Learn C Programming: From Zero to Professional Mastery

Goal: Deeply understand C programming from first principles to professional-level expertise—mastering memory management, pointers, data structures, system programming, and the patterns that make C code robust, secure, and maintainable. You’ll understand not just how to write C, but why C works the way it does, how to debug at the lowest levels, and how to write code that would pass review at organizations like the Linux kernel team or embedded systems companies.

Introduction

C is a systems programming language designed for explicit control over memory, data layout, and execution cost. This guide treats C as both a language and a machine model: you will learn the syntax, but more importantly you will learn how code maps to memory, CPU instructions, system calls, and hardware boundaries.

- What is C? A small language with a large execution model, used where predictability and low-level access matter.

- What problem does it solve? It gives you direct control over layout, lifetime, ABI compatibility, and performance-critical paths.

- What you will build: 15 progressive projects plus one capstone kernel path, from memory introspection to concurrency, networking, parsing, and embedded systems.

- Scope: core C, systems interfaces, debugging, and architecture-level reasoning.

- Out of scope: GUI frameworks, heavy metaprogramming, and language-specific runtime abstractions.

Big-picture view:

Source C -> Compiler/Linker -> Process Image -> Syscalls -> Kernel -> Hardware

^ | | | |

| v v v v

Data structures ABI Memory model IPC/IO Devices

How to Use This Guide

- Read the theory primer before implementing projects that depend on it.

- Build projects in order unless a recommended path says otherwise.

- Keep a debugging journal: bug symptom, root cause, fix, and verification command.

- After each project, run its Definition of Done checklist before moving on.

- Revisit the Concept Summary and Project-to-Concept Map whenever you get stuck.

Prerequisites & Background Knowledge

Essential Prerequisites (Must Have)

- Basic C syntax (

if, loops, functions, arrays, structs, pointers) - Command-line usage (

gcc/clang,make, shell basics) - Basic Linux process model (process IDs, files, standard streams)

- Recommended reading: C Programming: A Modern Approach (K. N. King), chapters 1-13

Helpful But Not Required

- Assembly reading basics for x86-64 or ARM

- Familiarity with

gdb,strace, andperf - Intro operating systems concepts (virtual memory, scheduling)

Self-Assessment Questions

- Can you explain the difference between stack and heap without hand-waving?

- Can you write and debug a function that takes and returns pointers?

- Can you compile, link, and run a multi-file C project from the terminal?

Development Environment Setup Required Tools:

clangorgcc(C17/C23-capable)makegdborlldbvalgrindor sanitizers (-fsanitize=address,undefined)

Recommended Tools:

strace/dtrussperfor equivalent profilerclang-tidy/cppcheck

Testing Your Setup:

$ cc --version

$ make --version

$ gdb --version

Expected output: each command prints an installed version and exits successfully.

Time Investment

- Simple projects: 4-8 hours

- Moderate projects: 10-20 hours

- Complex projects: 20-40 hours

- Full sprint including capstone: ~4-8 months part-time

Important Reality Check C rewards precision and punishes assumptions. Expect to spend significant time debugging memory, lifetime, and concurrency issues. That difficulty is the learning value.

Big Picture / Mental Model

The learning flow is intentionally cumulative: memory model first, then abstractions, then systems integration.

[Memory + Pointers]

|

v

[Data Structures + APIs]

|

v

[Toolchain + Build + Debug]

|

v

[OS Interfaces: files/processes/sockets/threads]

|

v

[Production-style Systems Projects]

Why C Matters

C remains foundational for systems software where latency control, memory layout, and ABI stability matter.

- TIOBE Index (January 2026): C is ranked #2 with 10.99% share (TIOBE Index).

- Stack Overflow Developer Survey 2025: C is used by 22.0% of all respondents and 19.1% of professional developers (Stack Overflow Survey 2025).

- Memory-safety pressure in critical software (2024): A joint cybersecurity review of critical open-source projects found that memory-unsafe languages still dominate large portions of critical codebases (Cyber.gov.au report).

- Language evolution is active: ISO published ISO/IEC 9899:2024 (C23), proving C is still actively standardized (ISO catalog entry).

Context & Evolution

In 1972, Dennis Ritchie created C at Bell Labs to rewrite Unix with portability and predictable performance. That design choice still defines C today: direct memory access, minimal runtime assumptions, and explicit programmer responsibility.

Modern systems still depend on this model:

- OS kernels and low-level runtime libraries

- database, networking, and storage engines

- compilers, interpreters, and embedded firmware

C is still one of the clearest paths for learning how computers actually execute programs. It teaches constraints and tradeoffs that transfer to every higher-level language.

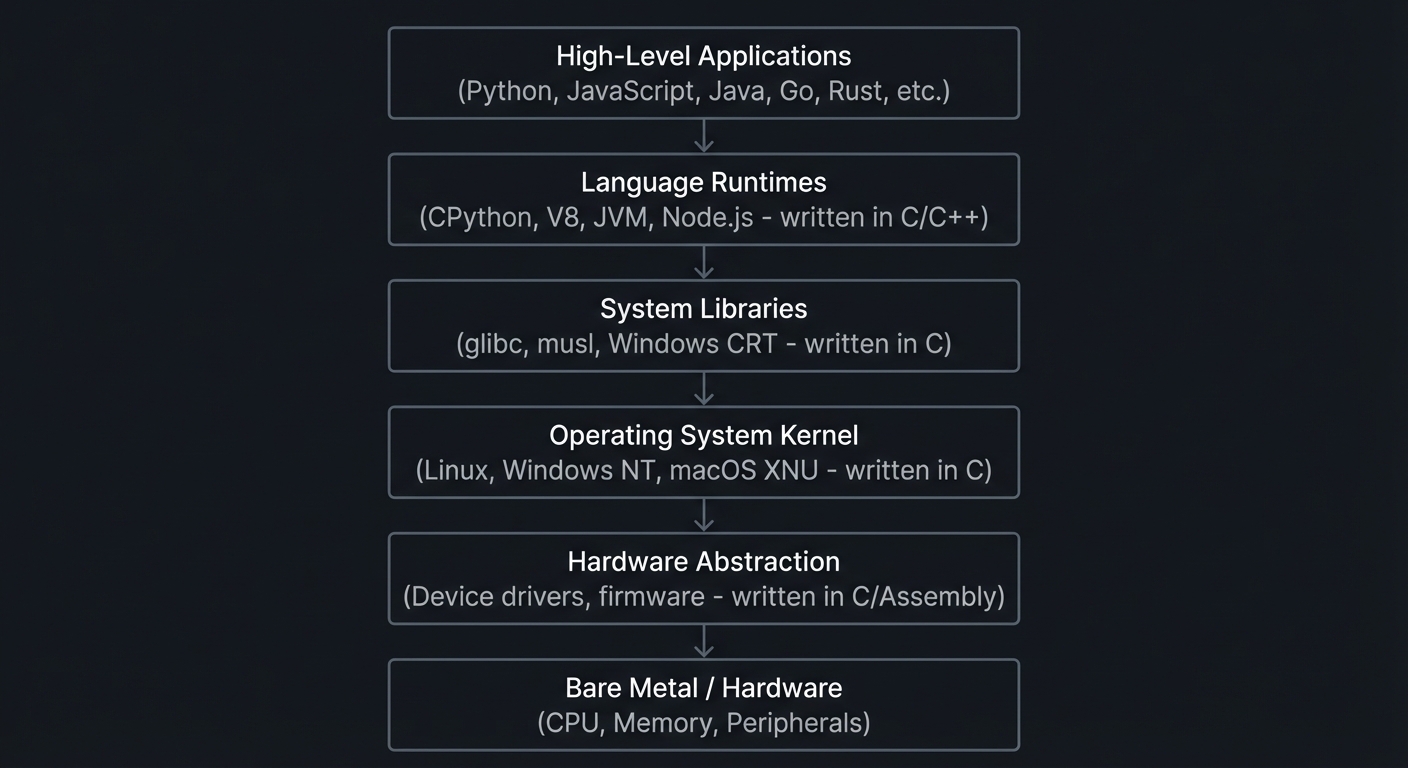

C’s Position in the Software Stack

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ High-Level Applications │

│ (Python, JavaScript, Java, Go, Rust, etc.) │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Language Runtimes │

│ (CPython, V8, JVM, Node.js - written in C/C++) │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ System Libraries │

│ (glibc, musl, Windows CRT - written in C) │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Operating System Kernel │

│ (Linux, Windows NT, macOS XNU - written in C) │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Hardware Abstraction │

│ (Device drivers, firmware - written in C/Assembly) │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Bare Metal / Hardware │

│ (CPU, Memory, Peripherals) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

C23 (ISO/IEC 9899:2024)

The latest C standard formalizes modern capabilities while preserving compatibility.

- Standard publication: ISO/IEC 9899:2024 (ISO catalog)

- Practical feature reference: cppreference C23 overview

Notable updates include modern keywords and library improvements, plus safer primitives (for example explicit secure memory operations). The practical lesson is not “new syntax first”; it is learning how standards evolve while old code and ABIs remain in production.

Understanding C means understanding how computers actually work, and that knowledge transfers to every language and runtime you use later.

Theory Primer

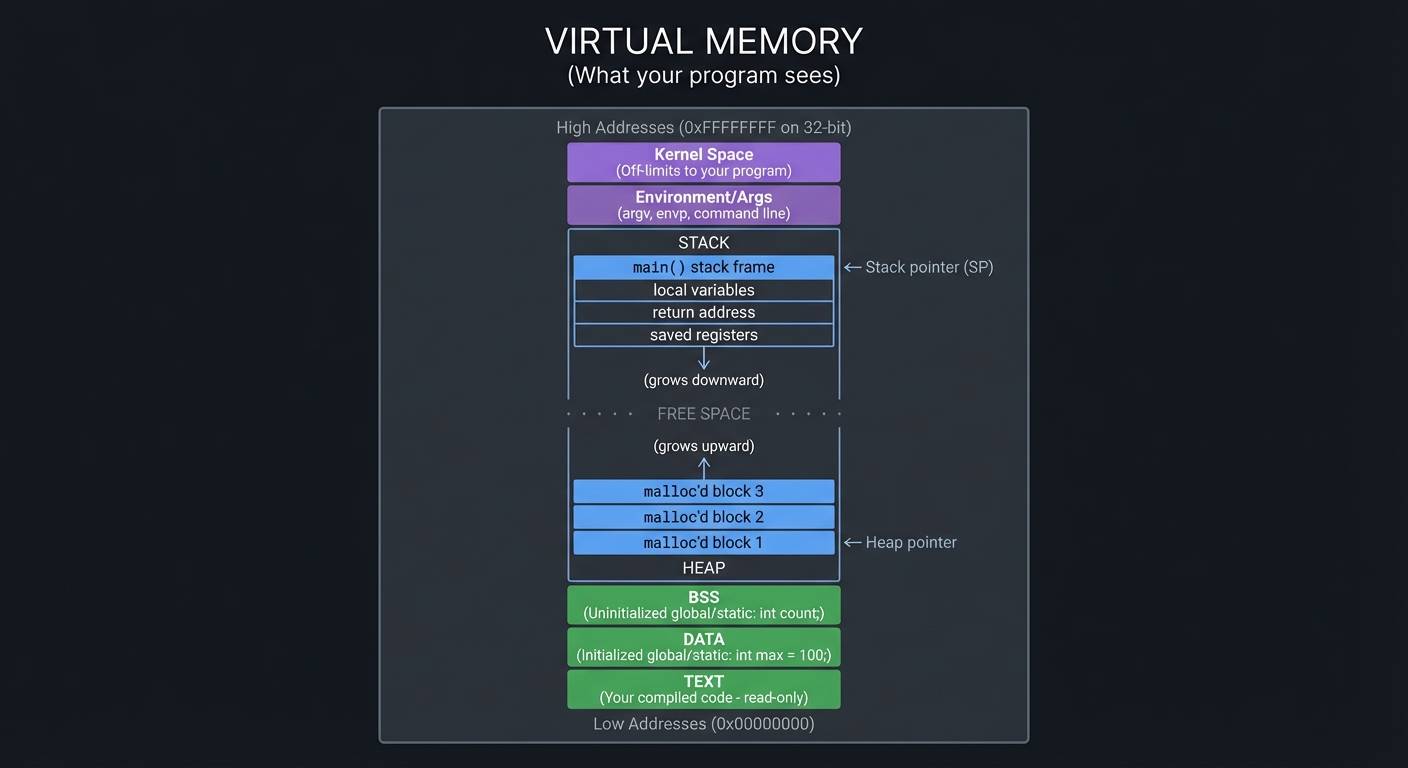

The Memory Model: What You’re Really Working With

Everything in C comes down to memory. Every variable, every function, every data structure is just bytes at addresses. Understanding this is the key to mastering C.

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ VIRTUAL MEMORY │

│ (What your program sees) │

├────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ High Addresses (0xFFFFFFFF on 32-bit) │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Kernel Space │ │

│ │ (Off-limits to your program) │ │

│ ├──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ Environment/Args │ │

│ │ (argv, envp, command line) │ │

│ ├──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ STACK │ │

│ │ ┌─────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ main() stack frame │ ← Stack pointer (SP) │ │

│ │ ├─────────────────────┤ │ │

│ │ │ local variables │ │ │

│ │ │ return address │ │ │

│ │ │ saved registers │ │ │

│ │ └─────────────────────┘ │ │

│ │ ↓ │ │

│ │ (grows downward) │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ · · · · · · FREE SPACE · · · · · · │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ (grows upward) │ │

│ │ ↑ │ │

│ │ ┌─────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ malloc'd block 3 │ │ │

│ │ ├─────────────────────┤ │ │

│ │ │ malloc'd block 2 │ │ │

│ │ ├─────────────────────┤ │ │

│ │ │ malloc'd block 1 │ ← Heap pointer │ │

│ │ └─────────────────────┘ │ │

│ │ HEAP │ │

│ │ │ │

│ ├──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ BSS │ │

│ │ (Uninitialized global/static: int count;) │ │

│ ├──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ DATA │ │

│ │ (Initialized global/static: int max = 100;) │ │

│ ├──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ TEXT │ │

│ │ (Your compiled code - read-only) │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ Low Addresses (0x00000000) │

│ │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

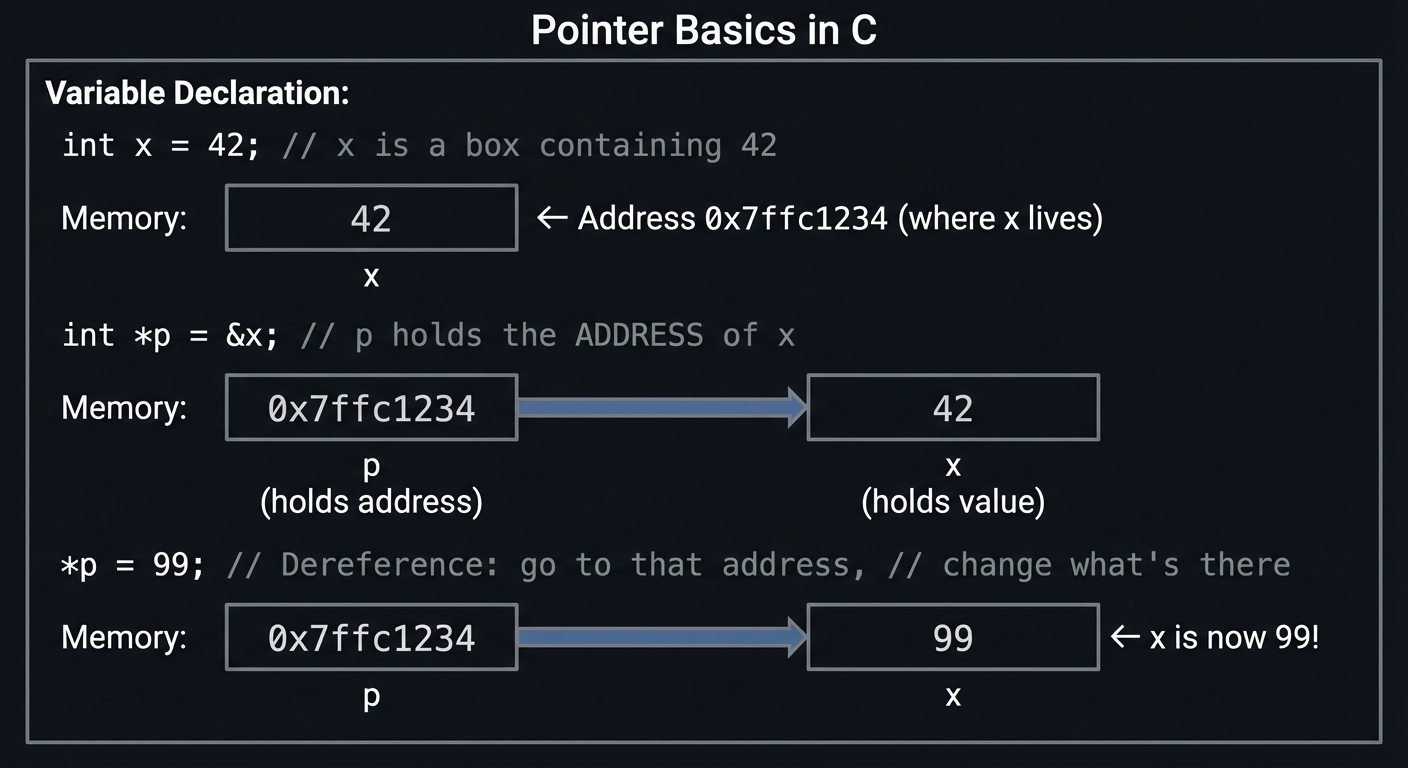

Pointers: The Heart of C

A pointer is just a variable that holds a memory address. That’s it. But this simple concept unlocks everything:

