Learn GNU Tools: From User to Builder

Goal: Deeply understand the GNU tools and Unix philosophy by building your own versions from scratch. You will move from being a user of

ls,grep,make, andshto understanding their internal mechanics: syscalls, file descriptors, directory metadata, process control, and build automation. By the end, you can design your own command-line utilities, debug them like a systems programmer, and reason about performance and correctness at the byte and syscall level.

Why GNU Tools Matter

GNU tools are the invisible backbone of development on Unix-like systems. They compile your code, search logs, stitch pipelines together, and automate builds. Most developers use them without ever seeing the machinery behind them. That is the gap this guide closes.

Consider the difference between these two developers:

- One only knows the command line by memory: if something fails, they retry with different flags.

- The other understands what each tool is doing to the filesystem, what syscalls are issued, and how the kernel responds.

The second developer can debug odd failures quickly, build reliable automation, and reason about performance trade-offs that are otherwise invisible.

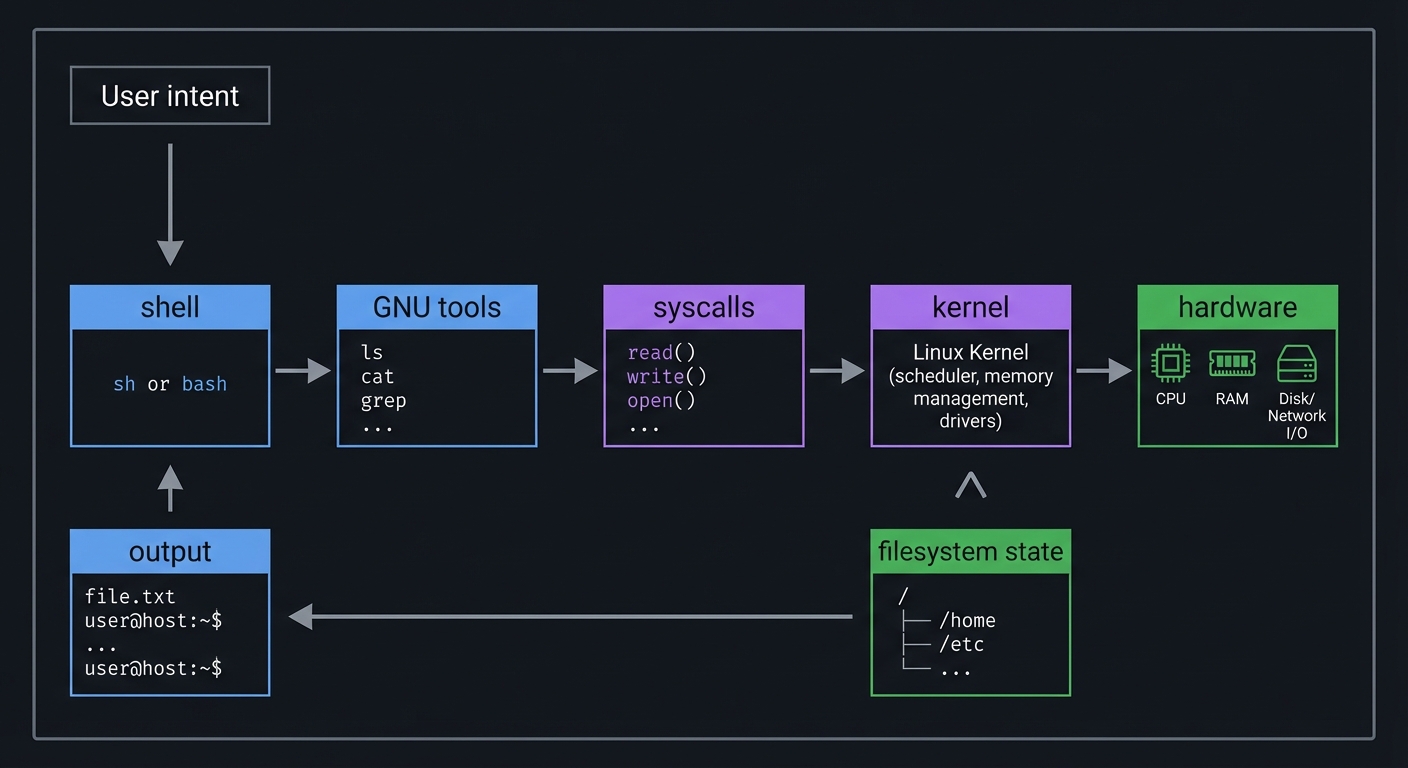

User intent

|

v

shell -> GNU tools -> syscalls -> kernel -> hardware

^ |

| v

output <---------- filesystem state

The core truth: GNU tools are small, composable programs that speak a consistent stream interface. Once you understand that model, you can build tools that behave like native Unix utilities and plug into existing pipelines cleanly.

Prerequisites & Background Knowledge

Essential Prerequisites (Must Have)

- Basic C syntax, functions, loops, and pointers

- Comfort with the command line and basic shell usage

- Familiarity with compiling C (

gcc,clang,make)

Helpful But Not Required

- Understanding of POSIX APIs and man pages

- Exposure to

fork,exec, and file descriptors - Basic regular expression knowledge

Self-Assessment Questions

- Can you open, read, and write files in C without looking up every call?

- Do you understand what stdin/stdout/stderr are?

- Can you explain the difference between

fread()andread()? - Have you used

ls -l,grep, and pipes (|) before? - Do you know how to compile and run C programs from the command line?

Development Environment Setup

- Linux or macOS (Linux preferred for full GNU parity)

- Compiler:

gccorclang - Make: GNU Make (

make) - Debugger:

gdborlldb - Optional:

strace/dtrussto observe syscalls

Time Investment

- 6 small projects + 1 capstone

- Estimate: 6-10 weeks if you do the full depth

Important Reality Check

These projects are not about copying the GNU codebase. They are about learning how the concepts work by rebuilding them in a minimal form. You are building models of the tools, not full reimplementations.

Core Concept Analysis

Think of the GNU tools as a network of small stream processors. Every project in this guide makes one part of that network visible and concrete.

