Understanding Functional Programming Through Building

Great question! Functional programming (FP) isn’t just a style preference—it’s a fundamentally different way of thinking about computation that solves real problems in specific domains. To truly understand why developers choose FP and where it excels, you need to build things that make those benefits visceral.

Goal

Develop a working, first-principles understanding of functional programming by building real systems that force you to model data immutably, compose transformations, handle errors as data, and reason about concurrency without shared state. By the end, you should be able to explain why FP works, when it wins, and how to apply it across domains.

Core Concept Analysis

Functional programming breaks down into these fundamental building blocks:

| Concept | What It Means | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Pure Functions | Same input → same output, no side effects | Predictable, testable, parallelizable |

| Immutability | Data never changes; you create new versions | No “spooky action at a distance”, safe concurrency |

| First-Class Functions | Functions are values (pass them, return them, store them) | Enables composition and abstraction |

| Higher-Order Functions | Functions that take/return other functions | map, filter, reduce—the bread and butter |

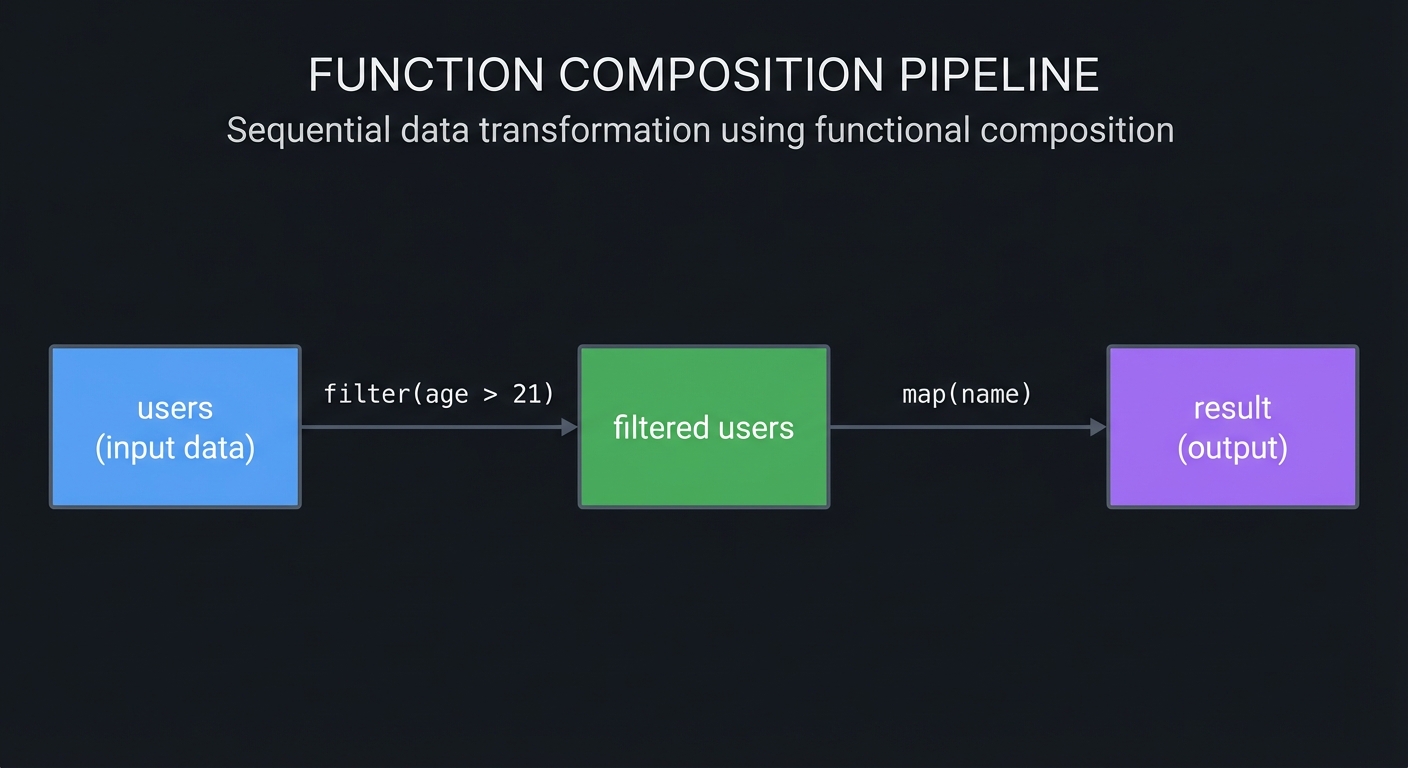

| Function Composition | Building complex operations from simple ones | f(g(x)) chains become pipelines |

| Declarative Style | Describe what, not how | More readable, less error-prone |

| Referential Transparency | Expressions can be replaced with their values | Enables optimization, easier reasoning |

| Algebraic Data Types | Sum types (Either/Maybe) and product types | Model domain precisely, eliminate null errors |

Where FP Shines (and Why)

- Data transformation pipelines: Immutable transforms are easy to reason about and parallelize

- Concurrent/parallel systems: No shared mutable state = no race conditions

- Compilers/interpreters: AST transformations are naturally functional

- Financial systems: Correctness and auditability matter enormously

- UI state management: Redux, Elm Architecture—FP tamed frontend chaos

- Distributed systems: Idempotent, pure operations make retry logic trivial

Concept Summary Table

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize |

|---|---|

| Purity & immutability | Data never mutates; transformations are explicit and testable. |

| Higher-order functions | Functions are values; composition is the default abstraction tool. |

| Referential transparency | Expressions can be replaced by their values without changing behavior. |

| Algebraic data types | Model domains with precise, exhaustive structures. |

| Error-as-data | Use Maybe/Either/Result instead of exceptions. |

| Laziness & recursion | Infinite structures and recursion as primary control flow. |

| Concurrency without locks | Parallelism by avoiding shared mutable state. |

Deep Dive Reading by Concept

This section maps each functional programming concept to specific book chapters for deeper understanding. Read these before or alongside the projects to build strong mental models.

