Expert C Programming Mastery - Real World Projects

Goal: Build a compiler-level mental model of C so you can predict what will happen before you run the program. You will learn to read complex declarations as the compiler does, reason about memory layout and object lifetimes, and diagnose linking and ABI issues without guessing. By finishing the projects, you will be able to explain why subtle C behaviors occur, recognize undefined behavior traps, and design safer C interfaces that still respect performance constraints. The outcome is not just “working code,” but reliable, portable, and debuggable systems code.

Introduction

- What is Expert C Programming? It is the craft of understanding how the C language is translated, laid out, and executed at the machine level, including the rules that are not obvious from syntax alone.

- What problem does it solve today? It eliminates costly low-level bugs, performance regressions, and portability failures by helping you reason about the compiler, linker, ABI, and memory model.

- What will you build? Declaration parsers, memory layout visualizers, symbol analyzers, macro expanders, ABI inspectors, and safety tooling that reveal what C is really doing.

- Scope boundaries: This guide focuses on C language mechanics, compilation, linking, and runtime behavior. It does not teach operating system design, C++ features, or full compiler construction.

Big-picture overview (your learning pipeline)

Problem Statement

|

v

C Source -> Mental Model -> Observable Tool/Experiment -> Verified Insight

| | | |

| | v v

| | CLI output / diagnostics You can predict behavior

| |

v v

Compiler/Linker Reality (the real ground truth)

The “Expert C” mindset in one picture

Question: "What will the compiler do with this?"

┌──────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Declarations / Types / Storage Class │

└──────────────────────────────────────────┘

|

v

┌──────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Translation Pipeline (preprocess→link) │

└──────────────────────────────────────────┘

|

v

┌──────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Runtime Reality (ABI, stack, heap) │

└──────────────────────────────────────────┘

|

v

┌──────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Correctness + Portability + Performance│

└──────────────────────────────────────────┘

A famous C gotcha that shows why expertise matters

Why do programmers confuse Halloween and Christmas?

Because Oct 31 = Dec 25

If you do not immediately understand this joke, you are in the right place. Here is the explanation:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ THE HALLOWEEN = CHRISTMAS JOKE │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ In C (and many languages), numbers can be written in different bases: │

│ │

│ OCTAL (base 8): Numbers prefixed with 0 │

│ DECIMAL (base 10): Numbers with no prefix (default) │

│ HEXADECIMAL (base 16): Numbers prefixed with 0x │

│ │

│ The joke: │

│ ───────── │

│ Oct 31 = Octal 31 = 3×8 + 1 = 25 in decimal │

│ Dec 25 = Decimal 25 = 25 │

│ │

│ So: Oct 31 == Dec 25 (both equal 25) │

│ │

│ Halloween (October 31st) "equals" Christmas (December 25th)! │

│ │

│ IN C CODE: │

│ ────────── │

│ int oct = 031; // This is OCTAL! = 25 decimal │

│ int dec = 25; // This is decimal = 25 │

│ printf("%d\n", oct == dec); // Prints: 1 (true!) │

│ │

│ WARNING: This is a common source of bugs! │

│ int permissions = 0644; // Octal 644 = 420 decimal (intentional) │

│ int zip_code = 01234; // Bug! Octal 1234 = 668 decimal (not 1234!) │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

C in the software stack (why C shows up everywhere)

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ THE SOFTWARE STACK │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ ┌───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ YOUR APPLICATION │ │

│ │ (Python, JavaScript, Go, Rust, Java...) │ │

│ └───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ LANGUAGE RUNTIME / VM │ │

│ │ (CPython, V8, Go runtime, JVM, .NET CLR) │ │

│ │ ┌─────────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ Written in C or C++ │ │ │

│ │ └─────────────────────────┘ │ │

│ └───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ C STANDARD LIBRARY │ │

│ │ (glibc, musl, macOS libSystem, MSVCRT) │ │

│ │ printf, malloc, fopen, pthread_create, socket... │ │

│ └───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ SYSTEM CALL INTERFACE │ │

│ │ (The boundary between user and kernel) │ │

│ │ write(), read(), mmap(), fork() │ │

│ └───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ OPERATING SYSTEM KERNEL │ │

│ │ (Linux, macOS XNU, Windows NT) │ │

│ │ ┌─────────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ Written in C │ │ │

│ │ └─────────────────────────┘ │ │

│ └───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ HARDWARE │ │

│ │ (CPU, Memory, Devices - accessed via drivers) │ │

│ └───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ KEY INSIGHT: C is at EVERY level except the hardware itself. │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

How to Use This Guide

- Read the Theory Primer first. It is the mental model you will apply in every project.

- Pick a learning path that matches your goals (interview prep, systems depth, or tooling mastery).

- For each project, start with the Core Question and Thinking Exercise, then build toward the Real World Outcome.

- Use the Definition of Done checklists to validate correctness and reproducibility.

Prerequisites & Background Knowledge

Essential Prerequisites (Must Have)

- Solid C syntax and control flow (functions, loops, structs, arrays)

- Comfort with pointers and basic memory reasoning

- Basic command line usage (compile, run, inspect files)

- Familiarity with compilation steps (preprocess, compile, link)

- Recommended Reading: “The C Programming Language” by Kernighan & Ritchie - Ch. 1-2

Helpful But Not Required

- Assembly reading (learn during Projects 17-18)

- Debugger usage (learn during Projects 3-5, 14)

- ABI knowledge (learn during Projects 4 and 17)

Self-Assessment Questions

- Can you explain why

int *p[10]andint (*p)[10]are different? - Do you know when arrays do not decay to pointers?

- Can you predict the result of comparing signed and unsigned integers?

- Can you explain why modifying a string literal is undefined behavior?

Development Environment Setup Required Tools:

- GCC or Clang (C11 or later)

- GDB or LLDB

nm,objdump,readelf(orotoolon macOS)make

Recommended Tools:

valgrind(orasan/ubsanif Valgrind is unavailable)strace/dtruss

Testing Your Setup:

$ cc --version

[compiler name/version info]

Time Investment

- Simple projects: 4-8 hours each

- Moderate projects: 10-20 hours each

- Complex projects: 20-40 hours each

- Total sprint: 2-4 months depending on background

Important Reality Check This sprint is intentionally uncomfortable. You will encounter behaviors that look like bugs but are actually allowed by the C standard. The goal is to replace guesswork with invariants and evidence.

Big Picture / Mental Model

C is a contract between source code and the compiler, not a guarantee of machine behavior. The compiler assumes you follow the rules, and when you don’t, it is free to optimize in ways that surprise you. The mental model below shows the layers you must reason about together:

C Source Rules

| (syntax + types + qualifiers)

v

Translation Units

| (preprocess, compile, assemble)

v

Linker Model

| (symbols + relocations + visibility)

v

ABI + Runtime

| (calling convention + stack/heap layout)

v

Observable Behavior

| (correctness + performance + portability)

Theory Primer

Chapter 1: Declarations, Types, and the Spiral Rule

Fundamentals

C declarations are read from the identifier outward, and the binding order is not “left to right” but a precedence-based structure that makes function pointers and arrays particularly tricky. A declaration combines type specifiers (such as int, unsigned, struct) with type constructors (pointers, arrays, function types) to build a type. The key idea is that the identifier is the core, and every surrounding operator tells you how to interpret it. Qualifiers such as const and volatile attach to the thing immediately to their right (or the left if nothing is to the right). Understanding declarations is not just academic: it is the foundation for reading APIs, dissecting system headers, and interpreting diagnostics. If you can parse a declaration, you can also design one that communicates intent clearly.

Deep Dive

The C type system is constructed by layering: base types plus type constructors. The spiral (clockwise) rule is a mnemonic for how declarators are parsed. Start at the identifier, then move right if possible, then left, honoring parentheses to override default binding. This mirrors the grammar: an abstract-declarator or declarator is built from pointer operators and direct declarators that can be arrays or function parameter lists. A common trap is assuming that const always means “constant value.” In C, const modifies the thing it directly qualifies. That means const int *p makes the pointee const (you cannot modify the int through p), while int * const p makes the pointer itself const (you cannot reassign p). This is why int const *p is equivalent to const int *p: const binds to the int, not to the pointer. Another deep rule is that function parameters are adjusted: array parameters are converted to pointers, and function parameters are converted to function pointers. This is not just a convenience; it’s an ABI detail that impacts how arguments are passed. Declarations also interact with storage class (static, extern) and linkage (internal vs external) in ways that matter for linking. If you write static at file scope, you are not making the value constant; you are restricting visibility to the translation unit. That difference shows up in symbol tables, not just semantics. Function pointer declarations encode calling signatures; if you get them wrong, you can cause undefined behavior by calling a function with mismatched types. The deeper mastery is the ability to read declaration complexity and simplify it into “noun phrases.” For example, a declaration like “char *(*fp)(int, float)” should become: “fp is a pointer to a function taking int and float, returning pointer to char.” Practicing this transforms compiler error messages into actionable clues rather than noise.

