categories: [algorithms-data-structures, systems-programming] —

Learning Data Structures: From First Principles

Goal: Build a memory-level understanding of data structures so you can predict performance, design trade-offs, and failure modes before you code. You will learn how structures map to cache lines, pointers, and allocation strategies, and you will see how those choices change real runtime behavior. By the end, you can choose the right structure for the workload, justify it in plain language, and implement it from scratch in C. You will also connect each structure to real systems: schedulers, databases, graphs, and caches.

Why Data Structures Matter (With Real-World Context)

Data structures are not just abstract math; they are the reason software feels fast or slow. Two programs can do the same task but differ by 100x because their memory access patterns are different.

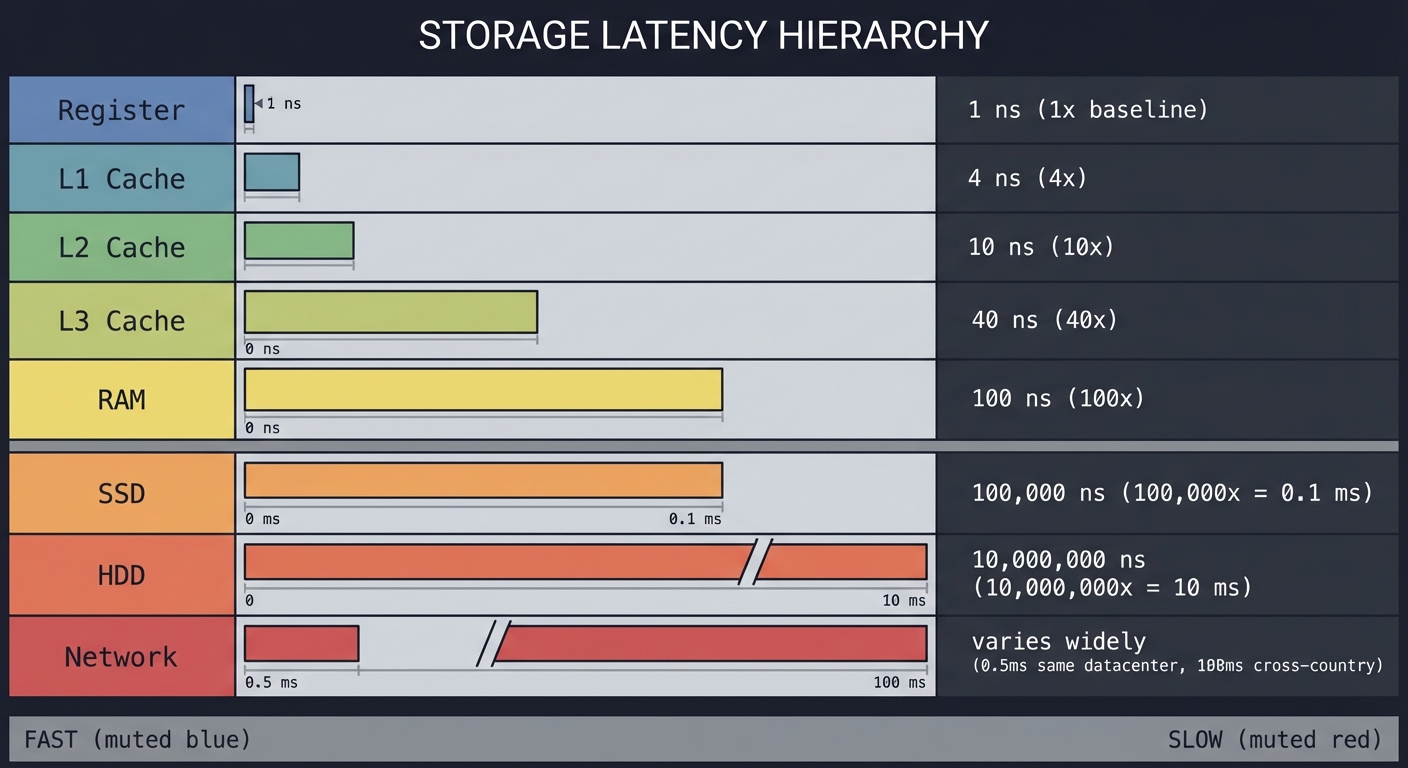

Latency ladder (approximate): Accessing L1 cache is about 0.5 ns, main memory about 100 ns, and disk about 10 ms. That is a difference of roughly 20,000,000x between cache and disk. A single bad data structure choice can push your workload from cache-friendly to memory- or disk-bound.

Source: Jeff Dean latency numbers (2012), https://gist.githubusercontent.com/jboner/2841832/raw/

Memory hierarchy mental model:

CPU registers -> L1 cache -> L2 cache -> L3 cache -> RAM -> SSD -> Disk -> Network

fast fast fast fast slower slower slower slowest

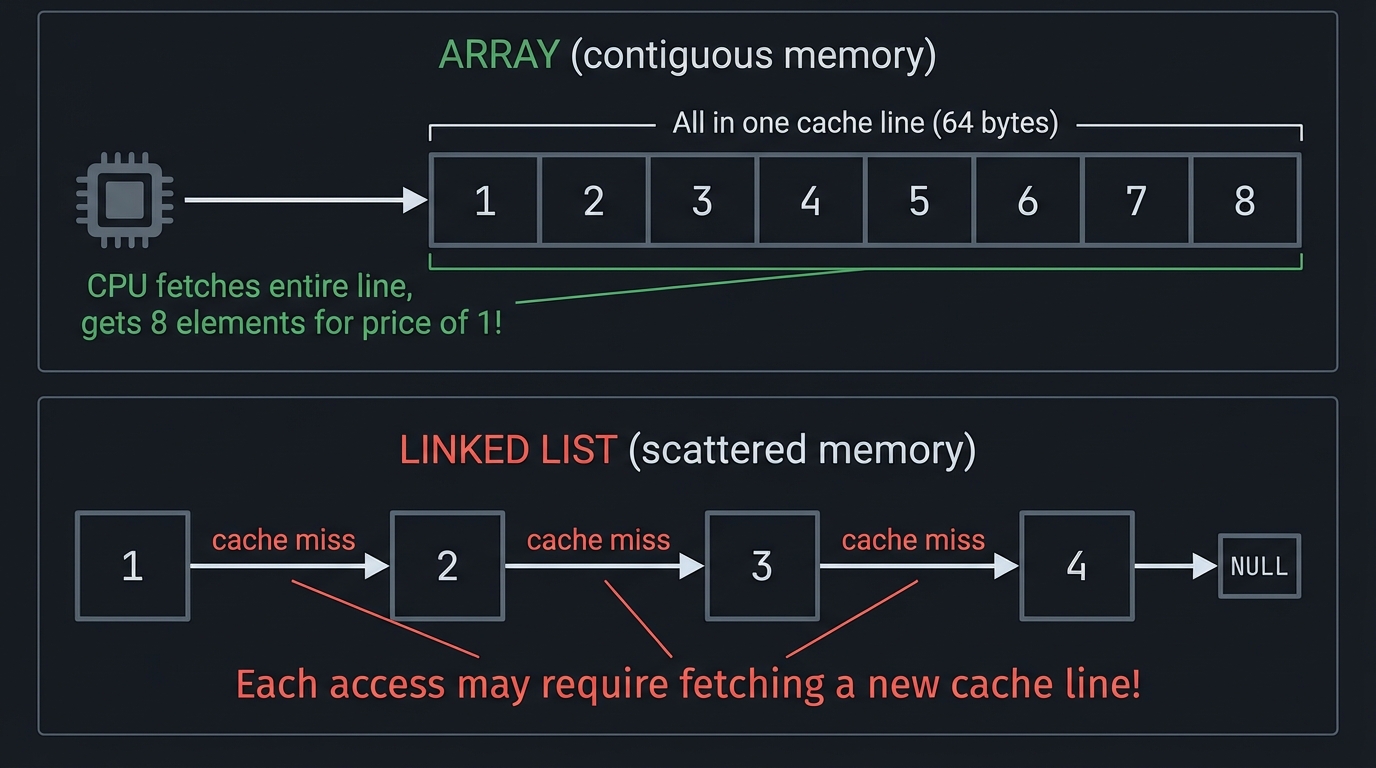

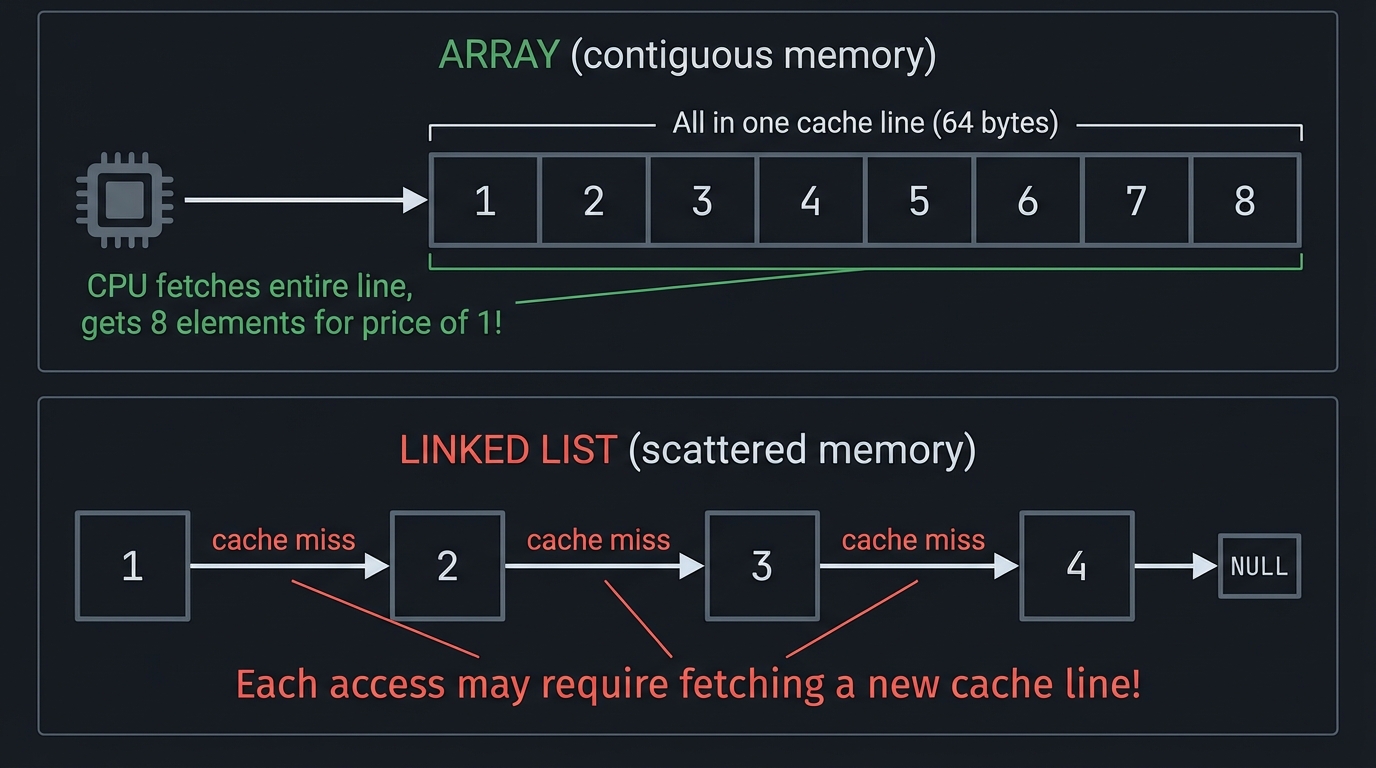

A concrete cache fact: Modern CPUs move data in fixed-size cache lines. A common size is 64 bytes, which means a contiguous array can fetch multiple elements per line, while a linked list often fetches only one useful node per line.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cache_line

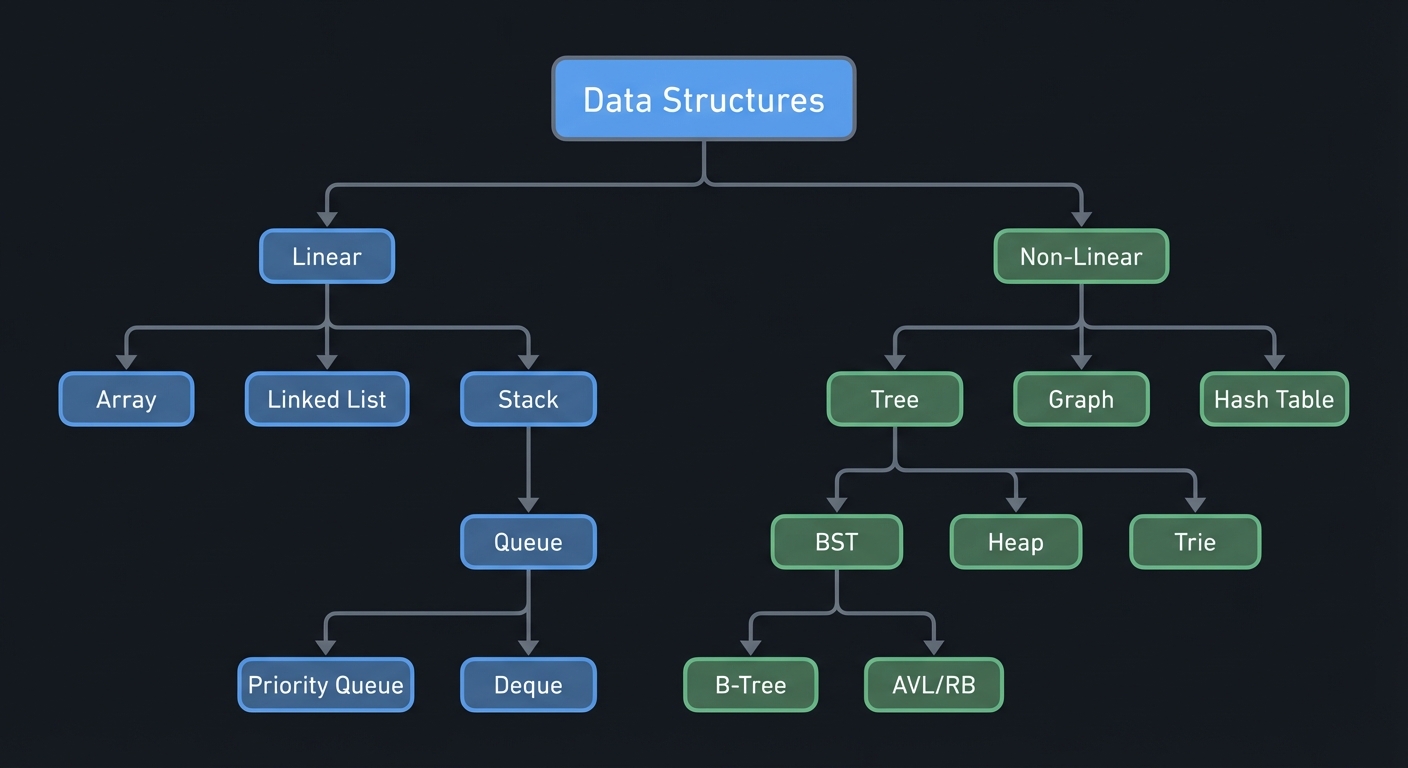

History in one line: Arrays and linked lists solved early memory layout problems; trees and heaps made search and scheduling fast; hash tables made lookup near-constant; graphs model the connected world.

Practical examples:

- Search box autocomplete: tries, heaps, and arrays for top-k ranking

- Web caches: hash tables + linked lists for O(1) LRU

- Databases: B-trees for range scans, hash indexes for equality lookups

- Schedulers: heaps and queues for fairness and priority

Bottom line: Data structures decide whether your program fits in cache, scales to millions of records, or collapses under load.

Prerequisites & Background Knowledge

Essential Prerequisites (Must Have)

- C basics: structs, pointers, dynamic allocation, arrays

- Big-O notation and basic algorithm analysis

- Comfort reading and writing small C programs

- Ability to trace pointer values in a debugger

Helpful But Not Required

- Basic systems knowledge: stack vs heap memory

- Familiarity with recursion

- Some exposure to CLI tools (make, gcc/clang)

- Basic understanding of CPU caches and memory latency

Self-Assessment Questions

- Can you explain what a pointer is in one sentence?

- Can you write a function that reallocates and copies an array?

- Can you reason about O(n) vs O(log n) for a search operation?

- Can you draw a linked list and show how a delete works?

- Can you explain the difference between stack allocation and heap allocation?

Development Environment Setup

- C compiler:

clangorgcc - Debugging:

gdborlldb - Memory checks:

valgrind(Linux) orleaks(macOS) - Optional:

perforInstrumentsfor profiling - Optional:

hyperfinefor micro-benchmarking

Time Investment

- Projects 1-2: 1 week each

- Projects 3-4: 1 week each

- Projects 5-8: 1-2 weeks each

- Project 9: 4-6 weeks

- Total path: ~12-16 weeks at 5-8 hours/week

Important Reality Check

You will debug memory issues. Expect segfaults, leaks, and off-by-one bugs. This is the real lesson, and it is exactly how you develop engineering intuition.

Core Concept Analysis

1) Invariants Are the Contract

Every data structure lives or dies by an invariant. Examples:

- Dynamic array: data is contiguous, size <= capacity

- Linked list: each node points to the next, and no cycles (unless you choose to)

- BST: left subtree < node < right subtree

- Heap: parent <= children (min-heap)

2) Time Complexity vs Real Performance

Big-O explains growth, but constants and memory locality decide practical speed.

