Project 5: Clone of the xxd Hexdump Utility

Build a functional clone of the UNIX xxd/hexdump tool that transforms raw binary data into a human-readable three-column format: offset, hexadecimal values, and ASCII representation.

Project Overview

| Attribute | Value |

|---|---|

| Difficulty | Advanced |

| Time Estimate | 1-2 weeks |

| Languages | C (primary), Python, Rust, Go |

| Prerequisites | Projects 1-4, Strong programming skills, Manual string/byte manipulation |

| Key Topics | Binary file I/O, Byte representation, ASCII encoding, Printf formatting |

| Primary References | K&R Ch 7, Petzold Ch 20, CSAPP Ch 1-2 |

Table of Contents

- Learning Objectives

- Deep Theoretical Foundation

- Project Specification

- Real World Outcome

- The Core Question You’re Answering

- Concepts You Must Understand First

- Questions to Guide Your Design

- Thinking Exercise (Mandatory Pre-Coding)

- The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- Hints in Layers

- Complete C Implementation Template

- Common Pitfalls & Debugging

- Testing Strategy

- Definition of Done

- Books That Will Help

- Extension Ideas

- Self-Assessment Checklist

1. Learning Objectives

By completing this project, you will:

- Master binary file I/O: Understand the difference between text mode and binary mode file handling

- Decompose bytes into hex representation: Convert any byte value (0-255) into its two-character hexadecimal form

- Implement ASCII character classification: Distinguish printable from non-printable characters

- Handle buffer boundaries: Process files of arbitrary length with proper handling of partial final lines

- Format complex output: Align columns precisely using printf format specifiers

- Parse command-line arguments: Implement flags like

-s(skip),-l(limit), and-g(grouping) - Debug at the byte level: Use your own tool to inspect files and understand binary data

- Think like a reverse engineer: See files as bytes, not just content

2. Deep Theoretical Foundation

2.1 The Invisible Made Visible

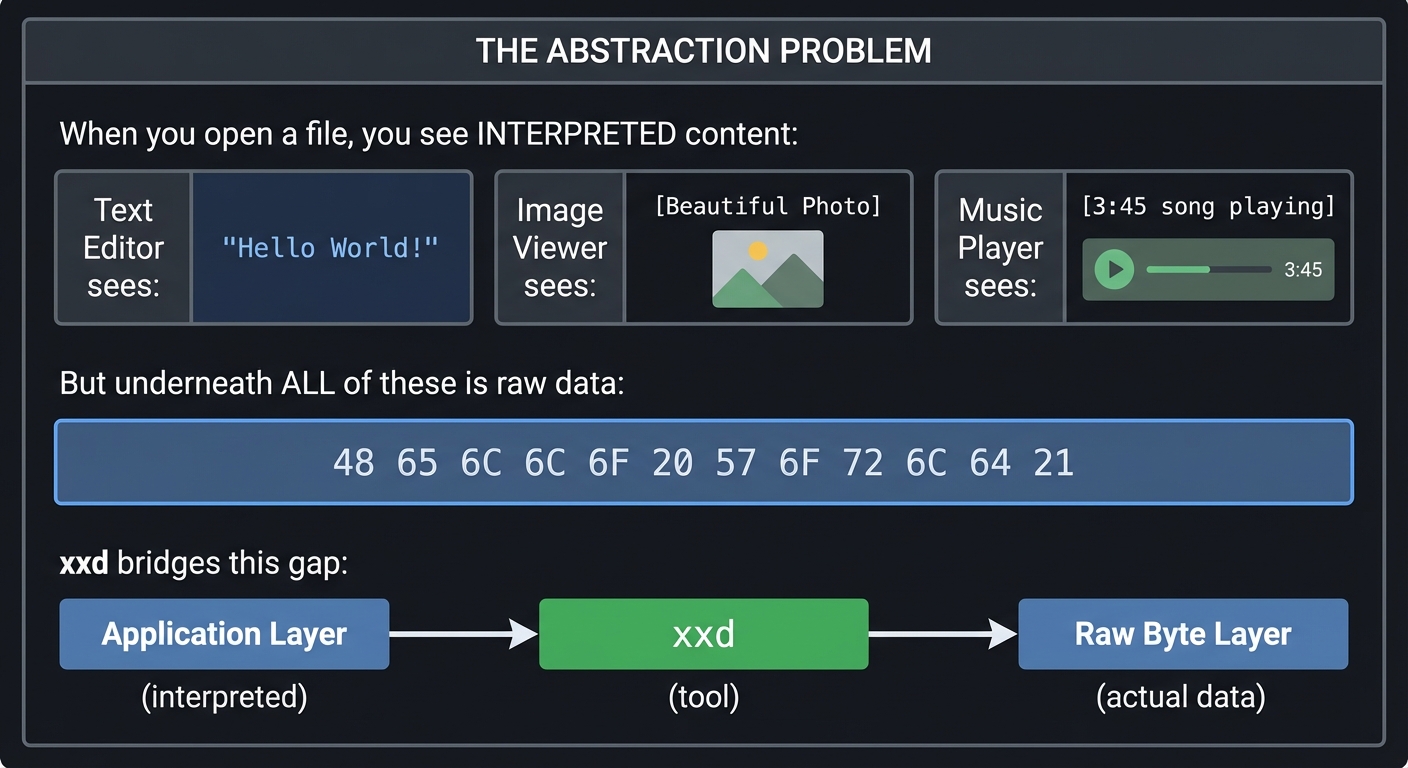

Every file on your computer—whether a photo, a program, or a document—is ultimately a sequence of bytes. Each byte is 8 bits, capable of representing 256 different values (0-255). But how do we examine these bytes directly?

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

| THE ABSTRACTION PROBLEM |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

| |

| When you open a file, you see INTERPRETED content: |

| |

| Text Editor sees: "Hello World!" |

| Image Viewer sees: [Beautiful Photo] |

| Music Player sees: [3:45 song playing] |

| |

| But underneath ALL of these is raw data: |

| |

| 48 65 6C 6C 6F 20 57 6F 72 6C 64 21 |

| |

| xxd bridges this gap: |

| Application Layer ---> xxd ---> Raw Byte Layer |

| (interpreted) (tool) (actual data) |

| |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

The xxd utility acts as a “microscope” for files, showing you what’s really stored on disk.

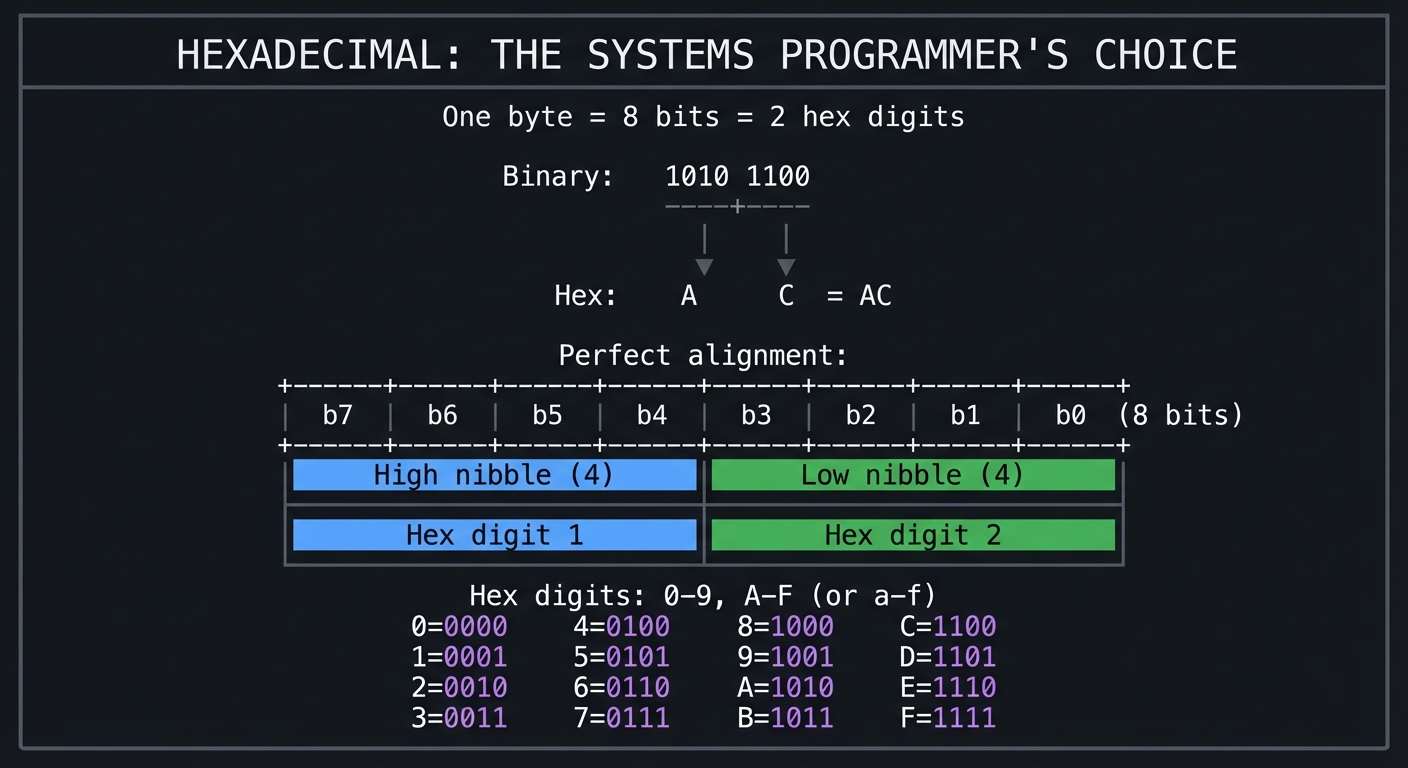

2.2 Why Hexadecimal? The Perfect Middle Ground

Binary is too verbose (8 digits per byte), and decimal is awkward for byte manipulation. Hexadecimal provides the perfect balance:

