Learning ESP32 Programming: Project Recommendations

Goal

Master ESP32 programming to unlock the full potential of one of the most powerful and versatile microcontrollers in the IoT ecosystem. The ESP32 isn’t just another microcontroller—it’s a complete system-on-chip (SoC) that combines:

- Dual-core processing power (up to 240 MHz) that rivals early desktop computers

- Integrated WiFi and Bluetooth (BLE 4.2, classic Bluetooth) in a single package

- Rich peripheral set (GPIO, ADC, DAC, PWM, I2C, SPI, UART, I2S, CAN, touch sensors)

- Ultra-low power modes capable of running months on a coin cell battery

- Cryptographic acceleration for secure IoT applications

- Real-time operating system (FreeRTOS) for concurrent task management

By completing these projects, you’ll gain expertise that places you at the intersection of embedded systems, wireless communication, real-time programming, and power-efficient design. You’ll understand not just how to use ESP32, but why it dominates the IoT landscape—from hobbyist projects to production systems controlling millions of devices.

What mastering ESP32 means:

You’ll be able to design and implement complete IoT solutions from scratch. When someone says “I need a device that monitors temperature, sends data to the cloud, and runs for months on battery,” you’ll immediately know the architecture, the tradeoffs, and the implementation path. You’ll debug cryptic crashes in multithreaded code, optimize power consumption from milliamps to microamps, and navigate the complex dance between WiFi, Bluetooth, and application logic sharing limited resources.

This knowledge transfers directly to:

- Professional IoT development (smart home, industrial sensors, wearables)

- Embedded systems architecture (understanding real-time constraints, resource management)

- Wireless protocol mastery (BLE, WiFi, ESP-NOW mesh networking)

- Production firmware practices (OTA updates, secure boot, failure recovery)

The ESP32 is manufactured by Espressif Systems and has sold over 500 million units. It powers products from Philips Hue controllers to Tesla charging stations. Learning it deeply means learning principles that apply across the entire embedded industry.

Core Concept Analysis

To truly understand ESP32 programming, you need to master these fundamental building blocks:

| Concept Layer | What You’ll Learn |

|---|---|

| Hardware I/O | GPIO control, ADC/DAC, PWM signals, reading sensors |

| Communication Protocols | I2C, SPI, UART - talking to peripherals |

| Wireless Connectivity | WiFi (station/AP modes), Bluetooth/BLE |

| Real-Time Operating System | FreeRTOS tasks, queues, semaphores, timing |

| Interrupts & Timers | Hardware interrupts, watchdog timers, event-driven programming |

| Power Management | Deep sleep, light sleep, wake-up sources |

| Memory Constraints | Stack/heap on embedded, flash storage, NVS |

Project 1: Environmental Monitor with Web Dashboard

- File: environmental_monitor_esp32.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: MicroPython, Rust, Arduino C++

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: Level 2: The “Micro-SaaS / Pro Tool”

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate (The Developer)

- Knowledge Area: Embedded Systems, GPIO, WiFi, I2C

- Software or Tool: ESP-IDF, ESP32

- Main Book: Making Embedded Systems by Elecia White

What you’ll build: A sensor station that reads temperature, humidity, and air quality, serves a real-time web dashboard over WiFi, and logs data to flash storage.

Why it teaches ESP32: This project forces you to understand GPIO for sensor reading, I2C protocol for sensor communication, WiFi in station mode, the ESP32’s web server capabilities, and non-volatile storage—all core ESP32 skills in one practical device.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Reading analog and digital sensors through GPIO and I2C (maps to hardware I/O)

- Setting up WiFi connection and handling disconnects gracefully (maps to wireless connectivity)

- Serving HTTP responses and handling concurrent web requests (maps to FreeRTOS tasks)

- Storing historical data in flash without wearing it out (maps to memory/storage management)

Key Concepts:

- GPIO and ADC: “ESP-IDF Programming Guide - Peripherals API” - Espressif official docs

- I2C Protocol: “The Book of I2C” by Randall Hyde - Chapter 1-3

- WiFi Programming: “IoT Product Development Using ESP32 Microcontrollers” by Sai Yamanoor - Chapter on WiFi

- Embedded Web Servers: “Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Edition” by Elecia White - Chapter 10

Difficulty: Beginner-Intermediate Time estimate: 1-2 weeks Prerequisites: Basic C programming, familiarity with breadboards

Real World Outcome

You’ll build a physical environmental monitoring station that serves a live web dashboard. Here’s exactly what you’ll experience:

Physical Setup:

- ESP32 development board on a breadboard

- BME280 sensor (I2C) or DHT22 sensor (GPIO) connected for temperature and humidity

- Optional: MQ-135 air quality sensor (analog ADC)

- LED indicator for WiFi status (blinking = connecting, solid = connected)

- Powered via USB cable (later can use 5V power adapter)

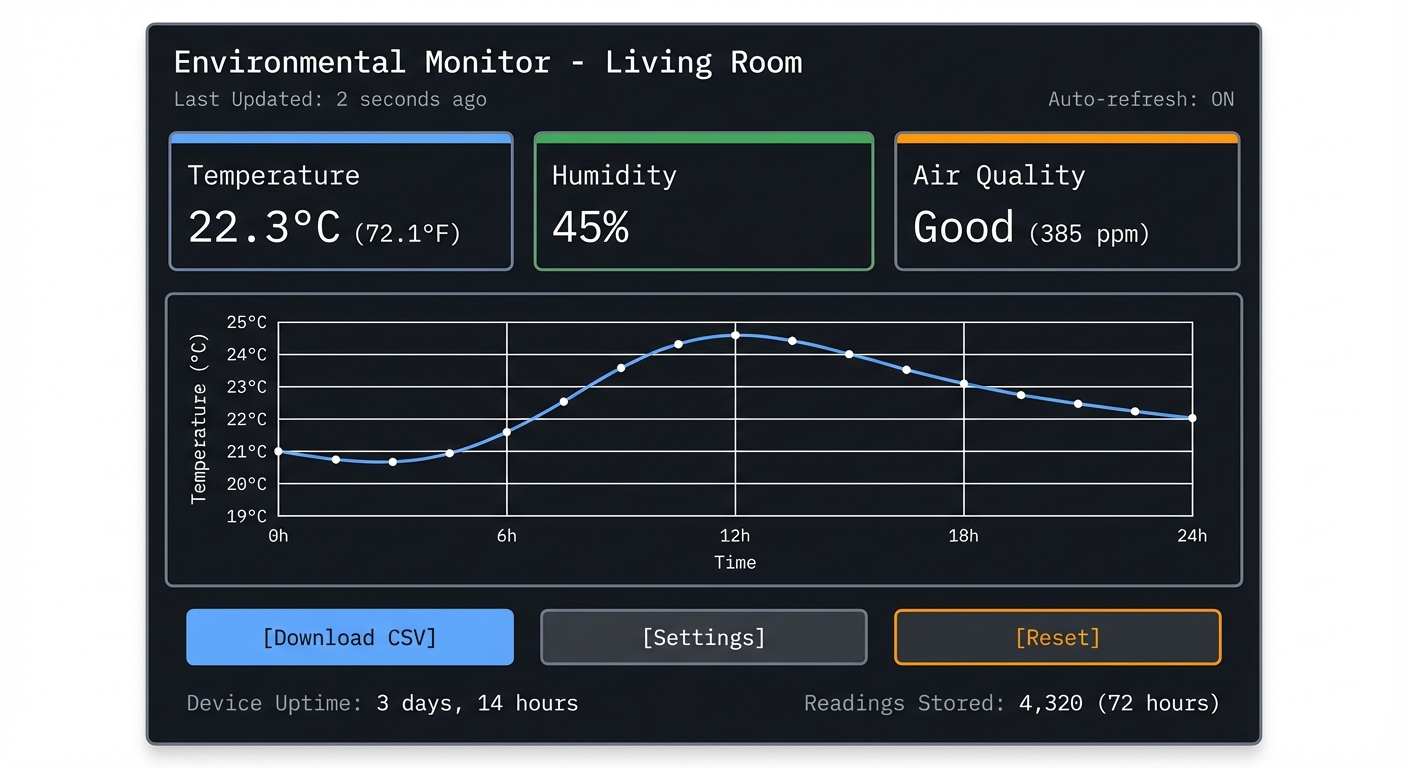

What You’ll See on the Web Dashboard (accessible from any device on your network):

┌─────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Environmental Monitor - Living Room │

├─────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ Temperature: 22.3°C (72.1°F) │

│ Humidity: 45% │

│ Air Quality: Good (385 ppm) │

│ │

│ Last Updated: 2 seconds ago │

│ Auto-refresh: ON │

│ │

│ ┌────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Temperature (Last 24 Hours) │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ 25°C ┤ ╭──╮ │ │

│ │ 23°C ┤ ╭───╯ ╰──╮ │ │

│ │ 21°C ┤ ╭───╯ ╰──╮ │ │

│ │ 19°C ┤──╯ ╰── │ │

│ │ └─────────────────────── │ │

│ │ 0h 6h 12h 18h 24h│ │

│ └────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ [Download CSV] [Settings] [Reset] │

│ │

│ Device Uptime: 3 days, 14 hours │

│ Readings Stored: 4,320 (72 hours) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────┘

Serial Monitor Output (for debugging):

$ pio device monitor

[2024-12-27 10:15:30] ESP32 Environmental Monitor v1.0

[2024-12-27 10:15:30] =====================================

[2024-12-27 10:15:30] Chip: ESP32-D0WDQ6 (revision 1)

[2024-12-27 10:15:30] Cores: 2, Flash: 4MB

[2024-12-27 10:15:30] Free heap: 298,432 bytes

[2024-12-27 10:15:30] =====================================

[2024-12-27 10:15:31] Initializing I2C bus (SDA: GPIO21, SCL: GPIO22)

[2024-12-27 10:15:31] BME280 sensor detected (Chip ID: 0x60)

[2024-12-27 10:15:31] Sensor calibration complete

[2024-12-27 10:15:32] Connecting to WiFi SSID: YourNetworkName

[2024-12-27 10:15:32] WiFi status: Connecting...

[2024-12-27 10:15:34] WiFi connected!

[2024-12-27 10:15:34] IP Address: 192.168.1.150

[2024-12-27 10:15:34] Signal strength: -45 dBm (Excellent)

[2024-12-27 10:15:35] Starting HTTP server on port 80

[2024-12-27 10:15:35] Dashboard available at: http://192.168.1.150

[2024-12-27 10:15:36] Reading sensors every 10 seconds...

[2024-12-27 10:15:36] Temperature: 22.3°C | Humidity: 45.2% | Pressure: 1013.2 hPa

[2024-12-27 10:15:36] Data saved to NVS (entry #1)

[2024-12-27 10:15:46] Temperature: 22.4°C | Humidity: 45.1% | Pressure: 1013.3 hPa

[2024-12-27 10:15:46] Data saved to NVS (entry #2)

[2024-12-27 10:16:03] HTTP GET / from 192.168.1.101

[2024-12-27 10:16:03] Served dashboard HTML (3.2 KB)

[2024-12-27 10:16:04] HTTP GET /api/readings from 192.168.1.101

[2024-12-27 10:16:04] Sent JSON: {"temp":22.4,"humidity":45.1,"pressure":1013.3}

[2024-12-27 10:20:15] WiFi disconnected! Reason: AP not found

[2024-12-27 10:20:15] Attempting reconnection...

[2024-12-27 10:20:18] WiFi reconnected to 192.168.1.150

Real-World Behavior:

- Power on: LED blinks rapidly while connecting to WiFi, then stays solid green

- Open browser: Navigate to http://192.168.1.150 from your phone or laptop

- See live data: Numbers update every 10 seconds without page reload (using AJAX or WebSocket)

- Historical data: Dashboard shows temperature graph for the last 24 hours

- Portability: Move the device to different rooms to monitor climate in bedroom, garage, etc.

- Power failure recovery: If power is lost, device reconnects to WiFi automatically and continues logging

Impressive Demo Moment: Place the sensor near a window. Watch the temperature graph dip when you open the window on a cold day. Close it, and see the temperature gradually rise. The web dashboard visualizes this in real-time—a tangible connection between physical environment and digital data.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do you transform raw sensor data from the physical world into a web-accessible, user-friendly dashboard using a microcontroller?”

