JIT Compilers - From Interpreter to Machine Code Master

Goal: Deeply understand the mechanics of Just-In-Time (JIT) compilation—how virtual machines like V8 and HotSpot observe running code, make daring gambles about future behavior, and transform generic bytecode into highly optimized, hardware-specific machine instructions. You will move from writing slow interpreters to building tiered execution engines that leverage speculative optimization and deoptimization.

Why JIT Compilers Matter

In the early days of computing, you had two choices: the raw speed of AOT (Ahead-of-Time) compiled languages like C, or the flexibility of Interpreted languages like BASIC. JIT compilation changed the world by offering the best of both: the developer experience of a dynamic language with performance that often rivals or even beats C.

- The V8 Revolution: Before V8, JavaScript was slow. By introducing aggressive JITing, Google turned the browser from a document viewer into a platform capable of running Photoshop and 3D games.

- The HotSpot Advantage: Java’s “Write Once, Run Anywhere” was made practical by HotSpot, which uses runtime profiling to optimize code for the specific CPU it’s currently running on—something AOT compilers struggle to do.

- The Modern Cloud: GraalVM and other modern JITs are now optimizing microservices, reducing memory footprints and “warm-up” times for serverless environments.

Why study JIT? Because it is the pinnacle of systems engineering. It combines compiler theory, operating system internals (memory management), and computer architecture (instruction sets) into a single, high-performance system.

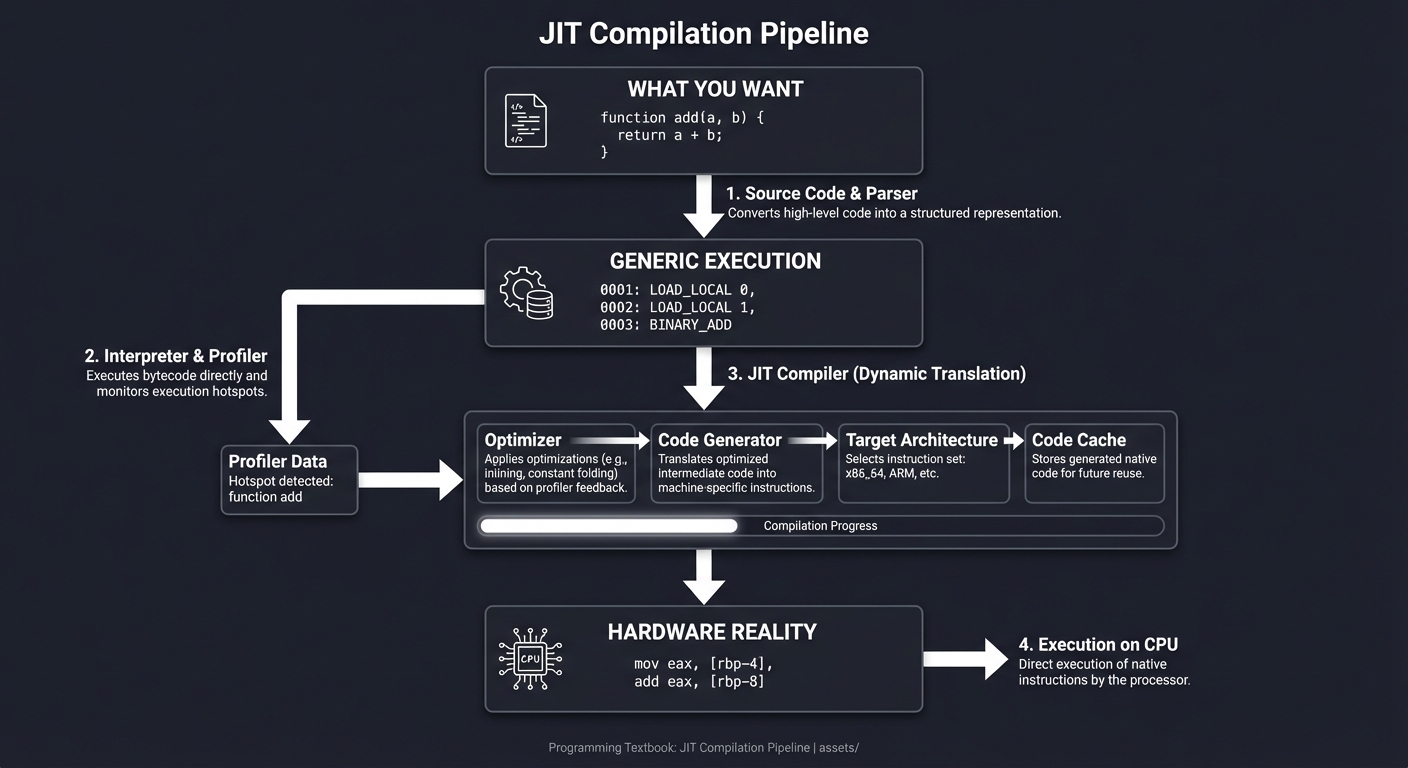

High-level code (JavaScript/Python) "What you want"

↓

function add(a, b) { return a + b; }

↓

Intermediate Bytecode "Generic execution"

↓

0001: LOAD_LOCAL 0

0002: LOAD_LOCAL 1

0003: BINARY_ADD

↓

Machine Code (x86_64/ARM) "Hardware reality"

↓

mov eax, [rbp-4]

add eax, [rbp-8]

Every Python script, every Java application, every Node.js server—underneath, it’s a JIT engine performing a high-wire act of optimization.