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

| HEXADECIMAL: THE SYSTEMS PROGRAMMER'S CHOICE |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

| |

| One byte = 8 bits = 2 hex digits |

| |

| Binary: 1010 1100 |

| ----+---- |

| | |

| v |

| Hex: A C = AC |

| |

| Perfect alignment: |

| +----+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+ |

| | b7 | b6 | b5 | b4 | b3 | b2 | b1 | b0 | (8 bits) |

| +----+----+---------+----+----+---------+ |

| | High nibble (4) | Low nibble (4) | |

| +-------------------+-------------------+ |

| | Hex digit 1 | Hex digit 2 | |

| +-------------------+-------------------+ |

| |

| Hex digits: 0-9, A-F (or a-f) |

| 0=0000 4=0100 8=1000 C=1100 |

| 1=0001 5=0101 9=1001 D=1101 |

| 2=0010 6=0110 A=1010 E=1110 |

| 3=0011 7=0111 B=1011 F=1111 |

| |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

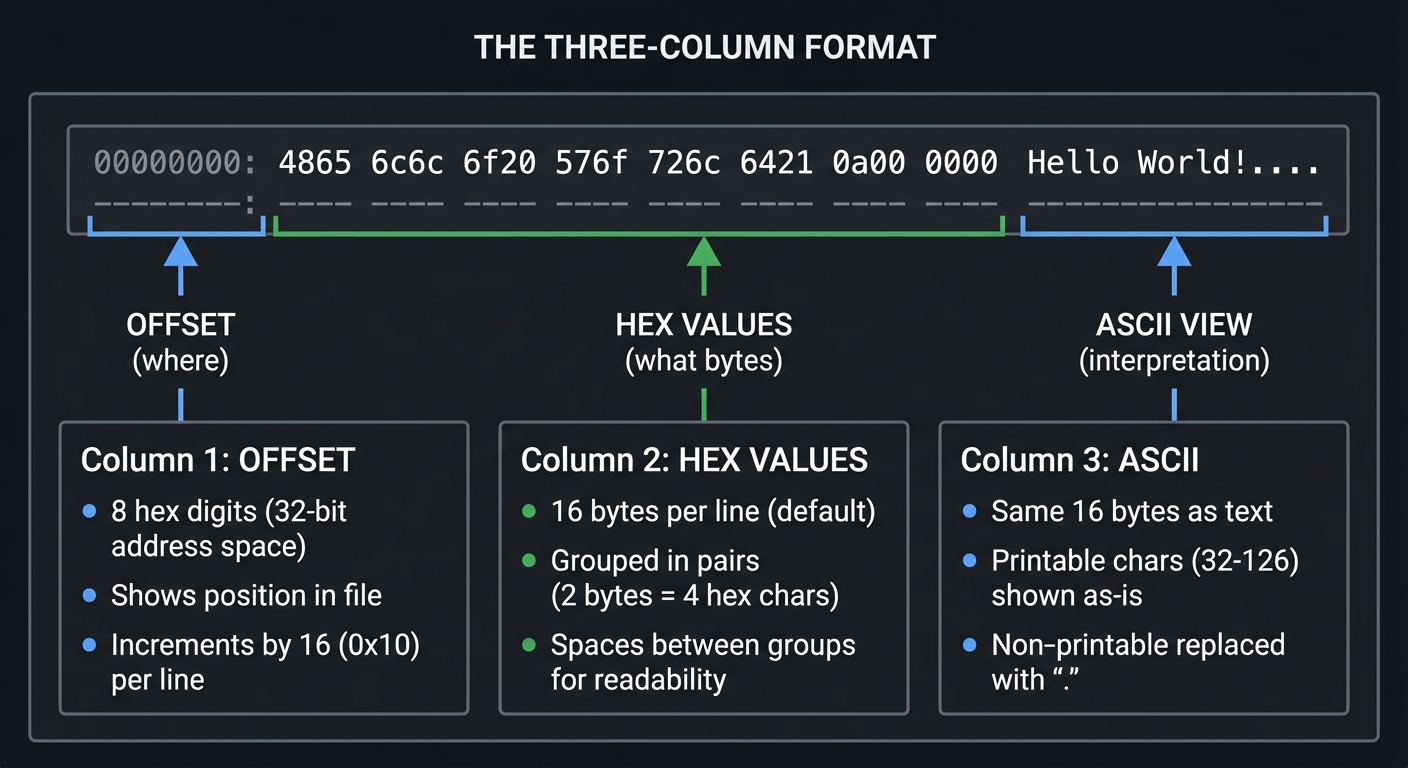

2.3 The xxd Output Format: A Three-Column Rosetta Stone

The xxd output format is brilliantly designed to show three views of the same data simultaneously:

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

| THE THREE-COLUMN FORMAT |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

| |

| 00000000: 4865 6c6c 6f20 576f 726c 6421 0a00 0000 Hello World!.... |

| -------- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ---------------- |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| v v v |

| OFFSET HEX VALUES ASCII VIEW |

| (where) (what bytes) (interpretation) |

| |

| Column 1: OFFSET |

| - 8 hex digits (32-bit address space) |

| - Shows position in file |

| - Increments by 16 (0x10) per line |

| |

| Column 2: HEX VALUES |

| - 16 bytes per line (default) |

| - Grouped in pairs (2 bytes = 4 hex chars) |

| - Spaces between groups for readability |

| |

| Column 3: ASCII |

| - Same 16 bytes as text |

| - Printable chars (32-126) shown as-is |

| - Non-printable replaced with '.' |

| |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

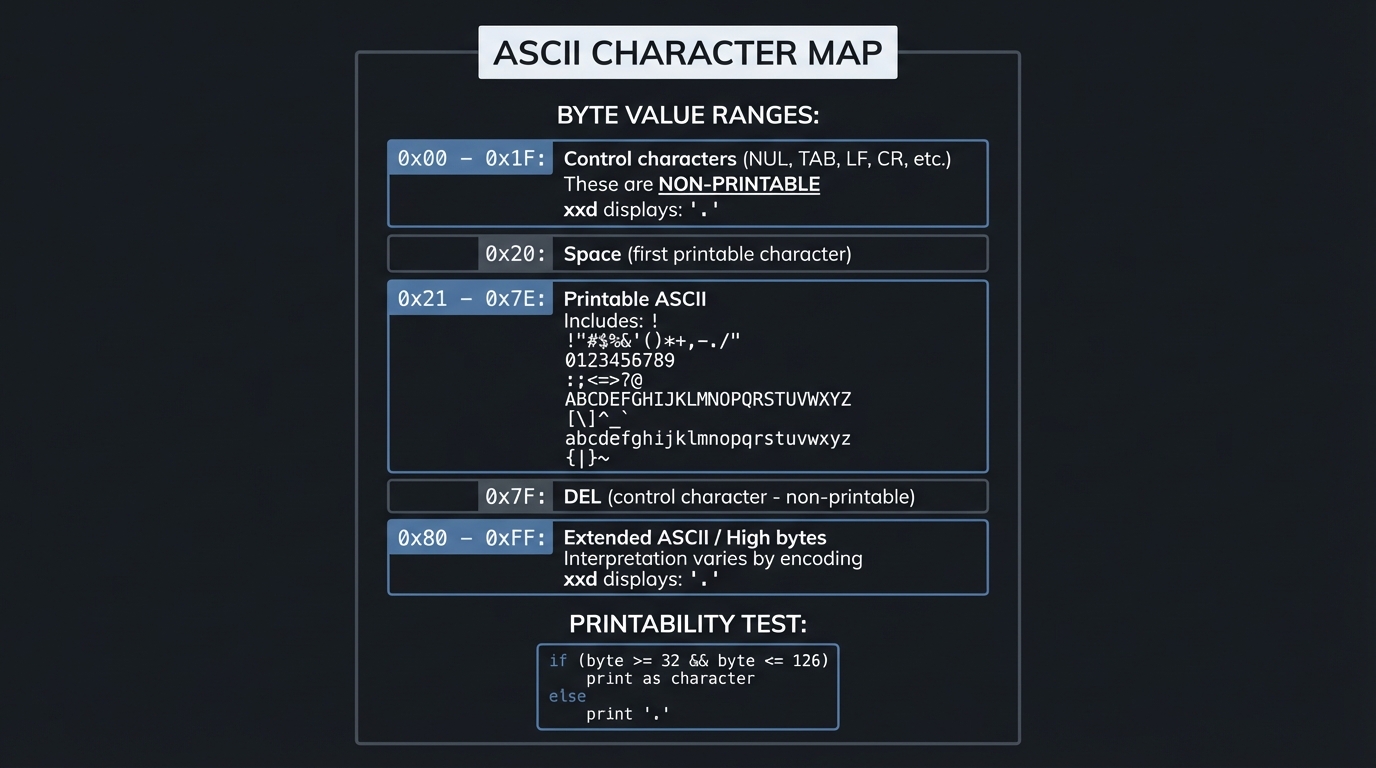

2.4 ASCII: The Bridge Between Bytes and Characters

The ASCII encoding maps byte values to human-readable characters:

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

| ASCII CHARACTER MAP |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

| |

| BYTE VALUE RANGES: |

| |

| 0x00 - 0x1F: Control characters (NUL, TAB, LF, CR, etc.) |

| These are NON-PRINTABLE |

| xxd displays: '.' |

| |

| 0x20 : Space (first printable character) |

| |

| 0x21 - 0x7E: Printable ASCII |

| Includes: !"#$%&'()*+,-./ |

| 0123456789 |

| :;<=>?@ |

| ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ |

| [\]^_` |

| abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz |

| {|}~ |

| |

| 0x7F : DEL (control character - non-printable) |

| |

| 0x80 - 0xFF: Extended ASCII / High bytes |

| Interpretation varies by encoding |

| xxd displays: '.' |

| |

| PRINTABILITY TEST: |

| +------------------------------------------------+ |

| | if (byte >= 32 && byte <= 126) | |

| | print as character | |

| | else | |

| | print '.' | |

| +------------------------------------------------+ |

| |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

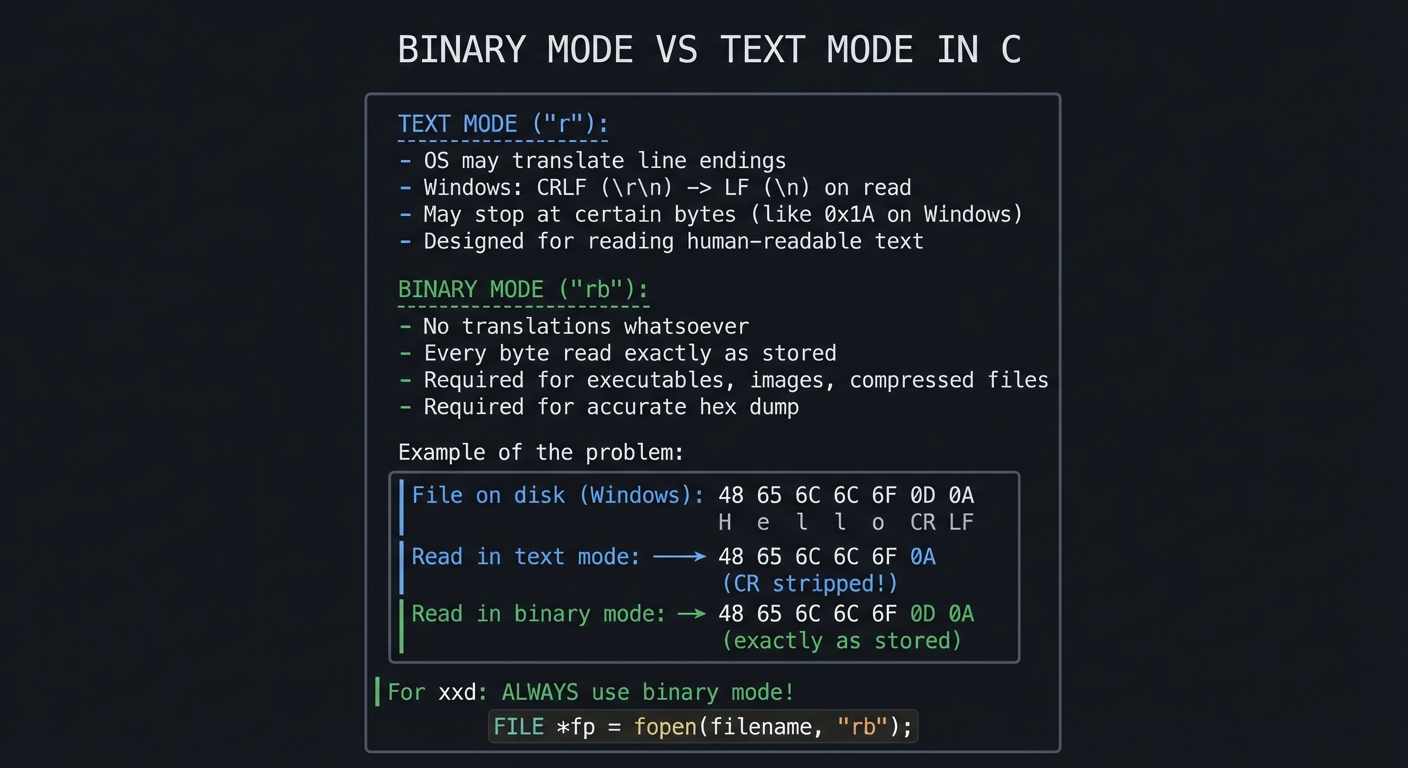

2.5 Binary Mode vs Text Mode: A Critical Distinction

When reading files for hex dump, you MUST use binary mode:

