Functional Programming with TypeScript: Learning Journey

Goal: Master functional programming principles through TypeScript—transforming how you think about code from imperative commands to pure, composable transformations. Learn to eliminate null pointer exceptions, make illegal states unrepresentable, and build complex systems from simple, testable functions that compose like LEGO blocks.

After completing this journey, you’ll understand why companies like Facebook (React), Netflix (RxJS), and Elm use functional patterns. You’ll stop writing for loops and if (x !== null) checks by default. Instead, you’ll see data transformations as pipelines, errors as values, and side effects as explicitly managed monads.

Why Functional Programming Matters in 2025

In 1977, John Backus (creator of FORTRAN) gave his Turing Award lecture titled “Can Programming Be Liberated from the von Neumann Style?” His answer was functional programming. Nearly 50 years later, his vision is becoming reality:

- React (used by Facebook, Netflix, Airbnb) is built on immutability and pure functions

- Redux is a functional state container with 9 million weekly npm downloads

- RxJS brings reactive functional programming to Angular and beyond

- TypeScript itself added features like

readonly, union types, and advanced generics to support FP

Why is FP growing? Because it solves real problems:

Imperative Approach What goes wrong

↓

let total = 0; → Mutation: total changes unpredictably

for (let i = 0; i < arr.length; i++) {

if (arr[i] !== null) { → Null checks everywhere

total += arr[i]; → Hard to test, hard to parallelize

}

}

return total;

Functional Approach What you gain

↓

arr → No mutation: data never changes

.filter(x => x !== null) → Null handling becomes explicit

.reduce((sum, x) => sum + x, 0) → Composable, testable, parallelizable

Every JavaScript framework is moving toward functional patterns. Learning FP isn’t learning an obscure academic concept—it’s learning the future of mainstream programming.

Core Concept Analysis

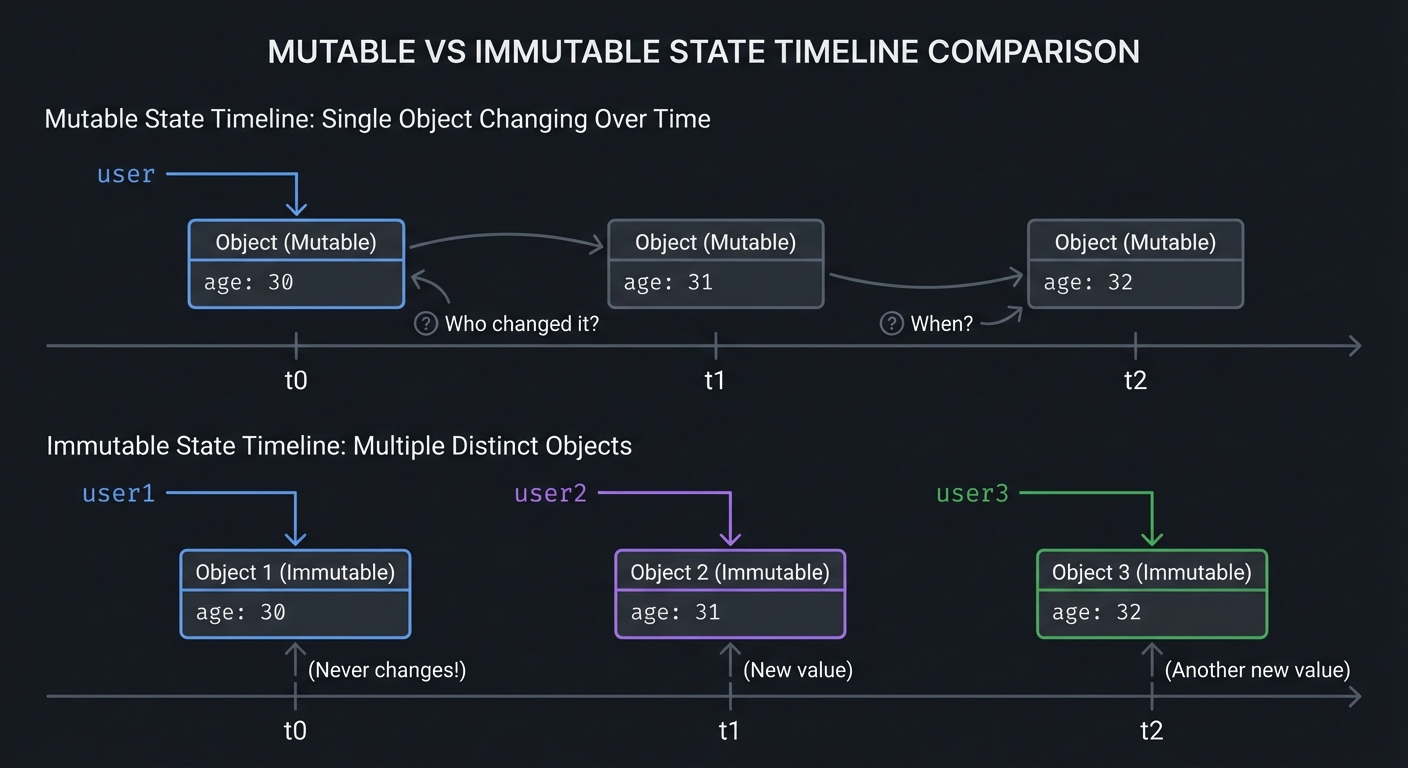

Immutability: The Foundation

Immutability means data never changes after creation. Instead of modifying values, you create new ones:

// Imperative: Mutation (BAD)

const user = { name: "Alice", age: 30 };

user.age = 31; // Original object changed! Who else references it?

// Functional: Immutability (GOOD)

const user = { name: "Alice", age: 30 };

const olderUser = { ...user, age: 31 }; // New object, original untouched

Why this matters:

Mutable State Timeline:

Time → t0 t1 t2

┌────┐ ┌────┐ ┌────┐

user → │age:│ → │age:│ → │age:│

│ 30 │ │ 31 │ │ 32 │

└────┘ └────┘ └────┘

↑ ↑

Who changed it? When?

Immutable State Timeline:

Time → t0 t1 t2

┌────┐ ┌────┐ ┌────┐

user1 → │age:│ │age:│ │age:│

│ 30 │ │ 30 │ │ 30 │ (Never changes!)

└────┘ └────┘ └────┘

┌────┐ ┌────┐

user2 → │age:│ │age:│

│ 31 │ │ 31 │ (New value)

└────┘ └────┘

┌────┐

user3 → │age:│

│ 32 │ (Another new value)

└────┘

Benefits:

- Time Travel: Keep old versions for undo/redo (React’s state history)

- Concurrency: No locks needed if data can’t change

- Debugging: State changes are explicit, traceable

- Testing: Pure functions with immutable data are trivially testable

Pure Functions: Predictability as Power

A pure function has two properties:

- Same input → always same output (referential transparency)

- No side effects (no I/O, no mutation, no randomness)

// Impure: Unpredictable

let count = 0;

function increment() {

count++; // Side effect: mutates global state

return count;

}

increment(); // Returns 1

increment(); // Returns 2 (different result!)

// Pure: Predictable

function add(a: number, b: number): number {

return a + b; // No side effects, no hidden state

}

add(2, 3); // Always returns 5

add(2, 3); // Always returns 5

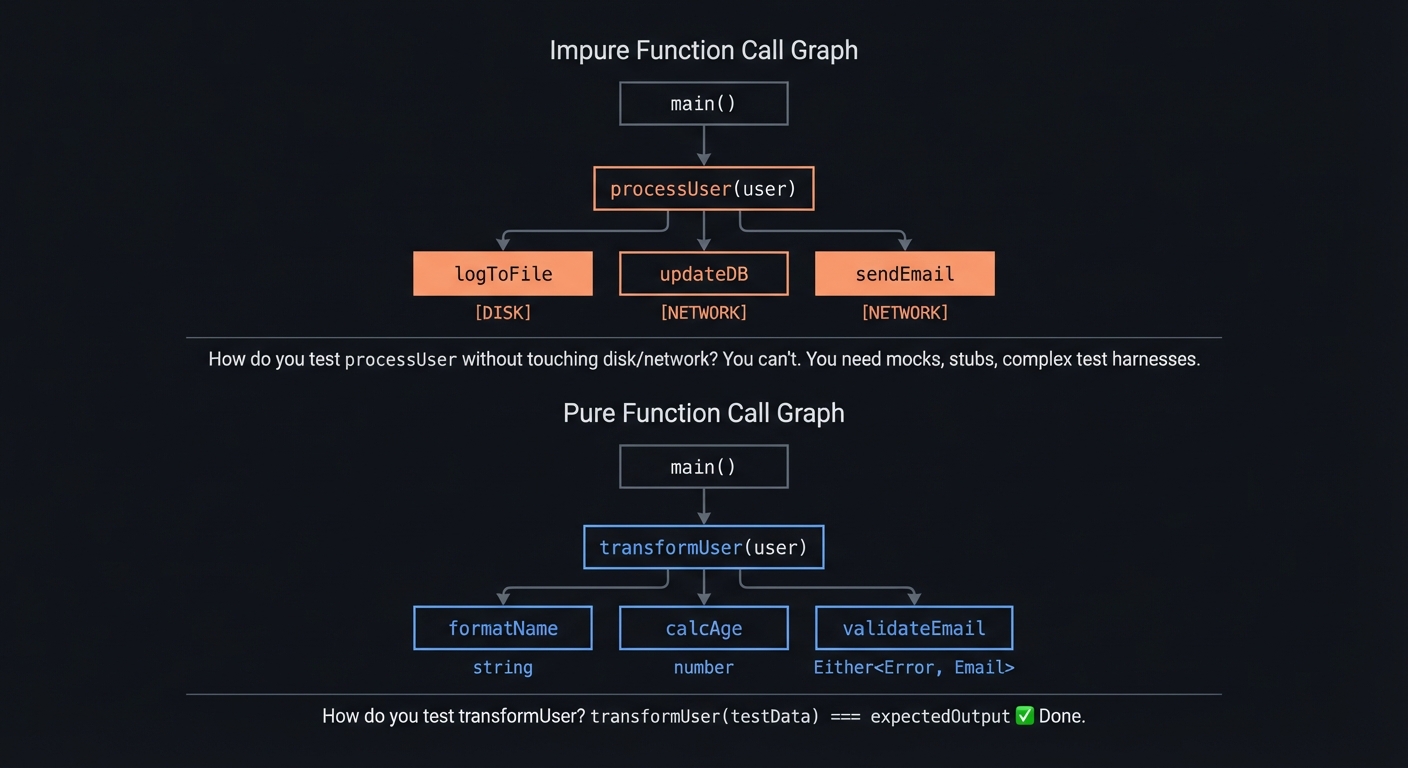

The Hidden Cost of Impurity:

Impure Function Call Graph:

main()

↓

processUser(user)

↓

┌────────┼────────┐

↓ ↓ ↓

logToFile updateDB sendEmail

↓ ↓ ↓

[DISK] [NETWORK] [NETWORK]

How do you test processUser without touching disk/network?