Foundation: Core FP Concepts

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Pure Functions | Domain Modeling Made Functional by Scott Wlaschin — Ch. 8: “Understanding Functions” |

| Pure Functions | Haskell Programming from First Principles by Christopher Allen & Julie Moronuki — Ch. 1: “All You Need is Lambda” |

| Immutability | Fluent Python (2nd Ed.) by Luciano Ramalho — Ch. 6: “Object References, Mutability, and Recycling” |

| Immutability | Programming Rust (2nd Ed.) by Jim Blandy & Jason Orendorff — Ch. 4: “Ownership and Moves” |

| Referential Transparency | Haskell Programming from First Principles by Christopher Allen & Julie Moronuki — Ch. 2: “Hello, Haskell!” |

| Referential Transparency | Learn You a Haskell for Great Good! by Miran Lipovača — Ch. 1: “Introduction” |

Functions as First-Class Citizens

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| First-Class Functions | Fluent Python (2nd Ed.) by Luciano Ramalho — Ch. 7: “Functions as First-Class Objects” |

| First-Class Functions | Learn You a Haskell for Great Good! by Miran Lipovača — Ch. 6: “Higher Order Functions” |

| Higher-Order Functions | Learn You a Haskell for Great Good! by Miran Lipovača — Ch. 6: “Higher Order Functions” |

| Higher-Order Functions | Fluent Python (2nd Ed.) by Luciano Ramalho — Ch. 7: “Functions as First-Class Objects” |

| Function Composition | Domain Modeling Made Functional by Scott Wlaschin — Ch. 6: “Integrity and Consistency in the Domain” |

| Function Composition | Haskell Programming from First Principles by Christopher Allen & Julie Moronuki — Ch. 7: “More Functional Patterns” |

| Closures | Fluent Python (2nd Ed.) by Luciano Ramalho — Ch. 9: “Decorators and Closures” |

| Closures | Haskell Programming from First Principles by Christopher Allen & Julie Moronuki — Ch. 7: “More Functional Patterns” |

Composition and Pipelines

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Function Composition | Learn You a Haskell for Great Good! by Miran Lipovača — Ch. 6: “Higher Order Functions” |

| Pipeline Pattern | Domain Modeling Made Functional by Scott Wlaschin — Ch. 5: “Domain Modeling with Types” |

| Monadic Composition | Programming in Haskell (2nd Ed.) by Graham Hutton — Ch. 12: “Monads and More” |

| Applicative Functors | Learn You a Haskell for Great Good! by Miran Lipovača — Ch. 11: “Functors, Applicative Functors and Monoids” |

Type Systems and Data Modeling

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Algebraic Data Types | Haskell Programming from First Principles by Christopher Allen & Julie Moronuki — Ch. 11: “Algebraic Datatypes” |

| Algebraic Data Types | Domain Modeling Made Functional by Scott Wlaschin — Ch. 5: “Domain Modeling with Types” |

| Sum Types (Either/Maybe) | Learn You a Haskell for Great Good! by Miran Lipovača — Ch. 8: “Making Our Own Types and Typeclasses” |

| Product Types | Haskell Programming from First Principles by Christopher Allen & Julie Moronuki — Ch. 11: “Algebraic Datatypes” |

| Pattern Matching | Learn You a Haskell for Great Good! by Miran Lipovača — Ch. 4: “Syntax in Functions” |

| Type Safety | Domain Modeling Made Functional by Scott Wlaschin — Ch. 4: “Understanding Types” |

Error Handling (Functional Style)

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Error Handling with Maybe/Option | Learn You a Haskell for Great Good! by Miran Lipovača — Ch. 8: “Making Our Own Types and Typeclasses” |

| Error Handling with Either/Result | Programming Rust (2nd Ed.) by Jim Blandy & Jason Orendorff — Ch. 7: “Error Handling” |

| Railway-Oriented Programming | Domain Modeling Made Functional by Scott Wlaschin — Ch. 10: “Implementation: Composing a Pipeline” |

| Monadic Error Handling | Haskell Programming from First Principles by Christopher Allen & Julie Moronuki — Ch. 17: “Applicative” & Ch. 18: “Monad” |

Recursion and Lazy Evaluation

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Recursion | Learn You a Haskell for Great Good! by Miran Lipovača — Ch. 5: “Recursion” |

| Tail Recursion | Haskell Programming from First Principles by Christopher Allen & Julie Moronuki — Ch. 8: “Recursion” |

| Lazy Evaluation | Learn You a Haskell for Great Good! by Miran Lipovača — Ch. 6: “Higher Order Functions” (section on laziness) |

| Lazy Evaluation | Programming in Haskell (2nd Ed.) by Graham Hutton — Ch. 15: “Lazy Evaluation” |

| Streams and Infinite Lists | Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs by Abelson & Sussman — Ch. 3.5: “Streams” |

Declarative Programming and State Management

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Declarative Style | Domain Modeling Made Functional by Scott Wlaschin — Ch. 1: “Introducing Domain-Driven Design” & Ch. 2: “Understanding the Domain” |

| Reactive Programming | Functional and Reactive Domain Modeling by Debasish Ghosh — Ch. 6: “Functional Patterns for Domain Models” |

| Immutable State Updates | Fluent Python (2nd Ed.) by Luciano Ramalho — Ch. 6: “Object References, Mutability, and Recycling” |

| State Machines (Functional) | Domain Modeling Made Functional by Scott Wlaschin — Ch. 8: “Understanding Functions” |

Advanced FP Patterns

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Functors | Learn You a Haskell for Great Good! by Miran Lipovača — Ch. 11: “Functors, Applicative Functors and Monoids” |

| Monads | Haskell Programming from First Principles by Christopher Allen & Julie Moronuki — Ch. 18: “Monad” |

| Monads (Practical) | Programming Rust (2nd Ed.) by Jim Blandy & Jason Orendorff — Ch. 7: “Error Handling” |

| Applicatives | Learn You a Haskell for Great Good! by Miran Lipovača — Ch. 11: “Functors, Applicative Functors and Monoids” |

| Monoid Pattern | Haskell Programming from First Principles by Christopher Allen & Julie Moronuki — Ch. 15: “Monoid, Semigroup” |

Concurrency and Parallelism (Functional Approach)