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

| BINARY MODE VS TEXT MODE IN C |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

| |

| TEXT MODE ("r"): |

| ---------------- |

| - OS may translate line endings |

| - Windows: CRLF (\r\n) -> LF (\n) on read |

| - May stop at certain bytes (like 0x1A on Windows) |

| - Designed for reading human-readable text |

| |

| BINARY MODE ("rb"): |

| ------------------- |

| - No translations whatsoever |

| - Every byte read exactly as stored |

| - Required for executables, images, compressed files |

| - Required for accurate hex dump |

| |

| Example of the problem: |

| +---------------------------------------------------+ |

| | File on disk (Windows): 48 65 6C 6C 6F 0D 0A | |

| | H e l l o CR LF | |

| | | |

| | Read in text mode: 48 65 6C 6C 6F 0A | |

| | (CR stripped!) | |

| | | |

| | Read in binary mode: 48 65 6C 6C 6F 0D 0A | |

| | (exactly as stored) | |

| +---------------------------------------------------+ |

| |

| For xxd: ALWAYS use binary mode! |

| FILE *fp = fopen(filename, "rb"); |

| |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

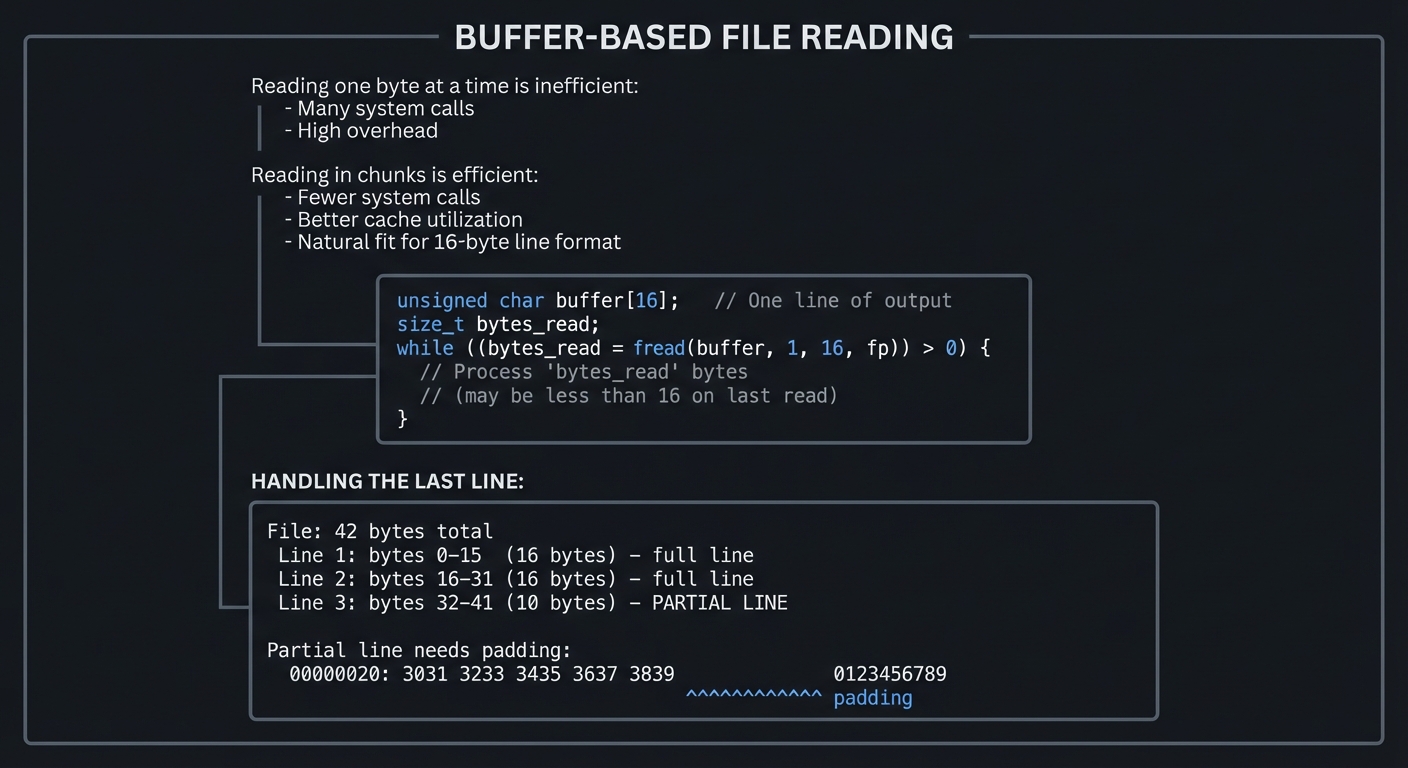

2.6 File I/O: Reading in Chunks

Efficient hex dump requires reading files in fixed-size chunks:

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

| BUFFER-BASED FILE READING |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

| |

| Reading one byte at a time is inefficient: |

| - Many system calls |

| - High overhead |

| |

| Reading in chunks is efficient: |

| - Fewer system calls |

| - Better cache utilization |

| - Natural fit for 16-byte line format |

| |

| +-----------------------------------------------------------+ |

| | | |

| | unsigned char buffer[16]; // One line of output | |

| | size_t bytes_read; | |

| | | |

| | while ((bytes_read = fread(buffer, 1, 16, fp)) > 0) { | |

| | // Process 'bytes_read' bytes | |

| | // (may be less than 16 on last read) | |

| | } | |

| | | |

| +-----------------------------------------------------------+ |

| |

| HANDLING THE LAST LINE: |

| +---------------------------------------------------+ |

| | File: 42 bytes total | |

| | | |

| | Line 1: bytes 0-15 (16 bytes) - full line | |

| | Line 2: bytes 16-31 (16 bytes) - full line | |

| | Line 3: bytes 32-41 (10 bytes) - PARTIAL LINE | |

| | | |

| | Partial line needs padding: | |

| | 00000020: 3031 3233 3435 3637 3839 0123456789 | |

| | ^^^^^^^^^^^ padding | |

| +---------------------------------------------------+ |

| |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

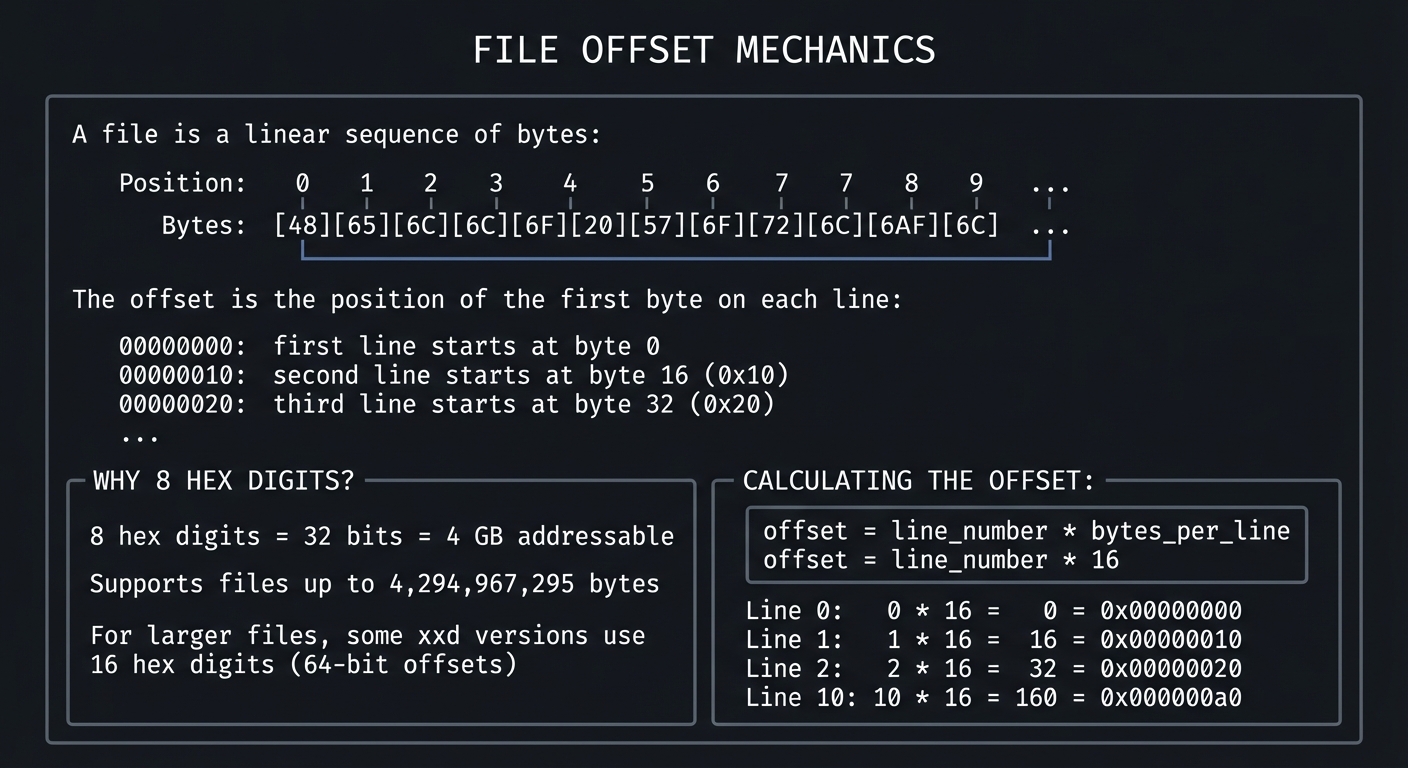

2.7 Understanding File Offsets

The offset tells you exactly where each byte is located in the file:

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

| FILE OFFSET MECHANICS |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

| |

| A file is a linear sequence of bytes: |

| |

| Position: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 ... |

| Bytes: [48][65][6C][6C][6F][20][57][6F][72][6C] ... |

| |

| The offset is the position of the first byte on each line: |

| |

| 00000000: first line starts at byte 0 |

| 00000010: second line starts at byte 16 (0x10) |

| 00000020: third line starts at byte 32 (0x20) |

| ... |

| |

| WHY 8 HEX DIGITS? |

| +---------------------------------------------------+ |

| | 8 hex digits = 32 bits = 4 GB addressable | |

| | Supports files up to 4,294,967,295 bytes | |

| | | |

| | For larger files, some xxd versions use | |

| | 16 hex digits (64-bit offsets) | |

| +---------------------------------------------------+ |

| |

| CALCULATING THE OFFSET: |

| +---------------------------------------------------+ |

| | offset = line_number * bytes_per_line | |

| | offset = line_number * 16 | |

| | | |

| | Line 0: 0 * 16 = 0 = 0x00000000 | |

| | Line 1: 1 * 16 = 16 = 0x00000010 | |

| | Line 2: 2 * 16 = 32 = 0x00000020 | |

| | Line 10: 10 * 16 = 160 = 0x000000a0 | |

| +---------------------------------------------------+ |

| |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

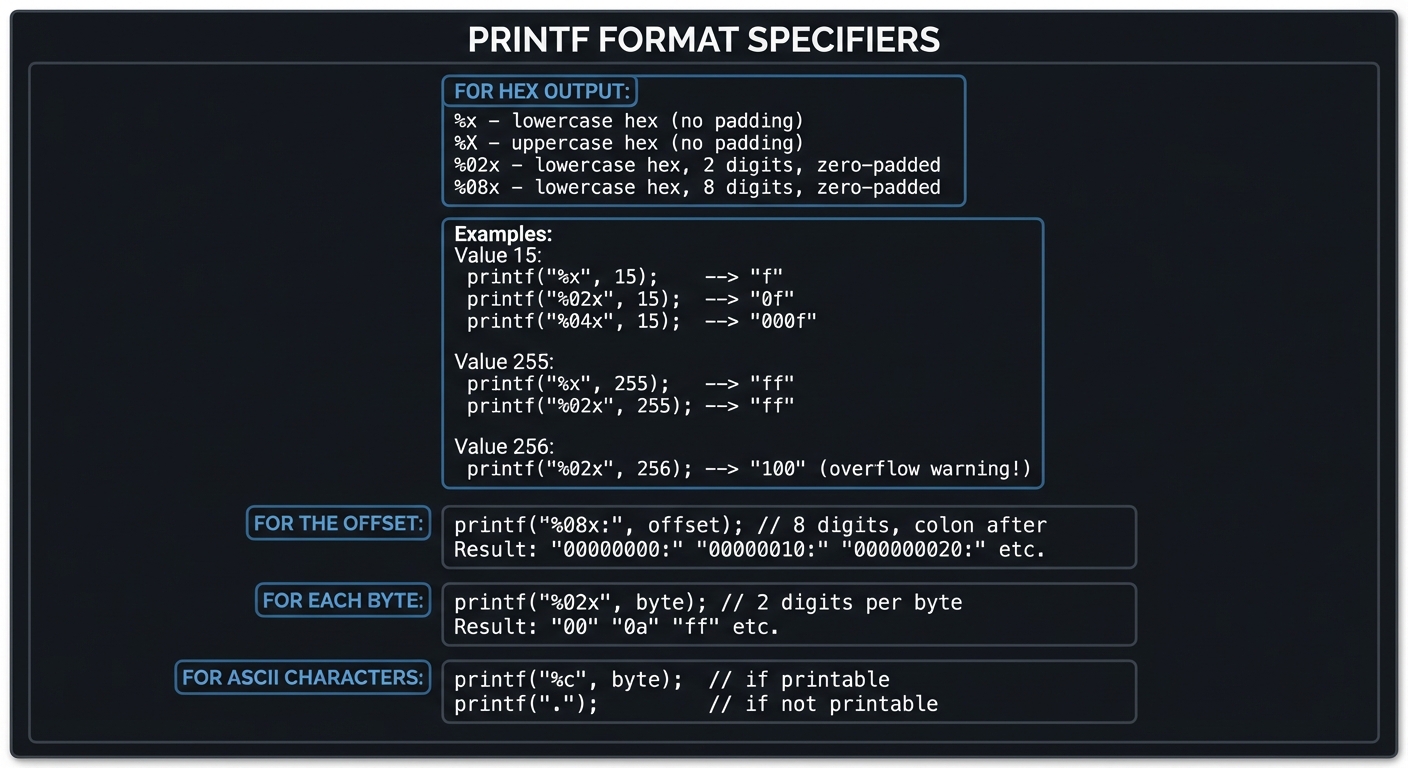

2.8 Printf Format Specifiers for Hex Output

Mastering printf is essential for proper formatting:

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

| PRINTF FORMAT SPECIFIERS |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

| |

| FOR HEX OUTPUT: |

| +-----------------------------------------------------------+ |

| | %x - lowercase hex (no padding) | |

| | %X - uppercase hex (no padding) | |

| | %02x - lowercase hex, 2 digits, zero-padded | |

| | %08x - lowercase hex, 8 digits, zero-padded | |

| +-----------------------------------------------------------+ |

| |

| Examples: |

| +-----------------------------------------------------------+ |

| | Value 15: | |

| | printf("%x", 15); --> "f" | |

| | printf("%02x", 15); --> "0f" | |

| | printf("%04x", 15); --> "000f" | |

| | | |

| | Value 255: | |

| | printf("%x", 255); --> "ff" | |

| | printf("%02x", 255); --> "ff" | |

| | | |

| | Value 256: | |

| | printf("%02x", 256); --> "100" (overflow warning!) | |

| +-----------------------------------------------------------+ |

| |

| FOR THE OFFSET: |

| printf("%08x:", offset); // 8 digits, colon after |

| Result: "00000000:" "00000010:" "00000020:" etc. |

| |

| FOR EACH BYTE: |

| printf("%02x", byte); // 2 digits per byte |

| Result: "00" "0a" "ff" etc. |

| |

| FOR ASCII CHARACTERS: |

| printf("%c", byte); // if printable |

| printf("."); // if not printable |

| |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

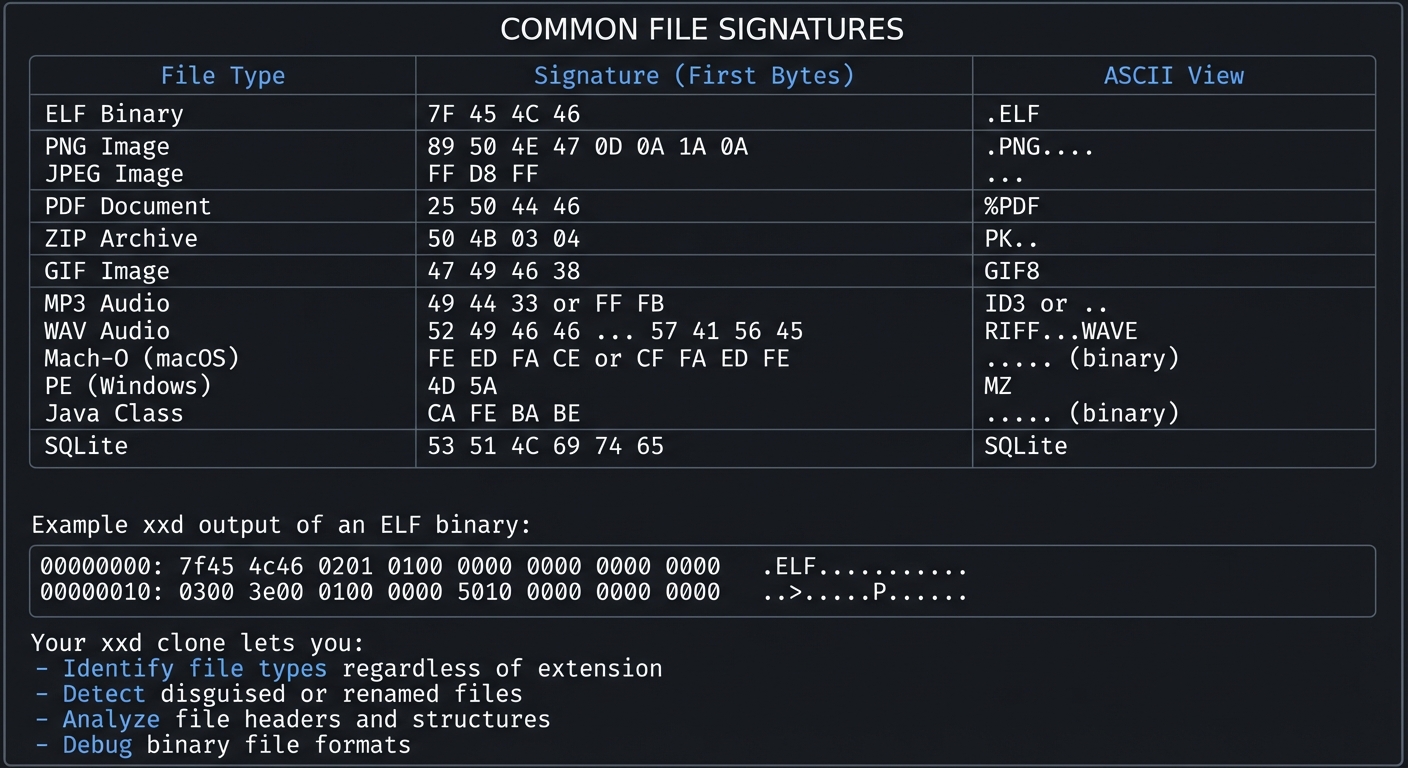

2.9 File Signatures: What Your Tool Will Reveal

One powerful use of hex dump is identifying file types by their signatures:

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

| COMMON FILE SIGNATURES |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

| |

| File Type Signature (First Bytes) ASCII View |

| ----------- ----------------------- ---------- |

| ELF Binary 7F 45 4C 46 .ELF |

| PNG Image 89 50 4E 47 0D 0A 1A 0A .PNG.... |

| JPEG Image FF D8 FF ... |

| PDF Document 25 50 44 46 %PDF |

| ZIP Archive 50 4B 03 04 PK.. |

| GIF Image 47 49 46 38 GIF8 |

| MP3 Audio 49 44 33 or FF FB ID3 or .. |

| WAV Audio 52 49 46 46 ... 57 41 56 45 RIFF...WAVE |

| Mach-O (macOS) FE ED FA CE or CF FA ED FE .... (binary) |

| PE (Windows) 4D 5A MZ |

| Java Class CA FE BA BE .... (binary) |

| SQLite 53 51 4C 69 74 65 SQLite |

| |

| Example xxd output of an ELF binary: |

| +-----------------------------------------------------------+ |

| | 00000000: 7f45 4c46 0201 0100 0000 0000 0000 0000 .ELF.......... |

| | 00000010: 0300 3e00 0100 0000 5010 0000 0000 0000 ..>.....P...... |

| +-----------------------------------------------------------+ |

| |

| Your xxd clone lets you: |

| - Identify file types regardless of extension |

| - Detect disguised or renamed files |

| - Analyze file headers and structures |

| - Debug binary file formats |

| |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

3. Project Specification

3.1 What You Will Build

A command-line utility that reads any file and produces a three-column hex dump:

- Byte offset (8 hex digits)

- Hex values (grouped in pairs by default)

- ASCII representation (dots for non-printable characters)

3.2 Required Features

Core Functionality:

- Read any file (binary or text)

- Output 16 bytes per line

- Format offset as 8 lowercase hex digits

- Group hex bytes in pairs (4 hex chars per group)

- Show ASCII representation with dots for non-printable

- Handle files of any size

- Handle files with sizes not divisible by 16

Command-Line Flags (implement progressively):

| Flag | Description | Example |

|——|————-|———|

| -l <len> | Limit to len bytes of output | xxd -l 64 file.bin |

| -s <offset> | Skip to offset before dumping | xxd -s 100 file.bin |

| -g <bytes> | Group bytes (default 2) | xxd -g 1 file.bin |

| -c <cols> | Bytes per line (default 16) | xxd -c 8 file.bin |

| -u | Use uppercase hex | xxd -u file.bin |

3.3 Input/Output Specification

Input:

- File path as command-line argument

- Or read from stdin if no file specified

Output:

00000000: 4865 6c6c 6f20 576f 726c 6421 0a00 0000 Hello World!....

00000010: 5468 6973 2069 7320 6120 7465 7374 2e0a This is a test..