Two O(n) loops can differ by 10x if one is cache-friendly.

Also remember: algorithmic complexity assumes uniform memory access, but real hardware is hierarchical. The same data structure can behave differently when it spills from L1 to L3 or out to RAM.

3) Memory Layout and Cache Locality

Arrays walk memory linearly; linked structures jump around.

Contiguous: [A][B][C][D] -> 1 cache line fetch gets multiple elements

Scattered: [A] -> [B] -> [C] -> [D] -> many cache misses

A 64-byte cache line can hold 16 integers (4 bytes each). That means iterating a contiguous array can hit 16 items per line, while a linked list might trigger a miss per node.

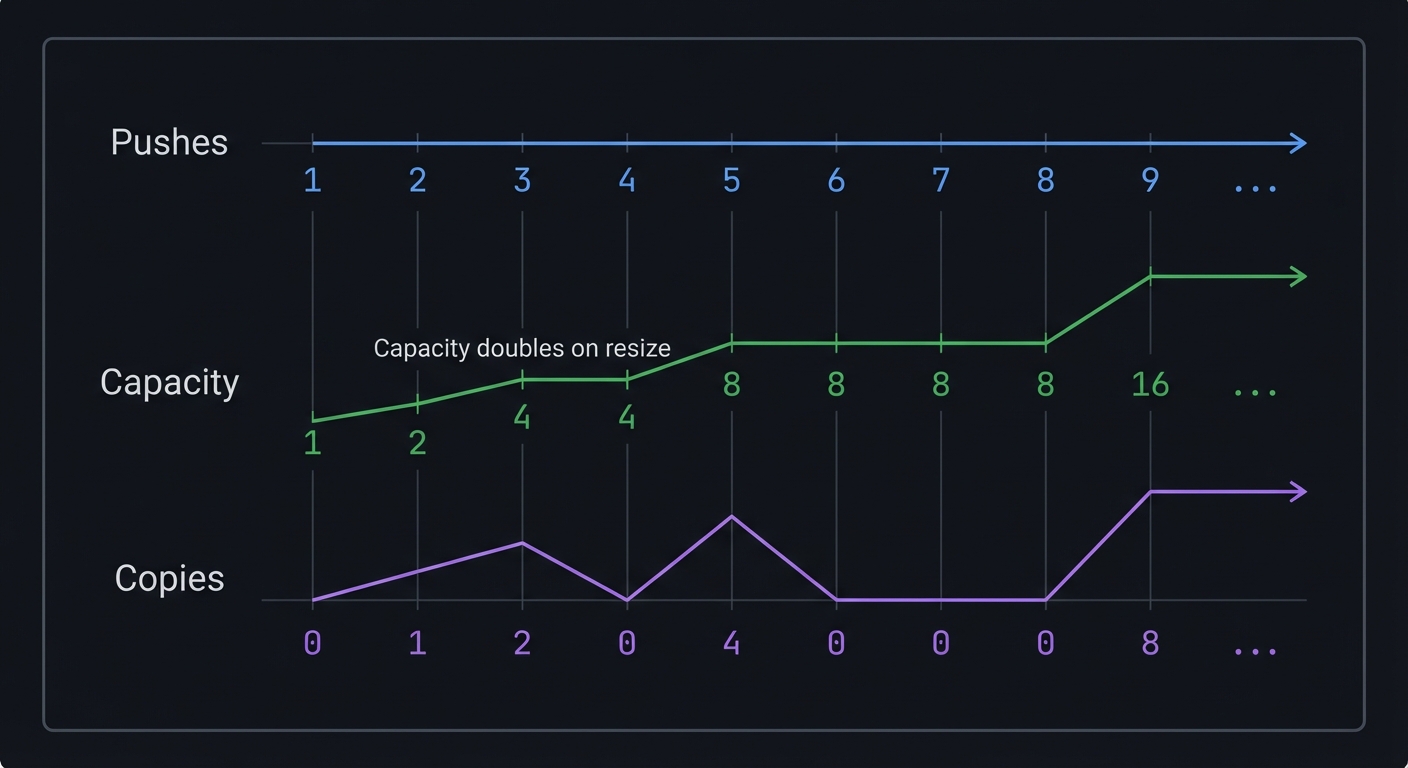

4) Amortized Analysis

Some operations are expensive occasionally, but cheap on average. Dynamic array growth is the classic case. Amortized analysis tells you when occasional spikes are acceptable and when they are not (e.g., real-time systems).

5) Ownership and Lifetimes

Every node you allocate must be freed. Every pointer you store must remain valid. This is the hardest part in C and also the most important for reliability.

6) Choosing the Right Structure

Ask: “What is the dominant operation?” and “What is the working set size?”

If the dominant operation is “find by key,” a hash table wins. If it is “iterate in order,” a BST or sorted array wins. If it is “find min,” a heap wins.

Concept Summary Table

| Concept | What You Must Internalize | Where It Appears | Failure Mode If Wrong |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contiguous memory | Indexing and cache behavior | Project 1, 7 | Cache misses, slow scans |

| Pointers and ownership | Lifetime and safety | Project 2, 5 | Leaks, use-after-free |

