Deeply Understanding Filesystems Through Building

Filesystems are one of the most elegant abstractions in computing—they transform raw disk blocks into the familiar hierarchy of files and directories we use daily. To truly understand them, you need to grapple with their core challenges: block management, metadata organization, journaling for crash consistency, and the VFS abstraction layer.

Core Concept Analysis

Understanding filesystems breaks down into these fundamental building blocks:

| Concept | What It Covers |

|---|---|

| On-disk layout | Superblock, inode tables, data blocks, block groups |

| Metadata management | Inodes, directory entries, permissions, timestamps |

| Block allocation | Bitmap vs extent-based, fragmentation, free space tracking |

| Journaling | Write-ahead logging, crash recovery, consistency guarantees |

| VFS layer | How Linux abstracts different filesystems behind one interface |

| Caching | Page cache, buffer cache, write-back vs write-through |

| Directory implementation | Linear lists vs hash tables vs B-trees |

Project 1: Hex Dump Disk Explorer

- File: FILESYSTEM_INTERNALS_LEARNING_PROJECTS.md

- Programming Language: C

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Filesystems / Binary Parsing

- Software or Tool: Hex Editors

- Main Book: “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” by Arpaci-Dusseau

What you’ll build: A command-line tool that reads raw disk images or block devices and visualizes filesystem structures—superblocks, inode tables, directory entries, and data blocks—in human-readable format.

Why it teaches filesystems: Before you can build a filesystem, you need to see one. This project forces you to understand exactly how bytes on disk translate to the files and directories you see. You’ll parse real ext2/ext4 structures and decode them byte-by-byte.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Reading and interpreting the superblock at byte 1024 (understanding magic numbers, block sizes, inode counts)

- Navigating block groups and locating inode tables

- Decoding inode structures (permissions, timestamps, block pointers, indirect blocks)

- Parsing directory entries and following file paths through the tree

Key Concepts:

- Superblock structure: The Second Extended File System - nongnu.org - Official ext2 documentation

- Block groups and inodes: “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” Ch. 40 (File System Implementation)

- Binary file I/O in C: “C Programming: A Modern Approach” Ch. 22 by K.N. King

- Disk layout visualization: OSDev Wiki - Ext2

Difficulty: Beginner-Intermediate Time estimate: 1-2 weeks Prerequisites: C basics, understanding of structs and pointers, hex/binary familiarity

Real world outcome:

- Run

./fsexplore disk.imgand see output like:SUPERBLOCK at offset 1024: Magic: 0xEF53 ✓ (ext2 signature) Block size: 4096 bytes Inodes: 128016 Free blocks: 45231 INODE #2 (root directory): Type: Directory Size: 4096 bytes Permissions: drwxr-xr-x Links: 23 Direct blocks: [258, 0, 0, ...] DIRECTORY at block 258: [2] . [2] .. [11] lost+found [12] home [13] etc

Learning milestones:

- After parsing the superblock - you understand that filesystems are just structured data at known offsets

- After reading inodes - you see how Unix “everything is a file” actually works

- After traversing directories - you understand path resolution and why

..exists

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How does a filesystem actually store my files on disk? What does ‘ext2’ really mean?”

Before you write any code, sit with this question. When you create a file named “hello.txt” and write “Hello World” to it, where do those bytes actually go? How does the OS know which disk sectors contain your file versus someone else’s? How can you have both a 1KB file and a 10GB file on the same disk?

Most developers treat filesystems as black boxes—you call open(), read(), write(), and “it just works.” But underneath, every filesystem is solving the same fundamental problems:

- How to organize disk space (blocks, allocation, fragmentation)

- How to map filenames to data (inodes, directory entries, path traversal)

- How to track metadata (permissions, timestamps, file size)

This project rips away the abstraction. You’ll read raw disk bytes and decode the exact structures that ext2 uses. When you finish, you’ll see filesystems not as magic, but as elegant data structures mapped onto persistent storage.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

1. Binary File I/O in C

- How do you open a file in binary mode? (

fopen(path, "rb")) - What’s the difference between

fread()andfscanf()? - How do you seek to a specific byte offset? (

fseek(),lseek()) - Why is byte alignment important when reading structs from disk?

- Book Reference: “C Programming: A Modern Approach” Ch. 22 - K.N. King

2. Structs and Binary Data Layout

- How are struct members laid out in memory?

- What is struct padding, and why does it exist?

- How does

#pragma packaffect struct layout? - Why might the same struct have different sizes on different architectures?

- Book Reference: “The C Programming Language” Ch. 6 - Kernighan & Ritchie

3. Hexadecimal and Binary Number Systems

- Why is hex the natural way to read binary data?

- How do you interpret multi-byte integers (endianness)?

- What does “0xEF53” as a magic number mean?

- How do bitmasks work? (e.g.,

0x01FFfor file permissions) - Book Reference: “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” Ch. 2 - Bryant & O’Hallaron

4. Disk Blocks and Sectors

- What is a disk sector? (historically 512 bytes, now often 4096)

- What is a filesystem block? (often 4096 bytes, configurable)

- Why are blocks larger than sectors?

- How do block offsets relate to byte offsets?

- Book Reference: “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” Ch. 37-39 (Hard Disk Drives, Files and Directories)

5. The ext2 Filesystem Structure

- What is a superblock, and why is it at offset 1024?

- What are block groups, and why do they exist?

- What is an inode, and what information does it store?

- How do directory entries differ from regular file data?

- Book Reference: “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” Ch. 40 (File System Implementation)

- Web Reference: The Second Extended File System - nongnu.org

6. Pointer Indirection in Filesystems

- What are direct block pointers?

- Why do filesystems need indirect, double-indirect, and triple-indirect pointers?

- How does indirection limit maximum file size?

- How do you calculate which data block to read for byte offset N in a file?

- Book Reference: “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” Ch. 40 (Multi-level Index section)

7. Directory Structure and Path Resolution

- How are directory entries stored differently than regular files?

- What makes “.” and “..” special?

- How does the filesystem resolve “/home/user/file.txt” to an inode number?

- Why is the root directory always inode 2?

- Book Reference: “The Linux Programming Interface” Ch. 18 (Directories and Links)

Test Yourself Before Proceeding:

- Can you draw the memory layout of a struct with padding?

- Can you explain why ext2 uses block groups instead of one giant inode table?

- Can you calculate the maximum file size given 12 direct pointers, 1 indirect, 1 double-indirect, and 1 triple-indirect pointer with 4096-byte blocks and 4-byte pointers?

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

Phase 1: Reading the Superblock

- Finding the Superblock

- Why is the ext2 superblock always at byte offset 1024?

- What happens in the first 1024 bytes? (Boot sector space)

- How do you read exactly 1024 bytes starting at offset 1024?

- Validating the Filesystem

- What is the “magic number” for ext2? (0xEF53)

- Where in the superblock struct is the magic number located?

- What should your program do if the magic number is wrong?

- Interpreting Superblock Fields

- How do you determine the block size from

s_log_block_size? (1024 « s_log_block_size) - What does

s_inodes_counttell you? - How many block groups exist? (blocks_count / blocks_per_group)

- How do you determine the block size from

Phase 2: Navigating to Inodes

- Locating the Block Group Descriptor Table

- Where does the BGDT start? (Immediately after superblock)

- How big is each block group descriptor struct?

- How do you calculate which block group contains a given inode number?

- Reading an Inode

- Given inode number N, which block group is it in?

- Within that group, what is the byte offset of inode N in the inode table?

- What is the size of an inode struct? (usually 128 bytes)

- Decoding Inode Metadata

- How do you extract file type from

i_mode? (Use bitmasks: S_IFMT, S_IFDIR, S_IFREG) - How do you convert

i_modeto Unix permission strings (e.g., “drwxr-xr-x”)? - What are

i_atime,i_mtime,i_ctime? How do you format them as readable dates?

- How do you extract file type from

Phase 3: Following Block Pointers

- Direct Blocks

- An inode has 12 direct block pointers (

i_block[0]throughi_block[11]) - If each block is 4096 bytes, how much data can 12 direct blocks hold?

- How do you read the data in the first direct block?

- An inode has 12 direct block pointers (

- Indirect Blocks

i_block[12]points to an indirect block (a block full of block pointers)- If block pointers are 4 bytes, how many pointers fit in one 4096-byte block?

- How would you read the 13th data block of a file?

- Handling Sparse Files

- If a block pointer is 0, what does that mean? (Hole in the file)

- How should your viewer display sparse regions?

Phase 4: Parsing Directories

- Directory Entry Structure

- What fields are in

struct ext2_dir_entry_2? (inode, rec_len, name_len, file_type, name) - Why is

rec_lenvariable? (Entries are variable-length due to variable filenames) - How do you iterate through directory entries in a block?

- What fields are in

- Displaying a Directory

- How do you read the directory data blocks from a directory inode?

- How do you extract the filename from a directory entry?

- How do you display “.” and “..” entries?

Phase 5: Pretty Output

- Human-Readable Formatting

- How do you convert a timestamp (Unix epoch) to a date string? (

ctime()) - How do you format file permissions as “rwxr-xr-x”?

- How do you display file sizes with units (KB, MB, GB)?

- How do you convert a timestamp (Unix epoch) to a date string? (

- Hierarchical Display

- If you recurse into subdirectories, how do you prevent infinite loops? (

.and..handling) - How do you indent to show directory depth?

- If you recurse into subdirectories, how do you prevent infinite loops? (

Thinking Exercise

Trace ext2 Structures By Hand

Before coding, draw these structures on paper for a minimal ext2 filesystem:

Scenario: A fresh ext2 filesystem with:

- Block size: 1024 bytes

- Total blocks: 1024 (1MB filesystem)

- Inodes: 128

- One block group

Given files:

/ (root directory, inode 2)

├── hello.txt (inode 12, contains "Hello World\n", 12 bytes)

└── subdir/ (inode 13)

└── test.txt (inode 14, contains "Test\n", 5 bytes)

Questions to trace:

- Superblock (offset 1024)

- Draw the superblock. Where is the magic number 0xEF53?

- Calculate:

s_blocks_count= 1024,s_inodes_count= 128,s_log_block_size= 0 (means 1024)

- Block Group Descriptor Table (offset 2048)

- Draw the single BGDT entry

- Where is the inode bitmap? Block bitmap? Inode table?

- Inode Table

- Draw inode 2 (root directory). What blocks does it use?

- Draw inode 12 (hello.txt). It’s 12 bytes, so it uses 1 block. Which block?