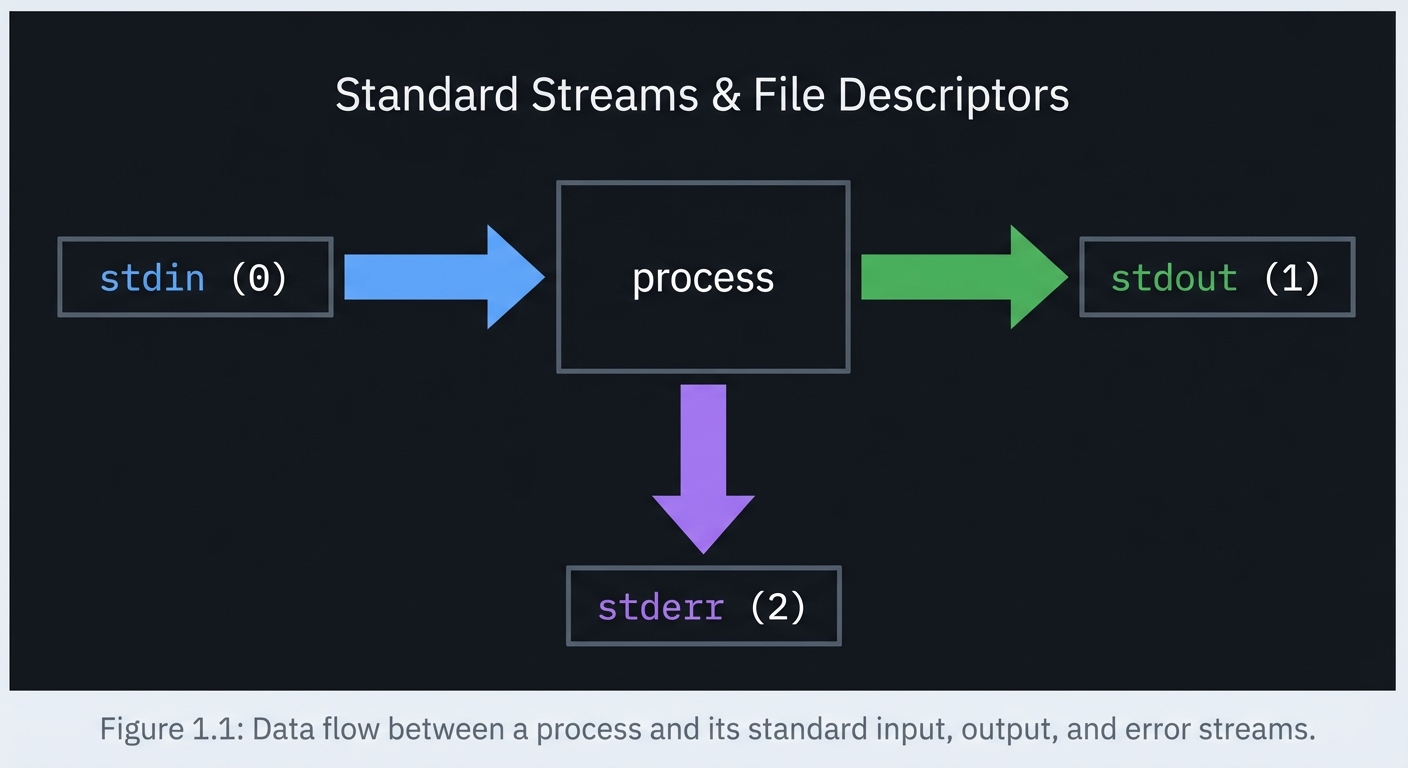

1) Streams, File Descriptors, and Exit Codes

Definition: A file descriptor (FD) is just a small integer that refers to an open file, pipe, or device. stdin is FD 0, stdout is FD 1, and stderr is FD 2.

stdin (0) -> [ process ] -> stdout (1)

|

+------> stderr (2)

Key ideas:

- Redirection rewires FDs (

>,<,2>) - Pipes connect stdout to stdin (

|) - Exit codes are the contract of success/failure in pipelines

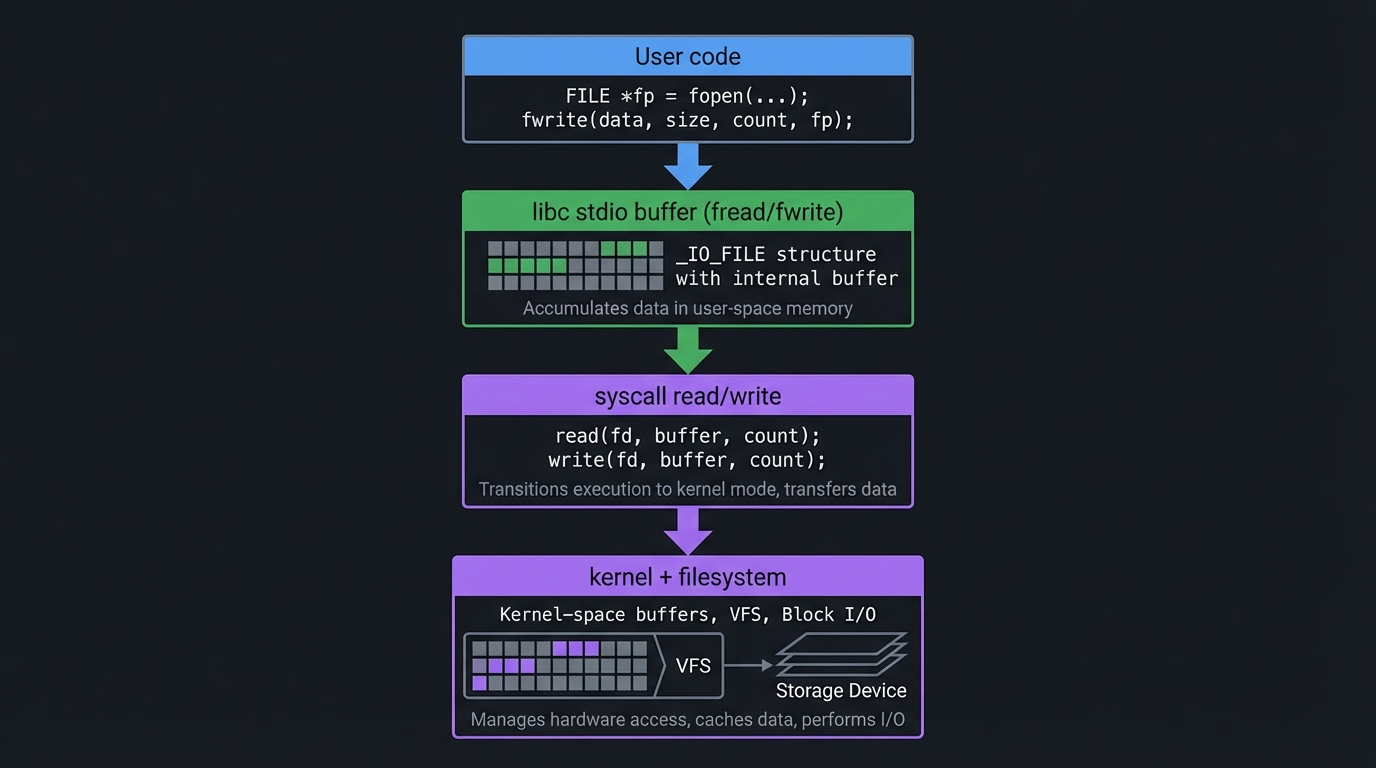

2) Buffering vs Syscalls

Definition: stdio functions like fread() buffer user-space data, while syscalls like read() operate directly on kernel-managed buffers.

User code

|

v

libc stdio buffer (fread/fwrite)

|

v

syscall read/write

|

v

kernel + filesystem

Key ideas:

- Small reads/writes are slow without buffering

- Buffering changes when data becomes visible (flush on newline, buffer full, or

fflush)

