Advanced UNIX Programming Mastery - Real World Projects

Goal: Deeply understand UNIX systems programming from first principles—the system calls that form the foundation of every application running on Linux, macOS, and BSD. You will implement file systems, process managers, signal handlers, thread pools, daemon services, IPC mechanisms, network servers, and terminal emulators. By the end, you won’t just call

fork()orselect(); you’ll understand exactly what happens in the kernel and why UNIX was designed this way. This knowledge is the bedrock of all systems programming—everything from Docker to nginx to PostgreSQL is built on these primitives.

Why Advanced UNIX Programming Matters

In 1969, Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie created UNIX at Bell Labs. Over 55 years later, its design principles power virtually every server on the internet, every Android phone, every Mac, and the vast majority of embedded systems. Understanding UNIX isn’t just learning an old operating system—it’s understanding the grammar of computing itself.

The UNIX Family Tree (Simplified)

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ UNIX (1969) │

│ Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie │

└──────────────────────┬──────────────────────────────┘

│

┌───────────────┬───────────────┼───────────────┬───────────────┐

│ │ │ │ │

v v v v v

┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐

│ BSD │ │ System V │ │ Minix │ │ Xenix │ │ Plan 9 │

│ (1977) │ │ (1983) │ │ (1987) │ │ (1980) │ │ (1992) │

└────┬─────┘ └────┬─────┘ └────┬─────┘ └──────────┘ └──────────┘

│ │ │

v v v

┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐

│ FreeBSD │ │ Solaris │ │ Linux │

│ OpenBSD │ │ HP-UX │ │ (1991) │

│ NetBSD │ │ AIX │ │ Linus │

└────┬─────┘ └──────────┘ └────┬─────┘

│ │

v v

┌──────────┐ ┌──────────────────────────────────┐

│ macOS │ │ Android, Chrome OS, Embedded, │

│ (2001) │ │ Cloud Infrastructure, Servers │

└──────────┘ └──────────────────────────────────┘

The Numbers Don’t Lie (2025)

Market Dominance:

- 96.3% of the top 1 million web servers run Linux/UNIX (Linux Statistics 2025)

- 100% of the top 500 supercomputers run Linux (continuing since 2017)

- 53% of all servers globally run Linux, vs 30% Windows Server, ~9% UNIX (Server Statistics 2025)

- 49.2% of global cloud workloads run on Linux as of Q2 2025

- 72.7% of Fortune 1000 companies use Linux container orchestration (Kubernetes)

Enterprise & Development:

- 78.5% of SAP clients deploy applications on Linux systems

- 90.1% of cloud-native developers work on Linux environments

- 68.2% of DevOps teams prefer Linux for their infrastructure (Linux Interview Guide 2025)

- 47% of professional developers use Unix/Linux as their primary development OS

- 60%+ of public cloud Linux instances run Ubuntu distributions

Scale & Economics:

- 3+ billion Android devices run a Linux kernel

- The Linux kernel has 27+ million lines of C code, all using UNIX APIs

- 5,000+ active kernel developers contribute each release cycle

- Linux server OS market: $22.28 billion (2025) → projected $34.12 billion by 2030 (Market Growth Reports)

- Expected CAGR of 8.87% through 2034

Why W. Richard Stevens’ Book Remains Essential

“Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment” (APUE) by Stevens and Rago is called “The Bible of UNIX Programming” for good reason. While kernels evolve, the POSIX API is remarkably stable. Code written using Stevens’ techniques in 1992 still compiles and runs today.

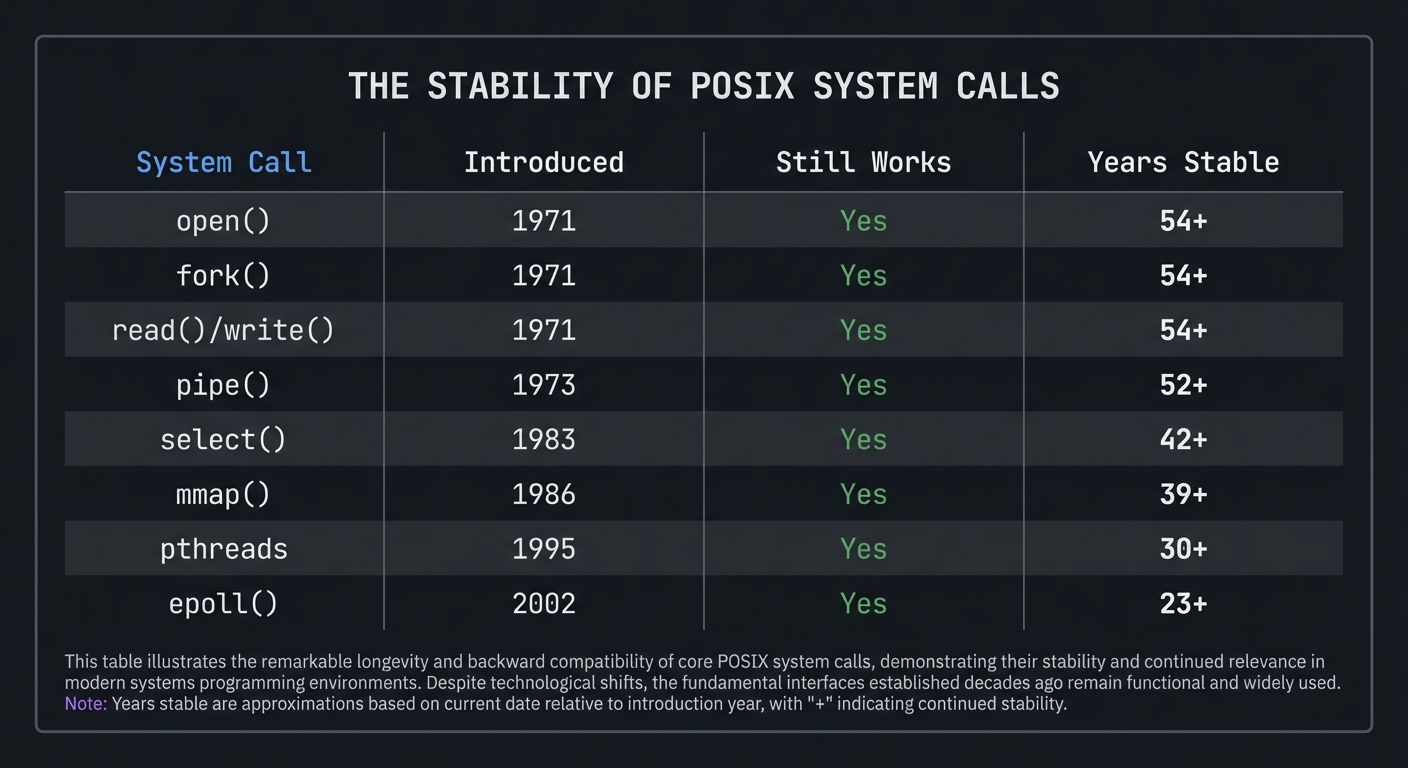

The Stability of POSIX System Calls

System Call │ Introduced │ Still Works │ Years Stable

───────────────┼────────────┼─────────────┼─────────────

open() │ 1971 │ Yes │ 54+

fork() │ 1971 │ Yes │ 54+

read()/write() │ 1971 │ Yes │ 54+

pipe() │ 1973 │ Yes │ 52+

select() │ 1983 │ Yes │ 42+

mmap() │ 1986 │ Yes │ 39+

pthreads │ 1995 │ Yes │ 30+

epoll() │ 2002 │ Yes │ 23+

The UNIX philosophy endures:

- Everything is a file (devices, sockets, pipes)

- Small programs that do one thing well

- Text streams as universal interface

- Composability through pipes and shell

- Simple, powerful primitives

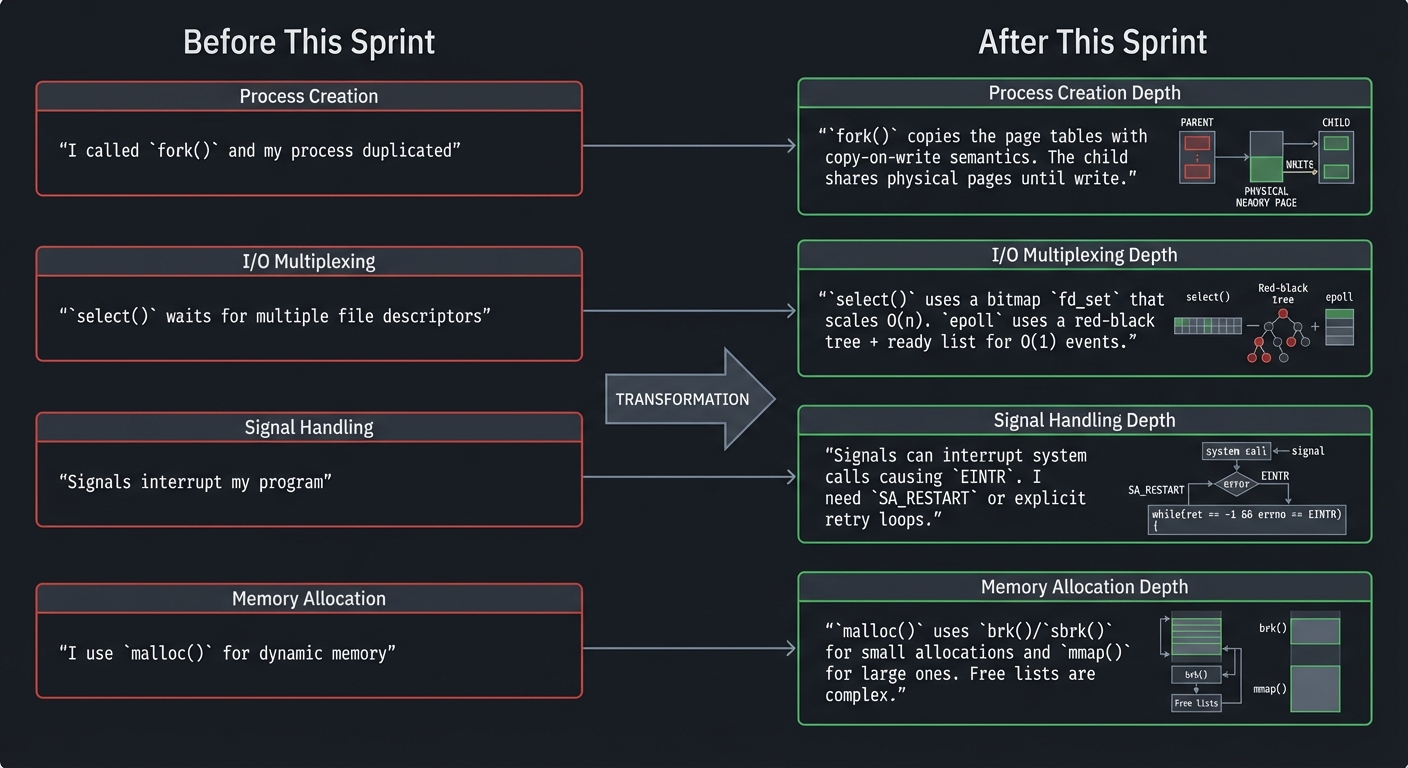

What You’ll Actually Understand

After completing these projects, you’ll understand:

Before This Sprint After This Sprint

┌──────────────────────────┐ ┌──────────────────────────────────────┐

│ "I called fork() and │ │ "fork() copies the page tables with │

│ my process duplicated" │ => │ copy-on-write semantics. The child │

│ │ │ shares physical pages until write." │

├──────────────────────────┤ ├──────────────────────────────────────┤

│ "select() waits for │ │ "select() uses a bitmap fd_set that │

│ multiple file │ => │ scales O(n). epoll uses a red-black │

│ descriptors" │ │ tree + ready list for O(1) events." │

├──────────────────────────┤ ├──────────────────────────────────────┤

│ "Signals interrupt │ │ "Signals can interrupt system calls │

│ my program" │ => │ causing EINTR. I need SA_RESTART or │

│ │ │ explicit retry loops." │

├──────────────────────────┤ ├──────────────────────────────────────┤

│ "I use malloc() for │ │ "malloc() uses brk()/sbrk() for │

│ dynamic memory" │ => │ small allocations and mmap() for │

│ │ │ large ones. Free lists are complex."│

└──────────────────────────┘ └──────────────────────────────────────┘

Interview Readiness & Career Impact

What Top Companies Ask (2025):

Systems programming knowledge is tested in technical interviews at companies like Google, Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, and unicorn startups. Based on current interview trends (Top Linux Interview Questions 2025, GeeksforGeeks Linux Questions), expect questions on:

Core Systems Programming:

- “What’s the difference between a process and a thread?”