- Directory Data

- Root directory’s data block contains directory entries. Draw the entries:

[inode=2, name="."] [inode=2, name=".."] [inode=12, name="hello.txt"] [inode=13, name="subdir"] - How big is each entry? (variable due to filename length)

- Root directory’s data block contains directory entries. Draw the entries:

- Path Resolution

- Trace “/subdir/test.txt”:

- Start at inode 2 (root)

- Read root’s directory data

- Find “subdir” entry → inode 13

- Read inode 13’s directory data

- Find “test.txt” entry → inode 14

- Read inode 14 to get file data blocks

- Trace “/subdir/test.txt”:

Draw this layout:

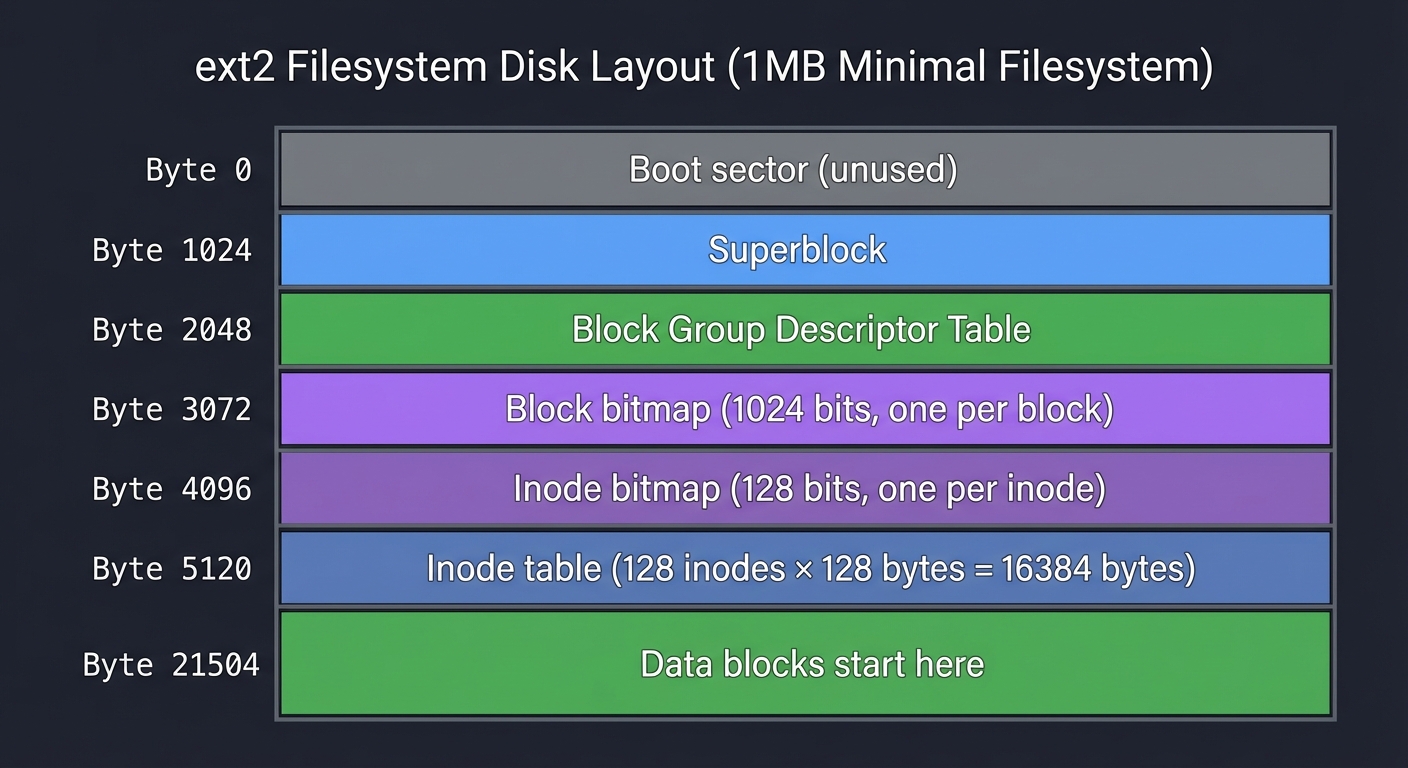

Byte 0 : Boot sector (unused)

Byte 1024 : Superblock

Byte 2048 : Block Group Descriptor Table

Byte 3072 : Block bitmap (1024 bits, one per block)

Byte 4096 : Inode bitmap (128 bits, one per inode)

Byte 5120 : Inode table (128 inodes × 128 bytes = 16384 bytes)

Byte 21504: Data blocks start here

This exercise builds the mental model you need before parsing real disk images.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “What is an inode, and what information does it store?”

- Expected: Metadata (permissions, timestamps, size, owner), block pointers, but NOT the filename

- “How does ext2 resolve a file path like ‘/home/user/file.txt’?”

- Expected: Start at root inode (2), read directory entries, find “home” entry’s inode, repeat for “user”, repeat for “file.txt”

- “Why does ext2 use direct, indirect, double-indirect, and triple-indirect pointers?”

- Expected: Balance between small file efficiency and large file support. Direct pointers make small files fast, indirection allows unbounded growth

- “What is the maximum file size in ext2 with 4096-byte blocks?”

- Expected: Show calculation using pointer levels

- “What happens if a program writes to byte offset 1,000,000,000 in an empty file without writing the bytes before it?”

- Expected: Sparse file with hole (block pointers are 0 for sparse regions)

- “How does the filesystem know if a block is free or in use?”

- Expected: Block bitmap (one bit per block, 1 = used, 0 = free)

- “Why is the superblock at offset 1024 instead of 0?”

- Expected: First 1024 bytes reserved for boot sector/MBR

- “What makes ‘.’ and ‘..’ directory entries special?”

- Expected:

.points to current directory’s inode,..points to parent’s inode, enabling upward traversal

- Expected:

- “How would you implement ‘fsck’ (filesystem consistency check)?”

- Expected: Verify inode/block bitmaps match actual usage, check directory structure integrity, verify hard link counts

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with the superblock

Your first goal: read and display the superblock.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#define EXT2_SUPER_MAGIC 0xEF53

struct ext2_superblock {

uint32_t s_inodes_count;

uint32_t s_blocks_count;

uint32_t s_r_blocks_count;

uint32_t s_free_blocks_count;

uint32_t s_free_inodes_count;

uint32_t s_first_data_block;

uint32_t s_log_block_size;

// ... many more fields

uint16_t s_magic;

// ... padding to match actual struct size

} __attribute__((packed));

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

FILE *disk = fopen(argv[1], "rb");

if (!disk) { perror("fopen"); return 1; }

struct ext2_superblock sb;

fseek(disk, 1024, SEEK_SET); // Superblock at offset 1024

fread(&sb, sizeof(sb), 1, disk);

if (sb.s_magic != EXT2_SUPER_MAGIC) {

fprintf(stderr, "Not an ext2 filesystem!\n");

return 1;

}

printf("Block size: %u bytes\n", 1024 << sb.s_log_block_size);

printf("Total blocks: %u\n", sb.s_blocks_count);

printf("Total inodes: %u\n", sb.s_inodes_count);

fclose(disk);

return 0;

}

Hint 2: Define complete structs

Use the ext2 documentation to define complete structs. Use __attribute__((packed)) to prevent padding.

Hint 3: Calculate offsets carefully

To find inode N:

- Calculate block group:

group = (inode - 1) / inodes_per_group - Read that group’s descriptor to get inode table block number

- Index within inode table:

index = (inode - 1) % inodes_per_group - Byte offset:

inode_table_block * block_size + index * inode_size

Hint 4: Handle endianness

ext2 stores integers in little-endian. On little-endian systems (x86, x86_64), you can read directly. On big-endian systems, you need le32toh(), le16toh().

Hint 5: Parse directory entries carefully

Directory entries are variable-length:

struct ext2_dir_entry_2 {

uint32_t inode;

uint16_t rec_len; // Length of this entry

uint8_t name_len; // Length of filename

uint8_t file_type;

char name[]; // Variable-length (name_len bytes)

} __attribute__((packed));

// Iteration:

char *block_data = /* read directory's data block */;

struct ext2_dir_entry_2 *entry = (struct ext2_dir_entry_2 *)block_data;

while ((char *)entry < block_data + block_size) {

if (entry->inode != 0) { // Valid entry

char filename[256];

memcpy(filename, entry->name, entry->name_len);

filename[entry->name_len] = '\0';

printf("[%u] %s\n", entry->inode, filename);

}

entry = (struct ext2_dir_entry_2 *)((char *)entry + entry->rec_len);

}

Hint 6: Use a hex editor to verify

When in doubt, open the disk image in a hex editor (xxd disk.img | less) and manually verify your offsets and values.

Hint 7: Test with a known image

Create a minimal ext2 image:

dd if=/dev/zero of=test.img bs=1M count=10

mkfs.ext2 test.img

mkdir mnt

sudo mount -o loop test.img mnt

sudo sh -c 'echo "Hello World" > mnt/hello.txt'

sudo sh -c 'mkdir mnt/subdir'

sudo umount mnt

Now you have a test image with known contents.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Binary file I/O in C | “C Programming: A Modern Approach” by K.N. King | Ch. 22 (Input/Output) |

| Struct layout and padding | “The C Programming Language” by Kernighan & Ritchie | Ch. 6 (Structures) |

| Binary data representation | “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” by Bryant & O’Hallaron | Ch. 2 (Representing and Manipulating Information) |

| Filesystem fundamentals | “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” by Arpaci-Dusseau | Ch. 39-40 (Files and Directories, File System Implementation) |

| ext2 structure details | “Understanding the Linux Kernel” by Bovet & Cesati | Ch. 18 (The Ext2 and Ext3 Filesystems) |

| Directory operations | “The Linux Programming Interface” by Michael Kerrisk | Ch. 18 (Directories and Links) |

| Debugger usage for binary inspection | “The Art of Debugging with GDB, DDD, and Eclipse” by Matloff & Salzman | Ch. 1-3 (GDB basics, examining memory) |

Project 2: In-Memory Filesystem with FUSE

- File: FILESYSTEM_INTERNALS_LEARNING_PROJECTS.md

- Programming Language: C

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Filesystems / Kernel Interface

- Software or Tool: FUSE

- Main Book: “The Linux Programming Interface” by Michael Kerrisk

What you’ll build: A complete filesystem that stores files in RAM, mounted as a real directory on your Linux system. Create files, directories, read, write, delete—all backed by your C code.

Why it teaches filesystems: FUSE lets you implement a real, mountable filesystem without writing kernel code. You’ll implement every syscall—open(), read(), write(), mkdir(), unlink()—and understand exactly what happens when a program accesses a file.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Implementing the VFS operations (getattr, readdir, open, read, write, create, unlink, mkdir, rmdir)

- Managing your own inode table and directory structure in memory

- Handling file descriptors and ensuring consistency

- Supporting file permissions and timestamps (stat structure)

Resources for implementing FUSE callbacks:

- Writing a FUSE Filesystem: a Tutorial - The definitive hands-on tutorial with working code

- IBM Developer - Develop your own filesystem with FUSE - Excellent conceptual overview

Key Concepts:

- VFS abstraction: “Understanding the Linux Kernel” Ch. 12 by Bovet & Cesati

- File operations syscalls: “The Linux Programming Interface” Ch. 4-5 by Michael Kerrisk

- FUSE high-level API: libfuse GitHub

- Directory entry management: Writing a Simple Filesystem Using FUSE

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 2-3 weeks Prerequisites: Project 1 or equivalent understanding, comfort with C pointers and structs

Real world outcome:

$ mkdir /tmp/myfs

$ ./memfs /tmp/myfs

$ cd /tmp/myfs

$ echo "Hello filesystem!" > test.txt

$ cat test.txt

Hello filesystem!