| LIFO vs FIFO | Ordering guarantees | Project 3, 4 | Incorrect behavior |

| Hashing | Uniform distribution and collisions | Project 5 | O(n) lookup |

| Tree ordering | Log-time operations | Project 6 | Degenerate linked list |

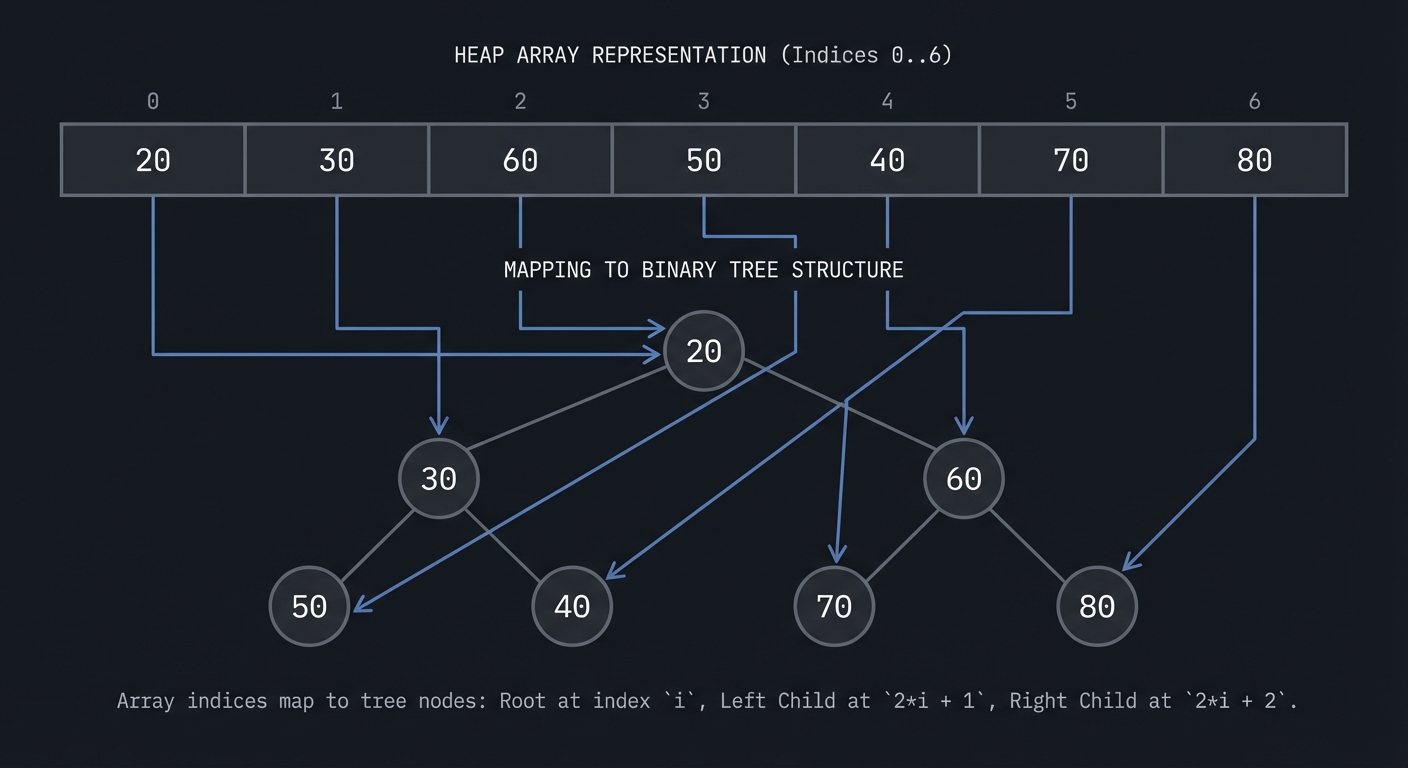

| Partial ordering | Priority systems | Project 7 | Wrong priority |

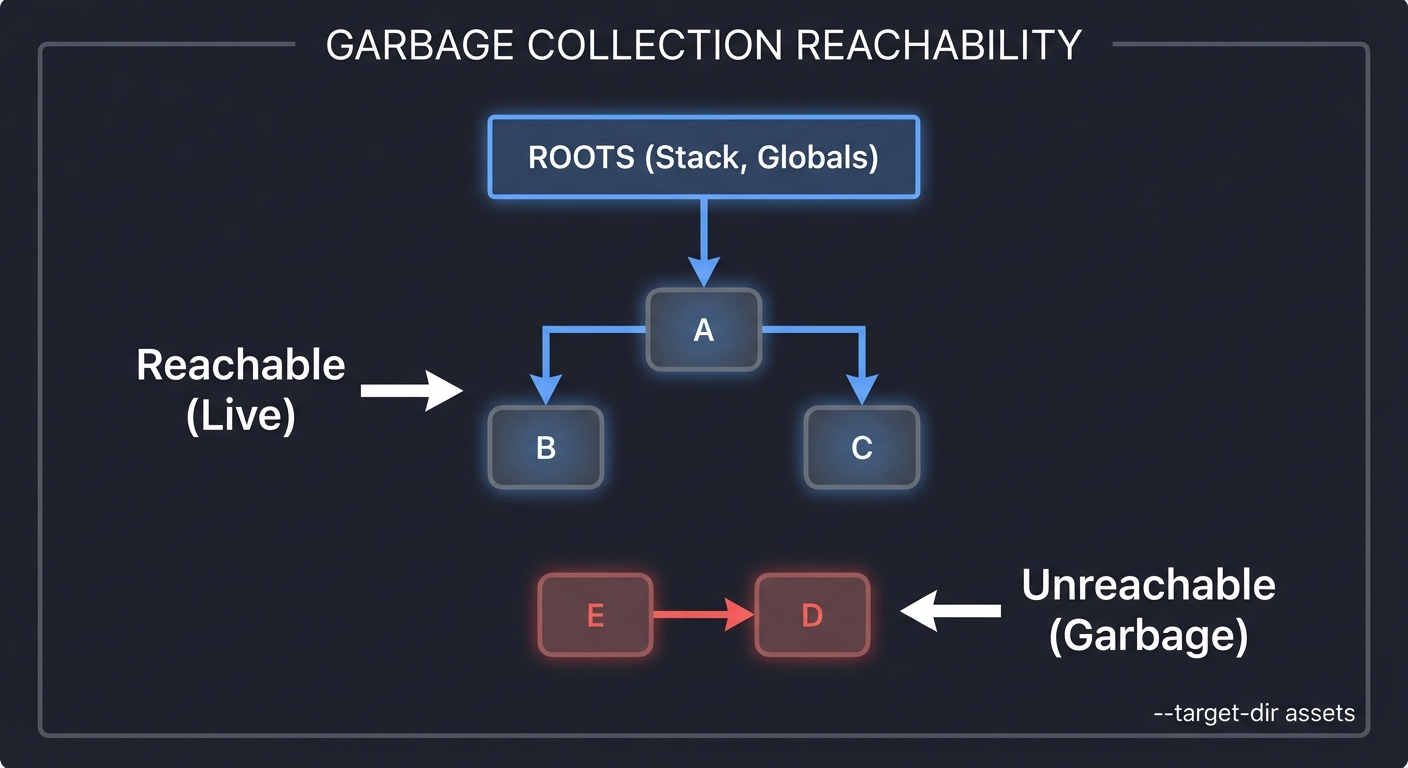

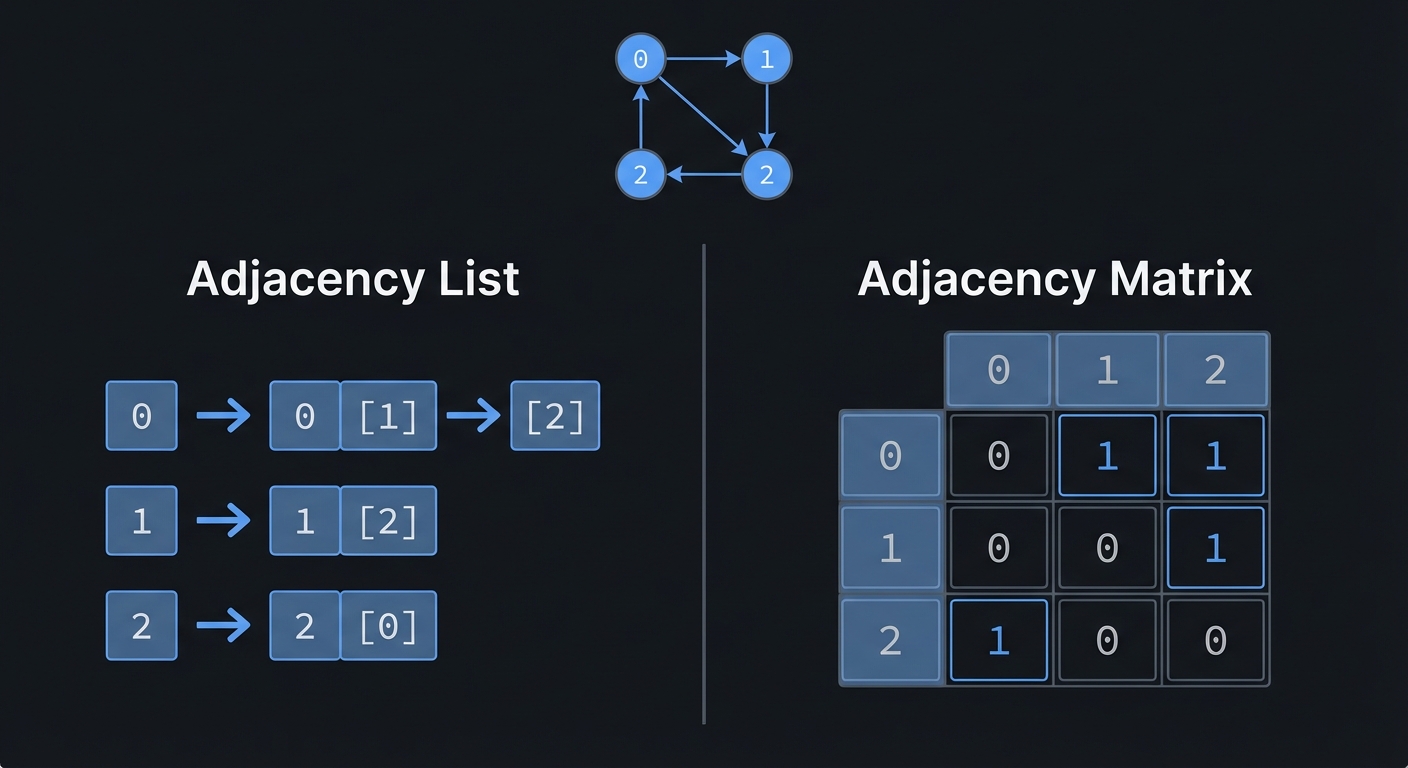

| Graph traversal | Reachability and shortest path | Project 8 | Wrong paths |

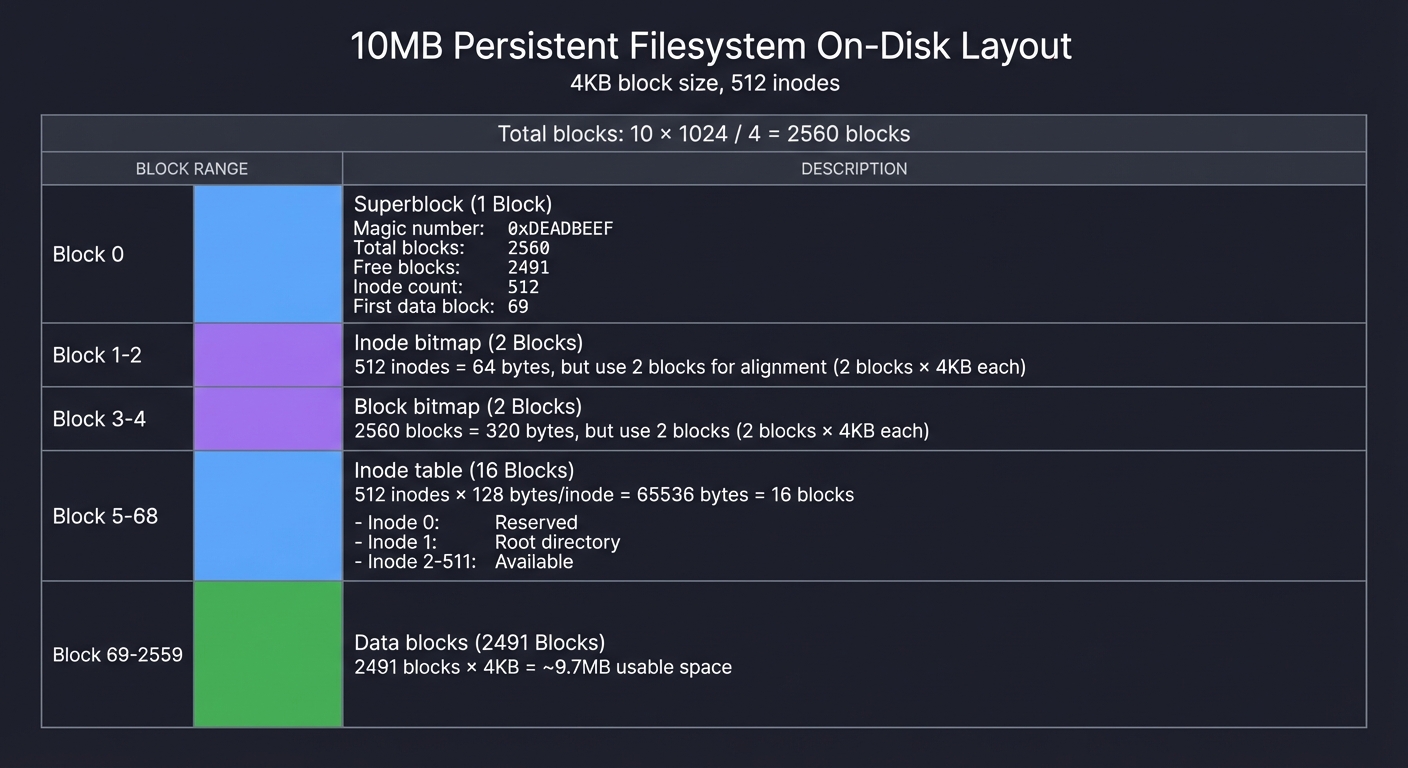

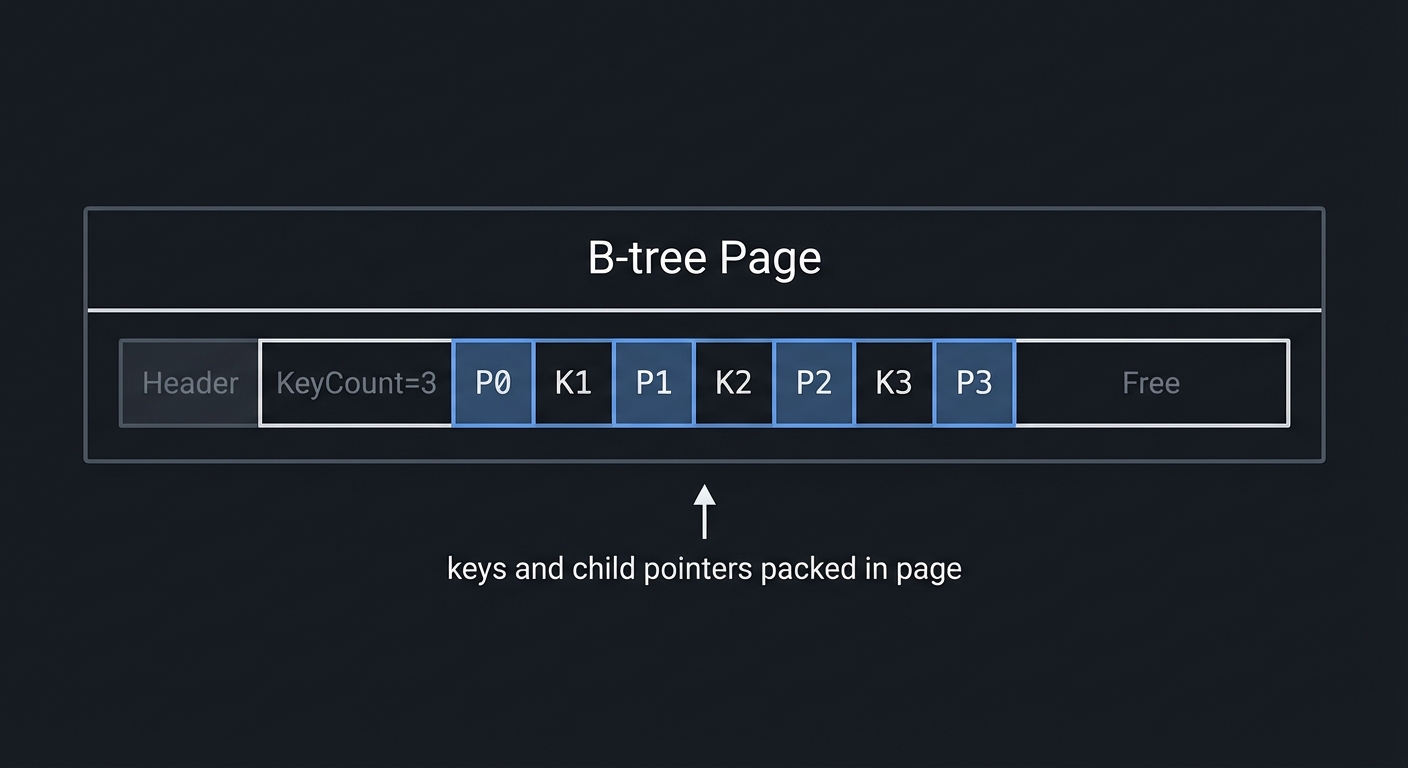

| On-disk structures | Paging, B-trees | Project 9 | Excessive I/O |

Deep Dive Reading by Concept

| Concept | Book and Chapter |

|---|---|

| Arrays, pointers, memory layout | Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective, Ch 2-3 |

| Dynamic arrays, amortized analysis | Introduction to Algorithms (CLRS), Ch 17 |

| Lists, stacks, queues | CLRS, Ch 10 |

| Hashing | CLRS, Ch 11; Algorithms, Fourth Edition, Ch 3.4 |

| Trees and BSTs | CLRS, Ch 12; Algorithms, Fourth Edition, Ch 3.2 |

| Heaps and priority queues | CLRS, Ch 6 |

| Graphs and traversal | CLRS, Ch 22-24 |

| B-trees and storage | CLRS, Ch 18; Database Internals, Ch 1-4 |

| C memory management | C Programming: A Modern Approach, Ch 11-12 |

| Practical C implementations | Mastering Algorithms with C, Ch 1-5 |

Quick Start (First 48 Hours)

Day 1:

- Implement a bump allocator and a tiny dynamic array.

- Add debug prints that show addresses and capacity growth.

- Track how many copies are done during growth.

Day 2:

- Implement a singly linked list and visualize nodes with addresses.

- Measure iteration time vs dynamic array for 1M elements.

- Write a short README explaining the trade-off you observed.

Recommended Learning Paths

1) Systems Path (C-heavy)

- Projects 1 -> 2 -> 4 -> 5 -> 6 -> 7 -> 9

- Focus: memory layout, performance, correctness under load

2) Interview Path (theory-first)

- Projects 1 -> 2 -> 3 -> 4 -> 5 -> 6 -> 8

- Focus: explaining invariants, common questions, big-O reasoning

3) Product Path (practical impact)

- Projects 1 -> 2 -> 5 -> 7 -> 8 -> 9

- Focus: caching, scheduling, data access, real-world trade-offs

Big Picture / Mental Model

Problem -> Dominant operation -> Candidate structures -> Memory layout -> Performance

Find by key? -> hash table, BST

Find min/max? -> heap

Order matters? -> array, BST

Sequence? -> array, linked list, deque

Relationships? -> graph

Disk data? -> B-tree, log-structured

Success Metrics

- You can implement array, list, stack, queue, hash table, BST, heap, and graph from scratch.

- You can explain the invariant of each structure without notes.

- You can predict time complexity and typical constant-factor behavior.

- You can debug memory errors with a tool and fix them confidently.

- You can justify a structure choice for a real product scenario.

- You can explain how cache behavior changes the performance story.

How to Use This Guide

- Read the concept analysis before each project.

- Build the project and print internal states (addresses, pointers, sizes).

- Compare real timings with theoretical complexity.

- Answer the design questions and interview prompts.

- Use the definition of done to verify completeness.

- Keep a running log of bugs and fixes; that log is the real learning artifact.

Core System Walkthrough: From Problem to Cache Lines

User problem -> Operations (find, insert, delete) -> Data structure choice

-> Memory layout -> Cache behavior -> Real runtime cost

If you get the structure wrong, the CPU spends time waiting on memory instead of computing.

This is why structures that minimize pointer chasing and maximize contiguous access often win in practice.

Implementation Navigation Cheatsheet

Use consistent file naming so your future self can navigate:

array.c/.h,list.c/.h,stack.c/.h,queue.c/.hhash.c/.h,bst.c/.h,heap.c/.h,graph.c/.h

Useful rg searches when debugging:

rg "struct .*Node"to find node layoutsrg "malloc\\("to audit allocationsrg "free\\("to verify cleanuprg "size|capacity|count"to find size invariantsrg "assert\\("to find invariant checks

Debugging Toolkit

- AddressSanitizer:

clang -fsanitize=address -g - Valgrind:

valgrind --leak-check=full ./your_program - GDB:

gdb ./your_programthenrun,bt,frame - Perf (Linux):

perf stat ./your_program hexdump -Cto inspect binary structures

Data Structure Atlas (Core Structs and Invariants)

| Structure | Core Structs | Invariant |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Array | data, size, capacity |

size <= capacity, contiguous |

| Linked List | Node{data,next} |

next is NULL at tail |

| Stack | items, top |

top == -1 when empty |

| Queue | front, rear, size |

size tracks elements in ring |

| Hash Table | buckets, Entry{key,value,next} |

load factor < threshold |

| BST | Node{key,left,right} |

left < key < right |

| Heap | data[] |

heap property for all nodes |

| Graph | adj_list[] |

each edge recorded consistently |

Contribution Checklist (For Your Own Code)

- Each structure has unit tests for empty, single, and many elements.

- All allocations are paired with frees.

- Invariants are checked with debug asserts.

- Benchmarks are repeatable with fixed seeds.

- README explains the trade-offs and use cases.

- Benchmark results include CPU and memory profile notes.

Glossary of Data Structure Terms

- Invariant: A rule that must always hold for correctness.

- Amortized: Average cost over a sequence of operations.

- Load factor: Entries / buckets in a hash table.

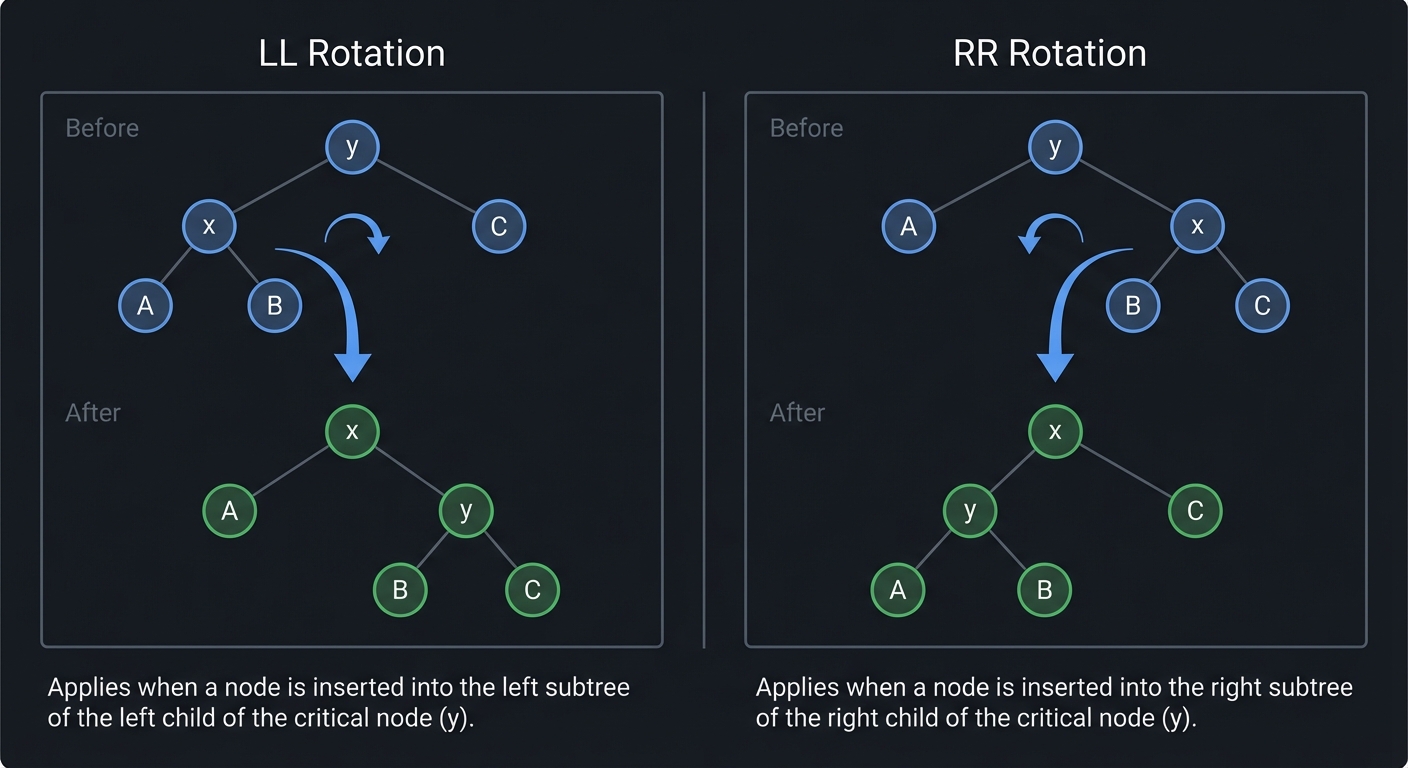

- Rotation: Tree operation that preserves ordering but changes shape.

- Sentinel: Special node that simplifies edge cases.

- Adjacency list: Per-node list of edges in a graph.

- Cache line: Fixed-size block of data moved between memory and cache.

- Tombstone: A deleted slot marker in open addressing.

- Balance factor: Height difference between left and right subtrees.

- Topology: The shape of connections in a graph.

Common Failure Signatures

Problem: “Segmentation fault on delete”

- Why: Node pointers not updated correctly.

- Fix: Trace prev/next updates and validate NULL cases.

- Quick test: Delete head, tail, and middle from a 3-node list.

Problem: “Hash table becomes slow”

- Why: Load factor too high or poor hash distribution.

- Fix: Resize earlier and test with adversarial keys.

- Quick test: Insert 1M sequential keys and measure collisions.

Problem: “Heap returns wrong min”

- Why: Heapify swap logic broken or index math off-by-one.

- Fix: Validate parent/child indices and run heap invariant checks.

- Quick test: After every insert, scan array to verify parent <= children.

Problem: “BFS path length is too long”

- Why: Using DFS instead of BFS or not tracking distances.

- Fix: Use a queue and distance array.

- Quick test: Compare BFS distance to a known shortest path.

Problem: “AVL rotations corrupt tree”

- Why: Incorrect child reassignment or height update.

- Fix: Validate rotation logic with 3-node cases.

- Quick test: Insert 3 nodes that trigger each rotation case.

Reading Plan (Daily, Lightweight)

Day 1-2: Arrays, pointers, memory layout (CSAPP Ch 2-3) Day 3-4: Linked lists, stacks, queues (CLRS Ch 10) Day 5-6: Hash tables (CLRS Ch 11) Day 7-9: Trees and balancing (CLRS Ch 12-13) Day 10-12: Heaps and priority queues (CLRS Ch 6) Day 13-16: Graphs (CLRS Ch 22-24) Day 17+: B-trees and database internals (CLRS Ch 18, Database Internals Ch 1-4)

If you only have 30 minutes/day, focus on one structure per week and implement a tiny version with tests.

Part 1: Why Do Data Structures Exist?

The Fundamental Problem

Every program needs to store and organize collections of data. But here’s the critical insight:

How you organize data determines how fast your program runs.

Consider this: You have 1 million user records. How do you store them?

| Operation | Unsorted Array | Sorted Array | Hash Table | Binary Search Tree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Find user by ID | O(n) = 1M checks | O(log n) = 20 checks | O(1) = 1 check | O(log n) = 20 checks |

| Add new user | O(1) = instant | O(n) = 1M shifts | O(1) = instant | O(log n) = 20 steps |

| Delete user | O(n) = 1M checks | O(n) = 1M shifts | O(1) = instant | O(log n) = 20 steps |

| List in order | O(n log n) = sort | O(n) = just read | O(n log n) = sort | O(n) = in-order walk |

There is no perfect data structure. Every choice is a trade-off between:

- Time (how fast are operations?)

- Space (how much memory?)

- Complexity (how hard to implement correctly?)

Workload questions to ask before choosing:

- Are reads more common than writes?

- Is the access pattern random or sequential?

- Do you need ordered traversal or just lookup?

- Will the data fit in memory or spill to disk?