- “Explain how fork() works and what happens to file descriptors”

- “What is a race condition and how do you prevent it?”

- “How does the Linux kernel handle interrupts?”

- “Explain virtual memory and page tables”

IPC & Networking:

- “What’s the fastest IPC mechanism and why?” (Answer: Shared memory)

- “Explain the difference between select(), poll(), and epoll()”

- “How would you debug a program using strace?”

- “What happens during a TCP three-way handshake?”

File Systems & I/O:

- “What is an inode and what information does it contain?”

- “Explain the difference between hard links and symbolic links”

- “How does the kernel handle blocking vs. non-blocking I/O?”

- “What role does the page cache play in I/O performance?”

Practical Skills Tested:

- Live coding: Implement a thread-safe queue

- System design: Design a high-performance web server

- Debugging: Find a race condition in provided code

- Trade-offs: Compare different IPC mechanisms for a use case

The Career Advantage:

After completing these projects, you’ll qualify for roles like:

- Systems Engineer ($140K-$220K): Build infrastructure at scale (Meta, Google, AWS)

- Kernel Developer ($150K-$250K): Work on Linux, BSD, or embedded OS

- Database Engineer ($130K-$200K): PostgreSQL, MongoDB internals teams

- Performance Engineer ($140K-$210K): Optimize critical paths at high-scale companies

- Site Reliability Engineer (SRE) ($130K-$200K): Google, Netflix, Stripe

- Embedded Systems Developer ($120K-$180K): IoT, automotive, aerospace

Industry Reality: A senior engineer who deeply understands UNIX systems programming can command $50K-$100K more than one who only knows frameworks.

Prerequisites & Background Knowledge

Before starting these projects, you should have foundational understanding in these areas:

Essential Prerequisites (Must Have)

C Programming (Critical):

- Comfortable with pointers, pointer arithmetic, and memory management

- Understanding of structs, unions, and bitfields

- Familiarity with the C preprocessor (#define, #ifdef)

- Experience with header files and multi-file compilation

- Recommended Reading: “The C Programming Language” by Kernighan & Ritchie — The entire book

- Alternative: “C Programming: A Modern Approach” by K.N. King — Ch. 1-20

Basic UNIX/Linux Usage:

- Comfortable in a terminal (bash/zsh)

- Understanding of file permissions (rwx, chmod, chown)

- Basic shell scripting (variables, loops, conditionals)

- Experience with make and Makefiles

- Recommended Reading: “The Linux Command Line” by Shotts — Part 1-2

Computer Architecture Basics:

- Understanding of memory hierarchy (registers, cache, RAM, disk)

- What a CPU does (fetch-decode-execute cycle)

- Difference between user mode and kernel mode

- Recommended Reading: “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” by Bryant & O’Hallaron — Ch. 1, 6, 8

Helpful But Not Required

Operating Systems Theory:

- What a process is vs. a thread

- Virtual memory concepts

- Basic scheduling

- Can learn during: Projects 4-8

- Book: “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” by Arpaci-Dusseau

Networking Fundamentals:

- TCP/IP basics

- Sockets concept

- Client-server model

- Can learn during: Projects 12-14

- Book: “TCP/IP Illustrated, Volume 1” by Stevens

Self-Assessment Questions

Before starting, ask yourself:

- ✅ Can you write a C program that reads a file and prints its contents?

- ✅ Do you know what

argcandargvare inmain()? - ✅ Can you explain what happens when you dereference a NULL pointer?

- ✅ Do you know the difference between a process and a program?

- ✅ Can you use

ls -land explain what each field means? - ✅ Have you used

gccto compile a multi-file C program? - ✅ Can you explain what

#include <stdio.h>actually does?

If you answered “no” to questions 1-4: Spend 2-4 weeks on C programming fundamentals before starting. If you answered “no” to questions 5-7: Spend 1 week on UNIX basics before starting. If you answered “yes” to all 7: You’re ready to begin!

Development Environment Setup

Required Tools:

- A UNIX-like system: Linux (Ubuntu 22.04+, Fedora 38+), macOS, or FreeBSD

- GCC or Clang compiler (gcc 11+, clang 14+)

- GNU Make

- GDB debugger

strace(Linux) ordtruss(macOS) for system call tracing- A text editor (vim, emacs, VS Code with C extension)

Recommended Tools:

valgrindfor memory debugging (Linux only)ltracefor library call tracingperffor performance analysis (Linux)tmuxfor terminal multiplexingbearfor generating compile_commands.json (IDE integration)

Testing Your Setup:

# Verify C compiler

$ gcc --version

gcc (Ubuntu 13.2.0-23ubuntu4) 13.2.0

# Verify make

$ make --version

GNU Make 4.3

# Verify debugger

$ gdb --version

GNU gdb (Ubuntu 14.1-0ubuntu1) 14.1

# Verify strace (critical for these projects)

$ strace --version

strace -- version 6.5

# Test compilation of a simple program

$ echo '#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) { printf("Hello, UNIX!\\n"); return 0; }' > test.c

$ gcc -Wall -o test test.c

$ ./test

Hello, UNIX!

$ rm test test.c

Time Investment:

- Foundation projects (1-3): 1-2 weeks each (10-20 hours)

- Core projects (4-9): 2-3 weeks each (20-40 hours)

- Advanced projects (10-14): 2-4 weeks each (30-60 hours)

- Integration projects (15-18): 3-4 weeks each (40-80 hours)

- Total sprint: 6-12 months if doing all projects sequentially

Important Reality Check:

UNIX systems programming is hard. The APIs are unforgiving—a single wrong pointer crashes your program. Race conditions appear randomly. Signal handlers can corrupt your data. This is by design: UNIX gives you power and expects you to use it correctly.

The learning process looks like this:

- Week 1: “This makes no sense”

- Week 2: “I think I understand but it doesn’t work”

- Week 3: “It works but I don’t know why”

- Week 4: “It works AND I know why”

- Week 5: “I see why they designed it this way”

Don’t skip steps. The struggle is the learning.

Core Concept Analysis

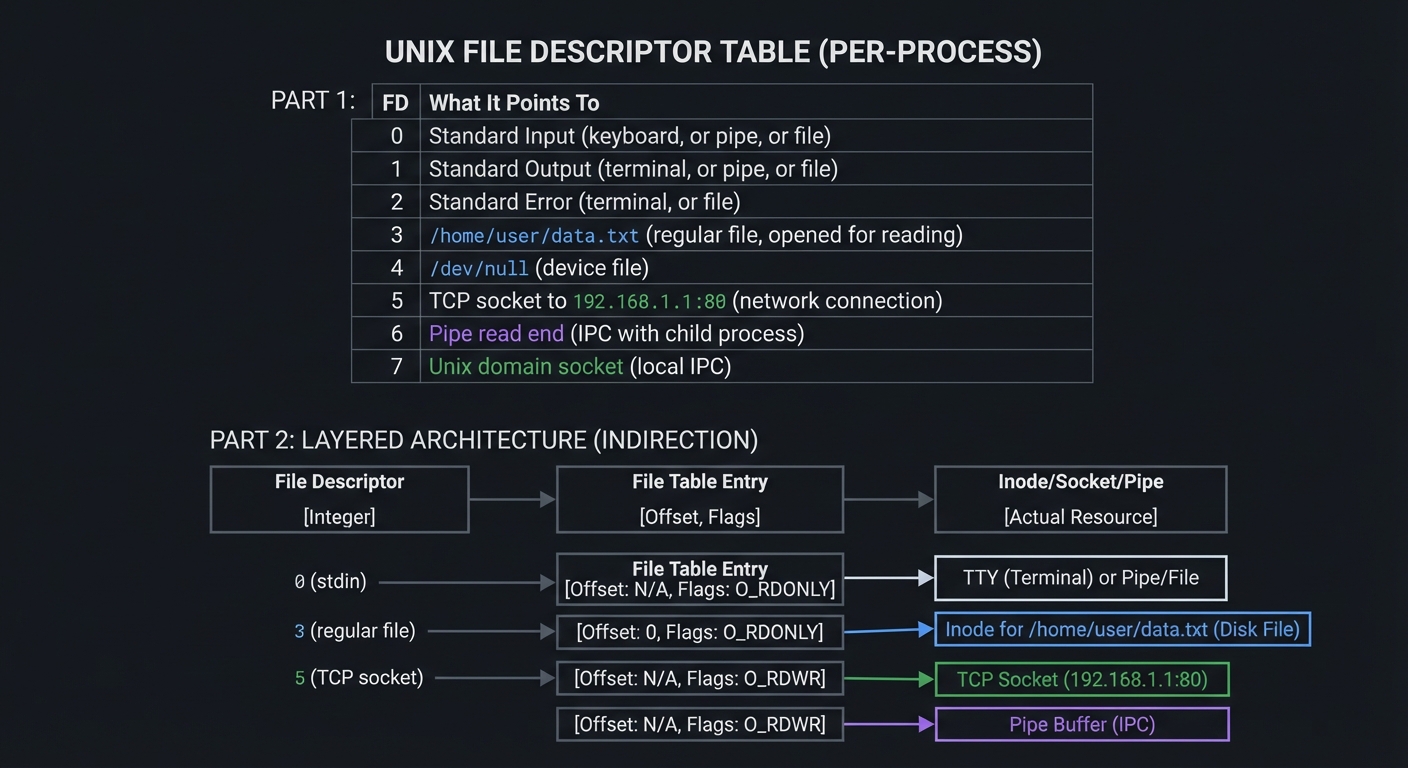

1. File Descriptors: The Universal Handle

In UNIX, everything is a file—regular files, directories, devices, network connections, pipes. A file descriptor is a small non-negative integer that serves as a handle to any open “file.”

File Descriptor Table (Per-Process)

┌─────┬────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ FD │ What It Points To │

├─────┼────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ 0 │ Standard Input (keyboard, or pipe, or file) │

│ 1 │ Standard Output (terminal, or pipe, or file) │

│ 2 │ Standard Error (terminal, or file) │

│ 3 │ /home/user/data.txt (regular file, opened for reading) │

│ 4 │ /dev/null (device file) │

│ 5 │ TCP socket to 192.168.1.1:80 (network connection) │

│ 6 │ Pipe read end (IPC with child process) │

│ 7 │ Unix domain socket (local IPC) │

└─────┴────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

File Descriptor → File Table Entry → Inode/Socket/Pipe

│ │ │

│ │ │

[Integer] [Offset,Flags] [Actual Resource]

Key Insight: When you call read(fd, buf, n), you don’t specify whether fd is a file, socket, or pipe. The kernel dispatches to the correct driver. This abstraction enables composition: cat file.txt | grep pattern works because both sides speak “file descriptor.”

2. Processes: Isolated Execution Environments

A process is a running program with its own:

- Virtual address space (isolated memory)

- File descriptor table

- Environment variables

- Process ID (PID), parent PID, user/group IDs

- Signal handlers and masks

- Current working directory

Process Memory Layout (Virtual Address Space)

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────┐ High Address (0x7FFFFFFF...)

│ Stack │ ← Local variables, return addresses

│ ↓ │ Grows downward

│ ... │

│ ↑ │

│ Heap │ ← malloc(), grows upward

├──────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Uninitialized Data (BSS) │ ← Global vars initialized to 0

├──────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Initialized Data │ ← Global vars with initial values

├──────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Text (Code) │ ← Executable instructions (read-only)

└──────────────────────────────────────────────┘ Low Address (0x00400000...)

