Bootloader Deep Dive: Project-Based Learning

Goal: Master the boot process from power-on to operating system—understand what happens in the first milliseconds of a computer’s life, how CPUs transition through privilege modes, how firmware initializes hardware, and how bootloaders bridge the gap between raw silicon and your operating system. By completing these projects, you’ll be able to write bootloaders from scratch, debug boot issues at any level, and deeply understand the x86, UEFI, and ARM boot architectures.

Prerequisites & Background Knowledge

Essential Prerequisites (Must Have)

Before diving into bootloader development, you need:

1. Programming Skills

- Assembly Language: Basic understanding of x86 assembly (registers, instructions, jumps)

- Self-check: Can you explain what

MOV AX, 0x1234does? - Self-check: Do you understand what a register is?

- Self-check: Can you explain what

- C Programming: Comfortable with pointers, memory addresses, structs, and bit manipulation

- Self-check: Can you explain the difference between

char *ptrandchar ptr[]? - Self-check: Do you know how to set bit 5 in a byte using bitwise operators?

- Self-check: Can you explain the difference between

2. Computer Architecture Fundamentals

- How CPUs execute instructions: Fetch-decode-execute cycle

- Memory hierarchy: Registers, RAM, storage

- Binary and hexadecimal: Fluent conversion and arithmetic

- Self-check: What is 0x7C00 in decimal? (Answer: 31744)

- Self-check: What is 0xAA55 in binary?

3. Operating Systems Basics (Conceptual)

- What an OS kernel does: Process management, memory management, I/O

- User space vs kernel space: Privilege levels and protection

- File systems at a high level: How data is stored on disks

Helpful But Not Required

These concepts will be learned through the projects:

- Protected mode, long mode, paging: Projects 3, 6, and 8 teach these

- UEFI architecture: Project 7 introduces this

- ELF binary format: Project 8 covers this in depth

- ARM architecture: Projects 9-10 explore this

Self-Assessment Questions

Ready to start if you can answer:

- ✓ What happens when the CPU executes an instruction at address 0x7C00?

- ✓ Why would you use assembly instead of C for a bootloader?

- ✓ What’s the difference between physical and virtual memory?

- ✓ What does “boot” actually mean at a technical level?

Need more preparation if:

- ✗ You’ve never written any assembly code

- ✗ You don’t know what hexadecimal numbers are

- ✗ You’ve never used a command-line debugger (GDB, LLDB)

- ✗ You’re unfamiliar with the concept of CPU registers

Development Environment Setup

Required Tools:

- Assembler: NASM (Netwide Assembler) -

brew install nasmorapt install nasm - Emulator: QEMU for x86_64 -

brew install qemuorapt install qemu-system-x86 - Hex Editor:

hexdump,xxd, or GUI tool like HxD (Windows), Hex Fiend (macOS) - Text Editor: VS Code, Vim, Emacs with assembly syntax highlighting

Recommended Tools:

- Debugger: GDB with QEMU integration for step-by-step debugging

- Make: GNU Make for build automation

- Disk Image Tools:

dd,fdisk,partedfor creating bootable images - Cross-Compiler (for later projects): GCC cross-compiler for bare-metal targets

Optional But Helpful:

- Real Hardware: Old laptop or USB drive for testing (Projects 1-6 work in QEMU)

- Logic Analyzer: For ARM projects (Projects 9-10)

- JTAG Debugger: For serious ARM bare-metal debugging

Time Investment

Realistic estimates per project:

- Beginner Projects (1-2, 7, 11): 6-12 hours each (one weekend)

- Intermediate Projects (3-6, 8, 12-14): 12-24 hours each (two weekends)

- Advanced Projects (9-10, 15-17): 24-48 hours each (one month part-time)

- Total Journey: 3-6 months working 5-10 hours per week

Don’t rush. Each project builds a mental model. Taking time to experiment, break things, and understand why is more valuable than completing projects quickly.

Important Reality Check

This is hard. Bootloader development involves:

- No safety nets: One wrong memory access crashes the entire system

- Minimal debugging: No printf, no stack traces, just a frozen screen

- Hardware quirks: Real hardware has undocumented behaviors

- Ancient conventions: You’ll encounter 40-year-old design decisions

But it’s incredibly rewarding. You’ll understand computers at a level most programmers never reach. You’ll be able to:

- Debug boot failures on any system

- Understand security vulnerabilities at the firmware level

- Write embedded systems code with confidence

- Speak intelligently about system architecture in interviews

Expect to get stuck. That’s normal. Use the hints, read the references, and experiment. Every error teaches you something about how computers actually work.

Why Bootloaders Matter: The First Code That Runs

When you press the power button, something magical happens. Within nanoseconds, electricity flows, the CPU awakens at a hardcoded address, and a chain of software begins executing—each link trusting the previous one. This chain is the boot process, and the bootloader is your first opportunity to take control.

The Hidden Complexity Everyone Ignores

Most programmers never think about booting. They press power, wait a few seconds, and their OS appears. But consider:

- Every security vulnerability at boot level is catastrophic: Rootkits, bootkits, and firmware malware can hide from all OS-level security

- Cloud computing runs on this: Every EC2 instance, every container host boots—understanding this is understanding infrastructure

- Embedded systems are everywhere: Your car’s ECU, your router, your smart TV—all boot through code someone wrote

- Recovery depends on it: When Windows won’t start, understanding boot is the difference between fixing it and reinstalling

The boot process is the root of trust for the entire system. Understand it, and you understand computing at its most fundamental level.

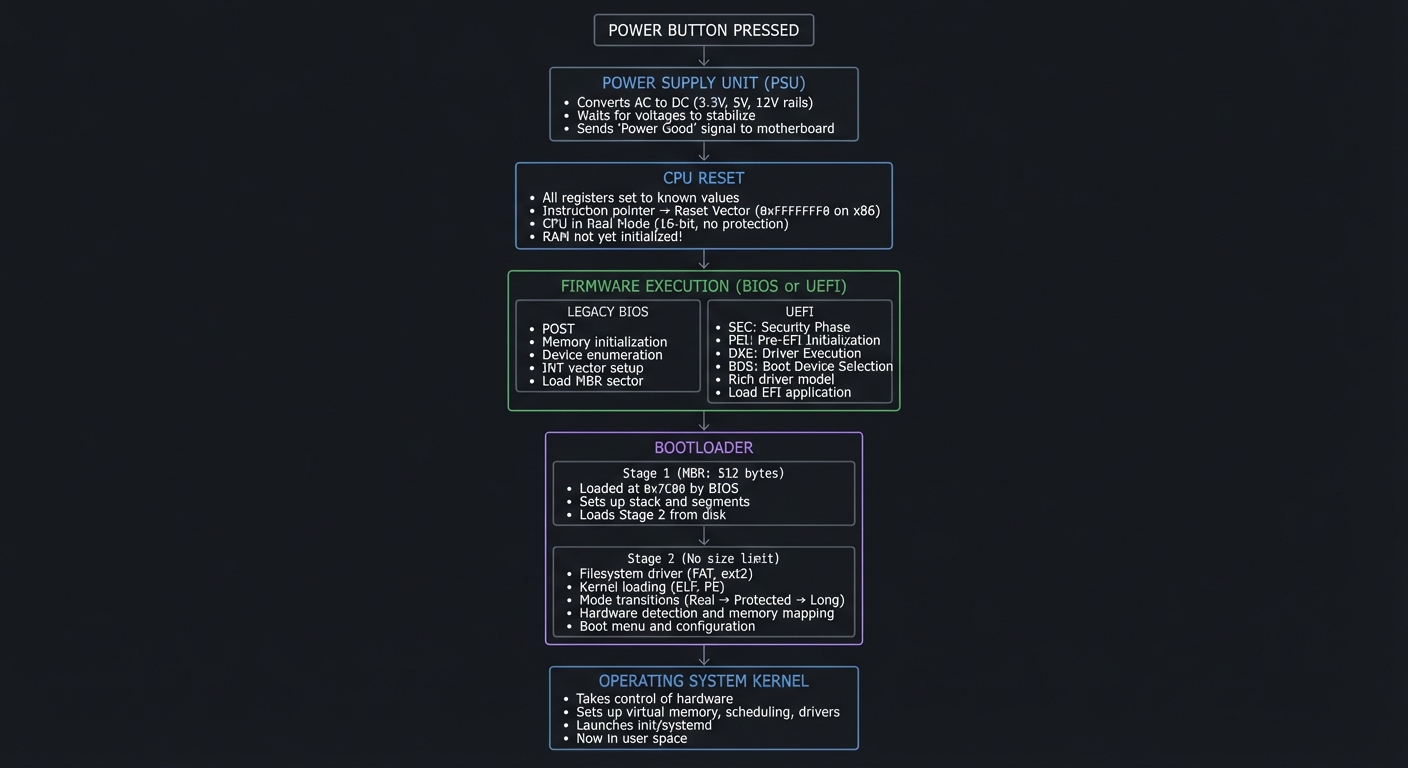

The Complete Boot Sequence Visualized

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ POWER BUTTON PRESSED │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ POWER SUPPLY UNIT (PSU) │

│ • Converts AC to DC (3.3V, 5V, 12V rails) │

│ • Waits for voltages to stabilize │

│ • Sends "Power Good" signal to motherboard │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ CPU RESET │

│ • All registers set to known values │

│ • Instruction pointer → Reset Vector (0xFFFFFFF0 on x86) │

│ • CPU in Real Mode (16-bit, no protection) │

│ • RAM not yet initialized! │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ FIRMWARE EXECUTION (BIOS or UEFI) │

│ │

│ ┌────────────────────────┐ ┌────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ LEGACY BIOS │ │ UEFI │ │

│ ├────────────────────────┤ ├────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ • POST (Power-On Self │ │ • SEC: Security Phase │ │

│ │ Test) │ │ • PEI: Pre-EFI Initialization │ │

│ │ • Memory initialization│ │ • DXE: Driver Execution │ │

│ │ • Device enumeration │ │ • BDS: Boot Device Selection │ │

│ │ • INT vector setup │ │ • Rich driver model │ │

│ │ • Load MBR sector │ │ • Load EFI application │ │

│ └────────────────────────┘ └────────────────────────────────────┘ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ BOOTLOADER │

│ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Stage 1 (MBR: 512 bytes) │ │

│ │ • Loaded at 0x7C00 by BIOS │ │

│ │ • Sets up stack and segments │ │

│ │ • Loads Stage 2 from disk │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Stage 2 (No size limit) │ │

│ │ • Filesystem driver (FAT, ext2, etc.) │ │

│ │ • Kernel loading and parsing (ELF, PE) │ │

│ │ • Mode transitions (Real → Protected → Long) │ │

│ │ • Hardware detection and memory mapping │ │

│ │ • Boot menu and configuration │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ OPERATING SYSTEM KERNEL │

│ • Takes control of hardware │

│ • Sets up virtual memory, scheduling, drivers │

│ • Launches init/systemd │

│ • You're now in user space │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

x86 CPU Modes: The Journey Through Privilege

Understanding CPU modes is fundamental to bootloader development. The x86 architecture has evolved through multiple modes, each with different capabilities and restrictions.