3.4 Edge Cases to Handle

- Empty files (no output)

- Files smaller than 16 bytes (single partial line)

- Binary files with embedded nulls

- Very large files (streaming, not loading entire file)

- Files with no read permission (error message)

- Non-existent files (error message)

4. Real World Outcome

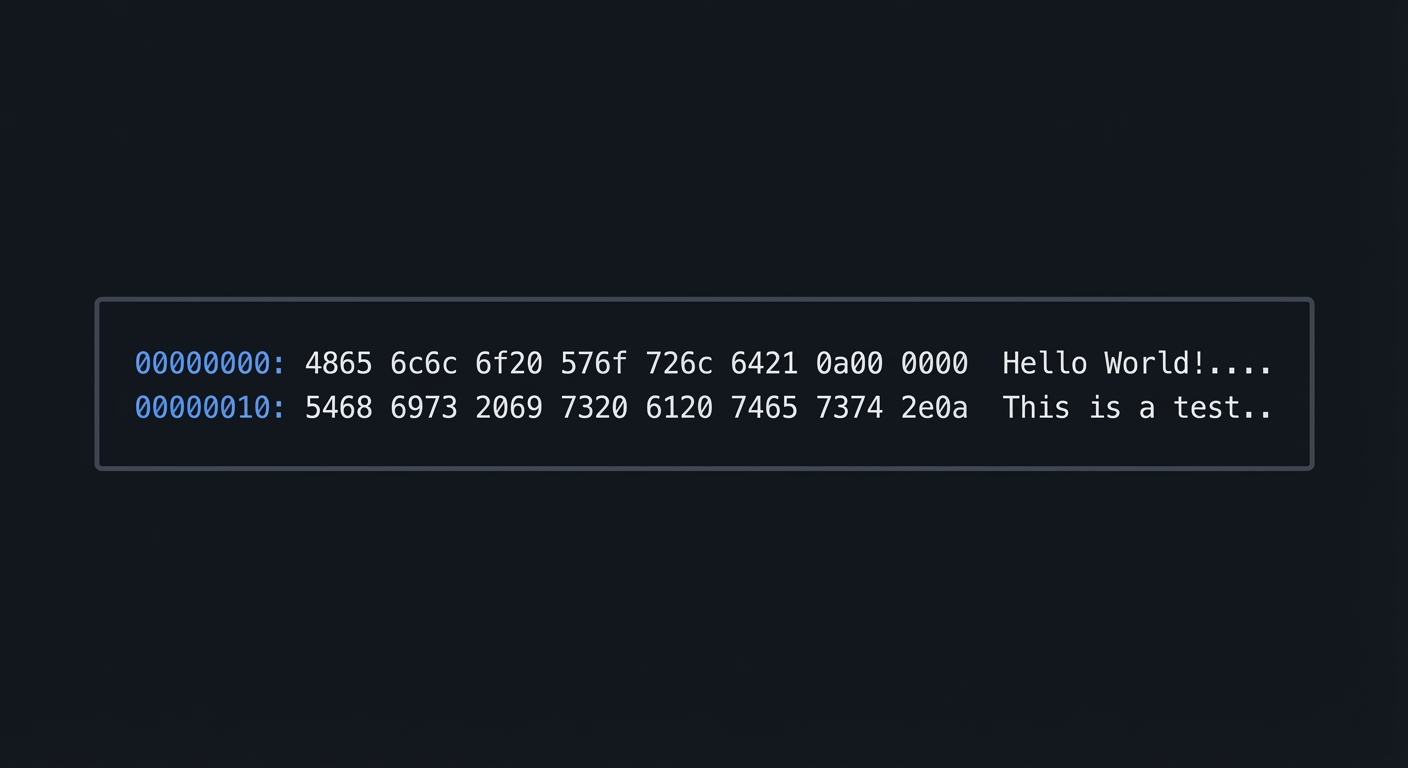

4.1 Example: Regular Text File

$ echo "Hello World!" > test.txt

$ ./myxxd test.txt

00000000: 4865 6c6c 6f20 576f 726c 6421 0a Hello World!.

Notice:

0ais the newline character- Only 13 bytes, so line is shorter than usual

- ASCII column shows the readable text

4.2 Example: Binary Executable (ELF Header)

$ ./myxxd -l 48 /bin/ls

00000000: 7f45 4c46 0201 0100 0000 0000 0000 0000 .ELF............

00000010: 0300 3e00 0100 0000 5010 0000 0000 0000 ..>.....P.......

00000020: 4000 0000 0000 0000 e8b1 0100 0000 0000 @...............

Notice:

7f 45 4c 46= ELF magic number (.ELFin ASCII)- Most bytes are non-printable (shown as dots)

- Header structure visible in hex

4.3 Example: Using Skip and Limit Flags

$ ./myxxd -s 100 -l 32 large_file.bin

00000064: 0102 0304 0506 0708 090a 0b0c 0d0e 0f10 ................

00000074: 1112 1314 1516 1718 191a 1b1c 1d1e 1f20 ...............

Notice:

- Offset starts at 100 (0x64), not 0

- Only 32 bytes shown (limit)

4.4 Example: Group by 1 Byte

$ ./myxxd -g 1 -l 16 test.txt

00000000: 48 65 6c 6c 6f 20 57 6f 72 6c 64 21 0a Hello World!.

Notice:

- Each byte separated by space

- Easier to read individual bytes

4.5 Practical Applications

Inspecting Executables:

$ ./myxxd -l 64 suspicious_program

# Check for ELF/PE headers, detect packing, find strings

Debugging Network Protocols:

$ tcpdump -X | ./myxxd

# Analyze packet contents, find protocol headers

Reverse Engineering File Formats:

$ ./myxxd -s 0 -l 512 unknown_format.dat

# Identify magic numbers, understand header structure

Malware Analysis:

$ ./myxxd malware_sample > analysis.txt

# Safe inspection without execution

Analyzing Corrupted Files:

$ ./myxxd corrupted.jpg | head -20

# Find where corruption starts

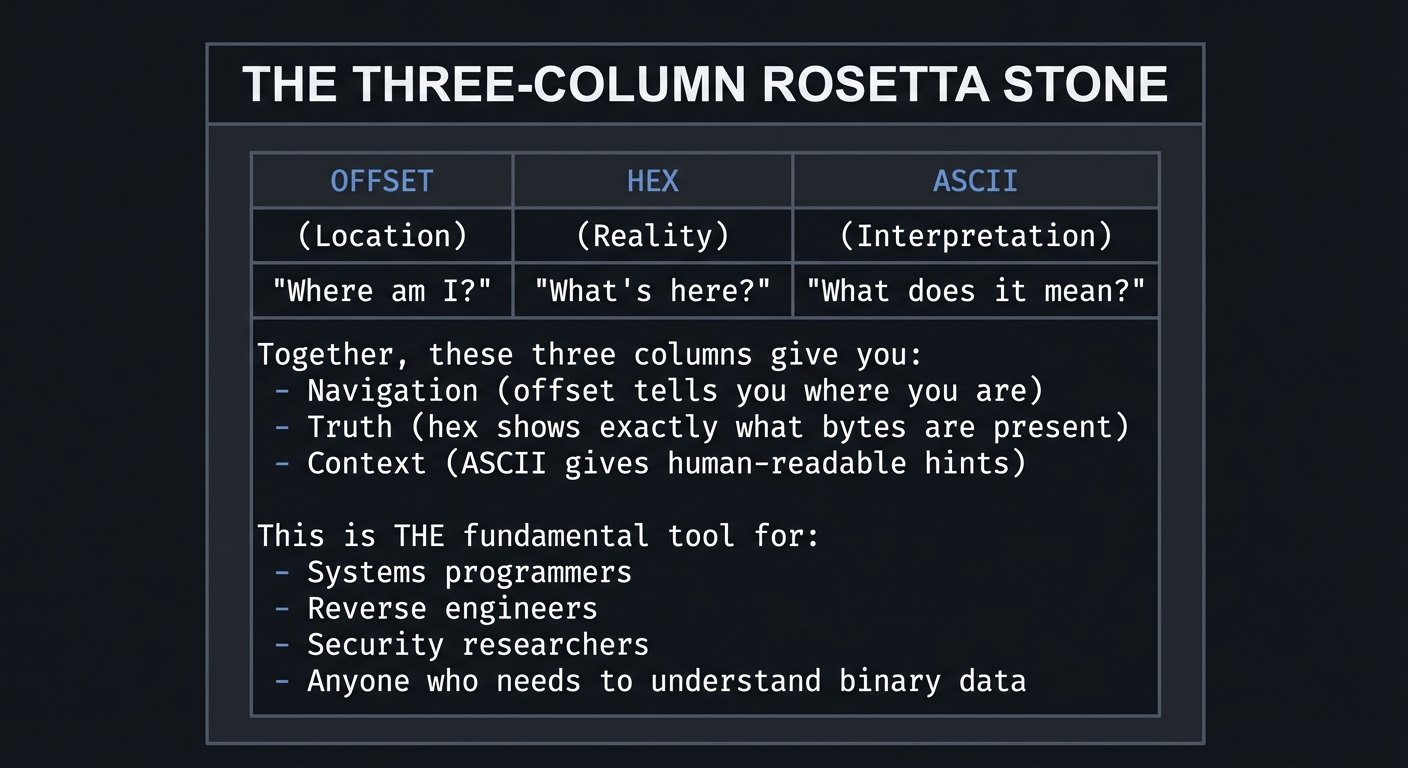

5. The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do I make the invisible visible—transforming raw binary data into a human-readable format that reveals the true structure of any file?”

The hex dump is your Rosetta Stone for digital data:

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

| THE THREE-COLUMN ROSETTA STONE |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

| |

| OFFSET HEX ASCII |

| (Location) (Reality) (Interpretation) |

| |

| "Where am I?" "What's here?" "What does it mean?" |

| |

| Together, these three columns give you: |

| - Navigation (offset tells you where you are) |

| - Truth (hex shows exactly what bytes are present) |

| - Context (ASCII gives human-readable hints) |

| |

| This is THE fundamental tool for: |

| - Systems programmers |

| - Reverse engineers |

| - Security researchers |

| - Anyone who needs to understand binary data |

| |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------+

6. Concepts You Must Understand First

| Concept | What You Must Know | Book Reference | Chapter |

|---|---|---|---|

| File I/O in C | fopen, fread, fclose, fseek |

K&R | Ch 7 |

| Binary vs Text Mode | "r" vs "rb", line ending translation |

K&R | 7.5 |

| Buffer Management | Fixed-size arrays, avoiding overflow | K&R | Ch 5 |

| ASCII Character Set | Printable range 32-126, control chars | Petzold | Ch 20 |

| Hexadecimal Formatting | %02x, %08x format specifiers |

K&R | 7.2 |

| Printf Format Specifiers | Field width, padding, alignment | K&R | 7.2 |

| Loop Constructs | while, for, processing until EOF |

K&R | Ch 3 |

| Command-line Arguments | argc, argv, parsing options |

K&R | 5.10 |

| Pointer Arithmetic | Array indexing, buffer traversal | K&R | Ch 5 |

| Error Handling | errno, perror, return codes |

K&R | App B |

| Bitwise Operations | &, |, bit masking |

K&R | 2.9 |

| Unsigned Types | unsigned char for byte data |

K&R | 2.2 |

7. Questions to Guide Your Design

Architecture & Flow

-

How will you structure the main loop? Will you read one byte at a time, 16 bytes at a time, or use a larger buffer?

-

How will you track the current offset? Will you maintain a counter, or compute it from the line number?

-

How will you handle EOF? What if fread returns fewer bytes than requested?

Data Representation

-

Why must you use

unsigned charinstead ofchar? What happens if a byte value is greater than 127? -

How will you convert a byte to two hex characters? Will you use printf, a lookup table, or manual calculation?

-

How will you determine if a character is printable? What are the exact boundary values?

Output Formatting

-

How will you handle the grouping of hex digits? When do you print spaces between groups?

-

How will you align the ASCII column when the last line is partial? How much padding is needed?

-

What’s the exact spacing between the three columns? How will you match real xxd output?

Edge Cases

-

What happens with a zero-length file? Should you output anything?

-

What if the file contains only non-printable bytes? The ASCII column will be all dots.

-

How do you handle a file exactly 16 bytes long? One full line, no partial line issues.

Advanced Features

-

How will you implement the

-s(skip) flag? Will you usefseekor read and discard? -

How will you implement the

-l(limit) flag? When do you stop reading? -

Could you implement reverse operation (hex to binary)? What parsing challenges arise?