How this fits on projects You will need declaration mastery to build the cdecl clone (Project 1), interpret function pointer dispatch tables (Project 10), and reason about ABI constraints (Projects 4, 17, 18).

Definitions & key terms

- Declarator: The part of a declaration that introduces an identifier and type constructors.

- Type constructor: Pointer, array, or function type operator.

- Qualifier:

const,volatile,restrict,_Atomic. - Linkage: Visibility of identifiers across translation units.

Mental model diagram

[base type]

|

v

+-------------+

| declarator | -> identifier

+-------------+

|

+-- pointer (*)

+-- array [n]

+-- function (params)

Spiral read: start at identifier, walk outwards.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ THE CLOCKWISE/SPIRAL RULE │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ ALGORITHM: │

│ 1. Start at the identifier │

│ 2. Move clockwise/spiral outward │

│ 3. At each element, read it aloud │

│ 4. Parentheses group and redirect the spiral │

│ │

│ EXAMPLE: char *(*fp)(int, float); │

│ │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ ┌────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ ┌─────────┐ │ │ │

│ ▼ ▼ ▼ │ │ │

│ char *(* fp )(int, float) │

│ │ │ ▲ │

│ │ └───┘ │

│ └─────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ Reading: "fp is a pointer to a function(int, float) returning char*" │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

How it works (step-by-step)

- Identify the base type (e.g.,

int,struct foo). - Locate the identifier (the name being declared).

- Walk outward by precedence: parentheses override, then arrays/functions, then pointers.

- Apply qualifiers to the thing they directly bind to.

- Check storage class and linkage rules at file scope.

- Validate that the final type makes sense for its usage (e.g., function pointer signature matches call sites).

Minimal concrete example (pseudo)

Declaration: char *(*fp)(int, float)

Read: fp -> pointer -> function(int, float) -> returns pointer -> char

Common misconceptions

- “

constmakes the pointer const.” (Not always.) - “Arrays are pointers.” (They are not; they often decay.)

- “If it compiles, the signature is correct.” (Mismatched function pointer types can compile yet be UB.)

Check-your-understanding questions

- What does

int (*fptr)(void)mean compared toint *fptr(void)? - How does

constbind inchar * const *p? - Why do array parameters become pointers in function declarations?

Check-your-understanding answers

fptris a pointer to a function returningint, whereasfptris a function returning pointer toint.ppoints to a const pointer to char; the middle pointer cannot be reassigned.- The language adjusts array parameters to pointers as part of the function type rule; the array size is not part of the parameter type.

Real-world applications

- Interpreting system headers (

signal,pthread_create,qsortcallbacks) - Building pluggable interfaces with function pointers

- Understanding compiler diagnostics for complex APIs

Where you’ll apply it Projects 1, 4, 10, 17, 18

References

- “Expert C Programming” by Peter van der Linden - Ch. 3

- “The C Programming Language” by Kernighan & Ritchie - Appendix A

- “C Interfaces and Implementations” by David Hanson - Ch. 2

Key insights A declaration is a type sentence you must learn to read, not just a compiler obstacle.

Summary Once you can parse declarations mechanically, you can design clearer interfaces and debug complex C APIs quickly.

Homework/Exercises to practice the concept

- Translate 10 complex declarations into plain English and verify with a tool.

- Write three function pointer declarations for different callbacks and explain them aloud.

Solutions to the homework/exercises

- The correct reading always starts at the identifier and follows precedence outward.

- Ensure each callback’s signature matches how the function will be called.

Chapter 2: Arrays, Pointers, and Addressing Semantics

Fundamentals

Arrays and pointers are closely related but fundamentally different types. Arrays represent a fixed region of contiguous elements, while pointers hold an address that can reference such a region. Most array expressions decay into pointers to their first element, which is why array notation often “feels” like pointer notation. But decay is a conversion with rules and exceptions: it does not happen with sizeof, with unary &, or with string literal initialization. Pointer arithmetic scales by the size of the pointed-to type, which is a source of both power and bugs. Multidimensional arrays add another layer: they are arrays of arrays, and their address arithmetic depends on row-major layout. Understanding these distinctions is essential for safe indexing, correct function signatures, and memory correctness.

Deep Dive

The decay rule is a convenience for passing arrays to functions, but it hides the array’s size. When you write int a[10] at file scope or block scope, a is an object with size 10 * sizeof(int). In most expressions, a is converted to &a[0] of type int *. The conversion is automatic and invisible, which is why confusion persists. But sizeof(a) yields the size of the entire array, while sizeof(a + 0) yields the size of a pointer. This difference is a key diagnostic technique. Another subtlety is that arrays are not assignable and are not modifiable lvalues; you cannot reassign a because the array is not a pointer. When arrays appear in function parameter lists, the language adjusts the parameter type to a pointer, which is why void f(int a[10]) and void f(int *a) are the same function signature. For multidimensional arrays, only the first dimension may be omitted in function parameters; the remaining dimensions must be known so the compiler can compute the correct offsets. A int matrix[3][4] is a 3-element array of 4-element arrays; matrix decays to a pointer to a 4-element array, not a pointer to pointer. This is why int ** is not compatible with a 2D array. Pointer arithmetic relies on the element size: p + 1 advances by sizeof(*p) bytes. This scaling is what makes pointer arithmetic work naturally with typed arrays, but it also means that casting to char * (byte pointer) changes the stride. Effective mastery includes mental models for address calculation, stride, and bounds, and the discipline to avoid out-of-bounds access, which is undefined behavior.

How this fits on projects Projects 2, 8, and 9 are dedicated to exposing array/pointer differences and address scaling. The memory layout visualizer (Project 3) reinforces how contiguous storage is structured.

Definitions & key terms

- Array decay: Implicit conversion of array to pointer to its first element.

- Row-major layout: Multidimensional arrays laid out with contiguous rows.

- Pointer arithmetic: Addition/subtraction scaled by element size.

- Non-modifiable lvalue: An lvalue that cannot be assigned to (arrays).

Mental model diagram

int m[2][3]

m (array of 2) --> [ row0 ][ row1 ]

row0 (array of 3) --> [e0][e1][e2]

Address math:

& m[i][j] = base + (i * cols + j) * sizeof(int)

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ ARRAYS ARE NOT POINTERS │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ MEMORY LAYOUT: │

│ │

│ int arr[5] = {10, 20, 30, 40, 50}; │

│ int *ptr = arr; │

│ │

│ STACK: │

│ ┌───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ arr: │ 10 │ 20 │ 30 │ 40 │ 50 │ (20 bytes on 32-bit) │ │

│ │ └─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┘ │ │

│ │ ▲ │ │

│ │ │ │ │

│ │ ptr: └───────────────────────────────── (4/8 bytes for pointer) │ │

│ └───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ CRITICAL: arr IS the memory; ptr POINTS TO memory. │

│ │

│ WHEN ARRAYS DECAY: WHEN ARRAYS DO NOT DECAY: │

│ ✓ Function parameters ✗ With sizeof │

│ ✓ In expressions ✗ With & (address-of) │

│ ✓ Most operators ✗ String literal initializers │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

How it works (step-by-step)

- Determine the true type of the array expression (array vs pointer).

- Identify whether decay applies in that context.

- For pointer arithmetic, compute stride = sizeof(element).

- For multidimensional arrays, compute offsets using row-major rules.

- Validate bounds: any access outside

[0, size)is undefined.

Minimal concrete example (pseudo)

If a is int[4], then:

- sizeof(a) == 4 * sizeof(int)

- sizeof(a + 0) == sizeof(int*)

- a + 1 points to element index 1

Common misconceptions

- “Arrays are pointers.” (They are not.)

- “

int **can replace any 2D array.” (It cannot.) - “Pointer arithmetic is always byte-based.” (It is scaled by element size.)

Check-your-understanding questions

- Why does

sizeof(a)differ inside and outside a function? - What type does a 2D array decay to?

- Why can you not reassign an array variable?