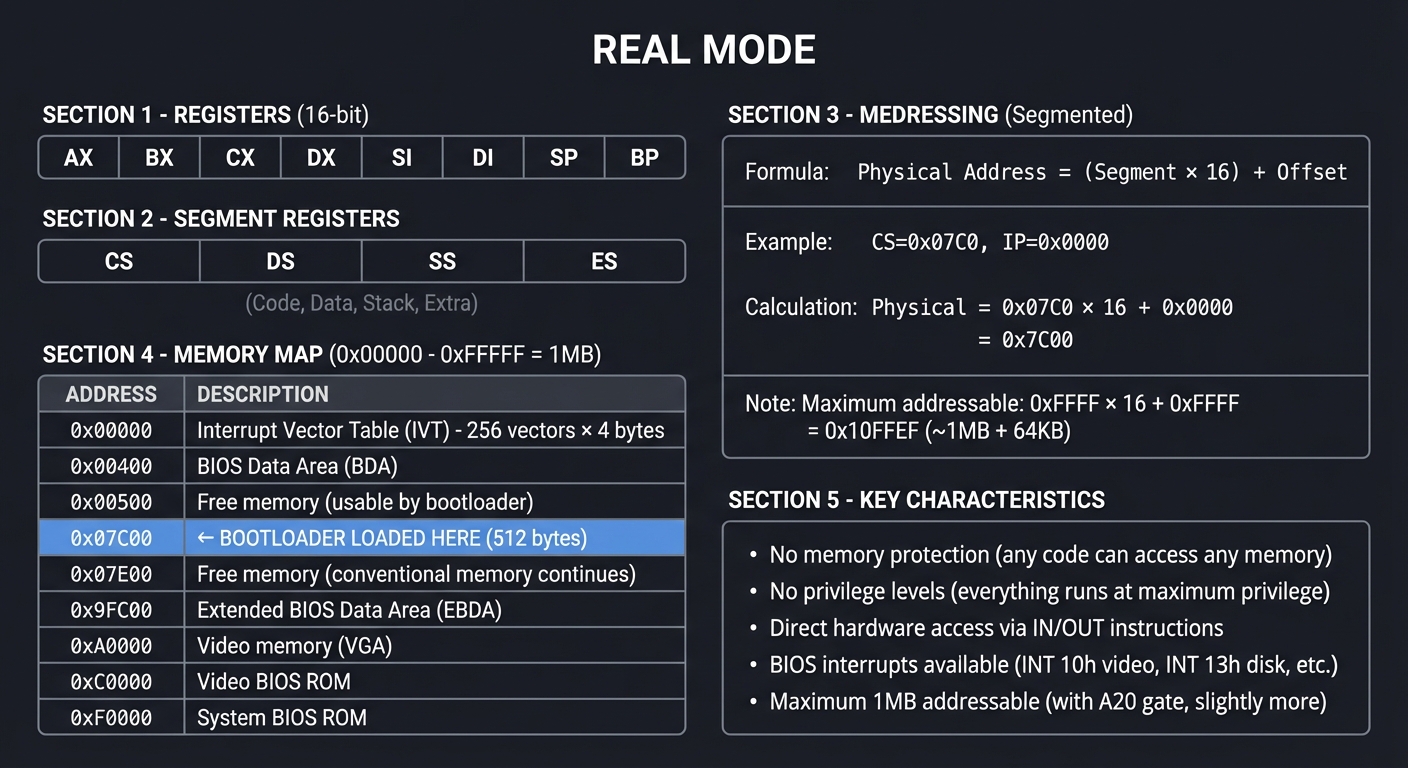

Real Mode (16-bit): Where It All Begins

When an x86 CPU powers on, it awakens in Real Mode—a compatibility mode that behaves like the original 8086 from 1978.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ REAL MODE │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ REGISTERS (16-bit): │

│ ┌──────┐ ┌──────┐ ┌──────┐ ┌──────┐ ┌──────┐ ┌──────┐ ┌──────┐ ┌──────┐ │

│ │ AX │ │ BX │ │ CX │ │ DX │ │ SI │ │ DI │ │ SP │ │ BP │ │

│ └──────┘ └──────┘ └──────┘ └──────┘ └──────┘ └──────┘ └──────┘ └──────┘ │

│ │

│ SEGMENT REGISTERS: │

│ ┌──────┐ ┌──────┐ ┌──────┐ ┌──────┐ │

│ │ CS │ │ DS │ │ SS │ │ ES │ (Code, Data, Stack, Extra) │

│ └──────┘ └──────┘ └──────┘ └──────┘ │

│ │

│ MEMORY ADDRESSING (Segmented): │

│ ┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Physical Address = (Segment × 16) + Offset │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Example: CS=0x07C0, IP=0x0000 │ │

│ │ Physical = 0x07C0 × 16 + 0x0000 = 0x7C00 │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Maximum addressable: 0xFFFF × 16 + 0xFFFF = 0x10FFEF (~1MB + 64KB) │ │

│ └────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ MEMORY MAP (0x00000 - 0xFFFFF = 1MB): │

│ ┌─────────────┬────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ 0x00000 │ Interrupt Vector Table (IVT) - 256 vectors × 4 bytes │ │

│ ├─────────────┼────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ 0x00400 │ BIOS Data Area (BDA) │ │

│ ├─────────────┼────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ 0x00500 │ Free memory (usable by bootloader) │ │

│ ├─────────────┼────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ 0x07C00 │ ← BOOTLOADER LOADED HERE (512 bytes) │ │

│ ├─────────────┼────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ 0x07E00 │ Free memory (conventional memory continues) │ │

│ ├─────────────┼────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ 0x9FC00 │ Extended BIOS Data Area (EBDA) │ │

│ ├─────────────┼────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ 0xA0000 │ Video memory (VGA) │ │

│ ├─────────────┼────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ 0xC0000 │ Video BIOS ROM │ │

│ ├─────────────┼────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ 0xF0000 │ System BIOS ROM │ │

│ └─────────────┴────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ KEY CHARACTERISTICS: │

│ • No memory protection (any code can access any memory) │

│ • No privilege levels (everything runs at maximum privilege) │

│ • Direct hardware access via IN/OUT instructions │

│ • BIOS interrupts available (INT 10h video, INT 13h disk, etc.) │

│ • Maximum 1MB addressable (with A20 gate, slightly more) │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

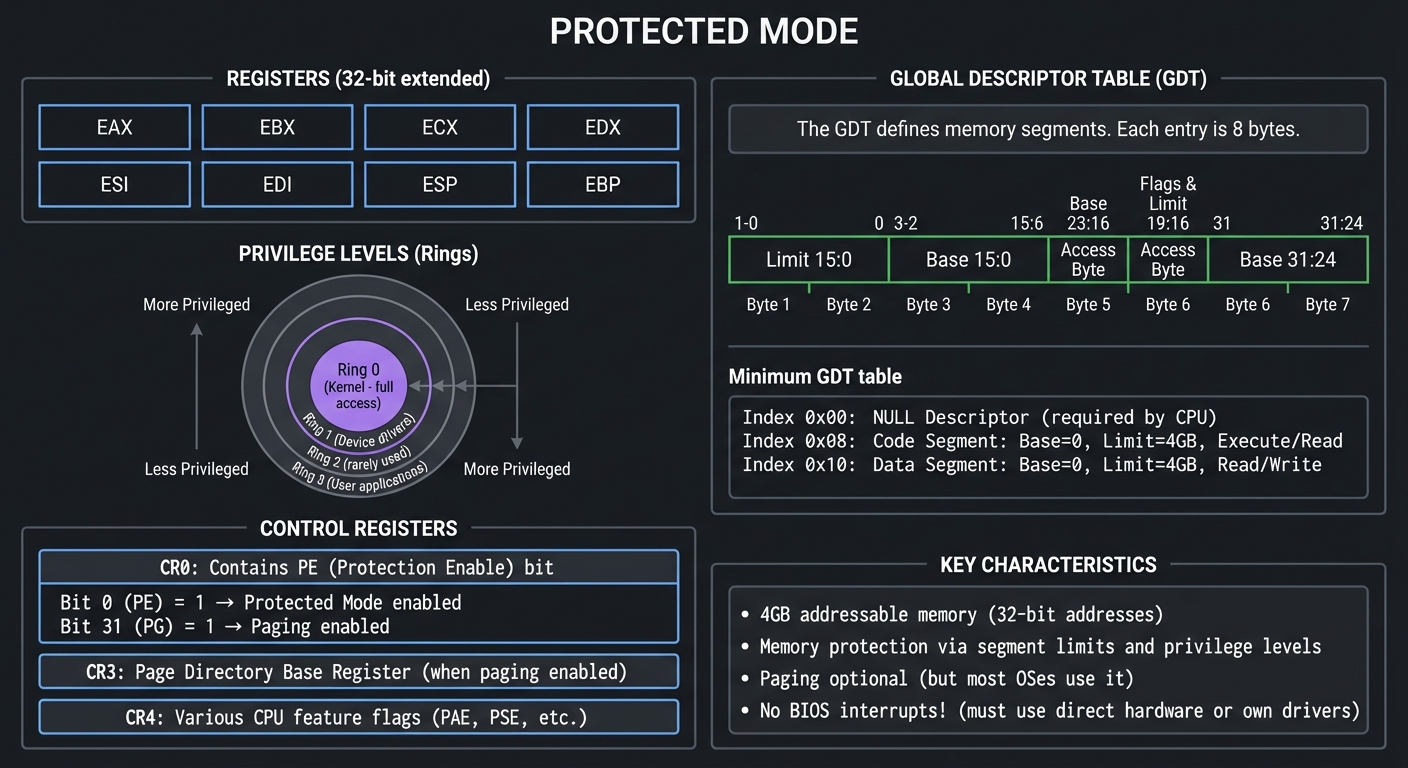

Protected Mode (32-bit): The Modern Operating Mode

Protected Mode was introduced with the 80286 (1982) and fully realized in the 80386 (1985). It provides memory protection, privilege levels, and access to more memory.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ PROTECTED MODE │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ REGISTERS (32-bit extended): │

│ ┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐ │

│ │ EAX │ │ EBX │ │ ECX │ │ EDX │ │

│ └──────────┘ └──────────┘ └──────────┘ └──────────┘ │

│ ┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐ │

│ │ ESI │ │ EDI │ │ ESP │ │ EBP │ │

│ └──────────┘ └──────────┘ └──────────┘ └──────────┘ │

│ │

│ GLOBAL DESCRIPTOR TABLE (GDT): │

│ ┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ The GDT defines memory segments. Each entry is 8 bytes: │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ ┌───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ Byte 7 │ Byte 6 │ Byte 5 │ Byte 4 │ Bytes 3-2 │ Bytes 1-0│ │ │

│ │ ├─────────┼─────────┼─────────┼─────────┼───────────┼──────────┤ │ │

│ │ │ Base │ Flags & │ Access │ Base │ Base │ Limit │ │ │

│ │ │ 31:24 │ Limit │ Byte │ 23:16 │ 15:0 │ 15:0 │ │ │

│ │ │ │ 19:16 │ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ └─────────┴─────────┴─────────┴─────────┴───────────┴──────────┘ │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Minimum GDT for Protected Mode: │ │

│ │ ┌────────┬────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ Index │ Descriptor │ │ │

│ │ ├────────┼────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │ │

│ │ │ 0x00 │ NULL Descriptor (required by CPU) │ │ │

│ │ │ 0x08 │ Code Segment: Base=0, Limit=4GB, Execute/Read │ │ │

│ │ │ 0x10 │ Data Segment: Base=0, Limit=4GB, Read/Write │ │ │

│ │ └────────┴────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │ │

│ └────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ PRIVILEGE LEVELS (Rings): │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ ┌─────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ Ring 0 │ ← Kernel (full access) │ │

│ │ ┌────┴─────────────┴────┐ │ │

│ │ │ Ring 1 │ ← Device drivers │ │

│ │ ┌────┴───────────────────────┴────┐ │ │

│ │ │ Ring 2 │ ← (rarely used) │ │

│ │ ┌────┴─────────────────────────────────┴────┐ │ │

│ │ │ Ring 3 │ ← User apps │ │

│ │ └───────────────────────────────────────────┘ │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ CONTROL REGISTERS: │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ CR0: Contains PE (Protection Enable) bit │ │

│ │ Bit 0 (PE) = 1 → Protected Mode enabled │ │

│ │ Bit 31 (PG) = 1 → Paging enabled │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ CR3: Page Directory Base Register (when paging enabled) │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ CR4: Various CPU feature flags (PAE, PSE, etc.) │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ KEY CHARACTERISTICS: │

│ • 4GB addressable memory (32-bit addresses) │

│ • Memory protection via segment limits and privilege levels │

│ • Paging optional (but most OSes use it) │

│ • No BIOS interrupts! (must use direct hardware or own drivers) │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