$ ls -la

total 0

drwxr-xr-x 2 user user 0 Dec 18 10:00 .

drwxr-xr-x 3 user user 4096 Dec 18 10:00 ..

-rw-r--r-- 1 user user 18 Dec 18 10:01 test.txt

$ mkdir subdir

$ # Your filesystem is real and mounted!

Learning milestones:

- After implementing getattr/readdir - you understand how

lsactually works - After implementing read/write - you see buffering and offset management

- After implementing create/unlink - you understand inode lifecycle and reference counting

The Core Question You’re Answering

“What actually happens when a program calls open(), read(), or write()? How does the kernel translate those syscalls into filesystem operations?”

Before you start coding, think about this: When you type cat file.txt, what happens? The cat program calls open("file.txt", O_RDONLY). The kernel receives this system call and needs to:

- Resolve “file.txt” to an inode number

- Check permissions

- Allocate a file descriptor

- Return that descriptor to

cat

Then cat calls read(fd, buffer, size), and the kernel needs to:

- Look up which filesystem owns that file descriptor

- Call that filesystem’s

readoperation - Copy data from the filesystem into the user’s buffer

FUSE (Filesystem in Userspace) lets you implement these operations in a regular C program instead of kernel code. You become the “filesystem” that the kernel calls. When a user runs ls /mnt/myfs, the kernel asks YOUR code for directory contents.

This project demystifies the Virtual Filesystem (VFS) layer. You’ll see exactly how high-level operations like “list directory” decompose into low-level filesystem callbacks.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

1. What is FUSE and How Does It Work?

- What does “Filesystem in Userspace” mean?

- How does FUSE bridge kernel VFS operations to userspace code?

- What is

libfuse, and what does it provide? - What are the advantages of userspace filesystems vs kernel modules?

- Book Reference: “The Linux Programming Interface” by Michael Kerrisk - Ch. 14 (File Systems)

- Web Reference: IBM Developer - Develop your own filesystem with FUSE

2. The VFS Interface and File Operations

- What is the Virtual Filesystem layer?

- What operations does VFS expect every filesystem to implement?

- What is the difference between

open,read,write,create,mkdir,unlink,rmdir? - What is

getattr(stat), and why is it called so frequently? - Book Reference: “Understanding the Linux Kernel” by Bovet & Cesati - Ch. 12 (Virtual Filesystem)

- Book Reference: “Linux System Programming” by Robert Love - Ch. 3 (Buffered I/O)

3. File Metadata and the stat Structure

- What information is in

struct stat? (permissions, size, timestamps, inode number, link count) - What are

st_mode,st_size,st_mtime,st_nlink? - How do you construct a valid

st_modefor a directory vs regular file? - What is the difference between

st_atime,st_mtime, andst_ctime? - Book Reference: “The Linux Programming Interface” by Michael Kerrisk - Ch. 15 (File Attributes)

4. Directory Operations

- How are directories different from regular files?

- What is a directory entry (dirent)?

- How does

readdir()work internally? - Why do directories have special permissions (execute permission = “searchable”)?

- Book Reference: “The Linux Programming Interface” by Michael Kerrisk - Ch. 18 (Directories and Links)

5. File Paths and Inode Numbers

- What is the relationship between filenames and inodes?

- Why do filesystems separate filenames (directory entries) from file data (inodes)?

- What is a hard link, and how does link count work?

- Why does every directory have at least 2 links (

.and parent’s entry)? - Book Reference: “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” by Arpaci-Dusseau - Ch. 39 (Files and Directories)

6. Memory Management for In-Memory Data Structures

- How will you store your filesystem’s data? (Hash table? Array? Tree?)

- What data structures do you need? (inode table, directory entries, file contents)

- How do you allocate and free file data?

- How do you handle concurrent access? (Do you need locking?)

- Book Reference: “C Interfaces and Implementations” by David Hanson - Ch. 5 (Arena) and Ch. 11 (Table)

7. FUSE Callback Signatures

- What is

fuse_operationsstruct? - What are the parameters for

getattr,readdir,read,write,create, etc.? - What return values does FUSE expect? (0 for success, -errno for errors)

- What is the

fuse_file_infostructure used for? - Web Reference: Writing a FUSE Filesystem: a Tutorial

Test Yourself Before Proceeding:

- Can you explain the call chain from

ls /mnt/myfsto your FUSEreaddircallback? - Do you know what

st_modebits represent a directory with rwxr-xr-x permissions? - Can you design a data structure to store in-memory inodes and their data?

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

Phase 1: Minimal Mountable Filesystem

- Setting Up FUSE

- How do you initialize a FUSE filesystem? (

fuse_main()) - What is the minimum set of operations to implement? (getattr, readdir for root)

- How do you mount your filesystem? (

./myfs /mnt/point)

- How do you initialize a FUSE filesystem? (

- Implementing getattr for Root

- What should

getattr("/")return? - How do you fill

struct statfor a directory? - What inode number should root have? (Conventionally 1)

- What should

- Implementing readdir for Root

- What entries should an empty root directory contain? (

.and..) - How do you use the

fillercallback function? - What happens if readdir returns success but adds no entries?

- What entries should an empty root directory contain? (

Phase 2: Creating Files

- Implementing create

- What does

create(path, mode, fi)need to do? - How do you allocate a new inode?

- Where do you store the mapping from path to inode?

- What initial stat values should a new file have?

- What does

- Implementing getattr for Files

- How do you look up a file’s inode from its path?

- How does

getattrdiffer for files vs directories? - What should you return if the file doesn’t exist? (-ENOENT)

- Implementing open

- What’s the difference between

createandopen? - What should

openreturn? (0 for success, or setfi->fhto file handle) - Do you need to track open file descriptors?

- What’s the difference between

Phase 3: Reading and Writing

- Implementing write

- How do you handle

write(path, buf, size, offset, fi)? - How do you grow a file if writing past EOF?

- How do you update

st_sizeandst_mtime? - What if offset is in the middle of the file?

- How do you handle

- Implementing read

- How do you handle

read(path, buf, size, offset, fi)? - What if offset is past EOF? (Return 0 bytes)

- What if size is larger than available data? (Return partial read)

- How do you update

st_atime?

- How do you handle

- Data Storage

- How do you store file contents in memory? (Dynamic array? Linked list of chunks?)

- Do you pre-allocate space or allocate on demand?

- How do you handle sparse writes (offset with gaps)?

Phase 4: Directories

- Implementing mkdir

- How do you create a new directory?

- What initial entries should it have? (

.and..) - How do you link it to its parent? (Parent’s

..link count)

- Implementing readdir for Subdirectories

- How do you list a directory’s entries?

- How do you iterate through child inodes?

- How do you handle nested paths like

/subdir/file.txt?

- Path Resolution

- How do you parse

/a/b/cinto components? - How do you traverse from root to find the target inode?

- What if a component doesn’t exist?

- How do you parse

Phase 5: Deletion

- Implementing unlink (delete file)

- How do you remove a file?

- What happens to its inode and data?

- How do you remove it from parent directory’s entries?

- Implementing rmdir (delete directory)

- How is rmdir different from unlink?

- What if the directory is not empty? (Return -ENOTEMPTY)

- How do you update parent’s link count?

Thinking Exercise

Design Your In-Memory Data Structures

Before coding, design the data structures on paper. Here’s one approach:

Scenario: Your filesystem stores everything in RAM.

// Global inode table (simple array, max 1024 inodes)

struct inode {

uint32_t ino; // Inode number

mode_t mode; // File type and permissions

nlink_t nlink; // Hard link count

off_t size; // File size in bytes

time_t atime, mtime, ctime;

char *data; // File contents (NULL for directories)

struct dirent *entries; // Directory entries (NULL for files)

size_t num_entries;

} inodes[1024];

// Directory entry

struct dirent {

uint32_t ino;

char name[256];

};

Questions to trace:

- Creating

/hello.txt- User calls

touch /hello.txt - Kernel calls your

create("/hello.txt", 0644, fi) - You allocate inode 2, set

mode = S_IFREG | 0644,size = 0,data = NULL - You add dirent

{ino=2, name="hello.txt"}to root’s entries

- User calls

- Writing “Hello World”

- User calls

echo "Hello World" > /hello.txt - Kernel calls your

write("/hello.txt", "Hello World\n", 12, 0, fi) - You find inode 2, allocate

data = malloc(12), copy buffer - You set

size = 12, updatemtime

- User calls

- Reading the file

- User calls

cat /hello.txt - Kernel calls

getattr→ you returnsize=12 - Kernel calls

read("/hello.txt", buf, 12, 0, fi) - You find inode 2,

memcpy(buf, inodes[2].data, 12), return 12

- User calls

- Creating a directory

/subdir- User calls

mkdir /subdir - Kernel calls

mkdir("/subdir", 0755) - You allocate inode 3, set

mode = S_IFDIR | 0755 - You allocate

entries = malloc(2 * sizeof(struct dirent)) - You add

{ino=3, name="."}and{ino=1, name=".."} - You add

{ino=3, name="subdir"}to root’s entries - You increment root’s

nlink(because subdir’s..links to root)