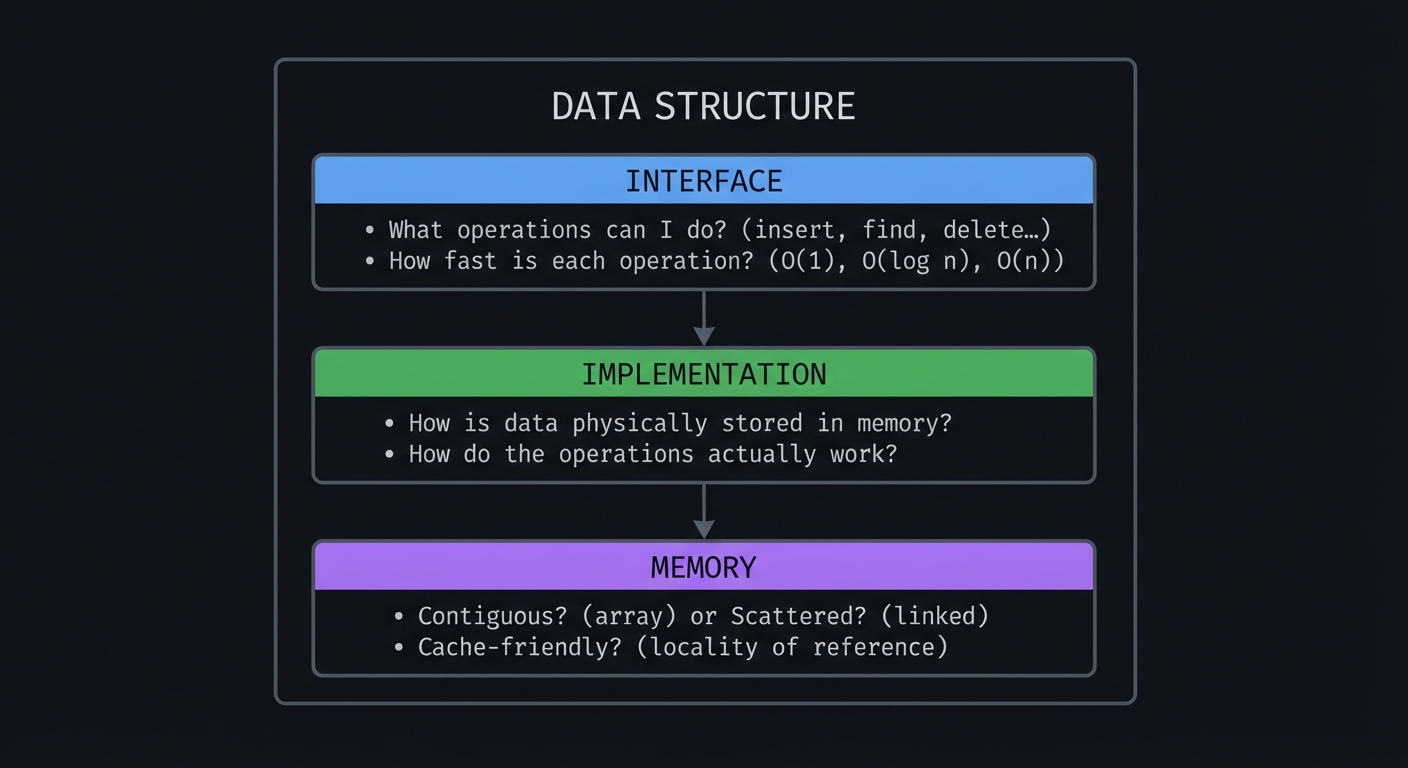

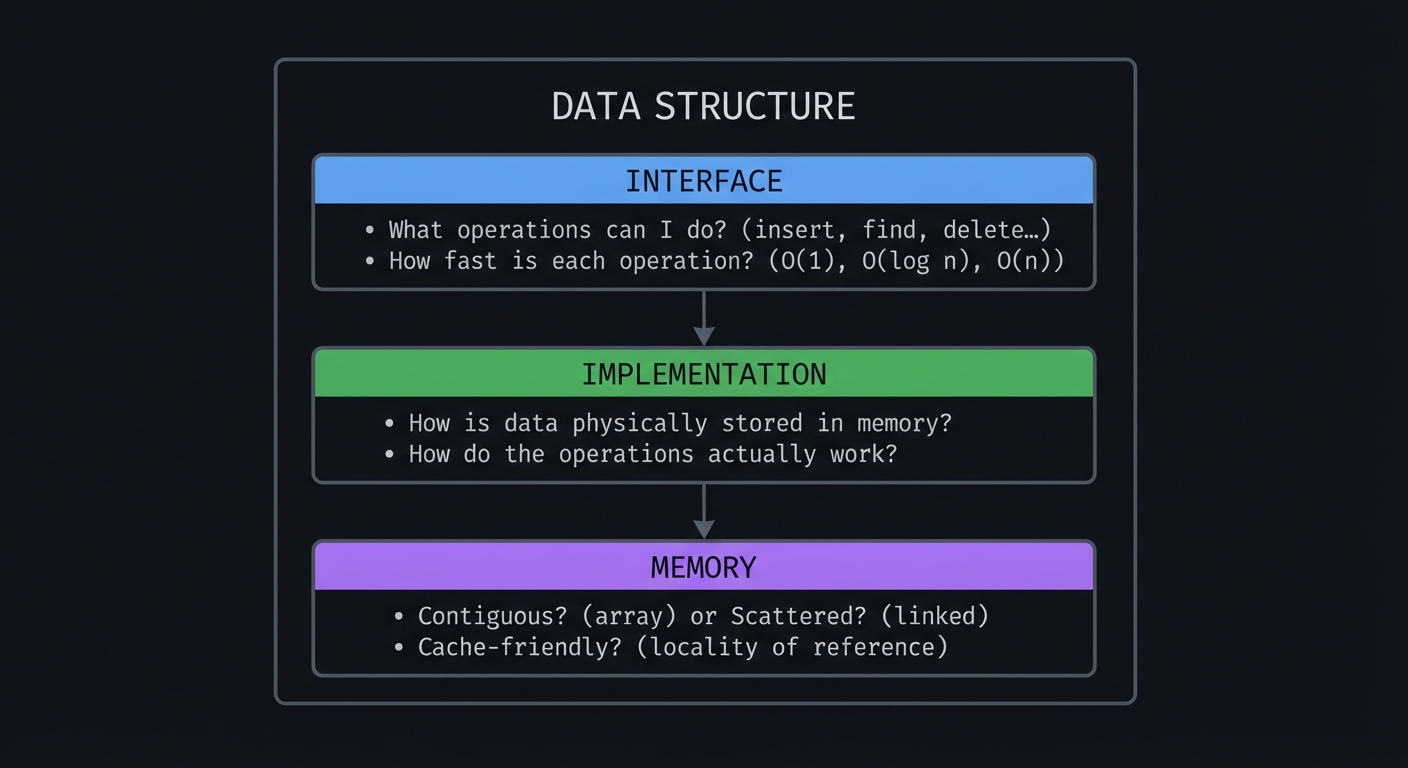

The Mental Model

Think of data structures as containers with rules:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ DATA STRUCTURE │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ INTERFACE │ │

│ │ - What operations can I do? (insert, find, delete...) │ │

│ │ - How fast is each operation? (O(1), O(log n), O(n)) │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ IMPLEMENTATION │ │

│ │ - How is data physically stored in memory? │ │

│ │ - How do the operations actually work? │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ MEMORY │ │

│ │ - Contiguous? (array) or Scattered? (linked) │ │

│ │ - Cache-friendly? (locality of reference) │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

You can also think of them as an “operation contract”: you are paying with memory and complexity to buy specific performance guarantees.

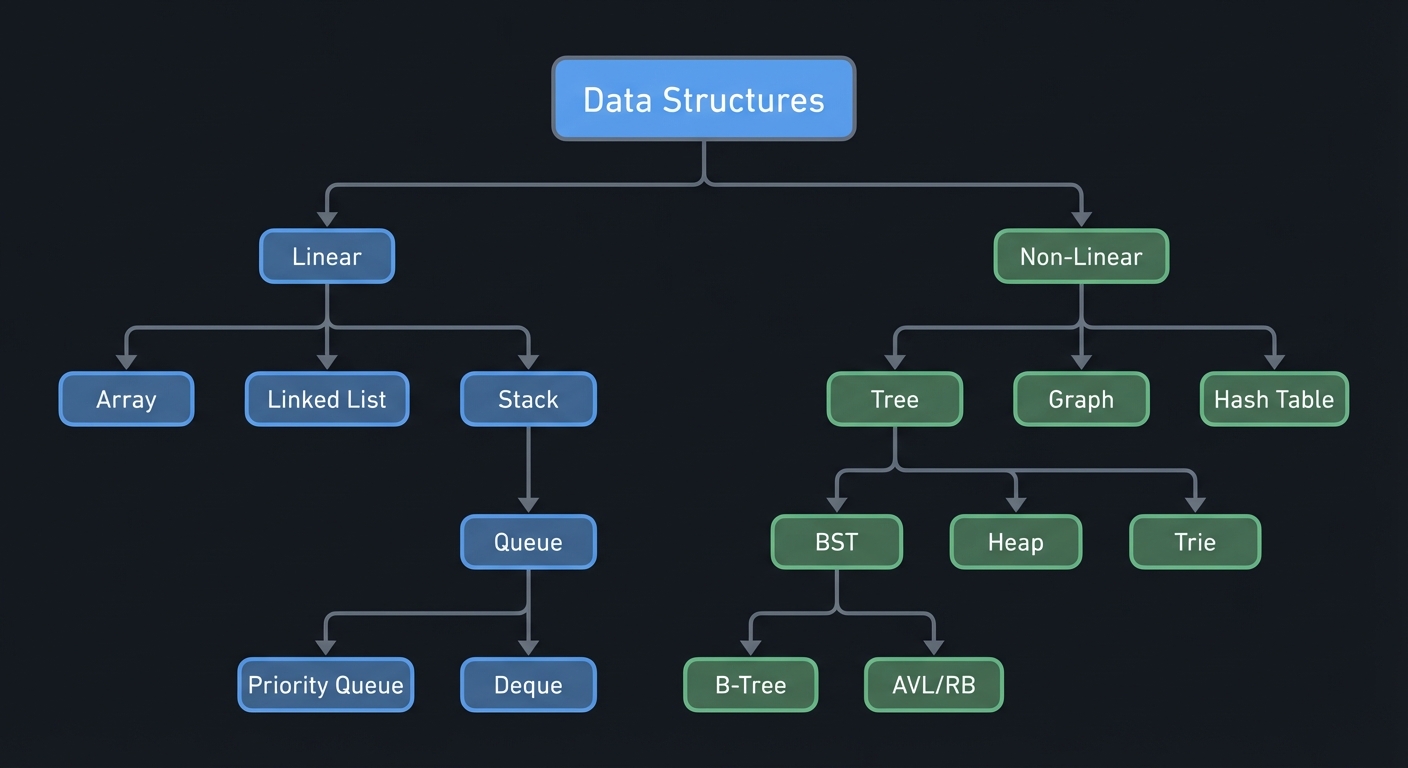

The Data Structure Family Tree

Data Structures

│

┌────────────────────┴────────────────────┐

│ │

Linear Non-Linear

│ │

┌────────┼────────┐ ┌──────────┼──────────┐

│ │ │ │ │ │

Array Linked Stack Tree Graph Hash

List Queue │ Table

│ ┌────────┼────────┐

┌──────┴──────┐ │ │ │

│ │ BST Heap Trie

Priority Deque │

Queue B-Tree

AVL/RB

Hybrid structures are common in real systems: LRU = hash table + doubly linked list, priority queues often wrap heaps, and databases blend B-trees, hash tables, and buffer pools.

Part 2: The Learning Path

Phase 1: Foundations (3-4 weeks)

- Project 1: Memory Arena & Dynamic Array

- Project 2: Linked List Toolkit

- Outcome: you can reason about raw memory and pointer ownership.

Phase 2: Abstract Data Types (2-3 weeks)

- Project 3: Stack Machine (Calculator/VM)

- Project 4: Queue Systems (Task Scheduler)

- Outcome: you can model ordering constraints (LIFO/FIFO).

Phase 3: Fast Lookup (3-4 weeks)

- Project 5: Hash Table (Dictionary/Cache)

- Project 6: Binary Search Tree & Balancing

- Outcome: you can pick between unordered speed and ordered search.

Phase 4: Specialized Structures (3-4 weeks)

- Project 7: Heap & Priority Queue

- Project 8: Graph Algorithms Visualizer

- Outcome: you can schedule and reason about relationships.

Phase 5: Capstone (4-6 weeks)

- Project 9: Mini Database Engine

- Outcome: you can combine structures into a real system.

Project Comparison Table

| Project | Difficulty | Time | Key Insight | Real-World Use | Core Invariant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Memory Arena & Dynamic Array | ⭐⭐ | 1 week | Memory is just bytes | Every program uses arrays | size <= capacity |

| Linked List Toolkit | ⭐⭐ | 1 week | Pointers connect scattered memory | Undo systems, playlists | tail->next == NULL |

| Stack Machine | ⭐⭐⭐ | 1 week | LIFO enables recursion/backtracking | Compilers, calculators | top points to last |

| Queue Systems | ⭐⭐⭐ | 1 week | FIFO enables fairness/ordering | Job schedulers, BFS | front/rear wrap |

| Hash Table | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ | 2 weeks | Trade space for O(1) lookup | Databases, caches, dictionaries | load factor bounded |

| BST & Balancing | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ | 2 weeks | Ordering enables fast search | Databases, file systems | left < node < right |

| Heap & Priority Queue | ⭐⭐⭐ | 1 week | Partial ordering is cheaper | Schedulers, Dijkstra’s | parent <= children |

| Graph Visualizer | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ | 2 weeks | Relationships are everywhere | Maps, social networks, AI | edges consistent |

| Mini Database | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ | 4-6 weeks | Combine everything | Real databases | page + index consistency |

Project 1: Memory Arena & Dynamic Array

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Zig

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Memory Management / Low-Level Programming

- Software or Tool: Custom memory allocator

- Main Book: Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective by Bryant & O’Hallaron

What you’ll build

A memory arena (bump allocator) and a dynamic array (like C++’s std::vector or Python’s list) from scratch, visualizing memory layout as you add and remove elements.

Deliverables:

arena.c/.hwith allocate/reset/destroy functionsdynarray.c/.hwith push/pop/get/set and growth logic- A demo program that prints memory addresses and capacity growth

Why it teaches data structures fundamentals

This is where everything starts. Before you can understand ANY data structure, you must understand:

- What is memory? (just a giant array of bytes)

- What is an address? (index into that array)

- What is allocation? (reserving bytes)

- What is contiguous storage? (elements side-by-side)

Most people use malloc() as a black box. By building your own allocator, you’ll see that memory is just bytes, and data structures are just ways of interpreting those bytes.

You will also see the concrete cost of growing arrays and why amortized analysis matters in practice, not just on paper.

Core challenges you’ll face

- Memory as bytes (everything is just numbers at addresses) → maps to memory model

- Pointer arithmetic (address + offset = new address) → maps to array indexing

- Reallocation (grow array when full) → maps to amortized analysis

- Memory fragmentation (holes in memory) → maps to allocator design

- Cache locality (contiguous = fast) → maps to performance

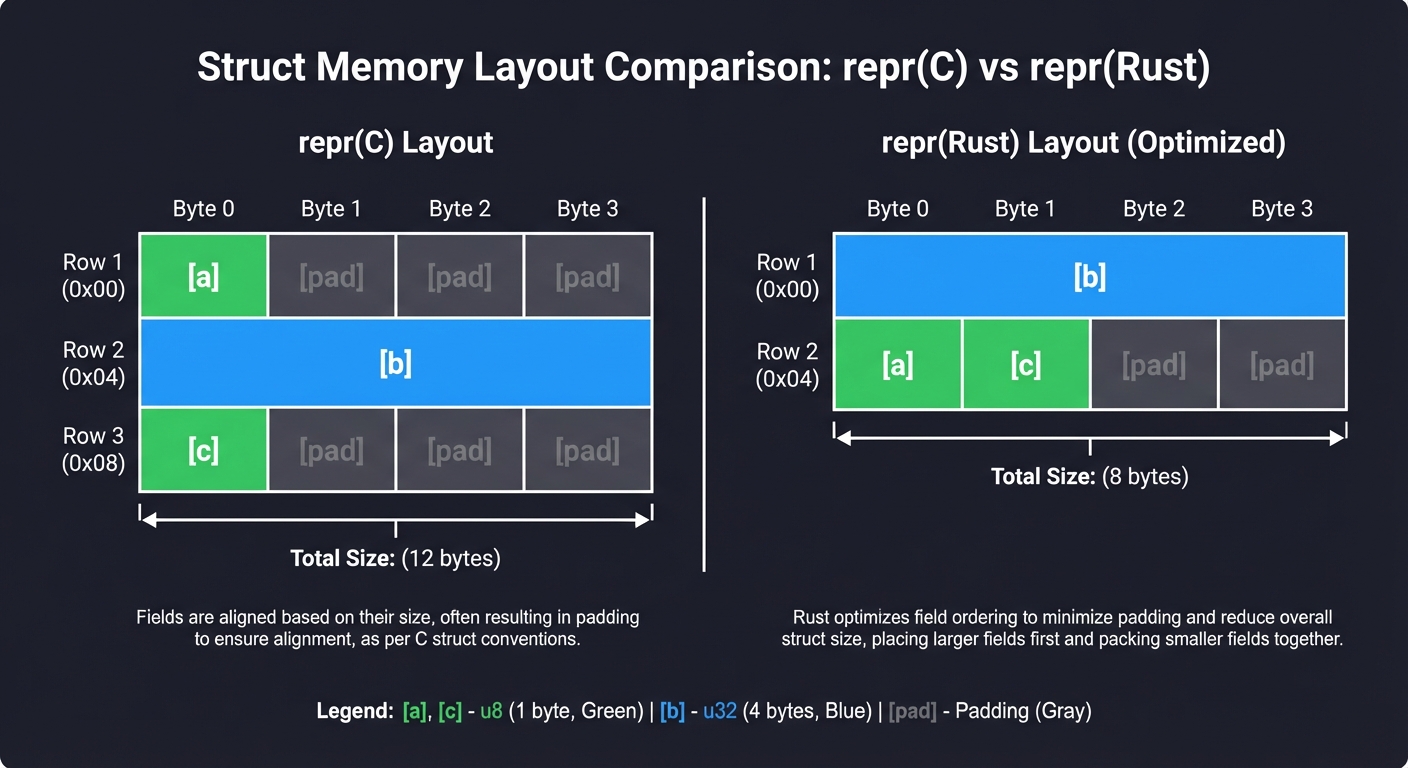

- Alignment (8/16-byte alignment) → maps to hardware efficiency

- Failure handling (out-of-memory) → maps to robust API design

Key Concepts

| Concept | Resource |

|---|---|

| Memory Layout | Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective Chapter 9 - Bryant & O’Hallaron |

| Pointer Arithmetic | C Programming: A Modern Approach Chapter 12 - K.N. King |

| Dynamic Arrays | Introduction to Algorithms Chapter 17.4 (Amortized Analysis) - CLRS |

| Cache Performance | The Lost Art of Structure Packing - Eric S. Raymond |

| C Allocators | Effective C, 2nd Edition Chapter 12 - Robert C. Seacord |

Difficulty & Time

- Difficulty: Intermediate

- Time estimate: 1 week

- Prerequisites: Basic C, understanding of pointers

- Stretch goal: Add

reserveandshrink_to_fit

Real World Outcome

$ ./memory_demo

=== Memory Arena Demo ===

Arena created: 1MB at address 0x7f1234500000

Allocating 100 bytes... got 0x7f1234500000

Allocating 200 bytes... got 0x7f1234500064 (offset: 100)

Allocating 50 bytes... got 0x7f123450012C (offset: 300)

Memory map:

[0x7f1234500000] ████████████████████░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░

^100 bytes ^200 bytes ^50 bytes ^free space

Arena reset! All allocations freed instantly (no individual free calls needed)

=== Dynamic Array Demo ===

Creating dynamic array with initial capacity 4...