Check-your-understanding answers

- Inside a function, the parameter has already decayed to a pointer, losing size info.

- It decays to a pointer to its first row (an array of the inner dimension).

- Arrays are not assignable; the array name denotes a fixed storage location.

Real-world applications

- Correctly declaring function parameters for arrays

- Building memory-safe indexing logic

- Interfacing with C libraries that use array sizes explicitly

Where you’ll apply it Projects 2, 8, 9, 13

References

- “Expert C Programming” by Peter van der Linden - Ch. 4

- “Understanding and Using C Pointers” by Richard Reese - Ch. 2-4

- “The C Programming Language” by Kernighan & Ritchie - Ch. 5

Key insights Arrays are storage; pointers are addresses; decay is a conversion, not an identity.

Summary When you separate “object” from “address,” pointer arithmetic and function signatures become predictable.

Homework/Exercises to practice the concept

- Write a table of array expressions and label whether decay occurs.

- Draw the memory layout of a 3x4 array and compute three addresses by hand.

Solutions to the homework/exercises

- Decay occurs in most expressions except

sizeof,&, and string literal initialization. - Address math follows

base + (row * cols + col) * sizeof(elem).

Chapter 3: Storage Duration, Object Lifetime, and Memory Layout

Fundamentals C programs use multiple storage regions: text (code), read-only data (literals), initialized data, BSS (zeroed globals), heap (dynamic allocation), and stack (automatic storage). Each object has a storage duration (static, automatic, allocated), a lifetime (when it is valid), and a representation (bytes and alignment). Understanding where objects live explains why returning a pointer to a local variable is invalid, why string literals should be treated as read-only, and why alignment and padding affect structure sizes. This foundation is required for debugging memory issues and for reasoning about performance.

Deep Dive

Memory layout is both an ABI convention and an OS policy. The typical process layout places code (text) at low addresses, then read-only data, initialized data, BSS, heap growing upward, and stack growing downward. This is not guaranteed by the C standard, but it is a stable practical model on modern systems. Storage duration explains lifetime: automatic objects are valid only within their scope; static objects live for the entire program; allocated objects live until they are freed. Errors like use-after-free, double-free, and stack-use-after-return are violations of lifetime. Object representation also matters: alignment rules require certain addresses for types, leading to padding within structs. This padding is why struct sizes often exceed the sum of their fields. Endianness determines byte order inside multi-byte objects; it affects serialization, networking, and interpreting raw bytes. String literals are typically stored in a read-only segment; modifying them is undefined behavior even if it “seems to work” on a particular build. Finally, the heap is managed by an allocator that may keep freed blocks, reuse them, or split/coalesce them, which is why memory debugging requires both logical reasoning and tooling. If you can map an object to its storage region and its lifetime, you can predict the kinds of bugs that are possible at that location.

How this fits on projects Projects 3 and 14 focus on memory layout and allocation behavior. Project 15 reveals alignment and padding. Project 13 builds safe string interfaces that respect object lifetimes.

Definitions & key terms

- Storage duration: How long an object exists (static, automatic, allocated).

- Lifetime: The period when an object is valid to access.

- Alignment: Required address multiples for a type.

- Padding: Extra bytes inserted to satisfy alignment.

- BSS: Segment for zero-initialized globals.

Mental model diagram

High Address

+-------------------+ Stack (automatic, grows down)

| local vars |

+-------------------+

| unmapped gap |

+-------------------+ Heap (allocated, grows up)

| malloc blocks |

+-------------------+

| BSS (zeroed) |

+-------------------+

| DATA (init) |

+-------------------+

| RODATA |

+-------------------+

| TEXT (code) |

+-------------------+

Low Address

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ PROCESS MEMORY LAYOUT │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ HIGH ADDRESS │

│ ┌───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ STACK │ │

│ │ • Local variables, function parameters │ │

│ │ • Grows DOWNWARD ↓ │ │

│ ├ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ┤ │

│ │ [ unmapped gap ] │ │

│ ├ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ┤ │

│ │ HEAP │ │

│ │ • malloc, calloc, realloc │ │

│ │ • Grows UPWARD ↑ │ │

│ ├───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ BSS │ │

│ │ • Uninitialized globals (zeroed) │ │

│ ├───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ DATA │ │

│ │ • Initialized globals │ │

│ ├───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ RODATA │ │

│ │ • String literals, const globals │ │

│ ├───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ TEXT │ │

│ │ • Executable code │ │

│ └───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ LOW ADDRESS │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

How it works (step-by-step)

- Identify storage duration from declaration and allocation method.

- Determine object lifetime boundaries (scope exit, free, program end).

- Check alignment requirements for each type.

- Compute struct layout: field order, padding, total size.

- Map objects to their segment and reason about access safety.

Minimal concrete example (pseudo)

Object: local array -> automatic storage -> stack

Object: global const string -> static storage -> rodata

Object: malloc buffer -> allocated storage -> heap

Common misconceptions

- “Heap memory is always zeroed.” (It is not.)

- “String literals are modifiable.” (They are not.)

- “Struct size equals sum of fields.” (Padding exists.)

Check-your-understanding questions

- Why is returning the address of a local variable undefined behavior?

- Why can adding a

charfield increase struct size by more than 1 byte? - What happens if you access memory after

free?

Check-your-understanding answers

- The object’s lifetime ends at scope exit; the address becomes invalid.

- Alignment forces padding to satisfy the next field’s alignment.

- The memory no longer belongs to the object; access is undefined.

Real-world applications

- Debugging memory corruption and leaks

- Designing ABI-stable structs

- Building safe allocation patterns and string handling

Where you’ll apply it Projects 3, 14, 15, 13, 18

References

- “Expert C Programming” by Peter van der Linden - Ch. 6

- “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” - Ch. 6-9

- “Effective C” by Robert Seacord - Ch. 5

Key insights If you can explain where an object lives and when it dies, you can predict most memory bugs.

Summary Memory layout is predictable once you account for storage duration, alignment, and lifetime.

Homework/Exercises to practice the concept

- Diagram where globals, locals, literals, and heap allocations live.

- Compute struct sizes with different field orders.

Solutions to the homework/exercises

- Globals and literals live in static segments; locals live on the stack; heap allocations live on the heap.

- Reordering fields to reduce padding can shrink struct size.

Chapter 4: Translation Pipeline (Preprocessor to Linker)

Fundamentals C source code is not what the compiler directly processes. The program passes through preprocessing (macro expansion and include handling), compilation (translation to an intermediate representation), assembly (machine code generation), and linking (resolving symbols into a final binary). The preprocessor is a text-substitution engine with its own rules for tokenization and expansion. The linker is a symbol resolver with strict rules for visibility and duplication. Mastery requires understanding each stage so that you can reason about errors that appear long after your source file seems correct.

Deep Dive

The translation phases defined by the C standard include tokenization, preprocessing, compilation, and linking. The preprocessor expands macros, includes header files, and performs conditional compilation. It operates on tokens, not characters, which is why #define expansions can behave unexpectedly if you do not respect macro boundaries. Include guards and #pragma once prevent duplicate header content. After preprocessing, each translation unit is compiled independently. The compiler creates object files containing machine code, data, and symbol tables. At this stage, references to external symbols are unresolved. The assembler converts compiler output into object files with relocation entries. Finally, the linker combines object files and libraries, resolves external symbols, and creates the executable or shared object. Errors like “undefined reference” or “multiple definition” are link-time errors, not compile-time errors. Understanding this pipeline clarifies why a header should declare but not define most global objects, and why a static function in a .c file is invisible to other translation units. It also explains why macro-based code generation can be powerful but dangerous: the compiler does not see the macro intent, only its expansion. Tooling like -E (preprocess only), -S (assembly output), and -c (compile to object) lets you inspect each stage. A deep understanding of the pipeline turns “mysterious” build issues into predictable, solvable problems.

How this fits on projects Projects 11, 6, and 7 focus on preprocessor output, symbol tables, and linker errors. Project 18 reveals how high-level constructs map into assembly.

Definitions & key terms

- Translation unit: A preprocessed source file plus its includes.

- Object file: Compiled machine code plus symbols and relocations.

- Relocation: Metadata telling the linker how to fix addresses.

- Include guard: Mechanism preventing multiple inclusion of headers.