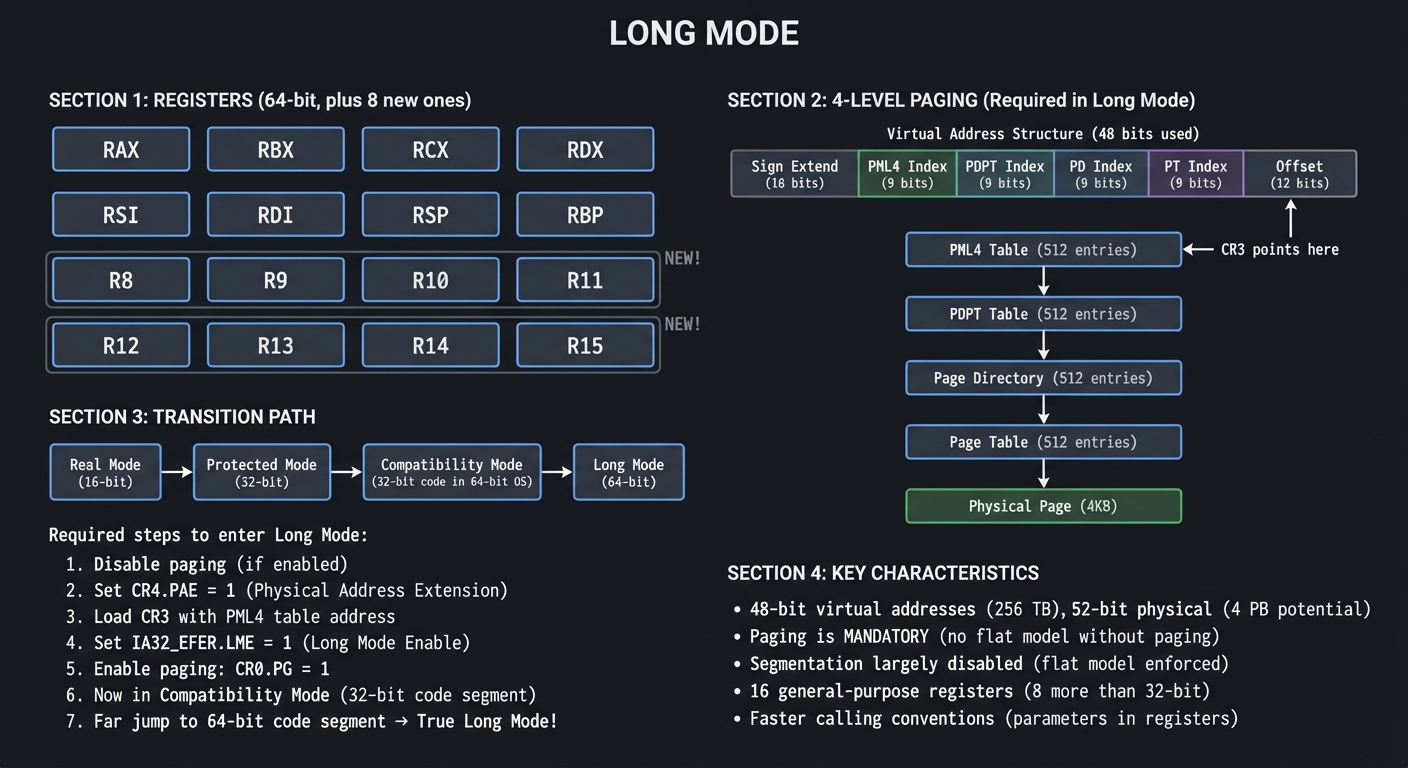

Long Mode (64-bit): The Modern 64-bit Mode

Long Mode, introduced with AMD64/x86-64, provides 64-bit operation and vastly larger address spaces.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ LONG MODE │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ REGISTERS (64-bit, plus 8 new ones): │

│ ┌────────────┐ ┌────────────┐ ┌────────────┐ ┌────────────┐ │

│ │ RAX │ │ RBX │ │ RCX │ │ RDX │ │

│ └────────────┘ └────────────┘ └────────────┘ └────────────┘ │

│ ┌────────────┐ ┌────────────┐ ┌────────────┐ ┌────────────┐ │

│ │ RSI │ │ RDI │ │ RSP │ │ RBP │ │

│ └────────────┘ └────────────┘ └────────────┘ └────────────┘ │

│ ┌────────────┐ ┌────────────┐ ┌────────────┐ ┌────────────┐ │

│ │ R8 │ │ R9 │ │ R10 │ │ R11 │ ← NEW! │

│ └────────────┘ └────────────┘ └────────────┘ └────────────┘ │

│ ┌────────────┐ ┌────────────┐ ┌────────────┐ ┌────────────┐ │

│ │ R12 │ │ R13 │ │ R14 │ │ R15 │ ← NEW! │

│ └────────────┘ └────────────┘ └────────────┘ └────────────┘ │

│ │

│ 4-LEVEL PAGING (Required in Long Mode): │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Virtual Address (48 bits used): │ │

│ │ ┌────────┬─────────┬─────────┬─────────┬─────────┬──────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ Sign │ PML4 │ PDPT │ PD │ PT │ Offset │ │ │

│ │ │ Extend │ Index │ Index │ Index │ Index │ (12 bits) │ │ │

│ │ │(16 bit)│ (9 bit) │ (9 bit) │ (9 bit) │ (9 bit) │ │ │ │

│ │ └────────┴────┬────┴────┬────┴────┬────┴────┬────┴──────────────┘ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ ▼ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ ┌─────────────────┐ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ │ PML4 Table │ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ │ (512 entries) │────┘ │ │ │ │

│ │ │ CR3 points here │ │ │ │ │

│ │ └───────┬─────────┘ │ │ │ │

│ │ │ ▼ │ │ │

│ │ │ ┌─────────────────┐ │ │ │

│ │ └────────→│ PDPT Table │ │ │ │

│ │ │ (512 entries) │──────┘ │ │

│ │ └───────┬─────────┘ │ │

│ │ │ ▼ │ │

│ │ │ ┌─────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ └─→│ Page Directory │ │ │

│ │ │ (512 entries) │─────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ └───────┬─────────┘ │ │ │

│ │ │ ▼ │ │

│ │ │ ┌─────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ └───────→│ Page Table │ │ │

│ │ │ (512 entries) │ │ │

│ │ └───────┬─────────┘ │ │

│ │ │ │ │

│ │ ▼ │ │

│ │ Physical Page (4KB) │ │

│ │ │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ TRANSITION PATH: │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Real Mode ──┬──→ Protected Mode ──→ Compatibility Mode ──→ Long Mode │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ (16-bit) │ (32-bit) (32-bit code in (64-bit) │ │

│ │ │ 64-bit OS) │ │

│ │ │ │ │

│ │ Required steps to enter Long Mode: │ │

│ │ 1. Disable paging (if enabled) │ │

│ │ 2. Set CR4.PAE = 1 (Physical Address Extension) │ │

│ │ 3. Load CR3 with PML4 table address │ │

│ │ 4. Set IA32_EFER.LME = 1 (Long Mode Enable) │ │

│ │ 5. Enable paging: CR0.PG = 1 │ │

│ │ 6. Now in Compatibility Mode (32-bit code segment) │ │

│ │ 7. Far jump to 64-bit code segment → True Long Mode! │ │

│ │ │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ KEY CHARACTERISTICS: │

│ • 48-bit virtual addresses (256 TB), 52-bit physical (4 PB potential) │

│ • Paging is MANDATORY (no flat model without paging) │

│ • Segmentation largely disabled (flat model enforced) │

│ • 16 general-purpose registers (8 more than 32-bit) │

│ • Faster calling conventions (parameters in registers) │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

BIOS vs UEFI: Two Different Worlds

Legacy BIOS: The Original Way

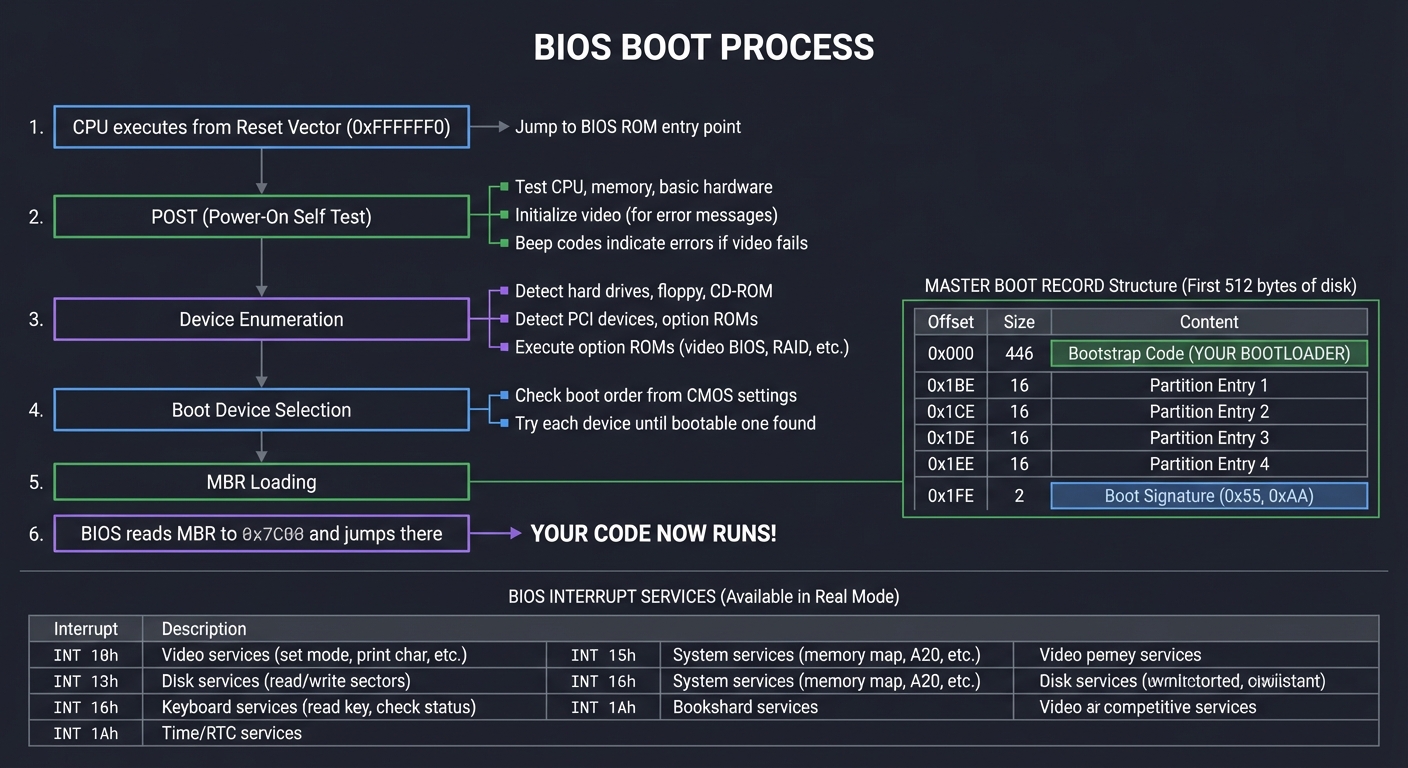

BIOS (Basic Input/Output System) dates back to the original IBM PC (1981). It’s simple, limited, but well-understood.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ BIOS BOOT PROCESS │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ 1. CPU executes from Reset Vector (0xFFFFFFF0) │

│ └─→ Jump to BIOS ROM entry point │

│ │

│ 2. POST (Power-On Self Test) │

│ ├─→ Test CPU, memory, basic hardware │

│ ├─→ Initialize video (for error messages) │

│ └─→ Beep codes indicate errors if video fails │

│ │

│ 3. Device Enumeration │

│ ├─→ Detect hard drives, floppy, CD-ROM │

│ ├─→ Detect PCI devices, option ROMs │

│ └─→ Execute option ROMs (video BIOS, RAID, etc.) │

│ │

│ 4. Boot Device Selection │

│ ├─→ Check boot order from CMOS settings │

│ └─→ Try each device until bootable one found │

│ │

│ 5. MBR Loading │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ MASTER BOOT RECORD │ │

│ │ (First 512 bytes of disk) │ │

│ ├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ Offset │ Size │ Content │ │

│ ├────────┼───────┼─────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ 0x000 │ 446 │ Bootstrap Code (YOUR BOOTLOADER) │ │

│ │ 0x1BE │ 16 │ Partition Entry 1 │ │

│ │ 0x1CE │ 16 │ Partition Entry 2 │ │

│ │ 0x1DE │ 16 │ Partition Entry 3 │ │

│ │ 0x1EE │ 16 │ Partition Entry 4 │ │

│ │ 0x1FE │ 2 │ Boot Signature (0x55, 0xAA) │ │

│ └────────┴───────┴─────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ 6. BIOS reads MBR to 0x7C00 and jumps there │

│ └─→ YOUR CODE NOW RUNS! │

│ │

│ BIOS INTERRUPT SERVICES (Available in Real Mode): │

│ ┌──────────┬───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ INT 10h │ Video services (set mode, print char, etc.) │ │