Before writing any code, understand this: IoT devices are bridges between the analog world (temperature, pressure, humidity) and the digital world (web browsers, apps, databases). This project asks: how do you reliably read sensor data, serve it over WiFi, and store it persistently—all on a chip with only 520KB of RAM and no operating system like Linux?

This isn’t just about reading sensors—it’s about understanding:

- How I2C communication protocol transfers data between chips

- How WiFi station mode differs from access point mode

- How embedded web servers handle HTTP requests without Apache or Nginx

- How to persist data in flash memory without a filesystem like ext4

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- I2C Communication Protocol

- What are SDA (data) and SCL (clock) lines?

- How does I2C addressing work? (7-bit vs 10-bit addresses)

- What is clock stretching? Why do some sensors need it?

- How do you detect if a device is present on the bus?

- What happens if multiple devices have the same address?

- Book Reference: “Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Edition” by Elecia White - Chapter 6: “Communicating with Peripherals”

- GPIO (General Purpose Input/Output)

- What’s the difference between digital input, digital output, and analog input (ADC)?

- What is pull-up vs pull-down resistor? When do you need them?

- How does the ESP32 ADC work? What is the voltage range? (0-3.3V)

- Why can’t ESP32 directly read 5V sensors? (Needs voltage divider)

- Book Reference: “Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Edition” by Elecia White - Chapter 5: “Getting Your Hands Dirty”

- WiFi Station Mode vs Access Point Mode

- Station mode: ESP32 connects to existing WiFi router (what you want for this project)

- Access Point mode: ESP32 acts as WiFi router (phones connect directly to it)

- What is an SSID? What is a MAC address?

- How does WPA2 handshake work? (Don’t need to implement, but understand it)

- Book Reference: “IoT Product Development Using ESP32 Microcontrollers” by Sai Yamanoor - Chapter 3: “WiFi Connectivity”

- HTTP Protocol Basics

- What is a GET request? What is a POST request?

- What are HTTP headers? (Content-Type, Content-Length)

- What is the difference between serving HTML and serving JSON?

- How does a browser know to auto-refresh data? (AJAX, WebSocket, or meta refresh)

- Book Reference: “HTTP: The Definitive Guide” by David Gourley - Chapters 1-3 (or quick online tutorial)

- Non-Volatile Storage (NVS) on ESP32

- What is flash memory? How does it differ from RAM?

- What is NVS? (Key-value storage that survives reboots)

- What is flash wear-out? How many write cycles can flash handle? (~100,000 cycles)

- How do you avoid wearing out flash? (Write sparingly, use wear leveling)

- Book Reference: “ESP32 Technical Reference Manual” - Chapter on Non-Volatile Storage

- ADC (Analog-to-Digital Converter)

- How does ADC convert voltage to a number? (0V = 0, 3.3V = 4095 for 12-bit ADC)

- What is ADC resolution? ESP32 has 12-bit ADC (0-4095 range)

- What is ADC attenuation? Why does ESP32 need it?

- How accurate is ESP32’s ADC? (Not very—needs calibration for precision)

- Book Reference: “Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Edition” by Elecia White - Chapter 7: “Analog and Digital Conversions”

- FreeRTOS Tasks (ESP32’s Operating System)

- ESP32 runs FreeRTOS, a real-time operating system

- What is a task? (Similar to a thread on Linux)

- How do you create concurrent tasks? (Sensor reading, WiFi handling, web serving)

- What is task priority? How does the scheduler decide which task runs?

- Book Reference: “Mastering the FreeRTOS Real Time Kernel” - Chapters 1-3 (free PDF from FreeRTOS.org)

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Sensor Selection

- Should you use DHT22 (1-wire protocol, simple) or BME280 (I2C, more accurate)?

- DHT22: Cheaper, less accurate, slower (2-second read time)

- BME280: More expensive, very accurate, also reads barometric pressure

- Which sensor matches your learning goals vs budget?

- Data Logging Strategy

- How often should you read sensors? Every second? Every 10 seconds?

- How much historical data should you store? 24 hours? 7 days?

- If you read every 10 seconds for 24 hours = 8,640 readings

- Each reading = ~12 bytes (3 floats) = ~100KB total

- Does this fit in ESP32’s NVS? (Yes, easily)

- WiFi Reconnection

- What happens if WiFi router reboots?

- What happens if WiFi password changes?

- Should you retry forever? Give up after N attempts?

- Should you create an access point for configuration if WiFi fails?

- Web Dashboard Design

- Should data auto-refresh? How often? (Every 5 seconds?)

- Should you use JavaScript to fetch data (AJAX) or server-sent events?

- Should you show a graph? (Harder, requires charting library)

- Should you make it mobile-friendly? (Responsive CSS)

- Power Management

- For this project, USB power is fine (always-on monitoring)

- But could you add deep sleep to run on battery? (Future enhancement)

- How much power does WiFi use? (~160mA) vs deep sleep (~10µA)?

- Error Handling

- What if sensor fails to initialize? (I2C device not found)

- What if WiFi never connects? (Show error on serial, blink LED in pattern)

- What if NVS is full? (Overwrite oldest data, circular buffer)

- What if HTTP request is malformed? (Return HTTP 400 error)

Thinking Exercise

Trace Data Flow By Hand

Before coding, trace this end-to-end flow on paper:

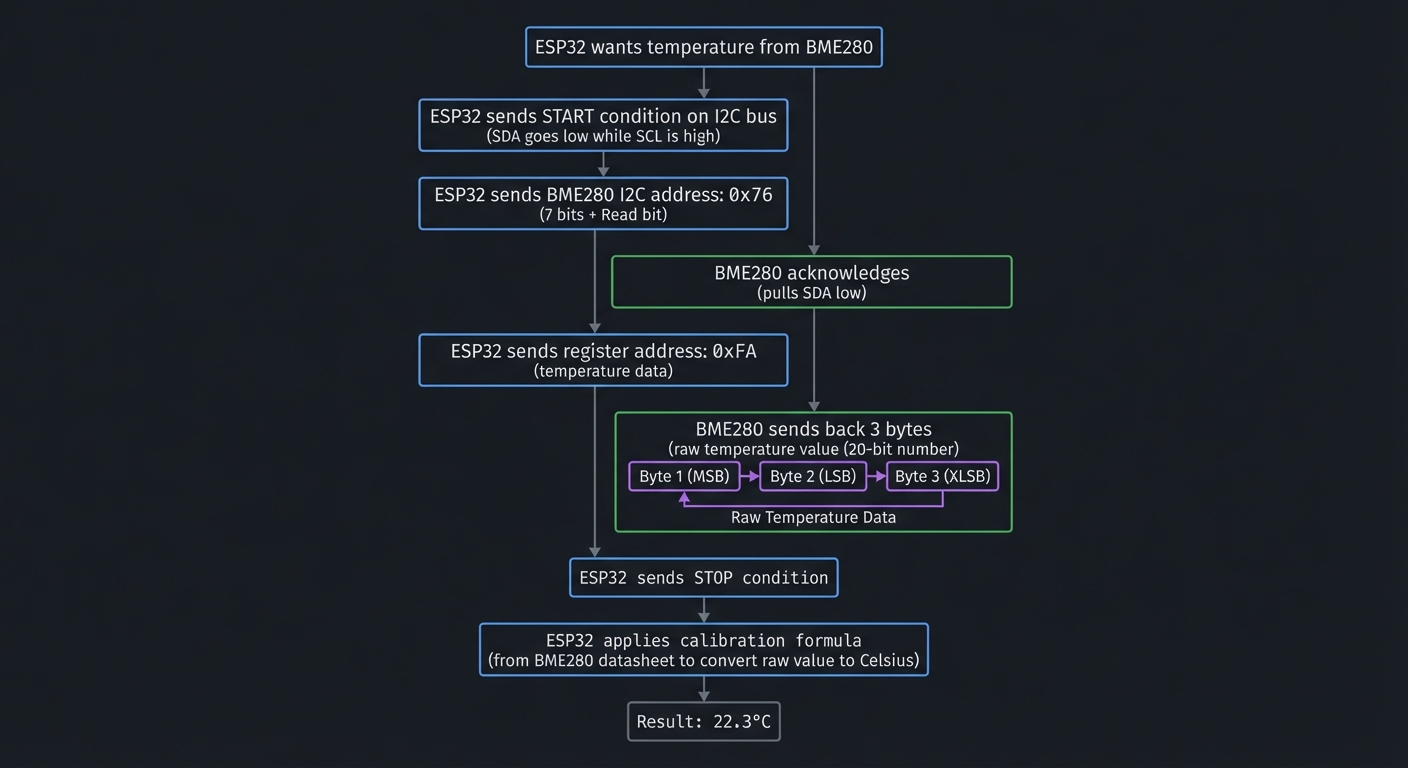

Step 1: Reading the BME280 Sensor (I2C)

ESP32 wants temperature from BME280

↓

ESP32 sends START condition on I2C bus (SDA goes low while SCL is high)

↓

ESP32 sends BME280's I2C address: 0x76 (7 bits) + Read bit

↓

BME280 acknowledges (pulls SDA low)

↓

ESP32 sends register address: 0xFA (temperature data)

↓

BME280 sends back 3 bytes: raw temperature value (20-bit number)

↓

ESP32 sends STOP condition

↓

ESP32 applies calibration formula (from BME280 datasheet) to convert raw value to Celsius

↓

Result: 22.3°C

Questions while tracing:

- How does ESP32 know the BME280’s address is 0x76? (Read the datasheet)

- What if another I2C device also uses 0x76? (Conflict! Must change one address)

- Why 3 bytes for temperature? (BME280 uses 20-bit resolution)

- Where does the calibration formula come from? (Stored in BME280’s internal EEPROM)

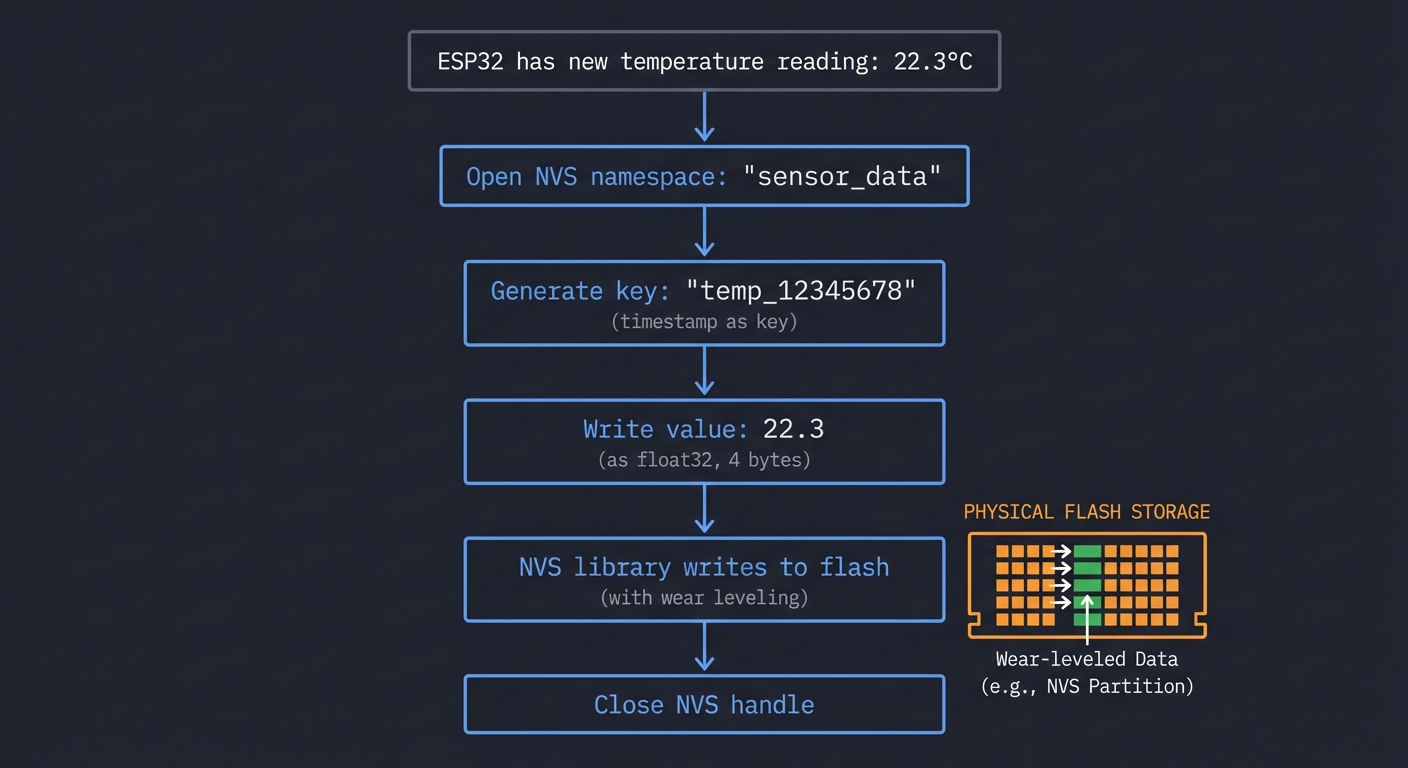

Step 2: Storing Data in NVS (Flash)