Variable Declaration:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ │

│ int x = 42; // x is a box containing 42 │

│ │

│ Memory: │

│ ┌──────────┐ │

│ │ 42 │ ← Address 0x7ffc1234 (where x lives) │

│ └──────────┘ │

│ x │

│ │

│ int *p = &x; // p holds the ADDRESS of x │

│ │

│ Memory: │

│ ┌──────────────┐ ┌──────────┐ │

│ │ 0x7ffc1234 │ ───► │ 42 │ │

│ └──────────────┘ └──────────┘ │

│ p x │

│ (holds address) (holds value) │

│ │

│ *p = 99; // Dereference: go to that address, │

│ // change what's there │

│ │

│ ┌──────────────┐ ┌──────────┐ │

│ │ 0x7ffc1234 │ ───► │ 99 │ ← x is now 99! │

│ └──────────────┘ └──────────┘ │

│ p x │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

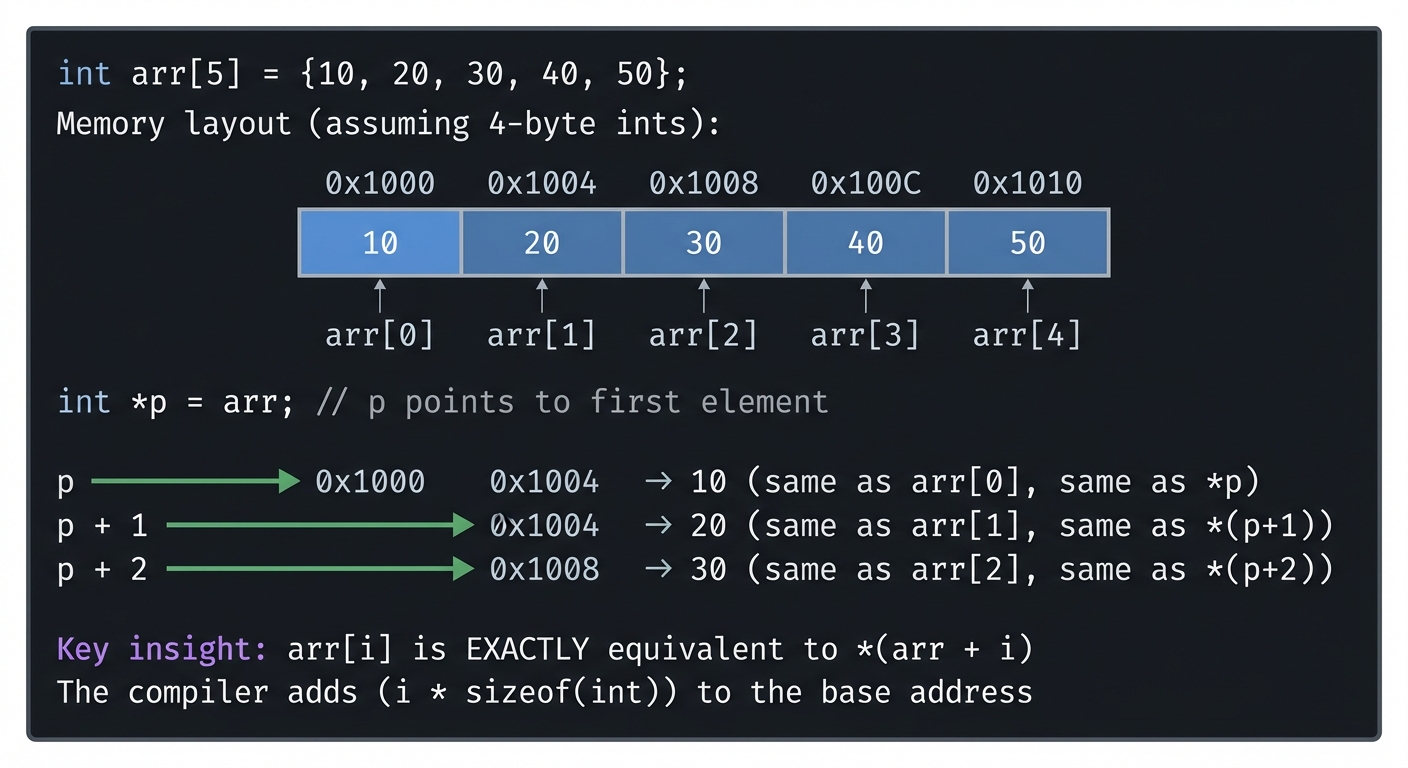

Arrays and Pointer Arithmetic

In C, arrays and pointers are intimately connected:

Array in Memory:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ │

│ int arr[5] = {10, 20, 30, 40, 50}; │

│ │

│ Memory layout (assuming 4-byte ints): │

│ │

│ Address: 0x1000 0x1004 0x1008 0x100C 0x1010 │

│ ┌───────┬───────┬───────┬───────┬───────┐ │

│ Value: │ 10 │ 20 │ 30 │ 40 │ 50 │ │

│ └───────┴───────┴───────┴───────┴───────┘ │

│ Index: arr[0] arr[1] arr[2] arr[3] arr[4] │

│ │

│ int *p = arr; // p points to first element │

│ │

│ p → 10 (same as arr[0], same as *p) │

│ p + 1 → 20 (same as arr[1], same as *(p+1)) │

│ p + 2 → 30 (same as arr[2], same as *(p+2)) │

│ │

│ Key insight: arr[i] is EXACTLY equivalent to *(arr + i) │

│ The compiler adds (i * sizeof(int)) to the base address │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

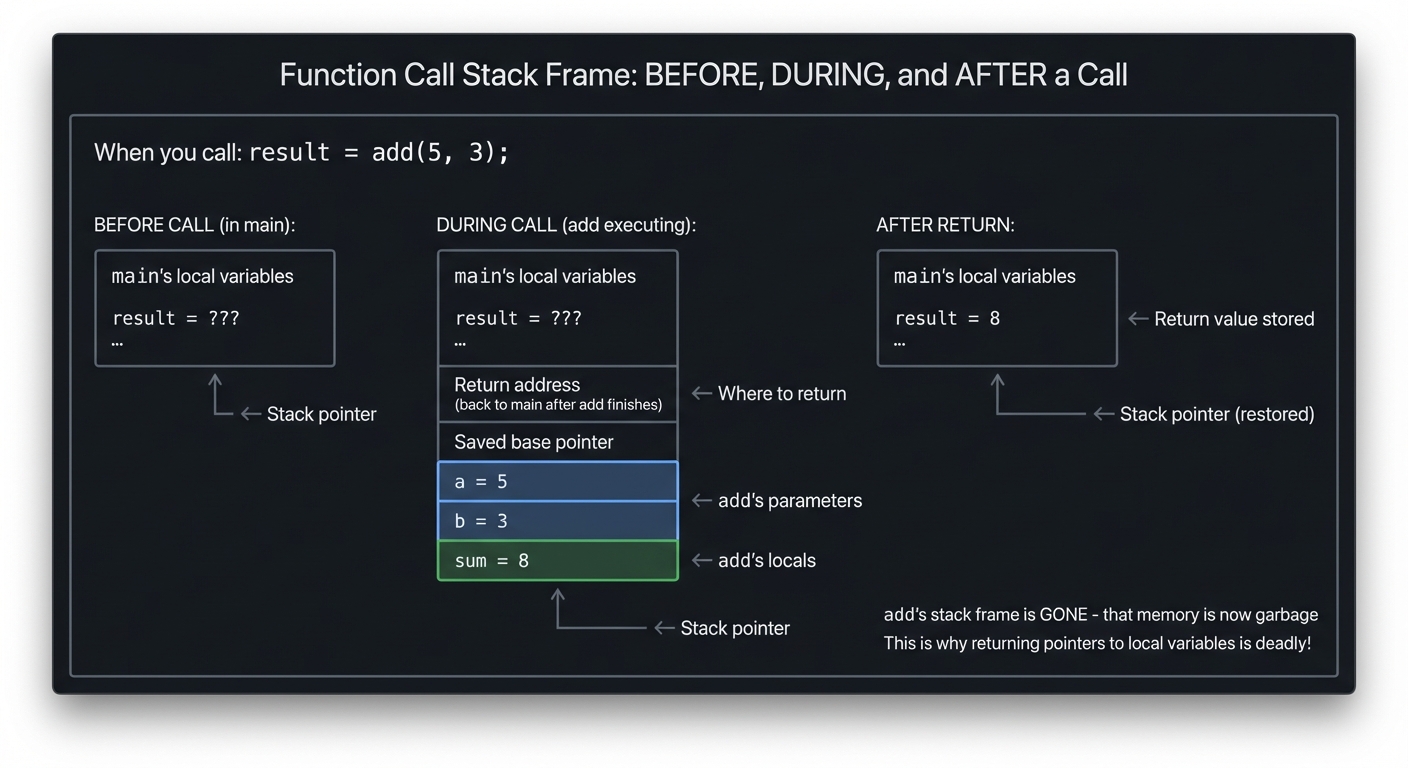

The Stack Frame: Function Calls Demystified

When you call: result = add(5, 3);

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ │

│ BEFORE CALL (in main): │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ main's local variables │ │

│ │ result = ??? │ │

│ │ ... │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────┘ ← Stack pointer │

│ │

│ DURING CALL (add executing): │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ main's local variables │ │

│ │ result = ??? │ │

│ │ ... │ │

│ ├─────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ Return address (back to │ ← Where to return │

│ │ main after add finishes) │ │

│ ├─────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ Saved base pointer │ │

│ ├─────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ a = 5 │ ← add's parameters │

│ │ b = 3 │ │

│ ├─────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ sum = 8 │ ← add's locals │

│ └─────────────────────────────┘ ← Stack pointer │

│ │

│ AFTER RETURN: │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ main's local variables │ │

│ │ result = 8 │ ← Return value stored │

│ │ ... │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────┘ ← Stack pointer (restored) │

│ │

│ add's stack frame is GONE - that memory is now garbage │

│ This is why returning pointers to local variables is deadly! │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

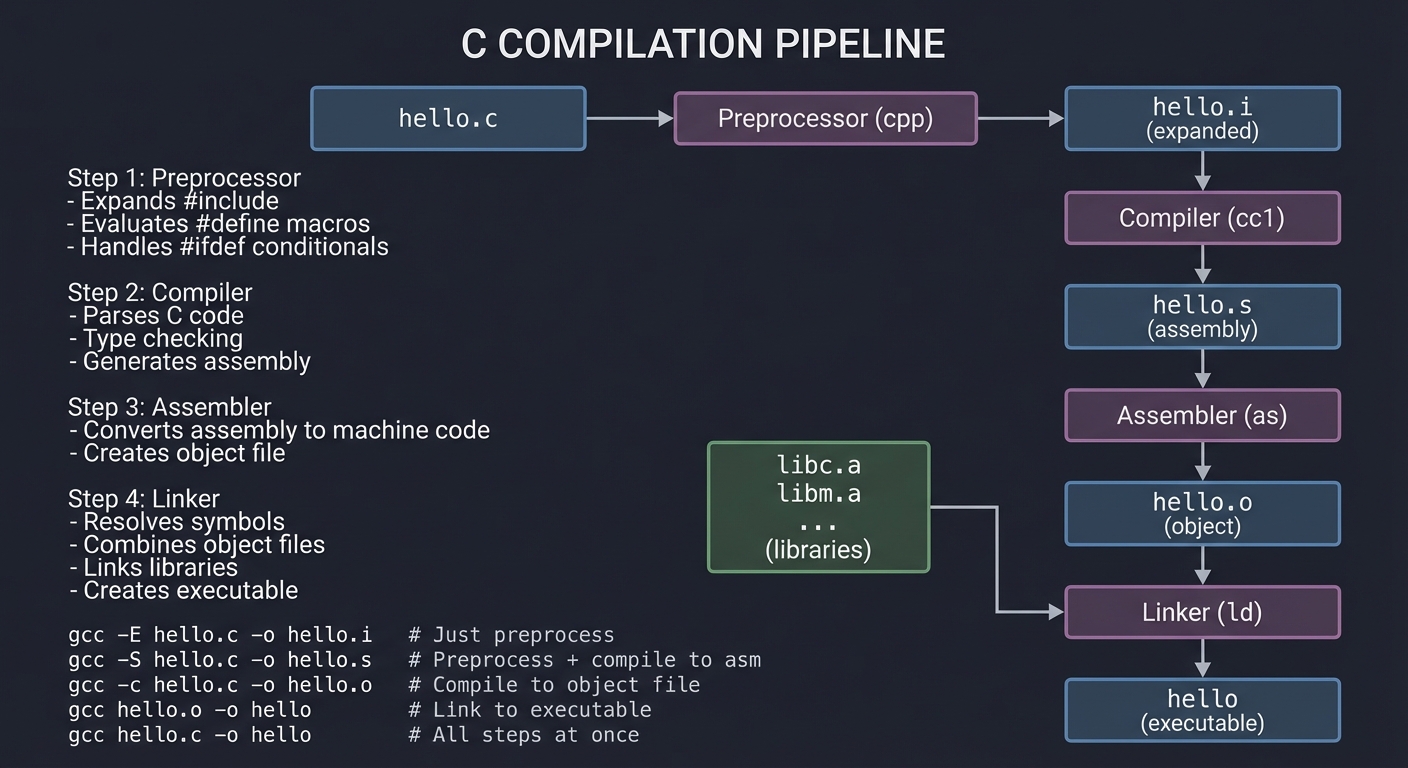

The Compilation Pipeline

Understanding how C code becomes an executable is crucial for debugging and optimization:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ C COMPILATION PIPELINE │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ ┌─────────┐ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────┐ │

│ │ hello.c │ ──► │ Preprocessor │ ──► │ hello.i │ │

│ └─────────┘ │ (cpp) │ │ (expanded) │ │

│ └─────────────┘ └──────┬──────┘ │

│ │ │

│ Step 1: Preprocessor ▼ │

│ - Expands #include ┌─────────────┐ │

│ - Evaluates #define macros │ Compiler │ │

│ - Handles #ifdef conditionals │ (cc1) │ │

│ └──────┬──────┘ │

│ │ │

│ Step 2: Compiler ▼ │

│ - Parses C code ┌─────────────┐ │

│ - Type checking │ hello.s │ │

│ - Generates assembly │ (assembly) │ │

│ └──────┬──────┘ │

│ │ │

│ Step 3: Assembler ▼ │

│ - Converts assembly to ┌─────────────┐ │

│ machine code │ Assembler │ │

│ - Creates object file │ (as) │ │

│ └──────┬──────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌─────────────┐ │

│ │ hello.o │ │

│ │ (object) │ │

│ ┌─────────┐ └──────┬──────┘ │

│ │ libc.a │ ─────────────────────────────►│ │

│ │ libm.a │ (libraries) │ │

│ │ ... │ ▼ │

│ └─────────┘ ┌─────────────┐ │

│ │ Linker │ │

│ Step 4: Linker │ (ld) │ │

│ - Resolves symbols └──────┬──────┘ │

│ - Combines object files │ │

│ - Links libraries ▼ │

│ - Creates executable ┌─────────────┐ │

│ │ hello │ │

│ │ (executable)│ │

│ └─────────────┘ │

│ │

│ gcc -E hello.c -o hello.i # Just preprocess │

│ gcc -S hello.c -o hello.s # Preprocess + compile to asm │

│ gcc -c hello.c -o hello.o # Compile to object file │

│ gcc hello.o -o hello # Link to executable │

│ gcc hello.c -o hello # All steps at once │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

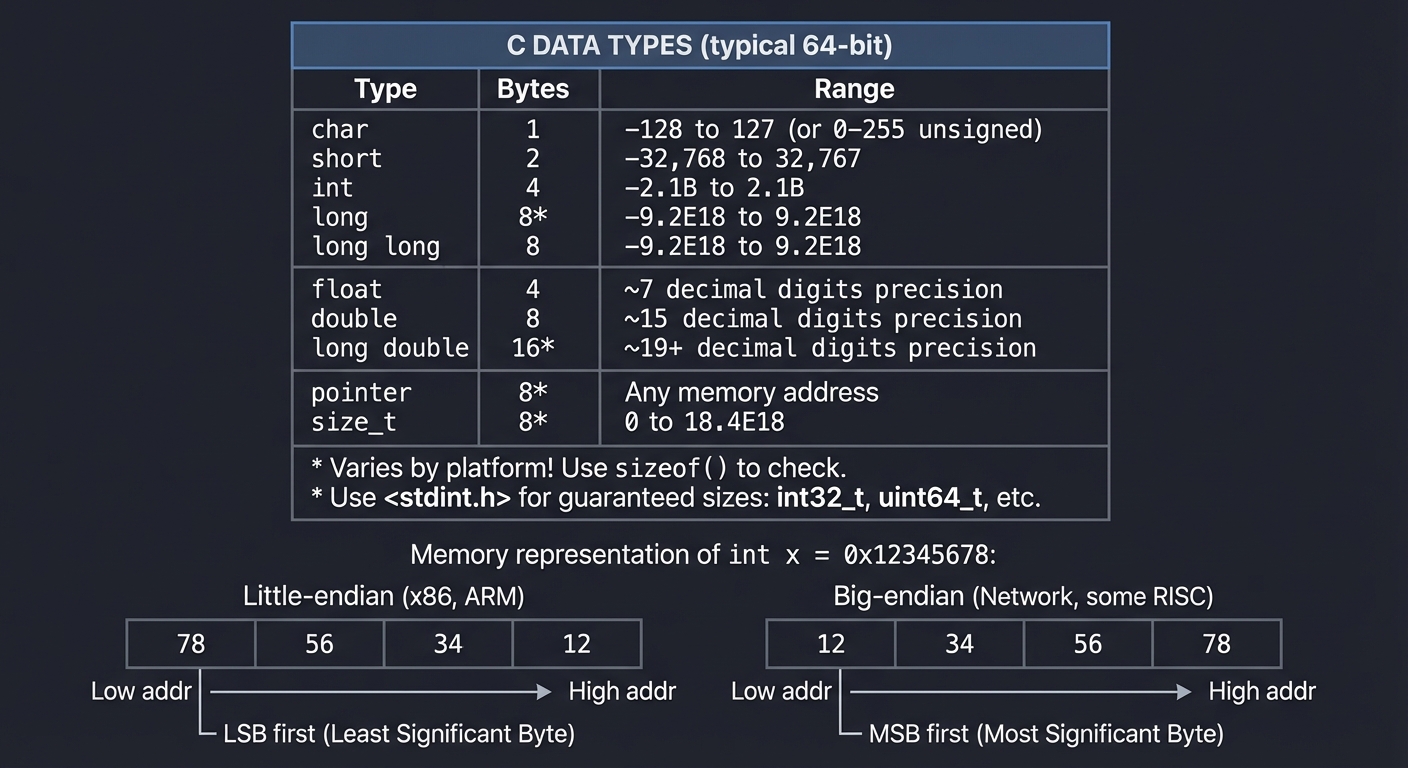

Data Types and Their Sizes

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ C DATA TYPES (typical 64-bit) │