│ │ INT 13h │ Disk services (read/write sectors) │ │

│ │ INT 15h │ System services (memory map, A20, etc.) │ │

│ │ INT 16h │ Keyboard services (read key, check status) │ │

│ │ INT 1Ah │ Time/RTC services │ │

│ └──────────┴───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

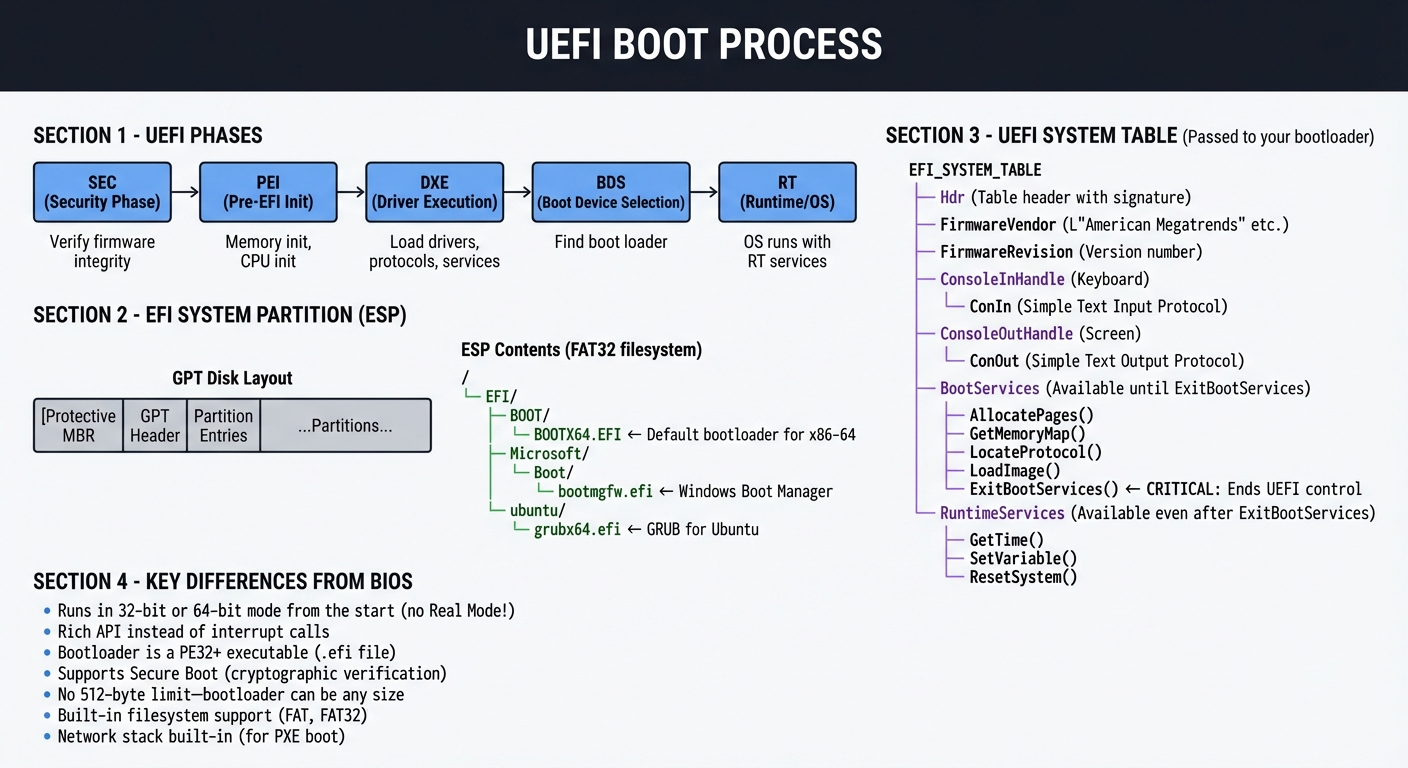

UEFI: The Modern Standard

UEFI (Unified Extensible Firmware Interface) replaces BIOS with a modern, extensible architecture.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ UEFI BOOT PROCESS │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ UEFI PHASES: │

│ ┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ ┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐ ┌───────┐ │ │

│ │ │ SEC │───→│ PEI │───→│ DXE │───→│ BDS │───→│ RT │ │ │

│ │ │Security │ │Pre-EFI │ │ Driver │ │ Boot │ │Runtime│ │ │

│ │ │ Phase │ │ Init │ │Execution│ │ Device │ │ (OS) │ │ │

│ │ └─────────┘ └─────────┘ └─────────┘ │Selection│ └───────┘ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ └─────────┘ │ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ Verify Memory init Load drivers Find boot OS runs │ │

│ │ firmware CPU init protocols loader with RT │ │

│ │ integrity services services │ │

│ │ │ │

│ └────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ EFI SYSTEM PARTITION (ESP): │

│ ┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ GPT Disk Layout: │ │

│ │ ┌───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ Protective MBR │ GPT Header │ Partition Entries │ ...Partitions... │ │ │

│ │ └───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ ESP Contents (FAT32 filesystem): │ │

│ │ / │ │

│ │ └── EFI/ │ │

│ │ ├── BOOT/ │ │

│ │ │ └── BOOTX64.EFI ← Default bootloader for x86-64 │ │

│ │ ├── Microsoft/ │ │

│ │ │ └── Boot/ │ │

│ │ │ └── bootmgfw.efi ← Windows Boot Manager │ │

│ │ └── ubuntu/ │ │

│ │ └── grubx64.efi ← GRUB for Ubuntu │ │

│ │ │ │

│ └────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ UEFI SYSTEM TABLE (Passed to your bootloader): │

│ ┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ EFI_SYSTEM_TABLE │ │

│ │ ├── Hdr (Table header with signature) │ │

│ │ ├── FirmwareVendor (L"American Megatrends" etc.) │ │

│ │ ├── FirmwareRevision (Version number) │ │

│ │ ├── ConsoleInHandle (Keyboard) │ │

│ │ ├── ConIn (Simple Text Input Protocol) │ │

│ │ ├── ConsoleOutHandle (Screen) │ │

│ │ ├── ConOut (Simple Text Output Protocol) │ │

│ │ ├── BootServices (Available until ExitBootServices) │ │

│ │ │ ├── AllocatePages() │ │

│ │ │ ├── GetMemoryMap() │ │

│ │ │ ├── LocateProtocol() │ │

│ │ │ ├── LoadImage() │ │

│ │ │ └── ExitBootServices() ← CRITICAL: Ends UEFI control │ │

│ │ └── RuntimeServices (Available even after ExitBootServices) │ │

│ │ ├── GetTime() │ │

│ │ ├── SetVariable() │ │

│ │ └── ResetSystem() │ │

│ │ │ │

│ └────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ KEY DIFFERENCES FROM BIOS: │

│ • Runs in 32-bit or 64-bit mode from the start (no Real Mode!) │

│ • Rich API instead of interrupt calls │

│ • Bootloader is a PE32+ executable (.efi file) │

│ • Supports Secure Boot (cryptographic verification) │

│ • No 512-byte limit—bootloader can be any size │

│ • Built-in filesystem support (FAT, FAT32) │

│ • Network stack built-in (for PXE boot) │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

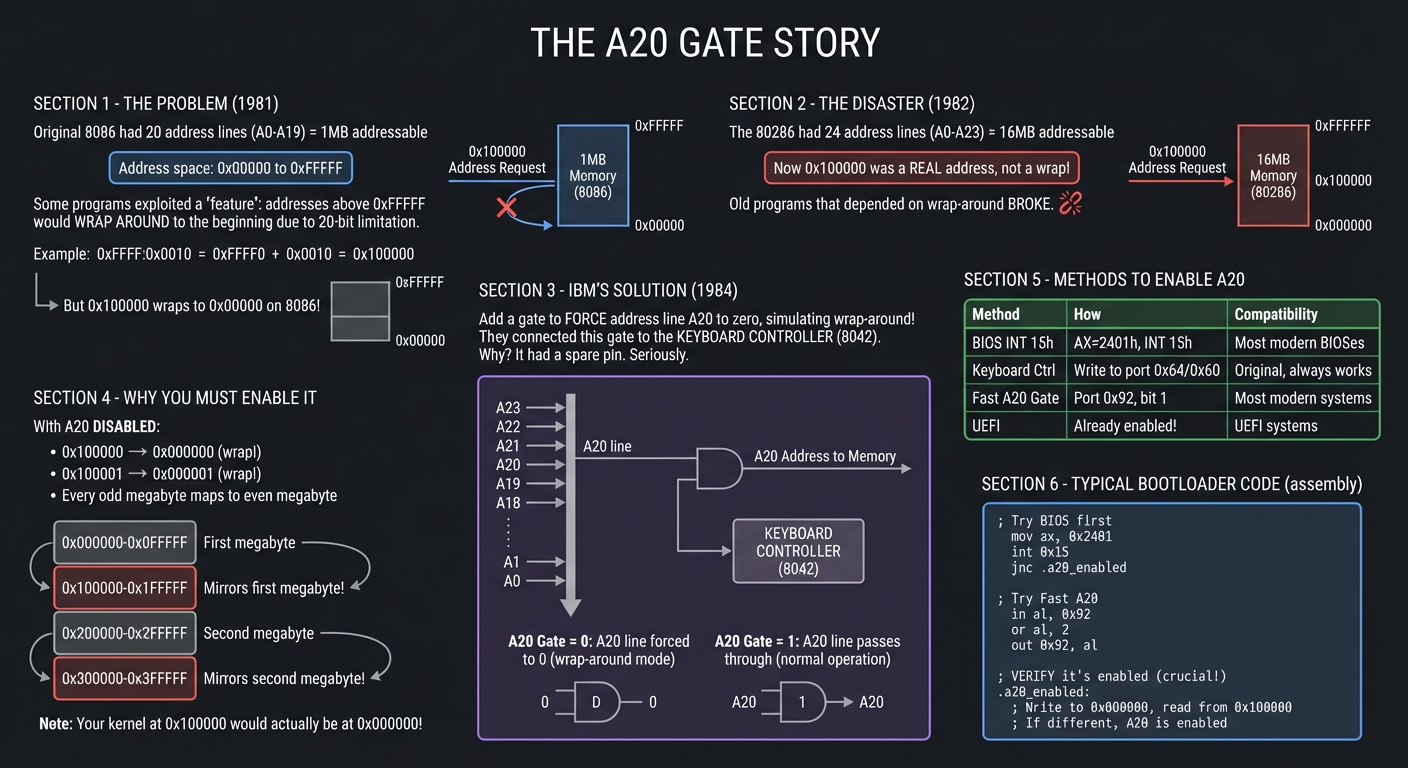

The A20 Gate: A Historical Absurdity You Must Handle

One of the most bizarre aspects of x86 boot programming is the A20 line. Understanding why it exists helps you appreciate x86’s backwards-compatibility obsession.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ THE A20 GATE STORY │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ THE PROBLEM (1981): │

│ The original 8086 had 20 address lines (A0-A19) = 1MB addressable │

│ │

│ Address space: 0x00000 to 0xFFFFF │

│ │

│ Some programs exploited a "feature": addresses above 0xFFFFF would │

│ WRAP AROUND to the beginning due to 20-bit limitation. │

│ │

│ Example: 0xFFFF:0x0010 = 0xFFFF0 + 0x0010 = 0x100000 │

│ But 0x100000 wraps to 0x00000 on 8086! │

│ │

│ ──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ THE DISASTER (1982): │

│ The 80286 had 24 address lines (A0-A23) = 16MB addressable │

│ Now 0x100000 was a REAL address, not a wrap! │

│ │

│ Old programs that depended on wrap-around BROKE. │

│ │

│ ──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ IBM'S "SOLUTION" (1984): │

│ Add a gate to FORCE address line A20 to zero, simulating wrap-around! │

│ │

│ They connected this gate to... the KEYBOARD CONTROLLER (8042). │

│ Why? It had a spare pin. Seriously. │

│ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Address Lines: A23 A22 A21 A20 A19 A18 ... A1 A0 │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ └─── A20 Gate ─── Keyboard Controller│ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ ┌───┴───┐ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ AND │ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ Gate │ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ └───┬───┘ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ ▼ │ │

│ │ │ │ └────────► Memory │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ A20 Gate = 0: A20 line forced to 0 (wrap-around mode) │ │

│ │ A20 Gate = 1: A20 line passes through (normal operation) │ │

│ │ │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ WHY YOU MUST ENABLE IT: │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ With A20 DISABLED: │ │

│ │ • 0x100000 → 0x000000 (wrap!) │ │

│ │ • 0x100001 → 0x000001 (wrap!) │ │

│ │ • Every odd megabyte maps to even megabyte │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Memory appears like this: │ │

│ │ 0x000000 ─┬─ First megabyte │ │

│ │ 0x0FFFFF ─┘ │ │

│ │ 0x100000 ─┬─ Mirrors first megabyte! │ │

│ │ 0x1FFFFF ─┘ │ │

│ │ 0x200000 ─┬─ Second megabyte │ │

│ │ 0x2FFFFF ─┘ │ │

│ │ 0x300000 ─┬─ Mirrors second megabyte! │ │

│ │ ... │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Your kernel at 0x100000 would actually be at 0x000000! │ │

│ │ │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ METHODS TO ENABLE A20: │

│ ┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Method │ How │ Compatibility │ │