ESP32 has new temperature reading: 22.3°C

↓

Open NVS namespace: "sensor_data"

↓

Generate key: "temp_12345678" (timestamp as key)

↓

Write value: 22.3 (as float32, 4 bytes)

↓

NVS library writes to flash (with wear leveling)

↓

Close NVS handle

Questions while tracing:

- How many times can you write to flash before it wears out? (~100,000 erase cycles per sector)

- If you write every 10 seconds, how long until wear-out? (100,000 * 10s = ~11 days per sector)

- How does wear leveling extend this? (Spreads writes across sectors = months/years)

- Should you store every reading, or downsample after a while? (Store raw for 24h, then hourly averages)

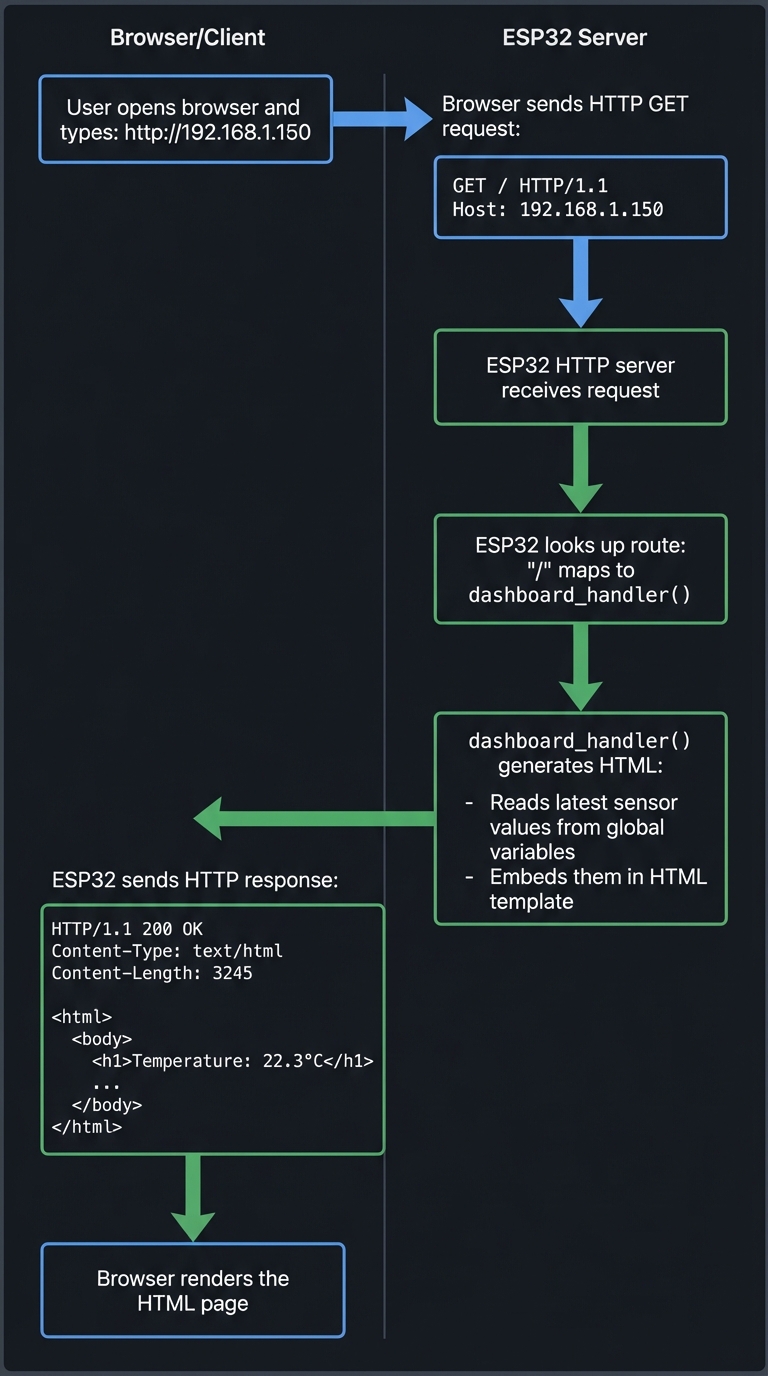

Step 3: Serving the Web Dashboard (HTTP)

User opens browser and types: http://192.168.1.150

↓

Browser sends HTTP GET request:

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.1.150

↓

ESP32's HTTP server receives request

↓

ESP32 looks up route: "/" maps to dashboard_handler()

↓

dashboard_handler() generates HTML:

- Reads latest sensor values from global variables

- Embeds them in HTML template

↓

ESP32 sends HTTP response:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html

Content-Length: 3245

<html>

<body>

<h1>Temperature: 22.3°C</h1>

...

↓

Browser renders the HTML page

Questions while tracing:

- What if 5 people open the dashboard simultaneously? (FreeRTOS handles concurrent connections)

- How does JavaScript auto-refresh work? (Periodic fetch() or WebSocket)

- Could you serve CSS and JavaScript files too? (Yes, create separate routes)

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “Explain how I2C communication works. What are the key signals?”

- Expected: SDA (data), SCL (clock), start/stop conditions, addressing, ACK/NACK

- “Why use I2C instead of SPI for the BME280 sensor?”

- Expected: I2C uses 2 wires (SDA, SCL), SPI uses 4+ (MISO, MOSI, CLK, CS). I2C is simpler for short distances.

- “How does WiFi station mode differ from access point mode?”

- Expected: Station = connect to existing WiFi. AP = become WiFi hotspot. Station is for internet access.

- “What is NVS and why not use a regular file system?”

- Expected: NVS is key-value storage optimized for flash wear leveling. Files are overkill for simple data.

- “How would you handle WiFi disconnection gracefully?”

- Expected: Retry connection in a loop, blink LED to indicate status, continue sensor logging offline.

- “What is the ESP32’s ADC resolution and voltage range?”

- Expected: 12-bit (0-4095), 0-3.3V (with attenuation can measure up to ~2.45V reliably)

- “How would you optimize power consumption for battery operation?”

- Expected: Use deep sleep, wake periodically, disable WiFi when not transmitting, use efficient sensors

- “How do FreeRTOS tasks differ from threads on Linux?”

- Expected: Similar concept, but FreeRTOS is lighter. Tasks have priorities, scheduler is preemptive.

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with Blinking an LED (Verify Setup)

Before sensors or WiFi, prove your ESP32 works:

#include <Arduino.h>

#define LED_PIN 2 // Built-in LED on most ESP32 boards

void setup() {

pinMode(LED_PIN, OUTPUT);

}

void loop() {

digitalWrite(LED_PIN, HIGH); // Turn LED on

delay(1000); // Wait 1 second

digitalWrite(LED_PIN, LOW); // Turn LED off

delay(1000);

}

Upload this code. If LED blinks, your toolchain works. If not, check:

- Is the correct COM port selected?

- Is the board in bootloader mode? (Hold BOOT button while uploading)

- Is the board model correct in platformio.ini? (esp32dev, esp32-s3, etc.)

Hint 2: Read BME280 Sensor (I2C)

Use the Adafruit BME280 library (simpler than writing I2C from scratch):

#include <Wire.h>

#include <Adafruit_BME280.h>

Adafruit_BME280 bme;

void setup() {

Serial.begin(115200);

if (!bme.begin(0x76)) { // I2C address (0x76 or 0x77)

Serial.println("Could not find BME280 sensor!");

while (1); // Halt

}

Serial.println("BME280 sensor initialized");

}

void loop() {

float temp = bme.readTemperature();

float humidity = bme.readHumidity();

float pressure = bme.readPressure() / 100.0; // Convert to hPa

Serial.printf("Temp: %.1f°C | Humidity: %.1f%% | Pressure: %.1f hPa\n",

temp, humidity, pressure);

delay(10000); // Read every 10 seconds

}

Test: Open serial monitor (115200 baud). You should see readings every 10 seconds.

Hint 3: Connect to WiFi

#include <WiFi.h>

const char* ssid = "YourNetworkName";

const char* password = "YourPassword";

void setup() {

Serial.begin(115200);

WiFi.begin(ssid, password);

Serial.print("Connecting to WiFi");

while (WiFi.status() != WL_CONNECTED) {

delay(500);

Serial.print(".");

}

Serial.println("\nWiFi connected!");

Serial.print("IP Address: ");

Serial.println(WiFi.localIP());

}

void loop() {

// WiFi stays connected in background

}

Test: Serial monitor should show your ESP32’s IP address (e.g., 192.168.1.150).

Hint 4: Serve a Simple Web Page

#include <WiFi.h>

#include <WebServer.h>

WebServer server(80);

void handleRoot() {

String html = "<html><body>";

html += "<h1>ESP32 Environmental Monitor</h1>";

html += "<p>Temperature: " + String(bme.readTemperature()) + " °C</p>";

html += "<p>Humidity: " + String(bme.readHumidity()) + " %</p>";

html += "</body></html>";

server.send(200, "text/html", html);

}

void setup() {

// ... WiFi connection code from Hint 3 ...

server.on("/", handleRoot);

server.begin();

Serial.println("HTTP server started");

}

void loop() {

server.handleClient(); // Process incoming requests

}

Test: Open browser, go to http://192.168.1.150 (your ESP32’s IP). You should see the web page.

Hint 5: Add Auto-Refresh with JavaScript

Modify the HTML to fetch data every 5 seconds:

void handleRoot() {

String html = R"rawliteral(

<html>

<head>

<title>Environmental Monitor</title>

<script>

setInterval(function() {

fetch('/api/readings')

.then(response => response.json())

.then(data => {

document.getElementById('temp').innerText = data.temperature + ' °C';

document.getElementById('humidity').innerText = data.humidity + ' %';

});

}, 5000); // Update every 5 seconds

</script>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Environmental Monitor</h1>

<p>Temperature: <span id="temp">--</span></p>

<p>Humidity: <span id="humidity">--</span></p>

</body>

</html>

)rawliteral";

server.send(200, "text/html", html);

}

void handleAPI() {

String json = "{";

json += "\"temperature\":" + String(bme.readTemperature()) + ",";

json += "\"humidity\":" + String(bme.readHumidity());

json += "}";

server.send(200, "application/json", json);

}

void setup() {

// ...

server.on("/", handleRoot);

server.on("/api/readings", handleAPI);

server.begin();

}

Hint 6: Store Data in NVS

#include <Preferences.h>

Preferences preferences;

void saveReading(float temp, float humidity) {

preferences.begin("sensor_data", false); // false = read/write mode

// Store latest reading

preferences.putFloat("last_temp", temp);

preferences.putFloat("last_humidity", humidity);

// Increment reading count

int count = preferences.getInt("reading_count", 0);

preferences.putInt("reading_count", count + 1);

preferences.end();

}

void loop() {

float temp = bme.readTemperature();

float humidity = bme.readHumidity();

saveReading(temp, humidity);

Serial.println("Data saved to NVS");

delay(10000);

}

Test: Reboot ESP32. Check serial monitor—reading_count should persist across reboots.