Stack grows DOWN Heap grows UP

↓ ↑

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│ [Stack] ...gap... [Heap] │

└─────────────────────────────┘

3. fork(): The UNIX Way of Creating Processes

Unlike other systems that have “spawn” or “create process” calls, UNIX has fork(): the current process clones itself.

fork() Creates an Almost-Identical Copy

BEFORE fork() AFTER fork()

┌─────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────┐

│ Process (PID=42)│ │ Parent (PID=42) │

│ │ │ fork() returns │

│ Code │ │ child PID (43) │

│ Data │ ═══> └─────────────────┘

│ Heap │ │

│ Stack │ ┌───────┴───────┐

│ FDs │ │ │

└─────────────────┘ v v

┌─────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────┐

│ Parent (PID=42) │ │ Child (PID=43) │

│ Continues... │ │ fork() returns 0│

│ │ │ │

│ Same code │ │ Same code │

│ Same data(COW) │ │ Same data(COW) │

│ Same FDs │ │ Same FDs │

└─────────────────┘ └─────────────────┘

COW = Copy-On-Write: Physical memory is shared until either process writes

Why this design? It’s elegant: creating a process and running a different program are separate operations. This allows the child to:

- Redirect file descriptors before exec

- Change environment, directory, limits

- Set up pipes and IPC before loading new code

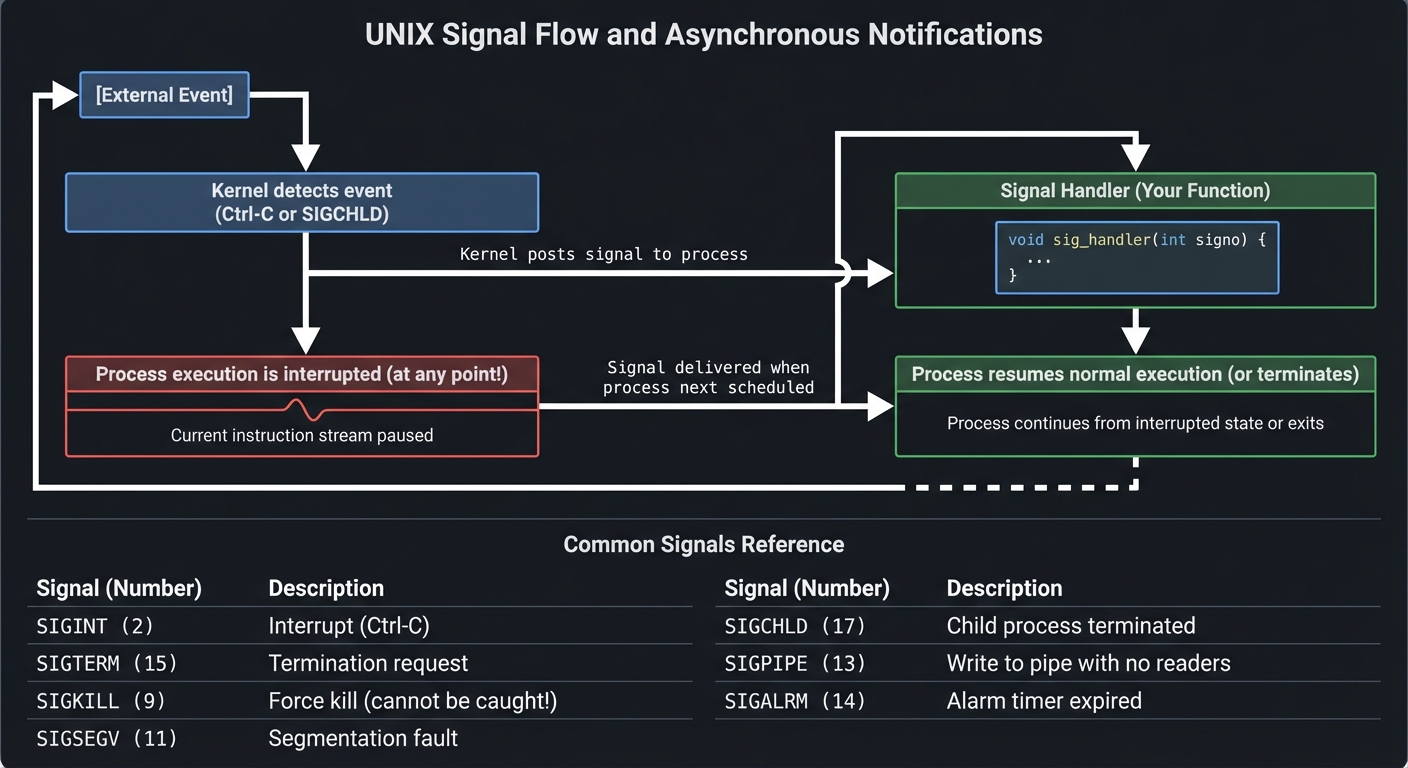

4. Signals: Asynchronous Notifications

Signals are software interrupts—the kernel taps your process on the shoulder and says “hey, deal with this.”

Signal Flow

┌─────────────────┐

[External Event] │ Signal Handler │

│ │ (Your Function) │

v └────────┬────────┘

┌───────────────┐ │

│ Kernel detects│ ────> Kernel posts signal │

│ event (Ctrl-C │ to process │

│ or SIGCHLD) │ v

└───────────────┘ ┌─────────────────┐

│ │ Process resumes │

v │ normal execution│

┌───────────────────┐ │ (or terminates) │

│ Process execution │ ←─── Signal └─────────────────┘

│ is interrupted │ delivered

│ │ when process

│ (at any point!) │ next scheduled

└───────────────────┘

Common Signals:

SIGINT (2) - Interrupt (Ctrl-C)

SIGTERM (15) - Termination request

SIGKILL (9) - Force kill (cannot be caught!)

SIGSEGV (11) - Segmentation fault

SIGCHLD (17) - Child process terminated

SIGPIPE (13) - Write to pipe with no readers

SIGALRM (14) - Alarm timer expired

The Danger: Signal handlers can run at almost ANY point in your code. If you’re in the middle of updating a linked list and a signal fires, your handler might see corrupted data. This is why signals are notoriously tricky.

5. Threads vs. Processes

Processes: Separate Everything Threads: Shared Address Space

┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────────────────────┐

│ Process A │ │ Process B │ │ Process │

│ ┌─────────┐ │ │ ┌─────────┐ │ │ ┌───────┐ ┌───────┐ │

│ │ Memory │ │ │ │ Memory │ │ │ │Thread1│ │Thread2│ ... │

│ │ (own) │ │ │ │ (own) │ │ │ │ Stack │ │ Stack │ │

│ └─────────┘ │ │ └─────────┘ │ │ └───┬───┘ └───┬───┘ │

│ ┌─────────┐ │ │ ┌─────────┐ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ FDs │ │ │ │ FDs │ │ │ └────┬────┘ │

│ │ (own) │ │ │ │ (own) │ │ │ v │

│ └─────────┘ │ │ └─────────┘ │ │ ┌─────────────────┐ │

└─────────────┘ └─────────────┘ │ │ Shared Memory │ │

│ │ │ │ Shared FDs │ │

│ IPC (pipes, │ │ │ Shared Heap │ │

└──── sockets) ────┘ │ └─────────────────┘ │

└─────────────────────────────┘

Process Context Switch: EXPENSIVE (TLB flush, cache miss)

Thread Context Switch: CHEAPER (same address space)

BUT: Threads share memory → Race conditions, deadlocks

Processes isolated → Safer, but communication overhead

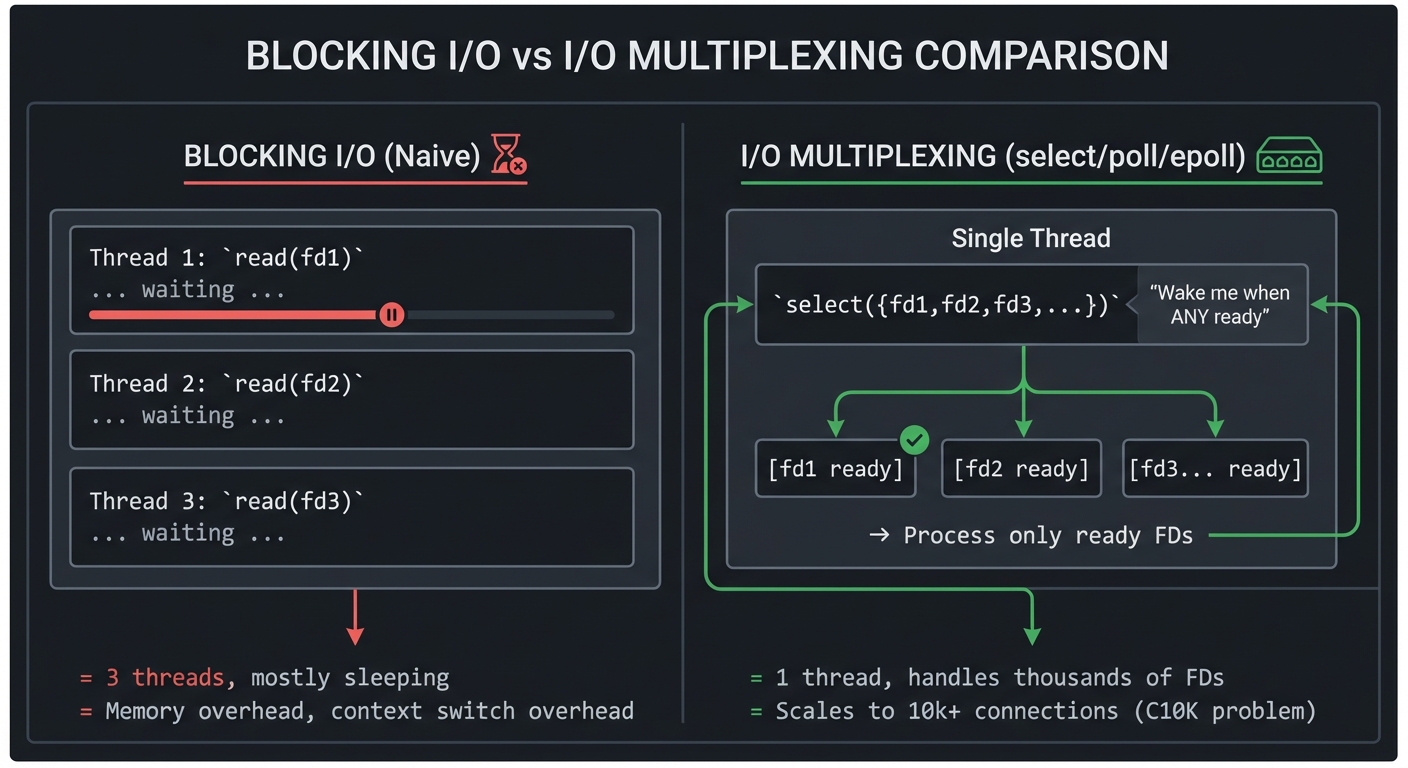

6. I/O Multiplexing: Handling Many Connections

How does a web server handle 10,000 simultaneous connections? Not 10,000 threads—that’s too expensive. Instead: I/O multiplexing.