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Concurrent Programming | Programming Rust (2nd Ed.) by Jim Blandy & Jason Orendorff — Ch. 19: “Concurrency” |

| Parallelism | Parallel and Concurrent Programming in Haskell by Simon Marlow — Ch. 1-3: “Introduction to Parallelism” |

| Actor Model | Programming Rust (2nd Ed.) by Jim Blandy & Jason Orendorff — Ch. 19: “Concurrency” |

| STM (Software Transactional Memory) | Parallel and Concurrent Programming in Haskell by Simon Marlow — Ch. 10: “Software Transactional Memory” |

Language-Specific Deep Dives

| Language/Tool | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Haskell Fundamentals | Learn You a Haskell for Great Good! by Miran Lipovača — Complete book (beginner-friendly) |

| Haskell (Rigorous) | Haskell Programming from First Principles by Christopher Allen & Julie Moronuki — Complete book |

| Scheme/Lisp | Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs by Abelson & Sussman — Ch. 1-3 |

| Python FP | Fluent Python (2nd Ed.) by Luciano Ramalho — Ch. 7-9 (Functions, Closures, Decorators) |

| Rust FP | Programming Rust (2nd Ed.) by Jim Blandy & Jason Orendorff — Ch. 4, 7, 19 (Ownership, Errors, Concurrency) |

| F# Domain Modeling | Domain Modeling Made Functional by Scott Wlaschin — Complete book |

Additional Essential Resources

| Topic | Resource |

|---|---|

| Category Theory for Programmers | Category Theory for Programmers by Bartosz Milewski — Complete book (free online) |

| Parser Combinators | “Monadic Parser Combinators” by Graham Hutton & Erik Meijer — Academic paper |

| The Elm Architecture | “The Elm Architecture” — Official Elm Guide (elm-lang.org) |

| Reactive Programming Introduction | “The introduction to Reactive Programming you’ve been missing” by André Staltz — Blog post |

| Distributed Systems & FP | Designing Data-Intensive Applications by Martin Kleppmann — Ch. 8-9 (on idempotency and consistency) |

Project 1: Build a JSON Query Tool (like jq)

- File: json_query_tool_functional.md

- Main Programming Language: Rust

- Alternative Programming Languages: Haskell, OCaml, TypeScript

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: Level 3: The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate (The Developer)

- Knowledge Area: Parsing, Functional Programming, CLI Tools

- Software or Tool: jq

- Main Book: Domain Modeling Made Functional by Scott Wlaschin

What you’ll build: A command-line tool that queries and transforms JSON using a pipeline syntax like cat data.json | jql '.users | filter(.age > 21) | map(.name)'

Why it teaches functional programming: This project forces you to understand why FP dominates data transformation. You’ll build a pipeline where each operation is a pure function that transforms data immutably. You’ll see firsthand why composition makes complex queries simple, and why immutability makes debugging trivial.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Designing a composable pipeline architecture (forces understanding of function composition)

- Implementing

map,filter,reduce,flatMapoperations (the FP workhorses) - Handling errors without exceptions (introduces

Maybe/Eitherpatterns) - Parsing a mini-language for query expressions (recursive descent, pattern matching)

- Making operations chainable and lazy (understand why laziness enables efficiency)

Key Concepts:

- Function Composition: Learn You a Haskell for Great Good! Ch. 6 “Higher Order Functions” - Miran Lipovača

- Map/Filter/Reduce: Fluent Python 2nd Ed. Ch. 7 “Functions as First-Class Objects” - Luciano Ramalho

- Pipeline Pattern: Domain Modeling Made Functional Ch. 5 “Domain Modeling with Types” - Scott Wlaschin

- Error Handling without Exceptions: Effective Rust Ch. 4 “Errors” - David Drysdale

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 1-2 weeks Prerequisites: Comfortable with one programming language, basic parsing concepts

Real world outcome:

You’ll have a working CLI tool that processes JSON files. Run echo '{"users":[{"name":"Alice","age":30},{"name":"Bob","age":19}]}' | jql '.users | filter(.age >= 21) | map(.name)' and see ["Alice"] printed to stdout. You can use it on real JSON APIs and config files.

Learning milestones:

- After implementing basic traversal: You understand how pure functions transform data without mutation

- After building the pipeline: You understand why composition scales—adding new operations is trivial

- After handling errors with

Result/Either: You understand why FP avoids exceptions—errors become data you transform - Final: You’ve internalized why FP dominates data processing—it’s made for this

Real World Outcome

You’ll have a working command-line tool that feels like the industry-standard jq, but you’ll understand every line of its implementation. Here’s what using your tool looks like:

Basic querying:

$ echo '{"name":"Alice","age":30,"city":"NYC"}' | ./jql '.name'

"Alice"

$ echo '{"name":"Alice","age":30,"city":"NYC"}' | ./jql '.age'

30

Array operations:

$ cat users.json

{

"users": [

{"name": "Alice", "age": 30, "active": true},

{"name": "Bob", "age": 19, "active": false},

{"name": "Charlie", "age": 25, "active": true},

{"name": "Diana", "age": 17, "active": true}

]

}

$ cat users.json | ./jql '.users | map(.name)'

["Alice", "Bob", "Charlie", "Diana"]

$ cat users.json | ./jql '.users | filter(.age >= 21)'

[

{"name": "Alice", "age": 30, "active": true},

{"name": "Charlie", "age": 25, "active": true}

]

$ cat users.json | ./jql '.users | filter(.age >= 21) | map(.name)'

["Alice", "Charlie"]

Chained transformations (the power of composition):

$ cat users.json | ./jql '.users | filter(.active) | filter(.age >= 21) | map(.name) | sort'

["Alice", "Charlie"]

Error handling:

$ echo '{"broken json}' | ./jql '.name'

Error: Parse error at line 1, column 10: Expected ':', found '}'

$ cat users.json | ./jql '.nonexistent'

Error: Path '.nonexistent' not found in object

$ cat users.json | ./jql '.users | filter(.age > "text")'

Error: Type mismatch: cannot compare number with string at .users[0].age

Real-world use case - querying an API response:

$ curl -s https://api.github.com/repos/rust-lang/rust/issues?per_page=3 | ./jql '. | map(.title)'

[

"Tracking Issue for RFC 3543: patchable-function-entry",

"Implement Default for RangeFrom and RangeToInclusive",

"Update cargo"

]