Push 1: [1, _, _, _] capacity=4, size=1

Push 2: [1, 2, _, _] capacity=4, size=2

Push 3: [1, 2, 3, _] capacity=4, size=3

Push 4: [1, 2, 3, 4] capacity=4, size=4

Push 5: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, _, _, _] capacity=8, size=5 ← GREW! (copied to new memory)

Memory addresses:

Before grow: data at 0x7f1234600000

After grow: data at 0x7f1234700000 (new location!)

Performance test: push 1,000,000 elements

Total time: 0.023s

Total reallocations: 20 (log2 of 1M)

Amortized cost per push: O(1) ✓

Random access test:

arr[0] = 1 (0.000001ms)

arr[500000] = ? (0.000001ms) ← Same speed! O(1) random access ✓

You should be able to explain why the final capacity is a power of two and why the data pointer changes after a resize.

The Core Question You’re Answering

How can I grow a contiguous array without losing data, while keeping average inserts fast and memory overhead predictable? And how do I expose this to callers without leaking memory or breaking invariants?

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Pointer arithmetic and array indexing (C Programming: A Modern Approach, Ch 12)

- Dynamic allocation and reallocation (C Programming: A Modern Approach, Ch 17)

- Amortized analysis (CLRS, Ch 17)

- Alignment and padding (Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective, Ch 2)

- Cache lines and locality (see cache line source above)

Questions to Guide Your Design

- What growth factor keeps reallocation rare without wasting too much memory?

- How do you represent size vs capacity so invariants are explicit?

- What should happen when allocation fails (return NULL, abort, or recover)?

- How will you visualize memory so bugs become obvious?

- Should your API allow random inserts, or is push/pop enough for now?

Thinking Exercise

Simulate pushes into a dynamic array starting at capacity 1. For 10 inserts, write down the capacity after each push and count how many total copies occur. Then repeat with a growth factor of 1.5 and compare total copies.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- Why is

push_backamortized O(1) butinsertin the middle O(n)? - When do pointer or reference invalidation problems occur in vectors?

- What is the difference between

malloc,calloc, andrealloc? - How does alignment affect performance on modern CPUs?

- Why is contiguous memory more cache-friendly?

- How does a ring buffer differ from a dynamic array?

Hints in Layers

1) Start with a bump allocator that never frees. It is just a base pointer and an offset.

2) For the dynamic array, store data, size, and capacity in a struct.

3) Grow only when size == capacity, then allocate new memory and copy.

4) Validate with a tiny example first, then scale.

5) Track the number of copies to verify amortized behavior.

if (arr->size == arr->capacity) {

size_t new_cap = arr->capacity ? arr->capacity * 2 : 4;

int* new_data = malloc(new_cap * sizeof(int));

memcpy(new_data, arr->data, arr->size * sizeof(int));

free(arr->data);

arr->data = new_data;

arr->capacity = new_cap;

}

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Why It Helps |

|---|---|---|

| Memory layout | Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective, Ch 2-3 | Explains how memory is addressed |

| Pointers | C Programming: A Modern Approach, Ch 11-12 | Concrete pointer mechanics |

| Amortized analysis | CLRS, Ch 17 | Formal reasoning for growth strategy |

| Allocators | C Interfaces and Implementations, Ch 2 | Real allocator patterns |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem: “Segfault during array growth”

- Why:

reallocormallocfailed or copy used wrong size. - Fix: Check for NULL, copy

size * sizeof(T), notcapacity. - Quick test: Push 1..1000 and verify all values.

Problem: “Arena returns overlapping blocks”

- Why: Alignment or offset update is wrong.

- Fix: Align size and update offset after returning pointer.

- Quick test: Allocate three blocks and assert addresses increase.

Problem: “Memory leak after resize”

- Why: Old buffer not freed after copy.

- Fix: Free the old pointer after successful copy.

- Quick test: Run with ASan or Valgrind.

Problem: “Capacity never grows”

- Why:

sizenot incremented or growth check uses wrong comparison. - Fix: Increment size on successful push and check

size >= capacity. - Quick test: Push until over initial capacity and verify growth.

Definition of Done

- Arena can allocate multiple blocks and reset in O(1)

- Dynamic array grows correctly and preserves all values

- Invariants (

size <= capacity) enforced with asserts - Benchmarks show amortized O(1) push behavior

- Memory checks report zero leaks

- Growth factor and trade-offs documented in README

Learning Milestones

- Arena allocates bytes → You understand memory is just bytes

- Dynamic array grows → You understand reallocation and copying

- Growth is O(1) amortized → You understand why doubling works

- Random access is O(1) → You understand contiguous memory

- Memory layout is visible → You can reason about cache behavior

Implementation

Memory Arena (Bump Allocator)

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <string.h>

typedef struct {

uint8_t* base; // Start of memory block

size_t size; // Total size

size_t offset; // Current position (bump pointer)

} Arena;

Arena* arena_create(size_t size) {

Arena* arena = malloc(sizeof(Arena));

arena->base = malloc(size);

arena->size = size;

arena->offset = 0;

printf("Arena created: %zu bytes at %p\n", size, arena->base);

return arena;

}

void* arena_alloc(Arena* arena, size_t size) {

// Align to 8 bytes for performance

size_t aligned_size = (size + 7) & ~7;

if (arena->offset + aligned_size > arena->size) {

printf("Arena out of memory!\n");

return NULL;

}

void* ptr = arena->base + arena->offset;

arena->offset += aligned_size;

printf("Allocated %zu bytes at %p (offset: %zu)\n",

size, ptr, arena->offset - aligned_size);

return ptr;

}

void arena_reset(Arena* arena) {

arena->offset = 0; // Instant "free" of everything!

printf("Arena reset! All memory available again.\n");

}

void arena_destroy(Arena* arena) {

free(arena->base);

free(arena);

}

// Visualize memory usage

void arena_visualize(Arena* arena) {

printf("\nMemory map (%zu / %zu bytes used):\n[", arena->offset, arena->size);

int blocks = 50;

int used = (arena->offset * blocks) / arena->size;

for (int i = 0; i < blocks; i++) {

printf("%s", i < used ? "█" : "░");

}

printf("]\n\n");

}

Dynamic Array

typedef struct {

int* data; // Pointer to array

size_t size; // Number of elements

size_t capacity; // Allocated space

} DynArray;

DynArray* dynarray_create(size_t initial_capacity) {

DynArray* arr = malloc(sizeof(DynArray));

arr->data = malloc(initial_capacity * sizeof(int));

arr->size = 0;

arr->capacity = initial_capacity;

printf("Created array with capacity %zu at %p\n",

initial_capacity, arr->data);

return arr;

}

void dynarray_push(DynArray* arr, int value) {

// Check if we need to grow

if (arr->size >= arr->capacity) {

size_t new_capacity = arr->capacity * 2; // Double!

int* new_data = malloc(new_capacity * sizeof(int));

// Copy old data to new location

memcpy(new_data, arr->data, arr->size * sizeof(int));

printf("GROW: %zu -> %zu (moved from %p to %p)\n",

arr->capacity, new_capacity, arr->data, new_data);

free(arr->data);

arr->data = new_data;

arr->capacity = new_capacity;

}

arr->data[arr->size++] = value;

}

int dynarray_get(DynArray* arr, size_t index) {

if (index >= arr->size) {

printf("Index out of bounds!\n");

return -1;

}

return arr->data[index]; // O(1) - just pointer + offset!

}

void dynarray_visualize(DynArray* arr) {

printf("[");

for (size_t i = 0; i < arr->capacity; i++) {

if (i < arr->size) {

printf("%d", arr->data[i]);

} else {

printf("_");

}

if (i < arr->capacity - 1) printf(", ");

}

printf("] size=%zu, capacity=%zu\n", arr->size, arr->capacity);

}

Design Notes

- Keep

sizeandcapacityin the same struct to make invariants explicit. - Use a growth factor (2x is simplest; 1.5x is more memory efficient).

- Always check allocation results and keep the old pointer until new memory is confirmed.

- Consider alignment if you plan to store structs with stricter alignment than

int.

Testing & Validation

- Push 1..N, then verify

arr[i] == i+1for all i. - Force multiple resizes by starting at capacity 1 and pushing 1,000+ items.

- Use ASan/Valgrind to confirm no leaks or invalid accesses.

Performance Experiments

- Compare iteration time between dynamic array and linked list for 1M elements.

- Track number of reallocations and total bytes copied during growth.

- Plot time per push as array grows to visualize amortization.

Dynamic Array Growth Timeline (capacity doubles)

Pushes: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 ...

Capacity: 1 2 4 4 8 8 8 8 16 ...

Copies: 0 1 2 0 4 0 0 0 8 ...

Why Arrays Are Cache-Friendly

ARRAY (contiguous memory):

┌───┬───┬───┬───┬───┬───┬───┬───┐

│ 1 │ 2 │ 3 │ 4 │ 5 │ 6 │ 7 │ 8 │ ← All in one cache line (64 bytes)

└───┴───┴───┴───┴───┴───┴───┴───┘

↑

CPU fetches entire line, gets 8 elements for price of 1!

LINKED LIST (scattered memory):

┌───┐ ┌───┐ ┌───┐ ┌───┐

│ 1 │────►│ 2 │────►│ 3 │────►│ 4 │

└───┘ └───┘ └───┘ └───┘

↑ cache miss ↑ cache miss ↑ cache miss

Each access may require fetching a new cache line!

The Amortization Insight

Why does doubling capacity give O(1) amortized push?

Operations to push n elements:

n pushes (always)

+ copy 1 element (when growing from 1 to 2)

+ copy 2 elements (when growing from 2 to 4)

+ copy 4 elements (when growing from 4 to 8)

+ ...

+ copy n/2 elements (when growing from n/2 to n)

Total copies = 1 + 2 + 4 + ... + n/2 = n - 1

Total work = n pushes + (n-1) copies ≈ 2n = O(n)

Average work per push = O(n) / n = O(1) ✓

Project 2: Linked List Toolkit

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Go, Python

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Pointers / Dynamic Memory

- Software or Tool: CLI list manipulation tool

- Main Book: C Programming: A Modern Approach by K.N. King

What you’ll build

A comprehensive linked list library (singly-linked, doubly-linked, circular) with visualization, plus a practical application: an undo/redo system for a text editor.

Deliverables:

sll.c/.h,dll.c/.h,cll.c/.hwith insert/delete/search- A list visualizer that prints node addresses and links

- Undo/redo demo with stack semantics

Why it teaches this concept

Linked lists are the opposite of arrays:

- Arrays: contiguous memory, random access, expensive insert/delete

- Linked lists: scattered memory, sequential access, cheap insert/delete

Understanding this trade-off is fundamental. You’ll also master pointers, which are essential for all complex data structures.

You also see why pointer-heavy structures often lose to arrays for iteration-heavy workloads despite better asymptotic insertion behavior.

Core challenges you’ll face

- Pointer manipulation (next, prev, head, tail) → maps to indirection

- Edge cases (empty list, one element, head/tail operations) → maps to boundary conditions

- Memory management (malloc each node, free on remove) → maps to manual memory

- Traversal (must walk from head) → maps to O(n) access

- Doubly-linked (can go backwards) → maps to trade-offs

- Sentinel nodes (optional) → maps to simplifying edge cases

Key Concepts

| Concept | Resource |

|---|---|

| Pointer Fundamentals | C Programming: A Modern Approach Chapter 11 - K.N. King |

| Linked List Operations | Introduction to Algorithms Chapter 10.2 - CLRS |

| Memory Allocation | The C Programming Language Chapter 7 - K&R |

| Data Structures in C | Mastering Algorithms with C Chapter 3-4 - Kyle Loudon |

Difficulty & Time

- Difficulty: Intermediate

- Time estimate: 1 week

- Prerequisites: Project 1 completed, comfortable with pointers

- Stretch goal: Add a list iterator API

Real World Outcome

$ ./linkedlist_demo

=== Singly Linked List ===

Insert 10 at head: [10] -> NULL

Insert 20 at head: [20] -> [10] -> NULL

Insert 30 at tail: [20] -> [10] -> [30] -> NULL

Insert 25 after 10: [20] -> [10] -> [25] -> [30] -> NULL

Memory layout:

Node@0x1000: data=20, next=0x1020

Node@0x1020: data=10, next=0x1040

Node@0x1040: data=25, next=0x1060

Node@0x1060: data=30, next=NULL

Delete 10: [20] -> [25] -> [30] -> NULL

(freed memory at 0x1020)

=== Doubly Linked List ===

[NULL <-> 20 <-> 25 <-> 30 <-> NULL]

Traverse forward: 20 -> 25 -> 30

Traverse backward: 30 -> 25 -> 20

=== Undo/Redo System Demo ===

Text: ""

> type "Hello"

Text: "Hello" [undo stack: "Hello"]

> type " World"

Text: "Hello World" [undo stack: "Hello", " World"]

> undo

Text: "Hello" [redo stack: " World"]

> undo

Text: "" [redo stack: " World", "Hello"]

> redo

Text: "Hello" [undo stack: "Hello"]

> type "!"

Text: "Hello!" [redo stack cleared!]

You should be able to point to any node address and explain which pointers connect to it and why.

The Core Question You’re Answering

When data is scattered across memory, how do I connect it safely and still support fast insert and delete operations? And how do I prevent pointer bugs when the structure changes frequently?

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Pointer ownership and lifetime (C Programming: A Modern Approach, Ch 11-12)

- Dynamic allocation and freeing (C Programming: A Modern Approach, Ch 17)

- Linked list operations (CLRS, Ch 10.2)

- Big-O trade-offs for sequential access (Algorithms, Fourth Edition, Ch 1.3)

- Sentinel nodes and edge cases (Mastering Algorithms with C, Ch 3)

Questions to Guide Your Design

- What invariants make a list correct (head, tail, NULL termination)?

- How do you delete a node when you do not have a pointer to the previous node?

- When should you use a sentinel node to simplify edge cases?

- How will you prevent memory leaks in undo/redo stacks?

- How will you handle duplicate values or stable ordering?

Thinking Exercise

Draw a 3-node doubly linked list and simulate deleting the middle node. Write down which pointers change in what order. Then simulate deleting the head and tail.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- Why is random access O(n) in a linked list?

- What is the difference between singly and doubly linked lists?

- How do you detect a cycle in a linked list?

- When is a linked list better than a dynamic array?

- How do you implement an LRU cache with a linked list?

- What is the memory overhead per node?

Hints in Layers

1) Start with a simple singly linked list with head and tail.

2) Add a size field to make correctness checks easy.

3) Move to a doubly linked list and implement delete-with-node-pointer.

4) Build undo/redo stacks on top of the list or stack abstraction.

5) Add a list_validate() function that checks invariants.

// Delete node in doubly linked list when you have the node pointer.

if (node->prev) node->prev->next = node->next;

else list->head = node->next;

if (node->next) node->next->prev = node->prev;

else list->tail = node->prev;

free(node);

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Why It Helps |

|---|---|---|

| Linked lists | CLRS, Ch 10.2 | Formal list operations |

| Pointers | C Programming: A Modern Approach, Ch 11 | Pointer manipulation |

| Memory management | The C Programming Language, Ch 7 | Allocation and freeing |

| Practical list APIs | Mastering Algorithms with C, Ch 3 | C-focused patterns |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem: “List prints garbage after delete”

- Why: Forgot to update

nextorprevon neighbors. - Fix: Update neighbors first, then free.