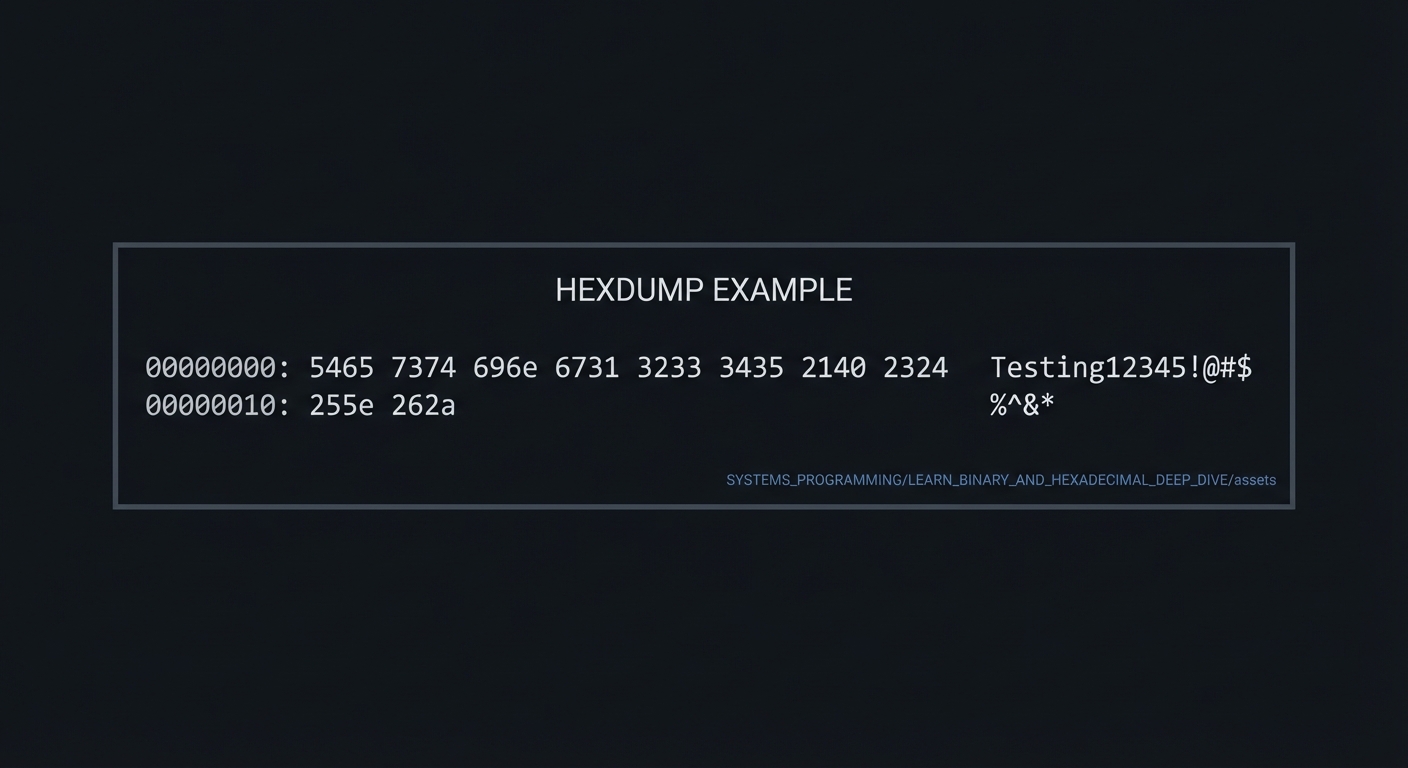

8. Thinking Exercise (Mandatory Pre-Coding)

Before writing any code, complete this exercise on paper:

Create a 20-byte mock file:

Let’s say the file contains: Testing12345!@#$%^&*

Step 1: Convert each character to ASCII decimal

| Char | T | e | s | t | i | n | g | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ! | @ | # | $ | % | ^ | & | * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dec | 84 | 101 | 115 | 116 | 105 | 110 | 103 | 49 | 50 | 51 | 52 | 53 | 33 | 64 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 94 | 38 | 42 |

Step 2: Convert each decimal to hex

| Dec | 84 | 101 | 115 | 116 | 105 | 110 | 103 | 49 | 50 | 51 | 52 | 53 | 33 | 64 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 94 | 38 | 42 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hex | 54 | 65 | 73 | 74 | 69 | 6e | 67 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 21 | 40 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 5e | 26 | 2a |

Step 3: Group into 16-byte lines with expected output

00000000: 5465 7374 696e 6731 3233 3435 2140 2324 Testing12345!@#$

00000010: 255e 262a %^&*

Step 4: Verify with real xxd

$ echo -n "Testing12345!\@#\$%^&*" > test.bin

$ xxd test.bin

Questions to answer:

- Did your manual calculation match?

- How did you handle the second line with only 4 bytes?

- What padding was needed in the hex column?

9. The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Conceptual Questions

Q1: Why use hexadecimal instead of binary or decimal for byte display?

Strong Answer:

Hexadecimal provides the perfect balance between compactness and alignment with binary. Each hex digit represents exactly 4 bits (one nibble), so one byte always equals exactly two hex digits. This makes mental conversion to binary trivial—you just expand each hex digit to 4 bits. Decimal doesn’t have this property; byte value 255 is “FF” in hex (2 chars) but “255” in decimal (3 chars), breaking alignment. Binary would be accurate but too verbose—8 characters per byte makes output unreadable.

Q2: What’s the difference between opening a file in text mode vs binary mode?

Strong Answer:

Text mode allows the operating system to perform translations on the file content. On Windows, this means converting CRLF line endings (\r\n) to just LF (\n) on read, and vice versa on write. It may also stop reading at certain control characters like Ctrl-Z. Binary mode reads bytes exactly as stored—no translation whatsoever. For a hex dump tool, binary mode is mandatory because we need to see every byte exactly as it exists on disk, including any \r\n sequences or embedded nulls.

Q3: What makes a character “printable” in ASCII?

Strong Answer:

Printable ASCII characters have byte values from 32 (space) through 126 (tilde ~). Values 0-31 are control characters (null, tab, newline, etc.) that don’t have visual representations. Value 127 is DEL, also a control character. Values 128-255 are not part of standard ASCII at all—they’re extended characters whose interpretation depends on the encoding. In a hex dump, we display printable characters as themselves and replace everything else with a dot or similar placeholder. The test is simply:

if (byte >= 32 && byte <= 126).

Implementation Questions

Q4: Your hex dump is slow on a 1GB file. What’s wrong?

Strong Answer:

The most likely issue is reading one byte at a time with fgetc() or similar, which creates massive system call overhead. The solution is to read in larger chunks—at minimum 16 bytes at a time to match the output line format, but ideally using an even larger buffer (like 4KB or 64KB) and processing 16 bytes at a time from that buffer. This reduces system calls from 1 billion to about 65 thousand for a 64KB buffer. Also ensure you’re not calling printf for every single byte; build up a line in memory and output it once.

Q5: How do you handle the last line if it’s not 16 bytes?

Strong Answer:

The last line needs special formatting. First, I only print the hex values for the bytes that actually exist—no padding with zeros. Second, I need to add spaces to align the ASCII column. With default grouping of 2 bytes, each group takes 4 hex chars plus 1 space. If I have, say, 10 bytes instead of 16, I’m missing 6 bytes which is 3 groups worth of space (12 chars for hex digits + 3 separating spaces). I calculate the padding needed and insert it before the ASCII column. The ASCII column itself only shows the bytes that exist.

Q6: What printf format specifier do you use for the offset?

Strong Answer:

I use

%08xfor the offset. The0means pad with zeros, the8means exactly 8 characters wide, andxmeans lowercase hexadecimal. This ensures the offset is always exactly 8 hex digits, like “00000000” or “0000ff10”. The colon after is literal:printf("%08x: ", offset). For files larger than 4GB, the offset would overflow 32 bits, so some implementations use%016lxwith a 64-bit offset.

Debugging Questions

Q7: Your tool shows garbage for the offset on large files. What’s wrong?

Strong Answer:

The offset is probably overflowing. If I’m using a 32-bit signed int for the offset, it overflows at 2GB. A 32-bit unsigned int overflows at 4GB. For proper handling of large files, I should use

size_toruint64_tfor the offset counter and%zuor%lxin printf. Also, on some systems,fseekwith a 32-bit offset can’t seek beyond 2GB, so I might needfseekowithoff_ttype.

Q8: You need to add support for starting at a specific offset. How?

Strong Answer:

I’d implement a

-s <offset>flag. After opening the file, I’d callfseek(fp, offset, SEEK_SET)to jump to that position before starting the read loop. The offset counter for display would start at this value instead of zero. For seekable files, this is efficient. For non-seekable input like stdin, I’d have to read and discard bytes until reaching the offset. I’d also handle the case where the offset is beyond EOF—I’d detect this when fseek succeeds but the subsequent fread returns 0, and output nothing.

Real-World Questions

Q9: How would you use xxd to debug a network protocol issue?

Strong Answer:

I’d capture network traffic using tcpdump or similar, save it to a file, then use xxd to analyze the raw bytes. I’d look for protocol headers by their known byte signatures—like HTTP starting with “48 54 54 50” (HTTP), or TLS starting with specific handshake bytes. I can use

-sto skip to a specific packet offset and-lto limit output to just the header. Comparing the hex output against the protocol specification reveals issues like wrong byte order, missing fields, or incorrect length values. It’s especially useful when Wireshark’s interpretation seems wrong.

Q10: A colleague gives you a suspicious executable. How do you analyze it safely?

Strong Answer:

I’d use xxd (or my clone) to examine it without executing—hex dump doesn’t run code, it just reads bytes. First, I’d check the magic number: ELF files start with “7f 45 4c 46”, PE (Windows) with “4d 5a”. I’d look for embedded strings using xxd piped to strings, or just scan the hex dump for ASCII patterns. I’d check for known packer signatures, weird section names, or encrypted regions (high entropy random-looking bytes). I’d note the file’s sections and entry point from the headers. All this analysis happens with the file treated as pure data, making it safe even if the code is malicious.

10. Hints in Layers

Challenge 1: Reading the File in Chunks

Layer 1: Conceptual Hint

You need to read exactly 16 bytes at a time (one line of output). The fread function can do this. Think about what happens when there are fewer than 16 bytes left in the file.

Layer 2: More Detail

fread returns the number of items successfully read, not the number of bytes (unless item size is 1). Use it like this:

size_t bytes = fread(buffer, 1, 16, fp);

Here, item size is 1, and you request 16 items, so it returns the number of bytes read. This will be less than 16 on the last chunk if the file size isn’t a multiple of 16.

Layer 3: Code Example

unsigned char buffer[16];

size_t bytes_read;

unsigned long offset = 0;

while ((bytes_read = fread(buffer, 1, 16, fp)) > 0) {

// Print offset

printf("%08lx: ", offset);

// Print hex bytes (only 'bytes_read' of them)

for (size_t i = 0; i < bytes_read; i++) {

printf("%02x", buffer[i]);

// Add space between groups (implementation varies)

}

// Handle padding if bytes_read < 16

// ...

// Print ASCII

// ...

offset += bytes_read;

}

Challenge 2: Formatting the Offset

Layer 1: Conceptual Hint

The offset needs to be displayed as exactly 8 hexadecimal digits, padded with leading zeros. The printf function has a format specifier for this.

Layer 2: More Detail

The format specifier %08x means: lowercase hex, minimum 8 characters, pad with zeros on the left. After the offset, print a colon and a space before the hex values.

For large files, use %08lx with an unsigned long type to avoid overflow.

Layer 3: Code Example

unsigned long offset = 0;

// For each line:

printf("%08lx:", offset); // e.g., "00000000:" "00000010:"

// Update offset after processing each line

offset += bytes_read;

// For very large files (>4GB), use:

unsigned long long offset = 0;

printf("%016llx:", offset); // 16 digits for 64-bit offsets

Challenge 3: Converting Bytes to Hex

Layer 1: Conceptual Hint

Each byte (0-255) needs to become exactly two hex characters. You can use printf’s %02x specifier, or you can build the characters yourself using a lookup table or arithmetic.

Layer 2: More Detail

The %02x format means: lowercase hex, minimum 2 characters, pad with zeros. This handles bytes 0-15 correctly (turning 0x0F into “0f” not “f”).

Make sure to use unsigned char for your buffer—signed char can give negative values for bytes > 127, causing unexpected output.