$ curl -s https://api.github.com/repos/rust-lang/rust/issues?per_page=5 | \

./jql '. | filter(.state == "open") | map({title: .title, user: .user.login})'

[

{"title": "Tracking Issue for RFC 3543...", "user": "joshtriplett"},

{"title": "Implement Default for RangeFrom...", "user": "scottmcm"},

{"title": "Update cargo", "user": "weihanglo"}

]

What you can observe happening inside:

- Each operation (

map,filter,sort) is a pure function - Data flows through the pipeline immutably—original JSON is never modified

- Errors propagate cleanly through the

Resulttype—no exceptions thrown - Lazy evaluation (if you implement it) means the tool only processes what’s needed

You’ll run your tool on real JSON files—config files, API responses, log files—and see it transform data exactly like jq. The difference? You’ll understand why it works: function composition, immutable data structures, and algebraic data types for error handling.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“Why do functional programmers say ‘composition is everything’? What does it mean to build complex behavior by combining simple functions?”

Before you write any code, sit with this question. In imperative programming, you build complexity by accumulating state through loops and mutations. In functional programming, you build complexity by composing functions—feeding the output of one into the input of another.

The JSON query tool makes this concrete: filter is a function, map is a function, sort is a function. When you write .users | filter(.age > 21) | map(.name), you’re not writing a loop that mutates an array. You’re composing three pure functions into a pipeline:

users → filter(age > 21) → map(name) → result

Each function is simple. The power comes from combining them. This project will teach you why composition scales in ways that imperative code doesn’t.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

1. Pure Functions

Questions to answer:

- What does it mean for a function to have “no side effects”?

- If

filter(arr, predicate)is pure, what does it return? Does it modifyarr? - Why can you test a pure function by just checking its output for a given input?

- What’s the relationship between purity and parallelization?

Book Reference: Domain Modeling Made Functional by Scott Wlaschin — Ch. 4: “Working with Functional Building Blocks” (section on pure functions)

Self-test: Write a pure version of a function that filters an array. Then write an impure version that modifies the array in-place. Can you explain why one is easier to test?

2. Immutability

Questions to answer:

- What does it mean to say data is “immutable”?

- If you can’t modify data, how do you “change” it? (Hint: you don’t change it—you create new data)

- Why does immutability make debugging easier?

- What’s the performance cost? How do languages like Clojure mitigate this with persistent data structures?

Book Reference: Fluent Python 2nd Ed. by Luciano Ramalho — Ch. 6: “Object References, Mutability, and Recycling”

Self-test: Explain why let arr2 = arr1.push(x) in JavaScript mutates arr1, but let arr2 = [...arr1, x] doesn’t. Which is more functional?

3. Higher-Order Functions (map, filter, reduce)

Questions to answer:

- What does it mean for a function to “take a function as an argument”?

- How does

mapdiffer from aforloop? - Why is

filterdeclarative while a loop with conditionals is imperative? - Can you implement

reduceyourself? What does it do?

Book Reference: Learn You a Haskell for Great Good! by Miran Lipovača — Ch. 6: “Higher Order Functions”

Self-test: Implement map, filter, and reduce from scratch without using any built-in versions. Explain what each does in one sentence.

4. Function Composition

Questions to answer:

- What does

f(g(x))mean? How do you read it? - If

freturns a number andgtakes a number, can you compose them? - Why is composition written right-to-left in math (

f ∘ g) but often left-to-right in code (pipelines)? - How does composition relate to the Unix philosophy of “small tools that do one thing”?

Book Reference: Domain Modeling Made Functional by Scott Wlaschin — Ch. 6: “Composing Pipelines”

Self-test: Write three functions: one that parses JSON, one that extracts a field, one that uppercases a string. Compose them into a pipeline.

5. Algebraic Data Types (Option/Maybe, Result/Either)

Questions to answer:

- How do you represent “this value might not exist” without using

null? - What’s the difference between

Option<T>andResult<T, E>? - Why is pattern matching important for working with these types?

- How does

Resultmake errors explicit in the type signature?

Book Reference: Programming Rust 2nd Ed. by Blandy & Orendorff — Ch. 7: “Error Handling” (sections on Option and Result)

Self-test: Write a function that divides two numbers and returns Result<f64, String>. Handle the divide-by-zero case. Why is this better than returning -1 or throwing an exception?

6. Parsing and ASTs (Abstract Syntax Trees)

Questions to answer:

- What’s the difference between parsing (string → data structure) and evaluation (data structure → result)?

- What is an AST? Why is it a tree?

- For the query

.users | filter(.age > 21), what would the AST look like? - How do you represent operations like “get field”, “pipe”, “compare” as data?

Book Reference: Language Implementation Patterns by Terence Parr — Ch. 2: “Basic Parsing Patterns”

Self-test: Draw the AST for .users | filter(.age > 21) | map(.name). Label each node with its operation type.

7. Recursion (for JSON traversal)

Questions to answer:

- Why is recursion natural for tree-like data structures?

- How do you traverse a JSON object that might contain nested objects or arrays?

- What’s the base case for recursion on JSON?

- How does recursion relate to immutability?

Book Reference: The Recursive Book of Recursion by Al Sweigart — Ch. 1-2: “What Is Recursion?” and “Recursion vs. Iteration”

Self-test: Write a recursive function that counts how many numbers appear anywhere in a nested JSON structure (including inside arrays and objects).

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

1. Representing the Query Language

- What data structure represents a query like

.users | filter(.age > 21)? - How do you distinguish between different operations (map, filter, sort, get field)?

- Should you use an enum/sum type? Why or why not?

- How do you represent the pipe operator in your AST?

Hint: Think of each operation as a variant of an enum: Operation::Map(fn), Operation::Filter(predicate), Operation::GetField(name), etc.

2. Parsing the Query String

- How do you tokenize

.users | filter(.age > 21)? - What comes first: tokenization or parsing?

- How do you handle nested expressions like

filter(.user.address.city == "NYC")? - What should happen if the query is malformed?

Hint: Use a recursive descent parser. Each grammar rule becomes a function.

3. Making Operations Pure

- If

filtertakes a JSON array and returns a filtered array, does it modify the input? - How do you ensure

mapdoesn’t mutate the original data? - Should operations return

Result<Json, Error>or justJson? - When should you propagate errors vs. handle them?