Core Concept Analysis

1. Virtual Memory: The JIT’s Playground

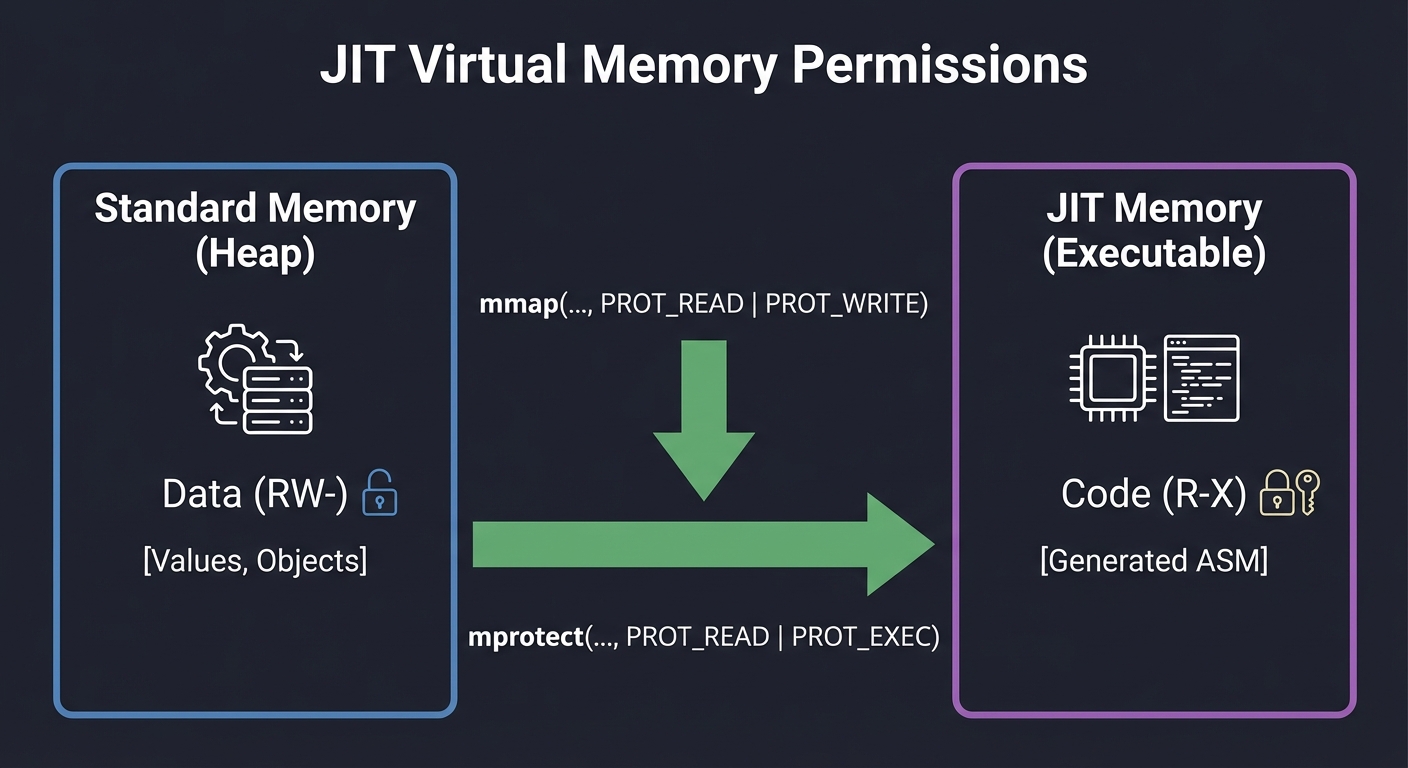

Before a JIT can execute code, it needs a place to put it. Normal memory allocated via malloc is usually marked as Data (Read/Write) but NOT Executable. To run code you’ve generated, you must talk to the OS kernel to change permissions.

Standard Memory (Heap) JIT Memory (Executable)

┌───────────────────────┐ ┌───────────────────────┐

│ Data (RW-) │ │ Code (R-X) │

│ [Values, Objects] │ │ [Generated ASM] │

└───────────────────────┘ └───────────────────────┘

↑ ↑

mmap(..., PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE) mprotect(..., PROT_READ | PROT_EXEC)

Key insight: Modern OSes enforce W^X (Write XOR Execute). This means a page can be writable or executable, but never both. A JIT must carefully transition pages between these states to prevent security vulnerabilities like buffer overflows being used to execute arbitrary code.

