Learn C++ Concurrency and Parallelism: From Zero to Lock-Free Master

Goal: Deeply understand C++ concurrency and parallelism—from basic threading primitives through atomics and the memory model, to modern coroutines and SIMD operations. Build real systems that force you to confront race conditions, deadlocks, cache coherence, and the fundamental challenges of parallel programming.

Why C++ Concurrency Matters

Modern CPUs don’t get faster—they get wider. A 2024 laptop has 8-16 cores; a server might have 128+. The only way to use this power is through concurrent and parallel programming. C++ gives you:

- Zero-cost abstractions: Threads, atomics, and parallel algorithms that compile to optimal machine code

- Memory model guarantees: A formal specification of what concurrent code means

- Hardware-level control: Direct access to atomic operations, memory fences, and SIMD instructions

- Modern conveniences: Coroutines, parallel STL, and upcoming std::simd

After completing these projects, you will:

- Understand exactly what happens when multiple threads access shared data

- Know when to use mutexes vs atomics vs lock-free structures

- Write code that scales efficiently across cores

- Build async systems with C++20 coroutines

- Leverage SIMD for data-parallel performance

Core Concept Analysis

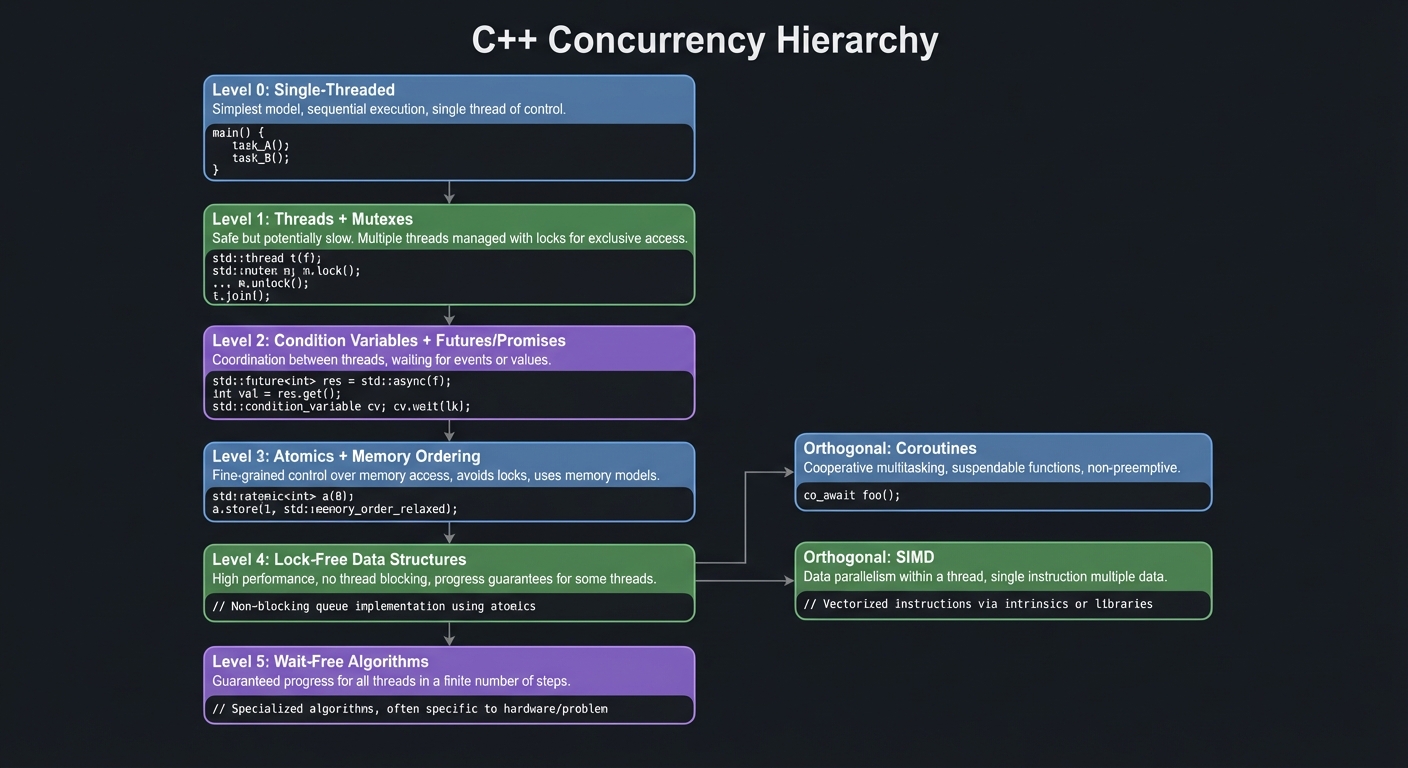

The Concurrency Hierarchy

Level 0: Single-Threaded

|

Level 1: Threads + Mutexes (safe but potentially slow)

|

Level 2: Condition Variables + Futures/Promises (coordination)

|

Level 3: Atomics + Memory Ordering (fine-grained control)

|

Level 4: Lock-Free Data Structures (high performance)

|

Level 5: Wait-Free Algorithms (guaranteed progress)

|

Orthogonal: Coroutines (cooperative multitasking)

|

Orthogonal: SIMD (data parallelism within a thread)

Fundamental Concepts

- Thread Safety: Code that produces correct results regardless of thread scheduling

- Data races: Undefined behavior when threads access shared data without synchronization

- Race conditions: Logic errors that depend on timing (can exist even with mutexes!)

- Synchronization Primitives:

- Mutex: Mutual exclusion—only one thread at a time

- Condition Variable: Wait until something becomes true

- Future/Promise: One-shot communication channel

- Semaphore (C++20): Counting resource guard

- Latch/Barrier (C++20): Synchronization points

- The C++ Memory Model (Critical!):

- Sequential Consistency (

memory_order_seq_cst): Everyone sees operations in the same order - Acquire-Release (

memory_order_acquire/release): Synchronizes between specific pairs - Relaxed (

memory_order_relaxed): No ordering guarantees, just atomicity

- Sequential Consistency (

- Lock-Free vs Wait-Free:

- Lock-free: System-wide progress guaranteed (some thread always advances)

- Wait-free: Per-thread progress guaranteed (every thread advances)

- Parallel Algorithms:

std::execution::seq: Sequentialstd::execution::par: Parallel (may use thread pool)std::execution::par_unseq: Parallel + vectorized (SIMD)

- Coroutines (C++20):

- Stackless: State stored on heap, not stack

- Keywords:

co_await,co_yield,co_return - Components: Promise type, coroutine handle, awaiter

- SIMD (Single Instruction, Multiple Data):

- Process multiple values with one instruction

std::simd(C++26): Portable SIMD abstraction- Currently:

std::experimental::simdin GCC 11+

Project List

Projects progress from foundational understanding to advanced implementations. Each project builds on concepts from previous ones.

Project 1: Multi-Threaded Log Aggregator

- File: LEARN_CPP_CONCURRENCY_AND_PARALLELISM.md

- Main Programming Language: C++

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Go, Java

- Coolness Level: Level 2: Practical but Forgettable

- Business Potential: 2. The “Micro-SaaS / Pro Tool”

- Difficulty: Level 1: Beginner

- Knowledge Area: Threading Fundamentals / Synchronization

- Software or Tool: Log Processing System

- Main Book: “C++ Concurrency in Action, Second Edition” by Anthony Williams

What you’ll build: A system where multiple producer threads generate log messages while a single consumer thread aggregates and writes them to disk, with proper synchronization and no data races.

Why it teaches concurrency: This is the “Hello World” of multithreading—simple enough to understand, but complex enough to encounter your first race conditions and deadlocks. You’ll feel the pain of shared mutable state.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Protecting shared data with mutexes → maps to understanding critical sections and lock scope

- Avoiding deadlocks → maps to lock ordering and RAII lock guards

- Coordinating shutdown → maps to graceful thread termination patterns

- Handling high-volume logging → maps to understanding contention and throughput

Key Concepts:

- std::thread basics: “C++ Concurrency in Action” Chapter 2 - Anthony Williams

- Mutex and Lock Guards: “C++ Concurrency in Action” Chapter 3 - Anthony Williams

- Thread-Safe Queue: “C++ Concurrency in Action” Chapter 6.2 - Anthony Williams

Difficulty: Beginner Time estimate: Weekend Prerequisites: Solid C++ fundamentals (RAII, move semantics), basic understanding of what threads are conceptually. No prior threading experience required.

Real world outcome:

$ ./log_aggregator

[Producer-1] Starting...

[Producer-2] Starting...

[Producer-3] Starting...

[Aggregator] Received 1000 messages, writing batch...

[Aggregator] Wrote batch to logs/2024-01-15_001.log

[Producer-1] Generated 5000 log entries

[Producer-2] Generated 4892 log entries

[Producer-3] Generated 5108 log entries

[Aggregator] Final stats: 15000 messages, 0 dropped, avg latency 0.3ms

$ cat logs/2024-01-15_001.log

2024-01-15T10:30:15.123Z [INFO] [Producer-1] User login: user_42

2024-01-15T10:30:15.124Z [WARN] [Producer-2] Memory usage: 85%

...

Implementation Hints:

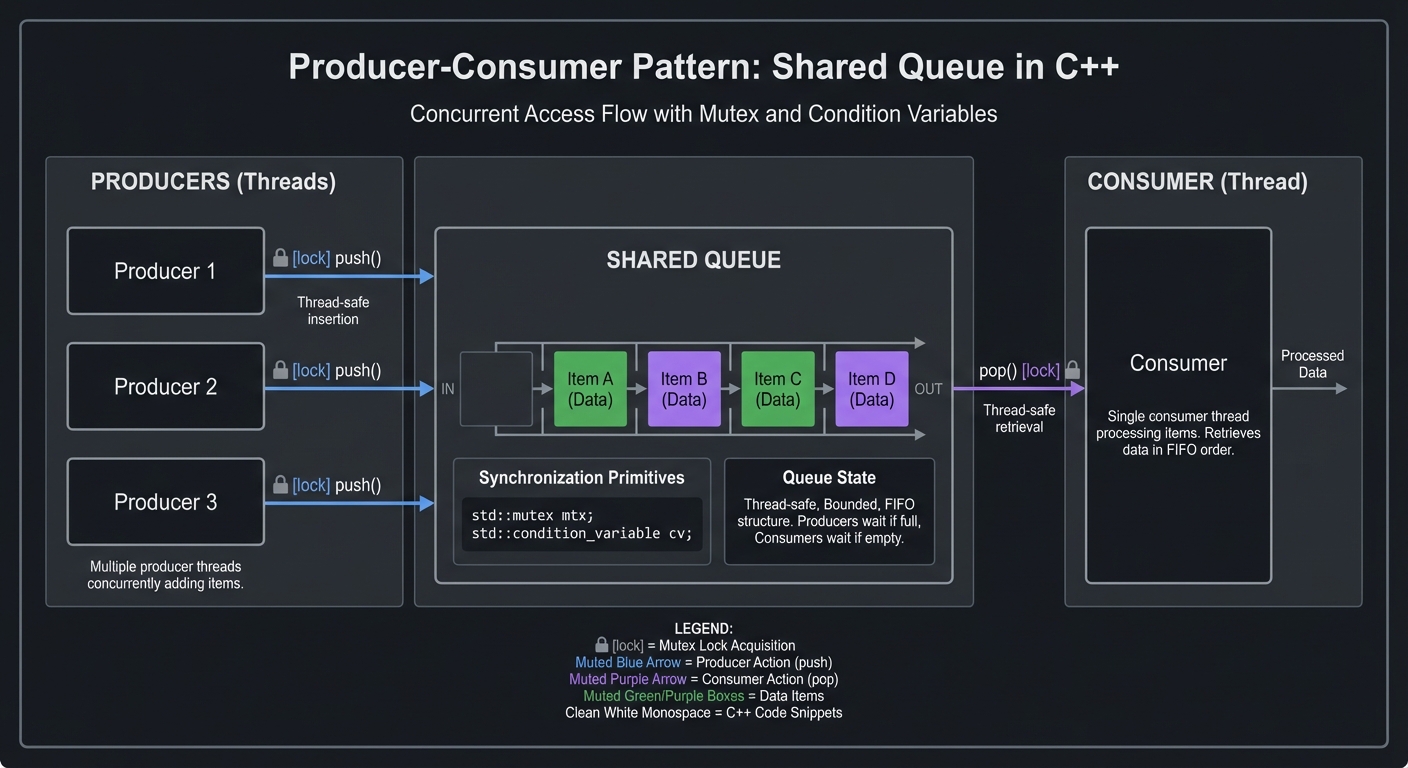

The fundamental pattern is Producer-Consumer with a shared buffer:

Producers Shared Queue Consumer

| | |

+---> [lock] push() --->| |

| |<--- pop() [lock] <-----+

+---> [lock] push() --->| |

Key design questions to answer:

- What data structure holds the messages? (Hint:

std::queue+std::mutex) - How do producers add messages? (Hint: lock, push, unlock)

- How does the consumer wait for messages? (Hint: busy-wait first, then condition variable)

- How do you signal shutdown? (Hint: atomic flag or poison pill)

- How do you ensure the mutex is always released? (Hint:

std::lock_guardorstd::unique_lock)

Start with the simplest possible implementation:

- Single mutex protecting a

std::queue - Consumer polls the queue in a loop

- All threads check an

std::atomic<bool>for shutdown

Then improve:

- Add

std::condition_variableto eliminate polling - Add batching (write every N messages or T milliseconds)

- Measure throughput—how many messages/second?

Common mistakes to avoid:

- Forgetting to lock before accessing shared data

- Holding the lock while doing I/O (blocks producers)

- Not handling spurious wakeups with condition variables

- Joining threads that were never started

Learning milestones:

- Threads start and run concurrently → You understand

std::threadandjoin() - No crashes or garbled output → You understand mutex protection

- Consumer waits efficiently → You understand condition variables

- Clean shutdown with no data loss → You understand thread coordination

Project 2: Promise-Based Task Coordinator

- File: LEARN_CPP_CONCURRENCY_AND_PARALLELISM.md

- Main Programming Language: C++

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, JavaScript (for comparison), Go

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Futures / Promises / Async Patterns

- Software or Tool: Distributed Task System

- Main Book: “C++ Concurrency in Action, Second Edition” by Anthony Williams

What you’ll build: A task execution system where jobs can depend on other jobs, using std::future and std::promise to coordinate completion and pass results between tasks.

Why it teaches futures/promises: Futures and promises are the building blocks of async programming. They let you express “do this, and when it’s done, do that” without callbacks or shared state. Understanding them deeply prepares you for coroutines.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Passing results between threads → maps to understanding promise/future pair as a one-shot channel

- Handling exceptions across threads → maps to exception propagation through promises

- Building dependency graphs → maps to chaining futures and handling multiple dependencies

- Avoiding deadlocks in dependencies → maps to understanding blocking in

future::get()

Key Concepts:

- std::future and std::promise: “C++ Concurrency in Action” Chapter 4.2 - Anthony Williams

- std::async and task-based parallelism: “C++ Concurrency in Action” Chapter 4.2.1 - Anthony Williams

- std::shared_future for multiple consumers: “C++ Concurrency in Action” Chapter 4.2.2 - Anthony Williams

- Exception handling in futures: “C++ Concurrency in Action” Chapter 4.2.4 - Anthony Williams

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 1-2 weeks Prerequisites: Project 1 completed, understanding of basic threading. Familiarity with move semantics (futures are move-only).

Real world outcome:

$ ./task_coordinator

Submitting task graph:

Task A: Download data.json

Task B: Parse JSON (depends on A)

Task C: Validate schema (depends on A)

Task D: Transform data (depends on B, C)

Task E: Upload results (depends on D)

[Executor] Starting Task A...

[Executor] Task A completed (1.2s)

[Executor] Starting Task B (dependency A satisfied)...

[Executor] Starting Task C (dependency A satisfied)...

[Executor] Task C completed (0.3s)

[Executor] Task B completed (0.8s)

[Executor] Starting Task D (dependencies B,C satisfied)...

[Executor] Task D completed (0.5s)

[Executor] Starting Task E (dependency D satisfied)...

[Executor] Task E completed (0.9s)

All tasks completed successfully!

Total time: 3.7s (would be 4.7s sequential)

$ ./task_coordinator --with-failure

[Executor] Starting Task A...

[Executor] Task A completed (1.2s)

[Executor] Starting Task B (dependency A satisfied)...

[Executor] Task B FAILED: JSON parse error at line 42

[Executor] Task D cancelled: dependency B failed

[Executor] Task E cancelled: dependency D failed

Task graph failed. 2 tasks completed, 1 failed, 2 cancelled.

Implementation Hints:

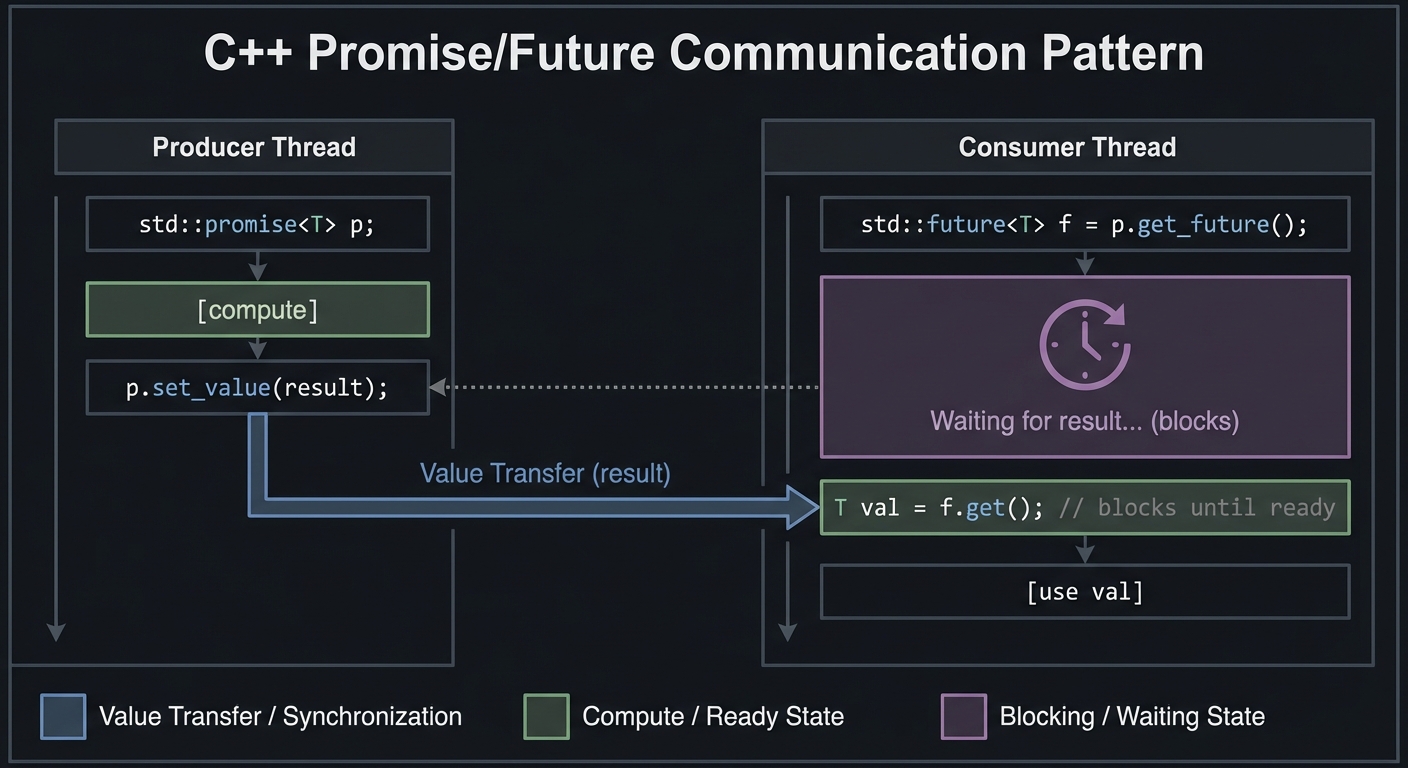

The core insight: a std::promise is one end of a pipe, and std::future is the other end.

Producer Thread Consumer Thread

| |

std::promise<T> p; std::future<T> f = p.get_future();

| |

[compute] |

| |

p.set_value(result); ---------> T val = f.get(); // blocks until ready

For task dependencies, think in terms of data flow:

- Each task takes input (from dependency results) and produces output

- A task’s promise is fulfilled when it completes

- Dependent tasks call

get()on their dependencies’ futures

Key design questions:

- How do you represent a task? (Hint: callable + vector of dependencies + promise)

- How do you know when dependencies are satisfied? (Hint: try

wait_for()on each future) - How do you handle a task throwing an exception? (Hint:

promise::set_exception()) - How do you cancel downstream tasks when upstream fails? (Hint: propagate a “failed” state)

- When can tasks run in parallel? (Hint: when they don’t depend on each other)

Architecture approach:

- Task structure: ID, callable, dependencies (vector of task IDs), result promise

- Task graph: map of ID → Task

- Executor: thread pool + ready queue + completion tracking

- Scheduling: when a task completes, check if any waiting tasks are now ready

Start simple:

- Linear chain: A → B → C (each depends on previous)

- Diamond: A → B, A → C, B+C → D (tests shared_future for A)

- Exception propagation: A fails, B and C should fail automatically

Learning milestones:

- Single promise/future pair works → You understand the basic mechanism

- Linear task chains execute in order → You understand blocking on

get() - Parallel independent tasks → You understand when futures don’t block each other

- Exception propagation works → You understand error handling across threads

- Complex DAGs execute correctly → You understand dependency graph execution

Project 3: Work-Stealing Thread Pool

- File: LEARN_CPP_CONCURRENCY_AND_PARALLELISM.md

- Main Programming Language: C++

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Go, Java

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 4. The “Open Core” Infrastructure

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Thread Pool Design / Work Scheduling

- Software or Tool: High-Performance Thread Pool Library

- Main Book: “C++ Concurrency in Action, Second Edition” by Anthony Williams

What you’ll build: A production-quality thread pool with per-thread work queues and work-stealing for load balancing, supporting task submission, futures, and graceful shutdown.