Hint: Every operation should return a new data structure. Clone, don’t mutate.

4. Composing the Pipeline

- How do you execute

.users | filter(.age > 21) | map(.name)? - Is it

map(filter(getField(json, "users"), predicate), mapper)? - Can you make it more ergonomic with method chaining?

- How does the pipe operator work mechanically?

Hint: Each pipe feeds the output of the left side into the input of the right side. It’s just function application.

5. Error Handling Without Exceptions

- What can go wrong during query execution? (Parse errors, type mismatches, missing fields)

- How do you represent errors in the type system?

- Should errors stop execution immediately, or can you collect multiple errors?

- How do you make error messages useful? (Show where in the query the error occurred)

Hint: Use Result<T, E> for operations that can fail. Use the ? operator (in Rust) or monadic bind to chain operations.

6. Handling Different JSON Types

- JSON has objects, arrays, strings, numbers, booleans, null. How do you represent this?

- What should

mapdo when applied to a non-array? - What should

.fielddo when applied to a non-object? - Should type mismatches be errors or silently fail?

Hint: Use an enum to represent JSON values. Pattern match to extract the right type.

Thinking Exercise

Trace a Query By Hand

Before coding, trace this query execution on paper:

JSON input:

{

"users": [

{"name": "Alice", "age": 30},

{"name": "Bob", "age": 19},

{"name": "Charlie", "age": 25}

]

}

Query: .users | filter(.age >= 21) | map(.name)

Step-by-step trace:

- Parse phase: What does the AST look like?

Pipeline( GetField("users"), Filter(BinaryOp(GetField("age"), GreaterEq, Literal(21))), Map(GetField("name")) ) - Execution phase:

- Apply

GetField("users")to the root object → returns[{"name": "Alice", "age": 30}, ...] - Apply

Filter(...)to the array → returns[{"name": "Alice", "age": 30}, {"name": "Charlie", "age": 25}] - Apply

Map(GetField("name"))to the filtered array → returns["Alice", "Charlie"]

- Apply

- Questions while tracing:

- At what point is each function called?

- Does any step modify the original JSON?

- What’s the type of each intermediate result?

- Where could errors occur? What should the error message be?

Design Exercise: Extend the Language

Imagine you want to add a reduce operation: .users | reduce(.age, 0, add) (sum all ages).

- How would you represent this in the AST?

- What arguments does

reduceneed? (initial value, reducer function) - How would you parse

reduce(.age, 0, add)? - How would you execute it on an array?

This exercise forces you to think about extensibility—a key FP principle.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these after completing the project:

Fundamentals

- “What’s the difference between

mapand aforloop?”- Expected answer:

mapis declarative (describes what to do), returns a new array, and is a pure function. Aforloop is imperative (describes how to do it) and typically mutates state.

- Expected answer:

- “Why are pure functions easier to test?”

- Expected answer: No setup/teardown needed, no mocking dependencies, output depends only on input. Just assert

fn(input) == expected_output.

- Expected answer: No setup/teardown needed, no mocking dependencies, output depends only on input. Just assert

- “How does immutability help with debugging?”

- Expected answer: No “action at a distance”—data can’t change unexpectedly. You can log values and trust they won’t be modified later. Makes time-travel debugging possible.

- “What is function composition? Give an example.”

- Expected answer: Combining functions so the output of one becomes the input of another. Example:

compose(uppercase, trim, parseJSON)(" hello ")→"HELLO".

- Expected answer: Combining functions so the output of one becomes the input of another. Example:

Advanced

- “How would you make your JSON query tool lazy to handle large files?”

- Expected answer: Use iterators/streams instead of materializing arrays. Only compute values when needed. Example:

filteryields items one at a time instead of creating a new array.

- Expected answer: Use iterators/streams instead of materializing arrays. Only compute values when needed. Example:

- “What’s the difference between

OptionandResultin error handling?”- Expected answer:

Option<T>represents presence/absence (Some/None).Result<T, E>represents success/failure with an error value. UseResultwhen you need to know why something failed.

- Expected answer:

- “How does pattern matching improve code safety compared to if/else?”

- Expected answer: Compiler ensures you handle all cases. Can’t forget to check for

Noneor an error variant. Makes illegal states unrepresentable.

- Expected answer: Compiler ensures you handle all cases. Can’t forget to check for

- “Why is functional programming popular for data transformation pipelines?”

- Expected answer: Immutable data is safe to parallelize. Pure functions are easy to reason about and test. Composition scales—complex pipelines built from simple operations.

Design

- “How would you add support for user-defined functions in your query language?”

- Expected answer: Need a way to define named functions, store them in an environment/context, and reference them by name. Closures for capturing variables.

- “If your pipeline is

map(filter(map(data, f1), pred), f2), how can you optimize it?”- Expected answer: Fusion—combine operations to avoid intermediate allocations. Or use lazy evaluation so work is only done once. Or parallelize independent operations.

Hints in Layers

Use these only when stuck. Try to solve the problem first!

Hint 1: Start with JSON parsing

Don’t write the query parser first. Use an existing JSON library (serde_json in Rust, json in Python, JSON.parse in JavaScript). Your focus is on the transformation logic, not JSON parsing.

// Rust example

use serde_json::Value;

let json_str = r#"{"name": "Alice", "age": 30}"#;

let data: Value = serde_json::from_str(json_str)?;

This lets you focus on the functional programming concepts.

Hint 2: Represent operations as an enum

Define your operations as a sum type:

enum Operation {

GetField(String),

Map(Box<Operation>),

Filter(Box<Predicate>),

Sort,

}

enum Predicate {

GreaterThan(String, f64), // field name, value

Equals(String, String),

// ...

}

Now a query is just a list of operations: vec![GetField("users"), Filter(...), Map(...)]

Hint 3: Execution is just a fold

Executing a pipeline is folding over operations:

fn execute(json: Value, operations: Vec<Operation>) -> Result<Value, Error> {

operations.into_iter().try_fold(json, |acc, op| {

apply_operation(acc, op)

})

}

fn apply_operation(json: Value, op: Operation) -> Result<Value, Error> {

match op {

Operation::GetField(field) => get_field(json, field),

Operation::Filter(pred) => filter(json, pred),

Operation::Map(inner) => map(json, inner),

// ...