- Quick test: Delete head, tail, and middle in a 3-node list.

Problem: “Infinite loop during traversal”

- Why: Created a cycle unintentionally.

- Fix: Ensure tail->next is NULL and update pointers carefully.

- Quick test: Detect cycle with fast/slow pointers.

Problem: “Undo history leaks memory”

- Why: Actions not freed when cleared.

- Fix: Walk the stack and free each node and payload.

- Quick test: Use Valgrind after a long undo/redo session.

Problem: “Tail pointer is wrong”

- Why: Tail not updated on delete or insert at end.

- Fix: Update tail on head/tail operations.

- Quick test: Append 3 nodes, delete tail, and check tail address.

Definition of Done

- Singly, doubly, and circular lists pass unit tests

- All edge cases (empty, single, head/tail) handled

- Undo/redo behavior matches expected stack semantics

- No memory leaks under stress tests

- Runtime trade-offs documented in README

- Cycle detection test added (Floyd’s algorithm)

Learning Milestones

- Insert/delete at head is O(1) → You understand the advantage over arrays

- Find element is O(n) → You understand the disadvantage

- Doubly-linked enables O(1) delete given node → You understand the trade-off

- Undo/redo works → You understand why linked lists exist in real systems

- Memory cleanup is correct → You understand ownership and lifetimes

Implementation

Singly Linked List

typedef struct Node {

int data;

struct Node* next;

} Node;

typedef struct {

Node* head;

Node* tail;

size_t size;

} SinglyLinkedList;

// O(1) - just update head

void sll_push_front(SinglyLinkedList* list, int data) {

Node* new_node = malloc(sizeof(Node));

new_node->data = data;

new_node->next = list->head;

list->head = new_node;

if (list->tail == NULL) {

list->tail = new_node;

}

list->size++;

}

// O(1) - just update tail

void sll_push_back(SinglyLinkedList* list, int data) {

Node* new_node = malloc(sizeof(Node));

new_node->data = data;

new_node->next = NULL;

if (list->tail) {

list->tail->next = new_node;

} else {

list->head = new_node;

}

list->tail = new_node;

list->size++;

}

// O(n) - must traverse to find

Node* sll_find(SinglyLinkedList* list, int data) {

Node* current = list->head;

while (current) {

if (current->data == data) {

return current;

}

current = current->next;

}

return NULL;

}

// O(n) - must find previous node

void sll_delete(SinglyLinkedList* list, int data) {

if (!list->head) return;

// Special case: deleting head

if (list->head->data == data) {

Node* to_delete = list->head;

list->head = list->head->next;

if (list->tail == to_delete) {

list->tail = NULL;

}

free(to_delete);

list->size--;

return;

}

// Find previous node

Node* prev = list->head;

while (prev->next && prev->next->data != data) {

prev = prev->next;

}

if (prev->next) {

Node* to_delete = prev->next;

prev->next = to_delete->next;

if (list->tail == to_delete) {

list->tail = prev;

}

free(to_delete);

list->size--;

}

}

void sll_print(SinglyLinkedList* list) {

Node* current = list->head;

while (current) {

printf("[%d]", current->data);

if (current->next) printf(" -> ");

current = current->next;

}

printf(" -> NULL\n");

}

Doubly Linked List

typedef struct DNode {

int data;

struct DNode* prev;

struct DNode* next;

} DNode;

typedef struct {

DNode* head;

DNode* tail;

size_t size;

} DoublyLinkedList;

// O(1) delete when you have the node pointer!

void dll_delete_node(DoublyLinkedList* list, DNode* node) {

if (node->prev) {

node->prev->next = node->next;

} else {

list->head = node->next;

}

if (node->next) {

node->next->prev = node->prev;

} else {

list->tail = node->prev;

}

free(node);

list->size--;

}

Undo/Redo System (Practical Application)

typedef struct Action {

char* text; // The text that was added

struct Action* next;

} Action;

typedef struct {

char buffer[1024]; // Current text

Action* undo_stack; // Stack of actions to undo

Action* redo_stack; // Stack of actions to redo

} TextEditor;

void editor_type(TextEditor* editor, const char* text) {

// Add to buffer

strcat(editor->buffer, text);

// Push to undo stack

Action* action = malloc(sizeof(Action));

action->text = strdup(text);

action->next = editor->undo_stack;

editor->undo_stack = action;

// Clear redo stack (can't redo after new action)

while (editor->redo_stack) {

Action* to_free = editor->redo_stack;

editor->redo_stack = editor->redo_stack->next;

free(to_free->text);

free(to_free);

}

}

void editor_undo(TextEditor* editor) {

if (!editor->undo_stack) {

printf("Nothing to undo!\n");

return;

}

// Pop from undo stack

Action* action = editor->undo_stack;

editor->undo_stack = action->next;

// Remove text from buffer

size_t len = strlen(action->text);

editor->buffer[strlen(editor->buffer) - len] = '\0';

// Push to redo stack

action->next = editor->redo_stack;

editor->redo_stack = action;

}

void editor_redo(TextEditor* editor) {

if (!editor->redo_stack) {

printf("Nothing to redo!\n");

return;

}

// Pop from redo stack

Action* action = editor->redo_stack;

editor->redo_stack = action->next;

// Add text back to buffer

strcat(editor->buffer, action->text);

// Push to undo stack

action->next = editor->undo_stack;

editor->undo_stack = action;

}

Design Notes

- Store

head,tail, andsizeto simplify invariants and reduce traversal. - Use sentinel nodes if you want to simplify edge-case handling.

- Always update neighbors before freeing a node.

- Separate list logic from application logic (undo/redo) for clarity.

Testing & Validation

- Insert/delete head, tail, and middle nodes in lists of size 0, 1, and 3.

- Run a cycle-detection test (Floyd’s algorithm) after operations.

- Use Valgrind to confirm every node is freed.

Performance Experiments

- Compare delete-at-head vs delete-at-tail timing.

- Measure traversal time vs dynamic array for 1M elements.

- Track memory overhead per node (data + pointers).

Linked List Pointer Layout (singly linked)

head

|

v

[0x1000 | data=20 | next=0x1020] -> [0x1020 | data=10 | next=0x1040] -> NULL

Array vs Linked List: The Trade-off

| Operation | Array | Linked List | Winner |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access by index | O(1) | O(n) | Array |

| Insert at beginning | O(n) | O(1) | Linked List |

| Insert at end | O(1) amortized | O(1) with tail | Tie |

| Insert in middle | O(n) | O(1) if have node | Linked List |

| Delete | O(n) | O(1) if have node | Linked List |

| Memory overhead | Low | High (pointers) | Array |

| Cache performance | Excellent | Poor | Array |

When to use Linked Lists:

- Frequent insertions/deletions at arbitrary positions

- When you have pointers to nodes (e.g., LRU cache)

- When you need O(1) worst-case insert (not amortized)

When to use Arrays:

- Need random access

- Iterating through all elements (cache-friendly)

- Memory is tight (no pointer overhead)

Project 3: Stack Machine (Calculator & Mini VM)

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Go, Python

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Abstract Data Types / Language Implementation

- Software or Tool: RPN Calculator, Bytecode VM

- Main Book: Writing a C Compiler by Nora Sandler

What you’ll build

A Reverse Polish Notation (RPN) calculator and a simple stack-based virtual machine that executes bytecode—demonstrating why stacks are fundamental to computing.

Deliverables:

stack.c/.hwith push/pop/peekrpn.cevaluator with tokenizationvm.cwith a small bytecode instruction set

Why it teaches this concept

The stack is not just a data structure—it’s how computers work:

- Function calls use a stack (call stack)

- Expression evaluation uses a stack

- Undo operations use a stack

- Backtracking algorithms use a stack

- Your CPU has a hardware stack

Building a stack machine shows you why LIFO (Last In, First Out) is so fundamental.

You also learn to separate parsing from execution, which is core to compilers and interpreters.

Core challenges you’ll face

- LIFO semantics (last in, first out) → maps to stack discipline

- Expression parsing (infix to postfix) → maps to operator precedence

- VM execution (fetch-decode-execute) → maps to computation model

- Stack underflow/overflow → maps to error handling

- Tokenization (numbers and operators) → maps to parsing

Key Concepts

| Concept | Resource |

|---|---|

| Stack ADT | Introduction to Algorithms Chapter 10.1 - CLRS |

| Expression Evaluation | Algorithms, Fourth Edition Chapter 1.3 - Sedgewick |

| Stack Machines | Writing a C Compiler Chapter 3 - Nora Sandler |

| Shunting Yard Algorithm | Dijkstra’s original paper or Wikipedia |

| Call Stack | Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective Chapter 3 |

Difficulty & Time

- Difficulty: Intermediate-Advanced

- Time estimate: 1 week

- Prerequisites: Projects 1-2 completed

- Stretch goal: Add variables and a tiny memory model

Real World Outcome

$ ./rpn_calc

RPN Calculator (type 'quit' to exit)

> 3 4 +

Stack: [7]

Result: 7

> 5 *

Stack: [35]

Result: 35

> 2 3 4 + *

Stack: [35, 14]

Explanation: 2 * (3 + 4) = 14

Result: 14

> clear

Stack: []

=== Infix to RPN Demo ===

Infix: (3 + 4) * 5

Postfix: 3 4 + 5 *

Result: 35

=== Mini VM Demo ===

Bytecode: PUSH 10, PUSH 20, ADD, PUSH 5, MUL, PRINT

Executing...

PUSH 10 Stack: [10]

PUSH 20 Stack: [10, 20]

ADD Stack: [30]

PUSH 5 Stack: [30, 5]

MUL Stack: [150]

PRINT Output: 150

You should be able to trace the exact stack contents at every step.

The Core Question You’re Answering

How does a stack enable expression evaluation and program execution, and why does LIFO make computation simple? How does this relate to the real CPU call stack?

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Stack ADT operations (CLRS, Ch 10.1)

- Operator precedence and associativity (Algorithms, Fourth Edition, Ch 1.3)

- Tokenization and parsing (Writing a C Compiler, Ch 3)

- Error handling (underflow/overflow)

- Call stack frames and function calls (CSAPP, Ch 3)

Questions to Guide Your Design

- What is the minimal instruction set for a stack VM?

- How will you represent tokens and opcodes?

- How will you report errors without crashing?

- How do you show the stack state after each step?

- How will you handle negative numbers and multi-digit tokens?

Thinking Exercise

Convert (8 - 3) * (2 + 5) to RPN by hand, then evaluate it using a stack trace. Compare the trace to a standard infix evaluation.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- Why is a stack good for parsing expressions?

- What is the difference between a call stack and a data stack?

- How would you implement recursion without a call stack?

- What are common stack overflow conditions?

- How do you parse infix expressions efficiently?

- Why do many bytecode VMs use a stack instead of registers?

Hints in Layers

1) Build a fixed-size stack first, then consider a dynamic version.

2) Implement RPN evaluation with a simple token loop.

3) Add shunting-yard for infix to postfix conversion.

4) Extend to a bytecode VM with opcodes like PUSH, ADD, MUL.

5) Add DUP and SWAP opcodes to experiment with stack manipulation.

if (is_number(token)) stack_push(&s, atoi(token));

else {

int b = stack_pop(&s);

int a = stack_pop(&s);

stack_push(&s, apply_op(token[0], a, b));

}

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Why It Helps |

|---|---|---|

| Stack operations | CLRS, Ch 10.1 | Core ADT behavior |

| Expression parsing | Algorithms, Fourth Edition, Ch 1.3 | Shunting-yard and stacks |

| VM design | Writing a C Compiler, Ch 3 | Stack machines |

| Call stack | Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective, Ch 3 | How functions work |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem: “Stack underflow on operator”

- Why: Missing operands or tokenization error.

- Fix: Validate token stream and check stack size before pop.

- Quick test: Evaluate

3 +and confirm clean error.

Problem: “Wrong precedence”

- Why: Shunting-yard precedence table incorrect.

- Fix: Implement a clear precedence function and unit test.

- Quick test: Compare

3 + 4 * 5vs(3 + 4) * 5.

Problem: “VM executes garbage”

- Why: Instruction pointer or opcode mapping wrong.

- Fix: Print each instruction and stack state.

- Quick test: Run a 3-instruction program and verify output.

Problem: “Tokenizer merges numbers”

- Why: Missing whitespace handling or digit parsing.

- Fix: Use

strtokor a hand-written scanner. - Quick test: Evaluate

12 3 +and confirm result is 15.

Definition of Done

- RPN evaluator produces correct results for test cases

- Infix to postfix conversion matches known outputs

- VM can execute a small bytecode program end-to-end

- Error handling covers underflow/overflow and bad tokens

- Stack state prints after each step for visibility

- Additional opcodes (DUP, SWAP) are tested

Learning Milestones

- RPN calculator works → You understand postfix evaluation

- Infix to postfix conversion works → You understand the shunting-yard algorithm

- VM executes bytecode → You understand stack machines

- You see the call stack in action → You understand how functions work

- Errors are handled gracefully → You understand robust execution

Implementation

Stack Data Structure

#define STACK_MAX 256

typedef struct {

int items[STACK_MAX];

int top;

} Stack;

void stack_init(Stack* s) {

s->top = -1;

}

int stack_is_empty(Stack* s) {

return s->top == -1;

}

int stack_is_full(Stack* s) {

return s->top == STACK_MAX - 1;

}

void stack_push(Stack* s, int value) {

if (stack_is_full(s)) {

printf("Stack overflow!\n");

exit(1);

}

s->items[++s->top] = value;

}

int stack_pop(Stack* s) {

if (stack_is_empty(s)) {

printf("Stack underflow!\n");

exit(1);

}

return s->items[s->top--];

}

int stack_peek(Stack* s) {

if (stack_is_empty(s)) {

printf("Stack empty!\n");

exit(1);

}

return s->items[s->top];

}

void stack_print(Stack* s) {

printf("Stack: [");

for (int i = 0; i <= s->top; i++) {

printf("%d", s->items[i]);

if (i < s->top) printf(", ");

}

printf("]\n");

}

RPN Calculator

int evaluate_rpn(const char* expression) {

Stack stack;

stack_init(&stack);

char* expr = strdup(expression);

char* token = strtok(expr, " ");

while (token != NULL) {

if (isdigit(token[0]) || (token[0] == '-' && isdigit(token[1]))) {

// It's a number - push it

stack_push(&stack, atoi(token));

} else {

// It's an operator - pop operands and compute

int b = stack_pop(&stack);

int a = stack_pop(&stack);

int result;

switch (token[0]) {

case '+': result = a + b; break;

case '-': result = a - b; break;

case '*': result = a * b; break;

case '/': result = a / b; break;

default:

printf("Unknown operator: %s\n", token);

exit(1);

}

stack_push(&stack, result);

}

printf(" Token: %-4s ", token);

stack_print(&stack);

token = strtok(NULL, " ");

}

free(expr);

return stack_pop(&stack);

}

Shunting-Yard Algorithm (Infix to Postfix)

int precedence(char op) {

switch (op) {

case '+': case '-': return 1;

case '*': case '/': return 2;

default: return 0;

}

}

void infix_to_postfix(const char* infix, char* postfix) {

Stack op_stack;

stack_init(&op_stack);

int j = 0;

for (int i = 0; infix[i]; i++) {

char c = infix[i];

if (isdigit(c)) {

postfix[j++] = c;

postfix[j++] = ' ';

} else if (c == '(') {

stack_push(&op_stack, c);

} else if (c == ')') {

while (!stack_is_empty(&op_stack) && stack_peek(&op_stack) != '(') {

postfix[j++] = stack_pop(&op_stack);

postfix[j++] = ' ';

}

stack_pop(&op_stack); // Remove '('

} else if (c == '+' || c == '-' || c == '*' || c == '/') {

while (!stack_is_empty(&op_stack) &&

precedence(stack_peek(&op_stack)) >= precedence(c)) {

postfix[j++] = stack_pop(&op_stack);

postfix[j++] = ' ';

}

stack_push(&op_stack, c);

}

}

while (!stack_is_empty(&op_stack)) {

postfix[j++] = stack_pop(&op_stack);

postfix[j++] = ' ';

}

postfix[j] = '\0';

}

Mini Stack-Based VM

typedef enum {

OP_PUSH,

OP_POP,

OP_ADD,

OP_SUB,

OP_MUL,

OP_DIV,

OP_PRINT,

OP_HALT

} OpCode;

typedef struct {

OpCode op;

int operand;

} Instruction;

void vm_execute(Instruction* program, int length) {

Stack stack;

stack_init(&stack);

for (int ip = 0; ip < length; ip++) {

Instruction inst = program[ip];

switch (inst.op) {

case OP_PUSH:

printf(" PUSH %d\t", inst.operand);

stack_push(&stack, inst.operand);

break;

case OP_ADD: {

printf(" ADD\t\t");

int b = stack_pop(&stack);

int a = stack_pop(&stack);

stack_push(&stack, a + b);

break;

}

case OP_MUL: {

printf(" MUL\t\t");

int b = stack_pop(&stack);

int a = stack_pop(&stack);

stack_push(&stack, a * b);

break;

}

case OP_PRINT:

printf(" PRINT\t\t");

printf("Output: %d\n", stack_peek(&stack));

break;

case OP_HALT:

printf(" HALT\n");

return;

}

stack_print(&stack);

}

}

// Example: Compute (10 + 20) * 5

int main() {

Instruction program[] = {

{OP_PUSH, 10},

{OP_PUSH, 20},

{OP_ADD, 0},

{OP_PUSH, 5},

{OP_MUL, 0},

{OP_PRINT, 0},

{OP_HALT, 0}

};

printf("Executing bytecode:\n");

vm_execute(program, sizeof(program) / sizeof(Instruction));

return 0;

}

Design Notes

- Keep stack operations small and predictable; they are hot paths.