Why it teaches advanced threading: Thread pools are the foundation of modern parallel systems. Work-stealing teaches you about cache locality, contention reduction, and the art of balancing work across cores. This is what powers TBB, Tokio, and Go’s runtime.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Designing thread-safe work queues → maps to lock-free deques or fine-grained locking

- Implementing work stealing → maps to understanding locality vs load balance tradeoffs

- Handling task submission and results → maps to packaged_task and future integration

- Graceful shutdown → maps to draining queues and joining threads

- Avoiding contention → maps to per-thread data and cache-friendly design

Key Concepts:

- Thread Pool Architecture: “C++ Concurrency in Action” Chapter 9 - Anthony Williams

- Work Stealing: BS::thread_pool documentation

- Packaged Task: “C++ Concurrency in Action” Chapter 4.2.3 - Anthony Williams

- Cache Locality in Concurrent Systems: “The Art of Multiprocessor Programming” Chapter 16 - Herlihy & Shavit

Difficulty: Advanced Time estimate: 2-4 weeks Prerequisites: Projects 1-2 completed. Strong understanding of move semantics, templates, and type erasure. Familiarity with memory layout and cache effects helpful.

Real world outcome:

$ ./thread_pool_benchmark

Thread Pool Configuration:

Workers: 8 (matching hardware_concurrency)

Queue type: Lock-free deque with work stealing

Running benchmark: 100,000 small tasks (1μs each)

Submitted all tasks in 45ms

All tasks completed in 180ms

Throughput: 555,555 tasks/second

Work stealing events: 12,847 (load was balanced)

Running benchmark: 1,000 large tasks (10ms each, with subtasks)

Total work: 50,000 subtasks

Completion time: 625ms

Speedup vs sequential: 7.8x (theoretical max: 8x)

Efficiency: 97.5%

Running benchmark: Heterogeneous workload

Mix of 1μs, 100μs, and 10ms tasks

No worker idle time > 1ms

Work stealing kept all cores busy

$ ./thread_pool_demo

auto future = pool.submit([](int x) { return x * 2; }, 21);

std::cout << future.get() << std::endl; // prints 42

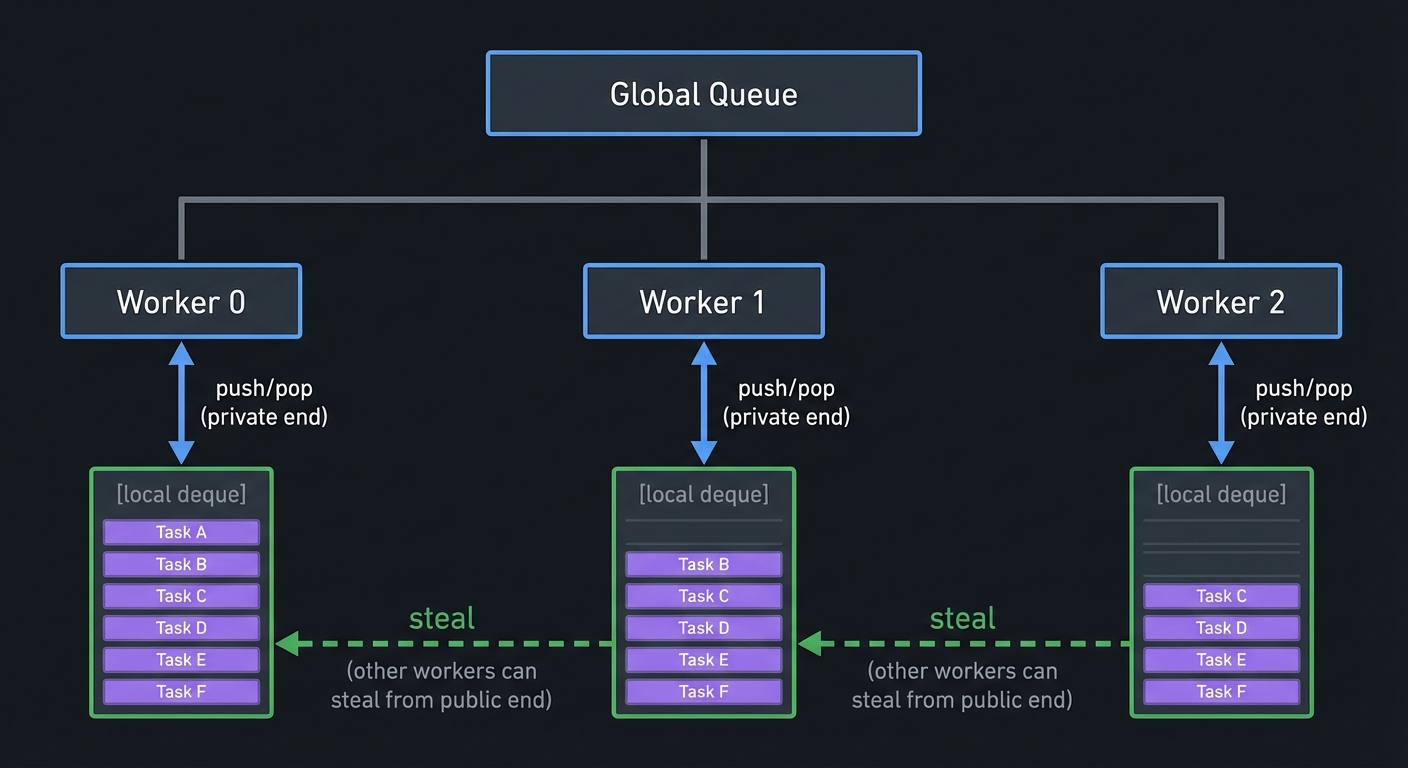

Implementation Hints:

Work-stealing architecture:

Global Queue (optional, for external submissions)

|

+---------------------+---------------------+

| | |

Worker 0 Worker 1 Worker 2

[local deque] [local deque] [local deque]

↑ ↑ ↑

push/pop push/pop push/pop

(private end) (private end) (private end)

↓ ↓ ↓

steal ←←←←←←←←←←←←←← steal ←←←←←←←←←←←←←← steal

(other workers can steal from public end)

Key insight: Each worker has a deque. It pushes/pops from one end (fast, usually no contention) but other workers can steal from the other end when idle.

Design decisions to make:

- Queue type: Start with

std::deque+ mutex, then optimize to lock-free - Stealing strategy: Random victim? Least-loaded? Round-robin?

- Task representation:

std::function<void()>with type erasure - Result handling:

std::packaged_taskwraps the task, returnsstd::future - Termination: Signal threads, let them drain their queues, then join

Implementation phases:

- Basic thread pool (no stealing): Fixed workers, shared queue, works but has contention

- Per-thread queues: Each worker has own queue, external submissions go to random worker

- Work stealing: Idle workers check other queues

- Optimizations: Reduce atomic operations, add backoff, consider NUMA

The submit function needs type erasure:

template<typename F, typename... Args>

auto submit(F&& f, Args&&... args) -> std::future<std::invoke_result_t<F, Args...>>;

Use std::packaged_task to wrap the callable and get a future.

Common pitfalls:

- ABA problem if using lock-free deque (needs hazard pointers or epoch-based reclamation)

- Starvation if stealing isn’t fair

- False sharing between worker data structures

- Forgetting to handle exceptions in tasks

Learning milestones:

- Basic pool executes tasks → You understand worker thread lifecycle

- submit() returns working future → You understand packaged_task integration

- Per-thread queues reduce contention → You understand locality benefits

- Work stealing balances load → You understand dynamic scheduling

- Matches/beats std::async performance → You’ve built production-quality infrastructure

Project 4: Spinlock and Read-Write Lock Library

- File: LEARN_CPP_CONCURRENCY_AND_PARALLELISM.md

- Main Programming Language: C++

- Alternative Programming Languages: C, Rust, Assembly (for comparison)

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Atomics / Synchronization Primitives

- Software or Tool: Synchronization Primitive Library

- Main Book: “C++ Concurrency in Action, Second Edition” by Anthony Williams

What you’ll build: Custom spinlock and read-write lock implementations using only std::atomic, with different fairness and performance characteristics, benchmarked against standard library primitives.

Why it teaches atomics: Building locks from atomics forces you to understand exactly what atomic operations guarantee. You’ll learn about compare-and-swap, memory ordering, and why “just use a mutex” is often the right answer.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Implementing CAS loops correctly → maps to understanding compare_exchange semantics

- Choosing memory orderings → maps to understanding acquire/release vs seq_cst

- Avoiding livelock → maps to understanding fairness and backoff

- Reader-writer coordination → maps to more complex atomic state machines

- Benchmarking correctly → maps to understanding micro-benchmark pitfalls

Key Concepts:

- Atomic Operations: “C++ Concurrency in Action” Chapter 5.2 - Anthony Williams

- Memory Ordering: “C++ Concurrency in Action” Chapter 5.3 - Anthony Williams

- Spinlock Implementation: Preshing on Programming - “An Introduction to Lock-Free Programming”

- Compare-and-Swap: “C++ Concurrency in Action” Chapter 5.2.4 - Anthony Williams

Difficulty: Advanced Time estimate: 1-2 weeks Prerequisites: Projects 1-2 completed. Understanding of basic atomic operations. Familiarity with how mutexes work conceptually.

Real world outcome:

$ ./spinlock_benchmark

Testing: Simple Spinlock (test-and-set)

Uncontended lock/unlock: 15 cycles

2 threads, 1M ops each: 450ms (high contention)

8 threads, 1M ops each: 2100ms (severe contention)

Testing: Spinlock with exponential backoff

Uncontended lock/unlock: 15 cycles

2 threads, 1M ops each: 380ms

8 threads, 1M ops each: 890ms (much better!)

Testing: Ticket Spinlock (fair)

Uncontended lock/unlock: 25 cycles

8 threads, 1M ops each: 920ms

Fairness: All threads got equal turns ✓

Testing: Read-Write Lock (readers=7, writers=1)

Readers can proceed concurrently ✓

Writer gets exclusive access ✓

No starvation detected after 10s

Comparison with std::mutex:

Uncontended: 45 cycles (slower due to syscall potential)

8 threads: 650ms (OS scheduler helps with contention)

Conclusion: Spinlocks win when contention is low and critical

sections are tiny. Otherwise, use std::mutex.

Implementation Hints:

Start with the simplest spinlock (test-and-set):

Atomic state: 0 = unlocked, 1 = locked

lock():

while (state.exchange(1, memory_order_acquire) == 1) {

// spin - the exchange returned 1, meaning it was already locked

}

// now we hold the lock

unlock():

state.store(0, memory_order_release);

Why acquire/release?