- User calls

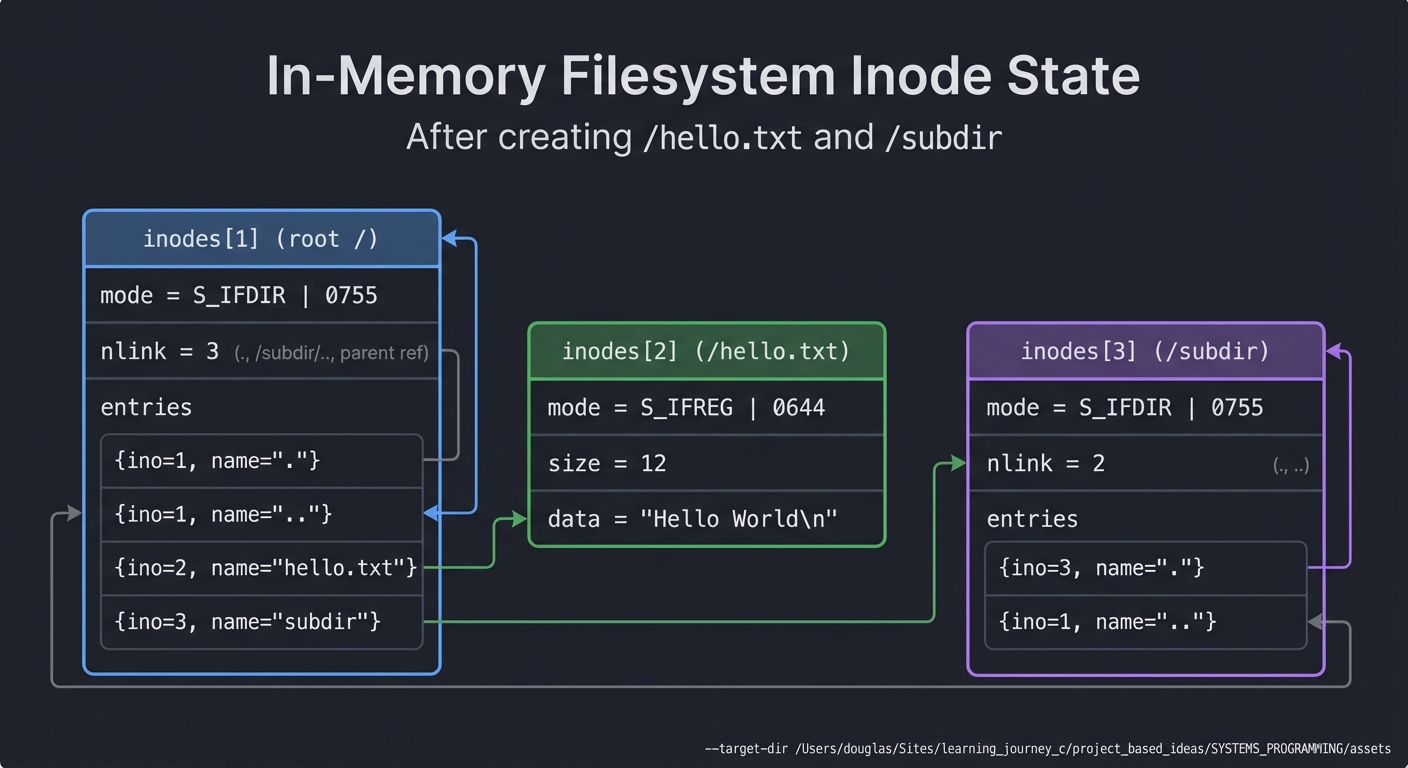

Draw the state after these operations:

inodes[1] (root /):

mode = S_IFDIR | 0755

nlink = 3 (., /subdir/.., /hello.txt's parent)

entries = [{ino=1, name="."}, {ino=1, name=".."}, {ino=2, name="hello.txt"}, {ino=3, name="subdir"}]

inodes[2] (/hello.txt):

mode = S_IFREG | 0644

size = 12

data = "Hello World\n"

inodes[3] (/subdir):

mode = S_IFDIR | 0755

nlink = 2 (., ..)

entries = [{ino=3, name="."}, {ino=1, name=".."}]

This mental model is critical before you write code.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “What is FUSE, and why is it useful?”

- Expected: Allows implementing filesystems in userspace without kernel modules. Easier debugging, safer (crashes don’t kernel panic), faster development

- “What happens when you run ‘ls’ on a FUSE filesystem?”

- Expected:

lscallsopendir()→ kernel calls yourreaddir()→ you return directory entries → kernel passes them tols

- Expected:

- “What is getattr, and why is it called so frequently?”

- Expected: It’s

stat(). Called for every file to get metadata.ls -l, tab completion, file managers all call it constantly

- Expected: It’s

- “How does a filesystem resolve a path like ‘/a/b/c’?”

- Expected: Start at root inode, read root’s directory, find entry “a”, get inode for “a”, read “a”’s directory, find “b”, repeat for “c”

- “What’s the difference between create and open?”

- Expected:

createmakes a new file,openopens existing. If O_CREAT flag is set,opencan create too

- Expected:

- “Why do directories have link count >= 2?”

- Expected: Every directory has at least: (1) its own

.entry, (2) its parent’s entry for the directory name. Each subdirectory adds 1 more (for its..)

- Expected: Every directory has at least: (1) its own

- “What should read() return if offset is past EOF?”

- Expected: 0 bytes (EOF indicator, not an error)

- “How would you implement hard links?”

- Expected: Multiple directory entries point to same inode. Increment inode’s

nlink. Only delete inode data whennlinkreaches 0

- Expected: Multiple directory entries point to same inode. Increment inode’s

- “What’s the difference between st_mtime and st_ctime?”

- Expected:

mtime= modification time (data changed),ctime= change time (metadata changed, like chmod)

- Expected:

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with the minimal FUSE skeleton

#define FUSE_USE_VERSION 31

#include <fuse.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <errno.h>

static int myfs_getattr(const char *path, struct stat *stbuf,

struct fuse_file_info *fi) {

memset(stbuf, 0, sizeof(struct stat));

if (strcmp(path, "/") == 0) {

stbuf->st_mode = S_IFDIR | 0755;

stbuf->st_nlink = 2;

return 0;

}

return -ENOENT;

}

static int myfs_readdir(const char *path, void *buf, fuse_fill_dir_t filler,

off_t offset, struct fuse_file_info *fi,

enum fuse_readdir_flags flags) {

if (strcmp(path, "/") != 0)

return -ENOENT;

filler(buf, ".", NULL, 0, 0);

filler(buf, "..", NULL, 0, 0);

return 0;

}

static struct fuse_operations myfs_oper = {

.getattr = myfs_getattr,

.readdir = myfs_readdir,

};

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

return fuse_main(argc, argv, &myfs_oper, NULL);

}

Compile: gcc -Wall myfs.c -o myfs $(pkg-config fuse3 --cflags --libs)

Mount: mkdir /tmp/myfs && ./myfs /tmp/myfs

Test: ls /tmp/myfs (should show empty directory)

Unmount: fusermount -u /tmp/myfs

Hint 2: Build an inode allocator

#define MAX_INODES 1024

struct inode {

uint32_t ino;

mode_t mode;

off_t size;

time_t mtime;

char *data; // for files

// For directories, you'd add entry list

} inodes[MAX_INODES];

int next_ino = 1; // Start at 1 (or 2 if reserving 1 for root)

int alloc_inode(mode_t mode) {

if (next_ino >= MAX_INODES) return -1;

int ino = next_ino++;

inodes[ino].ino = ino;

inodes[ino].mode = mode;

inodes[ino].size = 0;

inodes[ino].mtime = time(NULL);

return ino;

}

Hint 3: Implement a path-to-inode lookup

For simplicity, use a global table mapping paths to inodes:

#define MAX_FILES 1024

struct path_map {

char path[256];

uint32_t ino;

} path_table[MAX_FILES];

int num_paths = 0;

int lookup_inode(const char *path) {

for (int i = 0; i < num_paths; i++) {

if (strcmp(path_table[i].path, path) == 0)

return path_table[i].ino;

}

return -1; // Not found

}

void add_path(const char *path, uint32_t ino) {

strcpy(path_table[num_paths].path, path);

path_table[num_paths].ino = ino;

num_paths++;

}

Hint 4: Implement create

static int myfs_create(const char *path, mode_t mode,

struct fuse_file_info *fi) {

int ino = alloc_inode(S_IFREG | mode);

if (ino < 0) return -ENOSPC;

add_path(path, ino);

return 0;

}

Hint 5: Implement write

static int myfs_write(const char *path, const char *buf, size_t size,

off_t offset, struct fuse_file_info *fi) {

int ino = lookup_inode(path);

if (ino < 0) return -ENOENT;

// Grow file if needed

if (offset + size > inodes[ino].size) {

inodes[ino].data = realloc(inodes[ino].data, offset + size);

inodes[ino].size = offset + size;

}

memcpy(inodes[ino].data + offset, buf, size);

inodes[ino].mtime = time(NULL);

return size;

}

Hint 6: Implement read

static int myfs_read(const char *path, char *buf, size_t size,

off_t offset, struct fuse_file_info *fi) {

int ino = lookup_inode(path);

if (ino < 0) return -ENOENT;

if (offset >= inodes[ino].size)

return 0; // EOF

if (offset + size > inodes[ino].size)

size = inodes[ino].size - offset;

memcpy(buf, inodes[ino].data + offset, size);

return size;

}

Hint 7: Debug with FUSE in foreground

Run with -f to keep FUSE in foreground and see debug output:

./myfs -f /tmp/myfs

Enable debug logging:

./myfs -f -d /tmp/myfs

Hint 8: Common errors

- “Transport endpoint is not connected”: Mount point is stale.

fusermount -u /tmp/myfsfirst - getattr returning wrong mode: Make sure to use

S_IFDIRfor directories,S_IFREGfor files - readdir showing nothing: Check that

filleris being called with correct arguments

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| FUSE fundamentals | “The Linux Programming Interface” by Michael Kerrisk | Ch. 14 (File Systems - FUSE section) |

| VFS layer concepts | “Understanding the Linux Kernel” by Bovet & Cesati | Ch. 12 (The Virtual Filesystem) |

| File I/O and syscalls | “Linux System Programming” by Robert Love | Ch. 3 (Buffered I/O) & Ch. 4 (Advanced File I/O) |

| File metadata (stat) | “The Linux Programming Interface” by Michael Kerrisk | Ch. 15 (File Attributes) |

| Directory operations | “The Linux Programming Interface” by Michael Kerrisk | Ch. 18 (Directories and Links) |

| Filesystem implementation | “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” by Arpaci-Dusseau | Ch. 40 (File System Implementation) |

| Data structures for filesystems | “C Interfaces and Implementations” by David Hanson | Ch. 5 (Arena), Ch. 11 (Table) |

| Memory management in C | “Understanding and Using C Pointers” by Richard Reese | Ch. 2 (Dynamic Memory Management) |

Project 3: Persistent Block-Based Filesystem

- File: FILESYSTEM_INTERNALS_LEARNING_PROJECTS.md

- Programming Language: C

- Coolness Level: Level 5: Pure Magic (Super Cool)

- Business Potential: 5. The “Industry Disruptor”

- Difficulty: Level 4: Expert

- Knowledge Area: Filesystems / Storage

- Software or Tool: Block Devices

- Main Book: “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” by Arpaci-Dusseau

What you’ll build: Extend your FUSE filesystem to persist data to a file (simulating a disk). Implement proper block allocation with bitmaps, inode structures, and data blocks—a mini ext2.

Why it teaches filesystems: This is where theory meets practice. You’ll implement the exact same structures used in ext2/ext3—superblock, block group descriptors, inode tables, data block bitmaps—and understand why these structures exist.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Designing and writing a superblock with filesystem metadata

- Implementing bitmap-based block allocation (finding free blocks, marking used/free)

- Managing indirect blocks for large files (single, double, triple indirection)

- Handling crash consistency (what happens if power fails mid-write?)