│ ├────────────────┼────────────────────────────┼──────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ BIOS INT 15h │ AX=2401h, INT 15h │ Most modern BIOSes │ │

│ │ Keyboard Ctrl │ Write to port 0x64/0x60 │ Original, always works │ │

│ │ Fast A20 Gate │ Port 0x92, bit 1 │ Most modern systems │ │

│ │ UEFI │ Already enabled! │ UEFI systems │ │

│ └────────────────┴────────────────────────────┴──────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ TYPICAL BOOTLOADER CODE: │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ ; Try BIOS first │ │

│ │ mov ax, 0x2401 │ │

│ │ int 0x15 │ │

│ │ jnc .a20_enabled │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ ; Try Fast A20 │ │

│ │ in al, 0x92 │ │

│ │ or al, 2 │ │

│ │ out 0x92, al │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ ; Try keyboard controller (complex, but always works) │ │

│ │ ; ... wait for 8042, write command, etc. │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ ; VERIFY it's enabled (crucial!) │ │

│ │ .a20_enabled: │ │

│ │ ; Write to 0x000000, read from 0x100000 │ │

│ │ ; If different, A20 is enabled │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

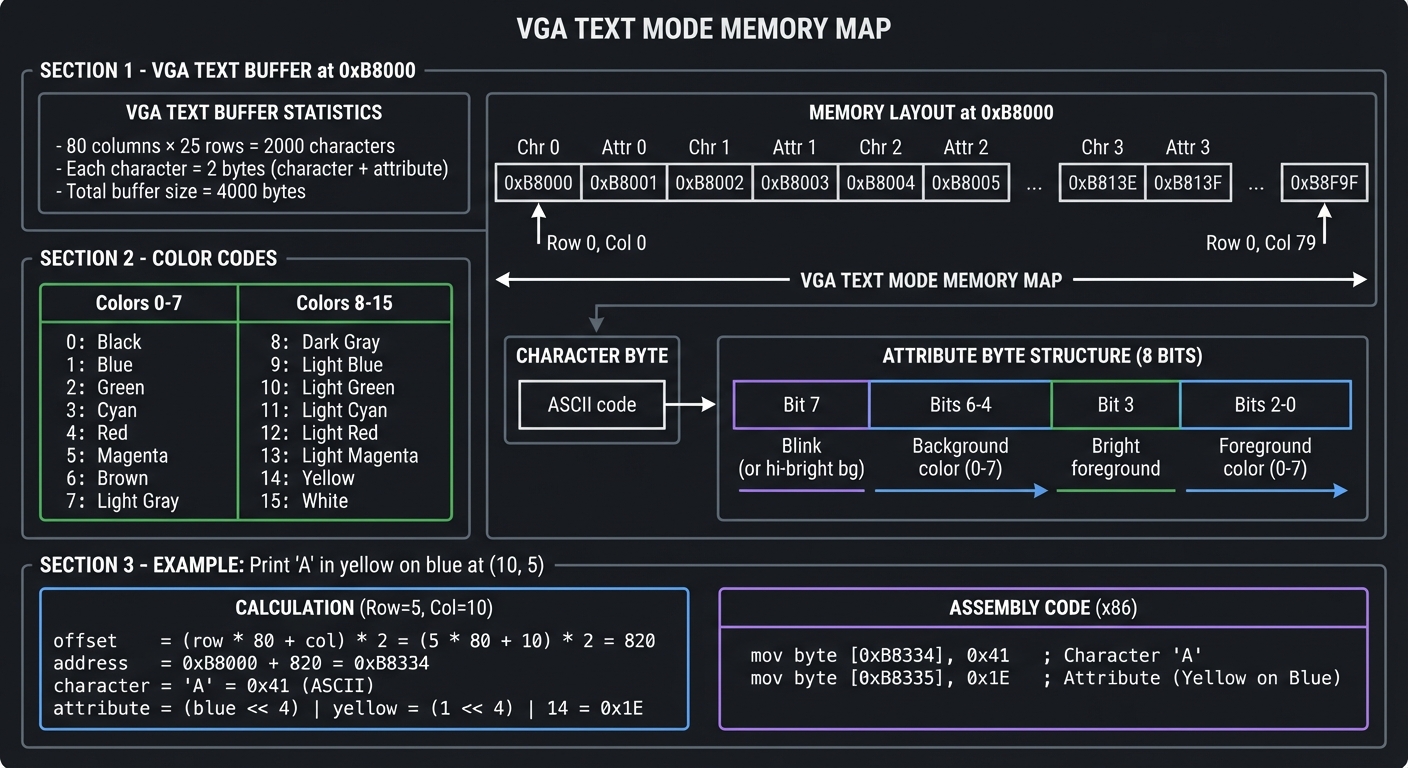

Memory-Mapped I/O and VGA

Once in Protected Mode, BIOS interrupts no longer work. You must access hardware directly. VGA text mode is the classic example.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ VGA TEXT MODE MEMORY MAP │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ VGA TEXT BUFFER at 0xB8000: │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ 80 columns × 25 rows = 2000 characters │ │

│ │ Each character = 2 bytes (character + attribute) │ │

│ │ Total buffer size = 4000 bytes │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Memory layout: │ │

│ │ 0xB8000 ┌────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬─...─┐ │ │

│ │ │Chr │Attr│Chr │Attr│Chr │Attr│Chr │Attr│ │ │ │

│ │ │ 0 │ 0 │ 1 │ 1 │ 2 │ 2 │ 3 │ 3 │ │ │ │

│ │ └────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴─...─┘ │ │

│ │ Row 0, Col 0 ─────────────────────────► Row 0, Col 79 │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Character byte: ASCII code │ │

│ │ Attribute byte: │ │

│ │ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ Bit 7 │ Bits 6-4 │ Bit 3 │ Bits 2-0 │ │ │

│ │ ├─────────┼───────────────┼─────────┼────────────────────┤ │ │

│ │ │ Blink │ Background │ Bright │ Foreground │ │ │

│ │ │ (or hi- │ color (0-7) │ fore- │ color (0-7) │ │ │

│ │ │ bright │ │ ground │ │ │ │

│ │ │ bg) │ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ └─────────┴───────────────┴─────────┴────────────────────┘ │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ COLOR CODES: │ │

│ │ ┌────┬─────────────┬────┬──────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ 0 │ Black │ 8 │ Dark Gray │ │ │

│ │ │ 1 │ Blue │ 9 │ Light Blue │ │ │

│ │ │ 2 │ Green │ 10 │ Light Green │ │ │

│ │ │ 3 │ Cyan │ 11 │ Light Cyan │ │ │

│ │ │ 4 │ Red │ 12 │ Light Red │ │ │

│ │ │ 5 │ Magenta │ 13 │ Light Magenta │ │ │

│ │ │ 6 │ Brown │ 14 │ Yellow │ │ │

│ │ │ 7 │ Light Gray │ 15 │ White │ │ │

│ │ └────┴─────────────┴────┴──────────────────┘ │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ EXAMPLE: Print 'A' in yellow on blue at (10, 5) │ │

│ │ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ offset = (row * 80 + col) * 2 = (5 * 80 + 10) * 2 = 820 │ │ │

│ │ │ address = 0xB8000 + 820 = 0xB8334 │ │ │

│ │ │ character = 'A' = 0x41 │ │ │

│ │ │ attribute = (blue << 4) | yellow = (1 << 4) | 14 = 0x1E │ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ │ mov byte [0xB8334], 0x41 ; Character │ │ │

│ │ │ mov byte [0xB8335], 0x1E ; Attribute │ │ │

│ │ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │ │

│ │ │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Concept Summary Table

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize |

|---|---|

| CPU Reset & Execution Start | When power is applied, the CPU begins at a hardcoded address (reset vector). All state is predictable at this moment. |

| Real Mode | 16-bit mode with 1MB limit, segment:offset addressing, no protection. BIOS services available via interrupts. |

| Protected Mode | 32-bit mode with memory protection via GDT, privilege rings, 4GB addressable. No BIOS interrupts. |

| Long Mode | 64-bit mode requiring paging. 4-level page tables, more registers, modern calling conventions. |

| GDT (Global Descriptor Table) | Defines memory segments with base, limit, and access rights. Required for Protected Mode. |

| Paging | Maps virtual addresses to physical addresses via multi-level page tables. Required for Long Mode. |

| A20 Gate | Historical hack that must be enabled to access memory above 1MB. Multiple enable methods exist. |

| BIOS vs UEFI | BIOS: legacy, Real Mode, interrupts, 512-byte MBR. UEFI: modern, PE executables, rich API, Secure Boot. |

| MBR Structure | First 512 bytes: 446 bytes code, 64 bytes partition table, 2 bytes signature (0xAA55). |

| Memory-Mapped I/O | Hardware registers accessed like memory. VGA at 0xB8000, device registers at fixed addresses. |

| Firmware Services | BIOS provides INT 10h/13h/15h etc. UEFI provides Boot Services and Runtime Services via pointers. |

| Chain Loading | One bootloader loading another. Essential for multi-OS systems. |

Deep Dive Reading by Concept

This section maps each bootloader concept to specific book chapters for deeper understanding.

CPU Modes and Mode Transitions

| Concept | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| x86 Real Mode fundamentals | Low-Level Programming by Igor Zhirkov | Ch. 3: “Assembly Language” |

| Protected Mode entry | Low-Level Programming by Igor Zhirkov | Ch. 4: “Virtual Memory” |

| Long Mode transition | Low-Level Programming by Igor Zhirkov | Ch. 5: “Compilation Pipeline” |

| x86 execution modes | Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective by Bryant & O’Hallaron | Ch. 3: “Machine-Level Representation” |

| CPU control registers | Intel SDM Volume 3 | Ch. 2: “System Architecture Overview” |

Memory and Segmentation

| Concept | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Segment:offset addressing | The Art of Assembly Language, 2nd Ed by Randall Hyde | Ch. 4: “Memory” |

| GDT structure and setup | Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces by Arpaci-Dusseau | Part II: “Virtualization” |

| Paging fundamentals | Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective by Bryant & O’Hallaron | Ch. 9: “Virtual Memory” |

| x86-64 4-level paging | Low-Level Programming by Igor Zhirkov | Ch. 5: “Compilation Pipeline” |

Firmware and Boot Process

| Concept | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| BIOS architecture | Beyond BIOS by Vincent Zimmer | Ch. 1-3: “BIOS Background” |

| UEFI fundamentals | Beyond BIOS by Vincent Zimmer | Ch. 4-7: “UEFI Architecture” |

| Boot sequence overview | Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces by Arpaci-Dusseau | Ch. 2: “Introduction” |

| Option ROMs and PCI | The Secret Life of Programs by Jonathan Steinhart | Ch. 9: “The Operating System” |

Disk and Filesystem Access

| Concept | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| MBR and disk layout | Practical Binary Analysis by Dennis Andriesse | Ch. 3: “The Binary Format” |

| INT 13h disk services | The Art of Assembly Language, 2nd Ed by Randall Hyde | Ch. 13: “BIOS and DOS Services” |

| FAT filesystem internals | Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces by Arpaci-Dusseau | Ch. 40: “File System Implementation” |

| GPT and modern partitioning | How Linux Works, 3rd Ed by Brian Ward | Ch. 4: “Disks and Filesystems” |

Low-Level Hardware Access

| Concept | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Memory-mapped I/O | Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Ed by Elecia White | Ch. 4: “Inputs and Outputs” |

| VGA programming | Write Great Code, Volume 2, 2nd Ed by Randall Hyde | Ch. 8: “Video Display Systems” |

| Serial port (UART) | Bare Metal C by Steve Oualline | Ch. 6: “Serial I/O” |

| Keyboard controller | The Art of Assembly Language, 2nd Ed by Randall Hyde | Ch. 13: “BIOS and DOS Services” |

Assembly and Bare Metal Programming

| Concept | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| x86 assembly fundamentals | The Art of 64-Bit Assembly, Volume 1 by Randall Hyde | Ch. 1-4: “Assembly Basics” |

| NASM syntax | Low-Level Programming by Igor Zhirkov | Ch. 3: “Assembly Language” |

| Bare metal C | Bare Metal C by Steve Oualline | Ch. 1-3: “Bare Metal Fundamentals” |

| Linker scripts | Low-Level Programming by Igor Zhirkov | Ch. 6: “Interrupts and System Calls” |

Platform-Specific Topics

| Concept | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| ARM boot process | Making Embedded Systems, 2nd Ed by Elecia White | Ch. 4: “Inputs and Outputs” |

| Raspberry Pi bare metal | Bare Metal C by Steve Oualline | Ch. 7-8: “Raspberry Pi” |

| U-Boot bootloader | Embedded Linux Primer by Christopher Hallinan | Ch. 7: “Bootloaders” |

| QEMU debugging | The Art of Debugging by Matloff & Salzman | Ch. 1-3: “GDB Basics” |

Quick Start: Your First 48 Hours

Feeling overwhelmed by the concepts? Here’s a focused path to get you booting code within two days.