}

}

Each operation is a pure function: Value -> Result<Value, Error>.

Hint 4: Implement map as a recursive function

map needs to apply a transformation to each element of an array:

fn map(json: Value, op: Operation) -> Result<Value, Error> {

match json {

Value::Array(arr) => {

let mapped: Result<Vec<Value>, Error> = arr

.into_iter()

.map(|item| apply_operation(item, op.clone()))

.collect();

Ok(Value::Array(mapped?))

}

_ => Err(Error::TypeMismatch("Expected array for map"))

}

}

Notice: arr is consumed, not mutated. We build a new array.

Hint 5: Parse queries with a simple tokenizer

Start simple. Split on | for pipes, then parse each segment:

fn parse_query(query: &str) -> Vec<Operation> {

query.split('|')

.map(|segment| parse_operation(segment.trim()))

.collect()

}

fn parse_operation(segment: &str) -> Operation {

if segment.starts_with('.') {

Operation::GetField(segment[1..].to_string())

} else if segment.starts_with("filter") {

// Parse filter expression

parse_filter(segment)

} else if segment.starts_with("map") {

parse_map(segment)

}

// ...

}

Later, you can replace this with a real parser (recursive descent, parser combinators, etc.).

Hint 6: Make errors descriptive

Don’t just return Err("something went wrong"). Include context:

#[derive(Debug)]

enum Error {

ParseError { line: usize, col: usize, msg: String },

TypeError { expected: String, got: String, path: String },

FieldNotFound { field: String, path: String },

}

impl std::fmt::Display for Error {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut std::fmt::Formatter) -> std::fmt::Result {

match self {

Error::FieldNotFound { field, path } => {

write!(f, "Field '{}' not found at path '{}'", field, path)

}

// ...

}

}

}

Good error messages make your tool usable.

Hint 7: Test with small examples first

Before handling complex queries, test each operation in isolation:

#[test]

fn test_map() {

let json = json!(["Alice", "Bob", "Charlie"]);

let result = map(json, Operation::Uppercase).unwrap();

assert_eq!(result, json!(["ALICE", "BOB", "CHARLIE"]));

}

#[test]

fn test_filter() {

let json = json!([1, 2, 3, 4, 5]);

let result = filter(json, Predicate::GreaterThan(3)).unwrap();

assert_eq!(result, json!([4, 5]));

}

Build confidence incrementally.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Pure functions and immutability | Domain Modeling Made Functional by Scott Wlaschin | Ch. 4: “Working with Functional Building Blocks” |

| Higher-order functions (map, filter, reduce) | Learn You a Haskell for Great Good! by Miran Lipovača | Ch. 6: “Higher Order Functions” |

| Function composition and pipelines | Domain Modeling Made Functional by Scott Wlaschin | Ch. 6: “Composing Pipelines” |

| Algebraic data types (Option, Result) | Programming Rust 2nd Ed. by Jim Blandy & Jason Orendorff | Ch. 7: “Error Handling” |

| Understanding map/filter in Python | Fluent Python 2nd Ed. by Luciano Ramalho | Ch. 7: “Functions as First-Class Objects” |

| Immutable data structures | Fluent Python 2nd Ed. by Luciano Ramalho | Ch. 6: “Object References, Mutability, and Recycling” |

| Parsing fundamentals | Language Implementation Patterns by Terence Parr | Ch. 2: “Basic Parsing Patterns” |

| Recursion for tree traversal | The Recursive Book of Recursion by Al Sweigart | Ch. 1-2: “What Is Recursion?” and “Recursion vs. Iteration” |

| Functional error handling in Rust | Effective Rust by David Drysdale | Ch. 4: “Errors” (sections on Result and ? operator) |

| Pattern matching | Programming Rust 2nd Ed. by Jim Blandy & Jason Orendorff | Ch. 10: “Enums and Patterns” |

| Building command-line tools in Rust | Command-Line Rust by Ken Youens-Clark | Ch. 1-3: Basics of CLI parsing and I/O |

| Why functional programming for data | Domain Modeling Made Functional by Scott Wlaschin | Ch. 1-2: “Introduction to Domain Modeling” |

Recommended Reading Order

- Week 1 - Foundations:

- Learn You a Haskell Ch. 6 (higher-order functions) — understand map, filter, fold

- Domain Modeling Made Functional Ch. 4 (pure functions) — internalize purity

- Fluent Python Ch. 6 (immutability) — see why immutability matters

- Week 2 - Implementation:

- Programming Rust Ch. 7 (error handling) — master

ResultandOption - Language Implementation Patterns Ch. 2 (parsing) — build the query parser

- Domain Modeling Made Functional Ch. 6 (pipelines) — understand composition

- Programming Rust Ch. 7 (error handling) — master

- Week 3 - Refinement:

- Command-Line Rust Ch. 1-3 (CLI tools) — polish the UX

- Effective Rust Ch. 4 (errors) — improve error messages

- The Recursive Book of Recursion Ch. 1-2 — optimize JSON traversal

Project 2: Implement a Scheme/Lisp Interpreter

- File: scheme_lisp_interpreter_functional.md

- Main Programming Language: Haskell

- Alternative Programming Languages: OCaml, Rust, Python

- Coolness Level: Level 5: Pure Magic (Super Cool)

- Business Potential: Level 1: The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced (The Engineer)

- Knowledge Area: Interpreters, Compilers, Functional Programming

- Software or Tool: Scheme, Lisp

- Main Book: Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs by Abelson & Sussman

What you’ll build: A working interpreter for a subset of Scheme that can evaluate expressions like (define (factorial n) (if (<= n 1) 1 (* n (factorial (- n 1))))) and then (factorial 10)

Why it teaches functional programming: Lisp is functional programming distilled to its essence. Building an interpreter forces you to understand closures, lexical scoping, first-class functions, and recursion at a mechanical level. You’ll see why “code as data” (homoiconicity) enables powerful abstractions.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Implementing lexical closures (the hardest part—forces deep understanding of environments)

- Building an environment model for variable binding (understand scope chains)

- Implementing

lambdaand function application (first-class functions become concrete) - Adding

let,define, and recursion support (see how binding works) - Implementing tail-call optimization (understand why FP needs this)