You can't. You need mocks, stubs, complex test harnesses.

Pure Function Call Graph:

main()

↓

transformUser(user)

↓

┌────────┼────────┐

↓ ↓ ↓

formatName calcAge validateEmail

↓ ↓ ↓

string number Either<Error, Email>

How do you test transformUser?

transformUser(testData) === expectedOutput ✓ Done.

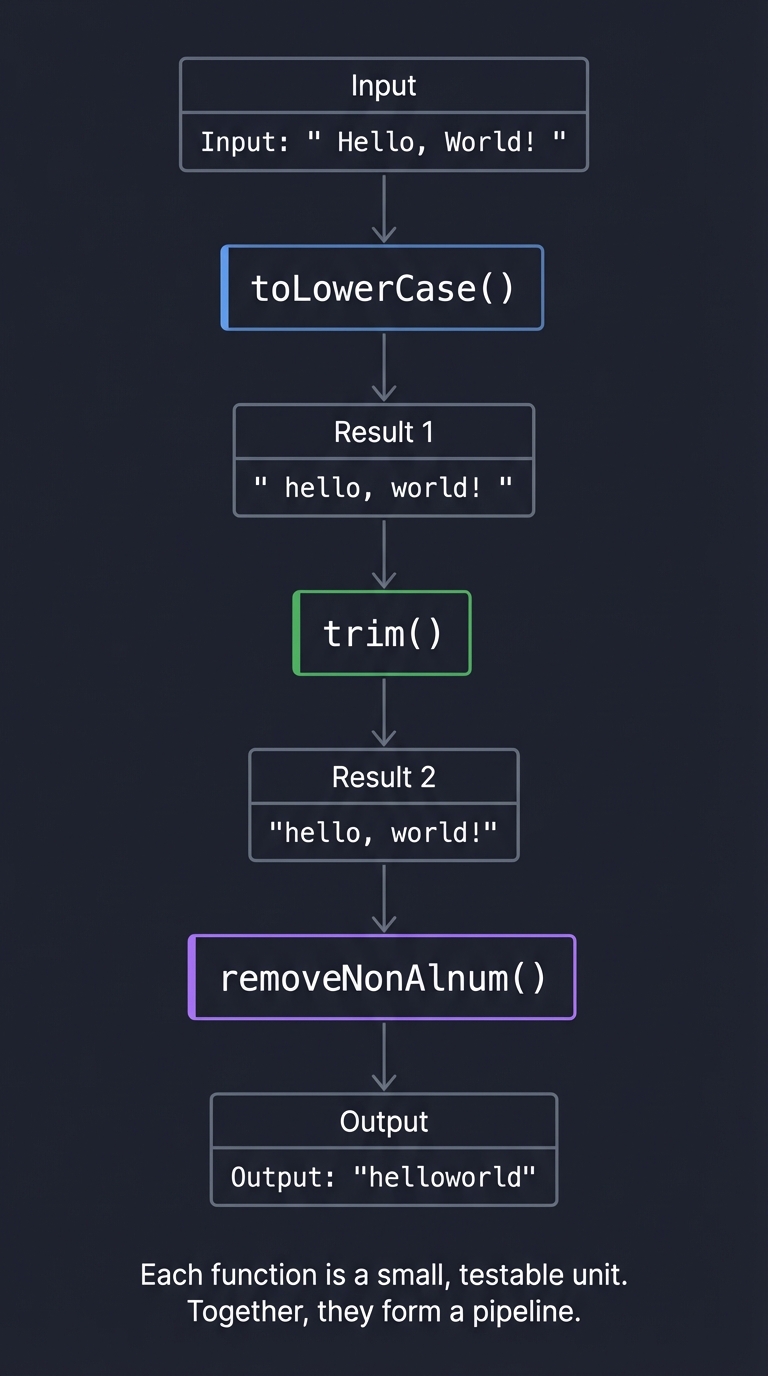

Function Composition: Building Complexity from Simplicity

Composition is the art of combining small functions into larger ones:

// Instead of this monolith:

function processText(text: string): string {

let result = text.toLowerCase();

result = result.trim();

result = result.replace(/[^a-z0-9]/g, '');

return result;

}

// Compose from small pieces:

const toLowerCase = (s: string) => s.toLowerCase();

const trim = (s: string) => s.trim();

const removeNonAlnum = (s: string) => s.replace(/[^a-z0-9]/g, '');

const processText = (text: string) =>

removeNonAlnum(trim(toLowerCase(text)));

// Or with a compose helper (reads right-to-left):

const processText = compose(

removeNonAlnum,

trim,

toLowerCase

);

// Or with pipe (reads left-to-right):

const processText = pipe(

toLowerCase,

trim,

removeNonAlnum

);

Composition Visualized:

Data Flow Through Composition:

Input: " Hello, World! "

↓

toLowerCase()

↓

" hello, world! "

↓

trim()

↓

"hello, world!"

↓

removeNonAlnum()

↓

"helloworld"

↓

Output: "helloworld"

Each function is a small, testable unit.

Together, they form a pipeline.

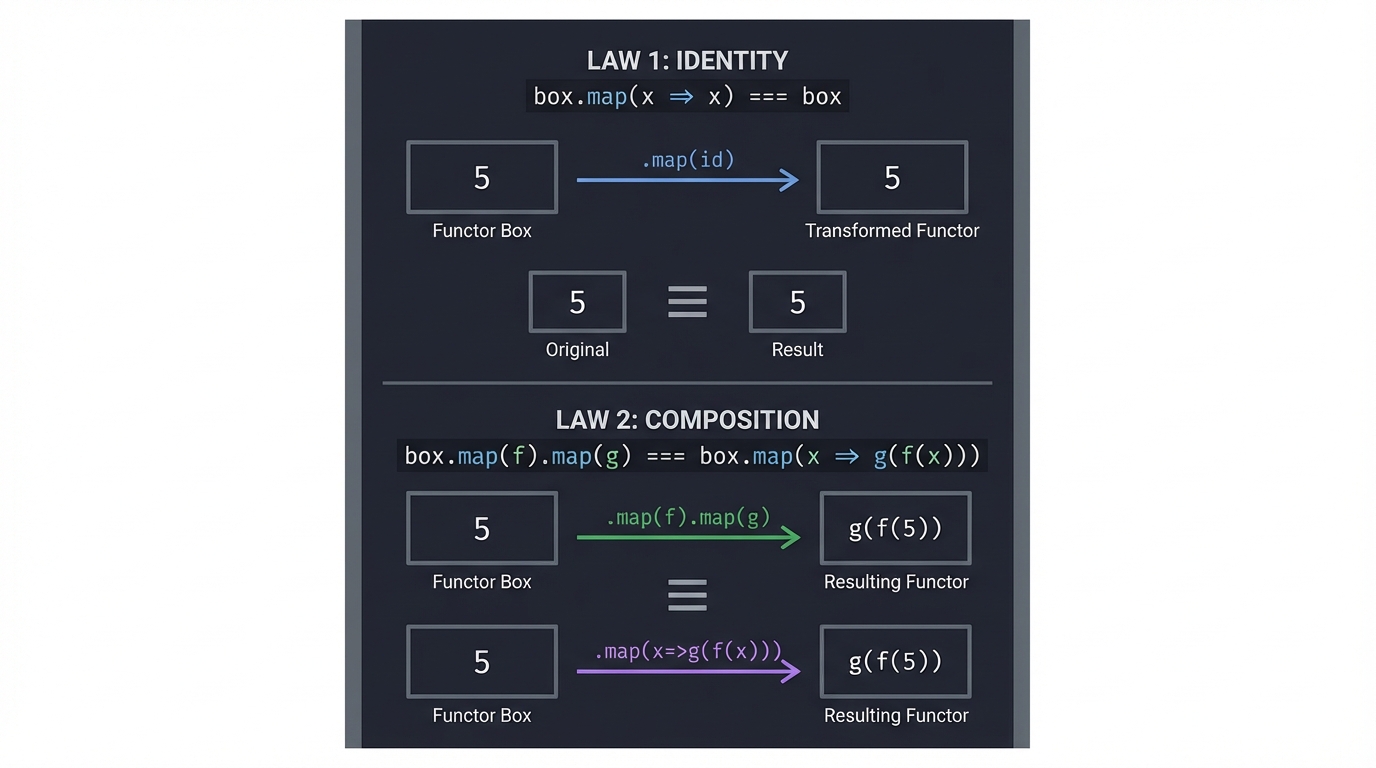

Functors: Mappable Containers

A functor is any type that implements map. It’s a box that holds a value and lets you transform that value without opening the box:

// Arrays are functors:

[1, 2, 3].map(x => x * 2) // [2, 4, 6]

// So is Maybe (Option):

type Maybe<T> = Some<T> | None;

class Some<T> {

constructor(private value: T) {}

map<U>(f: (x: T) => U): Maybe<U> {

return new Some(f(this.value));

}

}

class None {

map<U>(f: any): Maybe<U> {

return new None(); // Do nothing with no value

}

}

// Usage:

const x: Maybe<number> = new Some(5);

const y = x.map(n => n * 2); // Some(10)

const z: Maybe<number> = new None();

const w = z.map(n => n * 2); // None (no explosion!)