Hint 7: Handle WiFi Reconnection

void reconnectWiFi() {

if (WiFi.status() != WL_CONNECTED) {

Serial.println("WiFi disconnected! Reconnecting...");

WiFi.disconnect();

WiFi.begin(ssid, password);

int attempts = 0;

while (WiFi.status() != WL_CONNECTED && attempts < 20) {

delay(500);

Serial.print(".");

attempts++;

}

if (WiFi.status() == WL_CONNECTED) {

Serial.println("\nReconnected!");

} else {

Serial.println("\nFailed to reconnect. Will retry later.");

}

}

}

void loop() {

reconnectWiFi(); // Check and reconnect if needed

server.handleClient();

// ... rest of loop ...

}

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| I2C protocol fundamentals | “Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Edition” by Elecia White | Ch. 6: “Communicating with Peripherals” |

| GPIO and ADC basics | “Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Edition” by Elecia White | Ch. 5: “Getting Your Hands Dirty”, Ch. 7: “Analog/Digital Conversions” |

| WiFi on ESP32 | “IoT Product Development Using ESP32 Microcontrollers” by Sai Yamanoor | Ch. 3: “WiFi Connectivity” |

| HTTP protocol basics | “HTTP: The Definitive Guide” by David Gourley | Ch. 1-3: HTTP Basics |

| Embedded web servers | “Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Edition” by Elecia White | Ch. 10: “Networked Devices” |

| FreeRTOS tasks | “Mastering the FreeRTOS Real Time Kernel” | Ch. 1-3: Tasks and Scheduling (free PDF) |

| ESP32 NVS storage | “ESP32 Technical Reference Manual” | Non-Volatile Storage chapter (online) |

| Sensor datasheets | BME280 Datasheet (Bosch) | Full datasheet for I2C register map |

| Arduino programming | “Programming Arduino: Getting Started with Sketches” by Simon Monk | Ch. 1-5: Arduino/C basics |

Learning milestones:

- Milestone 1: LED blinks, sensor reads to serial monitor—you understand GPIO and serial communication

- Milestone 2: Web page loads with live data—you understand WiFi station mode and HTTP serving

- Milestone 3: Data persists across reboots—you understand NVS and flash storage limitations

Project 2: Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) Remote Control

- File: ble_remote_control_esp32.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: MicroPython, Rust, Arduino C++

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: Level 2: The “Micro-SaaS / Pro Tool”

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate (The Developer)

- Knowledge Area: Embedded Systems, BLE, GATT, FreeRTOS

- Software or Tool: ESP-IDF, ESP32, Bluetooth

- Main Book: Getting Started with Bluetooth Low Energy by Kevin Townsend

What you’ll build: A wireless controller that pairs with your phone via BLE, sends button presses and joystick positions, and can control games or applications on your computer/phone.

Why it teaches ESP32: BLE is one of ESP32’s killer features. Building a controller forces you to understand the BLE stack (GATT services, characteristics, advertising), hardware interrupts for responsive button input, and battery-efficient design patterns.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Implementing BLE GATT server with custom services and characteristics (maps to BLE stack)

- Debouncing physical buttons and reading analog joysticks via interrupts (maps to interrupts/GPIO)

- Maintaining responsive controls while managing BLE connection (maps to FreeRTOS task priorities)

- Minimizing power consumption for battery operation (maps to power management)

Key Concepts:

- BLE Protocol Stack: “Getting Started with Bluetooth Low Energy” by Kevin Townsend - Chapters 1-4

- Hardware Interrupts: “Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Edition” by Elecia White - Chapter 5

- Debouncing: “The Art of Electronics” by Horowitz & Hill - Section on switch debouncing

- FreeRTOS Tasks: “Mastering the FreeRTOS Real Time Kernel” - FreeRTOS official guide (free PDF)

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 2-3 weeks Prerequisites: Project 1 completed, basic understanding of wireless protocols

Real world outcome:

- A physical controller in your hands that pairs with your phone

- Control a game, presentation slides, or media player wirelessly

- See battery percentage on your phone’s Bluetooth settings

Learning milestones:

- Milestone 1: Phone discovers and connects to your ESP32—you understand BLE advertising

- Milestone 2: Button presses appear in a BLE scanner app—you understand GATT characteristics

- Milestone 3: Controller works for hours on battery—you understand power optimization

Real World Outcome

You’ll build a physical wireless controller that connects to your phone or computer via Bluetooth Low Energy. Here’s exactly what you’ll experience:

Physical Setup:

- An ESP32 with 4-8 tactile buttons and a dual-axis joystick (or two potentiometers)

- Optional: LED indicators for connection status and battery level

- 3.7V LiPo battery (500-1000mAh) for portable operation

- Custom 3D-printed enclosure (optional but makes it feel professional)

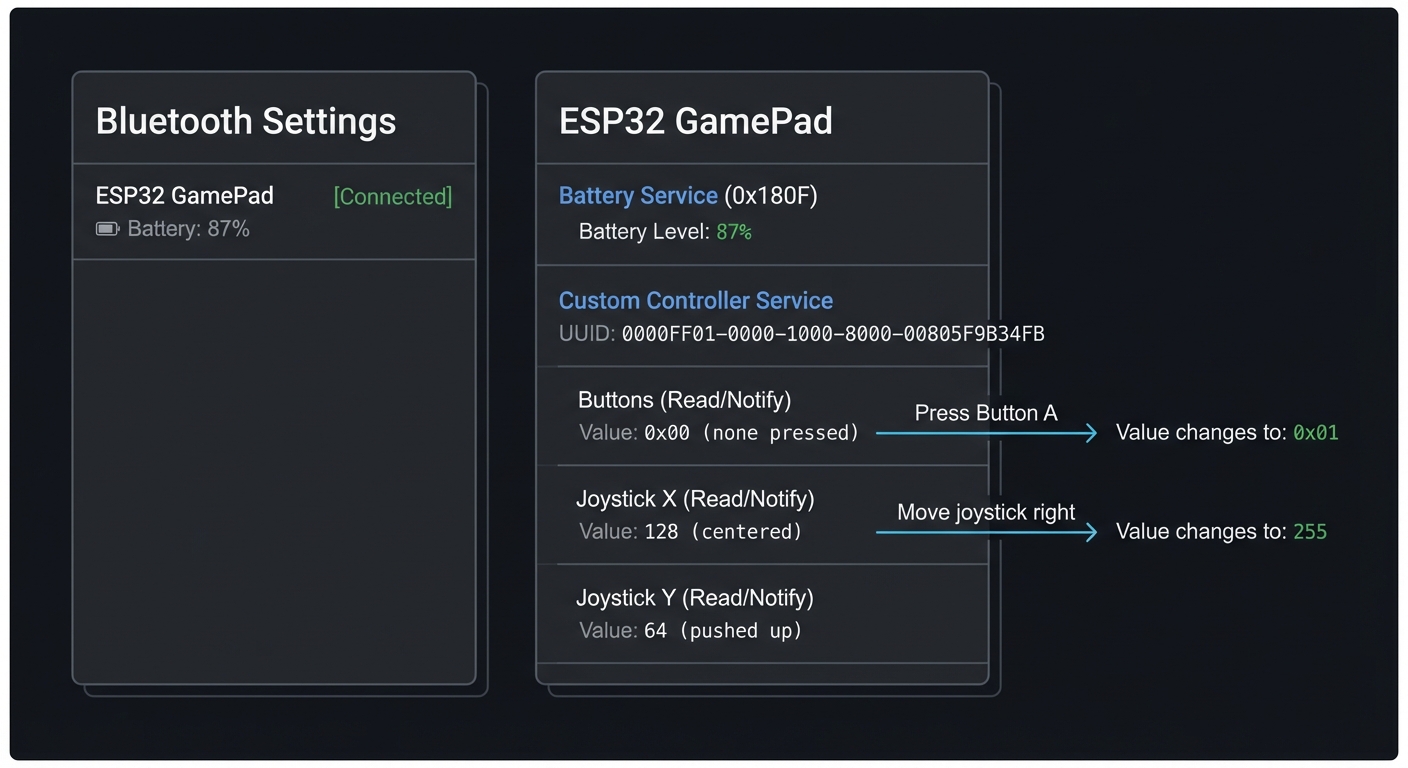

What You’ll See on Your Phone:

Bluetooth Settings (iOS/Android):

┌────────────────────────────────┐

│ Bluetooth Devices │

├────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ ESP32 GamePad [Connected] │

│ Battery: 87% │

│ │

└────────────────────────────────┘

BLE Scanner App (nRF Connect):

┌────────────────────────────────┐

│ ESP32 GamePad │

├────────────────────────────────┤

│ Services: │

│ │

│ Battery Service (0x180F) │

│ Battery Level: 87% │

│ │

│ Custom Controller Service │

│ (UUID: 0000FF01-...) │

│ │

│ Buttons (Read/Notify) │

│ Value: 0x00 (none pressed) │

│ → Press Button A │

│ Value: 0x01 │

│ │

│ Joystick X (Read/Notify) │

│ Value: 128 (centered) │

│ → Move joystick right │

│ Value: 255 │

│ │

│ Joystick Y (Read/Notify) │

│ Value: 64 (pushed up) │

│ │

└────────────────────────────────┘

Serial Monitor Output:

$ pio device monitor

[2024-12-27 10:30:15] ESP32 BLE Controller v1.0

[2024-12-27 10:30:15] MAC Address: A4:CF:12:34:56:78

[2024-12-27 10:30:15] Initializing BLE stack...

[2024-12-27 10:30:15] GATT server created

[2024-12-27 10:30:15] Advertising name: "ESP32 GamePad"

[2024-12-27 10:30:15] Advertising started

[2024-12-27 10:30:23] BLE client connected: 6C:40:08:AA:BB:CC

[2024-12-27 10:30:23] MTU exchange: 512 bytes

[2024-12-27 10:30:24] Client subscribed to Buttons characteristic

[2024-12-27 10:30:24] Client subscribed to Joystick X characteristic

[2024-12-27 10:30:24] Client subscribed to Joystick Y characteristic

[2024-12-27 10:30:30] Button A pressed (GPIO 14)

[2024-12-27 10:30:30] Notifying client: Button=0x01

[2024-12-27 10:30:31] Button A released

[2024-12-27 10:30:31] Notifying client: Button=0x00

[2024-12-27 10:30:35] Joystick moved: X=255, Y=128 (right)

[2024-12-27 10:30:35] Notifying client: JoyX=255, JoyY=128

[2024-12-27 10:30:45] Battery level: 87% (3.85V)

[2024-12-27 10:35:10] Client disconnected

[2024-12-27 10:35:10] Restarting advertising...

Power consumption:

- Advertising: ~15mA

- Connected (idle): ~8mA

- Connected (active): ~12mA

- Estimated runtime on 1000mAh: ~80 hours

Real-World Usage Examples:

- Gaming on Android/iOS:

- Use apps like “BLE Gamepad” or “nRF Toolbox” to map your controller

- Play retro games (NES emulators) with your custom controller

- Lower latency than standard Bluetooth controllers (BLE can be sub-20ms)

- Media Remote:

- Control YouTube, Netflix, Spotify on your phone

- Button A = Play/Pause, Button B = Next, Joystick = Volume

- Presentation Clicker:

- Connect to laptop via BLE

- Button A = Next slide, Button B = Previous slide

- Joystick = Laser pointer simulation (if software supports it)

- Custom Computer Interface:

- Write a simple Python script using

bleaklibrary to receive BLE notifications - Map buttons to keyboard shortcuts (great for video editing, music production)

- Write a simple Python script using

Physical Interaction Experience:

You press Button A on your controller

↓

ESP32 GPIO interrupt fires (< 1ms)

↓

Debounce logic confirms real press (not noise)

↓

Update GATT characteristic value

↓

Send BLE notification to phone

↓

Phone receives notification (total latency: 15-30ms)

↓

Your game character jumps

BLE Scanner Output During Button Press:

Time: 10:30:30.125

Characteristic: Buttons (0xFF02)

Operation: Notification received

Value: 0x01 (binary: 00000001) → Button A pressed

Time: 10:30:31.340

Characteristic: Buttons (0xFF02)

Operation: Notification received

Value: 0x00 (binary: 00000000) → All buttons released

Impressive Demo Moment: Connect your controller to your phone, open a racing game, and drive using your custom-built joystick. Watch your friends ask “Wait, you BUILT that?” when they see the ESP32 circuit board responding in real-time with near-zero lag.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do you create a low-latency, battery-efficient wireless input device using BLE that feels as responsive as wired controllers?”