2. The Execution Spectrum & Tiered Compilation

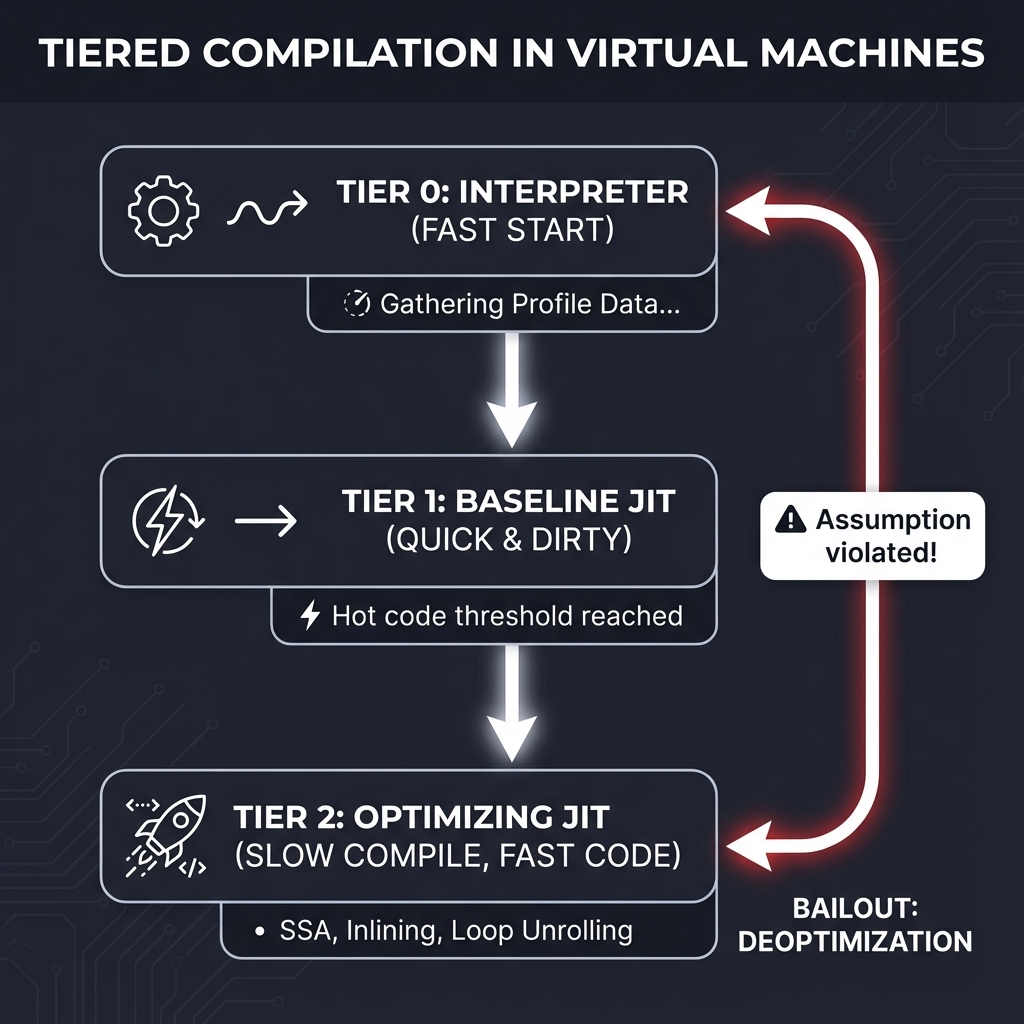

Modern VMs don’t just “compile everything.” Compilation is expensive in terms of time and memory. Instead, they use a “Tiered” approach, only spending heavy optimization effort on “Hot” code.

Tier 0: Interpreter (Fast Start)

│ Gathering Profile Data... "This loop has run 100 times!"

▼

Tier 1: Baseline/Template JIT (Quick & Dirty)

│ "This loop has run 10,000 times! Let's get serious."

▼

Tier 2: Optimizing JIT (Slow Compile, Fast Code)

│ SSA, Inlining, Loop Unrolling, Vectorization.

▼

Bailout: Deoptimization

"Wait! You said 'a' was an Integer, but now it's a String!"

--> Fall back to Tier 0.

The Trade-off:

- Interpreters start instantly but run slowly.

- Baseline JITs compile quickly (template stitching) for a moderate speedup.

- Optimizing JITs take a long time to analyze code but produce highly efficient machine instructions.

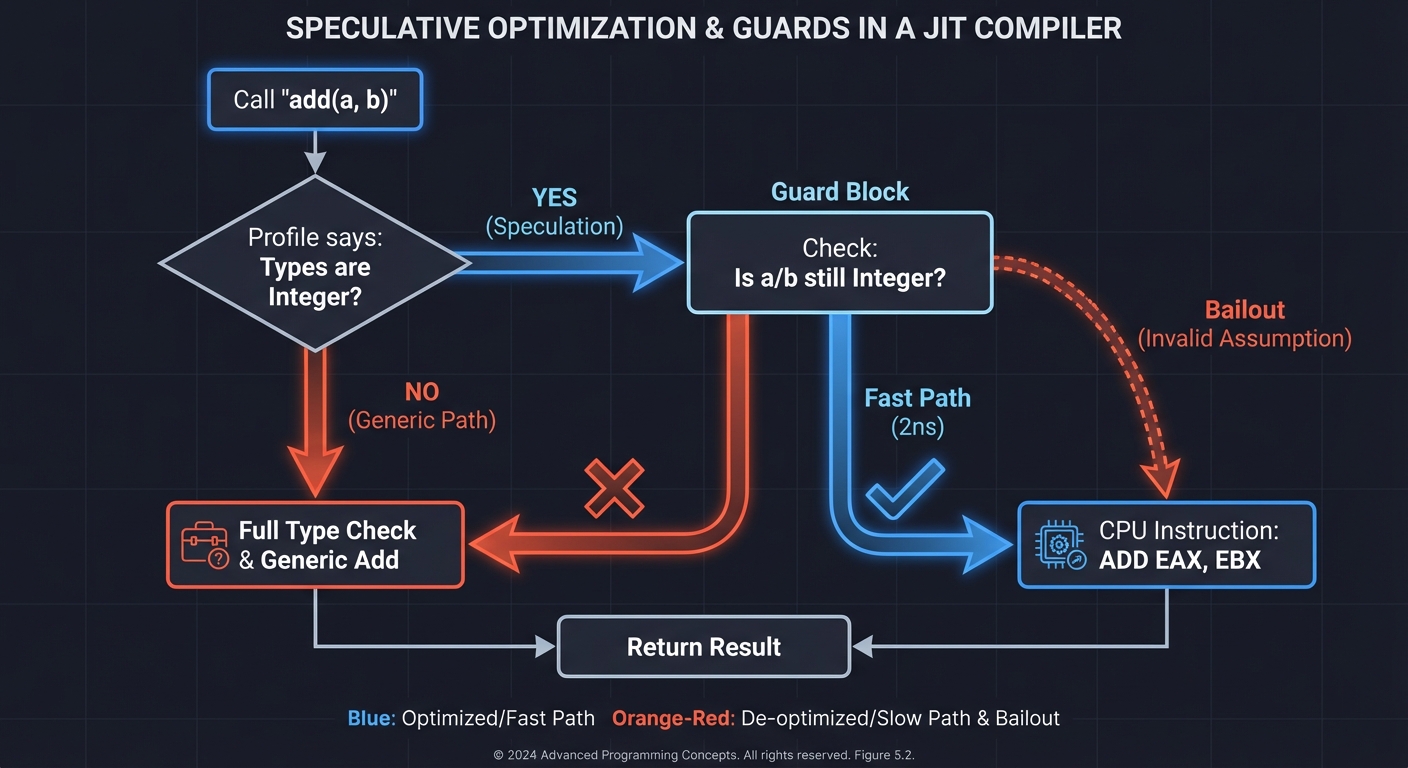

3. Speculative Optimization & The “Guard”

Dynamic languages (JS, Python) have a problem: you don’t know the types until you run the code. A JIT’s superpower is its ability to guess.