Key Concepts:

- Block allocation strategies: “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” Ch. 40-41

- ext2 on-disk layout: Design and Implementation of the Second Extended Filesystem

- Indirect block pointers: Rose-Hulman Ext2 Lab

- Free space management: “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” Ch. 9 (Virtual Memory concepts apply)

Difficulty: Intermediate-Advanced Time estimate: 3-4 weeks Prerequisites: Project 2 completed

Real world outcome:

$ ./mkfs.myfs -s 100M disk.img # Create 100MB filesystem

$ ./myfs disk.img /mnt/myfs # Mount it

$ cp -r ~/Documents/* /mnt/myfs/ # Copy real files

$ umount /mnt/myfs # Unmount

$ ./myfs disk.img /mnt/myfs # Remount - files persist!

$ ls /mnt/myfs

Documents report.pdf photos/

$ ./fsck.myfs disk.img # Your own filesystem checker

Checking superblock... OK

Checking inode bitmap... OK

Checking block bitmap... OK

Free blocks: 24531/25600

Learning milestones:

- After implementing block bitmaps - you understand why fragmentation happens

- After implementing indirect blocks - you see why there’s a maximum file size

- After adding persistence - you understand the “sync” problem and why databases use WAL

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do you turn ephemeral bits in RAM into persistent data on disk that survives crashes and reboots?”

This is the fundamental question that separates toy filesystems from real ones. In-memory filesystems are elegant, but the moment you need persistence, you enter a world of complexity: block allocation, fragmentation, indirect pointers, and the eternal “what if the power fails during a write?” problem.

Before you implement anything, sit with this: Every file you’ve ever saved to disk went through this exact process. The PDF you downloaded, the code you wrote yesterday—all of it exists as carefully managed blocks on a spinning platter or flash cells. You’re about to build that magic yourself.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

1. Block-Level I/O and Disk Abstraction

- What is a “block” in storage systems? (Typically 4KB)

- How does

lseek()+read()/write()differ from memory operations? - Why do filesystems work with blocks instead of individual bytes?

- What happens when you write to a file? (RAM → page cache → disk)

- Book Reference: “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” Ch. 37 (Hard Disk Drives) & Ch. 39 (Files and Directories) — Arpaci-Dusseau

2. Superblock: The Filesystem’s Master Record

- What metadata must persist to disk for the filesystem to work after reboot?

- Why is the superblock at a fixed offset (byte 1024 for ext2)?

- What happens if the superblock is corrupted?

- How do you verify superblock integrity? (Magic numbers)

- Book Reference: “The Linux Programming Interface” Ch. 14 (File Systems) — Michael Kerrisk

3. Bitmap-Based Block Allocation

- How does a bitmap represent free vs used blocks?

- What’s the algorithm to find a free block? (linear scan? skip lists?)

- Why might you group blocks (block groups in ext2)?

- What’s the difference between internal and external fragmentation?

- Book Reference: “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” Ch. 40 (File System Implementation) — Arpaci-Dusseau

4. Inode Structure and Metadata

- What metadata does an inode store? (size, permissions, timestamps, block pointers)

- How many bytes does an inode typically take? (128 bytes in ext2)

- Why are inodes numbered starting from 1, not 0?

- What’s the relationship between an inode number and its disk location?

- Book Reference: “Understanding the Linux Kernel” Ch. 12 (The Virtual Filesystem) — Bovet & Cesati

5. Indirect Block Pointers

- Why can’t you just store all block pointers directly in the inode?

- What is single, double, and triple indirection?

- How does indirection determine maximum file size?

- How many blocks can you address with 12 direct + 1 single indirect pointer at 4KB blocks?

- Book Reference: “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” Ch. 40 (File System Implementation, section on indirect pointers) — Arpaci-Dusseau

6. Directory Entries and Path Traversal

- How are directories stored on disk? (Just files containing directory entries)

- What does a directory entry contain? (inode number + name)

- How do you implement

ls? (Read directory, lookup each inode for metadata) - How do you resolve

/home/user/file.txtto an inode? - Book Reference: “The Linux Programming Interface” Ch. 18 (Directories and Links) — Michael Kerrisk

7. Write Ordering and Crash Consistency

- What happens if you crash between allocating an inode and writing its data?

- What happens if you mark a block as used but never write to it?

- Why can’t you just “sync everything” after each operation? (Performance)

- What did

fsckdo before journaling? (Scan entire disk to fix inconsistencies) - Book Reference: “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” Ch. 42 (Crash Consistency: FSCK and Journaling) — Arpaci-Dusseau

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

On-Disk Layout Design

- How do you structure the disk image file?

- Superblock at offset 0 or 1024?

- Block bitmap location?

- Inode bitmap location?

- Inode table starting block?

- Data blocks region?

- How much space does metadata consume?

- If you have a 100MB disk with 4KB blocks, how many blocks for inode table?

- What percentage of disk space is overhead?

Block Allocation

- When creating a file, which blocks do you allocate first?

- Inode first or data blocks first?

- What if allocation fails halfway through?

- How do you track free blocks efficiently?

- Linear bitmap scan?

- Keep a “next free block” hint in the superblock?

- What happens when disk is 95% full?

Inode Management

- What does your inode structure look like?

struct inode { uint32_t mode; // File type + permissions uint32_t size; // File size in bytes uint32_t blocks[12]; // Direct block pointers uint32_t indirect; // Single indirect pointer // ... what else? }; - How do you handle large files?

- With 12 direct blocks (4KB each) = 48KB max

- Add single indirect (points to block of 1024 pointers) = 4MB max

- Is that enough for your filesystem?

Persistence and Caching

- When do you write changes to disk?

- After every operation? (Slow but safe)

- Buffer in RAM and flush periodically? (Fast but risky)

- What’s your

sync()strategy?

- How do you handle partial writes?

- What if you write half a block and crash?

- How does the filesystem know the block is incomplete?

Thinking Exercise

Design Your On-Disk Layout

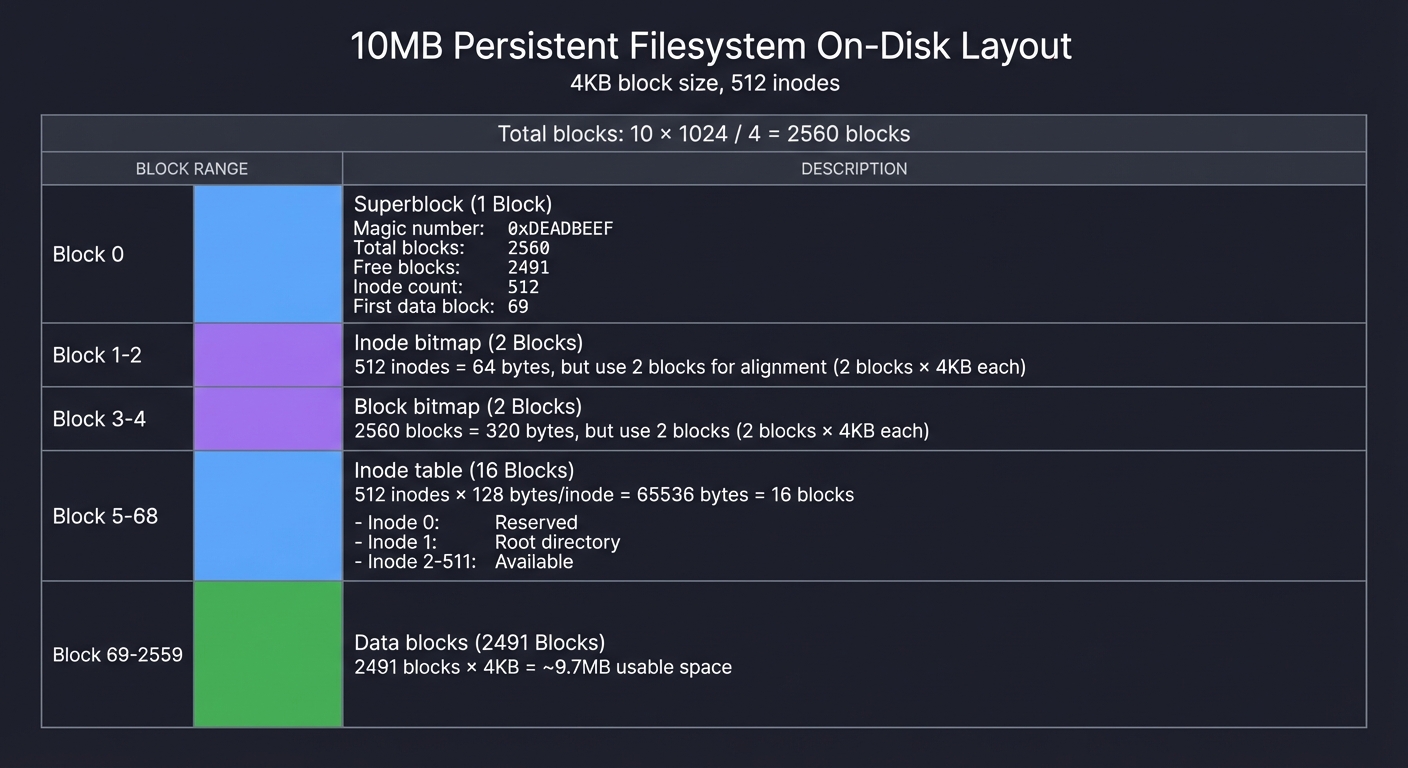

Before coding, draw this on paper for a 10MB disk with 4KB blocks:

Total blocks: 10 * 1024 / 4 = 2560 blocks

Block 0: Superblock

- Magic number: 0xDEADBEEF

- Total blocks: 2560

- Free blocks: ?

- Inode count: 512

- First data block: ?

Block 1-2: Inode bitmap (512 inodes = 64 bytes, but use 2 blocks for alignment)

Block 3-4: Block bitmap (2560 blocks = 320 bytes, but use 2 blocks)

Block 5-68: Inode table (512 inodes * 128 bytes/inode = 64KB = 16 blocks)

- Inode 0: Reserved

- Inode 1: Root directory

- Inode 2-511: Available

Block 69-2559: Data blocks (2491 blocks * 4KB = ~9.7MB usable space)

Questions while designing:

- Why waste space aligning bitmaps to full blocks?

- How do you convert inode number 42 to its disk offset?

- Answer:

offset = inode_table_start + (42 * inode_size)

- Answer:

- If you allocate block 500 for data, how do you mark it in the bitmap?

- Answer:

bitmap[500 / 8] |= (1 << (500 % 8))

- Answer:

- Where does the root directory’s data live?