Blocking I/O (Naive) I/O Multiplexing (select/poll/epoll)

┌─────────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Thread 1: read(fd1) │ │ Single Thread │

│ ... waiting ... │ │ │

├─────────────────────┤ │ ┌─────────────────────────────┐ │

│ Thread 2: read(fd2) │ │ │ select({fd1,fd2,fd3,...}) │ │

│ ... waiting ... │ │ │ "Wake me when ANY ready" │ │

├─────────────────────┤ │ └──────────────┬──────────────┘ │

│ Thread 3: read(fd3) │ │ │ │

│ ... waiting ... │ │ ┌───────────┼───────────┐ │

└─────────────────────┘ │ v v v │

│ [fd1 ready] [fd2 ready] [fd3...] │

= 3 threads, mostly sleeping │ │

= Memory overhead, context │ → Process only ready FDs │

switch overhead │ → Loop back to select() │

└─────────────────────────────────────┘

= 1 thread, handles thousands of FDs

= Scales to 10k+ connections (C10K problem)

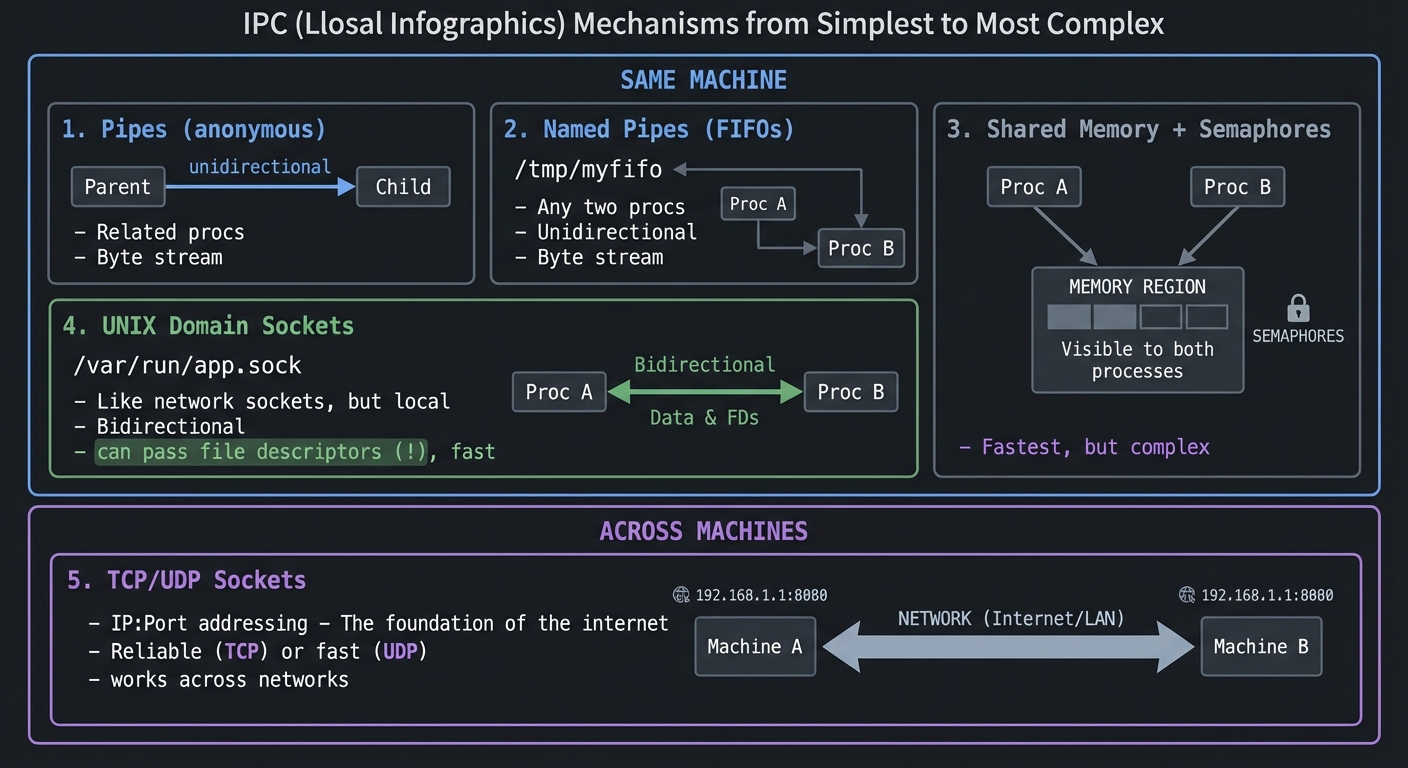

7. Interprocess Communication (IPC) Hierarchy

IPC Mechanisms from Simplest to Most Complex

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ SAME MACHINE │

│ ┌─────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Pipes │ │ Named Pipes │ │ Shared Memory │ │

│ │ (anonymous) │ │ (FIFOs) │ │ + Semaphores │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ Parent ─────> │ │ /tmp/myfifo │ │ ┌─────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ Child │ │ │ │ │ Memory region │ │ │

│ │ │ │ Any two procs │ │ │ visible to both │ │ │

│ │ Unidirectional │ │ Unidirectional │ │ │ processes │ │ │

│ │ Related procs │ │ Unrelated OK │ │ └─────────────────────┘ │ │

│ │ Byte stream │ │ Byte stream │ │ Fastest, but complex │ │

│ └─────────────────┘ └─────────────────┘ └─────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ UNIX Domain Sockets │ │

│ │ /var/run/app.sock - Like network sockets, but local │ │

│ │ Bidirectional, can pass file descriptors (!), fast │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ ACROSS MACHINES │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ TCP/UDP Sockets │ │

│ │ IP:Port addressing - The foundation of the internet │ │

│ │ Reliable (TCP) or fast (UDP), works across networks │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

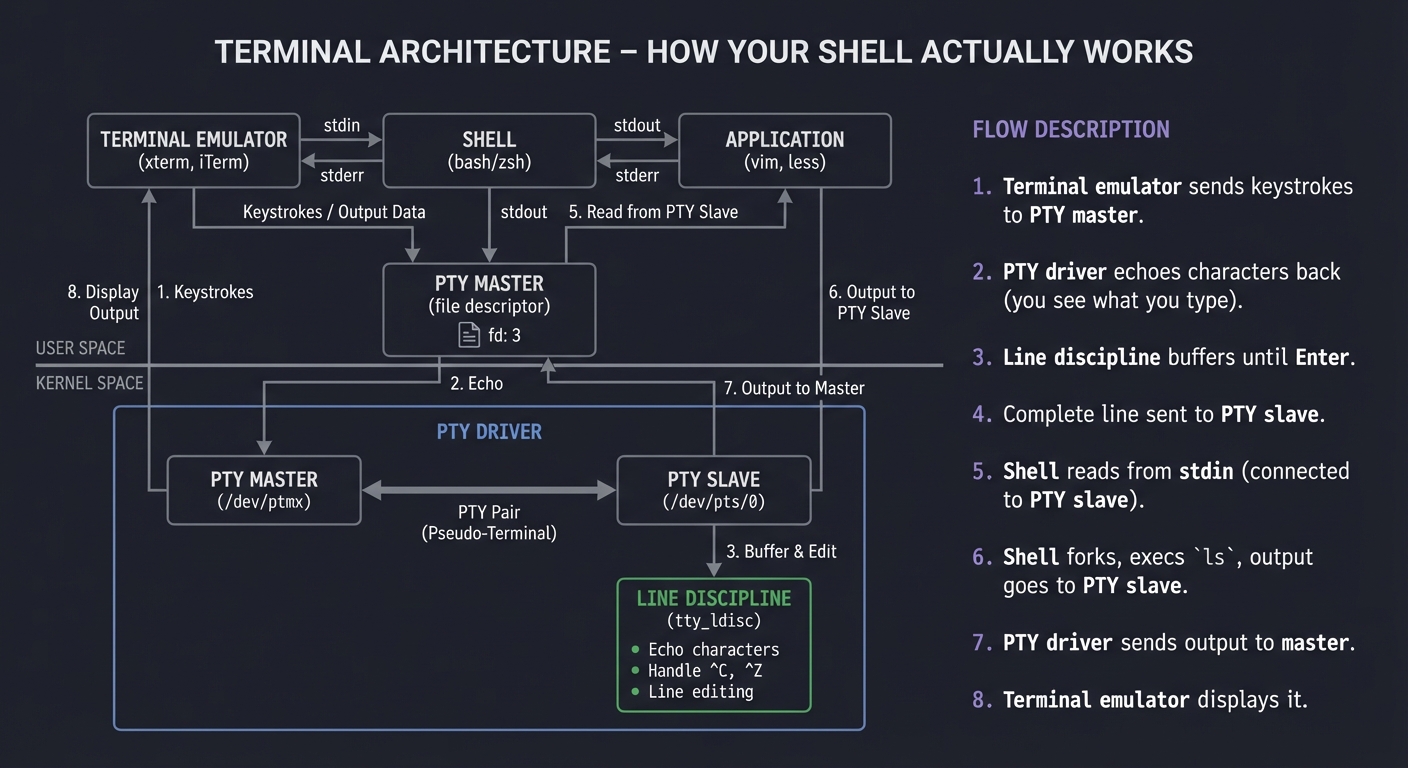

8. The Terminal Subsystem

Terminal Architecture (How Your Shell Actually Works)

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ USER SPACE │

│ ┌────────────────┐ ┌────────────────┐ ┌────────────────┐ │

│ │ Terminal │ │ Shell │ │ Application │ │

│ │ Emulator │←──→│ (bash/zsh) │←──→│ (vim, less) │ │

│ │ (xterm, iTerm) │ │ │ │ │ │

│ └───────┬────────┘ └───────┬────────┘ └───────┬────────┘ │

│ │ │ │ │

│ └──────────────┬──────┴─────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ PTY Master │

│ (file descriptor) │

└─────────────────────────┼──────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

┌─────────────────────────┼──────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ KERNEL SPACE │

│ │ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ PTY Driver │ │

│ │ ┌───────────────┐ ┌───────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ PTY Master │←─────────→│ PTY Slave │ │ │

│ │ │ /dev/ptmx │ │ /dev/pts/0 │ │ │

│ │ └───────────────┘ └───────┬───────┘ │ │

│ │ │ │ │

│ │ ┌───────────┴───────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ Line Discipline │ │ │

│ │ │ (tty_ldisc) │ │ │

│ │ │ - Echo characters │ │ │

│ │ │ - Handle ^C, ^Z │ │ │

│ │ │ - Line editing │ │ │

│ │ └───────────────────────┘ │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

When you type 'ls' and press Enter:

1. Terminal emulator sends keystrokes to PTY master

2. PTY driver echoes characters back (you see what you type)

3. Line discipline buffers until Enter

4. Complete line sent to PTY slave

5. Shell reads from stdin (connected to PTY slave)

6. Shell forks, execs 'ls', output goes to PTY slave

7. PTY driver sends output to master

8. Terminal emulator displays it

Concept Summary Table

This section provides a map of the mental models you will build during these projects.

| Concept Cluster | What You Need to Internalize |

|---|---|

| File Descriptors | Everything is a file. FDs are indices into a per-process table. The abstraction enables composition. |

| Process Model | Processes are isolated by default. fork() clones, exec() replaces. The combination is powerful. |

| Virtual Memory | Each process has its own address space. The kernel maps virtual to physical. Copy-on-write is key. |

| Signals | Asynchronous notifications that interrupt at any point. Signal-safe functions are limited. Use with care. |

| Threads | Shared address space within a process. Cheaper than processes but require synchronization. |

| Synchronization | Mutexes protect data, condition variables signal events, read-write locks optimize read-heavy workloads. |

| I/O Multiplexing | select/poll/epoll let one thread handle thousands of connections efficiently. |

| IPC | Pipes for simple cases, shared memory for speed, sockets for flexibility. Choose wisely. |

| Terminal I/O | PTY pairs, line discipline, canonical vs raw mode. Essential for building shells and editors. |

| Daemon Processes | Background services that survive logout. Double fork, setsid(), proper signal handling. |

Deep Dive Reading by Concept

This section maps each concept to specific book chapters for deeper understanding.

File I/O & File Systems

| Concept | Book & Chapter | Why This Matters |

|---|---|---|

| File descriptors & open/read/write | “APUE” by Stevens — Ch. 3 | The foundation of all UNIX I/O |

| File system structure | “The Linux Programming Interface” by Kerrisk — Ch. 14-18 | Understand inodes, directories, links |

| Buffered vs unbuffered I/O | “APUE” by Stevens — Ch. 5 | Know when stdio helps and when it hurts |

| Low-level I/O details | “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” — Ch. 10 | See how the kernel implements it |

Process Management

| Concept | Book & Chapter | Why This Matters |

|---|---|---|

| fork/exec/wait | “APUE” by Stevens — Ch. 7, 8 | The UNIX process model |

| Process groups & sessions | “APUE” by Stevens — Ch. 9 | Essential for job control |

| Memory layout | “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” — Ch. 9 | Virtual memory explained |

| The kernel view | “Linux Kernel Development” by Love — Ch. 3, 5 | See it from the other side |

Signals

| Concept | Book & Chapter | Why This Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Signal fundamentals | “APUE” by Stevens — Ch. 10 | The complete treatment |

| Reliable signals | “The Linux Programming Interface” — Ch. 20-22 | Avoid the pitfalls |

| Signal-safe programming | “APUE” by Stevens — Ch. 10.6 | What you can/can’t do in handlers |

Threads & Synchronization

| Concept | Book & Chapter | Why This Matters |

|---|---|---|

| POSIX threads basics | “APUE” by Stevens — Ch. 11, 12 | Creating and managing threads |

| Synchronization | “The Linux Programming Interface” — Ch. 29-33 | Mutexes, conditions, barriers |

| Lock-free techniques | “Rust Atomics and Locks” by Mara Bos | Modern concurrency patterns |

Advanced I/O & IPC

| Concept | Book & Chapter | Why This Matters |

|---|---|---|

| select/poll/epoll | “The Linux Programming Interface” — Ch. 63 | I/O multiplexing in depth |

| Pipes & FIFOs | “APUE” by Stevens — Ch. 15 | Simple IPC |

| System V IPC | “APUE” by Stevens — Ch. 15 | Shared memory, semaphores, queues |

| UNIX domain sockets | “The Linux Programming Interface” — Ch. 57 | Local socket IPC |

Network Programming

| Concept | Book & Chapter | Why This Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Socket API | “UNIX Network Programming, Vol. 1” by Stevens — Ch. 1-8 | The definitive reference |

| TCP/IP internals | “TCP/IP Illustrated, Vol. 1” by Stevens — All | Protocol deep dive |

| High-performance servers | “The Linux Programming Interface” — Ch. 59-61 | Real-world patterns |

Terminal I/O & Daemons

| Concept | Book & Chapter | Why This Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Terminal drivers | “APUE” by Stevens — Ch. 18 | Line discipline, modes |

| Pseudo terminals | “APUE” by Stevens — Ch. 19 | PTY programming |

| Daemon processes | “APUE” by Stevens — Ch. 13 | Background services |

Quick Start: Your First 48 Hours

Feeling overwhelmed? Start here instead of reading everything:

Day 1 (4 hours):

- Read only the “File Descriptors” and “Processes” sections above

- Set up your development environment (gcc, make, strace)

- Start Project 1 - just get a basic file copy working

- Run

strace ./mycp source destand look at the system calls

Day 2 (4 hours):

- Add error handling to your file copy (what if source doesn’t exist?)