If a function add(a, b) has been called 10,000 times with integers, the JIT speculates it will always be integers. It compiles a version that skips all the complex type checks. However, it MUST include a Guard to handle the case where the guess is wrong.

// Optimized "Speculative" Code

if (!is_smi(a) || !is_smi(b)) {

goto deoptimize; // The "Guard"

}

return a + b; // Fast integer add - literally one CPU instruction

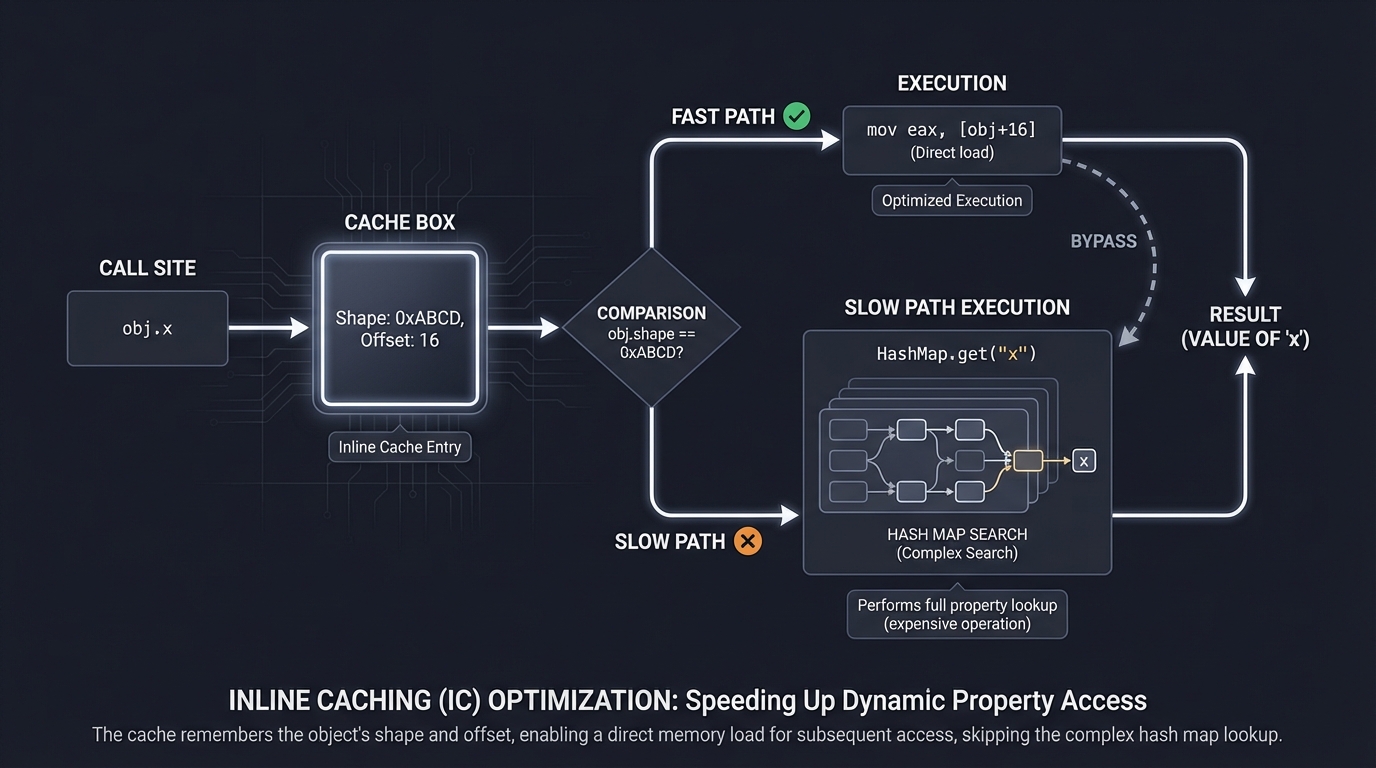

4. Inline Caching (IC): Mastering Dynamic Lookups

Property access like user.name is expensive in dynamic languages because objects are often hash maps. Finding name involves hashing and searching.

ICs speed this up by caching the memory offset of a property directly at the call site.

Call Site: get_name(user)

1st time: Search "name" in user. Found at offset 16.

Cache: "If object looks like 'user_shape', name is at 16."

2nd time: Check if object shape is 'user_shape'.

Yes? Directly read offset 16. (No search!)

5. Intermediate Representations (IR): SSA and Sea of Nodes

Compilers don’t optimize raw code. They translate it into an Intermediate Representation (IR).

- Bytecode: A simple, linear list of instructions for a virtual stack machine. Good for interpreters.

- SSA (Static Single Assignment): A representation where every variable is assigned exactly once. This makes “Data Flow Analysis” easy—you always know where a value came from.

- Sea of Nodes: An advanced IR used by V8 (TurboFan). It represents both data flow and control flow as a single giant graph. This allows the compiler to perform massive structural optimizations (like moving code out of loops) more easily.

6. Register Allocation: The Mapping Problem

Your CPU has a very small number of registers (e.g., 16 on x86_64). Your program might have hundreds of variables. Register Allocation is the art of deciding which variable gets to stay in a fast CPU register and which one gets “spilled” to the slow RAM (stack). JITs use “Linear Scan” allocation because it’s fast, while AOT compilers use “Graph Coloring” because it’s more optimal but slower.

