

└─ ESP32 Arduino Core

└─ ESP-IDF (drivers, WiFi, BLE, NVS)

└─ FreeRTOS (tasks, queues, timers)

└─ HAL + ROM (low-level peripherals)

Key Insight: Bugs often hide across layers (e.g., a display glitch caused by SPI contention). Knowing the stack helps you debug faster.

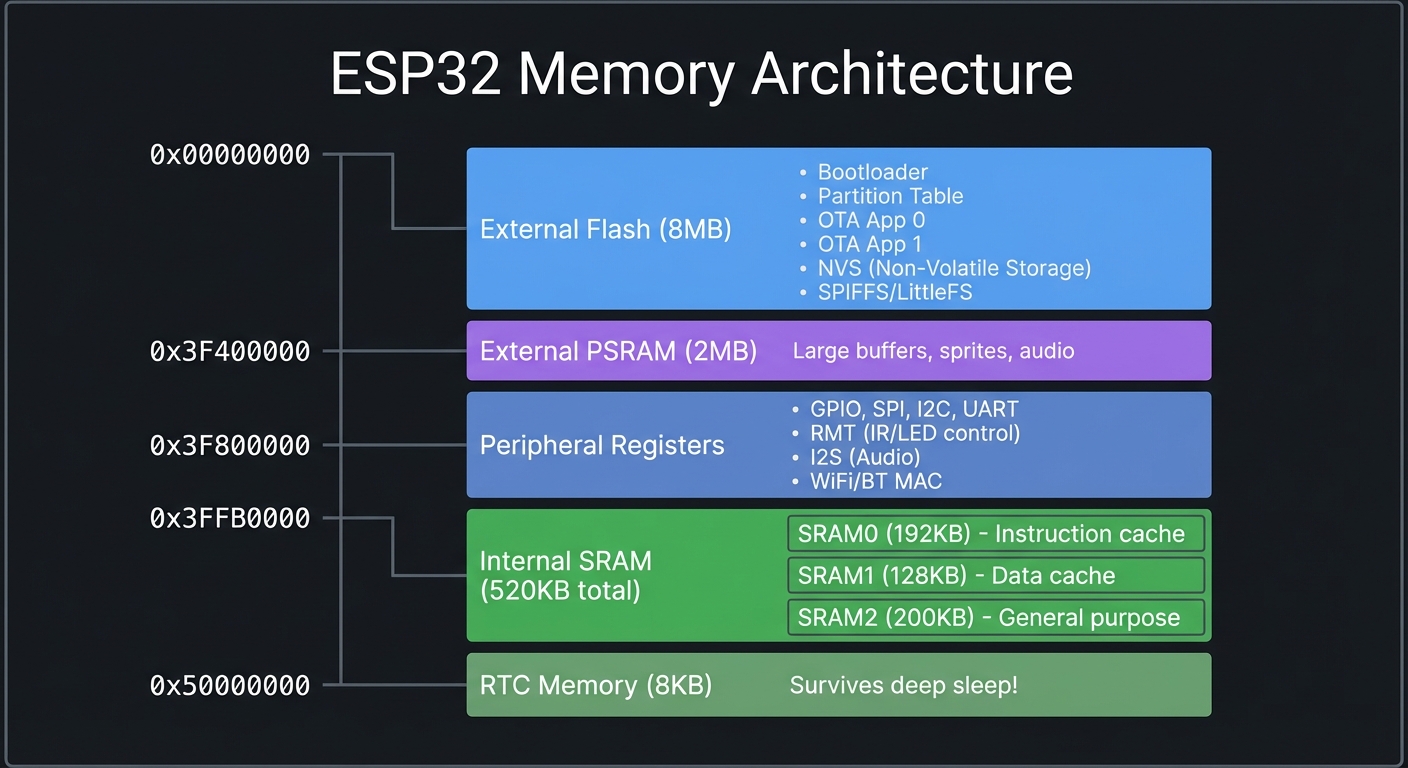

1. The ESP32 Architecture

The ESP32-PICO-V3-02 in the StickC Plus2 is a System-in-Package (SiP):

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ ESP32 Memory Architecture │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ Address Space (32-bit) │

│ ├── 0x00000000 ───────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │ │

│ ├── 0x3F400000 External Flash (8MB) │

│ │ ├── Bootloader │

│ │ ├── Partition Table │

│ │ ├── OTA App 0 │

│ │ ├── OTA App 1 │

│ │ ├── NVS (Non-Volatile Storage) │

│ │ └── SPIFFS/LittleFS │

│ │ │

│ ├── 0x3F800000 External PSRAM (2MB) │

│ │ └── Large buffers, sprites, audio │

│ │ │

│ ├── 0x3FF00000 Peripheral Registers │

│ │ ├── GPIO, SPI, I2C, UART │

│ │ ├── RMT (IR/LED control) │

│ │ ├── I2S (Audio) │

│ │ └── WiFi/BT MAC │

│ │ │

│ ├── 0x3FFB0000 Internal SRAM (520KB total) │

│ │ ├── SRAM0 (192KB) - Instruction cache │

│ │ ├── SRAM1 (128KB) - Data cache │

│ │ └── SRAM2 (200KB) - General purpose │

│ │ │

│ └── 0x50000000 RTC Memory (8KB) │

│ └── Survives deep sleep! │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Key Insight: The ESP32 has limited internal RAM (~320KB usable), but 2MB of PSRAM for large buffers. Graphics and audio will use PSRAM.

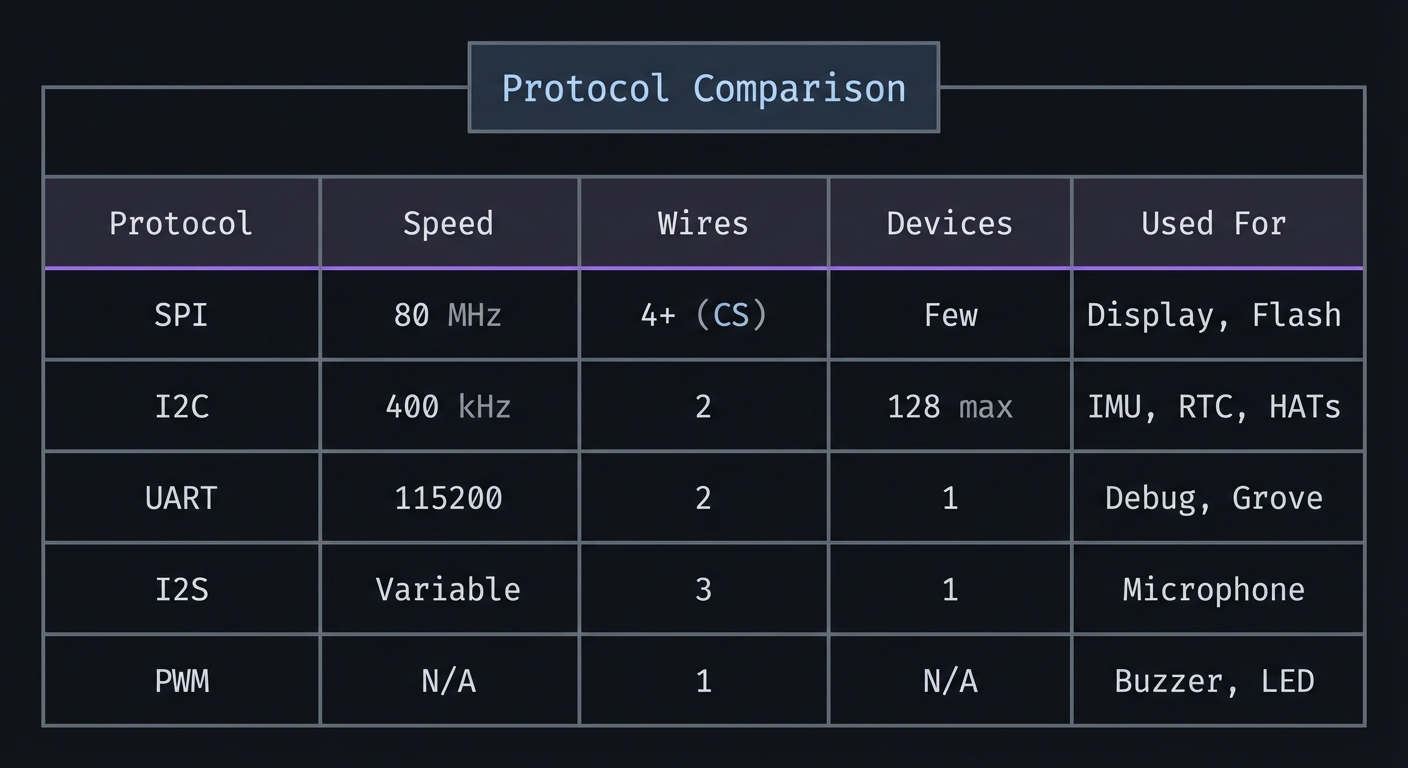

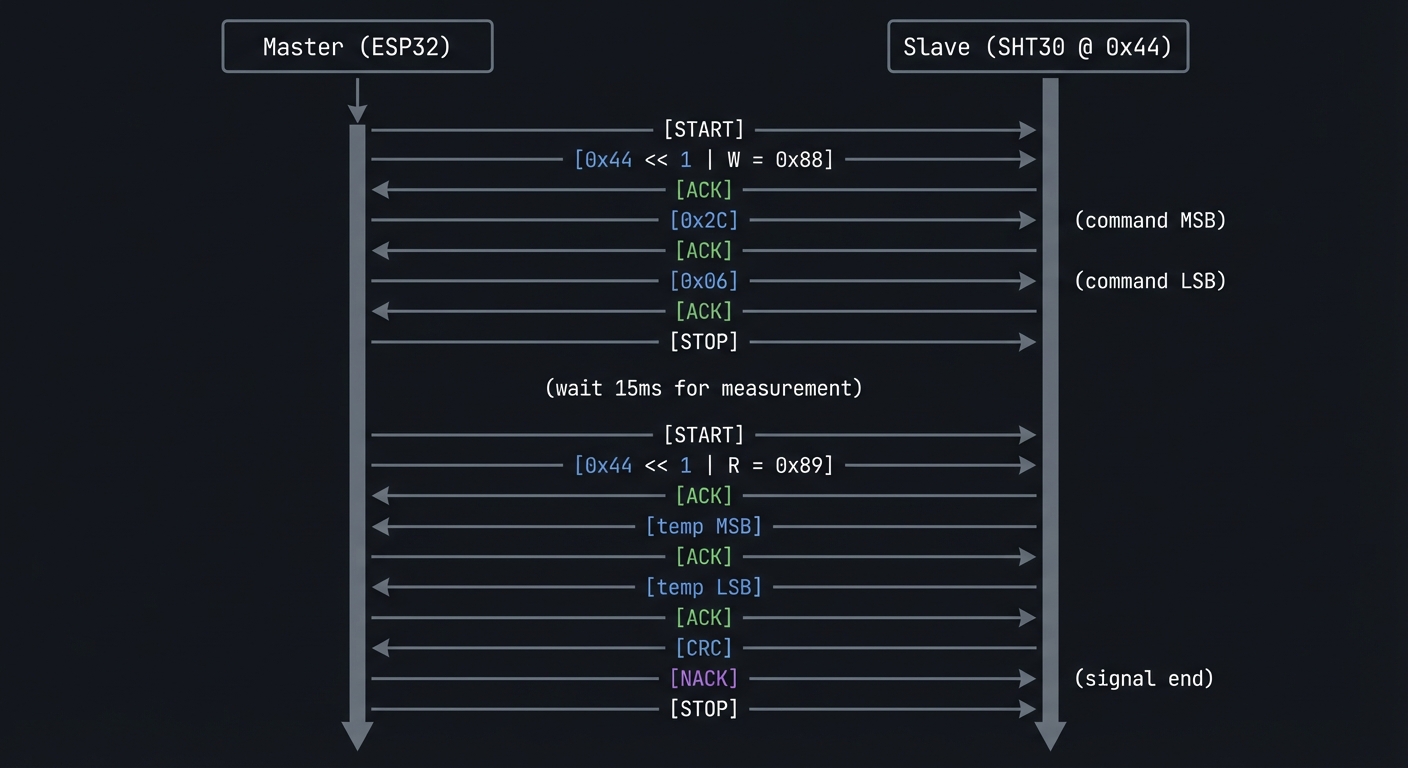

2. Communication Protocols

The StickC Plus2 uses multiple protocols to talk to its peripherals:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Protocol Comparison │

├──────────┬───────────┬───────────┬───────────┬──────────────────┤

│ Protocol │ Speed │ Wires │ Devices │ Used For │

├──────────┼───────────┼───────────┼───────────┼──────────────────┤

│ SPI │ 80 MHz │ 4+ (CS) │ Few │ Display, Flash │

│ I2C │ 400 kHz │ 2 │ 128 max │ IMU, RTC, HATs │

│ UART │ 115200 │ 2 │ 1 │ Debug, Grove │

│ I2S │ Variable │ 3 │ 1 │ Microphone │

│ PWM │ N/A │ 1 │ N/A │ Buzzer, LED │

└──────────┴───────────┴───────────┴───────────┴──────────────────┘

SPI (Display - ST7789V2):

┌───────┐ MOSI ┌─────────┐

│ │────────────►│ │

│ ESP32 │ SCLK │ ST7789 │

│ │────────────►│ Display │

│ │ CS │ │

│ │────────────►│ │

│ │ DC │ │

│ │────────────►│ │

└───────┘ └─────────┘

I2C (IMU, RTC - Shared Bus):

┌───────┐ SDA ┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐

│ │◄───────────►│ MPU6886 │ │ BM8563 │

│ ESP32 │ SCL │ (0x68) │ │ (0x51) │

│ │────────────►│ IMU │ │ RTC │

└───────┘ └────┬────┘ └────┬────┘

│ │

◄───┴───────────────┘ (Same bus, different addresses)

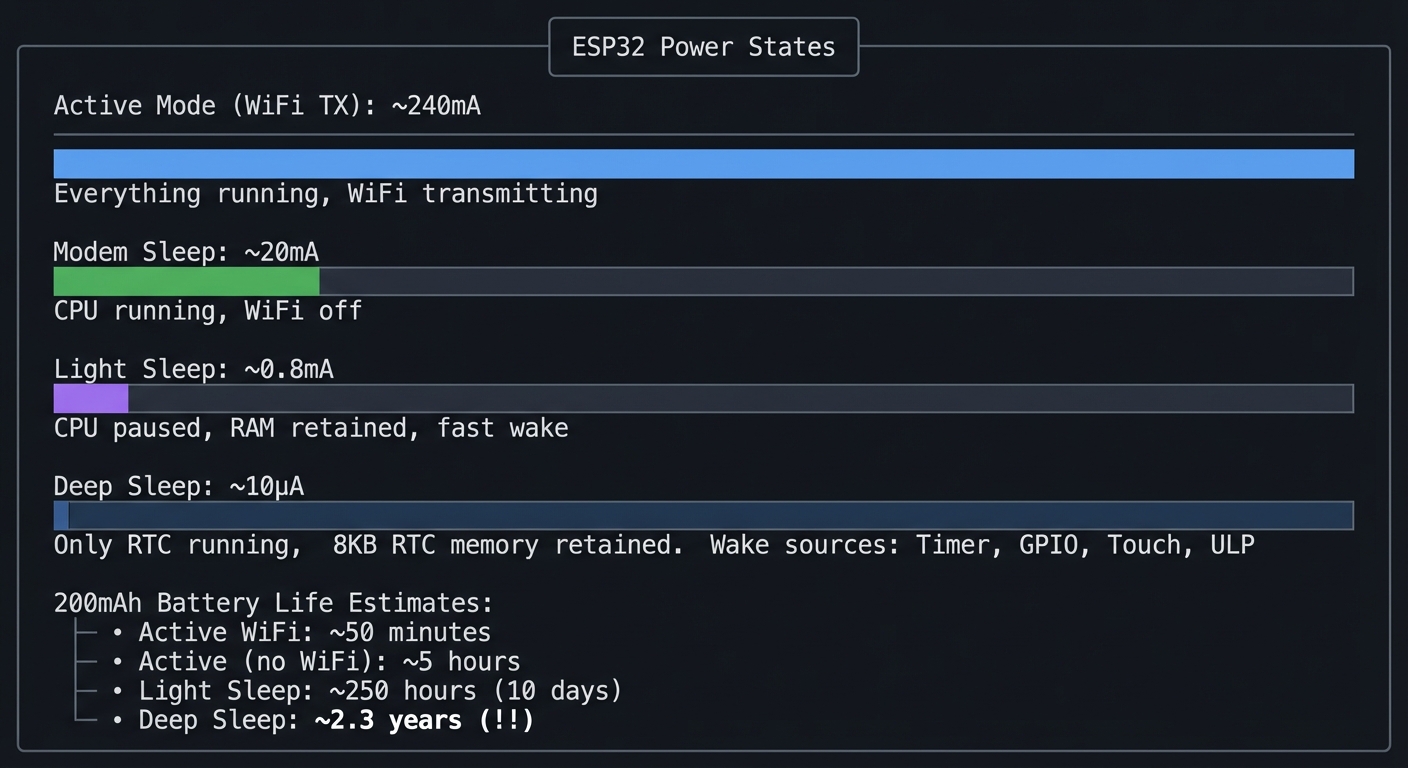

3. Power States and Deep Sleep

Battery life is critical for portable devices. The ESP32 has multiple power modes:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ ESP32 Power States │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ Active Mode (WiFi TX): ~240mA │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ ████████████████████████████████████████████████████████│ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ Everything running, WiFi transmitting │

│ │

│ Modem Sleep: ~20mA │

│ ┌───────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ ███████████████████████████████ │

│ └───────────────────────────────┘ │

│ CPU running, WiFi off │

│ │

│ Light Sleep: ~0.8mA │

│ ┌────────┐ │

│ │ ████████ │

│ └────────┘ │

│ CPU paused, RAM retained, fast wake │

│ │

│ Deep Sleep: ~10µA │

│ ┌──┐ │

│ │ ██ │

│ └──┘ │

│ Only RTC running, 8KB RTC memory retained │

│ Wake sources: Timer, GPIO, Touch, ULP │

│ │

│ 200mAh Battery Life Estimates: │

│ ├── Active WiFi: ~50 minutes │

│ ├── Active (no WiFi): ~5 hours │

│ ├── Light Sleep: ~250 hours (10 days) │

│ └── Deep Sleep: ~2.3 years (!!) │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Key Insight: Real IoT devices spend 99%+ of time in deep sleep, waking only to sample sensors and transmit data.