- Compare your output with

strace cp source dest - Read “The Core Question You’re Answering” for Project 1

- Try copying a large file (100MB) and time it with different buffer sizes

End of Weekend: You now understand that:

- Everything goes through file descriptors

- System calls are the kernel interface

- Buffer size matters for performance

- Error handling is not optional

That’s the foundation. Everything else builds on this.

Next Steps:

- If it clicked: Continue to Project 2 (stat and file information)

- If confused: Re-read Project 1’s “Concepts You Must Understand First”

- If frustrated: Try Chapter 3 of Stevens’ APUE with the example code

Recommended Learning Path

Path 1: The Systems Programmer (Recommended Start)

Best for: Those aiming for systems programming roles, kernel development, or infrastructure engineering

- Start with Project 1 (File Copy) - Understand file descriptors and the basic I/O model

- Then Project 2 (File Info) - Learn the stat family and file metadata

- Then Project 4 (Shell) - Master fork/exec/wait through building a shell

- Then Project 6 (Signal Handler) - Understand asynchronous events

- Then Project 8 (Thread Pool) - Concurrency fundamentals

- Then Project 11 (Event Server) - I/O multiplexing at scale

Path 2: The Networking Engineer

Best for: Those building network services, distributed systems, or backend infrastructure

- Start with Project 1 (File Copy) - Still foundational

- Then Project 12 (Echo Server) - Socket programming basics

- Then Project 13 (HTTP Server) - Protocol implementation

- Then Project 11 (Event Server) - Handle thousands of connections

- Then Project 14 (IPC Hub) - Local communication patterns

Path 3: The DevOps/SRE Path

Best for: Those managing production systems, debugging issues, writing automation

- Start with Project 5 (Process Monitor) - Understanding /proc filesystem

- Then Project 9 (Daemon) - How services actually work

- Then Project 4 (Shell) - What happens when you run commands

- Then Project 15 (Terminal Emulator) - The terminal magic revealed

- Then Project 10 (Log Watcher) - File system events and monitoring

Path 4: The Completionist

Best for: Those building a complete understanding of UNIX systems

Phase 1: Foundation (Weeks 1-4)

- Project 1: File Copy Utility

- Project 2: File Information Tool

- Project 3: Directory Walker

Phase 2: Processes (Weeks 5-8)

- Project 4: Simple Shell

- Project 5: Process Monitor

- Project 6: Signal Handler

Phase 3: Concurrency (Weeks 9-12)

- Project 7: Producer-Consumer

- Project 8: Thread Pool

- Project 9: Daemon Service

Phase 4: Advanced I/O (Weeks 13-16)

- Project 10: Log Watcher

- Project 11: Event-Driven Server

- Project 12: Echo Server

Phase 5: Integration (Weeks 17-24)

- Project 13: HTTP Server

- Project 14: IPC Message Hub

- Project 15: Terminal Emulator

- Project 16: Database Engine

- Project 17: Complete Shell (Final Project)

Testing & Debugging Strategies

UNIX systems programming requires rigorous testing and debugging. Here’s how to verify your implementations work correctly.

Essential Testing Tools

1. strace - System Call Tracer

# See every system call your program makes

$ strace ./myprogram

# Count system calls (find inefficiencies)

$ strace -c ./myprogram

# Trace specific calls only

$ strace -e open,read,write ./myprogram

# Trace a running process

$ strace -p <PID>

Use cases: Understand what your code does, find performance bottlenecks, debug “it doesn’t work” issues

2. gdb - GNU Debugger

# Compile with debug symbols

$ gcc -g -o myprogram myprogram.c

# Basic debugging session

$ gdb ./myprogram

(gdb) break main

(gdb) run

(gdb) next # Step over

(gdb) step # Step into

(gdb) print variable

(gdb) backtrace # Show call stack

Use cases: Segmentation faults, logic errors, understanding control flow

3. valgrind - Memory Debugger

# Detect memory leaks and invalid access

$ valgrind --leak-check=full ./myprogram

# Detect threading issues

$ valgrind --tool=helgrind ./myprogram

Use cases: Memory leaks, use-after-free, race conditions

4. ltrace - Library Call Tracer

# See library calls (malloc, printf, etc.)

$ ltrace ./myprogram

5. lsof - List Open Files

# See all files/sockets opened by a process

$ lsof -p <PID>

# Find who's using a port

$ lsof -i :8080

Verification Checklist Per Project

For each project, verify:

✅ Correctness:

- Does it produce the expected output?

- Test with edge cases (empty files, huge files, special characters)

- Compare against standard UNIX tools (cp, ls, etc.)

✅ Error Handling:

- What if the file doesn’t exist?

- What if you run out of memory?

- What if a system call is interrupted (EINTR)?

- Test with

ulimitto restrict resources

✅ Resource Cleanup:

- Run with

valgrind- zero memory leaks? - All file descriptors closed? (

lsof -p <PID>after exit) - Threads properly joined?

✅ Performance:

- Compare with standard tools (time your program vs.

cp) - Run

strace -c- reasonable number of syscalls? - Profile with

perffor hot spots

Common Debugging Scenarios

Scenario 1: “Segmentation Fault”

# Get a backtrace

$ gdb ./myprogram

(gdb) run

Program received signal SIGSEGV

(gdb) backtrace

# Look for NULL dereferences, buffer overruns

Scenario 2: “It Hangs”

# Attach to running process

$ gdb -p <PID>

(gdb) thread apply all backtrace

# Look for deadlocks, infinite loops

Scenario 3: “Memory Leak”

$ valgrind --leak-check=full --show-leak-kinds=all ./myprogram

# Every malloc must have a matching free

Scenario 4: “Race Condition”

$ valgrind --tool=helgrind ./myprogram

# Look for data races on shared variables

Scenario 5: “File Descriptor Leak”

# Before running

$ ls -l /proc/<PID>/fd | wc -l

# After operation

$ ls -l /proc/<PID>/fd | wc -l

# Numbers should be the same

Testing Best Practices

1. Test the Happy Path First

- Get basic functionality working with normal inputs

- Example: Copy a small text file

2. Then Test Edge Cases

- Empty files (0 bytes)

- Large files (> memory size)

- Files you don’t have permission to read

- Non-existent files

- Symbolic links

- Directories (when expecting files)

3. Test Error Paths

# Simulate out of memory

$ ulimit -v 10000 # Limit virtual memory

$ ./myprogram

# Simulate out of file descriptors

$ ulimit -n 10

$ ./myprogram

# Test with read-only filesystem

$ mkdir readonly && chmod 444 readonly

$ ./myprogram -o readonly/output

4. Fuzz Testing

- Feed random/malformed input

- See what breaks

- Fix crashes and undefined behavior

5. Integration Testing

# Test with real workloads

$ ./myserver &

$ SERVER_PID=$!

$ ab -n 10000 -c 100 http://localhost:8080/

$ kill $SERVER_PID

Measuring Success

Each project should pass these tests:

| Test Type | What It Verifies | Tool |

|---|---|---|

| Unit tests | Core logic works | Custom test harness |

| Memory safety | No leaks, no invalid access | valgrind |

| System call efficiency | Minimal syscalls | strace -c |

| Concurrency correctness | No races, no deadlocks | helgrind, tsan |

| Performance | Comparable to standard tools | time, perf |

| Resource cleanup | All FDs/memory freed | lsof, /proc |

The “Production-Ready” Standard

Your code is production-ready when:

- Zero compiler warnings (

gcc -Wall -Wextra -Werror) - Zero valgrind errors on all test cases

- Handles EINTR properly (system calls interrupted by signals)

- Graceful error messages (not just “Error: -1”)

- Resource limits respected (doesn’t assume infinite memory/FDs)

- Signal-safe (if using signals, only async-signal-safe functions)

- Thread-safe (if multithreaded, proper synchronization)

Remember: Production code is 90% error handling. Your educational implementations should be too.

Project List

The following projects guide you from basic file I/O to building complete systems. Each project teaches specific UNIX concepts through hands-on implementation.

Project 1: High-Performance File Copy Utility

- File:

mycp.c - Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Go

- Coolness Level: Level 2 - Practical but Foundational

- Business Potential: Level 1 - Resume Gold (Educational)

- Difficulty: Level 2 - Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: File I/O, System Calls

- Software or Tool: Core UNIX utilities (cp)

- Main Book: “Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment” by Stevens — Ch. 3

What you’ll build: A file copy utility that uses low-level system calls (open, read, write, close) with configurable buffer sizes and performance measurement.

Why it teaches UNIX: This is the “Hello World” of systems programming. Every UNIX application ultimately does I/O through these calls. You’ll understand file descriptors, blocking I/O, and the real cost of system calls.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Choosing buffer size → Understanding I/O performance tradeoffs

- Handling partial reads/writes → Learning that read() can return less than requested

- Proper error handling → Every system call can fail; you must check

- File permissions and modes → The third argument to open()

Real World Outcome

What you will see:

- A working copy utility: Copies any file correctly, byte-for-byte identical

- Performance comparison: Measure time with different buffer sizes

- strace output: See exactly which system calls your program makes

Command Line Outcome Example:

# 1. Create a test file

$ dd if=/dev/urandom of=testfile bs=1M count=100

100+0 records in

100+0 records out

104857600 bytes (105 MB) copied, 0.542 s, 193 MB/s

# 2. Run your copy utility

$ ./mycp testfile copyfile

mycp: copied 104857600 bytes in 0.089 seconds (1.1 GB/s)

# 3. Verify the copy is identical

$ md5sum testfile copyfile

7f9e5d1a2b3c4d5e6f7a8b9c0d1e2f3a testfile

7f9e5d1a2b3c4d5e6f7a8b9c0d1e2f3a copyfile

# 4. TEST: Different buffer sizes

$ ./mycp -b 1 testfile copy1 # 1 byte buffer

mycp: copied 104857600 bytes in 47.3 seconds (2.1 MB/s) # SLOW!

$ ./mycp -b 4096 testfile copy2 # 4KB buffer

mycp: copied 104857600 bytes in 0.21 seconds (476 MB/s)

$ ./mycp -b 65536 testfile copy3 # 64KB buffer

mycp: copied 104857600 bytes in 0.089 seconds (1.1 GB/s)

$ ./mycp -b 1048576 testfile copy4 # 1MB buffer

mycp: copied 104857600 bytes in 0.087 seconds (1.1 GB/s) # Diminishing returns

# 5. Trace system calls

$ strace -c ./mycp testfile copyfile

% time calls syscall

---------- ------ --------

50.21 1601 read

49.12 1601 write

0.34 3 openat

0.18 2 close

0.15 1 fstat

The Core Question You’re Answering

“What is the actual cost of a system call, and how does buffer size affect I/O performance?”