7. On-Stack Replacement (OSR): Swapping Engines Mid-Flight

Imagine a function that is only called once, but it contains a loop that runs for a billion iterations. If you only compile on function entry, this loop will stay slow forever. OSR allows the VM to compile the hot loop while it is running, pause the interpreter, reconstruct the stack frame for the new JITed code, and “jump” into the middle of the running function. It’s like changing the tires of a car while it’s driving at 100mph.

Concept Summary Table

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize |

|---|---|

| Executable Memory | Memory permissions (RWX). How mmap and mprotect enable dynamic execution while respecting W^X. |

| Interpreter vs JIT | The trade-off between startup latency and peak performance. The “Warm-up” period. |

| Speculative Guards | Performance comes from assumptions. Every assumption must have a safety check (Guard). |

| Deoptimization | The complex mechanism to undo optimizations and restore interpreter state when assumptions fail. |

| Inline Caches (IC) | Turning dynamic lookups into constant-time memory accesses via call-site caching. |

| Hidden Classes/Shapes | Using internal structs (Maps) to give dynamic objects a predictable, C-struct-like memory layout. |

| SSA / Sea of Nodes | Advanced intermediate representations (IR) used to perform mathematical and structural optimizations. |

Deep Dive Reading by Concept

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| VM Foundations | Virtual Machines (Smith/Nair) — Ch. 1: “Introduction to Virtual Machines” |

| Dynamic Translation | Virtual Machines (Smith/Nair) — Ch. 3: “Dynamic Binary Optimization” |

| Compiler Optimization | Compilers: Principles, Techniques, and Tools (Dragon Book) — Ch. 8: “Code Generation” & Ch. 9: “Machine-Independent Optimizations” |

| SSA & IR Design | Engineering a Compiler (Cooper/Torczon) — Ch. 5: “Intermediate Representations” & Ch. 9: “SSA Form” |

| Register Allocation | Engineering a Compiler (Cooper/Torczon) — Ch. 13: “Register Allocation” |

| JVM Internals & JIT | Java Performance: The Definitive Guide (Scott Oaks) — Ch. 4: “Working with the JIT Compiler” |

| Modern VM Techniques | Optimizing Java (Evans/Gough/Newland) — Ch. 5: “Microbenchmarking and the JIT” & Ch. 11: “Java Language Performance Techniques” |

| Hardware Interaction | Inside the Machine (Jon Stokes) — Ch. 5: “Pentium Pro & Pentium II” |

| Security & Memory | How Linux Works (Brian Ward) — Ch. 17: “Introduction to Security” |

| V8 Internal Design | V8 Blog — “TurboFan: A new compiler architecture for V8” |

Project Comparison Table

| Project | Difficulty | Time | Depth of Understanding | Fun Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Bytecode Profiler | Level 1 | Weekend | ★★☆☆☆ | ★★★☆☆ |

| 2. Template JIT | Level 2 | 1 Week | ★★★☆☆ | ★★★★☆ |

| 3. Monomorphic IC | Level 3 | 1 Week | ★★★★☆ | ★★★★☆ |

| 4. Speculative Optimization | Level 3 | 1 Week | ★★★★☆ | ★★★★★ |

| 5. Deoptimization Guard | Level 4 | 2 Weeks | ★★★★★ | ★★★★☆ |

| 6. Polymorphic IC | Level 3 | 1 Week | ★★★★☆ | ★★★☆☆ |

| 7. Inlining Engine | Level 3 | 1 Week | ★★★☆☆ | ★★★☆☆ |

| 8. Register Allocation | Level 4 | 2 Weeks | ★★★★☆ | ★★☆☆☆ |

| 9. Escape Analysis | Level 4 | 2 Weeks | ★★★★☆ | ★★★☆☆ |

| 10. Sea of Nodes Viz | Level 3 | 2 Weeks | ★★★☆☆ | ★★★★★ |

| 11. Tiered Comp Manager | Level 3 | 1 Week | ★★★☆☆ | ★★★☆☆ |

| 12. Hidden Classes | Level 4 | 2 Weeks | ★★★★★ | ★★★★☆ |

| 13. LICM Optimization | Level 3 | 1 Week | ★★★★☆ | ★★★☆☆ |

| 14. On-Stack Replacement | Level 5 | 1 Month | ★★★★★ | ★★★★★ |

| 15. Write Barrier | Level 4 | 2 Weeks | ★★★★☆ | ★★☆☆☆ |

Detailed Project Guides

Project 1: Bytecode Profiler

Build a “Heat Map” for your bytecode execution engine. You will track which instructions are executed most frequently and identify “Hot” functions. This is the foundation of every tiered JIT.

Real World Outcome

When you run your VM with the --profile flag, it won’t just run the code; it will perform a deep audit of its own execution. You’ll see a terminal output that identifies the exact bottlenecks in your high-level code. For a recursive Fibonacci script, you’ll see the exponential explosion of calls and the “Hot” instructions where the CPU is spending most of its time.

$ ./vm --profile examples/fibonacci.bc

[Bytecode Execution Profile]

--------------------------------------------------

Duration: 1.2s | Total Instructions: 8,421,005

--------------------------------------------------

TOP HOT FUNCTIONS:

1. fib(n) : 1,213,902 calls [Threshold reached at 0.05s]

2. <global_scope> : 1 call [Cold]

INSTRUCTION HEAT MAP (PC | Opcode | Frequency):

0x00A1 | BINARY_SUB | ████████████████████ 2,427,804

0x00A4 | CALL | ██████████ 1,213,901

0x008F | LOAD_LOCAL | ██████████ 1,213,901

0x00A8 | BINARY_ADD | ██████ 606,950

OPTIMIZATION ADVISORY:

Function 'fib' is a candidate for promotion to Tier 1 (Baseline JIT).

Triggering event: Backward jump counter exceeded 5,000 in loop at 0x00B2.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How does a VM ‘know’ when code is worth the cost of compilation? How can we measure heat without the measurement itself slowing down the program?”

Before coding, realize that every if(counter++) check you add to your interpreter loop makes the interpreter slower. Production VMs use “sampling” or “low-overhead counters” to solve this.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- The Fetch-Decode-Execute Loop: The heart of an interpreter.