Resources for key challenges:

- Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs Ch. 3-4 by Abelson & Sussman - The definitive resource for understanding interpreters and environments

Key Concepts:

- Closures and Lexical Scope: Haskell Programming from First Principles Ch. 7 “More Functional Patterns” - Christopher Allen & Julie Moronuki

- First-Class Functions: The Little Schemer entire book - Friedman & Felleisen

- Recursion and Evaluation: Learn You a Haskell for Great Good! Ch. 5 “Recursion” - Miran Lipovača

- Environment Model: Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs Ch. 3.2 - Abelson & Sussman

Difficulty: Intermediate-Advanced Time estimate: 2-3 weeks Prerequisites: Understanding of recursion, basic data structures (trees)

Real world outcome:

You’ll have a working REPL where you can type Scheme expressions and see results. Define functions, create closures, and watch recursion unfold. Run (map (lambda (x) (* x x)) '(1 2 3 4 5)) and see (1 4 9 16 25).

Learning milestones:

- After implementing evaluation: You understand that programs are just data structures being transformed

- After implementing closures: You deeply understand how functions “capture” their environment—this unlocks FP

- After implementing

mapandfilterin your Lisp: You see these aren’t magic—they’re just functions that take functions - Final: You understand why Lisp influenced every functional language—its simplicity reveals FP’s core

Project 3: Build a Reactive Spreadsheet Engine

- File: reactive_spreadsheet_engine_functional.md

- Main Programming Language: TypeScript

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Haskell, Elm

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: Level 4: The “Open Core” Infrastructure

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate (The Developer)

- Knowledge Area: Reactive Programming, Dependency Graphs, Functional Programming

- Software or Tool: Excel, React

- Main Book: Domain Modeling Made Functional by Scott Wlaschin

What you’ll build: A spreadsheet where cells can contain formulas referencing other cells (A1 = 10, B1 = A1 * 2, C1 = B1 + A1), and changes propagate automatically with dependency tracking.

Why it teaches functional programming: Spreadsheets are secretly the most successful functional programming environment ever created. Each cell is a pure function of its dependencies. This project teaches you declarative programming—you declare relationships, not update procedures—and reactive dataflow, which is how modern UI frameworks (React, Vue) actually work under the hood.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Building a dependency graph between cells (understand dataflow)

- Implementing topological sort for update ordering (why order matters in a “declarative” world)

- Detecting circular dependencies (understand why pure functions can’t have cycles)

- Making updates efficient with memoization (see how immutability enables caching)

- Handling the formula parsing and evaluation (expression trees)

Key Concepts:

- Declarative vs Imperative: Domain Modeling Made Functional Ch. 1-2 - Scott Wlaschin

- Dependency Graphs: Grokking Algorithms Ch. 6 “Breadth-First Search” - Aditya Bhargava

- Memoization: Fluent Python 2nd Ed. Ch. 9 “Decorators and Closures” - Luciano Ramalho

- Reactive Programming: “The introduction to Reactive Programming you’ve been missing” - André Staltz (blog post)

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 1-2 weeks Prerequisites: Basic graph concepts, expression parsing

Real world outcome:

You’ll have a terminal-based (or simple web) spreadsheet. Type A1=10, B1=A1*2, C1=A1+B1 and see values computed. Change A1=20 and watch B1 become 40 and C1 become 60 automatically. This is the FP model that powers Excel, React, and databases.

Learning milestones:

- After building dependency tracking: You understand why FP emphasizes explicit dependencies—hidden state creates bugs

- After implementing efficient updates: You understand how immutability enables smart caching (if inputs didn’t change, output didn’t change)

- After handling circular dependency errors: You understand why purity matters—impure functions hide impossible states

- Final: You’ve internalized declarative programming—describe relationships, let the system figure out execution

Project 4: Create a Parser Combinator Library

- File: FUNCTIONAL_PROGRAMMING_LEARNING_PROJECTS.md

- Programming Language: C

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 4. The “Open Core” Infrastructure

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Functional Programming / Parsers

- Software or Tool: Monads

- Main Book: “Language Implementation Patterns” by Terence Parr

What you’ll build: A library where you combine small parsers into complex ones: let email = sequence([word, char('@'), word, char('.'), word]) that can parse structured text.

Why it teaches functional programming: Parser combinators are the canonical example of FP’s power. They demonstrate why higher-order functions and composition scale beautifully. You’ll understand monads not as abstract math, but as “things that chain operations and handle context.”

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Designing parsers as functions (forces understanding of functions as values)

- Implementing

sequence,choice,many,optionalcombinators (higher-order functions) - Handling parse state threading (leads naturally to monads/applicatives)

- Making error messages useful (see how FP handles context/state)

- Building complex parsers from primitives (experience composition at scale)

Resources for key challenges:

- “Monadic Parser Combinators” by Graham Hutton & Erik Meijer - The academic paper that explains the pattern clearly

Key Concepts:

- Higher-Order Functions: Learn You a Haskell for Great Good! Ch. 6 - Miran Lipovača

- Monads (Practical): Programming Rust 2nd Ed. Ch. 7 “Error Handling” - Blandy & Orendorff

- Parser Design: Language Implementation Patterns Ch. 2 “Basic Parsing Patterns” - Terence Parr

- Function Composition: Domain Modeling Made Functional Ch. 6 “Composing Pipelines” - Scott Wlaschin

Difficulty: Advanced Time estimate: 2 weeks Prerequisites: Solid understanding of functions, comfortable with recursion

Real world outcome:

You’ll have a library that can parse real formats. Write a JSON parser in ~50 lines of composed functions. Parse log files, config formats, or DSLs. See how let json = choice([jsonNull, jsonBool, jsonNumber, jsonString, jsonArray, jsonObject]) elegantly expresses grammar.

Learning milestones:

- After basic combinators work: You understand that complex behavior emerges from combining simple functions

- After implementing

sequencewith state threading: You understand why monads exist—they manage context invisibly - After building a JSON parser: You experience how FP scales—your parser is the grammar, readable and maintainable

- Final: You’ve internalized the power of composition—FP’s core insight that complexity is managed through combination, not mutation

Project 5: Implement Redux from Scratch (for Web or CLI)

- File: FUNCTIONAL_PROGRAMMING_LEARNING_PROJECTS.md

- Programming Language: JavaScript/TypeScript

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: State Management / Functional Programming

- Software or Tool: Redux pattern

- Main Book: “Domain Modeling Made Functional” by Scott Wlaschin

What you’ll build: A state management system where: state is immutable, changes happen through pure “reducer” functions, and UI automatically updates when state changes.