Functor Laws Visualized:

Law 1: Identity

box.map(x => x) === box

┌─────┐ ┌─────┐

│ 5 │ .map(id) → │ 5 │

└─────┘ └─────┘

Law 2: Composition

box.map(f).map(g) === box.map(x => g(f(x)))

┌─────┐ ┌─────┐

│ 5 │ .map(f).map(g) → │g(f(5))│

└─────┘ └─────┘

≡

┌─────┐ ┌─────┐

│ 5 │ .map(x=>g(f(x))) → │g(f(5))│

└─────┘ └─────┘

Monads: Handling Context and Effects

A monad is a functor with two additional operations:

of(also calledreturnorpure): Put a value into the monadflatMap(also calledbindorchain): Map a function that returns a monad, then flatten

Maybe Monad: Handling Null/Undefined

class Maybe<T> {

private constructor(private value: T | null) {}

static of<T>(value: T): Maybe<T> {

return new Maybe(value);

}

static none<T>(): Maybe<T> {

return new Maybe<T>(null);

}

isNone(): boolean {

return this.value === null;

}

map<U>(f: (x: T) => U): Maybe<U> {

return this.isNone()

? Maybe.none<U>()

: Maybe.of(f(this.value!));

}

flatMap<U>(f: (x: T) => Maybe<U>): Maybe<U> {

return this.isNone()

? Maybe.none<U>()

: f(this.value!);

}

}

// Without Maybe: Null check hell

function getStreetName(user: User | null): string | null {

if (user === null) return null;

if (user.address === null) return null;

if (user.address.street === null) return null;

return user.address.street.name;

}

// With Maybe: Clean pipeline

function getStreetName(user: Maybe<User>): Maybe<string> {

return user

.flatMap(u => u.address)

.flatMap(a => a.street)

.map(s => s.name);

}

Either Monad: Handling Errors as Values

type Either<E, A> = Left<E> | Right<A>;

class Left<E> {

constructor(readonly value: E) {}

map<B>(f: any): Either<E, B> {

return this as any; // Preserve error

}

flatMap<B>(f: any): Either<E, B> {

return this as any;

}

}

class Right<A> {

constructor(readonly value: A) {}

map<B>(f: (x: A) => B): Either<never, B> {

return new Right(f(this.value));

}

flatMap<E, B>(f: (x: A) => Either<E, B>): Either<E, B> {

return f(this.value);

}

}

// Without Either: Try-catch hell

function processUser(userId: string): User | null {

try {

const user = fetchUser(userId);

if (!user) return null;

const validated = validateUser(user);

if (!validated) return null;

return saveUser(validated);

} catch (e) {

console.error(e); // Lost error details!

return null;

}

}

// With Either: Errors are values

function processUser(userId: string): Either<Error, User> {

return fetchUser(userId)

.flatMap(validateUser)

.flatMap(saveUser);

}

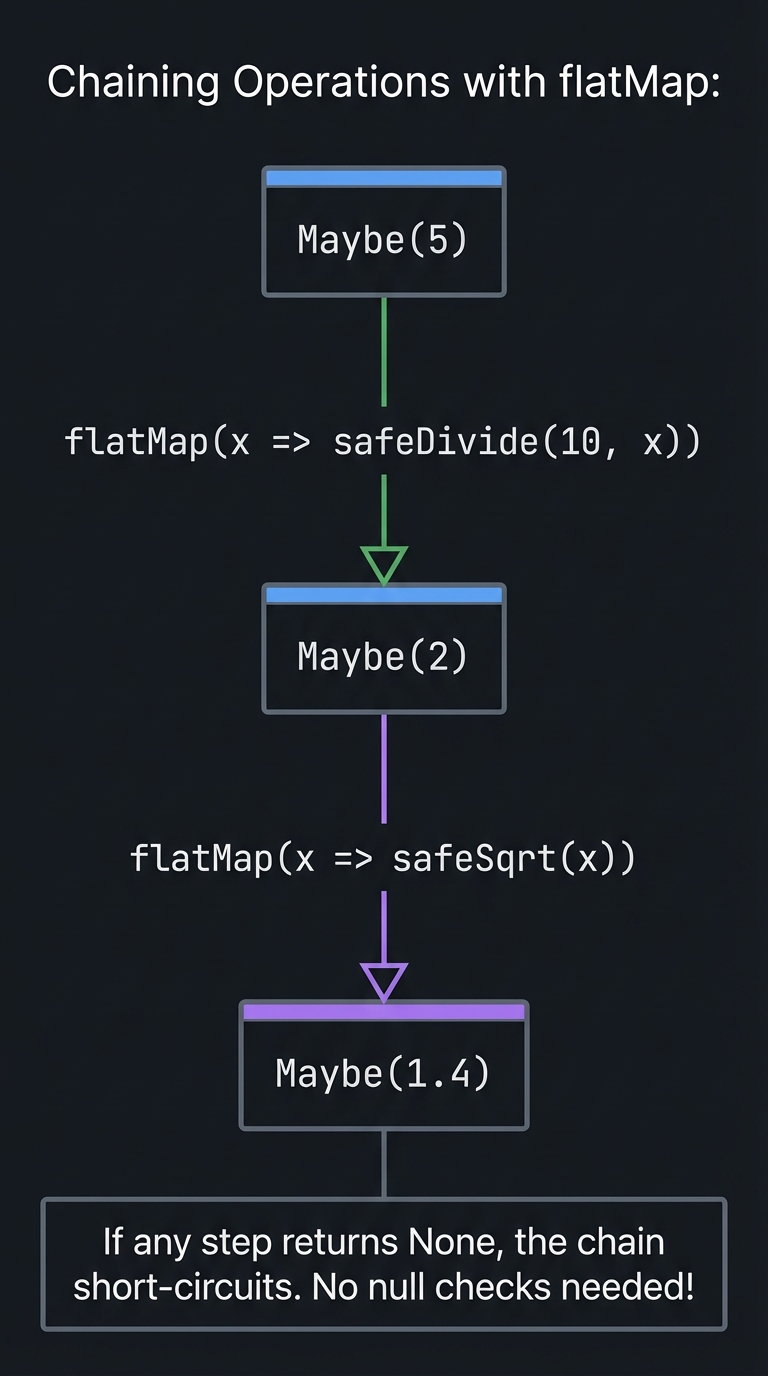

Monad Composition:

Chaining Operations with flatMap:

┌─────────┐

Input → │Maybe(5) │

└────┬────┘

↓ flatMap(x => safeDivide(10, x))

┌────┴────┐

│Maybe(2) │

└────┬────┘

↓ flatMap(x => safeSqrt(x))

┌────┴────┐

│Maybe(1.4)│

└─────────┘

If any step returns None, the chain short-circuits.

No null checks needed!

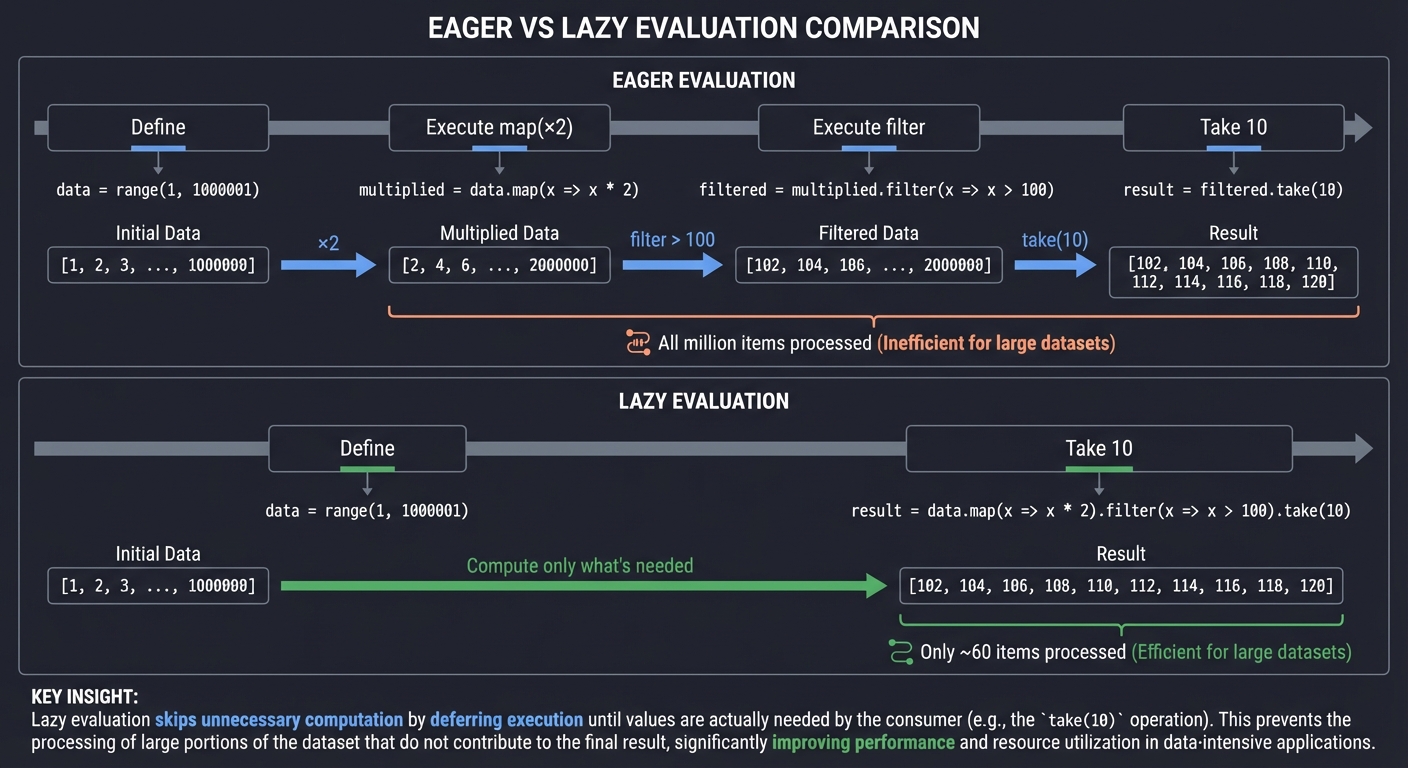

Lazy Evaluation: Infinite Possibilities

Lazy evaluation means computations are deferred until their results are needed:

// Eager: Computes everything immediately

const allNumbers = [1, 2, 3, ...millionMoreNumbers];

const result = allNumbers

.map(x => x * 2) // Process all million

.filter(x => x > 100) // Check all million

.slice(0, 10); // Only need 10!