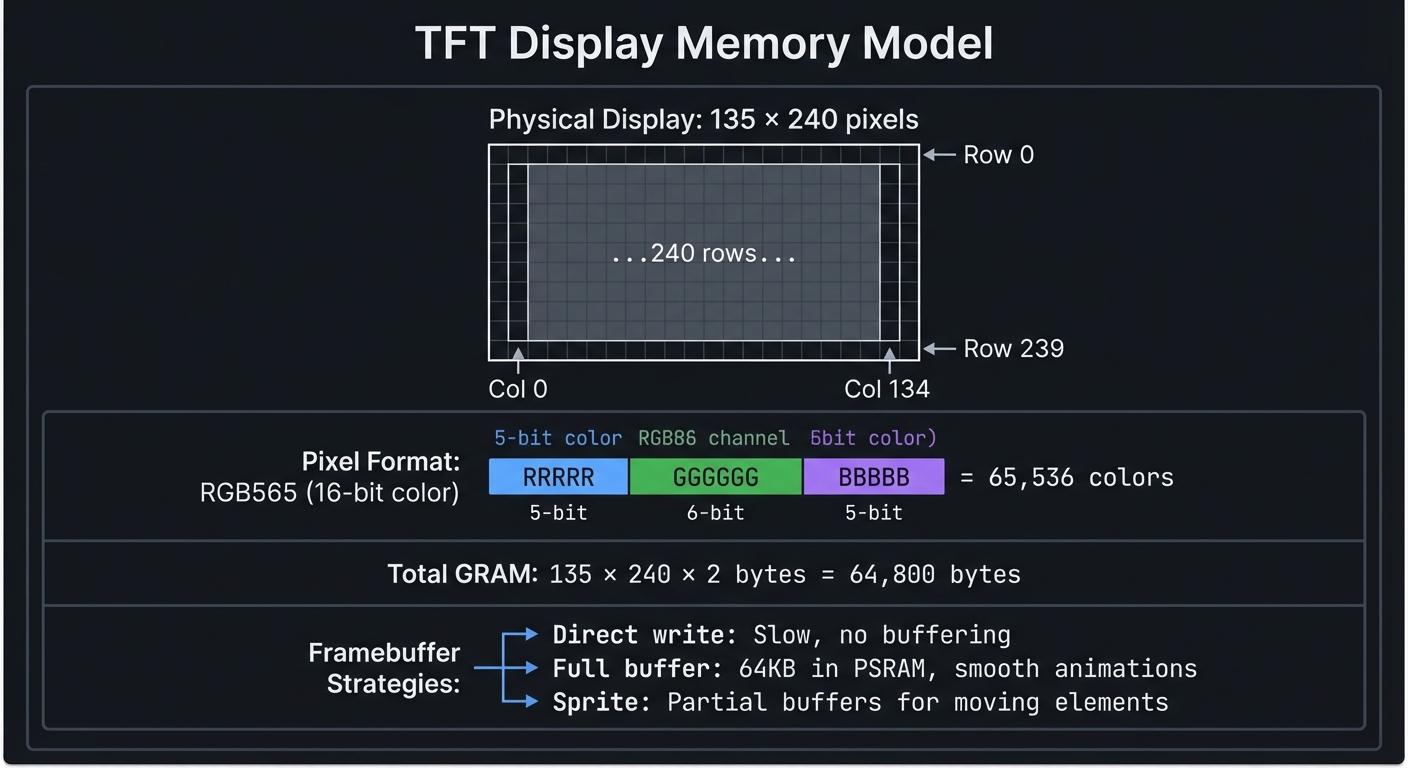

4. Display and Graphics

The ST7789V2 is a color TFT driven over SPI:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ TFT Display Memory Model │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ Physical Display: 135 × 240 pixels │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░│ ← Row 0 │

│ │░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░│ │

│ │░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░│ │

│ │ ...240 rows... │ │

│ │░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░│ ← Row 239 │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ ▲ ▲ │

│ │ │ │

│ Col 0 Col 134 │

│ │

│ Pixel Format: RGB565 (16-bit color) │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ RRRRR │ GGGGGG │ BBBBB │ = 65,536 colors │ │

│ │ 5-bit │ 6-bit │ 5-bit │ │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ Total GRAM: 135 × 240 × 2 bytes = 64,800 bytes │

│ │

│ Framebuffer Strategies: │

│ ├── Direct write: Slow, no buffering │

│ ├── Full buffer: 64KB in PSRAM, smooth animations │

│ └── Sprite: Partial buffers for moving elements │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

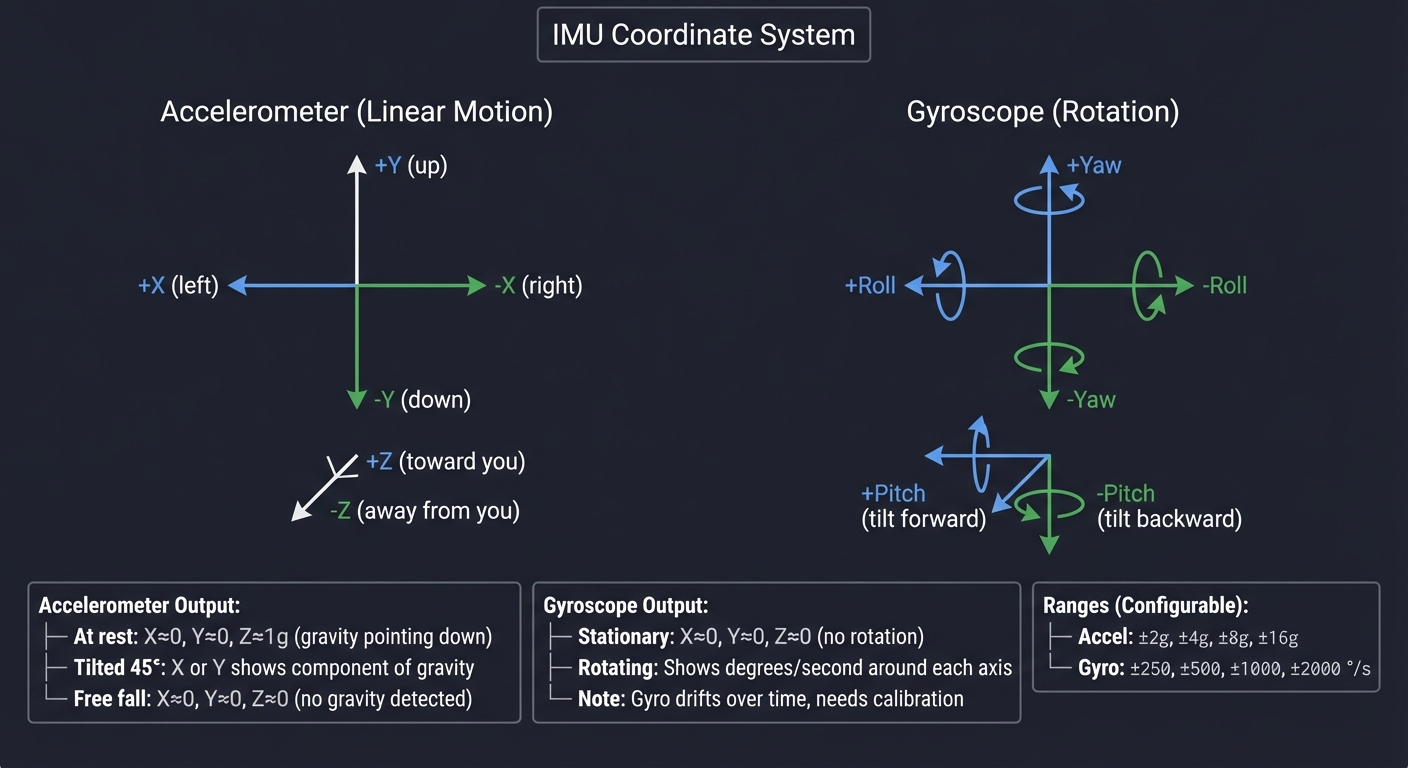

5. The IMU (Inertial Measurement Unit)

The MPU6886 provides 6 degrees of freedom:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ IMU Coordinate System │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ Accelerometer Gyroscope │

│ (Linear Motion) (Rotation) │

│ │

│ +Y (up) +Yaw │

│ ▲ ⟳ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ │ │

│ +X ◄───────┼─────────► -X +Roll ◄────┼────► -Roll │

│ (left) │ (right) │ │

│ │ │ │

│ ▼ ▼ │

│ -Y (down) -Yaw │

│ │

│ +Z (toward you) +Pitch (tilt forward) │

│ -Z (away from you) -Pitch (tilt backward) │

│ │

│ Accelerometer Output: │

│ ├── At rest: X≈0, Y≈0, Z≈1g (gravity pointing down) │

│ ├── Tilted 45°: X or Y shows component of gravity │

│ └── Free fall: X≈0, Y≈0, Z≈0 (no gravity detected) │

│ │

│ Gyroscope Output: │

│ ├── Stationary: X≈0, Y≈0, Z≈0 (no rotation) │

│ ├── Rotating: Shows degrees/second around each axis │

│ └── Note: Gyro drifts over time, needs calibration │

│ │

│ Ranges (Configurable): │

│ ├── Accel: ±2g, ±4g, ±8g, ±16g │

│ └── Gyro: ±250, ±500, ±1000, ±2000 °/s │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

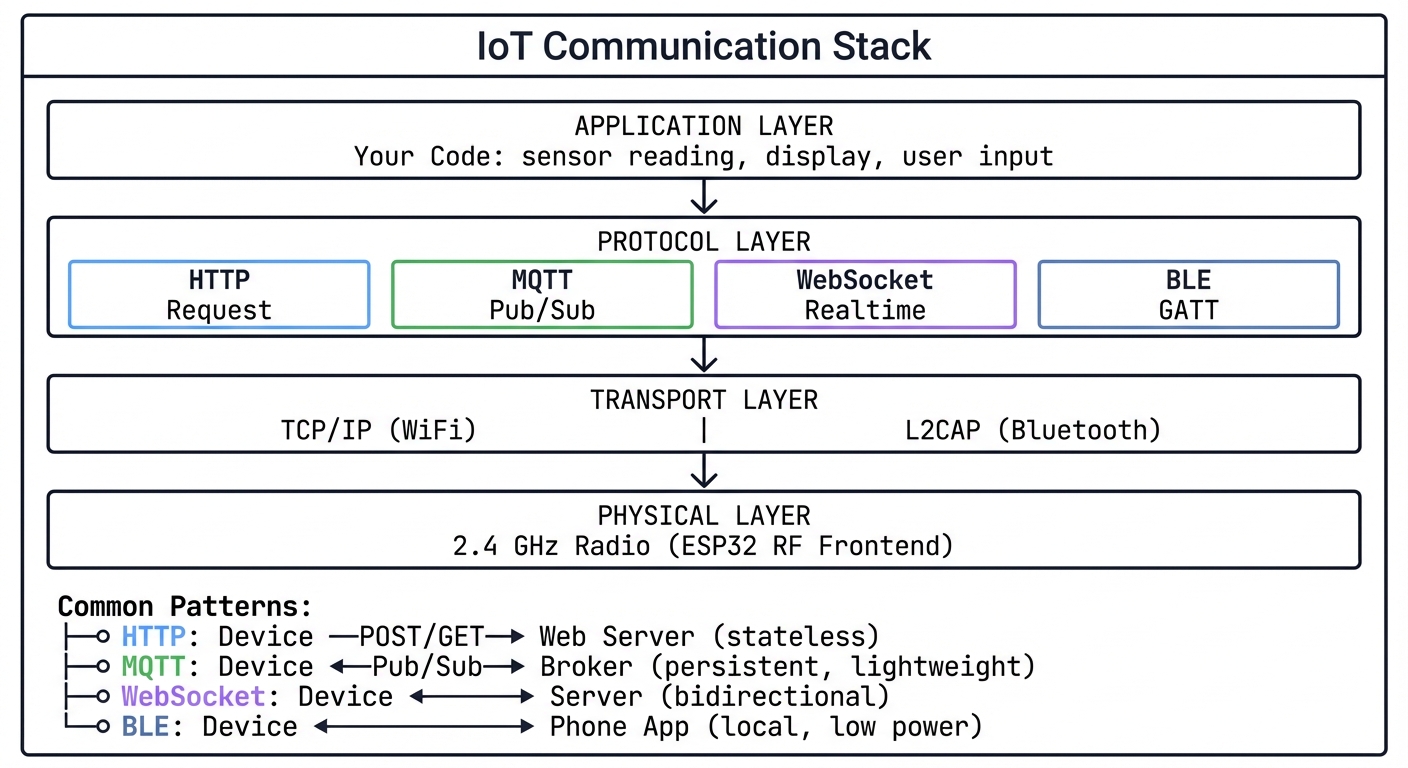

6. Wireless Communication Stack

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ IoT Communication Stack │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ APPLICATION LAYER │ │

│ │ Your Code: sensor reading, display, user input │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ PROTOCOL LAYER │ │

│ │ ┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ HTTP │ │ MQTT │ │ WebSocket│ │ BLE │ │ │

│ │ │ Request │ │Pub/Sub │ │Realtime │ │ GATT │ │ │

│ │ └─────────┘ └─────────┘ └─────────┘ └─────────┘ │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ TRANSPORT LAYER │ │

│ │ TCP/IP (WiFi) │ L2CAP (Bluetooth) │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ PHYSICAL LAYER │ │

│ │ 2.4 GHz Radio (ESP32 RF Frontend) │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ Common Patterns: │

│ ├── HTTP: Device ──POST/GET──► Web Server (stateless) │

│ ├── MQTT: Device ◄──Pub/Sub──► Broker (persistent, lightweight)│

│ ├── WebSocket: Device ◄──────► Server (bidirectional) │

│ └── BLE: Device ◄──────────► Phone App (local, low power) │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

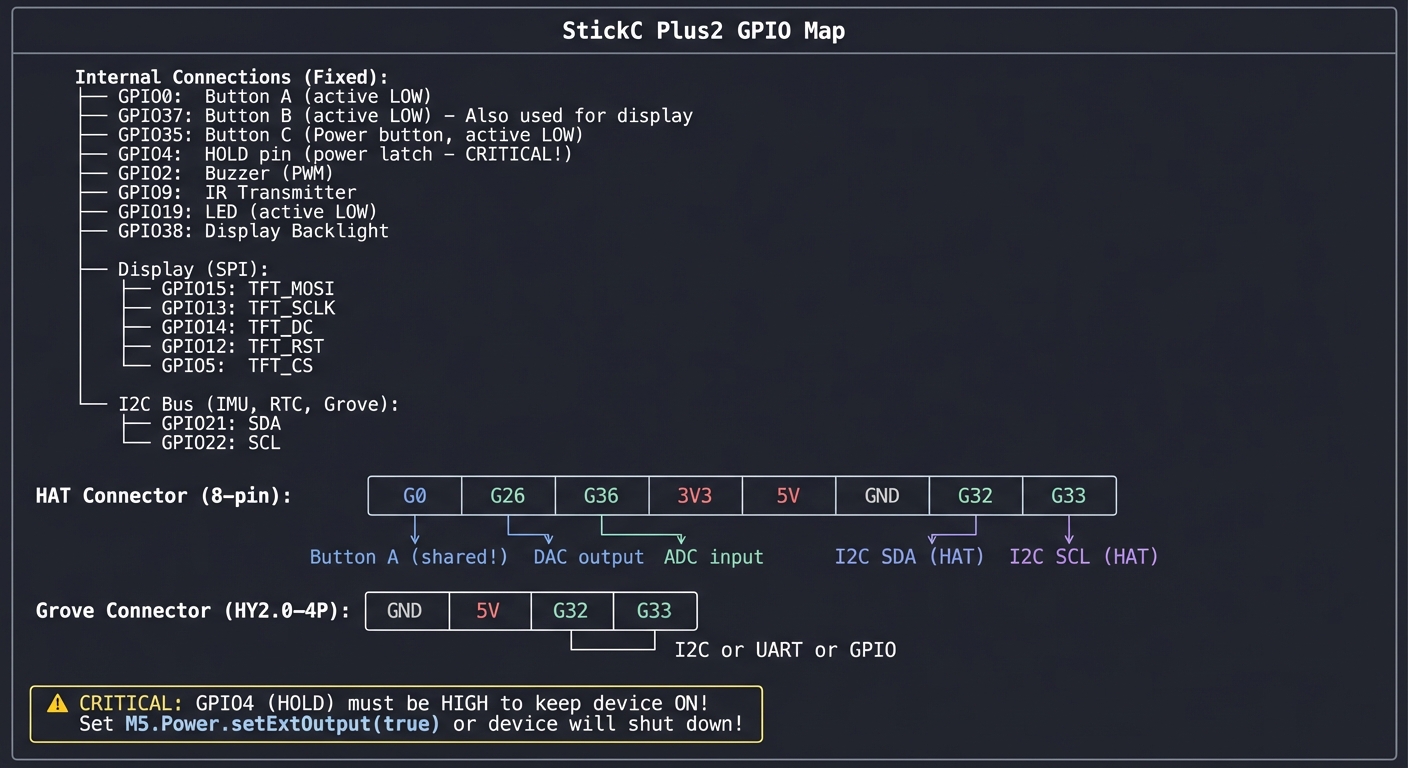

7. GPIO and Pin Functions

The StickC Plus2 exposes limited but versatile pins:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ StickC Plus2 GPIO Map │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ Internal Connections (Fixed): │