├───────────────┬──────────┬──────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Type │ Bytes │ Range │

├───────────────┼──────────┼──────────────────────────────────────┤

│ char │ 1 │ -128 to 127 (or 0-255 unsigned) │

│ short │ 2 │ -32,768 to 32,767 │

│ int │ 4 │ -2.1B to 2.1B │

│ long │ 8* │ -9.2E18 to 9.2E18 │

│ long long │ 8 │ -9.2E18 to 9.2E18 │

├───────────────┼──────────┼──────────────────────────────────────┤

│ float │ 4 │ ~7 decimal digits precision │

│ double │ 8 │ ~15 decimal digits precision │

│ long double │ 16* │ ~19+ decimal digits precision │

├───────────────┼──────────┼──────────────────────────────────────┤

│ pointer │ 8* │ Any memory address │

│ size_t │ 8* │ 0 to 18.4E18 │

├───────────────┴──────────┴──────────────────────────────────────┤

│ * Varies by platform! Use sizeof() to check. │

│ * Use <stdint.h> for guaranteed sizes: int32_t, uint64_t, etc. │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Memory representation of int x = 0x12345678:

Little-endian (x86, ARM): Big-endian (Network, some RISC):

┌────┬────┬────┬────┐ ┌────┬────┬────┬────┐

│ 78 │ 56 │ 34 │ 12 │ │ 12 │ 34 │ 56 │ 78 │

└────┴────┴────┴────┘ └────┴────┴────┴────┘

Low High Low High

addr addr addr addr

LSB first (Least MSB first (Most

Significant Byte) Significant Byte)

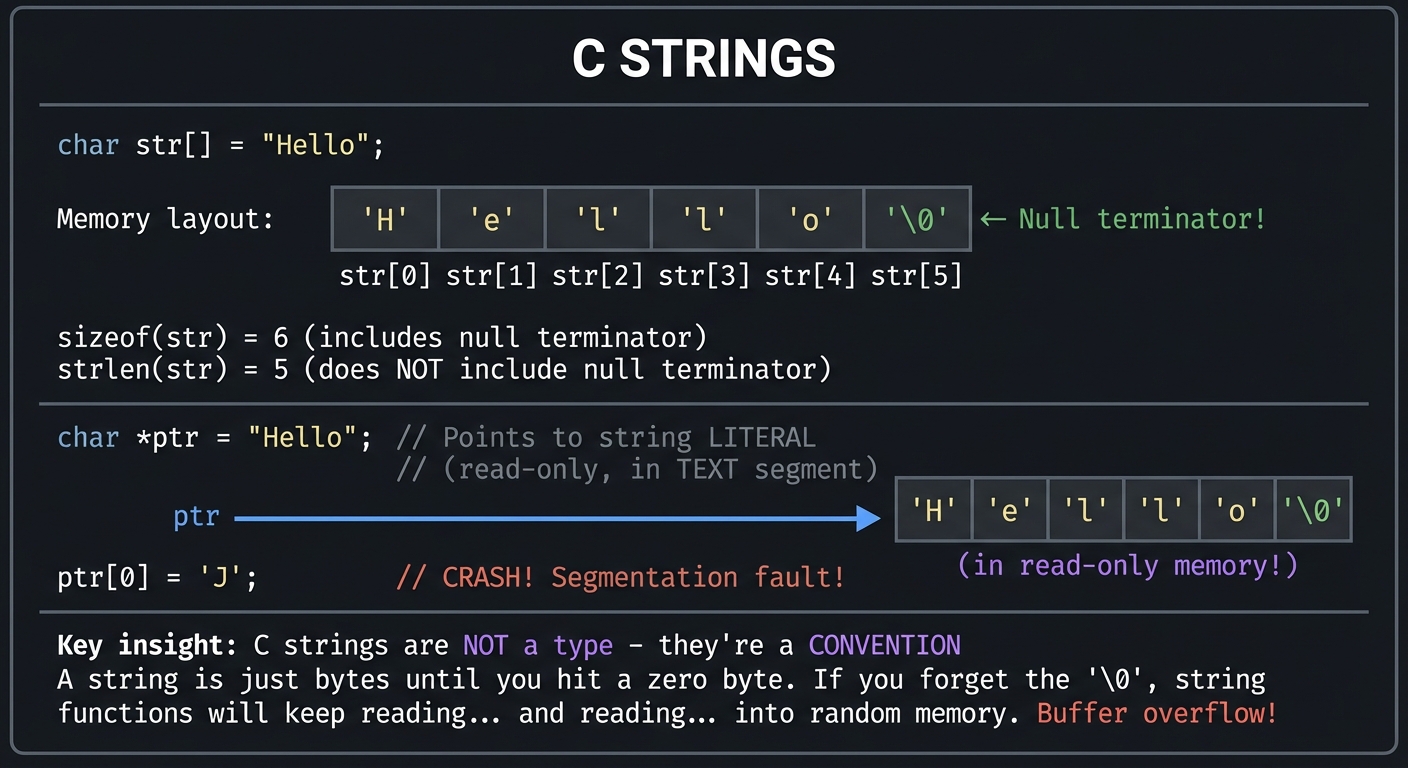

Strings in C: Arrays of Characters

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ C STRINGS │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ char str[] = "Hello"; │

│ │

│ Memory layout: │

│ ┌─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┐ │

│ │ 'H' │ 'e' │ 'l' │ 'l' │ 'o' │ '\0'│ ← Null terminator! │

│ └─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┘ │

│ str[0] str[1] str[2] str[3] str[4] str[5] │

│ │

│ sizeof(str) = 6 (includes null terminator) │

│ strlen(str) = 5 (does NOT include null terminator) │

│ │

│ ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ char *ptr = "Hello"; // Points to string LITERAL │

│ // (read-only, in TEXT segment) │

│ │

│ ptr ──────► ┌─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┐ │

│ │ 'H' │ 'e' │ 'l' │ 'l' │ 'o' │ '\0'│ │

│ └─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┘ │

│ (in read-only memory!) │

│ │

│ ptr[0] = 'J'; // CRASH! Segmentation fault! │

│ │

│ ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ Key insight: C strings are NOT a type - they're a CONVENTION │

│ A string is just bytes until you hit a zero byte. │

│ If you forget the '\0', string functions will keep reading... │

│ and reading... into random memory. Buffer overflow! │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

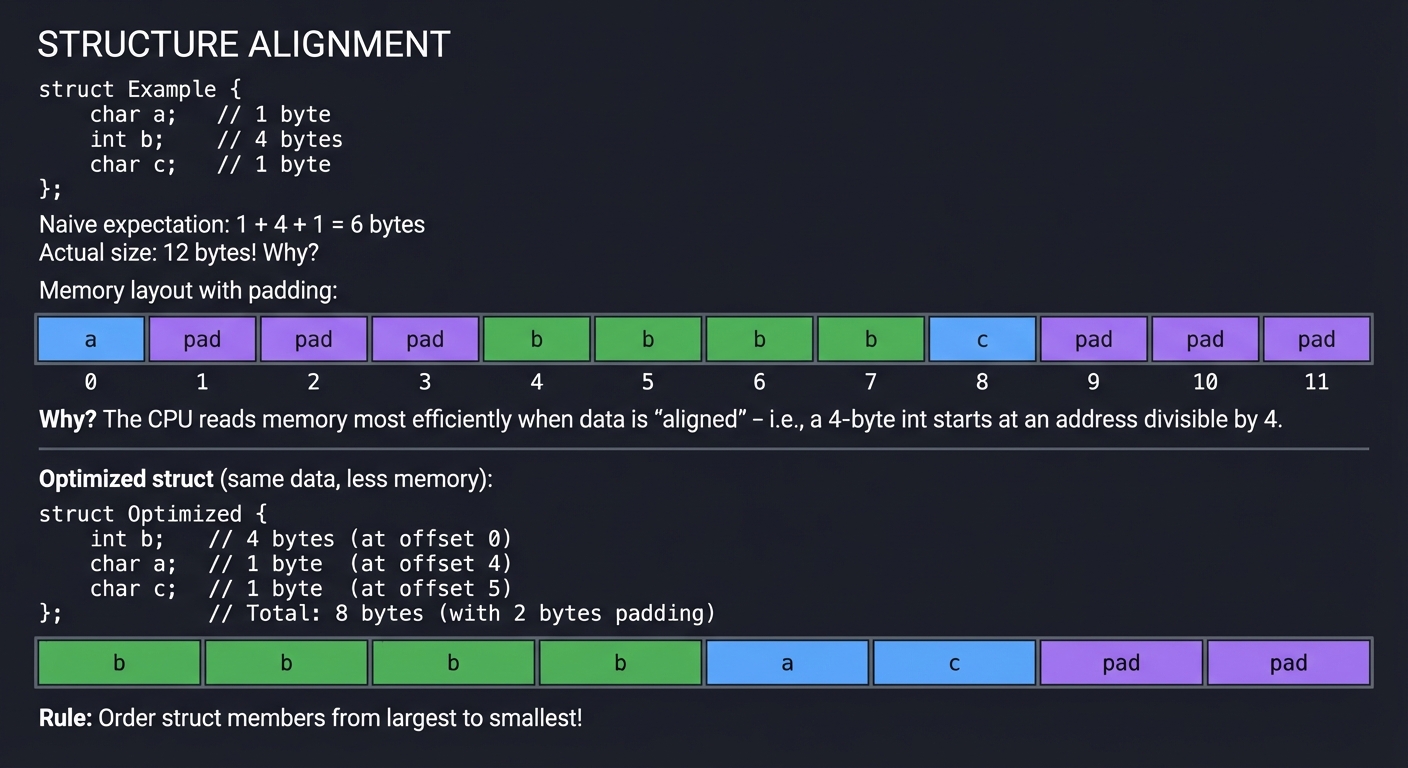

Structures and Memory Alignment

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ STRUCTURE ALIGNMENT │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ struct Example { │

│ char a; // 1 byte │

│ int b; // 4 bytes │

│ char c; // 1 byte │

│ }; │

│ │

│ Naive expectation: 1 + 4 + 1 = 6 bytes │

│ Actual size: 12 bytes! Why? │

│ │

│ Memory layout with padding: │

│ ┌────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬────┐ │

│ │ a │pad │pad │pad │ b │ b │ b │ b │ c │pad │pad │pad │ │

│ └────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴────┘ │

│ 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 │

│ │

│ Why? The CPU reads memory most efficiently when data is │

│ "aligned" - i.e., a 4-byte int starts at an address │

│ divisible by 4. │

│ │

│ ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ Optimized struct (same data, less memory): │

│ │

│ struct Optimized { │

│ int b; // 4 bytes (at offset 0) │

│ char a; // 1 byte (at offset 4) │

│ char c; // 1 byte (at offset 5) │

│ }; // Total: 8 bytes (with 2 bytes padding) │

│ │

│ ┌────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬────┐ │

│ │ b │ b │ b │ b │ a │ c │pad │pad │ │

│ └────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴────┘ │

│ │

│ Rule: Order struct members from largest to smallest! │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

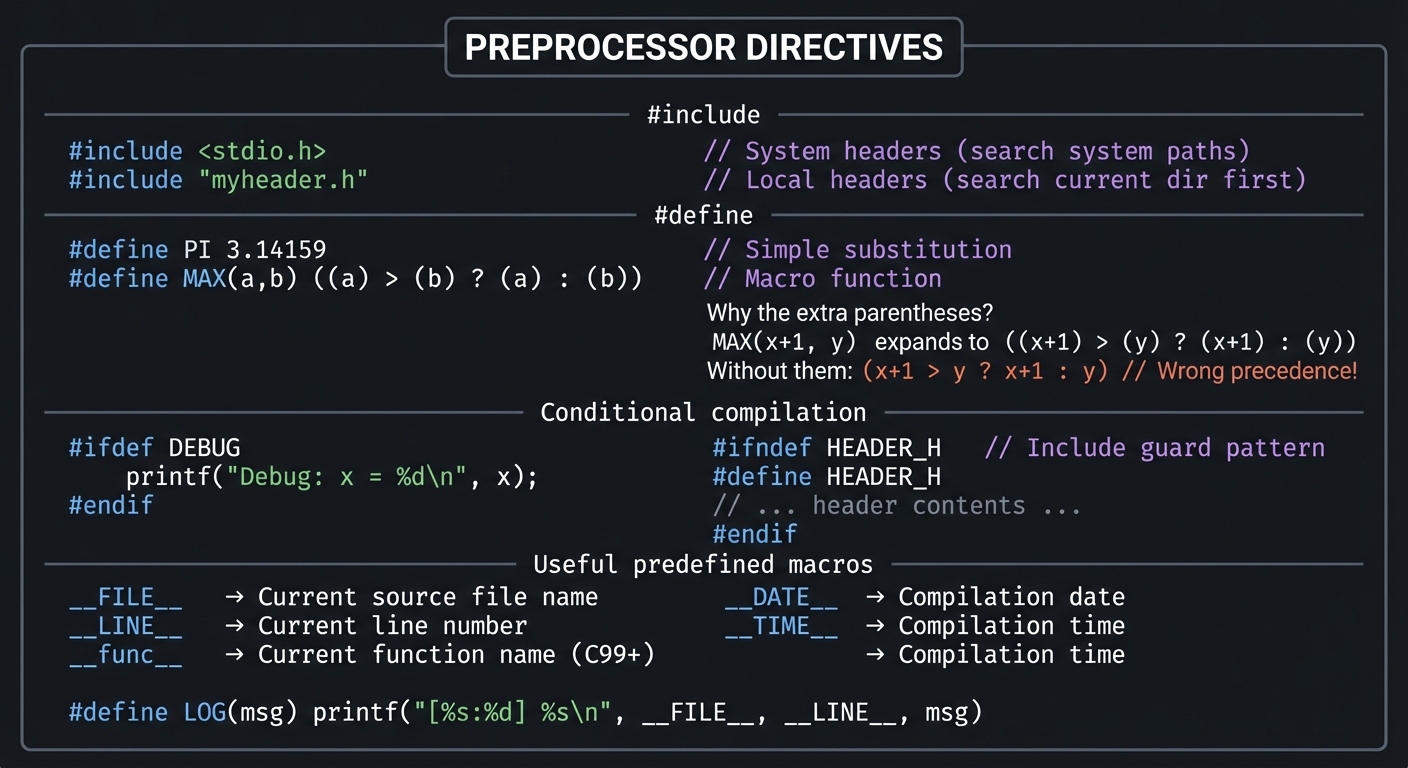

The Preprocessor: Metaprogramming in C

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ PREPROCESSOR DIRECTIVES │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ #include <stdio.h> // System headers (search system │

│ #include "myheader.h" // paths) Local headers (search │

│ // current dir first) │

│ │

│ ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ #define PI 3.14159 // Simple substitution │

│ #define MAX(a,b) ((a) > (b) ? (a) : (b)) // Macro function │

│ │

│ Why the extra parentheses? │

│ MAX(x+1, y) expands to ((x+1) > (y) ? (x+1) : (y)) │

│ Without them: (x+1 > y ? x+1 : y) // Wrong precedence! │

│ │

│ ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ Conditional compilation: │

│ │

│ #ifdef DEBUG │

│ printf("Debug: x = %d\n", x); │

│ #endif │

│ │

│ #ifndef HEADER_H // Include guard pattern │

│ #define HEADER_H │

│ // ... header contents ... │

│ #endif │

│ │

│ ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ Useful predefined macros: │

│ __FILE__ → Current source file name │

│ __LINE__ → Current line number │

│ __func__ → Current function name (C99+) │

│ __DATE__ → Compilation date │

│ __TIME__ → Compilation time │

│ │

│ #define LOG(msg) printf("[%s:%d] %s\n", __FILE__, __LINE__, msg)│

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Professional C Patterns

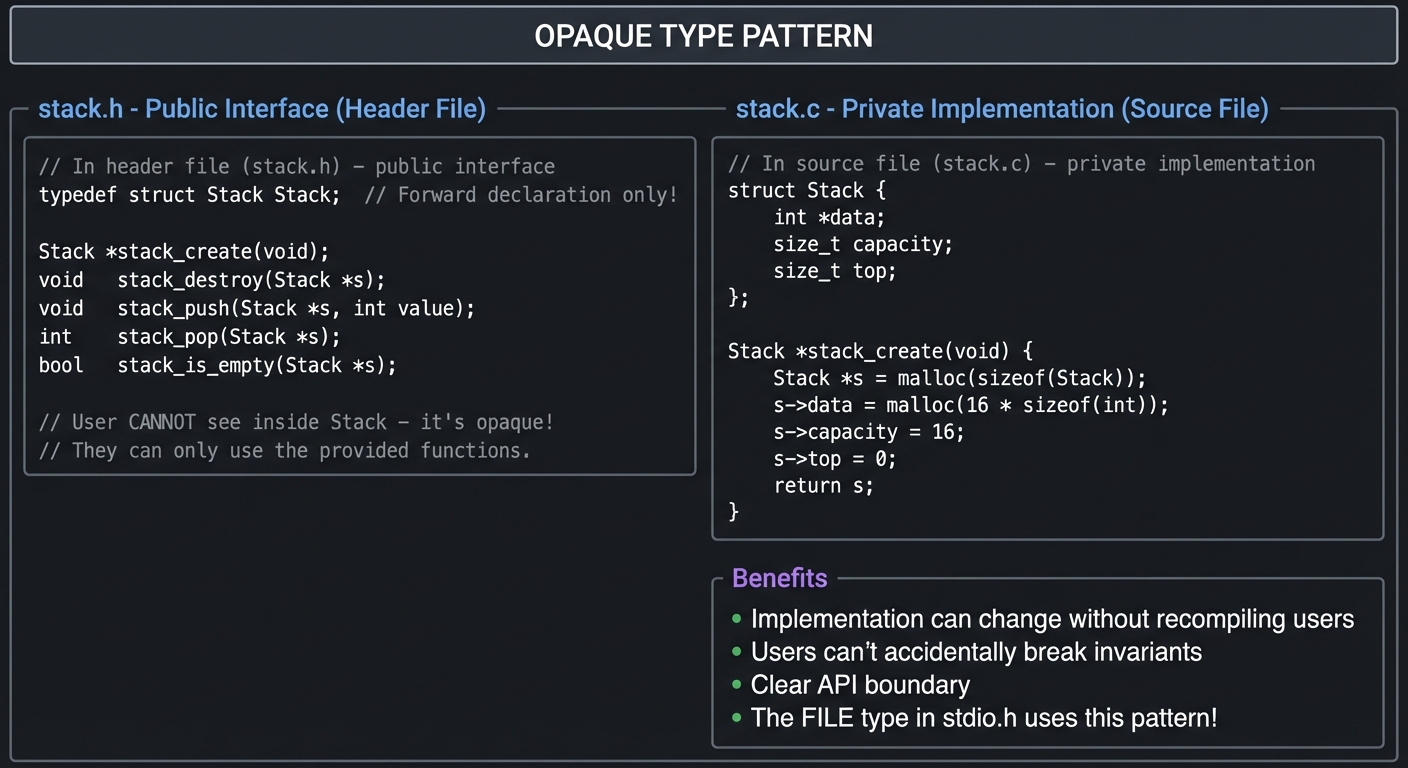

Pattern 1: Opaque Types (Information Hiding)