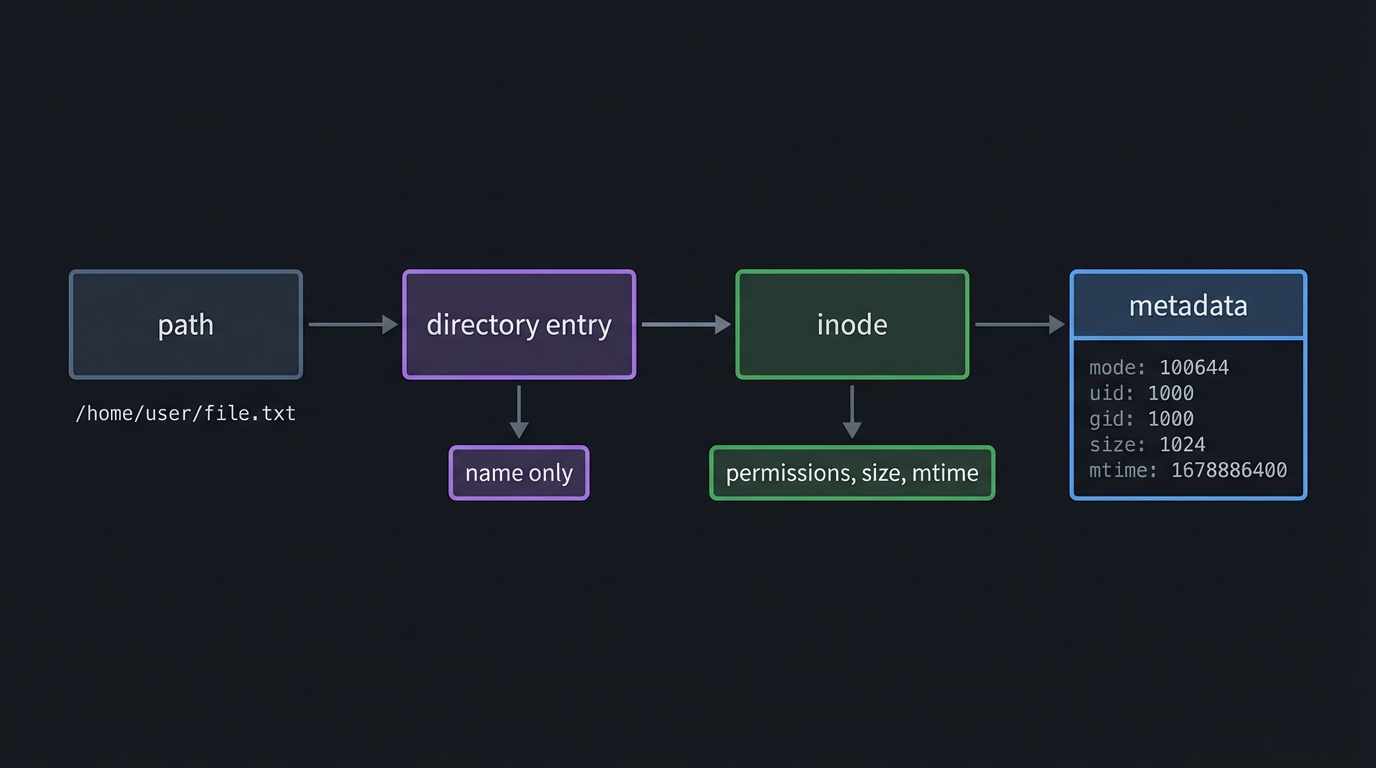

3) Filesystem Metadata and Inodes

Definition: A filename is just a directory entry that points to an inode; the inode holds the true metadata.

path -> directory entry -> inode -> metadata

| |

| +-- permissions, size, mtime

+-- name only

Key ideas:

stat()gives you the truth about a file, not just its namels -lis mostly a metadata formatter

4) Text Processing as State Machines

Definition: Most text tools implement a state machine that transforms a stream into new output.

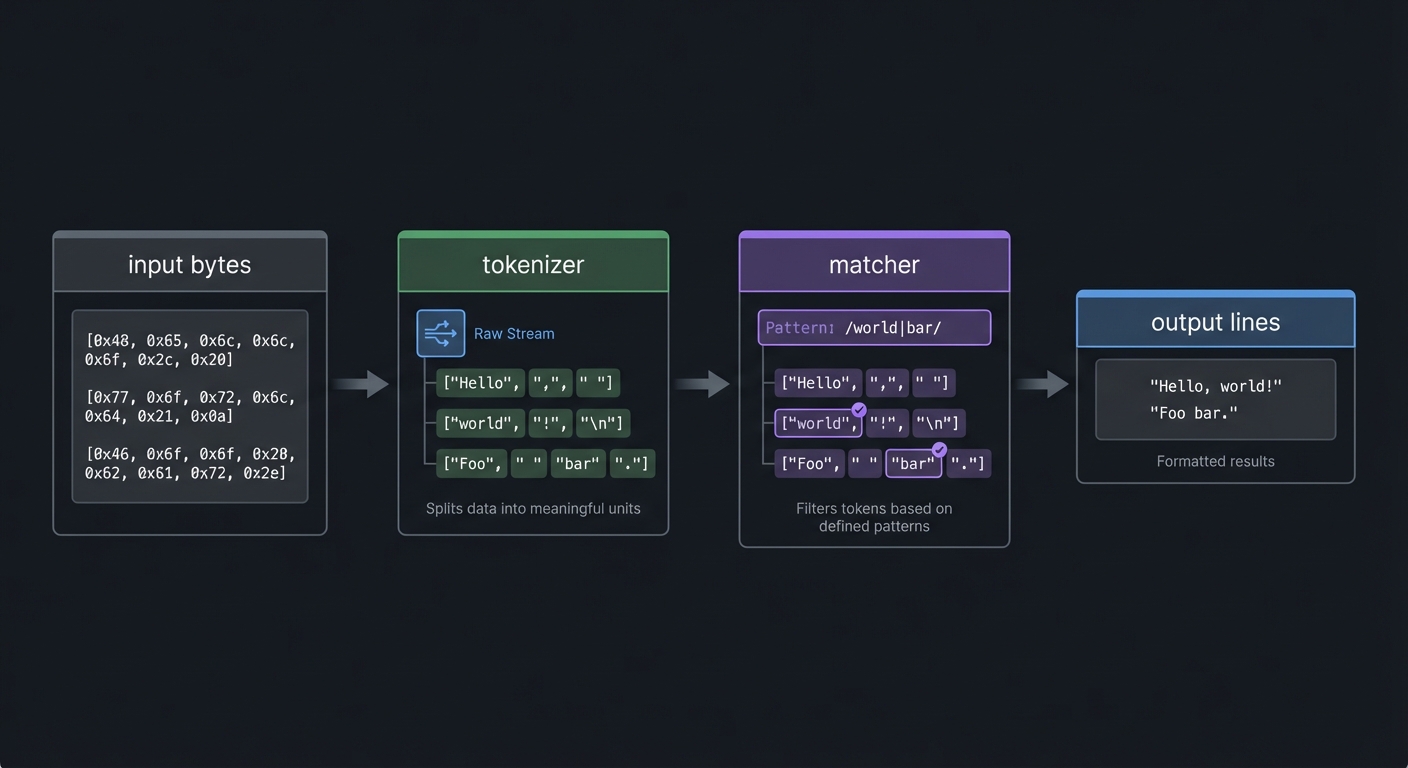

input bytes -> tokenizer -> matcher -> output lines

Key ideas:

wccounts transitionsgreptests predicates per line- A simple loop can be a powerful stream processor