// Lazy: Compute on demand

class LazyList<T> {

constructor(

private head: T,

private tailFn: () => LazyList<T>

) {}

map<U>(f: (x: T) => U): LazyList<U> {

return new LazyList(

f(this.head),

() => this.tailFn().map(f) // Not computed yet!

);

}

take(n: number): T[] {

if (n === 0) return [];

return [this.head, ...this.tailFn().take(n - 1)];

}

}

// Infinite list (only computes what you take)

function integers(start: number): LazyList<number> {

return new LazyList(start, () => integers(start + 1));

}

const result = integers(1)

.map(x => x * 2) // Not computed yet

.filter(x => x > 100) // Not computed yet

.take(10); // Compute only 10 values!

Lazy Evaluation Timeline:

Eager Evaluation:

Define Execute map(×2) Execute filter Take 10

↓ ↓ ↓ ↓

[1,2,3...]→[2,4,6...]→[102,104,106...]→[102...120]

↑─────────────────────────────↑

All million items processed

Lazy Evaluation:

Define Take 10

↓ ↓

[1,2,3...] → Compute only what's needed

↓

[102, 104, 106, 108, 110, 112, 114, 116, 118, 120]

↑─────────────────────────────────────────────────↑

Only ~60 items processed

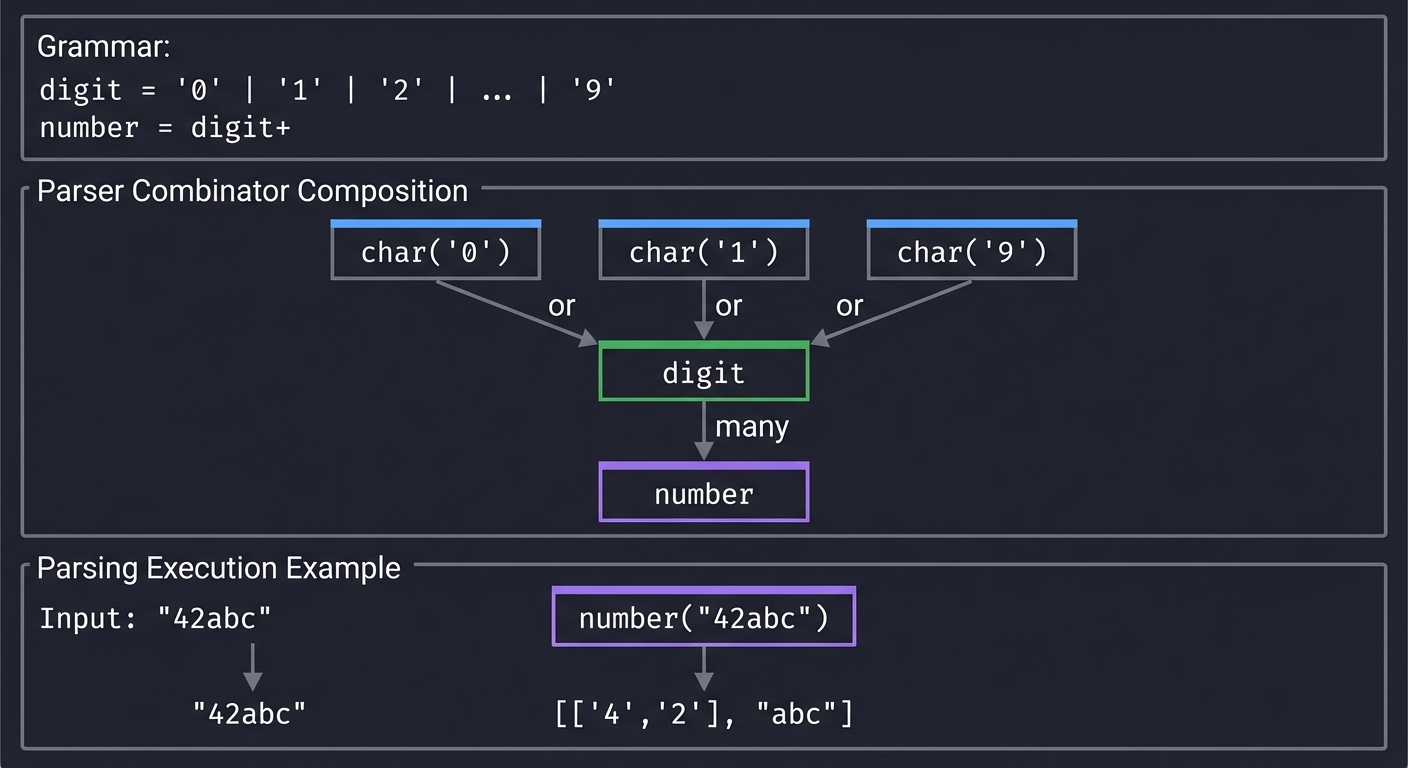

Parser Combinators: Composing Grammars

Parser combinators treat parsers as first-class values that compose:

type Parser<A> = (input: string) => Maybe<[A, string]>;

// Primitive parser: match a single character

function char(c: string): Parser<string> {

return (input: string) => {

if (input[0] === c) {

return Maybe.of([c, input.slice(1)]);

}

return Maybe.none();

};

}

// Combinator: sequence two parsers

function seq<A, B>(p1: Parser<A>, p2: Parser<B>): Parser<[A, B]> {

return (input: string) => {

return p1(input).flatMap(([a, rest1]) =>

p2(rest1).map(([b, rest2]) =>

[[a, b], rest2] as [[A, B], string]

)

);

};

}

// Combinator: choice between parsers

function or<A>(p1: Parser<A>, p2: Parser<A>): Parser<A> {

return (input: string) => {

const result1 = p1(input);

return result1.isNone() ? p2(input) : result1;

};

}

// Build complex parser from simple ones:

const digit = or(char('0'), or(char('1'), char('2'))); // etc.

const number = many(digit); // many = combinator for repetition

Parser Composition:

Grammar: digit = '0' | '1' | '2' | ... | '9'

number = digit+

Parser Combinators:

char('0') char('1') char('9')

↓ ↓ ↓

└────────or──┴────or──────┘

↓

digit

↓

many

↓

number

Input: "42abc"

↓

number("42abc")

↓

[['4','2'], "abc"]

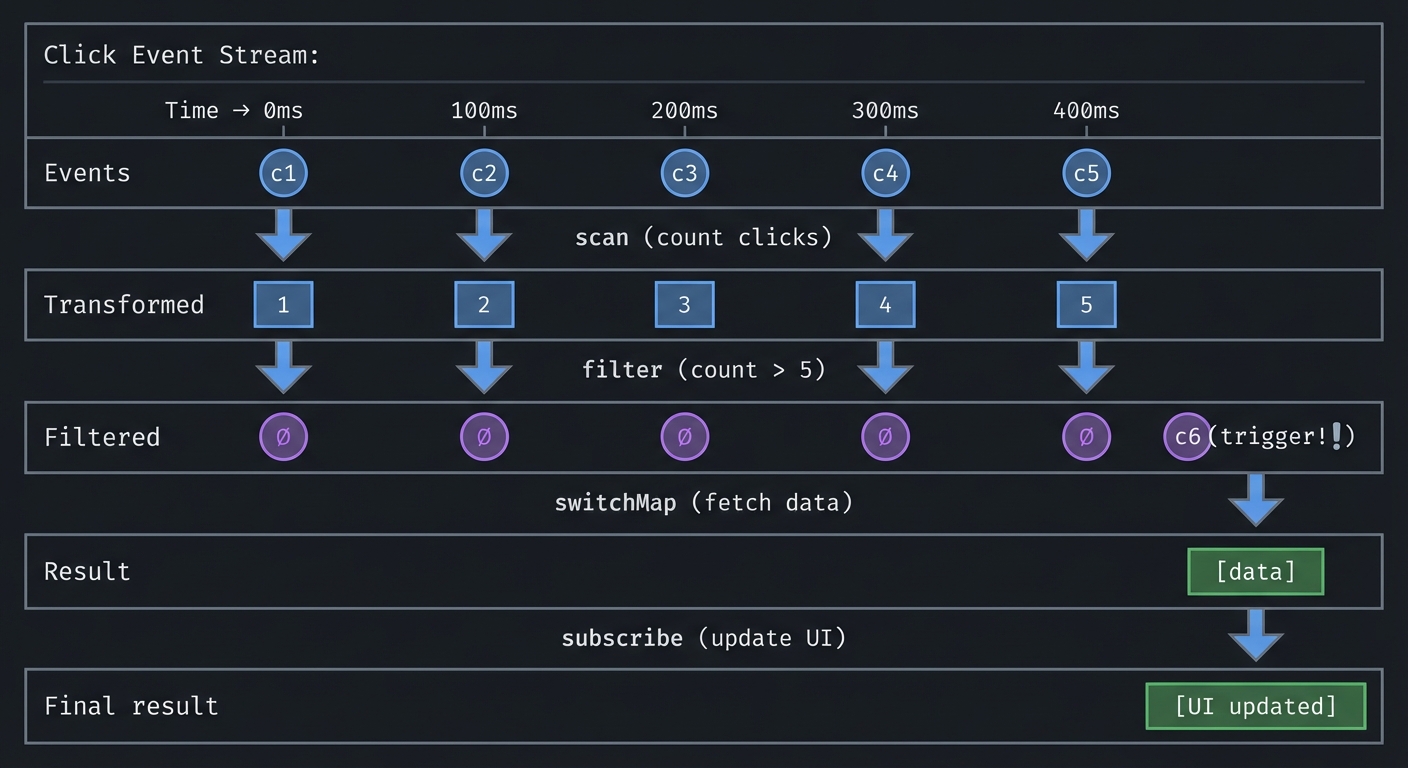

Reactive Programming: Events as Streams

Reactive programming treats events as infinite streams you can map, filter, and combine:

// Traditional event handling: Callback hell

button.addEventListener('click', (e) => {

if (clickCount > 5) {

fetch('/api/data').then(data => {

updateUI(data);

}).catch(err => {

// Error handling scattered everywhere

});

}

});

// Reactive: Events as streams

const clicks = fromEvent(button, 'click');

const validClicks = clicks.pipe(

scan((count, _) => count + 1, 0),

filter(count => count > 5)

);

const data = validClicks.pipe(

switchMap(() => fromFetch('/api/data')),

catchError(err => of({ error: err }))

);

data.subscribe(updateUI);

Stream Composition:

Click Event Stream:

Time → 0ms 100ms 200ms 300ms 400ms

↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓

c1 c2 c3 c4 c5

↓

scan (count clicks)

↓

1 2 3 4 5

↓

filter (count > 5)

↓

∅ ∅ ∅ ∅ ∅ c6(trigger!)

↓

switchMap (fetch data)

↓

[data]

↓

subscribe (update UI)

↓

[UI updated]

The Mathematical Foundation

Functional programming isn’t just “programming without loops.” It’s based on rigorous mathematical foundations:

Category Theory Connection

Category Theory Concepts → FP Implementations

Objects → Types (number, string, User)

Morphisms (arrows) → Functions (f: A → B)

Identity morphism → Identity function (x => x)

Composition (g ∘ f) → compose(g, f)

Functors → Array.map, Maybe.map

Natural transformations → Polymorphic functions

Monads → Maybe, Either, IO, Promise

Algebraic Data Types

Product Types (AND):

type User = {

name: string, ← Has name AND email AND age

email: string,

age: number

}

Sum Types (OR):

type Result<T, E> =

| { type: 'success', value: T } ← Success OR Error

| { type: 'error', error: E }

Why this matters:

Product types = All fields required (total data)

Sum types = Exactly one variant (exhaustive patterns)

Together = "Make illegal states unrepresentable"

Real-World Impact: Why Companies Use FP

Facebook/Meta: React

React is built on immutability and pure functions:

- Components are pure functions of props and state

- State updates create new objects (immutability)

- Virtual DOM diffing relies on referential equality

// React component is a pure function

function UserProfile({ user }: { user: User }) {

return <div>{user.name}</div>;

}

// State updates are immutable

const [state, setState] = useState({ count: 0 });

setState({ ...state, count: state.count + 1 });

Netflix: RxJS for Async

Netflix uses RxJS to handle complex async scenarios:

- Debouncing search inputs

- Canceling stale requests

- Retry logic with exponential backoff

const search$ = fromEvent(input, 'keyup').pipe(

debounceTime(300), // Wait for typing pause

map(e => e.target.value),

distinctUntilChanged(), // Skip duplicates

switchMap(term => // Cancel previous request

ajax.getJSON(`/api/search?q=${term}`).pipe(

retry(3) // Retry on failure

)

)

);

Elm/Haskell Companies: Zero Runtime Exceptions

Companies like NoRedInk (education platform) use Elm in production and report zero runtime exceptions in years of production use. Why? The type system + FP patterns make entire classes of bugs impossible.

Concept Summary Table

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize |

|---|---|

| Immutability | Data never changes. Create new values instead of modifying old ones. Enables time travel, safe concurrency, predictable debugging. |

| Pure Functions | Same input → same output, no side effects. Testability, composability, parallelizability all flow from purity. |

| Function Composition | Build complex operations by combining simple ones. compose and pipe are your Swiss Army knives. |

| Functors | Containers you can map over. Arrays, Maybe, Either, IO—all are functors. Understanding map unlocks all of them. |

| Monads | Functors with flatMap (chain). Handle context (Maybe, Either), sequencing (IO), async (Promise). “A monad is just a monoid in the category of endofunctors.” |

| Lazy Evaluation | Defer computation until results are needed. Enables infinite data structures, performance optimization through fusion. |

| Parser Combinators | Treat parsers as first-class values. Compose small parsers into complex grammars. Monadic structure emerges naturally. |

| Reactive Programming | Events as streams. Map, filter, merge, debounce—all the functional patterns apply to time-varying values. |

| Algebraic Data Types | Product types (AND), sum types (OR). Make illegal states unrepresentable through types. |

| Type-Driven Development | Let types guide implementation. If it type-checks, it often works. TypeScript’s type system is your safety net. |

Deep Dive Reading by Concept

This section maps each concept to specific books and chapters for deeper understanding. Read these before or alongside the projects to build strong mental models.

Functional Programming Foundations

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Why FP matters | Professor Frisby’s Mostly Adequate Guide to Functional Programming — Ch. 1: “What Ever Are We Doing?” |

| Pure functions and immutability | Hands-On Functional Programming with TypeScript by Remo H. Jansen — Ch. 2: “Mastering Functions” |

| Function composition fundamentals | Professor Frisby’s Mostly Adequate Guide — Ch. 5: “Coding by Composing” |

| Currying and partial application | Functional-Light JavaScript by Kyle Simpson — Ch. 3: “Managing Function Inputs” |

| Point-free style | Professor Frisby’s Mostly Adequate Guide — Ch. 5: “Pointfree” section |

TypeScript for Functional Programming

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Advanced TypeScript types for FP | Effective TypeScript (2nd Edition) by Dan Vanderkam — Item 28: “Use Type Assertions and Non-Null Assertions Sparingly” & Item 33: “Prefer More Precise Variants of any to Plain any” |

| Generics and higher-kinded types | Programming TypeScript by Boris Cherny — Ch. 6: “Advanced Types” |

| Type-level programming | Effective TypeScript — Item 50: “Consider Tagged Unions for Disjoint Data” |

| Readonly and immutability in TypeScript | Effective TypeScript — Item 17: “Use readonly to Avoid Errors Associated with Mutation” |

Functors and Applicatives

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| What is a Functor | Professor Frisby’s Mostly Adequate Guide — Ch. 8: “Tupperware” |

| Functor laws and intuition | Hands-On Functional Programming with TypeScript — Ch. 6: “Functors” |

| Applicative functors | Professor Frisby’s Mostly Adequate Guide — Ch. 10: “Applicative Functors” |

| Practical applicatives in TypeScript | Functional Programming in TypeScript (fp-ts documentation) — “Applicative” section |

Monads Deep Dive

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Maybe/Option monad intuition | Professor Frisby’s Mostly Adequate Guide — Ch. 9: “Monadic Onions” |

| Either monad for error handling | Hands-On Functional Programming with TypeScript — Ch. 7: “Monads” (Either section) |

| IO monad for side effects | Functional Programming in JavaScript by Luis Atencio — Ch. 8: “Managing Asynchrony with Monads” |

| Promise as a monad | Professor Frisby’s Mostly Adequate Guide — Ch. 9: “Monads” (Futures section) |

| Monad laws and why they matter | Haskell Programming from First Principles — Ch. 18: “Monad” (highly theoretical but worth it) |

| Practical monads in TypeScript | Hands-On Functional Programming with TypeScript — Ch. 7: “Monads” (complete chapter) |

Parser Combinators

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Parser combinator fundamentals | Monadic Parser Combinators by Graham Hutton and Erik Meijer (research paper—freely available) |

| Building parsers functionally | Programming Language Foundations in Agda by Philip Wadler — Part 2: “Parser Combinators” |

| Applicative vs Monadic parsing | Parser Combinators in TypeScript (tutorial series available online) |

| Error handling in parsers | Hands-On Functional Programming with TypeScript — Ch. 10: “Parser Combinators” |

Lazy Evaluation and Streams

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Lazy evaluation basics | Haskell Programming from First Principles — Ch. 27: “Non-strictness” |

| Infinite data structures | Professor Frisby’s Mostly Adequate Guide — Ch. 8: “Lazy Lists” section |

| Stream processing | Functional Programming in JavaScript by Luis Atencio — Ch. 7: “Functional Optimizations” |

| Generators and lazy sequences | JavaScript: The Definitive Guide by David Flanagan — Ch. 12: “Iterators and Generators” |

Reactive Programming

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Observables and RxJS fundamentals | RxJS in Action by Paul P. Daniels and Luis Atencio — Ch. 1-3: “RxJS Fundamentals” |

| Stream composition patterns | Hands-On Functional Programming with TypeScript — Ch. 9: “Functional Reactive Programming” |

| Backpressure and flow control | RxJS in Action — Ch. 7: “Error Handling and Recovery” |

| Functional reactive UI patterns | Reactive Design Patterns by Roland Kuhn — Ch. 2: “A Walk-through of Reactive” |