The opaque pointer pattern is one of the most important patterns in C for creating maintainable, modular code:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ OPAQUE TYPE PATTERN │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ // In header file (stack.h) - public interface │

│ typedef struct Stack Stack; // Forward declaration only! │

│ │

│ Stack *stack_create(void); │

│ void stack_destroy(Stack *s); │

│ void stack_push(Stack *s, int value); │

│ int stack_pop(Stack *s); │

│ bool stack_is_empty(Stack *s); │

│ │

│ // User CANNOT see inside Stack - it's opaque! │

│ // They can only use the provided functions. │

│ │

│ ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ // In source file (stack.c) - private implementation │

│ struct Stack { │

│ int *data; │

│ size_t capacity; │

│ size_t top; │

│ }; │

│ │

│ Stack *stack_create(void) { │

│ Stack *s = malloc(sizeof(Stack)); │

│ s->data = malloc(16 * sizeof(int)); │

│ s->capacity = 16; │

│ s->top = 0; │

│ return s; │

│ } │

│ │

│ ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ Benefits: │

│ • Implementation can change without recompiling users │

│ • Users can't accidentally break invariants │

│ • Clear API boundary │

│ • The FILE type in stdio.h uses this pattern! │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

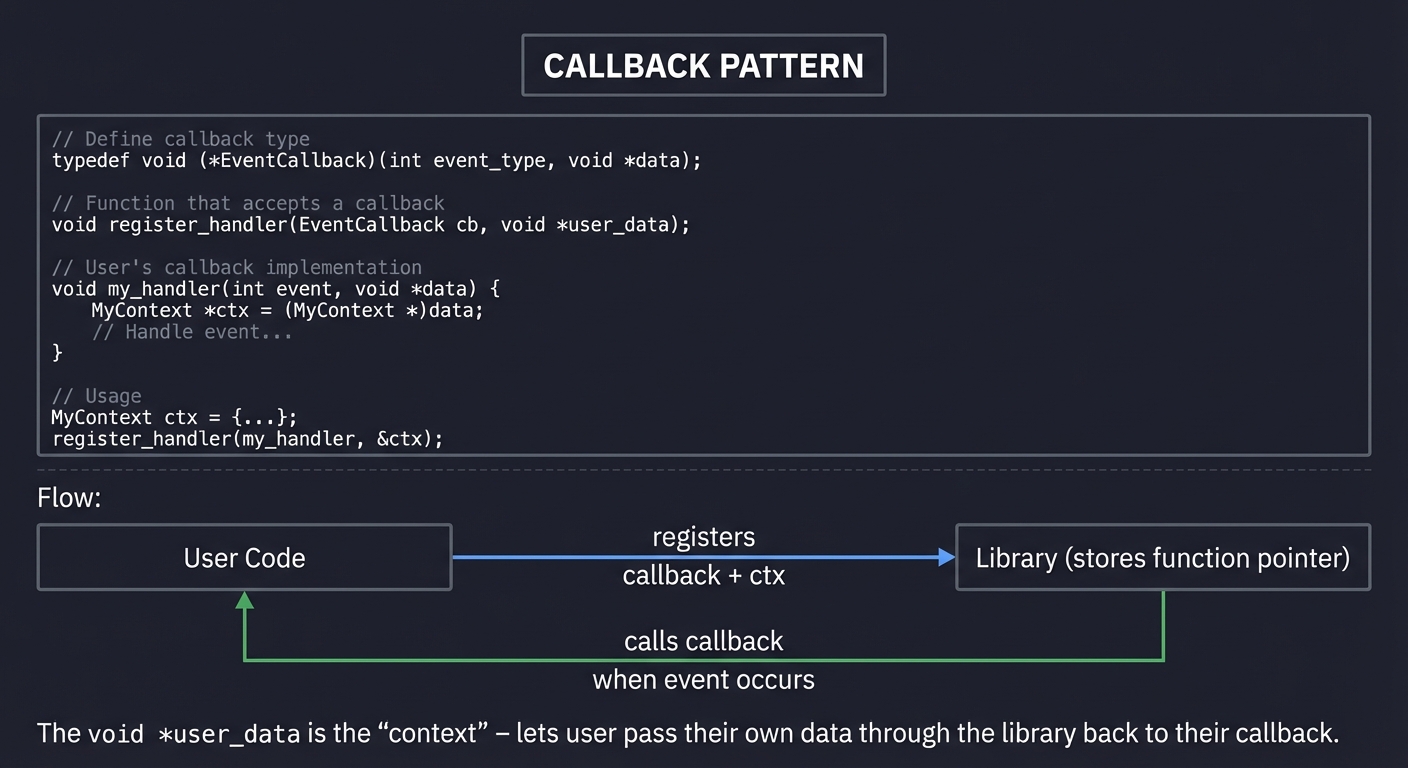

Pattern 2: Callback Functions

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ CALLBACK PATTERN │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ // Define callback type │

│ typedef void (*EventCallback)(int event_type, void *data); │

│ │

│ // Function that accepts a callback │

│ void register_handler(EventCallback cb, void *user_data); │

│ │

│ // User's callback implementation │

│ void my_handler(int event, void *data) { │

│ MyContext *ctx = (MyContext *)data; │

│ // Handle event... │

│ } │

│ │

│ // Usage │

│ MyContext ctx = {...}; │

│ register_handler(my_handler, &ctx); │

│ │

│ ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ Flow: │

│ │

│ ┌──────────┐ registers ┌──────────────┐ │

│ │ User │ ─────────────────► │ Library │ │

│ │ Code │ callback + ctx │ (stores │ │

│ └──────────┘ │ function │ │

│ ▲ │ pointer) │ │

│ │ └──────┬───────┘ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ calls callback │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ when event occurs │

│ │

│ The void *user_data is the "context" - lets user pass │

│ their own data through the library back to their callback. │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

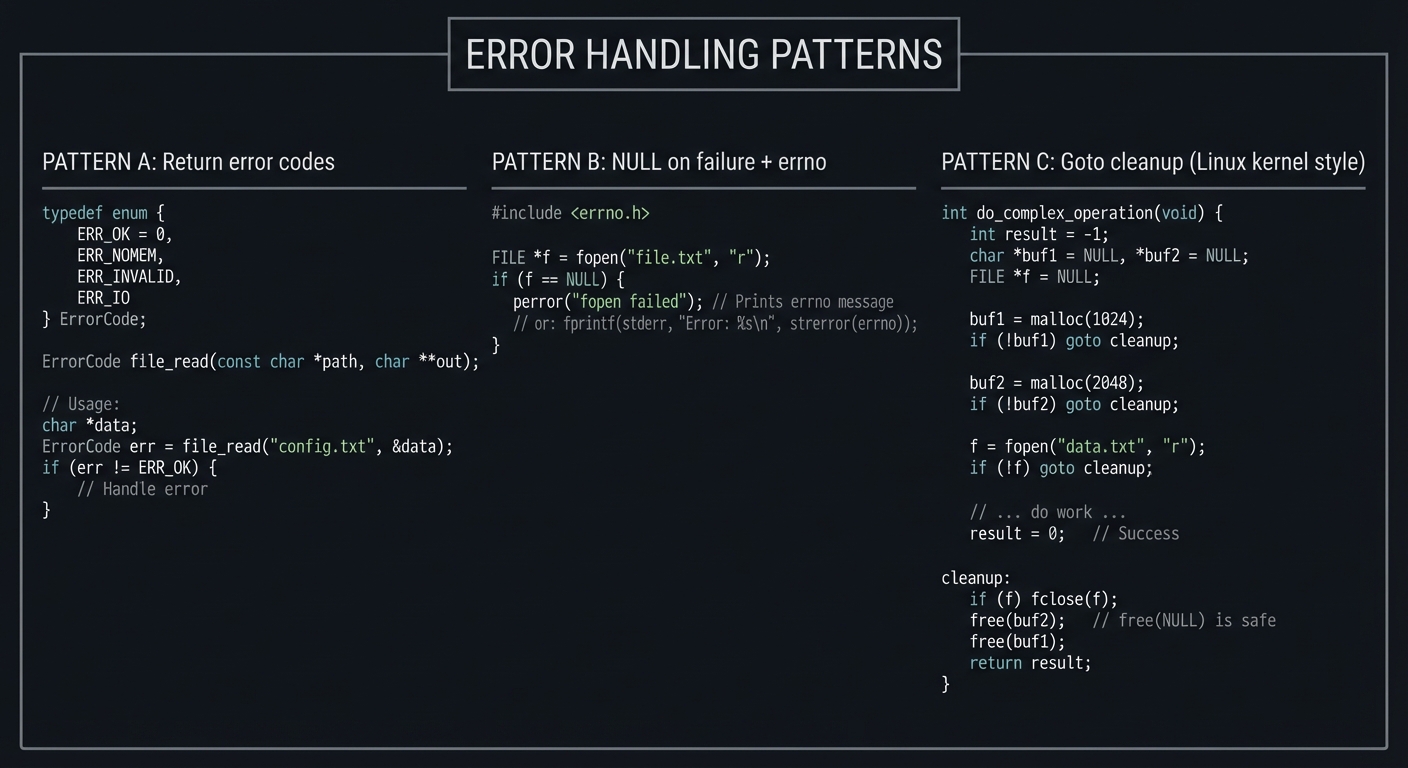

Pattern 3: Error Handling

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ ERROR HANDLING PATTERNS │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ PATTERN A: Return error codes │

│ ───────────────────────────────── │

│ typedef enum { │

│ ERR_OK = 0, │

│ ERR_NOMEM, │

│ ERR_INVALID, │

│ ERR_IO │

│ } ErrorCode; │

│ │

│ ErrorCode file_read(const char *path, char **out); │

│ │

│ // Usage: │

│ char *data; │

│ ErrorCode err = file_read("config.txt", &data); │

│ if (err != ERR_OK) { │

│ // Handle error │

│ } │

│ │

│ ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ PATTERN B: NULL on failure + errno │

│ ───────────────────────────────── │

│ #include <errno.h> │

│ │

│ FILE *f = fopen("file.txt", "r"); │

│ if (f == NULL) { │

│ perror("fopen failed"); // Prints errno message │

│ // or: fprintf(stderr, "Error: %s\n", strerror(errno)); │

│ } │

│ │

│ ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ PATTERN C: Goto cleanup (Linux kernel style) │

│ ───────────────────────────────── │

│ int do_complex_operation(void) { │

│ int result = -1; │

│ char *buf1 = NULL, *buf2 = NULL; │

│ FILE *f = NULL; │

│ │

│ buf1 = malloc(1024); │

│ if (!buf1) goto cleanup; │

│ │

│ buf2 = malloc(2048); │

│ if (!buf2) goto cleanup; │

│ │

│ f = fopen("data.txt", "r"); │

│ if (!f) goto cleanup; │

│ │

│ // ... do work ... │

│ result = 0; // Success │

│ │

│ cleanup: │

│ if (f) fclose(f); │

│ free(buf2); // free(NULL) is safe │

│ free(buf1); │

│ return result; │

│ } │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Glossary

- ABI (Application Binary Interface): Contract for calling conventions, symbol names, type layout, and linking compatibility between compiled units.

- ASLR: Address Space Layout Randomization; randomizes memory regions per process launch to increase exploit difficulty.

- BSS: Memory segment for zero-initialized or uninitialized globals/statics.

- Heap: Dynamically managed process memory typically allocated via

malloc/free. - Pointer provenance: The validity relationship between a pointer value and the object it is allowed to access.

- Undefined Behavior (UB): Program behavior for which the C standard imposes no requirements.

- Strict aliasing: Optimization rule that assumes different pointer types usually do not alias the same object.

- Translation unit: One source file after preprocessing, compiled independently.

- Linker: Tool that resolves symbols and combines object files into final binaries.

- Memory-mapped I/O: Hardware register access by reading/writing specific memory addresses.

- Data race: Unsynchronized concurrent access where at least one access is a write.

- Invariant: Condition that must remain true for program correctness.

Concept Summary Table

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize |

|---|---|

| Memory Model & Virtual Address Space | C objects are bytes in process virtual memory, partitioned by segment and lifetime. |

| Pointers, Arrays, and Indirection | Pointer arithmetic is type-scaled address math; array syntax is pointer syntax sugar. |

| Call Stack, ABI, and Function Boundaries | Stack frames, calling convention, and object lifetime rules determine correctness. |

| Compilation Pipeline & Toolchain | Preprocess, compile, assemble, link, and load are distinct stages with different failure modes. |

| Data Representation & Layout | Types, alignment, padding, and endianness directly affect portability and performance. |

| Strings and Buffer Safety | C strings are conventions over bytes; safety requires explicit bounds and termination discipline. |

| Preprocessor and Build Abstractions | Macros, includes, and build graphs shape maintainability as much as code does. |

| Defensive Error Handling Patterns | Resource cleanup and explicit error propagation are mandatory in real systems code. |

| Concurrency and Synchronization | Correctness under parallel execution requires ownership rules and synchronization invariants. |

| Systems Interface Literacy | Files, processes, sockets, and hardware interaction are the practical surface area of C in production. |

Deep Dive Reading by Concept

This section maps each concept to specific book chapters for deeper understanding. Read these before or alongside the projects.

Fundamentals and Syntax

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| C syntax and basics | C Programming: A Modern Approach by K.N. King — Ch. 1-5 |

| Data types | C Programming: A Modern Approach by K.N. King — Ch. 7: “Basic Types” |

| Control flow | Effective C, 2nd Ed by Robert Seacord — Ch. 5: “Control Flow” |

| Functions | C Programming: A Modern Approach by K.N. King — Ch. 9-10 |

Pointers and Memory

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Pointer fundamentals | C Programming: A Modern Approach by K.N. King — Ch. 11: “Pointers” |

| Pointers and arrays | C Programming: A Modern Approach by K.N. King — Ch. 12: “Pointers and Arrays” |

| Dynamic memory | Effective C, 2nd Ed by Robert Seacord — Ch. 6: “Dynamically Allocated Memory” |

| Memory errors | Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective by Bryant & O’Hallaron — Ch. 9: “Virtual Memory” |

Data Structures

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Strings | C Programming: A Modern Approach by K.N. King — Ch. 13: “Strings” |

| Structures and unions | C Programming: A Modern Approach by K.N. King — Ch. 16-17 |

| Linked structures | Mastering Algorithms with C by Kyle Loudon — Ch. 5: “Linked Lists” |

| Trees and graphs | Algorithms in C by Robert Sedgewick — Parts 4-5 |

Systems Programming

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| File I/O | The Linux Programming Interface by Michael Kerrisk — Ch. 4-5 |

| Process memory | Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective by Bryant & O’Hallaron — Ch. 9 |

| System calls | Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment by Stevens & Rago — Ch. 1-3 |

| Signals | The Linux Programming Interface by Michael Kerrisk — Ch. 20-22 |

Professional Practices

| Concept | Book & Chapter |

|---|---|

| Secure coding | Effective C, 2nd Ed by Robert Seacord — All chapters |

| Debugging | The Art of Debugging by Matloff & Salzman — Ch. 1-4 |

| Build systems | The GNU Make Book by John Graham-Cumming — Ch. 1-4 |

| Testing | Effective C, 2nd Ed by Robert Seacord — Ch. 11: “Debugging, Testing, and Analysis” |

Essential Reading Order

For maximum comprehension, read in this order:

- Foundation (Weeks 1-2):

- C Programming: A Modern Approach Ch. 1-10 (fundamentals)

- Effective C Ch. 1-5 (modern practices)

- Memory Mastery (Weeks 3-4):

- C Programming: A Modern Approach Ch. 11-13 (pointers, strings)

- Effective C Ch. 6 (dynamic memory)

- CS:APP Ch. 9 (virtual memory concepts)

- Data Structures (Weeks 5-6):

- C Programming: A Modern Approach Ch. 16-17 (structs)

- Mastering Algorithms with C Ch. 5-8 (data structures)

- Systems (Weeks 7-8):