- Acquire on lock: Subsequent reads see all writes before the previous unlock

- Release on unlock: All our writes are visible to the next thread that acquires

Problems with simple spinlock:

- Unfair: A thread might never get the lock

- Cache-thrashing: exchange() invalidates cache line on all cores

- Wastes CPU: Spinning burns cycles

Improvements to implement:

- Test-and-test-and-set: Read with relaxed ordering first; only do exchange if unlocked

- Exponential backoff: Wait longer between attempts when contended

- Ticket lock: Fair ordering using two counters (now_serving, next_ticket)

Read-Write Lock is more complex:

State encoding (one approach):

bits 0-30: reader count

bit 31: writer flag

Reader lock:

1. If writer flag is set, spin

2. Atomically increment reader count

3. Double-check writer flag (writer might have snuck in)

Writer lock:

1. Set writer flag (using CAS)

2. Wait for reader count to reach 0

Key questions to answer:

- Why can’t you just use

state++for reader count? (Answer: not atomic by default) - Why is

compare_exchange_weakin a loop? (Answer: spurious failures on some architectures) - What’s the difference between

exchangeandcompare_exchange? (Answer: unconditional vs conditional) - Why does the RW lock need to double-check? (Answer: TOCTOU race)

Learning milestones:

- Simple spinlock works → You understand atomic exchange

- Backoff reduces contention → You understand cache effects

- Ticket lock is fair → You understand fairness vs performance tradeoff

- RW lock works correctly → You understand complex atomic state machines

- You choose mutex over spinlock for most cases → You truly understand the tradeoffs

Project 5: Lock-Free Stack

- File: LEARN_CPP_CONCURRENCY_AND_PARALLELISM.md

- Main Programming Language: C++

- Alternative Programming Languages: C, Rust

- Coolness Level: Level 5: Pure Magic (Super Cool)

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 4: Expert

- Knowledge Area: Lock-Free Data Structures

- Software or Tool: Lock-Free Container Library

- Main Book: “C++ Concurrency in Action, Second Edition” by Anthony Williams

What you’ll build: A lock-free stack (LIFO) supporting concurrent push and pop operations, correctly handling the ABA problem using hazard pointers or epoch-based reclamation.

Why it teaches lock-free programming: Lock-free structures are the pinnacle of concurrent programming. You must reason about every possible interleaving of operations. This project will permanently change how you think about shared data.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Atomic pointer updates with CAS → maps to understanding lock-free algorithms

- The ABA problem → maps to understanding why naive CAS fails

- Safe memory reclamation → maps to hazard pointers or epoch-based reclamation

- Memory ordering for correctness → maps to deep understanding of acquire/release

- Testing concurrent code → maps to stress testing and formal verification

Key Concepts:

- Lock-Free Stack: “C++ Concurrency in Action” Chapter 7.2 - Anthony Williams

- The ABA Problem: “C++ Concurrency in Action” Chapter 7.2.3 - Anthony Williams

- Hazard Pointers: “C++ Concurrency in Action” Chapter 7.2.4 - Anthony Williams

- Memory Reclamation: ModernesCpp - “A Lock-Free Stack”

Difficulty: Expert Time estimate: 2-4 weeks Prerequisites: Project 4 completed. Strong understanding of atomics and memory ordering. Familiarity with pointer manipulation.

Real world outcome:

$ ./lockfree_stack_test

Basic operations test:

Push 1000 items: ✓

Pop 1000 items (LIFO order): ✓

Pop from empty stack returns nullopt: ✓

Concurrent stress test (8 threads, 100K ops each):

Total pushes: 400,000

Total pops: 400,000

Final stack size: 0

No lost items: ✓

No duplicate pops: ✓

No use-after-free: ✓ (AddressSanitizer clean)

ABA problem test:

Simulating ABA scenario...

Hazard pointers prevented use-after-free: ✓

Performance comparison:

Lock-free stack: 2.1M ops/sec

Mutex-protected stack: 0.8M ops/sec

std::stack (single-threaded): 15M ops/sec

Memory reclamation stats:

Nodes allocated: 400,000

Nodes reclaimed: 400,000

Memory leak: 0 bytes ✓

Implementation Hints:

The basic lock-free push (without memory reclamation):

struct Node {

T data;

Node* next;

};

std::atomic<Node*> head;

void push(T value) {

Node* new_node = new Node{value, nullptr};

new_node->next = head.load(memory_order_relaxed);

while (!head.compare_exchange_weak(new_node->next, new_node,

memory_order_release,

memory_order_relaxed)) {

// CAS failed, new_node->next was updated to current head

// Loop will retry with correct value

}

}

The basic lock-free pop (where the problems begin):

T* pop() {

Node* old_head = head.load(memory_order_acquire);

while (old_head &&

!head.compare_exchange_weak(old_head, old_head->next,

memory_order_release,

memory_order_relaxed)) {

// CAS failed, old_head updated to current head

}

if (!old_head) return nullptr;

T* result = &old_head->data;

// DANGER: When can we delete old_head?

return result;

}

The ABA Problem:

Thread 1: reads head = A, gets A->next = B

Thread 1: (preempted)

Thread 2: pops A

Thread 2: pops B

Thread 2: pushes new node that reuses A's address!

Thread 2: pushes C

Stack: A(new) -> C -> ...

Thread 1: resumes, does CAS(A, B) - SUCCEEDS because head is still "A"!

Stack: B -> ??? (B was already freed!)

Solutions to implement:

- Reference counting: Each node tracks how many threads are accessing it

- Hazard pointers: Each thread publishes which nodes it’s currently accessing

- Epoch-based reclamation: Nodes freed in an “epoch” can only be reclaimed when all threads have moved past that epoch

Start with hazard pointers (simpler to understand):

- Global array of “hazard pointer” slots (one per thread)

- Before dereferencing a pointer, publish it to your slot

- Before freeing a node, check all slots—if anyone’s using it, defer deletion

- Periodically scan deferred list and free nodes no longer hazardous

Testing is crucial:

- Use ThreadSanitizer to detect data races

- Use AddressSanitizer to detect use-after-free

- Run stress tests with many threads

- Consider formal verification tools (like CDSChecker)

Learning milestones:

- Basic push/pop works single-threaded → You understand the CAS loop

- Concurrent push/pop works (ignoring memory) → You understand the algorithm

- You can explain the ABA problem → You understand why naive solutions fail

- Hazard pointers prevent ABA → You understand memory reclamation

- Stress tests pass with sanitizers → You’ve built a correct lock-free structure

Project 6: Lock-Free MPMC Queue

- File: LEARN_CPP_CONCURRENCY_AND_PARALLELISM.md

- Main Programming Language: C++

- Alternative Programming Languages: C, Rust

- Coolness Level: Level 5: Pure Magic (Super Cool)

- Business Potential: 4. The “Open Core” Infrastructure

- Difficulty: Level 5: Master

- Knowledge Area: Advanced Lock-Free / High-Performance Systems

- Software or Tool: Lock-Free Queue Library

- Main Book: “C++ Concurrency in Action, Second Edition” by Anthony Williams

What you’ll build: A bounded, lock-free, multi-producer multi-consumer (MPMC) queue with high throughput, used as the communication backbone in concurrent systems.

Why it teaches advanced concurrency: The MPMC queue is the “final boss” of lock-free data structures. It requires coordinating multiple writers and multiple readers without locks. Every major concurrent runtime (Tokio, Go scheduler, TBB) has one at its core.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Coordinating multiple producers → maps to index allocation with atomics

- Coordinating multiple consumers → maps to preventing duplicate consumption

- Bounded buffer wraparound → maps to modular arithmetic with atomics

- Detecting empty/full conditions → maps to careful state encoding

- Achieving high throughput → maps to cache-friendly design

Key Concepts:

- Lock-Free Queue: “C++ Concurrency in Action” Chapter 7.3 - Anthony Williams

- MPMC Queue Design: Folly MPMCQueue

- False Sharing: “C++ Concurrency in Action” Chapter 8.2.2 - Anthony Williams

- Bounded Queues: rigtorp/MPMCQueue

Difficulty: Master Time estimate: 3-4 weeks Prerequisites: Project 5 completed. Deep understanding of memory ordering. Familiarity with cache architecture.

Real world outcome:

$ ./mpmc_queue_benchmark

Queue Configuration:

Capacity: 65536 slots

Slot size: 64 bytes (cache-line aligned)

Producers: 4

Consumers: 4

Throughput test (10 seconds):

Total items transferred: 89,000,000

Throughput: 8.9M items/second

Avg latency: 450ns (producer enqueue to consumer dequeue)

P99 latency: 1.2μs

Comparison:

std::queue + std::mutex: 1.2M items/second

Boost.Lockfree MPMC: 7.5M items/second

Our implementation: 8.9M items/second ✓

Stress test (vary producer/consumer ratios):

1P/4C: 3.2M items/sec (consumer-bound)

4P/1C: 3.1M items/sec (producer-bound)

4P/4C: 8.9M items/sec (balanced)

8P/8C: 12.1M items/sec (scales with cores)

Correctness tests:

All items delivered exactly once: ✓

FIFO order per-producer: ✓

No deadlocks after 1 hour: ✓

Implementation Hints:

The classic bounded MPMC design uses a ring buffer with per-slot sequence numbers:

struct Slot {

std::atomic<size_t> sequence; // Used for synchronization

T data;

char padding[CACHE_LINE - sizeof(sequence) - sizeof(T)];

};

std::vector<Slot> buffer; // Size must be power of 2

std::atomic<size_t> enqueue_pos;

std::atomic<size_t> dequeue_pos;

The sequence number trick:

- Each slot has a sequence number

- For position P in buffer, the sequence tells us what operation is valid

sequence == P: Slot is ready for producer at position Psequence == P + 1: Slot is ready for consumer at position P- If sequence is wrong, that operation must wait

Producer (enqueue):

1. pos = enqueue_pos.fetch_add(1) // Claim a position

2. slot = &buffer[pos & mask]

3. Wait until slot->sequence == pos // Slot is ready

4. slot->data = value

5. slot->sequence.store(pos + 1) // Mark for consumer

Consumer (dequeue):

1. pos = dequeue_pos.fetch_add(1) // Claim a position

2. slot = &buffer[pos & mask]

3. Wait until slot->sequence == pos + 1 // Data is ready

4. value = slot->data

5. slot->sequence.store(pos + mask + 1) // Wrap around for next producer

Why this works:

- The sequence number acts as a “turn” indicator

- Only the correct producer/consumer can proceed

- No ABA problem because positions only increase

Critical optimizations:

- Cache-line padding: Each slot should be on its own cache line

- Power-of-2 size: Enables fast modular arithmetic with bitwise AND

- Separate head/tail cache lines: Prevents false sharing

- Backoff on contention: Don’t spin tightly when queue is full/empty

Memory ordering considerations:

sequence.load(acquire): Need to see data written before sequence updatesequence.store(release): Make data visible before signalingfetch_add(relaxed): Just need atomicity, ordering comes from sequence

Learning milestones:

- Single-producer single-consumer works → You understand the basic algorithm

- MPMC works correctly → You understand sequence number synchronization

- Cache-line alignment helps performance → You understand false sharing

- Throughput scales with cores → You understand contention minimization

- Performance beats std::mutex version by 5x+ → You’ve built a high-performance primitive

Project 7: Parallel Image Processor

- File: LEARN_CPP_CONCURRENCY_AND_PARALLELISM.md

- Main Programming Language: C++

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Go

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 2. The “Micro-SaaS / Pro Tool”

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Parallel Algorithms / STL Execution Policies

- Software or Tool: Image Processing Tool

- Main Book: “C++ Concurrency in Action, Second Edition” by Anthony Williams

What you’ll build: An image processing pipeline that uses C++17 parallel algorithms (std::execution::par) to apply filters, transformations, and effects across multiple cores with minimal custom threading code.