Day 1: Setup and First Boot (4-6 hours)

Morning: Environment Setup (2 hours)

- Install NASM:

brew install nasm(macOS) orapt install nasm(Linux) - Install QEMU:

brew install qemuorapt install qemu-system-x86 - Test the tools:

nasm -version # Should show NASM version 2.14+ qemu-system-x86_64 --version # Should show QEMU version 6.0+ - Create a workspace directory:

mkdir bootloader-journey && cd bootloader-journey

Afternoon: Project 1 - Hello World Bootloader (2-4 hours)

- Jump straight to Project 1: “The 512-Byte Hello World Bootloader”

- Don’t worry about understanding everything—just follow the implementation hints

- Goal: See “Hello, Bare Metal!” on your screen

- When stuck: Read “The Core Question You’re Answering” section

Evening: Understanding What Happened (1-2 hours)

- Reread the “x86 CPU Modes” section (lines 195-420)

- Study the ASCII diagram of the boot sequence

- Answer these questions in a notebook:

- Where does the BIOS load my code? (Answer: 0x7C00)

- Why is my bootloader exactly 512 bytes? (Answer: MBR sector size)

- What does

INT 10hdo? (Answer: BIOS video service)

Day 2: Memory and Mode Switching (4-6 hours)

Morning: Project 2 - Memory Detective (2-3 hours)

- Complete Project 2: “Memory Map Detective”

- Goal: See the E820 memory map displayed

- Key learning: Not all memory addresses are usable RAM

Afternoon: Read Core Concepts (2 hours)

- Study “BIOS vs UEFI: Two Different Worlds” section

- Read “The A20 Gate: A Historical Absurdity You Must Handle”

- Skim the GDT explanation in Project 3’s prerequisites

Evening: Reflection (1 hour)

- Can you explain to someone (even a rubber duck) what happens when you press the power button?

- Do you understand why we need different CPU modes?

- If yes → Continue to Project 3 tomorrow

- If no → Reread “Why Bootloaders Matter” and the boot sequence diagram

Day 3 and Beyond: Choose Your Path

After the first 48 hours, you have options:

Path A: Sequential Deep Dive (Recommended for beginners)

- Continue Projects 1 → 2 → 3 → 4 → 5 → 6 in order

- Each project builds on the previous one

- Time: 2-3 months, 5-10 hours/week

Path B: UEFI Focus (For modern systems)

- Do Projects 1-2 for context

- Jump to Projects 7-8 (UEFI)

- Return to Projects 3-6 if you need x86 mode details

- Time: 1-2 months, 5-10 hours/week

Path C: ARM/Embedded Focus (For embedded engineers)

- Do Projects 1-2 for concepts

- Jump to Projects 9-10 (Raspberry Pi, U-Boot)

- Time: 1-2 months, 5-10 hours/week

When You Get Stuck (You Will!)

“My bootloader doesn’t boot—just a black screen”

- Check bytes 510-511 with

hexdump -C boot.bin | tail - Should show:

000001f0 ... 55 aa - If not, your padding or signature is wrong

“QEMU closes immediately”

- Missing

-drive format=raw,file=boot.binargument - Or use:

qemu-system-x86_64 -hda boot.bin

“I don’t understand assembly”

- Start with Projects 1-2 anyway

- Assembly makes more sense when you have a goal

- Use the “Hints in Layers” sections

- Reference “Low-Level Programming” Chapter 3 as you go

“This is too hard”

- You’re right. It is hard. This is systems programming.

- But thousands have learned this. You can too.

- Each error message teaches you how computers actually work.

- Use the thinking exercises before coding—they build intuition.

Success Markers

You’re making real progress when:

- ✓ You can boot custom code in QEMU without Googling commands

- ✓ You understand why the boot signature is 0xAA55 (little-endian)

- ✓ You can explain segment:offset addressing to someone

- ✓ You’re comfortable with hexadecimal and binary

- ✓ You know when to use assembly vs. C in bootloader code

Resources for the First Week

Essential reading (in order):

- “Low-Level Programming” by Igor Zhirkov - Chapter 1 (Memory basics)

- OSDev Wiki: Real Mode (15-minute read)

- OSDev Wiki: Babystep1 (Basic bootloader tutorial)

- Ralf Brown’s Interrupt List: INT 10h entries (reference, not full read)

Videos (optional but helpful):

- Search YouTube for “writing a bootloader from scratch”

- Look for videos that show real QEMU output

Community help:

- OSDev.org Forums: Beginner questions welcome

- r/osdev subreddit: Post screenshots of your errors

- Stack Overflow: Tag questions with [bootloader] and [x86]

Projects

Project 1: “The 512-Byte Hello World Bootloader”

| Attribute | Value |

|---|---|

| Language | x86 Assembly (NASM) (alt: FASM, GAS (AT&T syntax), MASM) |

| Difficulty | Intermediate |

| Time | Weekend |

| Coolness | ★★★★☆ Hardcore |

| Portfolio Value | Resume Gold |

What you’ll build: A bootloader that fits in exactly 512 bytes, displays “Hello, Bare Metal!” on screen using BIOS interrupts, and ends with the magic boot signature 0xAA55.

Why it teaches bootloaders: This is THE starting point. You’ll understand why bootloaders are exactly 512 bytes (MBR constraint), how the BIOS loads code at address 0x7C00, and how to use BIOS interrupts (INT 10h) for output before any OS exists. You’re literally writing the first code that runs after the firmware.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Understanding the boot address (0x7C00) → maps to memory layout at boot

- Writing position-independent or origin-aware code → maps to how code addresses work

- Using BIOS interrupts (INT 10h, INT 13h) → maps to firmware services

- Fitting everything in 512 bytes with 0xAA55 signature → maps to MBR structure

- Creating a bootable disk image → maps to disk layout fundamentals

Key Concepts:

- Reset Vector and Initial Execution: “Low-Level Programming” Chapter 1 - Igor Zhirkov

- x86 Real Mode Segmentation: OSDev Wiki - Real Mode

- BIOS Interrupts: Ralf Brown’s Interrupt List

- MBR Structure: “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” Chapter 7 - Bryant & O’Hallaron

Prerequisites: Basic understanding of hexadecimal, willingness to read x86 assembly

Real World Outcome

# After assembling your bootloader

$ nasm -f bin boot.asm -o boot.bin

$ qemu-system-x86_64 -drive format=raw,file=boot.bin

# You'll see in the QEMU window:

Hello, Bare Metal!

_

The cursor blinks on a black screen with your message. You wrote the very first code that ran on this (virtual) machine. No OS, no libraries, just your bytes.

Implementation Hints: Your bootloader must:

- Start with

ORG 0x7C00or set up segments correctly (BIOS loads you here) - Set up segment registers (DS, ES, SS) - they’re undefined at boot!

- Set up a stack (SP register) - you need it for any CALL instructions

- Use

INT 10h, AH=0Eh(teletype output) to print characters one by one - End with

times 510-($-$$) db 0to pad to 510 bytes - Finish with

dw 0xAA55- the magic boot signature

The BIOS checks the last two bytes of the first sector. If they’re not 0x55 0xAA (little-endian: 0xAA55), it won’t boot your code.

Learning milestones:

- Code runs in QEMU → You understand the boot process initiates

- “Hello” appears on screen → You can use BIOS services

- You can modify and reload instantly → You have a development cycle for bare-metal code

The Core Question You’re Answering

“What is the very first code that runs when a computer boots, and how does it work without an operating system?”

This project answers the fundamental question of how a computer transitions from powered-off hardware to running code. You’ll discover:

- How the BIOS/firmware finds and executes your code

- Why the first sector of a disk is special (Master Boot Record)

- How to interact with hardware when there’s no OS, no standard library, and no runtime

- What “bare metal” programming actually means in practice

This is the foundation of understanding every boot process, from embedded systems to modern UEFI systems. You’re writing code that runs in an environment with almost no abstractions—just the CPU, memory, and firmware services.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Before writing a single line of assembly, you need to understand these foundational concepts:

1. Memory Addressing at Boot (0x7C00)

- Why 0x7C00?: Historical convention from early IBM PCs (32KB - 1KB for boot sector)

- Physical vs. Logical Addressing: At boot, no MMU/paging exists; addresses are physical

- Book Reference: “Low-Level Programming” by Igor Zhirkov, Chapter 1 (Memory and Data)

- Key Insight: The BIOS loads your 512-byte bootloader to physical address 0x7C00 and jumps there

2. x86 Real Mode Operation

- What is Real Mode?: The CPU starts in 16-bit real mode (8086 compatibility mode)

- Limitations: Only 1MB addressable memory (20-bit addressing), no memory protection

- Registers Available: AX, BX, CX, DX, SI, DI, BP, SP, and segment registers (CS, DS, ES, SS)

- Book Reference: “PC Assembly Language” by Paul A. Carter, Chapter 1

- Key Insight: Your bootloader runs in the same CPU mode as 1981 computers

3. Segment:Offset Addressing

- The Formula: Physical Address = (Segment × 16) + Offset

- Example: 0x07C0:0x0000 = (0x07C0 × 16) + 0x0000 = 0x7C00

- Alternative: 0x0000:0x7C00 = (0x0000 × 16) + 0x7C00 = 0x7C00

- Why It Matters: You must initialize segment registers; BIOS doesn’t guarantee their values

- Book Reference: “Low-Level Programming” by Igor Zhirkov, Chapter 2 (Assembly Language)

- Common Pitfall: Forgetting to set DS causes data reads from wrong memory locations

4. BIOS Interrupts (INT 10h for Video)

- What are BIOS Interrupts?: Software interrupts (INT instruction) that call firmware services

- INT 10h, AH=0Eh: Teletype output function (prints one character)

- Input: AL = character to print, BH = page number (usually 0), BL = color (text mode)

- Output: Character appears on screen, cursor advances

- Why Use Interrupts?: Only way to access hardware before writing device drivers

- Book Reference: “The Art of Assembly Language” by Randall Hyde, Chapter 12 (Interrupts)

- Resource: Ralf Brown’s Interrupt List - Complete INT 10h reference

5. MBR Structure and Magic Signature (0xAA55)

- Master Boot Record Layout:

- Bytes 0-445: Boot code (your program)

- Bytes 446-509: Partition table (optional, unused in simple bootloaders)

- Bytes 510-511: Boot signature (0x55 0xAA in little-endian)

- Why 0xAA55?: BIOS checks these bytes to verify sector is bootable

- Little-Endian: Intel CPUs store 0xAA55 as [0x55, 0xAA] in memory

- Book Reference: “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” by Bryant & O’Hallaron, Chapter 6

- Critical Rule: Without this signature, BIOS won’t execute your code

6. ORG Directive (Origin)

- What ORG Does: Tells assembler where code will be loaded in memory

- ORG 0x7C00: All labels/addresses calculated relative to 0x7C00

- Without ORG: Assembler assumes origin 0, causing wrong addresses for data/jumps

- Book Reference: NASM Manual, Section 3.3 (ORG Directive)

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before coding, answer these design questions to understand what you’re building:

Memory and Addressing

- How does

ORG 0x7C00affect label addresses in your code?- What address does

msg:label get if your string is at byte 20? - What happens if you omit ORG and try to access data?

- What address does

- Why must you initialize segment registers (DS, ES, SS)?

- What values might they have at boot?

- What breaks if DS points to the wrong segment?

- Where should you place your stack, and why?

- What address range is safe?

- What happens if the stack grows into your code?

BIOS Interaction

- How do you print characters using INT 10h?

- Which registers need to be set?

- How do you print a string (multiple characters)?

- What’s the difference between teletype mode and direct video memory writes?

- What state does the BIOS leave the system in when it jumps to 0x7C00?

- Which registers are defined vs. undefined?

- Is the screen cleared?

- Are interrupts enabled?

Code Structure

- How do you ensure your bootloader is exactly 512 bytes?

- How do you pad the remaining space?

- Where does the 0xAA55 signature go?

- What if your code exceeds 510 bytes?

- Should your bootloader halt, hang, or loop after printing?

- What happens if the CPU continues executing past your code?

- How do you create an infinite loop in assembly?

Debugging

- If nothing appears on screen, what could be wrong?

- How do you verify the bootloader is loaded?

- How do you check if INT 10h is being called?

- What tools can inspect the boot process?