- Basic Blocks: Sequences of code with one entry and one exit—the units of JIT compilation.

- Back-Edge Counting: Why we count backward jumps (loops) differently than forward jumps.

- Sampling vs. Instrumentation: The trade-off between accuracy and performance.

- Book Reference: “Optimizing Java” Ch. 5 - Evans/Gough/Newland

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Counter Storage: Should you store counters in the

Functionobject or a dedicatedProfilerhash map? - Decay: Should “Heat” cool down over time? If a function was hot an hour ago but isn’t now, should it stay optimized?

- Thresholding: What is the “Magic Number” of executions that warrants JIT compilation? (V8 uses different numbers for different tiers).

- Wait-Time: How do you handle “OSR” (On-Stack Replacement) where a function is only called once but contains a loop that runs a million times?

Thinking Exercise

Draw the Control Flow Graph (CFG) of a while loop. Mark the “Back-Edge” (the jump that goes from the end of the loop back to the beginning). If you only increment your counter on this one instruction, how does that change your “Heat” calculation compared to incrementing on every instruction?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “Why do we count backward jumps separately from function entries?”

- “How does profiling overhead impact the ‘Heisenberg effect’ in performance measurement?”

- “What is a ‘Call Graph’ and how is it used in JIT optimization?”

Hints in Layers

- Hint 1: Simple Counters: Add an

int call_countto yourFunctionmetadata and auint64_t* instr_countsarray to your VM state. - Hint 2: The Loop Trigger: Inside your

JUMP_BACKinstruction handler, increment the counter for the current function. Check if it hits 1000. - Hint 3: Visualizing: Use ASCII bars (like the bash example) to show the relative frequency. It makes bottlenecks instantly obvious.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| VM Profiling | “Virtual Machines” (Smith/Nair) | Ch. 2 |

| JIT Thresholds | “Java Performance” (Scott Oaks) | Ch. 4 |

| Interpreter Internals | “Crafting Interpreters” | Ch. 15 |

Project 2: Template JIT

The “Hello World” of JIT compilers. You will generate raw machine code by “stitching” together pre-compiled snippets of assembly, bypassing the slow interpreter loop.

Real World Outcome

You will input a simple math expression, and your program will output the raw hex bytes it generated in memory, then execute those bytes directly on your CPU. You’ll see your code literally “writing code” and then running it.

$ ./template_jit "return 10 + 20"

[1] Allocating Executable Memory (mmap)... [SUCCESS] -> 0x7f001234

[2] Translating Bytecode to Machine Code...

- OP_CONST 10 => 48 c7 c0 0a 00 00 00 (MOV RAX, 10)

- OP_CONST 20 => 48 c7 c1 14 00 00 00 (MOV RCX, 20)

- OP_ADD => 48 01 c8 (ADD RAX, RCX)

- OP_RET => c3 (RET)

[3] Setting Memory to READ|EXECUTE... [SUCCESS]

[4] Calling generated function at 0x7f001234...

Result: 30

# Congratulations: You just bypassed the C compiler and talked to the CPU directly!

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do I turn an array of bytes into a function my CPU can actually run? How do I cross the bridge from ‘Data’ to ‘Code’?”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Instruction Set Architecture (ISA): Understanding that

0xC3meansRETon x86 but something else on ARM. - Calling Conventions (ABI): In Linux x86_64, which register holds the return value? (

RAX). - Memory Pages: Why you can’t just execute code on the stack or standard heap (NX bit).

- mmap & mprotect: The system calls that negotiate with the Kernel for executable permissions.

- Book Reference: “The Linux Programming Interface” Ch. 49 & 50

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Snippet Storage: Where will you get the machine code bytes from? (Manual hex coding vs. using an assembler library like

AsmJitorZydis). - Registers: How will you map your VM’s “Virtual Registers” to the CPU’s “Physical Registers”?

- Instruction Cache: Why do you need to flush the I-Cache on ARM/M1 Mac after writing code, but not usually on x86?

- Error Handling: What happens if your generated machine code crashes? (Segmention Fault). How do you debug a JIT?

Thinking Exercise

Use objdump -d on a simple C program. Find the bytes for a function that returns the number 42. Now, write a C program that uses mmap to allocate 4096 bytes, copies those bytes into the buffer, and calls it. If it fails, check your mprotect flags.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is the role of the Instruction Cache (I-Cache) in a JIT?”

- “Explain W^X (Write XOR Execute) and why it’s a security feature.”

- “How does a JIT handle different CPU architectures (x86 vs ARM)?”

Hints in Layers

- Hint 1: The Return: Start with a JIT that only returns a constant. Bytes:

48 c7 c0 2a 00 00 00 c3(MOV RAX, 42; RET). - Hint 2: mmap: Use

mmap(NULL, size, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_ANONYMOUS|MAP_PRIVATE, -1, 0). - Hint 3: Execution: Cast the address to a function pointer:

int (*func)() = (int(*)())ptr;.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| x86-64 Assembly | “Modern X86 Assembly Language Programming” | Ch. 1-3 |

| System Programming | “How Linux Works” | Ch. 5 (Processes/Memory) |

| JIT Basics | “Virtual Machines” (Smith/Nair) | Ch. 4 |

Project 3: Monomorphic IC (Inline Cache)

Speed up property access by caching the results of dynamic lookups directly at the call site. You will turn a slow hash map search into a fast memory comparison and load.

Real World Outcome

You will run a script that accesses properties of an object inside a loop (e.g., for i: obj.x + 1). With IC enabled, you will see the execution time drop by 5-10x. The “Cache Hit” logs will show that the VM is bypassing the hash table entirely.