5) Process Creation and Program Replacement

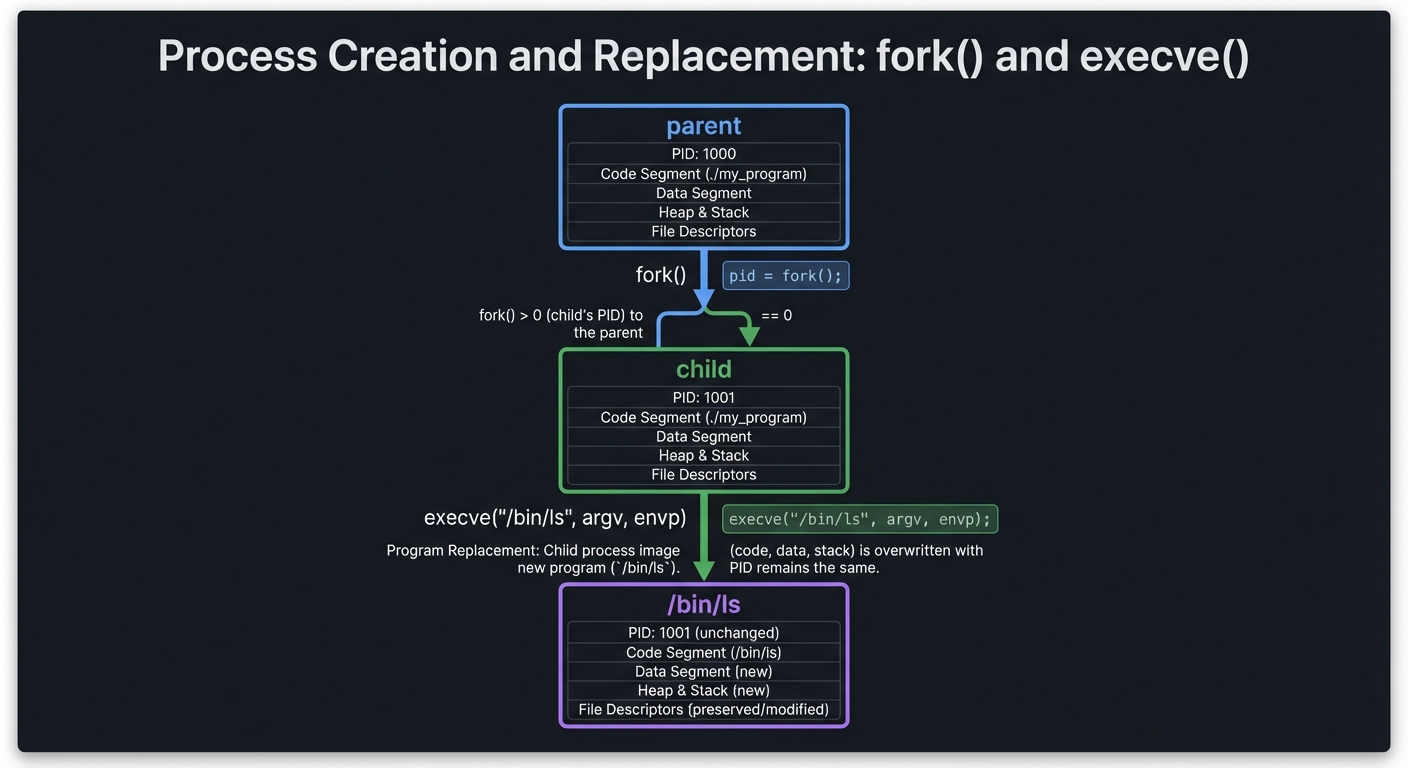

Definition: fork() clones a process. exec() replaces the child process with a new program.

parent

|

+-- fork() -> child

|

+-- execve("/bin/ls", argv, envp)

Key ideas:

- The parent controls synchronization with

wait() - The child inherits file descriptors

6) Pipes, Redirection, and Shell Parsing

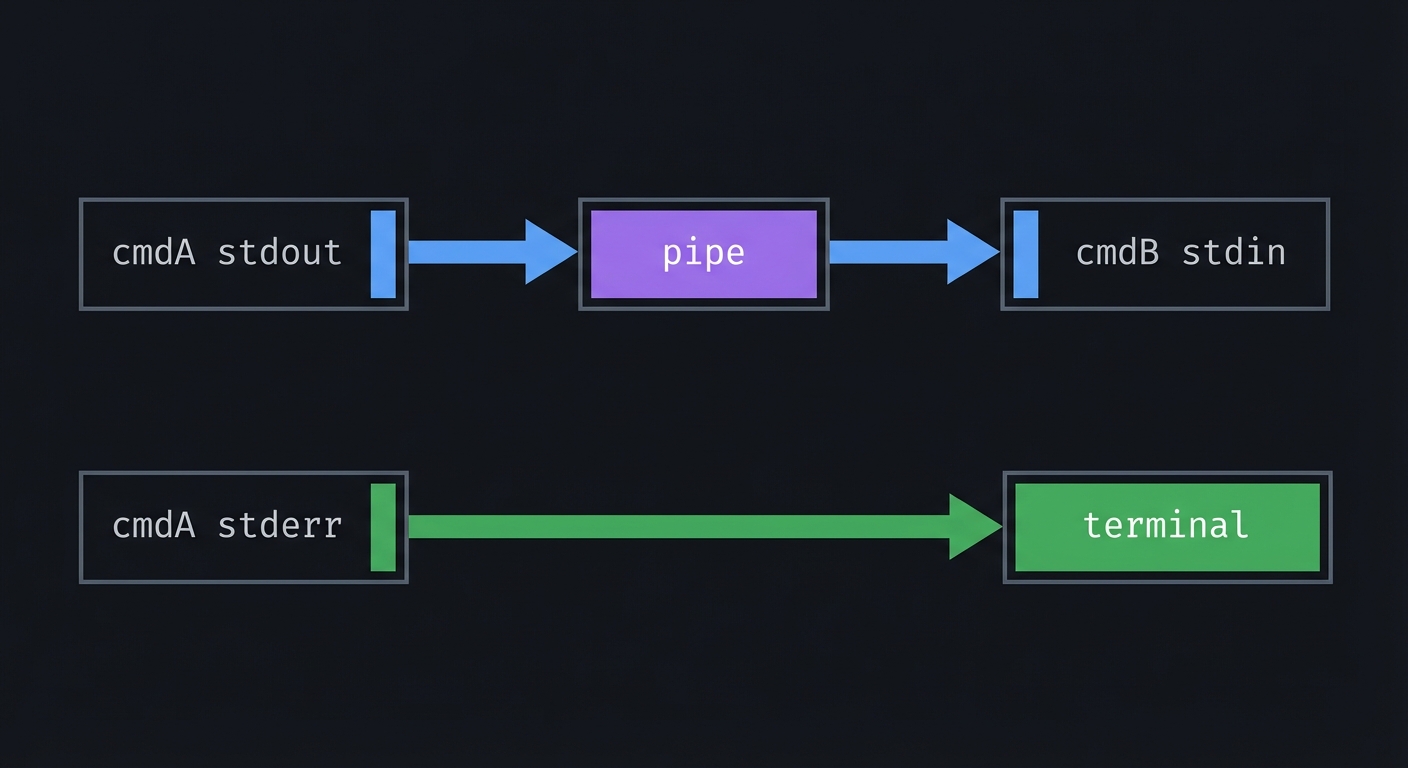

Definition: Pipes are just paired file descriptors. Redirection is just dup2().

cmdA stdout -- pipe --> cmdB stdin

cmdA stderr ----------> terminal

Key ideas:

- A shell is a coordinator: it builds the FD graph, then runs processes

dup2()is the kernel-level primitive that powers>and|

7) Toolchain and Build Automation

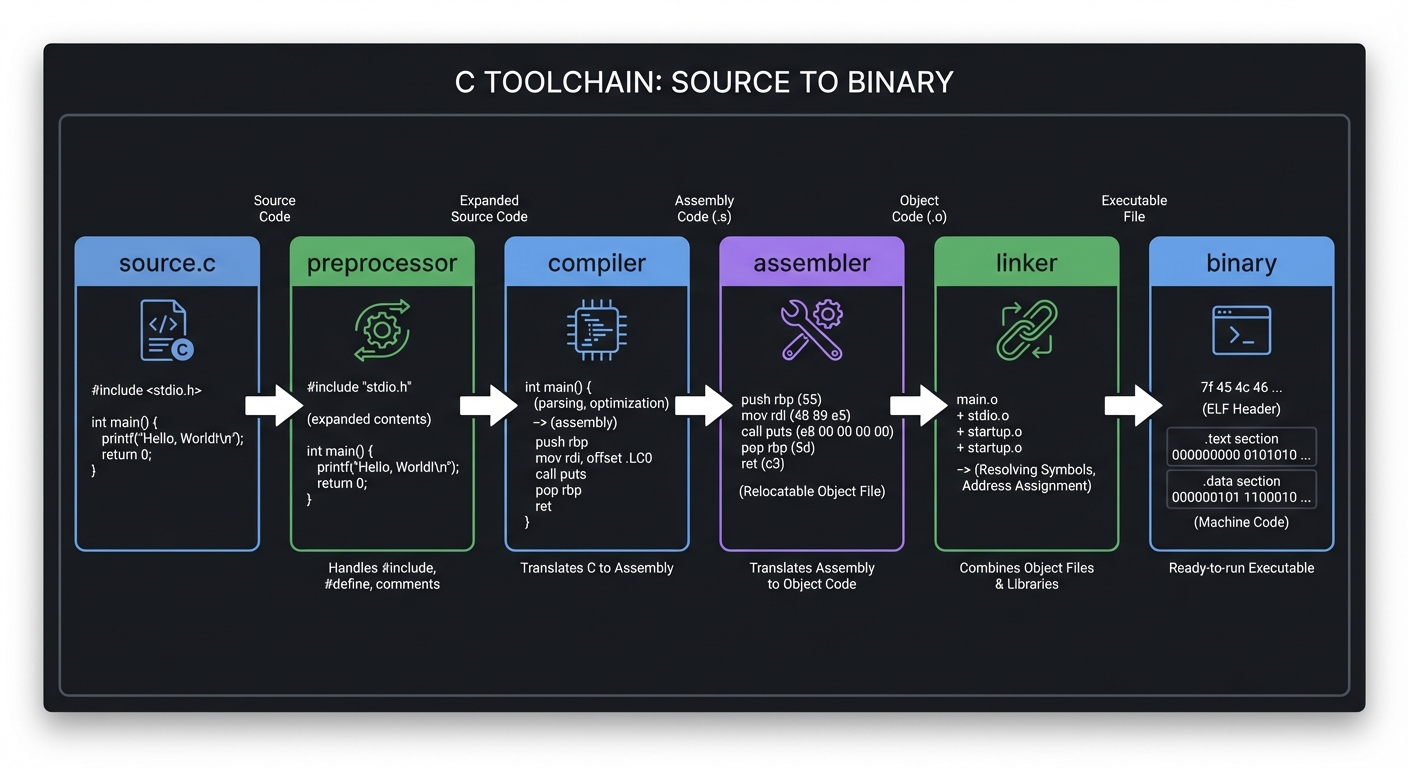

Definition: The toolchain is the pipeline that turns source code into a binary: preprocessing, compilation, assembly, linking.

source.c -> preprocessor -> compiler -> assembler -> linker -> binary

Key ideas:

makeencodes dependency graphs and incremental rebuild logic- Build automation is a systems tool in its own right

Concept Summary Table

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize |

|---|---|

| Streams & FDs | stdin/stdout/stderr are just file descriptors; redirection rewires them. |

| Buffering & Syscalls | libc buffers vs kernel syscalls change performance and visibility. |

| Filesystem Metadata | stat() reveals file truth: types, permissions, sizes, timestamps. |

| Text Processing | stream parsing and state machines are the core pattern. |

| Processes & Exit Codes | fork/exec/wait defines how tools run and report success. |

| Pipes & Redirection | pipe() and dup2() wire processes into pipelines. |

| Toolchain & Make | preprocess/compile/assemble/link and dependency-driven builds. |

Deep Dive Reading by Concept

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Standard I/O and streams | The C Programming Language (K&R) - Ch. 7 |

| Syscalls and file I/O | The Linux Programming Interface - Ch. 3-5 |

| Directories and metadata | The Linux Programming Interface - Ch. 15, 18 |

| Process control | Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment - Ch. 8-9 |

| Pipes and redirection | The Linux Programming Interface - Ch. 44 |

| Regular expressions | The Linux Programming Interface - Ch. 48 |

| Toolchain & linking | Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective - Ch. 7 |

| Build automation | The GNU Make Book - Ch. 1-4 |

Quick Start: First 48 Hours

If you feel overwhelmed, do this first:

Day 1

- Read

man 2 read,man 2 write, andman 3 getline. - Build

my_wcusinggetchar()from stdin only. - Add file input support with

fopen()andgetc().

Day 2

- Implement a

my_catusing syscalls only (open,read,write). - Compare behavior and performance with the stdio version.

- Use

strace/dtrussto see syscalls for your tools vs real GNU tools.

Recommended Learning Paths

Path A: Classic Unix Foundation (Beginner to Intermediate)

my_wc->my_cat->my_ls->my_grep->my_shell

Path B: Text and Streams Focus

my_wc->my_grep->my_cat->my_shell

Path C: Filesystem and Metadata Focus

my_cat->my_ls->my_shell-> Linux From Scratch integration

Project List

The following projects guide you through building your own suite of GNU-like tools, from simple file utilities to a functional shell and a full Linux From Scratch integration.

Project 1: my_wc - The Word Counter

- File: LEARN_GNU_TOOLS_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Go, Python

- Coolness Level: Level 2: Practical but Forgettable

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 1: Beginner

- Knowledge Area: File I/O / Stream Processing

- Software or Tool: A simple text processing utility

- Main Book: “The C Programming Language” by Brian W. Kernighan and Dennis M. Ritchie

What you’ll build: A command-line tool that counts lines, words, and bytes from standard input or a list of files, mimicking the core functionality of wc.

Why it teaches GNU fundamentals: This is the “Hello, World!” of system tools. It forces you to learn the basic building blocks: reading from files, processing character-by-character input, and understanding the difference between lines, words, and bytes.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Reading from stdin vs. files -> maps to handling different input sources

- Counting lines, words, and bytes -> maps to state machine logic

- Handling multiple file arguments -> maps to looping through

argvand printing totals - Matching

wcoutput format -> maps to formatted printing

Key Concepts:

- File I/O: “The C Programming Language” (K&R) Chapter 7

- Command-line arguments: K&R Chapter 5

- Standard I/O: “The Linux Programming Interface” Chapter 5

Difficulty: Beginner Time estimate: A weekend Prerequisites: Basic C programming (loops, functions, variables).

Real world outcome:

$ ./my_wc my_wc.c

250 850 5000 my_wc.c

$ echo "hello world from my wc" | ./my_wc

1 5 23

$ ./my_wc -l my_wc.c

250 my_wc.c

Implementation Hints:

- You need a state machine to track whether you are inside or outside a word.

getchar()is your best friend for reading from stdin.- For file input, use

fopen(),getc(), andfclose(). - A simple state variable (

int in_word = 0;) can track if the current character is part of a word. - A newline (

\n) increments line count. - A whitespace character transitions your state from

in_wordto!in_word.

Learning milestones:

- Counts from stdin correctly -> You understand basic stream processing.

- Counts from a file correctly -> You can handle file I/O.

- Handles multiple files and prints a total -> You can manage command-line arguments and aggregate state.

The Core Question You’re Answering: How do you turn an unstructured byte stream into structured counts while preserving exact Unix semantics?

Concepts You Must Understand First:

- File descriptors and standard streams (K&R Ch. 7)

- Text processing as a state machine (K&R Ch. 7)

stdiobuffering behavior (TLPI Ch. 5)

Questions to Guide Your Design:

- How will you detect word boundaries across line breaks?