Before writing any code, understand this: BLE isn’t just “Bluetooth that uses less power”—it’s a fundamentally different protocol designed for intermittent, low-bandwidth communication. Unlike classic Bluetooth (which maintains constant audio/data streams), BLE sleeps between events and wakes up only when there’s something to transmit.

This project asks: how do you bridge the physical world (button presses, joystick movements) with the wireless world (BLE GATT protocol) while keeping latency low and battery life high?

This isn’t just about BLE—it’s about understanding:

- How to structure data for wireless transmission (GATT services/characteristics)

- How to handle asynchronous events (button interrupts vs. BLE connection events)

- How to balance responsiveness with power consumption

- How to debug invisible wireless protocols

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- BLE vs. Classic Bluetooth

- What’s the difference? (BLE: low power, connectionless; Classic: high bandwidth, audio)

- Why can’t you use classic Bluetooth for a game controller? (You can, but BLE is better for battery)

- What is a “connection interval” in BLE? (7.5ms to 4s between data exchanges)

- How does BLE achieve low power? (Sleeps between connection events, fast wakeup)

- Book Reference: “Getting Started with Bluetooth Low Energy” by Kevin Townsend - Chapter 1: “Introduction”

- BLE GATT (Generic Attribute Profile)

- What is the GATT hierarchy? (Services → Characteristics → Descriptors)

- What’s the difference between a Service and a Characteristic?

- What are the standard services? (Battery Service 0x180F, Device Information 0x180A)

- How do you create a custom service? (Use a 128-bit UUID)

- Book Reference: “Getting Started with Bluetooth Low Energy” by Kevin Townsend - Chapter 4: “GATT”

- GATT Characteristics Properties

- What does “Read” mean? (Client can request current value)

- What does “Write” mean? (Client can set a new value)

- What does “Notify” mean? (Server pushes updates to client without polling)

- Why is “Notify” critical for a controller? (Low latency, server-initiated)

- What’s the difference between “Notify” and “Indicate”? (Notify = no ack, Indicate = acknowledged)

- Book Reference: “Getting Started with Bluetooth Low Energy” by Kevin Townsend - Chapter 4: “GATT Operations”

- BLE Advertising

- What is advertising? (Broadcasting presence to nearby devices)

- What data is in an advertising packet? (Name, services, manufacturer data, flags)

- What is the advertising interval? (20ms to 10.24s between packets)

- How does a phone discover your ESP32? (Scans on channels 37, 38, 39)

- Book Reference: “Getting Started with Bluetooth Low Energy” by Kevin Townsend - Chapter 2: “Protocol Basics”

- Hardware Debouncing

- Why do mechanical buttons “bounce”? (Contacts vibrate when pressed, creating multiple signals)

- What does a bouncing signal look like? (Multiple HIGH/LOW transitions in ~10ms)

- How do you debounce in software? (Ignore transitions for 20-50ms after first press)

- Why are interrupts better than polling for buttons? (No CPU wasted checking in a loop)

- Book Reference: “The Art of Electronics” by Horowitz & Hill - Section 10.5: “Switch Debouncing”

- ADC (Analog-to-Digital Converter) for Joysticks

- How does a potentiometer (joystick axis) work? (Variable resistor, voltage divider)

- What is ADC resolution? (ESP32 has 12-bit ADC = 0-4095 range)

- Why do you get noise on ADC readings? (Electrical interference, ADC non-linearity)

- How do you filter noisy ADC values? (Moving average, hysteresis, calibration)

- Book Reference: “Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Edition” by Elecia White - Chapter 6: “Analog I/O”

- FreeRTOS Tasks and Priorities

- What is a task in FreeRTOS? (Independent thread of execution)

- What are task priorities? (Higher number = more important)

- Why separate BLE handling from button reading? (BLE stack needs consistent timing)

- How do tasks communicate? (Queues, semaphores, event groups)

- Book Reference: “Mastering the FreeRTOS Real Time Kernel” - Chapter 2: “Task Management”

- BLE Connection Parameters

- What is connection interval? (Time between data exchanges, e.g., 15ms)

- What is slave latency? (Number of events peripheral can skip)

- What is supervision timeout? (Time before connection declared dead)

- How do these affect latency and power? (Shorter interval = lower latency but higher power)

- Book Reference: “Getting Started with Bluetooth Low Energy” by Kevin Townsend - Chapter 3: “GAP”

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- GATT Service Design

- How many services do you need? (Battery + Custom Controller)

- How do you structure button data? (One characteristic with bitmask? Separate per button?)

- Should joystick X and Y be separate characteristics or combined? (Separate = easier client parsing)

- What size should characteristic values be? (1 byte for buttons, 1-2 bytes per joystick axis)

- Notification Strategy

- When do you send notifications? (On every button change? Throttled joystick updates?)

- What if joystick moves slightly due to noise? (Use deadzone, only notify on significant change)

- How often should you update battery level? (Every minute? Only when it changes by 5%?)

- What happens if client can’t keep up with notifications? (BLE stack buffers, but can overflow)

- Button Handling

- Should you use interrupts or polling? (Interrupts = lower latency)

- How long should debounce delay be? (20-50ms is typical)

- What if user presses multiple buttons simultaneously? (Bitmask handles this)

- Should you support long-press detection? (Adds complexity, but useful)

- Joystick Calibration

- How do you handle joystick that doesn’t center at exactly 2048? (Store center value in NVS)

- Should you auto-calibrate on startup? (Read resting position, assume it’s center)

- How big should the deadzone be? (5-10% around center to ignore drift)

- Do you need to smooth joystick values? (Yes, moving average of 4-8 samples)

- Power Optimization

- What’s the minimum connection interval you can use? (Trade latency for battery)

- Should you use light sleep between button presses? (BLE stack complicates this)

- How do you indicate low battery? (Update battery characteristic, flash LED)

- Can you reduce CPU frequency when idle? (240MHz → 80MHz saves power)

- User Experience

- How does user know controller is advertising? (LED blinks fast)

- How does user know controller is connected? (LED solid on)

- Should you have a “pairing button”? (Or auto-advertise on power-up)

- How do you handle disconnection? (Restart advertising automatically)

Thinking Exercise

Trace Button Press to BLE Notification By Hand

Before coding, trace this data flow on paper:

Step 1: Button Press (Physical → Electrical)

User presses Button A

↓

Mechanical contact closes

↓

GPIO 14 voltage: 3.3V → 0V (pulled low)

↓

Contacts bounce for ~10ms (multiple LOW/HIGH transitions)

↓

ESP32 GPIO interrupt fires multiple times

Step 2: Debouncing (Electrical → Software)

First interrupt at time T=0ms

↓

Set "button debounce timer" = 50ms

↓

Ignore all interrupts until T=50ms

↓

At T=50ms, read GPIO state

↓

If still LOW → Confirm real button press

↓

If HIGH → False alarm, ignore

Step 3: Update GATT Characteristic

Button A confirmed pressed

↓

Read current button bitmask: 0x00 (binary: 00000000)

↓

Set bit 0: 0x01 (binary: 00000001)

↓

Write to GATT characteristic "Buttons"

↓

Mark characteristic as "changed"

Step 4: BLE Notification

BLE stack checks: Is client subscribed to "Buttons" notifications?

↓

Yes → Prepare notification packet

↓

Packet contains: Handle=0x0042, Value=0x01

↓

Wait for next connection event (e.g., 15ms interval)

↓

Send notification to phone

↓

Phone receives and triggers callback in app

Step 5: Button Release

User releases Button A

↓

GPIO 14 voltage: 0V → 3.3V

↓

Interrupt fires (after debounce)

↓

Clear bit 0: 0x00 (binary: 00000000)

↓

Send notification: Value=0x00

Joystick Movement Flow:

User moves joystick right

↓

Potentiometer resistance changes

↓

ADC reads voltage: 2.5V (on 3.3V scale)

↓

ADC value: 2.5V / 3.3V * 4095 = 3100

↓

Apply deadzone: If |3100 - 2048| < 200, ignore (noise)

↓

3100 is outside deadzone → Significant movement

↓

Apply smoothing: Average of last 4 readings

↓

Scaled to 0-255: (3100 / 4095) * 255 = 193

↓

Update GATT characteristic "Joystick X" = 193

↓

Send notification to phone (if subscribed)

Questions while tracing:

- How long does the full button-press-to-notification flow take? (Debounce 50ms + connection interval 15ms ≈ 65ms)

- What if connection interval is 100ms? (Total latency becomes 150ms—feels sluggish)

- How often should you sample the joystick? (100Hz = every 10ms is smooth for gaming)

- If you send joystick updates every 10ms, but connection interval is 50ms, what happens? (BLE stack buffers them, sends 5 at once)

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “Explain the difference between BLE and classic Bluetooth.”

- Expected: BLE = low power, connectionless, smaller packets; Classic = audio/data streaming, higher bandwidth

- “What is GATT, and how do services and characteristics relate?”

- Expected: GATT = data structure; Service groups related characteristics; Characteristic holds actual data with read/write/notify properties

- “How does BLE Notify differ from Read?”

- Expected: Notify = server pushes data to client (low latency); Read = client polls server (wastes power, higher latency)

- “Why do you need to debounce buttons?”

- Expected: Mechanical contacts bounce, creating false triggers; debounce filters these out with time delay

- “How do you reduce power consumption in a BLE controller?”

- Expected: Increase connection interval, use notifications instead of polling, sleep between events, reduce CPU frequency

- “What’s the purpose of a deadzone on a joystick?”

- Expected: Prevents jitter when joystick is at rest; ignores small movements due to electrical noise or mechanical drift

- “How do you handle multiple buttons pressed simultaneously?”

- Expected: Use a bitmask (e.g., 0x03 = buttons A and B both pressed)

- “What happens if a BLE notification fails to send?”

- Expected: BLE doesn’t guarantee delivery for notifications (unlike indications); if connection is lost, notification is dropped

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with BLE Advertising

Get your ESP32 discoverable on your phone:

#include "esp_bt.h"

#include "esp_gap_ble_api.h"

#include "esp_gatts_api.h"

#include "esp_bt_main.h"

static uint8_t adv_data[] = {

0x02, 0x01, 0x06, // Flags: LE General Discoverable, BR/EDR not supported

0x0D, 0x09, 'E', 'S', 'P', '3', '2', ' ', 'G', 'a', 'm', 'e', 'P', 'a', 'd' // Complete local name

};

void start_advertising() {

esp_ble_gap_config_adv_data_raw(adv_data, sizeof(adv_data));

esp_ble_adv_params_t adv_params = {

.adv_int_min = 0x20, // 20ms

.adv_int_max = 0x40, // 40ms

.adv_type = ADV_TYPE_IND,

.own_addr_type = BLE_ADDR_TYPE_PUBLIC,

.channel_map = ADV_CHNL_ALL,

.adv_filter_policy = ADV_FILTER_ALLOW_SCAN_ANY_CON_ANY,

};

esp_ble_gap_start_advertising(&adv_params);

}

void app_main() {

esp_bt_controller_config_t bt_cfg = BT_CONTROLLER_INIT_CONFIG_DEFAULT();

esp_bt_controller_init(&bt_cfg);

esp_bt_controller_enable(ESP_BT_MODE_BLE);

esp_bluedroid_init();

esp_bluedroid_enable();

start_advertising();

printf("Advertising as 'ESP32 GamePad'\n");

}

Test: Open nRF Connect app on phone, scan, and you should see “ESP32 GamePad”.