│ ├── GPIO0: Button A (active LOW) │

│ ├── GPIO37: Button B (active LOW) - Also used for display │

│ ├── GPIO35: Button C (Power button, active LOW) │

│ ├── GPIO4: HOLD pin (power latch - CRITICAL!) │

│ ├── GPIO2: Buzzer (PWM) │

│ ├── GPIO9: IR Transmitter │

│ ├── GPIO19: LED (active LOW) │

│ ├── GPIO38: Display Backlight │

│ │ │

│ │ Display (SPI): │

│ ├── GPIO15: TFT_MOSI │

│ ├── GPIO13: TFT_SCLK │

│ ├── GPIO14: TFT_DC │

│ ├── GPIO12: TFT_RST │

│ ├── GPIO5: TFT_CS │

│ │ │

│ │ I2C Bus (IMU, RTC, Grove): │

│ ├── GPIO21: SDA │

│ └── GPIO22: SCL │

│ │

│ HAT Connector (8-pin): │

│ ┌────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬────┐ │

│ │ G0 │G26 │G36 │3V3 │5V │GND │G32 │G33 │ │

│ └────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴────┘ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ │ └── ADC input │ └── I2C SCL (HAT) │

│ │ └── DAC output └── I2C SDA (HAT) │

│ └── Button A (shared!) │

│ │

│ Grove Connector (HY2.0-4P): │

│ ┌────┬────┬────┬────┐ │

│ │GND │5V │G32 │G33 │ │

│ └────┴────┴────┴────┘ │

│ │ │ │

│ └────┴── I2C or UART or GPIO │

│ │

│ ⚠️ CRITICAL: GPIO4 (HOLD) must be HIGH to keep device ON! │

│ Set M5.Power.setExtOutput(true) or device will shut down! │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

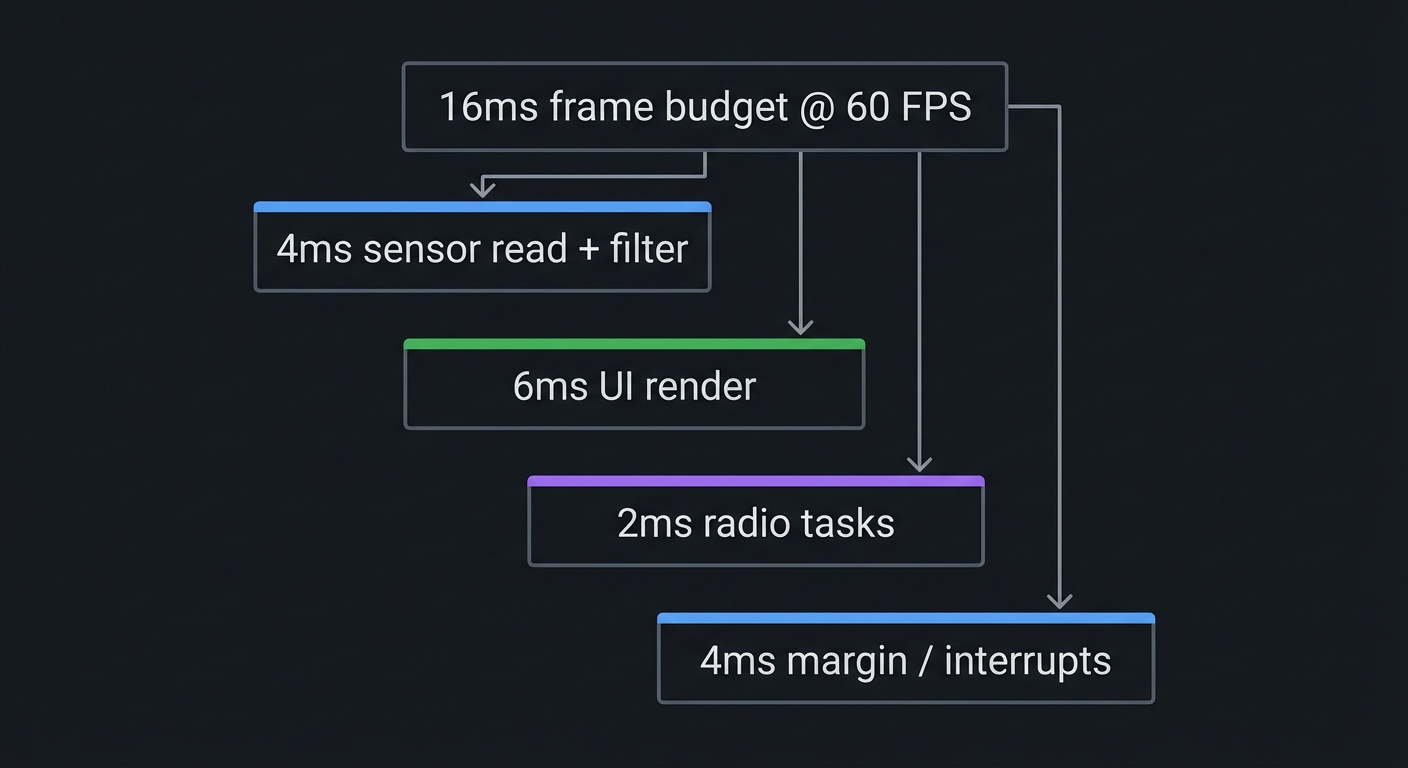

8. Real-Time Tasking and Timing Budget

Tiny devices still have a timing budget. If your render loop is too slow, sensors lag; if WiFi blocks, UI freezes.

16ms frame budget @ 60 FPS

├── 4ms sensor read + filter

├── 6ms UI render

├── 2ms radio tasks

└── 4ms margin / interrupts

Key Insight: Use non-blocking operations and short critical sections. Long WiFi calls should run in a separate task.

Concept Summary Table

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize |

|---|---|

| ESP32 Architecture | Dual-core processor with limited RAM (~320KB), 8MB flash for code/data, 2MB PSRAM for buffers. Memory-mapped peripherals. |

| Communication Protocols | SPI for high-speed (display), I2C for sensors (shared bus, addresses), UART for serial, I2S for audio. Each has timing/wiring requirements. |

| Power Management | Deep sleep draws 10µA vs 240mA active. Battery life depends on duty cycle. RTC memory survives sleep. Wake sources: timer, GPIO, touch. |

| Display Graphics | RGB565 format (16-bit color), framebuffers eliminate flicker, sprites for animation. PSRAM holds large buffers. |

| IMU Physics | Accelerometer measures linear motion + gravity. Gyroscope measures rotation. Sensor fusion combines both for orientation. Drift requires calibration. |

| Wireless Protocols | WiFi for internet (high power), BLE for local (low power). MQTT for IoT pub/sub, HTTP for request/response, BLE GATT for services/characteristics. |

| GPIO & Peripherals | Limited exposed pins. Internal connections fixed. HOLD pin (GPIO4) critical for power. Button states are active-LOW. |

| Firmware Stack | Arduino runs on ESP-IDF/FreeRTOS. Driver conflicts and blocking calls are common bugs. |

| Real-Time Timing | UI + sensor + radio must fit within frame budget. Use tasks and non-blocking APIs. |

Success Metrics (What “Mastery” Looks Like)

You can consider this track successful when you can:

- Explain how each peripheral communicates and debug it with logs or bus scans.

- Build a UI that stays responsive while networking in the background.

- Deploy OTA updates safely without bricking the device.

- Measure and optimize power consumption for a real battery target.

- Integrate at least one external HAT/Grove module from scratch.

Deep Dive Reading by Concept

This section maps each concept from above to specific book chapters for deeper understanding.

Embedded Systems Fundamentals

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Microcontroller Architecture | Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Edition by Elecia White — Ch. 2: “Creating a System Architecture” |

| Memory-Mapped I/O | Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective by Bryant & O’Hallaron — Ch. 6: “The Memory Hierarchy” |

| Interrupt Handling | Making Embedded Systems by Elecia White — Ch. 5: “Interrupts” |

| RTOS Scheduling | Making Embedded Systems by Elecia White — Ch. 6: “Scheduling” |

| Power Optimization | Making Embedded Systems by Elecia White — Ch. 10: “Reducing Power Consumption” |

Communication Protocols

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| SPI Protocol | The Book of I2C by Randall Hyde — Ch. 2: “SPI vs I2C Comparison” |

| I2C Protocol | The Book of I2C by Randall Hyde — Ch. 3-5: “I2C Fundamentals” |

| UART/Serial | Making Embedded Systems by Elecia White — Ch. 8: “Serial Drivers” |

Wireless & Networking

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| TCP/IP Fundamentals | Computer Networks, 5th Edition by Tanenbaum — Ch. 5-6: “Transport Layer” |

| MQTT Protocol | Designing Data-Intensive Applications by Kleppmann — Ch. 4: “Encoding and Evolution” (messaging patterns) |

| Bluetooth Low Energy | Getting Started with Bluetooth Low Energy by Townsend (O’Reilly) — All chapters |

Power & Hardware

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Low-Power Design | Making Embedded Systems by Elecia White — Ch. 10: “Reducing Power Consumption” |

| Battery Management | AVR Workshop by John Boxall — Ch. 8: “Power Management” |

| Sensor Interfacing | Arduino Workshop, 2nd Edition by John Boxall — Ch. 9-12: “Sensors” |

Essential Reading Order

For maximum comprehension, read in this order:

- Foundation (Week 1-2):

- Making Embedded Systems Ch. 1-2 (architecture)

- Arduino Workshop Ch. 1-4 (getting started)

- Communication (Week 3):

- The Book of I2C Ch. 1-5 (protocols)

- Making Embedded Systems Ch. 8 (serial drivers)

- Advanced Topics (Week 4+):

- Making Embedded Systems Ch. 10 (power)

- Computer Networks Ch. 5 (TCP/IP for WiFi understanding)

Project List

The following 12 projects take you from beginner to advanced, covering all major capabilities of the M5Stack StickC Plus2.

Project 1: Digital Instrument Cluster (Display & Graphics Mastery)

- File: LEARN_M5STACK_STICKC_PLUS2_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: C++ (Arduino)

- Alternative Programming Languages: MicroPython, Rust (esp-rs)

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 2. The “Micro-SaaS / Pro Tool”

- Difficulty: Level 1: Beginner

- Knowledge Area: Embedded Graphics, SPI Protocol, Framebuffers

- Software or Tool: TFT_eSPI library, ST7789 display driver

- Main Book: “Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Edition” by Elecia White

What you’ll build: A real-time dashboard showing animated gauges, text, and graphics—demonstrating framebuffer techniques that eliminate flicker and enable smooth animations on the 135×240 TFT display.

Why it teaches display programming: Before you can build any visual IoT project, you must master the display. This project forces you to understand RGB565 color encoding, SPI communication timing, sprite-based rendering, and how to achieve smooth animation with limited memory.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Understanding the ST7789 command set → maps to how display controllers work

- Eliminating screen flicker → maps to framebuffer and double-buffering concepts

- Managing memory for sprites → maps to PSRAM allocation and memory constraints

- Achieving smooth animation → maps to refresh rates and drawing optimization

Key Concepts:

- SPI Communication: Making Embedded Systems Ch. 8 - Elecia White

- Framebuffer Rendering: TFT_eSPI library documentation - Bodmer

- Color Encoding (RGB565): Computer Graphics from Scratch Ch. 2 - Gabriel Gambetta

- Memory Management: ESP32 Technical Reference Manual - Espressif

Difficulty: Beginner Time estimate: Weekend Prerequisites: Basic Arduino knowledge (setup/loop), understanding of functions and variables, ability to install libraries in Arduino IDE

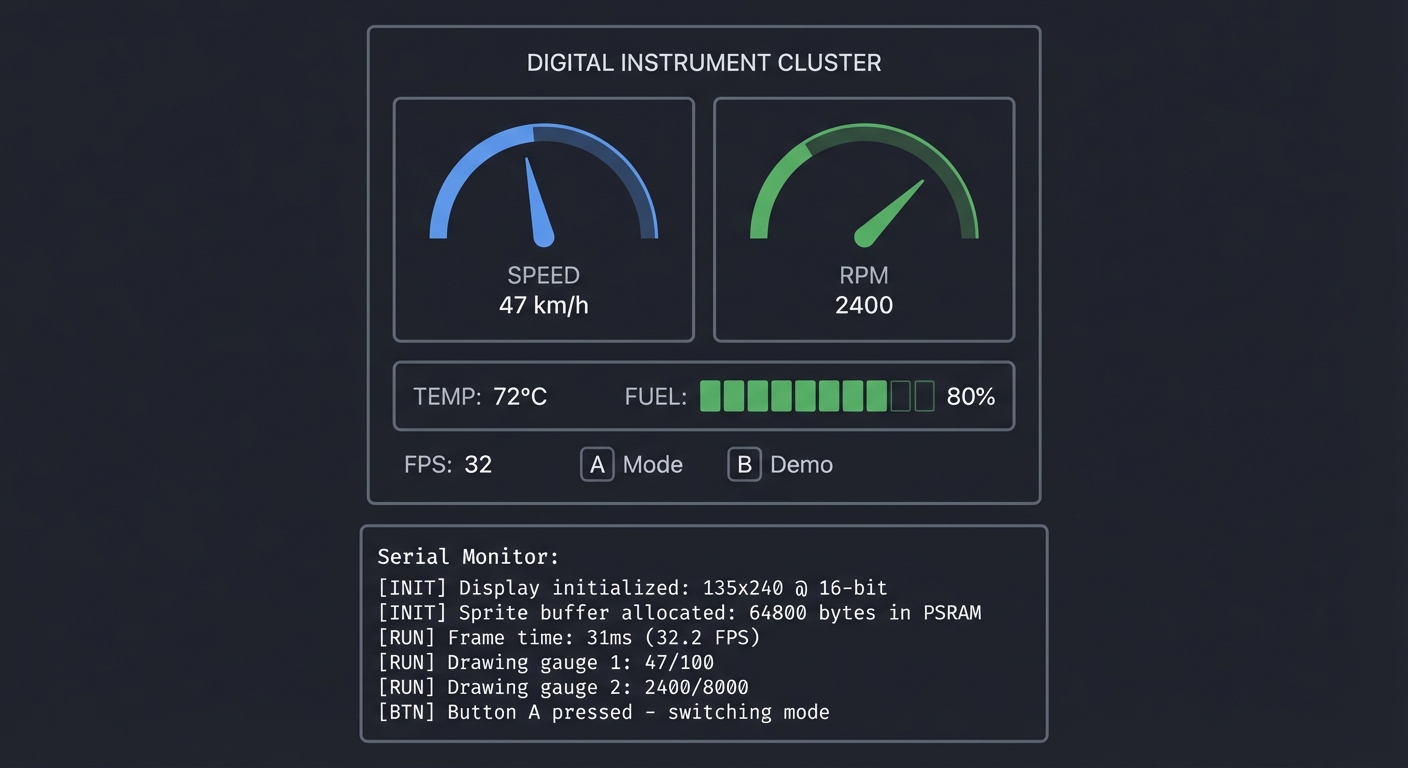

Real World Outcome

You’ll have a mini instrument panel that displays multiple animated gauges, updating in real-time with no visible flicker. When you run it:

- The display shows two analog-style gauges (speedometer and tachometer style)

- Needle positions animate smoothly as values change

- A digital readout shows precise values

- Frame rate counter proves you’re hitting 30+ FPS

Example Output:

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ DIGITAL INSTRUMENT CLUSTER │

├──────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────┐ │

│ │ ◠◠◠ │ │ ◠◠◠ │ │

│ │ ╱ ╲ │ │ ╱ ╲ │ │

│ │ │ ╲ │ │ │ │ ╱ │ │ │

│ │ ╲ ▼ ╱ │ │ ╲ ▼ ╱ │ │

│ │ ◡◡◡ │ │ ◡◡◡ │ │

│ │ SPEED │ │ RPM │ │

│ │ 47 km/h │ │ 2400 │ │

│ └─────────────┘ └─────────────┘ │

│ │

│ TEMP: 72°C FUEL: ████████░░ 80% │

│ │

│ FPS: 32 [A] Mode [B] Demo │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Serial Monitor:

[INIT] Display initialized: 135x240 @ 16-bit

[INIT] Sprite buffer allocated: 64800 bytes in PSRAM

[RUN] Frame time: 31ms (32.2 FPS)

[RUN] Drawing gauge 1: 47/100

[RUN] Drawing gauge 2: 2400/8000

[BTN] Button A pressed - switching mode

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do professional embedded devices display smooth, flicker-free animations on tiny screens with limited memory?”

Before you write any code, sit with this question. The StickC Plus2 has only ~320KB of usable RAM, but the display needs 64KB just for one frame. How do commercial products like smartwatches achieve buttery-smooth graphics? The answer lies in understanding framebuffers, sprites, and the art of drawing only what changes.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- SPI (Serial Peripheral Interface)

- What are the four main SPI signals (MOSI, MISO, SCLK, CS)?

- Why does SPI use a clock signal when UART doesn’t?

- What determines SPI transfer speed?

- Book Reference: “The Book of I2C” Ch. 2 - Randall Hyde

- Framebuffers and Double Buffering

- What is a framebuffer and where does it live in memory?

- Why does drawing directly to the screen cause flicker?

- How does double-buffering solve this?

- Book Reference: “Computer Graphics from Scratch” Ch. 1 - Gabriel Gambetta

- RGB Color Models

- Why does RGB565 use 5-6-5 bits instead of 8-8-8?

- How do you convert RGB888 to RGB565?

- What colors are lost in this conversion?