- Make opcode decoding explicit and traceable.

- Use a separate tokenization step so parsing errors are isolated.

- Log stack state after each instruction during debugging.

Testing & Validation

- Evaluate known RPN cases and compare to infix evaluation.

- Verify shunting-yard output matches reference conversions.

- Test VM with a minimal program and a longer program.

Performance Experiments

- Measure RPN evaluation throughput for long expressions.

- Compare dynamic stack vs fixed-size stack.

- Track error rates by fuzzing random token streams.

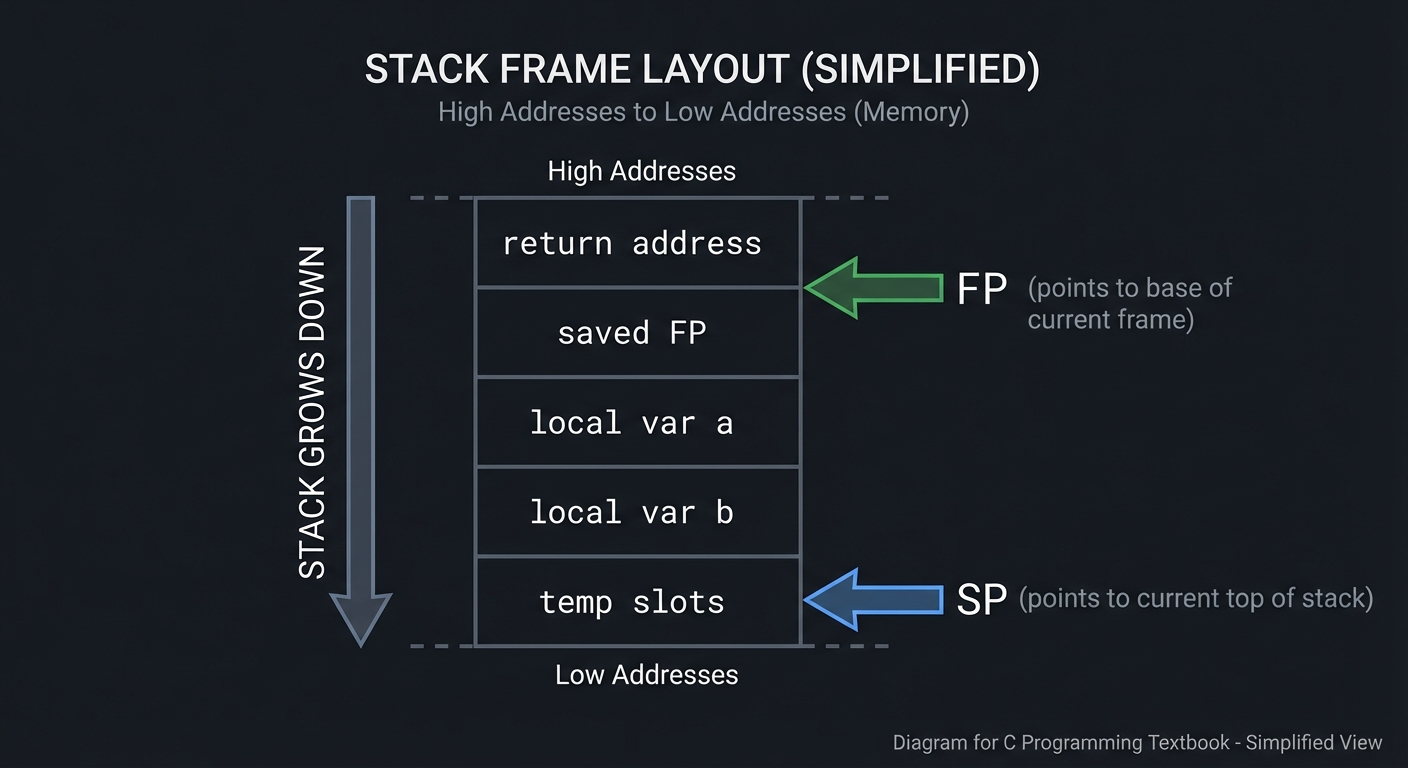

Stack Frame Layout (simplified)

High addresses

| return address |

| saved FP |

| local var a |

| local var b |

| temp slots |

SP -> (grows down)

Low addresses

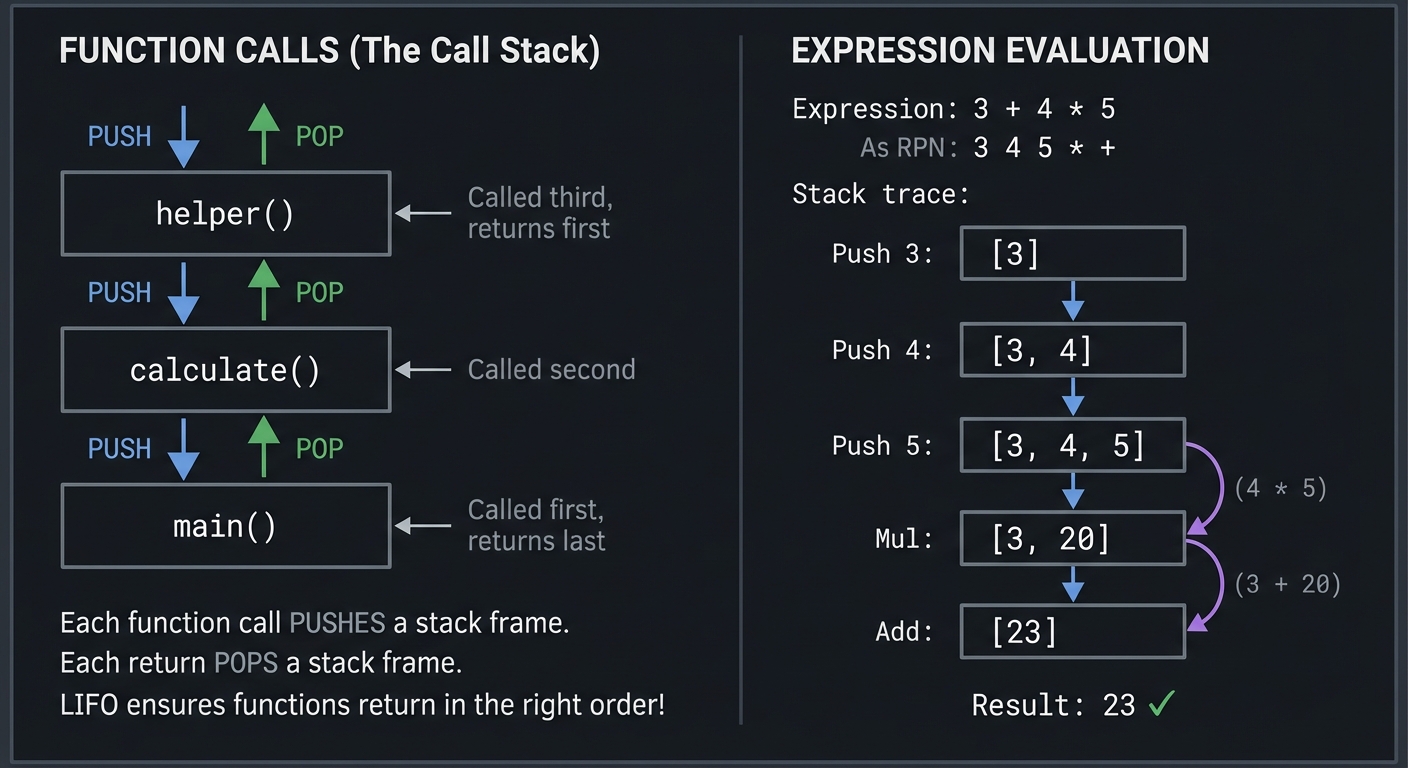

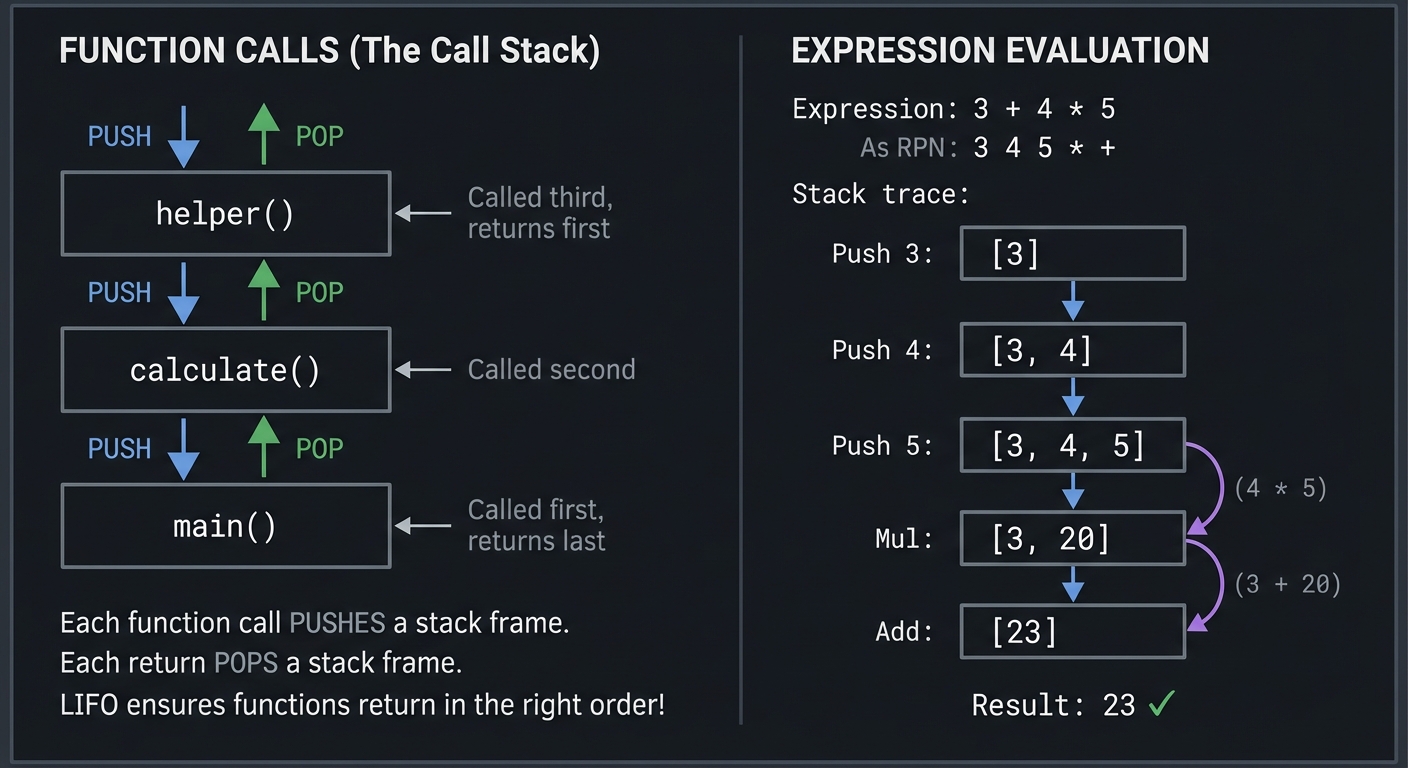

Why Stacks Are Everywhere

FUNCTION CALLS (The Call Stack):

┌─────────────────┐

│ main() │ ← Called first, returns last

├─────────────────┤

│ calculate() │ ← Called second

├─────────────────┤

│ helper() │ ← Called third, returns first

└─────────────────┘

Each function call PUSHES a stack frame.

Each return POPS a stack frame.

LIFO ensures functions return in the right order!

EXPRESSION EVALUATION:

Expression: 3 + 4 * 5

As RPN: 3 4 5 * +

Stack trace:

Push 3: [3]

Push 4: [3, 4]

Push 5: [3, 4, 5]

Mul: [3, 20] (4 * 5)

Add: [23] (3 + 20)

Result: 23 ✓

Project 4: Queue Systems (Task Scheduler & BFS)

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Go, Python

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 2. The “Micro-SaaS / Pro Tool”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Abstract Data Types / Systems Programming

- Software or Tool: Job Queue, BFS Maze Solver

- Main Book: Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces by Remzi H. Arpaci-Dusseau

What you’ll build

A multi-priority task scheduler using queues, plus a visual maze solver using BFS—demonstrating why FIFO (First In, First Out) enables fairness and level-order processing.

Deliverables:

queue.c/.hwith circular buffer implementation- Multi-level scheduler simulation with time slices

- BFS maze solver with path reconstruction

Why it teaches this concept

Queues are about fairness and ordering:

- First come, first served (FIFO)

- Level-by-level processing (BFS)

- Buffering between producer and consumer

Understanding queues is essential for:

- Operating system schedulers

- Network packet handling

- Message queues (Kafka, RabbitMQ)

- Breadth-first search

Queues are the default structure whenever order and fairness matter.

Core challenges you’ll face

- FIFO semantics (first in, first out) → maps to fairness

- Circular buffer (efficient array-based queue) → maps to memory efficiency

- Priority queues (not FIFO - will connect to heaps) → maps to scheduling

- Producer-consumer (handling different speeds) → maps to buffering

- Fairness vs throughput → maps to system trade-offs

Key Concepts

| Concept | Resource |

|---|---|

| Queue ADT | Introduction to Algorithms Chapter 10.1 - CLRS |

| Circular Buffers | The Linux Programming Interface Chapter 44 - Kerrisk |

| BFS Algorithm | Introduction to Algorithms Chapter 22.2 - CLRS |

| Process Scheduling | Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces Chapter 7 - OSTEP |

| Producer/Consumer | Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces Chapter 30 - OSTEP |

Difficulty & Time

- Difficulty: Intermediate

- Time estimate: 1 week

- Prerequisites: Projects 1-3 completed

- Stretch goal: Add a deque and implement 0-1 BFS

Real World Outcome

$ ./task_scheduler

=== Task Scheduler with Multiple Queues ===

Adding tasks:

[HIGH] Task: "Handle interrupt" -> High priority queue

[MEDIUM] Task: "Process user input" -> Medium priority queue

[LOW] Task: "Background sync" -> Low priority queue

[HIGH] Task: "Memory page fault" -> High priority queue

[MEDIUM] Task: "Render frame" -> Medium priority queue

Processing (high priority first, then FIFO within each level):

[1] HIGH: "Handle interrupt"

[2] HIGH: "Memory page fault"

[3] MEDIUM: "Process user input"

[4] MEDIUM: "Render frame"

[5] LOW: "Background sync"

=== BFS Maze Solver ===

Maze:

█████████████

█S █ █

███ ███ █████

█ █ █ █

█ █████ █ █ █

█ █ █

█████████ ███

█ █E█

█████████████

Solving with BFS...

Step 1: Exploring (1,1) - Added neighbors to queue

Step 2: Exploring (1,2) - Added neighbors to queue

...

Solution found! Path length: 24 steps

█████████████

█S....█.....█

███.███.█████

█...█...█...█

█.█████.█.█.█

█.......█...█

█████████.███

█.........█E█

█████████████

Why BFS finds shortest path: It explores level-by-level!

Level 0: Start (1,1)

Level 1: All cells 1 step away

Level 2: All cells 2 steps away

...

First time we reach End = shortest path!

You should be able to justify why FIFO guarantees the first time you reach a node is the shortest path.

The Core Question You’re Answering

How does FIFO ordering create fairness and shortest-path guarantees, and how do queues model real scheduling systems? What trade-offs appear when you add priorities?

Concepts You Must Understand First

- Queue ADT operations (CLRS, Ch 10.1)

- Circular buffer logic (The Linux Programming Interface, Ch 44)

- BFS and level-order traversal (CLRS, Ch 22.2)

- Scheduling basics (Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces, Ch 7)

- Producer-consumer queues (Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces, Ch 30)

Questions to Guide Your Design

- How do you avoid O(n) shifts when dequeuing?

- What does “full” mean in a ring buffer?

- How do you represent multiple priority levels cleanly?

- How do you reconstruct the BFS path?

- How will you avoid starvation in the priority scheduler?

Thinking Exercise

Draw a ring buffer of size 8. Enqueue 6 items, dequeue 4, enqueue 3 more. Track front, rear, and size. Now repeat without using size and see where you get stuck.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- Why does BFS find the shortest path in unweighted graphs?

- How do you implement a queue with two stacks?

- What is the difference between a queue and a deque?

- How would you build a multilevel feedback queue?

- Why is a circular buffer more efficient than shifting an array?

- How would you handle backpressure between producer and consumer?

Hints in Layers

1) Implement a fixed-size queue with front, rear, and size.

2) Add modulo arithmetic for wrap-around.

3) Build multiple queues for priority scheduling.

4) For BFS, track parents to reconstruct the path.

5) Add a simple aging mechanism to avoid starvation.

q->rear = (q->rear + 1) % QUEUE_CAPACITY;

q->front = (q->front + 1) % QUEUE_CAPACITY;

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Why It Helps |

|---|---|---|

| Queue ADT | CLRS, Ch 10.1 | Formal operations |

| Circular buffers | The Linux Programming Interface, Ch 44 | Practical ring buffers |

| BFS | CLRS, Ch 22.2 | Correctness of BFS |

| Scheduling | Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces, Ch 7 | Real systems context |

| Concurrency | Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces, Ch 30 | Producer/consumer patterns |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem: “Queue appears full when it is not”

- Why:

frontandrearwrap incorrectly. - Fix: Track

sizeexplicitly or keep one empty slot. - Quick test: Enqueue/dequeue in a loop of 1000 ops.