Hint 2: Create GATT Service with Button Characteristic

#define GATTS_SERVICE_UUID 0x00FF // Custom service

#define GATTS_CHAR_UUID_BUTTON 0xFF01 // Button characteristic

static uint8_t button_value = 0x00; // Bitmask: bit 0=ButtonA, bit 1=ButtonB, etc.

// GATT attribute database

static const uint16_t primary_service_uuid = ESP_GATT_UUID_PRI_SERVICE;

static const uint16_t character_declaration_uuid = ESP_GATT_UUID_CHAR_DECLARE;

static const uint16_t character_client_config_uuid = ESP_GATT_UUID_CHAR_CLIENT_CONFIG;

static const uint8_t char_prop_read_notify = ESP_GATT_CHAR_PROP_BIT_READ | ESP_GATT_CHAR_PROP_BIT_NOTIFY;

// Service definition

static const esp_gatts_attr_db_t gatt_db[4] = {

// Service Declaration

[0] = {

{ESP_GATT_AUTO_RSP},

{ESP_UUID_LEN_16, (uint8_t *)&primary_service_uuid, ESP_GATT_PERM_READ, sizeof(uint16_t), sizeof(GATTS_SERVICE_UUID), (uint8_t *)&GATTS_SERVICE_UUID}

},

// Button Characteristic Declaration

[1] = {

{ESP_GATT_AUTO_RSP},

{ESP_UUID_LEN_16, (uint8_t *)&character_declaration_uuid, ESP_GATT_PERM_READ, sizeof(uint8_t), sizeof(uint8_t), (uint8_t *)&char_prop_read_notify}

},

// Button Characteristic Value

[2] = {

{ESP_GATT_AUTO_RSP},

{ESP_UUID_LEN_16, (uint8_t *)&GATTS_CHAR_UUID_BUTTON, ESP_GATT_PERM_READ, sizeof(button_value), sizeof(button_value), (uint8_t *)&button_value}

},

// Client Characteristic Configuration Descriptor (for notifications)

[3] = {

{ESP_GATT_AUTO_RSP},

{ESP_UUID_LEN_16, (uint8_t *)&character_client_config_uuid, ESP_GATT_PERM_READ | ESP_GATT_PERM_WRITE, sizeof(uint16_t), 0, NULL}

},

};

// Create attribute table

esp_ble_gatts_create_attr_tab(gatt_db, gatts_if, 4, 0);

Test: In nRF Connect, connect and you should see service 0x00FF with characteristic 0xFF01.

Hint 3: Add Button Interrupt Handler with Debounce

#define BUTTON_A_PIN 14

#define DEBOUNCE_TIME_MS 50

static uint32_t last_button_time = 0;

void IRAM_ATTR button_isr_handler(void* arg) {

uint32_t now = xTaskGetTickCountFromISR() * portTICK_PERIOD_MS;

// Debounce: Ignore if less than 50ms since last interrupt

if (now - last_button_time < DEBOUNCE_TIME_MS) {

return;

}

last_button_time = now;

// Read button state

bool pressed = (gpio_get_level(BUTTON_A_PIN) == 0); // Active low

// Update bitmask

if (pressed) {

button_value |= 0x01; // Set bit 0

} else {

button_value &= ~0x01; // Clear bit 0

}

// Notify connected clients (handled in main loop)

button_changed = true;

}

void setup_buttons() {

gpio_config_t io_conf = {

.intr_type = GPIO_INTR_ANYEDGE, // Trigger on both press and release

.mode = GPIO_MODE_INPUT,

.pin_bit_mask = (1ULL << BUTTON_A_PIN),

.pull_up_en = 1, // Enable internal pull-up

};

gpio_config(&io_conf);

gpio_install_isr_service(0);

gpio_isr_handler_add(BUTTON_A_PIN, button_isr_handler, (void*) BUTTON_A_PIN);

}

Hint 4: Send BLE Notification on Button Change

static uint16_t button_handle; // Handle from GATT attr table

static uint16_t conn_id;

static esp_gatt_if_t gatts_if;

void send_button_notification() {

if (conn_id != 0xFFFF) { // Check if client is connected

esp_ble_gatts_send_indicate(gatts_if, conn_id, button_handle,

sizeof(button_value), &button_value, false);

printf("Notified: Buttons=0x%02X\n", button_value);

}

}

void app_main() {

// ... (BLE init from Hint 1)

setup_buttons();

while (1) {

if (button_changed) {

send_button_notification();

button_changed = false;

}

vTaskDelay(10 / portTICK_PERIOD_MS);

}

}

Test: Press button, watch serial monitor show “Notified”, check nRF Connect shows updated value.

Hint 5: Add Joystick with ADC

#include "driver/adc.h"

#define JOYSTICK_X_PIN ADC1_CHANNEL_6 // GPIO34

#define JOYSTICK_Y_PIN ADC1_CHANNEL_7 // GPIO35

static uint8_t joystick_x = 128; // 0-255, 128=center

static uint8_t joystick_y = 128;

void setup_joystick() {

adc1_config_width(ADC_WIDTH_BIT_12); // 0-4095

adc1_config_channel_atten(JOYSTICK_X_PIN, ADC_ATTEN_DB_11); // Full 0-3.3V range

adc1_config_channel_atten(JOYSTICK_Y_PIN, ADC_ATTEN_DB_11);

}

void read_joystick() {

// Read ADC (0-4095)

int raw_x = adc1_get_raw(JOYSTICK_X_PIN);

int raw_y = adc1_get_raw(JOYSTICK_Y_PIN);

// Apply deadzone (center ± 200)

int center = 2048;

int deadzone = 200;

if (abs(raw_x - center) < deadzone) {

raw_x = center;

}

if (abs(raw_y - center) < deadzone) {

raw_y = center;

}

// Scale to 0-255

joystick_x = (raw_x * 255) / 4095;

joystick_y = (raw_y * 255) / 4095;

// Send notifications if changed significantly

static uint8_t last_x = 128, last_y = 128;

if (abs(joystick_x - last_x) > 5 || abs(joystick_y - last_y) > 5) {

send_joystick_notification();

last_x = joystick_x;

last_y = joystick_y;

}

}

void app_main() {

setup_joystick();

while (1) {

read_joystick();

vTaskDelay(10 / portTICK_PERIOD_MS); // Sample at 100Hz

}

}

Hint 6: Add Battery Level Service

#define BATTERY_SERVICE_UUID 0x180F

#define BATTERY_LEVEL_CHAR_UUID 0x2A19

static uint8_t battery_level = 100; // 0-100%

void read_battery_level() {

// Read battery voltage (assuming voltage divider on GPIO36)

int raw = adc1_get_raw(ADC1_CHANNEL_0); // GPIO36

float voltage = (raw / 4095.0) * 3.3 * 2; // *2 if using voltage divider

// LiPo: 4.2V=100%, 3.0V=0%

battery_level = ((voltage - 3.0) / (4.2 - 3.0)) * 100;

battery_level = (battery_level > 100) ? 100 : battery_level;

battery_level = (battery_level < 0) ? 0 : battery_level;

printf("Battery: %d%% (%.2fV)\n", battery_level, voltage);

}

// Update battery every 60 seconds

void battery_task(void* param) {

while (1) {

read_battery_level();

send_battery_notification();

vTaskDelay(60000 / portTICK_PERIOD_MS);

}

}

Hint 7: Optimize Connection Parameters for Low Latency

void connection_event_handler(esp_gatts_cb_event_t event, esp_gatt_if_t gatts_if, esp_ble_gatts_cb_param_t *param) {

if (event == ESP_GATTS_CONNECT_EVT) {

conn_id = param->connect.conn_id;

// Request lower connection interval for lower latency

esp_ble_conn_update_params_t conn_params = {

.bda = {0}, // Will be filled

.min_int = 0x06, // 7.5ms (units of 1.25ms)

.max_int = 0x0C, // 15ms

.latency = 0, // No slave latency

.timeout = 400, // 4s supervision timeout

};

memcpy(conn_params.bda, param->connect.remote_bda, sizeof(esp_bd_addr_t));

esp_ble_gap_update_conn_params(&conn_params);

printf("Client connected, requesting low-latency params\n");

}

}

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| BLE protocol fundamentals | “Getting Started with Bluetooth Low Energy” by Kevin Townsend | Ch. 1-4: BLE basics, GAP, GATT |

| GATT services and characteristics | “Getting Started with Bluetooth Low Energy” by Kevin Townsend | Ch. 4: “GATT” (profiles, services, characteristics) |

| BLE advertising and discovery | “Getting Started with Bluetooth Low Energy” by Kevin Townsend | Ch. 2: “Protocol Basics”, Ch. 3: “GAP” |

| Hardware debouncing | “The Art of Electronics” by Horowitz & Hill | Section 10.5: “Switch Debouncing” |

| ADC and analog input | “Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Edition” by Elecia White | Ch. 6: “Getting Your Hands Dirty” (Analog I/O) |

| FreeRTOS task management | “Mastering the FreeRTOS Real Time Kernel” | Ch. 2: “Task Management”, Ch. 7: “Queues” |

| GPIO interrupts on ESP32 | “ESP-IDF Programming Guide - GPIO & RTC GPIO” | Espressif official docs (online) |

| BLE on ESP32 | “ESP-IDF Programming Guide - Bluetooth” | Espressif official docs, GATT server examples |

| Low-power BLE design | “Getting Started with Bluetooth Low Energy” by Kevin Townsend | Ch. 7: “Low-Power Design” |

| Embedded input devices | “Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Edition” by Elecia White | Ch. 6: “Digital and Analog I/O” |

Project 3: Multi-Sensor Data Logger with Deep Sleep

- File: multi_sensor_data_logger_esp32.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: MicroPython, Rust, Arduino C++

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: Level 3: The “Service & Support” Model

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced (The Engineer)

- Knowledge Area: Embedded Systems, Power Management, RTC, ESP-NOW

- Software or Tool: ESP-IDF, ESP32

- Main Book: Making Embedded Systems by Elecia White

What you’ll build: A battery-powered remote sensor node that wakes up periodically, reads sensors, transmits data over WiFi or ESP-NOW, then goes back to deep sleep—lasting weeks on a single battery.

Why it teaches ESP32: This project confronts you with the hardest embedded challenge: power management. You’ll learn deep sleep modes, RTC memory persistence, wake-up sources, and the trade-offs between connectivity and battery life.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Configuring deep sleep and various wake-up sources (timer, GPIO, touch) (maps to power management)

- Preserving data across sleep cycles using RTC memory (maps to memory architecture)

- Fast WiFi reconnection to minimize awake time (maps to wireless optimization)

- Choosing between WiFi vs ESP-NOW for power efficiency (maps to protocol trade-offs)

Key Concepts:

- ESP32 Sleep Modes: “ESP-IDF Programming Guide - Sleep Modes” - Espressif official docs

- RTC Memory: “ESP32 Technical Reference Manual” - Chapter on RTC

- Low-Power Design: “Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Edition” by Elecia White - Chapter 11

- ESP-NOW Protocol: “IoT Product Development Using ESP32 Microcontrollers” by Sai Yamanoor - ESP-NOW section

Difficulty: Intermediate-Advanced Time estimate: 2-3 weeks Prerequisites: Comfortable with WiFi programming, understand basic power concepts

Real world outcome:

- A sensor node you can place in your garden, garage, or mailbox

- Runs for 2-4 weeks on a small battery

- Data appears on a central hub or cloud service

Learning milestones:

- Milestone 1: Device sleeps and wakes on timer—you understand deep sleep basics

- Milestone 2: Data survives sleep cycles—you understand RTC memory

- Milestone 3: Device runs 2+ weeks on battery—you’ve mastered power optimization

Real World Outcome

You’ll build a battery-powered IoT sensor node that demonstrates professional-grade power management. Here’s exactly what you’ll experience:

Physical Setup:

- ESP32 DevKit or custom PCB powered by a 3.7V 2000mAh LiPo battery or 3x AA batteries (4.5V)

- BME280 sensor (temperature, humidity, pressure) or DHT22

- Optional: soil moisture sensor, light sensor (BH1750), or PIR motion sensor

- Optional: TP4056 charging module for LiPo battery

- All components in a weatherproof enclosure

Power Consumption Measurements (these are the numbers that matter):

Active Mode (WiFi transmitting):

- Current draw: 160-260mA

- Duration per cycle: 2-4 seconds

- Power: ~0.6-1.0 Wh per transmission

Deep Sleep Mode:

- Current draw: 10-150μA (microamps!)