Thinking Exercise

Before writing any code, complete this mental (or paper-based) trace-through:

Exercise: Boot Process Trace

Imagine you’re the CPU. Walk through what happens byte-by-byte:

- Power-On (T=0 seconds):

- CPU starts executing BIOS code from firmware ROM

- BIOS initializes hardware (memory controller, video card, etc.)

- BIOS Boot Search (T=2 seconds):

- BIOS reads first sector (512 bytes) from boot device to memory address 0x7C00

- BIOS checks if bytes 510-511 equal 0x55, 0xAA

- If yes: Jump to 0x7C00 and start executing your code

- If no: Try next boot device or show “No bootable device” error

- Your Code Executes (T=2.1 seconds):

- CPU instruction pointer (IP) = 0x7C00, Code Segment (CS) = 0x0000

- First instruction: What is it in your code?

- If it’s

ORG 0x7C00andmov si, msg: Where does SI point? - Calculate: If

msgis at offset 30 from start, SI = 0x7C00 + 30 = 0x7C1E

- Printing “Hello”:

- You load ‘H’ (0x48) into AL

- You call INT 10h with AH=0Eh

- BIOS interrupt handler runs, writes ‘H’ to video memory at cursor position

- Cursor advances

- Repeat for each character

Questions to answer in your trace:

- If your code is at 0x7C00 and you declare a string at byte 20, what’s its address?

- If DS=0x1000 instead of 0x0000, what address does [SI] actually read from?

- If you forget to set AH=0Eh before INT 10h, what happens?

- If you omit the 0xAA55 signature, at what point does the boot fail?

Deliverable: Write out the memory map:

Address Range | Contents

-----------------|---------------------------------

0x0000 - 0x03FF | BIOS Interrupt Vector Table

0x0400 - 0x04FF | BIOS Data Area

0x0500 - 0x7BFF | Free (your stack can go here)

0x7C00 - 0x7DFF | Your bootloader (512 bytes)

0x7E00 - 0x9FFFF | Free (where stage 2 could go)

0xA0000 - 0xFFFFF| Video memory, BIOS ROM, etc.

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

If you put “bootloader development” on your resume, expect these questions:

Basic Understanding

- “What is the boot signature and why is it required?”

- Answer: 0xAA55 (stored as 0x55 0xAA in little-endian) at bytes 510-511. BIOS checks this to verify the sector is bootable. Without it, BIOS won’t execute the code.

- Follow-up: “Why those specific bytes?” (Historical marker from IBM PC BIOS design)

- “Why is the bootloader loaded at 0x7C00 specifically?”

- Answer: Historical convention from original IBM PC. Located 32KB - 1KB into memory, leaving room below for BIOS data structures (interrupt vector table at 0x0000, BIOS data area at 0x0400).

- Deeper: Modern systems keep this for backward compatibility.

- “What CPU mode does the bootloader run in?”

- Answer: 16-bit Real Mode (8086 compatibility). No memory protection, only 1MB addressable, segment:offset addressing.

- Follow-up: “How do you switch to Protected Mode?” (Load GDT, set PE bit in CR0)

Technical Details

- “Explain segment:offset addressing. What’s the physical address of 0x07C0:0x0010?”

- Answer: Physical = (Segment × 16) + Offset = (0x07C0 × 16) + 0x0010 = 0x7C00 + 0x10 = 0x7C10

- Insight: Multiple segment:offset pairs can point to same physical address

- “How do you print to the screen in a bootloader?”

- Answer: Use BIOS INT 10h, AH=0Eh (teletype output). Load character in AL, page in BH, call INT 10h. Alternatively, write directly to video memory at 0xB8000 (faster but text mode only).

- Follow-up: “What if BIOS interrupts are disabled?” (Write to video memory directly)

- “What happens if you forget to set the Data Segment (DS) register?”

- Answer: DS might contain garbage from BIOS, so data reads (like

mov al, [si]) will read from wrong memory locations, causing incorrect behavior or crashes. - Best Practice: Initialize DS, ES, SS explicitly at bootloader start.

- Answer: DS might contain garbage from BIOS, so data reads (like

- “Why do you need

ORG 0x7C00directive?”- Answer: Tells assembler that code will run at 0x7C00, so it calculates label addresses correctly. Without it, assembler assumes origin 0, making all data/jump addresses wrong.

- Alternative: Set segment registers to 0x07C0 and use ORG 0.

Problem-Solving

- “Your bootloader compiles but nothing appears on screen. Debugging steps?”

- Answer:

- Verify 512-byte size and 0xAA55 signature (hexdump the binary)

- Check QEMU boots it (if stuck, signature might be wrong)

- Add infinite loop at start to verify code runs

- Test INT 10h with single character

- Check DS register initialization

- Use QEMU monitor to inspect registers/memory

- Answer:

- “How would you load a second stage bootloader from disk?”

- Answer: Use BIOS INT 13h (disk services):

- AH=02h (read sectors), AL=sectors to read

- CH=cylinder, CL=sector, DH=head, DL=drive number

- ES:BX = destination buffer (e.g., 0x0000:0x7E00)

- Load more code beyond 512 bytes and jump to it

- Answer: Use BIOS INT 13h (disk services):

- “What’s the maximum size of a single-stage bootloader?”

- Answer: 446 bytes of code (if using standard MBR with partition table), or 510 bytes (if no partition table). Must reserve 2 bytes for 0xAA55 signature.

- Real-world: Most use two-stage bootloaders (GRUB, LILO) to bypass this limit.

Advanced Scenarios

- “How does UEFI boot differ from BIOS/MBR boot?”

- Answer: UEFI uses GPT partition scheme, loads .efi files (PE format) from FAT32 ESP partition, starts in protected/long mode, provides richer services. No 512-byte limit, no Real Mode.

- Transition: Modern systems support both (UEFI with CSM for legacy BIOS boot).

- “Can you write a bootloader in C?”

- Answer: Partially. You need assembly stub to set up segments/stack, then can call C code compiled with

-ffreestanding -nostdlib. But size constraints make pure assembly more practical. - Example: GRUB stage 1.5 uses this approach.

- Answer: Partially. You need assembly stub to set up segments/stack, then can call C code compiled with

Hints in Layers

Use these progressive hints only when stuck. Try each level before moving to the next.

Hint 1: Starting with the Skeleton (If you don’t know where to begin)

Your bootloader needs this basic structure:

[BITS 16] ; We're in 16-bit Real Mode

[ORG 0x7C00] ; BIOS loads us here

start:

; Initialize segment registers here

; Set up stack here

; Your code to print message here

; Infinite loop or halt here

message: db 'Hello, Bare Metal!', 0

; Padding and boot signature here

Questions this raises:

- What instructions initialize segment registers?

- Where should the stack pointer point?

- How do you print the message?

If still stuck, proceed to Hint 2.

Hint 2: Setting Up Segments (If registers confuse you)

At boot, segment registers have undefined values. You must initialize them:

start:

xor ax, ax ; AX = 0

mov ds, ax ; DS = 0 (data segment)

mov es, ax ; ES = 0 (extra segment)

mov ss, ax ; SS = 0 (stack segment)

mov sp, 0x7C00 ; Stack grows DOWN from 0x7C00

Why this works:

- We use segment 0, so all addresses are direct offsets

- Stack at 0x7C00 grows down to 0x0500 (safe area)

- ORG 0x7C00 means our labels are absolute addresses

Next challenge: How do you loop through the message string and print each character?

If still stuck, proceed to Hint 3.

Hint 3: Printing Loop (If BIOS interrupt is unclear)

Print each character using INT 10h:

mov si, message ; SI points to string

print_loop:

lodsb ; Load byte at [SI] into AL, increment SI

cmp al, 0 ; Check for null terminator

je done ; If zero, we're done

mov ah, 0x0E ; Teletype output function

mov bh, 0 ; Page 0

int 0x10 ; Call BIOS video service

jmp print_loop ; Repeat for next character

done:

hlt ; Halt the CPU

jmp done ; If interrupts wake CPU, halt again

Key instructions:

lodsb: Load String Byte (DS:SI → AL, then SI++)int 0x10: Software interrupt, calls BIOShlt: Halt until interrupt (low power)

Final challenge: How do you pad to 512 bytes and add signature?

If still stuck, proceed to Hint 4.

Hint 4: Padding and Signature (If size is wrong)

Ensure exactly 512 bytes with signature at end:

times 510-($-$$) db 0 ; Pad with zeros to byte 510

dw 0xAA55 ; Boot signature (little-endian)

What this means:

$: Current position$$: Start of section (with ORG, equals 0x7C00)$-$$: Bytes written so far510-($-$$): Remaining bytes to reach 510times: Repeat thedb 0instructiondw 0xAA55: Write word (2 bytes) in little-endian

Verify:

$ nasm -f bin boot.asm -o boot.bin

$ ls -l boot.bin

-rw-r--r-- 1 user user 512 Jan 15 10:30 boot.bin

$ hexdump -C boot.bin | tail -n 1

000001f0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 55 aa

Notice the 55 aa at the end (little-endian for 0xAA55).

Hint 5: Debugging with QEMU (If nothing appears)

Test in stages:

Stage 1: Does it boot?

$ qemu-system-x86_64 -drive format=raw,file=boot.bin

If QEMU window opens (doesn’t say “No bootable device”), signature is correct.

Stage 2: Is code running? Add infinite loop at the very start:

start:

jmp start ; Infinite loop

If QEMU hangs (doesn’t reboot), code is executing.

Stage 3: Test INT 10h with one character:

start:

mov ah, 0x0E

mov al, 'A'

int 0x10

jmp $

If ‘A’ appears, BIOS interrupts work.

Stage 4: Inspect with QEMU monitor:

$ qemu-system-x86_64 -drive format=raw,file=boot.bin -monitor stdio

(qemu) info registers # Show all registers

(qemu) x/20i 0x7C00 # Disassemble 20 instructions at 0x7C00

(qemu) x/512xb 0x7C00 # Hex dump your bootloader

Common Issues:

- DS not initialized → reads wrong memory

- Stack not set → CALL/RET instructions crash

- String not null-terminated → prints garbage

- Wrong INT 10h function → AH must be 0x0E

Hint 6: Complete Working Example (Last resort)

If you’ve tried everything and still stuck, here’s a minimal working bootloader:

[BITS 16]

[ORG 0x7C00]

start:

; Initialize segments

cli ; Disable interrupts while setting up stack

xor ax, ax

mov ds, ax

mov es, ax

mov ss, ax

mov sp, 0x7C00 ; Stack grows down from bootloader

sti ; Re-enable interrupts

; Print message

mov si, msg

.loop:

lodsb

or al, al ; Check for null (sets ZF if AL=0)

jz .done

mov ah, 0x0E ; Teletype function

mov bh, 0 ; Page 0

mov bl, 0x07 ; Light gray color

int 0x10

jmp .loop

.done:

hlt

jmp .done

msg: db 'Hello, Bare Metal!', 0

times 510-($-$$) db 0

dw 0xAA55

Assemble and run:

$ nasm -f bin boot.asm -o boot.bin

$ qemu-system-x86_64 -drive format=raw,file=boot.bin

Study this code: Understand every instruction before moving forward.

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

When building your first bootloader, you’ll encounter these issues. Here’s how to solve them:

Problem 1: “Black screen—nothing happens, QEMU just hangs”

- Why: Your bootloader is executing, but not producing output. The CPU is either in an infinite loop or has crashed.

- Fix: Add an infinite loop as the last instruction to prove code is running:

halt: hlt jmp haltIf QEMU stops responding (doesn’t reboot), your code is executing.

- Quick test: Run

qemu-system-x86_64 -drive format=raw,file=boot.bin -monitor stdioand typeinfo registersto see CPU state.

Problem 2: “QEMU says ‘No bootable device’“

- Why: The boot signature (0xAA55) is missing or incorrect.

- Fix: Check the last two bytes of your binary:

$ hexdump -C boot.bin | tail -n 1 000001f0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 55 aaMust end with

55 aa(little-endian). - Quick test: Verify file is exactly 512 bytes:

ls -l boot.binshould show 512.

Problem 3: “Garbage characters appear instead of my message”

- Why: Data segment (DS) not initialized—CPU is reading from wrong memory location.

- Fix: Add at the start of your code:

xor ax, ax mov ds, axThis sets DS to 0, so segment 0x0000 is used with your ORG 0x7C00 offset.

- Quick test: Print a single character first to verify INT 10h works:

mov ah, 0x0E mov al, 'A' int 0x10

Problem 4: “Only first character prints, then stops”

- Why: Your loop logic is broken or string is not null-terminated.