- In the data blocks region, pointer stored in inode 1

Trace a File Write

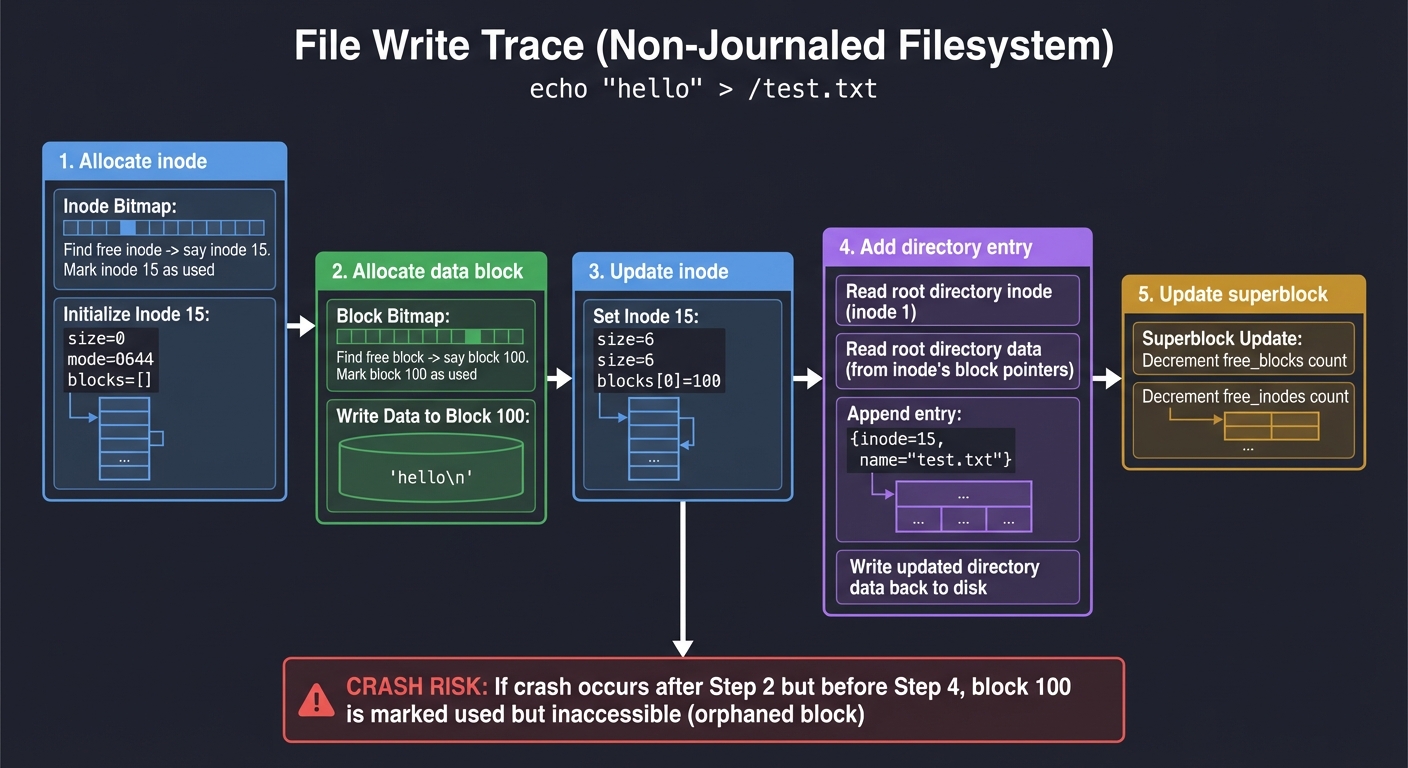

Trace what happens when you write echo "hello" > /test.txt:

Step 1: Allocate inode

- Find free inode in inode bitmap → say inode 15

- Mark inode 15 as used

- Initialize inode: size=0, mode=0644, blocks=[]

Step 2: Allocate data block

- Find free block in block bitmap → say block 100

- Mark block 100 as used

- Write "hello\n" to block 100

Step 3: Update inode

- Set inode 15: size=6, blocks[0]=100

Step 4: Add directory entry

- Read root directory inode (inode 1)

- Read root directory data (from inode's block pointers)

- Append entry: {inode=15, name="test.txt"}

- Write updated directory data back to disk

Step 5: Update superblock

- Decrement free_blocks count

- Decrement free_inodes count

Critical question: What if you crash after Step 2 but before Step 4?

- Block 100 is marked used but inaccessible (no directory entry points to inode 15)

- This is an orphaned block—

fsckwould detect and free it - This is why journaling exists (Project 4)

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “Explain the difference between an inode and a directory entry.”

- Inode: Metadata + block pointers (the actual file data structure)

- Directory entry: Just {inode number, filename} (a pointer to an inode)

- “Why do filesystems use indirect pointers instead of storing all block pointers in the inode?”

- Inode size must be fixed and small (128 bytes in ext2)

- Can’t fit millions of block pointers

- Indirect pointers let you scale to huge files while keeping inodes small

- “What happens when you delete a file?”

- Decrement inode link count

- If link count reaches 0, mark inode as free and mark all data blocks as free

- Directory entry is removed

- Data is NOT overwritten (why file recovery tools work)

- “How does

ls -lget file sizes and permissions?”- Read directory to get inode numbers + names

- For each inode, read inode structure from disk

- Extract size, mode (permissions), timestamps from inode

- “What’s the maximum file size in a filesystem with 12 direct blocks and 1 single indirect block, with 4KB blocks?”

- Direct: 12 * 4KB = 48KB

- Single indirect: 1 block containing 1024 pointers * 4KB = 4MB

- Total: 48KB + 4MB ≈ 4MB

- “Why might you crash-recover to find allocated but unreferenced blocks?”

- Wrote inode and marked blocks used, but crashed before adding directory entry

- Or deleted directory entry but crashed before freeing inode

- These are orphaned inodes/blocks that

fsckcan detect

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with mkfs (format) tool

Before implementing the FUSE filesystem, build a mkfs.myfs tool that creates an empty disk image:

void format_disk(const char* image, size_t size_mb) {

int fd = open(image, O_RDWR | O_CREAT, 0644);

ftruncate(fd, size_mb * 1024 * 1024);

// Write superblock at offset 0

struct superblock sb = {

.magic = 0xDEADBEEF,

.block_size = 4096,

.total_blocks = (size_mb * 1024 * 1024) / 4096,

.inode_count = 512,

// ... initialize bitmaps, etc.

};

write(fd, &sb, sizeof(sb));

// Initialize inode bitmap (all free except inode 1 for root)

// Initialize block bitmap (all free except metadata blocks)

// Create root directory inode

close(fd);

}

Run ./mkfs.myfs disk.img 100 to create a 100MB filesystem.

Hint 2: Implement bitmap operations as functions

// Mark block N as used

void bitmap_set(uint8_t* bitmap, size_t block_num) {

bitmap[block_num / 8] |= (1 << (block_num % 8));

}

// Mark block N as free

void bitmap_clear(uint8_t* bitmap, size_t block_num) {

bitmap[block_num / 8] &= ~(1 << (block_num % 8));

}

// Find first free block

int bitmap_find_free(uint8_t* bitmap, size_t total_blocks) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < total_blocks; i++) {

if (!(bitmap[i / 8] & (1 << (i % 8)))) {

return i;

}

}

return -1; // Disk full

}

Hint 3: Cache the superblock and bitmaps in RAM

Reading from disk is slow. Keep frequently accessed structures in memory:

struct fs_state {

struct superblock sb;

uint8_t* inode_bitmap; // malloc'd

uint8_t* block_bitmap; // malloc'd

struct inode* inode_table; // malloc'd

int disk_fd; // File descriptor for disk image

};

void fs_load(struct fs_state* fs, const char* image) {

fs->disk_fd = open(image, O_RDWR);

read(fs->disk_fd, &fs->sb, sizeof(struct superblock));

// Load bitmaps into RAM

fs->inode_bitmap = malloc(fs->sb.inode_count / 8);

lseek(fs->disk_fd, INODE_BITMAP_OFFSET, SEEK_SET);

read(fs->disk_fd, fs->inode_bitmap, fs->sb.inode_count / 8);

// ... same for block bitmap and inode table

}

Only flush to disk on sync() or unmount.

Hint 4: Implement indirect blocks incrementally

Start with just direct blocks (12 * 4KB = 48KB max file size). Get that working. Then add single indirect:

uint32_t get_block_number(struct inode* inode, size_t block_index) {

if (block_index < 12) {

return inode->blocks[block_index]; // Direct

} else {

// Read indirect block from disk

uint32_t indirect_block[1024];

read_block(inode->indirect, indirect_block);

return indirect_block[block_index - 12];

}

}

Hint 5: Use hexdump to debug your disk image

$ hexdump -C disk.img | head -20

00000000 ef be ad de 00 10 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 02 00 00 |................|

↑ magic number

Verify your superblock, bitmaps, and inodes are where you expect.

Hint 6: Test with small files first

Don’t try to cp -r ~/Documents immediately. Start with:

$ echo "test" > /mnt/myfs/a.txt

$ cat /mnt/myfs/a.txt

test

$ ls -la /mnt/myfs

-rw-r--r-- 1 user user 5 Dec 27 10:00 a.txt

Then gradually increase complexity.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Block allocation and fragmentation | “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” by Arpaci-Dusseau | Ch. 40 (File System Implementation) |

| ext2 on-disk format (the model for this project) | “Understanding the Linux Kernel” by Bovet & Cesati | Ch. 12 (The Virtual Filesystem) & Ch. 18 (The Ext2 and Ext3 Filesystems) |

| Inode structure and indirect pointers | “The Linux Programming Interface” by Michael Kerrisk | Ch. 14 (File Systems: Fundamental Concepts) |

| Bitmap algorithms and data structures | “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” by Bryant & O’Hallaron | Ch. 9.9 (Dynamic Memory Allocation) |

File I/O and lseek for block operations |

“The C Programming Language” by Kernighan & Ritchie | Ch. 8.2 (Low Level I/O - Read and Write) |

| Building a storage allocator (similar to block allocator) | “The C Programming Language” by Kernighan & Ritchie | Ch. 8.7 (Example—A Storage Allocator) |

| Crash consistency and fsck | “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” by Arpaci-Dusseau | Ch. 42 (Crash Consistency: FSCK and Journaling) |

| FUSE API for persistent filesystems | Writing a FUSE Filesystem: a Tutorial | Full tutorial |

Project 4: Journaling Layer

- File: FILESYSTEM_INTERNALS_LEARNING_PROJECTS.md

- Programming Language: C

- Coolness Level: Level 5: Pure Magic (Super Cool)

- Business Potential: 3. The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 5: Master

- Knowledge Area: Crash Consistency / Databases

- Software or Tool: WAL

- Main Book: “Database Internals” by Alex Petrov

What you’ll build: Add write-ahead logging (journaling) to your block-based filesystem. Before any metadata change, log the operation so crashes can be recovered.