- ESP32 DevKit with voltage regulator: ~10-15mA (poor!)

- ESP32 bare module (custom PCB): 10-150μA (excellent!)

- Wake-up sources remain active (RTC timer, GPIO, touchpad)

Modem Sleep Mode (WiFi off, CPU running):

- Current draw: 20-30mA

- Useful for: processing between transmissions

Battery Life Calculations (with 2000mAh LiPo):

Scenario 1: Wake every 5 minutes, WiFi transmission (worst case with DevKit)

- Sleep current: 10mA × 295 seconds = 0.82mAh per cycle

- Active current: 200mA × 5 seconds = 0.28mAh per cycle

- Total per cycle: 1.1mAh

- Cycles per day: 288 (24h × 12 per hour)

- Daily consumption: 316.8mAh

- Battery life: 2000mAh / 316.8mAh = 6.3 days

Scenario 2: Wake every 15 minutes, ESP-NOW transmission (optimized bare module)

- Sleep current: 100μA × 895 seconds = 0.025mAh per cycle

- Active current: 180mA × 5 seconds = 0.25mAh per cycle

- Total per cycle: 0.275mAh

- Cycles per day: 96 (24h × 4 per hour)

- Daily consumption: 26.4mAh

- Battery life: 2000mAh / 26.4mAh = 75 days (2.5 months!)

Scenario 3: Wake on GPIO interrupt (door sensor), ESP-NOW

- Sleep current: 100μA continuous = 2.4mAh per day

- Active only when triggered: assume 10 triggers/day × 0.25mAh = 2.5mAh

- Daily consumption: 4.9mAh

- Battery life: 2000mAh / 4.9mAh = 408 days (13+ months!)

Serial Monitor Output (Debug Mode):

$ pio device monitor

[Boot #1] ESP32 Wake Stub - Deep Sleep Logger

==================================================

Wake cause: RESET (first boot)

RTC Memory: Initializing boot count = 0

Battery voltage: 4.12V (ADC: 3250)

Sensor readings:

- Temperature: 22.4°C

- Humidity: 48%

- Pressure: 1013.2 hPa

- Soil Moisture: 65% (ADC: 2100)

WiFi connecting to "HomeNetwork"...

WiFi connected in 1.8s (IP: 192.168.1.205)

MQTT connecting to 192.168.1.100:1883...

MQTT connected in 0.3s

Publishing to topic: sensors/garden/data

{"temp":22.4,"hum":48,"press":1013.2,"soil":65,"bat":4.12,"boot":0}

MQTT publish successful

Total awake time: 2.1 seconds

Current draw during cycle: ~200mA

Energy consumed: 0.12 Wh

Entering deep sleep for 900 seconds (15 minutes)

Next wake at: 2024-12-27 16:30:00

==================================================

[Boot #2] ESP32 Wake Stub - Deep Sleep Logger

Wake cause: TIMER (15 min elapsed)

RTC Memory: Boot count = 1, last_temp = 22.4

Battery voltage: 4.11V (ADC: 3245)

Sensor readings:

- Temperature: 22.5°C (+0.1°C from last)

- Humidity: 47% (-1%)

[... repeats every 15 minutes ...]

[Boot #50]

Wake cause: TIMER

RTC Memory: Boot count = 49

Battery voltage: 3.89V (ADC: 3080) [WARNING: Battery below 4.0V]

Sensor readings:

- Temperature: 18.2°C

[Data published successfully]

Entering deep sleep for 900 seconds

==================================================

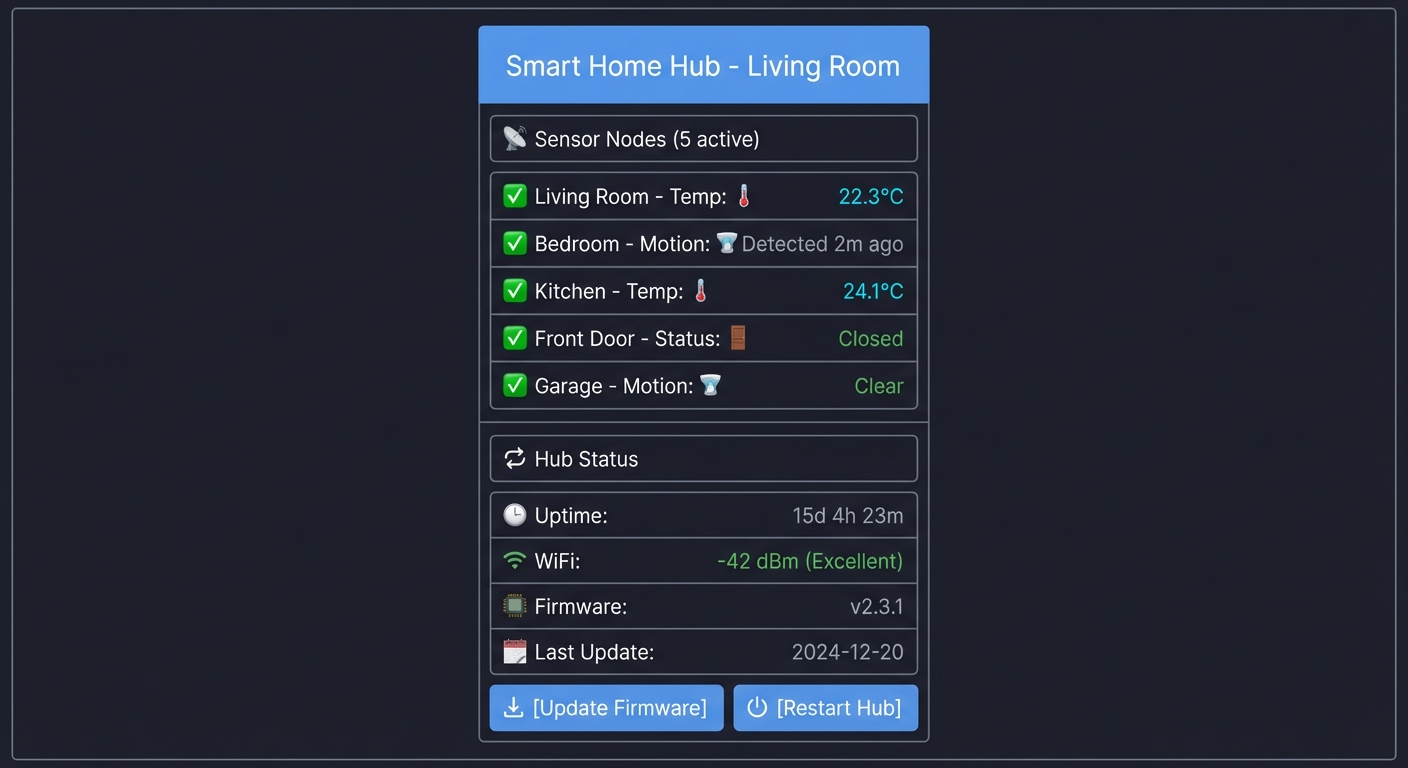

What You’ll See on Your Monitoring Dashboard (MQTT/Home Assistant):

Garden Sensor Node

├─ Temperature: 18.2°C (updated 2m ago)

├─ Humidity: 52%

├─ Pressure: 1015.8 hPa

├─ Soil Moisture: 42% [ALERT: Water needed]

├─ Battery: 3.89V (78%) [WARNING: Low battery]

├─ Signal Strength: -68 dBm

├─ Uptime: 12d 8h (867 wake cycles)

└─ Last Seen: 2024-12-27 16:45:00

[Graph showing 7-day temperature trend]

Impressive Demo Moment: Place the sensor node in your garden. Over 2 weeks, watch it reliably report soil moisture, temperature, and humidity every 15 minutes. When the battery drops below 20%, receive a notification. The device runs for 60+ days on a single charge—something impossible without deep sleep mastery.

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do you design an IoT sensor node that runs for months on battery while maintaining reliable wireless communication and data integrity?”

Before writing any code, understand this: Most embedded developers can make an ESP32 read a sensor and send data over WiFi. That’s trivial. The hard part is doing it on battery power for extended periods. This requires understanding:

- Energy budgeting: Every milliamp-hour counts. Can you afford WiFi, or must you use ESP-NOW? Can you sample every minute, or only every hour?

- State persistence: When the CPU is powered off (deep sleep), how do you preserve application state? What if you’re mid-transmission when battery dies?

- Reliability vs efficiency trade-offs: Fast WiFi connection uses more power. Retrying failed transmissions drains battery. How do you balance robustness with longevity?

- Hardware considerations: Not all ESP32 boards are created equal. A DevKit with onboard voltage regulator wastes 10-15mA even in deep sleep. A bare module gets down to 10μA—a 1000x difference!

This project separates hobbyist “proof of concepts” from production-ready IoT devices.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- ESP32 Sleep Modes (Light Sleep, Modem Sleep, Deep Sleep, Hibernation)

- What parts of the chip remain powered in each mode?

- What’s the difference between deep sleep (10-150μA) and light sleep (0.8-1.1mA)?

- What is Hibernation mode? (Ultra-low power but limited wake sources)

- Which peripherals continue running during sleep? (RTC timer, ULP coprocessor, touch sensors)

- Book Reference: “Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Edition” by Elecia White - Chapter 11: “Optimizing Power and Performance”

- RTC (Real-Time Clock) Memory and Peripherals

- ESP32 has two types of RTC memory: Fast (8KB) and Slow (8KB). What’s the difference?

- What is the RTC_DATA_ATTR attribute? How do you preserve variables across reboots?

- What is the ULP (Ultra-Low-Power) coprocessor? When should you use it?

- How accurate is the RTC timer? (Calibration needed for long sleep periods)

- Book Reference: “ESP32 Technical Reference Manual” - Chapter 28: “RTC and Low-Power Management”

- Power Consumption Analysis

- How do you measure current draw? (Use a multimeter in series, or INA219 breakout board)

- What is quiescent current? (Current consumed by voltage regulators even when ESP32 sleeps)

- Why do DevKit boards have high sleep current? (Onboard components: USB-to-serial chip, LEDs, voltage regulator)

- How do you calculate battery life from mAh capacity and average current draw?

- Book Reference: “Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Edition” by Elecia White - Chapter 11: “Measuring Power Consumption”

- Wake-Up Sources and Stubs

- What wake-up sources exist? (Timer, GPIO ext0/ext1, touchpad, ULP, WiFi, BT)

- What is a wake stub? (Code that runs immediately after wake, before full boot)

- Why use a wake stub? (Decide whether to fully wake or go back to sleep)

- How do you determine wake cause? (esp_sleep_get_wakeup_cause())

- Book Reference: “ESP-IDF Programming Guide - Sleep Modes” - Espressif official docs

- Non-Volatile Storage (NVS vs Flash vs RTC Memory)

- When should you use NVS? (Configuration, calibration data, counters)

- When should you use RTC memory? (State that must survive sleep but not full reboot)

- When should you write to flash? (Logged data before transmitting)

- What is flash wear leveling? Why does it matter?

- Book Reference: “Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Edition” by Elecia White - Chapter 7: “Memory Management”

- WiFi Fast Connect and Connection Optimization

- Normal WiFi connection takes 2-5 seconds. How can you reduce this?

- What is WiFi channel caching? (Store last-used channel in RTC memory)

- What is BSSID caching? (Connect directly to known access point MAC)

- Should you use DHCP or static IP? (Static is faster—no negotiation)

- Book Reference: “ESP-IDF Programming Guide - WiFi” - Espressif official docs, “WiFi Power Save Mode”

- ESP-NOW vs WiFi for Low Power

- Why is ESP-NOW more power-efficient than WiFi?

- ESP-NOW connection time: ~10-50ms. WiFi connection time: 2-5 seconds.