Why it teaches parallel algorithms: C++17 parallel algorithms let you parallelize with a single parameter change. But understanding when they help (and when they hurt!) requires understanding the underlying parallel execution model.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Choosing the right execution policy → maps to understanding par vs par_unseq

- Understanding when parallelism helps → maps to Amdahl’s Law and overhead

- Avoiding iterator invalidation → maps to parallel algorithm requirements

- Composing parallel operations → maps to understanding synchronization points

Key Concepts:

- Parallel Algorithms: “C++ Concurrency in Action” Chapter 10 - Anthony Williams

- Execution Policies: cppreference.com std::execution documentation

- Image Processing Basics: “Computer Graphics from Scratch” Chapter on Color - Gabriel Gambetta

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 1-2 weeks Prerequisites: Projects 1-2 completed. Basic understanding of image formats (PPM is easiest). Familiarity with STL algorithms.

Real world outcome:

$ ./parallel_image --input photo.ppm --output processed.ppm

Loading photo.ppm (4096x3072, 12.6 megapixels)...

Loaded in 0.8s

Applying filters with std::execution::par:

1. Brightness adjustment (+20%)

Sequential: 245ms

Parallel: 42ms

Speedup: 5.8x ✓

2. Gaussian blur (5x5 kernel)

Sequential: 1,840ms

Parallel: 285ms

Speedup: 6.5x ✓

3. Edge detection (Sobel)

Sequential: 892ms

Parallel: 138ms

Speedup: 6.5x ✓

4. Color quantization (16 colors)

Sequential: 3,200ms

Parallel: 520ms

Speedup: 6.2x ✓

Total processing time:

Sequential: 6,177ms

Parallel: 985ms

Overall speedup: 6.3x on 8 cores

Saved processed.ppm

$ ./parallel_image --benchmark --small

Loading tiny.ppm (64x64, 4096 pixels)...

Warning: For small images, parallel overhead exceeds benefits

Sequential: 0.8ms

Parallel: 2.1ms (SLOWER due to thread overhead!)

Implementation Hints:

Using parallel algorithms is syntactically simple:

#include <execution>

#include <algorithm>

// Sequential (traditional)

std::transform(pixels.begin(), pixels.end(), output.begin(), adjust_brightness);

// Parallel

std::transform(std::execution::par, pixels.begin(), pixels.end(), output.begin(), adjust_brightness);

// Parallel + vectorized (SIMD)

std::transform(std::execution::par_unseq, pixels.begin(), pixels.end(), output.begin(), adjust_brightness);

Image representation:

struct Pixel { uint8_t r, g, b; };

std::vector<Pixel> image; // Contiguous memory = cache-friendly

// Access pixel at (x, y):

Pixel& p = image[y * width + x];

Filters to implement:

- Point operations (per-pixel, embarrassingly parallel):

- Brightness:

p.r = clamp(p.r + delta, 0, 255) - Contrast:

p.r = clamp((p.r - 128) * factor + 128, 0, 255) - Invert:

p.r = 255 - p.r

- Brightness:

- Neighborhood operations (need care with boundaries):

- Blur: Average of surrounding pixels

- Edge detection: Gradient magnitude

- Sharpen: Center minus neighbors

- Global operations (need synchronization):

- Histogram equalization

- Color quantization

Key insight for neighborhood operations:

- You can’t modify pixels in-place when reading neighbors

- Use double-buffering: read from input, write to output

- Or parallelize over rows (each row reads from adjacent rows, writes to same row)

When parallel helps vs hurts:

- Helps: Large images, expensive per-pixel operations

- Hurts: Small images (thread overhead > work), operations with synchronization

- Measure, don’t assume!

Architecture approach:

- Load image into vector of Pixels

- Apply filters in sequence, each using

std::transformwithpar - For convolution, parallelize over rows:

std::for_each(par, row_iterators...) - Save result

Learning milestones:

- Sequential filters work correctly → You understand the image algorithms

- Adding par gives speedup → You understand parallel execution

- You measure when par helps → You understand overhead tradeoffs

- Blur/edge detection work in parallel → You understand neighborhood parallelization

- You predict speedup based on cores → You understand Amdahl’s Law

Project 8: Parallel Sort Benchmark Suite

- File: LEARN_CPP_CONCURRENCY_AND_PARALLELISM.md

- Main Programming Language: C++

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Java, Go

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Parallel Algorithms / Performance Analysis

- Software or Tool: Benchmarking Tool

- Main Book: “C++ Concurrency in Action, Second Edition” by Anthony Williams

What you’ll build: A comprehensive benchmark comparing sequential sort, parallel sort with different policies, and custom parallel merge-sort, analyzing how input size, distribution, and hardware affect performance.

Why it teaches execution policies: Sorting is the canonical parallel algorithm. By implementing your own parallel sort and comparing it to the standard library, you’ll understand work partitioning, merge strategies, and the limits of parallelism.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Understanding when parallelism helps sorting → maps to overhead vs work tradeoff

- Implementing parallel merge sort → maps to divide-and-conquer parallelism

- Accurate benchmarking → maps to statistical analysis and controlling for noise

- Input distribution effects → maps to understanding algorithm characteristics

Key Concepts:

- Parallel Sort: “C++ Concurrency in Action” Chapter 10.3 - Anthony Williams

- Merge Sort Parallelization: “Algorithms, Fourth Edition” Chapter 2.2 - Sedgewick & Wayne

- Benchmarking Best Practices: Google Benchmark documentation

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 1 week Prerequisites: Project 7 completed. Understanding of sorting algorithms (merge sort, quicksort). Familiarity with Big-O analysis.

Real world outcome:

$ ./sort_benchmark --full

System: 8 cores, 16 threads (hyperthreading)

Data types: int64_t

Distributions: random, sorted, reverse, nearly-sorted, many-duplicates

=== 1,000 elements (small) ===

Algorithm Random Sorted Reverse Nearly Dupes

std::sort 0.02ms 0.01ms 0.01ms 0.01ms 0.02ms

std::sort(par) 0.15ms 0.12ms 0.13ms 0.12ms 0.14ms

Custom parallel 0.18ms 0.14ms 0.15ms 0.13ms 0.17ms

Winner: std::sort (parallel overhead not worth it)

=== 1,000,000 elements (medium) ===

Algorithm Random Sorted Reverse Nearly Dupes

std::sort 68ms 8ms 9ms 12ms 45ms

std::sort(par) 12ms 3ms 3ms 4ms 9ms

Custom parallel 14ms 4ms 4ms 5ms 11ms

Winner: std::sort(par), 5.7x speedup

=== 100,000,000 elements (large) ===

Algorithm Random Sorted Reverse Nearly Dupes

std::sort 8.2s 0.9s 1.0s 1.3s 5.1s

std::sort(par) 1.3s 0.15s 0.16s 0.21s 0.85s

std::sort(par_unseq) 1.2s 0.14s 0.15s 0.20s 0.81s

Custom parallel 1.4s 0.18s 0.18s 0.24s 0.92s

Winner: std::sort(par_unseq), 6.8x speedup

=== Analysis ===

- Parallel overhead: ~0.1ms (breaks even at ~50K elements)

- Speedup scales sub-linearly: 5-7x on 8 cores (not 8x)

- Pre-sorted data: Faster for all algorithms

- par_unseq: Marginal improvement (SIMD helps comparison)

- Custom implementation: Within 10% of std library (good!)

Implementation Hints:

Parallel merge sort structure:

parallel_merge_sort(array, depth):

if (array.size < THRESHOLD or depth == 0):

return sequential_sort(array)

mid = array.size / 2

// Sort halves in parallel

future left = async(parallel_merge_sort, left_half, depth-1)

parallel_merge_sort(right_half, depth-1) // Do one half in current thread

left.wait() // Wait for other half

merge(left_half, right_half)

Key parameters:

- THRESHOLD: Below this size, don’t parallelize (typically 10K-100K)

- depth: Limit recursion to avoid spawning too many tasks

The merge step is tricky to parallelize:

- Simple: Sequential merge (limits speedup)

- Better: Parallel merge using divide-and-conquer

- Even better: Let the runtime handle it with

std::inplace_merge(par, ...)

Benchmarking correctly:

- Warm up: Run a few iterations before measuring

- Multiple runs: Report median and standard deviation

- Prevent optimization: Use

benchmark::DoNotOptimize(result) - Fresh data: Re-generate input for each run (sorted data is faster!)

- Flush cache: Consider cache effects between runs

Input distributions to test:

- Random: Typical case

- Sorted: Best case for adaptive algorithms

- Reverse sorted: Worst case for naive quicksort

- Nearly sorted: Tests adaptivity

- Many duplicates: Tests partition quality

Questions to investigate:

- At what size does parallel beat sequential?

- How does speedup change with core count?

- Which distribution benefits most from parallelism?

- Does par_unseq ever beat par significantly?

Learning milestones:

- Sequential sort works → You understand the algorithm

- Parallel version works → You understand task decomposition

- You find the break-even point → You understand overhead

- Custom matches std library → You’ve implemented efficiently

- You can predict speedup → You understand parallel scaling

Project 9: Coroutine Generator Library

- File: LEARN_CPP_CONCURRENCY_AND_PARALLELISM.md

- Main Programming Language: C++

- Alternative Programming Languages: Python (for comparison), Rust

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 3. The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 4: Expert

- Knowledge Area: C++20 Coroutines / Lazy Evaluation

- Software or Tool: Coroutine Library

- Main Book: “C++ Concurrency in Action, Second Edition” by Anthony Williams

What you’ll build: A Generator<T> type that lets you write Python-like generator functions in C++ using co_yield, producing values lazily on demand.

Why it teaches coroutines: Generators are the simplest coroutine pattern. By implementing one, you’ll understand the machinery: promise types, coroutine handles, awaiters, and suspension points. This is the foundation for async/await.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Understanding the coroutine machinery → maps to promise_type requirements

- Implementing suspend/resume → maps to coroutine_handle and suspension

- Managing coroutine lifetime → maps to RAII for coroutine resources

- Making it feel natural → maps to iterator interface and range-for

Key Concepts:

- Coroutine Basics: Stanford Tutorial on C++20 Coroutines

- Promise Type: cppreference.com coroutines documentation

- Generator Pattern: ModernesCpp - “C++20 Coroutines”

Difficulty: Expert Time estimate: 2-3 weeks Prerequisites: Solid C++ fundamentals. No prior coroutine experience needed (we start from scratch).