Layer 3: Code Example

// Method 1: Using printf

unsigned char byte = 0x0A;

printf("%02x", byte); // prints "0a"

// Method 2: Using a lookup table (faster for intensive use)

const char hex_chars[] = "0123456789abcdef";

char high = hex_chars[(byte >> 4) & 0x0F]; // high nibble

char low = hex_chars[byte & 0x0F]; // low nibble

printf("%c%c", high, low); // prints "0a"

// Method 3: Building into a string buffer

char hex_output[50]; // enough for one line of hex

int pos = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < bytes_read; i++) {

pos += sprintf(hex_output + pos, "%02x", buffer[i]);

if (i % 2 == 1) hex_output[pos++] = ' '; // space between groups

}

Challenge 4: Printing the ASCII Column

Layer 1: Conceptual Hint

Only characters with byte values 32-126 are printable. Everything else should be displayed as a dot (.). This creates the familiar ASCII column at the right of the hex dump.

Layer 2: More Detail

Use a simple if statement or the ternary operator to decide whether to print the character itself or a dot:

char c = (byte >= 32 && byte <= 126) ? byte : '.';

You could also use isprint() from <ctype.h>, but be careful—it may give different results depending on locale settings.

Layer 3: Code Example

// Print ASCII column for 'bytes_read' bytes

printf(" "); // Separator between hex and ASCII

for (size_t i = 0; i < bytes_read; i++) {

unsigned char byte = buffer[i];

if (byte >= 32 && byte <= 126) {

putchar(byte);

} else {

putchar('.');

}

}

putchar('\n'); // End the line

// More compact version:

for (size_t i = 0; i < bytes_read; i++) {

putchar((buffer[i] >= 32 && buffer[i] <= 126) ? buffer[i] : '.');

}

Challenge 5: Handling the Last Line (Padding)

Layer 1: Conceptual Hint

When the last line has fewer than 16 bytes, the hex column is shorter. You need to add spaces so the ASCII column starts at the same position as on full lines.

Layer 2: More Detail

Calculate how much space the missing bytes would have taken:

- Each missing byte = 2 hex chars

- Each missing group separator (depends on grouping)

- With grouping of 2, every 2 bytes adds 1 space

Count the missing characters and print that many spaces before the ASCII column.

Layer 3: Code Example

#define BYTES_PER_LINE 16

#define GROUP_SIZE 2

// After printing the hex values we have:

size_t missing_bytes = BYTES_PER_LINE - bytes_read;

// Calculate padding needed:

// Each missing byte is 2 hex chars

// Each missing pair (GROUP_SIZE bytes) adds 1 space separator

size_t padding = missing_bytes * 2;

padding += (missing_bytes / GROUP_SIZE);

// If we're mid-group, we also need the space that would have followed

if (bytes_read % GROUP_SIZE != 0) {

// We printed a partial group, no trailing space

// Actually depends on your implementation...

}

// Print padding

for (size_t i = 0; i < padding; i++) {

putchar(' ');

}

// Alternative: use printf width specifier

// If hex portion should be exactly N chars, calculate remaining

printf("%*s", (int)padding, ""); // Print 'padding' spaces

Challenge 6: Complete Program Structure

Layer 1: Conceptual Hint

The main program should:

- Parse command-line arguments

- Open the file in binary mode

- Loop reading 16 bytes at a time

- Format and print each line

- Handle the last partial line

- Clean up and exit

Layer 2: More Detail

Structure your code into functions:

print_line(offset, buffer, count)- formats one line of outputprint_hex_bytes(buffer, count)- prints the hex columnprint_ascii(buffer, count)- prints the ASCII columnmain()- handles args, file I/O, main loop

Layer 3: Minimal Working Template

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#define BYTES_PER_LINE 16

void print_line(unsigned long offset, unsigned char *buffer, size_t count) {

// Print offset

printf("%08lx:", offset);

// Print hex bytes with grouping

for (size_t i = 0; i < count; i++) {

if (i % 2 == 0) printf(" "); // Space before each pair

printf("%02x", buffer[i]);

}

// Padding for short lines

for (size_t i = count; i < BYTES_PER_LINE; i++) {

if (i % 2 == 0) printf(" ");

printf(" ");

}

// ASCII column

printf(" ");

for (size_t i = 0; i < count; i++) {

unsigned char c = buffer[i];

putchar((c >= 32 && c <= 126) ? c : '.');

}

putchar('\n');

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

FILE *fp;

if (argc < 2) {

fp = stdin;

} else {

fp = fopen(argv[1], "rb");

if (!fp) {

perror(argv[1]);

return 1;

}

}

unsigned char buffer[BYTES_PER_LINE];

unsigned long offset = 0;

size_t bytes_read;

while ((bytes_read = fread(buffer, 1, BYTES_PER_LINE, fp)) > 0) {

print_line(offset, buffer, bytes_read);

offset += bytes_read;

}

if (fp != stdin) fclose(fp);

return 0;

}

11. Complete C Implementation Template

This template provides a skeleton that learners can fill in. Key sections are marked with TODO comments:

/*

* myxxd.c - A clone of the xxd hexdump utility

*

* Build: gcc -Wall -Wextra -o myxxd myxxd.c

* Usage: ./myxxd [-s offset] [-l length] [-g grouping] [file]

*/

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h> // for getopt

/* Configuration constants */

#define DEFAULT_BYTES_PER_LINE 16

#define DEFAULT_GROUP_SIZE 2

#define OFFSET_WIDTH 8

/* Global settings (modifiable by command-line options) */

typedef struct {

int bytes_per_line;

int group_size;

long skip_offset;

long limit_bytes;

int uppercase;

} Settings;

/* Initialize with defaults */

void init_settings(Settings *s) {

s->bytes_per_line = DEFAULT_BYTES_PER_LINE;

s->group_size = DEFAULT_GROUP_SIZE;

s->skip_offset = 0;

s->limit_bytes = -1; /* -1 means no limit */

s->uppercase = 0;

}

/*

* is_printable - Check if a byte is a printable ASCII character

*

* TODO: Implement this function

* Returns: 1 if printable, 0 if not

* Hint: Printable ASCII is 32-126 inclusive

*/

int is_printable(unsigned char byte) {

/* YOUR CODE HERE */

return 0; /* Replace with actual implementation */

}

/*

* print_hex_byte - Print a single byte as two hex characters

*

* TODO: Implement this function

* Hint: Use %02x for lowercase, %02X for uppercase

*/

void print_hex_byte(unsigned char byte, int uppercase) {

/* YOUR CODE HERE */

}

/*

* print_offset - Print the file offset at the start of each line

*

* TODO: Implement this function

* Hint: Use %08lx for 8-digit lowercase hex with leading zeros

*/

void print_offset(unsigned long offset) {

/* YOUR CODE HERE */

}

/*

* print_hex_column - Print the hex values for one line

*

* buffer: The bytes to print

* count: Number of valid bytes in buffer

* settings: Configuration (group size, uppercase, etc.)

*

* TODO: Implement this function

* Remember to:

* - Print each byte as 2 hex chars

* - Add spaces between groups

* - Handle the case where count < bytes_per_line

*/

void print_hex_column(unsigned char *buffer, size_t count, Settings *settings) {

/* YOUR CODE HERE */

}

/*

* print_padding - Print spaces to align short lines

*

* count: Number of bytes that were printed

* settings: Configuration

*

* TODO: Implement this function

* Calculate how much space the missing bytes would take

*/

void print_padding(size_t count, Settings *settings) {

/* YOUR CODE HERE */

}

/*

* print_ascii_column - Print the ASCII representation

*

* buffer: The bytes to print

* count: Number of valid bytes

*

* TODO: Implement this function

* Print each printable char as-is, non-printable as '.'

*/

void print_ascii_column(unsigned char *buffer, size_t count) {

/* YOUR CODE HERE */

}

/*

* print_line - Print one complete line of hex dump output

*

* TODO: Implement this function

* Call the helper functions in order:

* 1. print_offset

* 2. print_hex_column

* 3. print_padding (if needed)

* 4. print_ascii_column

* 5. Print newline

*/

void print_line(unsigned long offset, unsigned char *buffer,

size_t count, Settings *settings) {

/* YOUR CODE HERE */

}

/*

* hexdump_file - Process and dump an entire file

*

* fp: File pointer (already opened in binary mode)

* settings: Configuration

*

* TODO: Implement the main processing loop

* 1. If skip_offset > 0, seek to that position

* 2. Read bytes_per_line bytes at a time

* 3. Call print_line for each chunk

* 4. Stop when EOF or limit reached

*/

void hexdump_file(FILE *fp, Settings *settings) {

unsigned char *buffer = malloc(settings->bytes_per_line);

if (!buffer) {

perror("malloc");

return;

}

/* YOUR CODE HERE */

/* Handle skip_offset with fseek */

/* Main loop: fread + print_line */

/* Handle limit_bytes */

free(buffer);

}

/*

* parse_args - Parse command-line arguments

*

* TODO: Implement argument parsing using getopt

* Support: -s offset, -l length, -g grouping, -u (uppercase)

*/

int parse_args(int argc, char *argv[], Settings *settings, char **filename) {

int opt;

*filename = NULL;

while ((opt = getopt(argc, argv, "s:l:g:c:u")) != -1) {

switch (opt) {

/* YOUR CODE HERE */

case 's':

/* Skip offset */

break;

case 'l':

/* Limit bytes */

break;

case 'g':

/* Group size */

break;

case 'c':

/* Bytes per line (columns) */

break;

case 'u':

/* Uppercase hex */

break;

default:

return -1;

}

}

if (optind < argc) {

*filename = argv[optind];

}

return 0;

}

void print_usage(const char *progname) {

fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s [-s offset] [-l length] [-g groupsize] "

"[-c cols] [-u] [file]\n", progname);

fprintf(stderr, "Options:\n");

fprintf(stderr, " -s offset Skip to offset before dumping\n");

fprintf(stderr, " -l length Limit output to length bytes\n");

fprintf(stderr, " -g size Group bytes (default: 2)\n");

fprintf(stderr, " -c cols Bytes per line (default: 16)\n");

fprintf(stderr, " -u Use uppercase hex\n");

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

Settings settings;

char *filename;

FILE *fp;

init_settings(&settings);

if (parse_args(argc, argv, &settings, &filename) != 0) {

print_usage(argv[0]);

return 1;

}

/* Open file or use stdin */

if (filename) {

fp = fopen(filename, "rb");

if (!fp) {

perror(filename);

return 1;

}

} else {

fp = stdin;

}

hexdump_file(fp, &settings);

if (fp != stdin) {

fclose(fp);

}

return 0;

}

12. Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem 1: “My hex column is misaligned / ASCII column drifts”

- Why: You didn’t pad missing bytes on the final partial line (or grouping spacing is inconsistent).

- Fix: For each line, print exactly N byte slots (commonly 16). If fewer bytes remain, print spaces in the hex column but still print the ASCII column aligned.

- Quick test: Hexdump a 1-byte file and a 15-byte file; the ASCII column should start in the same place.

Problem 2: “Offsets are wrong after -s (skip) or -l (limit)”

- Why: Offset is a logical “address” in the file. If you skip bytes, the first printed line’s offset should reflect that.

- Fix: Keep a

uint64_t offsetthat starts at skip value and increments bybytes_readeach line. - Quick test:

-s 16should start at offset00000010(hex).

Problem 3: “Bytes above 0x7F print as negative or weird” (C bug)

- Why:

charmay be signed. Values ≥ 128 become negative when promoted toint. - Fix: Treat raw bytes as

unsigned char(oruint8_t) before formatting. - Quick test: Dump a file containing

0xFFand ensure it printsff, not-1orffffffff.

Problem 4: “Printable ASCII detection is wrong”

- Why: Only bytes

0x20..0x7Eare printable ASCII; others should render as.. - Fix: Use

isprint((unsigned char)b)carefully (locale!) or a strict range check. - Quick test:

0x0A(newline) must render as., while0x41renders asA.