Before you write any code, sit with this question. Each read() and write() crosses the user-kernel boundary—there’s a context switch, privilege level change, and cache pollution. But larger buffers mean more memory. The sweet spot depends on the storage device, OS, and workload.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- File Descriptors

- What number does

open()return? Why that number? - What happens to file descriptors across

fork()? - Book Reference: “APUE” Ch. 3.2 - Stevens

- What number does

- The open() System Call

- What are O_RDONLY, O_WRONLY, O_CREAT, O_TRUNC?

- What is the

mode_targument and when is it used? - Book Reference: “APUE” Ch. 3.3

- Partial Reads and Writes

- Why might

read(fd, buf, 4096)return only 1000? - What must you do when

write()returns less than requested? - Book Reference: “APUE” Ch. 3.6

- Why might

- Error Handling with errno

- What is

errnoand when is it valid? - What does

perror()do vsstrerror()?

- What is

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Buffer Management

- Where should the buffer be allocated—stack or heap?

- What if the file is smaller than the buffer?

- Error Paths

- What if the source file doesn’t exist?

- What if you don’t have permission to write the destination?

- What if you run out of disk space mid-copy?

- Edge Cases

- Should you handle copying a file onto itself?

- What about symbolic links—follow them or copy the link?

Thinking Exercise

Trace Through a System Call

Before coding, trace what happens when you call read(fd, buf, 4096):

User Space Kernel Space

│

│ read(3, buf, 4096)

│

└──────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

│ 1. Trap into kernel (syscall instruction)

│ 2. Save user registers

│ 3. Look up fd 3 in process's fd table

│ 4. Find the file object (inode, position)

│ 5. Check if data in page cache

│ 6. If not: schedule disk I/O, sleep

│ 7. If yes: copy from page cache to buf

│ 8. Update file position

│ 9. Restore user registers

│ 10. Return to user space

│

└──────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

│ Returns: number of bytes read (or -1 on error)

Questions while tracing:

- Why is step 6 expensive?

- What makes step 7 fast?

- Why does buffer size matter given step 7?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

Prepare to answer these:

- “What’s the difference between

read()andfread()?” - “Why might you prefer

open()overfopen()?” - “How would you efficiently copy a 10GB file?”

- “What happens if

read()is interrupted by a signal?” - “Explain the O_DIRECT flag and when you’d use it.”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Basic Structure Your main loop reads from source, writes to destination, until read returns 0 (EOF).

Hint 2: The Read Loop Pattern You need to handle partial reads. The pattern is: read into buffer, then write everything that was read. Check return values.

Hint 3: Handling Partial Writes

// Pseudocode for robust write

while (bytes_to_write > 0) {

written = write(fd, buf + offset, bytes_to_write)

if (written < 0) {

if (errno == EINTR) continue // Interrupted, retry

// Handle error

}

bytes_to_write -= written

offset += written

}

Hint 4: Measuring Performance

Use clock_gettime(CLOCK_MONOTONIC, &ts) for accurate timing. Print bytes/second at the end.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| File I/O fundamentals | “APUE” by Stevens | Ch. 3 |

| System call mechanics | “Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective” | Ch. 8, 10 |

| I/O performance | “The Linux Programming Interface” by Kerrisk | Ch. 13 |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem 1: “Copy works but destination has wrong size”

- Why: Not handling partial writes, or not writing all bytes read

- Fix: Use a write loop that handles partial writes

- Quick test:

ls -l source destand compare sizes

Problem 2: “Program hangs on large files”

- Why: Possibly using 1-byte buffer

- Debug: Run with

strace -cto count syscalls - Fix: Use at least 4KB buffer

Problem 3: “Permission denied on destination”

- Why: Missing mode argument to

open()with O_CREAT - Fix:

open(dest, O_WRONLY|O_CREAT|O_TRUNC, 0644)

Testing Your Copy:

# Create test files of various sizes

$ dd if=/dev/zero of=tiny bs=1 count=1

$ dd if=/dev/zero of=small bs=1K count=10

$ dd if=/dev/zero of=medium bs=1M count=10

$ dd if=/dev/zero of=large bs=1M count=100

# Copy each and verify

$ for f in tiny small medium large; do

./mycp $f ${f}_copy && \

cmp $f ${f}_copy && echo "$f: OK" || echo "$f: FAILED"

done

Project 2: Advanced File Information Tool

- File:

mystat.c - Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Go

- Coolness Level: Level 2 - Practical but Foundational

- Business Potential: Level 1 - Resume Gold

- Difficulty: Level 2 - Intermediate

- Knowledge Area: File System, Metadata

- Software or Tool: stat, ls -l

- Main Book: “Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment” by Stevens — Ch. 4

What you’ll build: A comprehensive file information tool that displays all metadata available from the stat structure—permissions, ownership, timestamps, inode numbers, block counts, and file type.

Why it teaches UNIX: Understanding the stat structure reveals how UNIX filesystems actually store file metadata. This is essential for backup tools, file managers, and security applications.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Parsing the mode field → Extracting file type and permission bits

- Resolving user/group names → Connecting UIDs to usernames

- Handling symbolic links → stat vs lstat behavior

- Understanding timestamps → atime, mtime, ctime meanings

Real World Outcome

What you will see:

- Complete file metadata: More detailed than

statcommand - Human-readable output: Permissions shown as rwxr-xr-x

- Type detection: Regular file, directory, symlink, device, etc.

Command Line Outcome Example:

# 1. Check a regular file

$ ./mystat /bin/ls

File: /bin/ls

Type: regular file

Size: 142144 bytes (139 KiB)

Blocks: 280 (of 512 bytes each)

IO Block: 4096

Device: 8,1 (major,minor)

Inode: 131073

Links: 1

Access: -rwxr-xr-x (0755)

Uid: root (0)

Gid: root (0)

Access Time: 2024-03-15 10:23:45.123456789 -0700

Modify Time: 2023-11-10 08:15:32.000000000 -0800

Change Time: 2024-01-02 14:30:00.123456789 -0800

# 2. Check a directory

$ ./mystat /tmp

File: /tmp

Type: directory

Size: 4096 bytes (4 KiB)

...

Access: drwxrwxrwt (1777) # Note the sticky bit!

# 3. Check a symbolic link (with lstat)

$ ./mystat -L /usr/bin/python3

File: /usr/bin/python3 -> python3.11

Type: symbolic link

Size: 10 bytes # Size of the link itself

Link Target: python3.11

# 4. Check a block device

$ ./mystat /dev/sda

File: /dev/sda

Type: block special

Device: 8,0

...

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How does UNIX store and represent file metadata, and what’s the difference between a file’s data and its attributes?”

Every file has two parts: the data (contents) and the inode (metadata). Understanding the inode structure explains why hard links work, why mv is instant within a filesystem, and why permissions are per-file, not per-name.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- The stat Structure

- What fields does

struct statcontain? - What’s the difference between

stat()andlstat()? - Book Reference: “APUE” Ch. 4.2

- What fields does

- File Types in UNIX

- Regular file, directory, character device, block device, FIFO, socket, symbolic link

- How are these encoded in

st_mode? - Book Reference: “APUE” Ch. 4.3

- Permission Bits

- What do r, w, x mean for files vs directories?

- What are setuid, setgid, and sticky bits?

- Book Reference: “APUE” Ch. 4.5-4.6

- The Three Timestamps

- Access time (atime), modification time (mtime), change time (ctime)

- Which operations update which timestamps?

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Output Format

- Should you match

statcommand format or design your own? - How to display times—Unix epoch or human-readable?

- Should you match

- Symlink Handling

- Should you follow symlinks by default or not?

- How to show both link info and target info?

- Error Messages

- How to handle permission denied?

- How to handle non-existent files?

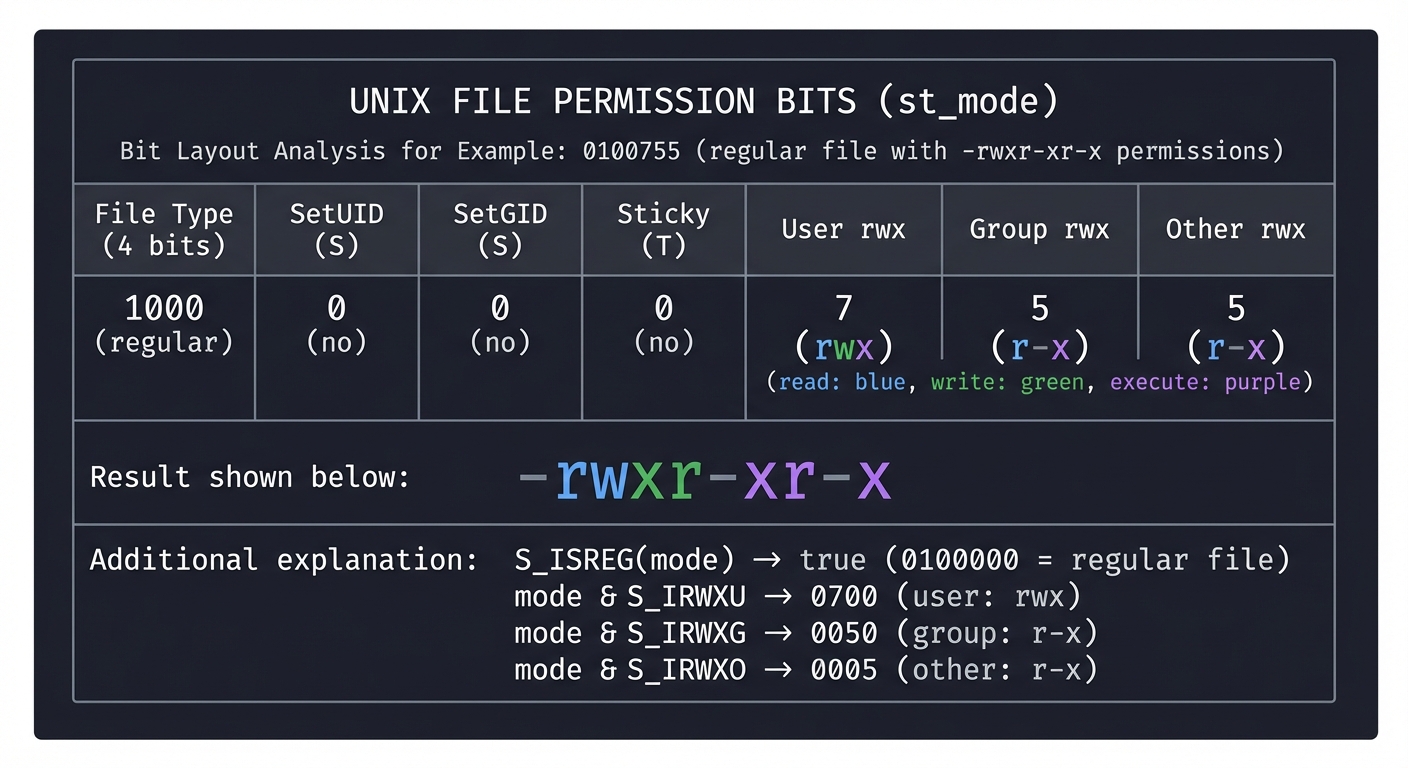

Thinking Exercise

Decode a Mode Value

Given st_mode = 0100755 (octal), decode it:

st_mode bits:

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ File Type │ SetUID │ SetGID │ Sticky │ User │Group│Other│

│ (4 bits) │ S │ S │ T │ rwx │ rwx │ rwx │

├───────────────┼────────┼────────┼────────┼──────┼─────┼─────┤

│ 1000 │ 0 │ 0 │ 0 │ 7 │ 5 │ 5 │

│ (regular) │ (no) │ (no) │ (no) │ rwx │ r-x │ r-x │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Result: -rwxr-xr-x

S_ISREG(mode) → true (0100000 = regular file)

mode & S_IRWXU → 0700 (user: rwx)

mode & S_IRWXG → 0050 (group: r-x)

mode & S_IRWXO → 0005 (other: r-x)

Questions:

- What would

st_mode = 040755represent? - What about

st_mode = 0104755?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “What’s the difference between stat() and lstat()?”

- “How are hard links implemented at the filesystem level?”

- “Why does

rmon a file sometimes not free disk space?” - “What’s the sticky bit and when would you use it?”

- “How would you find all setuid programs on a system?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Getting Started

Call stat() or lstat() on the file path. Check the return value for errors.

Hint 2: File Type Detection

Use the macros: S_ISREG(mode), S_ISDIR(mode), S_ISLNK(mode), etc.