Mental model diagram

source.c

|

v

[Preprocessor] -> source.i

|

v

[Compiler] -> source.s

|

v

[Assembler] -> source.o

|

v

[Linker] -> executable / shared lib

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ THE LINKING PROCESS │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ main.c math.c │

│ ──────── ──────── │

│ extern int add(int, int); int add(int a, int b) { │

│ int main() { return a + b; │

│ return add(3, 4); } │

│ } │

│ │ │ │

│ ▼ ▼ │

│ main.o math.o │

│ ┌────────────────────┐ ┌────────────────────┐ │

│ │ DEFINED: main │ │ DEFINED: add │ │

│ │ UNDEFINED: add │◄────────────►│ │ │

│ └────────────────────┘ └────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ LINKER RESOLVES │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌─────────────────┐ │

│ │ EXECUTABLE │ │

│ │ main → add │ │

│ └─────────────────┘ │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

How it works (step-by-step)

- Preprocessor expands macros and includes to produce a translation unit.

- Compiler parses and optimizes into machine instructions.

- Assembler emits object files with symbol and relocation tables.

- Linker resolves symbols, merges sections, and produces the final binary.

- Loader maps the binary and resolves dynamic symbols at runtime (for shared libs).

Minimal concrete example (pseudo)

$ cc -E file.c -> file.i (expanded macros)

$ cc -S file.c -> file.s (assembly)

$ cc -c file.c -> file.o (object)

$ cc file.o -o app

Common misconceptions

- “The compiler sees my macros.” (It only sees expansions.)

- “Linker errors mean compilation failed.” (Different stage.)

- “Headers are compiled.” (Headers are included into translation units.)

Check-your-understanding questions

- Why does a definition in a header often cause multiple-definition errors?

- What is the difference between

-cand-S? - Why do link errors appear even when compilation succeeded?

Check-your-understanding answers

- Every translation unit gets its own copy of that definition.

-cproduces an object file;-Sproduces assembly output.- The linker is resolving cross-file references that the compiler cannot see.

Real-world applications

- Diagnosing build system failures

- Understanding why macros can break tooling

- Writing portable headers and libraries

Where you’ll apply it Projects 6, 7, 11, 18

References

- “Expert C Programming” by Peter van der Linden - Ch. 5

- “Linkers and Loaders” by John Levine - Ch. 1-3

- GCC/Clang documentation (compiler phases)

Key insights Most “C bugs” in large systems are actually translation or linking misunderstandings.

Summary When you can isolate which phase caused the issue, you can fix it with far less trial and error.

Homework/Exercises to practice the concept

- Build a small program using

-E,-S, and-cand inspect each output. - Trigger one undefined-reference error and explain why it happens.

Solutions to the homework/exercises

- The preprocessed output shows macro expansion; the assembly reveals instruction selection; the object file shows symbol tables.

- Undefined references occur when the linker cannot find a definition for a declared symbol.

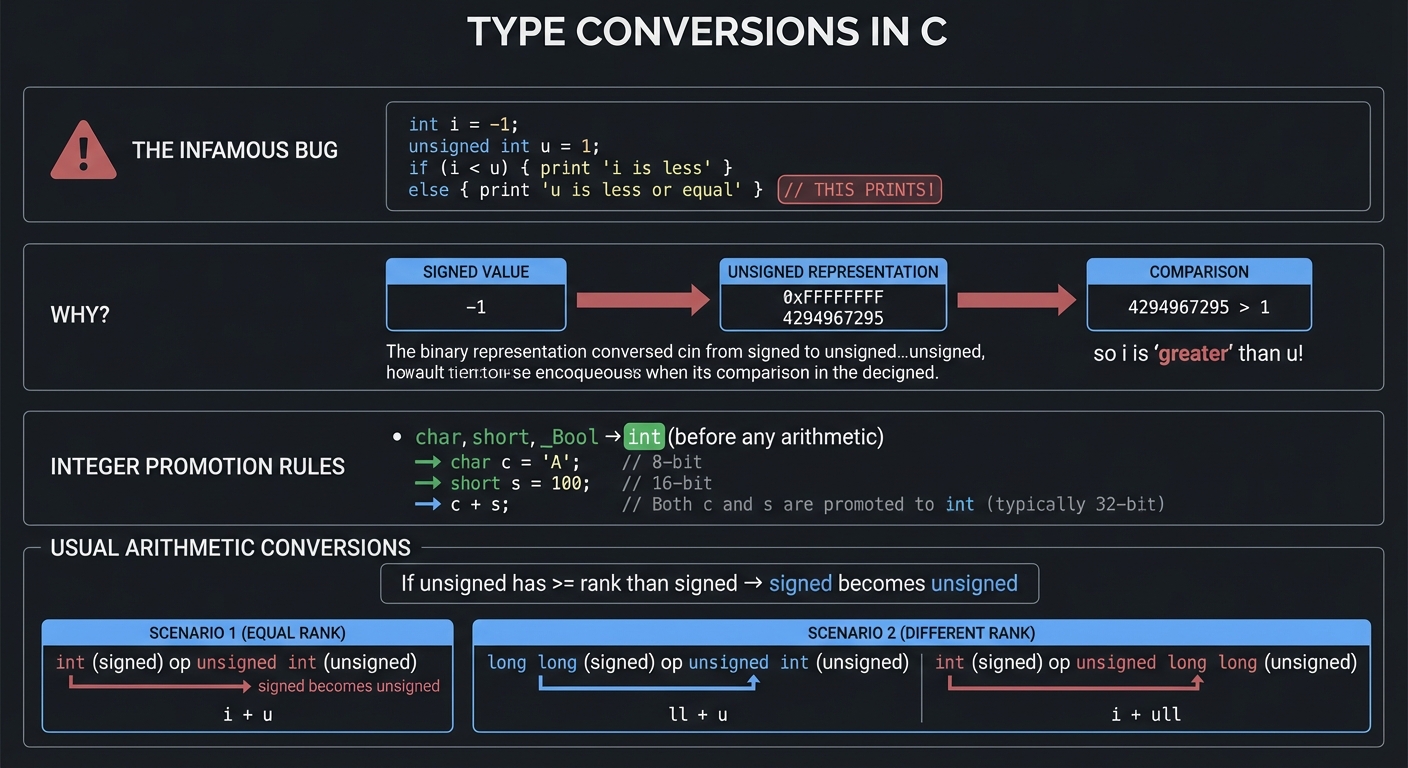

Chapter 5: Integer Conversions and Representation

Fundamentals

C silently converts values in many contexts, especially when mixing signed and unsigned integers or smaller integer types. The “usual arithmetic conversions” rule determines the common type for operations. Integer promotions happen first: char and short become int (or unsigned int) before arithmetic. Signedness matters because conversions can change the numerical value, not just its representation. Understanding these rules prevents logic bugs and security vulnerabilities.

Deep Dive

Every integer operation in C is governed by a precise conversion ladder. Integer promotions raise smaller types to int or unsigned int before any arithmetic, which affects comparisons and bitwise operations. The usual arithmetic conversions then choose a common type for both operands. If one operand is unsigned and has rank greater than or equal to the signed operand, the signed value is converted to unsigned, which can produce large positive values for what you thought were negatives. This is the root cause of classic bugs like if (i < u) when i is negative and u is unsigned. Overflow is another trap: signed overflow is undefined behavior, while unsigned overflow wraps modulo 2^N. That difference impacts optimization and correctness. Representations (two’s complement, ones’ complement, sign-magnitude) are mostly standardized today as two’s complement, but the C standard still permits others, which matters for portability. Bitwise operations on signed types can also lead to implementation-defined or undefined results. The correct approach is to use explicit types (uint32_t, int32_t) when you need defined widths, and to be explicit about conversions. Tooling like -Wsign-compare and -Wconversion helps surface issues, and sanitizers can catch undefined behavior involving signed overflow.

How this fits on projects Project 5 is a dedicated type-promotion lab. Projects 12 and 16 depend on understanding integer edge cases and UB.

Definitions & key terms

- Integer promotion: Automatic conversion of smaller integer types to

int/unsigned int. - Usual arithmetic conversions: Rules that choose a common type for binary operators.

- Signed overflow: Undefined behavior in C.

- Unsigned wraparound: Well-defined modulo arithmetic.