Algebraic Data Types

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Sum and product types | Domain Modeling Made Functional by Scott Wlaschin — Ch. 4: “Modeling with Types” |

| Making illegal states unrepresentable | Domain Modeling Made Functional — Ch. 5: “Integrity and Consistency” |

| Pattern matching in TypeScript | Programming TypeScript — Ch. 6: “Discriminated Union Types” |

| Type-safe state machines | Hands-On Functional Programming with TypeScript — Ch. 4: “Algebraic Data Types” |

Category Theory (Optional but Enlightening)

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Category theory for programmers | Category Theory for Programmers by Bartosz Milewski — Ch. 1-3: “Category Basics” (free online) |

| Functors, applicatives, monads from category theory | Category Theory for Programmers — Ch. 6-10 |

| Natural transformations | Category Theory for Programmers — Ch. 10: “Natural Transformations” |

Essential Reading Order

For maximum comprehension, read in this sequence:

- Foundation (Week 1):

- Professor Frisby’s Mostly Adequate Guide Ch. 1, 5 (free online)

- Hands-On Functional Programming with TypeScript Ch. 1-2

- Practice: Projects 1-2 (Immutable Todo, Pipe Processor)

- Functors and Composition (Week 2):

- Professor Frisby’s Mostly Adequate Guide Ch. 8

- Hands-On Functional Programming with TypeScript Ch. 6

- Practice: Project 2-3 (Pipe Processor, Maybe Monad)

- Monads (Week 3):

- Professor Frisby’s Mostly Adequate Guide Ch. 9-10

- Hands-On Functional Programming with TypeScript Ch. 7

- Practice: Projects 3-4 (Maybe Monad, Either Validator)

- Advanced Patterns (Week 4+):

- Hands-On Functional Programming with TypeScript Ch. 9-10 (Reactive, Parsers)

- RxJS in Action Ch. 1-3

- Practice: Projects 5-8 (Parser, Streams, IO, Reactive UI)

- Mastery (Ongoing):

- Domain Modeling Made Functional (entire book)

- Category Theory for Programmers (for deep understanding)

Project Comparison Table

| Project | Difficulty | Time | Depth of Understanding | Fun Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Immutable Todo | Beginner | Weekend | ⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐ |

| 2. Pipe Processor | Beginner | Weekend | ⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐ |

| 3. Maybe Monad | Intermediate | 1 Week | ⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ |

| 4. Either Validator | Intermediate | 1-2 Weeks | ⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ |

| 5. JSON Parser | Expert | 2-3 Weeks | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ |

| 6. Lazy Streams | Advanced | 2 Weeks | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ |

| 7. IO Handler | Advanced | 1 Week | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐ |

| 8. Reactive UI | Master | 2-3 Weeks | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ |

Recommendation

Based on learning Functional Programming deeply, I recommend this progression:

- Start with Project 1 (Immutable Todo) and Project 2 (Pipe Processor). These rewrite your brain’s “default mode” from imperative loops to data transformations. You can do these quickly.

- Move to Project 3 (Maybe) and 4 (Either). This is the biggest ROI. You will immediately start writing safer code in your day job. Null checks disappear.

- Tackle Project 5 (JSON Parser) if you want to be a wizard. It connects everything: recursion, monads, and high-level composition. It’s hard but incredibly rewarding.

Final Overall Project: The Declarative Spreadsheet Engine

- File: FUNCTIONAL_PROGRAMMING_TYPESCRIPT_LEARNING_PROJECTS.md

- Main Programming Language: TypeScript

- Difficulty: Master

What you’ll build: A spreadsheet engine (like Excel’s core) running in the browser.

Why it integrates everything:

- Immutability: Every cell update produces a new grid state (Undo/Redo becomes trivial).

- Parsing: You need a Parser Combinator (Project 5) to parse formulas like

=SUM(A1:A5) + B2. - Reactivity: Cells are Observables (Project 8). If A1 changes, B1 (which depends on A1) must update automatically.

- Error Handling: Formulas can fail (

=5/0). You need Either (Project 4) to propagate errors without crashing. - Lazy Evaluation: You can support infinite ranges or huge datasets using Streams (Project 6).

Real World Outcome:

A web app where you type =A1+1 in cell B1, and watching it update live as you type in A1. You can hit Ctrl+Z to undo perfectly.

Summary

This learning path covers Functional Programming through 8 hands-on projects. Here’s the complete list:

| # | Project Name | Main Language | Difficulty | Time Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Immutable Todo List | TypeScript | Beginner | Weekend |

| 2 | The “Pipe” Text Processor | TypeScript | Beginner | Weekend |

| 3 | The “Maybe” Null Handler | TypeScript | Intermediate | 1 Week |

| 4 | The “Either” Validation Lib | TypeScript | Intermediate | 1-2 Weeks |

| 5 | Functional JSON Parser | TypeScript | Expert | 2-3 Weeks |

| 6 | Lazy Stream Library | TypeScript | Advanced | 2 Weeks |

| 7 | The “IO” Effect Handler | TypeScript | Advanced | 1 Week |

| 8 | Functional Reactive UI | TypeScript | Master | 2-3 Weeks |

Recommended Learning Path

For beginners: Start with projects #1, #2, #3. For intermediate: Jump to projects #3, #4, #7. For advanced: Focus on projects #5, #6, #8.

Expected Outcomes

After completing these projects, you will:

- Stop using

forloops and mutation by default. - See

nullandundefinedas problems to be solved with Types, not Checks. - Understand how to build complex systems by gluing small, pure functions together.

- Be able to implement Redux, RxJS, or Parser logic from scratch.

You’ll have built 8 working projects that demonstrate deep understanding of Functional Programming from first principles.

Project 3: The “Maybe” Null Handler

Build a Maybe monad from scratch to eliminate null/undefined checks.

What You’ll Build

A complete Maybe monad implementation with:

- Type-safe container for optional values

- Chainable operations (map, flatMap, filter)

- Pattern matching capabilities

- Integration with real-world API calls

Real World Outcome

You’ll build a TypeScript library and a demonstration application that shows the Maybe monad in action. Here’s exactly what you’ll see:

1. Command Line Demo

$ npm run demo

=== Maybe Monad Demo ===

[Test 1: Safe Division]

Result of 10 / 2: Just(5)

Result of 10 / 0: Nothing

[Test 2: User Lookup Chain]

Looking up user with ID 123...

User found: Just({ id: 123, name: "Alice", email: "alice@example.com" })

Getting email: Just("alice@example.com")

Email domain: Just("example.com")

Looking up user with ID 999...

User found: Nothing

Getting email: Nothing

Email domain: Nothing

[Test 3: API Call with Maybe]

Fetching user from API...

Success: Just({ username: "johndoe", posts: 42 })

Posts count: Just(42)

Network error simulation:

Error: Nothing

Posts count: Nothing

[Test 4: Chaining Operations]

Original value: 5

After map(x => x * 2): Just(10)

After map(x => x + 3): Just(13)

After filter(x => x > 15): Nothing

After orElse(100): Just(100)

2. TypeScript Type Safety in Your Editor

When you open your editor, you’ll see:

// WITHOUT Maybe - TypeScript can't help you

function getUserEmail(userId: number): string | null {

const user = findUser(userId); // Could be null

if (!user) return null;

if (!user.email) return null; // More null checks!

return user.email;

}

// WITH Maybe - Compiler forces you to handle absence

function getUserEmail(userId: number): Maybe<string> {

return findUser(userId) // Maybe<User>

.flatMap(user => user.email) // Maybe<string>

.map(email => email.toLowerCase());

}

// TypeScript won't let you access the value directly!

const email = getUserEmail(123);

// email.toUpperCase(); // ❌ Compiler error!

// You MUST handle both cases

email.match({

just: (value) => console.log(value), // ✅ Safe

nothing: () => console.log("No email") // ✅ Handles missing case

});

3. Visual Test Suite Output

$ npm test

Maybe Monad Implementation

✓ Just wraps a value

✓ Nothing represents absence

✓ map applies function to Just

✓ map does nothing to Nothing

✓ flatMap chains Maybe-returning functions

✓ flatMap short-circuits on Nothing

✓ filter keeps values that pass predicate

✓ filter turns failed predicate into Nothing

✓ orElse provides default for Nothing

✓ orElse keeps Just value unchanged

Real World Scenarios

✓ Safe array access with Maybe

✓ Safe property access on objects

✓ Chained database lookups

✓ API response handling

✓ Form validation with optional fields

15 passing (23ms)

4. Browser Demo (Optional Web App)

If you build the optional web interface, you’ll see a single-page app where:

- Text input: “Enter user ID”

- Button: “Lookup User”

- Results panel shows:

- If user exists: Card with user details (name, email, posts)

- If user doesn’t exist: Friendly “User not found” message

- Loading state: Spinner

- All without a single

if (value === null)check!

The key insight: You never write null checks. The Maybe monad forces you to handle both cases through its API.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How can I make null/undefined values impossible to ignore, using the type system instead of runtime checks?”

Before you write code, sit with this question. In JavaScript/TypeScript, null and undefined are everywhere. Tony Hoare, who invented null references, called them his “billion-dollar mistake.” Why?

Because this compiles:

const user = findUser(123); // Could return null

console.log(user.name); // Runtime crash if null!

The compiler doesn’t force you to check. Maybe monads solve this by making absence explicit in the type system. You can’t access the value without handling the “nothing” case first.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

1. What is a Functor?

- How does

mapwork on arrays? ([1,2,3].map(x => x * 2)) - What’s the pattern: “Apply a function to value(s) inside a container”

- Why is this useful for Maybe?

- Book Reference: “Learn You a Haskell for Great Good!” Ch. 11 - Miran Lipovaca

2. The Monad Laws

- Left identity:

Just(x).flatMap(f)equalsf(x) - Right identity:

m.flatMap(Just)equalsm - Associativity: Chaining order doesn’t matter

- Why do these laws matter? (They ensure predictable behavior)

- Book Reference: “Functional Programming in Scala” Ch. 11 - Chiusano & Bjarnason

3. TypeScript Generics

- What does

Maybe<T>mean? - How do you preserve type information through transformations?