- The Linux Programming Interface Ch. 4-5, 20-22

- Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment Ch. 1-8

Project-to-Concept Map

| Project | Concepts Applied |

|---|---|

| Project 1: Memory Visualizer | Memory model, segments, pointers, ASLR |

| Project 2: String Library | Pointer arithmetic, buffer boundaries, UB |

| Project 3: Dynamic Array | Heap growth strategy, ownership, API design |

| Project 4: Linked Lists | Indirection, lifetime, mutation invariants |

| Project 5: Hash Table | Hashing, collision policy, load factor tradeoffs |

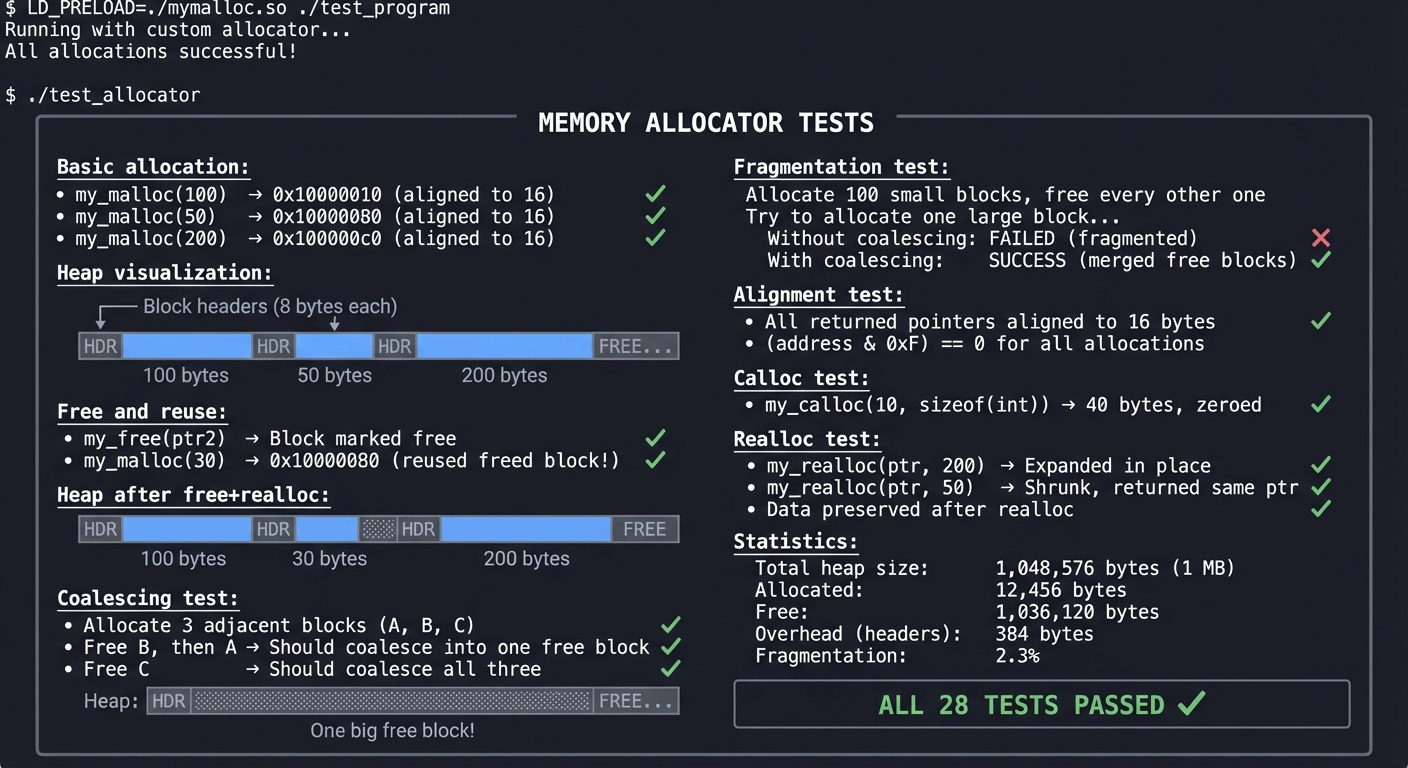

| Project 6: Memory Allocator | Free lists, fragmentation, coalescing invariants |

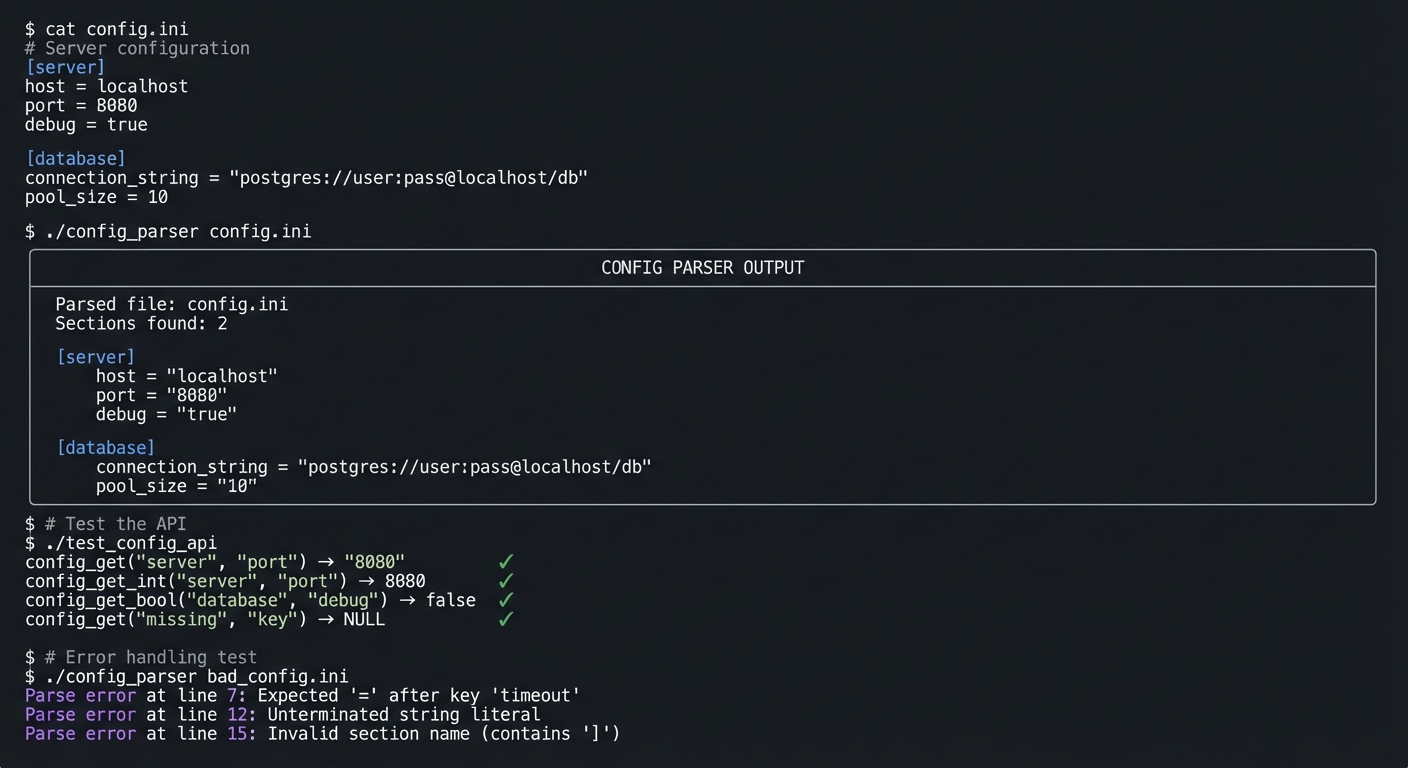

| Project 7: Config Parser | Tokenization, parsing state machines, error recovery |

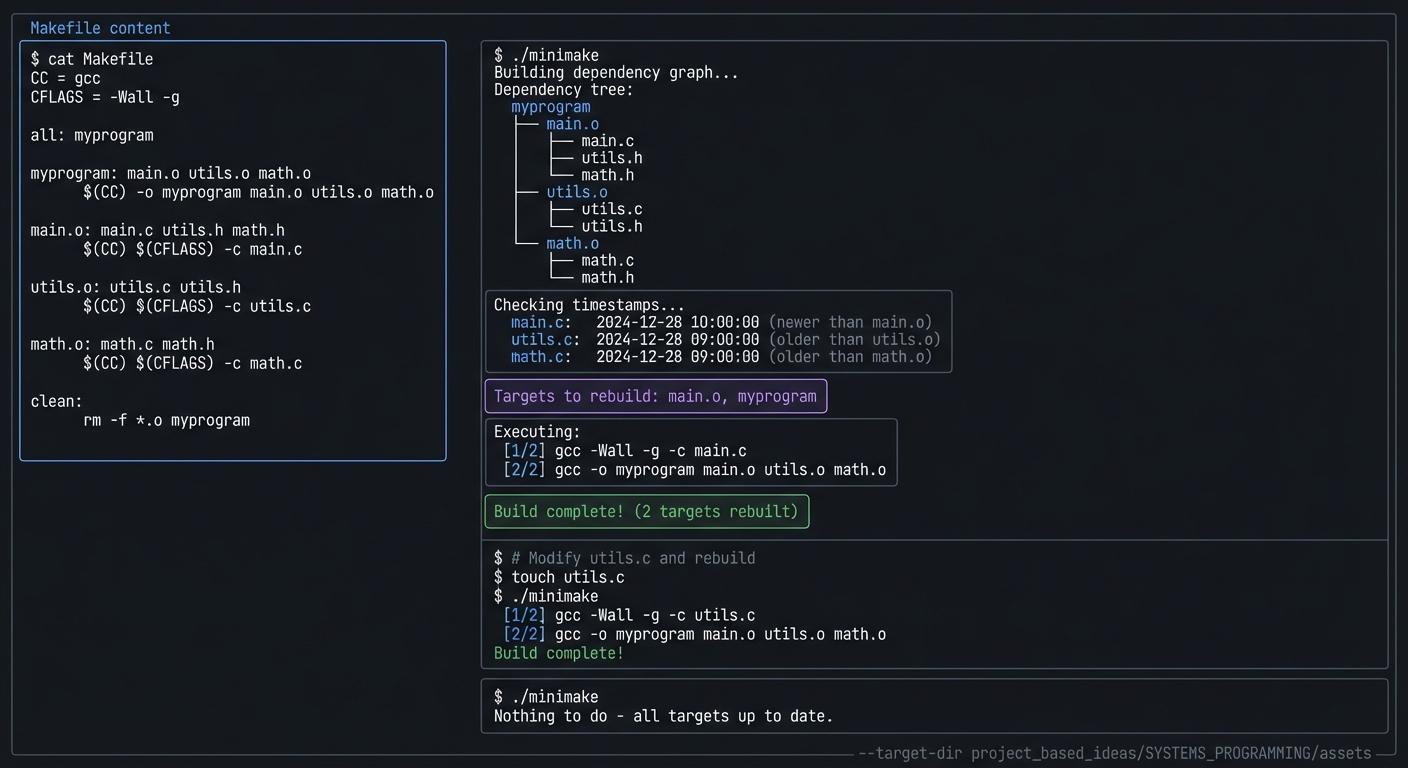

| Project 8: Mini-Make | DAGs, timestamps, incremental rebuild rules |

| Project 9: Unix Shell | fork/exec, pipes, signals, process control |

| Project 10: HTTP Server | Sockets, protocol framing, concurrency model |

| Project 11: Database Engine | Storage layout, indexing, durability tradeoffs |

| Project 12: Debugger | ptrace model, breakpoints, symbol inspection |

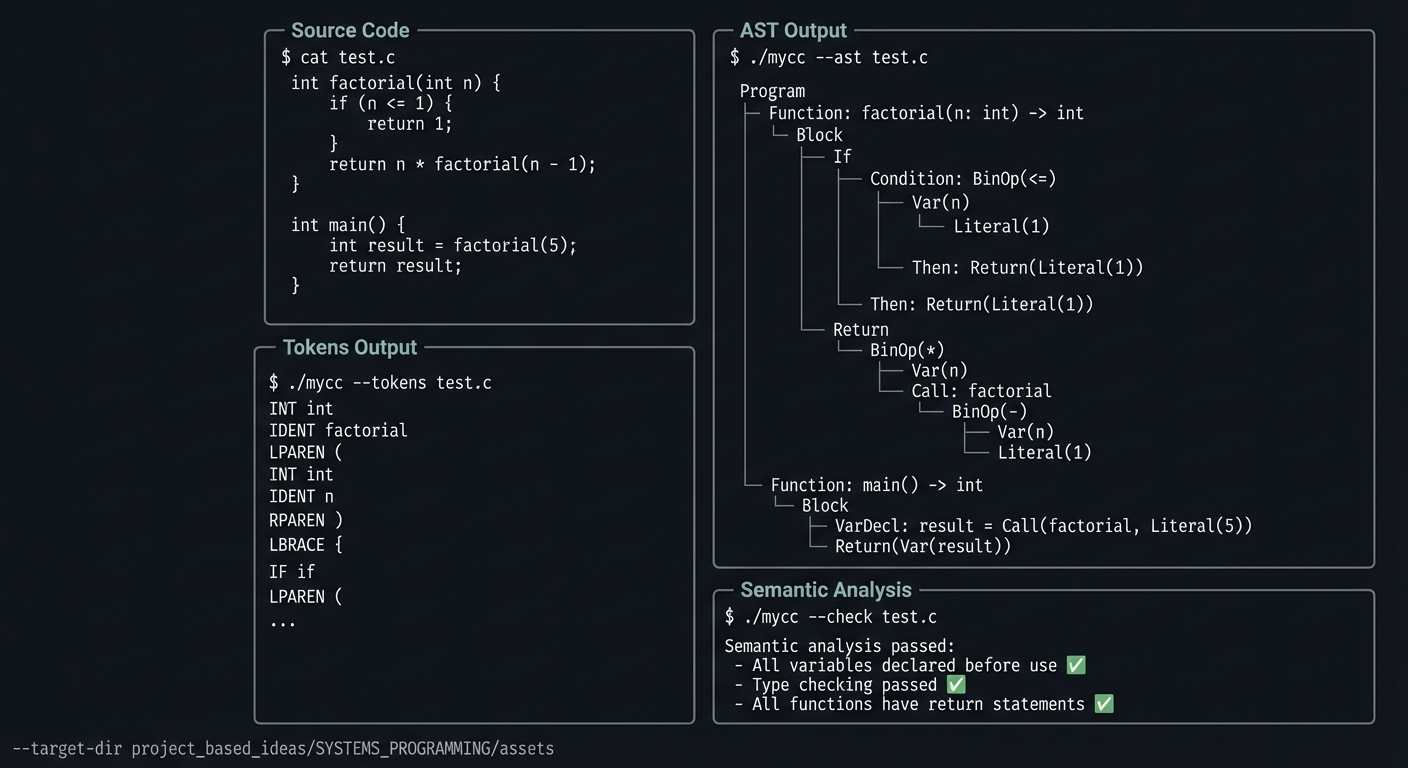

| Project 13: Compiler Frontend | Lexing, parsing, ASTs, semantic checks |

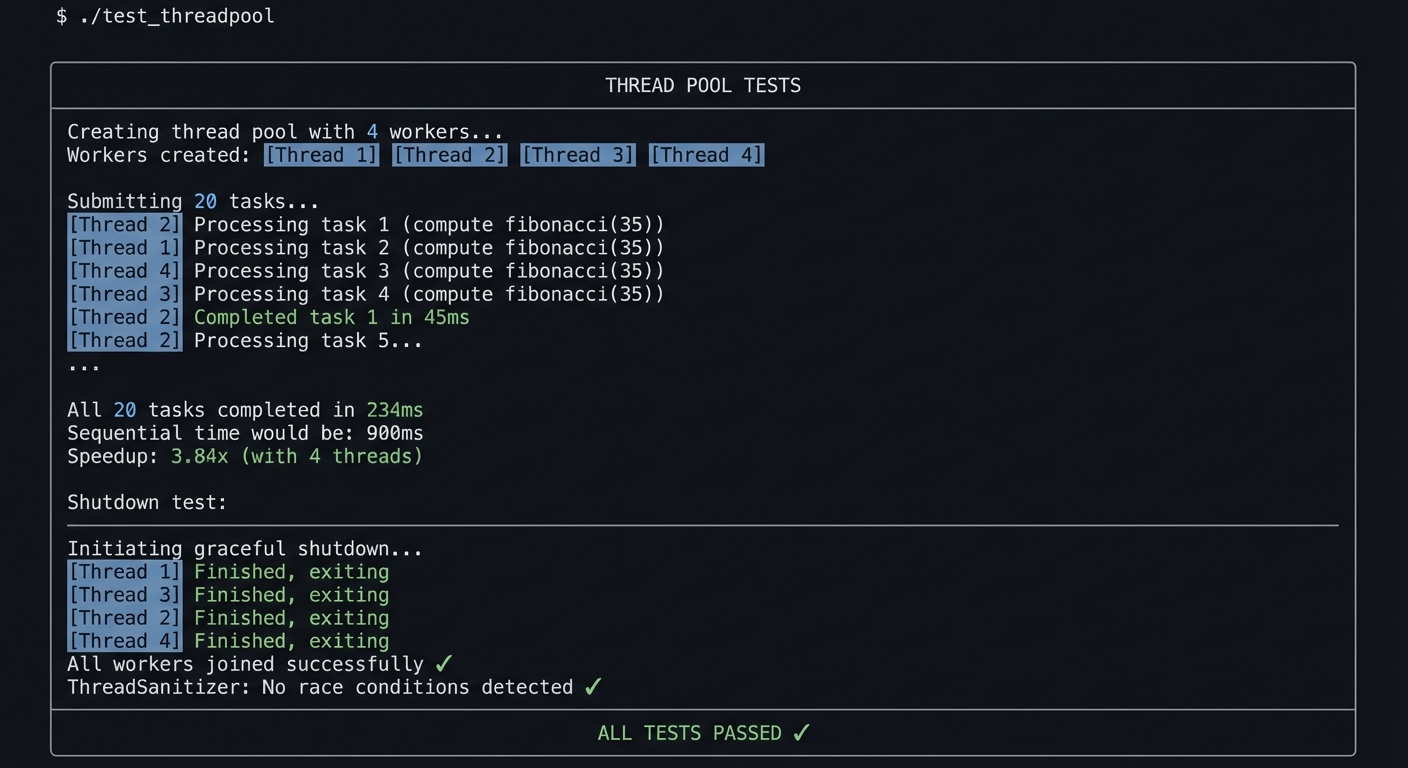

| Project 14: Thread Pool | Work queues, synchronization, shutdown semantics |

| Project 15: Bare-Metal Blinker | Memory-mapped I/O, linker scripts, startup runtime |

| Project 16: Operating System Kernel | Integration of memory, processes, interrupts, storage |

Quick Start

Day 1:

- Read the memory, pointers, and compilation chapters in the Theory Primer.

- Build Project 1 and verify address output under

gdb. - Set up sanitizer-enabled compile flags.

Day 2:

- Build Project 2 and write failure-case tests.

- Complete the first thinking exercise for Project 3.

- Fill a one-page learning log: bug, root cause, verification command.

Recommended Learning Paths

Path 1: Foundations First

- Project 1 -> 2 -> 3 -> 4 -> 5 -> 6

Path 2: Systems Practitioner

- Project 1 -> 6 -> 8 -> 9 -> 10 -> 14

Path 3: Toolchain + Language Internals

- Project 1 -> 2 -> 8 -> 12 -> 13

Path 4: Embedded + Low-Level Control

- Project 1 -> 6 -> 15 -> Final OS project

Success Metrics

- You can explain and debug a memory bug from raw addresses and bytes.

- You can design C APIs with explicit ownership and cleanup contracts.

- You can trace build/link/runtime failures to the correct pipeline stage.

- You can ship at least three projects with reproducible tests and stress cases.