Mental model diagram

small ints -> int/unsigned int (promote)

-> choose common type (rank + signedness)

-> perform operation

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ TYPE CONVERSIONS IN C │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ THE INFAMOUS BUG: │

│ ──────────────── │

│ int i = -1; │

│ unsigned int u = 1; │

│ if (i < u) { │

│ printf(\"i is less\\n\"); │

│ } else { │

│ printf(\"u is less or equal\\n\"); // THIS PRINTS! │

│ } │

│ │

│ WHY? -1 is converted to unsigned: │

│ -1 (signed) → 0xFFFFFFFF (unsigned) → 4294967295 │

│ 4294967295 > 1, so i is \"greater\" than u! │

│ │

│ INTEGER PROMOTION RULES: │

│ ──────────────────────── │

│ char, short, _Bool → int (before any arithmetic) │

│ │

│ USUAL ARITHMETIC CONVERSIONS: │

│ ───────────────────────────── │

│ If unsigned has >= rank than signed → signed becomes unsigned │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

How it works (step-by-step)

- Apply integer promotions to operands.

- Determine the “rank” and signedness of each operand.

- Convert to a common type using the usual arithmetic conversions.

- Perform the operation in that common type.

- Apply result type and conversion back if needed.

Minimal concrete example (pseudo)

signed i = -1

unsigned u = 1

Comparison uses unsigned -> i becomes large positive -> i < u is false

Common misconceptions

- “Signed overflow wraps like unsigned.” (It does not.)

- “

charis always signed.” (It can be signed or unsigned.) - “Comparisons are safe if types look similar.” (Conversions happen silently.)

Check-your-understanding questions

- Why can

-1 < 1ube false? - Why is

chardangerous in arithmetic? - What is the difference between signed and unsigned overflow?

Check-your-understanding answers

- The signed value is converted to unsigned before comparison.

- It is promoted to

int(signedness depends on implementation) which changes behavior. - Signed overflow is UB; unsigned overflow wraps modulo 2^N.

Real-world applications

- Preventing integer-based security bugs

- Designing safe APIs that avoid surprising conversions

- Writing portable numeric code

Where you’ll apply it Projects 5, 12, 16

References

- “Expert C Programming” by Peter van der Linden - Ch. 2

- “Effective C” by Robert Seacord - Ch. 3

- ISO/IEC 9899 (C standard) - Integer conversions

Key insights C does not warn you when it changes your values; you must know when it happens.

Summary Conversions are a hidden execution layer; once you see them, many bugs disappear.

Homework/Exercises to practice the concept

- Write a table of 10 mixed signed/unsigned expressions and predict results.

- Identify where promotions occur in a small arithmetic expression chain.

Solutions to the homework/exercises

- Apply integer promotion first, then usual arithmetic conversions.

- Use explicit casts or fixed-width types to control conversions.

Chapter 6: Undefined Behavior, Aliasing, and Portability

Fundamentals Undefined behavior (UB) is the set of actions for which the C standard imposes no requirements. That means the compiler can assume UB never happens and optimize accordingly. UB is not just “crash” or “random behavior”; it is permission for the compiler to make transformations that break your assumptions. Common sources include out-of-bounds access, use-after-free, signed overflow, and strict aliasing violations. Portability requires avoiding UB and implementation-defined assumptions such as integer sizes and endianness.

Deep Dive

UB is central to expert C. The compiler’s job is to generate correct code for well-defined programs. If you violate a rule, the compiler is allowed to optimize in ways that produce unexpected results. For example, if the compiler can prove that a signed integer cannot overflow in a well-defined program, it can remove overflow checks or reorder code. That means that even if the program “seems to work” with one compiler or optimization level, it may fail elsewhere. Strict aliasing is another major pitfall: the compiler assumes that pointers of different types do not refer to the same memory (with some exceptions). If you violate this by type-punning through incompatible pointers, the compiler may reorder or eliminate loads, producing surprising results. Sequencing rules (formerly “sequence points”) determine when side effects are applied; expressions like i = i++ or a[i] = i++ have undefined or unspecified behavior. Portability also includes assumptions about sizeof(int), struct layout, and endianness. Expert C code isolates machine-specific behavior behind explicit checks or uses fixed-width types and well-defined conversions. The deeper skill is to reason about invariants: “This pointer always points to a valid object,” “This index is always in bounds,” “This object is accessed only through its effective type.” Tools like sanitizers and static analyzers help, but they are not a substitute for understanding the rules that define correctness.

How this fits on projects Project 12 catalogs UB patterns. Project 16 builds a portability checker. Project 14’s memory debugger highlights lifetime and bounds violations.

Definitions & key terms

- Undefined behavior: No requirements on the result.

- Unspecified behavior: One of several possibilities, not documented which.

- Implementation-defined behavior: Defined by the compiler, may vary.

- Strict aliasing: Rules about accessing objects through different types.

Mental model diagram

Well-defined program

-> compiler guarantees correct behavior

UB occurs

-> compiler free to assume UB never happens

-> surprising optimizations possible

How it works (step-by-step)

- Identify potential UB sources (bounds, lifetime, overflow, aliasing).

- Replace assumptions with explicit checks or well-defined constructs.

- Use fixed-width types and clear conversions for portability.

- Validate with sanitizers and cross-compiler builds.

Minimal concrete example (pseudo)

if (x + 1 > x) // always true for defined signed arithmetic

// but if x can overflow, compiler may treat this as always true

Common misconceptions

- “UB means it will just crash.” (It can silently corrupt or be optimized away.)

- “If it works with -O0, it will work with -O2.” (UB breaks that assumption.)

- “Type-punning is safe if I know what I’m doing.” (Not under strict aliasing.)

Check-your-understanding questions

- Why can a compiler remove bounds checks?

- What is the difference between unspecified and undefined behavior?

- Why does strict aliasing matter for optimization?

Check-your-understanding answers

- If UB would occur, the compiler can assume it does not and optimize away checks.

- Unspecified behavior is one of several allowed results; UB has no requirements.

- The compiler assumes different types do not alias, enabling reordering.

Real-world applications

- Hardening C code against compiler and platform differences

- Debugging “Heisenbugs” that disappear under the debugger

- Writing portable libraries for multiple architectures

Where you’ll apply it Projects 12, 14, 16, 18

References

- “Effective C” by Robert Seacord - Ch. 2, 4

- “Expert C Programming” by Peter van der Linden - Ch. 1

- ISO/IEC 9899 (C standard) - Behavior categories

Key insights Undefined behavior is not a corner case; it is the lever compilers use for optimization.

Summary Portable, reliable C is mostly about eliminating UB and making assumptions explicit.

Homework/Exercises to practice the concept

- Identify 10 common UB patterns and explain why they are UB.

- Compile the same program with different optimization levels and compare behavior.

Solutions to the homework/exercises

- Focus on bounds, lifetime, overflow, and aliasing rules.

- Differences across optimization levels often indicate UB.

Chapter 7: ABI, Calling Conventions, and Stack Frames

Fundamentals The ABI (Application Binary Interface) defines how functions are called, how parameters are passed, how return values are delivered, and how the stack is organized. Calling conventions specify which registers are used for arguments, which must be preserved, and where local variables live. A stack frame is the runtime structure that stores return addresses, saved registers, and locals. Without this knowledge, debugging crashes or interfacing with assembly is guesswork.

Deep Dive At runtime, a function call is a contract between caller and callee: which registers contain arguments, who saves which registers, how the stack pointer is aligned, and where the return value is placed. On x86-64 System V, the first integer arguments are passed in specific registers, floating-point arguments in XMM registers, and the stack is aligned to 16 bytes before a call. The caller saves volatile registers; the callee saves non-volatile ones. Variadic functions add complexity: the caller must place arguments in both registers and a home area so the callee can walk them. Stack frames typically include a return address, saved base pointer (optional), and space for locals and spilled registers. Optimizing compilers can omit frame pointers, reorder locals, and allocate variables in registers instead of the stack, which changes what you see in a debugger. Understanding the ABI lets you interpret backtraces, unwind stacks, and diagnose mis-matched function signatures. It also explains why calling a function through a pointer of the wrong type can corrupt registers or stack state.

How this fits on projects Project 4 inspects stack frames. Project 17 visualizes calling conventions. Project 18 maps C constructs to assembly and ABI conventions.

Definitions & key terms

- ABI: Binary interface between compiled units.

- Calling convention: Rules for argument passing and register preservation.

- Stack frame: Per-call stack region with metadata and locals.

- Callee-saved registers: Registers the callee must preserve.

Mental model diagram

Caller

| places args in registers/stack

v

Call instruction -> pushes return address

v

Callee

| saves non-volatile registers

| allocates locals on stack

| executes

| restores registers and returns

How it works (step-by-step)

- Caller loads arguments into ABI-specified registers/stack slots.

- Call instruction transfers control and saves return address.