- What’s the difference between

Maybe<string>andMaybe<number>? - Book Reference: “Programming TypeScript” Ch. 4 - Boris Cherny

4. Null vs Undefined vs Absence

- What’s the semantic difference between null and undefined?

- Why is

| null | undefinedeverywhere in TypeScript? - How does Maybe unify these concepts?

- Book Reference: “Effective TypeScript” Items 13-14 - Dan Vanderkam

5. Railway-Oriented Programming

- What does it mean to “stay on the happy path”?

- How do transformations short-circuit on Nothing?

- Why is this better than nested if statements?

- Article: “Railway Oriented Programming” by Scott Wlaschin

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

1. Type Representation

- How do you represent “has value” vs “no value” in TypeScript?

- Should you use a class, interface, or discriminated union?

- How do you make the two cases (Just/Nothing) mutually exclusive?

2. The Map Function

- What’s the signature?

map<U>(fn: (value: T) => U): Maybe<U> - What happens when you map over Nothing?

- How do you preserve the Maybe container while transforming the value?

3. FlatMap vs Map

- When do you use

flatMapinstead ofmap? - What happens if you nest Maybes? (

Maybe<Maybe<T>>) - How does flatMap prevent this nesting?

4. Pattern Matching

- How does a user extract the value safely?

- Should you provide

.getOrElse(default)or.match({ just, nothing })? - What’s more type-safe?

5. Interop with Existing Code

- How do you convert

null | TtoMaybe<T>? - How do you go back from

Maybe<T>toT | null? - When should you use each?

Thinking Exercise

Before coding, trace this by hand:

// Given this Maybe implementation (you'll build it)

class Just<T> {

constructor(private value: T) {}

map<U>(fn: (val: T) => U): Maybe<U> {

return new Just(fn(this.value));

}

}

class Nothing {

map<U>(fn: any): Maybe<U> {

return new Nothing();

}

}

type Maybe<T> = Just<T> | Nothing;

// Trace this execution step-by-step:

const result = Just(5)

.map(x => x * 2) // Step 1: What's the value?

.map(x => x + 3) // Step 2: What's the value?

.map(x => x > 100 ? x : null) // Step 3: What happens with null?

.map(x => x.toString()); // Step 4: Will this crash?

Questions while tracing:

- What’s inside the Maybe after each map?

- At step 3, you return null inside a Just. Is this a problem?

- How would you handle step 3 properly with Maybe?

- Draw a diagram of the data flow through the chain

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

Conceptual Questions:

- “What problem does the Maybe monad solve?”

- “Explain the difference between map and flatMap with examples.”

- “What are the monad laws and why do they matter?”

- “When would you NOT use Maybe?”

- “How is Maybe different from null/undefined?”

Coding Questions:

- “Implement a function that safely gets nested object properties using Maybe.”

- “Write a sequence function:

sequence([Maybe<A>]): Maybe<[A]>” - “How would you make an async version (AsyncMaybe)?”

- “Implement Maybe.traverse for arrays”

- “Write a parser that returns Maybe instead of throwing”

Design Questions:

- “Should Maybe.Nothing be a singleton? Why or why not?”

- “How do you handle side effects in Maybe.map?”

- “Can Maybe replace all null checks in a codebase?”

- “Compare Maybe to Optional in Java or Option in Scala”

- “How does Maybe compose with other monads?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with the Types

Define the shape first:

interface Just<T> {

readonly _tag: 'Just';

readonly value: T;

}

interface Nothing {

readonly _tag: 'Nothing';

}

type Maybe<T> = Just<T> | Nothing;

The _tag field enables discriminated unions. TypeScript will narrow types for you!

Hint 2: Implement Constructors

const just = <T>(value: T): Maybe<T> => ({

_tag: 'Just',

value

});

const nothing = <T = never>(): Maybe<T> => ({

_tag: 'Nothing'

});

Notice: nothing() doesn’t need a value, but still needs a type parameter for map signatures.

Hint 3: Map Implementation

const map = <T, U>(

fn: (value: T) => U

) => (maybe: Maybe<T>): Maybe<U> => {

switch (maybe._tag) {

case 'Just':

return just(fn(maybe.value));

case 'Nothing':

return nothing();

}

};

This is a curried function. You can also implement as methods on classes.

Hint 4: FlatMap Prevents Nesting

const flatMap = <T, U>(

fn: (value: T) => Maybe<U>

) => (maybe: Maybe<T>): Maybe<U> => {

switch (maybe._tag) {

case 'Just':

return fn(maybe.value); // Don't wrap again!

case 'Nothing':

return nothing();

}

};

Key difference from map: fn returns Maybe<U>, not U. So you don’t wrap the result.

Hint 5: Pattern Matching for Extraction

const match = <T, U>(

patterns: {

just: (value: T) => U;

nothing: () => U;

}

) => (maybe: Maybe<T>): U => {

switch (maybe._tag) {

case 'Just':

return patterns.just(maybe.value);

case 'Nothing':

return patterns.nothing();

}

};

// Usage:

const result = match({

just: (val) => `Found: ${val}`,

nothing: () => 'Not found'

})(someMethod());

This forces you to handle both cases!

Hint 6: Interop with Nullable Values

const fromNullable = <T>(value: T | null | undefined): Maybe<T> => {

return value == null ? nothing() : just(value);

};

const toNullable = <T>(maybe: Maybe<T>): T | null => {

return maybe._tag === 'Just' ? maybe.value : null;

};

Use these at boundaries with existing code.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter/Section |

|---|---|---|

| Functors and Monads from first principles | “Learn You a Haskell for Great Good!” by Miran Lipovaca | Ch. 11-12 (Functors, Applicative Functors, Monads) |

| Maybe/Option monad in depth | “Functional Programming in Scala” by Chiusano & Bjarnason | Ch. 4 (Handling errors without exceptions) |

| TypeScript type system for FP | “Programming TypeScript” by Boris Cherny | Ch. 4 (Functions), Ch. 6 (Advanced Types) |

| Monad laws and category theory | “Category Theory for Programmers” by Bartosz Milewski | Ch. 4 (Kleisli Categories), Ch. 8 (Functoriality) |

| Practical TypeScript FP patterns | “Functional Programming in TypeScript” by Remo Jansen | Ch. 5 (Functors, Applicatives, Monads) |

| Railway-oriented programming | “Domain Modeling Made Functional” by Scott Wlaschin | Ch. 9 (Implementation: Composing a Pipeline) |

| Error handling without exceptions | “Effective TypeScript” by Dan Vanderkam | Items 13-14 (Know the differences between types) |

| Monads explained clearly | “Book of Monads” by Alejandro Serrano Mena | Ch. 2 (Maybe and Either), Ch. 3 (Monad Laws) |

| Real-world FP in TypeScript | “Hands-On Functional Programming with TypeScript” by Remo Jansen | Ch. 7 (Monadic Types) |

| From theory to practice | “Professor Frisby’s Mostly Adequate Guide to FP” by Brian Lonsdorf (free online) | Ch. 8-9 (Tupperware/Containers, Monads) |

Project 4: The “Either” Validation Library

Build an Either monad for error handling and validation without exceptions.

What You’ll Build

A complete Either monad implementation with:

- Left (error) and Right (success) types

- Validation combinators that accumulate errors

- Type-safe error handling without try/catch

- Form validation library as real-world example

Real World Outcome

You’ll build a validation library and see it work in multiple contexts:

1. Command Line Form Validator

$ npm run validate-demo

=== Either Monad Validation Demo ===

[Test 1: Valid User Registration]

Input: {

username: "alice123",

email: "alice@example.com",

age: 25,

password: "SecurePass123!"

}

Result: Right({

username: "alice123",

email: "alice@example.com",

age: 25,

password: "SecurePass123!"

})

✓ Registration successful!

[Test 2: Invalid User Registration]

Input: {

username: "ab",

email: "not-an-email",

age: -5,

password: "weak"

}

Result: Left([

"Username must be at least 3 characters",

"Email format is invalid",

"Age must be between 0 and 120",

"Password must be at least 8 characters",

"Password must contain at least one number",

"Password must contain at least one special character"

])

✗ Validation failed with 6 errors

[Test 3: API Error Handling]

Calling external API...

Success case:

Right({ userId: 123, data: { ... } })

Transformed: Right({ id: 123, processed: true })

Failure case:

Left("Network timeout after 5000ms")

After recovery: Right({ default: "fallback data" })

[Test 4: Chaining Validations]

Step 1 - Parse JSON: Right({ raw: "data" })

Step 2 - Validate schema: Right({ validated: "data" })

Step 3 - Transform: Right({ final: "PROCESSED" })

With error in step 2:

Step 1 - Parse JSON: Right({ raw: "data" })

Step 2 - Validate schema: Left("Missing required field: 'id'")

Step 3 - Transform: Skipped (short-circuit on error)

2. TypeScript Type Safety

Your editor will show:

// WITHOUT Either - exceptions hide in the code

function divideOld(a: number, b: number): number {

if (b === 0) throw new Error("Division by zero");

return a / b;

}

// Caller has NO IDEA this can fail!

const result = divideOld(10, 0); // 💥 Runtime crash

// WITH Either - errors are explicit in types

function divide(a: number, b: number): Either<string, number> {

return b === 0

? left("Division by zero")

: right(a / b);

}

// TypeScript forces you to handle the error!

const result = divide(10, 0);

// result.toFixed(2); // ❌ Compiler error: Either is not a number

// You MUST handle both paths:

result.match({

left: (error) => console.log(`Error: ${error}`),

right: (value) => console.log(`Success: ${value}`)

});

3. Form Validation in Action

// Validation functions return Either

const validateEmail = (email: string): Either<string, string> => {

const emailRegex = /^[^\s@]+@[^\s@]+\.[^\s@]+$/;

return emailRegex.test(email)

? right(email)

: left("Invalid email format");

};

const validateAge = (age: number): Either<string, number> => {

return age >= 0 && age <= 120

? right(age)

: left("Age must be between 0 and 120");

};

// Applicative validation - collects ALL errors

const validateUser = (data: any): Either<string[], User> => {

return applicative([

validateUsername(data.username),

validateEmail(data.email),

validateAge(data.age)

]).map(([username, email, age]) => ({

username,

email,

age

}));

};

// Single call gets ALL validation errors at once!