- Book Reference: “Computer Graphics from Scratch” Ch. 2 - Gabriel Gambetta

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Memory Budget

- How many bytes does one full-screen framebuffer require?

- Will this fit in internal RAM or must you use PSRAM?

- Can you use a smaller sprite for just the moving parts?

- Drawing Strategy

- Should you redraw the entire screen every frame?

- Can you draw static elements once and only update moving parts?

- How will you handle overlapping elements?

- Animation Approach

- How will you calculate needle position from a value?

- What trigonometry do you need for circular gauges?

- How will you smooth motion to avoid jerky updates?

Thinking Exercise

Trace the Pixel Path

Before coding, trace how a single pixel gets from your code to the display:

sprite.drawPixel(67, 120, TFT_RED); // Center of 135-wide screen

sprite.pushSprite(0, 0); // Send to display

Questions while tracing:

- Where is the pixel value (TFT_RED = 0xF800) stored before pushSprite?

- How many bytes are transferred over SPI when pushSprite runs?

- What commands does the ESP32 send to tell the display WHERE to put these bytes?

- At 80MHz SPI clock, how long does transferring one full frame take?

Calculate: 135 × 240 × 2 bytes = 64,800 bytes. At 80 MHz, with 8 bits per clock: 64,800 × 8 ÷ 80,000,000 = ~6.5ms per frame. You could theoretically hit 150 FPS just from transfer time!

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “Explain the difference between SPI and I2C. When would you use each?”

- “What is double buffering and why is it important for graphics?”

- “How does the ESP32 manage memory between internal RAM and PSRAM?”

- “Describe RGB565 color format. Why is it used in embedded displays?”

- “How would you optimize drawing performance on a memory-constrained device?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Getting Started Install the M5StickCPlus2 library through Arduino IDE Library Manager. The library includes display drivers. Start with the “Display” example.

Hint 2: Creating Sprites Look at TFT_eSPI’s sprite examples. A sprite is just an off-screen canvas. Create one the size of your gauge, draw there, then push to screen.

Hint 3: Drawing Gauge Needles For a needle pointing at angle θ from center (cx, cy) with length r:

- endpoint_x = cx + r * cos(θ)

- endpoint_y = cy + r * sin(θ) Convert your 0-100 value to radians: θ = map(value, 0, 100, -135°, 135°) × π/180

Hint 4: Optimizing Refresh

Use sprite.createSprite(width, height) in PSRAM. Draw background once to a static sprite. Each frame: copy background to working sprite, draw needles, push to display.

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem: “Screen flickers during animation”

- Why: Full-screen redraw without buffering

- Fix: Use sprites or partial buffers in PSRAM and only blit changed regions

- Quick test: Track FPS before and after buffering

Problem: “Graphics corruption after a few seconds”

- Why: Buffer overflow or PSRAM not enabled

- Fix: Ensure PSRAM enabled and buffers sized for 135x240 RGB565

- Quick test: Allocate a 64KB buffer and render a solid color

Definition of Done

- UI renders at 30+ FPS without flicker

- Uses sprites or partial buffers in PSRAM

- SPI display init is reliable across reboots

- Frame time logged and stays under budget

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Display drivers | “Making Embedded Systems” by Elecia White | Ch. 8 |

| Graphics fundamentals | “Computer Graphics from Scratch” by Gambetta | Ch. 1-2 |

| SPI protocol | “The Book of I2C” by Randall Hyde | Ch. 2 |

| ESP32 memory | ESP32 Technical Reference Manual | Ch. 4 |

Implementation Hints

The key insight for this project is understanding the sprite workflow:

- Create sprites in setup(): Allocate memory once for your drawing canvases

- Draw static elements once: Background, gauge faces, labels

- In loop(), only redraw what changes: Clear sprite, copy background, draw needles, push

The TFT_eSPI library provides the TFT_eSprite class. Study how createSprite(), fillSprite(), drawLine(), and pushSprite() work together.

For smooth needle motion, don’t jump instantly to new values. Implement easing:

current = current + (target - current) * 0.1; // Smooth approach

Learning milestones:

- Display shows static text and shapes → You understand basic TFT commands

- Sprite-based drawing eliminates flicker → You understand buffering

- Gauges animate smoothly at 30+ FPS → You’ve mastered the graphics pipeline

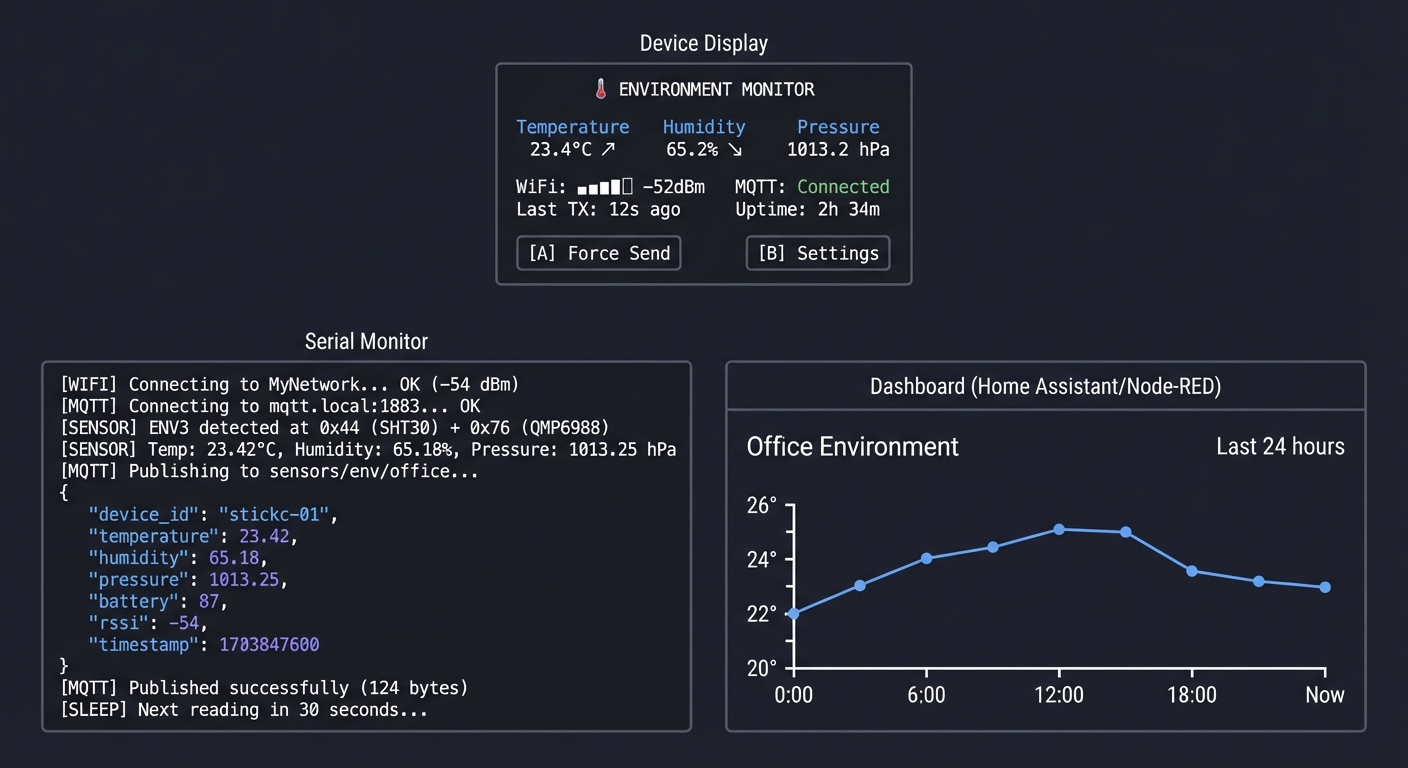

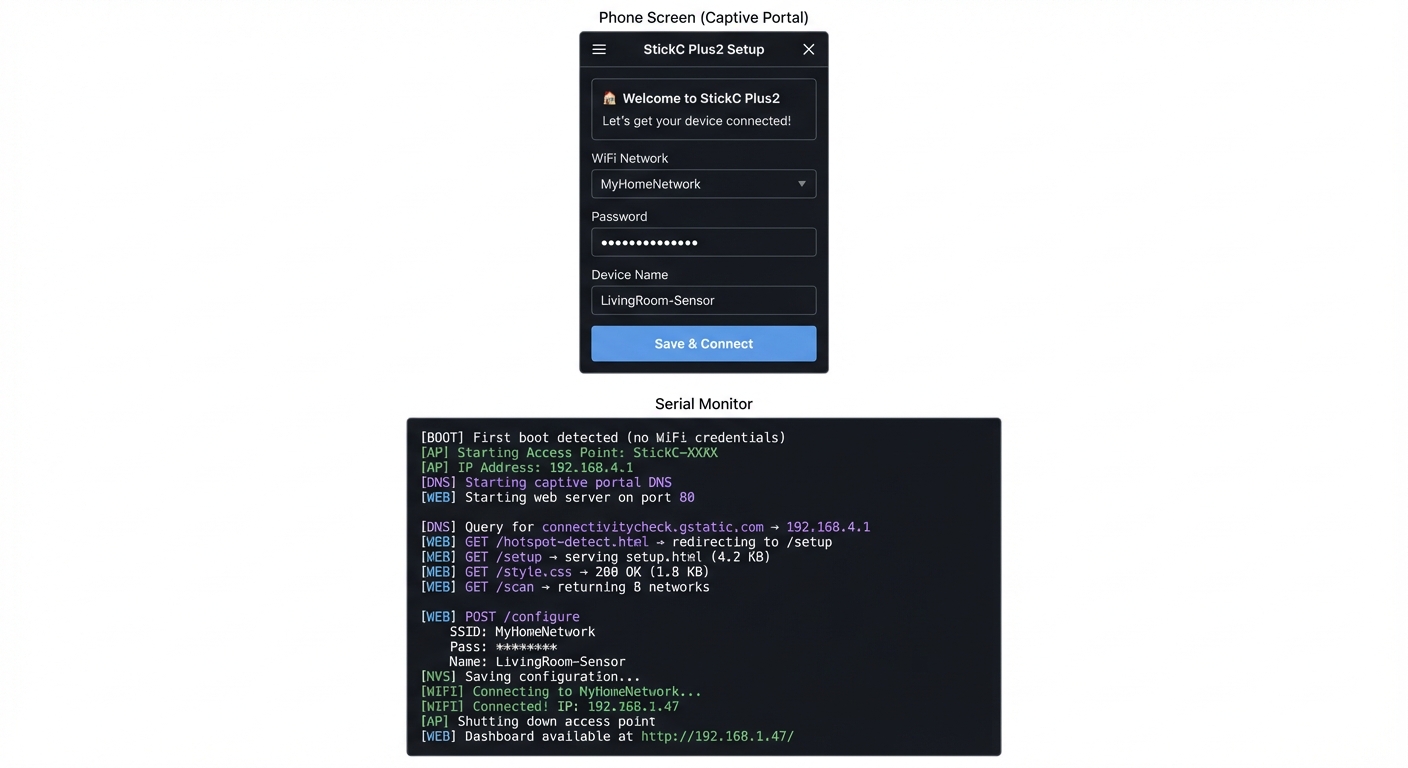

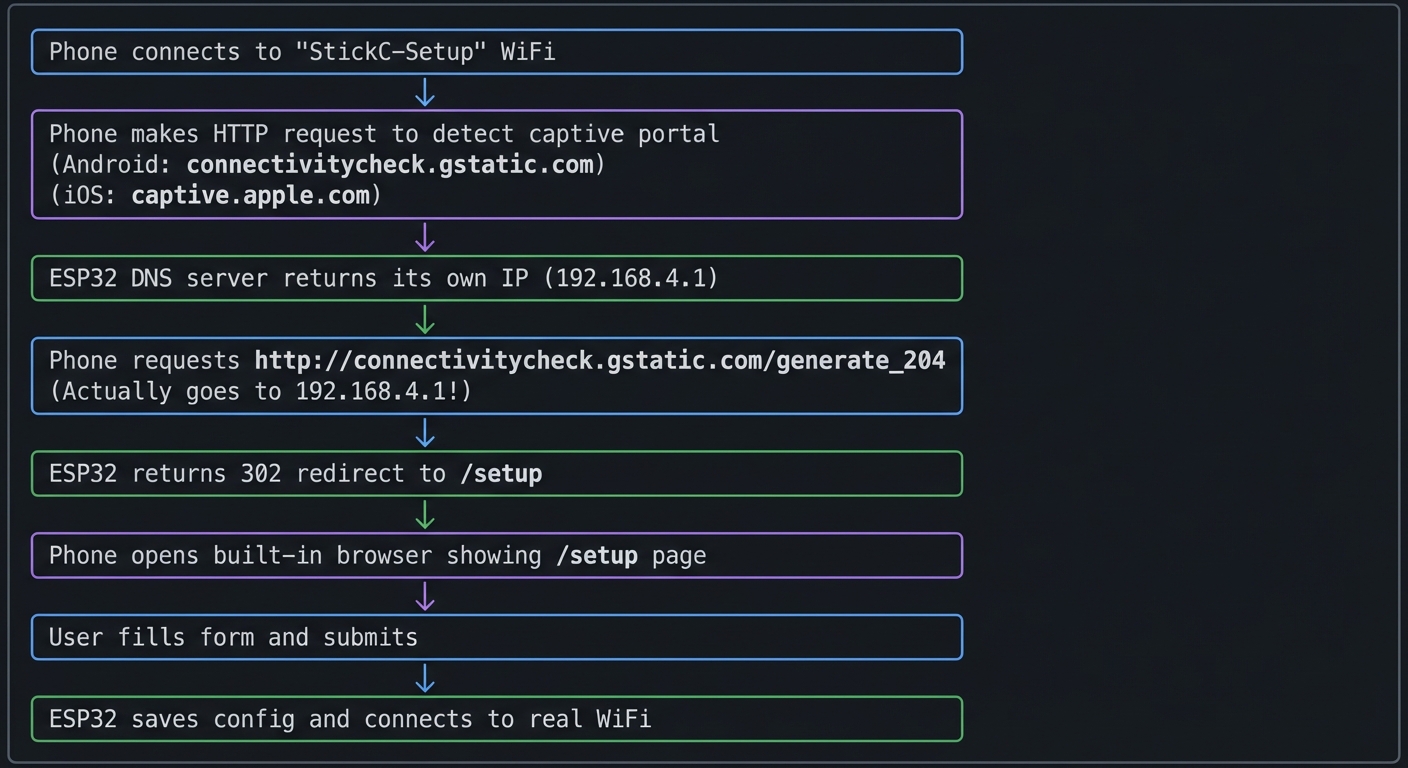

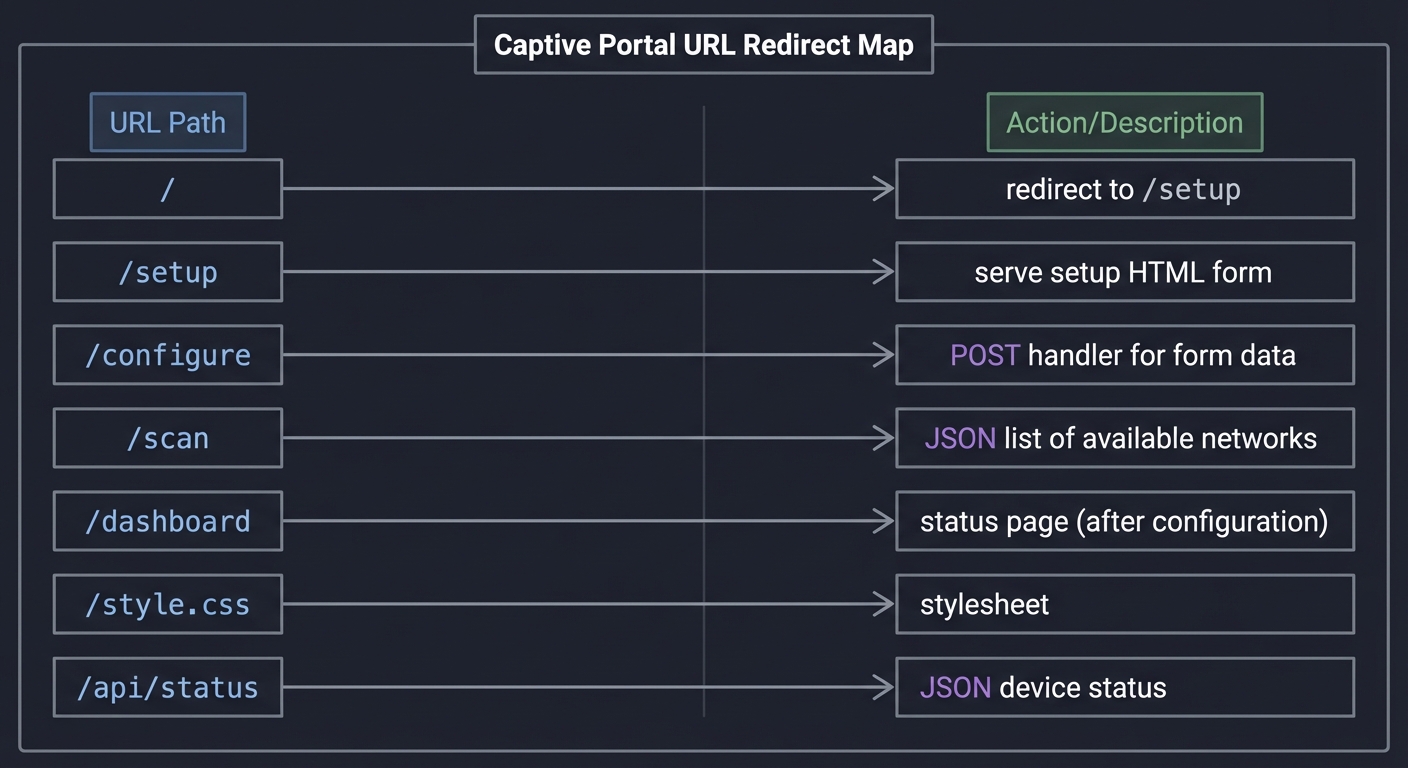

Project 2: Environmental Monitor with Cloud Dashboard (WiFi & MQTT)

- File: LEARN_M5STACK_STICKC_PLUS2_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: C++ (Arduino)

- Alternative Programming Languages: MicroPython, ESP-IDF (C)

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 3. The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: WiFi Networking, MQTT Protocol, IoT Architecture

- Software or Tool: PubSubClient (MQTT), ENV Hat III, Home Assistant

- Main Book: “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” by Martin Kleppmann

What you’ll build: A wireless environmental sensor station that reads temperature, humidity, and pressure from an ENV Hat, publishes data to an MQTT broker, and displays current readings on the device while a web dashboard shows historical trends.