- Callee sets up stack frame (optional frame pointer).

- Function executes and stores return value in ABI-defined location.

- Callee restores state and returns to caller.

Minimal concrete example (pseudo)

Call f(a,b):

- a -> register R1

- b -> register R2

- call f

- return value -> register R0

Common misconceptions

- “The stack always looks the same.” (Optimizations change it.)

- “Any function pointer call is safe.” (Signature mismatches break ABI.)

- “The debugger shows all locals.” (Optimized builds may omit them.)

Check-your-understanding questions

- Why do variadic functions need special handling?

- What happens if a callee fails to restore a non-volatile register?

- Why might a backtrace be incorrect in optimized code?

Check-your-understanding answers

- The callee must access arguments whose locations are not fixed at compile time.

- The caller’s expected state is corrupted, leading to undefined behavior.

- The compiler may omit frame pointers or rearrange stack usage.

Real-world applications

- Debugging crashes with stack traces

- Writing language bindings and FFI layers

- Reading assembly generated by the compiler

Where you’ll apply it Projects 4, 17, 18

References

- System V AMD64 ABI documentation

- “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” - Ch. 3

- “Expert C Programming” by Peter van der Linden - Ch. 7

Key insights ABI rules are the “physics” of C binaries; ignore them and everything breaks.

Summary Stack frames and calling conventions are predictable once you know the ABI contract.

Homework/Exercises to practice the concept

- Read a simple function’s assembly and identify argument locations.

- Compare stack traces from debug vs optimized builds.

Solutions to the homework/exercises

- Use ABI docs to map register usage.

- Expect locals to disappear or move under optimization.

Glossary

- ABI: Binary-level contract for calling and linking compiled code.

- Array decay: Implicit conversion of array to pointer to first element.

- BSS: Memory segment for zero-initialized global variables.

- Declarator: The portion of a declaration that defines the identifier’s type.

- Linker: Tool that resolves symbols and produces executables or libraries.

- Relocation: Link-time fixups that patch addresses.

- Storage duration: The lifetime category of an object.

- Undefined behavior: Actions with no requirements in the C standard.

Why Expert C Programming Matters

- Modern motivation: C powers operating systems, runtimes, and embedded systems; deep C knowledge translates into reliability and performance where abstractions leak.

- Real-world impact (stats):

- The Linux kernel is overwhelmingly C, with Open Hub reporting ~35.9M C code lines out of ~37.3M total code lines as of Dec 2025. (Source: Open Hub, Dec 2025, https://www.openhub.net/p/linux/analyses/latest/languages_summary)

- SQLite states there are over 1 trillion SQLite databases in active use and that SQLite is the most used database engine in the world. (Source: sqlite.org, 2025, https://www.sqlite.org/mostdeployed.html ; https://www.sqlite.org/facts.html)

- The TIOBE Index for Dec 2025 ranks C as #2 in popularity with ~10.11% rating. (Source: TIOBE Index, Dec 2025, https://www.tiobe.com/tiobe-index/)

- Context & evolution: C’s core model (manual memory, explicit types, translation units) has remained stable while compilers, hardware, and security constraints have advanced.

Old vs new mental model

Old mental model: "C is close to the machine, so it will do what I mean."

New mental model: "C is a contract; the compiler assumes I follow it."

Why Expert C Remains Essential

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ WHY EXPERT C REMAINS ESSENTIAL │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ WHAT CHANGED: │

│ ───────────── │

│ • 64-bit is now standard (book was written for 32-bit) │

│ • C99/C11/C17/C23 added features (VLAs, _Bool, _Generic, etc.) │

│ • Compilers are smarter (more aggressive optimization) │

│ • Security focus increased (stack canaries, ASLR, etc.) │

│ │

│ WHAT STAYED THE SAME: │

│ ───────────────────── │

│ • Declaration syntax (still confusing, still the same rules) │

│ • Array/pointer relationship (fundamental to the language) │

│ • Linking model (still symbol tables and relocations) │

│ • Type conversion rules (still the "usual arithmetic conversions") │

│ • Undefined behavior (still undefined, still exploited by compilers) │

│ • Memory layout (text, data, bss, heap, stack) │

│ │

│ MODERN APPLICATIONS STILL WRITTEN IN C: │

│ ──────────────────────────────────────── │

│ Linux kernel .............. 30+ million lines of C │

│ SQLite .................... Most deployed database (pure C) │

│ CPython ................... Python's reference implementation │

│ Redis ..................... High-performance cache │

│ Git ....................... Version control everywhere │

│ curl ...................... "The glue of the internet" │

│ OpenSSL ................... Security for the web │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Concept Summary Table

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize |

|---|---|

| Declarations & Type System | How C builds types from declarators, qualifiers, and function/array constructors. |

| Arrays, Pointers, Addressing | When arrays decay, how pointer arithmetic scales, and why int** is not a 2D array. |

| Storage Duration & Memory Layout | Object lifetime, segments, alignment, and struct padding. |

| Translation Pipeline & Linking | Preprocessing, compilation, object files, and symbol resolution. |

| Integer Conversions & Representation | Promotions, usual arithmetic conversions, and overflow behavior. |

| Undefined Behavior & Portability | UB categories, strict aliasing, and portability constraints. |

| ABI & Calling Conventions | Register/stack rules, frame layout, and call mechanics. |

Project-to-Concept Map

| Project | Concepts Applied |

|---|---|

| Project 1 | Declarations & Type System, Translation Pipeline & Linking |

| Project 2 | Arrays, Pointers, Addressing |

| Project 3 | Storage Duration & Memory Layout |

| Project 4 | ABI & Calling Conventions, Storage Duration & Memory Layout |

| Project 5 | Integer Conversions & Representation |

| Project 6 | Translation Pipeline & Linking |

| Project 7 | Translation Pipeline & Linking |

| Project 8 | Arrays, Pointers, Addressing |

| Project 9 | Arrays, Pointers, Addressing |

| Project 10 | Declarations & Type System, ABI & Calling Conventions |

| Project 11 | Translation Pipeline & Linking |

| Project 12 | Undefined Behavior & Portability |

| Project 13 | Storage Duration & Memory Layout, Undefined Behavior & Portability |

| Project 14 | Storage Duration & Memory Layout, Undefined Behavior & Portability |

| Project 15 | Storage Duration & Memory Layout |

| Project 16 | Undefined Behavior & Portability |

| Project 17 | ABI & Calling Conventions |

| Project 18 | Translation Pipeline & Linking, ABI & Calling Conventions |

Deep Dive Reading by Concept

| Concept | Book and Chapter | Why This Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Declarations & Type System | “Expert C Programming” - Ch. 3 | Master complex declarators and qualifiers. |

| Arrays, Pointers, Addressing | “Expert C Programming” - Ch. 4 | Understand decay and pointer arithmetic. |

| Storage Duration & Memory Layout | “Expert C Programming” - Ch. 6 | Ground truth for lifetime and memory bugs. |

| Translation Pipeline & Linking | “Linkers and Loaders” - Ch. 1-3 | Linker model and symbol resolution. |

| Integer Conversions & Representation | “Effective C” - Ch. 3 | Prevent silent conversion bugs. |

| Undefined Behavior & Portability | “Effective C” - Ch. 2,4 | Write portable, optimizer-safe C. |

| ABI & Calling Conventions | CS:APP - Ch. 3 | Connect C calls to assembly and ABI. |

Quick Start: Your First 48 Hours

Day 1:

- Read Theory Primer Chapters 1-3.

- Start Project 1 and get basic parsing output working.

Day 2:

- Validate Project 1 against its Definition of Done.

- Run Project 2’s tests and record your observations.

- Skim Chapters 4 and 5 to prepare for linker and conversion projects.

Recommended Learning Paths

Path 1: The Systems Builder

- Project 1 -> 3 -> 4 -> 6 -> 7 -> 14 -> 17 -> 18

Path 2: The Debugging Specialist

- Project 3 -> 5 -> 12 -> 14 -> 16 -> 18

Path 3: The C Interview Prepper

- Project 1 -> 2 -> 5 -> 12 -> 15 -> 17

Success Metrics

- You can predict pointer arithmetic results and explain them without running code.

- You can diagnose linker errors by reading symbol tables.

- You can explain why a snippet is undefined behavior and how to fix it.

- You can read compiler-generated assembly and explain the calling convention.