$ ./vm --ic-stats examples/loop_access.bc

[IC Stats]

Call Site 0x00B2 (GET_PROP 'x'):

- State: MONOMORPHIC

- Cached Shape: 0xDEADBEEF

- Cached Offset: 16 bytes

- Hits: 1,000,000

- Misses: 1 (initial warmup)

Execution Time (No IC): 450ms

Execution Time (With IC): 42ms

# Speedup: 10.7x

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do dynamic languages achieve the speed of C structs when their objects are actually just hash maps?”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Object Shapes / Hidden Classes: How to identify if two objects have the same layout.

- Call Sites: The specific location in the bytecode where a property is accessed.

- Monomorphic vs. Polymorphic: Handling the case where a call site sees one type vs. many types.

- Self-Modifying Code: How JITs “patch” call sites with new instructions or data.

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Storage: Where do you store the cached shape and offset? (Inside the bytecode stream? In a side-table?)

- Validation: How do you quickly check if the incoming object matches the cached shape?

- Invalidation: What happens if the object’s layout changes (e.g., adding a new property)?

- Tiering: How does a Monomorphic IC transition to a Polymorphic IC when it sees a second type?

Thinking Exercise

Imagine a Point class. Every instance has x and y.

p1 = {x: 1, y: 2} and p2 = {x: 10, y: 20}.

They share the same “Shape” (x at 0, y at 8).

Now consider p3 = {y: 5, x: 3}. Does it have the same shape? (Hint: Order matters in memory!)

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What is a ‘Megamorphic’ call site and why is it a performance killer?”

- “How do V8’s Inline Caches relate to the concept of ‘Shapes’ or ‘Maps’?”

- “Why is it better to have Monomorphic call sites in your JavaScript code?”

Hints in Layers

- Hint 1: The Shape: Give every object a

ShapeID. If two objects have the same properties in the same order, they get the sameShapeID. - Hint 2: The Cache: Create a struct

ICSlot { uint32_t expected_shape; uint32_t offset; }. - Hint 3: The Patch: During the first execution, do the slow lookup, then save the result in the

ICSlot. On the next execution, checkif (obj->shape == slot->expected_shape) return obj->data[slot->offset].

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Inline Caching Theory | “Virtual Machines” (Smith/Nair) | Ch. 6 |

| V8 Implementation | “Optimizing Java” | Ch. 11 |

| Dynamic Dispatch | “Compilers: Principles, Techniques, and Tools” | Ch. 7 |

Project 12: Hidden Classes (Shapes)

Implement V8-style hidden classes to track the evolution of dynamic objects. You will build a “Transition Tree” that maps property additions to specific memory layouts.

Real World Outcome

You will implement an object system where adding properties a, then b, then c creates a chain of hidden classes. You’ll be able to dump the transition tree and see how the VM “learns” the structure of your objects.

$ ./vm --dump-shapes examples/objects.bc

[Hidden Class Transition Tree]

Root (Empty) [ID: 0]

└── + "name" ──▶ Shape [ID: 1] { name: offset 0 }

└── + "age" ──▶ Shape [ID: 2] { name: offset 0, age: offset 8 }

└── + "city" ──▶ Shape [ID: 3] { name: offset 0, age: offset 8, city: offset 16 }

Object Instances:

user1 (Shape 3): [ "Alice", 30, "London" ]

user2 (Shape 3): [ "Bob", 25, "Paris" ]

# Look! user1 and user2 share the exact same memory layout. No more string keys!

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How can we give a dynamic language the memory efficiency and predictable layout of a C

struct?”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Memory Layout: Offsets, alignment, and word sizes.

- Transitions: The path an object takes as it grows (e.g.,

Shape0 + "x" -> Shape1). - Back-pointers: How a hidden class knows where it came from.

- Property Slots: Storing data in a flat array (the “Properties Backing Store”) instead of a dictionary.

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Shape Uniqueness: How do you ensure that

p1 = {x, y}andp2 = {x, y}end up with the same Shape ID? - Divergence: What happens if one code path adds

xtheny, but another addsythenx? (Hint: They result in different shapes!). - Deletes: How do you handle

delete obj.prop? (Most JITs “bail out” to a dictionary mode). - Prototype Chain: How do hidden classes interact with inheritance?

Thinking Exercise

Trace this code:

obj = {}; // Shape A

obj.x = 1; // Shape A -> Shape B (+x)

obj.y = 2; // Shape B -> Shape C (+y)

delete obj.x; // What happens now?

Should you create a “Shape D” for {y}? Or should you just turn the object into a hash map? Research why V8 chooses “Dictionary Mode” for deleted properties.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “Why does the order of property initialization matter for performance in V8?”

- “How do Hidden Classes enable fast Inline Caching?”

- “What is the difference between ‘In-object properties’ and ‘Backing store properties’?”

Hints in Layers

- Hint 1: The Map: Every object should have a

hidden_classpointer. The hidden class contains a hash map ofPropertyName -> (Offset, NextShape). - Hint 2: Transitions: When a property is added, check if the current

hidden_classalready has a transition for that name. If yes, move toNextShape. If no, create a new one. - Hint 3: Sharing: Use a “Global Transition Table” to ensure that identical transitions result in the same shape.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Hidden Classes in V8 | “V8 Design Docs” (Online) | “Hidden Classes” |

| Object Layouts | “Virtual Machines” (Smith/Nair) | Ch. 6 |

| Efficient Data Rep | “Expert C Programming” | Ch. 3 (Memory layout) |

Final Overall Project: “The Mini-V8”

- Main Programming Language: C++

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust

- Coolness Level: Level 5: Pure Magic (Super Cool)

- Business Potential: 5. The “Industry Disruptor”

- Difficulty: Level 5: Master

- Knowledge Area: Full System Integration

- Software or Tool: Custom Language Implementation

Project Description

Build a complete, high-performance execution engine for a small dynamic language. It will feature:

- Tiered Execution: Starts in a bytecode interpreter, promotes to a Template JIT, then to an Optimizing JIT.

- Hidden Classes: V8-style object maps for fast property access.