Why it teaches IoT architecture: This is THE fundamental IoT pattern: sense → process → transmit → visualize. You’ll understand the complete data pipeline from physical sensor to cloud storage, learning MQTT’s publish/subscribe model that powers billions of IoT devices.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Connecting to WiFi reliably → maps to network stack initialization and error handling

- Understanding MQTT pub/sub → maps to message broker architecture

- Formatting sensor data for transmission → maps to JSON serialization and data schemas

- Handling network failures gracefully → maps to resilient IoT design patterns

Key Concepts:

- MQTT Protocol: Designing Data-Intensive Applications Ch. 4 - Martin Kleppmann

- WiFi Connection Management: ESP32 WiFi documentation - Espressif

- JSON Serialization: ArduinoJson library documentation - Benoît Blanchon

- I2C Sensor Reading: The Book of I2C Ch. 4 - Randall Hyde

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 1 week Prerequisites: Project 1 completed, basic understanding of WiFi/internet concepts, comfort with JSON format

Real World Outcome

You’ll have a complete IoT environmental monitoring system:

- The device wakes up, connects to WiFi, reads sensors

- Current readings display on the screen with trend indicators

- Data publishes to MQTT broker every 30 seconds

- A dashboard (Home Assistant, Node-RED, or custom) shows graphs

Example Output:

Device Display:

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ 🌡️ ENVIRONMENT MONITOR │

├──────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ Temperature Humidity Pressure │

│ 23.4°C ↗ 65.2% ↘ 1013.2 hPa │

│ │

│ WiFi: ████░ -52dBm MQTT: Connected │

│ Last TX: 12s ago Uptime: 2h 34m │

│ │

│ [A] Force Send [B] Settings │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Serial Monitor:

[WIFI] Connecting to MyNetwork... OK (-54 dBm)

[MQTT] Connecting to mqtt.local:1883... OK

[SENSOR] ENV3 detected at 0x44 (SHT30) + 0x76 (QMP6988)

[SENSOR] Temp: 23.42°C, Humidity: 65.18%, Pressure: 1013.25 hPa

[MQTT] Publishing to sensors/env/office...

{

"device_id": "stickc-01",

"temperature": 23.42,

"humidity": 65.18,

"pressure": 1013.25,

"battery": 87,

"rssi": -54,

"timestamp": 1703847600

}

[MQTT] Published successfully (124 bytes)

[SLEEP] Next reading in 30 seconds...

Dashboard (Home Assistant/Node-RED):

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Office Environment Last 24 hours │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Temperature │

│ 26°┤ ╭───╮ │

│ 24°┤ ╭─────────╯ ╰───────────╮ │

│ 22°┤────────╯ ╰─────── │

│ 20°┼────────────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ └────────────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ 0:00 6:00 12:00 18:00 Now │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do IoT devices reliably send sensor data to the cloud while handling real-world network failures?”

Before you write any code, sit with this question. Your home WiFi drops occasionally. Your MQTT broker might restart. Power might fluctuate. A real IoT device must handle all these gracefully—buffering data, reconnecting automatically, and never losing measurements. This is what separates a hobby project from a production device.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- MQTT Protocol Fundamentals

- What is a broker and why doesn’t MQTT use direct client-to-client?

- What are topics and how does the hierarchy work (e.g., home/office/temperature)?

- What are QoS levels 0, 1, 2 and when would you use each?

- What is a “retained” message and why is it useful?

- Book Reference: “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” Ch. 4 - Kleppmann

- WiFi Connection Lifecycle

- What happens between calling WiFi.begin() and being connected?

- What is DHCP and how does your device get an IP address?

- What is RSSI and what values indicate good/poor signal?

- Book Reference: “Computer Networks” Ch. 6 - Tanenbaum

- I2C Multi-Sensor Communication

- How does I2C addressing work when multiple devices share the bus?

- How do you discover devices on the I2C bus (scanning)?

- Book Reference: “The Book of I2C” Ch. 4 - Randall Hyde

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Reliability

- What should happen if WiFi connection fails?

- Should you buffer readings locally if MQTT is unreachable?

- How many readings will you store, and where (RAM vs Flash)?

- Data Format

- What fields does your JSON payload need?

- How will you include a timestamp if the device has no internet time?

- Should you use NTP to sync time?

- Power Strategy

- Should the device stay on continuously or use deep sleep?

- If deep sleep, how do you maintain MQTT connection state?

- What’s the tradeoff between update frequency and battery life?

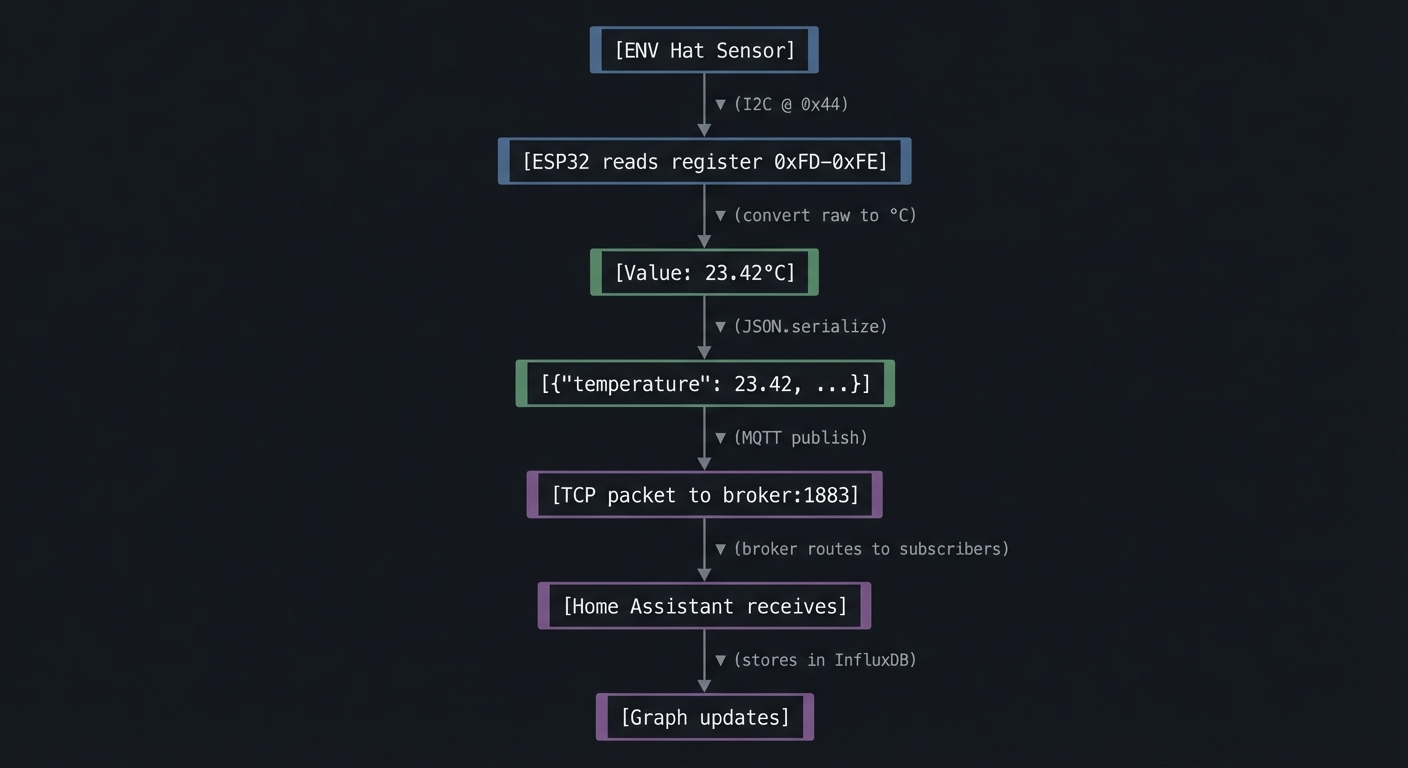

Thinking Exercise

Map the Data Flow

Before coding, diagram the complete path of a temperature reading:

[ENV Hat Sensor]

│

▼ (I2C @ 0x44)

[ESP32 reads register 0xFD-0xFE]

│

▼ (convert raw to °C)

[Value: 23.42°C]

│

▼ (JSON.serialize)

[{"temperature": 23.42, ...}]

│

▼ (MQTT publish)

[TCP packet to broker:1883]

│

▼ (broker routes to subscribers)

[Home Assistant receives]

│

▼ (stores in InfluxDB)

[Graph updates]

Questions while mapping:

- How many bytes is one JSON payload?

- At 30-second intervals, how much data per day?

- If the broker is 100ms away, how much latency is acceptable?

- What happens to subscribers if they’re offline when you publish?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “Compare MQTT with HTTP for IoT applications. When would you choose each?”

- “What is the publish/subscribe pattern and why is it suited for IoT?”

- “How would you handle a scenario where network is unavailable for hours?”

- “Explain MQTT QoS levels and their delivery guarantees.”

- “How would you secure MQTT communication for production IoT devices?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start Simple

Get WiFi connected first. Use WiFi.status() == WL_CONNECTED to verify. Print your IP address to serial.

Hint 2: Add MQTT

Install PubSubClient library. Connect to a free broker like test.mosquitto.org for testing. Subscribe to your own topic to verify messages arrive.

Hint 3: Add Sensors The ENV Hat III uses SHT30 (temp/humidity at 0x44) and QMP6988 (pressure at 0x76). Use Wire.h to scan for devices first.

Hint 4: Error Handling Wrap network operations in retry loops with exponential backoff:

int retries = 0;

while (!mqtt.connect() && retries < 5) {

delay(1000 * (1 << retries)); // 1s, 2s, 4s, 8s, 16s

retries++;

}

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem: “MQTT publishes but dashboard is empty”

- Why: Wrong topic or broker auth

- Fix: Verify topic strings and credentials; test with a known client

- Quick test: Use mosquitto_sub to confirm messages arrive

Problem: “Device stops updating after WiFi drop”

- Why: No reconnect loop or stale socket

- Fix: Implement reconnect + re-subscribe logic

- Quick test: Disable WiFi router for 30s and verify recovery

Definition of Done

- Publishes sensor data to MQTT/HTTP reliably

- Dashboard updates in near real time

- Reconnect logic survives WiFi outages

- Credentials stored securely in NVS

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| MQTT architecture | “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” by Kleppmann | Ch. 4 |

| Network reliability | “Release It!” by Nygard | Ch. 4-5 |

| I2C sensors | “The Book of I2C” by Randall Hyde | Ch. 4 |

| JSON in embedded | ArduinoJson documentation | Tutorial section |

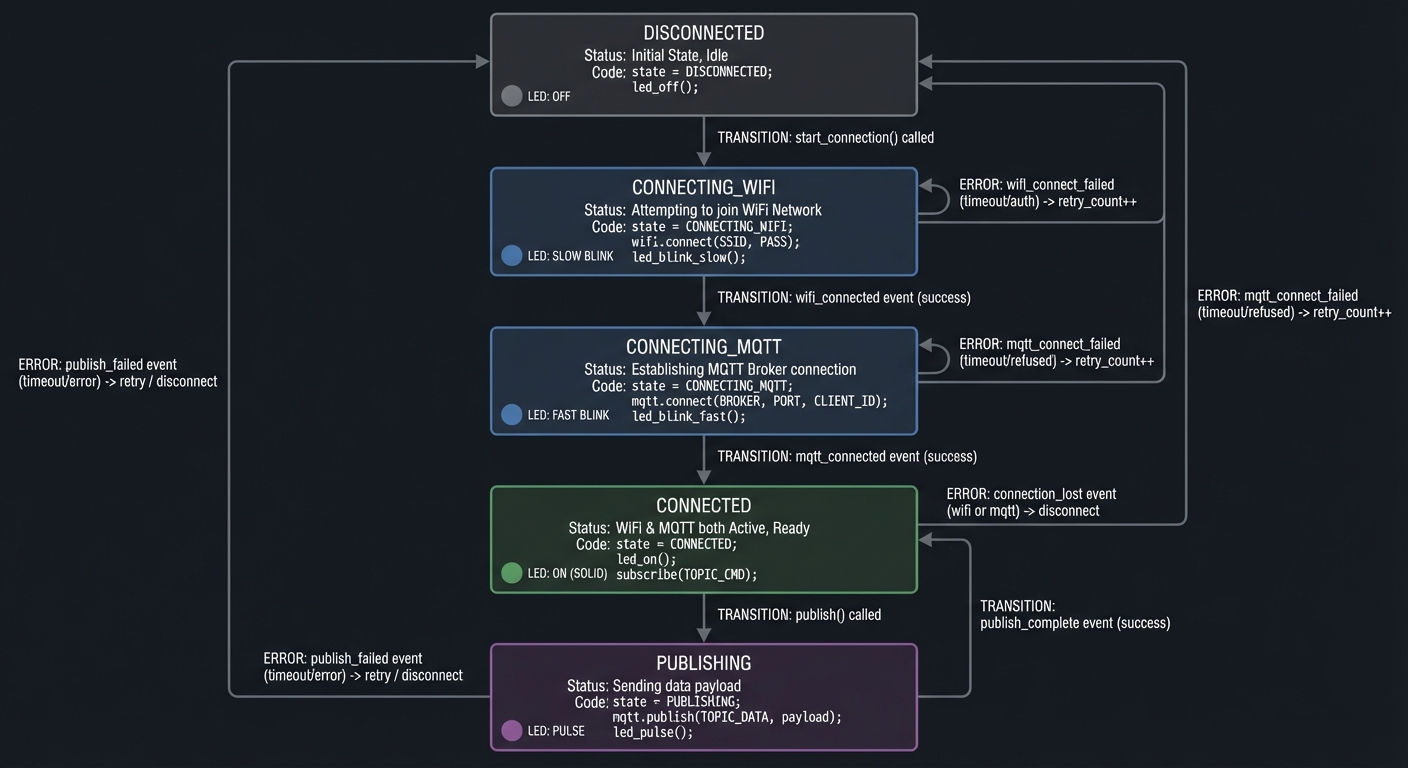

Implementation Hints

The key architectural pattern is the state machine for connection management:

States: DISCONNECTED → CONNECTING_WIFI → CONNECTING_MQTT → CONNECTED → PUBLISHING

Each state handles its own errors and knows how to transition. Don’t try to do everything in one big if-else chain.

For the ENV Hat III, M5Stack provides the M5Unit-ENV library. Study how it abstracts the I2C communication for multiple sensors.

Consider using NTP to sync time so your timestamps are meaningful. The configTime() function in ESP32 makes this easy.

Learning milestones:

- Device connects to WiFi and prints IP → You understand network initialization

- MQTT messages arrive at broker → You understand pub/sub

- Dashboard shows live sensor data → You’ve built a complete IoT pipeline

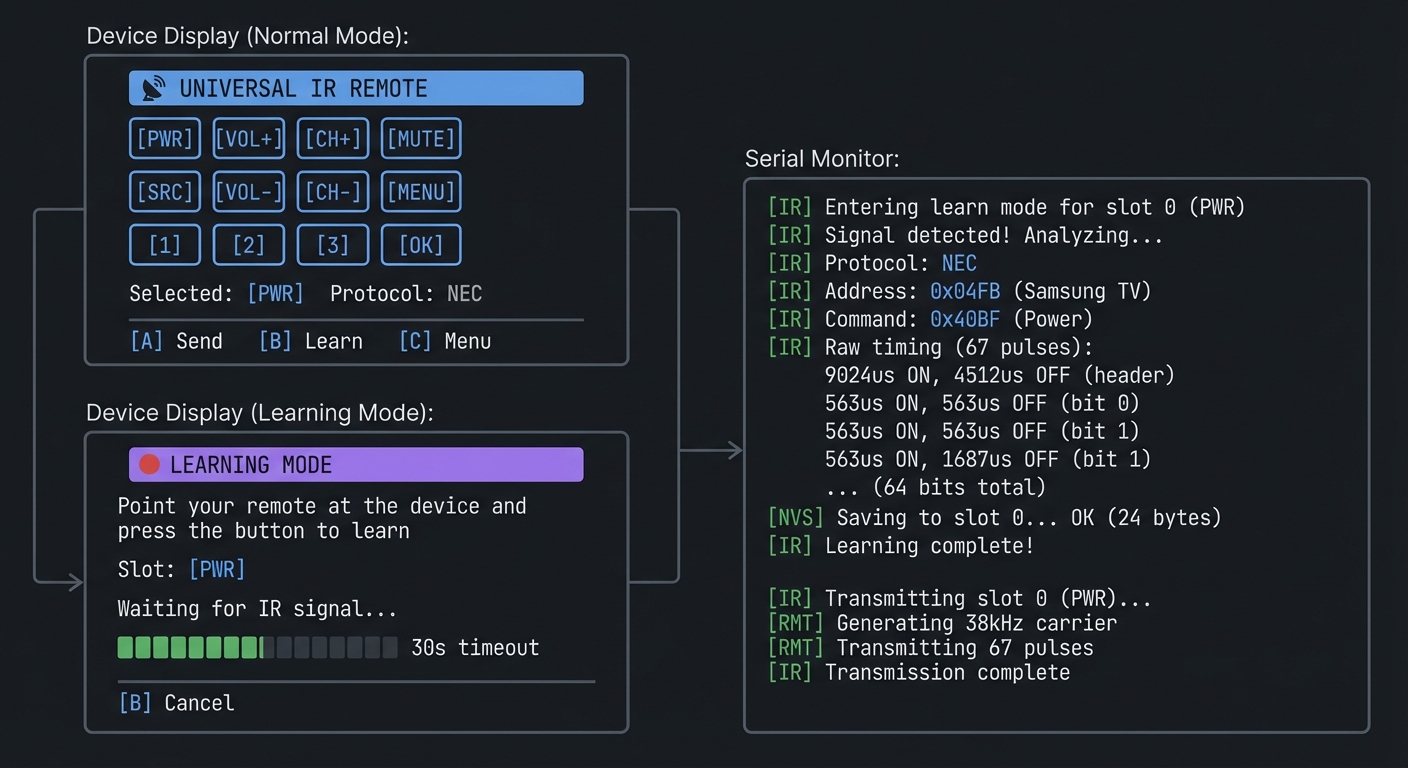

Project 3: Universal IR Remote with Learning Mode (IR Protocol Mastery)

- File: LEARN_M5STACK_STICKC_PLUS2_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: C++ (Arduino)

- Alternative Programming Languages: MicroPython, ESP-IDF (C)

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 2. The “Micro-SaaS / Pro Tool”

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: IR Protocols, Signal Processing, NEC Encoding

- Software or Tool: IRremote library, ESP32 RMT peripheral

- Main Book: “Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Edition” by Elecia White

What you’ll build: A programmable IR remote that can learn commands from any IR remote (TV, AC, soundbar), store them in flash memory, and replay them on demand—using the built-in IR emitter and optionally an IR receiver module.