- How will you handle tabs and multiple spaces?

- What happens when input is huge and you cannot load it into memory?

Thinking Exercise: Take a paragraph of text and walk through it character by character. Mark where the word count increases. Identify every state transition.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask:

- Why does

wccount bytes instead of characters? - How do buffering and

stdininfluence performance? - How would you support Unicode word boundaries?

- What is the difference between counting bytes and counting characters?

Hints in Layers:

- Hint 1: Track

in_wordas a boolean and only increment word count on a transition from whitespace to non-whitespace. - Hint 2: Treat space, tab, newline, and carriage return as whitespace.

- Hint 3: Use

getc()in a loop; stop onEOF. - Hint 4:

int c, in_word = 0; while ((c = getc(fp)) != EOF) { bytes++; if (c == '\n') lines++; if (isspace(c)) in_word = 0; else if (!in_word) { words++; in_word = 1; } }

Books That Will Help:

| Book | Chapter | Why This Matters |

|——|———|——————|

| The C Programming Language | Ch. 7 | Stream I/O and character classification |

| The Linux Programming Interface | Ch. 5 | stdio vs syscalls and buffering |

| Practical C Programming | Ch. 6 | Character processing patterns |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging: Problem 1: “Counts are too high”

- Why: You increment word count on every non-whitespace char instead of on transitions.

- Fix: Increment only when

in_wordchanges from false to true. - Quick test: Input

"a b"should count 2 words, not 3.

Problem 2: “No output for stdin”

- Why: You are waiting for EOF and not terminating input.

- Fix: In the terminal, press

Ctrl-Dto send EOF. - Quick test:

echo "hi" | ./my_wcshould output counts immediately.

Project 2: my_cat - The Concatenator

- File: LEARN_GNU_TOOLS_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Go

- Coolness Level: Level 2: Practical but Forgettable

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 1: Beginner

- Knowledge Area: File I/O / Syscalls

- Software or Tool: A file content utility

- Main Book: “The Linux Programming Interface” by Michael Kerrisk

What you’ll build: A simplified version of cat that reads one or more files and prints their content to standard output. If no files are given, it reads from standard input.

Why it teaches GNU fundamentals: cat is deceptively simple. Implementing it efficiently teaches you the difference between buffered C library I/O (stdio.h) and raw, unbuffered Unix syscalls (unistd.h). It is a masterclass in I/O performance and correctness.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Reading from files and writing to stdout -> maps to basic I/O loop

- Handling standard input when no files are given -> maps to

if (argc == 1)logic - Efficient I/O -> maps to choosing the right buffer size

- Error handling -> maps to checking return values and using

perror()

Key Concepts:

- Syscalls vs. library functions: “The Linux Programming Interface” Chapter 3

- File I/O Syscalls (

open,read,write,close): “Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment” Chapter 3

Difficulty: Beginner Time estimate: A few hours Prerequisites: Project 1 (or equivalent C knowledge).

Real world outcome:

# Print a file

$ ./my_cat file1.txt

Contents of file1.txt

# Concatenate two files

$ ./my_cat file1.txt file2.txt > combined.txt

# Act as a pass-through for stdin

$ echo "Hello from stdin" | ./my_cat

Hello from stdin

Implementation Hints:

- Compare two approaches:

stdiovs syscalls. - For syscalls, read into a fixed-size buffer (e.g., 4096 bytes) and loop until

read()returns 0. - Always check return values and use

perror()orstrerror(errno).

Learning milestones:

- Basic

catworks for one file -> You understand the core read/write loop. catworks with stdin -> You can handle the no-argument case.- Implement both stdio and syscall versions -> You understand performance and complexity trade-offs.

The Core Question You’re Answering: What is the smallest correct and efficient I/O loop you can build, and how does buffering change behavior?

Concepts You Must Understand First:

- File descriptors and

open/read/write/close(APUE Ch. 3) - Partial reads and writes (TLPI Ch. 4-5)

- Standard streams and redirection (K&R Ch. 7)

Questions to Guide Your Design:

- What happens if

read()returns fewer bytes than requested? - How do you handle input from stdin vs files uniformly?

- How will you handle binary files without corrupting output?

Thinking Exercise: Write a loop that copies bytes from one file to another. Then identify every place it can fail.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask:

- Why can

write()return fewer bytes than requested? - How does buffering affect throughput?

- Why is

catoften used as a benchmark for I/O speed? - What happens if the output file is the same as the input file?

Hints in Layers:

- Hint 1: Use a buffer size that is a multiple of the page size (4096 is a good default).

- Hint 2: Loop on

read()until it returns 0. - Hint 3: Loop on

write()if it returns fewer bytes than requested. - Hint 4:

ssize_t n; char buf[4096]; while ((n = read(fd, buf, sizeof(buf))) > 0) { ssize_t off = 0; while (off < n) { ssize_t w = write(STDOUT_FILENO, buf + off, n - off); if (w < 0) { perror("write"); return 1; } off += w; } }

Books That Will Help: | Book | Chapter | Why This Matters | |——|———|——————| | The Linux Programming Interface | Ch. 3-5 | Syscall basics and I/O semantics | | Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment | Ch. 3 | File I/O APIs and error handling | | Linux System Programming | Ch. 2 | Practical syscall patterns |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging: Problem 1: “Output is truncated”

- Why: You assume

write()writes all bytes at once. - Fix: Loop until all bytes are written.

- Quick test: Use a large file and compare

wc -coutput.

Problem 2: “Binary file is corrupted”

- Why: You used text-mode functions or string logic.

- Fix: Treat input as raw bytes, not strings.

- Quick test:

cmp input.bin output.binshould show no differences.

Project 3: my_ls - The Directory Lister

- File: LEARN_GNU_TOOLS_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Go

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Filesystem Interaction

- Software or Tool: A core filesystem utility

- Main Book: “Advanced Programming in the UNIX(R) Environment” by Stevens and Rago

What you’ll build: A tool that lists the contents of a directory. You’ll start with just names, then add details like permissions, owner, size, and modification time, similar to ls -l.

Why it teaches GNU fundamentals: ls is the window into the filesystem. Building it requires you to interact with directories, file metadata (inodes), user/group information, and time formatting - all core functions of a Unix-like OS.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Reading directory entries -> maps to

opendir,readdir,closedir - Getting file metadata -> maps to the

statsyscall and its struct - Parsing file permissions -> maps to decoding the

st_modebitmask - Fetching user/group names -> maps to

getpwuid,getgrgid - Formatting output into aligned columns -> maps to string formatting and calculation

Key Concepts:

- Directory operations: “The Linux Programming Interface” Chapter 18

- File metadata (the

statstruct): “The Linux Programming Interface” Chapter 15 - Users and Groups: “The Linux Programming Interface” Chapter 8

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 1-2 weeks Prerequisites: Solid C skills, understanding of pointers and structs.

Real world outcome:

$ ./my_ls /dev

crw-r--r-- 1 root root 1, 3 Dec 20 10:00 null

crw-rw-rw- 1 root root 1, 5 Dec 20 10:00 zero

crw-rw-rw- 1 root root 1, 8 Dec 20 10:00 urandom

...

$ ./my_ls -l

-rw-r--r-- 1 user staff 5000 Dec 19 22:10 my_wc.c

-rwxr-xr-x 1 user staff 18752 Dec 19 22:12 my_ls

Implementation Hints:

- Phase 1: list names only with

opendir()andreaddir(). - Phase 2: call

stat()for each entry and decode permissions. - Phase 3: compute column widths first, then print aligned columns.