Hint 3: Permission String

// Pseudocode for permission string

char perms[11];

perms[0] = type_char(mode); // - d l c b p s

perms[1] = (mode & S_IRUSR) ? 'r' : '-';

perms[2] = (mode & S_IWUSR) ? 'w' : '-';

perms[3] = (mode & S_IXUSR) ? 'x' : '-'; // or 's' if setuid

// ... continue for group and other

Hint 4: Username Lookup

Use getpwuid(st.st_uid) to get the username from UID. Returns NULL if not found.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| File metadata | “APUE” by Stevens | Ch. 4 |

| Filesystem structure | “The Linux Programming Interface” | Ch. 14-18 |

| Inode details | “Understanding the Linux Kernel” | Ch. 12 |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem 1: “Always shows ‘regular file’ for symlinks”

- Why: Using

stat()instead oflstat() - Fix: Use

lstat()to get info about the link itself

Problem 2: “Permission bits wrong for special files”

- Why: Not handling setuid/setgid/sticky in permission string

- Fix: Check

S_ISUID,S_ISGID,S_ISVTXand modify x to s/S or t/T

Problem 3: “getpwuid returns NULL”

- Why: User doesn’t exist (e.g., file from another system)

- Fix: Display numeric UID when lookup fails

Project 3: Recursive Directory Walker

- File:

myfind.c - Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Go

- Coolness Level: Level 3 - Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: Level 2 - Micro-SaaS (specialized search tools)

- Difficulty: Level 3 - Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Filesystems, Recursion, Directory Operations

- Software or Tool: find, tree, du

- Main Book: “Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment” by Stevens — Ch. 4

What you’ll build: A recursive directory traversal tool that walks entire directory trees, reporting files, computing sizes, and optionally filtering by criteria (name pattern, size, type).

Why it teaches UNIX: Directory traversal is fundamental to backup programs, search tools, synchronization utilities, and build systems. You’ll understand opendir/readdir, path construction, and handling of filesystem cycles.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Building paths correctly → Avoiding buffer overflows in path construction

- Handling cycles → Symbolic links can create loops

- Efficient traversal → nftw() vs manual recursion

- Filtering and matching → Pattern matching with fnmatch()

Real World Outcome

What you will see:

- Directory tree display: Like

treecommand - Size computation: Like

ducommand - File search: Like simplified

findcommand

Command Line Outcome Example:

# 1. Basic tree display

$ ./myfind --tree /usr/include

/usr/include

├── assert.h

├── complex.h

├── errno.h

├── linux/

│ ├── capability.h

│ ├── fs.h

│ └── types.h

├── sys/

│ ├── socket.h

│ ├── stat.h

│ └── types.h

└── unistd.h

4 directories, 10 files

# 2. Disk usage mode

$ ./myfind --du /var/log

12K /var/log/apt

4K /var/log/apt/history.log

8K /var/log/apt/term.log

256K /var/log/journal

1.2M /var/log

Total: 1.2M in 23 files, 5 directories

# 3. Find files matching pattern

$ ./myfind --name "*.h" /usr/include | head -5

/usr/include/assert.h

/usr/include/complex.h

/usr/include/errno.h

/usr/include/features.h

/usr/include/float.h

# 4. Find files larger than 1MB

$ ./myfind --size +1M /usr

/usr/lib/libc.so.6

/usr/lib/libLLVM-14.so.1

/usr/bin/clang

...

# 5. Handle symbolic link cycle gracefully

$ ln -s . loop

$ ./myfind --tree .

.

├── file.txt

└── loop -> . (symlink, skipping to avoid cycle)

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do you traverse an entire filesystem efficiently while handling all the edge cases (permissions, symlinks, mount points)?”

This question underlies every backup tool, search utility, and file synchronizer ever written. The naive approach (recursion with string concatenation) fails on deep trees and cyclic links.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Directory as a File

- A directory is a file containing name→inode mappings

- What does opendir/readdir/closedir return?

- Book Reference: “APUE” Ch. 4.21-4.22

- Path Construction

- How to join directory path with filename?

- Maximum path length (PATH_MAX)

- Book Reference: “APUE” Ch. 4.14

- Symbolic Link Handling

- When to follow vs. when to skip?

- How to detect cycles?

- nftw() vs Manual Recursion

- What does nftw() provide?

- When would you prefer manual control?

- Book Reference: “APUE” Ch. 4.22

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Recursion Strategy

- Use actual recursion or maintain a work queue?

- How deep can the call stack go?

- Memory Management

- How to handle paths—static buffer or malloc?

- How to track visited inodes for cycle detection?

- Error Handling

- What if you can’t read a directory (permission)?

- What if a file disappears mid-traversal (TOCTOU)?

Thinking Exercise

Model the Directory Structure

Consider this filesystem:

/home/user/

├── file1.txt (inode 100)

├── subdir/ (inode 101)

│ └── file2.txt (inode 102)

├── link1 -> subdir (symlink, inode 103)

└── hardlink.txt (inode 100, same as file1.txt!)

What happens if you:

1. Traverse without following symlinks?

2. Follow symlinks but don't track inodes?

3. Count bytes for hardlink.txt—double count or not?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “How would you find all files modified in the last 24 hours?”

- “How does

duavoid counting hardlinked files twice?” - “What’s the difference between depth-first and breadth-first traversal for filesystems?”

- “How would you make a parallel directory walker?”

- “What is a TOCTOU race in filesystem operations?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Basic Structure

Open directory with opendir(), loop with readdir(), skip “.” and “..”, recurse on directories, close with closedir().

Hint 2: Path Building

// Safe path construction

char path[PATH_MAX];

int len = snprintf(path, sizeof(path), "%s/%s", dir, entry->d_name);

if (len >= sizeof(path)) {

// Path too long!

}

Hint 3: Using nftw()

// nftw callback signature

int callback(const char *fpath, const struct stat *sb,

int typeflag, struct FTW *ftwbuf) {

// typeflag: FTW_F (file), FTW_D (directory), etc.

// ftwbuf->level: depth in tree

}

nftw(path, callback, max_fds, flags);

Hint 4: Cycle Detection Track (device, inode) pairs in a hash set. Before entering a directory, check if already visited.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Directory operations | “APUE” by Stevens | Ch. 4.21-4.22 |

| nftw() details | “The Linux Programming Interface” | Ch. 18 |

| Filesystem internals | “Understanding the Linux Kernel” | Ch. 12 |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem 1: “Crashes on deep directory trees”

- Why: Stack overflow from recursion

- Fix: Use iterative approach with explicit stack, or increase stack size

Problem 2: “Infinite loop with symlinks”

- Why: Following symlinks without cycle detection

- Fix: Use

FTW_PHYSflag with nftw(), or track visited inodes

Problem 3: “Wrong sizes reported”

- Why: Not using lstat() for symlinks, or double-counting hardlinks

- Fix: Use lstat(), track (dev, ino) pairs for hardlink dedup

Project 4: Complete Shell Implementation

- File:

mysh.c - Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust (with unsafe blocks)

- Coolness Level: Level 4 - Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: Level 1 - Resume Gold

- Difficulty: Level 4 - Expert

- Knowledge Area: Process Control, Signals, Job Control

- Software or Tool: bash, sh, dash

- Main Book: “Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment” by Stevens — Ch. 7, 8, 9

What you’ll build: A functional UNIX shell with command execution, pipelines, I/O redirection, background jobs, and basic job control (Ctrl-C, Ctrl-Z).

Why it teaches UNIX: The shell is the textbook example of process control. You’ll implement fork/exec/wait, signal handling, process groups, and pipeline construction. This project alone covers chapters 7-9 of Stevens.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Pipeline construction → Creating pipes, forking, connecting file descriptors

- Job control → Process groups, sessions, controlling terminal

- Signal handling → SIGCHLD, SIGINT, SIGTSTP in parent vs child

- Parsing → Handling quotes, escapes, variables

Real World Outcome

What you will see:

- Interactive shell: Prompt, execute commands, show results

- Pipelines:

ls | grep foo | wc -lworks - Redirection:

cmd > file,cmd < file,cmd 2>&1 - Background jobs:

cmd &with job table - Job control: Ctrl-C interrupts, Ctrl-Z stops, fg/bg resume

Command Line Outcome Example:

# 1. Start your shell

$ ./mysh

mysh>

# 2. Basic command execution

mysh> echo hello world

hello world

mysh> ls -la

total 48

drwxr-xr-x 5 user user 4096 Mar 15 10:00 .

...

# 3. Pipelines

mysh> cat /etc/passwd | grep root | cut -d: -f1

root

mysh> ls -la | sort -k5 -n | tail -5

-rw-r--r-- 1 user user 1024 Mar 14 09:00 small.txt

-rw-r--r-- 1 user user 4096 Mar 15 10:00 medium.txt

...

# 4. I/O Redirection

mysh> echo "hello" > output.txt

mysh> cat < output.txt

hello

mysh> ls nosuchfile 2>&1 | grep -i "no such"

ls: cannot access 'nosuchfile': No such file or directory

# 5. Background jobs

mysh> sleep 10 &

[1] 12345

mysh> sleep 20 &

[2] 12346

mysh> jobs

[1] Running sleep 10

[2] Running sleep 20

# 6. Job control

mysh> sleep 100

^Z

[1]+ Stopped sleep 100

mysh> bg

[1]+ sleep 100 &

mysh> fg

sleep 100

^C

mysh>

# 7. Exit

mysh> exit

$

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How does the shell coordinate multiple processes, connect their inputs and outputs, and manage them as jobs while the user interacts with the terminal?”

The shell is the conductor of an orchestra of processes. Understanding this teaches you everything about UNIX process management that you’ll need for any systems programming.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- fork/exec/wait Pattern

- Why are these separate system calls?

- What does each exec variant do (execl, execv, execvp)?

- Book Reference: “APUE” Ch. 8

- Process Groups and Sessions

- What’s a process group? Why do they exist?

- What’s a session? What’s a controlling terminal?

- Book Reference: “APUE” Ch. 9

- File Descriptor Manipulation

- dup(), dup2(), and their role in redirection

- How pipes connect processes

- Book Reference: “APUE” Ch. 3.12, 15.2

- Signal Handling for Shells

- SIGCHLD—child process status changed

- SIGINT, SIGTSTP—keyboard interrupts

- When should the shell ignore vs handle these?

- Book Reference: “APUE” Ch. 10

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Process Structure

- Does each pipeline stage fork from the shell, or from the previous stage?

- Who creates the pipes?

- Terminal Control

- Which process should receive Ctrl-C?

- How do you give the terminal to a foreground job?

- Job Tracking

- How to track running/stopped jobs?

- When to reap zombies vs wait for foreground?

Thinking Exercise

Trace Pipeline Execution

For command ls | sort | head, trace process creation:

Shell (pid 100, pgid 100, sid 100)

│

├─ fork() ─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ │

│ v

│ ┌────────────────────┐

│ 1. Create pipe1: [read_fd, write_fd] │ Child1 (pid 101) │

│ 2. fork() for ls │ - setpgid(0, 101) │

│ 3. In child: dup2(pipe1_write, STDOUT) │ - close pipe read │

│ close unused pipe ends │ - exec("ls") │

│ └────────────────────┘

│

├─ fork() ─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ v

│ ┌────────────────────┐

│ 4. Create pipe2: [read_fd, write_fd] │ Child2 (pid 102) │

│ 5. fork() for sort │ - setpgid(0, 101) │

│ 6. In child: dup2(pipe1_read, STDIN) │ (same group!) │

│ dup2(pipe2_write, STDOUT) │ - exec("sort") │

│ close unused ends └────────────────────┘

│

├─ fork() ─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ v

│ ┌────────────────────┐

│ 7. fork() for head │ Child3 (pid 103) │

│ 8. In child: dup2(pipe2_read, STDIN) │ - setpgid(0, 101) │

│ close unused ends │ - exec("head") │

│ exec("head") └────────────────────┘

│

│ 9. Shell: close all pipe ends

│ 10. Shell: tcsetpgrp(tty_fd, 101) // Give terminal to job

│ 11. Shell: waitpid(-101, ...) for all children

│ 12. Shell: tcsetpgrp(tty_fd, 100) // Take back terminal

Questions:

- Why must all children be in the same process group?

- What happens if shell forgets to close pipe write end?

- Why does shell wait AFTER giving terminal to job?

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “Explain how a pipeline like

cat file | grep pattern | wc -lis set up.” - “What happens when you press Ctrl-C while a command is running?”