Why it teaches protocol engineering: IR remotes seem like magic until you understand the encoding. You’ll decode timing-based protocols (NEC, RC5, Sony), see how manufacturers distinguish commands, and understand why “timing is everything” in embedded systems.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Understanding pulse-distance encoding → maps to how digital data becomes analog signals

- Decoding captured IR signals → maps to signal processing and timing analysis

- Using the ESP32 RMT peripheral → maps to hardware acceleration for timing-critical tasks

- Storing learned codes persistently → maps to flash storage and data serialization

Key Concepts:

- NEC IR Protocol: IR Remote Control Theory - SB-Projects reference

- RMT Peripheral: ESP32 Technical Reference Manual - Espressif

- Timing-Critical I/O: Making Embedded Systems Ch. 5 - Elecia White

- Non-Volatile Storage: Making Embedded Systems Ch. 9 - Elecia White

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 1 week Prerequisites: Basic understanding of binary/hex, experience with GPIO

Real World Outcome

You’ll have a pocket-sized universal remote that can:

- Learn IR codes from existing remotes

- Store 20+ commands in flash memory

- Display a button grid for stored commands

- Transmit learned codes on button press

Example Output:

Device Display (Normal Mode):

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ 📡 UNIVERSAL IR REMOTE │

├──────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ [PWR] [VOL+] [CH+] [MUTE] │

│ │

│ [SRC] [VOL-] [CH-] [MENU] │

│ │

│ [1] [2] [3] [OK] │

│ │

│ Selected: [PWR] Protocol: NEC │

│ [A] Send [B] Learn [C] Menu │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Device Display (Learning Mode):

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ 🔴 LEARNING MODE │

├──────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ Point your remote at the device │

│ and press the button to learn │

│ │

│ Slot: [PWR] │

│ │

│ Waiting for IR signal... │

│ ▓▓▓▓▓▓░░░░░░░░░░░░ 30s timeout │

│ │

│ [B] Cancel │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Serial Monitor:

[IR] Entering learn mode for slot 0 (PWR)

[IR] Signal detected! Analyzing...

[IR] Protocol: NEC

[IR] Address: 0x04FB (Samsung TV)

[IR] Command: 0x40BF (Power)

[IR] Raw timing (67 pulses):

9024us ON, 4512us OFF (header)

563us ON, 563us OFF (bit 0)

563us ON, 1687us OFF (bit 1)

... (64 bits total)

[NVS] Saving to slot 0... OK (24 bytes)

[IR] Learning complete!

[IR] Transmitting slot 0 (PWR)...

[RMT] Generating 38kHz carrier

[RMT] Transmitting 67 pulses

[IR] Transmission complete

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do TV remotes encode button presses into invisible light pulses, and how can you decode and recreate these signals?”

Before you write any code, sit with this question. An IR remote sends nothing but flashes of 940nm light—invisible to humans but visible to cameras. Yet somehow, your TV knows the difference between “Volume Up” and “Channel Down” from these flashes. The answer is timing—precisely timed bursts encode binary data.

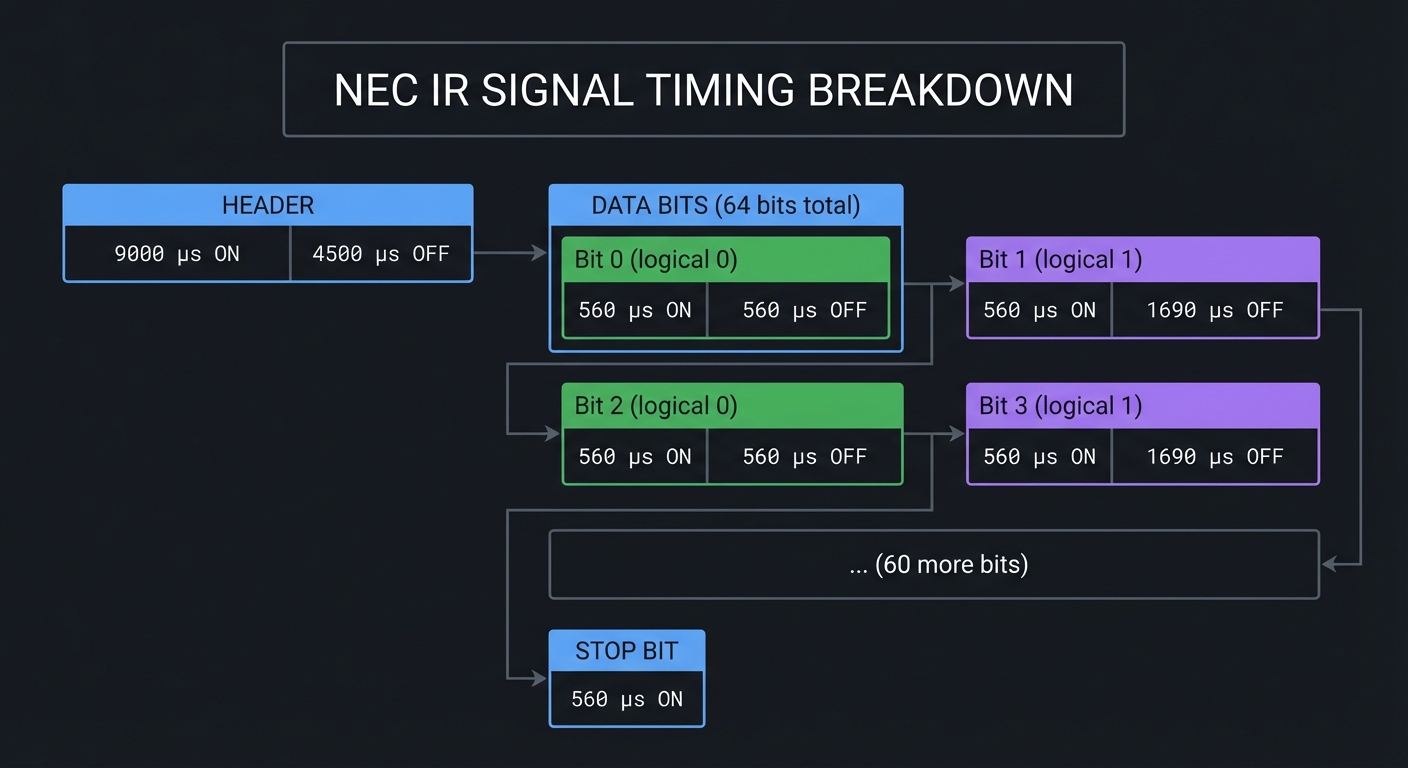

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Pulse Distance/Width Modulation

- What is a “mark” and a “space” in IR communication?

- How does NEC encode a 0 vs a 1?

- Why is the carrier frequency 38kHz?

- Reference: SB-Projects IR Remote Control Theory

- The NEC Protocol

- What does a complete NEC message look like?

- What are the address and command fields?

- Why does NEC send inverted copies of address and command?

- How does NEC repeat work (vs sending the full code again)?

- Reference: SB-Projects NEC Protocol Specification

- ESP32 RMT Peripheral

- What is RMT and why is it better than bit-banging GPIO?

- How does RMT handle microsecond-precision timing?

- How does RMT generate the 38kHz carrier signal?

- Reference: ESP-IDF RMT Documentation

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Learning Mode

- How will you detect the start of an IR signal?

- How long should you wait before timing out?

- How do you distinguish signal from noise?

- Protocol Detection

- NEC uses a 9ms header, Sony uses 2.4ms—how will you tell them apart?

- Should you store raw timings or decode to protocol format?

- What if you encounter an unknown protocol?

- Storage

- How much data does one IR code require?

- How many codes can you fit in flash?

- Should you use NVS, SPIFFS, or raw flash partitions?

Thinking Exercise

Decode an NEC Signal by Hand

Given this timing sequence (in microseconds):

9000 ON, 4500 OFF, <- Header

560 ON, 560 OFF, <- Bit 0 (logical 0)

560 ON, 1690 OFF, <- Bit 1 (logical 1)

560 ON, 560 OFF, <- Bit 2 (logical 0)

560 ON, 1690 OFF, <- Bit 3 (logical 1)

... (60 more bits)

560 ON <- Stop bit

Questions while decoding:

- The header is always 9ms ON + 4.5ms OFF. How would you detect this programmatically?

- A short space (560µs) means 0, a long space (1690µs) means 1. Why not use ON time instead?

- 32 bits total: 8 address + 8 address_inverse + 8 command + 8 command_inverse. Why send inverses?

- If you receive

0x04 0xFB 0x40 0xBF, what are the address and command? (Answer: address=0x04, command=0x40)

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “Explain how NEC infrared encoding works at the bit level.”

- “Why do IR remotes use a 38kHz carrier frequency?”

- “How would you implement a timeout when waiting for IR signals?”

- “What are the advantages of using a hardware peripheral (RMT) vs bit-banging GPIO?”

- “How would you store configuration data persistently on an ESP32?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start With Receiving Use an IR receiver module (like VS1838B) on a Grove port. The IRremoteESP8266 library can decode common protocols automatically.

Hint 2: Understand Raw Mode When decoding, capture raw timings first. You can analyze protocol later. Store an array of microsecond values for each mark/space.

Hint 3: Transmitting The StickC Plus2 has a built-in IR LED on GPIO9. For NEC transmission, you need to generate a 38kHz PWM carrier, then modulate it with your timing sequence.

Hint 4: RMT Configuration ESP32’s RMT can handle both receiving and transmitting. For TX, configure carrier frequency and pulse patterns. For RX, set up the receiver to capture edges.

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem: “IR codes do not trigger target device”

- Why: Wrong carrier frequency or timing

- Fix: Match protocol timing and 38kHz carrier

- Quick test: Measure output with a phone camera or IR receiver

Problem: “Learning mode returns inconsistent codes”

- Why: Noisy signal or incorrect sampling

- Fix: Average multiple captures and use proper gap detection

- Quick test: Capture the same remote 5x and compare hashes

Definition of Done

- Learns and replays at least 5 IR codes

- Protocol decoding identifies common formats

- Codes persist across reboot (NVS)

- UI allows test-send and delete

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Timing-critical I/O | “Making Embedded Systems” by Elecia White | Ch. 5 |

| Hardware peripherals | ESP32 Technical Reference Manual | Ch. 15 (RMT) |

| Data persistence | “Making Embedded Systems” by Elecia White | Ch. 9 |

| Signal processing | “The Art of Electronics” by Horowitz & Hill | Ch. 10 |

Implementation Hints

The key insight is that IR transmission is really about precise timing. The ESP32’s RMT peripheral exists specifically for this—it can generate timing patterns with microsecond accuracy while your CPU does other things.

For learning mode:

- Configure RMT in receive mode

- Wait for signal (edge detection)

- Capture all timing pairs until gap > 20ms

- Analyze header to identify protocol

- Decode bits based on protocol rules

For transmitting:

- Build RMT item array with timing pairs

- Configure carrier (38kHz, 33% duty cycle)

- Send and wait for completion

Store learned codes using ESP32’s NVS (Non-Volatile Storage) library—it handles wear leveling and provides a key-value API.

Learning milestones:

- You can read and print raw IR timings → You understand signal capture

- You can decode NEC address and command → You understand the protocol

- Your device can control a real TV → You’ve mastered IR transmission

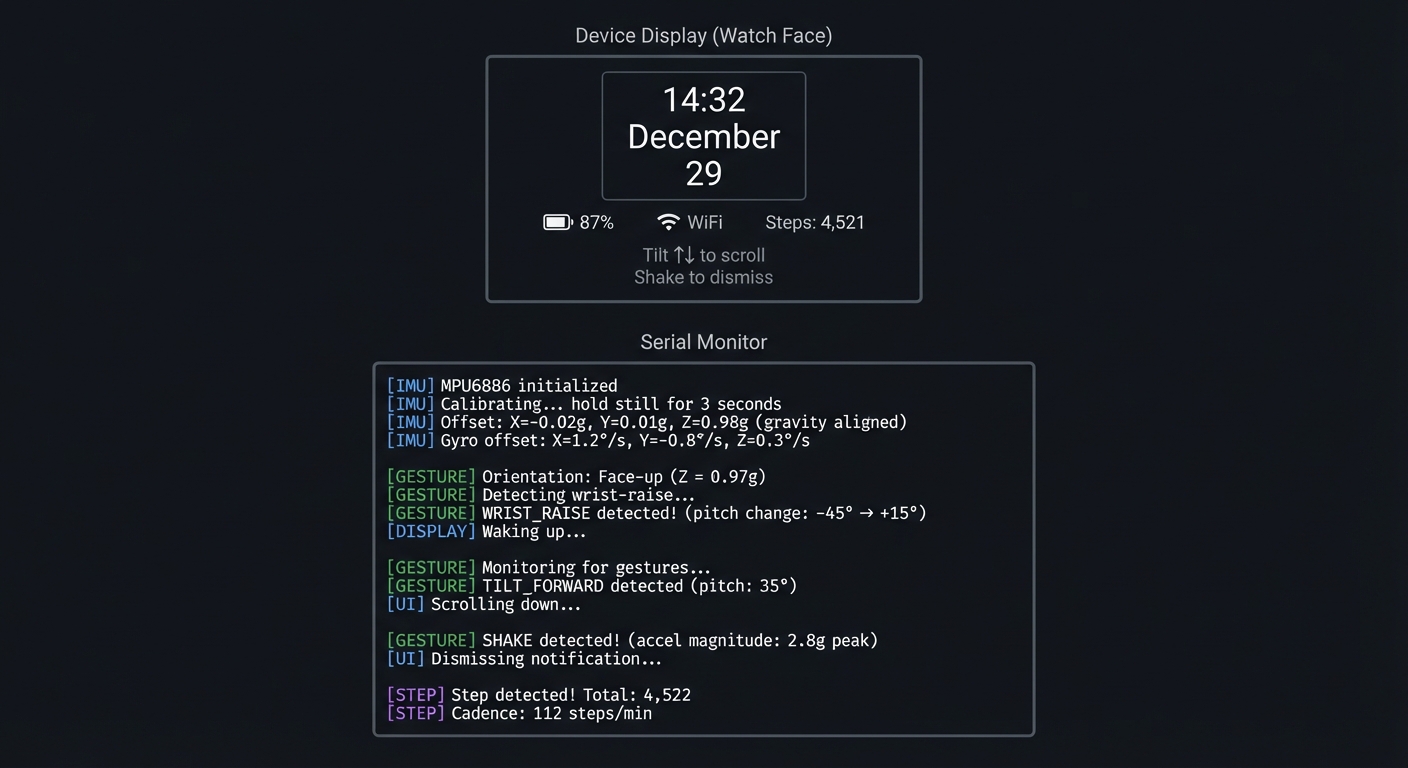

Project 4: Motion-Activated Smart Watch with Gesture Control (IMU Mastery)

- File: LEARN_M5STACK_STICKC_PLUS2_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: C++ (Arduino)

- Alternative Programming Languages: MicroPython, CircuitPython

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 2. The “Micro-SaaS / Pro Tool”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: IMU Sensors, Gesture Recognition, Signal Processing

- Software or Tool: MPU6886, M5Unified, Watch accessories

- Main Book: “Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Edition” by Elecia White

What you’ll build: A wearable smart watch that wakes on wrist-raise, displays time/date/battery, recognizes gestures (shake to dismiss, tilt to scroll), and demonstrates how fitness trackers detect motion patterns.