Why it teaches functional programming: Redux brought FP to millions of JavaScript developers because it solved a real problem—managing complex UI state without going insane. Building it yourself reveals why immutability, pure functions, and unidirectional data flow make applications predictable.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Implementing immutable state updates (understand why copying enables time-travel debugging)

- Designing the reducer pattern (pure functions that transform state)

- Building a subscription system for reactivity (observers without mutation)

- Implementing middleware for side effects (how FP isolates impurity)

- Adding time-travel debugging (see why immutability makes the impossible trivial)

Key Concepts:

- Immutable State: Fluent Python 2nd Ed. Ch. 6 “Object References, Mutability, and Recycling” - Luciano Ramalho

- Pure Functions: Effective Rust Ch. 1 “Types” (section on data ownership) - David Drysdale

- State Machines: Domain Modeling Made Functional Ch. 8 “Understanding Functions” - Scott Wlaschin

- The Elm Architecture: “The Elm Architecture” - Official Elm Guide (elm-lang.org)

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 1 week Prerequisites: Basic JavaScript or TypeScript, understanding of callbacks

Real world outcome: Build a todo app (or CLI task manager) powered by your Redux. Add time-travel: press a key to undo/redo any state change. See every action logged. Realize that debugging is trivial because every state transition is recorded and reproducible.

Learning milestones:

- After implementing reducers: You understand why pure functions make state changes predictable—no hidden mutations

- After building time-travel: You viscerally understand why immutability matters—you can’t time-travel with mutation

- After adding middleware: You understand how FP isolates side effects—keep the core pure, push impurity to edges

- Final: You understand why FP conquered frontend state—it’s not academic, it solves real pain

Project Comparison Table

| Project | Difficulty | Time | Depth of Understanding | Fun Factor | Best For Understanding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JSON Query Tool | Intermediate | 1-2 weeks | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ | Composition, pipelines, immutable transforms |

| Scheme Interpreter | Intermediate-Advanced | 2-3 weeks | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ | Closures, first-class functions, recursion |

| Reactive Spreadsheet | Intermediate | 1-2 weeks | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ | Declarative programming, dataflow |

| Parser Combinators | Advanced | 2 weeks | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐ | Higher-order functions, monads, composition |

| Redux from Scratch | Intermediate | 1 week | ⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ | Immutability, pure reducers, real-world FP |

Recommendation

Start with: JSON Query Tool (Project 1)

Here’s why:

- Immediate practical value: You’ll use it on real files and APIs

- Forces core FP patterns: You can’t build pipelines without understanding composition

- Visible results fast:

cat file.json | jql '.data | map(.name)'working feels great - Natural progression: The challenges escalate—basic ops → composition → error handling → laziness

- Language agnostic: Build it in Rust (best FP ergonomics), TypeScript, Python, or Haskell itself

After that: Build the Scheme Interpreter if you want deep understanding of how FP actually works at the implementation level. Or build the Reactive Spreadsheet if you want to understand why FP conquered modern UI development.

Final Capstone Project: Build a Distributed Task Processing System

What you’ll build: A system like a mini-Celery or mini-Spark: clients submit tasks (pure functions + data), workers execute them, results flow back. Tasks can be composed into pipelines. Failed tasks retry automatically.

Why it’s the ultimate FP test: This project requires every FP concept working together:

- Pure functions: Tasks must be pure so workers can retry without side effects

- Immutability: Task state must be immutable for safe distribution

- Composition: Complex workflows built from simple task functions

- Isolation of effects: Network, storage, failures—all pushed to the edges

- Declarative pipelines: Define what to compute, not how to distribute it

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Serializing functions and closures for network transport (understand what “first-class” really means)

- Ensuring idempotency for retry safety (pure functions shine here)

- Building a DAG scheduler for task dependencies (declarative workflow execution)

- Handling partial failures gracefully (FP error handling at scale)

- Implementing back-pressure and flow control (lazy evaluation in distributed form)

Key Concepts:

- Distributed Systems Basics: Designing Data-Intensive Applications Ch. 8-9 - Martin Kleppmann

- Idempotency: Release It! 2nd Ed. Ch. 5 “Stability Patterns” - Michael Nygard

- Actor Model: Programming Rust 2nd Ed. Ch. 19 “Concurrency” - Blandy & Orendorff

- Workflow Orchestration: Building Microservices 2nd Ed. Ch. 6 “Workflow” - Sam Newman

Difficulty: Advanced Time estimate: 1 month+ Prerequisites: Completed at least 2 projects above, understanding of networking basics

Real world outcome:

Submit a job: client.submit(pipeline([fetch_url, parse_html, extract_links, filter_valid])) and watch workers process it. See tasks distributed, retried on failure, results collected. Build a web scraper, data pipeline, or batch processor on top of your system.

Learning milestones:

- After basic task execution: You understand why purity enables distribution—no shared state means any worker can run any task

- After implementing retries: You understand why idempotency matters—pure functions make retry trivial

- After building pipelines: You understand why FP scales—composition works at any level, from functions to distributed systems

- Final: You’ve internalized the deepest insight—FP isn’t about syntax or avoiding loops, it’s about building systems where correctness is structural, not accidental

The “Why” Summary

By the end of these projects, you’ll understand FP not as a set of rules (“avoid mutation!”, “use map not for loops!”) but as a design philosophy:

| FP Principle | Why It Actually Matters |

|---|---|

| Pure functions | Testing is trivial, parallelism is free, debugging shows exact cause |

| Immutability | Time-travel debugging, safe concurrency, caching is automatic |

| Composition | Complexity managed through combination, not accumulation |

| Declarative style | Express intent, not mechanism—code becomes specification |

| Explicit effects | Side effects are visible, controlled, and testable |

Functional programming shines wherever correctness matters more than cleverness—compilers, finance, distributed systems, data pipelines, and increasingly, everywhere else.