- “How do you prevent zombie processes in a shell?”

- “What’s the difference between a foreground and background job?”

- “How would you implement command substitution $(cmd)?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start Simple Begin with just executing single commands (fork, exec, wait). No pipes, no redirection. Get this working first.

Hint 2: Add Redirection Before exec(), use dup2() to redirect stdin/stdout to files. Remember to close the original file descriptor.

Hint 3: Pipelines

// For each pair of adjacent commands:

int pipefd[2];

pipe(pipefd);

// Left command gets pipefd[1] as stdout

// Right command gets pipefd[0] as stdin

Hint 4: Job Control Signals In the shell (parent):

- Ignore SIGINT, SIGTSTP, SIGTTIN, SIGTTOU

- Handle SIGCHLD to track job state changes

In child before exec:

- Reset all signals to SIG_DFL

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Process control | “APUE” by Stevens | Ch. 8 |

| Process relationships | “APUE” by Stevens | Ch. 9 |

| Signals | “APUE” by Stevens | Ch. 10 |

| Job control | “The Linux Programming Interface” | Ch. 34 |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem 1: “Pipeline hangs forever”

- Why: Forgot to close write end of pipe; reader never sees EOF

- Fix: Close ALL unused pipe ends in ALL processes

Problem 2: “Ctrl-C kills the shell”

- Why: Shell didn’t ignore SIGINT

- Fix: Shell must

signal(SIGINT, SIG_IGN)and reset in children

Problem 3: “Background job immediately stopped”

- Why: Background job tried to read from terminal (SIGTTIN)

- Fix: Redirect stdin from /dev/null for background jobs

Problem 4: “Zombie processes accumulating”

- Why: Not handling SIGCHLD properly

- Fix: Install SIGCHLD handler that calls waitpid(-1, …, WNOHANG)

Project 5: Process Monitor and /proc Explorer

- File:

myps.c - Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust, Go, Python (for prototyping)

- Coolness Level: Level 3 - Genuinely Clever

- Business Potential: Level 2 - Micro-SaaS (monitoring tools)

- Difficulty: Level 3 - Advanced

- Knowledge Area: Process Environment, /proc Filesystem

- Software or Tool: ps, top, htop

- Main Book: “Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment” by Stevens — Ch. 6, 7

What you’ll build: A process monitor that reads /proc filesystem to display running processes with their state, memory usage, CPU time, open files, and environment variables.

Why it teaches UNIX: The /proc filesystem exposes kernel data structures as files. Understanding it reveals how processes work internally and how monitoring tools like top and htop function.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Parsing /proc entries → Each file has different formats

- Calculating CPU usage → Requires sampling and delta calculation

- Handling race conditions → Processes can die while you read

- Terminal UI → Refreshing display without flicker

Real World Outcome

What you will see:

- Process listing: Like

ps auxwith more control - Real-time updates: Like

topbut showing your metrics - Per-process details: Memory maps, open files, environment

Command Line Outcome Example:

# 1. Basic process list

$ ./myps

PID PPID USER STATE %CPU %MEM VSZ RSS COMMAND

1 0 root S 0.0 0.1 167M 12M /sbin/init

42 1 root S 0.0 0.0 23M 5M /lib/systemd/systemd-journald

1234 1 user S 0.5 2.3 450M 94M /usr/bin/python3 app.py

5678 1234 user R 1.2 0.5 12M 4M ./myps

...

Total: 234 processes, 2 running, 232 sleeping

# 2. Detailed view of specific process

$ ./myps -p 1234

PID: 1234

Name: python3

State: S (Sleeping)

Parent PID: 1

Thread Count: 4

Priority: 20 (nice: 0)

Memory:

Virtual: 450 MB

Resident: 94 MB

Shared: 12 MB

Text: 8 MB

Data: 86 MB

CPU:

User Time: 45.32 seconds

System Time: 12.45 seconds

Start Time: Mar 15 10:00:00

Open Files (5):

0: /dev/pts/0 (terminal)

1: /dev/pts/0 (terminal)

2: /dev/pts/0 (terminal)

3: socket:[12345] (TCP 0.0.0.0:8080)

4: /var/log/app.log (regular file)

Environment (truncated):

PATH=/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin

HOME=/home/user

PYTHONPATH=/app/lib

# 3. Real-time mode (like top)

$ ./myps --top

myps - 10:23:45 up 5 days, 3:21, 2 users, load: 0.52 0.38 0.31

PID USER %CPU %MEM COMMAND

5678 user 25.3 4.2 ffmpeg

1234 user 5.1 2.3 python3

...

[Press 'q' to quit, 'k' to kill, 'r' to renice]

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How does the operating system expose process internals, and how can we inspect running processes without special privileges?”

The /proc filesystem is Linux’s window into the kernel. Understanding it teaches you what information the kernel tracks about each process and how to access it from userspace.

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- The /proc Filesystem

- What is /proc? Is it a real filesystem?

- What files exist in /proc/[pid]/?

- Book Reference: “The Linux Programming Interface” Ch. 12

- Process States

- R (Running), S (Sleeping), D (Uninterruptible), Z (Zombie), T (Stopped)

- What causes each state?

- Memory Metrics

- What’s the difference between VSZ and RSS?

- What is shared memory?

- Book Reference: “APUE” Ch. 7.6

- CPU Time Accounting

- User time vs system time

- How to calculate CPU percentage?

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Data Collection

- Which /proc files give you which information?

- How to handle parsing errors gracefully?

- CPU Percentage

- This requires two samples—how to structure that?

- What time interval to use?

- Error Handling

- Process disappears between opendir and reading—what to do?

- Permission denied on some /proc entries?

Thinking Exercise

Parse /proc/[pid]/stat

This single line contains most process info:

$ cat /proc/1234/stat

1234 (python3) S 1 1234 1234 0 -1 4194304 12345 0 0 0 452 124 0 0 20 0 4 0

^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^

| | | | | | | | | | |

PID comm | | | SID TTY flags minflt utime stime

state

PPID

PGID

Fields (selected):

- 1: PID

- 2: comm (executable name in parens)

- 3: state (R, S, D, Z, T, etc.)

- 4: ppid

- 14: utime (user mode jiffies)

- 15: stime (kernel mode jiffies)

- 20: num_threads

- 23: vsize (virtual memory size in bytes)

- 24: rss (resident set size in pages)

Exercise: Write code to parse this line. Watch out for comm containing spaces or parentheses!

The Interview Questions They’ll Ask

- “How would you find which process is using the most CPU?”

- “What’s the difference between /proc/meminfo and /proc/[pid]/status?”

- “How does top calculate CPU percentage?”

- “What information can you get about a process without being root?”

- “How would you detect if a process is leaking file descriptors?”

Hints in Layers

Hint 1: Start with /proc/[pid]/stat This file has most of what you need. Parse it carefully—the comm field can contain spaces.

Hint 2: Directory Scanning

// List all processes

DIR *dir = opendir("/proc");

while ((entry = readdir(dir)) != NULL) {

if (isdigit(entry->d_name[0])) {

// This is a process directory

}

}

Hint 3: CPU Percentage Calculation

// Sample 1: record utime1 + stime1, total_time1

// Sleep for interval (e.g., 100ms)

// Sample 2: record utime2 + stime2, total_time2

cpu_percent = 100.0 * (utime2 + stime2 - utime1 - stime1) /

(total_time2 - total_time1)

Hint 4: Open Files from /proc/[pid]/fd

This is a directory of symlinks. readlink() each entry to get the file path.

Books That Will Help

| Topic | Book | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| /proc filesystem | “The Linux Programming Interface” | Ch. 12 |

| Process environment | “APUE” by Stevens | Ch. 7 |

| Memory management | “Understanding the Linux Kernel” | Ch. 8-9 |

Common Pitfalls & Debugging

Problem 1: “Segfault when parsing comm field”

- Why: Process name contains ‘)’ or spaces

- Fix: Find the LAST ‘)’ in the line, not the first

Problem 2: “CPU percentage over 100%”

- Why: Multi-threaded processes can use more than 100% (one core)

- Fix: This is correct for SMP. Divide by num_cores for normalized percentage.

Problem 3: “Permission denied on /proc/[pid]/fd”

- Why: Can only read fd directory for your own processes (unless root)

- Fix: Skip or show “permission denied” gracefully

Problem 4: “Process vanishes mid-read”

- Why: Process exited between directory scan and file read

- Fix: Handle ENOENT gracefully—the process simply ended

Project 6: Robust Signal Handler Framework

- File:

sighandler.c - Main Programming Language: C

- Alternative Programming Languages: Rust (with unsafe), Go (limited signal support)

- Coolness Level: Level 4 - Hardcore Tech Flex

- Business Potential: Level 1 - Resume Gold

- Difficulty: Level 4 - Expert

- Knowledge Area: Signals, Asynchronous Events

- Software or Tool: Daemon services, graceful shutdown handlers

- Main Book: “Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment” by Stevens — Ch. 10

What you’ll build: A signal handling framework that properly handles SIGINT, SIGTERM, SIGCHLD, SIGALRM, and SIGUSR1/SIGUSR2, demonstrating safe practices for signal-aware programming.

Why it teaches UNIX: Signals are UNIX’s asynchronous notification system. Mishandling them causes race conditions, crashes, and security vulnerabilities. This project forces you to understand reliability, reentrancy, and the subtleties of signal delivery.

Core challenges you’ll face:

- Async-signal-safety → Only certain functions are safe in handlers

- Race conditions → Signal can arrive at any point in your code

- Reliable signal handling → sigaction() vs signal(), signal masks

- Self-pipe trick → Converting signals to I/O events

Real World Outcome

What you will see:

- Graceful shutdown: SIGTERM triggers cleanup and exit

- Child reaping: SIGCHLD handled without zombies

- Periodic timers: SIGALRM for scheduled tasks

- Signal logging: Track and display all signals received

Command Line Outcome Example:

# 1. Start the signal demo program

$ ./sigdemo

Signal handler framework running (PID 12345)

Press Ctrl-C to test SIGINT handling

Send signals: kill -TERM 12345, kill -USR1 12345, etc.

# 2. Send signals from another terminal

$ kill -USR1 12345

$ kill -USR2 12345

$ kill -TERM 12345

# 3. Output from sigdemo:

[10:30:01.123] Received SIGUSR1 (10) - User defined signal 1

[10:30:02.456] Received SIGUSR2 (12) - User defined signal 2

[10:30:03.789] Received SIGTERM (15) - Termination signal

[10:30:03.790] Beginning graceful shutdown...

[10:30:03.791] Flushing buffers...

[10:30:03.792] Closing connections...

[10:30:03.793] Shutdown complete. Exiting.

# 4. Child process handling

$ ./sigdemo --fork-children 5

Forked 5 child processes

[10:30:10.000] Child 12346 exited with status 0

[10:30:10.100] Child 12347 exited with status 0

[10:30:10.200] Child 12348 exited with status 0

[10:30:10.300] Child 12349 exited with status 0

[10:30:10.400] Child 12350 exited with status 0

All children reaped. No zombies!

# 5. Timer demonstration

$ ./sigdemo --timer 2

Setting SIGALRM every 2 seconds

[10:30:00] Timer fired! Count: 1

[10:30:02] Timer fired! Count: 2

[10:30:04] Timer fired! Count: 3

^C

Caught SIGINT. Stopping timers and exiting...

The Core Question You’re Answering

“How do you handle asynchronous events safely in a program where a signal can interrupt literally any line of code?”

This question is fundamental to any long-running server or daemon. The answer involves understanding async-signal-safety, the self-pipe trick, and proper use of sigaction().

Concepts You Must Understand First

Stop and research these before coding:

- Signal Delivery Mechanics

- When exactly does a signal get delivered?

- What happens to blocked signals?

- Book Reference: “APUE” Ch. 10.2-10.4

- Async-Signal-Safety

- Which functions are safe to call in a handler?

- Why is printf() not safe?

- Book Reference: “APUE” Ch. 10.6

- sigaction() vs signal()

- Why is signal() unreliable?

- What does SA_RESTART mean?

- Book Reference: “APUE” Ch. 10.14

- Signal Sets and Masks

- sigset_t, sigfillset(), sigaddset()

- sigprocmask() and blocking signals

- Book Reference: “APUE” Ch. 10.11-10.12

Questions to Guide Your Design

Before implementing, think through these:

- Handler Design