- You can defend synchronization and error-handling choices in interview-style discussion.

Project Overview Table

| # | Project | Core Topics | Difficulty |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Memory Visualizer | Memory layout, pointers | Beginner |

| 2 | String Library | Null-termination, bounds | Intermediate |

| 3 | Dynamic Array | Resizing, amortized growth | Intermediate |

| 4 | Linked List Library | Node ownership, traversal | Intermediate |

| 5 | Hash Table | Hashing, collisions | Advanced |

| 6 | Memory Allocator | Heap internals, free lists | Expert |

| 7 | Configuration Parser | Parsing, validation | Intermediate |

| 8 | Build System (Mini-Make) | DAGs, rebuild logic | Advanced |

| 9 | Unix Shell | Processes, pipes, signals | Expert |

| 10 | HTTP Server | Sockets, protocol handling | Advanced |

| 11 | Database Engine | Storage/indexing basics | Expert |

| 12 | Debugger | ptrace, breakpoints | Master |

| 13 | Compiler Frontend | Lexing/parsing/AST | Expert |

| 14 | Thread Pool | Concurrency, synchronization | Expert |

| 15 | Bare Metal LED Blinker | Registers, startup code | Expert |

| 16 | Operating System Kernel | Full-stack systems integration | Master |

Project List

Projects are ordered from fundamental understanding to professional mastery. Each project builds on previous knowledge.

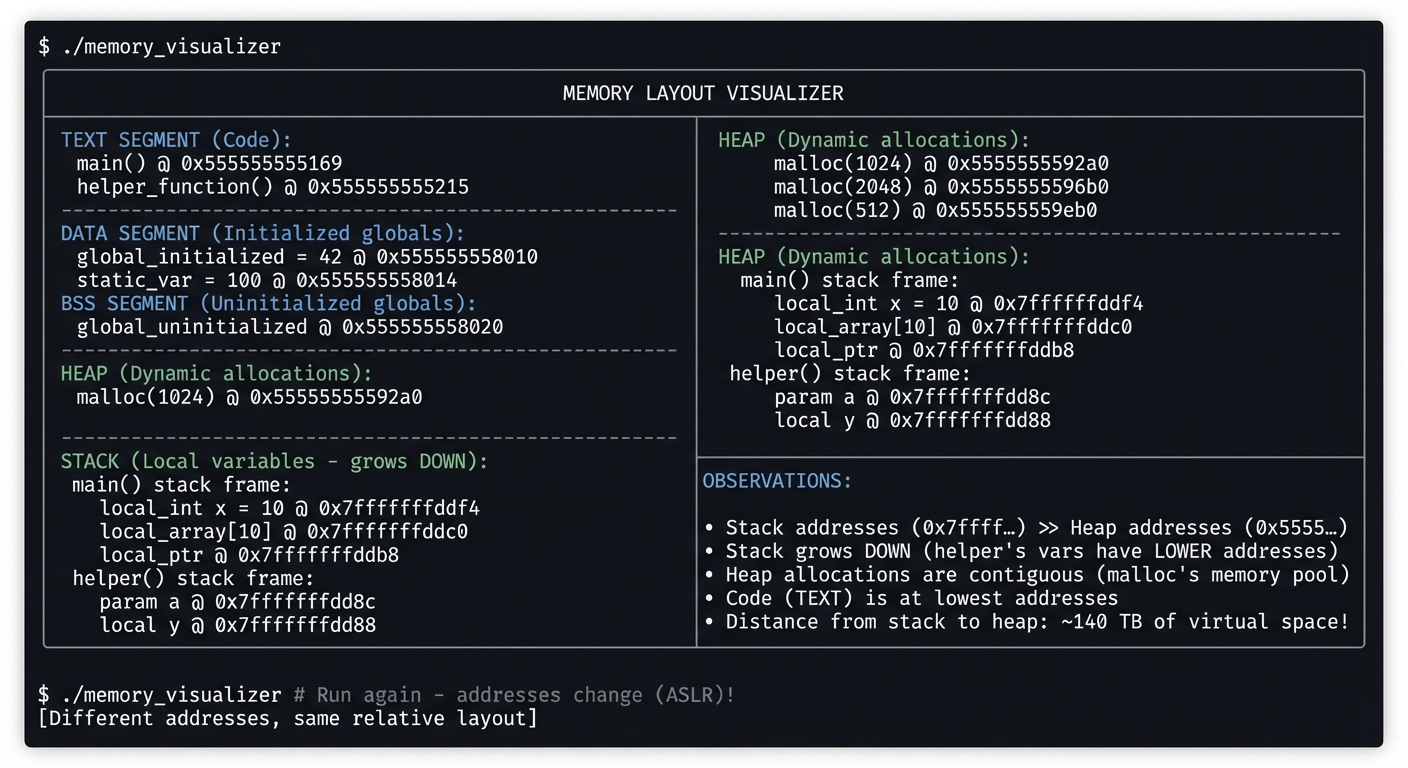

Project 1: Memory Visualizer — See Where Your Variables Live

- File: C_PROGRAMMING_COMPLETE_MASTERY.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Go, Zig

- Coolness Level: Level 4: Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 1: Beginner

- Knowledge Area: Memory Layout / Pointers

- Software or Tool: GDB, Address Sanitizer

- Main Book: Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective by Bryant & O’Hallaron

What you’ll build: A program that prints the exact memory addresses of different variable types—locals, globals, heap allocations, function pointers—showing you the actual memory layout of a running C program.

Why it teaches C: Before you can master pointers and memory management, you need to see memory. This project forces you to print addresses, observe where different variables live, and understand that memory is just a big array of numbered boxes.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Printing addresses with

%p→ maps to understanding pointer format specifiers - Distinguishing stack vs heap vs data → maps to process memory layout

- Watching addresses change across runs (ASLR) → maps to security features

- Understanding why some addresses are close and others far → maps to memory segments

Key Concepts:

- Process memory layout: CS:APP Ch. 9.9 — Bryant & O’Hallaron

- Pointer basics: C Programming: A Modern Approach Ch. 11 — K.N. King

- Virtual memory: Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces Ch. 13-15 — Arpaci-Dusseau

Difficulty: Beginner Time estimate: Weekend Prerequisites: Basic C syntax (variables, functions, printf)

Real World Outcome

You’ll have a program that when run, displays a complete map of where everything lives in memory:

Example Output:

$ ./memory_visualizer

╔════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╗

║ MEMORY LAYOUT VISUALIZER ║

╠════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╣

║ ║

║ TEXT SEGMENT (Code): ║

║ ───────────────────── ║

║ main() @ 0x555555555169 ║

║ helper_function() @ 0x555555555215 ║

║ ║

║ DATA SEGMENT (Initialized globals): ║

║ ───────────────────────────────────── ║

║ global_initialized = 42 @ 0x555555558010 ║

║ static_var = 100 @ 0x555555558014 ║

║ ║

║ BSS SEGMENT (Uninitialized globals): ║

║ ──────────────────────────────────── ║

║ global_uninitialized @ 0x555555558020 ║

║ ║

║ HEAP (Dynamic allocations): ║

║ ────────────────────────── ║

║ malloc(1024) @ 0x5555555592a0 ║

║ malloc(2048) @ 0x5555555596b0 ║

║ malloc(512) @ 0x555555559eb0 ║

║ ║

║ STACK (Local variables - grows DOWN): ║

║ ───────────────────────────────────── ║

║ main() stack frame: ║

║ local_int x = 10 @ 0x7fffffffddf4 ║

║ local_array[10] @ 0x7fffffffddc0 ║

║ local_ptr @ 0x7fffffffddb8 ║

║ helper() stack frame: ║

║ param a @ 0x7fffffffdd8c ║

║ local y @ 0x7fffffffdd88 ║

║ ║

╠════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╣

║ OBSERVATIONS: ║

║ • Stack addresses (0x7fff...) >> Heap addresses (0x5555...) ║

║ • Stack grows DOWN (helper's vars have LOWER addresses) ║

║ • Heap allocations are contiguous (malloc's memory pool) ║

║ • Code (TEXT) is at lowest addresses ║

║ • Distance from stack to heap: ~140 TB of virtual space! ║

╚════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╝

$ ./memory_visualizer # Run again - addresses change (ASLR)!

[Different addresses, same relative layout]

The Core Question You’re Answering

“What IS memory? Where do my variables actually live, and why does it matter?”

Before you write any code, sit with this question. Most programmers have a vague sense of “variables” but can’t explain where they actually are. A variable is just a label for a location in a giant array of bytes. Understanding this transforms how you think about C.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Virtual Memory

- What’s the difference between virtual and physical addresses?

- Why does your program see addresses like 0x7fff… when you only have 16GB RAM?

- What is ASLR and why do addresses change between runs?

- Book Reference: CS:APP Ch. 9.1-9.4 — Bryant & O’Hallaron

- Process Memory Segments

- What’s stored in TEXT, DATA, BSS, HEAP, and STACK?

- Why are they in that order?

- What happens when stack meets heap?

- Book Reference: The Linux Programming Interface Ch. 6 — Kerrisk

- Pointer Basics

- What does

&xactually return? - What’s the difference between

int *pandint p? - How do you print an address?

- Book Reference: C Programming: A Modern Approach Ch. 11 — K.N. King

- What does

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Variable Categories

- What types of variables should you include? (global, static, local, dynamic)

- How will you demonstrate the difference between initialized and uninitialized globals?

- How will you show function addresses?

- Output Design

- How will you organize the output to clearly show the memory layout?

- How will you make the addresses comparable (sorting, grouping)?

- Should you calculate and display the distance between segments?

- Demonstration

- How will you show that the stack grows downward?

- How will you demonstrate heap allocation patterns?

- Can you show what happens with nested function calls?

Thinking Exercise

Trace the Addresses

Before coding, predict what you’ll see:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int global = 42;

int uninitialized;

void func(int param) {

int local = 10;

printf("param: %p\n", (void*)¶m);

printf("local: %p\n", (void*)&local);

}

int main() {

int x = 5;

int *heap = malloc(100);

printf("global: %p\n", (void*)&global);

printf("uninit: %p\n", (void*)&uninitialized);

printf("x: %p\n", (void*)&x);

printf("heap: %p\n", (void*)heap);

printf("main: %p\n", (void*)main);

printf("func: %p\n", (void*)func);

func(99);

free(heap);

return 0;

}

Questions while tracing:

- Which address will be highest? Which lowest?

- Will

paramandlocalinfunchave higher or lower addresses thanxinmain? - Will

globalanduninitializedhave similar addresses? - Will

mainandfunchave similar addresses?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “Explain the memory layout of a C program.”

- “What’s the difference between stack and heap memory?”

- “Why would you choose stack allocation vs heap allocation?”

- “What is a memory leak? How does it happen?”

- “What is ASLR and why is it used?”

- “What happens when you return a pointer to a local variable?”

- “How does the operating system prevent stack overflow into heap?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start Simple Just print the address of one local variable and one global variable. See the difference.

Hint 2: Add Categories Create separate sections: one for printing text/code addresses, one for data, one for heap allocations, one for stack.

Hint 3: Helper Functions Create a function that gets called from main. Print addresses of its local variables. Notice they’re LOWER than main’s locals (stack grows down).

Hint 4: Use GDB to Verify

Compile with -g, run in GDB, use info proc mappings to see the actual memory layout. Compare with your program’s output.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Process memory layout | CS:APP by Bryant & O’Hallaron | Ch. 9 |

| Pointer fundamentals | C Programming: A Modern Approach by K.N. King | Ch. 11 |

| Virtual memory concepts | Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces by Arpaci-Dusseau | Ch. 13-15 |

| Linux memory management | The Linux Programming Interface by Kerrisk | Ch. 6 |

Common Pitfalls and Debugging

Problem 1: “Works for simple inputs, fails on edge cases”

- Why: Invariants are implicit and not enforced at boundaries.

- Fix: Add explicit precondition checks and assertion-backed invariants.

- Quick test: Run dedicated edge-case tests under sanitizers.

Problem 2: “Intermittent or non-deterministic crashes”

- Why: Undefined behavior, uninitialized state, or races.

- Fix: Reproduce deterministically, isolate state transitions, then patch the root cause.

- Quick test: Use

-fsanitize=address,undefined(and thread sanitizer for concurrent projects).

Problem 3: “Performance collapses as input grows”

- Why: Hidden O(n^2) paths or excessive allocation/copying.

- Fix: Profile hot paths and redesign data movement strategy.

- Quick test: Benchmark with 10x and 100x workload sizes.

Definition of Done

- Core functionality for Memory Visualizer — See Where Your Variables Live works on reference inputs.

- Edge cases and failure paths are tested and documented.

- Reproducible test command exists and passes on a clean run.

- Sanitizer/static-analysis pass is clean for project scope.

Implementation Hints

The key insight is using the & operator to get addresses and %p to print them:

Print address: printf("%p\n", (void *)&variable);

Print value at pointer: printf("%d\n", *pointer);

Cast to void* for portability with %p

For the stack growth demonstration:

- Create a recursive function

- In each call, print the address of a local variable

- Watch addresses decrease (stack growing down)

For heap demonstration:

- Multiple malloc calls

- Print each returned address

- Notice they tend to be sequential

To observe segments:

- Compare addresses of: functions (TEXT), initialized globals (DATA), uninitialized globals (BSS), malloc’d memory (HEAP), local variables (STACK)

- The relative ordering reveals the memory layout

Learning milestones:

- You print addresses correctly → You understand pointer basics

- You identify which segment each variable is in → You understand memory layout

- You demonstrate stack growth direction → You understand function call mechanics

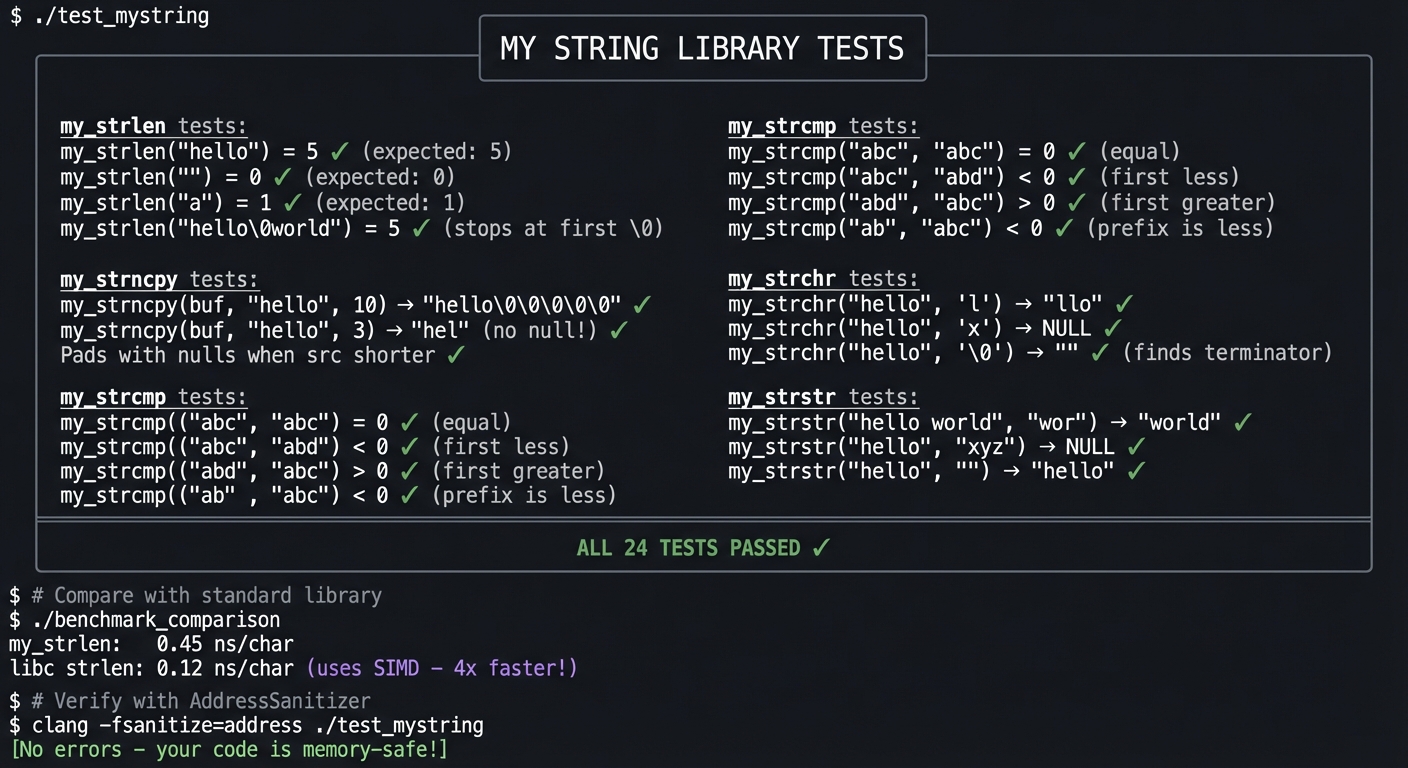

Project 2: String Library — Implement strlen, strcpy, strcmp from Scratch

- File: C_PROGRAMMING_COMPLETE_MASTERY.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Assembly (x86-64), Rust, Zig

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Strings / Pointers / Buffer Safety

- Software or Tool: Valgrind, AddressSanitizer

- Main Book: C Programming: A Modern Approach by K.N. King

What you’ll build: Your own implementation of the core C string functions—strlen, strcpy, strncpy, strcmp, strncmp, strcat, strchr, strstr—that handle edge cases correctly and match the behavior of the standard library.