Real world outcome:

// User code - looks like Python!

Generator<int> fibonacci(int n) {

int a = 0, b = 1;

for (int i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

co_yield a;

std::tie(a, b) = std::make_tuple(b, a + b);

}

}

Generator<std::string> lines(std::istream& file) {

std::string line;

while (std::getline(file, line)) {

co_yield line;

}

}

int main() {

// Range-for works!

for (int fib : fibonacci(10)) {

std::cout << fib << " "; // 0 1 1 2 3 5 8 13 21 34

}

// Lazy evaluation - only reads lines as needed

std::ifstream file("huge.txt");

for (const auto& line : lines(file)) {

if (line.contains("ERROR")) {

std::cout << line << "\n";

}

}

// Can manually iterate too

auto gen = fibonacci(5);

while (gen.next()) {

std::cout << gen.value() << "\n";

}

}

$ ./generator_demo

Fibonacci(10): 0 1 1 2 3 5 8 13 21 34

Found 3 error lines in huge.txt (read 1.2GB, processed 50M lines)

Implementation Hints:

The coroutine machinery requires three cooperating types:

- **Generator

**: What the user sees (return type of coroutine) - promise_type: Tells the compiler how to manage the coroutine

- iterator: Enables range-for (optional but nice)

Core structure:

template<typename T>

class Generator {

public:

// The promise_type is how the compiler knows this is a coroutine return type

struct promise_type {

T current_value;

// Called when coroutine starts

Generator get_return_object() {

return Generator{std::coroutine_handle<promise_type>::from_promise(*this)};

}

// Suspend immediately on creation (lazy)

std::suspend_always initial_suspend() { return {}; }

// Suspend on completion (so we can detect end)

std::suspend_always final_suspend() noexcept { return {}; }

// Handle co_yield

std::suspend_always yield_value(T value) {

current_value = std::move(value);

return {}; // Suspend after storing value

}

void return_void() {}

void unhandled_exception() { std::terminate(); }

};

private:

std::coroutine_handle<promise_type> handle;

public:

explicit Generator(std::coroutine_handle<promise_type> h) : handle(h) {}

~Generator() { if (handle) handle.destroy(); }

// Move-only (coroutine ownership)

Generator(Generator&& other) noexcept : handle(std::exchange(other.handle, {})) {}

bool next() {

handle.resume();

return !handle.done();

}

T& value() { return handle.promise().current_value; }

};

For range-for support, add an iterator:

class iterator {

std::coroutine_handle<promise_type> handle;

public:

iterator& operator++() { handle.resume(); return *this; }

T& operator*() { return handle.promise().current_value; }

bool operator!=(std::default_sentinel_t) { return !handle.done(); }

};

iterator begin() { handle.resume(); return iterator{handle}; }

std::default_sentinel_t end() { return {}; }

Key concepts to understand:

- Why

std::suspend_always?: Tells coroutine to pause at that point - Why

coroutine_handle?: It’s a pointer to the suspended coroutine state - Why

promise_typeinside Generator?: Compiler looks for it there by convention - Why

from_promise?: Creates handle from promise reference (they’re connected) - Why call

destroy()?: Coroutine state is heap-allocated, needs cleanup

Testing your implementation:

- Simple generator that yields 1, 2, 3

- Infinite generator (Fibonacci)

- Generator that takes parameters

- Generator over file (test laziness)

- Exception handling in generator

Learning milestones:

- Minimal generator compiles → You understand promise_type basics

- co_yield works and values are retrieved → You understand suspension

- Range-for works → You understand the iterator protocol

- Lazy evaluation confirmed → You understand when code runs

- No memory leaks → You understand coroutine lifetime

Project 10: Async Task Framework

- File: LEARN_CPP_CONCURRENCY_AND_PARALLELISM.md

- Main Programming Language: C++

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust (async/await), JavaScript (for comparison)

- Coolness Level: Level 5: Pure Magic (Super Cool)

- Business Potential: 4. The “Open Core” Infrastructure

- Difficulty: Level 5: Master

- Knowledge Area: C++20 Coroutines / Async Runtime

- Software or Tool: Async Framework

- Main Book: “C++ Concurrency in Action, Second Edition” by Anthony Williams

What you’ll build: An async task system with Task<T> coroutines, co_await support, and a basic scheduler that runs coroutines to completion, similar to a simplified Tokio or cppcoro.

Why it teaches advanced coroutines: While generators are simple (linear flow with yields), async tasks involve waiting for other tasks, complex suspension, and integration with an executor. This is production async programming.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Implementing awaitable types → maps to the awaiter protocol (ready/suspend/resume)

- Building a scheduler → maps to managing runnable coroutines

- Task composition → maps to co_await chaining

- Error handling → maps to exception propagation across suspension

- Thread integration → maps to running tasks on a thread pool

Key Concepts:

- Awaitable and Awaiter: Stanford Coroutine Tutorial

- cppcoro Library: ModernesCpp - “C++20 Coroutines with cppcoro”

- Async Runtime Design: Dima Korolev - “C++20 Coroutines”

Difficulty: Master Time estimate: 4-6 weeks Prerequisites: Project 9 completed. Project 3 (thread pool) helpful. Strong understanding of coroutine machinery.

Real world outcome:

// User code - looks like modern async/await!

Task<std::string> fetch_data(std::string url) {

auto connection = co_await async_connect(url);

auto response = co_await connection.get("/api/data");

co_return response.body();

}

Task<int> compute_result(int x) {

co_await sleep(100ms); // Non-blocking!

co_return x * 2;

}

Task<void> main_task() {

// Run tasks concurrently

auto [data, result] = co_await when_all(

fetch_data("https://api.example.com"),

compute_result(21)

);

std::cout << "Data: " << data << ", Result: " << result << "\n";

}

int main() {

// Run the async runtime

Runtime runtime(4); // 4 threads

runtime.block_on(main_task());

}

$ ./async_demo

[Runtime] Starting with 4 worker threads

[Worker-1] Running main_task

[Worker-2] Running fetch_data (spawned)

[Worker-3] Running compute_result (spawned)

[Worker-3] compute_result sleeping...

[Worker-2] fetch_data: connected to api.example.com

[Worker-3] compute_result done: 42

[Worker-2] fetch_data done: {"status": "ok"}

[Worker-1] main_task resuming with results

Data: {"status": "ok"}, Result: 42

[Runtime] All tasks complete

Implementation Hints:

The awaiter protocol (what co_await expects):

struct MyAwaiter {

// Called first - should we suspend?

bool await_ready() { return false; } // false = yes, suspend

// Called when suspending - what to do with the waiting coroutine?

void await_suspend(std::coroutine_handle<> waiting) {

// Schedule work, store waiting handle, etc.

// When work is done, call waiting.resume()

}

// Called when resuming - what value to return?

int await_resume() { return 42; } // This is the result of co_await

};

Task structure (simplified):

template<typename T>

class Task {

public:

struct promise_type {

std::optional<T> result;

std::coroutine_handle<> waiting; // Who's waiting for us?

Task get_return_object() { ... }

std::suspend_always initial_suspend() { return {}; } // Lazy

auto final_suspend() noexcept {

// When we finish, resume whoever was waiting

struct FinalAwaiter {

bool await_ready() noexcept { return false; }

std::coroutine_handle<> await_suspend(std::coroutine_handle<promise_type> me) noexcept {

if (me.promise().waiting)

return me.promise().waiting; // Resume waiter

return std::noop_coroutine();

}

void await_resume() noexcept {}

};

return FinalAwaiter{};

}

void return_value(T value) { result = std::move(value); }

};

// Make Task awaitable

auto operator co_await() {

struct Awaiter {

std::coroutine_handle<promise_type> task;

bool await_ready() { return task.done(); }

std::coroutine_handle<> await_suspend(std::coroutine_handle<> waiting) {

task.promise().waiting = waiting;

return task; // Start running the task

}

T await_resume() { return *task.promise().result; }

};

return Awaiter{handle};

}

};

The scheduler/runtime:

- Queue of ready-to-run coroutines

- Worker threads that pop and resume coroutines

- When a coroutine suspends, it should schedule something else

- When a coroutine finishes, it resumes its waiter

Building blocks to implement:

Task<T>: Basic awaitable tasksleep(duration): Timer-based awaitablewhen_all(tasks...): Wait for multiple tasksspawn(task): Launch task without waitingblock_on(task): Run until task completes (entry point)

Challenges you’ll face:

- Where do suspended coroutines live? (Heap, managed by Task)

- How does sleep work without blocking? (Timer queue + thread)

- How do you handle exceptions? (Store in promise, rethrow on resume)

- How do you avoid deadlocks? (Careful about what holds what)

Learning milestones:

- Simple Task completes → You understand the promise/awaiter dance

- co_await chains work → You understand continuation passing

- Multi-threaded executor works → You understand scheduling

- when_all works → You understand complex composition

- No deadlocks or races → You’ve built a correct runtime

Project 11: Async File I/O Library

- File: LEARN_CPP_CONCURRENCY_AND_PARALLELISM.md

- Main Programming Language: C++

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Go

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 3. The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 4: Expert

- Knowledge Area: Coroutines / I/O / System Programming

- Software or Tool: Async I/O Library

- Main Book: “The Linux Programming Interface” by Michael Kerrisk

What you’ll build: An async file I/O library where read/write operations are non-blocking coroutines, backed by a thread pool for actual I/O (simulating io_uring or Windows IOCP patterns).

Why it teaches practical coroutines: This connects coroutines to real work. You’ll see why async I/O matters and how coroutines make it usable. This is how production async runtimes (Tokio, ASIO) actually work.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Bridging async and sync APIs → maps to offloading work to threads

- File handle management → maps to RAII and async lifetimes

- Buffered I/O → maps to performance optimization

- Error handling → maps to exception propagation in coroutines

Key Concepts:

- Async I/O Patterns: “The Linux Programming Interface” Chapter 63 - Michael Kerrisk

- Coroutine I/O: Task

from Project 10 - Thread Pool Integration: Project 3

Difficulty: Expert Time estimate: 2-3 weeks Prerequisites: Project 10 completed. Familiarity with file I/O syscalls.

Real world outcome:

Task<void> process_large_file(std::string path) {

auto file = co_await async_open(path, OpenMode::Read);

std::vector<char> buffer(1024 * 1024); // 1MB buffer

size_t total = 0;

while (true) {

size_t bytes = co_await file.read(buffer);

if (bytes == 0) break; // EOF

total += bytes;

// Process buffer...

}

std::cout << "Processed " << total << " bytes\n";

}

Task<void> copy_file(std::string src, std::string dst) {

auto in = co_await async_open(src, OpenMode::Read);

auto out = co_await async_open(dst, OpenMode::Write | OpenMode::Create);

std::vector<char> buffer(64 * 1024);

while (true) {

size_t bytes = co_await in.read(buffer);

if (bytes == 0) break;

co_await out.write(std::span(buffer.data(), bytes));

}

}

int main() {

Runtime runtime(4);

runtime.block_on(copy_file("large.bin", "copy.bin"));

}

$ ./async_file_demo

Copying 10GB file...