Why it teaches filesystems: Journaling is what separates “toy” filesystems from production ones. ext3 added journaling to ext2. You’ll understand why fsck used to take hours and now takes seconds, and why databases and filesystems share the same fundamental insight.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Designing a journal format (transaction records, commit blocks)

- Implementing write-ahead: log first, then apply

- Recovery: replaying committed transactions after crash

- Choosing what to journal (metadata-only vs full data journaling)

Key Concepts:

- Crash consistency problem: “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” Ch. 42 (Crash Consistency: FSCK and Journaling)

- Write-ahead logging: “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” Ch. 7 by Martin Kleppmann

- ext3 journaling: Linux Kernel Documentation - ext4

- Transaction semantics: “Database Internals” Ch. 3 by Alex Petrov

Difficulty: Advanced Time estimate: 2-3 weeks Prerequisites: Project 3 completed

Real world outcome:

$ ./myfs disk.img /mnt/myfs

$ dd if=/dev/urandom of=/mnt/myfs/bigfile bs=1M count=50 &

# Kill power mid-write (or kill -9 the process)

$ ./myfs disk.img /mnt/myfs

Journal recovery: replaying 3 transactions...

Transaction 1: inode 15 allocation - COMMITTED, replaying

Transaction 2: block 1024-1087 allocation - COMMITTED, replaying

Transaction 3: inode 15 size update - INCOMPLETE, discarding

Recovery complete. Filesystem consistent.

$ ls /mnt/myfs # No corruption!

Learning milestones:

- After implementing basic journaling - you understand why “safe eject” matters for USB drives

- After implementing recovery - you see why ext4 mounts instantly after crashes

- After understanding the tradeoffs - you know why databases still use their own journaling

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do you guarantee filesystem consistency when power can fail at any millisecond during a write operation?”

This is the million-dollar question that haunted filesystem designers for decades. Before journaling, if your system crashed mid-operation, you’d reboot to a corrupted filesystem. fsck (filesystem check) would scan the entire disk—taking hours on large drives—to find and fix inconsistencies.

Then in 1993, Linux gained the ext2 filesystem. It was fast, but not crash-safe. A crash could leave orphaned inodes, allocated blocks with no owner, or directories pointing to freed inodes. In 1999, ext3 added one feature to ext2: journaling. That single addition made ext3 mount instantly after crashes, without running fsck.

You’re about to implement that same insight—write-ahead logging. It’s the same technique databases use (PostgreSQL’s WAL, MySQL’s redo log). Understanding this connects filesystems to databases at a fundamental level.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

1. The Crash Consistency Problem

- What happens if you crash between allocating an inode and updating the directory?

- What happens if you crash after writing data but before updating the inode’s size field?

- Why can’t you just write everything atomically? (Writes aren’t atomic across multiple blocks)

- What invariants must a filesystem maintain? (bitmap matches actual allocation, directory entries point to valid inodes, etc.)

- Book Reference: “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” Ch. 42 (Crash Consistency: FSCK and Journaling) — Arpaci-Dusseau

2. Write-Ahead Logging (WAL) Fundamentals

- What does “write-ahead” mean? (Log the change before applying it)

- What is a transaction? (A group of related writes that must succeed or fail together)

- What is a commit record? (Marks a transaction as complete in the log)

- How does recovery work? (Replay committed transactions, discard incomplete ones)

- Book Reference: “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” Ch. 3 (Storage and Retrieval, section on write-ahead log) — Martin Kleppmann

3. Journal Structure and Format

- Where does the journal live? (Reserved region on disk, or separate file)

- What does a journal entry contain? (Transaction ID, operation type, before/after values)

- How do you know where the journal starts and ends? (Sequence numbers, circular buffer)

- How big should the journal be? (Trade-off: larger = more buffering, smaller = more frequent commits)

- Book Reference: “Database Internals” Ch. 3 (Transaction Processing) — Alex Petrov

4. Transaction Semantics

- What is atomicity? (All-or-nothing: transaction either fully commits or fully aborts)

- What is durability? (Once committed, data survives crashes)

- What is idempotency? (Replaying a committed transaction multiple times = same result)

- Why must operations be idempotent for recovery to work?

- Book Reference: “Database Internals” Ch. 5 (Transaction Processing and Recovery) — Alex Petrov

5. Metadata Journaling vs Data Journaling

- Metadata-only journaling: Log inode changes, bitmap updates, directory entries (NOT file data)

- Full data journaling: Log everything including file contents

- Why is metadata journaling faster? (Less data to log)

- What’s the risk of metadata-only journaling? (Stale data blocks might be visible after crash)

- Book Reference: “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” Ch. 42 (section on journaling modes) — Arpaci-Dusseau

6. Checkpointing and Log Truncation

- What is checkpointing? (Applying logged changes to their final locations on disk)

- When can you free journal space? (After changes are checkpointed)

- What if the journal fills up? (Block new writes until checkpoint completes)

- How do you implement a circular journal buffer?

- Book Reference: “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” Ch. 3 (Log-structured storage) — Martin Kleppmann

7. Ordering Constraints and Barriers

- Why can’t you just write the data and then the commit record? (Disk might reorder writes)

- What is a write barrier? (Ensures previous writes complete before continuing)

- How does

fsync()relate to journaling? (Forces pending writes to disk) - Why is journaling still faster than

fsync()after every operation? - Book Reference: “The Linux Programming Interface” Ch. 13 (File I/O Buffering) — Michael Kerrisk

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

Journal Design

- Where will the journal live on disk?

- Reserved blocks at the beginning? (easy to find, wastes space)

- Separate journal file? (flexible, but how to find it?)

- How big should it be? (32MB? 128MB?)

- What will a journal entry look like?

struct journal_entry { uint64_t transaction_id; uint32_t entry_type; // INODE_UPDATE, BLOCK_ALLOC, etc. uint32_t checksum; // Verify integrity // ... payload (what changed) }; - How do you mark a transaction as committed?

- Write a COMMIT entry at the end?

- Use a separate commit bitmap?

- How do you ensure the commit record is durable before returning success?

Recovery Process

- On mount after a crash, how do you replay the journal?

- Scan journal for committed transactions

- Replay each operation (apply logged changes to filesystem)

- What if you crash during replay? (Must be idempotent!)

- How do you handle incomplete transactions?

- If there’s no COMMIT record, discard the transaction

- How do you identify transaction boundaries?

Checkpointing

- When do you apply journal entries to their final locations?

- After every commit? (Slow)

- Periodically? (Every 5 seconds? When journal is 75% full?)

- How do you ensure data is checkpointed before freeing journal space?

- How do you free journal space?

- Once all entries in a region are checkpointed, wrap around

- Circular buffer: head pointer (oldest entry), tail pointer (newest entry)

Performance

- How do you batch operations into transactions?

- Group all changes from one syscall? (e.g.,

write()might update inode + allocate blocks) - What’s the latency vs throughput trade-off?

- Group all changes from one syscall? (e.g.,

Thinking Exercise

Trace a Journaled File Write

Trace what happens when you write echo "hello" > /test.txt with journaling:

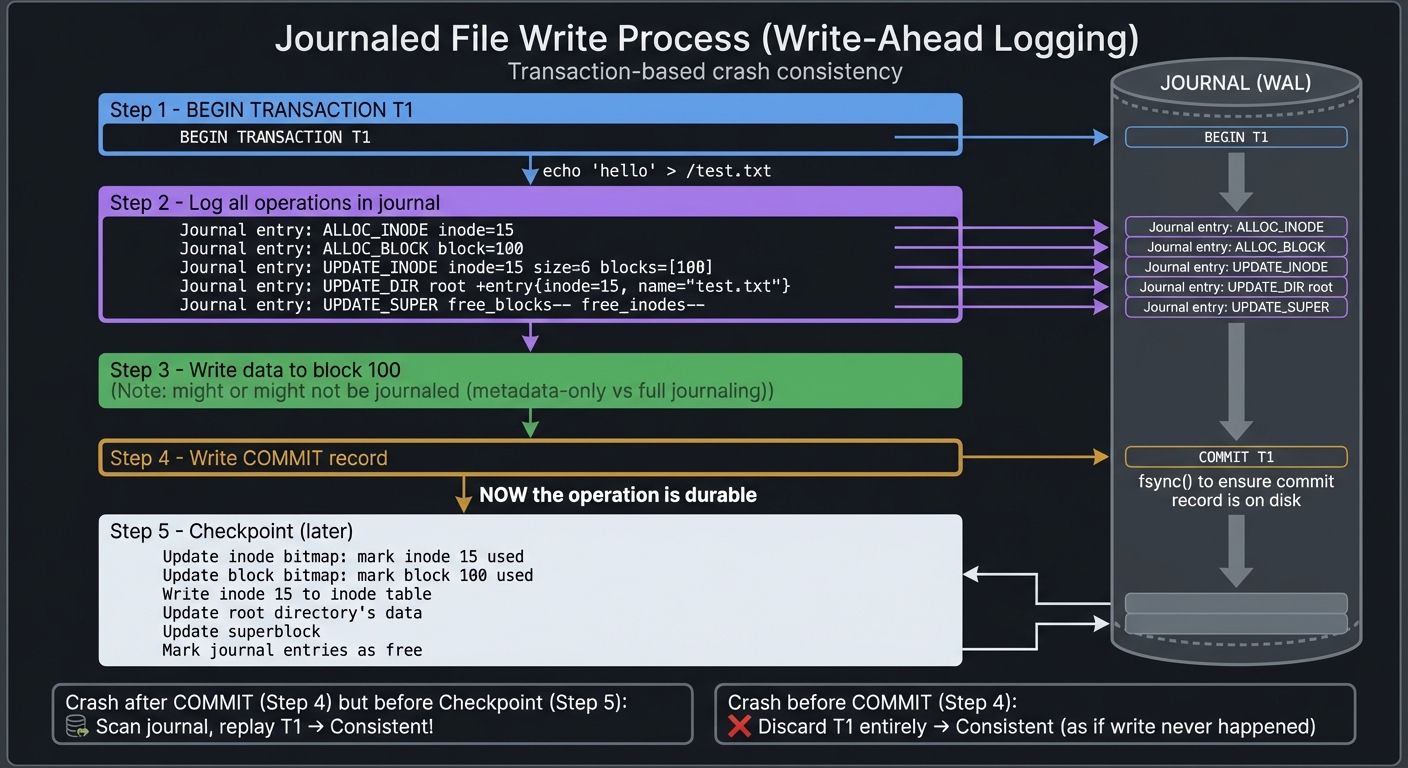

Step 1: BEGIN TRANSACTION T1

- Write journal entry: BEGIN T1

Step 2: Log all operations in the journal

- Journal entry: ALLOC_INODE inode=15

- Journal entry: ALLOC_BLOCK block=100

- Journal entry: UPDATE_INODE inode=15 size=6 blocks=[100]

- Journal entry: UPDATE_DIR root +entry{inode=15, name="test.txt"}

- Journal entry: UPDATE_SUPER free_blocks-- free_inodes--

Step 3: Write data to block 100

- This might or might not be journaled (metadata-only vs full journaling)

Step 4: Write COMMIT record for T1

- Journal entry: COMMIT T1

- fsync() to ensure commit record is on disk

- NOW the operation is durable

Step 5 (later, during checkpoint): Apply logged changes

- Update inode bitmap: mark inode 15 used

- Update block bitmap: mark block 100 used

- Write inode 15 to inode table

- Update root directory's data

- Update superblock

- Mark journal entries as free

Recovery scenario: Crash after Step 4 (committed) but before Step 5 (checkpointed)

- On mount, scan journal, find COMMIT T1

- Replay all logged operations (they’re idempotent, so safe to replay)

- Filesystem is consistent!