Why it teaches sensor fusion: The IMU (accelerometer + gyroscope) is the core sensor in every fitness tracker, phone rotation, and game controller. You’ll learn to read raw sensor data, filter noise, detect events, and combine multiple axes into meaningful gestures—skills that transfer to any motion-sensing project.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Calibrating the IMU at startup → maps to sensor offset and drift correction

- Detecting orientation from acceleration → maps to gravity vector decomposition

- Recognizing gestures from motion patterns → maps to state machines and threshold detection

- Minimizing power while monitoring motion → maps to sampling strategies and interrupts

Key Concepts:

- Accelerometer Physics: Making Embedded Systems Ch. 7 - Elecia White

- Sensor Calibration: MPU6886 datasheet - TDK InvenSense

- Low-Pass Filtering: The Art of Electronics Ch. 8 - Horowitz & Hill

- Power Optimization: Making Embedded Systems Ch. 10 - Elecia White

Difficulty: Advanced Time estimate: 2 weeks Prerequisites: Projects 1-2 completed, basic trigonometry, understanding of 3D coordinate systems

Real World Outcome

You’ll have a functional smart watch with:

- Always-on clock that wakes on wrist-raise gesture

- Gesture recognition for navigation (tilt, shake, tap)

- Step counter demonstration

- Orientation visualization

Example Output:

Device Display (Watch Face):

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ │

│ ┌─────────────┐ │

│ │ 14:32 │ │

│ │ December │ │

│ │ 29 │ │

│ └─────────────┘ │

│ │

│ 🔋 87% 📶 WiFi Steps: 4,521 │

│ │

│ Tilt ↑↓ to scroll Shake to dismiss │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Serial Monitor:

[IMU] MPU6886 initialized

[IMU] Calibrating... hold still for 3 seconds

[IMU] Offset: X=-0.02g, Y=0.01g, Z=0.98g (gravity aligned)

[IMU] Gyro offset: X=1.2°/s, Y=-0.8°/s, Z=0.3°/s

[GESTURE] Orientation: Face-up (Z = 0.97g)

[GESTURE] Detecting wrist-raise...

[GESTURE] WRIST_RAISE detected! (pitch change: -45° → +15°)

[DISPLAY] Waking up...

[GESTURE] Monitoring for gestures...

[GESTURE] TILT_FORWARD detected (pitch: 35°)

[UI] Scrolling down...

[GESTURE] SHAKE detected! (accel magnitude: 2.8g peak)

[UI] Dismissing notification...

[STEP] Step detected! Total: 4,522

[STEP] Cadence: 112 steps/min

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do smartphones and fitness trackers know which way they’re oriented and detect motion patterns like steps or gestures?”

Before you write any code, sit with this question. Your phone knows when you rotate it. Your fitness tracker counts steps. Your game controller knows when you swing it. All of this comes from a tiny chip measuring acceleration and rotation—but the raw data is noisy, ambiguous, and needs interpretation.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Accelerometer Basics

- What does an accelerometer actually measure (hint: not just motion)?

- Why does a stationary device read ~1g on one axis?

- How do you separate gravity from actual acceleration?

- Book Reference: “Making Embedded Systems” Ch. 7 - Elecia White

- Gyroscope and Integration

- What does a gyroscope measure (angular velocity, not angle)?

- Why does integrating gyro data lead to drift?

- What is sensor fusion and why is it needed?

- Reference: MPU6886 Application Note - TDK InvenSense

- Digital Filtering

- What is a low-pass filter and why is it needed?

- How do you implement a simple moving average?

- What is an exponential moving average (EMA)?

- Book Reference: “The Art of Electronics” Ch. 8 - Horowitz & Hill

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Orientation Detection

- If the device is tilted 45°, what will the X, Y, Z acceleration values be?

- How do you calculate pitch and roll from accelerometer readings?

- What happens to your calculation if the device is being shaken?

- Gesture Recognition

- How will you distinguish a “shake” from normal arm movement?

- What defines a “wrist raise” gesture?

- How do you avoid false positives while still being responsive?

- Power Management

- Should you sample the IMU continuously or use interrupts?

- What sample rate is needed for gesture detection vs step counting?

- How can you put the IMU into low-power mode when the display is off?

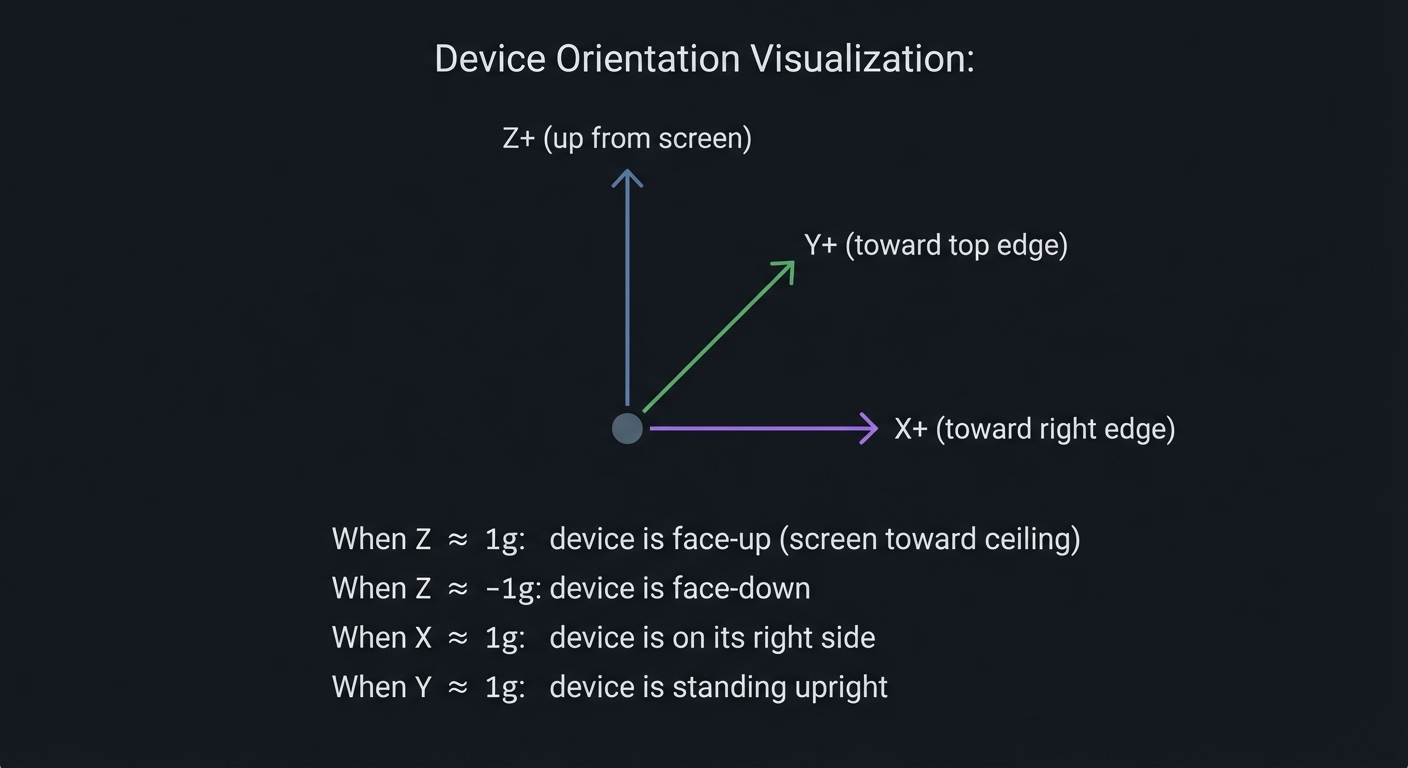

Thinking Exercise

Calculate Orientation from Gravity

The accelerometer at rest reads: X = 0.12g, Y = -0.05g, Z = 0.99g

Questions to work through:

- Is this device “upright” or tilted? How do you know?

- Calculate the pitch angle: pitch = atan2(Y, sqrt(X² + Z²))

- Calculate the roll angle: roll = atan2(X, Z)

- If Z were negative, what would that mean about device orientation?

- The values don’t add to exactly 1g—why might that be?

Device Orientation Visualization:

Z+ (up from screen)

▲

│

│ Y+ (toward top edge)

│ ╱

│ ╱

│ ╱

●───────► X+ (toward right edge)

When Z ≈ 1g: device is face-up (screen toward ceiling)

When Z ≈ -1g: device is face-down

When X ≈ 1g: device is on its right side

When Y ≈ 1g: device is standing upright

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “How does an accelerometer work and what does it actually measure?”

- “Explain how you would implement step detection using an accelerometer.”

- “What is sensor fusion and why is it important for orientation tracking?”

- “How would you filter noisy sensor data in a resource-constrained environment?”

- “Describe the tradeoffs between sampling rate and power consumption for motion sensors.”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start With Raw Data Use M5.Imu.getAccelData() to read accelerometer values. Print them continuously and move the device to understand what each axis represents.

Hint 2: Calibrate at Startup The MPU6886 has manufacturing offsets. At startup, with device stationary, read 100 samples and compute the average—this is your offset. Subtract it from all future readings.

Hint 3: Implement Low-Pass Filter

For smooth orientation, use EMA: filtered = alpha * new_value + (1 - alpha) * filtered. Try alpha = 0.1 for stable readings.

Hint 4: Gesture State Machine Don’t just check thresholds—use states. For wrist-raise: (1) arm down (pitch < -30°), (2) arm rising (pitch increasing), (3) arm up (pitch > 0°). Only trigger on the full sequence.

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem: “Gesture detection is unstable”

- Why: Gyro drift or no filtering

- Fix: Calibrate on startup and apply low-pass filter

- Quick test: Hold device still and verify bias goes to zero

Problem: “Watch wakes too often”

- Why: Wake thresholds too sensitive

- Fix: Tune motion threshold and add debounce

- Quick test: Log wake events over 1 hour and review rate

Definition of Done

- Gesture detection works with calibrated IMU

- Wake-on-motion works with debounce

- Display updates without lag during motion

- Battery life improved vs always-on

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Sensor physics | “Making Embedded Systems” by Elecia White | Ch. 7 |

| Signal filtering | “The Art of Electronics” by Horowitz & Hill | Ch. 8 |

| Power optimization | “Making Embedded Systems” by Elecia White | Ch. 10 |

| Motion algorithms | “Programming Embedded Systems” by Barr & Massa | Ch. 10 |

Implementation Hints

The key insight is that gesture recognition is a state machine, not a simple threshold check. A shake isn’t just “acceleration > 2g”—it’s “acceleration crossed threshold, then crossed back, multiple times within 500ms.”

For wrist-raise detection:

- Track pitch angle over time

- State IDLE: waiting for arm-down position (pitch < -30°)

- State RISING: pitch is increasing

- State TRIGGERED: pitch crossed into viewing range (pitch > 0°)

For step counting, look for periodic peaks in the accelerometer magnitude:

- Compute magnitude: sqrt(x² + y² + z²)

- Detect peaks (local maxima above threshold)

- Filter by time between peaks (humans walk at 0.5-3 Hz)

Learning milestones:

- You can read and print stable orientation (pitch/roll) → You understand accelerometer interpretation

- Wrist-raise wakes the display reliably → You understand gesture state machines

- Step counter matches actual steps within 10% → You understand signal processing

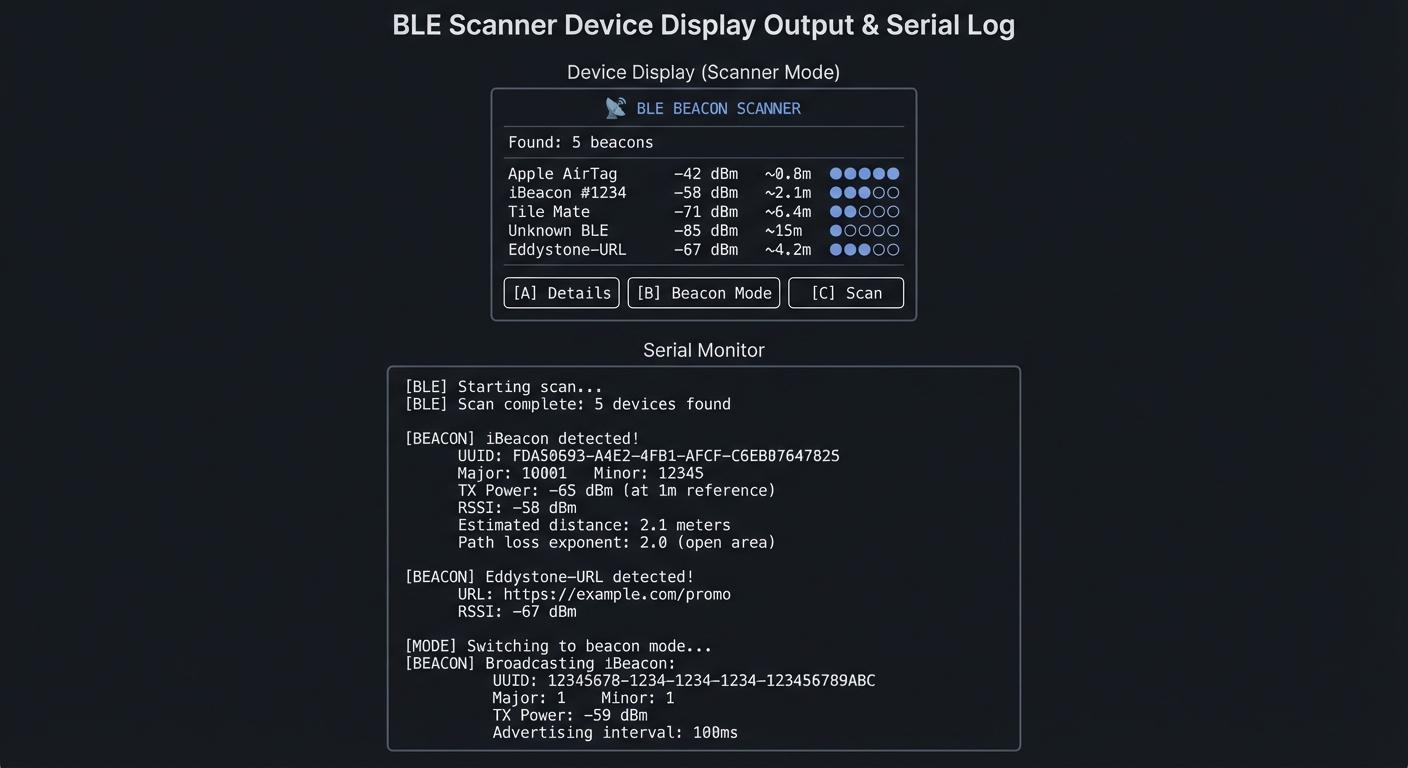

Project 5: BLE Beacon Proximity Scanner (Bluetooth Low Energy)

- File: LEARN_M5STACK_STICKC_PLUS2_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: C++ (Arduino)

- Alternative Programming Languages: ESP-IDF (C), MicroPython

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 3. The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: BLE Protocol, iBeacon, Proximity Detection

- Software or Tool: ESP32 BLE library, iBeacon protocol

- Main Book: “Getting Started with Bluetooth Low Energy” by Townsend (O’Reilly)

What you’ll build: A BLE scanner that detects nearby iBeacon and Eddystone beacons, estimates distance based on signal strength, and can also broadcast as a beacon itself—demonstrating the technology behind asset tracking, indoor navigation, and proximity marketing.

Why it teaches wireless protocols: BLE is fundamentally different from WiFi—it’s designed for low power, not high bandwidth. You’ll understand advertising packets, RSSI-to-distance conversion, and how retail stores know when you’re near a product display.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Understanding BLE advertising vs connected modes → maps to protocol stack design

- Parsing iBeacon packet format → maps to binary protocol parsing

- Estimating distance from RSSI → maps to RF propagation and signal processing

- Implementing beacon broadcasting → maps to constructing protocol packets

Key Concepts:

- BLE Architecture: Getting Started with Bluetooth Low Energy Ch. 2 - Townsend

- iBeacon Protocol: Apple iBeacon Specification

- RSSI and Path Loss: Computer Networks Ch. 2 - Tanenbaum

- Advertising Packets: ESP32 BLE documentation - Espressif

Difficulty: Advanced Time estimate: 1-2 weeks Prerequisites: Understanding of binary/hex, some networking concepts

Real World Outcome

You’ll have a handheld BLE scanner that:

- Scans for and displays nearby BLE devices

- Parses iBeacon UUID, major, minor values

- Estimates distance from RSSI

- Can switch to beacon mode and broadcast

Example Output:

Device Display (Scanner Mode):

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ 📡 BLE BEACON SCANNER │

├──────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ Found: 5 beacons │

│ │

│ 1. Apple AirTag -42 dBm ~0.8m ●●●●○ │

│ 2. iBeacon #1234 -58 dBm ~2.1m ●●●○○ │

│ 3. Tile Mate -71 dBm ~6.4m ●●○○○ │

│ 4. Unknown BLE -85 dBm ~15m ●○○○○ │

│ 5. Eddystone-URL -67 dBm ~4.2m ●●○○○ │

│ │

│ [A] Details [B] Beacon Mode [C] Scan │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Serial Monitor:

[BLE] Starting scan...

[BLE] Scan complete: 5 devices found

[BEACON] iBeacon detected!

UUID: FDA50693-A4E2-4FB1-AFCF-C6EB07647825

Major: 10001 Minor: 12345

TX Power: -65 dBm (at 1m reference)

RSSI: -58 dBm

Estimated distance: 2.1 meters

Path loss exponent: 2.0 (open area)

[BEACON] Eddystone-URL detected!

URL: https://example.com/promo

RSSI: -67 dBm

[MODE] Switching to beacon mode...

[BEACON] Broadcasting iBeacon:

UUID: 12345678-1234-1234-1234-123456789ABC

Major: 1 Minor: 1

TX Power: -59 dBm

Advertising interval: 100ms

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do stores know when you’re standing near a specific product, and how does indoor positioning work without GPS?”

Before you write any code, sit with this question. GPS doesn’t work indoors. Yet museums can trigger audio guides as you approach exhibits, and retailers can send you coupons when you’re near a product. BLE beacons are the technology enabling this—and understanding them teaches you about wireless protocols, signal propagation, and proximity estimation.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- BLE Advertising

- What is the difference between advertising and connected modes?

- How often do beacons advertise (interval)?

- What data can fit in an advertising packet (31 bytes)?