- ESP-NOW requires a hub. When is this trade-off worth it?

- Can you use ESP-NOW without WiFi initialization? (Yes! Major power savings)

- Book Reference: “IoT Product Development Using ESP32 Microcontrollers” by Sai Yamanoor - Chapter on ESP-NOW

- Battery Management and Voltage Monitoring

- How do you measure battery voltage with ESP32 ADC?

- Why must you use a voltage divider? (Battery voltage may exceed ADC max 3.3V)

- How do you detect “low battery” and prevent deep discharge?

- What is battery voltage sag? (Voltage drops under load, recovers at rest)

- Book Reference: “Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Edition” by Elecia White - Chapter 11: “Battery Considerations”

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Power Budget and Wake Frequency

- What’s your target battery life? (1 week? 1 month? 6 months?)

- What battery capacity are you working with? (2000mAh? 500mAh?)

- How often must you sample? (Every minute? Every 15 minutes? Every hour?)

- What’s the trade-off between data granularity and battery life?

- Wake Source Selection

- Should you wake on timer, or does your application need event-based waking? (PIR motion sensor)

- If using timer, what interval balances battery life with data freshness?

- For GPIO wake, does your sensor support holding a line HIGH until acknowledged?

- Could ULP coprocessor pre-filter sensor data to avoid unnecessary wake-ups?

- Communication Protocol Choice

- WiFi: Longer connection time (2-5s), works with existing router, reaches cloud directly

- ESP-NOW: Very fast (10-50ms), requires hub device, mesh-capable

- Which protocol fits your power budget?

- Can you batch multiple sensor readings before transmitting?

- Data Persistence Strategy

- What data must survive deep sleep? (Boot count, last sensor value, transmission failures)

- Use RTC memory for frequently changing state (fast, volatile across full reboot)

- Use NVS for configuration (persistent, slower writes)

- Should you log data to flash and transmit in batches? (More reliable but complex)

- Error Handling and Reliability

- What if WiFi connection fails? (Retry? Store data locally and try next cycle?)

- What if transmission fails? (Queue data? Discard? Set a “failed_tx” flag?)

- What if battery dies mid-transmission? (Data could corrupt; use atomic writes)

- Should you implement a “safety wake” to prevent infinite sleep?

- Hardware Optimization

- Are you using a DevKit board? (Expect 10-15mA sleep current due to regulators)

- Can you remove the power LED? (Saves 1-5mA)

- Can you use a bare ESP32 module on custom PCB? (Achieves 10-150μA sleep current)

- Do your sensors support sleep modes? (BME280 has low-power mode; DHT22 draws power continuously)

Thinking Exercise

Trace a Complete Wake-Sleep Cycle By Hand

Before coding, trace this scenario on paper:

Setup: ESP32 with BME280 sensor, 2000mAh battery, 15-minute wake interval, WiFi transmission

Step 1: Deep Sleep State (14 minutes 55 seconds)

All CPU cores: OFF

Main RAM: LOST

WiFi/Bluetooth radio: OFF

Most peripherals: OFF

Still powered:

- RTC slow memory (8KB): Contains boot_count, last_temp

- RTC fast memory (8KB): Contains wake stub code

- RTC timer: Counting microseconds until wake time

- GPIO wake circuits: Monitoring for ext0/ext1 triggers

Current draw: 100μA (bare module) or 10mA (DevKit)

Energy consumed: 100μA × 895s = 0.025mAh (bare) or 2.5mAh (DevKit)

Step 2: Wake Event (Timer expires)

RTC timer reaches 900,000,000 microseconds (15 minutes)

↓

Hardware wake interrupt fires

↓

If wake stub exists: Execute wake stub code (optional fast decision)

↓

Otherwise: Begin full boot sequence

↓

CPU cores power up

↓

Main RAM initializes (all variables reset to initial values!)

↓

Bootloader loads app code from flash

↓

app_main() starts

Step 3: Determine Wake Cause (first thing in code)

esp_sleep_wakeup_cause_t wake_cause = esp_sleep_get_wakeup_cause();

switch(wake_cause) {

case ESP_SLEEP_WAKEUP_TIMER:

printf("Woke from timer\n");

break;

case ESP_SLEEP_WAKEUP_EXT0:

printf("Woke from GPIO\n");

break;

case ESP_SLEEP_WAKEUP_UNDEFINED:

printf("First boot (power-on reset)\n");

break;

}

Step 4: Restore State from RTC Memory

RTC_DATA_ATTR uint32_t boot_count = 0; // Survives deep sleep!

RTC_DATA_ATTR float last_temperature = 0;

boot_count++; // Increment across sleep cycles

printf("Boot #%d, last temp: %.1f\n", boot_count, last_temperature);

Step 5: Read Sensors (200ms)

Initialize I2C bus

↓

Wake BME280 from sleep mode

↓

Trigger measurement (forced mode)

↓

Wait for conversion (~10ms)

↓

Read temperature, humidity, pressure registers

↓

Put BME280 back to sleep mode

↓

Current draw during sensor read: ~15mA

Step 6: Connect WiFi (2-5 seconds, most power-hungry!)

WiFi initialization

↓

Scan for known SSID (or use cached channel)

↓

Association with AP (4-way handshake)

↓

DHCP request (or use static IP—faster!)

↓

DNS resolution (if using hostname)

↓

Current draw: 160-260mA (peak 350mA during TX bursts)

Step 7: Transmit Data (500ms)

MQTT/HTTP connection established

↓

Publish sensor data: {"temp":22.4,"hum":48,"bat":4.12,"boot":867}

↓

Wait for acknowledgment

↓

Close connection cleanly

↓

WiFi disconnect

Step 8: Store State and Enter Sleep (100ms)

Update RTC variables:

last_temperature = current_temperature;

boot_count++;

Write critical data to NVS (if needed):

nvs_set_u32(handle, "total_boots", boot_count);

Configure wake source:

esp_sleep_enable_timer_wakeup(15 * 60 * 1000000ULL); // 15 min

Optional: Configure GPIO wake for emergency override

esp_sleep_enable_ext0_wakeup(GPIO_NUM_33, 1);

Enter deep sleep:

esp_deep_sleep_start(); ← Code execution stops here!

Total Awake Time: 2.1-5.2 seconds Energy Consumed: 200mA × 5s = 0.28mAh

Questions while tracing:

- Why is WiFi the power bottleneck? (Radio transmit power is high: 160-260mA)

- Could you reduce WiFi connection time? (Cache channel, use static IP, reduce TX power)

- What happens to local variables during deep sleep? (Completely lost! Only RTC_DATA_ATTR survives)

- How would this change with ESP-NOW instead of WiFi? (Connection time drops to ~50ms; massive power savings)

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “Explain the difference between light sleep, modem sleep, and deep sleep on ESP32.”

- Expected: Light sleep (CPU pauses, RAM retained, 0.8mA), Modem sleep (WiFi off, CPU on, 20-30mA), Deep sleep (most systems off, RTC only, 10-150μA)

- “How do you preserve data across deep sleep cycles?”

- Expected: Use RTC_DATA_ATTR for variables, NVS for persistent config, or log to flash

- “Why does an ESP32 DevKit have higher sleep current than a bare module?”

- Expected: Onboard voltage regulator quiescent current, USB-UART chip, LEDs—all draw power even when ESP32 sleeps

- “Calculate battery life: 2000mAh battery, wake every 10 minutes, 3-second WiFi transmission at 200mA, 100μA sleep current.”

- Expected: Sleep: 100μA × 597s = 0.017mAh. Active: 200mA × 3s = 0.17mAh. Total per cycle: 0.187mAh. Cycles/day: 144. Daily: 26.9mAh. Life: 74 days.

- “What is the ULP coprocessor and when should you use it?”

- Expected: Ultra-low-power coprocessor that runs while main CPU sleeps; use for continuous monitoring (temperature threshold detection) to wake main CPU only when needed

- “How would you implement a door sensor that wakes on open/close?”

- Expected: Use esp_sleep_enable_ext0_wakeup() with reed switch on GPIO; ESP32 wakes on edge, reads state, transmits, returns to sleep

- “Why is ESP-NOW more power-efficient than WiFi for sensor nodes?”

- Expected: No AP association (saves 2-5s), connectionless (no handshake), peer-to-peer (lower latency)

- “What happens if battery dies mid-transmission?”

- Expected: Data could be lost or corrupt; use atomic writes to NVS, or implement “pending transmission” flag

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with Basic Deep Sleep

Get the sleep-wake cycle working before adding sensors or WiFi:

#include "esp_sleep.h"

RTC_DATA_ATTR int boot_count = 0;

void app_main() {

boot_count++;

printf("Boot number: %d\n", boot_count);

printf("Entering deep sleep for 10 seconds...\n");

esp_sleep_enable_timer_wakeup(10 * 1000000); // 10 seconds in microseconds

esp_deep_sleep_start();

// Code after this line never executes!

}

Test: Flash this code. Serial monitor should show boot count incrementing every 10 seconds. Measure current with multimeter—should see ~10-15mA on DevKit.

Hint 2: Add RTC Memory Persistence

RTC_DATA_ATTR uint32_t boot_count = 0;

RTC_DATA_ATTR float last_temperature = 0;

RTC_DATA_ATTR uint32_t failed_transmissions = 0;

void app_main() {

boot_count++;

// Check wake cause

esp_sleep_wakeup_cause_t wake_cause = esp_sleep_get_wakeup_cause();

switch(wake_cause) {

case ESP_SLEEP_WAKEUP_TIMER:

printf("Woke from timer (boot #%d)\n", boot_count);

break;

case ESP_SLEEP_WAKEUP_EXT0:

printf("Woke from GPIO (external trigger)\n");

break;

case ESP_SLEEP_WAKEUP_UNDEFINED:

printf("First boot or hard reset\n");

boot_count = 0;

break;

}

printf("Previous temperature: %.1f\n", last_temperature);

// Configure wake sources

esp_sleep_enable_timer_wakeup(15 * 60 * 1000000ULL); // 15 minutes

esp_sleep_enable_ext0_wakeup(GPIO_NUM_33, 1); // Wake on GPIO 33 HIGH

esp_deep_sleep_start();

}

Hint 3: Add Sensor Reading

#include "driver/i2c.h"

#include "bme280.h" // Use a BME280 library

RTC_DATA_ATTR uint32_t boot_count = 0;

void read_sensors(float *temp, float *hum, float *press) {

// Initialize I2C

i2c_config_t conf = {

.mode = I2C_MODE_MASTER,

.sda_io_num = 21,

.scl_io_num = 22,

.sda_pullup_en = GPIO_PULLUP_ENABLE,

.scl_pullup_en = GPIO_PULLUP_ENABLE,

.master.clk_speed = 100000,

};

i2c_param_config(I2C_NUM_0, &conf);

i2c_driver_install(I2C_NUM_0, I2C_MODE_MASTER, 0, 0, 0);

// Wake BME280 and read

bme280_init();

bme280_read_float(temp, hum, press);

// Put sensor back to sleep

bme280_set_sleep_mode();

// Clean up I2C (saves power)

i2c_driver_delete(I2C_NUM_0);

}

void app_main() {

boot_count++;

float temperature, humidity, pressure;

read_sensors(&temperature, &humidity, &pressure);

printf("Boot #%d: Temp=%.1f°C, Hum=%.1f%%, Press=%.1fhPa\n",

boot_count, temperature, humidity, pressure);

esp_sleep_enable_timer_wakeup(15 * 60 * 1000000ULL);

esp_deep_sleep_start();

}

Hint 4: Add Fast WiFi Connection and Transmission

(See full WiFi code in PROJECT_3_ENHANCEMENT.md)

Hint 5: Measure Battery Voltage

(See full battery monitoring code in PROJECT_3_ENHANCEMENT.md)

Hint 6: Use ESP-NOW for Extreme Power Efficiency

(See full ESP-NOW code in PROJECT_3_ENHANCEMENT.md - achieves 50-100x power savings!)

Hint 7: Implement Graceful Degradation

(See full graceful degradation code in PROJECT_3_ENHANCEMENT.md)

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|