Recovery scenario: Crash during Step 2 (logging) before Step 4 (commit)

- On mount, scan journal, no COMMIT for T1

- Discard T1 entirely

- Filesystem is consistent (as if the write never happened)

Compare to non-journaled: Crash after allocating block 100 but before updating directory

- Block 100 is marked used but unreachable → orphan

- Needs full fsck to detect and fix

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “What problem does journaling solve?”

- Crash consistency: Guarantees filesystem is always in a consistent state, even after crashes mid-operation

- “Explain how write-ahead logging works.”

- Log intended changes to a journal before applying them. On crash, replay committed journal entries to restore consistency.

- “What’s the difference between metadata journaling and full data journaling?”

- Metadata: Only log filesystem structure changes (inodes, bitmaps, directories). Faster, but data might be stale.

- Full data: Log everything including file contents. Slower, but guarantees data integrity.

- “Why is journaling faster than running fsck after every crash?”

- Journal is small (MB) vs entire filesystem (GB/TB). Recovery scans journal, not whole disk.

- “What is a transaction, and why must operations be idempotent?”

- Transaction: Atomic group of changes. Idempotent: Replaying the same operation multiple times = same result. Needed because recovery might replay an already-applied transaction.

- “How does the filesystem know which journal entries have been checkpointed?”

- Sequence numbers or pointers. After checkpointing entries 0-100, update a checkpoint marker. Journal entries before that can be freed.

- “What happens if the journal fills up?”

- Block new transactions until a checkpoint completes and frees space, or force an immediate checkpoint (flush to disk).

- “Why do databases like PostgreSQL use WAL, and how is it similar to filesystem journaling?”

- Same principle: Log changes before applying. Enables crash recovery and point-in-time restore. Filesystems protect metadata, databases protect table rows.

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with a simple journal structure

Create a journal as a fixed-size file or reserved disk region:

#define JOURNAL_SIZE (32 * 1024 * 1024) // 32 MB

#define JOURNAL_ENTRY_SIZE 512 // Fixed-size entries

struct journal_superblock {

uint64_t head; // Oldest entry (next to checkpoint)

uint64_t tail; // Newest entry (next to append)

uint64_t next_txn_id;

};

struct journal_entry {

uint64_t txn_id;

uint32_t type; // BEGIN, COMMIT, INODE_UPDATE, etc.

uint32_t checksum;

char payload[496]; // Type-specific data

};

Hint 2: Implement transaction begin/commit

uint64_t journal_begin_txn() {

uint64_t txn_id = journal_sb.next_txn_id++;

struct journal_entry entry = {

.txn_id = txn_id,

.type = TXN_BEGIN,

};

journal_append(&entry);

return txn_id;

}

void journal_commit_txn(uint64_t txn_id) {

struct journal_entry entry = {

.txn_id = txn_id,

.type = TXN_COMMIT,

};

journal_append(&entry);

fsync(journal_fd); // CRITICAL: Ensure commit is on disk!

}

Hint 3: Log each filesystem operation

void create_file_journaled(const char* name) {

uint64_t txn = journal_begin_txn();

// Allocate inode

int ino = alloc_inode();

journal_log_alloc_inode(txn, ino);

// Allocate block

int blk = alloc_block();

journal_log_alloc_block(txn, blk);

// Update inode

journal_log_update_inode(txn, ino, /* new metadata */);

// Add directory entry

journal_log_add_direntry(txn, ROOT_INO, name, ino);

journal_commit_txn(txn);

// Later, checkpoint applies these to disk

}

Hint 4: Implement recovery

void journal_recover() {

uint64_t pos = journal_sb.head;

uint64_t current_txn = 0;

bool is_committed = false;

while (pos < journal_sb.tail) {

struct journal_entry entry;

journal_read(pos, &entry);

if (entry.type == TXN_BEGIN) {

current_txn = entry.txn_id;

is_committed = false;

} else if (entry.type == TXN_COMMIT) {

is_committed = true;

} else if (is_committed && entry.txn_id == current_txn) {

// Replay this operation

replay_journal_entry(&entry);

}

pos += JOURNAL_ENTRY_SIZE;

}

}

Hint 5: Make operations idempotent

Replay might apply the same operation twice. Design operations to be safe when replayed:

// BAD: Not idempotent

void replay_alloc_inode(int ino) {

bitmap_set(inode_bitmap, ino); // If already set, no change

}

// GOOD: Check first

void replay_alloc_inode(int ino) {

if (!bitmap_test(inode_bitmap, ino)) {

bitmap_set(inode_bitmap, ino);

}

}

Or use logged “before” and “after” values:

struct journal_update_inode {

int ino;

struct inode before;

struct inode after;

};

// Replay: Just write "after" value (idempotent)

void replay_update_inode(struct journal_update_inode* op) {

write_inode(op->ino, &op->after);

}

Hint 6: Test crash scenarios

Simulate crashes by killing your program at random points:

$ ./myfs disk.img /mnt/myfs &

$ PID=$!

$ (sleep 2; kill -9 $PID) & # Kill after 2 seconds

$ dd if=/dev/zero of=/mnt/myfs/test bs=1M count=100

# Remount and check if filesystem is consistent

$ ./myfs disk.img /mnt/myfs

Journal recovery: replaying 5 transactions...

$ ls /mnt/myfs # Should work!

Hint 7: Start with metadata-only journaling

Don’t journal file data initially—only log:

- Inode allocation/updates

- Block allocation (bitmap changes)

- Directory entry changes

- Superblock updates

This is what ext3’s default mode does. Add full data journaling later if needed.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Crash consistency and the need for journaling | “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” by Arpaci-Dusseau | Ch. 42 (Crash Consistency: FSCK and Journaling) |

| Write-ahead logging fundamentals | “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” by Martin Kleppmann | Ch. 3 (Storage and Retrieval, section on transaction logs) |

| Transaction processing and recovery | “Database Internals” by Alex Petrov | Ch. 5 (Transaction Processing and Recovery) |

| ext3/ext4 journaling implementation details | “Understanding the Linux Kernel” by Bovet & Cesati | Ch. 18 (The Ext2 and Ext3 Filesystems, journaling section) |

| Filesync and write barriers | “The Linux Programming Interface” by Michael Kerrisk | Ch. 13 (File I/O Buffering) |

| Log-structured storage systems | “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” by Arpaci-Dusseau | Ch. 43 (Log-structured File Systems) |

| Atomicity and durability guarantees | “Database Internals” by Alex Petrov | Ch. 3 (File Formats and Indexing) |

| Real-world journaling challenges | “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” by Martin Kleppmann | Ch. 7 (Transactions) & Ch. 11 (Stream Processing) |

Project 5: Filesystem Comparison Tool

- File: FILESYSTEM_INTERNALS_LEARNING_PROJECTS.md

- Programming Language: C

- Coolness Level: Level 1: Pure Corporate Snoozefest

- Business Potential: 3. The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Performance Analysis / Filesystems

- Software or Tool: Benchmarking

- Main Book: “Systems Performance” by Brendan Gregg

What you’ll build: A tool that mounts and analyzes multiple filesystem types (ext2, FAT32, your custom FS) and produces detailed comparison reports—performance metrics, space efficiency, feature support.

Why it teaches filesystems: Different filesystems make different tradeoffs. By measuring and comparing them, you’ll understand why ext4 is better for Linux, why FAT32 persists for USB drives, and why ZFS exists for data integrity.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Parsing FAT32 structures (FAT table, directory entries, cluster chains)

- Measuring fragmentation levels across filesystem types

- Benchmarking read/write performance with different file sizes

- Analyzing space overhead (metadata vs data ratio)

Key Concepts:

- FAT filesystem structure: “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” Ch. 39 (Interlude: Files and Directories)

- Filesystem performance characteristics: “Systems Performance” by Brendan Gregg

- Comparative analysis: Linux Kernel Filesystems Documentation

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 2 weeks Prerequisites: Project 1 or strong understanding of filesystem structures

Real world outcome:

$ ./fscompare ext4.img fat32.img myfs.img

FILESYSTEM COMPARISON REPORT

============================

ext4 FAT32 MyFS

-------------------------------------------------

Max filename: 255 255 255

Max file size: 16TB 4GB 2GB

Journaling: Yes No Yes

Permissions: Unix None Unix

Case sensitive: Yes No Yes

SPACE EFFICIENCY (1GB disk, 10000 small files):

Metadata overhead: 2.1% 0.8% 3.2%

Avg fragmentation: 1.2% 15.3% 4.1%

Space wasted: 12MB 156MB 31MB

PERFORMANCE (sequential 100MB write):

Write speed: 245 MB/s 198 MB/s 156 MB/s

Read speed: 312 MB/s 287 MB/s 201 MB/s

Learning milestones:

- After parsing FAT32 - you understand why it has 4GB file limit (32-bit cluster pointers)

- After measuring fragmentation - you see why ext4 uses extents instead of block pointers

- After comparing features - you understand filesystem design tradeoffs

Real World Outcome

When you run your filesystem comparison tool, here’s exactly what you’ll see and where:

Command-line execution:

$ ./fscompare --analyze ext4.img fat32.img myfs.img --output comparison_report.txt

Analyzing filesystems...

[1/3] Loading ext4.img (512 MB)... Done (1.2s)

[1/3] Parsing superblock at offset 1024... Valid ext4 signature detected

[1/3] Scanning block groups... Found 4 block groups

[1/3] Reading inode table... 32768 inodes total

[1/3] Performance benchmark starting... Writing 1000 files (100KB each)... 245 MB/s

[2/3] Loading fat32.img (512 MB)... Done (0.8s)

[2/3] Parsing boot sector... Valid FAT32 signature detected

[2/3] Reading FAT table... 2 FATs, 65525 clusters

[2/3] Performance benchmark starting... Writing 1000 files (100KB each)... 198 MB/s

[3/3] Loading myfs.img (512 MB)... Done (1.5s)

[3/3] Parsing superblock... Valid custom FS signature

[3/3] Reading journal... Journal clean, no recovery needed

[3/3] Performance benchmark starting... Writing 1000 files (100KB each)... 156 MB/s

Generating comparison report... Done

Report saved to: comparison_report.txt

HTML visualization saved to: comparison_report.html

In your terminal, the report file shows:

================================================================================

FILESYSTEM COMPARISON REPORT

Generated: 2024-12-27 14:32:01

================================================================================

OVERVIEW

--------

Images analyzed:

- ext4.img 512 MB (Linux ext4 filesystem)

- fat32.img 512 MB (FAT32 filesystem)

- myfs.img 512 MB (Custom journaling filesystem)

FEATURE COMPARISON

------------------