Learning milestones:

- You can list all filenames in a directory -> You understand directory traversal.

- You can print

statinfo for a single file -> You understand metadata. - You can implement

ls -lwith correct permissions -> You can work with bitmasks and structs. - Your output is column-aligned -> You can handle multi-pass formatting.

The Core Question You’re Answering: How does the filesystem represent files, and how do you translate inode metadata into human-readable output?

Concepts You Must Understand First:

- Directory entries and

struct dirent(TLPI Ch. 18) - File metadata and

struct stat(TLPI Ch. 15) - User/group lookup (

getpwuid,getgrgid) (TLPI Ch. 8)

Questions to Guide Your Design:

- Do you need to call

stat()orlstat()for symlinks? - How will you sort entries (name, time, size)?

- How will you align columns without storing the whole directory?

Thinking Exercise:

Draw a directory tree on paper. For each file, write its inode number, permissions, and size. Then design the output format for ls -l.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask:

- What is the difference between

stat()andlstat()? - Where are filenames stored - inodes or directories?

- Why does

ls -lrequire two passes to align output? - How would you implement

ls -aand handle.and..?

Hints in Layers:

- Hint 1:

readdir()returns.and..unless you filter them. - Hint 2: Use bitmasks like

S_ISDIR(st.st_mode)to check file type. - Hint 3: Use

strftime()for time formatting. - Hint 4:

struct stat st; if (stat(path, &st) == 0) { printf("%c%c%c", (st.st_mode & S_IRUSR) ? 'r' : '-', (st.st_mode & S_IWUSR) ? 'w' : '-', (st.st_mode & S_IXUSR) ? 'x' : '-'); }

Books That Will Help: | Book | Chapter | Why This Matters | |——|———|——————| | The Linux Programming Interface | Ch. 15, 18 | Metadata and directory traversal | | Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment | Ch. 4 | Files and directories | | How Linux Works | Ch. 6 | Filesystems in practice |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging: Problem 1: “Permission bits are wrong”

- Why: You are reading the wrong bit mask or ignoring file type bits.

- Fix: Use the standard

S_IS*macros and permission masks. - Quick test: Compare output with

ls -lon a known file.

Problem 2: “Segfault when listing many files”

- Why: You keep pointers to

direntafterreaddir()advances. - Fix: Copy

d_nameinto your own buffer if you store it. - Quick test: List a directory with hundreds of files.

Project 4: my_grep - The Pattern Matcher

- File: LEARN_GNU_TOOLS_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Go

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Text Processing / Regular Expressions

- Software or Tool: A text search utility

- Main Book: “Mastering Regular Expressions” by Jeffrey E. F. Friedl

What you’ll build: A tool that searches for a pattern in files or standard input and prints matching lines, like grep. Start with simple string matching and then integrate a regex library.

Why it teaches GNU fundamentals: grep is the quintessential Unix tool. It demonstrates the power of stream filtering. Building it teaches you line-by-line processing, string searching, and how to use regex libraries for complex matching.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Line-oriented reading -> maps to efficient line buffering

- Simple string search -> maps to implementing

strstror similar - Integrating a regex library -> maps to using POSIX

regex.h - Handling options (

-i,-v) -> maps to parsing flags and altering logic

Key Concepts:

- Line-oriented I/O:

getline()is ideal here. Seeman getline. - String Searching: CLRS Chapter 32 covers string matching.

- POSIX Regular Expressions: “The Linux Programming Interface” Chapter 48.

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 1-2 weeks Prerequisites: C programming, Project 1.

Real world outcome:

# Search for a string in a file

$ ./my_grep "main" my_ls.c

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

// ... more lines containing "main"

# Invert match and ignore case from stdin

$ echo -e "Hello\nWorld\nhello" | ./my_grep -v -i "hello"

World

Implementation Hints:

- Part 1: use

getline()+strstr()for simple matching. - Part 2: use

regcomp()/regexec()for regex support. - Free the buffer allocated by

getline()and callregfree().

Learning milestones:

- Simple string search works -> You can read line-by-line and use

strstr. - Regex search works -> You can compile and execute POSIX regex.

- Flags like

-iand-vare implemented -> You can handle options. - It works on stdin and files -> You have robust input handling.

The Core Question You’re Answering: How do you scan a stream for matches efficiently while preserving the exact lines and formatting users expect?

Concepts You Must Understand First:

- Line buffering and dynamic input (

getline) (TLPI Ch. 5) - String matching basics (CLRS Ch. 32)

- Regex compilation and execution (TLPI Ch. 48)

Questions to Guide Your Design:

- What should happen if a line is longer than your buffer?

- How will you handle binary files? (grep usually detects and skips)

- How do flags interact (

-iwith-v)?

Thinking Exercise:

Write a regex for a simple log line (timestamp, level, message). Then simulate how grep would scan each line.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask:

- What is the difference between substring search and regex?

- Why is

getline()safer than fixed-size buffers? - How would you implement

grep -rrecursively? - Why might

greptreat binary files differently?

Hints in Layers:

- Hint 1: Use

getline()to handle any line length. - Hint 2: Start with

strstr()to match a literal string. - Hint 3: Add

regex.hand compile once before the loop. - Hint 4:

regex_t re; regcomp(&re, pattern, REG_NOSUB | (ignore_case ? REG_ICASE : 0)); while (getline(&line, &cap, fp) != -1) { int match = (regexec(&re, line, 0, NULL, 0) == 0); if ((match && !invert) || (!match && invert)) fputs(line, stdout); } regfree(&re);

Books That Will Help: | Book | Chapter | Why This Matters | |——|———|——————| | The Linux Programming Interface | Ch. 48 | POSIX regex API | | Mastering Regular Expressions | Ch. 1-3 | Regex thinking and patterns | | Practical C Programming | Ch. 9 | Text processing practices |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging: Problem 1: “Regex never matches”

- Why: You forgot to escape regex characters or used

strstr()with regex syntax. - Fix: Decide whether you are in literal or regex mode and document it.

- Quick test: Pattern

"a.c"should match"abc"in regex mode.

Problem 2: “It crashes on long lines”

- Why: You used fixed-size buffers.

- Fix: Use

getline()to grow buffers dynamically. - Quick test:

python -c "print('a'*100000)" | ./my_grep ashould work.

Project 5: A Simple Shell

- File: LEARN_GNU_TOOLS_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Go

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Process Management / IPC

- Software or Tool: A shell/command interpreter

- Main Book: “Advanced Programming in the UNIX(R) Environment” by Stevens and Rago

What you’ll build: A basic command-line shell that can read user input, execute programs, and handle simple pipes (|) and I/O redirection (<, >).

Why it teaches GNU fundamentals: The shell is the glue that holds the GNU environment together. Building one is the ultimate exercise in OS-level programming. You will master process creation (fork), program execution (exec), and inter-process communication (pipe, dup2).

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Parsing command lines -> maps to splitting a string into a command and arguments

- Executing external programs -> maps to the

fork/exec/waitpattern - Implementing redirection -> maps to

dup2to changestdin/stdout - Implementing pipes -> maps to

pipeanddup2to connect processes

Key Concepts:

- Process Creation: “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” Chapters 5-6

- Process Control (

fork,exec,wait): “The Linux Programming Interface” Chapters 24-27 - I/O Redirection and Pipes (

dup2,pipe): “The Linux Programming Interface” Chapter 44

Difficulty: Advanced Time estimate: 2-4 weeks Prerequisites: Strong C skills, understanding of pointers.