4. Visual Test Output

$ npm test

Either Monad Implementation

✓ Right wraps a success value

✓ Left wraps an error value

✓ map applies to Right

✓ map ignores Left

✓ flatMap chains Either-returning functions

✓ flatMap short-circuits on Left

✓ bimap transforms both sides

✓ mapLeft transforms only errors

Validation Combinators

✓ applicative collects all errors

✓ applicative succeeds when all succeed

✓ sequence converts [Either<E,A>] to Either<E,[A]>

✓ traverse applies validation to array elements

Real World Scenarios

✓ Form validation with multiple fields

✓ API error handling with retries

✓ JSON parsing with detailed errors

✓ File operations with IO errors

✓ Database queries with error recovery

17 passing (31ms)

5. Web Form Demo (Optional)

If you build the web UI, you’ll see:

- A registration form with fields: username, email, age, password

- As you type, each field shows:

- Green checkmark if valid

- Red X with error message if invalid

- Submit button disabled until ALL fields valid

- On submit with errors: ALL error messages display at once (not one at a time!)

- On submit success: Confirmation screen

The power: You see ALL validation errors simultaneously, not one-by-one.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How can I handle errors as values instead of exceptions, and collect multiple errors at once?”

Sit with this before coding. In most languages, errors are invisible:

function processUser(data: any) {

const user = parseJSON(data); // Could throw

const validated = validate(user); // Could throw

const saved = saveToDb(validated); // Could throw

return saved;

}

Where are the errors? You can’t tell from the signature. Either makes errors explicit:

function processUser(data: any): Either<Error, User> {

// Types tell you this can fail!

}

Even better: Either lets you accumulate errors (validation failures), not just short-circuit on the first one.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

1. Functors (Review from Maybe)

- What does

mapdo on a container? - How does Either’s map differ from Maybe’s?

- Why does map only affect Right, not Left?

- Book Reference: “Learn You a Haskell for Great Good!” Ch. 11

2. Bifunctors

- What does it mean to have TWO type parameters? (

Either<E, A>) - How do you transform BOTH the error and success cases?

- What’s the signature of

bimap? - Book Reference: “Functional Programming in Scala” Ch. 4.4

3. Applicative Functors

- What’s the difference between sequential (flatMap) and parallel (applicative) composition?

- How do you combine multiple Either values?

- Why is

apdifferent fromflatMap? - Book Reference: “Learn You a Haskell for Great Good!” Ch. 12 (Applicative Functors)

4. Error Accumulation vs Short-Circuiting

- When do you want to stop at the first error?

- When do you want to collect ALL errors?

- How does Validation differ from Either?

- Article: “Validation with Applicative Functors” by Typelevel

5. Railway-Oriented Programming (Advanced)

- What’s the “two-track” model of success and failure?

- How do you compose functions that can fail?

- What are “switch” functions vs “two-track” functions?

- Talk: “Railway Oriented Programming” by Scott Wlaschin (YouTube)

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

1. Type Representation

- How do you represent two distinct cases (Left and Right)?

- Should Left and Right be classes or a discriminated union?

- What type parameter should come first: error or value?

2. Bias Towards Right

- Why is Either “right-biased”?

- What does it mean that

maponly transforms Right? - How do you transform Left values? (

mapLeft)

3. FlatMap Semantics

- What happens when you flatMap a Left?

- What happens when you flatMap a Right that returns a Left?

- How is this different from Maybe?

4. Validation vs Either

- Should you use the same type for both?

- How do you implement error accumulation?

- What’s the difference in their Applicative instances?

5. Error Types

- Should errors be strings, objects, or custom types?

- How do you combine different error types?

- Should you use a generic

Eor a fixed error type?

Thinking Exercise

Before coding, trace this by hand:

// Validation scenario:

const validateUser = (data: any): Either<string[], User> => {

// Three validations, each can fail independently

const name = validateName(data.name); // Either<string, string>

const email = validateEmail(data.email); // Either<string, string>

const age = validateAge(data.age); // Either<string, number>

// Question: How do you combine these?

// Option 1: flatMap (short-circuits)

return name.flatMap(n =>

email.flatMap(e =>

age.map(a => ({ name: n, email: e, age: a }))

)

);

// Option 2: Applicative (collects errors)

return applicative([name, email, age])

.map(([n, e, a]) => ({ name: n, email: e, age: a }));

};

Trace these scenarios:

- All validations pass - what’s returned with each option?

- Name fails - what’s returned with each option?

- Name AND email fail - what’s returned with each option? (This is the key difference!)

Draw a diagram showing:

- How flatMap short-circuits

- How applicative collects all errors

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

Conceptual Questions:

- “What’s the difference between Maybe and Either?”

- “Explain why Either is right-biased.”

- “What’s the difference between Either and Validation?”

- “When would you use exceptions instead of Either?”

- “How does Either relate to the Result type in Rust or Go’s error handling?”

Coding Questions:

- “Implement a function to safely parse JSON returning Either<Error, T>”

- “Write a validation that combines Either<E, A>[] into Either<E[], A[]>”

- “Implement bimap for Either”

- “Create a retry mechanism using Either”

- “Write fromTryCatch to convert exception-throwing code to Either”

Design Questions:

- “How do you model validation errors - strings or custom types?”

- “Should Either.Left be a singleton like Maybe.Nothing?”

- “How do you compose Either with async operations?”

- “Compare Either to Promise.catch for error handling”

- “How would you add stack traces to Either errors?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Define the Types

interface Left<E> {

readonly _tag: 'Left';

readonly value: E;

}

interface Right<A> {

readonly _tag: 'Right';

readonly value: A;

}

type Either<E, A> = Left<E> | Right<A>;

Notice: E (error) comes before A (value) by convention.

Hint 2: Constructors

const left = <E, A = never>(value: E): Either<E, A> => ({

_tag: 'Left',

value

});

const right = <A, E = never>(value: A): Either<E, A> => ({

_tag: 'Right',

value

});

Hint 3: Right-Biased Map

const map = <E, A, B>(

fn: (value: A) => B

) => (either: Either<E, A>): Either<E, B> => {

switch (either._tag) {

case 'Right':

return right(fn(either.value));

case 'Left':

return left(either.value); // Unchanged!

}

};

Key: Left passes through untransformed. Only Right gets mapped.

Hint 4: FlatMap (Chain)

const flatMap = <E, A, B>(

fn: (value: A) => Either<E, B>

) => (either: Either<E, A>): Either<E, B> => {

switch (either._tag) {

case 'Right':

return fn(either.value);

case 'Left':

return left(either.value);

}

};

Hint 5: Transform Errors with MapLeft

const mapLeft = <E, A, F>(

fn: (error: E) => F

) => (either: Either<E, A>): Either<F, A> => {

switch (either._tag) {

case 'Left':

return left(fn(either.value));

case 'Right':

return right(either.value); // Unchanged!

}

};

Hint 6: Applicative for Error Accumulation

This is the hard part! Applicative validation:

const applicative = <E, A>(

eithers: Either<E, A>[]

): Either<E[], A[]> => {

const errors: E[] = [];

const values: A[] = [];

for (const either of eithers) {

switch (either._tag) {

case 'Left':

errors.push(either.value);

break;

case 'Right':

values.push(either.value);

break;

}

}

return errors.length > 0

? left(errors)

: right(values);

};

This collects ALL errors before returning!

Hint 7: Convert Exceptions to Either

const tryCatch = <E, A>(

fn: () => A,

onError: (error: unknown) => E

): Either<E, A> => {

try {

return right(fn());

} catch (error) {

return left(onError(error));

}

};

// Usage:

const parsed = tryCatch(

() => JSON.parse(input),

(err) => `Parse error: ${err}`

);

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter/Section |

|---|---|---|

| Either monad fundamentals | “Functional Programming in Scala” by Chiusano & Bjarnason | Ch. 4.3-4.5 (Either, Validation) |

| Error handling without exceptions | “Domain Modeling Made Functional” by Scott Wlaschin | Ch. 6 (Modeling Errors), Ch. 9 (Composing Pipelines) |

| Applicative functors for validation | “Learn You a Haskell for Great Good!” by Miran Lipovaca | Ch. 12 (Applicative Functors) |

| Railway-oriented programming | “Domain Modeling Made Functional” by Scott Wlaschin | Ch. 9 (Error handling patterns) |

| TypeScript error handling patterns | “Programming TypeScript” by Boris Cherny | Ch. 7 (Handling Errors) |

| Monad transformers with Either | “Book of Monads” by Alejandro Serrano Mena | Ch. 4 (Combining Monads), Ch. 7 (Monad Transformers) |

| Practical Either in TypeScript | “Functional Programming in TypeScript” by Remo Jansen | Ch. 6 (Error Handling with Either) |

| Validation patterns | “Hands-On Functional Programming with TypeScript” by Remo Jansen | Ch. 8 (Validation and Error Handling) |

| Bifunctors and bimap | “Category Theory for Programmers” by Bartosz Milewski | Ch. 10 (Natural Transformations) |

| From theory to practice | “Professor Frisby’s Mostly Adequate Guide to FP” by Brian Lonsdorf (free) | Ch. 8 (Tupperware), Ch. 9 (Onions) |

| Error accumulation patterns | “Functional and Reactive Domain Modeling” by Debasish Ghosh | Ch. 6 (Managing Effects) |

| Type-safe error handling | “Effective TypeScript” by Dan Vanderkam | Item 13-14 (Use types to prevent errors) |