Debugging and Tooling Cheat Sheet

| Tool | Purpose | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|

nm |

Symbol inspection | Find defined/undefined symbols in object files |

objdump -t |

Symbol table dump | Inspect symbols and sections |

readelf |

ELF introspection | Check relocation entries and sections |

-E/-S/-c |

Compiler phases | Inspect preprocessing/assembly/object outputs |

asan/ubsan |

Runtime checks | Catch memory and UB bugs quickly |

Project Overview Table

| # | Project | Difficulty | Time | Primary Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C Declaration Parser | 3 | 8-12h | English translation of any declaration |

| 2 | Arrays vs Pointers Lab | 2 | 4-6h | Empirical proof of decay rules |

| 3 | Memory Layout Visualizer | 3 | 10-15h | Runtime memory map of a process |

| 4 | Stack Frame Inspector | 4 | 15-20h | Visualized call stack frames |

| 5 | Type Promotion Tester | 2 | 6-8h | Interactive conversion demos |

| 6 | Symbol Table Analyzer | 4 | 15-25h | Symbol table and relocation report |

| 7 | Linker Error Simulator | 3 | 8-12h | Catalog of linker failures |

| 8 | Multi-dim Array Navigator | 3 | 10-12h | Row-major memory visualization |

| 9 | Pointer Arithmetic Visualizer | 3 | 8-12h | Pointer stride and bounds map |

| 10 | Function Pointer Dispatch | 3 | 8-12h | Command dispatcher with callbacks |

| 11 | Preprocessor Output Analyzer | 3 | 10-15h | Macro expansion report |

| 12 | Bug Catalog (Language Features) | 3 | 10-15h | Documented UB/edge case compendium |

| 13 | Safe String Library | 4 | 20-30h | Safe string API with tests |

| 14 | Memory Debugger (Mini-Valgrind) | 5 | 30-40h | Leak/overflow detector |

| 15 | Struct Packing Analyzer | 3 | 10-15h | Layout and padding analyzer |

| 16 | Portable Code Checker | 4 | 20-30h | Portability and UB checks |

| 17 | Calling Convention Visualizer | 4 | 20-30h | ABI register/stack trace viewer |

| 18 | C to Assembly Translator | 4 | 20-30h | Annotated C->ASM mapping |

Project List

The following projects guide you from declaration mastery to ABI-level understanding.

Project 1: Build a C Declaration Parser (cdecl clone)

- File: project_based_ideas/SYSTEMS_PROGRAMMING/EXPERT_C_PROGRAMMING_DEEP_DIVE/P01-c-declaration-parser.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, C++, Zig

- Coolness Level: See REFERENCE.md

- Business Potential: See REFERENCE.md

- Difficulty: See REFERENCE.md

- Knowledge Area: Parsing, C Type System

- Software or Tool: cdecl-style parser

- Main Book: “Expert C Programming” by Peter van der Linden

What you will build: A CLI tool that turns any C declaration into a clear English description.

Why it teaches Expert C: It forces you to model the grammar and precedence rules the compiler uses.

Core challenges you will face:

- Parsing declarators -> Declarations & Type System

- Handling nested parentheses -> Declarations & Type System

- Reporting readable output -> Translation Pipeline & Linking

Real World Outcome

You can pass a declaration string and get a deterministic English explanation.

$ ./cdecl "char *(*fp)(int, float)"

fp is a pointer to a function taking (int, float) returning pointer to char

$ ./cdecl "void (*signal(int, void (*)(int)))(int)"

signal is a function taking (int, pointer to function(int)) returning pointer to function(int)

The Core Question You Are Answering

“How do C declarations encode type meaning, and how can I parse them reliably?”

This question matters because misreading declarations leads to mismatched function signatures and subtle ABI bugs.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Declarators and precedence

- How do arrays, functions, and pointers bind?

- Book Reference: “Expert C Programming” - Ch. 3

- Type qualifiers

- Where does

constbind and why? - Book Reference: K&R - Appendix A

- Where does

- Function pointers

- Why do signatures matter for ABI?

- Book Reference: CS:APP - Ch. 3

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Grammar Design

- What minimal grammar handles pointers, arrays, and functions?

- How will you represent nested declarators internally?

- Output Design

- How will you generate readable English without ambiguity?

- How will you format parameter lists?

Thinking Exercise

Declarator Walkthrough

Manually parse these declarations and explain them aloud:

char *(*(*x)(void))[5]const char * const *ppint (*(*callbacks[10])(int))(void)

Questions to answer:

- Where do parentheses change binding?

- Which part is the identifier?

The Interview Questions They Will Ask

- “Explain the difference between

int *p[10]andint (*p)[10].” - “How would you parse a declaration in a compiler?”

- “What is the spiral rule and when does it fail?”

- “Why is

constplacement so confusing in C?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Starting Point Start at the identifier and build outward using a stack of modifiers.

Hint 2: Next Level Treat arrays and functions as higher-precedence than pointers.

Hint 3: Technical Details Represent the declarator as a sequence of tokens and reduce it with a small grammar.

Hint 4: Tools/Debugging

Compare your output to cdecl or cdecl.org for validation.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Declaration syntax | “Expert C Programming” | Ch. 3 |

| C grammar | K&R | Appendix A |

Common Pitfalls and Debugging

Problem 1: “Parentheses are ignored”

- Why: Your parser treats parentheses as tokens, not grouping operators.

- Fix: Build a parse tree that preserves nesting.

- Quick test: Parse a declaration with nested parentheses and compare outputs.

Definition of Done

- Any declaration from the test suite is translated correctly

- Nested parentheses are handled without ambiguity

- Output format is human-readable and consistent

- Behavior matches at least one known cdecl tool

Project 2: Prove Arrays and Pointers Are Different

- File: project_based_ideas/SYSTEMS_PROGRAMMING/EXPERT_C_PROGRAMMING_DEEP_DIVE/P02-arrays-vs-pointers.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: C++, Zig, Rust

- Coolness Level: See REFERENCE.md

- Business Potential: See REFERENCE.md

- Difficulty: See REFERENCE.md

- Knowledge Area: Type System, Memory Semantics

- Software or Tool: Test harness

- Main Book: “Expert C Programming”

What you will build: A lab that runs controlled experiments showing when arrays decay and when they do not.

Why it teaches Expert C: It replaces folklore with evidence and builds intuition about types.

Core challenges you will face:

- Designing experiments -> Arrays, Pointers, Addressing

- Interpreting

sizeofresults -> Arrays, Pointers, Addressing - Explaining array parameter adjustment -> Declarations & Type System

Real World Outcome

$ ./array_pointer_lab --test sizeof

int arr[10]: sizeof = 40 bytes

int *ptr: sizeof = 8 bytes

PROOF: sizeof(array) != sizeof(pointer)

The Core Question You Are Answering

“If arrays decay to pointers, why are they still different types?”

This matters because incorrect assumptions cause incorrect function signatures and UB.

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Array decay rules

- When does decay happen?

- Book Reference: “Expert C Programming” - Ch. 4

- Parameter adjustment

- Why

int a[10]becomesint *ain parameters? - Book Reference: K&R - Ch. 5

- Why

- Pointer arithmetic

- Why does pointer math scale by element size?

- Book Reference: Reese - Ch. 3

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Experiment Coverage

- Which contexts prevent decay (

sizeof,&, initializers)? - How will you show address differences?

- Which contexts prevent decay (

- Output Clarity

- How will you present evidence to make the conclusion obvious?

- What comparisons will be most persuasive?

Thinking Exercise

Extern Mismatch

Consider a global array defined in one file and declared as a pointer in another. What breaks and why?

Questions to answer:

- How does the linker interpret those symbols?

- Why is this not just a “type mismatch” but a storage mismatch?

The Interview Questions They Will Ask

- “Are arrays and pointers the same in C?”

- “Why does

sizeofbehave differently in and out of functions?” - “Why doesn’t

int **accept a 2D array?” - “What is array-to-pointer decay?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Starting Point

Use sizeof, &array, and pointer arithmetic outputs to show differences.

Hint 2: Next Level Include a test where you pass an array to a function and show type adjustment.

Hint 3: Technical Details

Print both value and address of array, &array, and array + 1.

Hint 4: Tools/Debugging

Use -Wall -Wextra and inspect warnings about parameter types.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Arrays vs pointers | “Expert C Programming” | Ch. 4 |

| Pointers | “Understanding and Using C Pointers” | Ch. 2-3 |

Common Pitfalls and Debugging

Problem 1: “Results look the same”

- Why: You are printing only pointer values, not sizes or types.