Real world outcome:

$ ./my_shell

mysh> ls -l | grep .c > output.txt

mysh> cat output.txt

-rw-r--r-- 1 user staff 5000 Dec 19 22:10 my_wc.c

-rw-r--r-- 1 user staff 3500 Dec 19 22:11 my_ls.c

mysh> exit

Implementation Hints:

- Main loop: print prompt, read line, tokenize, detect pipes/redirection, execute.

- For a simple command:

fork()thenexecvp()in child,wait()in parent. - For pipes: create a pipe, fork twice,

dup2()FDs, thenexecvp().

Learning milestones:

- Single command execution works -> You mastered

fork/exec/wait. - Redirection (

>) works -> You understanddup2and FDs. - Pipes (

|) work -> You can connect processes. - Built-ins (

cd,exit) work -> You understand parent vs child state.

The Core Question You’re Answering:

How does a shell turn a string like ls -l | grep .c > out.txt into a process graph that the kernel can execute?

Concepts You Must Understand First:

- Tokenization and parsing basics (Practical C Programming Ch. 11)

fork,exec,wait, and process lifecycles (TLPI Ch. 24-27)- Pipes and

dup2(TLPI Ch. 44)

Questions to Guide Your Design:

- How will you represent a pipeline internally (array of commands, linked list)?

- How will you handle quotes and escaped spaces?

- What happens when a child exits and you forget to

wait()?

Thinking Exercise:

Take the command cat file | grep error | wc -l > count.txt. Draw the process tree and file descriptor wiring before you write a single line of code.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask:

- Why must

cdbe a built-in, not an external command? - What happens if you forget to close the unused pipe ends?

- How does the shell handle

SIGINT(Ctrl-C)? - How do you prevent zombie processes?

Hints in Layers:

- Hint 1: Build a minimal shell that can run a single command first.

- Hint 2: Add redirection using

dup2()andopen(). - Hint 3: Add a 2-command pipeline before supporting multiple stages.

- Hint 4:

int pipefd[2]; pipe(pipefd); if (fork() == 0) { dup2(pipefd[1], STDOUT_FILENO); close(pipefd[0]); close(pipefd[1]); execvp(cmd1[0], cmd1); } if (fork() == 0) { dup2(pipefd[0], STDIN_FILENO); close(pipefd[1]); close(pipefd[0]); execvp(cmd2[0], cmd2); } close(pipefd[0]); close(pipefd[1]); wait(NULL); wait(NULL);

Books That Will Help: | Book | Chapter | Why This Matters | |——|———|——————| | The Linux Programming Interface | Ch. 24-27, 44 | Process control and pipes | | Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment | Ch. 8-9 | Process and signal handling | | Shell Programming in Unix, Linux and OS X | Ch. 1-4 | Shell semantics and parsing |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging: Problem 1: “Pipeline hangs”

- Why: You did not close unused pipe ends, so the reader never sees EOF.

- Fix: Close unused ends in both parent and children.

- Quick test:

echo hi | ./my_shell catshould exit immediately.

Problem 2: “Built-in commands do not work”

- Why: You are running

cdin a child process. - Fix: Execute built-ins in the parent before forking.

- Quick test:

cd /tmpshould change the shell’s current directory.

Project Comparison Table

| Project | Difficulty | Time | Depth of Understanding | Fun Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

my_wc |

Level 1: Beginner | Weekend | Low | * |

my_cat |

Level 1: Beginner | Weekend | Low | * |

my_ls |

Level 2: Intermediate | 1-2 weeks | Medium | *** |

my_grep |

Level 2: Intermediate | 1-2 weeks | Medium | *** |

my_shell |

Level 3: Advanced | 1 month+ | High | ***** |

Recommendation

Start with my_wc or my_cat. They are small and contained, and will teach you the fundamental I/O patterns in C that all other projects rely on.

Then move to my_ls. This project is the perfect introduction to interacting with filesystem metadata. It is more complex but very rewarding.

Finally, tackle my_shell. This is the capstone project for process management. If you can build a shell that handles pipes correctly, you have demonstrated a deep and practical understanding of how Unix-like operating systems work.

Final Overall Project: Build a Linux From Scratch System with Your Tools

- File: LEARN_GNU_TOOLS_DEEP_DIVE.md

- Main Programming Language: C, Shell Script

- Coolness Level: Level 5: Pure Magic (Super Cool)

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 5: Master

- Knowledge Area: Full OS Construction

- Software or Tool: Linux Kernel, BusyBox, and your own tools

- Main Book: “Linux From Scratch” (www.linuxfromscratch.org)

What you’ll build: A complete, bootable, minimal Linux system from source code. But with a twist: as you progress through the LFS book, you will replace the standard GNU coreutils (ls, cat, sh, etc.) with the versions you built in the previous projects.

Why it’s the final goal: This project synthesizes everything. You are not just building tools; you are building an entire environment and then using your own tools to manage it. It forces you to understand the toolchain, bootstrapping, cross-compilation, and the role every utility plays in a functioning system.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Cross-compilation -> maps to building tools for a different architecture than you’re running on

- Bootstrapping a C library -> maps to the chicken-and-egg problem of compiling a compiler

- Kernel configuration -> maps to understanding drivers and kernel modules

- Integrating your own tools -> maps to making your tools robust enough for a real system

Real world outcome:

You boot a VM (or physical hardware) into a command prompt that is running your shell. You type ./my_ls and it lists the files using your code. You have built a self-contained, minimal GNU/Linux operating environment.

The Core Question You’re Answering: How do you bootstrap an operating system from source, and what exact tools are required to make the system self-hosting?

Concepts You Must Understand First:

- Toolchain stages: compile, assemble, link (CS:APP Ch. 7)

- Cross-compilation and sysroot concepts (LFS Book Ch. 5)

- Basic init system behavior (How Linux Works Ch. 3)

Questions to Guide Your Design:

- Which of your tools must be present before the system can build itself?

- How will you validate that your tools behave like GNU coreutils?

- What is the minimal set of tools needed for a bootable userland?

Thinking Exercise: Make a dependency graph of tools required to build the kernel, the C library, and the shell. Identify the smallest bootstrap set.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask:

- Why is cross-compilation necessary in LFS?

- What happens if your

my_shelllacks job control? - How do you verify correctness of your core utilities?

- What is the difference between static and dynamic linking in a bootstrap system?

Hints in Layers:

- Hint 1: Follow the LFS toolchain chapters exactly on the first pass.

- Hint 2: Substitute one of your tools at a time, not all at once.

- Hint 3: Keep the original GNU tools available as fallback.

- Hint 4: Use a VM snapshot before each major phase.

Books That Will Help: | Book | Chapter | Why This Matters | |——|———|——————| | Linux From Scratch | Ch. 4-7 | Toolchain and bootstrap process | | Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective | Ch. 7 | Linking and loading concepts | | How Linux Works | Ch. 3-5 | Boot and init flow |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging: Problem 1: “Build fails mid-toolchain”

- Why: Environment variables or PATH are misconfigured.

- Fix: Re-check LFS environment setup and verify

PATHorder. - Quick test:

which gccandgcc --versionshould point to the LFS toolchain.

Problem 2: “Booted system lacks core commands”

- Why: A tool was not installed into the correct sysroot.

- Fix: Verify install prefixes and re-run

make installwith correct DESTDIR. - Quick test:

ls /bininside the target should show your tools.

Summary

| Project | Main Programming Language |

|---|---|

my_wc |

C |

my_cat |

C |

my_ls |

C |

my_grep |

C |

my_shell |

C |

| Linux From Scratch with Your Tools | C, Shell Script |