Why it teaches C: Strings in C are the source of countless bugs and security vulnerabilities. By implementing these functions yourself, you’ll deeply understand null termination, buffer management, and why functions like strcpy are dangerous.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Walking memory until null terminator → maps to pointer arithmetic

- Preventing buffer overflows → maps to bounds checking discipline

- Handling edge cases (empty strings, NULL pointers) → maps to defensive programming

- Making your implementations as fast as the originals → maps to optimization

Key Concepts:

- String internals: C Programming: A Modern Approach Ch. 13 — K.N. King

- Secure string handling: Effective C Ch. 7 — Robert Seacord

- Buffer overflow vulnerabilities: Hacking: The Art of Exploitation Ch. 2 — Jon Erickson

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 1-2 weeks Prerequisites: Project 1 (Memory Visualizer), pointer arithmetic basics

Real World Outcome

You’ll have a complete string library that you can compile and link instead of using libc’s string functions:

Example Output:

$ ./test_mystring

╔════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╗

║ MY STRING LIBRARY TESTS ║

╠════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╣

║ ║

║ my_strlen tests: ║

║ ───────────────── ║

║ my_strlen("hello") = 5 ✓ (expected: 5) ║

║ my_strlen("") = 0 ✓ (expected: 0) ║

║ my_strlen("a") = 1 ✓ (expected: 1) ║

║ my_strlen("hello\0world") = 5 ✓ (stops at first \0) ║

║ ║

║ my_strcpy tests: ║

║ ───────────────── ║

║ my_strcpy(buf, "test") → "test" ✓ ║

║ Returns pointer to dest ✓ ║

║ Copies null terminator ✓ ║

║ ║

║ my_strncpy tests: ║

║ ───────────────── ║

║ my_strncpy(buf, "hello", 10) → "hello\0\0\0\0\0" ✓ ║

║ my_strncpy(buf, "hello", 3) → "hel" (no null!) ✓ ║

║ Pads with nulls when src shorter ✓ ║

║ ║

║ my_strcmp tests: ║

║ ───────────────── ║

║ my_strcmp("abc", "abc") = 0 ✓ (equal) ║

║ my_strcmp("abc", "abd") < 0 ✓ (first less) ║

║ my_strcmp("abd", "abc") > 0 ✓ (first greater) ║

║ my_strcmp("ab", "abc") < 0 ✓ (prefix is less) ║

║ ║

║ my_strchr tests: ║

║ ───────────────── ║

║ my_strchr("hello", 'l') → "llo" ✓ ║

║ my_strchr("hello", 'x') → NULL ✓ ║

║ my_strchr("hello", '\0') → "" ✓ (finds terminator) ║

║ ║

║ my_strstr tests: ║

║ ───────────────── ║

║ my_strstr("hello world", "wor") → "world" ✓ ║

║ my_strstr("hello", "xyz") → NULL ✓ ║

║ my_strstr("hello", "") → "hello" ✓ ║

║ ║

╠════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╣

║ ALL 24 TESTS PASSED ✓ ║

╚════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╝

$ # Compare with standard library

$ ./benchmark_comparison

my_strlen: 0.45 ns/char

libc strlen: 0.12 ns/char (uses SIMD - 4x faster!)

$ # Verify with AddressSanitizer

$ clang -fsanitize=address ./test_mystring

[No errors - your code is memory-safe!]

The Core Question You’re Answering

“Why are C strings the source of so many bugs, and what does ‘null-terminated’ really mean for safety?”

Before you write any code, sit with this question. A C “string” isn’t really a type—it’s a convention. It’s just bytes in memory until you hit a zero byte. If that zero is missing, string functions keep reading… and reading… into memory they shouldn’t touch.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Null Termination Convention

- What byte value is the null terminator?

- Why doesn’t C store string length?

- What happens if a string isn’t null-terminated?

- Book Reference: C Programming: A Modern Approach Ch. 13.1 — K.N. King

- Pointer Arithmetic

- What does

p++do whenpis achar *? - What about when

pis anint *? - How do you walk through a string character by character?

- Book Reference: C Programming: A Modern Approach Ch. 12 — K.N. King

- What does

- Buffer Overflow

- What happens when you copy a 20-byte string into a 10-byte buffer?

- Why is

strcpyconsidered dangerous? - How does

strncpyattempt to solve this (and why does it fail)? - Book Reference: Effective C Ch. 7.4 — Robert Seacord

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Edge Cases

- What should

strlen(NULL)do? (crash? return 0?) - What should

strcmp("", "")return? - What should

strchr("test", '\0')find?

- What should

- Return Values

- Why does

strcpyreturn the destination pointer? - Why does

strcmpreturn an int instead of just -1, 0, 1? - What should

strchrreturn if the character isn’t found?

- Why does

- The strncpy Problem

- When is

strncpy’s output NOT null-terminated? - Why does

strncpypad with nulls when src is shorter? - What’s a safer alternative you could design?

- When is

Thinking Exercise

Trace the Memory

Before coding, trace what happens with this code:

char dest[10];

strcpy(dest, "Hello, World!"); // 14 chars including \0

Questions while tracing:

- Draw the memory layout of

dest(10 boxes) - What gets written to positions 0-9?

- What gets written to positions 10-13?

- What memory did we just corrupt?

- Why might the program seem to work despite this bug?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “Implement

strlenfrom scratch.” - “Why is

strcpydangerous? What would you use instead?” - “What’s the difference between

strncpyandstrlcpy?” - “How would you implement

strstrefficiently?” - “What’s a buffer overflow and how do string functions cause them?”

- “Why do we need

memcpywhen we havestrcpy?” - “Implement

strcmp- what should it return for different inputs?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: strlen First

Start with strlen. It’s just counting: walk the pointer forward until you hit '\0', counting steps.

Hint 2: Use Pointer Walking

Instead of indexing str[i], try *str++. It’s more idiomatic C and forces you to think in pointers.

Hint 3: strcpy is strlen + memcpy

Once you understand walking to the null terminator, strcpy is just: copy each byte, including the final '\0'.

Hint 4: Test Edge Cases Early Write tests for empty strings, single characters, NULL pointers BEFORE you think you’re done. The edge cases reveal your bugs.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| String fundamentals | C Programming: A Modern Approach by K.N. King | Ch. 13 |

| Secure string handling | Effective C by Robert Seacord | Ch. 7 |

| Buffer overflow exploits | Hacking: Art of Exploitation by Erickson | Ch. 2-3 |

| String algorithms | Algorithms in C by Sedgewick | Ch. 19 |

Common Pitfalls and Debugging

Problem 1: “Works for simple inputs, fails on edge cases”

- Why: Invariants are implicit and not enforced at boundaries.

- Fix: Add explicit precondition checks and assertion-backed invariants.

- Quick test: Run dedicated edge-case tests under sanitizers.

Problem 2: “Intermittent or non-deterministic crashes”

- Why: Undefined behavior, uninitialized state, or races.

- Fix: Reproduce deterministically, isolate state transitions, then patch the root cause.

- Quick test: Use

-fsanitize=address,undefined(and thread sanitizer for concurrent projects).

Problem 3: “Performance collapses as input grows”

- Why: Hidden O(n^2) paths or excessive allocation/copying.

- Fix: Profile hot paths and redesign data movement strategy.

- Quick test: Benchmark with 10x and 100x workload sizes.

Definition of Done

- Core functionality for String Library — Implement strlen, strcpy, strcmp from Scratch works on reference inputs.

- Edge cases and failure paths are tested and documented.

- Reproducible test command exists and passes on a clean run.

- Sanitizer/static-analysis pass is clean for project scope.

Implementation Hints

The core pattern for walking a string:

// Pattern 1: Index-based

while (str[i] != '\0') {

// process str[i]

i++;

}

// Pattern 2: Pointer-based (more idiomatic C)

while (*str) { // *str is '\0' == 0 == false

// process *str

str++;

}

// Pattern 3: Compact pointer walking

while (*str++)

; // Just find the end

For strcmp, remember:

- Returns negative if s1 < s2

- Returns positive if s1 > s2

- Returns 0 if equal

- Compare character by character until mismatch or both reach ‘\0’

For strstr (find substring):

- Naive: O(n*m) - check every position

- Can mention KMP or Boyer-Moore for optimization (but implement naive first)

Learning milestones:

- strlen and strcpy work → You understand null termination

- strncpy handles all edge cases → You understand bounds checking

- strstr finds substrings correctly → You understand nested string traversal

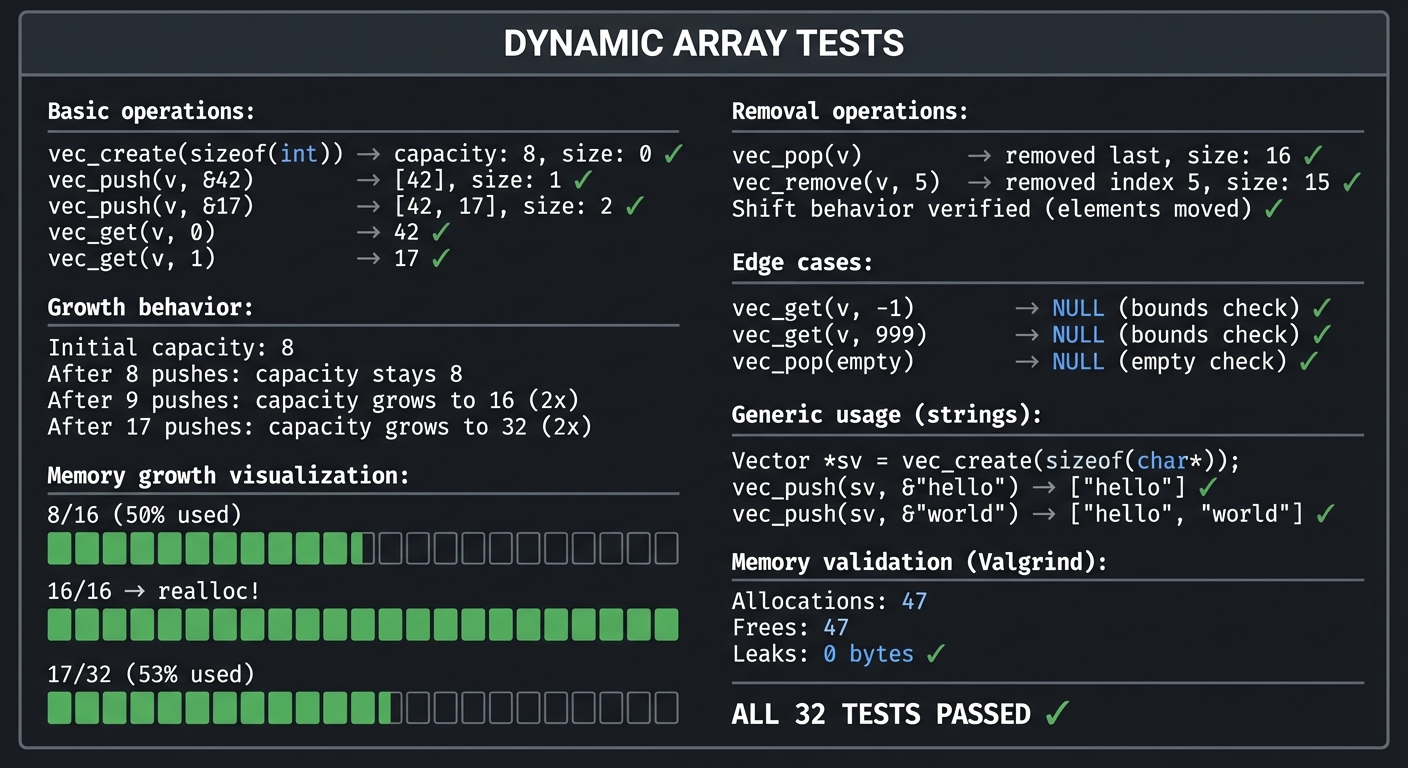

Project 3: Dynamic Array — Build a Vector/ArrayList in C

- File: C_PROGRAMMING_COMPLETE_MASTERY.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Zig, Go

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 2. The “Micro-SaaS / Pro Tool”

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Data Structures / Memory Management

- Software or Tool: Valgrind, GDB

- Main Book: Mastering Algorithms with C by Kyle Loudon

What you’ll build: A generic, resizable array (like C++’s std::vector or Java’s ArrayList) that automatically grows when full, with proper memory management and a clean API.

Why it teaches C: This is your first serious data structure in C. You’ll wrestle with malloc, realloc, and free. You’ll implement the growth strategy (typically 2x). You’ll feel the pain of manual memory management—and understand why it matters.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Growing the array when capacity is reached → maps to realloc behavior

- Maintaining size vs capacity → maps to data structure invariants

- Proper cleanup on destroy → maps to ownership and lifetime

- Making it generic (void pointers or macros) → maps to C’s approach to generics

Key Concepts:

- Dynamic memory: Effective C Ch. 6 — Robert Seacord

- Amortized analysis: Introduction to Algorithms Ch. 17 — CLRS

- C generics patterns: C Interfaces and Implementations Ch. 3 — Hanson

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 1 week Prerequisites: Projects 1-2 (Memory Visualizer, String Library), malloc/free basics

Real World Outcome

You’ll have a production-quality dynamic array that you can use in your own C projects:

Example Output:

$ ./test_vector

╔════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╗

║ DYNAMIC ARRAY TESTS ║

╠════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╣

║ ║

║ Basic operations: ║

║ ───────────────── ║

║ vec_create(sizeof(int)) → capacity: 8, size: 0 ✓ ║

║ vec_push(v, &42) → [42], size: 1 ✓ ║

║ vec_push(v, &17) → [42, 17], size: 2 ✓ ║

║ vec_get(v, 0) → 42 ✓ ║

║ vec_get(v, 1) → 17 ✓ ║

║ ║

║ Growth behavior: ║

║ ───────────────── ║

║ Initial capacity: 8 ║

║ After 8 pushes: capacity stays 8 ║

║ After 9 pushes: capacity grows to 16 (2x) ║

║ After 17 pushes: capacity grows to 32 (2x) ║

║ ║

║ Memory growth visualization: ║

║ [████████░░░░░░░░] 8/16 (50% used) ║

║ [████████████████] 16/16 → realloc! ║

║ [████████████████░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░] 17/32 (53% used) ║

║ ║

║ Removal operations: ║

║ ───────────────── ║

║ vec_pop(v) → removed last, size: 16 ✓ ║

║ vec_remove(v, 5) → removed index 5, size: 15 ✓ ║

║ Shift behavior verified (elements moved) ✓ ║

║ ║

║ Edge cases: ║

║ ───────────────── ║

║ vec_get(v, -1) → NULL (bounds check) ✓ ║

║ vec_get(v, 999) → NULL (bounds check) ✓ ║

║ vec_pop(empty) → NULL (empty check) ✓ ║

║ ║

║ Generic usage (strings): ║

║ ───────────────── ║

║ Vector *sv = vec_create(sizeof(char*)); ║

║ vec_push(sv, &"hello") → ["hello"] ✓ ║

║ vec_push(sv, &"world") → ["hello", "world"] ✓ ║

║ ║

║ Memory validation (Valgrind): ║

║ ───────────────── ║

║ Allocations: 47 ║

║ Frees: 47 ║

║ Leaks: 0 bytes ✓ ║

║ ║

╠════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╣

║ ALL 32 TESTS PASSED ✓ ║

╚════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╝

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do I create a data structure that grows dynamically when I don’t know the size upfront, without leaking memory?”

Before you write any code, sit with this question. Fixed-size arrays are limiting. But dynamic growth means reallocating memory, copying data, and tracking ownership. This is where C gets real.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- malloc, realloc, free

- What does

malloc(n)return? - What does

realloc(ptr, newsize)do to the old memory? - What happens if you

free()twice? - Book Reference: Effective C Ch. 6 — Robert Seacord

- What does

- Amortized Complexity

- Why grow by 2x instead of by 1?

- What’s the amortized cost of n push operations?

- What’s the worst case for a single push?

- Book Reference: Introduction to Algorithms Ch. 17 — CLRS

- Generics in C

- How do you store “any type” when C has no generics?

- What is

void *and how do you use it? - What’s the memcpy approach vs the macro approach?

- Book Reference: C Interfaces and Implementations Ch. 3 — Hanson

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Data Structure Design

- What fields does your vector struct need? (data, size, capacity, element_size?)

- Should the struct be opaque (hide internals)?

- How do you handle different element sizes?

- Growth Policy

- When exactly do you grow? (at capacity? when push would overflow?)

- By how much? (2x? 1.5x? add constant?)

- Should you ever shrink?

- API Design

- What should

vec_getreturn? (value? pointer?) - How do you handle out-of-bounds access?

- Should push take a pointer or a value?

- What should

Thinking Exercise

Trace the Growth

Before coding, trace these operations:

vec_create() → capacity=8, size=0

push 10 elements → ???

Questions while tracing:

- After push 1-8, what are capacity and size?

- When does the first realloc happen?

- Where does realloc put the new memory?

- What happens to the old memory?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “Implement a dynamic array in C.”

- “Why grow by 2x? What’s the amortized complexity?”

- “What happens if realloc fails?”

- “How do you make a vector generic in C?”

- “What’s the difference between size and capacity?”

- “How would you implement shrinking?”

- “What memory errors could occur with a dynamic array?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start Fixed

First, build a vector that works with int only. Don’t try to make it generic yet.

Hint 2: Growth First

Implement push and get first. Don’t worry about remove or pop until growth works perfectly.

Hint 3: Check realloc Return

realloc can fail and return NULL. If you do v->data = realloc(v->data, ...) and it fails, you’ve lost your data!

Hint 4: Make Generic Last

Once int version works, change int *data to void *data, add elem_size, and use memcpy for moving elements.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic memory | Effective C by Seacord | Ch. 6 |

| Data structure design | Mastering Algorithms with C by Loudon | Ch. 4 |

| Generic ADTs in C | C Interfaces and Implementations by Hanson | Ch. 3 |

| Amortized analysis | Introduction to Algorithms by CLRS | Ch. 17 |

Common Pitfalls and Debugging

Problem 1: “Works for simple inputs, fails on edge cases”

- Why: Invariants are implicit and not enforced at boundaries.

- Fix: Add explicit precondition checks and assertion-backed invariants.

- Quick test: Run dedicated edge-case tests under sanitizers.

Problem 2: “Intermittent or non-deterministic crashes”

- Why: Undefined behavior, uninitialized state, or races.

- Fix: Reproduce deterministically, isolate state transitions, then patch the root cause.

- Quick test: Use

-fsanitize=address,undefined(and thread sanitizer for concurrent projects).

Problem 3: “Performance collapses as input grows”

- Why: Hidden O(n^2) paths or excessive allocation/copying.

- Fix: Profile hot paths and redesign data movement strategy.

- Quick test: Benchmark with 10x and 100x workload sizes.

Definition of Done

- Core functionality for Dynamic Array — Build a Vector/ArrayList in C works on reference inputs.

- Edge cases and failure paths are tested and documented.

- Reproducible test command exists and passes on a clean run.

- Sanitizer/static-analysis pass is clean for project scope.