[Worker-1] Starting copy_file

[Worker-2] async_read: queued

[Worker-3] async_read: completed 65536 bytes

[Worker-2] async_write: queued

[Worker-1] async_write: completed 65536 bytes

... (continues, interleaving reads and writes)

Copy completed in 45 seconds

Throughput: 227 MB/s

Comparison:

Synchronous copy: 52 seconds

Async with overlap: 45 seconds (15% faster, I/O overlapped)

Implementation Hints:

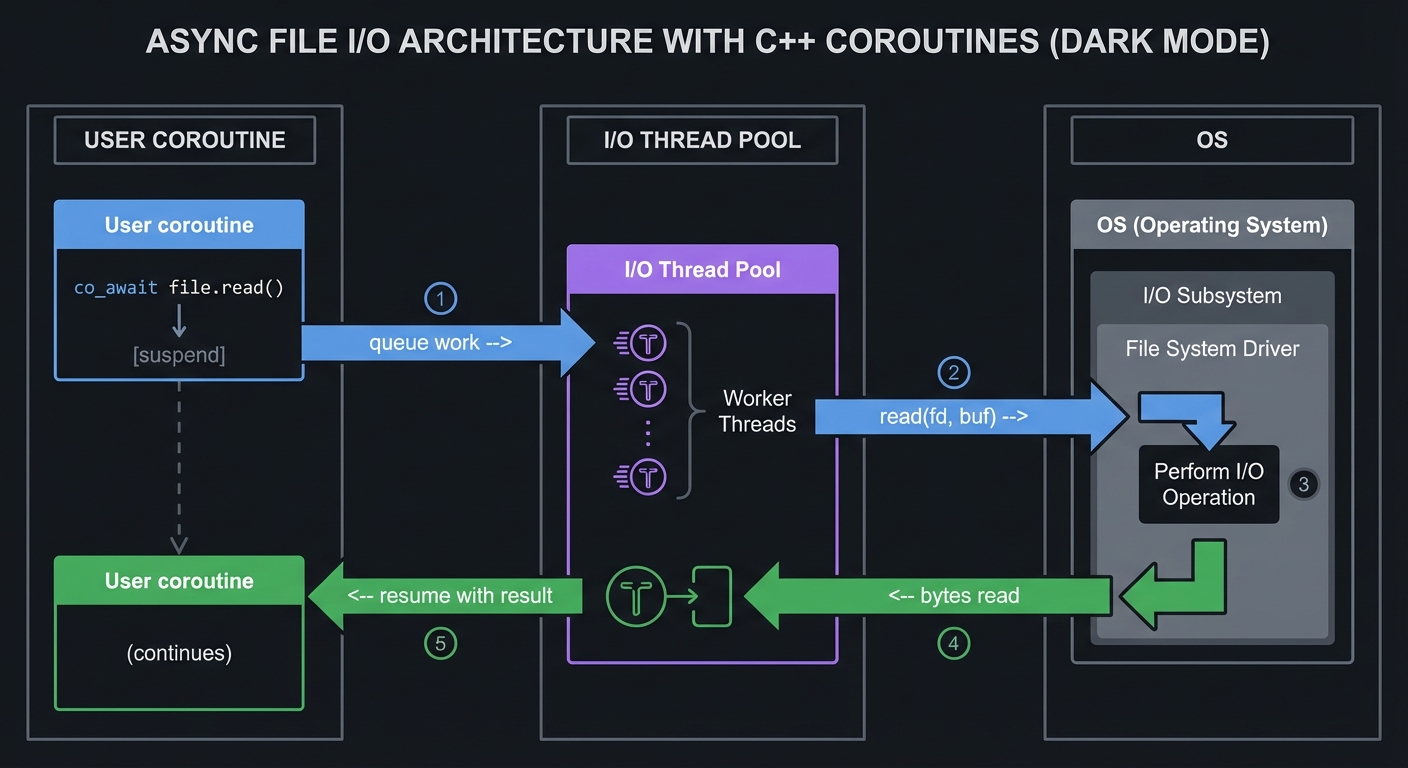

Architecture:

User coroutine I/O Thread Pool OS

| | |

co_await file.read() | |

| | |

[suspend] ------> queue work -->| |

| +----> read(fd, buf) -->|

| |<---- bytes read <-----+

|<----- resume with result --+

|

(continues)

The async file handle:

class AsyncFile {

int fd;

Runtime& runtime; // Reference to executor

public:

Task<size_t> read(std::span<char> buffer) {

// Create an awaitable that offloads to thread pool

return runtime.spawn_blocking([this, buf = buffer]() {

return ::read(fd, buf.data(), buf.size());

});

}

Task<size_t> write(std::span<const char> buffer) {

return runtime.spawn_blocking([this, buf = buffer]() {

return ::write(fd, buf.data(), buf.size());

});

}

};

Key insight: spawn_blocking queues work to a thread pool and returns a Task that completes when the work is done.

Implementing spawn_blocking:

template<typename F>

Task<std::invoke_result_t<F>> spawn_blocking(F&& func) {

std::promise<std::invoke_result_t<F>> promise;

auto future = promise.get_future();

thread_pool.submit([func = std::forward<F>(func), promise = std::move(promise)]() mutable {

promise.set_value(func());

});

// Return a Task that awaits the future

co_return co_await make_task_from_future(std::move(future));

}

Advanced improvements:

- io_uring integration (Linux): True async I/O without thread pool overhead

- Readahead: Start next read before current one is processed

- Write buffering: Batch small writes

- Error handling: Map errno to exceptions

Learning milestones:

- Basic read/write coroutines work → You understand thread pool integration

- File copy works → You understand chained I/O

- Overlapped I/O shows speedup → You understand async benefits

- Large files don’t exhaust memory → You understand streaming

- Errors propagate correctly → You understand exception handling in async

Project 12: SIMD Math Library

- File: LEARN_CPP_CONCURRENCY_AND_PARALLELISM.md

- Main Programming Language: C++

- Alternative Programming Languages: C, Rust

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 3. The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: SIMD / Vectorization / Performance

- Software or Tool: Math Library

- Main Book: “Modern X86 Assembly Language Programming” by Daniel Kusswurm

What you’ll build: A math library using std::experimental::simd (or intrinsics) to perform vectorized operations on arrays—vector addition, dot products, matrix multiplication—with significant speedups over scalar code.

Why it teaches SIMD: SIMD is data parallelism within a single thread. By implementing common operations, you’ll understand when vectorization helps, how memory alignment matters, and how to write portable SIMD code.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Understanding SIMD lane widths → maps to hardware capabilities

- Memory alignment → maps to performance and correctness

- Handling remainders → maps to when array size isn’t a multiple of SIMD width

- Comparing with auto-vectorization → maps to when manual SIMD is worth it

Key Concepts:

- std::simd (experimental): cppreference SIMD library

- SIMD fundamentals: ModernesCpp - “Data-Parallel Types (SIMD)”

- AVX intrinsics: Intel Intrinsics Guide (for comparison)

Difficulty: Advanced Time estimate: 1-2 weeks Prerequisites: Basic understanding of CPU architecture. Familiarity with vectors/matrices. No prior SIMD experience required.

Real world outcome:

$ ./simd_math_benchmark

System: AVX2 supported, 256-bit registers (8 floats per operation)

Vector Addition (1 million floats):

Scalar: 1.2ms

Auto-vectorized: 0.35ms (3.4x faster)

std::simd: 0.31ms (3.9x faster)

Intrinsics: 0.30ms (4.0x faster)

Dot Product (1 million floats):

Scalar: 1.8ms

std::simd: 0.25ms (7.2x faster)

Note: Horizontal add needed at end limits gains

Matrix Multiply (1024x1024 floats):

Scalar: 2,400ms

std::simd: 340ms (7x faster)

BLAS (reference): 85ms (blocked algorithm + SIMD)

RGB to Grayscale (4K image, 8.3M pixels):

Scalar: 28ms

std::simd: 4.2ms (6.7x faster)

$ ./simd_demo

std::simd<float> v1{1.0f, 2.0f, 3.0f, 4.0f, 5.0f, 6.0f, 7.0f, 8.0f};

std::simd<float> v2{8.0f, 7.0f, 6.0f, 5.0f, 4.0f, 3.0f, 2.0f, 1.0f};

auto result = v1 + v2; // {9, 9, 9, 9, 9, 9, 9, 9}

Implementation Hints:

Using std::experimental::simd (GCC 11+):

#include <experimental/simd>

namespace stdx = std::experimental;

void vector_add(float* a, float* b, float* result, size_t n) {

using simd_t = stdx::native_simd<float>; // Best SIMD for this platform

constexpr size_t simd_size = simd_t::size();

size_t i = 0;

// Main loop: process simd_size elements at once

for (; i + simd_size <= n; i += simd_size) {

simd_t va(&a[i], stdx::element_aligned);

simd_t vb(&b[i], stdx::element_aligned);

simd_t vr = va + vb;

vr.copy_to(&result[i], stdx::element_aligned);

}

// Remainder: scalar fallback

for (; i < n; ++i) {

result[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}

}

Key concepts:

native_simd<T>: Uses widest SIMD available (AVX-512: 16 floats, AVX: 8, SSE: 4)fixed_size_simd<T, N>: Specific width (portable behavior)- Memory tags:

element_aligned(any),vector_aligned(for aligned memory)

Operations to implement:

- Vector ops: add, subtract, multiply, divide, fma (fused multiply-add)

- Reductions: sum, min, max, dot product

- Transcendentals: sqrt, sin, cos (check library support)

- Image ops: RGB to grayscale, brightness, blend

Dot product challenge (horizontal addition):

float dot_product(float* a, float* b, size_t n) {

using simd_t = stdx::native_simd<float>;

simd_t sum = 0;

for (size_t i = 0; i + simd_t::size() <= n; i += simd_t::size()) {

simd_t va(&a[i], stdx::element_aligned);

simd_t vb(&b[i], stdx::element_aligned);

sum += va * vb; // Element-wise multiply, then add to running sum

}

// Horizontal add: sum all lanes

return stdx::reduce(sum); // This is the expensive part

}

Alignment matters:

// Aligned allocation

alignas(64) float data[1024]; // 64-byte alignment for AVX-512

// Or runtime:

float* data = std::aligned_alloc(64, 1024 * sizeof(float));

Learning milestones:

- Simple vector add works → You understand basic SIMD usage

- Speedup matches lane width → You understand throughput model

- Remainder handling works → You understand the full algorithm

- Dot product works → You understand horizontal operations

- Your code beats auto-vectorization → You understand when manual SIMD wins

Project 13: Audio DSP with SIMD

- File: LEARN_CPP_CONCURRENCY_AND_PARALLELISM.md

- Main Programming Language: C++

- Alternative Programming Languages: C, Rust

- Coolness Level: Level 5: Pure Magic (Super Cool)

- Business Potential: 2. The “Micro-SaaS / Pro Tool”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: SIMD / Audio Processing / Real-time

- Software or Tool: Audio Effects Processor

- Main Book: “Computer Graphics from Scratch” (for DSP concepts) by Gabriel Gambetta

What you’ll build: Real-time audio effects (EQ, reverb, compression) using SIMD to process multiple samples simultaneously, meeting the strict latency requirements of audio processing.