- Speculative Optimization: Assumes types based on profile data.

- Full Deoptimization: Can bail out from optimized code at any point.

- OSR: Can promote hot loops while they are running.

Real World Outcome

You will run a benchmark program that performs complex object manipulations and mathematical loops. You will witness the execution speed jump by 10-50x as the JIT tiers kick in.

$ ./mini_v8 benchmark.js

[Tier 0] Starting Interpreter...

[Tier 0] Cycle 1000: 'compute_sum' is hot. Compiling to Baseline JIT...

[Tier 1] 'compute_sum' promoted to Baseline JIT (Address: 0x9000).

[Tier 1] Performance Increase: 4.2x

[Tier 1] Cycle 10000: 'compute_sum' is smoking. Compiling to Optimizing JIT (SSA)...

[Tier 2] Optimizing 'compute_sum': Inlining 'add', Constant Folding, Speculating Smi.

[Tier 2] 'compute_sum' promoted to Optimizing JIT (Address: 0xA000).

[Tier 2] Performance Increase: 28.5x

[Trigger] Calling 'compute_sum' with a String instead of Int...

[Bailout] GUARD_FAILED in 'compute_sum' at 0xA042.

[Bailout] Deoptimizing... Restoring stack frames...

[Tier 0] Resuming execution in Interpreter.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do the world’s fastest virtual machines balance the cost of compilation with the speed of execution, and how do they remain safe while making aggressive guesses?”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Hidden Classes (Maps/Shapes): How to represent dynamic objects as fixed offsets.

- SSA (Static Single Assignment): The intermediate representation needed for powerful optimizations like LICM.

- Stack Frame Reconstruction: How to move from an optimized machine code frame back to an interpreter frame (The hardest part!).

- Guard Chains: How to string together type checks and branch to deoptimization targets.

- Inline Caching (Monomorphic, Polymorphic): Managing call site caches.

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Promotion Strategy: When exactly do you promote? Too early and you waste time compiling code that won’t run long. Too late and you lose potential speed.

- Object Layout: How do hidden classes transition? (e.g.,

obj.a = 1creates Class1, thenobj.b = 2creates Class2 with a transition from Class1). - Deoptimization Points: Where can you deoptimize? Usually at every “Guard” or “Side Effect” (like a function call).

- Register Mapping: How do you map machine registers back to the interpreter’s virtual registers during deoptimization?

Thinking Exercise

Imagine an optimized function has “inlined” three other functions. If a deoptimization occurs in the deepest inlined function, your “Deoptimizer” must recreate THREE interpreter stack frames from the single machine code frame. Draw a diagram of how you would store the “Metadata” (debug info) needed to perform this reconstruction.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “Explain how V8’s Hidden Classes make JavaScript property access fast.”

- “What is On-Stack Replacement (OSR) and why is it necessary for long-running loops?”

- “Why is deoptimization considered the ‘safety valve’ of a JIT?”

- “What are the trade-offs of using a Sea of Nodes IR vs a traditional linear SSA IR?”

Hints in Layers

- Hint 1: The Metadata: Every optimized code block needs a “Side Table” that maps instruction offsets to Bytecode offsets and Register maps.

- Hint 2: The Deoptimizer: This is a piece of assembly code that saves all registers, looks up the metadata for the current PC, and pushes the correct values onto the stack to match what the interpreter expects.

- Hint 3: Hidden Classes: Start with a global “Class Table”. Each object has a pointer to its Class. When a property is added, find or create the next Class in the transition tree.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| SSA & Advanced Optimization | “Compilers: Principles, Techniques, and Tools” | Ch. 9 |

| V8 / HotSpot Architecture | “Virtual Machines” (Smith/Nair) | Ch. 6 |

| JIT Implementation | “Optimizing Java” (Evans/Gough/Newland) | Ch. 11-12 |

| SSA Form | “Engineering a Compiler” (Cooper/Torczon) | Ch. 9 |

Summary

This learning path covers JIT compilation through 15 hands-on projects. Here’s the complete list:

| # | Project Name | Main Language | Difficulty | Time Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bytecode Profiler | C/C++ | Beginner | Weekend |

| 2 | Template JIT | C/C++ | Intermediate | 1 Week |

| 3 | Monomorphic IC | C++ | Advanced | 1-2 Weeks |

| 4 | Speculative Integer Opt | C/C++ | Advanced | 1 Week |

| 5 | Deoptimization Guard | C++ | Expert | 2 Weeks |

| 6 | Polymorphic IC | C++ | Advanced | 1 Week |

| 7 | Inlining Engine | C++ | Advanced | 1 Week |

| 8 | Register Allocation | C/C++ | Expert | 2 Weeks |

| 9 | Escape Analysis | C++/Java | Expert | 2 Weeks |

| 10 | Sea of Nodes Viz | TS/C++ | Advanced | 1-2 Weeks |

| 11 | Tiered Comp Manager | C++/Java | Advanced | 1-2 Weeks |

| 12 | Hidden Classes | C++/Rust | Expert | 2 Weeks |

| 13 | LICM Optimization | C++/Rust | Advanced | 1 Week |

| 14 | On-Stack Replacement | C/C++ | Master | 1 Month |

| 15 | Write Barrier | C++ | Expert | 2 Weeks |

Recommended Learning Path

For beginners: Start with projects #1, #2, #3, and #7. For intermediate: Jump to projects #4, #5, #6, #11, and #12. For advanced: Focus on projects #8, #9, #10, #14, and #15.

Expected Outcomes

After completing these projects, you will:

- Understand exactly how

mmapand executable memory work. - Be able to read and explain V8 or HotSpot source code.

- Understand the trade-offs between different IRs (Bytecode vs SSA vs Sea of Nodes).

- Master the art of speculative execution and the safety of deoptimization.

- Have a deep, intuitive grasp of how dynamic languages achieve hardware-level performance.

You’ll have built 15 working projects that demonstrate deep understanding of JIT compilation from first principles.