Problem 5: “My tool differs from xxd for grouping”

- Why:

xxdhas specific spacing rules for-g(group bytes). - Fix: Decide what you support (e.g., groups of 1, 2, 4). Document your exact formatting rules and keep them consistent.

- Quick test: Verify spacing with

-g 1vs-g 2on the same file.

Problem 6: “Large files are slow”

- Why: Printing is expensive and per-byte I/O kills throughput.

- Fix: Read in blocks (e.g., 4–64 KiB), then format line-by-line; avoid calling

printffor every single byte if performance matters. - Quick test: Dump a multi-megabyte file and ensure performance is reasonable.

13. Testing Strategy

This project is perfect for golden tests: run your tool, capture output, compare to expected output.

- Reference comparison: Compare a subset of your output to

xxdfor the flags you support.- Example: 16 bytes per line, lowercase hex, ASCII

.substitution.

- Example: 16 bytes per line, lowercase hex, ASCII

- Fixture files to generate:

empty.bin(0 bytes)one.bin(1 byte:0x00)all-bytes.bin(bytes0x00..0xFF)hello.bin(ASCII string with newline and NUL embedded)

- Option coverage:

- From filename and from

stdin -sskip (0, 1, 16, file-size-1)-llimit (exactly one line, partial line, beyond file length)-ggrouping (1, 2, 4)

- From filename and from

- Invariants worth asserting (even without matching

xxdexactly):- Offsets increase monotonically by bytes shown per line

- Hex column always prints exactly N slots (or prints consistent padding)

- ASCII column length matches bytes actually shown (with padding rules documented)

14. Definition of Done

- Produces a stable 3-column output: offset, hex bytes, ASCII preview

- Handles arbitrary binary files (no crashes on NUL bytes or non-ASCII data)

- Handles final partial line with correct padding/alignment

- Supports at least one input mode: filename and/or

stdin - Supports at least one “power user” flag (

-sskip or-llimit or grouping) - Uses correct byte handling in C (

unsigned char/uint8_t) to avoid signedness bugs - Includes fixture files + golden tests (or documented manual comparisons to

xxd)

15. Books That Will Help

| Book | Chapter | What You’ll Learn | When to Read |

|---|---|---|---|

| K&R C | Ch 7.1-7.2 | Standard I/O: fopen, fread, printf | Before starting |

| K&R C | Ch 7.5 | Text vs Binary file modes | Before starting |

| K&R C | Ch 7.7 | Error handling with perror | During implementation |

| K&R C | Ch 5.10 | Command-line arguments | When adding flags |

| K&R C | Ch 2.9 | Bitwise operations | For byte manipulation |

| K&R C | Appendix B4 | printf format specifiers | Reference during coding |

| Petzold “Code” | Ch 20 | ASCII encoding history | Background reading |

| Petzold “Code” | Ch 9-10 | Binary/Hex number systems | Review before starting |

| CSAPP 3e | Ch 1.1-1.3 | Files as byte sequences | Understanding context |

| CSAPP 3e | Ch 2.1 | Hex representation | Foundation |

| CSAPP 3e | Ch 10 | Unix I/O | Advanced understanding |

| Advanced: Linux Kernel | File I/O chapters | How file reading really works | Extension reading |

16. Extension Ideas

Extension 1: Add Color Output (ANSI Escape Codes)

Make different byte types visually distinct:

#define ANSI_RED "\x1b[31m"

#define ANSI_GREEN "\x1b[32m"

#define ANSI_YELLOW "\x1b[33m"

#define ANSI_BLUE "\x1b[34m"

#define ANSI_RESET "\x1b[0m"

// Color null bytes in red

// Color printable ASCII in green

// Color high bytes (0x80-0xFF) in yellow

Extension 2: Reverse Operation (Hex to Binary)

Implement myxxd -r that converts hex dump back to binary:

$ ./myxxd file.bin > dump.txt

$ ./myxxd -r dump.txt > file_restored.bin

$ diff file.bin file_restored.bin # Should be identical

Challenges:

- Parse the three-column format

- Handle whitespace and formatting variations

- Verify offset continuity

Extension 3: Diff Mode (Compare Two Files)

Show side-by-side comparison highlighting differences:

$ ./myxxd --diff file1.bin file2.bin

00000000: 4865 6c6c 6f00 | 4865 6c6c 6f01 <- difference at byte 5

00000010: 0102 0304 0506 | 0102 0304 0506

Extension 4: Search Mode (Find Byte Patterns)

Add pattern searching:

$ ./myxxd --find "4865 6c6c 6f" large_file.bin

Match at offset 0x00001234

Match at offset 0x00005678

Extension 5: Binary Patch Mode

Allow in-place modifications:

$ ./myxxd --patch 0x100:48656c6c6f file.bin

# Writes "Hello" at offset 0x100

Extension 6: Entropy Visualization

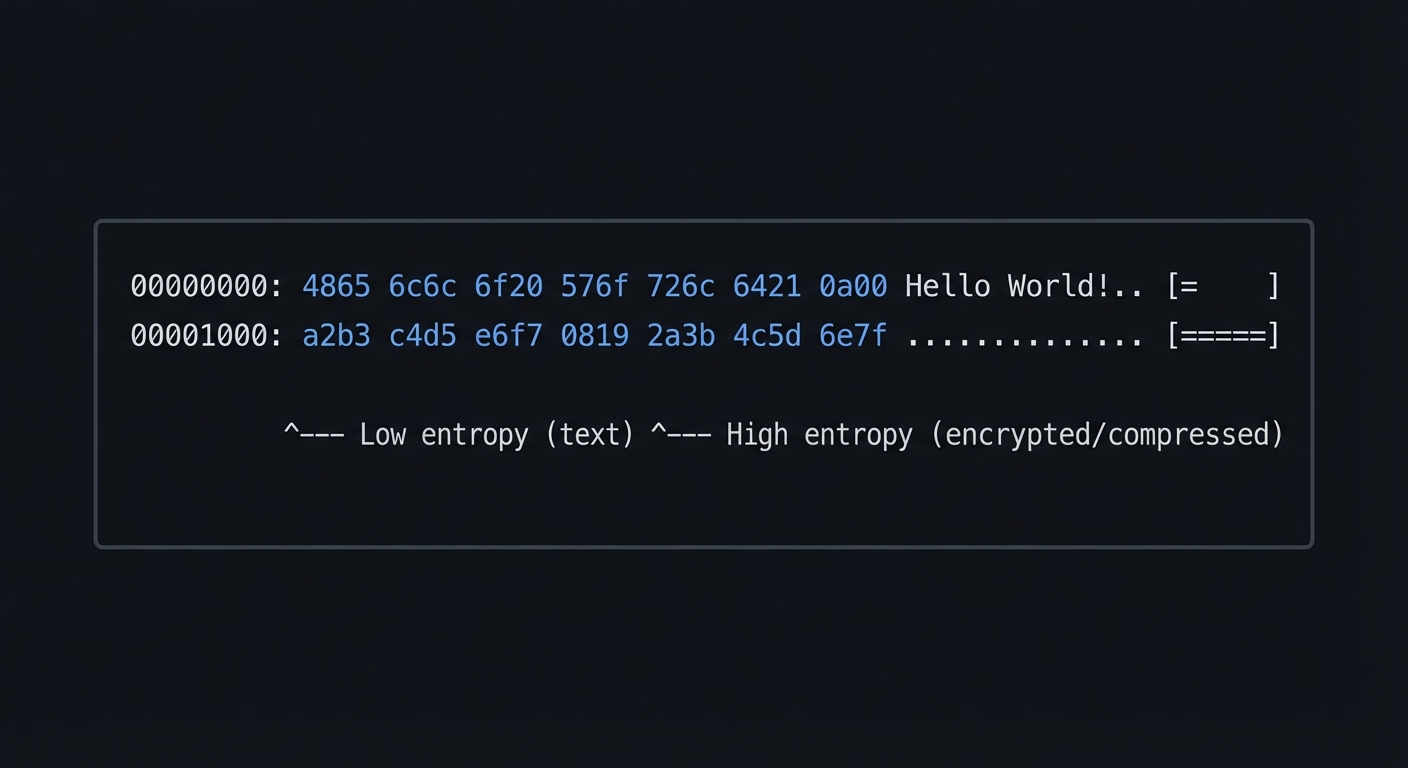

Add a visual entropy indicator to detect encrypted/compressed regions:

00000000: 4865 6c6c 6f20 576f 726c 6421 0a00 Hello World!.. [= ]

00001000: a2b3 c4d5 e6f7 0819 2a3b 4c5d 6e7f .............. [======]

^--- Low entropy (text) ^--- High entropy (encrypted/compressed)

17. Self-Assessment Checklist

Understanding Check

- I can explain why hexadecimal is preferred over binary or decimal for byte display

- I understand the difference between text mode and binary mode file I/O

- I can describe the ASCII printable character range and why we use it

- I know how to decompose a byte into high and low nibbles

- I understand what happens when fread reaches EOF with a partial buffer

Core Implementation

- My program correctly reads files in binary mode

- Offsets are displayed as 8 lowercase hex digits with leading zeros

- Each byte is displayed as exactly 2 hex characters

- Hex bytes are grouped in pairs with spaces between groups

- The ASCII column correctly shows printable chars and dots

- Empty files produce no output (not an error)

- The last line is correctly formatted even with fewer than 16 bytes

Edge Cases

- Files with embedded null bytes are handled correctly

- Files containing only non-printable bytes show all dots in ASCII

- Very large files (>100MB) don’t run out of memory

- My output exactly matches real xxd for test files

- Error messages are shown for non-existent or unreadable files

Command-Line Features

- The

-sflag correctly skips to the specified offset - The

-lflag correctly limits output length - The

-gflag changes byte grouping - The

-cflag changes bytes per line - The

-uflag switches to uppercase hex - Reading from stdin works when no filename is given

Code Quality

- No memory leaks (tested with valgrind or similar)

- No buffer overflows possible

- Error handling is complete (file open, read, memory allocation)

- Code compiles without warnings using

-Wall -Wextra

Interview Readiness

- I can implement the core hex dump from memory

- I can explain my design decisions and tradeoffs

- I can describe real-world uses for a hex dump tool

- I can discuss how I would debug performance issues

- I can extend the tool with new features on request

Verification

Run these tests to verify your implementation:

# Test 1: Compare output to real xxd

./myxxd test_file.bin > mine.txt

xxd test_file.bin > real.txt

diff mine.txt real.txt

# Test 2: Test empty file

touch empty.bin

./myxxd empty.bin # Should produce no output

# Test 3: Test binary file

./myxxd /bin/ls | head -10 # Should show ELF header

# Test 4: Test skip and limit

./myxxd -s 16 -l 32 large_file.bin

# Test 5: Roundtrip (if you implemented -r)

./myxxd original.bin | ./myxxd -r > restored.bin

diff original.bin restored.bin

Key Insights

The hex dump is your X-ray vision. It lets you see through the abstractions of file types, encodings, and applications to the raw bytes underneath. Every security researcher, systems programmer, and reverse engineer relies on this fundamental capability.

Format specifiers are your precision tools. The difference between

%xand%02xis the difference between “f” and “0f”—seemingly small, but crucial for alignment and readability. Master printf and you control exactly how data appears.

Binary mode is non-negotiable. A single translated character can corrupt your analysis. When examining bytes, you must see every byte exactly as it exists on disk. This is why “rb” mode exists.

The last line is always the tricky part. Handling partial data gracefully—whether it’s the last line of a hex dump, the last packet in a stream, or the last record in a file—separates robust code from fragile code.

This tool is your teacher. Once you build it, use it to understand other binary formats. Examine executables, images, compressed files. The patterns you’ll discover will deepen your understanding of how computers really store information.

Completing this capstone project means you’ve mastered the fundamental skill of reading raw binary data. You can now examine any file at its most basic level—the level that all software ultimately works with. This is the foundation for reverse engineering, security analysis, and systems programming.