Why it teaches practical SIMD: Audio processing is one of the most demanding SIMD applications. You have a hard deadline (typically 10ms) and must process thousands of samples. This forces you to optimize every cycle.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Meeting real-time constraints → maps to understanding latency budgets

- Filter implementation → maps to IIR/FIR with SIMD

- Buffer management → maps to avoiding allocations in audio thread

- Multi-channel processing → maps to interleaved vs planar formats

Key Concepts:

- SIMD from Project 12: std::simd

- Audio DSP Basics: The Audio Programmer YouTube channel

- Real-time Constraints: JUCE framework documentation

Difficulty: Advanced Time estimate: 2-3 weeks Prerequisites: Project 12 completed. Basic understanding of audio concepts (samples, sample rate). Familiarity with filters helpful but not required.

Real world outcome:

$ ./audio_dsp --input music.wav --output processed.wav

Input: music.wav

Duration: 3:45 (13,230,000 samples)

Sample rate: 44100 Hz

Channels: 2 (stereo)

Processing chain:

1. Low-shelf EQ (+3dB @ 100Hz)

2. Parametric EQ (-2dB @ 3kHz, Q=1.5)

3. Compressor (threshold=-20dB, ratio=4:1)

4. Limiter (ceiling=-0.3dB)

Performance:

Samples per SIMD op: 8 (AVX)

Time per buffer (512 samples): 0.02ms

Real-time ratio: 580x (could process 580 streams in real-time!)

Comparison:

Scalar processing: 0.15ms per buffer

SIMD processing: 0.02ms per buffer

Speedup: 7.5x

Output saved to processed.wav

$ ./audio_dsp --realtime --device "Built-in Audio"

Real-time mode: Processing live audio

Latency: 11.6ms (512 samples @ 44.1kHz)

Running... Press Ctrl+C to stop

[VU Meter] L: ████████░░ -6dB R: ███████░░░ -8dB

Implementation Hints:

Audio buffer structure:

// Planar format (better for SIMD)

struct AudioBuffer {

std::vector<float> left;

std::vector<float> right;

size_t num_samples;

};

// Interleaved format (common in APIs)

// L0 R0 L1 R1 L2 R2 ...

std::vector<float> interleaved;

Simple gain with SIMD:

void apply_gain(float* samples, size_t n, float gain) {

using simd_t = stdx::native_simd<float>;

simd_t gain_vec = gain; // Broadcast scalar to all lanes

for (size_t i = 0; i + simd_t::size() <= n; i += simd_t::size()) {

simd_t s(&samples[i], stdx::element_aligned);

s *= gain_vec;

s.copy_to(&samples[i], stdx::element_aligned);

}

}

Biquad filter (EQ building block):

y[n] = b0*x[n] + b1*x[n-1] + b2*x[n-2] - a1*y[n-1] - a2*y[n-2]

SIMD challenge: Filters have temporal dependencies (current output depends on previous output). Solutions:

- Process channels in parallel: 8 mono channels = 8 SIMD lanes

- Transposed Direct Form II: Reduces dependencies

- Block processing: Batch independent parts

Compressor (dynamics processing):

void compress(float* samples, size_t n, float threshold, float ratio) {

using simd_t = stdx::native_simd<float>;

simd_t thresh_vec = threshold;

simd_t ratio_vec = ratio;

for (size_t i = 0; i + simd_t::size() <= n; i += simd_t::size()) {

simd_t s(&samples[i], stdx::element_aligned);

simd_t abs_s = stdx::abs(s);

// Where abs > threshold, apply compression

auto mask = abs_s > thresh_vec;

simd_t compressed = thresh_vec + (abs_s - thresh_vec) / ratio_vec;

s = stdx::where(mask, stdx::copysign(compressed, s), s);

s.copy_to(&samples[i], stdx::element_aligned);

}

}

Real-time rules:

- No allocations in the audio callback

- No locks (use lock-free queues for communication)

- No I/O or system calls

- Pre-allocate everything

Learning milestones:

- Load/save WAV files → You understand audio format basics

- Simple gain/fade works → You understand basic SIMD audio

- EQ sounds correct → You understand filter implementation

- Real-time playback works → You understand latency requirements

- SIMD beats scalar by 5x+ → You’ve optimized effectively

Project 14: Real-Time Game Physics with Parallelism

- File: LEARN_CPP_CONCURRENCY_AND_PARALLELISM.md

- Main Programming Language: C++

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, C

- Coolness Level: Level 5: Pure Magic (Super Cool)

- Business Potential: 3. The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 4: Expert

- Knowledge Area: Parallelism / SIMD / Real-time Systems

- Software or Tool: Physics Engine

- Main Book: “Computer Graphics from Scratch” by Gabriel Gambetta

What you’ll build: A particle/rigid body physics simulation using parallel algorithms for broad-phase collision detection, SIMD for narrow-phase, and multi-threaded integration—rendering thousands of objects at 60fps.

Why it teaches integrated parallelism: Game physics combines everything: thread pools for parallelism, SIMD for math, lock-free structures for communication, and real-time constraints. It’s the ultimate test.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Parallel collision broad-phase → maps to spatial partitioning with parallelism

- SIMD physics integration → maps to vectorized Euler/Verlet

- Thread-safe object access → maps to partitioning work to avoid races

- Meeting frame budgets → maps to profiling and optimization

Key Concepts:

- Parallel Algorithms: From Projects 7-8

- SIMD: From Projects 12-13

- Game Physics: “Game Physics Engine Development” by Ian Millington

Difficulty: Expert Time estimate: 4-6 weeks Prerequisites: Projects 7-8 and 12-13 completed. Basic understanding of physics (velocity, acceleration, collision). Linear algebra helpful.

Real world outcome:

$ ./physics_demo

Physics Simulation Configuration:

Particles: 100,000

Rigid bodies: 1,000

Collision detection: Spatial hashing + SAT

Integration: Verlet (SIMD)

Threads: 8

Frame breakdown (target: 16.67ms for 60fps):

Broad-phase collision: 2.1ms (parallel spatial hash)

Narrow-phase collision: 3.8ms (SIMD SAT)

Constraint resolution: 1.5ms (parallel Jacobi)

Integration: 0.8ms (SIMD Verlet)

Total physics: 8.2ms ✓ (well under budget)

Performance scaling:

1 thread: 45ms per frame (22 fps)

4 threads: 12ms per frame (83 fps)

8 threads: 8ms per frame (125 fps)

Efficiency: 70% (good for physics workload)

$ ./physics_demo --visual

[Opens window showing 100,000 particles bouncing]

Average FPS: 60 (vsync limited)

Physics time: 8ms, Render time: 2ms, Idle: 6ms

Implementation Hints:

Structure of Arrays (SoA) for SIMD-friendly layout:

// Array of Structures (AoS) - cache unfriendly for SIMD

struct Particle {

vec3 position, velocity, force;

};

std::vector<Particle> particles; // [p0, p1, p2, ...]

// Structure of Arrays (SoA) - SIMD friendly

struct ParticleSystem {

std::vector<float> pos_x, pos_y, pos_z;

std::vector<float> vel_x, vel_y, vel_z;

std::vector<float> force_x, force_y, force_z;

size_t count;

};

SIMD Verlet integration:

void integrate(ParticleSystem& ps, float dt) {

using simd_t = stdx::native_simd<float>;

simd_t dt_vec = dt;

simd_t dt2_half = dt * dt * 0.5f;

for (size_t i = 0; i + simd_t::size() <= ps.count; i += simd_t::size()) {

// x += v*dt + 0.5*a*dt^2

simd_t x(&ps.pos_x[i], stdx::element_aligned);

simd_t v(&ps.vel_x[i], stdx::element_aligned);

simd_t a(&ps.force_x[i], stdx::element_aligned); // assume unit mass

x += v * dt_vec + a * dt2_half;

v += a * dt_vec;

x.copy_to(&ps.pos_x[i], stdx::element_aligned);

v.copy_to(&ps.vel_x[i], stdx::element_aligned);

}

// Similar for y, z...

}

Parallel broad-phase with spatial hashing:

void broad_phase(ParticleSystem& ps, PairList& potential_collisions) {

SpatialHash grid(cell_size);

// Insert particles in parallel (needs thread-safe grid or per-thread grids)

std::for_each(std::execution::par,

indices.begin(), indices.end(),

[&](size_t i) {

grid.insert(i, ps.pos_x[i], ps.pos_y[i], ps.pos_z[i]);

});

// Query neighbors in parallel

std::for_each(std::execution::par,

indices.begin(), indices.end(),

[&](size_t i) {

auto neighbors = grid.query(ps.pos_x[i], ps.pos_y[i], ps.pos_z[i]);

for (size_t j : neighbors) {

if (i < j) { // Avoid duplicate pairs

potential_collisions.add(i, j); // Thread-safe append

}

}

});

}

Partitioning work to avoid races:

- Divide space into regions

- Each thread owns a region

- Particles near boundaries require synchronization

Learning milestones:

- Particles fall with gravity → You understand basic physics

- Collisions detected → You understand broad-phase

- SIMD integration speeds up → You understand vectorization

- Parallel broad-phase scales → You understand work distribution

- 60fps with 100K particles → You’ve built an efficient system

Project 15: Actor Model Framework

- File: LEARN_CPP_CONCURRENCY_AND_PARALLELISM.md

- Main Programming Language: C++

- Alternative Programming Languages: Erlang (for comparison), Rust, Scala

- Coolness Level: Level 5: Pure Magic (Super Cool)

- Business Potential: 4. The “Open Core” Infrastructure

- Difficulty: Level 5: Master

- Knowledge Area: Concurrency Patterns / Message Passing

- Software or Tool: Actor Framework

- Main Book: “C++ Concurrency in Action, Second Edition” by Anthony Williams

What you’ll build: An actor framework where isolated actors communicate only through message passing, with supervision hierarchies, location transparency, and no shared mutable state—similar to Akka or Erlang’s OTP.

Why it teaches advanced concurrency: Actors flip the paradigm: instead of threads accessing shared data, actors own data and exchange messages. This eliminates data races by design and teaches you about isolation, messaging patterns, and fault tolerance.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Actor isolation and mailboxes → maps to encapsulation and message queues

- Message dispatch → maps to pattern matching and type erasure

- Scheduler integration → maps to running actors on thread pool

- Supervision trees → maps to fault tolerance and recovery

- Location transparency → maps to abstracting local/remote

Key Concepts:

- Actor Model: “Reactive Design Patterns” by Roland Kuhn

- Message Passing: “C++ Concurrency in Action” Chapter 4 - Anthony Williams

- Lock-Free Queues: Project 6

Difficulty: Master Time estimate: 4-6 weeks Prerequisites: Projects 3 and 6 completed. Familiarity with variant/any for type erasure. Understanding of OOP design patterns.

Real world outcome:

// User code