Problem: “BFS path is wrong”

- Why: Parent pointers not set for every visited node.

- Fix: Set parent when enqueuing, not when dequeuing.

- Quick test: Compare path length with distance array.

Problem: “Priority queue starves low tasks”

- Why: Strict priority scheduling without aging.

- Fix: Add aging or round-robin per priority.

- Quick test: Run 100 high tasks and ensure low tasks eventually run.

Problem: “BFS revisits nodes”

- Why: Visited set not updated on enqueue.

- Fix: Mark visited as soon as you enqueue.

- Quick test: Run BFS on a cyclic graph and verify no infinite loop.

Definition of Done

- Circular buffer queue passes wrap-around tests

- Task scheduler respects priority and FIFO within levels

- BFS finds shortest path and prints it

- Queue invariants checked after each op

- Stress tests run without overflow or underflow errors

- Starvation avoidance tested with aging

Learning Milestones

- Basic queue works → You understand FIFO

- Circular buffer is efficient → You understand wrapping

- Priority scheduler works → You understand scheduling

- BFS finds shortest path → You understand level-order processing

- Fairness is visible → You can reason about starvation

Implementation

Queue with Circular Buffer

#define QUEUE_CAPACITY 100

typedef struct {

int items[QUEUE_CAPACITY];

int front; // Index to dequeue from

int rear; // Index to enqueue to

int size;

} Queue;

void queue_init(Queue* q) {

q->front = 0;

q->rear = 0;

q->size = 0;

}

int queue_is_empty(Queue* q) {

return q->size == 0;

}

int queue_is_full(Queue* q) {

return q->size == QUEUE_CAPACITY;

}

void queue_enqueue(Queue* q, int value) {

if (queue_is_full(q)) {

printf("Queue overflow!\n");

return;

}

q->items[q->rear] = value;

q->rear = (q->rear + 1) % QUEUE_CAPACITY; // Wrap around!

q->size++;

}

int queue_dequeue(Queue* q) {

if (queue_is_empty(q)) {

printf("Queue underflow!\n");

return -1;

}

int value = q->items[q->front];

q->front = (q->front + 1) % QUEUE_CAPACITY; // Wrap around!

q->size--;

return value;

}

// Visualize circular buffer

void queue_visualize(Queue* q) {

printf("Queue (front=%d, rear=%d, size=%d):\n[", q->front, q->rear, q->size);

for (int i = 0; i < QUEUE_CAPACITY && i < 20; i++) {

if (i >= q->front && i < q->front + q->size) {

printf("%d", q->items[i % QUEUE_CAPACITY]);

} else {

printf("_");

}

if (i < 19) printf(",");

}

printf("...]\n");

}

Multi-Level Priority Scheduler

typedef enum { HIGH, MEDIUM, LOW, NUM_PRIORITIES } Priority;

typedef struct {

char name[64];

Priority priority;

} Task;

typedef struct {

Queue queues[NUM_PRIORITIES];

Task tasks[1000]; // Task storage

int task_count;

} Scheduler;

void scheduler_add_task(Scheduler* s, const char* name, Priority priority) {

Task* task = &s->tasks[s->task_count];

strcpy(task->name, name);

task->priority = priority;

// Add task index to appropriate queue

queue_enqueue(&s->queues[priority], s->task_count);

s->task_count++;

const char* priority_names[] = {"HIGH", "MEDIUM", "LOW"};

printf("Added [%s] task: \"%s\"\n", priority_names[priority], name);

}

Task* scheduler_get_next(Scheduler* s) {

// Check high priority first, then medium, then low

for (int p = HIGH; p < NUM_PRIORITIES; p++) {

if (!queue_is_empty(&s->queues[p])) {

int task_idx = queue_dequeue(&s->queues[p]);

return &s->tasks[task_idx];

}

}

return NULL; // No tasks

}

BFS Maze Solver

#define MAZE_SIZE 13

typedef struct {

int row, col;

int distance;

} Cell;

int bfs_solve_maze(char maze[MAZE_SIZE][MAZE_SIZE],

int start_row, int start_col,

int end_row, int end_col) {

// Queue for BFS

Cell queue[MAZE_SIZE * MAZE_SIZE];

int front = 0, rear = 0;

// Visited array

int visited[MAZE_SIZE][MAZE_SIZE] = {0};

// Parent tracking for path reconstruction

int parent_row[MAZE_SIZE][MAZE_SIZE];

int parent_col[MAZE_SIZE][MAZE_SIZE];

// Start BFS

queue[rear++] = (Cell){start_row, start_col, 0};

visited[start_row][start_col] = 1;

int directions[4][2] = {{-1, 0}, {1, 0}, {0, -1}, {0, 1}};

while (front < rear) {

Cell current = queue[front++];

// Found the end!

if (current.row == end_row && current.col == end_col) {

// Reconstruct path

int r = end_row, c = end_col;

while (r != start_row || c != start_col) {

maze[r][c] = '.';

int pr = parent_row[r][c];

int pc = parent_col[r][c];

r = pr;

c = pc;

}

maze[start_row][start_col] = 'S';

maze[end_row][end_col] = 'E';

return current.distance;

}

// Explore neighbors

for (int d = 0; d < 4; d++) {

int nr = current.row + directions[d][0];

int nc = current.col + directions[d][1];

if (nr >= 0 && nr < MAZE_SIZE && nc >= 0 && nc < MAZE_SIZE &&

maze[nr][nc] != '#' && !visited[nr][nc]) {

visited[nr][nc] = 1;

parent_row[nr][nc] = current.row;

parent_col[nr][nc] = current.col;

queue[rear++] = (Cell){nr, nc, current.distance + 1};

}

}

}

return -1; // No path found

}

Design Notes

- Use a ring buffer to keep enqueue/dequeue O(1).

- Track

sizeexplicitly to disambiguate full vs empty. - For BFS, mark nodes visited when enqueued, not when dequeued.

- Keep scheduler queues separate to enforce strict priority.

Testing & Validation

- Enqueue/dequeue in a loop of 10,000 ops and verify order.

- Verify BFS path length against a known shortest path.

- Test scheduler fairness with mixed priority loads.

Performance Experiments

- Compare array-shift queue vs ring buffer for 100k ops.

- Measure BFS runtime on sparse vs dense grids.

- Measure scheduler throughput with high-priority spikes.

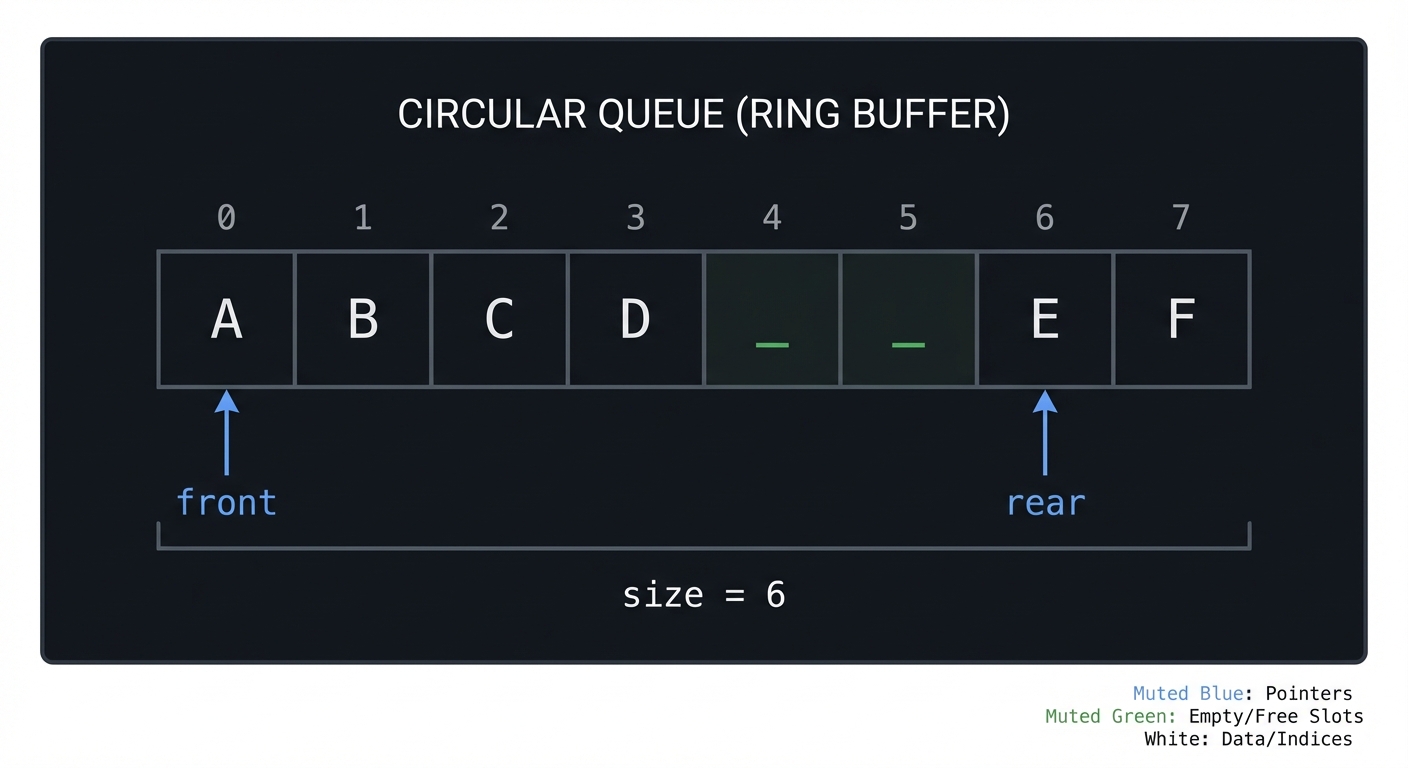

Queue Ring Buffer (capacity=8)

index: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

data: A B C D _ _ E F

front -> 0

rear -> 6 (next insert)

size -> 6

Stack vs Queue: When to Use Each

| Use Case | Stack (LIFO) | Queue (FIFO) |

|---|---|---|

| Undo/Redo | ✓ | |

| Function calls | ✓ | |

| DFS traversal | ✓ | |

| Expression evaluation | ✓ | |

| Task scheduling | ✓ | |

| BFS traversal | ✓ | |

| Print queue | ✓ | |

| Message buffering | ✓ |

Key insight:

- Stack: When most recent is most important

- Queue: When order of arrival matters (fairness)

Project 5: Hash Table (Dictionary & Cache)

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Python, Go

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 4. The “Open Core” Infrastructure

- Difficulty: Level 4: Expert

- Knowledge Area: Data Structures / Algorithms

- Software or Tool: Key-Value Store, LRU Cache

- Main Book: Introduction to Algorithms by CLRS

What you’ll build

A complete hash table implementation with multiple collision resolution strategies (chaining, open addressing), plus a practical LRU (Least Recently Used) cache.

Deliverables:

hash_chaining.candhash_open.c- Benchmark script comparing probe lengths and collisions

lru_cache.cwith O(1) get/put

Why it teaches this concept

Hash tables are the most practically important data structure:

- O(1) average lookup, insert, delete

- Backbone of databases, caches, dictionaries

- Used everywhere: Python dicts, JavaScript objects, database indexes

Understanding hash tables means understanding:

- Hash functions (turning keys into indices)

- Collision resolution (when two keys hash to same index)

- Load factor and resizing

- Trade-offs between time and space

This project also teaches you why “average O(1)” depends on your hash quality and resize policy.

Core challenges you’ll face

- Hash function design (distribute keys uniformly) → maps to hashing theory

- Collision handling (chaining vs open addressing) → maps to trade-offs

- Load factor (when to resize) → maps to performance tuning

- LRU eviction (combining hash table with linked list) → maps to real caches

- Probe clustering (open addressing) → maps to performance degradation

Resources for Key Challenges

- Real-world Applications of Hash Tables - Practical use cases

- GeeksforGeeks: Real-life Applications of DSA - Hash tables in databases, caching

Key Concepts

| Concept | Resource |

|---|---|

| Hash Functions | Introduction to Algorithms Chapter 11 - CLRS |

| Collision Resolution | Algorithms, Fourth Edition Chapter 3.4 - Sedgewick |

| Universal Hashing | Introduction to Algorithms Chapter 11.3.3 - CLRS |

| LRU Cache Design | LeetCode Problem 146 explanation |

| Hash tables in C | Mastering Algorithms with C Chapter 8 |

Difficulty & Time

- Difficulty: Advanced

- Time estimate: 2 weeks

- Prerequisites: Projects 1-2 completed, understanding of modular arithmetic

- Stretch goal: Add robin hood hashing

Real World Outcome

$ ./hashtable_demo

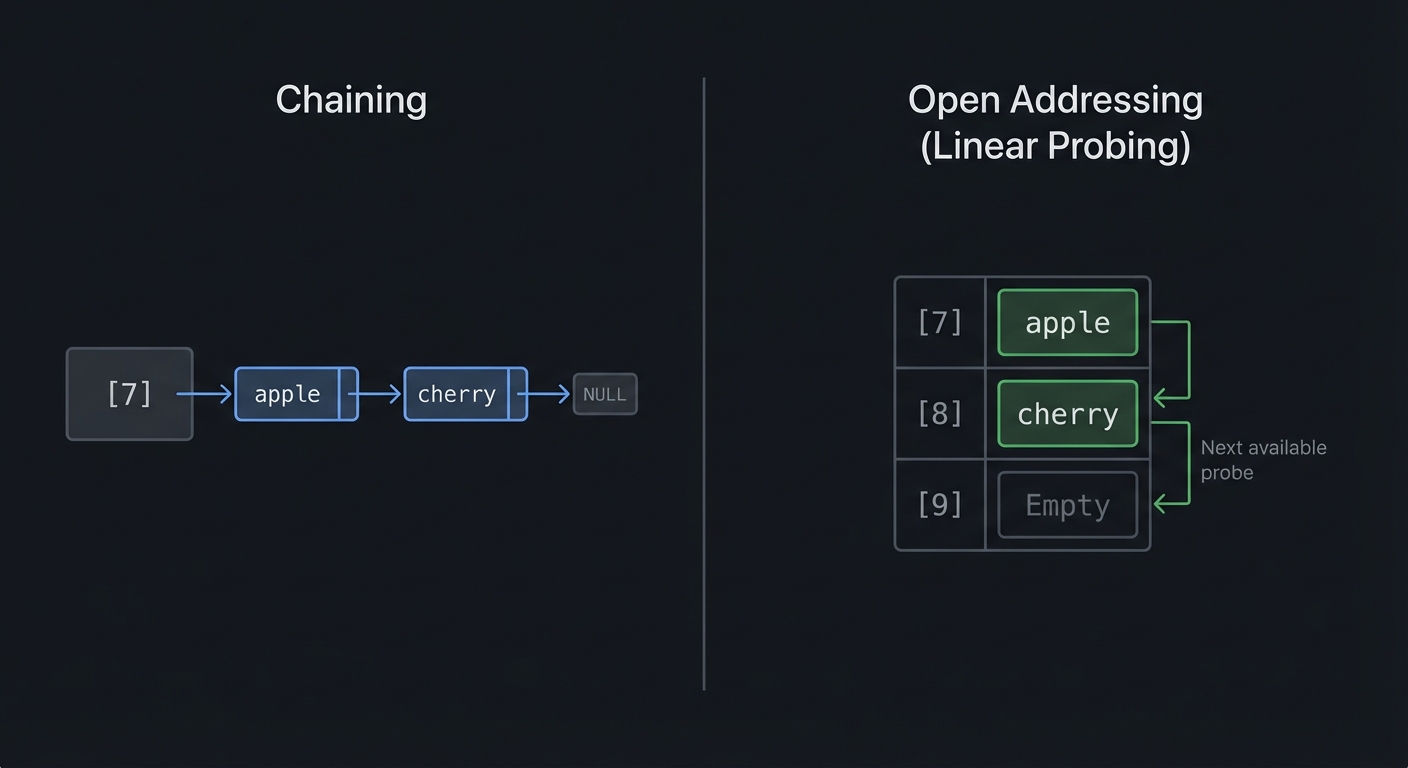

=== Hash Table with Chaining ===

Initial capacity: 16, load factor threshold: 0.75

put("apple", 5) -> hash("apple") = 7, bucket 7

put("banana", 3) -> hash("banana") = 2, bucket 2

put("cherry", 8) -> hash("cherry") = 7, bucket 7 (collision with apple!)

Bucket visualization:

[0]: empty

[1]: empty

[2]: ["banana" -> 3]

...

[7]: ["apple" -> 5] -> ["cherry" -> 8] ← Chained!

...

get("cherry") = 8 (found in bucket 7, 2nd in chain)

get("mango") = NOT FOUND

=== Open Addressing (Linear Probing) ===

put("apple", 5) -> hash = 7, slot 7

put("cherry", 8) -> hash = 7, collision! probe slot 8

Table visualization:

[0]: empty

...

[7]: ("apple", 5)

[8]: ("cherry", 8) ← Probed here!

...

=== Resize Demo ===

Adding 12 items... load factor = 0.75

RESIZE triggered! 16 -> 32 buckets