Implementation Hints

The struct needs at minimum:

- void *data // pointer to the actual array

- size_t size // number of elements currently stored

- size_t capacity // total slots available

- size_t elem_size // sizeof each element (for generics)

Key operation - growing:

1. Check if size == capacity

2. If so, new_capacity = capacity * 2

3. temp = realloc(data, new_capacity * elem_size)

4. If temp is NULL, return error (don't lose data!)

5. data = temp

6. capacity = new_capacity

For generic element access:

// Get pointer to element at index i

void *elem = (char *)v->data + (i * v->elem_size);

Learning milestones:

- Basic int vector works → You understand dynamic allocation

- Growth works without leaks → You understand realloc

- Generic version works → You understand void* and memcpy

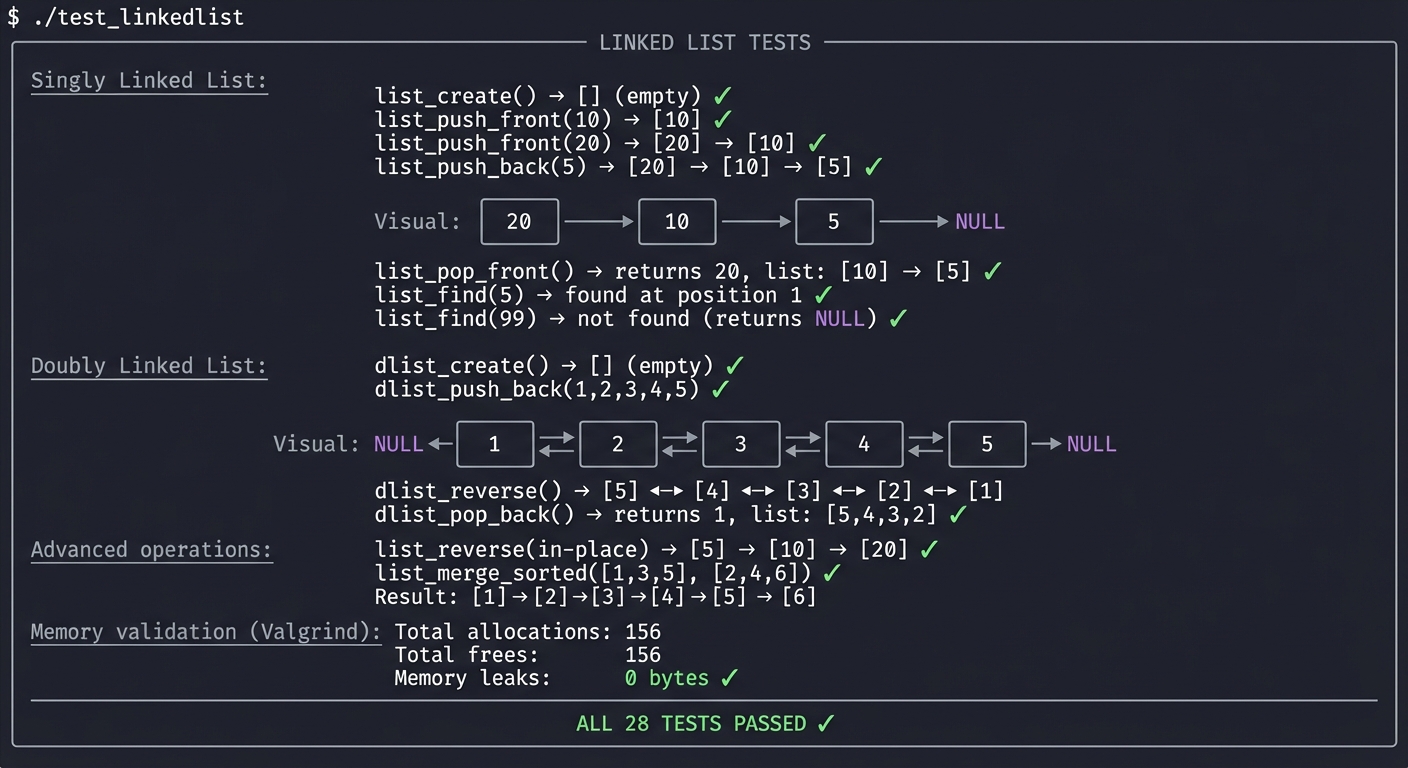

Project 4: Linked List Library — Singly and Doubly Linked Lists

- File: C_PROGRAMMING_COMPLETE_MASTERY.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Go, Zig

- Coolness Level: Level 2: Practical but Forgettable

- Business Potential: 1. The “Resume Gold”

- Difficulty: Level 2: Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: Data Structures / Pointers / Memory

- Software or Tool: Valgrind, GDB

- Main Book: Mastering Algorithms with C by Kyle Loudon

What you’ll build: A complete linked list library supporting both singly and doubly linked lists with operations like insert, delete, search, reverse, and merge—all with proper memory management and iterator patterns.

Why it teaches C: Linked lists are the purest expression of pointer manipulation. Every operation involves pointer rewiring. You’ll face dangling pointers, memory leaks, and the classic “lost node” bug. Mastering linked lists means mastering pointers.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Inserting at head, tail, and middle → maps to pointer rewiring

- Deleting without losing references → maps to maintaining invariants

- Reversing without extra memory → maps to in-place algorithms

- Not leaking memory on any operation → maps to ownership discipline

Key Concepts:

- Linked data structures: Mastering Algorithms with C Ch. 5 — Kyle Loudon

- Pointer manipulation: C Programming: A Modern Approach Ch. 17.5 — K.N. King

- Iterator pattern in C: C Interfaces and Implementations Ch. 6 — Hanson

Difficulty: Intermediate Time estimate: 1 week Prerequisites: Projects 1-3, confident with malloc/free

Real World Outcome

You’ll have a linked list library that handles all common operations:

Example Output:

$ ./test_linkedlist

╔════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╗

║ LINKED LIST TESTS ║

╠════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╣

║ ║

║ Singly Linked List: ║

║ ─────────────────── ║

║ list_create() → [] (empty) ✓ ║

║ list_push_front(10) → [10] ✓ ║

║ list_push_front(20) → [20] → [10] ✓ ║

║ list_push_back(5) → [20] → [10] → [5] ✓ ║

║ ║

║ Visual: ║

║ ┌────┐ ┌────┐ ┌────┐ ║

║ │ 20 │───►│ 10 │───►│ 5 │───► NULL ║

║ └────┘ └────┘ └────┘ ║

║ ║

║ list_pop_front() → returns 20, list: [10] → [5] ✓ ║

║ list_find(5) → found at position 1 ✓ ║

║ list_find(99) → not found (returns NULL) ✓ ║

║ ║

║ Doubly Linked List: ║

║ ─────────────────── ║

║ dlist_create() → [] (empty) ✓ ║

║ dlist_push_back(1,2,3,4,5) ✓ ║

║ ║

║ Visual: ║

║ NULL ◄──┌────┐◄──►┌────┐◄──►┌────┐◄──►┌────┐◄──►┌────┐──► NULL

║ │ 1 │ │ 2 │ │ 3 │ │ 4 │ │ 5 │

║ └────┘ └────┘ └────┘ └────┘ └────┘

║ ║

║ dlist_reverse() → [5] ◄──► [4] ◄──► [3] ◄──► [2] ◄──► [1]

║ dlist_pop_back() → returns 1, list: [5,4,3,2] ✓ ║

║ ║

║ Advanced operations: ║

║ ─────────────────── ║

║ list_reverse(in-place) → [5] → [10] → [20] ✓ ║

║ list_merge_sorted([1,3,5], [2,4,6]) ✓ ║

║ Result: [1] → [2] → [3] → [4] → [5] → [6] ║

║ ║

║ Memory validation (Valgrind): ║

║ ───────────────────────────── ║

║ Total allocations: 156 ║

║ Total frees: 156 ║

║ Memory leaks: 0 bytes ✓ ║

║ ║

╠════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╣

║ ALL 28 TESTS PASSED ✓ ║

╚════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╝

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do you manipulate memory at the pointer level, rewiring references without losing data or leaking memory?”

Before you write any code, sit with this question. Linked lists are pointer surgery. Every insert and delete requires carefully updating multiple pointers in the right order—one mistake and you either lose nodes or corrupt memory.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Node Structure

- What fields does a linked list node need?

- Why does a doubly linked list node need two pointers?

- When would you embed data vs. point to it?

- Book Reference: Mastering Algorithms with C Ch. 5 — Loudon

- Pointer Rewiring

- When inserting after node A, what pointers must change?

- When deleting node B, how do you preserve the list?

- What’s the order of operations to avoid losing references?

- Book Reference: C Programming: A Modern Approach Ch. 17.5 — King

- Edge Cases

- What’s special about inserting at the head?

- What’s special about inserting at the tail?

- What if the list is empty?

- Book Reference: Mastering Algorithms with C Ch. 5.2-5.3 — Loudon

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- API Design

- Do you need a separate “List” struct, or just pass around the head node?

- Should you track the tail for O(1) push_back?

- Should you track the size?

- Deletion Challenges

- When deleting a node, how do you get the previous node in a singly linked list?

- Would a “delete this node” function work differently than “delete value X”?

- How do you handle deleting the head?

- Generic Support

- Will your list store ints, void*, or use macros?

- How will the user provide a comparison function for find/delete?

Thinking Exercise

Trace the Insertion

Before coding, draw what happens step by step:

// Inserting 15 after the node containing 10

// List: [5] → [10] → [20] → NULL

Node *new = malloc(sizeof(Node));

new->data = 15;

new->next = ???; // What goes here?

??? = new; // What pointer needs to change?

Questions while tracing:

- Draw the list before insertion

- Draw the list with the new node “floating” (not connected)

- Show which pointer gets set first

- Show the final connected state

- What if you set them in the wrong order?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “Implement a linked list from scratch.”

- “Reverse a linked list in place.”

- “Detect a cycle in a linked list.” (Floyd’s algorithm)

- “Find the middle element in one pass.”

- “Merge two sorted linked lists.”

- “What’s the time complexity of insert/delete/search?”

- “When would you use a linked list over an array?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Draw Everything Draw the list before and after every operation. Circle the pointers that change. This visualization prevents 90% of bugs.

Hint 2: Handle Empty/Single First Before implementing general insert, handle the edge cases: insert into empty list, insert into single-node list.

Hint 3: Deletion Order When deleting: (1) save pointer to node-to-delete, (2) rewire previous->next, (3) THEN free the deleted node.

Hint 4: Use a Dummy Head For simpler code, some implementations use a dummy/sentinel head node. The first real element is dummy->next. This eliminates head-special-case code.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Linked list fundamentals | Mastering Algorithms with C by Loudon | Ch. 5 |

| Pointer manipulation | C Programming: A Modern Approach by King | Ch. 17 |

| Classic problems | Cracking the Coding Interview by McDowell | Ch. 2 |

| Iterator pattern | C Interfaces and Implementations by Hanson | Ch. 6 |

Common Pitfalls and Debugging

Problem 1: “Works for simple inputs, fails on edge cases”

- Why: Invariants are implicit and not enforced at boundaries.

- Fix: Add explicit precondition checks and assertion-backed invariants.

- Quick test: Run dedicated edge-case tests under sanitizers.

Problem 2: “Intermittent or non-deterministic crashes”

- Why: Undefined behavior, uninitialized state, or races.

- Fix: Reproduce deterministically, isolate state transitions, then patch the root cause.

- Quick test: Use

-fsanitize=address,undefined(and thread sanitizer for concurrent projects).

Problem 3: “Performance collapses as input grows”

- Why: Hidden O(n^2) paths or excessive allocation/copying.

- Fix: Profile hot paths and redesign data movement strategy.

- Quick test: Benchmark with 10x and 100x workload sizes.

Definition of Done

- Core functionality for Linked List Library — Singly and Doubly Linked Lists works on reference inputs.

- Edge cases and failure paths are tested and documented.

- Reproducible test command exists and passes on a clean run.

- Sanitizer/static-analysis pass is clean for project scope.

Implementation Hints

Singly linked list node:

struct Node {

void *data; // or int data for simple version

struct Node *next;

};

Doubly linked list node:

struct DNode {

void *data;

struct DNode *prev;

struct DNode *next;

};

Insert after node (singly linked):

1. new_node->next = current->next

2. current->next = new_node

// Order matters! Reverse these and you lose the rest of the list

Delete node (singly linked):

1. Find prev such that prev->next == target

2. prev->next = target->next

3. free(target)

// Finding prev requires traversal - O(n)!

Reverse in place (singly linked):

prev = NULL

curr = head

while curr:

next = curr->next // Save next before we lose it

curr->next = prev // Reverse the link

prev = curr // Move prev forward

curr = next // Move curr forward

head = prev // New head is old tail

Learning milestones:

- Insert/delete at head works → You understand basic pointer manipulation

- Insert/delete anywhere works → You understand traversal and rewiring

- Reverse in place works → You understand in-place pointer algorithms

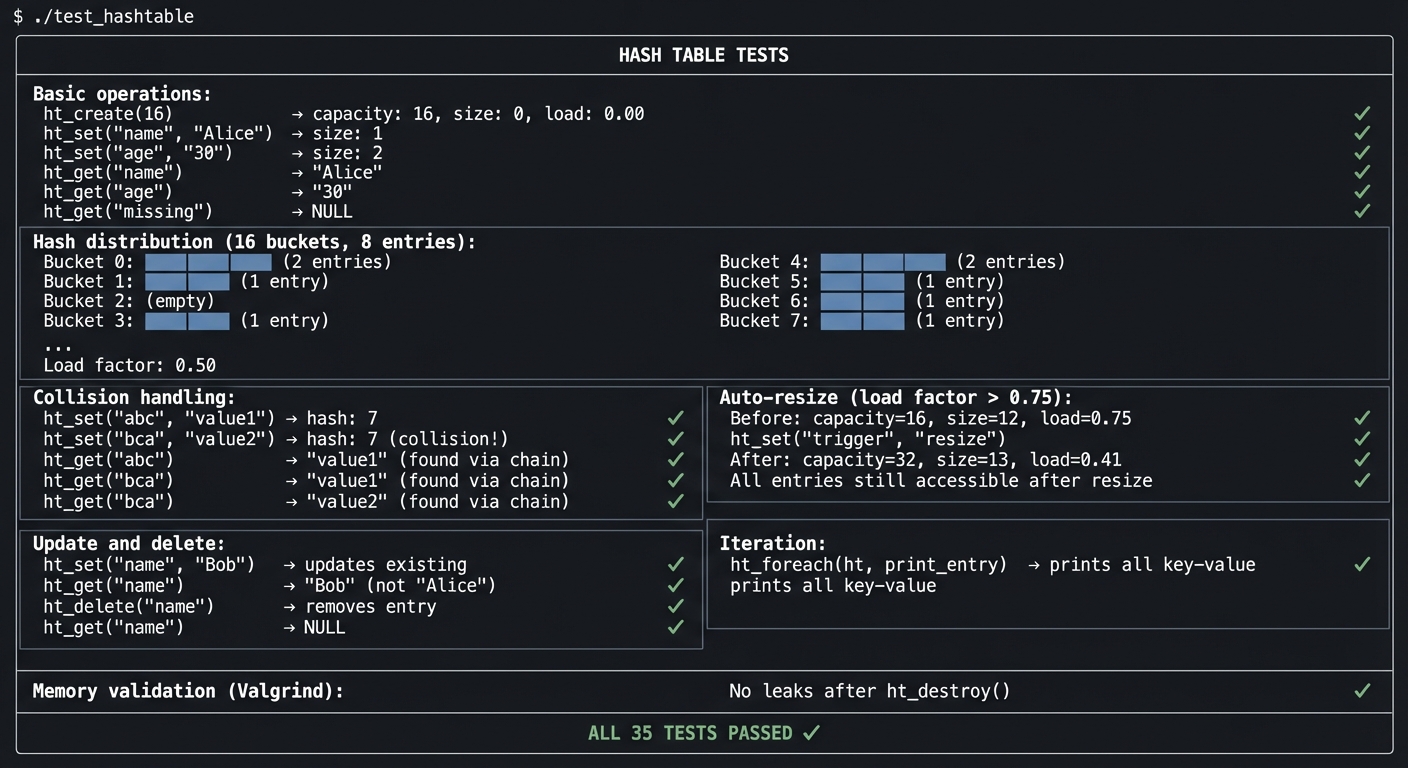

Project 5: Hash Table — Build Your Own Dictionary

- File: C_PROGRAMMING_COMPLETE_MASTERY.md

- Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Go, Zig

- Coolness Level: Level 3: Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: 2. The “Micro-SaaS / Pro Tool”

- Difficulty: Level 3: Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Data Structures / Hashing / Collision Resolution

- Software or Tool: Valgrind, Performance profiler

- Main Book: Mastering Algorithms with C by Kyle Loudon

What you’ll build: A hash table (dictionary/map) supporting string keys and arbitrary values, with a good hash function, collision resolution via chaining, dynamic resizing, and proper memory management.

Why it teaches C: Hash tables combine everything: dynamic memory, linked lists (for chaining), pointer manipulation, and algorithm design. You’ll implement a hash function, understand load factors, and see why resizing is expensive but necessary.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Implementing a good hash function → maps to bit manipulation and math

- Collision resolution (chaining vs. open addressing) → maps to data structure tradeoffs

- Resizing when load factor exceeds threshold → maps to amortized complexity

- Handling string keys with proper ownership → maps to memory ownership patterns

Key Concepts:

- Hash table internals: Mastering Algorithms with C Ch. 8 — Kyle Loudon

- Hash functions: Introduction to Algorithms Ch. 11 — CLRS

- Load factor and resizing: Algorithms by Sedgewick & Wayne — Ch. 3.4

Difficulty: Advanced Time estimate: 1-2 weeks Prerequisites: Projects 1-4, linked list implementation

Real World Outcome

You’ll have a production-quality hash table you can use in any C project:

Example Output:

$ ./test_hashtable

╔════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╗

║ HASH TABLE TESTS ║

╠════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╣

║ ║

║ Basic operations: ║

║ ───────────────── ║

║ ht_create(16) → capacity: 16, size: 0, load: 0.00 ✓ ║

║ ht_set("name", "Alice") → size: 1 ✓ ║

║ ht_set("age", "30") → size: 2 ✓ ║

║ ht_get("name") → "Alice" ✓ ║

║ ht_get("age") → "30" ✓ ║

║ ht_get("missing") → NULL ✓ ║

║ ║

║ Hash distribution (16 buckets, 8 entries): ║