- Fix: Include

sizeofand&arraycomparisons. - Quick test: Show

sizeof(array)vssizeof(ptr)side-by-side.

Definition of Done

- All decay exceptions are demonstrated

- Output clearly proves arrays are not pointers

- At least one counterexample is explained

- Results are reproducible across compilers

Project 3: Build a Memory Layout Visualizer

- File: project_based_ideas/SYSTEMS_PROGRAMMING/EXPERT_C_PROGRAMMING_DEEP_DIVE/P03-memory-layout-visualizer.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, C++

- Coolness Level: See REFERENCE.md

- Business Potential: See REFERENCE.md

- Difficulty: See REFERENCE.md

- Knowledge Area: Process Memory Organization

- Software or Tool: Address visualizer

- Main Book: “Expert C Programming”

What you will build: A CLI tool that prints the addresses of objects in each memory segment.

Why it teaches Expert C: It makes abstract memory segments concrete and visible.

Core challenges you will face:

- Identifying segment boundaries -> Storage Duration & Memory Layout

- Distinguishing object lifetimes -> Storage Duration & Memory Layout

- Presenting readable output -> Tooling clarity

Real World Outcome

$ ./memlayout

SEGMENT OBJECT ADDRESS

TEXT main 0x0000000000401130

RODATA "hello" 0x0000000000404008

DATA global_init 0x0000000000601030

BSS global_zero 0x0000000000601040

HEAP malloc_block 0x0000000001c2a000

STACK local_var 0x00007ffc1d2b7a2c

The Core Question You Are Answering

“How does a process’s virtual address space map program objects to memory?”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Storage duration

- How are static, automatic, and allocated objects different?

- Book Reference: “Expert C Programming” - Ch. 6

- Segments and layout

- What lives in text, rodata, data, bss, heap, stack?

- Book Reference: CS:APP - Ch. 6

- String literals

- Why are they typically read-only?

- Book Reference: Seacord - Ch. 5

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Data collection

- Which objects will you place in each segment?

- How will you label them consistently?

- Output format

- How will you order segments for readability?

- How will you align columns to show addresses clearly?

Thinking Exercise

Pointer Lifetime Map

Sketch a timeline of when each object in your program becomes valid and invalid.

Questions to answer:

- Which objects live the entire program?

- Which objects die when a function returns?

The Interview Questions They Will Ask

- “Where do string literals live?”

- “Why is returning a pointer to a local variable wrong?”

- “What is BSS and why does it exist?”

- “How does the heap grow compared to the stack?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Starting Point Use global variables, local variables, and dynamically allocated memory in one program.

Hint 2: Next Level Print the addresses of each object and group them by expected segment.

Hint 3: Technical Details

Use printf-style formatting to align columns and show hex addresses.

Hint 4: Tools/Debugging

Compare your output to nm or objdump -t to verify segments.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Memory layout | “Expert C Programming” | Ch. 6 |

| Virtual memory | CS:APP | Ch. 9 |

Common Pitfalls and Debugging

Problem 1: “Addresses appear unordered”

- Why: ASLR randomizes address layouts between runs.

- Fix: Document that addresses change, but ordering remains.

- Quick test: Run twice and compare relative segment ordering.

Definition of Done

- All major segments are represented

- Output labels are accurate

- You can explain why each object appears in its segment

- Demonstrates effect of ASLR

Project 4: Implement a Stack Frame Inspector

- File: project_based_ideas/SYSTEMS_PROGRAMMING/EXPERT_C_PROGRAMMING_DEEP_DIVE/P04-stack-frame-inspector.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, C++

- Coolness Level: See REFERENCE.md

- Business Potential: See REFERENCE.md

- Difficulty: See REFERENCE.md

- Knowledge Area: ABI, Calling Conventions

- Software or Tool: Stack walker

- Main Book: CS:APP

What you will build: A tool that walks stack frames and displays call-chain metadata.

Why it teaches Expert C: It connects high-level calls to low-level ABI mechanics.

Core challenges you will face:

- Walking frame pointers -> ABI & Calling Conventions

- Handling optimized builds -> ABI & Calling Conventions

- Rendering readable traces -> Debugging design

Real World Outcome

$ ./stacktrace_demo

#0 main() @ 0x4012a0

#1 parse_config() @ 0x4011f0

#2 load_file() @ 0x4010c0

#3 _start() @ 0x400f00

The Core Question You Are Answering

“What exactly is stored in a stack frame, and how can I walk the chain?”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Calling conventions

- What is callee-saved vs caller-saved?

- Book Reference: CS:APP - Ch. 3

- Frame pointer usage

- When is it omitted, and why does it matter?

- Book Reference: ABI documentation

- Return addresses

- How does the call instruction store the return address?

- Book Reference: CS:APP - Ch. 3

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Stack walking strategy

- Will you rely on frame pointers or debug metadata?

- How will you handle optimized builds?

- Symbol resolution

- How will you map addresses to function names?

- What toolchain will you depend on (

nm,addr2line)?

Thinking Exercise

Frame Layout Sketch

Draw a stack frame with saved registers, return address, and locals.

Questions to answer:

- Which values are pushed by the caller vs callee?

- What happens if the frame pointer is omitted?

The Interview Questions They Will Ask

- “What is a stack frame?”

- “What does a frame pointer do?”

- “How does stack unwinding work?”

- “Why do optimized builds make debugging harder?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Starting Point Compile with frame pointers enabled to simplify initial stack walks.

Hint 2: Next Level Use symbol resolution tools to map addresses to names.

Hint 3: Technical Details Follow the saved frame pointer chain until you hit a null or invalid frame.

Hint 4: Tools/Debugging

Compare your output to gdb backtraces for validation.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Stack frames | CS:APP | Ch. 3 |

| ABI | System V AMD64 ABI | Sections on calling convention |

Common Pitfalls and Debugging

Problem 1: “Backtrace stops early”

- Why: Frame pointer omission or corrupted stack.

- Fix: Compile with frame pointers; verify stack alignment.

- Quick test: Rebuild with debug flags and compare.

Definition of Done

- Stack frames are walked correctly

- Output matches debugger backtrace

- Works on a multi-level call chain

- Handles or documents optimized build limitations

Project 5: Create a Type Promotion Tester

- File: project_based_ideas/SYSTEMS_PROGRAMMING/EXPERT_C_PROGRAMMING_DEEP_DIVE/P05-type-promotion-tester.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: C++, Rust

- Coolness Level: See REFERENCE.md

- Business Potential: See REFERENCE.md

- Difficulty: See REFERENCE.md

- Knowledge Area: Integer Conversions

- Software or Tool: Interactive tester

- Main Book: “Expert C Programming”

What you will build: An interactive CLI that demonstrates integer promotion and conversion rules.

Why it teaches Expert C: Conversions are invisible; you make them visible.

Core challenges you will face:

- Designing experiments -> Integer Conversions & Representation

- Explaining surprising outcomes -> Integer Conversions & Representation

- Avoiding misleading output -> Output design

Real World Outcome

$ ./typepromo

Case: signed vs unsigned

signed i = -1

unsigned u = 1

Result: i < u is FALSE (i converted to unsigned)

The Core Question You Are Answering

“How does C silently convert types, and why does it cause bugs?”

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Integer promotions

- What types promote to

int? - Book Reference: “Expert C Programming” - Ch. 2

- What types promote to

- Usual arithmetic conversions

- How is a common type chosen?

- Book Reference: Seacord - Ch. 3

- Signed vs unsigned behavior

- Why does signed overflow matter?

- Book Reference: C standard (conversions)

Questions to Guide Your Design

- Scenario selection

- Which comparisons are most surprising?

- How will you demonstrate overflow rules?

- Output clarity

- How will you show before/after conversion values?

- How will you explain the rule in plain English?

Thinking Exercise

Promotion Walkthrough

Given a mixed expression with char, short, int, and unsigned, determine the common type.

Questions to answer:

- Which step promotes first?

- Which type dominates in the usual arithmetic conversion?

The Interview Questions They Will Ask

- “Why does

-1 < 1uevaluate the way it does?” - “What is integer promotion?”

- “When does signed overflow become UB?”

- “Why is

chardangerous in arithmetic?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Starting Point Start with just one comparison and show the conversion.

Hint 2: Next Level Add a matrix of cases (signed/unsigned, narrow/wide types).

Hint 3: Technical Details Compute values in hexadecimal to make conversions obvious.

Hint 4: Tools/Debugging

Use compiler warnings (-Wconversion) to detect implicit conversions.