- Book Reference: “Getting Started with Bluetooth Low Energy” Ch. 2

- iBeacon Packet Format

- What are the 16-byte UUID, 2-byte major, and 2-byte minor values?

- What is the 1-byte TX Power field and what does it represent?

- How do you identify an iBeacon from a generic BLE advertisement?

- Reference: Apple iBeacon specification

- RSSI and Distance Estimation

- What is RSSI and how is it measured?

- Why is the relationship between RSSI and distance logarithmic?

- What is the path loss exponent and how does it vary by environment?

- Book Reference: “Computer Networks” Ch. 2 - Tanenbaum

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Scanning Strategy

- Should you scan continuously or periodically?

- How do you handle the same beacon appearing in multiple scans?

- How do you detect when a beacon has gone out of range?

- Distance Accuracy

- RSSI fluctuates by ±10 dBm—how do you smooth it?

- What environment factors affect signal strength?

- Is precise distance really achievable, or just proximity zones?

- Power vs Responsiveness

- Scanning uses significant power—how do you balance detection speed vs battery?

- In beacon mode, how does advertising interval affect power and detectability?

Thinking Exercise

Parse an iBeacon Packet

Given this raw advertising data (hex):

02 01 06 1A FF 4C 00 02 15

E2 C5 6D B5 DF FB 48 D2 B0 60 D0 F5 A7 10 96 E0

00 01 00 02 C5

Questions to decode:

- Bytes 5-6 are company ID (0x004C). Whose company ID is this? (Answer: Apple)

- Bytes 7-8 are beacon type (0x0215). What does 0x15 mean? (Answer: iBeacon, 21 bytes following)

- Bytes 9-24 are the UUID. Extract it in standard format (8-4-4-4-12)

- Bytes 25-26 are Major. What value? (Answer: 0x0001 = 1)

- Bytes 27-28 are Minor. What value? (Answer: 0x0002 = 2)

- Byte 29 is TX Power. If it’s 0xC5, what’s the signed value? (Answer: -59 dBm)

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “Explain the difference between BLE advertising and connection modes.”

- “How would you estimate the distance to a BLE beacon using RSSI?”

- “What are the practical limitations of BLE-based indoor positioning?”

- “Compare iBeacon with Eddystone. What are the tradeoffs?”

- “How would you optimize power consumption in a BLE scanning application?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Use the ESP32 BLE Library

Install ESP32 BLE library. Start with the “BLE_scan” example. The BLEAdvertisedDeviceCallbacks class receives every detected device.

Hint 2: Identify iBeacons

In the callback, check if getManufacturerData() starts with 4C 00 02 15. If so, it’s an Apple iBeacon. Parse the following 21 bytes.

Hint 3: Calculate Distance Use the log-distance path loss model:

distance = 10 ^ ((txPower - rssi) / (10 * n))

where n is the path loss exponent (typically 2.0 in open areas, 3.0-4.0 indoors).

Hint 4: Smooth RSSI RSSI fluctuates significantly. Use a Kalman filter or simple moving average over 5-10 readings to get stable distance estimates.

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem: “BLE scanner misses nearby devices”

- Why: Scan window/interval too short

- Fix: Increase scan window or use active scanning

- Quick test: Compare results with a phone BLE scanner

Problem: “RSSI values jump wildly”

- Why: No smoothing or poor antenna orientation

- Fix: Apply exponential moving average and clamp spikes

- Quick test: Log RSSI and verify smoothing reduces variance

Definition of Done

- Detects and lists nearby BLE devices

- RSSI smoothing produces stable distance estimate

- Scan interval and window are configurable

- Exportable log of sightings exists

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| BLE fundamentals | “Getting Started with Bluetooth Low Energy” | Ch. 1-3 |

| Signal propagation | “Computer Networks” by Tanenbaum | Ch. 2 |

| ESP32 BLE | ESP32 Programming Guide | BLE section |

| Indoor positioning | “Location-Based Services” by Schiller | Ch. 4 |

Implementation Hints

The key insight is that BLE advertising is broadcast—no connection needed. This makes it perfect for one-way information transmission (beacons) and discovery.

For scanning:

- Create

BLEScanobject with callback - Set active scan for more data (optional)

- Start scan for N seconds

- Process results in callback

For parsing iBeacons:

- Check manufacturer data exists and has correct prefix

- Extract UUID (bytes 4-19), Major (20-21), Minor (22-23), TX Power (24)

- Remember TX Power is signed byte

For beacon broadcasting:

- Create

BLEAdvertisementDatawith iBeacon prefix - Add your UUID, Major, Minor, TX Power

- Start advertising with desired interval

Learning milestones:

- You can scan and list all nearby BLE devices → You understand BLE advertising

- You can parse iBeacon data and display UUID/Major/Minor → You understand packet formats

- Your device can broadcast as a beacon and be detected by phone apps → You understand both directions

Project 6: Battery-Optimized Data Logger with Deep Sleep (Power Management)

- File: LEARN_M5STACK_STICKC_PLUS2_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: C++ (Arduino)

- Alternative Programming Languages: ESP-IDF (C), MicroPython

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 3. The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Power Management, Deep Sleep, RTC Memory

- Software or Tool: ESP32 sleep APIs, BM8563 RTC

- Main Book: “Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Edition” by Elecia White

What you’ll build: A data logger that samples environmental data at configurable intervals, stores readings in flash, and achieves weeks of battery life through aggressive deep sleep—demonstrating production-grade power optimization techniques.

Why it teaches power management: The 200mAh battery lasts about 50 minutes at full power. Yet commercial IoT sensors run for months on similar batteries. The secret is deep sleep—and understanding exactly what power is consumed where. This project teaches you to think about every microamp.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Configuring ESP32 deep sleep modes → maps to understanding power domains

- Persisting data across sleep cycles → maps to RTC memory and flash storage

- Using RTC for precise wake timing → maps to low-power timekeeping

- Optimizing wake time → maps to minimizing active power consumption

Key Concepts:

- ESP32 Power Modes: ESP32 Technical Reference Manual - Espressif

- RTC Memory: Making Embedded Systems Ch. 10 - Elecia White

- Flash Wear Leveling: Making Embedded Systems Ch. 9 - Elecia White

- Current Measurement: The Art of Electronics Ch. 15 - Horowitz & Hill

Difficulty: Advanced Time estimate: 1-2 weeks Prerequisites: Projects 1-2 completed, understanding of ESP32 memory architecture

Real World Outcome

You’ll have a long-running data logger that:

- Wakes at configurable intervals (1 min to 24 hours)

- Samples sensors quickly (<1 second wake time)

- Stores data in flash with timestamps

- Displays accumulated data on button press

- Runs for weeks on a single charge

Example Output:

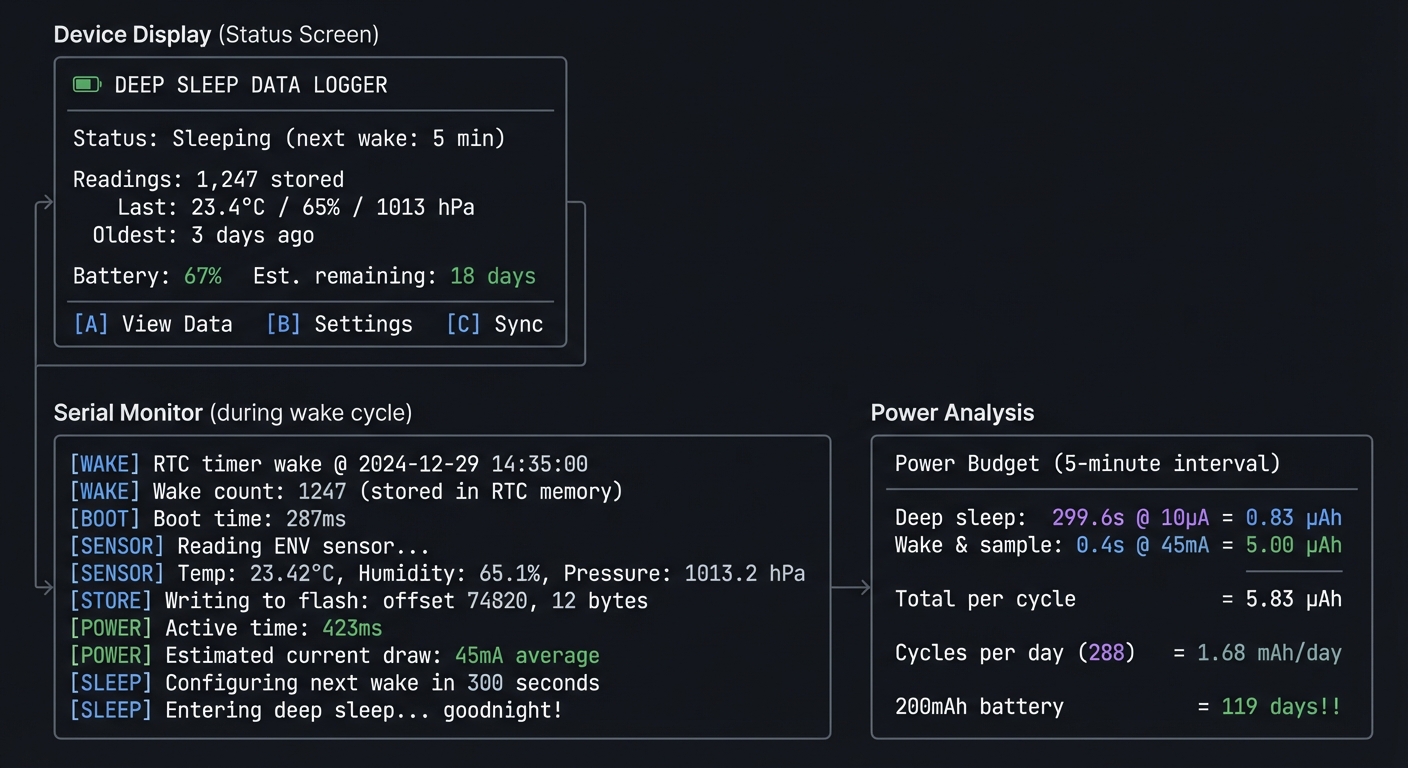

Device Display (Status Screen):

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ 🔋 DEEP SLEEP DATA LOGGER │

├──────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ Status: Sleeping (next wake: 5 min) │

│ │

│ Readings: 1,247 stored │

│ Last: 23.4°C / 65% / 1013 hPa │

│ Oldest: 3 days ago │

│ │

│ Battery: 67% Est. remaining: 18 days │

│ │

│ [A] View Data [B] Settings [C] Sync │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Serial Monitor (during wake cycle):

[WAKE] RTC timer wake @ 2024-12-29 14:35:00

[WAKE] Wake count: 1247 (stored in RTC memory)

[BOOT] Boot time: 287ms

[SENSOR] Reading ENV sensor...

[SENSOR] Temp: 23.42°C, Humidity: 65.1%, Pressure: 1013.2 hPa

[STORE] Writing to flash: offset 74820, 12 bytes

[POWER] Active time: 423ms

[POWER] Estimated current draw: 45mA average

[SLEEP] Configuring next wake in 300 seconds

[SLEEP] Entering deep sleep... goodnight!

[Power Analysis]:

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Power Budget (5-minute interval) │

├──────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Deep sleep: 299.6s @ 10µA = 0.83 µAh │

│ Wake & sample: 0.4s @ 45mA = 5.00 µAh │

│ Total per cycle = 5.83 µAh │

│ Cycles per day (288) = 1.68 mAh/day │

│ 200mAh battery = 119 days!! │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────┘

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do battery-powered IoT devices run for months or years on tiny batteries?”

Before you write any code, sit with this question. A 200mAh battery at 50mA active current lasts 4 hours. Yet commercial sensors last years. The key is duty cycling—spending 99.9% of time in deep sleep drawing microamps, not milliamps. Every optimization matters: boot speed, sensor read time, WiFi connection time.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- ESP32 Power Domains

- What components are powered in each sleep mode?

- What’s the difference between light sleep and deep sleep?

- What is the ULP coprocessor and when would you use it?

- Book Reference: ESP32 Technical Reference Manual Ch. 29

- RTC Memory Persistence

- What is RTC_DATA_ATTR and how does it survive deep sleep?

- How much RTC memory is available?

- When is RTC memory erased (hint: reset button)?

- Book Reference: “Making Embedded Systems” Ch. 10 - Elecia White

- Wake Sources

- What can wake the ESP32 from deep sleep?

- How do you configure timer-based wake?

- How do you configure GPIO-based wake (button press)?

- Reference: ESP-IDF Deep Sleep documentation

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Wake Strategy

- Should you use ESP32’s internal timer or the BM8563 RTC?

- What if you want to wake on button press AND timer?

- How do you know WHY the device woke up?

- Data Storage

- How many readings can you store before running out of flash?

- How do you handle flash wear (limited write cycles)?

- When do you upload/clear stored data?

- Power Measurement

- How will you measure actual sleep current?

- What peripherals are you leaving powered accidentally?

- Is the display backlight fully off during sleep?

Thinking Exercise

Calculate Your Power Budget

Fill in this table for your design:

| Phase | Duration | Current | Charge Used |

|-----------------|----------|---------|-------------|

| Deep sleep | 299.5s | 10µA | ? |

| Boot/init | 0.3s | 50mA | ? |

| Sensor read | 0.1s | 30mA | ? |

| Flash write | 0.05s | 50mA | ? |

| Display update | 0.05s | 80mA | ? |

| TOTAL per cycle | | | ? |

Questions to calculate:

- Charge (µAh) = Current (µA) × Time (hours)

- How many cycles per day if you sample every 5 minutes?

- Total daily consumption in mAh?

- Days of operation from 200mAh battery?

- What dominates: sleep power or active power?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “Explain the different power modes of the ESP32 and when you’d use each.”

- “How would you measure the actual power consumption of an embedded device?”

- “What techniques would you use to minimize wake time in a battery-powered sensor?”

- “How does RTC memory differ from regular RAM? What survives deep sleep?”

- “Design a system that runs for 2 years on a CR2032 coin cell.”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start With Timer Wake

Use esp_sleep_enable_timer_wakeup(microseconds) to configure a timer wake. Start with 10 seconds to iterate quickly.

Hint 2: Preserve Data Across Sleep

Variables with RTC_DATA_ATTR survive deep sleep:

RTC_DATA_ATTR int bootCount = 0;

Use this for wake counts, accumulated data, etc.

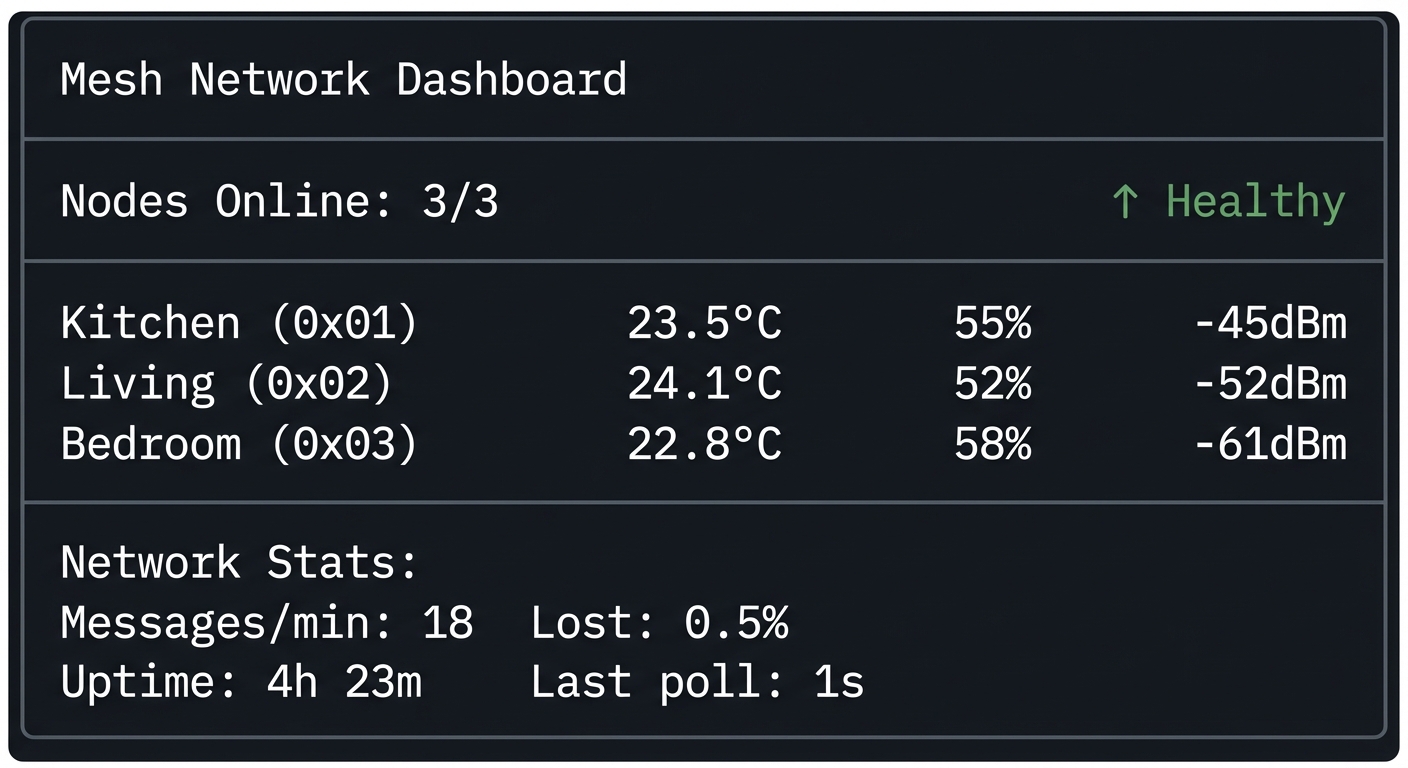

Hint 3: GPIO Wake for User Interaction