- Fix: Ensure your string ends with 0:

msg: db 'Hello', 0 ; The 0 is crucialAnd your loop checks for null:

lodsb ; Load byte from DS:SI into AL or al, al ; Check if AL is 0 jz .done ; If zero, exit loop - Quick test: Use QEMU monitor to inspect memory at your string address.

Problem 5: “System reboots immediately after bootloader runs”

- Why: Your bootloader finishes execution and CPU continues executing random memory.

- Fix: End with an infinite loop:

halt: hlt ; Halt CPU until next interrupt jmp halt ; Jump back to hlt (in case of interrupts) - Quick test: This is normal behavior if you forgot the halt loop.

Problem 6: “NASM error: ‘symbol undefined’“

- Why: You’re using a label that doesn’t exist, or you have a typo.

- Fix: Check all label names match exactly (case-sensitive):

jmp start ; Label must exist as "start:" - Quick test: Run

nasm -f bin boot.asm -o boot.bin -l boot.lstto generate a listing file showing all symbols.

Problem 7: “File is not exactly 512 bytes”

- Why: Your padding calculation is wrong.

- Fix: Use this exact padding formula:

times 510-($-$$) db 0 ; Pad to 510 bytes dw 0xAA55 ; Add 2-byte signature (total: 512)$= current address,$$= start of section,($-$$)= bytes used so far. - Quick test:

ls -l boot.binmust show exactly 512 bytes.

Problem 8: “Works in QEMU but not on real hardware”

- Why: Real hardware has timing issues, different BIOS implementations, or USB boot quirks.

- Fix: Test with different BIOS/UEFI modes. Try:

$ dd if=boot.bin of=/dev/sdX bs=512 count=1 # Write to USB drive (careful with device name!)Boot in Legacy/CSM mode, not UEFI.

- Quick test: Try on VirtualBox or VMware first—closer to real hardware than QEMU.

Debugging Technique: Step-by-Step Verification

If completely stuck, build your bootloader in stages:

Stage 1: Boot signature only

times 510 db 0

dw 0xAA55

Result: QEMU should open a window (no error about “no bootable device”).

Stage 2: Infinite loop

start:

jmp start

times 510-($-$$) db 0

dw 0xAA55

Result: QEMU hangs (doesn’t reboot)—code is executing.

Stage 3: Single character

start:

mov ah, 0x0E

mov al, 'A'

int 0x10

jmp $

times 510-($-$$) db 0

dw 0xAA55

Result: ‘A’ appears on screen—BIOS interrupts work.

Stage 4: Full string printing (your final bootloader)

This incremental approach isolates where the problem is.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Specific Chapter/Section | Why It Helps |

|---|---|---|---|

| x86 Assembly Basics | “Low-Level Programming: C, Assembly, and Program Execution on Intel® 64 Architecture” by Igor Zhirkov | Chapter 2: Assembly Language | Covers registers, instruction formats, and NASM syntax. Best modern introduction to x86 assembly. |

| Real Mode and Segmentation | “PC Assembly Language” by Paul A. Carter | Chapter 1: Introduction (Sections 1.3-1.4) | Explains segment:offset addressing with clear examples. Free online. |

| BIOS Interrupts | “The Art of Assembly Language” (2nd Edition) by Randall Hyde | Chapter 12: Interrupts, Traps, and Exceptions | Details how software interrupts work at the hardware level. |

| Boot Process Fundamentals | “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” (3rd Edition) by Bryant & O’Hallaron | Chapter 7: Linking (Section 7.9: Loading Executable Object Files) | Explains how code gets loaded and executed, foundational concepts. |

| MBR and Disk Layout | “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” by Remzi & Andrea Arpaci-Dusseau | Chapter 40: File System Implementation | Context on disk sectors and boot sectors. Free online. |

| Advanced Bootloader Topics | “Operating System Concepts” (10th Edition) by Silberschatz, Galvin, Gagne | Chapter 2: Operating-System Structures (Section 2.10: System Boot) | High-level overview of boot process stages. |

| x86 Architecture Reference | “Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manual” (Free PDF) | Volume 1, Chapter 3: Basic Execution Environment | Official CPU reference. Dense but authoritative. |

| NASM Assembler | “NASM Manual” (Free online) | Chapter 3: The NASM Language | Essential for understanding directives like ORG, TIMES, BITS. |

| Practical Bootloader Examples | “Writing a Simple Operating System — from Scratch” by Nick Blundell (Free PDF) | Pages 1-20: Bootloader Section | Step-by-step bootloader tutorial with excellent diagrams. |

| Debugging Bare Metal Code | “QEMU Documentation” (Free online) | QEMU System Emulation User’s Guide | How to use QEMU monitor, inspect memory, debug bootloaders. |

Online Resources (Free and Essential):

| Resource | URL | What It Covers |

|---|---|---|

| OSDev Wiki | https://wiki.osdev.org | Comprehensive OS development wiki. See “Boot Sequence”, “Real Mode”, “Memory Map” articles. |

| Ralf Brown’s Interrupt List | http://www.ctyme.com/rbrown.htm | Complete BIOS interrupt reference. Search “INT 10” for video services. |

| x86 Instruction Reference | https://www.felixcloutier.com/x86/ | Searchable x86 instruction set with detailed descriptions. |

| NASM Tutorial | https://cs.lmu.edu/~ray/notes/nasmtutorial/ | Beginner-friendly NASM introduction. |

Reading Order:

- Start with Paul Carter’s “PC Assembly Language” Chapter 1 (Real Mode intro)

- Read Nick Blundell’s bootloader section (practical hands-on)

- Use OSDev Wiki as reference while coding

- Consult Ralf Brown’s list for INT 10h details

- Deep dive into Igor Zhirkov’s book for assembly mastery

Project 2: “Memory Map Detective”

| Attribute | Value |

|---|---|

| Language | x86 Assembly (NASM) (alt: FASM, Mixed Assembly/C) |

| Difficulty | Intermediate |

| Time | Weekend |

| Coolness | ★★★☆☆ Genuinely Clever |

| Portfolio Value | Resume Gold |

What you’ll build: A bootloader that queries the BIOS for the system memory map using INT 15h, EAX=E820h, then displays all memory regions (usable RAM, reserved, ACPI, etc.) with their addresses and sizes.

Why it teaches bootloaders: Real bootloaders must know where RAM is! Not all addresses are usable—some are reserved for hardware, BIOS, video memory. This is exactly what GRUB and Linux do during early boot. You’ll understand why bootloaders can’t just assume memory layout.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Calling INT 15h E820 correctly → maps to BIOS service conventions

- Parsing the returned memory map structure → maps to hardware/software interface

- Handling continuation (multiple calls needed) → maps to stateful BIOS APIs

- Converting 64-bit addresses to displayable hex → maps to number formatting without libraries

- Understanding memory type codes → maps to hardware memory mapping

Key Concepts:

- E820 Memory Map: OSDev Wiki - Detecting Memory

- BIOS Data Area: “The Art of Assembly Language” Chapter 13 - Randall Hyde

- Physical vs Virtual Memory: “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” Chapter 13 - Arpaci-Dusseau

- x86 Memory Layout at Boot: “Low-Level Programming” Chapter 3 - Igor Zhirkov

Prerequisites: Project 1 completed, basic hex arithmetic

Real World Outcome

Memory Map (E820):

Region 0: 0x0000000000000000 - 0x000000000009FBFF (639 KB) Type: Usable

Region 1: 0x000000000009FC00 - 0x000000000009FFFF (1 KB) Type: Reserved

Region 2: 0x00000000000E0000 - 0x00000000000FFFFF (128 KB) Type: Reserved

Region 3: 0x0000000000100000 - 0x000000001FFFFFFF (511 MB) Type: Usable

Region 4: 0x00000000FEC00000 - 0x00000000FFFFFFFF (20 MB) Type: Reserved

Total usable memory: 512 MB

You now see exactly what the BIOS tells the OS about available memory—the same info Linux uses!

Implementation Hints: The E820 call is iterative. Each call returns one memory region and a “continuation value” in EBX. You call it repeatedly with the previous EBX until EBX returns as 0. The structure returned contains: base address (64-bit), length (64-bit), and type (32-bit). Type 1 = usable RAM, Type 2 = reserved, Type 3 = ACPI reclaimable, etc.

Learning milestones:

- First E820 call works → You understand BIOS parameter passing

- All regions display correctly → You can parse binary structures

- You identify where your bootloader lives in this map → Memory layout clicks

The Core Question You’re Answering

How does a bootloader discover what memory is actually available, and why can’t it just assume a flat, continuous address space?

At boot time, not all physical addresses are backed by usable RAM. Some regions are reserved for:

- BIOS ROM and data structures

- Memory-mapped I/O devices (video cards, network cards)

- ACPI tables for power management

- System Management Mode (SMM) memory

The E820 BIOS call is the standard way bootloaders discover the true memory layout. Without this information, your bootloader might try to load a kernel into an address that doesn’t exist or is reserved for hardware, causing a crash or data corruption.

Understanding this is fundamental because:

- Modern operating systems still rely on this boot-time memory map

- You’ll see why 64-bit systems need 64-bit addressing even in 16-bit real mode

- You’ll understand the difference between physical and logical memory layouts

Concepts You Must Understand First

1. E820 Memory Map BIOS Call (INT 15h, EAX=E820h)

What it is: A BIOS interrupt service that returns the physical memory layout one region at a time.

Book references:

- “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” (Bryant & O’Hallaron) - Chapter 9: Virtual Memory

- Section 9.1: Physical and Virtual Addressing

- Understanding how physical memory is organized at the hardware level

- OSDev Wiki: Detecting Memory (x86)

- Complete E820 specification and examples

Key details:

- Input registers: EAX=0xE820, EDX=’SMAP’ (0x534D4150), EBX=continuation value, ECX=buffer size, ES:DI=buffer pointer

- Output: EAX=’SMAP’ (success), EBX=continuation (0 if last entry), ECX=bytes written, CF=carry flag (error if set)

- Each call returns ONE memory region descriptor

2. Memory Region Types

The E820 call returns different memory types:

| Type | Name | Description | Can OS Use? |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Usable RAM | Normal system memory | Yes |

| 2 | Reserved | Reserved by BIOS/hardware | No |

| 3 | ACPI Reclaimable | ACPI tables (can reclaim after reading) | After parsing |

| 4 | ACPI NVS | ACPI Non-Volatile Storage | No |

| 5 | Bad Memory | Defective RAM regions | No |

| Other | Vendor-specific | Hardware-specific regions | Usually No |

Book references:

- “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” (Arpaci-Dusseau) - Chapter 13: Address Spaces

- Understanding how OSes view physical memory

- “Low-Level Programming” (Igor Zhirkov) - Chapter 3: Assembly Language

- Section on x86 memory layout and BIOS data structures

3. 64-bit Addresses in 16-bit Real Mode

The paradox: In 16-bit real mode, registers are only 16 bits, but physical addresses can be 64 bits on modern systems.

How E820 solves this:

- Returns addresses as 64-bit values (8 bytes) stored in memory

- You access them as two 32-bit values (low DWORD and high DWORD)

- Or as four 16-bit values for display purposes

Book references:

- “The Art of Assembly Language” (Randall Hyde) - Chapter 4: Constants, Variables, and Data Types

- Multi-precision arithmetic and extended precision values

- “Programming from the Ground Up” (Jonathan Bartlett) - Chapter 9: Intermediate Memory Topics

Example structure in memory:

Offset Size Field

+0 8 bytes Base Address (64-bit)

+8 8 bytes Length (64-bit)

+16 4 bytes Type (32-bit)

+20 4 bytes Extended Attributes (optional)

4. Continuation Values and Stateful APIs

Why continuation is needed: The memory map can have dozens of regions, but the BIOS returns them one at a time.

How it works:

- First call: Set EBX=0

- BIOS returns: EBX=continuation value (opaque, could be anything)

- Next calls: Pass previous EBX value back

- Last entry: BIOS returns EBX=0 (signals completion)

Critical rule: NEVER modify the continuation value. It’s an opaque token managed by the BIOS.

Book references:

- “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” (Bryant & O’Hallaron) - Chapter 1: A Tour of Computer Systems

- Section 1.7.4: System Calls and State Management

Common pitfalls:

- Assuming a fixed number of regions (wrong!)

- Not checking the carry flag for errors

- Using a buffer smaller than 24 bytes

- Not preserving the continuation value between calls

5. Physical Memory Layout at Boot

Typical x86 memory map (varies by system):

0x00000000 - 0x000003FF Real Mode IVT (Interrupt Vector Table)

0x00000400 - 0x000004FF BIOS Data Area (BDA)